Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium

Appendix XXVII

謔

A Congratulatory Couplet for Xi Jinping

上聯:慌慌開場,親自指揮親自部署,唯恐天下不知;

Right-hand column:

In unseemly haste he imposed his policies making sure everyone knew he was personally in charge of everything

下聯:草草落幕,各自指揮各自部署,生怕民眾白紙。

Left-hand column:

The curtain fell on the performance in chaos, with everyone but him taking a lead, fearful of more blank pages

橫批:我將無我

Horizontal evaluation:

So this is what you mean when you talk about ‘being selfless’

— Chinese Internet humour, early December 2022

***

On 8 December 2022, The New York Times reported that:

A day after China’s ruling Communist Party announced a broad rollback of the “zero Covid” restrictions that had smothered the economy and transformed life in the country, the propaganda apparatus on Thursday began the daunting task of promoting an audacious revision of history.

While the rest of the world concluded months ago that the coronavirus was becoming less deadly, Beijing presented the development as fresh news to explain its abrupt decision to undo the lockdowns that prompted widespread protests. …

For months, state media commentaries and experts had played up the threat of Omicron to justify his strict policy of lockdowns, mass quarantines and testing that had disrupted daily life.

“They knew the severity of Omicron, but they did not want to tell people the truth. Instead they started to exaggerate the severity of the disease, the virulence, in order to justify the policy of ‘zero Covid,’” said Yanzhong Huang, a global health specialist and a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations.

“Suddenly, you have all these experts coming out to justify why this policy relaxation is necessary,” he said, referring to health officials whose messages around the pandemic have pivoted drastically in recent days.

China’s jarring, whiplash-inducing narrative shift around Omicron points to the challenge for the party as it tries to prevent this week’s sudden abandoning of “zero Covid” from being construed as an admission of failure and a stain on Mr. Xi’s legacy. For years, China has pushed a triumphalist narrative about its top-down, heavy-handed approach to eradicating infections, saying that only the Communist Party, under Mr. Xi’s leadership, had the will and ability to save lives.

The changes the government announced on Wednesday — which would limit lockdowns and scrap mass mandatory quarantines and hospitalization for most cases — amounted to a reversal of “zero Covid” in the face of public opposition and mounting economic costs. But the party is deploying the full force of its propaganda and censorship apparatus to depict the transition as part of the plan all along. …

Even the term “zero Covid” has suddenly disappeared from official statements and officials’ remarks. …

Many Chinese returned to Dr. Li Wenliang, the first victim of censorship involving the pandemic, who died in early 2020 after contracting the coronavirus. Users flocked to Dr. Li’s Weibo page to leave heartfelt notes of solidarity. “Dr. Li, it’s finally over.” one user wrote. “We miss you. Thank you for your hard work.”

— Amy Chang Chien, Chang Che and John Liu, ‘Zero Covid,’ Once Ubiquitous, Vanishes in China’s Messy Pivot, The New York Times, 8 December 2022

Despite the mixed signals coming out of Beijing, on 11 December 2022, an authoritative opinion piece published in People’s Daily, the mouth piece of the Communist Party, declared that:

It is absolutely necessary for people to appreciate that the present optimisation of our suite of coronavirus responses reflects a forward-leaning recalibration and is not a passive reaction to circumstances. The Ten New Regulations that have been announced in no way signal a relaxation of our Covid response, let alone do they signify a complete opening up or so-called ‘giving in and giving up’.

必須認識到,優化疫情防控措施是主動的優化而不是被動的,新十條出台不是放鬆防控,更不是完全放開或所謂「躺平」。

— 仲音, 形成合力,落實好疫情防控優化措施, 《人民日報》,2022年12月11日

trans. GRB

***

A New Situation and New Tasks

我國疫情防控面臨新形勢新任務…

‘The country is facing a new situation and new tasks in epidemic prevention and control as the pathogenicity of the Omicron virus weakens, more people are vaccinated and experience in containing the virus is accumulated.’

