Drop Your Pants!

The Party Wants to Patriotise You All Over Again (Part V)

‘Drop Your Pants! The Party Wants to Patriotise You All Over Again’ is a five-part overview of the background and significance of the Patriotic Education Campaign launched by China’s Communist Party Central on the last day of July 2018.

Called an ‘Offensive to Promote the Spirit of Patriotic Struggle [that requires intellectuals to] Contribute Positively to Building the Enterprise in the New Epoch [of the Party-State and China]’ 弘揚愛國奮鬥精神、建功立業新時代活動 this latest campaign was fortuitously announced on 29 July 2018, only days after Xu Zhangrun 許章潤, a professor of law at Tsinghua University in Beijing, had published Imminent Fears, Immediate Hopes — a Beijing Jeremiad 我們當下的恐懼與期待 (trans. with notes, China Heritage, 1 August 2018). Although the two events had no causal connection, in his essay Xu warned of the dangers of China returning to the campaign-style, struggle-based politics and mass indoctrination of the Mao era. Campaigns, struggles, movements and purges have been the public manifestation of the political rhythms of China’s Communist Party since its founding nearly a century ago. In Xi Jinping’s New Epoch, and despite the burgeoning of civilian life over the last decades, this remains the case.

‘Drop Your Pants!’ 脫褲子 takes its title from an essay written by the Party ideologue Hu Qiaomu in 1942 at the beginning of a political campaign that transformed the Chinese Communist Party into what it is today. At the time, Hu, with the support of the Party leader Mao Zedong, exhorted his comrades to ‘drop your pants, cut off your [bourgeois] tails and wash yourselves clean’ in front of each other (脫褲子, 割尾巴, 洗澡). After the Communists took power in 1949, the process of ‘washing in public’ was imposed on government bodies and universities as part of a patriotic education campaign and nationwide thought remoulding.

This series is written in our in-house style of New Sinology 後漢學, and it consists of:

- Part I — Ruling The Rivers & Mountains — reviews the Thought Reform Movement of the early 1950s, which included the Party’s inaugural patriotic re-education putsch, and noted its connection to the Yan’an Rectification Movement of 1942-1943, which we discussed in Mendacious, Hyperbolic & Fatuous. We believe that a basic familiarity with those earlier movements is helpful in understanding not only the 2018 Patriotic Offensive, but also the Communist Party’s ‘correctional re-education’ 矯正教育 policies in Xinjiang and Tibet;

- Part II — The Party Empire — provides a short account of how, under various regimes and leaders, party and state have been melded and promoted in twentieth-century and early twenty-first century China. This contentious history is useful in appreciating that country’s politicised patriotism;

- Part III — Homo Xinensis — considers the history of the comrade-but-not-citizen and the hyper-patriots imbued with Core Socialist Values that are nurtured and encouraged by the party-state under Xi Jinping;

- Part IV — Homo Xinensis Ascendant — outlines the desiderata for Homo Xinensis today, and for the future. By way of contrast we also quote from Alexander Zinoviev’s Homo Sovieticus, the Doppelgänger of the New Person of Xi Jinping’s New Epoch; and

- Part V — Homo Xinensis Militant — this final installment in the series ‘Drop Your Pants!’, Lessons in New Sinology, discusses China’s political struggles, the Communist Party’s war without end, Red DNA 紅色基因, Peaceful DNA 和平基因, patriotic education and how traditions of conflict and the lyrical militancy of revolution commingle to create a romanticised warrior ethos.

In a future series of Lessons in New Sinology on the theme of Translatio Imperii, one of our topics will be Worrying About War. There we will offer an historical review of the age-old contention between the ‘civil’/ ‘literary’ 文 and the ‘militant‘/ ’warlike’ 武, as well as account for dynastic and modern anxieties over manly virtue, military prowess and war preparedness. On that theme questions related to military humiliations under the Qing, ongoing Western trade aggression, the influence of Meiji to Showa era Japanese militarism and imperialism, the impact of the Russian Revolution of 1917, the Versailles Treaty of 1919, the Sino-Japanese War, the Civil War and the Korean War will also be considered.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

1 October 2018

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank John Minford, co-founder of the Wairarapa Academy for New Sinology 清漪書院 (formerly 白水書院), for kindly reading over drafts of some of these essays. John, along with an other eagle-eyed friend who wishes to remain anonymous, pointed out many infelicities and typos in my habitually writhen prose, for which I am grateful. The errors that remain are mine. — Ed.

***

Prologue

Since the rise of Xi Jinping with his investiture as party-state-army leader in 2012-2013 (although, as we have previously noted, he revealed both his style and intentions both nationally, and internationally, from 2008), the pall of repression that has come to characterise his rule readily brings to mind the political and intellectual claustrophobia of late-Mao and the Cultural Revolution era (c.1964-1978).

Parallels between the China of today and the People’s Republic of the 1950s are also striking. As we have attempted to demonstrate in these Lessons in New Sinology, many of Xi Jinping’s policy approaches reflect in particular those boom days of Leninism-Stalinism-Maoism. That era too was, on a national scale, profoundly influenced both by the Party’s Yan’an years (1937-1947) and the Stalinism of the Soviet Union.

Xi Jinping’s vision for China entails stifling administrative control, micromanagement of Party life, counter-reformation economics, unrealistic rhetorical expectations for the society, as well as harsh measures in the realms of education, culture, cyberlife, religion and ethnic policy. Added to this is Xi’s emphasis on ritualistic confessions and thought remoulding. Of course, the drumbeat of High Maoism with its pervasive personality cult, the perfunctory study of the Leader’s works and a collective leadership stifled by a man with a Napoleonic sense of mission, and so on, beats steadily on. In both of those earlier eras — respectively known as the ‘first seventeen years’ 十七年 (1949-1966) and the ‘ten years of chaos’ 十年動亂 (1966-1976) — there were many constants, including a relentless ambition to outdo former rivals and an overweening desire for global prominence.

Like many members of his generation, Xi Jinping came of age while clinging on to youthful memories of a halcyon past. For him and other members of the Party elite, the non-stop political campaigns, the mass murder of class enemies, the purges within the Party and the gradual tightening of socialist policies over every aspect of society, were, like the Yan’an Rectification of 1942-1945, foundational to the life and success of the People’s Republic and its ruling party. It is for this reason that, through our essays on contemporary China, we encourage readers to learn more about that past, the presence of which is increasingly undeniable as the world engages with a seemingly ‘forward leaning’ People’s Republic.

In recent years, observers of the People’s Republic have become aware of the Communist Party’s United Front activities. These are aimed at developing a coalition of overseas Chinese patriots, political fellow travellers, unprincipled businesspeople, craven foreign bureaucrats, academics and useful idiots to support the international ambitions of China’s party-state. The United Front 統一戰線, however, is only one of the ‘Three Magical Weapons’ 三個法寶 that Mao Zedong declared to be essential for the victory of the Chinese revolution. The other two were ‘party building’ 黨的建設 (now simply referred to as 黨建) and armed struggle 武裝鬥爭 (see his October 1939 publication announcement for The Communist 《<共產黨人>發刊詞》 ).

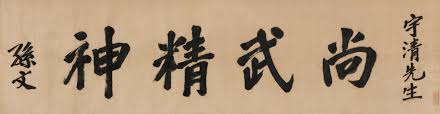

We have previously discussed the United Front in China Heritage — see The Battle Behind the Front, 17 September 2017 — and in the earlier chapters in ‘Drop Your Pants!’ we have spoken about Party consolidation, as well as contemporary patriotic education, values training and the nurturing of New People for the Chinese socialist cause. In this concluding essay, our focus is on the Martial Spirit 尚武精神 and the Chinese party-state’s attitude to struggle 鬥爭/奮鬥, be it physical, emotional or intellectual.

Militarism has been a central concern, and a point of anxiety for, Chinese thinkers, political activists and educators from the late-nineteenth century. Long before then, as we will indicate below, it was also an obsession of the Manchu Bannerman elite that conquered the Ming dynasty in the mid-seventeenth century and which ruled the Qing empire until 1912.

***

As the 1 June 2021 centenary of the founding of the Chinese Communist Party approaches, it is useful to consider an uncomfortable reality: the Party has, at many points in its history, been both openly, or covertly, in a state of war, or at least conflict, with China itself. Up until the founding of the People’s Republic in 1949 the battles were waged with armies, weapons, covert operations and propaganda. Since then, the struggle has been a protracted civil conflict engineered and overseen by generations of Party leaders and their apparatchiki. This war has taken many forms and in persecuting it the Party has employed numerous strategies, but overall it has consistently used coercive power — civilian, quasi-legal, police, para-military and military — to maintain the status quo and to realise the shifting agendas of the one-party state. In the process, the Communists have addressed a myriad of political, social, economic, cultural and global issues by employing the language of strife, struggle, contestation, contradictions and campaigns. Although the Communist Party may modulate its public utterances, in the exhortations to its citizens, as well as in its general disposition it maintains a martial stance.

