Drop Your Pants!

The Party Wants to

Patriotise You All Over Again

(Part III)

This is the third installment in Drop Your Pants!, our overview of the Patriotic Education Campaign launched by China’s Communist Party on the last day of July 2018, and the latest in our series of Lessons in New Sinology. Here we offer an introduction to Homo Xinensis, the comrade-consumer of Xi Jinping’s vaunted New Epoch 新時代, in contrast to the now all-but-overwritten New Era 新時期 of Deng Xiaoping et al. Homo Xinensis Ascendant, the fourth part in this series discusses the constitution of the New Person 新人, and what they are expected to achieve. The concluding essay, Homo Xinensis Militant suggests how traditions of warfare and the militancy commingle to create China’s warrior ethos.

This is not a sociological study — there are aspirational graduate scholars and tenured academics aplenty who are jostling to offer their insights on the basis of field work and state-of-the-field scientific scholarship. Rather, as in the other essays in ‘Drop Your Pants!’ we provide an overview of the lineage of the new Xi-men and Xi-women of China, noting how mental and physical hygiene have been melded in China’s political enterprise to achieve modernity under the rule of the one-party state, aspects of its overall ‘political ecology’ 政治生態.

Below we will evoke imagined traditions, as well as trace aspects of century-old attempts to ‘reform the Chinese national character’ 改造國民性, in particular in the face of home-grown racism as well as in a global environment of imperialist racial thinking. As in previous Lessons, we will also refer to the Yan’an era of the Chinese Communist Party, one that remains the wellspring for many political practices in the People’s Republic today. Yan’an featured prominently in our first Lesson in New Sinology (see Mendacious, Hyperbolic & Fatuous — an ill wind from People’s Daily, China Heritage, 10 July 2018). In the process, we will take a sideways glance at the experience of the Soviet Union. Much work is being done by writers on the consumers of the People’s Republic and how the credo of ‘I Shop Therefore I Am’ (pace Barbara Kruger) has been generating branded identities for the past thirty years. In this preliminary study of Homo Xinensis we concentrate instead on Official China and its avowed aspirations for its subjects. Unofficial China — the boisterous, vibrant and variegated world that is a different, and more enjoyable, kind of lived Chinese reality — will be discussed another time.

***

‘Drop Your Pants! The Party Wants to Patriotise You All Over Again’ is a five-part introduction to the Patriotic Education Campaign launched by Party Central on the last day of July 2018 that is written in our in-house style of New Sinology 後漢學. It consists of:

- Part I — Ruling The Rivers & Mountains — reviewed the Thought Reform Movement of the early 1950s, which included the Party’s inaugural patriotic re-education putsch, and noted its connection to the Yan’an Rectification Movement of 1942-1943, which we discussed in Mendacious, Hyperbolic & Fatuous. We believe that a basic familiarity with those earlier movements is helpful in understanding not only the 2018 Patriotic Offensive, but also the Communist Party’s ‘correctional re-education’ 矯正教育 policies in Xinjiang and Tibet;

- Part II — The Party Empire — below, provides a short account of how, under various regimes and leaders, party and state have been melded and promoted in twentieth-century and early twenty-first century China. This contentious history is useful in appreciating that country’s politicised patriotism;

- Part III — Homo Xinensis — the present essay, considers the history of the comrade-but-not-citizen and the hyper-patriots imbued with Core Socialist Values that are nurtured and encouraged by the party-state under Xi Jinping;

- Part IV — Homo Xinensis Ascendant — outlines the desiderata for Homo Xinensis today, and for the future. By way of contrast we also quote from Alexander Zinoviev’s Homo Sovieticus, the Doppelgänger of the New Person of Xi Jinping’s New Epoch; and,

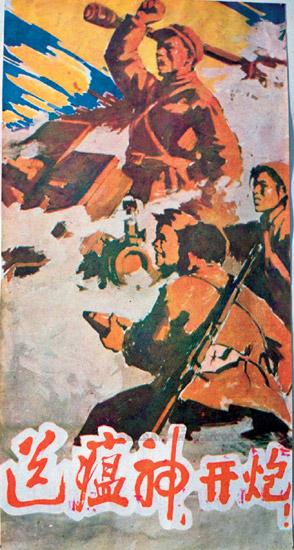

- Part V — Homo Xinensis Militant — the final essay in the ‘Drop Your Pants!’ series of Lessons in New Sinology discusses Red DNA 紅色基因, Peaceful DNA 和平基因 and how traditions of warfare and the lyrical militancy of revolution commingle to create a romanticised warrior ethos.

This series takes up some of the themes in the 24 July 2018 appeal to the Chinese Communist Party and government by Professor Xu Zhangrun 許章潤, Imminent Fears, Immediate Hopes — a Beijing Jeremiad 我們當下的恐懼與期待 (China Heritage, 1 August 2018).

The present essay should be read in conjunction with:

- Lee Yee 李怡, What’s New About Such Thinking? — The Best China, II, China Heritage, 5 November 2017;

- Lee Yee 李怡, Who’s on First — China’s Successive Failures (The Best China, IV), China Heritage, 20 November 2017; and,

- The Editor and Lee Yee 李怡, Deathwatch for a Chairman, China Heritage, 17 July 2018

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

31 August 2018

Back at the Beginning

Some Prefatory Remarks

In this the third part of ‘Drop Your Pants!’, a series of essays on Patriotic Education in the People’s Republic of China today, we return to the questions that first confronted academics and thinkers in the early 1950s.

At the height of the Beijing summer in mid 1951, Liu Shaoqi, the Communist Party leader who was a close collaborator in the formulation of the theories that the Party Chairman Mao Zedong used to forge ideological unity during the Yan’an Rectification Campaign of 1942-1943, commissioned Hu Qiaomu 胡喬木 to write a history of the Chinese Communist Party as a guide for the country that it now dominated.

Official anecdote holds that over seven days Hu — the man who we will recall had first called on Yan’an cadres to ‘drop their pants, cut off their tails and take a wash’ — drafted Thirty Years of the Chinese Communist Party 中國共產黨的三十年 while sitting in a bathtub to keep cool. (Hu’s draft was extensively revised by Liu Shaoqi and others. At the same time a plan was made for Hu’s fellow ideologue Deng Liqun 鄧力群 to draft an updated version of Liu’s crucially important 1939 speech The Cultivated Communist 論共產黨員的修養. This will be the subject of another Lesson in New Sinology).

On 29 September 1951, Zhou Enlai, the recently appointed premier and foreign minister of the People’s Republic, addressed academics and administrators from Peking University and other tertiary institutions on the question of the need for China’s intelligentsia to subject itself to Thought Re-moulding. In his speech, Zhou used Hu Qiaomu’s text as a key reference. Zhou’s speech would inaugurate the process of ‘Washing in Public’ 洗澡 that we discussed in Ruling The Rivers & Mountains, part one of ‘Drop Your Pants!’

Simon Leys once described Zhou, whom he met as part of a Belgian student delegation in 1955, as a man with ‘a talent for telling blatant lies with angelic suavity’. During the 1940s, he was the public face of the Communist Party’s United Front strategy. An apparatchik extraordinaire Zhou had a history of bloody betrayal and brilliant survival; he was also the Party’s human face when it came to dealing with the country’s educated men and women. Drawing on thirty years of suborning his will to the needs of the Party, in his September 1951 speech Zhou told the country’s intellectuals how they could remould their thinking. It was a life-long process, he said, one that began by differentiating between friends 朋友 and enemies 敵人. Those who had been studying the Chairman’s works would have recognised the famous opening lines of Mao’s December 1925 Analysis of Classes in Chinese Society:

Who are our enemies? Who are our friends? This is a question of the first importance for the revolution. The basic reason why all previous revolutionary struggles in China achieved so little was their failure to unite with real friends in order to attack real enemies. 誰是我們的敵人?誰是我們的朋友?這個問題是革命的首要問題。中國過去一切革命鬥爭成效甚少,其基本原因就是因為不能團結真正的朋友,以攻擊真正的敵人。

Zhou went on to say that distinguishing friend from enemy involved, in the first instance, an adjustment of one’s political stance 立場 and social attitudes 態度 to make them accord with the policies of the party-state. Naïve patriotic sentiment must be transmogrified into support for the People and unity with the Proletariat, of which the Communist Party was the enlightened vanguard, as well as being the instrument of History. Thought Reform would be experienced as a rebirth 脱胎换骨, something akin to ‘washing the heart and a stripping skin off the face’ 洗心革面. The process would allow the country’s wayward intellectuals to achieve renewal by correcting the errors of their ways 改過自新.

In response to Zhou’s seemingly heartfelt speech, a group of academic leaders who were already carefully studying Party dogma in an effort to adjust to the new regime, now petitioned the government to re-educate them en masse. Starting with Peking University and Tsinghua University a movement to ‘Wash in Public’ would be launched. Over the following months, it involved every academic, university administrator, publisher and teacher in the country. It was a lengthy, painful and, for some, deadly experience. The essential repertoire of that movement, described briefly in Ruling The Rivers & Mountains, would be refined and applied time and again during the political movements that have been a feature of life in the People’s Republic.

We should recall that the 1951 Thought Remoulding-Patriotic Education movement was launched at a time of relative national elation: years of war had come to an end; the economy was stable; and there was a government of unity. What urban dwellers generally did not realise was that the nationwide rural reform that was taking place involved pitiless class struggle and mass murder. Few people outside the Party itself appreciated what had happened during the Rectification and subsequent Salvation movements in Yan’an from 1942 to 1944: how merciless, bloody and murderous they had been. In fact, the details would only come to light with the work of Gao Hua 高華 many decades later. They understood the patriotic agenda the Communists proclaimed for China well enough, but they did not appreciate the radical plans that the Party had in store.

In essence, people were required to confess to their ‘two-faced’ nature and to commit to transforming themselves as they forge a unity with the party-state and its ever-changing demands. In the case of the 1951-1952 campaign, academics were required to admit to and then disavow their allegiance to the old order, to academic independence, to free thought, to the Nationalist government’s education system, to the pro-American and Western orientation of teaching, research and publishing in China over the previous half a century. They were to denounce their innate slavishness to Western imperialism, its ideas and its values. Through acts of public confession, criticisms by their colleagues and by means of an ideological rebirth after making a pledge of fealty to the Communist Party they would renounce a two-faced stance that had previously let them get away with pretend patriotism despite the fact that they clung to the spiritual coat-tails of the West.

