Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium

Chapter XXI

醒

Awakenings is Oliver Sacks’s 1993 account of a group of patients who contracted sleeping-sickness during the great epidemic just after World War I. They were frozen in a decades-long sleep until, in 1969, Sacks administered a drug that had an astonishing, explosive, ‘awakening’ effect.

***

Age of Awakening 覺醒年代, a 43-episode tele-series produced as part of the official celebration of the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Chinese Communist Party in 2021, was a surprise hit with viewers.

The series offers a colourful, and highly fanciful, account of what is known as China’s ‘enlightenment’ 啟蒙 qǐméng, a period of dramatic change known as the New Culture Movement starting in 1915 that culminated with the 1919 May Fourth Movement. That student-led protest against the imperialist powers and in support of democracy led to the founding of the Communist Party in 1921.

‘Awakening’ 覺醒 juéxǐng (also jiàoxǐng) has been the leitmotif of Chinese political and cultural life since the late nineteenth century. For elites and activists of all persuasions, the ‘awakening’ of the nation and the rousing of the people from a deep-seated torpor was essential for the country to achieve modern nationhood and, in the process, for individuals to enjoy a new sense of meaning and self-awareness. In his final testament Sun Yat-sen, the iconic leader of the republican revolution known as the ‘father of the nation’ 國父 guó fù, declared that he had put decades of effort into the urgent cause of ‘awakening the masses’ 喚起民眾 huànqǐ mínzhòng, a central task in building a modern China.

During the first decade of the twenty-first century, concerned Party patriots — members of the nomenclature, New Leftists, the red progeny of founders of the People’s Republic — raised their voices to ‘wake the world up’ 醒世 xǐng shì to the polycrisis confronting China as economic reforms continued to undermine political rectitude and the Party’s grip on power (see, for example, 盛世新危言 The Children of Yan’an: New Words of Warning to a Prosperous Age, China Heritage Quarterly, June 2011). In the Xi Jinping era proper, the Chinese Communist Party repeats ad nauseam its tradition of revolutionary foresight aimed at rousing the Chinese people so they will engage in ever-new struggles to achieve national greatness.

When celebrating four decades of reform in December 2018, Xi Jinping declared that ‘the Economic Reform and Open door policies were a major awakening’ [改革開放是我們黨的一次偉大覺醒]. He went on to say that ‘The reform era has nurtured a creative boom in which theory has been realised in practice. These policies are a great revolution in the annals of Chinese history and have spurred on a great leap in the development of socialist China.’

The egregious rule of Xi Jinping itself has awakened many Chinese people — on the Mainland, in Hong Kong and on Taiwan — as well as academic specialists, journalists, commentators, diplomats and business people to the abiding nature of the Chinese party-state.

***

‘Awakenings 醒’ is the theme of this chapter in Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium. Following a series of short, introductory essays, it features a conversation between Li Yuan, a New York Times journalist and podcaster, and Kathy, a member of a group of young overseas Chinese students who were inspired by Peng Zaizhou, the ‘Beijing Bridge Man’.

Readers familiar with the history of High Maoism (c.1956-1976) will know the slogan ‘To rebel is justified’ 造反有理 zàofăn yŏu lĭ, which was paired with the line ‘revolution is legitimate’ 革命無罪 gémìng wú zuì. This was the clarion call of the Red Guards who, encouraged by the Chairman to overthrow his ideological and bureaucratic opponents wreaked havoc in 1966-1967 (see Luo Xiaohai 駱小海, a founder of the Red Guards, in the documentary film Morning Sun). Many members of that generation of ‘politically awakened’ radicals would undergo a second, corrective awakening. First, in April 1976, they would rebel against the leaders of the Cultural Revolution in Tiananmen Square and then, in late 1978, some of them would play a prominent role in the Democracy Wall Movement. That lineage of rebellion lives on in the efforts of young people like Kathy and their Democracy Wall protests today.

My gratitude, as ever, to Reader #1 for going over the draft of this essay and to Li Yuan for permission to translate her conversation with Kathy.

This chapter in Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium should be read in conjunction with:

- Chapter Twenty-two 官逼民反 — Fear, Fury & Protest — three years of viral alarm, 27 November 2022; and,

- Appendix XXIII 空白 — How to Read a Blank Sheet of Paper, 30 November 2022

- Appendix XXIV 職責— It’s My Duty, 1 December 2022

- Appendix XXV 贖 — ‘Ironic Points of Light’ — acts of redemption on the blank pages of history, 4 December 2022

- Appendix XXVI 囿 — A Ray of Light, A Glimmer of Hope — Li Yuan talks to Jeremy Goldkorn & to a Shanghai protester, 10 December 2022

- Appendix XXVII 謔— When Zig Turns Into Zag the Joke is on Everyone, 12 December 2022

- Appendix LV 一週年 — What Scares Me — a letter from Kathy on the first anniversary of the Blank Page Movement, 4 December 2023

— Geremie R. Barmé, Editor, China Heritage

Distinguished Fellow, The Asia Society

14 November 2022

***

Related Material:

Updates:

- Li Yuan, China’s Protest Prophet, The New York Times, 7 December 2022

- Daniel Boffey, Chinese students in UK told to ‘resist distorting’ China’s Covid policies, The Guardian, 8 December 2022

