The Other China is not the China of stentorian slogans, cutting barbs, sarcastic put-downs. It is not the China of clichéd patriotism and exaggerated public performance; nor is it the China of crude stereotypes and bottomless grievance. It is a China of humanity and decency, of quiet dignity and unflappable perseverance. It is a China that finds expression in myriad ways in a country dominated by a political party that would bend all to its will; it is a China that survived the depredations of the Mao era (1949-1978) and increasingly flourished during the decades of reform from 1978 to 2008. For decades, Hong Kong was a global nexus for The Other China (for more on this, see Hong Kong Apostasy in this journal).

The Other China, or what could also be called ‘Other Chinas’, is not limited to the People’s Republic of China, for it is part of a global culture unique to itself but also with universal aspirations and appeal.

Throughout the Xi Jinping era Official China has strained to impose uniformity on the Chinese world, be it in the People’s Republic or internationally. Despite its tireless attempts to discipline, corral and silence the voices of difference, The Other China/ Other Chinas, or what elsewhere we have referred to as the Invisible Republic of the Spirit, an ‘inland empire’ if you will, persists. Cowed at times, The Other China is resilient. Long after the droning monotone of Xi Jinping and his minions has died down, The Other China will flourish in variegated and ever-newer ways. The Xi Jinping autarchy has, if anything, contributed to the international presence of The Other China, just as other periods of repression in China Proper led to a flourishing of Chinese possibility elsewhere.

China Heritage is devoted to listening to and understanding aspects of The Other China. Many of our essays, translations and commentaries offer access to, as well as insights into China’s parallel worlds and in this section of China Heritage we focus on works and creators who advance our understanding of the rich and evolving Chinese multiverse.

Our interest in The Other China is a continuation of the work of China Heritage Quarterly, the predecessor of China Heritage, where we first introduced readers to T’ien Hsia Monthly and The China Critic, both of which were early outlets for voices from The Other China.

***

***

It is over forty-five years ago since, after three years at Maoist universities in the mid 1970s, I had my initial encounter with ‘The Other China’. It was in the home of the renowned translators Yang Xianyi and Gladys Yang and, through the warm embrace of their friendship, I was granted entry to a realm that existed both in parallel to, and often in spite of, Official China:

‘From the dying days of the Cultural Revolution, Xianyi and Gladys’ sitting room became the scene of a unique and unforgettable salon, for Chinese and non-Chinese friends and visitors alike. It was also something of an alien realm, a post-colonial ‘extra-territorial zone’, for although the Yangs were still under constant surveillance, even their past minders, keepers and in some cases oppressors would out of curiosity and wonderment come calling, sometimes sincerely to pay their respects. As time went on and as the shrill nonsense of Maoist revolution faded both from reality and from memory many who had shunned the Yangs in the past, or those who had been given the cheerless task of making their lives a misery, began to sense that what had been of such moment was merely transitory folly, while the world of letters and conversation, understanding and engagement represented by Gladys and Xianyi would outlast them all.’

— The People’s Republic of Wine, China Heritage Quarterly, March 2011

In China Heritage ‘The Other China’ both celebrates and strives to introduce readers to that invisible republic of the spirit.

The lively tension between Substance, Shadow and Spirit 身、影、神, as revealed in the poetry of Tao Yuanming, best reflects my notion of The Other China. While aspects of the The Other China can be conveyed in words 言傳 yán chuán, others call for an intuitive appreciation 意會 yì huì.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

January 2023

***

Related Material:

- New Sinology in 1964 and 2022

- Readings in New Sinology

- Hong Kong Apostasy

- Xu Zhangrun Archive

- Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium

- A voice from Old Shanghai under COVID lockdown, 6 April 2022

- Wang Jixian: A Voice from The Other China, but in Odessa, 12 March 2022

- I’ve Forgotten How to Kneel in Front of You, 21 March 2022

- Chen Qiushi’s Gift of the Gab, 28 December 2020

- Silent China & Its Enemies — Watching China Watching (XXX), China Heritage, 13 July 2018

