Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium, a Tally

單

The threnody of the Xi Jinping decade is tedium, something born of the ceaseless oscillations within China’s hermetically sealed system and it signals its deadening presence through reversals and the glum repetition of various tropes of the past. In this era, what was formerly limited divergence has given way to convergence, difference to singularity, diversity to homogeneity. Where in the past there was wriggle room, a straitjacket now awaits; possibility is all too frequently replaced by ordained inevitability; contingency by certainty and the unpredictable is met with inflexibility and harshness. For those who have lived with China’s party-state over the decades the déja-vu quality of the Xi era is undeniable. It is an age that sets itself against the unpredictable, the contingent, against the disheveled nature of reality itself; as a result it is implausible, brittle and in constant crisis-mode.

This is Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium.

***

單 dān, single, a unit of measurement, alone, unique, particular, is the thematic rubric of this tally, a summary of the tedium generated by the Xi Jinping era. 單 dān also occurs in such compound words as 單一 dān yī, singular, unvaried, limited, and 單調 dān diào, monotonous, and in such phrases as 單調乏味 dān diào fá wèi, boring, 單調無味 dān diào wú wèi, tasteless and 單調枯燥 dān diào kū zào, deadly dull.

The character 單 dān also appears in the term 清單 qīng dān, inventory, list, or account. The expression 拉清單 lā qīng dān means to settle accounts, to take someone to task, or to get even. Like many boys of his generation, Xi Jinping possibly learned the expression 拉清單 lā qīng dān by watching Zhang Ga, Boy Soldier 小兵張嘎, a popular anti-Japanese war film released in 1963. At the time, Young Xi was a lad of ten. It was the same year that the Party accused his father, Xi Zhongxun 習仲勳, of being the head of an anti-Party clique and sent him into exile.

Xi Jinping quoted Zhang Ga when addressing malfeasant Party cadres in early 2014. He warned then: ‘Don’t think you can enjoy yourself with impunity, be careful because sooner or later your number will come up’ 別看今天鬧得歡,小心日後拉清單。Ever since, his opponents have used the same expression to say that, sooner or later, Xi too will be held to account for what he has wrought.

— Geremie R. Barmé, Editor, China Heritage

Distinguished Fellow, The Asia Society

18 February 2022

A Piper Who Would Call the Tune

‘A ledger is being tallied up for all who err. Everything is recorded in it. The moment one of these malefactors falls foul of our system, the debts will be called in. You might think you can get away with it all but, watch out: eventually your number too will come up. That’s the simple truth. So just don’t do the wrong thing. There’s always a higher power looking over your shoulder; you’d better regard it with due awe and respect.’

實際上那些錯誤執行者,他也是有一本賬的,這個賬是記在那兒的。一旦他出事了,這個賬全給你拉出來了。別看你今天鬧得歡,小心今後拉清單,這都得應驗的。不要幹這種事情。頭上三尺有神明,一定要有敬畏之心。

— Xi Jinping, speaking at a central work meeting on politics and law, January 2014

習近平, 中央政法工作會議, 2014年1月

***

‘You might think you can get away with it all but,

watch out: eventually your number too will come up.’

別看今天鬧得歡,

小心日後拉清單。

Xi Jinping’s warning has been widely mocked for years. People who have been outraged by the policies of a man who has systematically reversed decades of reform believe that, sooner or later, Xi himself will have to answer a charge sheet of his own.

Leaning In to Xi Jinping, or

Gleichschaltung with Chinese Characteristics

Gleichschaltung: ‘the act, process, or policy of achieving rigid and total coordination and uniformity (as in politics, culture, communication) by forcibly repressing or eliminating independence and freedom of thought, action, or expression; forced reduction to a common level; forced standardization or assimilation.’