— The Editor

The Youth of an Old Empire

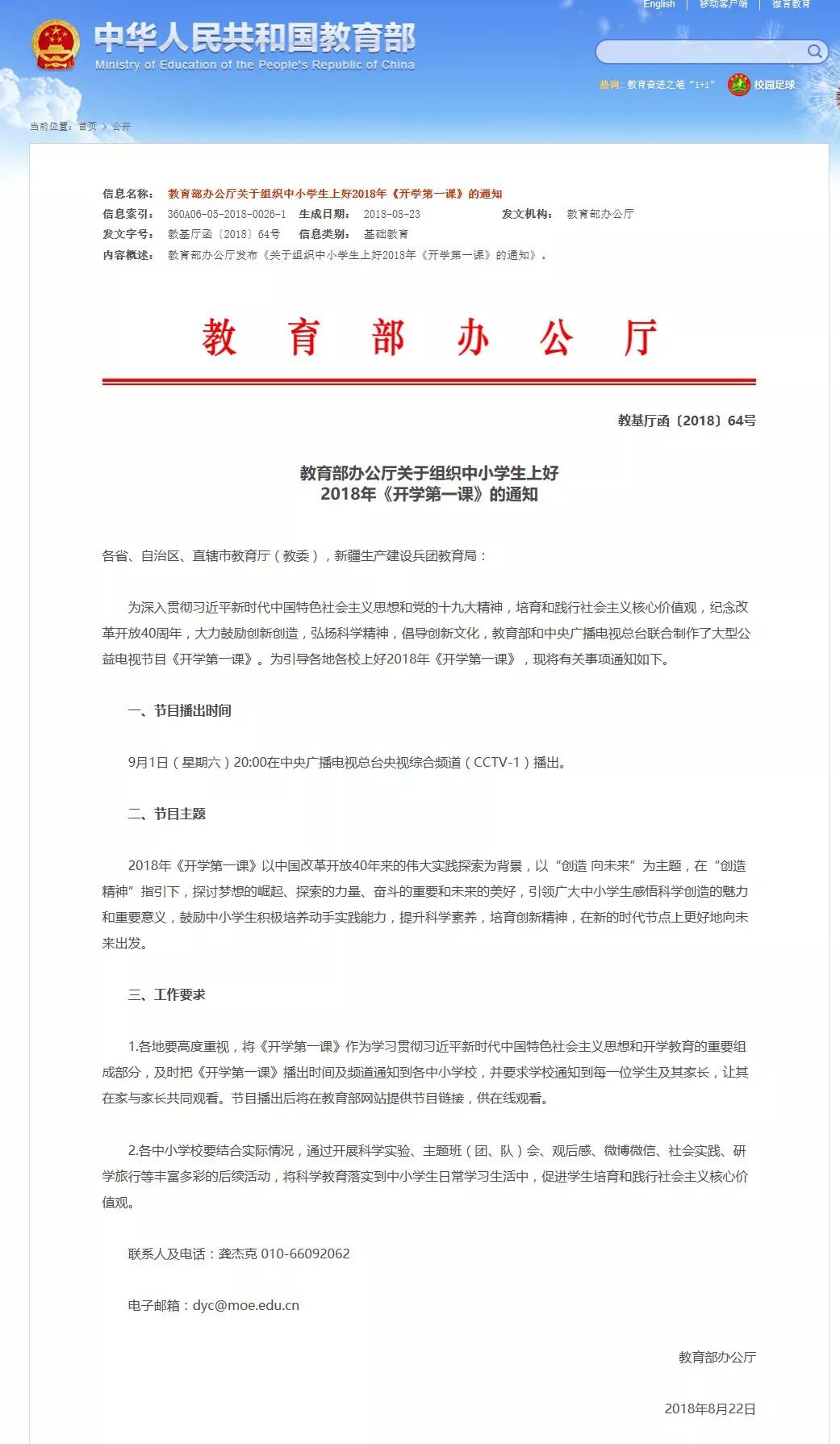

Since 2008, the Beijing Ministry of Education has collaborated with China Central TV to produce an annual programme called ‘First Lesson of the Year’ 開學第一課. Mandated viewing for primary and secondary school children throughout the country, the broadcast is ‘designed so that it can be assimilated by school-age children in a digestible format at the same time as it delivers pointed messages’ 靠他們喜歡的方式,使他們在潛移默化中受到陶冶,有利於增強教育的針對性。

On 1 September 2018, the first day of the 2018-2019 school year, the Ministry of Education instructed all schools to stream a broadcast from China Central TV on the theme of ‘Creating for the Future’ 創造向未來. Parents were also told that they could watch with show with their children at home.

A mixture of dances, games, lectures and songs, the multi-media simulcast lasted for over one and a-half hours. It was set against the backdrop of the four decades of economic reform inaugurated by the Party in late 1978. The theme of ‘Creating for the Future’ and in the ‘Spirit of Creativity’ was supposed

to delve into the Rise of the Dream, the Quest for Strength, the Importance of Struggle and the Beautiful Future. Through it the broad masses of primary and secondary school students will better appreciate the lure of scientific discovery as well as its vital importance. It will positively encourage students to pursue practical engagement with the sciences, enhance their overall scientific education, nurture a spirit of creativity and prepare them better at this crucial moment in the New Epoch for an unfolding future. 探討夢想的崛起、探索的力量、奮鬥的重要和未來的美好,引領廣大中小學生感悟科學創造的魅力和重要意義,鼓勵中小學生積極培養動手實踐能力,提升科學素養,培育創新精神,在新的時代節點.上更好地向未來出發。

‘First Lesson of the New School Year’ is also part of the mandated process of Nurturing New People 育新人 advocated by Xi Jinping (and discussed at length in Homo Xinensis Ascendant). It encourages the kind of patriotic scientific spirit among children that is essential for China’s continued rise as a global technical innovator. Propaganda activities like ‘First Lesson’ are germane to China’s Third Age, the Age of Might.

Despite the highfalutin rhetoric, the annual ‘First Lesson of the New School Year’ is essentially a variety show punctuated with edifying slogans, vague pedagogical encouragement and soft-sell Party nostrums. In 2018, as in previous years, it featured the popular milksop group TFBoys (aka, ‘The Fighting Boys’ 加油男孩), who have appeared both in Homo Xinensis and in The Gate of Darkness (China Heritage, 4 June 2017).

(Note: For officially selected highlights of the broadcast, see here — Ed.)

The show’s finale consisted of a song inspired by ‘Paean to Youthful China’ 少年中國說, an essay by Liang Qichao (梁啟超, 1873-1929), the late-Qing-dynasty thinker and political activist whose ideas on the need to remould the national character of the Chinese people we have also noted. Written shortly after the foreign-led suppression of the Boxer Rebellion of 1900 — a moment of extreme humiliation in the country’s ignominious dynastic decline — Liang says that although China appeared to be a feeble old empire, unlike many other ancient cultures of the world faced with the challenges of the vibrant imperialist trading nations, the country could be transformed. Its youth, in particular, were the hope for a world-changing rebirth. ‘First,’ Liang wrote, ‘one must speak of the differences between Old and Young’:

The Old contemplate the past, while the Young think of the future. Contemplating the past leads to nostalgia, while a mind fixed on the future is brimming with hope. Nostalgia breeds conservatism, while hope is about progress. The conservative cleaves to an unchanging yesterday, hope is about constant renewal today… 欲言國之老少,請先言人之老少。老年人常思既往,少年人常思將來。惟思既往也,故生留戀心;惟思將來也,故生希望心。惟留戀也,故保守;惟希望也,故進取。惟保守也,故永舊;惟進取也,故日新。…

The Old are like the setting sun; the Young are akin to sunrise. The Old are emaciated bulls; the Young are like suckling tigers. The Old are like monks, the Young like knights-errant. The Old are like dictionaries, the Young are operettas. The Old are opium, the Young brandy. The Old are like fallen meteors, the Young are coral reefs in the vast oceans. The Old are similar to the Pyramids, the Young more like the Trans-Siberian Railroad. The Old are like willows in late autumn, the Young are as the sprouting grasses of early spring. The Old can be likened to the marshes of a dead sea, while the Young are like the vibrant headwaters of the Yangtze. … I, Liang Qichao, aver that just as it is for people, so it is for nations. 老年人如夕照,少年人如朝陽;老年人如瘠牛,少年人如乳虎。老年人如僧,少年人如俠。老年人如字典,少年人如戲文。老年人如鴉片煙,少年人如潑蘭地酒。老年人如別行星之隕石,少年人如大洋海之珊瑚島。老年人如埃及沙漠之金字塔,少年人如西伯利亞之鐵路;老年人如秋後之柳,少年人如春前之草。老年人如死海之瀦為澤,少年人如長江之初發源。… 梁啟超曰:人固有之,國亦宜然。

Liang famously warned that while dynastic China was old and faced extinction, as a modern nation-state China would prove to be youthful and vibrant. He concluded with a declaration:

Today’s responsibility lies with the youth. If the youth are wise, the country will be wise. If the youth are wealthy, the country will be wealthy. If the youth are strong, the country will be strong. If the youth are independent, the country will be independent. If the youth are free, the country will be free. If the youth progress, the country will progress. If are youth are better than Europeans, China will be better than Europe. If our young people are more heroic than the rest of the world, China will be more heroic than the rest of the world. 故今日之責任,不在他人,而全在我少年。少年智則國智,少年富則國富;少年強則國強,少年獨立則國獨立;少年自由則國自由;少年進步則國進步;少年勝於歐洲,則國勝於歐洲;少年雄於地球,則國雄於地球。

In the 1st of September 2018 ‘First Lesson for the New School Year’, this exhortation was turned into a diachronous duet that Liang Qichao ‘performs’ with the popular singer Jason Zhang (張傑, 1982-). A chorus of children dressed variously in faux Han costumes in the style of a traditional scholar’s garb and the Soviet-inspired uniforms of the Communist Young Pioneers sang Liang’s lines. Zhang responded with lyrics that he had composed with the well-known writer Ershui 二水:

The new lyrics were replete with such images as the rising red sun, a hidden dragon bursting forth to soar heavenward, coursing torrents, heroic daring and pillars of the nation:

少年中國說

1. 合唱團:

少年智則國智

少年富則國富

少年強則國強

少年自由則國自由

少年智則國智

少年富則國富

少年強則國強

少年自由則國自由

2. 張傑:

紅日初升 其道大光

河出伏流 一瀉汪洋

潛龍騰淵 鱗爪飛揚

乳虎嘯谷 百獸震惶

少年自有 少年狂

身似山河 挺脊梁

敢將日月 再丈量

今朝唯我 少年郎

敢問天地 試鋒芒

披荊斬棘 誰能擋

世人笑我 我自強

不負年少

3. 合唱團:

少年智則國智

少年富則國富

少年強則國強

少年自由則國自由

4. 張傑:

幹將發硎 有作其芒

天戴其蒼 地履其黃

縱有千古 橫有八荒

前途似海 來日方長

少年自有 少年狂

身似山河 挺脊梁

敢將日月 再丈量

今朝唯我 少年郎

敢問天地 試鋒芒

披荊斬棘 誰能擋

世人笑我 我自強

不負年少

5. 合唱團:

少年自有 少年狂

心似驕陽 萬丈光

千難萬擋 我去闖

今朝唯我 少年郎

天高海闊 萬里長

華夏少年 意氣揚

發憤圖強 做棟梁

不負年少

6. 張傑:

發憤圖強 做棟梁

不負年少

完

Following an earlier performance of the song in March 2018, one media commentator had gushed that:

‘Paean to Youthful China’ celebrates the vibrant energy of youth. It expresses the undaunted spirit of China’s young people as they struggle to realise the might of the nation. 這一曲《少年中國說》極力歌頌少年的朝氣蓬勃, 也唱出了當代中國少年發奮圖強的精神風骨。

To this agèd ear the 1st of September televised rendition of this supposedly rousing song sounded more like the insipid and saccharine work of commercial boyband pop wrestling in a duet with a joyless and wooden chorus. ‘Paean to Youthful China’ was meant to extol the virtues of strength, independence and progress, but it more readily reflected the confusing and contradictory world of the Dialectic that we discussed at length in Homo Xinensis Ascendant. This is one in which every statement is countered by an impossible opposite. Young people long mollycoddled by soft-peddled politics and indulgent families now confront the Epoch of Xi Jinping: it is demanding, expansive, aggressive and, at its core, militant. At every turn, the demands of the Party must engage with and attempt to refashion the lived reality of prosperous young urbanites. Perhaps, as in previous revolutionary eras, the Party will find the most compliant foot soldiers for its cause among the impoverished families of the countryside or in the conurbations of its megacities.