- What Scares Me — a letter from Kathy on the first anniversary of the Blank Page Movement, 4 December 2023

- 伦敦myduty民主墙, Telegram group

- @CitizensDaily CN, Twitter

- @Northern Square, Instagram

- @Citizen’s Daily, Instagram

- Lily Kuo, Vic Chiang and Theodora Yu, One man’s bold protest against China’s leaders inspires global copycats, The Washington Post, 10 November 2022

- Li Yuan袁莉, ‘Who Gets It? — conversations with Li Yuan’ 不明白播客, a podcast series on contemporary China, interviews with transcripts

- Wu Guoguang 吳國光, Exit Stage Right — Hu Jintao’s staggering departure from China’s political scene, China Heritage, 23 October 2022

- Wang Jixian: A Voice from The Other China, but in Odessa, 12 March 2022; and, I’ve Forgotten How to Kneel in Front of You, 21 March 2022

- Namewee 黃明志 et al, The Right to Know & the Need to Lampoon, China Heritage, 18 October 2021

- Jeffrey N. Wasserstrom, A Hundred Years of Student Protests in China, The Crack-up Podcast, 17 June 2019

- Silent China & Its Enemies — Watching China Watching (XXX), China Heritage, 13 July 2018

- Living with Xi Dada’s China — Making Choices and Cutting Deals, (16 December 2016), published in China Heritage, 20 July 2017

- Xu Zhangrun Archive, China Heritage (1 August 2018-)

- Hong Kong Apostasy, China Heritage (1 July 2017-)

- John Fitzgerald, Awakening China: Politics, Culture, and Class in the Nationalist Revolution, Stanford University Press, 1996

From Viral Alarm — China Heritage Annual 2020:

- The innocent cry to Heaven. The odour of such a state is felt on high., 1 October 2020

- The Heart of The One Grows Ever More Arrogant and Proud, 10 March 2020

Contents

This chapter of Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium is divided into the following sections (click on a section title to scroll down):

***

Cycles of Awakening China

‘Awakening is a nebulous concept, poised somewhere between the transitive and the intransitive, and referring to nothing in particular apart from a transition in a state of consciousness from sleep to wakefulness. In Chinese, the word usually takes the intransitive forms jue 覺, juewu 覺悟, xing 醒, or juexing 覺醒, meaning “to undergo an awakening.” In mass politics it also takes the transitive form of awakening others (huanqi 喚起, huanxing 喚醒), or may take the imperative mood, “Wake up!” (xing! 醒! juewu! 覺悟!). In the general context of the nationalist movement, the term was understood to mean that the people of China were awakening to their nationhood in a gradual process involving changes in popular fashion and taste, a growing curiosity about personal identity and the meaning of life, a disturbing engagement with the judgments of colonial racism, and the cumulative effects of accelerating commercialization and industrialization. Nationalists, however, were reluctant to let the nation awaken of its own accord. The country cried out to be “awakened” by reformers and revolutionaries possessing an intense sense of purpose, a keen commitment to the dictates of reason, and a formidable capacity for political organization and discipline.

‘This conjunction of passive and active forces is common to nation-building movements in colonial states, where, in the words of Benedict Anderson, “one sees both a genuine, popular nationalist enthusiasm, and a systematic, even Machiavellian, instilling of nationalist ideology through the mass media, the educational system, administrative regulations.” Both senses of the term “awakening,” the intransitive and the transitive, must be retained to remain faithful to the language of China’s national awakening. At the same time, each needs to be distinguished from the other in order to distinguish the evolutionary from the revolutionary aspects of China’s national revolution. The problem, then, is to explain the transition from one sense of awakening to another, from the intransitive to the transitive, and to trace the institutionalization of the idea of a national awakening from an inchoate aspiration into a distinctive style of disciplined mass politics under the supervision of a highly disciplined, pedagogical state.

‘The motif of an awakening complicates any attempt to isolate the systematic and public efforts of political activists from the more personal and less deliberate awakenings of ordinary people. It was ubiquitous. Although the term makes no appearance in any concordance to Chinese nationalism, any survey of the culture of the period would show that it was one of the most common expressions to make an appearance in the diaries and autobiographies, the art and literature, the ethics and education, the history and archaeology, the science and medicine, the geography and ethnography, and, of course, the politics of the day. Its ubiquity helps to explain the convergence of a nationally oriented cultural movement with a movement to build an independent and sovereign nation-state. That is to say, the idea of a national awakening helped to link a variety of distinctive cultural fields with one another and with the world of political action. It was sufficiently universal to cross discursive boundaries and make room for nationalist politics in science, philosophy, and literature, and it was sufficiently agile to draw political activists to the worlds of science, philosophy, and literature in an effort to conscript intellectuals to the service of the revolutionary state.’