The Party’s attacks on ‘two-faced people’ 兩面派/ 兩面人 would continue, and unswerving loyalty to the Party, regardless of how contradictory or absurd its policy twists and turns might be, would remain as the cornerstone of repeated patriotic reeducation campaigns. The level of alarm was raised in 1959 when the United States announced its policy to undermine socialist countries in the Soviet Bloc by means of Peaceful Evolution 和平演變, that is the promotion of Western ideas, cultural forms, democratic ideals and through support for dissidents. The spectre of Peaceful Evolution haunts Xi Jinping’s government still and it responded from 2015 with a range of bans in universities on teaching and even reading about certain corrosive Western ideas (for more on this, see the Chronology below).

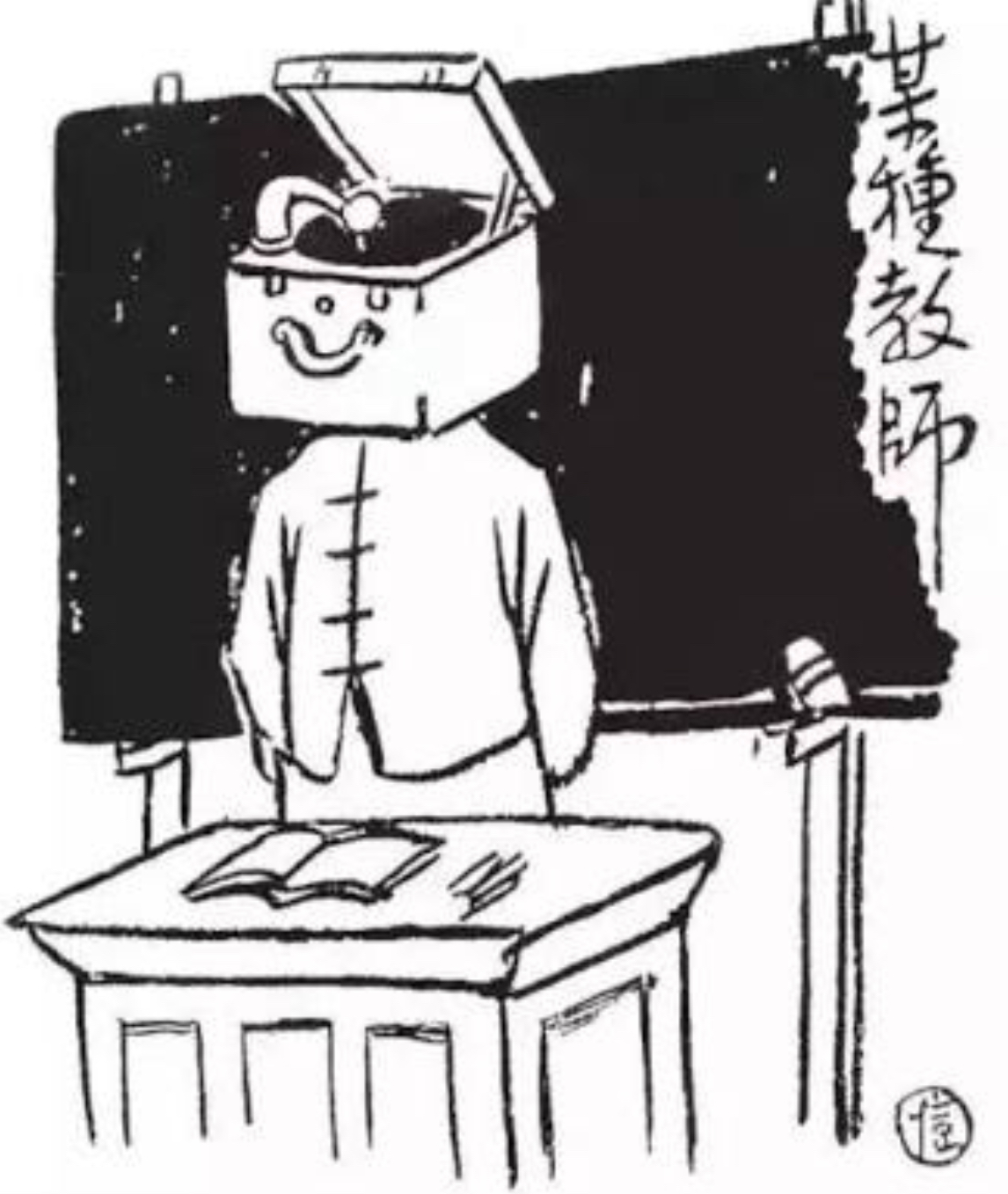

It was also Party loyalty that underpinned the early 1960s demand that academics, scientists and professionals of all kinds be ‘Red & Expert’ 又紅又專, that is, first and foremost they must study and internalise the Party ideology to become ‘Red’, while constantly striving to excel in their particular fields of knowledge, that is to be ‘Expert’. The concept of ‘Red & Expert’ also features in the 2018 ‘Offensive to Promote the Spirit of Patriotic Struggle [that requires intellectuals to] Contribute Positively to Building the Enterprise in the New Epoch [of the Party-State and China]’ 弘揚愛國奮鬥精神、建功立業新時代活動, the subject of our series ‘Drop Your Pants!’

In recent years, brain-washing through gruelling re-education has also been a central aspect of life in the prison-gompa (lamaseries) of Tibet and the internment camps of Xinjiang. Before we discuss the evolution of Homo Xinensis we will re-visit Peking University, the place where it all began in 1951.

— The Editor

Two Universities 梁效

On 4 May 2014 — the ninety-fifth anniversary of the May Fourth demonstrations of 1919 — Chairman Xi Jinping visited Peking University (北京大學, PKU). The Chinese Communist Party claims that the patriotic student demonstrations that marked May Fourth 1919 are their unique heritage and, although the events of that period contributed to the founding of the Party in 1921 (as well as to the revolutionary aspirations of the Nationalist Party 國民黨), they predated it. In 2014, the place called Peking University was also vastly different from the old Republican-era college famed for intellectual independence. That Peking University was situated in the centre of the city. For the student demonstrators of 1919 it was only a short march to Tiananmen.

In May 2014, Xi Jinping’s PKU itinerary included a meeting with an aged scholar by the name of Tang Yijie (湯一介, 1927-2014). Media reports gushed about the intimate exchange between Party boss and a scholar renowned for his work on an official ‘Confucian Canon’ 儒藏. The project had been inaugurated in 2003 with a state grant of 1.5 billion RMB. With an end date in 2025 it aimed to assemble a vast corpus of works related to Confucianism in imitation of the pre-Communist scriptural canons of Taoism 道藏 and Buddhism 大藏经. In June 2010, Peking University had also established a Confucian Academy 北京大學儒學研究院 with Tang as its inaugural director.

Tang Yijie was a model academic for the unfolding Xi Epoch. He was the embodiment of academic achievement, in-depth research into State Confucianism (something that Liu Shaoqi had featured in his 1937 speech The Cultivated Communist) and unwavering loyalty to the Party. For aficionados of Chinese cultural politics, the encounter between Xi Jinping and Tang, who died only a few months later, was heavy in irony. Sixty five years earlier, Tang had joined the Communist Party shortly after it set up an open Party committee at the university. That same year his father, the noted philosopher Tang Yongtong (湯用彤, 1893-1964), who had been acting president of PKU following the flight to Taiwan of its formal head, the famed liberal intellectual Hu Shi (胡適, 1891-1962), joined that appeal by a group of leading academic administrators to Mao and Zhou requesting the re-education of the university’s faculty mentioned above. Up until that point, Tang Yongtong had been a respected historian known, along with Wu Mi 吳宓 and Chen Yinque 陳寅恪 as one of the Three Outstanding (Chinese graduated) Talents of Harvard University 哈佛三傑.

In 1954, following a veritable storm of other ideological campaigns and political purges, Hu Shi was made the object of a devastating nationwide attack, one that again started at Peking University. This time the denunciations, criticisms and confessions were aimed at ridding China of the influence of this cultural giant and May Fourth hero once and for all. Devastated by the scale and fury of the vitriol aimed in absentia at his old friend Tang Yongtong suffered a stroke. He never fully recovered. In his last years, his son, a young philosophy student and devoted Party member by the name of Tang Yijie, cared for the ailing scholar while acting as his amanuensis and occasional ghost writer.

***

I encountered Tang Yijie at PKU shortly after Mao’s death. He was in political purdah for his role in the Mao-Gang of Four writing group known as Liang Xiao 梁效, a homonym for Liangxiao 兩校, or ‘the two schools’, that is Peking and Tsinghua universities. Formed in late 1973 and led by the Party Secretaries of the two universities and representatives of Unit 8341, Mao’s personal pretorian guard, the Liang Xiao writing collective involved dozens of academics who undertook research and writing projects aimed at adding a scholastic veneer to the Party’s factional infighting. As a Party loyalist, Tang had no choice but to follow orders. During its three-year collective career, Liao Xiao published some two hundred pseudo-academic essays in major Party newspapers and journals that were tailored to the dizzying dialectical shifts of the day. Liang Xiao’s work was deemed to be of such intellectual heft and political value that it was required reading at universities throughout the country. I read Liang Xiao as a student in my late-Maoist university days, and would soon hear about Tang Yijie and his colleagues by reputation.

A few titles from Liang Xiao’s oeuvre reflect the style and content of their tortuous polemics: ‘The Truth about Kong Qiu [the vulgar name for Confucius]’ 孔丘其人, ‘Research on the Historical Experience of the Confucian-Legalist Two-line Struggle’ 研究儒法鬥爭的歷史經驗, ‘Wu Zetian: a political talent’ 有作為的女政治家武則天, ‘The Direction of the Revolution in Education Must Not be Corrupted’ 教育革命的方向不容篡改, ‘Repulse the Rightist Tendency to Overturn Correct Verdicts’ 回擊右傾翻案風 and ‘A Critique of Deng Xiaoping’s Compradore Capitalist Economic Thinking’ 評鄧小平的買辦資產階級經濟思想.

***

After a face-saving period of criticism, reflection and self-renewal required following the death of Mao and the purge of the Gang of Four in late 1976, many writers involved in Liang Xiao would achieve fame and respectability. Tang Yijie was one of their number. By the time the refashioned Confucian luminary met Xi Jinping in May 2014 he was what is known in the trade as a ‘Practiced Political Athlete’ 老運動員, a term that is a play on the words ‘political purge’ 運動 and ‘athlete’ 運動員.

Although from the 1980s Tang became an acknowledged expert in Confucianism, he was hardly a dàrú 大儒, or Great Scholar of Principle, of the kind praised by the Tsinghua University professor of law Xu Zhangrun 許章潤. For Xu the term rú 儒, often clumsily translated as ‘Confucian’, means ‘a man whose learning and actions are grounded in Confucian principles of righteousness, fearlessness and probity’ (for more on this and Xu Zhangrun, see Imminent Fears, Immediate Hopes — A Beijing Jeremiad, China Heritage, 1 August 2018). In contrast, ‘New Confucian Academics’ 新儒家學者 are little better than intellectual merchants.