Jason Zhang’s song also brought into focus the themes of our study of China’s latest Patriotic Education Campaign: the methods of political indoctrination; the melding of Party and state; the re-definition of traditional moral concepts for contemporary purposes and the training of young people to serve political ends. After all, Xi Jinping did declare in late 2017 that:

We must implement a national action plan led by Party cadres that starts with the family and gets hold of children when they are still infants 堅持全民行動、幹部帶頭,從家庭做起, 從娃娃抓起。

As older intellectuals and scientists who have been buffeted by constant swerves in policy might waver in their devotion to the party-state, new generations provide countless impressionable young minds, and ambitious parents willing to serve the cause. Due to an unremarkable mixture of idealism and pragmatism a percentage of these will be open to the Party’s insistent messaging, and constant demands.

***

Sparta in the Far East

During various eras, rulers have been anxious to inculcate a martial spirit among their subjects so as to ensure war preparedness. As the People’s Republic of China has increasingly harked back to former ages of greatness in recent decades, age-old military anxieties have found new forms of expression. The Qianlong 乾隆 reign of the Qing (1735-1796) is regarded as China’s last dynastic Age of Prosperity 盛世. Qianlong, or the Gaozong Emperor (高宗, Aisin Gioro Hung li 愛新覺羅 · 弘曆, 1711-1799), repeatedly expressed concern about the decline in the military prowess of the Manchu-led Bannerman 旗人 forces that had conquered the Ming dynasty only a hundred years before.

Having replaced the Ming, the Manchus policed their territory with garrisons located in major population centres. They colonised the country and created an expanded military empire that was ruled through a combination of Manchu statecraft and Chinese dynastic practice. As the Qing historian Mark Elliott has noted, however, Qianlong was concerned about the gradual decline of the ‘Manchu Way’, Manjusai doro, or the ‘Old Way’ fe doro, one that had championed ‘manly virtue’ hahai erdemu. He was worried that the warrior caste of Bannerman was increasingly adopting the ‘Chinese Way’ or Nikan-i doro, one of luxury, laziness and sybaritic excess, things that were associated with Han people and the defunct Ming. (In England around the same time military aesthetes and coiffed fops were called Macaroni.)

In the nineteenth century, military defeats and dynastic humiliation weakened the Qing ruling house and exacerbated the anxiety both of the rulers and the ruled about China’s overall weakness. As attempts to reform the military were launched during the Tongzhi Restoration of the 1860s-1870s, anti-Qing patriots now decried the Bannerman who had conquered the country over two hundred years earlier for being effete and decadent — the very qualities that the Manchus had once found so repulsive. Although Qing military commanders adopted ideas, training methods and technologies from Germany and a modernising Japan, when the dynasty finally gave way to revolution and a republic was born in 1912, many educators also looked for inspiration to classical exemplars of military prowess, in particular the ancient Greek city-state of Sparta.

In her study of school textbooks in the early modern era (late Qing and early Republic), the historian Bi Yuan 畢苑 devotes a chapter to the significance of Sparta. The warrior city appealed to pedagogues both in the late-Qing period and in particular in the new Republic of China as it placed patriotic fervour and militancy above the culture of refinement and letters associated with its rival Athens. In the radical atmosphere of the early Republic, Sparta and the spirit of militarism featured prominently in school texts. One popular work, published in 1912 and reprinted nine times in three years, extolled Sparta for ‘placing the greatest emphasis on military education’ 厲行嚴重之尚武教育 and claimed that ‘as a result the spirit of patriotism suffused the society’ 故愛國之精神, 上下普及. Zhang Xiang (張相, 1877-1945), a noted poet and linguist who was also compiled the text-book in question, explained that Sparta’s ‘political ideology tended to favour the authoritarian’ 其政治思想頗傾向於專制 and:

Although the politics of Sparta and Athens were diametrically opposed, from the start their views of the state were undifferentiated; both were steadfast in their patriotism. 斯巴達與雅典其政治主義雖全然相反, 至其對於國家之概念, 則初無有異, 而皆饒有愛國之精神。

— 畢苑,《建造常識: 教科書與近代中國文化轉型》2010年, p.192

The influence on Chinese educational thinking of Japanese militarism, which had flourished from before the founding of the Republic, waned after the May Fourth period and a new educational philosophy was introduced. The Renxu System 壬戌學制 (named after the Renxu lunar year of 1922) was based on the American model. For the following decade, warlike Sparta was depicted as a primitive, violent and repressive society. Meanwhile, the Nationalist party-state, which we discussed in The Party Empire, rose to prominence while the opponents of the Nationalists, the Communist Party, a group that was also inspired by the exemplars of Japan, Germany and the Soviet Union, created Sparta-like military camps in its rural guerrilla bases. It was a process that reached an apogee in Yan’an, while for the Nationalists, war with Japan and the military ethos contributed both to the founding of the relatively benign Three People’s Principles Youth Corps 三民主義青年團, and to the creation of the semi-fascist Blue Shirts Society 藍衣社 (also known, among other things, as the China Reconstruction Society 中華復興社). As the nation faced the Japanese enemy, Sparta made a reappearance. A nationally distributed school text produced by Zhonghua Books in 1937 contained a lesson titled ‘National Training in Sparta’ 斯巴達的國民訓練. Eighty years later, Xi Jinping’s Communists could easily endorse the sentiments expressed therein:

Spartans, be they men or women, thought only of their country, never of themselves. That’s why the city of Sparta had no defensive walls. The defences were in their hearts. One could truly say of them that ‘The Will of the People Was as Strong as a Fortress’. 斯巴達人,不論男女,都只知道有國家,不知有個人;所以斯巴達的國都,沒有城堡,他們的愛國心,就是他們的城堡。「眾志成城」這句話,斯巴達人真可以當之無愧!

— 畢苑,《建造常識: 教科書與近代中國文化轉型》, p.198

***

In pre-dynastic and even dynastic China, men of letters were supposed to be adept in the arts of military valour as well as being versed in the ways of rulership. This ideal found expression in such expressions as 能文能武 and 文武雙全.

Macho culture flourishes in various guises, including the rise in popularity of martial arts and ‘Combat Tai Chi’ 戰太極, fantasy war gaming culture, bellicose patriotic videos, as well as the box office success of Hollywood-style pro-PLA films like Wolf Warrior 戰狼 (2015) and the sequel Wolf Warrior 2 戰狼2 (2017). Long before today’s talk of putting ‘steel in the backbone’ and of what Victor Mair dubbed ‘lupine nationalism’, China extolled decades of ruthless education today’s party-state leaders ‘came of age drinking wolf’s milk’ 喝狼奶長大:

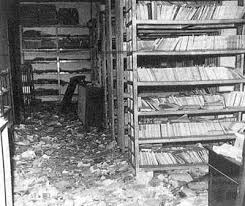

Inculcated with a sense of patriotic ire through their school days, and convinced that the outside world was a malevolent enemy set on subverting China’s revolution, the Red Guards attacked all things foreign during the early months of the Cultural Revolution in 1966. Countless people would lose their lives in the ensuing mêlée, although today very few people will admit to being involved with murder. The US-based academic Rae Yang 楊瑞 is one of a handful of former Red Guards who is candid about her past. She recalls that her teachers were astounded by the visceral fury of the young rebels. Why should they have been so surprised that we acted like wolves, she asks. After all, we had all been fed on a constant diet of wolves’ milk at school. In his article on teaching history in China today [written in 2002], Yuan Weishi 袁偉時 observed with dismay that, ‘Our children are still being fed wolves’ milk!’

— Barmé quoted in Victor Mair

Wolf’s milk, a slime mold attractive to young Chinese?

Language Log, 7 April 2018

As the nation enters its Age of Might, the martial spirit is more important to the party-state than it has been for decades. For that reason, there is a widespread concern about the significance and impact of what could be called ‘Girly China’. The anxiety focusses on the ‘effeminate’ bent of culture, a trend dubbed variously yīnróuhuà 陰柔化 or niánghuà 娘化. It is one in which neither the arts nor physical rigour are as important as fashion sense and makeup. Such terms depict the supposed feminisation of mainstream, that is male-dominant, culture that has developed in tandem with the burgeoning popularity of Xiǎoxiānròu 小鮮肉, literally ‘Little Fresh Meat’. These ‘Tasty Twinks’, as I call them, or adolescent metrosexuals are a cotillion of dancing, singing and performing pretty boy-celebrities with an ardent fan base. We have previously encountered such Twinks in the laughably named, yet wildly popular, group ‘The Fighting Boys’ 加油男孩, an androgynous threesome also known as TFBoys.