— from John Fitzgerald, Awakening China: Politics, Culture, and Class in the Nationalist Revolution, Stanford University Press, 1996, pp.3-4, Chinese characters added

As Fitzgerald points out, the process of awakening the people has been integral to the Chinese party-state since the 1920s, first under the Nationalist Party under Sun Yat-sen and then in parallel under the Communist Party. He notes that ‘The birth of modern Chinese nationalism entailed an awakening not only to the nation but to the universal ideals of enlightenment, progress, and science, to the autonomy of the individual and “self-realization,” and to the claims of mass communities for a place in the polity and the claims of the polity itself for unity and sovereign independence.’ (p.24) We have argued that the communist awakening is of a similar although different order along Marxist-Stalinist lines. The Communist Party is led by a vanguard of those who are first aware and awoken 先知先覺, patriarchs who forever lead, teach, guide and educate all others. Their Party position confirms their enlightened status and with it their sole right to mentor the nation. Unauthorised ‘awakenings’ are outlawed.

***

Decades of Arousal

In China, recurrent political, social and cultural ‘awakenings’ have variously been hailed, debated, commemorated and forgotten for over a century. Gore Vidal famously declared that America was a ‘United States of Amnesia’; China, too, be it during the Republican era or throughout the history of the People’s Republic, is also a nation of studied, and manufactured, forgetfulness. As a result, every generation experiences an awakening of its own, ones that replicate, add and extend the awakenings of their predecessors. (For more on this topic, Anniversaries New & Old in 2019, China Heritage, 4 May 2019.)

Since the death of Mao Zedong in 1976, China’s People’s Republic has experienced roughly five moments of socio-political ‘awakening’. Occurring roughly a decade apart, each has inspired people of conscience to question their relationship with the Communist Party, their community and even China itself. Both individual and group awakenings have also been routinely suppressed by supporters of the status quo who regard rogue self-awareness as inimical to the project of the party-state and independent thought as an existential threat both to the collective as well as to somnolent partisans. In this context reforms — political, economic, social and cultural — are a threat to the primacy of the Party and its mission to own history.

Below we offer a shorthand chronology of the moral-political awakenings that have erupted on Mainland China since 1976 and the attempts by the party-state to keep society locked up in Lu Xun’s metaphorical ‘iron room’ (for more on this, see below):

- 1978-1979: the Democracy Wall protests at Xidan in Beijing and the period of samizdat literature vs. the reaffirmation at the Third Plenary Session of the Party’s Eleventh Party Congress in December 1978 of the intellectual repression of the 1957 Anti-Rightist Movement, the introduction of the Four Basic Principles in March 1979 and the salvaging of Mao Zedong’s reputation and Mao Thought;

- 1986-1989: the student-led rebellion in favour of greater media openness and political reform starting in Shanghai in late 1986 and continuing until 4 June 1989 vs. anti-Western propaganda, attacks on ‘bourgeois liberalisation’ and the rise of patriotic education;

- 1999: the quest for religious/ cult freedom and growth of civil organisations during the decade vs. the repression of Falungong and restrictions on independent groups;

- 2008: the Tibetan Uprising and Charter 08 vs. the rise of Anti-CNN hyper-nationalism and a new phase of rabid anti-Western propaganda overseen by Xi Jinping; and,

- 2018-2020: the protests over the revision of the Chinese Constitution and fears of one-man autocracy, as well as protests related to the whistle-blower Dr Li Wenliang and the popularity of Fang Fang’s Wuhan Diary vs. the ‘People’s War’ against the coronavirus epidemic, including the further repression of dissent, including the silencing of Zhang Zhan, Ren Zhiqiang, Xu Zhiyong, Xu Zhangrun, Li Zehua and Chen Qiushi, among others. (For details, see Viral Alarm — China Heritage Annual 2020.)

- For more on these earlier ‘awakenings’, see 瞽 You Should Look Back, the introduction to Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium.

(Note: For the most part, the awakening of Hong Kong — in particular, during the protest movements of 2014 and 2019 — although a response to the actions of local satraps undertaken at the behest of Beijing, was semi-autonomous. For more on this, see the section Hong Kong Apostasy on this site. Since 1949, ‘awakenings’ on Taiwan have followed a trajectory of their own, even if Chang Lin-cheng 張麟徵, a testy retired political scientist in Taipei known as a staunch ‘re-unifier’, warns that ‘It’s high time Taiwan people woke up 醒悟’ to the fact that they are really Chinese and not merely a US pawn.)

Each generational awakening leads some of the newly aroused to learn about the insights and achievements of previous generations, often in exile. In many cases, however, the state has poisoned minds so successfully and corrupted perception so throughly that the past remains lost to the present. For more on this, see the chapter ‘Traveling Heavy’ in In the Red: on contemporary Chinese culture, 1999, pp.38ff in which I quote a writer who made the following observation about the post-June Fourth exiles:

‘With the passing of time, the exiles will gradually be lost in the crowd and may well end their days in obscurity. Of course, they will be able to live out their lives in a free and democratic society; but it won’t be theirs, for others have made the sacrifices that built it.’