By the time Xi Jinping met him in May 2014, Tang Yijie would have been aware of the deadening restrictions on academic freedom of a kind that was reminiscent of the late-Cultural Revolution era when Liang Xiao had been active. Tang’s wife, the internationally noted comparative literature expert Yue Daiyun (樂黛雲, 1931-), would also appreciate what the new clampdown meant. Protected by fame and advanced age — other cases have shown that the Party apparat shies away from the overt persecution of its celebrated members — they nonetheless chose silence. It is for this reason that in China Heritage we commemorate the clear-thinking and plain-speaking of outstanding members of their generation like Wu Zuguang 吳祖光 and Yang Xianyi 楊憲益, as well as paying homage to the bravery of younger scholars like Liu Xiaobo 劉曉波, while noting the valour of active academics like Xu Zhangrun and the agonies of writers like Xu Zhiyuan 許知遠. There are those who could speak out in defense of independent thought and academic freedom, things that were crucial to them as they have built up their own reputations. They choose to do otherwise. Having long ago disavowed the political caprice and cruelty of the Maoist era, now that Xi Jinping’s New Epoch ushers in a Silent China, it is noteworthy that many who could well voice their opposition with little fear of retribution take the well-trodden path of complicity.

In many ways, Tang Yijie was a New Socialist Person; he was both Red and Expert; he had done the Party’s bidding, often to his own detriment, since joining its ranks in 1949. Homo Xinensis, the New Person of the Xi Jinping Epoch inherits the genes of the New Socialist Person, as well as the DNA of its noteworthy subspecies, Homosos, the subject of the following essay and ‘Homo Xinensis Ascendant’.

Tang Yijie passed away peacefully on 9 September 2014, thirty years to the day after Mao’s demise in 1976, and a little over four months after he met Chairman Xi.

New Socialist Man

March 2018 marked the fifty-fifth anniversary of Mao Zedong’s exhortation to the people of China to ‘Learn from Comrade Lei Feng’ 向雷鋒同志學習. In 1963, the People’s Liberation Army martyr Lei Feng 雷锋 (born in 1940, he was felled by a telephone pole on 15 August 1962) was praised for his intense study of Mao Zedong Thought, his heightened ideological acuity and his selfless devotion to others. As Yang Huang 楊煌, head of the political commentary department of the Party theory journal Seeking Truth 求是雜誌, put it in a commemorative essay reprinted in People’s Daily, Lei Feng remained in 2018 ‘the benchmark for New Socialist Man’ 社會主義新人的標桿. (See 杨煌, 培育一代代社會主義新人, People’s Daily, 7 March 2018)

Like so other many aspects of the Chinese Communist Party, that of the New Socialist Man or person was a Sinified version of the New Soviet Man or New Soviet Person новый советский человек that originated in the Soviet Union. Socialist revolution ushered in the next stage in the evolution of homo sapiens and the New Person would be the product of the socio-economic transformation of society led by the vanguard of the proletariat, the Communist Party. The New Person (in both Soviet and Chinese propaganda the ideal models were nearly always men, except when Jiang Qing, Mao’s wife, was in charge of culture from 1966 to 1976) would be selfless, miraculously productive, devoted to the collective and protecting public property as well as being morally outstanding and an ethical model for others.

The model New Socialist Man in the Soviet Union was the miner Aleksei Grigorievich Stakhanov (1906-1977) who, it was claimed, on 31 August 1935 dug up 102 tons of coal in less than six hours (fourteen times his quota). Stakhanov’s example was used to inspire others and soon the Soviet media claimed that the ‘Stakhanovite Movement’ had increased industrial production by forty-one percent.

Yang Huang’s March 2018 People’s Daily commemoration of Lei Feng also quoted Mao Zedong’s early vision for the youth of China. In October 1937, Mao described the type of person the Communist Party needed to fill its ranks. In an inscription written for the recently founded North Shaanxi Public School 陝北公學 on the occasion of the first anniversary of the death of the writer Lu Xun, the Party Chairman outlined his hopes for the school, and for the progressive youth of China both during the ongoing war with Japan and for the future:

We must create a vast body of people, a revolutionary vanguard with political vision. They will be energised by a spirit of struggle and sacrifice. They will be open and loyal, enthusiastic and upright. They will not pursue personal profit and instead devote themselves to the liberation of the Chinese Race and society. They will be fearless in the face of difficulties, unwavering as they courageously advance ever forward. These people will not be wildly arrogant, nor will they seek public prominence; they will be practical and grounded. With such a vanguard China’s revolution cannot but be successful. 要造就一大批人,這些人是革命的先鋒隊。這些人具有政治遠見。這些人充滿著鬥爭精神和犧牲精神。這些人是胸懷坦白的,忠誠的,積極的,與正直的。這些人不謀私利,唯一的為著民族和社會的解放。這些人不怕困難,在困難面前總是堅定的,勇敢向前的。這些人不是狂妄分子,也不是風頭主義者,而是腳踏實地富於實際精神的人們。中國要有一大群這樣的先鋒分子,中國革命的任務就能夠順利的解決。

For the Chinese Communists in Yan’an the Soviet model would be fused with elements of Confucian-Mencian tradition to create one of the most abiding aspects of Party propaganda and education: the Exemplary Figure 模範. Carefully selected ‘models’ 榜樣 were promoted as being ‘typical figures’ 典型人物 that represented an ideal and evolving form of Party-loving, Patriotic, Hard-working and Ethically Superior person. Their achievements would be used ad nauseam to educate and inspire others. During the war various Heroic Models were promoted (including Zhang Side 張思德, Liu Hulan 劉胡蘭 and Dong Cunrui 董存瑞). After 1949, every sector of society was expected to produce its own Exemplary Figures from which the Party chose national Heroes like Lei Feng.

In 1980, as the Communist Party turned its focus to economic policy and rebuilding a country ravaged by decades of failed policies, Deng Xiaoping declared that in this New Era 新時期 of reform the Party needed its own kind of New Person. Post-Mao education would not only focus on basic learning, he declared, it would continue to emphasise Party ethics, morals and ideas. In May of that year, Deng called on the nation’s educators to train ‘Four Haves New People‘ 四有新人, that is, young people who would ‘aspire to have Ideals, Morals, Culture and Discipline’, their mission being to contribute to the People, the Fatherland and Humanity 立志做有理想、有道德、有文化、有紀律的人,立志為人民作貢獻,為祖國作貢獻,為人類作貢獻.

***

The Chairman’s Tears

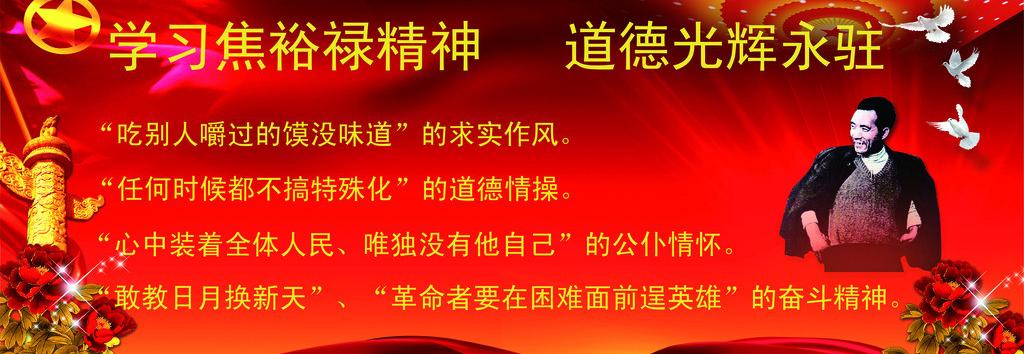

In 2015 the Communist Party media reported that Xi Jinping had twice shed tears for another Party martyr, Jiao Yulu (焦裕禄, 1922-1964), the model party boss of Lankao county in Henan province who was made into a paragon on the eve of the Cultural Revolution.

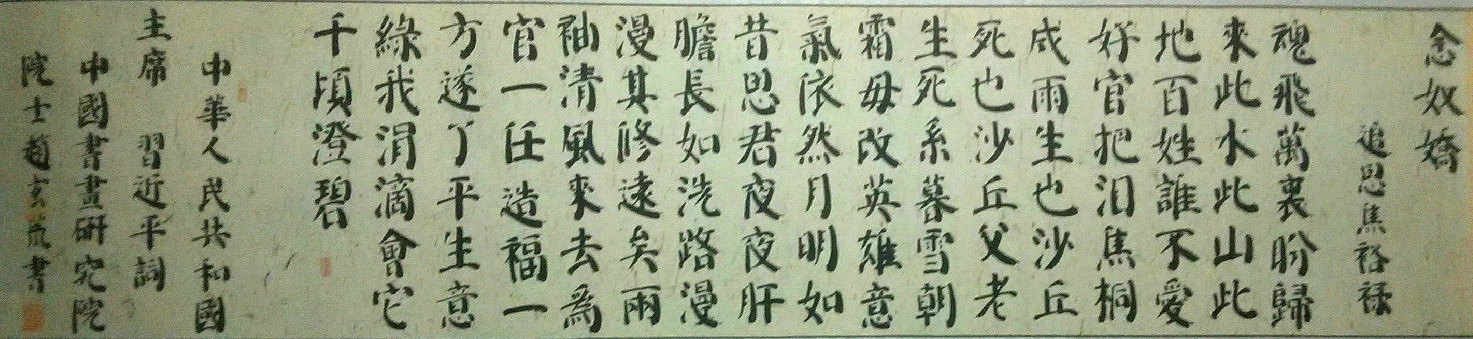

The first time that Xi cried for Jiao was on 6 February 1966 when, as a high-school student in Beijing, he read about how Jiao Yulu had sacrificed himself for the cause. The second time was on 9 July 1990 when Xi, by then Party Secretary of Fuzhou in Fujian province, read an article in People’s Daily titled ‘The People Yearn for Jiao Yulu’ 人民呼唤焦裕禄. The lead writer of the 1966 report on Jiao was the veteran Yan’an-trained journalist, Mu Qing (穆青, 1921-2003), later the head of Xinhua News Agency. That lengthy work of reportage was titled ‘A Model County Party Secretary — Jiao Yulu’ 縣委書記的榜樣——焦裕祿. Xi was so moved by the second report on Jiao, one that also involved Mu Qing, that he composed a poem in the hallowed style of the traditional song-lyric 詞:

Jiao Yulu: In Memoriam

— to the tune of Niannu Jiao

念奴娇 • 追思焦裕禄

In the depths of night I read

‘The People Yearn for Jiao Yulu’

The sky clear, the moon a silver orb,

my thoughts take flight…

His soul has travelled yon

We long for its return

To these waters, these hills.

