Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium

Appendix XXV

贖

‘… it’s like a child at the beach. You give them a shovel. They’ll make a hole and a hill and work at it all day. They’ll have a grand time. And then the tide comes in and the waves bring down the little hill. The little thing is trampled on. But the tide doesn’t take what happened, what they were doing, what’s inside. That’s preserved forever.’

— Father Michael Doyle, quoted in Chris Hedges, The Good Priest

The theme of China Heritage Annual 2020 was ‘viral alarm’. It was inspired by an essay by Professor Xu Zhangrun 許章潤 written in response to the Wuhan coronavirus and the epidemic that was unfolding in its wake (see Xu Zhangrun,Viral Alarm — When Fury Overcomes Fear, China Heritage, 24 February 2020). We reprinted that essay as ‘blank-page protests’ swept China in late November 2022 (see Fear, Fury & Protest — three years of viral alarm, 27 November 2022).

In December 2020, we concluded Viral Alarm with another essay by Xu Zhangrun. I titled the translation of that essay Composed of Eros & of Dust, which is a line from September 1, 1939, a poem by W.H. Auden. That poem reads in part:

Defenseless under the night

Our world in stupor lies;

Yet, dotted everywhere,

Ironic points of light

Flash out wherever the Just

Exchange their messages:

May I, composed like them

Of Eros and of dust,

Beleaguered by the same

Negation and despair,

Show an affirming flame.

Two years later, I thought of Auden’s poem, and of Xu Zhangrun’s fate, during a candlelight vigil at Civic Square, Wellington, New Zealand held to mourn the victims of the 24 November Urumqi fire. We gathered, too, to celebrate the protests that had swept China and Chinese communities worldwide in response to Urumqi. Ours was one of those ‘ironic points of light’ around the world, and although ‘beleaguered by … negation and despair’; we too felt that by coming together in Wellington we could, in some small way, ‘show an affirming flame.’

At our vigil, Keith Ng, a Kiwi whom I had met as a result of the kerfuffle surrounding Chinese Language Week in September 2022, read out the English translation of It’s My Duty, a prose-poem composed by a Chinese student in New York that had been recited at a vigil at Columbia University on 29 November 2022. I followed Keith’s rendition by reading out the original Chinese text.

We also listened as Chinese students, workers and community members offered their thoughts on recent events. Some reflected on their unthinking complicity with ‘Silent China’; some even expressed the hope that they would do better in the future. Significant too was the fact that we were mourning the death of innocent Uyghurs in far-flung Xinjiang. members of a subjugated ethnicity whose cruel fate under a ‘state of exception’ mandated by Beijing has long been ignored or denied by people in China Proper as well as being contested by many overseas.

Ours was a modest and low-key gathering, something that reflected the way things are done in Aotearoa. Nonetheless, it was a deeply moving moment, one that I was fortunate to share with two good friends in Chinese letters — one a classical scholar and renowned teacher whom I met in Beijing shortly after Mao Zedong’s death in 1976 and the other an historian, unconventional thinker and linguist extraordinaire whom I had known since their days as a doctoral student at the Australian National University in Canberra. Together we listened as others told us what this moment of ‘awakening’ meant to them. As we did so, I was taken back to discussions that I had with friends in China and Hong Kong on that subject in the 1970s, the 1980s and ever since.

When translating It’s My Duty the previous night I recalled a passage in The Good Priest, an essay written by Chris Hedges to memorialise Father Michael Doyle who had passed away in early November. Hedges’s observations about ‘heroic men and women who — against overwhelming odds — rose up to fight lonely and often losing battles on behalf of the oppressed’ was, I felt, also true of the men and women of conscience whose names lies at the heart of ‘It’s My Duty’. As Hedges says:

‘When set against the crushing poverty, environmental degradation, corporate abuse and despair they opposed, the victories they amassed were often minuscule. And yet, to them, and to the people they were able to support, these victories were immense. They kept alive kindness, community, decency, hope and justice. They provided another way to speak about the world. They reminded us that our primary task in life is to care for others. These moral giants, by their very presence and steadfast refusal to surrender, damned the avarice, lust for power, hedonism and violence that define corporate culture.’

For this passage to be relevant to the People’s Republic of China under Xi Jinping, you only have to change the words ‘corporate culture’ to ‘the party-state’.

To continue our celebration of the ‘Chinese awakening of 2022’, which began with the solitary heroism of Peng Zaizhou (see Awakenings — a Voice from Young China on the Duty to Rebel) here we offer two works, one a speech made by Chris Hedges during the Occupy Wall Street Protests at Zuccotti Park, New York, September-November 2011, the Confession, Redemption, and Death, an essay that I composed in late 1989 in an attempt to record my understanding of the early career and activism of Liu Xiaobo, as well as his participation in the Protest Movement of that year.

Separated by time, geography and now by the veil of death, Chris Hedges and Liu Xiaobo 劉曉波 share much in common. When Hedges speaks about hope, he articulates a view that resonates with Liu Xiaobo’s own deathless pursuit. It also chimes the with defiance of dissidents like Xu Zhangrun today:

‘Hope does not come with the right attitude. Hope is not about peace of mind. Hope is an action. Hope is doing something. The more futile, the more useless, the more irrelevant and incomprehensible an act of rebellion is, the vaster and the more potent hope becomes. Hope never makes sense. Hope is weak, unorganized and absurd. Hope, which is always nonviolent, exposes in its powerlessness the lies, fraud and coercion employed by the state. Hope does not believe in force. Hope knows that an injustice visited on our neighbor is an injustice visited on us all. Hope posits that people are drawn to the good by the good. This is the secret of hope’s power and it is why it can never finally be defeated. Hope demands for others what we demand for ourselves. Hope does not separate us from them. Hope sees in our enemy our own face.’

I believe that ‘doing something’ of my own over the years — writing, translating, teaching, offering advice to officialdom, engaging with the media and the public and making films — reflects a lifelong attempt to deepen my own understanding of our shared condition and in that process to offer what I have gleaned thereby to others. In recent years, these efforts have included the work that China Heritage has published on the Hong Kong Uprising and our ongoing account of the ‘rebellion in writing’ of Xu Zhangrun. It also includes the present series, Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium.

***

The Protest Movement of April-June 1989 revealed the existence of a voluble and courageous Young China. As we have noted elsewhere, when addressing an audience at the Hong Kong YMCA some sixty years earlier, in February 1927, the writer Lu Xun had lamented the fact that, despite ten years of literary revolution, people in modern China had still not found a voice of their own. They were living in what he called 無聲的中國 wúshēngde Zhōngguó, ‘a voiceless China’. ‘Youth’, he said:

‘must first transform China into a China with a voice. They must speak boldly, move forward courageously, forget all considerations of personal advantage, push aside the ancients, and express their authentic feelings.’

Our work over the past decade — through China Heritage Quarterly, The China Story Journal and China Heritage — flies in the face of what, under Xi Jinping’s aegis, has been a vast regime of censorship, censoriousness and silencing.

‘… although the People’s Republic is anything but voiceless under Xi Jinping, it has paradoxically become silent. Censorship and fear are commonplace, as has so often been the case in the past, and there is cowed conformity. Instead of celebrating a polyphony of voices, Xi Jinping and his propagandists extol Official China, one that speaks in a monotone allowing only for one, unified narrative: “The China Story.” In this story dissent has been quelled and heterodox views eliminated.

‘All the while the Other China, made up of an ebullient cacophony existing in parallel with the Communist Party-state, struggles on; it is a century-long struggle identified by writers like Lu Xun who have extolled the authentic voices of people wanting to be heard. During periods of political darkness such as today, this Other China, like magma coursing under a hardened mantle, flows through conversations and private exchanges. It takes a myriad of forms in acts of quotidian resistance, personal protests straining to affirm decency in the face of indifference, and outright hostility.’

— from Silent China & Its Enemies, 23 November 2017

The Blank Page Protests of November 2022 gave expression to frustration and a range of demands voiced by people from all walks of life in dozens of Chinese cities and on campuses throughout the country. After a dolorous decade dominated by Xi Jinping and his comrades, those protests, along with the speeches long and short, commentaries, videos, artwork and memes produced during a moment of rebellion offered a moment of redemptive activism. This was true not only for people in China, but for Chinese people everywhere. The protests are a demonstration of what, for long years, we have referred to as The Other China.

