A Lesson in New Sinology

顛倒:羅剎海市

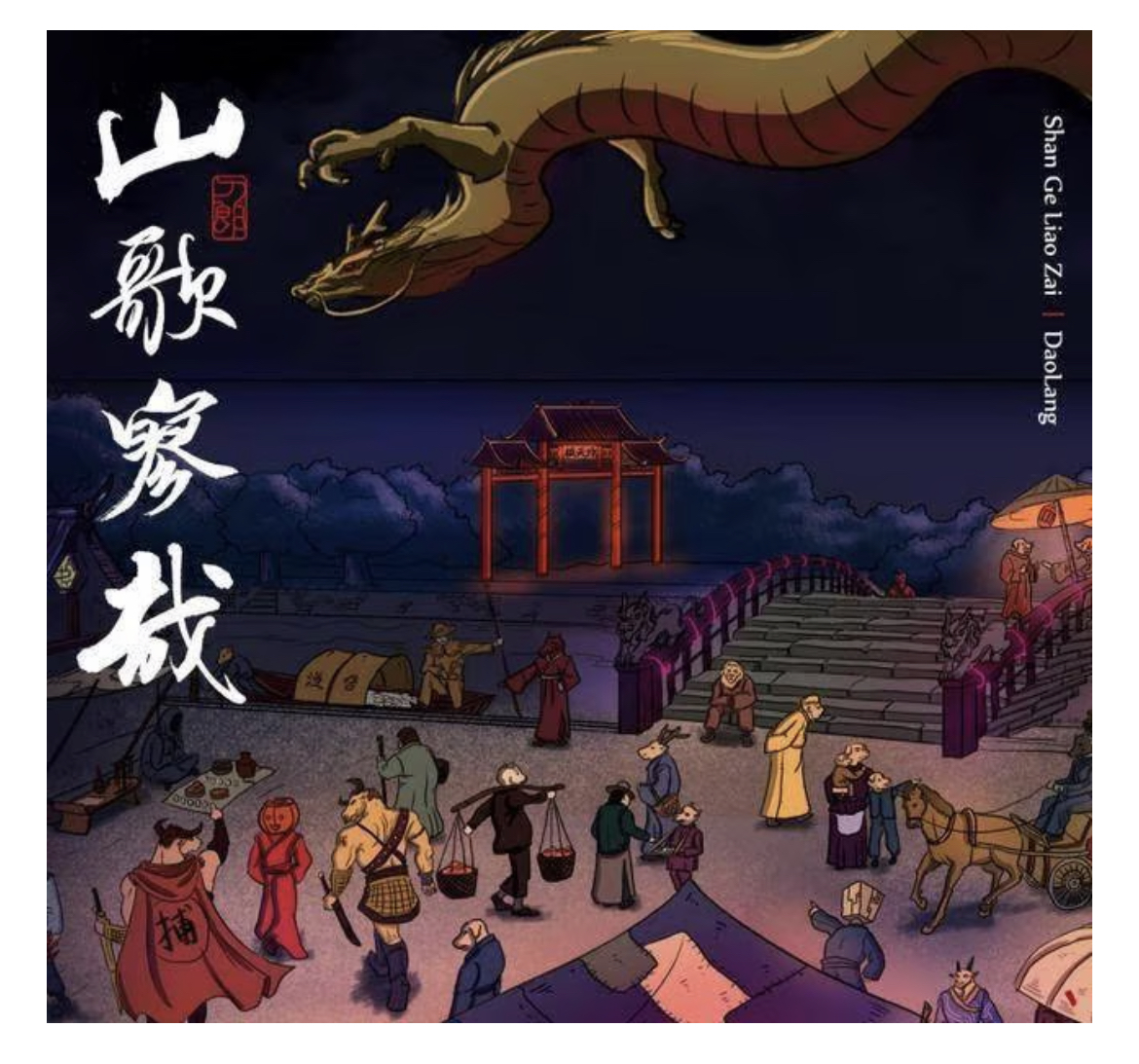

Within days of its release on 19 July 2023, the song ‘Land of the Rakshasas & the Sea Market’ 羅剎海市, featured in There Are Few Folk Songs 山歌寥哉, a new album by the popular singer Dao Lang 刀郎 (羅林, 1971-), had become the equivalent of a Chinese summer hit. Soon its ubiquity would transform it into an earworm.