The People treasure good officials.

I shed tears to water Jiao’s paulownia[1]

He truly lived in the Sand Dunes

Forever he now lies in the Dunes

At one with the lives of his people.[2]

Evening snows, morning frosts

His Heroic Will undeterred!

This same bright moon does shine

And I think of you at night

Your sincerity eternal.

Long is the way, progress hard

Advance we must with purity of purpose.

Wherever we are appointed

We must bring prosperity,

Unchanging purpose in life.

Drop by drop, the water of devotion

Irrigates vast fields of green.

中夜,讀《人民呼喚焦裕祿》一文,是時霽月如銀,

文思縈系……

魂飛萬里,

盼歸來,

此水此山此地。

百姓誰不愛好官?

把淚焦桐成雨。

生也沙丘,

死也沙丘,

父老生死系。

暮雪朝霜,

毋改英雄意氣!

依然月明如昔,

思君夜夜,

肝膽長如洗。

路漫漫其修遠矣,

兩袖清風來去。

為官一任,

造福一方,

遂了平生意。

綠我涓滴,

會它千頃澄碧。

— 15 July 1990

- Jiao encouraged the planting of paulownia to prevent soil erosion.

- On his deathbed, Jiao requested that he be buried in the sand dunes of Lankao.

The translator Arthur Waley famously observed of Mao Zedong’s poetry, which was foisted on the country from the time the poem ‘Snow — to the tune of Qinchun Yuan‘ appeared in 1945 until his death in 1976, was ‘not as bad as Hitler’s painting, but not as good as Churchill’s’. Laden with commonplace literary references the poem attributed to Xi Jinping conveys uplifting, albeit pedestrian, Party sentiments. For the time being, published examples of Xi Jinping’s literary oeuvre remain modest, although perhaps other hidden gems will be released in the future.

Although over the decades Jiao Yulu has repeatedly featured in the life of China’s propaganda-state, and has moved Xi Jinping to tears on two occasions, for our discussion of Homo Xinensis, his appearance in 1990 is of particular significance.

***

In the immediate aftermath of the Beijing Massacre of protesters in June 1989, the Party declared that there was an urgent need for ‘state-of-the-nation’ education 國情教育 in schools at all levels so as to remould the thinking of young people who had been unduly influenced by Western thinking and arrant Chinese celebrity intellectuals (the campaign also led to the rise of ‘state-of-the-nation’ experts like Hu Angang 胡鞍鋼, but that is a subject for another time). In 1994, this post-4 June initiative would be institutionalised as a Patriotic Education Activity 愛國主義教育活動. Apart from a broad-based education in the Party’s version of history, society, culture, politics and so on, ‘state-of-the-nation’ education promoted historical heroes, moral exemplars and Party martyrs who were supposed to inspire the country’s youth.

Lei Feng, mentioned above, was duly trotted out to re-educate and inspire the recalcitrant youth and ill-behaved citizens. Above all, the party’s revolutionary successors were exhorted to learn from what was praised as Lei Feng’s ‘screw spirit’ 螺絲釘精神, immortalised in a famous quotation from the peasant-soldier: ‘I’ll be a bolt in whatever part of the machinery of state the party wants to screw me.’ But having been promoted too many times to have much impact the ‘Learn from Comrade Lei Feng’ campaign soon wore thin. In early 1990, Party propagandists turned instead to Jiao Yulu.

While Lei Feng’s exemplary acts enjoined the whole society to be selfless and live in an austere fashion, Jiao Yulu was an embodiment of Communist values that Party cadres, already awash in the world of economic reform and corruption, were supposed to emulate. Jiao’s image was also aimed at reconciling the masses with the Party by convincing them that there are — or at least were — good and incorruptible cadres.

As part of the campaign to promote the ideal selfless cadre, a biopic based on Jiao’s last years was released in February 1991. Jiao Yulu related how, in December 1962, at the height of the ‘three years of natural disasters’ (the official code expression for mass famine and economic dislocation caused by the Party’s ill-conceived policies during the Great Leap Forward of the late 1950s), Jiao was sent as the new party secretary to Lankao county in Henan 河南省蘭考縣. Jiao worked tirelessly to improve agricultural productivity, reclaim land by encouraging the planting of paulownia trees and prevent the local population from abandoning their homes to go begging for food elsewhere. Eventually, Jiao falls ill due to over work and is hospitalised with cancer, an illness to which he eventually succumbs.

Jiao’s moral probity and self-righteousness apparently appealed to audiences throughout the country (or at least to those who organised corvée audiences to attend screenings), and the film was a marked box-office success. Jiao’s charismatic appeal was based on his extravagantly self-sacrificing attitude of a man who found personal fulfillment (and moral uplift) in constantly giving to others in a spirit of abnegation. Generally, the quasi-religious flagellations of such figures appeal strongly to the abiding idealism and moral perfectionism of contemporary Chinese official culture, itself recast from the cloth of late-dynastic Confucianism.

Moral absolutism has remained a powerful and constant force in Chinese life, one that has been repeatedly reinforced by Party propaganda, and just as constantly challenged by popular yearning for both homegrown and imported religious belief. Although the gap between the Party’s moralistic propaganda (official rhetoric) and its often mendacious practice results in general disaffection from political leaders, it has not necessarily undermined the power of Party symbolism. Furthermore, there is no clear line of demarcation between the mass culture suffused with ideological traits that serve narrow-minded and authoritarian rule and more traditional and staid forms of propaganda. In the early 199os, many viewers could find succour and edification in films like Jiao Yulu while rejecting crude propagandistic overtures made to them in the form of ideological campaigns, study sessions, or droning exhortations to toe the official line.

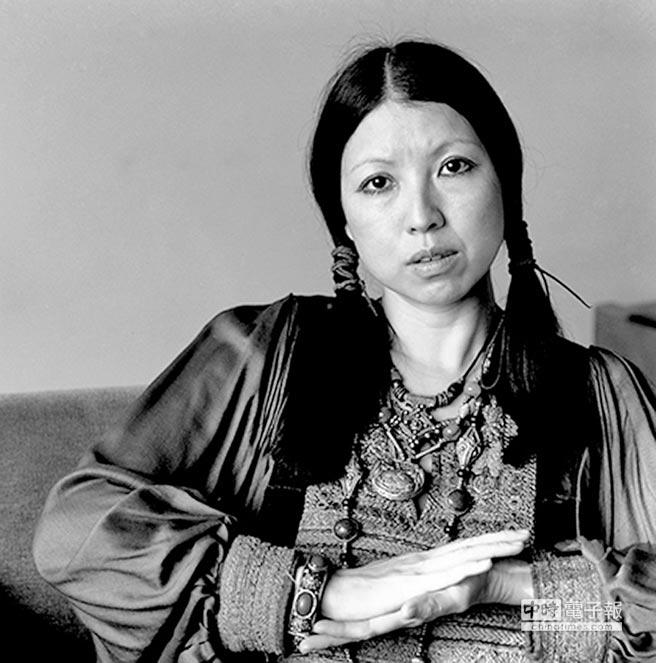

During 1991, the contrast between social reality (or mass psychology) and Party propaganda was brought into stark relief during a debate involving Jiao Yulu conducted in the pages of the Beijing Youth News, a popular paper run by Beijing Municipal Party Youth League. Starting in early April 1991, the paper ran a series of articles on the issue of self-sacrifice that revolved around two juxtaposed quotations. The first was about the cadre-martyr Jiao Yulu, the second a line from the popular Taiwan writer and celebrity San Mao (三毛, originally 陳懋平 later 陳平, 1943-1991), who had committed suicide in Taipei on 4 January 1991.

The headline in Beijing Youth News ran: ‘Two Famous Lines, One About Jiao Yulu and the Other from San Mao — Which Would You Choose?’. The quotations were:

In his heart he had a place for all the People, but no room for himself. (Jiao Yulu)

If you give everything to others, you will discover you’ve spent your life abusing one person: yourself. (San Mao)

San Mao grew up in Taiwan and studied in Spain and at the Goethe Institute. After a checkered career working and teaching in America, the Canary Islands and Spain, she married a Spaniard and went to live with him in the Sahara for two years. After her husband’s death in 1979, San Mao returned to Taiwan, although she continued to travel widely and wrote prodigious amounts of mellifluous prose as well as a number of hit songs. In 1986, she was named one of Taiwan’s ten best-selling authors. Popular in Hong Kong and Taiwan from the mid-1970s as a materialistic, modern-day romantic, San Mao’s influence belatedly spread to mainland China in the late 1980s. Her self-absorbed image and cutesy, egotistical prose appealed strongly to the adolescent-at-heart readers of the Mainland, who were enjoying the kind of consumer revolution that had made San Mao so popular in Hong Kong and Taiwan more than a decade earlier. Her suicide in a Taipei hospital sent shock waves throughout the Chinese cultural world.

The aim of the Beijing Youth News discussion was to contrast the selfless community spirit of the Party hero who died for the People with the self-interested egotism of a bourgeois writer who killed herself for no socially significant reason. Not surprisingly, throughout its reports on the popular responses to this orchestrated ‘debate’, Beijing Youth News gave greater weight to student and reader opinions that favored Jiao Yulu’s Party Spirit. Many of the published letters extolled Jiao’s admirable personality and deeds; they generally observed that his spirit of sacrifice was even more relevant to the China of the 1990s when the profit motive and consumerism had become the chief motivating forces in everyday life. Not all the praise was, however, unqualified and one anonymous respondent spoke with the candor usually reserved for private conversations: ‘Jiao Yulu really was a good man, but he’s not a suitable role model for my generation: he made life such a chore.’

Another comment that the paper’s editors claimed ‘reflected the opinion of a considerable number of middle-school students’ was: ‘Nowadays, everyone — from the state to the individual — talks about pragmatism. It’s the most basic and natural thing. First and foremost, you have to look out for yourself; only then can you think about helping other people.’ Another student speaking at a seminar organised by a middle school to discuss the two quotations said that once he had a job and a settled family life, he would be delighted to help others just as Jiao Yulu did. This was the same student who had interrupted the discussion to suggest they break up early so they would not miss the early evening screening of the cartoon series Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles on TV. The report published on this student seminar concluded: ‘The education that middle-school students get today might allow them to appreciate and support Jiao Yulu; the realities of life, however, force them to make other personal choices.’