— Vice-premier Sun Chunlan, China’s ‘Covid Tsarina’, 1 December 2022

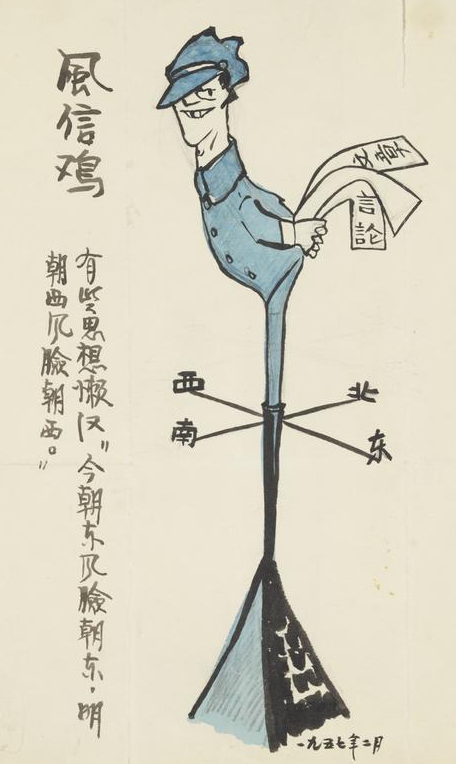

Comrade Hu Xijin 胡錫進, one of the most reliable weathervanes in the People’s Republic who is intimately familiar with the mutable prerogatives of Communist Party policy-making, had the following to say:

Chinese has sounded the clarion call for the country to return to normal life. These measures are more resolute than the recent self-adjusting measures of various provinces. It is a reflection of the whole country’s determination to escape the shackles of COVID-19. pic.twitter.com/FuEQahBBGG

— Hu Xijin 胡锡进 (@HuXijin_GT) December 7, 2022

***

Students of Chinese politics might be familiar with some of the outmoded expressions for Hu Xijin’s brand of pirouetting prowess include: 緊跟形勢 ‘to follow assiduously the ever-changing situation’, 與時俱進 ‘keeping up with the times’ and the dreaded 落後於形勢 ‘to fail to keep up with the changing priorities of the Party’. Older traditional Chinese expressions also come to mind. They include: 人云亦云 ‘to parrot what others say’ and 亦步亦趨 ‘to follow in the footsteps of others’.

In 1957, the artist Hua Junwu 華君武 summed up the mutability of Party policy and cadres’ responses in a painting that is still worth a thousand words:

— from G.R. Barmé, Mendacious, Hyperbolic & Fatuous — an ill wind from People’s Daily, China Heritage, 10 July 2018

***

This appendix to Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium should be read in conjunction with the following:

- Chapter Twenty 咒 — A Hosanna for Chairman Mao & Canticles for Party General Secretary Xi, 22 October 2022

- Chapter Twenty-one 醒 — Awakenings — a Voice from Young China on the Duty to Rebel, 14 November 2022

- Chapter Twenty-two 官逼民反 — Fear, Fury & Protest — three years of viral alarm, 27 November 2022

- Appendix XV 零 — Xi the Exterminator & the Perfection of Covid Wisdom, 1 September 2022

- Appendix XXIII 空白 — How to Read a Blank Sheet of Paper, 30 November 2022

- Appendix XXIV 職責— It’s My Duty, 1 December 2022

- Appendix XXV 贖 — ‘Ironic Points of Light’ — acts of redemption on the blank pages of history, 4 December 2022

- Appendix XXVI 囿 — A Ray of Light, A Glimmer of Hope — Li Yuan talks to Jeremy Goldkorn & to a Shanghai protester, 10 December 2022

- Optimization: Another Word for Messy, China Media Project, 2 February 2023

- China’s Political Discourse December 2022: A Slap in the Face on Covid Policy by China Media Project, Sinocism, 6 February 2023

***

My thanks to Sebastian Veg for alerting me to Zhang Lifan’s ‘lesson in the Covid lexicon’, as well as nudging me to find a passable translation for the ugly term 核酸檢測.