[Note: Rakshasa — rākṣasa राक्षस, 羅剎 luóchà — are a mythical race, fiendish in appearance and possessed of supernatural powers. The Chinese word 羅剎 luóchà is a transliteration of the original Sanskrit. The title of Dao Lang’s song is also translated as ‘Demons and Mirages’.]

Singing in the style of Er’ren zhuan 二人轉, a traditional song-and-dance style popular in northeast China, Dao Lang took his theme from a well-known story in Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio 聊齋誌異 by the Qing-dynasty author Pu Songling. Pu’s ‘Land of the Rakshasas & the Sea Market’ 羅剎海市 is set in a topsy-turvy place, where ugliness is regarded as beautiful — 以醜為美 — and villainy is the coin of the realm. As Dao Lang sings:

Coal is always pitch black

Nothing can rid it of filth可是那從來煤蛋兒生來就黑

不管你咋樣洗呀那也是個髒東西

Dao Lang’s fans did not all think that he was singing about fictitious people nor, for that matter, a make-believe land.

After the song’s narrative has lambasted the duplicity of the Land of the Rakshasas, the protagonist of the action, a comely young man by the name of Ma Ji, seeks his bliss in the ‘Sea Market’ 海市 — a reference both to the idyllic kingdom depicted in Pu Songling’s story as well as to the illusory world of appearances, or 海市蜃樓 hǎi shì shèn lóu.

Analysts, influencers and online talking heads interpreted the song according to their own predilections; many used the expression 見仁見智 jiàn rén jiàn zhì (‘everyone has their own take on things’) to sum up the proliferation of clashing opinions. (See, for example, this explication of the Dao Lang’s use of Ludwig Wittgenstein’s philosophy of language.) Some Chinese media outlets claimed that, as of 27 July 2023, Dao Lang’s song had been played or downloaded on various online platforms over one billion (ten hundred million) 十億 shí yì times. The song also took TikTok by storm inspiring numerous imitators as well as a raft of adaptations, from Peking Opera and Kunqu to even more theatrical local musical styles.

[Note: By 30 July, the number of downloads exceeded five billion 五億. See also 盤點翻唱《羅剎海市》最好聽的六個版本. By early August, the number had reportedly swelled to eight billion, a figure that put the song in competition with Despacito, the 2017 viral Reggaeton hit. TikTok had also been flooded with a cacophonous array of covered versions of Dao Lang’s song.]

After the Covid years, in the face of erratic Party policies and the economic downturn, this ‘eruption of interpretation and imitation’ had the hallmarks of a moment of mass catharsis.

Dao Lang, who had been absent from the music scene for some time, in part due to professional jealousy, had returned with a vengeance by employing his art to take aim at various (unnamed) enemies while at the same time offering a kind of social commentary that resonated with tens of millions of listeners. One thing, was clear: in his latest album Dao Lang had given further proof to the old adage 君子報仇 ,十年不晚, ‘revenge is a dish that can also be served cold’. The singer kept his own counsel while people throughout China named and shamed singers and critics who had previously dismissed him as vulgar and crude. Mocked as a ‘Gang of Four’ henceforth these fading stars would for most part solely be remembered for Dao Lang’s comic barbs.

[Note: Vengeance, exacting revenge and the hope for a ‘karmic comeuppance’ for one’s enemies are perennial themes in Chinese culture. Presumably this contributed to the immense popularity of Dao Lang’s infectiously catchy tune. See also Andrew Methven’s Phrase of the Week for The China Project — ‘ten years sharpening a sword’ 十年磨一劍 shí nián mó yí jiàn.]

***

Below, we provide a link to Dao Lang’s song on YouTube followed by a spirited comment by Mei Liu’r 梅六兒, a Beijing story-teller, regarding what he things is one of the coded political messages in the song. This is followed by a compilation of homages to the singer. In conclusion, we offer a translation of Pu Songling’s original story by Yang Xianyi and Gladys Yang.

Apart from the artistic and cultural significance of Dao Lang’s There Are Few Folk Songs 山歌寥哉, the album should also appeal to students of New Sinology, as well as to anyone who is familiar with the music of the band Slap 耳光 (see Tired of Winning Yet, China? — The Band Slap Has Some News for You, China Heritage, 14 June 2023).

My thanks to Mr Yanwu for bringing Dao Lang to my attention and to Callum Smith for electronically transcribing Mei Liu’r’s commentary.