A View from the Bridge

子曰:德不孤,必有鄰。

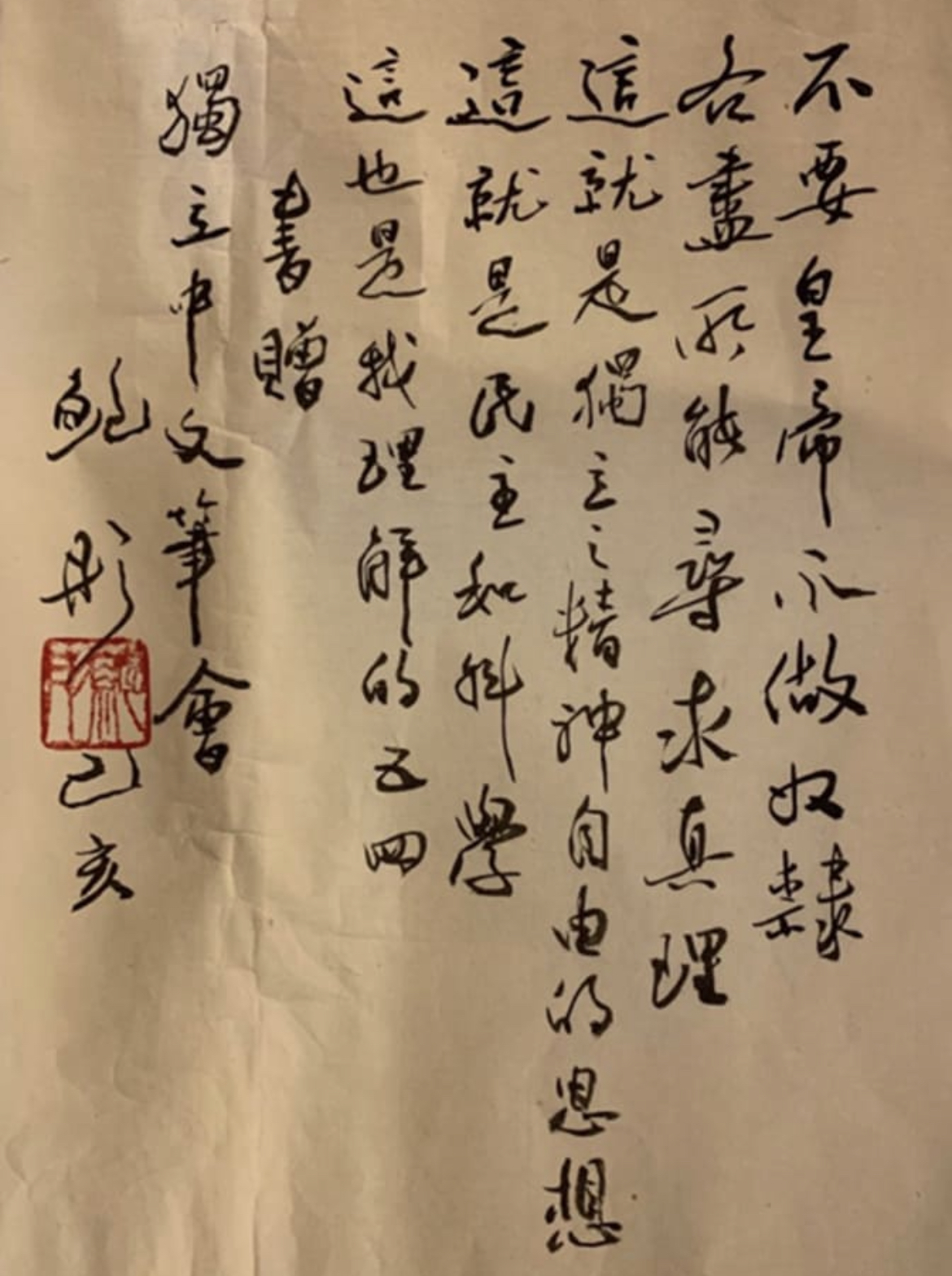

On 13 October 2022, a lone protester unfurled two long cloth banners on the Sitongqiao Overpass near the university district in Beijing. It was only days before the ruling Communist Party convened its twentieth national congress and the protester, who called himself ‘Peng Zaizhou’ 彭載舟, issued a call for rebellion summed up in pithy slogans:

不要核酸要吃飯,

不要文革要改革。

不要封城要自由,

不要領袖要選票。

不要謊言要尊嚴,

不做奴才做公民。

We don’t want COVID tests. We want to eat.

We don’t want Cultural Revolution. We want reforms.

We don’t want lockdowns. We want freedom.

We don’t want a Leader. We want the vote.

We don’t want lies. We want dignity.

We aren’t slaves. We are citizens.

Peng concluded his list of grievances and demands with an even more daring act of lèse-majesté:

罷課罷工罷免國賊習近平。

Refuse to go to class. Go on strike. Remove Xi Jinping, traitor to our nation.

Peng Zaizhou, whose real name is Peng Lifa (the sobriquet Zaizhou 載舟 was a pointed reference to an ancient adage: ‘the people are like water, they can either buoy or bury the power-holders’), attracted the attention of passersby to his banners with smoke billowing from a fire he lit in a garbage bin and a pre-recorded message broadcast on a loudspeaker set up on the overpass. Earlier that day, he had released an online action plan in which he called on Chinese citizens to protest against Xi Jinping en masse on Sunday 16 October 2022, the first day of the Party Congress. He accompanied the material with a long historical poem.

***

***

As Li Yuan wrote in The New York Times:

China’s censors went to great lengths to scrub the internet of any reference to the act of dissent, prohibiting all discussion and shutting down many offending social media accounts.

The slogans didn’t go away. Instead, they caught on inside and outside China, online and offline.