‘Little Fresh Meat’ might be a recent online expression, but the bewitching lure of counter-hypermasculine beauty is hardly a modern commercial invention. Delicate and artistic male types have complex histories in East Asia related to the performing arts. However, in contemporary China where militarisation is, once again, becoming a predominant theme of official culture, concerns are being voiced about the degrading of machismo 男性氣質, the proliferation of males who are deemed to be epicene 不男不女 and effeminate men 娘炮 and dandies who simper and speak in ‘girly way’ 娘娘腔.

One widely circulated report published in the military media in early September put things in the following way:

As Tasty Twinks have become popular in the entertainment world the feminised style has become fashionable among young people, and this influences the kinds of idols people look up to. Many people are worried that treating ‘Girly China’ as a legitimate aesthetic will impact negatively on our youth. Moreover, it will undermine the virility and vitality of Our Nation and Our Race. Such concerns require dispassionate observation, as well as serious attention. 當「小鮮肉」走紅娛樂圈,陰柔之風漸漸影響到青少年的審美追求和偶像選擇時,許多人擔心以「娘化」為美的審美觀,會對青少年造成負面影響,進而銷蝕整個國家和民族的陽剛、血性之氣。這樣的憂慮,既要冷靜看待,也需認真關注。

— 錢宗陽, 中國少年,陽剛之氣不可消,

中國國防報, 7 September 2018

In an article centering on the debate about China’s feminisation published by People’s Daily in mid August 2018, Deng Xiquan 鄧希泉, the head of the Youth Research Centre 中國青少年研究中心青年研究所所長 observed phlegmatically that, in the pluralist cultural environment of a newly enriched society, phenomena such as the ‘softening of culture’ 陰柔文化 was normal, and it did not necessarily constitute the mainstream. ‘Overall,’ Deng opined, ‘young people are constantly improving in terms of physical stature and strength, fitness as well as their sense of responsibility and ability to carry out the mission [of realising The China Dream].’ 從整體看,當代青年的身型、體質、健康行為、責任意識、擔當能力均在不斷優化。

When most countries reach a particular stage of development, one in which white collar workers and intellectuals occupy a privileged position, a kind of ‘femininised cultural softening’ 陰柔之風 occurs. At the same time, it is also evident that the ‘soft culture’ prevalent among South Korean and Japanese celebrities, as well as the ambience of Japanese manga culture, is exerting a powerful influence in China. 絕大多數發達國家在經濟發展進入發達程度後,社會結構中的白領階層和知識分子處於優勢地位,「陰柔之風」會逐漸增長。同時,「陰柔之風」濃郁的韓國明星、日本明星、日本動漫及其文化氛圍對我國的影響很大。

The article also quoted Zhang Yongjun 張勇軍, a marriage counsellor with over ten years’ experience. Zhang observed that parents sacrificed so much for their children, and teachers were so careful with their charges, that there was a general hesitance about exposing young people to physically demanding training, risks, pressure or generally challenging situations:

Objectively speaking this state of affairs encourages softness. And that’s not to mention the hormones and additives found in food and beverages that may well also be contributing to the feminisation of boys and young men. 客觀上也助長了他們陰柔性格的形成。同時,當前一些飲食中含有添加劑、抗生素,一定程度上可能造成一些男孩在生理上偏向陰柔狀態。…

The reporter then reworks the famous line from Liang Qichao’s ‘Paean to Youthful China’ quoted above — ‘If the youth are strong, the country will be strong’ 少年強則國強 — to read, 少年娘則中國娘, ‘If the youth are feminine then the country will be effeminate’. The marriage counsellor Zhang Yongjun is critical of such male-centric views and points out in a society that promotes equality of the sexes it is only normal that there should be an evolution in gender stereotypes. He also comments that the ‘transvaluation’ or revamping of traditional values contributes significantly to contemporary social mores. ‘How to encourage “manliness” 陽剛之氣 among children is a major challenge for the society’ 增加孩子的‘陽剛之氣’是社會的大功課, Zhang admits and he suggests that in searching for answers families and educators could do no better than excavate China’s outstanding cultural traditions:

In ancient times, the education of the literati emphasised both literary and martial accomplishments. They were taught poetry, history, ritual practice and music and cultivated to appreciate the unity of heaven and humankind. Moreover, boys need to be inspired in their education to be manly, to develop a robust mental attitude and a sense of expansive righteousness and that can be better achieved by teaching them about such things the achievements of the heroes of The China Race, as well as the sacrifices of martyrs and the outstanding inventions of the past. 在古時,士人培育都是文武雙全、詩書禮樂齊備,注重培養天人合一等思想文化。」同時,教育內容應多一些中華民族英雄事跡、烈士事跡、優秀髮明創造等,激發孩子的陽剛之氣、生命鬥志、浩然正氣等。

All the while, Zhang warns: we must be wary of the corrupting influence of entertainment culture, especially among the young:

The media should promote more stories about the responsibilities people have in life and in regard to their families and the nation. In that way they will be encouraged to find the wellsprings of uplifting positive energy in themselves. 媒體應多向人們宣傳人生責任、家國責任,讓人們從內心迸發出積極上進的正能量。

— 彭訓文, 「陰柔之風」盛行是喜是憂引爭論 社會需要啥樣的性別氣質,

People’s Daily (Overseas Edition), 13 August 2018

***

Writing in China National Defence Daily 中國國防報, the army journalist Qian Zongyang 錢宗陽 expressed more immediate, and practical, concerns:

Right now [September 2018] is the army’s recruitment season as well as being the time for the military training of students [軍訓 short for 軍事訓練]. In recent years, the following phenomena have been commonplace: some young people don’t want to enlist, or if they join up they quit when faced with the rigours of training. Some students can’t even cope with mandatory military training at school; they suffer from heatstroke as soon as they are exposed to the sun, or take sick leave every few days. Then there’s the parents who express views such as: ‘Our children are here to study, not for military training’; and, ‘My kids can’t be made to suffer like this; let other families provide the soldiers’. 眼下正值徵兵季、學生軍訓季,從近年來的情況看,不乏這樣的現象:有的青年不願意參軍入伍、入伍後吃不了苦打退堂鼓;有的青少年受不了學校的軍訓,太陽一曬就中暑、三天兩頭泡病號;還有一些家長認為,「孩子是來上學的,不是來軍訓的」「別人的孩子當兵可以,我家的孩子不能去吃這個苦」。

We need an inclusive attitude: every society requires a spiritual backbone. History repeatedly warns us — from the defeats suffered by the Roman nobility due to their indulgent and luxurious lifestyle, to the decline of the Qing Bannerman as a result of their obsessive pursuit of cultural refinement — one must never abandon the Martial Spirit or Masculine Virility. Our young people are not only the hope for their families, they are the future of the State and Our Race. As they reach maturity they may well enjoy the company of entertainment celebrities, but they need spiritual guides: among them, of course, there must be military heroes brimming with Masculine Virility who have sacrificed themselves for the Nation. 社會需要包容,但任何一個社會、一個個體都需要精神脊梁。從古羅馬貴族崇尚奢華享樂後的衰敗,到八旗子弟玩物喪志後的墮落,歷史一再告誡人們,尚武精神和血性陽剛之氣不能丟失。青少年是家庭的希望,也是國家和民族的未來,在他們的成長之路上,可以有娛樂明星作伴,但更需要精神偶像引領。其中,以身許國、血性陽剛的軍人自然不可缺席。

A nation needs young people with daring and guts. A person’s aesthetic sensibility is an expression of their values, and it will influence the spiritual underpinnings of one’s personality. While paying due attention to personal appearance what is even more important is focussing on the cultivation of the individual, their mental world and their sense of purpose. We must lead them to develop a sense of nationhood and to accept their social responsibilities. We must encourage them to confront difficulties and face setbacks for these can temper the soul and forge an undaunted and virile spirit. 青年有血性民族才有希望。審美追求反映價值追求,也必將深刻影響人的精神品質。在注重外在形象塑造的同時,我們應更注重青少年內在涵養、精神境界和意志品質的培養,引導他們培塑家國情懷、承擔社會責任;鼓勵他們直面困難挫折,焠鍊勇敢堅毅的品格、血性陽剛的氣魄。

It’s September and groups of young people are marching into camps to start a period of military training. While attention is taken up by denunciations and arguments over ‘Girly China’, you should spare some thought for, and offer your support to, the military camps and the training that they provide. For they are fostering and egging on China’s New Generation of Militants. 時值9月,一批青年正步入軍營、走上軍訓場。在矚目關於「陰柔化」的批判和爭論之余,不妨對軍營和軍訓多一些關注支持,為正在加鋼淬火的軍營新生代們點贊加油。

— 錢宗陽, 中國少年,陽剛之氣不可消, 中國國防報, 7 September 2018

(Note: For a corrective to the all of this ‘yin-yang reductionism’, watch Natalie Wynn (‘Oscar Wilde on YouTube’) discuss gender stereotypes on ContraPoints. — Ed.)

***

In an earlier era, the concerns of people like Zhang Yongjun and the army journalist Qian Zongyang were widely shared. For the founding generation of the People’s Republic — men and women who had fought bloody wars for their cause — the effort to maintain the impetus of the revolutionary enterprise was not merely a matter of education, it was central to the survival and success of China itself. There was an urgency about the desire to channel youthful energy and enthusiasm for the sake of the cause. Adolescent wilfulness, creativity and idealism had to be harnessed. At times, some headstrong young people, inspired by the Party’s calls to study Marxism-Leninism, mistakenly acted on their own volition to champion social equality and workers rights. In the late 1960s, some independently minded Red Guards gave in to such heterodoxy, as did the authors of the Li Yizhe Big-character Poster in 1974. In 1989, there were among student and worker protesters those who also had the wrong idea about collective rights, as did new Marxist study groups that appeared at universities in the early 1990s. In the late 1990s, a neo-Marxist celebrity intellectual made a show of supporting workers in Yangzhou, and his clutch of ‘New Left’ academics offered fawning support to Bo Xilai at the height of the popularity of the ‘Chongqing Model’ in 2010-2012 because of his supposed pro-worker Marxist credentials. And again, in 2018, some mistakenly idealistic young Communists at Peking University and other tertiary institutions took it upon themselves to pursue an independent, Marxist-inspired critique of the status quo and supported free workers’ unions. Like previous generations, they soon discovered that the Leader’s Will is the ultimate, and only legitimate, reflection of the mind of the Party, the nation and the army. There is no room for self-indulgent, adolescent arrogance.