Over the following weeks, the paper continued to publish selected readers’ responses to the question ‘Which would you choose?’ Analysing the hundreds of letters that were received (few of which were presumably fit to print) Zhang Qian, a commentator from the Beijing Youth Political College, an institution controlled by the Party’s Youth League, noticed a disturbing trend:

The majority of young people who are in favor of Jiao Yulu rationalise their choice in general ‘humanist’ terms. They evaluate him from various angles: ‘love,’ ‘conscience,’ and ‘self-fulfillment.’ They do not base [their decisions] on the social or political efiectiveness [of Jiao as a role model or exemplar of the Party].

Translating this statement into ‘bourgeois liberalist’ terms, it was evident that even those readers who opted for Jiao Yulu had made their choice on the basis of such concepts as ‘abstract human value’ or ‘humanist’ considerations, both of which were anathema to official class-based Party propaganda, and which had been repeatedly denounced since the early 1950s, and in particular since 1983. In other words, the correspondents were making the right choice for the wrong reason.

In summation, the editors of the Beijing Youth News found that many of young people simply failed to see the relevance of Jiao Yulu as a viable role model. ‘He made life too much of a ‘chore’. If you can’t protect and respect yourself, if you don’t attempt to develop and perfect yourself but choose to squander your efforts in selflessly giving to others, then you’re wasting your energies. Or to put it more crudely, your life will be a failure.’

Thus, in the early 1990s’ marketplace of ideological influence, the style of propagandistic cajoling itself had to take on a new face. ‘Of course’, the concluding editorial opinion of the Beijing Youth News stated, ‘you are free to achieve your ideals according to your preferred lifestyle, but at least you should recognize the validity of Jiao Yulu’s approach. Such recognition is the first positive step.’

— some of this material is adapted from

Geremie R. Barmé, In the Red, New York, 1999

***

As we noted earlier, Xi Jinping’s Jiao Yulu epiphany came in 1966. In 2009, when still only a member of the Party’s Politburo Standing Committee and an aspirant for ultimate leadership, he visited the Jiao Yulu Exhibition at Lankao county and planted a ‘Jiao paulownia’. As part of the anti-corruption campaign he was leading as head of the party-state from 2012, he focussed on the malfeasance of Party leaders and bureaucrats. In 2014, he visited Lankao twice. Declaring that ‘My heart always carries Comrade Jiao Yulu’s image’ 焦裕祿同志的形象一直在我心中 Xi instructed all Party members to ‘look in the mirror of Jiao Yulu’ to see whether they measured up to his high standards of selfless service. Xi also invited the Party Committee of Lankao to make reports to the Politburo in the Party compound of Zhongnanhai and chaired meetings of the Politburo that focussed on the study of Jiao Yulu’s spirit. He also made Lankao an object of his efforts at rural poverty reduction.

In Xi Jinping’s New Epoch, and in the age of Homo Xinensis, the limitations of Jiao Yulu as a role model both for Party cadres and the society at large, are more extreme than they were in the early 1990s. Yet Xi Jinping persists. The popular online author Murong Xuecun (慕容雪村, 1974-) summed up Xi’s unrealistic vision in a scathing analysis:

In 1966, the state media dispatched journalists to Lankao to research Jiao Yulu. They wrote in People’s Daily: ‘From the moment he joined the revolution, right on through to becoming a county party secretary, Jiao Yulu embodied the true qualities of the working people. He was down-to-earth as he worked among the masses with his trousers rolled up his legs and his cadre’s tunic rarely buttoned up all the way. Just like the poor peasants with mud all over them, Jiao too was all muddy. His socks were filled with holes that were darned, and darned again. When his wife bought him a new pair he said, “Compared with poor peasants, I’m well-dressed.” ‘

A hero was born. The media hailed him for years as a model party secretary and an outstanding Communist. It was said that he never took a day off from work. He would pay visits to help local people — even when he himself was starving or ill. A movie was made about him. In death, Jiao Yulu became the perfect bureaucrat — and a household name.

China has a centuries-long tradition of promoting so-called moral models. The Communist Party over the years has introduced many model workers, model peasants and model cadres. …

Today, old party icons won’t resonate with a public that is increasingly skeptical of propaganda. Too many ordinary citizens have lost faith in a system that is socialist in name only. Officials have cast aside all proletarian pretenses, and some have accumulated enough wealth to be counted among the world’s superrich. The endemic corruption has added to the loss of trust in the leadership.

Corrupt officials themselves don’t even trust the system. Many have become ‘naked officials’ [裸官], a term to describe corrupt leaders whose spouses, children or relatives emigrate overseas. It’s interesting to note that officials who flee to foreign countries with illicit gains tend to be lower in seniority than ever before: Ill-gotten wealth is expanding to all levels of the government.

If Mr. Xi truly wants to stop corruption, he must establish a transparent government, independent of the party, which puts officials under constant scrutiny. He would have to ensure that law enforcement can conduct independent investigations into corruption cases without being subject to interference from officials. He would have to allow the media to report freely on scandals. He would have to return to Chinese citizens the right to hold officials accountable.

But instead, his government has been locking up advocates of greater transparency.

Shortly before Xi Jinping visited the Jiao Yulu Memorial Hall, a court sentenced Xu Zhiyong, the legal scholar who led a campaign for social justice, to four years in jail. Mr. Xu and others, like Ding Jiaxi and Zhao Changqing, have been thrown into prison for demanding that officials publicly disclose their personal assets.

It’s true that since Mr. Xi took power in late 2012, several high-level officials have been arrested for corruption. But when I see a government that implores officials to emulate the supposed selfless clean living of Jiao Yulu while imprisoning people who urge leaders to reveal their assets, I have to ask: Does the government really intend to weed out corrupt officials or is it just putting on a show? This anticorruption campaign appears to be nothing more than a political purge by another name.

Jiao Yulu did not improve the standard of living in Lankao County in his lifetime, and he will not stop corruption in China in his latest afterlife. If he were alive today, Jiao Yulu would most likely be corrupt. When there are no restraints on power, when many government officials are exploiting their positions for profit, and when the whole country is worshiping money, would Jiao Yulu still choose to wear old socks full of holes?

— Murong Xuecun, Beijing’s Facts, and Fictions

The New York Times, 16 April 2014

***

Also in 2014, the official Chinese media reported that in the half-century since Jiao Yulu’s exploits were first reported in the People’s Daily in 1964, he had featured on the front page of the paper no fewer than seventy-five times.

Nurturing New People 育新人

A Chronology

In an extended essay titled ‘On the New People’ 新民說 published from 1902 to 1906, the late-Qing thinker Liang Qichao (梁启超, 1873-1929) declared that it was necessary to ‘renew’ the Chinese people in the context of the modern world and in his writings he offered ways and means to achieve the transformation. Like many people at the time, Liang was influenced by the racism of Western imperialist nations and Japan which cast Chinese people as innately inferior and backward. The impact of Christian missionaries both on the uplift and denigration of Chinese culture and Chinese people was also immense. The twentieth-century obsession with the ‘national character’ 國民性 was also profoundly influenced by nativist anti-Manchu racism related to barbarians, decadence and The Other which found violent expression during the Taiping War of the mid-nineteenth century and the pogroms against Manchus following 1911.

Liang, like the revolutionary Sun Yat-sen after him, and the writer Lu Xun, would all bemoan the fact that the Chinese were like ‘a platter of loose sand’ 一盤散沙 with no unifying ethos or purpose. The impetus to educate, nurture and reform the character and wayward nature of the common person had been at the heart of Chinese thought and culture long before the dynastic era; it has thrived in the modern world and it continues today under the Chinese Communist Party. Homo Xinensis is merely the latest phase in the evolution of this tirelessly didactic approach to human life.

Over the years, efforts to modernise Chinese society have focused on the issues of the quality 素質 and level of civilisation 文明 of average people (as judged by the power-holders, the wealthy and the self-appointed intellectual mentors of society). Many thinkers, mostly men and always people who belong to the educated caste, spoke of the urgent need to remake the national character 國民性 so that China could slough off tradition to become a vibrant, modern state. In 1934, during the Republican era, the Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek launched a ‘New Life Movement’ 新生活運動, with its Confucian and Christian undertow, to counter the influence of Communist ideology and to correct backward aspects of ingrained public behaviour; the movement promoted orderliness, cleanliness, simplicity, frugality, promptness, precision, harmoniousness and dignity.

After invading China in 1937, the Japanese in turn attempted to impose their version of modern Asian behaviour on the country. When, in the late 1940s, the Chinese Communist Party came to power, it also quickly moved to clean up the vestiges of what it called ‘feudal’ China to create a model, new, socialist People’s Republic. The Patriotic Education Campaign of the early 1950s, featured in Drop Your Pants! (Part I), was only part of this process. Meanwhile, after Chiang’s government retreated to Taiwan, campaigns to transform the citizenry continued, not always with great success, as the satirist and historian Bo Yang (柏楊/郭衣洞, 1920-2008) noted in his controversial 1985 book The Ugly Chinaman 醜陋的中國人.

The making of modern citizens, and consumers, is hardly unique to China. That it has been constantly embroiled with politics, in particular the party-state that featured in Drop Your Pants! (Part II), is noteworthy. Before introducing the desiderata for New People issued by the Party in August 2018, below we offer a brief survey of attempts to recreate the People 民/人民 over the past century. In particular, we would note the importance for the party-state, be it that of the Nationalists or the Communists, to train generation after generation of young people to join the ranks of ideologically suitable patriots. As each generation ages, or becomes disaffected, new candidates are groomed.

Although this chronology touches on the dynastic and Republican eras, the focus is on the Communist Party and the People’s Republic of China.

***

Homo Xinensis

Over a Century in the Making

The term renewing the people does not mean that our people must give up entirely what is old in order to follow others. There are two meanings of renewing. One is to improve what is original in the people and so renew it; the other is to adopt what is originally lacking in the people and so make a new people. Without both of these, there will be no success….

新民云者,非欲吾民盡棄其舊以從人也。新之義有二:一曰,淬厲其所本有而新之,二曰,採補其所本無而新之。二者缺一,時乃無功。先哲之立教也,不外因材而篤與變化氣質之兩途。斯即吾淬厲所固有採補所本無之說也。一人如是,眾民亦然。

— Liang Qichao 釋新民之義

A good harvest serves a year; a tree is good for ten; a person is worth a century.