— Geremie R. Barmé, Editor, China Heritage

Distinguished Fellow, Asia Society

12 December 2022

***

A Zig for Every Zag

There was once a man who had taken employment as a steward on a seagoing ship. It was explained to him that, in order to avoid breaking plates when the ship was rolling in heavy weather, he must not walk in a straight line, but try to move in a zigzag manner: this was what experienced seamen did. The man said that he understood. Bad weather duly came, and presently there was heard the terrible sound of breaking plates as the steward and his load crashed to the ground. He was asked why he had not followed instructions. ‘I did,’ he said. ‘I did as I was told. But when I zigged the ship zagged, and when I zagged the ship zigged.’

Capacity for careful co-ordination of his movements with the dialectical movement of the Party—a semi-instinctive knowledge of the precise instant when zig turns into zag—is the most precious knack that a Soviet citizen can acquire. Lack of facility in this art, for which no amount of theoretical understanding of the system can compensate, has proved the undoing of some of the ablest, most useful and, in the very early days, most fanatically devoted and least corrupt supporters of the regime.

— from Isaiah Berlin, et al, Xi Jinping’s China & Stalin’s Artificial Dialectic, China Heritage, 10 June 2021

***

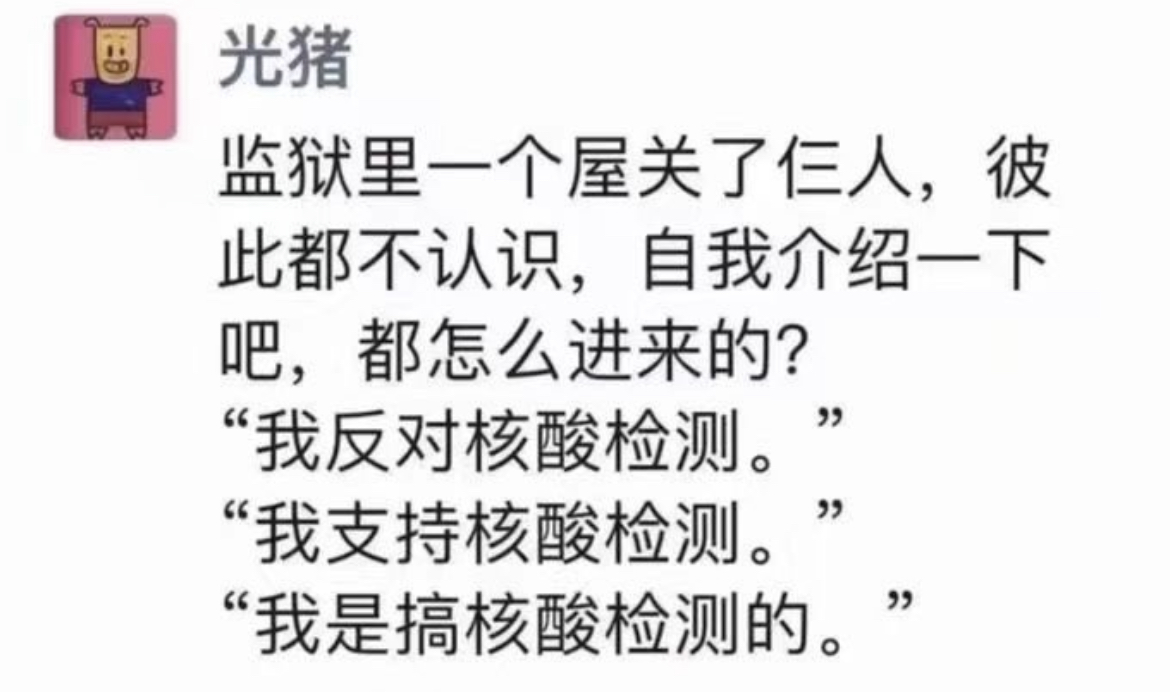

Three people in the same cell explain to each other why they are in jail:

A: ‘I opposed Covid tests.’