In gatherings both in China and throughout the world, speeches have been made and statements recorded in which individuals by speaking about their awakening in confessional terms. (On this ‘political awakening’, see, for example, Covid Protests in China Raise Hope for Solidarity Among Activists Abroad, The New York Times, 5 December 2022.) In doing so, and in taking action to assert their sense of self, dignity and rights, these protesters have unconsciously repeated the defiant gesture of Liu Xiaobo in 1989. Xiaobo reflected that his previous stand-offish cynicism and intellectual superiority had cut him off from the temper of the times. In Tiananmen Square he readily confessed his limitations and, through his words and actions, sought redemption.

The redemption offered by the Blank Page Protests is accessible to all: it is for those who enmeshed in a skein of official lies have chosen survival over speaking out; it is for those who are actively complicit in a system participation in which comes at the cost of one’s conscience; it is for those students of China who would give in to the absurdities of Communist Party essentialism about who ‘the Chinese are’, the fictitious history that they promote and the worldview that it advocates that places the ambitions of the party-state above all else. This moment of redemption may also rescue the reputation of people who are all too readily dismissed as having no spiritual independence, agency or individual worth. Nonetheless, it is impossible to gauge what, if anything, has really changed. As the Tsinghua University political scientist Liu Yu 劉瑜 reminded readers in 2018: ‘Throughout history countless tragedies have been born of silence’. Moreover, this time around members of China’s reliably voluble intelligentsia has been conspicuous in their absence. As Liu Xiaobo pointed out over three decades ago, even at the height of liberalization, mainland intellectuals were feign to recognise the contribution of dissidents, be they in China or overseas. After June Fourth, Liu himself was relegated to the untouchables and, as such, was not even recognised by mainstream liberal thinkers like Xu Jilin et al as belonging to the same caste. That is why, today, figures who have dared to speak out, people like Xu Zhangrun, Rong Jian and Guo Yuhua, are effectively written out of the chronicles of contemporary Chinese thought.

As the dead party-state-army leader Jiang Zemin (江澤民, 1926-2022), a man who enabled the rise of Xi Jinping and his dour regime, is eulogised, immolated and interred in Beijing, I prefer to recall the astrophysicist Fang Lizhi (方勵之, 1936-2012), a full-time scientist whose conscience led him to become a part-time activist. He was purged as part of Deng Xiaoping’s attack on ‘bourgeois liberalisation’ that followed in the wake of protests in late 1986 during which university students called for democracy, freedom and an end to censorship. In the editorial introduction to It’s My Duty we noted that Jiang Zemin’s alacrity in dealing with the demonstrations in Shanghai was the prelude to his rise to lead China’s party-state-army in 1989.

Dismissed from his job as vice-president of the Chinese University of Science and Technology in Hefei, Anhui province and denounced in the media in January 1987, Fang Lizhi continued to speak out. His example was a challenge both to his fellow scientists and to intellectuals. It also challenged lazy perceptions both in China and internationally regarding the post-Mao reform era. When the Italian journalist Tiziano Terzani asked Fang Lizhi how he saw his mission, he answered ‘democratization’. Fang went on to say:

‘Unless individual human rights are recognized there can be no true democracy. In China the very ABC of democracy is unknown. We have to educate ourselves for democracy. We have to understand that democracy isn’t something that our leaders can hand down to us. A democracy that comes from above is no democracy, it is nothing but a relaxation of control. The fight will be intense. But it cannot be avoided.’

— from Seeds of Fire: Chinese Voices of Conscience, 2nd ed., New York: Hill and Wang, 1988, p.329

Fang was of the opinion that China’s intelligentsia, long forced into complicity with Party rule from the time of the Anti-Rightist purge of 1957 (which was overseen by none other than Deng Xiaoping), had to step up. ‘If we fail to achieve this,’ Fang said, ‘China can hardly expect to become a truly developed, modern country.’

[Note: For details of Fang’s pivotal role in the 1989 demonstrations, see Xu Zhangrun at Sixty, 25 October 2022; and for the ‘Fang challenge’, see my essay ‘The man who speaks too much, too often’, Far Eastern Economic Review, 22 October 1987; and, 對《方勵之的挑戰》的補充,《九十年代月刊》,1988年7月.]

In Confession, Redemption, and Death, excerpted below, we quote Liu Xiaobo’s declaration that:

“I’m quite opposed to the belief that China’s backwardness is the fault of a few egomaniac rulers. It is the doing of every Chinese. That’s because the system is the product of the people. All of China’s tragedies are authored, directed, performed, and appreciated by the Chinese themselves. There’s no need to blame anyone else. Anti-traditionalism and renewal must be undertaken by every individual, starting with themselves. I’m appalled by [philosopher] Li Zehou’s comment that we shouldn’t oppose tradition or otherwise we’ll negate ourselves. Following the fall of the Gang of Four, everyone has become a victim, or a hero who struggled against the Gang. Bullshit! What were they all doing in the Cultural Revolution? Those intellectuals produced the best big-character posters of all. Without the right environment, Mao Zedong could never have done what he did.”

‘… What was important [for Liu] was the desire to confess, to find redemption in acts that would negate the disinterested and lethargic attitude to the past, and through that action to find self-fulfillment. Liu had been critical of the ‘Confucian personality,’ the Kongyan renge [孔顏人格], promoted by such contemporary philosophers as Li Zehou, and was equally dismissive of meaningless self-sacrifice such as that made by the Tang poet Sikong Tu, who starved himself to death out of loyalty to his lord. Equally, he felt that calls by Chinese intellectuals over the years to achieve freedom always had a plaintive tone about them.

‘Like Fang Lizhi, he emphasized that freedom was a natural right and not something to be bestowed by the powerful. ‘For so many years now,’ he wrote, ‘the Chinese have been on their knees [before an emperor] begging for freedom.’ ’

***

Thirty three years after Liu Xiaobo returned to Beijing from New York to throw himself into the 1989 protests, an editorial in The New York Times observed that the Blank Page Protests of November 2022 also allowed people to ‘see the Chinese people anew’:

For now, the protesters in China have made their voices heard under very difficult conditions. They demonstrated the value of protest and dissent — freedoms that many in the world hold dear. At a time of geopolitical hostility, they offer an opportunity to Americans and others to better understand the diversity of views that exists within China and to see the Chinese people anew.

— What the Chinese People Are Revealing About Themselves, 3 December 2022

***

This appendix should be read in conjunction with the following material in Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium:

- Introduction 瞽 — You Should Look Back, 1 February 2022

- A Tally 單 — The Threnody of Tedium, 18 February 2022

- Chapter Twenty 咒 — A Hosanna for Chairman Mao & Canticles for Party General Secretary Xi, 22 October 2022

- Chapter Twenty-one 醒 — Awakenings — a Voice from Young China on the Duty to Rebel, 14 November 2022

- Chapter Twenty-two 官逼民反 — Fear, Fury & Protest — three years of viral alarm, 27 November 2022

- Appendix XXIII 空白 — How to Read a Blank Sheet of Paper, 30 November 2022

- Appendix XXIV 職責— It’s My Duty, 1 December 2022

- Appendix XXVI 囿 — A Ray of Light, A Glimmer of Hope — Li Yuan talks to Jeremy Goldkorn & to a Shanghai protester, 10 December 2022

- Appendix XXVII 謔— When Zig Turns Into Zag the Joke is on Everyone, 12 December 2022