A Topsy-turvy Country — China’s Summer Hit is included as a chapter in both Lessons in New Sinology and The Other China, as well as an Appendix XLVI in the series Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

28 July 2023

***

Men must put on false, ugly faces to please their superiors — such is the hypocritical way of the world. The foul and hideous are prized the world over. Something of which you feel a little ashamed may win praise; while something of which you feel exceedingly ashamed may win much higher praise. But any man who dares to reveal his true self in public is almost certain to shock the multitude and make them shun him. Where, indeed, can that fool of Lingyang take his priceless jade to weep? Alas! I shall seek my fortune in castles in the clouds and mirages of the sea.

異史氏曰:花面逢迎,世情如鬼。嗜痂之癖,舉世一轍。小慚小好,大慚大好,若公然帶鬚眉以游都市,其不駭而走者,蓋幾希矣。彼陵陽痴子,將抱連城玉向何處哭也。嗚呼。顯榮富貴,當於蜃樓海市中求之耳。

— Pu Songling’s epilogue from ‘Land of the Rakshasas & the Sea Market’

***

Land of the Rakshasas & the Sea Market (aka Demons and Mirages)

Dao Lang

[Note: For a translation of the lyrics, see here. See also Dylan Levi King’s observations on Dao Lang.]

***

What’s Dao Lang Really Satirising?

Mei Liu’r

As Mei Liu’r observes that:

他這歌詞兒啊寫得很妙,不管你是往深瞭解讀還是往淺瞭解讀不管你是往這個大的解讀還是小瞭解讀啊,你都可以解讀的出來。這歌兒短短幾句話,把這個小到每一個有如此作風的人啊全都諷刺了一遍,大到呢諷刺了整個社會。

也就是說整個社會的名利場哎,把職場、娛樂圈和官場這些名利場里一些骯臟的人和事兒那是全損了一遍。當然,現在的社會風氣也比較貼合這首歌兒。你要說人人都知真至善呀,咱也別要求那麼高,就是人人要都沒有這種與天鬥、與地鬥、與人鬥的這種鬥爭精神的話,這歌兒也不可能這麼火。這歌兒的全部歌詞、我就不解讀了,因為解讀的人實在是太多了,您要有興趣可以自己看。

好的,就解讀兩句話,這歌兒里啊最凶的、最狠的、攻擊性最強的兩句話。這幾句歌詞呢也是我個人最喜歡的幾句,我給大家念念啊:

它紅苗翅那個黑黃皮綠袖,雞冠金鑲蹄,可是從來沒蛋,生來就黑。不管咋樣,洗還是個臟東西。

這幾句,那是往根上罵呀都不是往根上罵呀,這幾句是往種子上罵啊,就跟我以前節目說過那個我養花的故事差不多。這這句話解讀的人很多,不過,大部分的解讀我個人感覺都沒解讀到位。大眾流行的解讀是什麼呢?

說這人,你要是心黑了啊,你別洗啦,你怎麼樣你也洗不白了,這個不完全對。大家仔細看他這歌詞啊,他說可是那黑煤蛋兒生來就黑,不管你怎麼洗你都是臟東西啊,這個生來就黑。所以,它不是罵人的呀,人之初性本善嘛。

沒有人說一生下來這個意識里產生出的第一個刨去本能的思想就是說我以後我要坑人、害人,我要殺人、放火,我我得為了這個方向進行努力。沒有人的心生出來就是黑的,這你得家庭環境、學校環境、社會環境和自己的自學而行的。

即使說這人半途心黑了,那也得容人家有一個自我改正的機會吧,萬一他意識到自己的錯誤了是吧,改了那就是好同志啊,也不至於一棍子打死。所以我個人覺得,他這個歌詞罵的是一切跟人類有關的、邪惡的、不良的意識形態。

怎麼說呢?比如,有這麼一種意識形態,它從根本上就是錯誤的;這個意識形態從一開始就描繪了一個非常之美好的光景呀,大同。大家都是平等的,互幫互助,人人有愛有福同享,有難同當。這個不是不可能發生,不過,這個得是幾千年以後的事兒了。

因為現在的這人類基本素質沒有達到這個要求,您呢得慢慢來一步一步的共建這個文明社會。不過呢,這個意識形態告訴你,只要照我說的做,幹完了以後立刻就能實現這副好光景。要達到這種境界,首先是需要什麼呢?暴力!這個意識形態的創始人也沒明確地表示,只要你相信我這個東西,你就必須得相信暴力。

我們這個意識形態形成的組織不玩虛的,成立的目的就是以殺人放火為這個暴力基礎,去推翻現有的社會制度。這個意識形態就等同於暴力吧,宗旨就是以暴制暴啊以暴制敵,以暴制有,以暴制明、以暴制制、以暴制惡,甚至於以暴制善。