One of the truly significant achievements of the Deng-Jiang-Hu era was the Communist Party’s strategic, albeit limited, retreat from China itself. Gradually, and often with great reluctance, the Communists curtailed the chokehold over every aspect of Chinese life that they had pursued with unwavering devotion from the early 1950s. Unfolding in tandem with the de-Maoification of the late 1970s and early 1980s, the ‘re-civilising’ of the country was still a drawn-out and uneven process. The limited liberties increasingly enjoyed by society were just as much a result of the individual and collective struggle of people from all walks of life over decades as they were the product of the Party’s generally self-serving reformist agenda. The multifaceted civil advances were also contested by Party stalwarts who were ever fearful that the social and economic forces unleashed by the reforms would eventually threaten their political, economic and social domination of China.

‘Sprouts of civil society’ were constantly being stamped out although, in the new millennium, some Party figures, technocrats and social thinkers supported a kind of soft transition towards creating a system that better reflected the social and economic diversity of the nation. Leaders like Xi Jinping regarded this as anathema and, from the moment he took the helm of China’s party-state-army in late 2012, he methodically and ruthlessly undermined and in many cases reversed the civilian gains of the previous three decades. As we argue here and elsewhere, although the makings of Xi Jinping’s empire of tedium were in evidence throughout the three-decade rule of his predecessors, they were constantly debated and contested. During his decade-long rule, however, Xi has in many cases foreclosed possibility. As we noted both in You Should Look Back and Requiem for an Autocrat, Xi Jinping has cast China back into the vicious cycle of the past.

***

Following Xi Jinping’s accession in November 2012, people of a certain generation — that is, just about anyone over the age of fifty — including those with a lifelong involvement with the Chinese world, could soon tell that recidivism was in the air.

Bombast about ‘The China Dream’, which featured in Xi’s inaugural speech as General Party Secretary, was immediately followed by a collective visit by the new Politburo Standing Committee to the National History Museum on Tiananmen Square. They were there to see the ‘Road to Revival’ 復興之路, a large-scale propaganda exhibition that offered a heavily curated and wildly distorted account of modern and contemporary Chinese history.

Peppering his remarks at the museum with quotations from Mao’s poems, Xi lectured his comrades on the Party’s ordained view of the past, its evaluation of the present and its forecast for the future. A little over a week later, in December 2012, Xi undertook a Tour of the South in which he visited cities in the south of the country in emulation of Deng Xiaoping’s 1992 Tour of the South two decades earlier. Deng’s tour was aimed at reinvigorating economic policies that had languished in the wake of 4 June 1989. It would gradually become clear that Xi’s 2012 tour of inspection was aimed at reinvigorating older priorities albeit in the guise of a new direction.

By late 2013, those who were alert to the rhymes of modern Chinese history had a clear sense of where things were going. Over the preceding twelve months for all intents and purposes, Xi Jinping had for carried out a ‘coup by stealth’; in the process of which he effectively subordinated to himself control of the machinery of the party-state. The ‘cultural logic’ of sixty years of Party rule suggested that Xi’s makeover of the system might possibly continue unhindered for years to come.

That awareness, along with a rising sense of dream, was accompanied by a more pervasive mood, that of ennui. In the second five years of the Xi Jinping decade, Chinese critics were more vocal.

In ‘An Objective Evaluation of Xi Jinping’ Fang Zhou declared:

‘… Well may Xi Jinping inwardly regard himself as the greatest ruler in all of Chinese history but, sooner or later, he will learn that this is a chimera. The yawning chasm between Xi’s hubristic self-belief and reality is his Achilles heel.

‘Xi Jinping may well end up as a lonely figure; his comeuppance is unavoidable. People will not keep investing in unrealistic fantasies that they know can only lead to disaster. Even his supporters will gradually distance themselves from him and, when everyone has finally moved on, he will be left on his throne all by himself. Then he will gasp the last breath of his political life.’