Encouraged by the Beijing protester’s extremely rare display of courage, young Chinese are using creative ways to spread the banners’ anti-Xi messages. They graffitied the slogans in public toilets in China. They used Apple’s AirDrop feature to send photos of the messages to fellow passengers’ iPhones in subway cars. They posted the slogans on university campuses all over the world. They organized chat groups to bond and shouted “Remove Xi Jinping” in front of Chinese embassies. This all happened while the Communist Party was convening an all-important congress in Beijing and putting forth an image of a country singularly united behind a great leader.

The aftermath of the Beijing protest “made me feel, for the first time, hopeful,” said an organizer of an Instagram account known as Citizens Daily CN, which posts photo submissions of sightings of anti-Xi messages. “In this era of oppressive silence, there’s anger in silence, hope in despair.”

— from Li Yuan, ‘A Lonely Protest in Beijing Inspires Young Chinese to Find Their Voice’, The New York Times, 24 October 2022

Within hours, Peng Zaizhou’s solitary protest was being compared to the solo rebellion of Xu Zhangrun, the Tsinghua University professor of jurisprudence who had published a lengthy critique of Xi Jinping’s rule in July 2018, which he followed up with an unsparing analysis of the unfolding coronavirus crisis in February 2020. Both men were hailed as 孤勇者 gū yǒng zhě, ‘lone heroes’:

章潤一文驚天下,是思想的孤勇者。

載舟點火天下驚,是行動的孤勇者。

Xu Zhangrun’s essay shocked China; he is a lone intellectual warrior;

The fire Zaizhou lit has left China shocked; he is a lone action warrior.

Xu and Peng share ‘a sublime madness of the soul’:

‘Reinhold Niebuhr wrote that “nothing but madness will do battle with malignant power and ‘spiritual wickedness in high places.’ ” This sublime madness, as Niebuhr understood, is dangerous, but it is vital. Without it, “truth is obscured.” And Niebuhr also knew that traditional liberalism was a useless force in moments of extremity. Liberalism, Niebuhr said, “lacks the spirit of enthusiasm, not to say fanaticism, which is so necessary to move the world out of its beaten tracks. It is too intellectual and too little emotional to be an efficient force in history.”

‘This sublime madness is the essential quality for a life of resistance. It is the acceptance that when you stand with the oppressed you get treated like the oppressed. It is the acceptance that, although empirically all that we struggled to achieve during our lifetime may be worse, our struggle validates itself.’

— Chris Hedges, ‘The Price of Resistance’

Truth Dig, 18 April 2017

A Note on Translated Voices

Since 1977, my writing career has involved an effort to introduce English-reading audiences to select Chinese voices. After my studies in the People’s Republic of China were curtailed in 1977, I spent some years working in Hong Kong. There my colleague Bennett Lee and I translated commentaries and political analyses jointly written by Lee Yee 李怡 and Liang Liyi 梁麗儀, a husband and wife team, and published as editorials in The Seventies Monthly under the name ‘Qi Xin’ 齊辛, a homophone for ‘a shared heart-mind’. We also translated The Wounded: New Stories of the Cultural Revolution, 77-78, which appeared in early 1979.

In the early 1980s, my part-time translation efforts focussed on the Cultural Revolution memoirs of Yang Jiang 楊絳, Ba Jin 巴金 and Chen Baichen 陳白塵 following which, in the mid 1980s, I became involved first in translating some of the oral history work of Sang Ye 桑曄 and Zhang Xinxin 張辛欣 and then in a book project titled Seeds of Fire: Chinese voices of conscience (Hong Kong, 1986). That was followed in 1992 by New Ghosts, Old Dreams: Chinese rebel voices, more work on the oral histories of Sang Ye, as well as on material published by the investigative journalist Dai Qing 戴晴. A wide range of voices also featured in my survey of the popular revival of Mao during the early 1990s, published as Shades of Mao: the posthumous cult of the Great Leader. In tandem with those efforts, I worked with colleagues in Boston on two film projects — The Gate of Heavenly Peace (1995) and Morning Sun (2003) — both of which feature a polyphony of Chinese voices. Over the years, I have been just as interested in discordant voices and those of Chinese officialdom, including those of such henchmen and handmaidens as He Xin 何新 and Wang Xiaodong 王小東, who featured in my 1995 essay To Screw Foreigners is Patriotic: China’s avant-garde nationalists.

Since its founding in 2017, China Heritage has introduced readers to the voices of protest surrounding the persecution of Xu Zhangrun and the fall of Hong Kong. After reading the following conversation between Li Yuan and Kathy (see below), readers are encouraged to (re-)visit Hong Kong Apostasy, a section in China Heritage that features some of the outspoken voices that were raised during the Hong Kong Uprising of 2019. In particular we recommend:

- Canny Leung Chi-Shan 梁芷珊, Like Water, Boiling Water, China Heritage, 15 August 2019

- Kitty Hung Hiu Han 洪曉嫻, How Dare You Hong Kong People Resist!, China Heritage, 18 August 2019

- Kitty Hung Hiu Han 洪曉嫻 and Lester Shum 岑敖暉, Freedom-Hi & #ProtestToo, China Heritage, 4 September 2019

- Concerned Hong Kong Citizens, For We are Like Olives, China Heritage, 6 September 2019

- Jason Wong Yiu-pong 黃耀邦, Voiceless, but Not Silent, China Heritage, 5 October 2019

As well as the following essays by Lee Yee:

- Young Hong Kong, China Heritage, 16 July 2019

- This is Who We Are — We Are Hong Kong, China Heritage, 22 July 2019

- Living and Learning in Hong Kong 2019, China Heritage, 29 July 2019

— GRB

***

A Voice from Young China

When I interviewed Liu Xiaobo in late 1986, he declared that ‘liberation for Chinese people will only come when there is an “awakening of individuality”自我覺醒 zìwǒ juéxǐng.’ (See 中國人的解放在自我覺醒——與個性派評論家劉曉波一席談, The Nineties Monthly 九十年代月刊, March 1987.)