— Geremie R. Barmé, Editor, China Heritage

Distinguished Fellow, Asia Society

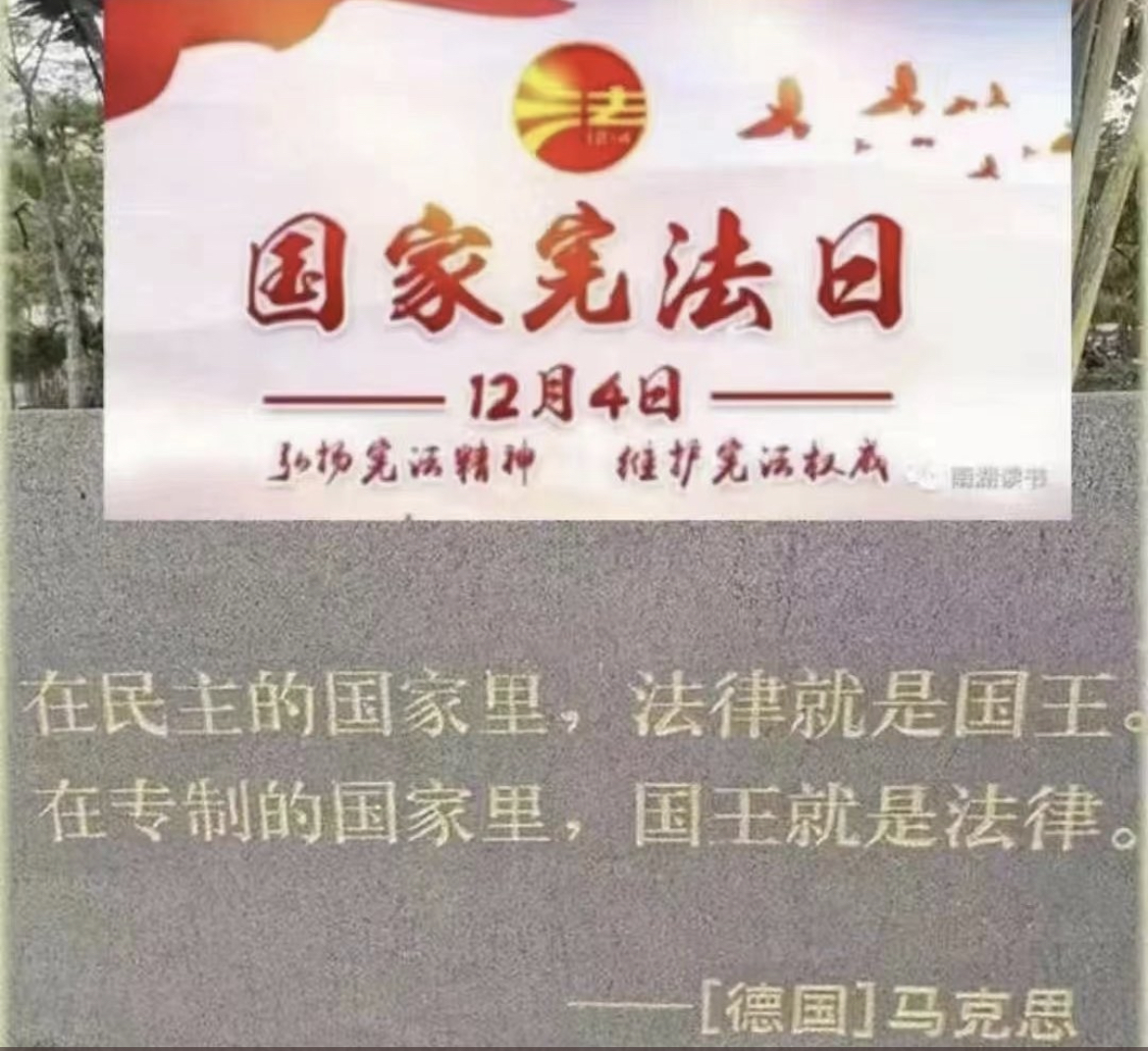

4 December 2022

China’s National Constitution Day

國家憲法日

***

From Viral Alarm — China Heritage Annual 2020:

- The innocent cry to Heaven. The odour of such a state is felt on high., 1 October 2020

- The Heart of The One Grows Ever More Arrogant and Proud, 10 March 2020

***

To sin by silence, when we should protest,

Makes cowards out of men. The human race

Has climbed on protest. Had no voice been raised

Against injustice, ignorance, and lust,

The inquisition yet would serve the law,

And guillotines decide our least disputes.

The few who dare, must speak and speak again

To right the wrongs of many.

— from Protest, by Ella Wheeler Wilcox

***

Hope, Real Hope, Is About Doing Something

Chris Hedges

29 November 2010

On Dec. 16 I will join Daniel Ellsberg, Medea Benjamin, Ray McGovern and several military veteran activists outside the White House to protest the futile and endless wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Many of us will, after our rally in Lafayette Park, attempt to chain ourselves to the fence outside the White House. It is a pretty good bet we will all spend a night in jail. Hope, from now on, will look like this.

Hope is not trusting in the ultimate goodness of Barack Obama, who, like Herod of old, sold out his people. It is not having a positive attitude or pretending that happy thoughts and false optimism will make the world better. Hope is not about chanting packaged campaign slogans or trusting in the better nature of the Democratic Party. Hope does not mean that our protests will suddenly awaken the dead consciences, the atrophied souls, of the plutocrats running Halliburton, Goldman Sachs, ExxonMobil or the government.

Hope does not mean we will halt the firing in Afghanistan of the next Hellfire missile, whose explosive blast sucks the oxygen out of the air and leaves the dead, including children, scattered like limp rag dolls on the ground. Hope does not mean we will reform Wall Street swindlers and speculators, or halt the pillaging of our economy as we print $600 billion in new money with the desperation of all collapsing states. Hope does not mean that the nation’s ministers and rabbis, who know the words of the great Hebrew prophets, will leave their houses of worship to practice the religious beliefs they preach. Most clerics like fine, abstract words about justice and full collection plates, but know little of real hope.

Hope knows that unless we physically defy government control we are complicit in the violence of the state. All who resist keep hope alive. All who succumb to fear, despair and apathy become enemies of hope. They become, in their passivity, agents of injustice. If the enemies of hope are finally victorious, the poison of violence will become not only the language of power but the language of opposition. And those who resist with nonviolence are in times like these the thin line of defense between a civil society and its disintegration.

Hope has a cost. Hope is not comfortable or easy. Hope requires personal risk. Hope does not come with the right attitude. Hope is not about peace of mind. Hope is an action. Hope is doing something. The more futile, the more useless, the more irrelevant and incomprehensible an act of rebellion is, the vaster and the more potent hope becomes. Hope never makes sense. Hope is weak, unorganized and absurd. Hope, which is always nonviolent, exposes in its powerlessness the lies, fraud and coercion employed by the state. Hope does not believe in force. Hope knows that an injustice visited on our neighbor is an injustice visited on us all. Hope posits that people are drawn to the good by the good. This is the secret of hope’s power and it is why it can never finally be defeated. Hope demands for others what we demand for ourselves. Hope does not separate us from them. Hope sees in our enemy our own face.

Hope is not for the practical and the sophisticated, the cynics and the complacent, the defeated and the fearful. Hope is what the corporate state, which saturates our airwaves with lies, seeks to obliterate. Hope is what our corporate overlords are determined to crush. Be afraid, they tell us. Surrender your liberties to us so we can make the world safe from terror. Don’t resist. Embrace the alienation of our cheerful conformity. Buy our products. Without them you are worthless. Become our brands. Do not look up from your electronic hallucinations to think. No. Above all do not think. Obey.

W.H. Auden wrote:

Faces along the bar

Cling to their average day:

The lights must never go out,

The music must always play,

All the conventions conspire

To make this fort assume

The furniture of home;

Lest we should see where we are,

Lost in a haunted wood,

Children afraid of the night

Who have never been happy or good.

The powerful do not understand hope. Hope is not part of their vocabulary. They speak in the cold, dead words of national security, global markets, electoral strategy, staying on message, image and money. The powerful protect their own. They divide the world into the damned and the blessed, the patriots and the enemy, the rich and the poor. They insist that extinguishing lives in foreign wars or in our prison complexes is a form of human progress. They cannot see that the suffering of a child in Gaza or a child in the blighted pockets of Washington, D.C., diminishes and impoverishes us all. They are deaf, dumb and blind to hope. Those addicted to power, blinded by self-exaltation, cannot decipher the words of hope any more than most of us can decipher hieroglyphics. Hope to Wall Street bankers and politicians, to the masters of war and commerce, is not practical. It is gibberish. It means nothing.

I cannot promise you fine weather or an easy time. I cannot assure you that thousands will converge on Lafayette Park in solidarity. I cannot pretend that being handcuffed is pleasant. I cannot say that anyone in Congress or the White House, anyone in the boardrooms of the corporations that cannibalize our nation, will be moved by pity to act for the common good. I cannot tell you these wars will end or the hungry will be fed. I cannot say that justice will roll down like a mighty wave and restore our nation to sanity. But I can say this: If we resist and carry out acts, no matter how small, of open defiance, hope will not be extinguished. If all we accomplish is to assure a grieving mother in Baghdad or Afghanistan, a young man or woman crippled physically and emotionally by the hammer blows of war, that he or she is not alone, our resistance will be successful. Hope cannot be sustained if it cannot be seen.