— from Fang Zhou, ‘Xi Jinping’s Denouement’, trans. G.R. Barmé

We have repeatedly made the case that Xi is a logical extension of the Chinese Communist Party’s determination to cleave to its ideological traditions and structures of power. It has, at great cost and with immense effort kept contending political, economic and social forces at bay. By foreclosing the future, Xi Jinping has, as we have noted elsewhere, and writers as diverse as Xu Zhangrun and Fang Zhou have noted, trapped China in a new vicious cycle of suffocating repetition. This phenomenon is by no means unique to China, since revisionism, the unresolved legacies of the past and historical repetitions bedevil many countries. In the case of the People’s Republic of China, however, there are no countervailing forces allowing for debate or an open-ended possibility of change. As a result, a sense of tedium is born not only of the repetitious nature of much that has been happening, but a wide-spread awareness that what has been undone during the Xi Jinping decade will, at some point in the future, itself have to undone.

In recent years, the work of Hannah Arendt has found a receptive audience in China and her famous tag line, ‘the banality of evil’, in Chinese 平庸之惡, is quoted by writers, online activists and critics to describe everything from local bureaucrats to major political scandals. The banality that we attempt to plot in Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium is not the result of casual thoughtlessness, a lack of self-reflection or callous indifference. As we argued in our series on Homo Xinesis — the Xi-era New Socialist Person — Chinese tedium, as distinct from that in, say Australia, North America, Europe and Russia — is the result of a concerted, guided and premeditated multi-generational effort. Chinese history under the Communist Party did not necessarily have to end this way, but it was predisposed to travel in this direction from the start of the reform and opening up era in 1978 (for more on this, see Prelude to a Restoration: Xi Jinping, Deng Xiaoping, Chen Yun & the Spectre of Mao Zedong, China Heritage, 20 September 2021).

In my introduction to Shades of Mao (1995), a study of the populist Mao cult of the early 1990s, I quoted an observation that the Marquis de Custine made about the Russian autocracy:

‘Sovereigns and subjects become intoxicated together at the cup of tyranny …. Tyranny is the handiwork of nations, not the masterpiece of a single man.’

Here I would also draw on Alexandr Solzhenitsyn who wrote in The Gulag Archipelago:

‘If only it were all so simple! If only there were evil people somewhere insidiously committing evil deeds, and it were necessary only to separate them from the rest of us and destroy them. But the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being. And who is willing to destroy a piece of his own heart?

‘During the life of any heart this line keeps changing place; sometimes it is squeezed one way by exuberant evil and sometimes it shifts to allow enough space for good to flourish. One and the same human being is, at various ages, under various circumstances, a totally different human being. At times he is close to being a devil, at times to sainthood. But his name doesn’t change, and to that name we ascribe the whole lot, good and evil.’

This then is the banality of the Xi Jinping era. It is easy to dismiss the sense of tedium and ennui created by encountering time and again the tired repetition of ideas, the vacuous slogans, the commonplace nostrums which Xi and his cohort flood the nation. That is added to by the humdrum and deadening effect resulting from the skein of policies in every area of China’s political and social life that are pursued as part of Xi’s aim to reduce the inherent contradictions and complexity of a vibrant modern society to a scale that can be managed and directed by one man. Just as significant is the participation of the multitude in the process. Willingly or not, hundreds of millions of people are intoxicated together at this cup of tyranny.

In our account of the climate of tedium that suffuses the Xi Jinping era, we risk being banal ourselves. However, as Simon Leys observed in an essay on human rights abuses in China published over forty years ago:

‘I do not apologize for being utterly banal; there are circumstances in which banality becomes the last refuge of decency and sanity.’

***

This October 2020 comic monologue by Yu Qian (于謙, 1969-), a celebrated ‘cross-talk’ performer with Deyunshe 德雲社 in Tianjin, builds up momentum to make the claim that the Empress Dowager Cixi’s obsession with Pekingese dogs resulted in her support for the Boxer Rebellion in 1900. This, in turn, hastened the decline and eventual collapse of the Qing dynasty. The tongue-in-cheek title of the performance, ‘A Dog was the Architect of Acceleration’ — possibly the invention of one of Yu Qian’s smart-arsed younger colleagues, was subsequently changed so as to avoid political repercussions.