總而言之呢,就是以暴力的手段達到我擴張的目的。從此這個意識形態火了。最先被煽呼起來的都是什麼人呢:窮人、農人哎、受到過現有制度不公的人、受壓迫的人,或者呢是認為自己受壓迫的人,村痞流氓、混混、文化流氓、文盲流氓就全來了。

這個時候我就有了一群戰友,我以這個意識形態啊為方針啊開始忽悠宣傳,廣而告之,宣揚暴力、宣揚革命。可是呢我光憑嘴這麼說,這麼宣傳那誰信我呀是吧,咱得忽悠。哎。怎麼忽悠呢?把這個意識形態里描述的美好的東西啊加上我自己的一些演繹啊,忽悠給大家傳播出去哎,跟我們乾大秤分金、小秤分、銀分、田分地。

等咱們暴力革命成功以後啊,我也不主事是吧,把權力散發出去,大家說了算,誰說了都算民主啊。因為咱們這意識形態講究的就是公平,講究的就是自由啊,說真話、辦真事。等富貴均貧富,總之,成功以後,除了這個媳婦兒、老公不能分,其他的一概都能分,大家都平分,大家都有錢,大家都說了算。

多麼美好的一幅畫卷。最終我的這個天生暴力的意識形態灌輸進了每一個人的腦袋里。我成功了。我成功以後就開始更加瘋狂的粉飾自己。這回就不光是管自己臉上貼金那麼簡單的事兒了,所有的東西都是我們的用這個天生就黑暗的意識形態,開始瘋狂地執行著他的初衷,把一切都據為己有。

不過呢,我表面上還得粉飾自己;說我這麼幹的目的都是為了你們好,為了你們的發展。保護你們的生命財產的安全,而且大肆的宣傳無私奉獻的精神,並且把我的這個中底層的信眾們調教成一種什麼狀態呢?把他們訓練成只要跟我這個意識形態沾一點邊兒的,產生一小小的互動的呀。那都對於他來講都是一種至高無上的榮譽。

只要被施捨到一丁點兒的好處,那都會感激涕零。如果有人有意見了怎麼辦呢,就搞這個階級對立,把我的這些不服的信眾們分化和瓦解,這個意識形態,它可生出來誕生之日開始它就是黑的,不管你怎麼洗、怎麼粉飾太平,它也是一個基於暴力、殺人放火的理論。

所以呢,產生了邪惡的思想,甚至於傳播和行動,你的這個錯誤的思想是永遠也洗不白的,因為產生之日起它就是黑的呀。雖然不能洗,但是可以改、可以糾錯、可以廢除。洗是洗不白了。不過可以把這個黑的東西徹底地扔進火里燒成灰燼。

這首歌兒最後有這麼一句話,說這個歸根結底還是人類的問題,這個也沒錯。不過,歸根結底還是人類的這個邪惡思想的問題。你產生了這個錯誤、邪惡思想並且行動這條信息呀,在你大腦里產生的那一刻開始它就是黑的,就是目的不純的,更可怕的還不是這個更可怕的是什麼呢?

你明明知道啊這個東西是錯誤的,還要秉承的這種邪惡的思想,並且誓與這種人和這種思想那真是洗不白了。

Where Mei Liu’r detected a pointed critique of mainstream Chinese ideology, others decoded in Dao Lang’s song an overt anti-American message (see, for example, 那英們終於可以松口氣了!刀郎的羅剎海市新解:大刀其實砍向的是美帝,SOHU, 2023年07月26日。) As we noted in the above, the symbolism of the song allowed for numerous interpretations and 見仁見智 — everyone had their own take.

***

Mocking the Gang of Four of Chinese Music on TikTok, Part I

Part II:

- 刀郎新歌《罗剎海市》爆火,抖音网红恶搞“四人帮”二, 2023年7月30日

***

Land of the Rakshasas & the Sea Market

Pu Songling

translated by Yang Xianyi and Gladys Yang

Ma Ji, whose other name was Longmei, was the son of a merchant. A handsome, unconventional lad, he loved singing and dancing; and his habit of mixing with actors and wearing a silk handkerchief on his head made him look as beautiful as a girl and won him the nickname Handsome. At the age of fourteen he entered the prefectural school, where he was winning quite a name for himself when his father, growing old, decided to retire.