Any act of rebellion, any physical defiance of those who make war, of those who perpetuate corporate greed and are responsible for state crimes, anything that seeks to draw the good to the good, nourishes our souls and holds out the possibility that we can touch and transform the souls of others. Hope affirms that which we must affirm. And every act that imparts hope is a victory in itself.

Defenseless under the night

Our world in stupor lies;

Yet, dotted everywhere,

Ironic points of light

Flash out wherever the Just

Exchange their messages:

May I, composed like them

Of Eros and of dust,

Beleaguered by the same

Negation and despair,

Show an affirming flame.

***

Source:

- Chris Hedges, Real Hope Is About Doing Something, Truthdig, 24 November 2010

Even If You Don’t Want to Be Up Front

Communication University of China, Nanjing

***

The Black Hand of Insidious Foreign Forces

In one of several viral videos on social media, demonstrators in Beijing are seen ridiculing suggestions that “foreign forces” are to blame for protests sweeping China against the government’s zero-COVID policy.

“Please, may I ask: did ‘foreign forces’ set the fire in Xinjiang?” one protester asks in reference to an apartment fire that killed at least 10 people amid reports they had been locked inside because of COVID-19 restrictions.

“Did the bus in Guizhou get overturned by ‘foreign forces?’” the protester continues, referring to an incident in September in which 27 people died while being transported to a quarantine center.

The video begins with an unidentified young man in a facemask addressing participants at an evening protest through a bullhorn. “I just got word that we need everyone to pay attention: right here, right now, among this crowd, there are anti-China forces from abroad,” the man says.

The claim is quickly rejected by people in the crowd, many of them unmasked, who hurl back a stream of disdainful remarks.

“Were you referring to Marx, Engels, Lenin and Stalin as ‘foreign forces?’” one shouts back, referring to the ideological founders and Soviet practitioners of communism.

Another demonstrator, clad in a puffy white winter jacket, asks the crowd: “Did we all decide to come out and gather here because foreign forces urged us to do so?”

“No!” comes the resounding answer from the crowd.

The man continues: “We can’t even access the worldwide net [that exists] outside of China! How can you say we have anything to do with foreign forces? How could foreign forces even get in touch and communicate with us?”

Another protester shouts: ““There’s only ‘domestic forces’ that are banning us from gathering together!”

The man in the white jacket shouts again: “At present, are we allowed to travel abroad, or access foreign websites?”

“We’re allowed none of this,” the crowd replies.

“All we want is freedom,” shouts another.

— Natalie Liu, Beijing Protesters Ridicule Claims of Foreign Hand in Protests, VOA, 30 November 2022

‘The charge is an old one that has been used to tar Chinese protestors for decades. In late 1989, then-General Secretary of the CCP Jiang Zemin, who died this week, insinuated that the democracy movement of that spring and summer was the product of “hostile international forces.” Since then, the charge has been used to discredit any expression deemed hostile to the Party-state. To name but two more recent examples, a lesbian marriage proposal in 2016 and protests over the cover-up of a Chengdu teenager’s suicide in 2021 were both tagged as products of “foreign forces.” Even state institutions are not exempt from the charge; an inspector at the powerful Central Commission for Discipline Inspection accused a top state-run think tank of being under the influence of “foreign forces” in 2014. The charge has become something of a meme online, with a popular joke remarking how “busy” foreign forces must be to insert themselves into such a range of activities across China.’

— Alexander Boyd, Protestors Scoff at “Foreign Forces” Accusations, China Digital Times, 2 December 2022

[Note: Those familiar with modern Chinese history will appreciate the above exchange and comment. From the 1930s, Stalin’s version of Marxism-Leninism was decried by political opponents of the Chinese Communist Party as a murderous foreign ideology aimed at destroying Chinese culture and society. The fact that for decades the Comintern gave succour — and hard cash — to the Chinese Communists in support of ‘world revolution’ served to confirm people’s worst fears. After 1949, independent critics repeated the charge time and again, with tragic results.

As Bao Tong observed, ‘After Mao Zedong China was no longer China.’

Following his detention in 1989, Liu Xiaobo was denounced as one of the ‘black hands’ behind the Tiananmen Protests acting at the beck and call of invidious ‘foreign forces’ which were determined to overthrow the Communist Party so China could become a vassal of the West.]

***

This was such a brilliant video I subtitled it so more people can watch it. Beijing students' response last night to accusations that there are 'foreign forces' at play in this weekend's protests

'The foreign forces you are talking about – are they Marx and Engels?' https://t.co/umdFaVhz2s pic.twitter.com/RoohkFaZgE

— Cindy Yu (@CindyXiaodanYu) November 28, 2022

Excerpts from

Confession, Redemption, and Death:

Liu Xiaobo and the Protest Movement of 1989

Geremie Barmé

December 1989

There should be room for my extremism; I certainly don’t demand of others that they be like me…I’m pessimistic about mankind in general, but my pessimism does not allow for escape. Even though I might be faced with nothing but a series of tragedies, I will still struggle, still show my opposition. This is why I like Nietzsche and dislike Schopenhauer.

— Liu Xiaobo, November 1988

I

FROM 1988 to early 1989, it was a common sentiment in Beijing that China was in crisis. Economic reform was faltering due to the lack of a coherent program of change or a unified approach to reforms among Chinese leaders and ambitious plans to free prices resulted in widespread panic over inflation; the question of political succession to Deng Xiaoping had taken alarming precedence once more as it became clear that Zhao Ziyang was under attack; nepotism was rife within the Party and corporate economy; egregious corruption and inflation added to dissatisfaction with educational policies and the feeling of hopelessness among intellectuals and university students who had profited little from the reforms; and the general state of cultural malaise and social ills combined to create a sense of impending doom. On top of this, the government seemed unwilling or incapable of attempting to find any new solutions to these problems. It enlisted once more the aid of propaganda, empty slogans, and rhetoric to stave off the mounting crisis.

University students in Beijing appeared to be particularly heavy casualties of the general malaise. In April, Li Shuxian, the astrophysicist Fang Lizhi’s wife and a lecturer in physics at Beijing University, commented that students had become apathetic, incapable of political activism. They consisted of two types of people: the mahjong players (mapai) and the TOEFL candidates (tuopai). Thus it came as something of a surprise to the citizens of Beijing — even those who were to participate — when the student demonstrations at the time of Hu Yaobang’s death blossomed into a popular protest movement at the end of April.

III

By making a decision to go back [to China in April] Liu Xiaobo was little better than a moth being drawn to a flame.

— Liu Binyan, June 1989

Former CCP General Secretary Hu Yaobang’s death on 15 April 1989 sparked the student protest movement. The students — many of whom had been used in the purge of Hu in 1987 — mourned the dead man as ‘the soul of China’ (Zhongguohun). The panegyrics for Hu authored by both intellectuals and students who had had little respect for him during his life disgusted Liu Xiaobao. He wrote a powerful critique of the reaction of China’s intellectual elite to Hu’s passing entitled ‘The Tragedy of a Tragic Hero’ shortly before leaving America. It provides a number of clues as to why he decided to take part in the protest movement and offers a hint of the role he envisaged for himself.

In the first place, he was dismayed by the ‘hysterical response’ to Hu’s death. Suddenly, Hu Yaobang had gained the status of a tragic hero; the mourning for him seemed to be a replay of the events of April 1976 when Zhou Enlai was the focus of popular adulation. ‘Why,’ he asks, ‘do the Chinese constantly re-enact the same tragedy (one starting with Qu Yuan’s drowning in the Miluo River)? Why do the Chinese mourn as tragic heroes people like Zhou Enlai, Peng Dehuai, and Hu Yaobang, while they forget such tragic figures as Wei Jingsheng?’