***

U-Turn

By the end of Xi Jinping’s quinquennial in 2017, the earlier sense of ennui had devolved into a pervasive sentiment of tedium, monotony, banality and boredom. As we noted in the introduction to this series, You Should Look Back, independent Chinese commentators were increasingly alarmed that the country was speeding forward, but in the wrong direction 加速開倒車. Substantive issues presumably resolved from the 1980s — the dangers of one-man rule and personality cults; strict term limits for political leaders; the succession crises that had bedeviled the Communists for decades; the separation of Party and State; the evolution of the rule of law and lawyers; the growth of a semi-independent media and publishing industry; academic freedom; a corralled civil society and a popular awareness of personal rights; the de-politicisation of the everyday; the reining in of militancy and extremist rhetoric; the demonisation of ethnic minorities and vulnerable groups; the gradual embrace of basic values and rights, along with many other things — were not, in fact, resolved. Rather, they unravelled, data points in an accrescent portfolio of backsliding.

Even as the ‘tedious ten years’ of Xi Jinping unfolded, however, China’s evolution and development continued. Xi Jinping’s idealised vision for the nation combined the strengths of total party domination with the possibilities of invention and reform. As policy refinements and retractions threatened many of the gains of earlier years, long-term problems were confronted with a new urgency. These included the environment and emissions; income disparities and the redistribution of wealth; the reigning in of the tech sector; infrastructure; social welfare; legal reform; gender issues; education and numerous other areas of public policy. In each of these, retreats were accompanied by advances. The not-inconsiderable achievements of the Xi decade are the result of the efforts and genius of multitudes as well as the managerial abilities of a competent technocracy along with the dedication of academic specialists, journalists and the purchasing power of China’s insatiable consumers. Xi’s tenure as Chairman of Everything, Everyone and Everywhere readily brings to mind the words of the grand inquisitor O’Brien in George Orwell’s novel 1984:

‘But always – do not forget this, Winston – always there will be the intoxication of power, constantly increasing and constantly growing subtler. Always, at every moment, there will be the thrill of victory, the sensation of trampling on an enemy who is helpless. If you want a picture of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face – for ever.’

Under Pax Xinensis it is likely that the boot of power will be AI-designed footwear crafted from high-end materials and labour-farm leather. These luxury items will be promoted both by Chinese and fellow-traveller influencers and available for online purchase as well as international delivery.

‘Click like and subscribe.’

***

In his day, Deng Xiaoping was hailed as the ‘Grand Engineer of Reform’ 改革開放和現代化建設總設計師, Xi Jinping, however, China’s ‘Architect of Acceleration’ 總加速師, the man whose policies had dramatically reversed the trajectory of the nation and a leader whose ambitions could well precipitate systemic failure, if not collapse. For his supporters, however, Xi was hastening the country’s historic march towards regional power, global standing and unprecedented achievement.