“Son,” said the old man, “books cannot fill your belly or put a coat on your back. You had better follow your father’s trade.”

Ma, accordingly, turned his hand to business.

While on a sea voyage with other traders, Ma was carried off by a typhoon. After several days and nights he reached a city where all the inhabitants were appallingly ugly; yet at the sight of him they exclaimed in horror and fled as if he were a monster.

At first Ma was alarmed by their hideous looks; but as soon as he discovered that they were even more afraid of him, he made the most of their fear. Wherever he found them eating or drinking he would rush upon them, and when they scattered in alarm he would regale himself upon all they left.

Later, Ma made his way to a mountain village where the people showed more resemblance to human beings. But they were a ragged, beggarly lot. As he rested under a tree, the villagers gazed at him from a distance, not daring to approach; but realizing after some time that he would not eat them, they began to draw nearer, and Ma addressed them with a smile. Although they spoke different tongues, each side could understand something of what the other said. And when Ma told them that he came from China, the villagers were pleased and spread the news that this stranger was not a cannibal after all. The ugliest of them, however, would turn away after one look at Ma, not daring to draw near. Those who did go up to him had features not entirely different from the Chinese; and as they brought him food and wine Ma asked why they were so afraid of him.

“We were told by our forefathers,” they answered, “that nearly nine thousand miles to our west is a country called China inhabited by the most extraordinary-looking race. We knew this by hearsay only before; but you have provided proof of it.”

Asked the reason for their poverty, they replied:

“In our country we value beauty, not literary accomplishments. Our most handsome men are appointed ministers, those coming next are made governors and magistrates, while the third class have noble patrons and receive handsome pensions for the support of their families. But we are considered as freaks at birth, and our parents nearly always abandon us, only keeping us in order to continue the family line.”

When Ma inquired the name of their country, they told him that it was The Great Kingdom of Rakshas, and that their capital lay about ten miles to the north. And upon Ma’s expressing a desire to be conducted there, they set off with him the next day at cock-crow and reached the city at dawn. The city walls were made of stone as black as ink, with towers and pavilions a hundred feet high. Red stones were used for tiles, and picking up a fragment of one Ma found that it marked his finger-nail just like vermilion. They arrived as the court was rising, in time to see the official equipages.

The villagers pointed out the prime minister, and Ma saw that his ears drooped forward in flaps, he had three nostrils, and his eyelashes covered his eyes like a screen.

He was followed by some riders whom the villagers said were privy councillors.

They informed Ma of each man’s rank; and, although all the officials were ugly, the lower their rank the less hideous they were.

When Ma turned to leave, the citizens of the capital exclaimed in terror and started flying in all directions as if he were an ogre. Only when the villagers assured them that there was nothing to be afraid of did these city people dare stand at a distance to watch. By the time he got back, however, there was not a man, woman or child in the country but knew that a man-monster was there; so all the gentry and officials were curious to see him and asked the villagers to fetch him.

But whatever house he went to, the gate-keeper would slam the door in his face while men and women alike dared only peep at him through cracks and comment on him in whispers. Not a single one had the courage to invite him in.

Then the villagers told him: “There is a captain of the imperial guard here who was sent abroad on a number of missions by our late king. He has seen so much that he may not be afraid of you.”

So they called on the captain, and he was genuinely pleased to meet Ma, treating him as an honoured guest.

Ma saw that his host who looked like a man of ninety, had protruding eyes and a beard like a hedgehog’s.

“In my youth,” said the captain, “His Majesty. sent me to many countries, but never to China. Now at the age of one hundred and twenty, I have been fortunate enough to meet one from your honourable country! I must report this to the king. Living in retirement, I have not been to the court for more than ten years; but I will go there for your sake early tomorrow morning.”

He plied Ma with food and drink, showing him every courtesy.

After they had drunk a few cups of wine, a dozen girls came in to dance and sing in turn.

They looked like devils, but wore white silk turbans and long red dresses which trailed on the ground; and Ma, who could not understand the performance or the songs, found the music weird in the extreme. His host, however, listened appreciatively and asked eventually whether China could boast equally fine music. Receiving an affirmative answer, the old man begged him to sing a few bars. So, beating time on the table, Ma obliged with a tune.

“How strange!” exclaimed the captain, delighted. “It is like the cries of phoenixes or dragons. I have never heard anything resembling this before.”

***

***

The following day the old man went to the court to recommend Ma to the king, who decided to summon him for an audience. But when two ministers declared that Ma’s revolting appearance might shock His Majesty, the king changed his mind. The captain, quite upset, returned to tell Ma of the failure of his mission.