樹谷一年,樹木十年,樹人百年

— traditional proverb

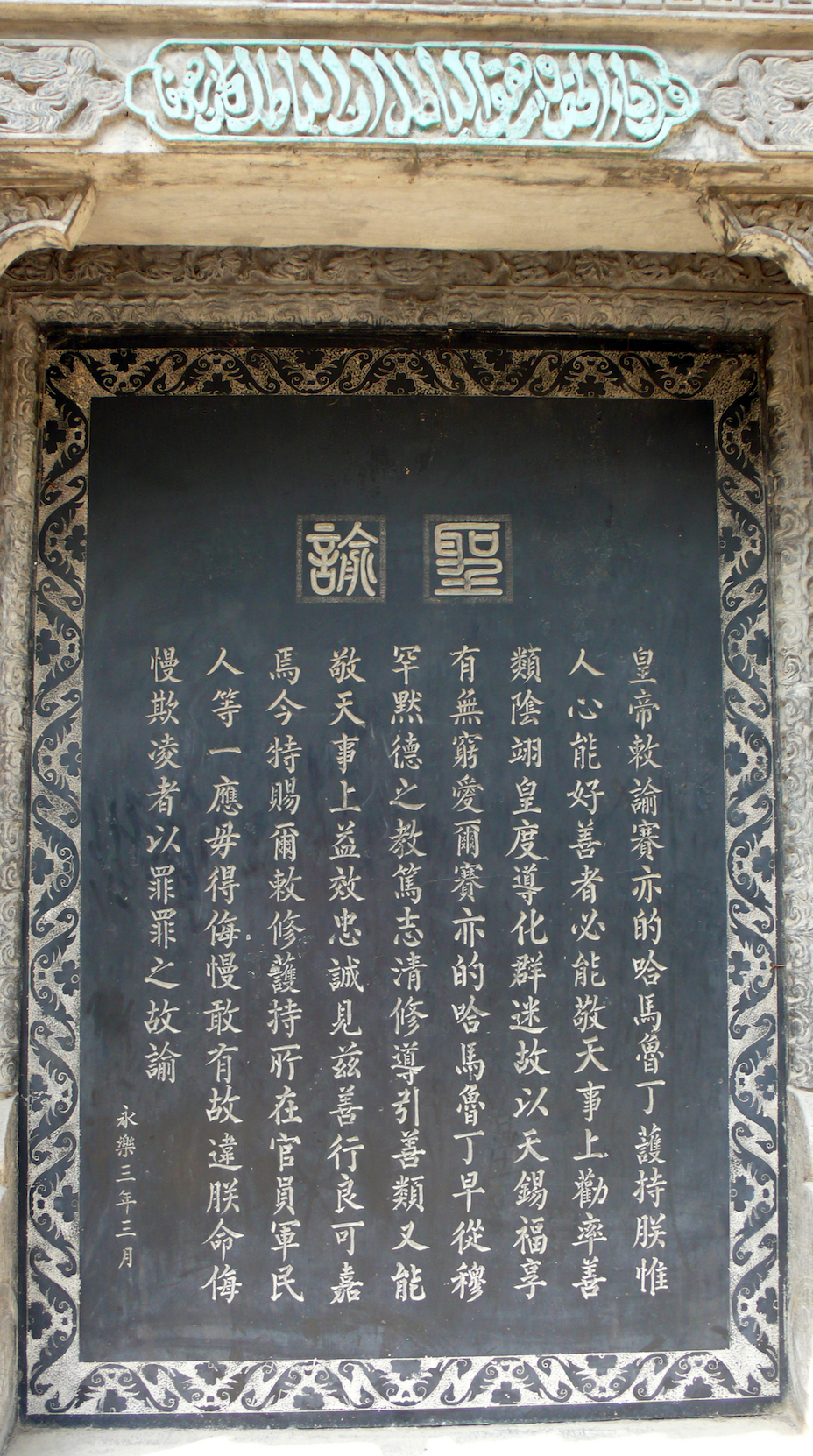

- Before 1912: in their role as Son of Heaven and exemplar, emperors of both the Ming and Qing dynasties are active in educating and exhorting their subjects. In 1670, Hiowan yei 玄燁 (known as the Kangxi Emperor) issues his Sacred Edict 聖諭, sixteen pithy maxims on good behaviour and Confucian ideas. The Edict is posted throughout the country and is supposed to be read out and explained to assembled townsfolk twice a month. His son and royal successor, In jen 胤禛 (the Yongzheng Emperor), issues his lengthy Amplified Instructions on the Sacred Edict 聖諭廣訓 in 1724 in the various languages of the empire. (see The Christian Conundrum of Yongzheng, China Heritage, 13 April 2018)

- The Republic: from 1912 debates over public ethics, political character, the education of the young revolve around radical and conservative philosophies. Patriotic fervour, progressive attitudes and hygiene commingle

- 1912: as the first Minister of Education in the newly founded Republic of China Cai Yuanpei (蔡元培, 1868-1940) advocates ‘Five Nurtures’ 五育 or forms of education 教育: Military, Pragmatic, Public Morality, Weltanschauung and Aesthetic Education 軍國主義教育、實利主義教育、公民道德教育、世界觀教育及美感教育. These ideas would influence later political leaders like Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping, both of whom promote ‘Moral, Intellectual and Physical’ 德智體 training for young people both before and after the Cultural Revolution (c.1964-1978)

- 1912-: Kang Youwei (康有為, 1858-1927) is a close associate of Liang Qichao and formerly a reformist thinker and activist. Concerned that the new Republic lacks a unifying belief system, as well as being inspired by (and jealous of) the successes of Christian missionaries in spreading their faith in China, Kang leads a push for the nation to Revere Confucius 尊孔. He proposes to the government that Confucianism be made the state religion 國教 and funding made available for temples, ceremonies and national holidays

- 1915-1916: the confabulated ‘Confucian Religion’ 孔教 of Kang Youwei is supported by the would-be emperor Yuan Shikai (袁世凱, 1859-1916). The movement struggles after Yuan’s unsuccessful attempt in late 1915 to establish the Empire of China 中華帝國 with him as its first emperor. At this time, the Lake Palaces 中南海 next to the Forbidden City — the seat of the Communist party-state since 1949 — are named China Palace 中華宮, the main entrance to which is New China Gate 新華門 on Chang’an Avenue. In response to Kang’s efforts, and the attempt by cultural conservatives to impose ‘the study of Confucian classics’ 讀經 on the post-dynastic education system, one of the main slogans of the iconoclastic New Culture / May Fourth Era (c.1917-1927) is ‘Destroy the Confucian Family Business’ 打到孔家店. In the process, the rejection of tradition and extolling of the New and the Current, traditional learning and respect for teachers and mentors come under attack. This spirit also motivates student attacks on teachers after 1949 and in the Cultural Revolution era. Mao Zedong returns to the anti-Confucian theme in the early 1970s but, after his demise, State Confucianism is revived as part of the Communist attempt to create its own ‘Spiritual Civilisation’, with the involvement of scholars like Tang Yijie and a host of state-funded New Confucian 新儒家 thinkers

- 1917: in the April issue of La Jeunesse 新青年 a writer signing himself ‘Mr Twenty-eight Strokes’ 二十八畫先生 (after the number of brush-strokes in his name, that is, Mao Zedong 毛澤東) publishes A Study of Physical Education 體育之研究 in which he extols rigorous training of the body 體 along with the inculcation of morality 德 and knowledge 智 in the nation’s youth

- 1918: Lu Xun (魯迅, 1881-1936) publishes his first work of fiction, ‘Diary of a Madman’ 狂人日記, an attack on the hypocrisy of traditional morality and its lingering threat to China’s young people. The story ends with the most famous line in modern Chinese literature: ‘Save the Children!’ 救救孩子. Over the following decades, Chinese ‘childhood’ is invented and populated by a range of characters in literature, poetry and film. Educators and politicians clash over whether children should be regarded as actors in China’s political struggles. This tussle reaches a climax with the Red Guard movement of the Cultural Revolution, and it has continued since

- 1919: 4 May, patriotic university students protest against the supine Chinese government and Japan’s imperial ambitions. This ever-expanding era of political awareness and activism also embraces consumerism: to reject foreign-made goods is promoted as an act of practical patriotism. Support for China-made goods 國貨 becomes a feature of patriotism and political awareness over the next century

- 1919: shortly before committing himself to Marxism and the ideas (and practices) of the Russian revolution, Mao Zedong writes:

‘I venture to make a singular assertion: one day, the reform of the Chinese people will be more profound than that of any other people, and the society of the Chinese people will be more radiant than that of any other people. The great union of the Chinese people will be achieved earlier than that of any other people. Gentlemen! Gentlemen! We must all exert ourselves! We must all advance with the utmost strength! Our golden age, our age of glory and splendor, lies before us!’ (trans. Stuart Schram, Mao’s Road to Power, vol.I, 1992, p.389)

- 1919: October, in a famous, and oft-quoted, essay titled ‘How Should We Be as Fathers Today?’ 我們現在怎樣做父親, Lu Xun writes:

‘Despite carrying an enormous burden of old customs and traditions, a person can nonetheless hold up the gate of darkness, bearing its weight on his shoulders, to let the children out so that they may enter the vast and bright world beyond and lead happy lives thereafter as decent and responsible human beings.’自己背著因襲的重擔,肩住了黑暗的閘門,放他們到寬闊光明的地方,此後幸福地度日,合理地做人。 (trans. Hsia Tsi-an, in Gloria Davies, Lu Xun’s Revolution, 2008, pp.288-289)

This humanistic view and the hope for a bright future for young people was overwhelmed by political imperatives time and again. It is also in stark contrast to the Communist Party’s post-1949 attempts to engineer variously the New Socialist Person, Communist Successors and New People (see below for details)

- 1920s: progressive educators struggle with the Nationalist Party authorities who imposed ‘Party-fied Education’ 黨化教育 that is pro-Nationalist patriotic and political curricula on schools. The tussle continues for decades, although patriotic education becomes a major feature of the school system during the war with Japan (1937-1945). The Communist patriotic education campaigns from 1951 onwards continue and vastly enhance this Nationalist Party pedagogical tradition

- 1927: March, in his Report on an Investigation of the Peasant Movement in Hunan 湖南農民運動考察報告 Mao Zedong observes:

‘A man in China is usually subjected to the domination of three systems of authority: (1) the state system (political authority), ranging from the national, provincial and county government down to that of the township; (2) the clan system (clan authority), ranging from the central ancestral temple and its branch temples down to the head of the household; and (3) the supernatural system (religious authority), ranging from the King of Hell down to the town and village gods belonging to the nether world, and from the Emperor of Heaven down to all the various gods and spirits belonging to the celestial world. As for women, in addition to being dominated by these three systems of authority, they are also dominated by the men (the authority of the husband). These four authorities — political, clan, religious and masculine — are the embodiment of the whole feudal-patriarchal system and ideology, and are the four thick ropes binding the Chinese people, particularly the peasants.’ 中國的男子,普通要受三種有系統的權力的支配,即:(一)由一國、一省、一縣以至一鄉的國家系統(政權);(二)由宗祠、支祠以至家長的家族系統(族權);(三)由閻羅天子、城隍廟王以至土地菩薩的陰間系統以及由玉皇上帝以至各種神怪的神仙系統——總稱之為鬼神系統(神權)。至於女子,除受上述三種權力的支配以外,還受男子的支配(夫權)。這四種權力——政權、族權、神權、夫權,代表了全部封建宗法的思想和制度,是束縛中國人民特別是農民的四條極大的繩索。

Ninety years later, Mao’s words still ring true.