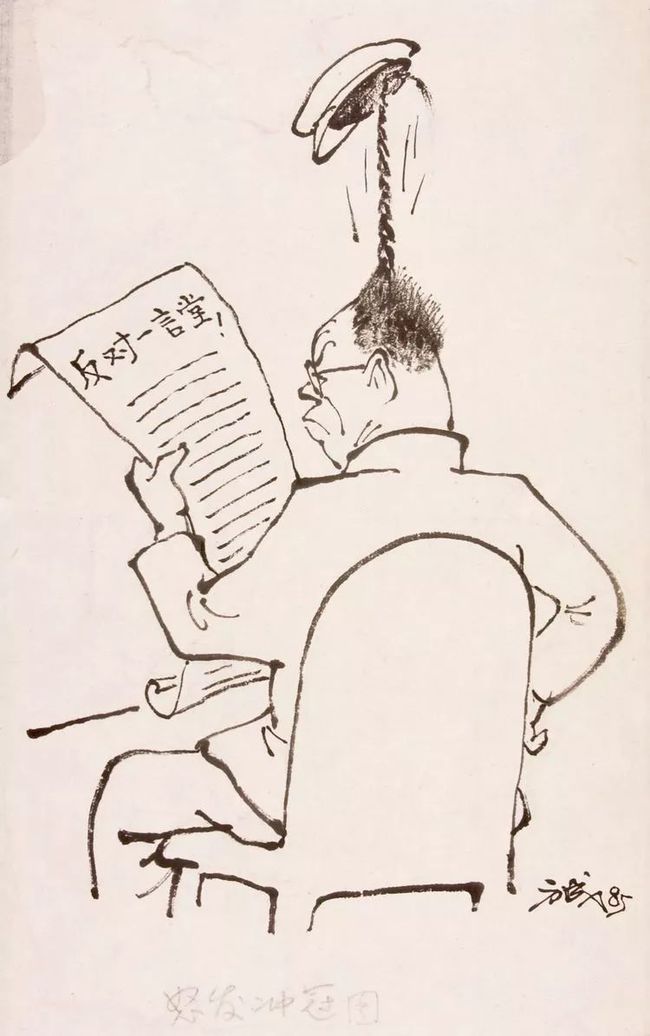

The re-emergence of strong-man politics has revived an appreciation of ‘autocrat studies’ world wide. In the case of China, people now readily refer not only to such writers as George Orwell, but also to the rich library of Chinese literature produced over the last century, from Huang Yuansheng’s critique of Yuan Shikai in the 1910s (which led to Huang’s assassination in San Francisco) and the writings of Lu Xun and others in the 1920s and 30s through to Bo Yang on ‘the ugly Chinaman’ and Lung-kee Sun’s study of the ‘deep structure’ of Chinese culture in the 1980s, Liu Xiaobo and Yu Jie in the 1990s, as well as Wu Zhiyong and his (now-banned) book Giant Baby Nation 巨嬰國 in the present-day. This library built up over a hundred years describes a patriarchal state swathed in progressive garb while blathering about Confucian pieties. At every level of government, business and society superiors subject their subordinates to control and condescension and the population at large is infantalised by policies of stupefaction 愚民政策. The Leader is, in effect, the only fully realised adult and as the nation’s pater familias his thoughts invariably precede and pre-empt any that anyone else may have at any time.

At decade’s end, regardless of all of the state-sponsored bombast about The China Story, the all-pervasive mood and political ambience of the People’s Republic of China and its global presence have produced what we call Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium. It is a tedium bred of the fact that many of the Xi-era reversals will, over time, themselves be reversed. The grand rescission could be piecemeal and gradual or it may be violent, chaotic and blood-drenched. Our sense of tedium is tainted by the mood of profound trepidation expressed widely in China both in private as well as publicly by a few brave individuals, including Xu Zhangrun, Guo Yuhua, Xu Zhiyong and Ren Zhiqiang, and even the otherwise reticent Lao Dongyan.

***

In 2018 we commemorated the fact that it was four decades since the play ‘Where Silence Reigns’ 於無聲處 was first performed in Beijing. It was a momentous time in China’s modern history: Mao was dead, his radical revolutionary supporters had been arrested or sidelined, essential reforms of education and science were unfolding, men and women who had for decades been jailed, exiled or who were still living in the shadows were being exonerated, and the long-stagnant intellectual and cultural life of the country were going through something of a ‘Beijing Spring’.

The Party, the leaders of which were mired in the blood and violence of their misrule, was desperate to regain a measure of legitimacy and to do so quickly. It rejected two decades of a destructive policy that favoured pitiless class struggle and universal ideological repression, and turned its focus to rebuilding a crippled economy and improving the livelihoods of a people it had cruelly betrayed.

In July 2018, forty years after ‘Where Silence Reigns’ caused a sensation, Xu Zhangrun, then a professor of law at Tsinghua University, broke the silence that has spread under the draconian rule of Xi Jinping, the supreme party-state-army leader of the People’s Republic. In an eloquent and withering essay he expressed his concerns about the state of Chinese politics and anxiety about the country’s future (see Imminent Fears, Immediate Hopes — a Beijing Jeremiad 我們當下的恐懼與期待).

As the first decade of Xi Jinping’s rule draws to a close, Xu Zhangrun’s hopes remain unrealised while his fears were, in anything, understated.

***