He was particularly critical of the people — both students and even Fang Lizhi who produced an enthusiastic epitaph for Hu Yaobang — who now praised Hu whereas in the past they had treated him as either a buffoon or a Party fall guy. For all of his virtues, Hu accepted his demotion with impotent grace — and was lackluster in comparison to Boris Yeltsin, the outspoken ex-mayor of Moscow. Liu argues that Hu was both the product and victim of Party authoritarianism, while Wei Jingsheng, Xu Wenli and the other victims of the 1979 purge of Democracy Wall activists were true democratic reformers. He castigates Liu Binyan, Wang Ruoshui, and Ruan Ming who by paying their condolences to Hu’s family were responding like loyal feudal ministers to the passing of their liege. ‘How many of China’s intellectuals have ever thought of asking after Wei Jingsheng’s family as he sits rotting in jail?’ While he recognizes the nature of the relationship between Hu Yaobang and China’s intellectuals he says it is time to abandon their faith in enlightened reformers within the Party elite; or at least they should support the democratic activists in China (such as Wei and Xu) and overseas (China Spring) at the same time as backing Party reformers. While not rejecting the Party outright, he was calling for independent popular political action to oppose Party fiat.

In this article Liu combines his stance on the independent intellectual with an awareness that positive group action can act as a catalyst to democratic reform within China. He had formulated general principles for democratic agitation, which he pursued throughout the movement and dismissed what he saw as the dangerous emotionalism of many intellectuals:

Rationality and order, calmness and moderation must be the rules of our struggle for democracy; hatred must be avoided at all costs. Popular resentment towards authoritarianism in China can never lead us to wisdom, only to an identical form of blind ignorance, for hatred corrupts wisdom. If our strategy in the struggle for democracy is to act like slaves rebelling against their master, assuming for ourselves a position of inequality, then we might as well give up right here and now. Yet that’s what the majority of enlightened Chinese intellectuals are doing at this moment.

This principle of rational and democratic process was something he, along with others, repeatedly tried to have implemented by the student leaders on Tiananmen Square. It was central to his ‘Six-Point Program for Democracy’ devised in the first days after the announcement of martial law, published on May 23 in the name of the Independent Student Union of Beijing Normal University as ‘Our Suggestions.’ It was seen as a central element of the next stage of the movement, both by Liu and his critics. The program called for the recognition and inclusion of the workers and peasants in a Solidarity-like campaign. It contained the central elements of Liu’s approach to the question of ‘civil consciousness’ in China. Both he and Hou Dejian, the Taiwan-born songwriter who found himself caught up in the protests in late May, were lobbying with the students to get them to hold citywide democratic elections for their organizations, thereby showing in a practical way how democracy worked and could be implemented, first among students and then in independent workers’ unions. Hou, who later said he took part in Liu’s hunger strike out of sympathy for his friend, spoke of this as being an educational process from which both the students and the electorate, as well as non- student observers, could learn a great deal. This emphasis on process became the core of the ‘Hunger Strike Proclamation’ of June 2 signed by Liu, Hou, Gao Xin, and Zhou Duo.

Back in China, Liu spent a considerable amount of time with the demonstrators. Students from his own school, Beijing Normal University, were central to the action. A welcome figure, he was known to many Beijing students for his outspokenness in public lectures. Still relatively young — he turned 34 at the end of 1989 — and a recent graduate, Liu mixed with the students easily. In this he was like Lao Mu, the poet who became head of the student propaganda department in Tiananmen, and Wang Juntao and Chen Ziming, activists in both the 1976 Tiananmen incident and the 1978-79 Democracy Wall movement, who were also in their 30s. They were unlike the majority of other ‘elite intellectuals’ (gaoji zhishifenzi) whose self-image as mentors and philosophers generally led them to remain aloof and timorous. … …

Despite his enthusiastic involvement in the protest movement, Liu, a keen observer of human frailties and foibles, maintained a sardonic view of the students. As with his literary criticism, he chose to view things differently from the general opinion, especially that of other writers and critics. He did not get caught up in the excessive rhetoric of Yan Jiaqi and the other authors of the May 17 proclamation, which was a strident denunciation of Deng Xiaoping, ‘the befuddled autocrat’ à la the Dowager Cixi. Instead, on that same day, he wrote his own appeal to overseas Chinese and concerned foreigners calling for donations to the student cause and support for the students’ demands for the government to withdraw the April 26 People’s Daily editorial and to engage in ‘open, direct, independent, and sincere dialogue’ with the students. It avoided the emotive rhetoric of other intellectuals’ public petitions (such as the May 16 and May 17 proclamations). He signed the appeal on Tiananmen Square and left his home telephone number for anyone wishing to contact him. … …

I have known Liu Xiaobo since late 1986, and we met a number of times during my stay in Beijing from May 7-27. The first occasion was on the evening of May 8 with Hou Dejian and after a long talk we all went in Hou’s red Mercedes to a small Mongolian hotpot restaurant in Hufangqiao for a late meal which continued until after 2 a.m. Again, during the hunger strike, he came to where I was staying, talked, had a wash, and asked for a change of clothing — he had been in the same clothes for five days. After martial law was declared on May 20, we met again a number of times, to talk, eat, and so that he and his friends could have a shower. … …

In private, Liu constantly bewailed the fact that the students were, as he had said elsewhere, ‘strong on sloganizing and weak on practical process.’ He found the constant power struggles and the corruption involving public donations on the Square depressing. And even at the height of his own involvement, Liu watched out for the elements of farce which he hoped to write about one day. Despite his often bemused observations of the students, the power of the hunger strike in bringing the citizens of Beijing into the streets in support of the protests signified to Liu Xiaobo an important change in the nature of political protest in China; he felt a new opportunity for civil protest was now possible and he was anxious it should not be squandered.

Fang Lizhi had talked of this earlier in the year in his essay ‘China’s Despair and China’s Hope,’ where he noted that lobby groups had begun to appear in 1988. Fang also spoke of the extremely negative public reaction to the Party’s attempt to ‘trace the rumor that top leaders and their children hold foreign bank accounts’ late in the year. People were outraged that the government wanted to penalize individuals for bringing this question to light and it was no coincidence that the slogan ‘Overthrow official speculators!’ (dadao guandao!) was the clarion call of the 1989 protest movement. There was an increased desire for the citizens to be given the right to play a supervisory role in government.

It was during the hunger strike and the early days of martial law, in which the very vocabulary of public discourse changed, that revealed this new attitude. Intellectuals, students, and cadres have always followed the Party delineation of social hierarchy and referred to the ‘comrade in the street’ as either ‘the masses’ (qunzhong) or ‘common people’ (laobaixing). Now they were spoken of as ‘the citizens’ (shimin), and their role as a positive social force — they brought life in the capital to a standstill, created the unprecedented festive atmosphere of the hunger-strike week, and then closed the city to the People’s Liberation Army for two weeks — rather than a lumpen mass requiring direction and leadership, was finally recognized. It is something that certainly caught Liu Xiaobo by surprise. ‘Our Suggestions,’ a work authored by Liu, expresses perhaps better than any other public document of the early weeks of martial law, the desire of some intellectual activists to turn the protest movement into a broadly based and organized civilian protest. Apart from calling for an end to martial law and an emergency session of the National People’s Congress, the thrust of this tract is that organized autonomous groups should be elected by various sectors of the society to represent their interests and to take part in the democratic transformation of the society at every level. The students should analyze their movement, reorganize themselves on a rational and democratic basis, and the eight impotent political parties should push for real political power. Above all, the document emphasized rationality, democratic process, and the growth of civic consciousness (gongmin yishi). Liu Xiaobo, a figure labeled in China as the evil champion of nihilism and the irrational was, ironically, now the chief advocate of positive and rational civil action. The enthusiasm he had felt as he witnessed the citizenry of Beijing take the protection of the students and the city into their own hands led him in late May to organize his own hunger strike as the student movement lost momentum and popular interest began to flag.

***

***

IV

All of China’s tragedies are authored, directed, performed, and appreciated by the Chinese themselves. There’s no need to blame anyone else.