‘Awakening of individuality’ among Chinese youth and intellectuals had been a central feature of the New Culture Movement and the May Fourth demonstrations during the 1910s, mentioned above. Activists with foresight or greater awareness — 先知先覺 xiān zhī xiān jué — believed that through their writings, teaching, speeches and demonstrations they were ‘calling on the people to awaken’ 喚醒 huàn xǐng mínzhòng and ‘rousing the world’ 醒世 xǐng shì.

Despite his own sense of engagement, Lu Xun, the emblematic writer of the age, felt the agonies of loneliness and sadness even when, ‘I used various means to dull my senses, both by conforming to the spirit of the time and turning to the past.’

‘Yet in spite of my unaccountable sadness, I felt no indignation; for this experience had made me reflect and see that I was definitely not the heroic type who could rally multitudes at his call. … Still my attempt to deaden my senses was not unsuccessful—I had lost the enthusiasm and fervour of my youth.’

In the preface to his first collection of stories, written in December 1922, Lu Xun recounted how he had sought both relief and a refuge in writing. His doubts and self-questioning continued:

‘Suppose there was an iron room with no windows or doors, a room it would be virtually impossible to break out of. And suppose you had some people inside that room who were sound asleep. Before long they would all suffocate. In other words, they would slip peacefully from a deep slumber into oblivion, spared the anguish of being conscious of their impending doom. Now let’s say that you came along and stirred up a big racket that awakened some of the light sleepers. In that case, they would go to a certain death fully conscious of what was going to happen to them. Would you say that you had done those people a favor?

‘ “But if a few awake, you can’t say there is no hope of destroying the iron house.”

‘True, in spite of my own conviction, I could not blot out hope, for hope lies in the future. I could not use my own evidence to refute his assertion that it might exist. So I agreed to write, and the result was my first story, A Madman’s Diary. …

— from Lu Xun, Selected Stories of Lu Hsun, translated by Yang Xianyi and Gladys Yang, Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, Peking, 1972

Lu Xun titled his collection 吶喊 nà hǎn, or Call to Arms. The expression that also means ‘to scream’ or ‘rail at the world’. 吶喊 nà hǎn has featured in Chinese protests ever since. ‘As for myself’, Lu Xun continued,

‘I no longer feel any great urge to express myself; yet, perhaps because I have not entirely forgotten the grief of my past loneliness. I sometimes call out, to encourage those fighters who are galloping on in loneliness, so that they do not lose heart. Whether my cry is brave or sad, repellent or ridiculous, I do not care. However, since it is a call to arms, I must naturally obey my general’s orders. This is why I often resort to innuendoes, as when I made a wreath appear from nowhere at the son’s grave in Medicine, while in Tomorrow I did not say that Fourth Shan’s Wife had no dreams of her little boy. For our chiefs then were against pessimism. And I, for my part, did not want to infect with the loneliness I had found so bitter those young people who were still dreaming pleasant dreams, just as I had done when young.’

***

In 1927, Lu Xun presented a lecture in Hong Kong called ‘Silent China’ 無聲的中國. In it he spoke of the ‘fearful inheritance’ 可怕的遺產 of China: the burden of the classical written language and its limitations. He called for the use of vernacular that could truly give voice to the aspirations of the Chinese. But Lu Xun knew better than most that language itself did not determine reality — though he did not live to see the fearful miscegenation of modern Chinese with its mangled European-ised syntax and vocabulary, classical affectation and the wooden parole that I have described elsewhere as New China Newspeak 新華文體. Towards the end of his talk Lu Xun said:

Youth must first transform China into a China with a voice. They must speak boldly, move forward courageously, forget all considerations of personal advantage, push aside the ancients, and express their authentic feelings. … Only an authentic voice will be able to move the Chinese and the world’s people; it is necessary to have an authentic voice so that we may live in the world with others. [trans. Theodore Huters]

The propagandists and socialist-nationalists of the People’s Republic would claim that they speak with just such a voice, and that Xi Jinping’s version of The China Story is the sole true, authentic version of China and account of the Chinese. … Clamorous public debate — circumscribed and self-censored discourse even at the best of times — has gradually been corralled. That is not to say that there is a dearth of noise or verbiage in the People’s Republic, or a lack of boisterous chatter on its global web, but the Storm and Fury is increasingly limited to the stentorian messages of the party-state and its loyalists, although sometimes they sound more like a threnody that repeats itself and reverberates like the death-bed message of the emperor in Kafka’s Great Wall of China.