In both Homo Xinensis and Homo Xinensis Ascendant, we have discussed the long history of national transformation and educational renewal that are of such importance both to the dominant Chinese intelligentsia and to the Communist Party (and, previously, to the Nationalist Party when it ruled the Mainland). The man who most clearly articulated the anxieties related to China’s past weakness, and formulated political strategies to address those anxieties, was one of the founders of the Chinese Communist Party, Mao Zedong.

Be Militant!

要武嘛!

A revolution is not a dinner party, or writing an essay, or painting a picture, or doing embroidery; it cannot be so refined, so leisurely and gentle, so temperate, kind, courteous, restrained and magnanimous. A revolution is an insurrection, an act of violence by which one class overthrows another. 革命不是請客吃飯,不是做文章,不是繪畫繡花,不能那樣雅致,那樣從容不迫,「文質彬彬」,那樣「溫良恭儉讓」。革命就是暴動,是一個階級推翻一個階級的暴烈的行動。

— Mao Zedong, Report on an Investigation of the

Peasant Movement in Hunan, March 1927, official translation

***

***

On 18 August 1966, Mao and his fellow Party leaders attended a million-person mass rally in Tiananmen Square. They encouraged newly formed groups of rebellious students who called themselves Red Guards to rise up against the existing party-state order. They told the amassed young people that their struggle would contribute to a Chinese-led world revolution, one that would overturn the Western status quo.

In what became an iconic, and fateful, exchange on that day, Song Binbin (宋彬彬, 1947-) — a Red Guard leader and member of the Communist elite (she was the daughter of Song Renqiong (宋任窮, 1909-2005), a Long March-era general charged with developing the country’s nuclear weapons — presented Mao with a Red Guard armband. Mao asked her name and, when Song told him that it was Song Binbin, he said: ‘Is that Binbin as in “temperate” [used in Confucius’s Analects]?’ 是文質彬彬的彬嗎? When she replied in the affirmative, the Chairman famously said:

You should want to be militant!

要武嘛!

A few days later an article titled ‘I Put a Red Armband on Chairman Mao’ 我給毛主席戴上了紅袖章 signed ‘Song Yaowu’ 宋要武 [Be Militant] (Song Binbin 宋彬彬) appeared in the press. Song later claimed that both the article and the name change were a fabrication, but the essay and the image of her and Mao on the rostrum of Tiananmen are regarded as contributing to ‘Bloody August’ 紅八月, a month when school students throughout the country went on a violent rampage against teachers and all kinds of authority figures.

The Red Guard rally of 18 August 1966 during which Lin Biao, Mao’s military champion, called for rebels to obliterate the past and ‘Destroy the Four Olds’ 破四舊, marked a renewed era of ‘armed struggle’ 武鬥 in China. Political enemies and scapegoats who, until then had mostly been denounced in written and spoken attacks, what was called ‘literary struggle’ 文鬥, were now subjected to beatings, torture and worse. Apart from personal political hubris and ambition, Mao’s aim was to create an atmosphere of civil conflict during which Revolutionary Successors (a topic addressed in Homo Xinensis Ascendant) would be tempered by war and prove themselves worthy of the mantle of future leadership.

(Note: In an interview for the 2003 documentary film Morning Sun , of which I was a co-director and co-writer, Song publicly proclaimed herself to be innocent both of writing the article and involvement in student violence, in particular the persecution and death of her school principal Bian Zhongyun (卞仲耘, 1916-1966). In 2014, Song reportedly made a public apology at her old school, but Bian Zhongyun’s ninety-three-year-old husband, Wang Jingyao (王晶垚, 1921-), rejected the gesture. — Ed.)

***

Mao Zedong himself was one of the countless young people, men and women, who had responded to the exhortations of thinkers and agitators like Liang Qichao in the early twentieth century.

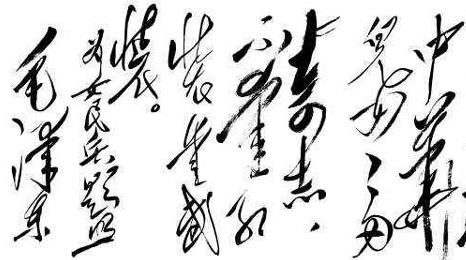

On the eve of the celebration of the 120th anniversary of Mao’s birth, 24 December 2013, the official media reminded Party members and cadres of his militant spirit. In an article titled ‘Thoughts Inspired by a Quotation from Chairman Mao’ 一句「毛主席語錄」引發的思考 the author told the faithful that they needed ‘more calcium’ 補鈣 to strengthen their backbones and that they should ‘recharge batteries’ 充電 depleted by an era of laziness and luxury. ‘It is the right time to reacquaint yourselves with some Red Classics’ 紅色經典, the writer said, in particular people should mull over a famous inscription that Mao Zedong wrote for himself in 1917:

Struggle: A Reminder to Myself

奮鬥自勉

Find boundless joy in the struggle with Heaven;

Find boundless joy in the struggle with Earth;

Boundless too the joy you’ll find in Human Strife.

與天奮鬥,其樂無窮;

與地奮鬥,其樂無窮;

與人奮鬥,其樂無窮。

Today, Party commentators prefer to interpret the last line of this exhortation to mean that one should unite with one’s comrades to pursue the struggle for the Party’s enterprise. But Mao’s life was often anything but that and he gloried in the wars he waged with his opponents, both real and imagined, whether they were outside or inside the Communist Party. Today, despite a constant refrain about social harmony and peace, the Communist Party remains a political organisation founded on and engaged in ceaseless travails 奮鬥 and conflict 鬥爭.

***

In April 1917, La Jeunesse 新青年, the leading cultural and political journal of the day, published an article by a writer signing himself ‘Mr Twenty-eight Strokes’ 二十八畫先生. There were twenty-eight brush-strokes in the name Mao Zedong 毛澤東 and in A Study of Physical Education 體育之研究 the twenty-four year old author extolled the need for the rigorous training of the bodies 體, as well as the inculcation of morality 德 and knowledge 智, of the nation’s youth:

Our nation is wanting in strength; the military spirit has not been encouraged. The physical condition of our people deteriorates daily. These are extremely disturbing phenomena. Those who promote [physical education] have not grasped the essence of the problem. Consequently their efforts, though prolonged, have proved ineffectual. If they refuse to change, the process of weakening will be aggravated. To attain our goals and exercise far-reaching influence is an external matter, an effect. The development of our bodily strength is an internal matter, a cause. If our bodies are not strong, we will tremble at the sight of [enemy] soldiers. How then can we attain our goals, or exercise far-reaching influence?… 國力苶弱,武風不振,民族之體質,日趨輕細。此甚可憂之現象也。提倡之者,不得其本,久而無效。長是不改,弱且加甚。夫命中致遠,外部之事,結果之事也。體力充實,內部之事,原因之事也。體不堅實,則見兵而畏之,何有於命中,何有於致遠?…

The superior man’s deportment is cultivated and agreeable, but one cannot say this about exercise. Exercise should be savage and rude. To be able to leap on horseback and to shoot at the same time; to go from battle to battle; to shake the mountains by one’ s cries, and the colours of the sky by one’s roars of anger; to have the strength to uproot mountains like Xiang Yu and the audacity to pierce the mark like You Ji — all this is savage and rude and has nothing to do with delicacy. In order to progress in exercise, one must be savage. If one is savage, one will have great vigour and strong muscles and bones. The method of exercise should be rude; then one can apply oneself seriously and it will be easy to exercise. These two things are especially important for beginners. 文明柔順,君子之容。雖然,非所以語於運動也。運動宜蠻拙。騎突槍鳴十蕩十決,暗惡頹山嶽、叱吒變風雲,力拔項王之山,勇貫由基之札,其道蓋存乎蠻拙,而無與於纖巧之事。運動之進取宜蠻,蠻則氣力雄,筋骨勁。運動之方法宜拙,拙則資守實,練習易。二者在初行運動之人為尤要。

Two years later, shortly after the May Fourth demonstrations of 1919, and on the eve of the founding of the Communist Party, Mao’s ideas about what a strong renewed nation could achieve were further crystalised, and they still resonate today, a century later:

As a result of the world war and the bitterness of their lives, the popular masses in many countries have suddenly undertaken all sorts of action. In Russia, they have overthrown the aristocrats and driven out the rich… The army of the red flag swarms over the East and the West, sweeping away numerous enemies… The whole world has been shaken by it…. Within the area enclosed by the Great Wall and the China Sea, the May Fourth Movement has arisen. Its banner has advanced southward, across the Yellow River to the Yangtze. From Guangzhou to Hankou, many real-life dramas have been performed; from Lake Dongting to the Min River the tide is rising. Heaven and earth are aroused, the traitors and the wicked are put to flight. Ha! We know it! We are awakened! The world is ours, the nation is ours, society is ours. If we do not speak, who will speak? If we do not act, who will act? If we do not rise up and fight, who will rise up and fight? … 世界戰爭的結果,各國的民眾,為著生活痛苦問題,突然起了許多活動,俄羅斯打倒貴族,驅逐富人,… 紅旗軍東施西突,掃蕩了多少敵人 … 全世界為之震動。… 更有中華長城渤海之間,發生了五四運動。旌旗南向,過黃河而到長江,黃埔漢皋,屢演活劇洞庭閩水,更起高潮。天地為之昭蘇,奸邪為之辟易。咳!我們知道了!我們醒覺了!天下者我們的天下。國家者我們的國家。社會者我們的社會。我們不說,誰說?我們不幹,誰幹?

— 毛澤東, 民眾大聯合, 湘江評論, 1917年7-8月

From his early student days, Mao had evinced a particular fascination for the militant reformers and rulers in Chinese history, the most significant being Shang Yang (商鞅, or Lord Shang, 390-338BCE) and the First Emperor of the Qin dynasty (秦始皇, 259-210BCE). One of his first essays, written in 1912, extolled the achievements of Lord Shang 商君, a man whose draconian reforms enabled the rise of the State of Qin and the creation of China’s first unified empire. When in power himself, Mao elevated the status of Lord Shang and the Qin Emperor, men who had been derided through the ages for their brutality. But this is a topic for another Lesson in New Sinology.