One day, after Ma had stayed with the captain for some time, under the influence of wine he smeared his face with coal dust to perform a sword dance in the role of Zhang Fei.*

[* A famous general in the period of the Three Kingdoms (AD 220-280). He is represented on the traditional stage as a man with a dark face and long whiskers.]

“You must appear before the prime minister with your face painted like that,” urged the captain, who admired this disguise immensely. “He is sure to patronize you, and will certainly procure you a big salary.”

“It is all very well to disguise oneself in fun,” protested Ma with a laugh. “But how can I play the hypocrite for the sake of personal gain?”

He gave in, however, when his host insisted.

Then the captain invited a number of high officials to a banquet, and bade Ma paint his face in readiness.

When the guests arrived and Ma was called out to meet them, they were all amazed.

“How strange!” they cried. “He used to be so ugly; but now he is quite handsome.”

Drinking together, they were soon on the best of terms; and when Ma danced and sang country tunes, they were delighted.

The very next day they recommended him to the king, who summoned him to court to question him about the government of China.

And his diplomatic answers pleased the king so much that a feast was held in Ma’s honour in the pleasure palace.

“I hear that you are skilled in music,” said the king as they were drinking. “Will you perform for me?”

Ma immediately rose to dance and sing vulgar tunes, wearing a white turban in imitation of the girls; and the king was so amused that he promptly appointed him a privy councillor, thereafter dining with him frequently and showing him extraordinary favour.

As time went on, however, the other officials realized that Ma’s face was painted. Wherever he went, people would whisper behind his back or treat him coldly; and such isolation made him uneasy. He addressed a memorial to the throne, requesting permission to retire; but the king refused, granting him only three months’ leave. Ma then went back in a carriage loaded with gold and jewels to the mountain village, where the villagers welcomed him on their knees; and, amid thunderous applause, he distributed his wealth among his old friends.

“We are humble people,” they said, “yet Your Grace has treated us so kindly! When we go to the Sea Market, we shall look for some precious objects to repay you.”

Ma asked where this market was.

“It is a market in the middle of the ocean,” they told him, “where mermaids from all the seas bring their jewels and merchants from all the twelve countries around come to trade. Deities frolic there among the coloured clouds and tossing waves; but rich men and high officials will not risk the journey, commissioning us to buy treasures for them instead. The time for the market is at hand.”

“How do you know the date?” demanded Ma.

They explained that red birds flew over the ocean seven days before the market; but when Ma asked them when they were going to start, and whether he might go with them, the villagers begged him not to take such a risk.

“I am a sailor,” protested Ma. “The wind and waves hold no fears for me.”

Soon after this, people came with money to buy goods, then the villagers loaded their wares and boarded a vessel capable of carrying several dozen men. This was a flat-bottomed boat surrounded by a high railing; and with ten men at the oars it cut through the water like an arrow. After a voyage of three days they could make out in the distance, between the moving clouds and water, pavilions rising one behind the other and busy traffic of trading junks. By and by they came to a city, which had walls made of bricks as long as a man’s body, and a citadel towering to the sky. Here they moored their boat and went ashore to inspect the treasure displayed in the market — precious stones which dazzled the eye, seldom seen in the world of men.

Then a young man rode up, and all the market people hastened to make way for him, crying that this was the Third Prince of Dongyang. The prince’s eye fell on Ma as he passed, and he exclaimed:

“This stranger is not from these parts!”

Some of his outriders came to ask Ma where he hailed from; and Ma, bowing at the roadside, told them.

“A kind fate has favoured us with your visit!” cried the prince with a smile.

He gave Ma a horse and bade him ride with them out of the West Gate. Upon reaching the shore, their steeds neighed and leapt into the waves; but as Ma cried out in dread the sea parted to form a wall of water on either side; and presently a palace came into sight. It had rafters of tortoise-shell and tiles of fish scales, while its dazzling walls of bright crystal reflected all around. Here they dismounted, and Ma was led into the presence of the dragon king who was seated on his throne.

“In the market I came across a talented man from China,” the prince reported. “I have brought him here to Your Majesty.”

Ma stepped forward to bow to the ground.

“You are a great scholar, sir,” said the dragon king, not inferior to Qu Yuan, Song Yu and other poets of old. May I ask you to compose a poem on our Sea Market? Pray do not refuse.”