B: ‘I supported Covid tests.’

C: ‘I administered Covid tests.’

— Chinese Internet joke

***

Follow Me

跟我學

Zhang Lifan 章立凡

新冠以来流行新名词汇编

视频【突然发现自己的语文都白学了……】 pic.twitter.com/waC2qQXViu

— 章立凡 ©️Zhang Lifan💎 (@zhanglifan) November 10, 2022

Whataboutism

‘In Russia is freedom of speech. In America is also freedom after speech.’

— Yakov Smirnoff

Яков Смирнов

***

The Origins of the Political Joke

Gregor Benton

(author of the Big Red Joke Book, 1976)

Political jokes run in the veins of modem dictatorships of all political sorts, but they are at their best and most plentiful in the Soviet Union, and it is with the Soviet joke and its close relatives that these pages will chiefly engage.

Political jokes are told by hundreds of thousands to an audience of hundreds of millions, but they are little known outside the dictatorships that produce them. They are a product of acute tension and inhibition — conditions under which good humour commonly thrives — and despite their specific grievances, they have a universal quality, carrying well even where their point does not directly apply. In the West, joke-telling is fast becoming the business of paid entertainers who serve an audience of television-viewers. Political jokes are not so handicapped: for obvious reasons they mainly circulate only outside official channels. Tellers and hearers develop a great appetite for them and are critical judges of the art, killing off any that do not meet the highest standards.

Political jokes are the citizens’ response to the state’s efforts to standardise their thinking and to frighten them into withholding criticism and dissent. Freud said that jokes are especially suited for ridiculing people in high places who we would otherwise fear to attack because of inner or outer inhibitions. The political joke perfectly illustrates this point. The politically powerless use it as a tribunal through which to pass judgements on society where other ways of doing so are closed to them.

Political jokes give a unique view into the problems of everyday living under dictatorships. They are peopled by all social types, from Party bosses and prima donnas to small-town bureaucrats and drunks. Most questions are reflected in them, from the price of tables to the rate of spending on space travel. They are a powerful transmitter of the popular mood in societies where this mood can find no officially sanctioned outlet. A good joke that hits the right wavelength with a topical issue will bounce from Brest to Vladivostok and back at a speed that the Minister of Information would envy.

In itself, political humour is nothing new. Ever since there were states, philosophers and court clowns have poked fun at those holding the reins of power in society. The ancient Greeks and Romans saw mockery as a legitimate weapon in the political armoury, and sages of ancient China had a quick eye for folly and hypocrisy in high places, and a savage tongue. But humour of this sort was mainly for the elite. The people who supported the base of pre-modern societies had no real tradition of political humour as we now know it, for they knew little of high politics. No doubt local despots were the butt of some class-inspired laughter in the villages, but villagers lacked political distance from them, and without distance humour is not easy.

Not all people in lowly positions were as remote from the centres of power and decision. Flunkies, prostitutes, petty retainers, yamen runners, and the like, had a wider view of the political process, and if the seeds of an early popular political humour ever sprouted, it was surely among them. But whatever the case, there is little that can be said about it, since such oral culture went largely unrecorded across the centuries.

Modern societies in which the people have democratic freedoms also know political jokes — you could even say that the right to tell them is one of those freedoms. But most political jokes in bourgeois democracies are a bloodless strain, told by professionals. The reason is obvious: a society with the vote has no urgent need of political jokes, for it has more effective ways of easing political tensions.