- Contentious Friendship, 29 April 2018

- Xi Xi’s Floating City, 12 July 2017

- Rock Stands and Mud Washes Away, 18 November 2015

- 1949-2009: Sixty Years Out of Range, September 2009

- Worrying China and New Sinology, July 2008

- The Chinese Attitude Towards the Past, June 2008

***

Inside the Wall of Stagnation

The party can control and weaponize information, but dissenters are also surprisingly well entrenched. Aided by digital technology, they are also far more nimble than their Soviet-era counterparts. Among China’s educated elite, many persist in opposing the regime’s version of reality. Even though they are banned, virtual private networks, which allow users to bypass Internet controls, are now widespread. Underground filmmakers are still working on new documentaries, and samizdat magazine publishers are still producing works distributed by basic digital tools such as PDFs, email, and thumb drives. These efforts are a far cry from the street protests and other forms of public opposition that attract media attention, but they are crucial in establishing and maintaining the person-to-person networks that pose a long-term challenge to the regime.

In May, I visited the editor of an underground magazine in a relatively remote part of south Beijing. He publishes a fortnightly journal featuring contributions by academics across China, who often use pen names to protect their identities. Their articles challenge the party’s account of key crises in its history, filling in events that have been whitewashed. Some of the editing work is now done by Chinese graduate students working abroad. This model of underground digital publishing was adopted last year by protesters, who used VPNs to upload videos to Twitter, YouTube, and other banned sites. Such online platforms function as storehouses, allowing Chinese people to download information that the state is trying to suppress.

In this case, the editor commissions the articles, edits them, and sends them abroad for safekeeping in case the authorities raid his office. The journal’s layout is also created abroad, and volunteers inside and outside China email each issue to thousands of public intellectuals across China. The magazine is part of a growing community that has been systematically documenting the party’s misrule, from past famines to the COVID pandemic. Although his journal and similar efforts may ordinarily reach only tens of thousands of people in China, the articles can have a much larger impact when the government errs. During the COVID crisis, for example, the magazine’s editor and his colleagues noticed a spike in readership, and others found that their essays were even going viral. In good times, this pursuit of the truth might have seemed quixotic; now, for many of the Chinese, it is beginning to seem vital. As they spread, these anonymous informal networks have opened a new front in the party’s battle against opposition, the control of which now requires far more than simply throwing dissidents in jail.

I sat with the editor in his garden for a couple of hours, under trellises of grapes he uses to make wine. The skies were deep blue, and the sun was strong. The cicadas of a Beijing summer day drowned out the background noise. For a while, it felt as if we could be anywhere, maybe even in France, a place that the editor has enjoyed visiting. He has published the journal for more than a decade and has now handed off most of the work to younger colleagues in China and abroad. He was relaxed and confident.

“You can’t do anything publicly in China,” he said. “But we still work and wait. We have time. They do not.”