***

Mao not only wrote essays for his fellow progressives, he also expressed his ideas in classical-style poems which, when they were published from the 1950s, had a profound influence on the creation of kind of militant romanticism that remains a feature of Chinese political and martial culture today. As Stuart Schram, the authority on Mao’s writings observed, ‘military metaphors and military habits of thought permeate every aspect of Mao’s mentality and his approach to virtually all problems’ (see Stuart Schram, ‘The Military Deviation of Mao Tse-tung’, Problems of Communism 1, (1964): 52-53). This aspect of the Maoist tradition casts a long shadow over contemporary China.

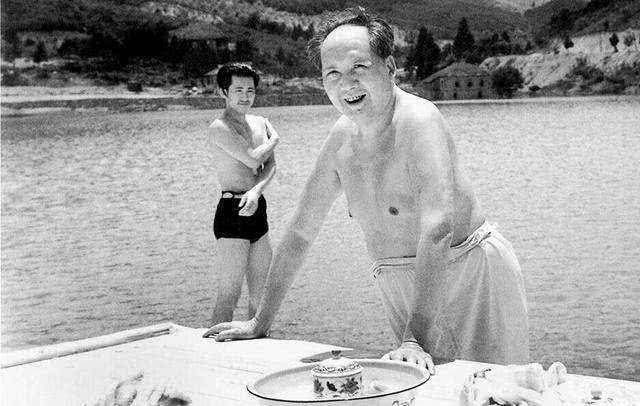

We have previously discussed the importance of Mao’s 1935 poem ‘Snow — to the tune of Qinyuan Chun’ (see Ruling the Rivers & Mountains). An earlier work, ‘Changsha’, named after the Hunan provincial capital where Mao studied, and swam, is written in the same poetic metre. It reflects not only the author’s youthful hubris, it creates a metaphorical landscape that would suffuse party-state culture. Here, again, we encounter the politicised ‘Rivers and Mountains; 江山 that feature in the first part of ‘Drop Your Pants!’ The writer also poses the question ‘Who rules over man’s destiny?’ 誰主沈浮, an expression employed both by the supporters of and opponents to China’s Communist Party.

Changsha

— to the tune of Qinyuan Chun

沁園春 · 長沙

1925

Alone I stand in the autumn cold

On the tip of Orange Island,

The Hsiang flowing northward;

I see a thousand hills crimsoned through

By their serried woods deep-dyed,

And a hundred barges vying

Over crystal blue waters.

Eagles cleave the air,

Fish glide in the limpid deep;

Under freezing skies a million creatures

contend in freedom.

Brooding over this immensity,

I ask, on this boundless land

Who rules over man’s destiny?

I was here with a throng of companions,

Vivid yet those crowded months and years.

Young we were, schoolmates,

At life’s full flowering;

Filled with student enthusiasm

Boldly we cast all restraints aside.

Pointing to our mountains and rivers,

Setting people afire with our words,

We counted the mighty no more than muck.

Remember still

How, venturing midstream, we struck the waters

And waves stayed the speeding boats?

獨立寒秋,

湘江北去,

橘子洲頭。

看萬山紅遍,

層林盡染;

漫江碧透,

百舸爭流。

鷹擊長空,

魚翔淺底,

萬類霜天競自由。

悵寥廓,

問蒼茫大地,

誰主沈浮?

攜來百侶曾游,

憶往昔崢嶸歲月稠。

恰同學少年,

風華正茂;

書生意氣,

揮斥方遒。

指點江山,

激揚文字,

糞土當年萬戶侯。

曾記否,

到中流擊水,

浪遏飛舟!

— official Foreign Languages Press translation

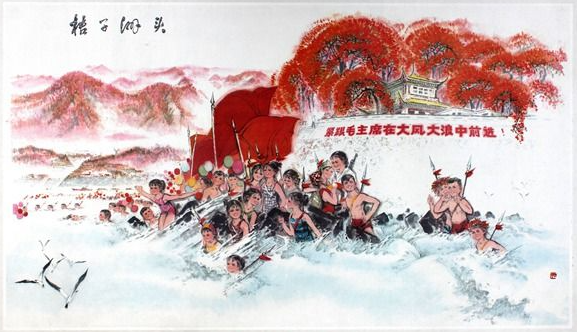

Physical prowess would continue to feature in Mao’s life and doctrines, and his penchant for swimming was famous. One of his residences in the party-state compound at Zhongnanhai in Beijing was next to the old swimming pool dating from the Republican era when the former imperial Lake Palaces were open to the public. In 1966, following his sudden public reappearance and a swim in the Yangtze, one during which he more or less floated downstream within a penumbra of bodyguards, his former secretary and lead propagandist Chen Boda published an editorial in People’s Daily titled ‘Follow Chairman Mao and Advance through Winds and Waves’ 跟著毛主席在大風大浪中前進 (26 July 1966). Mao’s ‘heroic’ feat at the start of his civil war-like Cultural Revolution would be celebrated every year by aquatic events until his death ten years later.

***

Swimming

— to the tune of Shuidiao getou

水調歌頭 · 游泳

June 1956

I have just drunk the waters of Changsha

And come to eat the fish of Wuchang.

Now I am swimming across the great Yangtze,

Looking afar to the open sky of Chu.

Let the wind blow and waves beat,

Better far than idly strolling in a courtyard.

Today I am at ease.

It was by a stream that the Master said —

‘Thus do things flow away! ’

Sails move with the wind.

Tortoise and Snake are still.

Great plans are afoot:

A bridge will fly to span the north and south,

Turning a deep chasm into a thoroughfare;

Walls of stone will stand upstream to the west

To hold back Wushan’s clouds and rain

Till a smooth lake rises in the narrow gorges.

The mountain goddess if she is still there

Will marvel at a world so changed.

才飲長沙水,

又食武昌魚。

萬里長江橫渡,

極目楚天舒。

不管風吹浪打,

勝似閒庭信步,

今日得寬餘。

子在川上曰:

逝者如斯夫!

風檣動,

龜蛇靜,

起宏圖。

一橋飛架南北,

天塹變通途。

更立西江石壁,

截斷巫山雲雨,

高峽出平湖。

神女應無恙,

當今世界殊。

— official Foreign Languages Press translation

Mao composed this song-lyric following three swims in the Yangtze at Wuhan in June 1956. It was published the following January only months before the crushing of the Hundred Flowers Movement in the build up to the cataclysm of the Great Leap Forward. He said ‘Let the wind blow and waves beat,/ Better far than idly strolling in a courtyard.’ In fact, it was the last moment that the People’s Republic under Mao enjoyed anything remotely resembling peace.

The American journalist, women’s rights activist and spy Agnes Smedley (1892-1950) described meeting Mao Zedong in Yan’an in 1937:

The tall, forbidding figure lumbered toward us and a high pitched voice greeted us. Then two hands grasped mine; they were as long and sensitive as a woman’s. Without speaking, we stared at each other. His dark, inscrutable face was long, the forehead broad and high, the mouth feminine. Whatever else he might be he was an aesthete. I was in fact repelled by the feminine in him and by the gloom of the setting. An instinctive hostility sprang up inside me, and I became so occupied with trying to master it, that I heard hardly a word of what followed. …

***

Militant Talk

[T]he social standing of the military fluctuated in the course of Chinese history. During the Zhou, archery, charioteering, and horse riding were key elements of a nobleman’s training. The abilities to fight and to lead men in battle were highly esteemed. Under the empire, the prestige of the military among the classically educated elite declined, especially during and after the Song. However, by that time, military terms (軍語, short for 軍事術語) had become embedded in the general vocabulary. Today, the process has continued so far that their military origin has been all but forgotten.

Influence of Military Vocabulary

Note: The original word (in parentheses) was exclusively military.

- jiaoshi 教師, teacher (general)

- qianwei 前衛, avant-garde (vanguard)

- guanjun 冠軍, victor in sports (at the head of an army)

- xian 弦, chord; hypotenuse (bowstring)

- hu 弧, arc [in geometry] (bow)

- loujian 漏箭 (clepsydra arrow)

- huojian 火箭, space rocket (fire-arrow)

- daji 大戟, spurge [in botany] (halberd)

- feng 鋒, front [in meteorology] (cutting edge of a sword)

- jie 戒, fast [in religion] (to guard)

- dianzhen 點陣, lattice [in physics] (zhen 陣, battle array)

- lei 壘, build; base, as in first base (rampart)

- xiagang 下崗, lose one’s job (go off sentry duty)

- jianmei 劍眉, dashing eyebrows (sword-like eyebrows)

At least 15 percent of the total stock of four-character expressions 成語 in Chinese are of military origin. The Sunzi bingfa 孫子兵法 alone has contributed 20 popular sayings to the language, the most famous of which is, “Only by knowing the enemy and by knowing yourself can you guarantee victory.” 知彼知己,百戰不殆.

As another indication of the influence of the military, note the popularity of literature with military themes.

Note also that at times of war against a non-Chinese enemy it was a common practice for parents to give their sons military names. It began in the Han, during the long wars against the Xiongnu, when names such as Pohu 破胡 (Smash the Xiongnu), were popular and it continued, on and off, until the twentieth century.

Explicit military language received a boost during the 1950s. The most immediate and often only experience of management and organization of the new civilian administrators and government leaders was in organizing the CCP to fight. Thus, phrases like “work station” 工作崗位 for local assignment, “staging an offensive” 發起進攻 for tackling a problem, or “frontlines” 前線 for a difficult job, entered the general vocabulary. Class war was continuously in the air, and during campaigns such as the Great Leap Forward, military language thrust aside less direct ways of saying things. Again, from the very start of the Cultural Revolution (1966-76), “Red Guards” 紅衛兵 made military language an integral part of their nomenclature and rhetoric. Shortly after the start of the movement in August 1966, Mao himself had urged them to “bombard the headquarters” 炮打司令部. Already in 1963, they had been told to emulate (Corporal) Lei Feng 雷鋒, and the nation had been urged to learn from the PLA in 1965.