— Liu Xiaobo, November 1988

On 2 June 1989, what was to be the last group of hunger strikes set up camp in the student tent city at the foot of the Monument to the People’s Heroes on Tiananmen Square. The group of four was led by Liu Xiaobo. The other three were Zhou Duo, formerly a lecturer in the Sociology Research Institute of Peking University, recently the head of planning for the Stone Company, Hou Dejian, and Gao Xin, former editor of the weekly newspaper of Beijing Normal University and a member of the CCP. Supposedly the first in a series of strikes by intellectuals which were to continue until the June 20 session of the National People’s Congress, it was a somewhat feeble, although courageous attempt, to maintain the rage of earlier weeks. The comic aspect of the new strike is described by Michael Fathers and Andrew Higgins, correspondents for The Independent, in the following way:

On Friday June 2, they [the students] tried to recapture past magic with a second hunger strike. History repeated itself as farce. It attracted four people, three of whom were prepared to fast for just three days. The fourth, Hou Dejian, a popular songwriter who had defected from Taiwan, said he could go hungry for no more than two days. He would be cutting a new record in Hong Kong the following week, and could not risk his health.

The quartet began melodramatically on the terrace of the Monument [to the People’s Heroes], unfurling a huge white banner bearing the words, ‘No other way.’ The political scientist, Yan Jiaqi, came to give encouragement. ‘In the circumstances, there is nothing else we can do,’ he said. Others felt differently. No crowds poured into the Square to support this strike. Even the Beijing Municipal Party Committee, not noted for its levity, thought it safe to scoff. It called the event a ‘two-bit so-called hunger strike.’

The rubric of the Beijing government was repeated in subsequent denunciations of Liu, and although the new strike had elements of farce in it, it bore the unmistakable mark of Liu Xiaobo and his perceptions of the movement. It also attracted greater attention than is credited by Fathers and Higgins.

Liu was highly critical of his fellow ‘high-level intellectuals’ as they dubbed themselves in the markedly non-egalitarian language of the Chinese hierarchy. They had, he observed, made appearances on the Square when it suited them, posing with students after marches, proffering intellectual guidance, play-acting at hunger striking themselves (but never really doing it, unlike Liu et al.), and running for cover when there was any hint of danger. Liu Xiaobo was, as ever, highly dismissive of their role in the preceding weeks. But when announcing this new hunger strike he reserved his main criticisms for the student movement. These are best summed up in the joint ‘Hunger Strike Proclamation’ signed by the four hunger strikers. After commenting on the mistakes made by the government in dealing with the student movement, they went on to analyze the shortcomings of the students:

For their part the errors of the students have been evinced in the internal chaos of their organization, the general lack of efficiency, and democratic process. For example, although their aims are democratic, the means they have employed as well as the processes they have used are undemocratic; their [political] theory is democracy, but in dealing with concrete problems, they have been undemocratic. They lack a spirit of cooperation, their power groups are mutually destructive, which has resulted in the complete collapse of a decision-making process; there is an excess of attention to privilege and a serious lack of equality, etc. Over the last 100 years, most of the struggles for democracy in which the Chinese have been engaged have never got beyond ideology and sloganizing. There’s always been a lot of talk about intellectual awakening, but no discussion of practical application; there has been a great deal of talk about ends but a neglect of means and processes. We are of the opinion that the true realization of political democracy requires the democratization of the process, means and structure [of politics]. For this reason we appeal to the Chinese to abandon the vacuous democracy of their traditional simplistic ideology, sloganizing, and end-oriented approach and engage now in the democratization of the political process itself; to turn a democracy movement which has concentrated solely on intellectual awakening into a movement of practicality, to start with small and realistic matters. We appeal to the students to engage in self-reevaluation which will take as its core the reorganization of the student body on Tiananmen Square itself.

Liu Xiaobo was one of the only advocates of a practical application of democratic principles during those final weeks. Even in the early hours of June 4, as the PLA moved on the Square in force, Liu achieved a crucial last-minute implementation of his ideas. As Richard Nations, the correspondent for The Spectator who was on the Square at that time reports, in a speech aimed at persuading the remaining students to leave the Square with the minimum of bloodshed, Liu ‘turned the question of democracy from a test of courage in some fantasy world of moral absolutes into a practical problem in the immediate present.’

The use of the expression ‘self-reevaluation’ (ziwo fanxing) in the hunger strikers’ proclamation is by no means new in mainland political rhetoric. Indeed it has been part of the currency of intellectual debate since the mid-1980s. However, in the context of this proclamation it is interesting that the call for students to review their own movement comes after an earlier and fascinating passage dealing with the question of national reevaluation, even of national repentance in the speech he made at the literary conference which demonstrators declare: ‘We are on a hunger strike! We protest! We appeal! We repent!’

They go on to say:

We search not for death, but for true life.

Under the violent military pressure of the irrational Li Peng government, Chinese intellectuals must bring an end to their millennia-old and weak-kneed tradition of only talking and never acting. We must engage in direct action to oppose martial law; through our actions we appeal for the birth of a new political culture; through our actions we repent the mistakes resulting from our long years of weakness. Every Chinese must share in the responsibility for the backwardness of the Chinese nation.

This passage echoes Liu Xiaobo’s comments to this writer in 1986. In his 1988 essay ‘On Solitude,’ he had also emphasized the need for Chinese intellectuals to ‘negate’ themselves, ‘for only in such a negation,’ he wrote, ‘will we find the key to the negation of traditional culture.’ While passing through Hong Kong in late November 1988, Liu repeated this attitude in a conversation with Jin Zhong, the editor of Emancipation Monthly. He said:

I’m quite opposed to the belief that China’s backwardness is the fault of a few egomaniac rulers. It is the doing of every Chinese. That’s because the system is the product of the people. All of China’s tragedies are authored, directed, performed, and appreciated by the Chinese themselves. There’s no need to blame anyone else. Anti-traditionalism and renewal must be undertaken by every individual, starting with themselves. I’m appalled by [philosopher] Li Zehou’s comment that we shouldn’t oppose tradition or otherwise we’ll negate ourselves. Following the fall of the Gang of Four, everyone has become a victim, or a hero who struggled against the Gang. Bullshit! What were they all doing in the Cultural Revolution? Those intellectuals produced the best big- character posters of all. Without the right environment, Mao Zedong could never have done what he did.

By producing the June proclamation and undertaking a hunger strike at a critical time in the period of martial law, which had come into force two weeks earlier, Liu and his fellows were expressing on the one hand that they had been inspired by the actions of the students over the previous weeks and at the same time wishing to engage in an activity which would somehow expiate their own sense of guilt, to free them from the very elements of the intellectual tradition to which they were heir. Of course, knowing Liu and Hou fairly well, I cannot deny that they were also motivated to some extent by personal interest — something alluded to by Chai Ling, another student leader and the rival of Wuerkaixi — a desire to be in the limelight of the movement rather than merely basking in the reflected glory of the student leaders and media stars. Nor were they the first university teachers or ‘intellectuals’ to join in the fast. Hou was, however, the only member of the Beijing glitterati I know of who took such action. Huang Beiling found a rather grand purpose in the hunger strike and concluded that: ‘Their action has become a symbol of the struggle for democracy of both Chinese intellectuals and those from the rest of the world; it washes away the record of humiliation and compromise of contemporary Chinese intellectuals.’

***

***

V

True belief is born of sincere and painful repentance.

— Liu Xiaobo

The line in the hunger strike proclamation: ‘We are on a hunger strike! We protest! We appeal! We repent!’ was written up and hung as a banner above the strikers. The last exclamation ‘We repent!’ was a conscious attempt to add a new dimension to the protest movement, and there is little doubt that Liu Xiaobo was its author.

The concepts of freedom, responsibility, and repentance form a major element of Liu Xiaobo’s writings. The importance of assuming responsibility for one’s own fate, and sharing in the responsibility for the state of both the society and the nation are among his central concerns. Equally important to his mind was the need for individuals to engage in acts of redemption so that they could affirm their own being. Both Liu and Zhu Dake, a controversial Shanghai critic and a good friend of Liu, had pinpointed the lack of God, of ultimate values, as being the tragic weakness of the Chinese tradition. ‘I believe that man is at his most sincere and transparent when he is confessing or admitting that he has sinned. Then he is most vitally alive.’ The Chinese, on the other hand, are satisfied with this shore. They find fulfillment in the corporeal; there is no need for God and therefore no need for forgiveness or redemption.’ In his major article written after Hu Yaobang’s death, Liu criticized Chinese intellectuals for their years of silence regarding the jailed democracy activists Wei Jingsheng and Xu Wenli. He also reflected on his own ignominious past:

Chinese intellectuals have hoped for too much from the government during the past dozen or so years of reform. They have too readily ignored the push for democracy among the people. The cool indifference of everyone in China to Wei Jingsheng’s sentencing in 1979 is proof of that attitude. (Here I include myself, for at the time I was just another one of the ignorant mob).