It is only under modern dictatorships that political jokes come truly into their own and are part of the everyday life of all classes. Factory workers swap them; and so do bishops, brain surgeons, tractor drivers … and, of course, the dictators themselves. Such jokes are no longer about the foibles and idiosyncracies of this or that top politician, as are most political jokes in democracies: they take in the whole range of issues in politics and society as their subject matter. To be sure, political jokes are not the only vehicle for non-official opinion in societies that forbid opposition, but they are probably the least dangerous. Joke-tellers, unlike the intellectuals who write samizdats or the activists who take their protests on to the street, need be neither book-trained nor especially brave: all they need is a sense of fun and timing, and humour can even defuse the wrath of some officials. Even so, it is wise to tell your most outrageous jokes in parks and open fields, out of earshot of policemen and informers. In Hitler’s Germany the very word for political joke was Flüsterwitz or ‘whisper joke’. One anti-Hitler joke (based as usual on a Jewish original) tells it all:

Five citizens of the Reich sit in a railway room. One sighs, another clasps his head in his hands, a third groans, and a fourth sits with tears streaming down his face. Says the fifth: ‘Be careful, gentlemen. It’s not wise to discuss politics in public.’

— from Humour in Society Resistance and Control, Chris Powell

and George E.C. Paton, eds, London: The Macmillan Press, 1988, pp.33-35

Lock Him Up!

Chinese Whispers & An Old Tale Retold

The Soviet Union, 1937:

Three men are sitting in a cell in the KGB headquarters. The first asks the second why he has been imprisoned, who replies, ‘Because I criticized Karl Radek.’

The first man responds, ‘But I am here because I spoke out in favor of Radek!’

They turn to the third man who has been sitting quietly in the back, and ask him why he is in jail.

He answers, ‘I am Karl Radek.’

[Note: The real-world fate Radek was a plangent one. Despite his role in drafting the Soviet Constitution this Old Bolshevik was denounced as a traitor and persecuted during the Moscow Show Trials of 1936-1938. Sentenced to ten years of labour reform, Radek was murdered by a fellow inmate. He was rehabilitated by Mikhail Gorbachev in 1988. Radek is thought to be one of the models for the character Rubashov in Arthur Koestler’s 1940 novel Darkness at Noon.

The Moscow Show Trials have had a profound and continuing influence on China’s Communists. Having audited the trials in Moscow, a Party zealot by the name of Kang Sheng (康生, 1898-1975) went on to the Communist guerrilla base at Yan’an where he advised Mao, Liu Shaoqi, Hu Qiaomu and Chen Boda — among others — on how to design and carry out the Yan’an Rectification Campaign, a years-long ideological purge that remade the Party. The process also proved fatal for an unknown number of participants. The Yan’an Rectification became a model for subsequent purges. It remains an inspiration for Xi Jinping and his comrades today.]

***

The People’s Republic of China, 1976:

Three inmates in a Peking prison ask each other how they had gotten into such a fix.

‘I am here because I supported Deng Xiaoping,’ said one, referring to China’s controversial vice premier.

‘I am here because I opposed Deng Xiaoping,’ said the second inmate.

The two looked at the third man who said: ‘I am Deng Xiaoping.’