Having bowed his agreement, Ma was given a crystal inkstone, dragon’s beard brush, paper as white as snow, and ink as fragrant as orchids. Without hesitation he dashed off over one thousand characters which he presented to the dragon king, who marked the rhythm with one hand as he read the poem.

“Your genius sheds glory on our watery kingdom, sir,” said the king.

He then summoned all his dragon kinsmen to feast at the Palace of Rosy Clouds, and, when the wine had circulated freely, raising a goblet in one hand he said to Ma: “My beloved daughter is still unmarried. I would like to entrust her to you, if you have no objection.”

Ma rose, blushing, and stammered out his thanks. At once the dragon king gave an order to his attendants, and presently palace maids led in the princess whose jade pendants tinkled as she walked.

Trumpets and drums sounded for the wedding ceremony, and Ma, stealing a look at his bride, found her divinely beautiful.

After the ceremony the princess left the hall; and, the feast at an end, two maids holding painted candles led Ma into the inner palace.

There the princess was sitting, magnificently arrayed. The bridal bed was of coral, studded with jewels, the curtains were adorned with coloured feathers and decked with huge pearls, and the bedding was soft and scented.

The next morning at dawn, when girl attendants entered to offer their services, Ma got up and went to thank the king. He was duly installed as the royal son-in-law and appointed an official; copies of his poem were despatched to all the seas, and the dragon rulers of the different oceans sent special envoys to convey their congratulations to the king and invite Ma to feast with them. Then, in embroidered robes and riding on a green-horned dragon, he sallied forth with a magnificent equipage, accompanied by dozens of knights on horseback who carried carved bows and white staffs.

They formed a glittering cavalcade, with musicians on horseback and in chariots playing harps and jade flutes.

Thus in three days Ma passed through the different seas, and his fame spread throughout the marine world.

In the palace grew a jade tree, so large that a man could barely encircle it with his arms. The trunk was as transparent as glass and pale yellow in the centre; the branches were slighter than a human arm; and the jasper leaves, little thicker than a coin, cast a fine checkered shade. Ma and his bride often recited poems under this tree, which bore a profusion of blossoms like gardenias. Whenever a petal fell it made a tinkling sound, and picked up proved to be as lovely and bright as carved red agate. Often a strange bird would come to sing here. Its feathers were gold and green, its tail longer than its entire body, and its flutelike voice so clear and plaintive that none who heard it could fail to be moved. Whenever Ma listened to its song, he was carried back in spirit to his native land.

“I have been away from my home and my beloved parents for three years,” he told the princess. “The thought of this makes tears well to my eyes and perspiration start out on my back. Will you accompany me home?”

“An immortal must not live like a mortal,” she replied.

“I cannot go with you, but neither would I let the love of husband and wife stand in the way of your love for your parents. Let us consider this again later.” Hearing this, Ma could not refrain from tears, and the princess sighed.

“It is clear that you cannot have both wife and parents,” she said.

Next day, when Ma returned to the palace from an outing, the dragon king addressed him.

“I hear that you are longing for your home,” he said. “Would you like to leave tomorrow?”

Ma thanked the king earnestly.

“Your servant came here as a stranger,” he said, “yet you have conferred such honours upon me that I am overwhelmed with gratitude. I shall go to pay my family a short visit, but I hope to return again.”

That evening when the princess prepared a parting feast, Ma spoke once more of his proposed return.

“Ah, no,” said she. “We can never meet again.”

Ma, hearing this, was overcome with grief.

“To go back to your parents shows true filial piety,” the princess assured him. “Fate holds endless encounters and separations, and a hundred years pass like a single day; then why should we give way to tears like children? I mean to remain true to you, and I am sure you will be faithful to me. Loving each other in far distant places, we can still be one in spirit: there is no need to remain together morning and night. If you break this pledge, your next marriage will be unlucky; but if you need someone to look after you, you can take a maid as your concubine. I have something to ask you, too. I am now with child, and I would like you to choose a name for it.”

“If it is a girl,” said Ma, “call her Dragon Palace. If a boy, Happy Sea.”

Then the princess asked him for a token, and he gave her a pair of red cornelian lilies he had obtained in the land of the Rakshas.

“Three years from now, on the eighth day of the fourth moon,” she charged him, “sail into the south sea and I shall give you your child.” Then she handed him a fish-scale bag filled with jewels, saying: “Keep this well. It will support your family for generations.”