He characterized the petitions of January-March 1989 with the following words:

What is most required of Chinese intellectuals, in particular enlightened intellectuals, now is neither to mourn Hu Yaobang nor eulogize him, but rather to face up to the figures of the imprisoned Wei Jingsheng and Xu Wenli and to engage in a collective act of repentance. The petition movement, rather than being seen as an heroic undertaking, would best be understood as the first step towards such repentance.

What was important was the desire to confess, to find redemption in acts that would negate the disinterested and lethargic attitude to the past, and through that action to find self-fulfillment. Liu had been critical of the ‘Confucian personality,’ the Kongyan renge [孔顏人格], promoted by such contemporary philosophers as Li Zehou, and was equally dismissive of meaningless self-sacrifice such as that made by the Tang poet Sikong Tu, who starved himself to death out of loyalty to his lord. Equally, he felt that calls by Chinese intellectuals over the years to achieve freedom always had a plaintive tone about them. Like Fang Lizhi, he emphasized that freedom was a natural right and not something to be bestowed by the powerful. ‘For so many years now,’ he wrote, ‘the Chinese have been on their knees [before an emperor] begging for freedom.’ He was thus highly critical of the students who had petitioned Premier Li Peng on April 22, the day of the state memorial service for Hu Yaobang, by kneeling on the steps of the Great Hall of the People. It was an example of what he had called ‘the Chinese form of death — blind suicide.’ However, he saw the mid-May hunger strike of the students as denoting a departure from the mere moral dimension of pressuring the government, and not merely as a throwback to the traditional ‘petitioning the throne through death’ (sijian). Rather it was a form of personal action undertaken for the sake of social advancement and for the development of China’s civil society. This is why he decided to emulate the strike in early June, hoping to encourage more intellectuals to pressure people into realizing their role and rights as citizens.

Liu Xiaobo’s call for reflection and confession in the June 2 proclamation is not the only example of self-examination that appeared during the student movement. As early as late April a number of confessional-style writings had appeared in Beijing, for example, ‘Confessions of a Vile Soul — by a Reborn Ugly Chinaman,’ a pamphlet of Beijing Normal University dated late April, and ‘The Confession of a Young Teacher — by a young teacher who knows shame.’ The authors of both of these essays admit to fear and opportunism at the time of the publication of the April 26 People’s Daily editorial which called for the suppression of the student protests. The first of these was written as a pointed riposte to the Taiwan writer Bo Yang’s controversial speech ‘The Ugly Chinaman,’ which had been widely reprinted in China in 1986. Liu’s fellow hunger striker Hou Dejian also countered Bo Yang’s thesis in a song written on Tiananmen Square shortly before the massacre entitled ‘The Beautiful Chinese.’ The song contains such lines as ‘Ugly Chinamen/How beautiful are we today,’ and ‘Everything can be changed/It is all up to us/Nothing is too distant/ Stand up and see/Everything is before us now.’

Liu was far from being the first mainland writer to talk about the need for repentance or confession in the post-Mao era. The veteran writer Ba Jin has made repentance a central theme of Random Thoughts, the collective name for his five volumes of essays/memoirs, and a number of other writers have touched on the need to repent for the dark days of the Cultural Revolution. The establishment literary critic Liu Zaifu, Liu Xiaobo’s early nemesis and a comrade of Li Zehou, featured the question of repentance in the speech he made at the literary conference which catapulted Liu Xiaobo to fame in 1986. In his speech, Liu Zaifu made a lengthy analysis of post-1976 literature. Commenting on its limitations, he called for ‘national repentance’ in regard to the past.

Culturalistic self-reflection is, in the main, an autopsy of the body of the nation. It is a self- examination of the structure of the mass cultural psychology. The enhancing of this kind of self- examination requires the active participation of each and every individual in the nation, and from that participation as soon as each individual undergoes an awakening of self-awareness they will recognize their personal responsibility, they will develop a desire for self-critical reflection, that is, they will [wish to] partake in national confession and joint concern…

However, Liu Zaifu was true to his reformist credo and he points to the positive, social function of confession. Redemption is not part of a personal quest, but rather a prerequisite for the new and correct political and social orientation of the individual:

We engage in self-examination so as to be able to adjust ourselves more readily to modernization, and so we are all the more equipped to participate in it. It is not to be a form of abject self-negation, but rather a positive act whereby we will find value in the lessons of history and be all the more clear-headed as we stride towards the future. The path of self-reflection and criticism is that of self-love and self-strengthening; it is the path of positive change and advancement. Our motherland is at a turning point in history; it wants to free itself of poverty and advance to strength and greatness. Writers who deeply love their country will use their powerful skills to mobilize and encourage our people to join in the struggle, to advance, to create, to offer the light and warmth of their lives to the present great age. Our writers will bring to completion this glorious social task.

I have commented elsewhere on Liu Zaifu’s statement in relation to the Chinese Velvet Prison. It is this last statement in particular which is at glaring variance with Liu Xiaobo’s view of the confessional. Liu Xiaobo was not interested in using confession to purge himself of the guilt of being a witness of the Cultural Revolution; nor did he wish to engage in a redemptive action merely to align himself better with the forces of reform.

VI

A [destructive] kalpa destiny is now at work, which is called forth by the crimes committed by the tyrannical rulers, and also by the karmic activities of the people developed from immeasurable cycles of transmigration. When I take a look at China, I know that a great disaster is at hand.

— Tan Sitong, 1897

The unique thing about man is that he is capable of being aware of his tragic fate; he can be aware of the fact that he will die; he can be aware that the ultimate meaning of the universe and life itself is unknowable. A nation that is without an awareness of tragedy and death is to some extent a nation that is still in the mists of primal ignorance.

— Liu Xiaobo

Liu Xiaobo’s call for personal confession and repentance repeats attempts at ‘self- renewal’ made by Chinese intellectuals since the end of the Qing dynasty. An important element of this is the concept of redemptive thought or action as mentioned in the above.

When he wrote in the June 2 proclamation of the hunger strikers, ‘Every Chinese must share in the responsibility for the backwardness of the Chinese nation,’ Liu Xiaobo was acknowledging the role of the individual in the state of Chinese affairs. It is a central theme also in his essay ‘On the Doorstep of Hell.’ This is an awareness familiar to Western writers, and one that does not, in fact, mark such a radical departure from the Chinese intellectual tradition of the late 19th and 20th century, as we can see from Tan Sitong’s writings at the end of the Qing dynasty. It may be relevant here to quote a few statements made by Huang Yuansheng, an intriguing early Republican writer and the author of a series of confessional writings which in spirit are not unrelated to what Liu Xiaobo has said on the subject.

Huang Yuansheng (zi Yuanyong, 1883?-1915) was the author of a fascinating essay entitled ‘Confessions’ (Chanhuilu) published shortly before his death on Christmas Day, 1915. Born in Jiujiang, Jiangxi, into a scholar’s family, Huang was the youngest jinshi in the last round of imperial exams of the Guangxu reign. He was 21. He immediately went to Japan to study and returned to China shortly after the 1911 Revolution to become a journalist. After a short career as a reporter, one which earned him the reputation as ‘a genius of journalism,’ he was pressured by President Yuan Shikai, the presumptive emperor, into writing in favor of the new monarchy. After much hesitation, Huang wrote a non-committal piece on the subject. He was directed to make it more to Yuan’s liking and instead fled to Shanghai from Beijing to go into hiding. Shortly after this incident he wrote his ‘Confessions.’

After being forced to write his ‘unlettered essay’ on Yuan Shikai he said, ‘I have been fortunate enough to escape from all of that and am determined to concentrate all of my energies on being a responsible person (yiyi zuoren) and use my utmost efforts to confess the guilt/crimes of my life in the capital.’ He also said, ‘In a few months I plan to travel around America in an attempt to regain something of the sense of human worth that I have lost.’ He says that everything he has written concerning politics and the national character was no more than a parroting of the opinions of other literati, and that all of it was ‘material for a confession.’ He went on to say:

All of this is because I had no clear understanding of things; I was not adept in self-cultivation and self-reflection; I lightly gave myself over to the discussion of matters of great import and thought myself to be a superior man of the times. [Faced with] the collapse of the country and the crimes [that have been committed] against the people, I must say that I am in part to blame. In the future, I pledge to exert myself in seeking out knowledge, to become independent and a man of stature.