— Ian Johnson, Xi’s Age of Stagnation — The Great Walling-Off of China,

Foreign Affairs, September/October 2023

***

Contents

- Stories of Regret — The Zhang Family of Huayin, 30 April 2017

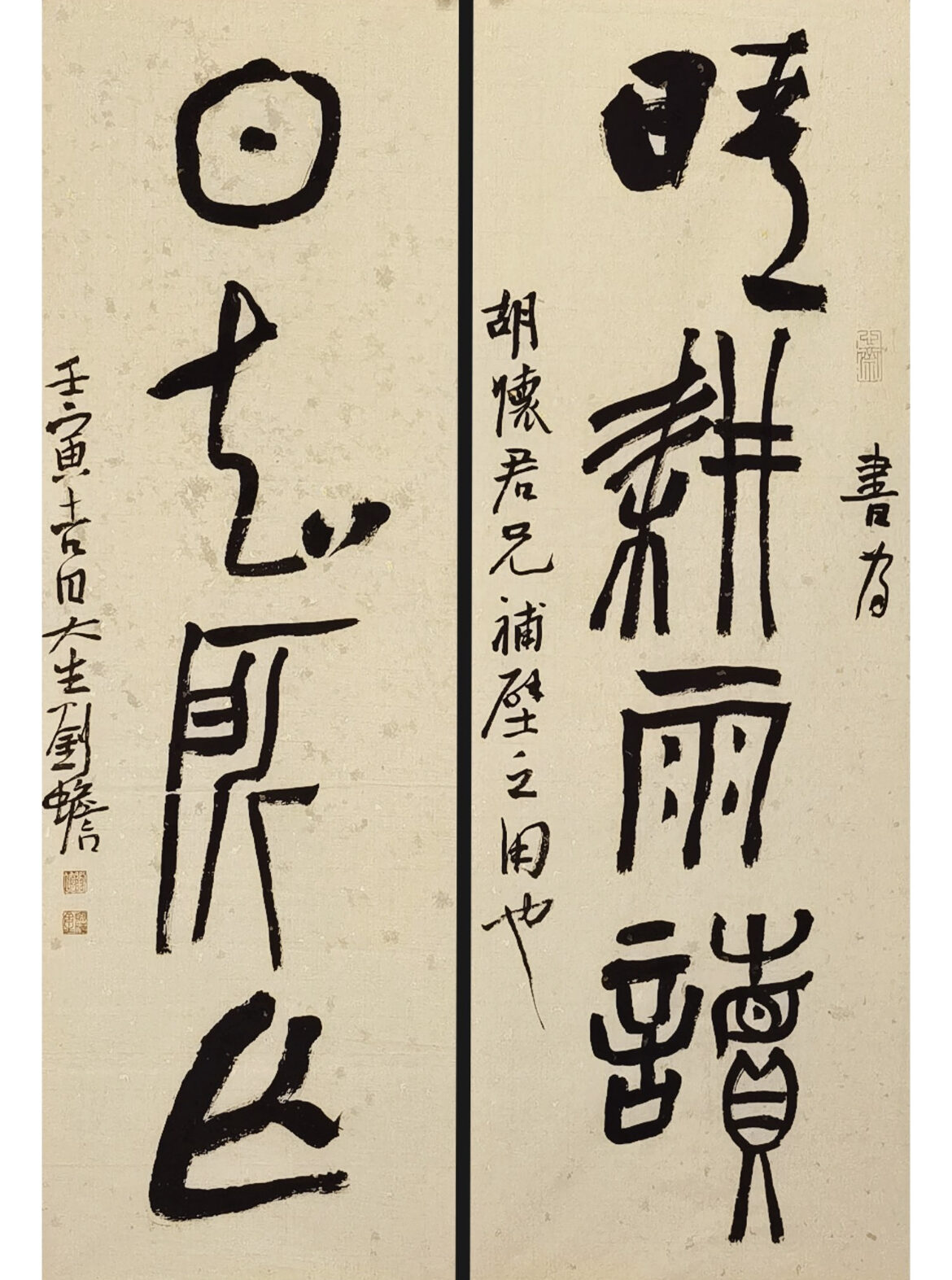

- Liu Chan’s Memorial for the Departed, 12 January 2023

- On Rumours & Lies — Dasheng’s Little Lectures, 16 January 2023

- Brainwashing vs. Educating — Dasheng’s Little Lectures, 17 January 2023

- Resisting Cultural Capture — Dasheng’s Little Lectures, 18 January 2023

- In the Eyes of the Beholder — Dasheng’s Little Lectures, 19 January 2023

- The Tail-end of Tiger Tyranny, 20 January 2023

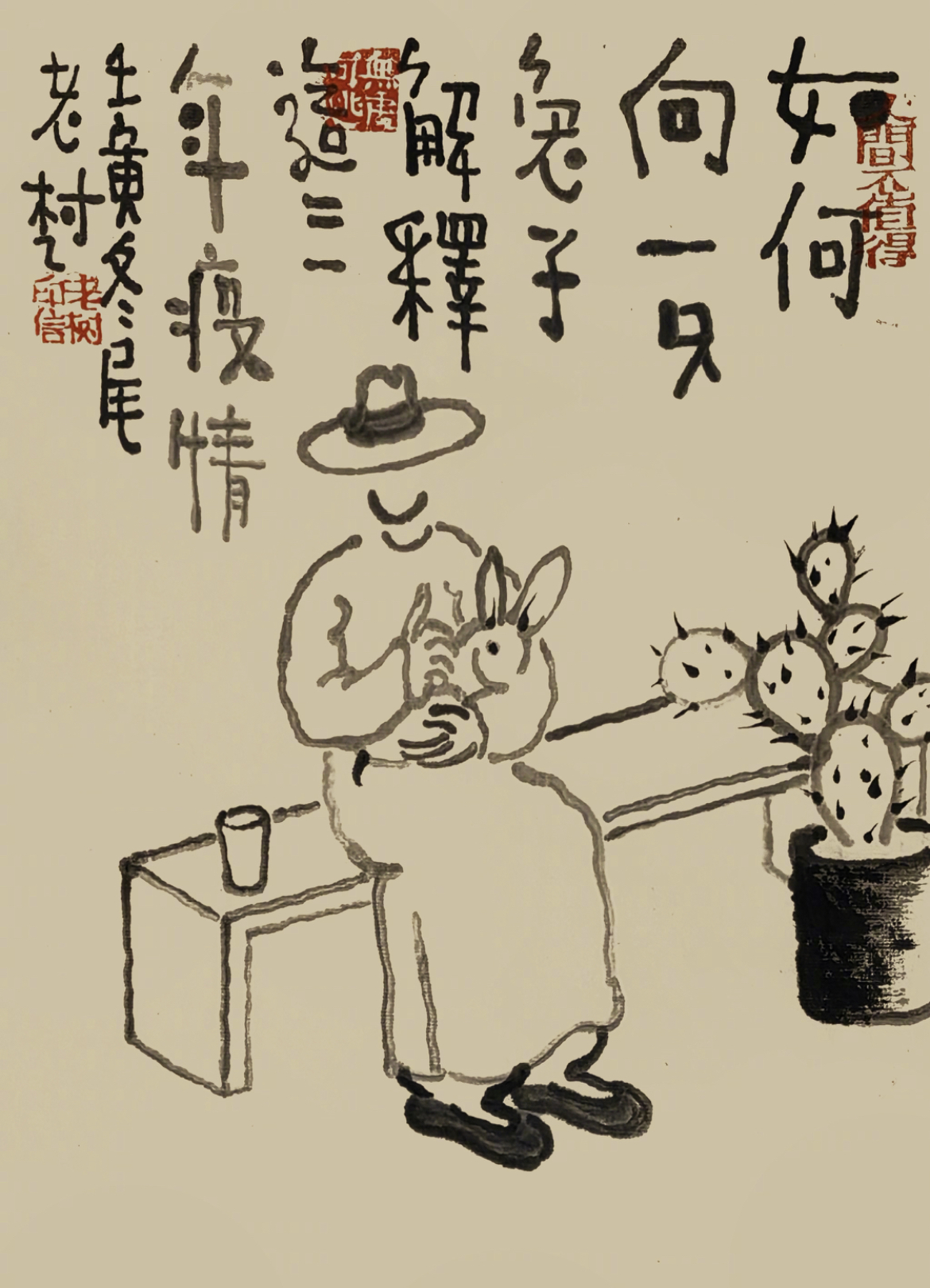

- Now What? — Greeting the Guimao Year of the Rabbit 癸卯兔年, 21 January 2023

- A Protection Mantra for the Year of the Rabbit, 22 January 2023

- Rabbiting on with Lao Shu, 23 January 2023

- A Cultural Apéritif at M on the Bund, 28 January 2023

- Praise for the Orange Tree, Remembering the Plum, 8 February 2023

- High Peaks, Translucent Torrents, 24 February 2023

- Craven, Servile Knaves Hold Office, 7 March 2023

- Li Yuan in conversation with He Huang, Badiucao and Teacher Grey (in Chinese), A Long Arm — China attempts to be a global censor, Bumingbai Podcast, 12 March 2023

- Hands off Snakey — Teacher Grey’s Chinese Lessons, 16 March 2023

- ‘I am not nostalgic, I want to remember.’ — Lao Shu, spring 2023, 20 March 2023

- Return to Vulture Peak — Qingming 2023, 5 April 2023

- Dong Zhimin, Xu Zhiyong & Ding Jiaxi — Chen Qiushi on Legalised Rape and Outlawed Dissent in China Today, 20 April 2023