At dawn the dragon king held a farewell feast for Ma and bestowed many other gifts on him, after which Ma bid them all adieu and left the palace, escorted by the princess in a carriage drawn by white rams. But as soon as he reached the ocean’s shore and dismounted the princess said farewell and turned swiftly away, the salt waves closing over her as she disappeared. Then Ma returned home.

Everybody believed that Ma had been lost at sea, so his family was amazed at his return. His parents were well, but his wife had married again; and Ma realized that when the dragon princess had spoken of keeping faith, she must have known this. His father urged him to marry another wife, but he refused, taking only a concubine. He kept in mind the date, and three years later sailed south again until he saw two children on the ocean’s bosom, gambolling and frolicking upon the waves. As he drew near and leant over them, one child seized his arm with a laugh and leapt on to his knee, while the other cried out as if to reproach him for neglecting it. When he had pulled the second child aboard too, he saw that one was a boy and the other a girl. They were beautiful children.

Fastened to their coloured hats were his red cornelian lilies, and on the boy’s back he found an embroidered bag containing the following letter:

I know that your parents are well. Three years have slipped quickly away while we have been separated by the ocean, with no bluebird to carry our messages. I long for you in my dreams, gazing in grief at the azure sky. Yet even the goddess of the moon pines in loneliness under the cassia tree, and the Weaving Maid grieves as she watches the Milky Way which separates her from her love. Why should I alone enjoy wedded happiness? This thought makes me smile at my tears.

Two months after you left I gave birth to twins, who can now prattle and laugh in my lap, and hunt for dates and pears. Since they can manage without a mother now, I am sending them to you; and you will know them by the red cornelian lilies which you gave me.

When you take them on your knee, you may imagine that I am beside you. It comforts me to know that you have kept faith; and I too shall remain true to you until death. I no longer rouge or powder my face or darken my eyebrows before the mirror. You are the wanderer and I the loving wife at home; but even though we cannot be together, we remain husband and wife.

I feel it is wrong, though, that your parents should have their grandchildren without meeting their daughter-in-law; so next year when your mother leaves the world, I shall come to the burial and pay my respects.

After that, if all goes well with Dragon Palace it may be possible to meet again; and if Happy Sea remains well, a path may be found for a visit. Please take good care of yourself.

This letter cannot express all that I want to say.

Ma read and reread this letter, weeping, until the two children put their arms around his neck and said:

“Father! Can we go home?”

Pierced to the heart, he fondled them, asking:

“Where is our home?”

The children whimpered, and cried for their mother. And Ma gazed at the wild expanse of ocean stretching boundless to the horizon; but no princess appeared, nor any road through the misty waves. There was nothing for it but to take the children home.

Knowing now that his mother’s death was near, Ma made everything ready for her funeral, and planted a hundred pine trees in the ancestral graveyard. The next year, when his mother died and the interment took place, a woman appeared beside the grave in deep mourning.

As they gazed at her in wonder, a wind

sprang up, thunder crashed and rain poured down, and the woman disappeared. But many of the pine trees planted by Ma, which had withered, revived after this rain.

When Happy Sea grew bigger, he still missed his mother; and once he disappeared suddenly into the sea, returning only several days later. But Dragon Palace, being a girl, could not leave home; and she often wept in her room. One day the sky grew dark, and the dragon princess entered Ma’s house to comfort her daughter.

“You will have your own home soon,” she said. “Don’t cry, child.”

She gave the girl as her dowry a tree of coral eight feet high, a packet of Baroos camphor, a hundred pearls and two gold boxes set with precious stones. When Ma heard of her coming, he rushed in and took her hands, weeping. But with a clap of thunder the princess vanished.

The recorder of these marvels comments:

Men must put on false, ugly faces to please their superiors — such is the hypocritical way of the world. The foul and hideous are prized the world over. Something of which you feel a little ashamed may win praise; while something of which you feel exceedingly ashamed may win much higher praise. But any man who dares to reveal his true self in public is almost certain to shock the multitude and make them shun him. Where, indeed, can that fool of Lingyang* take his priceless jade to weep? Alas! I shall seek my fortune in castles in the clouds and mirages of the sea.

[* A man of Lingyang presented a piece of uncut jade to the King of Chu in the Spring and Autumn period (722-48 BC); but the king, not recognizing its value, chopped off the donor’s feet in anger.]

***

Source:

- Pu Songling, Selected Tales of Liaozhai, trans. Yang Xianyi and Gladys Yang, Beijing: Panda Books, Chinese Literature, 1981, pp.62-75. For the Chinese text, see 蒲松齡, 羅剎海市

***