— from G.R. Barmé, Living with Xi Dada’s China, 16 December 2016

***

A Lonely Protest in Beijing Inspires

Young Chinese to Find Their Voices

Li Yuan

While there has always been political dissent in China, the country’s Generation Zers are known for toeing the government line, both because they grew up in China’s most prosperous period and because the party is very good at using the internet and social media for indoctrination.

Now, though, some of them are experiencing a quiet political awakening, having grown unhappy about the government’s comprehensive censorship, the harsh “zero Covid” policy and the ever-tightening grip on society.

The vast majority of the young dissenters are having their first brush with political rebellion, which is prohibited in China and closely monitored by the authorities, even as a Chinese person living abroad. In doing so, they’re overcoming their fear of the repressive government, their political depression and their loneliness as political heretics in a society that espouses one leader, one party and one ideology.

As beginner protesters, they’re timid, scared and inexperienced. They are ashamed that they have to ask for anonymity in media interviews and even hide their identities from each other. … The risks are too high. But being part of the global anti-Xi protest movement empowers them.

By sharing the protest posters online, many people realized that they were not alone in their political thinking. “It comforts people and gives them hope,” said the administrator of the Instagram account @northern_square, an art student in the United States. The account has received more than 2,000 submissions from all over the world of sightings of anti-Xi messages. Citizens Daily CN said that by Sunday it had received more than 1,500 submissions of anti-Xi slogan sightings from more than 328 universities around the world.

— from The New York Times, 24 October 2022

***

Kathy and the My Duty Democracy Wall in London

An Interview by Li Yuan

Translated and Annotated by Geremie R. Barmé, featuring added and highlighted material

四通橋後,那些年輕的抗議者

不明白播客

一起探尋真理與答案

袁莉

29 October 2022

[For the Chinese text of Li Yuan’s conversation with Kathy, click here. — Ed.]

On the eve of the Chinese Communist Party convening its Twentieth National Congress in Beijing something unexpected happened. A protester hung two long banners on the overpass at Sitong Bridge in the Haidian District [in the northwest of the city] calling for the end of the government’s Zero Covid policy as well as appealing for freedom, democracy, and citizens rights. They included a demand that the party leader Xi Jinping be dismissed from office. After news of this incident flooded the mainland Chinese internet it was quickly suppressed. Many people who had forwarded the news or discussed it even had their Weibo or WeChat accounts blocked. What was surprising was that the protester’s slogans didn’t disappear and they spread like wildfire, or the proverbial ‘prairie spark’ [星星之火] that Mao Zedong had so famously written about in the 1920s. On the mainland there was even a new ‘toilet revolution’ [廁所革命, a reference to Xi Jinping’s campaign to clean up public conveniences] and the slogans were spray painted on the walls of toilets. Some people used airdrop to spread images and the message of the protester to strangers on subways. Many young Chinese students started posting messages about Bridge Man on their campuses and in the cities in which they were living. Online groups designed protest images that were distributed via Instagram using such accounts as @Northern Square and @Citizen’s Daily and called on people throughout the world to share the images of protests they had seen or taken part in.

I also had a chance to speak with a protester in Guangzhou who had used airdrop on their iPhone to send images of Bridge Man to fellow subway passengers. He said he’d already done it three times and apart from photographs of the incident he included material from Wikipedia as well as some further explanatory material that he’d stitched together after scaling China’s ‘Great Firewall’ and getting unfettered access to the Internet. He said that it was this way of arming people. [The expression he used was ‘授人以渔’ — rather than giving someone a fish to eat, you teach them how to fish for themselves.]

But who are these young people? Why do they persist in their protests even in the face of considerable personal risk? What were they thinking when they stuck up those posters? What did they encounter?

I was lucky to have come across Kathy, a Chinese student studying in London who was willing to share her experience with me. To protect her anonymity we have masked her voice.

— Li Yuan

***

Kathy: Hello.

Li Yuan: You’re living in London. Can you tell me when you learned about the incident at the Sitongqiao Overpass in Beijing on the 13th of October? What was your immediate reaction?

Kathy: Because of the time difference the events in Beijing happened during our day and, since I had been out all day, I only caught up on the news after getting home that night. My overwhelming initial reaction was absolute shock. It was unbelievable that something like that had actually happened in China. Then, I was overcome by a crushing sense of frustration and impotence: I simply couldn’t imagine that there was a courageous person like him in China today. How could I help him? What could I do to help protect him and his family?

Those are the emotions and thoughts that first ran through my mind. Then when I scrolled through my Instagram account I saw that [Chinese] students at campuses around the world were starting to put up posters [in support of Bridge Man]. I felt a real jumble of emotions. Like my online friends I’d initially been consumed by my emotional reaction and tearfulness, but then seeing all of those pictures … As I was unable to sleep that night, I just obsessively refreshed the screen on my phone. Each time there were more, newer pictures. I was sobbing. At one point I even opened my window and screamed out in frustration [吶喊 nà hǎn, one of the most charged words of protest in the Chinese language]. I can’t tell you how lonely and isolated I had initially felt, but [those photographs] were like a glimmer of light in the dark. I couldn’t believe it.