- The Passion of Jimmy Lai, 21 April 2023

- Don’t Let the Dogs Eat World Book Day, 23 April 2023

- Dragging One’s Tail in the Mud on 1 May 2023, 1 May 2023

- When Bamboo Invites a Zephyr, 12 May 2023

- In the Company of Cats, 4 June 2023

- Tired of Winning Yet, China? — The Band Slap Has Some News for You, 14 June 2023

- Yongyu, ave atque vale, 15 June 2023

- Huang Yongyu, Lee Yee & Jimmy Lai, 22 June 2023

- ‘Jesus, you’re such fucking dopes … You are not serious people’ — Flaubert’s Tide of Shit swells in Wellington, New Zealand, 24 June 2023

- ‘Read, read, read. Listen, listen, listen.’ — It’s Never Too Late to Learn Modern and Literary Chinese, 19 July 2023

- The Topsy-turvy Country — China’s Summer Hit, 28 July 2023

- I’d rather support stray cats in Japan than donate a single penny to China’s disaster relief efforts, 8 August 2023

- Voices from The Other China — Ten Podcasts & Twenty YouTube Channels, 10 August 2023

- From the White Paper Protest to a White Wall in London, 20 August 2023

- With Jack Kerouac in Chiang Mai — Planet Speakeasy & The Other China, 在路上 — Chapter Thirty-one in Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium, 7 September 2023

- Liu Chan’s Calligraphic Comment on 7 October 2023, 8 October 2023

- Humanism, a Modest Existential Threat to Xi Jinping’s Ideological Security State — 人妖之間, 20 October 2023

- Old Landscapes in New Beijing — photographs by Lois Conner, 23 October 2023

- Monster Mash — Mourning a Dead Premier & Mocking the Ghouls Among the Living, 4 November 2023

- What Scares Me — a letter from Kathy on the first anniversary of the Blank Page Movement, 4 December 2023

- Lao Shu’s Fall, 12 December 2023

- Lao Shu’s New Year, 4 January 2024

- ‘I’d like to ride the wind to fly home’, by Wu Fei, 5 January 2024

- On the Road — Taipei vs. Beijing, 12 January 2024

- An Ambitious Dragon’s Nightmare, 26 January 2024

- Lao Shu’s Farewell to the Year of the Rabbit, 31 January 2024

- So Starts the Spring, 4 February 2024

- Embarking upon the Jiachen Year of the Dragon 甲辰龍年, 9 February 2024

- Li Yuan 袁莉, Émigrés Are Creating an Alternative China, One Bookstore at a Time, The New York Times, 23 February 2024

- 24 February 2024 — 元宵, the End of the Beginning, 24 February 2024

- ‘Do you really think you can eat those pies in the sky?’ — Lao Shu embarks upon the Year of the Dragon, 29 February 2024