In ‘Confessions,’ Huang states that his experience in Beijing under Yuan Shikai, and indeed the years leading up to it, had created in him a feeling of ‘schizophrenia.’ He feels as though his soul (hun) is dead while his body (xing) lives on. Huang Yuansheng is also a member of that transitional generation caught between the old and the new; a man who is willing to apportion blame for his dilemma between both society, or history, and himself. Yet, even in his grim despair, he holds to a very positivistic philosophy, one that he announces in no uncertain terms at the end of his confession:

I am of the opinion that the most essential thing is for every aspect [of the society] to undergo reform (gaige). Now, to reform the state it is necessary to reform the society, and to do that it is necessary to reform the individual, for the society is the basis of the state, and the individual the foundation of the society. I have no desire to question the state, or society, nor, in fact, other people. But I must first question myself, for if I am incapable of being a man what right do I have to criticize others, let alone the society and the state?89

And it is here that we find a fascinating insight into the makeup of a 20th-century Chinese literatus-intellectual. This is a new being, one conditioned by the Confucian tradition of state service and involvement so succinctly stated in the Great Learning. He wants to reform himself but thinks very much along the lines of the traditional literatus: The change is for the sake of the society and the country, even if the reform is completely different in content from the past, the structure of tradition remains. The above quotation from Huang Yuansheng is also relevant in our review of Liu Xiaobo’s involvement in the 1989 protest movement. Liu was highly critical of the self-dissipating aspect of the student movements since 1979, declaring, ‘I see the shadow of China’s numerous peasant rebellions in the hot-headed enthusiasm of these movements.’ Like Huang Yuansheng, Liu Xiaobo was aware of the need for action not only in the public forum but in one’s own life; and like Huang he views the hierarchy of self-reform very much in a Confucian order.

At the same time as staging mass political demonstrations within the wider political sphere, people have to engage in detailed, down-to-earth, and constructive actions in the immediate environment. For example, democratization can start within a student group, an independent student organization, a non-official publication, or even the family. We can also carry out studies of the non-democratic way we live in China, or consciously attempt to put democratic ideals into practice in our own personal relationships (between teachers and students, fathers and sons, husbands and wives, and between friends).

VII

Prior to this [the 1989 protest movement] the students of Peking University had become extremely degenerate; and the moral standards of the people of Beijing had reached an unprecedented low. The awareness of this all-embracing crisis among people fired a desire for self-destruction. Upon receiving the order to evacuate [Tiananmen] some people slit their wrists with broken glass. For them life was now meaningless; they had no confidence in the nation at all.

— Duoduo, June 1989

The concept of ‘awakening,’ xing or juexing, one common in the writings of Chinese reformers and revolutionaries from the turn of the century, was also a feature of the 1989 protest movement. The movement excited people previously caught in the nihilistic vortex of 1988. Liu Xiaobo expressed the desire for people to participate in protest as part of a civil action of redemption; many people felt that they were being roused by the students’ spirit of daring from a long period of social and political apathy.

Banners with the single character ‘xing’ writ large on them were prominent. In the streets during the hunger–strike week people excitedly declared that ‘the Chinese have woken up’; it was seen as a self-awakening as opposed to the organized standing up of the Chinese people declared by Mao Tse-tung from the rostrum of Tiananmen in 1949. When people began to realize that this epiphany with Chinese characteristics was doomed to failure and even to be crushed, many participants in the protests became suicidal. The mood of elation turned for some to one of extreme pessimism; having been awakened and redeemed through participation in the movement the sense of loss and hopelessness was now far stronger than it had been in 1988 or early 1989 when the capital was suffused with a fin-de-siècle ambience. Now the atmosphere was apocalyptic.

Blood and sacrifice were symbols throughout the protest movement. Even in its earliest phase, when writers and intellectuals petitioned the government to release China’s political prisoners in February, the poet Bei Dao, one of the organizers of the letter of 33 intellectuals, said he had written a will. Wills were also written by students on the eve of the April 27 march in defiance of the People’s Daily editorial of the previous day, which had condemned the student demonstrations as ‘turmoil’ instigated by a small number of plotters. But it was not until the hunger strike of May 13-19 that the specter of death and martyrdom loomed high over Tiananmen Square. The strikers’ declarations bespoke death with lines like: ‘We use the strength of death to fight for life,’ and ‘Death awaits the broadest and eternal echo.’ Although they claimed that they were too young to wish for death, the symbols of the protest became increasingly sanguine.

Some of the strikers even wrote their oaths in blood, recalling unintentionally the way Chinese Buddhist monks once copied sutras in blood when pledges were made. And it was not long before signs and shirts with gruesome blood markings appeared. For some of the strikers refusing food was not enough. Twelve of them, after toying with the idea of self-immolation, decided to foreswear water as well. This group of students from the Central Drama Academy were separated from the others and isolated in a bus parked at the northern entrance of the Great Hall of the People. A cordon was put up around the area like a giant mandala and supporters circumambulated it often in tearful silence. It was a tragically effective way to elicit an outraged response from the people of the city. The bus had the number of hours during which the students had gone without food and water written up on it. The lighting towers on either side of the Square were occupied by students who hung red-spattered banners with the word ‘Sacrifice’ (canlie) on them. Others wore T-shirts patterned with red, possibly blood, and although the mudra of the movement was the ‘V’ for victory sign, the red and white headbands worn by the students bespoke rather of a suicidal kamikaze spirit. Indeed, there was something about these young people who had pledged themselves to death for the sake of a cause that now had as much to do with honor and self-esteem as anything; it was reminiscent of that ‘splendid death’ (rippa na shi) pursued by the Japanese shimpū pilots. At other times the rhetoric had an unmistakable Chinese resonance. At one point during the hunger strike I saw a group of either workers or local residents circumambulating the strikers’ enclosure carrying a large banner on which was written the legend ‘Neither bullets nor swords can harm us’ (daoqiang buru), chilling bravado straight from the Boxer Rebellion of 1900. It was people who expressed such sentiments who presumably went on to form the ‘dare to die squads’ (gansidui).

Sacrifice for the cause, while having a venerable tradition in China, has also been a central feature of Chinese communist education. The role models for Chinese youth were for decades the selfless martyrs Wang Jie, Ouyang Hai and even the red samaritan Lei Feng (who died in far from heroic circumstances: He was felled by a wayward telegraph pole). The sentiments behind the Party slogan, ‘Fear neither hardship nor death’ (yi bupa ku, er bupa si), launched on the nation with the PLA campaign to learn from Wang Jie — a soldier in 1965 who had selflessly sacrificed himself for the safety of his comrades by jumping on a rogue bundle of explosives — were drummed into children in 1969. Twenty years later those children would form the main body of activists in the 1989 protest movement. On October 1, fearful of terrorist retribution for the massacre, the authorities ordered the handpicked revelers who were permitted to dance in Tiananmen Square to emulate Wang Jie. They were instructed to hurl themselves on any explosive device found during the celebrations and make a sacrifice for the nation. … …

***

Source:

- Geremie Barmé, Confession, Redemption, and Death: Liu Xiaobo and the Protest Movement of 1989, in George Hicks, ed., The Broken Mirror: China After Tiananmen, Harlow, Essex: Longman Current Affairs, 1990, pp.52-99, 1990 (full text with notes). For a Chinese translation, see: 石默奇译, 忏悔、救赎与死亡:刘晓波与八九民运。

Liu Xiaobo in China Heritage:

- The Inspiration of New York, 31 December 2021

- ‘The Specter of Mao Zedong’, in Prelude to a Restoration: Xi Jinping, Deng Xiaoping, Chen Yun & the Spectre of Mao Zedong, 20 September 2021

- Yesterday’s Stray Dog 喪家狗, Today’s Guard Dog 看門狗, 4 January 2019

- Bellicose and Thuggish — China Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow, 24 January 2019

- My Puppy’s Death, 2 February 2019

- Mourning, 30 June 2017

***

Urumqi East Road

— a blank-page revolutionary song

白紙革命歌曲《烏魯木齊東》

(an imitation-homage to ‘Queen’s Road East’ by Lo Tayu 羅大佑《皇后大道東》)