Another sphere entirely in which the military influenced civilian life is in sports.

— from Endymion Wilkinson

Chinese History: A New Manual

Fifth Edition, 2017, pp.347-348

As we have noted in New China Newspeak, mainland Chinese bristles with aggression. (I would add that, when I studied at Maoist universities as an exchange student in the late-cultural Revolution our classmates, who were called ‘Worker-Peasant-Soldier Study Officers’ 工農兵學員 not students, were constantly working on ‘Fighting Tasks’ 戰鬥任務, or what in common parlance were ‘written assignments for class’). The official language of the People’s Republic has never been demobbed.

Early in the Xi Jinping era, it was evident that official rhetoric was reflecting his style of ‘moral re-armament’. Following the local propaganda department’s attack on Southern Weekly 南方週末, a semi-independent media outlet in Guangdong, for promoting ‘constitutionalism’ in early 2013, the authorities reformulated old ideas in a way that reflected the tenor of the new age. Now the Party was openly engaged in ‘Opinion Warfare’ 輿論鬥爭, propagandists were told that they had to ‘dare to reveal the dagger’ [of hardline ideology] 敢於亮劍 and their operations must ‘occupy the Triangle Hill of the Internet’ 佔領網絡輿論上甘嶺 [the 1952 Battle for Triangle Hill 上甘嶺戰役 was a famous campaign in the Korean War]. Overall, they Party had to ‘win victory in the three-decade-long counterattack in the realm of ideology’ 打贏新三十年的意識形態反擊戰 and, in February 2016, Xi Jinping summed it up by declaring that, henceforth (and actually once more), China’s Party media only answered to one name ‘The Party’ 黨媒姓黨.

Today, the party-state stridently expresses itself in terms of struggles, campaigns, battles, military tasks and strategies. Just as the Communists have been at war, and prosecuting campaigns, since they founded their political party, their language has also always been on a military footing. Policies are often spoken of as being ‘launched as an assault on entrenched positions’ 攻堅 aimed at ‘decisive victory’ 決戰. After all, as the People’s Daily editorial published to commemorate the 1st of October 2018 National Day titled The Great Enterprise Will Be the Result of Struggle 用奮鬥成就復興偉業 put it:

Happiness and Good Fortune are born of Struggle; Struggle is arduous and long-term. 幸福都是奮鬥出來的,奮鬥也是艱辛的、長期的。…

All great achievements are the result of continuous exploration and endless struggle. A great enterprise requires continuity over time and progress towards the future. We have traversed countless mountains and forged numerous rivers, but we must conquer new waters and more mountains. Although to date we have battled and conquered innumerable obstacles, still we must constantly be on the offensive and overcome difficulties. 一切偉大的成就都是接力探索、接續奮鬥的結果,一切偉大的事業都需要在承前啓後、繼往開來中推進。雖然我們已走過萬水千山,但仍需要不斷涉水跋山;雖然我們已戰勝重重困難,但仍需要不斷攻堅克難。

In the same vein, in his 2018 New Year’s Message, Xi Jinping reiterated the word that had been central to the political activities of Mao Zedong, one that remains at the heart of the Communist philosophy, ‘struggle’ 奮鬥:

The broad masses of our people are steadfast in their patriotic contributions, they do so without rancour or regret. Let us not forget that it is the innumerable numbers of average people who are truly great. As we congratulate ourselves on our fortune let us never forget that it has come from struggle. 廣大人民群眾堅持愛國奉獻,無怨無悔,讓我感到千千萬萬普通人最偉大,同時讓我感到幸福都是奮鬥出來的。

The following month, when marking the traditional Chinese Lunar New Year, Xi gave a speech in which he used employed the word ‘struggle’ 奮鬥 no fewer than twenty-two times.

In 1966, the architect of Mao’s personality cult, Lin Biao declared that it was necessary ‘to arm the minds of the people of the whole country with Mao Zedong Thought’ 用毛澤東思想武裝全國人民的頭腦; now, the Chinese are told they must ‘be armed with Xi Jinping Thought for the New Epoch of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics’ 用習近平新時代中國特色社會主義思想武裝頭腦. Half a century ago, Lin Biao likened Mao Thought to a ‘spiritual atom bomb of unparalleled power’ 威力無比的精神原子彈; only time will tell what earth-shattering capabilities will be claimed for Xi Jinping Thought.

***

Prepare for War!

備戰

In 1966, Mao Zedong played on the anxieties of their comrades to help launch the Cultural Revolution. Before it became China’s own civil war of all against all, Mao, with the backing of army head Lin Biao, spoke of the looming possibility of war, be it with the Soviet Union or the West. The threat, however, came not only from the outside. The Chairman declared that if the Communist Party was taken over by Soviet-style revisionists who abandoned his revolutionary vision, he would go into the mountains as he had three decades earlier and launch a guerrilla campaign against Beijing.

Addressing an expanded meeting of the Party’s Politburo on 18 May 1966, Lin Biao gave a famous speech that was later mocked as his ‘Classic of Coups’ 政變經 (although it was actually more of a ‘Counter-coup Classic’ 防政變經). In his wisdom, the Chairman had been taking measures to ensure his military control over Beijing, the state broadcasting service and the police. ‘The greatest danger we face’ 這裡最大的問題, Lin declared, ‘is the need to prevent a counter-revolution, an insurgence, a coup d’état [kǔdiédá] 是防止反革命政變,防止顛覆,防止‘苦迭打’. Before going on to list the most famous coups in Chinese history Lin hinted at dark plots:

Of late, our suspicions have increased due to the numerous strange things that have been happening, of odd goings-on. A counter-revolutionary coup is possible. People would be killed, political power would be seized. They would carry out a restoration of the bourgeoisie and socialism would be abandoned. 最近有很多鬼事,鬼現象,要引起注意。可能發生反革命政變,要殺人,要篡奪政權,要搞資產階級復辟,要把社會主義這一套搞掉。

After engineering what was in effect a coup against the party-state in 1966, five years later, in September 1971, Lin himself would go down in flames amidst talk of a failed attempt to overthrow Mao. And five years after that, following Mao’s own death in September 1976, the heads of the army successfully carried out a coup d’état to bring an end to the Cultural Revolution. Over the following years, according to the Chinese Party’s view, the reputation of the People’s Liberation Army was further enhanced after a bloody skirmish with Vietnam and with the reintroduction of military ranks, new uniforms and a budget that allowed the forces to modernise. (More objective analysts argue that, militarily at least, the Sino-Vietnamese clash went badly for Beijing.) In 1984, the forces were the centerpiece of a National Day parade held both to mark the thirty-fifth anniversary of the People’s Republic and to celebrate Deng Xiaoping’s eightieth birthday. Even members of the new cinematic avant-garde helped burnish the image of the military: in 1986, Chen Kaige (陳凱歌, 1952-), an internationally renowned Fifth Generation film-maker, released Soul of the Nation (國魂, later renamed The Big Parade 大閱兵). Filmed by Zhang Yimou (張藝謀, 1950-), it was supposed to be an exploration of the collective and the individual, but it only managed to contribute further to the ‘revolutionary romantic’ aura of a fighting force that has not seen action (except against its own people in Tibet, Xinjiang and Beijing) for nigh on forty years.

A little over a decade later, Deng Xiaoping and his fellow Party elders, believed that the mass student-led protests of April-June 1989 were an insurgency manipulated by inimical forces wanting to unseat the Communist Party. It would be argued that the nominal head of the Party, Zhao Ziyang, was contemplating a coup d’état. The premier, Li Peng, when announcing that Beijing was being put under martial law on 19 May, said unless the army moved on the city and crushed the protests

a People’s Republic was founded only after decades of armed struggle and its achievements possible only because of the fresh blood of countless millions of of revolutionary martyrs will be forfeited 要把幾十年戰爭奪得的人民共和國,成千上萬革命烈士的鮮血換來的成果統統毀於一旦。

Military sacrifice, blood and martyrdom underpinned the Party’s efforts to re-educate China’s young people, and through hyper-patriotic indoctrination among up-coming school children it hoped to train future generations in ways that would prevent further disturbances. Apart from teaching materials, films, songs and patriotic education activities aimed at instilling pro-Party, pro-army ideas of loyalty and service in the young — a strategy formalised in 1994 — over time, Mao-era policies of war preparedness were revived and implemented through a series of laws and training initiatives.

***

In April 2001, a National Defence Education Law 國防教育法 was approved requiring all citizens from primary school onwards to undergo military education. The program was expanded in February 2010 with the announcement of a National Defence Mobilisation Law 國防動員法. Devised by the People’s Liberation Army in coordination with the Ministry of Education defence education was aimed at raising awareness of military preparedness as a major element of Chinese life. In particular, it promoted the ‘spirit of national defence’ (a modern-day version of the century-old advocacy of 尚武精神) and practical military training. The policy was further elaborated by means of a National Defence Mobilisation Committee 國防動員委員會 that, in 2006, announced its ‘Outline Plan for Nationwide Defence Education’ 全民國防教育大綱. The plan called for students to be taught:

- Theory: the evolution of Chinese military theory from Marxism-Leninism through to today with a special emphasis on the theory of information warfare

- Defense Knowledge: the study of China’s geopolitical territory and airspace and related issues

- Defense History: ancient, modern and contemporary military history, promoting patriotism, collectivism and education in revolutionary heroism. Emphasis would be given to the bloody struggles of the Chinese nation to achieve unification, independence and wealth and power; the role of the CCP in leading the whole people and the army in the revolution; stimulating patriotism by understanding the noble character and glorious deeds of revolutionary martyrs, national heroes and righteous individuals

- Defense Situation and Responsibilities: understanding the international and domestic situations to oppose splittism and to protect national unity; clarifying the challenging security environment; clarifying the responsibility for national defense construction and struggle, strengthening a crisis mentality among the citizens 增強公民的憂患意識

- National Defense Technology Capability: military training for students and national defense exercises for the masses; defensive measures for air raids and nuclear war, battlefield rescue, use of light arms and military techniques for the individual soldier and units; building morale and stamina.