- Liu Chan 劉蟾, Caged Birds and Turd Blossoms, 1 March 2024

- Xu Zhangrun, Mourning Alexei Navalny, Shedding Tears for China, 2 March 2024

- Something in the Air — Lao Shu’s Spring, 1 April 2024

- Catherine Churchman, Why Is Chinese So Boring?, 26 May 2024

- Lao Shu — an artist in all seasons, 30 June 2024

- The Whimsy and Wisdom of Lao Shu, in a summer of discontent, 12 August 2022

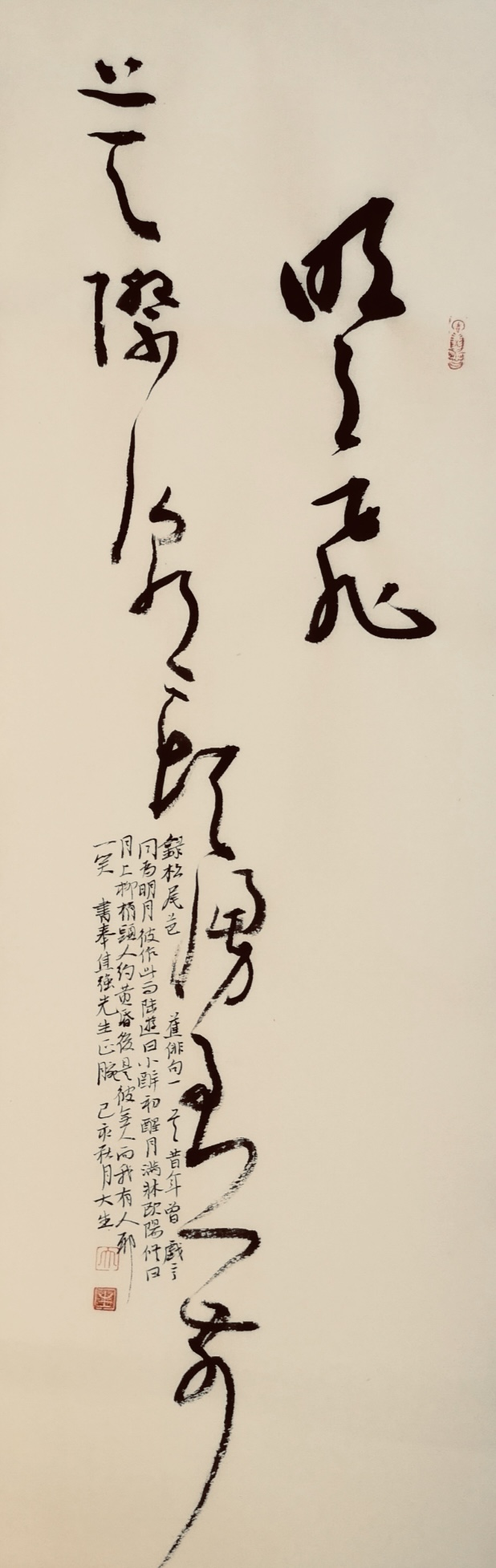

- Lao Shu — roaming through Tang-Song landscapes with my Wei-Jin brothers, 13 July 2024

- Chang Che, Reimagining China in Tokyo, The New Yorker, 30 July 2024

- On a bed of blossoms, dreams take me to the Tang, 26 August 2024

- An Express Delivery from the Tang Dynasty, 18 September 2024

- ‘Facing the Republic’ — on the 10th of October 2024

- Only ever one step away — Lao Shu’s travels in time and space, 16 October 2024

- As the Year Flitters Away — Lao Shu’s Autumnal Hues, 10 December 2024

- Keeping Ahead of the Game — Lao Shu Farewells 2024, 31 December 2024

- Sisyphus in 2025 – Lao Shu’s New Year, 1 January 2025

- From Lao Shu’s Studio of Drunken Dreams, 28 January 2025

- Lofty Aspirations & Modest Wishes for the Year of the Snake, 29 January 2025

- The Lantern Festival in the Year of the Snake, 12 February 2025

- Loitering in this Dusty Realm — paintings and poems by Lao Shu, 24 February 2025

- Liu Chan’s Studiolo of the Heart, 5 March 2025

- ‘I envy clouds their freedom.’ — Lao Shu, 21 April 2025

- This Fleeting Year, 30 April 2025

- Lao Shu’s Scattered Petals, 10 May 2025

- ‘So it Begins, with the Written Word’ — Xu Zhangrun Accepts a Human Rights Award, 12 May 2025

- Searching for Solitary Fellowship — paintings and poems by Lao Shu, 5 June 2025

- The Strange Tales of Aladdin Dogballs, 18 August 2025

- Underground Elegies — on a China that won’t be silent, 30 August 2025

- Dignity, Decency and the Lies of the Present, 6 September 2025

- Li Yuan 袁莉 in conversation with Andrea Cavazzuti (老安), an Italian artist and businessman resident in China since 1981 (in Chinese): 老安:一個意大利人對中國氣呼呼的愛,不明白播客,2025年9月8日

- Visiting Tao Yuanming in the Autumn, 10 October 2025

-

To be continued … …

Also published in China Heritage

- Chinese Time, Part I: 新鬼舊夢— More New Ghosts, Same Old Dreams, 1 January 2023; Part II: 忘卻的紀念 — the struggle of memory against forgetfulness, 2 January 2023

- ‘Ironic Points of Light’ — acts of redemption on the blank pages of history, 4 December 2022

- Xu Zhangrun at Sixty, China Heritage, 25 October 2022, Appendix XX 花甲 in Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium

- Notre seul parapluie — ‘Life is a shitstorm, in which art is our only umbrella.’, China Heritage, 15 August 2022