***

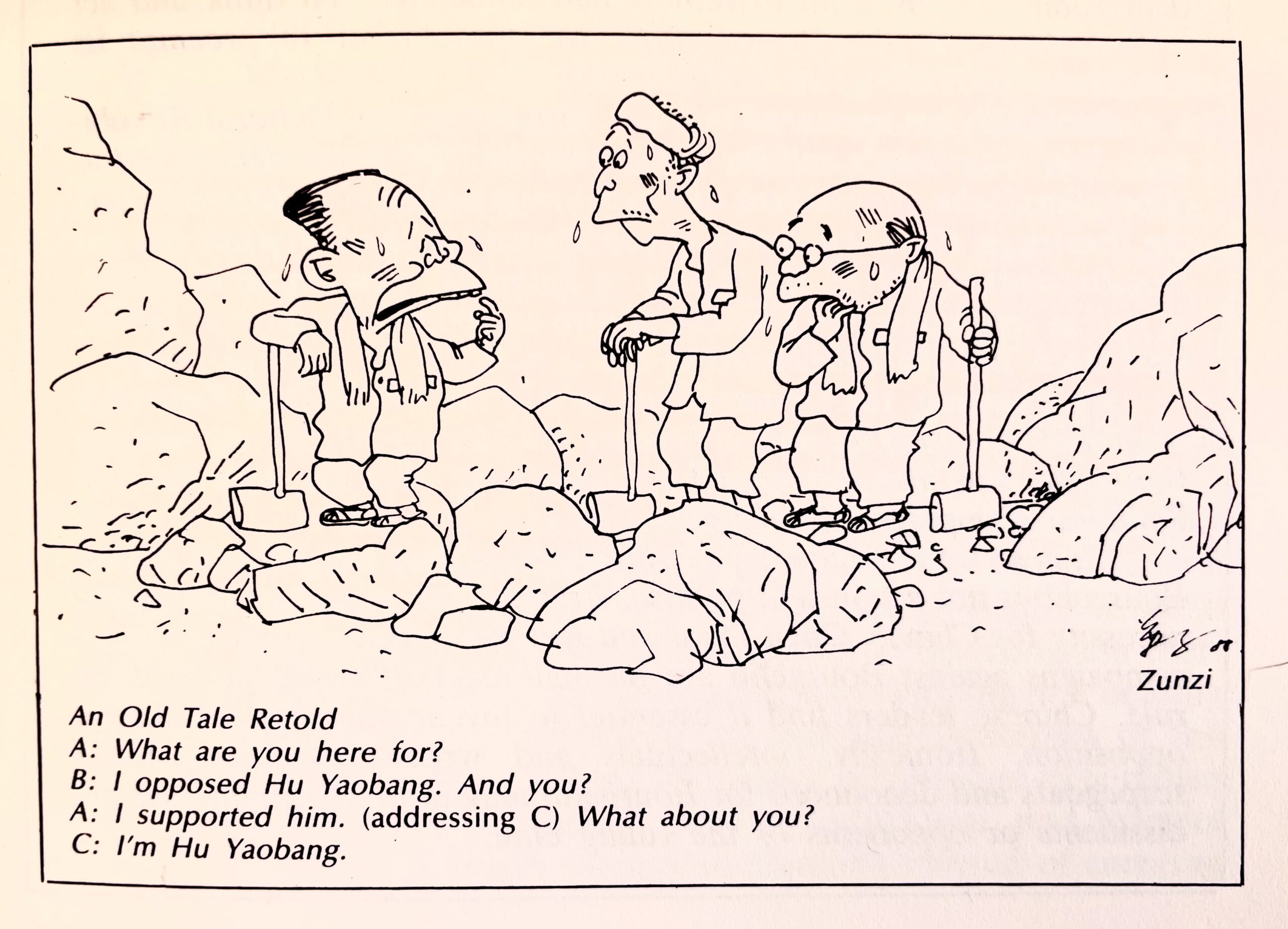

The People’s Republic of China, 1987:

In 1987, as we prepared an expanded second edition of Seeds of Fire: Chinese Voices of Conscience, John Minford and I commissioned a young Hong Kong political cartoonist known by his pen name Zunzi 尊子 (Wong Kei-kwan 黃紀鈞, 1955-) to rework the old joke for our book.

Party General Secretary Hu Yaobang had been purged in January 1987 for condoning the pernicious influence of ‘bourgeois liberalisation’ that undermined Party authority and encouraged student protesters who, in late 1986, agitated for media freedom and democracy. Hu was replaced by the premier, Zhao Ziyang. In June, 1989 it would be Zhao’s turn.

Zunzi’s cartoon (above) appeared in the second edition of Seeds of Fire, which was published in New York in January 1988.

***

Bada bing, bada boom

A Soviet judge walks through a hallway bursting out laughing. A colleague asks him:

‘What’s so funny?’

‘A political joke I just heard.’

‘Tell it to me then.’

‘No I can’t. I just gave someone fifteen years for it.’