— based on Christopher R. Hughes

Militarism and the China Model:

The Case of National Defense Education

Journal of Contemporary China, 2017

(26:103): 54-67, at pp.56-57

Country-wide national defence awareness and education in the new millennium in some ways was a revitalisation and continuation of the ‘All People Are to Be Soldiers’ 全民皆兵 policy formalised by the Party’s Military Commission in late 1958. Faced at the time with the need to develop an army reserve while maintaining a civilian militia, the military decided that all citizens of a certain age had to undergo military training, including instruction in army affairs and the use of basic weapons. This policy would continue throughout the era of High Maoism (roughly 1957-1977, that is from the Anti-Rightist Movement until the start of de-Maoification).

Along with the military induction of young people and citizens from the early 2000s, the ancient Greek warrior city-state of Sparta, first promoted by educators a century ago as noted above, also reappeared as an ideal. The Spartan system was now praised

for being designed not only to familiarize the population with weapons and military ways of thinking, but also to further the ideological goal of propagating a ‘spirit of appreciating the military’ (尚武精神) in the general population. As a combined delegation from the Second Artillery and Wuhan University to the 2005 National Conference on National Defense Education in Higher Education explains, it is vital to build such a spirit in order to combat the spread of decadence, to prevent further erosion of the values of self-sacrifice and to counter the tendency for leading cadres to forget how economic development should be related to building a ‘rich country and powerful army’ (富国强兵).

The analogy with Sparta and the call to propagate a ‘spirit of appreciating the military’ (尚武精神) in the cause of building a ‘rich and powerful country’ also draws attention to the fact that National Defense Education has its roots in a program to use militarism to promote modernization that has its origins in China long before the establishment of the PRC. Present-day advocates of National Defense Education themselves trace it to Chinese political activists who were active in Japan at the start of the twentieth century. Best-known is Liang Qichao (梁启超), who set out to construct a Chinese version of the bushido [武士道] spirit. Liang’s followers believed that the way to disseminate this spirit of ‘appreciating the military’ was to emulate the policy of ‘military-citizen education’ (gunkokumin kyōiku 军国民教育) that had been introduced in Japan after the Meiji Restoration.

— Hughes, ‘Militarism and the China Model’, p.62

Like a Fart in a Bath

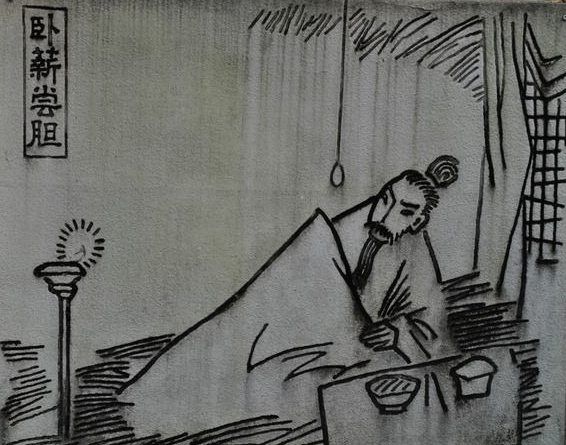

In 1992, Hu Qiaomu 胡喬木, one of the main protagonists of these Lessons in New Sinology, died at the age of eighty. It was exactly half a century since he had published ‘Dogmas & Pants’ 教條與褲子, an essay that helped launch, and define, the Yan’an Rectification Campaign, one of the most consequential periods in the history of China’s Communist Party.

As we noted in Ruling the Rivers & Mountains, the first part of ‘Drop Your Pants! The Party Wants to Patriotise You All Over Again’, in ‘Dogmas & Pants’ Hu employed the metaphors of ‘pants, tails and washing’ to describe the process of revelation, self-criticism and mass denunciation, and exoneration that would allow the Party under Mao Zedong to impose its will on the whole organisation. This schema was applied during the ‘rectification’ 整風 to force cadres to examine their ideas (and their previous loyalties), confess their ideological shortcomings and subject themselves to the merciless critiques of their comrades.

The process of rectification, which culminated in a major Party congress in 1945, bestowed an unassailable status on Mao Zedong’s ideas, strategy and language in the Party as a whole. This would, despite numerous attempts at ‘revisions’, continue until after the Chairman’s demise in September 1976. The Yan’an Rectification remains an important blueprint for the Party’s internal mechanisms of rule and compliance even today. As we have indicated throughout this series of essays, the ‘Yan’an Way’ informs the 2018 Patriotic Education Campaign launched by the Communists in late July, and it provides the foundation for the training of New People in the present epoch of Xi Jinping, the subject of Homo Xinensis Ascendant.

We will return to the activities of Hu Qiaomu in the last years of his life, and discuss his role in helping the Communist Party repositioned itself after the events of 1989 in another Lesson in New Sinology. In the meantime, we now shift our focus to Hu’s own revolutionary successor, his daughter, Hu Muying (胡木英, 1941-). Ten years after her father’s demise, Hu fille assumed the leadership of a group that called itself The Fellowship of the Children of Yan’an 延安兒女聯誼會. She had only been fourteen months old when her father — a man who we will recall Mao praised as a model Party intellectual, one ‘with the most thoroughly reformed thinking and the most beautiful of souls’ 思想改造得最好、靈魂最美 — published ‘Dogmas & Pants’, but in the absence of her father, Hu Muying would become an outspoken supporter for the Yan’an Way and a revival of Party norms.

The Children of Yan’an had its origins in April 1984, when a group of students who had graduated from elite Party middle schools in Beijing prior to the Cultural Revolution came together to celebrate their camaraderie, as well as their origins. Initially, they called their informal group the Fellowship of the Children of New China 新華兒女聯誼會. During the centenary of Mao Zedong’s birth in 1993, they renamed themselves the Beijing Children of Yan’an Classmates Fellowship 北京延安兒女校友聯誼會. Members were the descendants of men and women who had lived and worked in the Yan’an Communist Base in Shaanxi province from the 1930s to the 1940s, as well as the progeny of the Party who were born and educated in Yan’an. From 1998, they met annually during Spring Festival (Chinese New Year). Members also participated in a range of other events organised around choral and dancing groups, Tai chi classes, and painting and calligraphy activities. In 2008, the Fellowship expanded its membership to include others without any direct link to the old Communist base. Henceforth, The Children of Yan’an would include anyone who wanted to collaborate under its banner and support its vision:

to inherit the revolutionary tradition, glorify the Yan’an spirit, build camaraderie with the children of the revolution, sing the praises of the national ethos and to work in various capacities for the old revolutionary areas, ethnic regions, the nation’s frontiers and impoverished areas. 繼承革命傳統,弘揚延安精神,聯誼革命後代的情誼,謳歌民族正氣,為老少邊窮地區做些力所能及的工作。

At the 2011 Lunar New Year meeting held in the run-up to the 2012 change in party-state leadership, Hu Muying declared:

The new explorations made possible by Reform and the Open Door policies [inaugurated in 1978] have, over the past three decades, resulted in remarkable economic results. At the same time, ideological confusion has reigned and the country has been awash in intellectual currents that negate Mao Zedong Thought and Socialism. Corruption and the disparity between the wealthy and the poor are of increasingly serious concern; latent social contradictions are becoming more extreme.

We are absolutely not ‘Princelings’, nor are we ‘Second-generation Bureaucrats’. We are the Red Successors, the Revolutionary Progeny, and as such we cannot but be concerned about the fate of our Party, our Nation and our People. We can no longer ignore the present crisis of the Party.

Hu went on to say that through the activities of study groups, lecture series and symposiums The Children of Yan’an had formulated a document that, following broad-based consultation, would be presented for the consideration of the authorities in the lead up to the Communist Party’s late-2012 Eighteenth Party Congress. She said:

We cannot be satisfied merely with reminiscences nor can we wallow in nostalgia for the glories of the sufferings of our parents’ generation. We must carry on in their heroic spirit, contemplate and forge ahead by asking ever-new questions that respond to the new situations with which we are confronted. We must attempt to address these questions and contribute to the healthy growth of our Party and help prevent our People once more from eating the bitterness of the capitalist past.

In essence, the document drafted by the Children of Yan’an and publicised by them in the lead up to the politically momentous 2012 Party Congress and the dominance of Xi Jinping, called for a revival of the legacy of the revolutionary past and for the recognition of what could be called the left-wing faction within the Communist Party itself.

Hu Muying was one of a number of Party progeny who declared they inherited the Red Genes 紅色基因 of Yan’an and were, generally above the corruption that during the first decade of the new millennium was said to be threatening the very survival of the Communist enterprise. Their concern for Party domination of the Rivers and Mountains of China, discussed in Part I, in many ways recalled the Red Guard elite of 1966 that formed itself into a group call United Action (聯動, the full name of which was 首都中學紅衛兵聯合行動委員會).

Consisting primarily of the children of Party leaders and martyrs, United Action regarded themselves as the legitimate Revolutionary Successors to the Communist cause. One of their slogans was ‘Protect the Rivers and Mountains Conquered by Our Fathers’ 保衛老一輩打下的江山. These heritage Red Guards condemned anyone who did not have their revolutionary credentials (their original slogan was: ‘Dad a hero, son a stalwart; dad a reactionary, son a bastard; that’s the way it goes’ 老子英雄兒好漢, 父親反動兒混蛋; 基本如此). Although, like virtually every other rebel group at the time, they were eventually repressed, United Action gave voice to members of the entrenched and entitled Party elite that would resurface during the Reform era after 1978. Many members of the group, or those sympathetic with it, are in lockstep with Xi Jinping’s revivalist policies.

The Children of Yan’an have also supported the advent of Xi Jinping. After all, he is one of their own. In May 2014, Hu Muying declared:

The Centre under General Secretary Xi Jinping has raised high the banners of ‘Opposing the Four Winds’, [Note: The ‘four winds’ or habits 風 are: formalism 形式主義, bureaucratism 官僚主義, hedonism 享樂主義 and extravagance 奢靡之風] Anti-Corruption Pro-Frugality and Mass Line Education. These Three Banners are backed up by real action against the ill-winds and the pernicious miasma that has suffused our world for many years, and he’s taken the knife to both Tigers and Flies.