- 1927: April, the purge of Communists in the Nationalist Party known as ‘Party Purification’ 清黨 begins. The collapse of an unsteady ‘united front’ results in a ninety-year split in Chinese political life that continues to have profound ramifications, including the ongoing militarisation of society on the Mainland

- 1934: launched in February by Chiang Kai-shek (蒋中正, 1887-1975), the head of the party-state Nationalist Government of the Republic of China, the New Life Movement 新生活運動 is a military-style ethics-cum-etiquette campaign aimed at transforming the national character and improving public behaviour. Heavily influenced by Methodism (Chiang had converted to this Christian sect at the behest of his wife Soong Mei-ling 宋美齡 in 1931), it promotes Neo-Confucian values — excoriated by progressive students and intellectuals during the May Fourth era as being socially reactionary — such as Proper Ritual Behaviour 禮, Righteousness or Justice 義 according to reformulated State Confucianism, Uncorruptability and Cleanness 廉 and a Sense of Shame or right and wrong 恥. These values are taught in schools and encouraged nationwide; they are supposed to unite a country facing the threat of the ‘immoral Communists’. The New Life push is supported by the quasi-fascist Blue Shirts Society and the Nationalist Party’s right-wing CC Clique. Christian missionaries in China are also enthusiastic about New Life. Commentators remark about Chiang Kai-shek that despite the excesses of the campaign there was ‘Methodism in his madness’. In many respects, the Communist Party’s Patriotic-Hygiene movement of the early 1950s and the Core Socialist Values of recent times are similar both in terms of intent and content to the New Life Movement of the 1930s. Having evolved in an institutional vacuum and without social norms they are used to clean up society (including the banning of drug taking, prostitution, pornography and so on) and impose politically motivated moral standards for the purpose of strengthening Party hegemony

- 1935: the advent of the New Soviet Person, a model of ideological strength and industrial productivity. It is claimed that, on 31 August 1935, Aleksei Stakhanov mined 102 tons of coal in less than six hours (fourteen times his quota). The ‘Stakhanovite Movement’ encourages model workers in all industries. Shortly thereafter, the Stalinist credo of ideological loyalty coupled with high productivity is introduced to the Communist guerrilla base in Yan’an. It combines with Chinese concepts of enumeration, agricultural yields and collectivity to influence China’s own form of the ‘New Person’

- 1936: although one Chinese athlete competed in the 1932 Los Angeles Olympic Games — Liu Changchun, described in the official Games’ report as ‘the lone representative of four hundred million people’ — the 1936 Berlin Olympics was the first of the modern games to which the Republic of China made a major commitment. The Chinese national team consists of sixty-nine athletes. A games during which race was such a contentious issue, is also a disaster for China. The historian Zhang Junjun remarks, ‘our delegation presented the world with … “total annihilation”.’ Zhang blames it on the inferior quality 素質 of the Chinese nation, its racial weakness and the lack of northern martial spirit. This humiliation is recalled in 2008 when the People’s Republic of China hosts the XXIXth Olympiad in Beijing

- 1937: October, in an address to the recently founded North Shaanxi Public School 陝北公學 on the occasion of the first anniversary of the death of the writer Lu Xun, Mao Zedong outlined his vision for the school, and the progressive youth of China (translated above)

- 1937: September, the Party thinker Liu Shaoqi presents his lectures titled The Cultivated Communist 論共產黨員的修養 in Yan’an. Drawing on Marxist-Leninist materials and traditional Chinese concepts, consisting mostly of quotations from the Confucian thinker Mencius, Liu’s speech becomes a key document in the 1942-1944 Rectification Movement and Thought Reform of Party cadres which, in turn, will influence the Thought Reform Movement and patriotic re-eduation of China’s intelligentsia in the early 1950s

- 1938: the Stalinist History of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks): Short Course, or 蘇聯共產黨(布爾什維克)黨史簡明教程 in Chinese, is published in the Soviet Union and is soon translated into Chinese. Imposed on Soviet citizens, it is carefully studied by Mao and his comrades. The historian of Marxism Leszek Kolakowski calls Short Course History of the CPSU(b) a ‘textbook of false memory and double thinking’. It has a profound impact on the upcoming Yan’an Rectification Campaign and the Sovietisation of Chinese life and thought in the 1950s. Called by some a Stalin-approved ‘bible’ of Marxism-Leninism, the book guides the Chinese Communists in how to apply abstract Soviet theories to Chinese reality, with generally disastrous results. It remains a basic text for understating Xi Jinping’s New Epoch and Homo Xinensis

- 1942-1944: the Party Rectification Movement and Salvation Movement promote Mao’s ideas and leadership starting with the publication of his secretary Hu Qiaomu’s article ‘Dogma & Pants’ (see Ruling The Rivers & Mountains — Drop Your Pants! (Part I)

- 1949: in response to the US White Paper on China’s Civil War, Hu Qiaomu drafts ‘A Confession of Helplessness’ 無可奈何的供狀 which is revised by Mao and published on 12 August 1949. Thereafter, the Party Chairman scribbles a note to Hu: ‘take advantage of the White Paper to expose the plots of the imperialists. Excerpted comments from the international media should also be published.’ Together they publish five critiques of US policy and democracy. The essays condemn China’s democratic activists and independent intellectuals as an impotent, but latent ‘Third Force’. This marks the beginning of the end of China’s twentieth-century liberal political tradition. These documents form the basis of the anti-Americanism of the 1951 Patriotic Re-education Campaign and are quoted frequently in subsequent political movements. They are central to the anti-Western canon of the People’s Republic to this day (for the full texts of these critiques in English and Chinese, see ‘Mao Zedong on the United States, 1949’ in White Paper, Red Menace, China Heritage, 17 January 2018)

- 1951-1952: the Three-Anti (1951) and Five-Anti Campaigns (1952) 三反五反運動 are launched to purge the society of class enemies while also responding to the corruption of Party cadres who now rule China. What is in essence a social purge is thus linked to a political purge; this model is repeated many times over the following decades. From 2012, Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign continues in the lineage of the Yan’an Rectification, the Three and Five Antis, as well as the purge of ‘Capitalist Roaders’ (that is corrupt Party cadres and factional enemies) during the 1964 Socialist Education Campaign and the subsequent Cultural Revolution. Incessant political campaigns, purges, education awareness efforts and state monitoring intimidate and domesticate the population so that it responds, however unwillingly, to the shifting demands of Party leaders

- 1951: at the suggestion and with the help of Liu Shaoqi, Hu Qiaomu publishes Thirty Years of the Chinese Communist Party 中國共產黨三十年. Zhou Enlai uses it in his September address to university academics and administrators on Thought Reform, mentioned earlier. This leads to a national campaign that requires intellectuals to reject Western academic norms in favour of Party priorities in education. Tang Yongtong, Tang Yijie’s father, is one of the prominent Peking University academics who feels obliged to petition Party leaders to help ‘re-educate’ China’s educators. University students take part in the denunciation of their teachers’ Western bias and lack of patriotic and proletarian fervour in the tradition of the May Fourth iconoclasm. The July 2018 Patriotic Education campaign continues the near-seventy-year history of cajoling thought remoulding and ideological compliance while recalling the attacks on university teachers and intellectuals in the early 1950s, and subsequently during the Cultural Revolution

- 1952: December, the Central People’s Government issues instructions for a national Patriotic Hygiene Campaign 愛國衛生運動 (愛衛, for short) to be carried out in 1953. In part a response to fears that Americans are using germ warfare in Korea, which the Chinese army has invaded to support the Communist North, and as part of the patriotic education campaign already being carried out, Patriotic Hygiene combines cleaning out ideological canker with health measures. Henceforth, both are pursued as political campaigns involving mass mobilisation. During this period, China’s urban areas are also being cleaned up, both by civic campaigns to improve the environment and also through purges of gambling and opium dens, as well as of prostitutes

- 1953: Mao and the education establishment announce the need to train ‘Three Good Students’ 三好學生, that is students with ‘Good Ideology, Good Study Habits and Good Athletic Abilities’ 思想品德好、學習好、身體好. These criteria will be used by the Communist Young Pioneers and form the basis for ‘Moral, Intellectual (that is, ideological) and Physical’ 德智體 training which resurfaces after the Cultural Revolution along with ideas related to ‘Spiritual Civilisation’

- 1954: a critique of ‘bourgeois-style’ scholarship related to the famous Qianlong-era novel The Dream of Red Mansions 紅樓夢 is used by Mao and the Party to denounce the May Fourth thinker and liberal democrat Hu Shi. The purge is aimed at snuffing out Hu’s influence in academic circles and imposing Marxist-Leninist scholastic methodology throughout the country’s tertiary institutions. The attacks on Hu Shi include an intensified negation of China’s modern liberal democratic tradition (see 1949 above), as well as a rejection of Western concepts of abstract humanity, individual human worth and human rights. This is a stance that the Communists maintain to this day

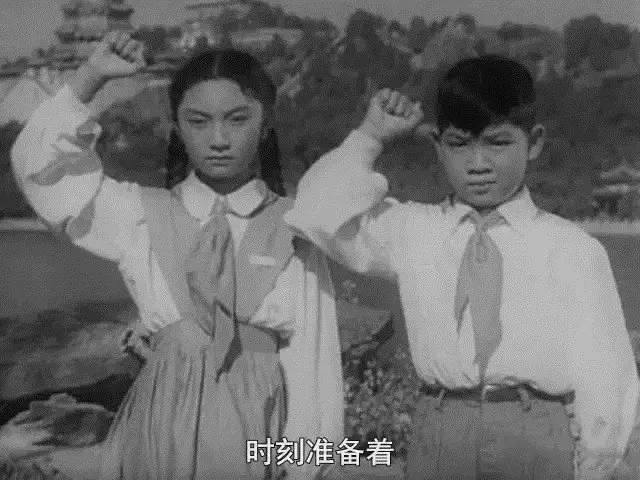

- 1955: the film Blossoms of the Fatherland 祖國的花朵 offers an idealised vision of patriotic, pro-Party children in the People’s Republic. A song in the film, ‘Let’s Paddle Our Boats’ 讓我們蕩起雙槳, becomes an unofficial anthem for children

- 1956: Mao and the Party call on pre-1949 democratic individualists and liberal activists, along with the nation’s intellectuals and workers, to help the Party ‘rectify its work style’ in an avowed attempt to modulate unpopular and harsh one-party rule. Mao hopes to rekindle the spirit of the Yan’an Rectification of 1942-1944, but people dissatisfied with Communist corruption and authoritarianism, and encouraged by populist rebellions in Poland and Hungary, both Soviet satellite states, speak out in what wells up into a crescendo of articulate protest

- 1957: from mid-year the ‘open door rectification’ 開門整風 involving intellectuals and students turns into an anti-Party mêlée. Fearful that Peking University student protesters — known as the ‘May Nineteenth Movement’ 五一九運動 — and striking workers will foment a wider rebellion, Mao with the organisational genius of Deng Xiaoping launches a devastating purge. Hundreds of thousands of people are denounced, demoted, cashiered from their jobs, exiled or gaoled. What is known as the ‘Hundred Flowers, Hundred Voices’ 百花齊放、百家爭鳴 is the last concerted independent stand of China’s men and women of conscience, people who were educated prior to 1949. The resulting ‘Anti-Rightist Purge’ 反右運動 has fateful consequences for independent political activism, as well as intellectual and cultural freedom to this day

- 1958: when the Great Leap Forward whips up what is known as the ‘Communist Wind’ 共產風 of radical collectivisation, Mao declares that China has previously produced New Socialist People 社會主義新人, but now it is on the way to creating New Communist People 共產主義新人, a form of humanity unknown to previous civilisations. Once the misbegotten euphoria of the Great Leap passes, Mao abandons his ludicrous claim

- 1958: on 1 July, Mao composes two poems titled ‘Farewell to the God of Plague’ 送瘟神. In a preface he says: ‘When I read in People’s Daily of June 30, 1958 that schistosomiasis had been wiped out in Yujiang county [in Zhejiang province], thoughts thronged my mind and I could not sleep. In the warm morning breeze next day, as sunlight falls on my window, I look towards the distant southern sky and in my happiness pen the following lines.’ Thereafter, lines from these poems are used variously to extol The People in the abstract (‘Six hundred million in this land all equal Yao and Shun’ 六億神州盡舜堯) and to describe ideological malaise and the dispatching of counterrevolutionaries (‘We ask the God of Plague: “Where are you bound?” ‘ 借問瘟君欲何往):

I

So many green streams and blue hills, but to what avail?

This tiny creature left even Hua Duo powerless!

Hundreds of villages choked with weeds, men wasted away;

Thousands of homes deserted, ghosts chanted mournfully.

Motionless, by earth I travel eighty thousand li a day,

Surveying the sky I see a myriad Milky Ways from afar.

Should the Cowherd ask tidings of the God of Plague,

Say the same griefs flow down the stream of time.

其一

綠水青山枉自多,

華佗無奈小蟲何!

千村薜荔人遺矢,

萬戶蕭疏鬼唱歌。

坐地日行八萬里,

巡天遙看一千河。

牛郎欲问瘟神事,

一样悲欢逐逝波

II

The spring wind blows amid profuse willow wands,

Six hundred million in this land all equal Yao and Shun.

Crimson rain swirls in waves under our will,

Green mountains turn to bridges at our wish.

Gleaming mattocks fall on the Five Ridges heaven-high;

Mighty arms move to rock the earth round the Triple River.

We ask the God of Plague: ‘Where are you bound?’

Paper barges aflame and candle-light illuminate the sky.

其二

春風楊柳萬千條,

六億神州盡舜堯。

紅雨隨心翻作浪,

青山著意化為橋。

天連五嶺銀鋤落,

地動三河鐵臂搖。

借問瘟君欲何往,

紙船明燭照天燒。

— trans. Foreign Languages Press, Beijing

- 1959: November, Mao formulates a policy response to US Secretary of State John Foster Dulles’s Peaceful Evolution strategy. Peaceful evolution 和平演變 is promoted as a way of undermining the one-party states of the Socialist Bloc by encouraging dissent, cultural as well as political pluralism and human rights. Chinese leaders have been obsessed with this strategy ever since, and frequently identify it as a major, ongoing Western threat to the Party’s rule

- 1961: Party Central formally announces the ‘Red and Expert’ 又紅又專 policy that requires Party training and university education to emphasise political rectitude along with specialist knowledge. The formulation ‘Red and Expert’ reappears whenever Party leaders are concerned about the loyalty of the intelligentsia, in particular scientists. Under Xi Jinping this policy is emphasised once more

- 1962: ‘We Are the Heirs of Communism’ 我們是共產主義接班人, the theme song in the 1961 film Heroic Little Eighth Route Army Soldiers 英雄小八路 is released as a single. The song is taken up by schools nationwide just as the struggle over the future of the Party and Mao’s vision for China and world revolution intensified. It soon becomes China’s equivalent of the Nazi’s Horst-Wessel Lied:

We are Communist Successors,

Heirs to the glorious revolutionary tradition.

We love the Motherland, Love the People

Our bright red bandanas fluttering on our chests.

Fearing no difficulty, undaunted by the enemy,

We study hard and struggle relentlessly

Heroically advancing towards victory.

To victory, Advance!

Heroically advancing towards victory,

We are Communist Successors.

我們是共產主義接班人,

繼承革命先輩的光榮傳統,

愛祖國,愛人民,

鮮艷的紅領巾飄揚在前胸。

不怕困難,不怕敵人,

頑強學習,堅決鬥爭,

向著勝利勇敢前進,

向著勝利勇敢前進,前進!

向著勝利勇敢前進,

我們是共產主義接班人。

In 1978, the song is made the official anthem of the Chinese Young Pioneers 中國少年先鋒隊 or 少先隊, the Party Youth organisation founded in October 1949 on the model of the All-Union Leninist Young Communist League or Komsomol which was established following the Russian Revolution to identify and train pro-Party careerists from primary school onwards. The song’s themes of military struggle, patriotism and loyalty to the Party are echoed in the Core Socialist Values developed from the 2000s. The popular TFBoys (aka, ‘The Fighting Boys’ 加油男孩) rendition of ‘We Are the Heirs of Communism’ is released for the 1st of June Children’s Day in 2016. It adds a cloying new dimension to a limp-wristed burlesque. See:

Apart from the milksop 奶油小生 boy band this MTV features cameo appearances by various star athletes and scientists. It starts with a particularly ugly moment when a gaggle of youngsters visits the elderly Chi Haotian 遲浩田 who then lectures them as he fingers his own Young Pioneer’s red bandana. A former Politburo member and deputy chair of the People’s Liberation Army Central Military Commission, Chi helped design the martial law plan imposed on Beijing in May 1989; he also oversaw the logistics of the 4 June Beijing Massacre itself (see The Gate of Darkness, China Heritage, 4 June 2017)

- 1963: Lei Feng, a PLA soldier ‘martyred’ in an accident, is promoted as Chairman Mao’s Good Student and a call is issued for the nation to ‘Learn from Comrade Lei Feng’ 向雷鋒同志學習. Civics campaigns aimed at instilling the Lei Feng spirit of service, obedience and cleanliness have been a feature of Chinese life for fifty-five years

- 1964: July, in the Party’s ninth polemical response to an open letter addressed to it by the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (the nine Chinese responses are known as the Nine Critiques 九評 ), anxiety about training young people for the future is clearly outlined:

‘In the final analysis, the training of successors for the revolutionary cause of the proletariat is one of whether or not there will be people who can carry on the Marxist-Leninist revolutionary cause started by the older generation of proletarian revolutionaries … whether or not we can successfully prevent the emergence of Khrushchev’s revisionism in China. In short it is an extremely important question, a matter of life or death for our Party and our country.’ (from Roderick MacFarquhar and Michael Schoenhals, Mao’s Last Revolution, 2006, p.12)

- 1966: April, on the eve of the formal launch of the Cultural Revolution, the good Party cadre Jiao Yulu is extravagantly praised in the national media as a model for all Party members (see ‘The Chairman’s Tears’ above)

- 1966: the Cultural Revolution, formally launched in May this year, is supposedly an effort by the Party to train ‘Successors for the Proletarian Revolution’ 無產階級革命接班人 who can ‘brave the winds and waves’ 乘風破浪 and face the future after the founding generation of leaders passes from the scene. The youth rebellion is encouraged to vouchsafe The Red Rivers and Mountains of China 保衛紅色江山 and to ensure that the country never ‘changes color’ 永不變色, in other words, abandons revolution. The children of founding revolutionary cadres are encouraged to believe that China’s future is in their hands. To ensure ideological purity and progress, Mao and his colleagues call for the destruction of the old and creation of the new 破四舊立四新. Prominent academics and teachers, who have suffered through numerous movements since the 1951 Thought Remoulding Campaign, are denounced as ‘Reactionary Bourgeois Authorities’ 反動學術權威, subjected to relentless attacks, made to write out repeated self-criticisms, incarcerated and forced to study Mao Zedong Thought. Red Guards attempt to ‘purify the revolutionary capital’ of Beijing 淨化革命首都 by throwing out ‘bad elements’, that is, people who have been denounced for their ideological impurity during one, more, or all of the political campaigns since 1949. People’s Daily praises the Red Guards for ‘taking out the garbage’. In their turn, the Red Guards themselves are soon found to be ideologically impure, they too are expunged from the cities, as are intellectuals and non-essential Party cadres. They are disparately sent to rural areas for re-education through labour. Xi Jinping is among those ‘send down to the countryside’ 下鄉

- 1967: Along with his fall from power, Liu Shaoqi’s The Cultivated Communist is denounced. Having sold 18 million copies since 1949, it is now attacked as ‘Black Cultivation’ 黑《修養》 (the tag line is: ‘the more people are cultivated 越養, the more revisionist they end up 越修[正主義]’). Copies are pulped. Liu himself is accused of being a Nationalist Party agent and traitor. Having been expelled from the Party and denied medical care he dies in a makeshift prison

- 1967: January, following the destruction both of Party and state organs of power throughout the country, new administrative groups are created that consist of younger rebels, upcoming cadres and older politically reliable veterans. These ‘three-in-one’ 老中青三結合 bodies become the basis for re-inforced party-state rule. They are supposed to resolve the crisis over revolutionary successors. Following Mao’s death, the principle of ‘three-in-one’ leading groups is maintained