Of course, I knew I wasn’t really alone, but life had taught me many painful lessons and I’d learned to keep out of trouble and protect myself. I’d long ago realised that you shouldn’t confide in others. I hid my true thoughts and knew how to live undetected with my profound sense of loneliness. But now, seeing all those people suddenly talking to each other online, seeing photos of all the posters put up in the streets and at university campuses, I was moved to tears and felt like crying out to heaven: how could I have known that there were so many others like me scattered around the world? But where are you all? How can I possibly find you? How would I have ever been able to recognise you in the street?

[Note: The expression ‘to keep out of trouble and protect myself’ 趨利避害 qū lì bì hài is a widely used Xi Jinping-era catch phrase characterise by Peking University historian Qian Liqun as being ‘the base animal instinct’ of contemporary China. See Qian Liqun 錢理群).]

Pretty soon I decided on a plan though, truth be told, since this was the first time I was going to express myself publicly, I was very nervous. I had no history of protesting, no practice doing it and zero experience. But I thought: I am free to do this [since I’m overseas], so what possible reason could I have not to act? Still, since I hadn’t been in London very long and I didn’t have any no friends to talk things over with, at first I was pretty careful. Experience proved me right to be hesitant and I soon learned it would’ve been risky to discuss anything with the majority of Chinese students.

So, I only had my online friends to rely on, and they were very supportive. They told me that I was very courageous but also urged me to watch out. Some suggested that I should cover my face with a face mask and wear sunglasses so I could conceal my identity from other Chinese. Watch out, in particular, for the Chinese Students’ Association, they said, and don’t let anyone take your picture.

At 4:00am that morning, when I went downstairs to use the printer available in our block of flats, I really did feel like a thief in the night. I hadn’t worn a face mask in ages. Lots of other Chinese students lived there so, even though it was in the early hours, there were still a few hanging around. It all made me feel like a guerrilla fighter and I hid each page of my poster as it came out of the printer. Since it was the first time I’d used that printer in the common area and I wasn’t familiar with it or the computer that operated it, at the slightest hint of someone coming along, I quickly concealed what I was doing. It felt as though I was carrying a bundle of grenades and not just a few sheets of A4 paper.

I thought it’d be safer to wait until dawn before heading off to school. Of course, I was really nervous when I started putting up the posters particularly as it was rush hour and there were lots of Chinese students around. I was in such a state of anxiety that the moment I caught sight of a male Asian face, I got out of there. Once I’d made it to the safety of a nearby corridor I slowed my pace and pretended nothing had happened. As I was walking in front of him I was able to shake him off by ducking into a toilet. I waited until he’d gone before heading back to my task. This happened a few times, though nothing came of it. I was in such a hyper state of mind that I managed to keep up my guerrilla campaign for a few hours without taking a break.

Li Yuan: Where did you put up your posters?

Kathy: Mostly on the announcements boards in the main building on campus. Though I got it wrong at first and put some up in other buildings. That was around 7:00am. Then I got to work at the corridor in the busiest part of the school. Even though it was packed with people, I knew that’s where my posters would attract the most attention. At one point, I really was feeling very exhausted but I felt that I just had to press on and finish what I’d set out to do.

I was determined to avoid other Chinese students, though one Caucasian male student [Note: In the geographically confused style typical of Mainland Chinese, Kathy calls this ‘white male student’ 白人男生 a ‘foreign classmate’ 外国同学] approached me to offer a few words of encouragement. He told me that he’d read the poster and thought the [Sitong Bridge] protest was courageous. As soon as he left I went off to cry in a corner. I’d been on edge all morning and with my emotions all pent up like that I knew just about anything could set off a flood of tears. One minute I was in class listening attentively, the next I felt as though I was losing control. Then, after a moment, I’d be back listening attentively. I was in an extremely emotional state all morning. But, by lunchtime, I’d calmed down a bit because of the support and encouragement I’d received.

Later, when I was in touch with lots of people online I even saw that people were posting photos of my posters: it was proof that there was some support for what I was doing. Other people were also putting up posters, too. Various students responded online in a way that really made me appreciate the line: ‘No act of courage should go unanswered.’ All the responses touched me, in particular when people added their finger or thumb prints in red ink to my posters. When I shared this with ‘foreign students’ they didn’t get what it meant; even I didn’t have a ready explanation. It just seemed to be so obvious. When I saw them I just thought that everyone would understand what it signified: to me those fingerprints represented support; they meant that people were with me, that we were in this together.

Li Yuan: Why were you afraid of bumping into other Chinese students?

Kathy: I was scared that I’d be reported [to the Chinese embassy]. Though I’m overseas I have family back in China and I’m still a Chinese citizen — both are really serious concerns. Though, at the time, it sort of didn’t really occur to me that I might be reported, it was only later when people told me that I should be worried. I guess I was just generally pretty careless about that side of things.

As I was getting my posters ready in the early hours of Friday, friends online were warning me about a whole lot of things. When I’d told people that I really didn’t know whether a protest like this meant anything that night I was in a very agitated state of mind. But I honestly didn’t know. I had no grand plan to change the world or even to make things better, I was just responding to my own mood of hopelessness and anguish. I felt completely worthless and thought, if I could just go out and put up some posters to express my support, even though I was at the other end of the world, at least I’d be doing something to lessen my own pain and frustration.

Of course, I knew full well that by thinking like that I was being very indulgent and self-important. I also knew that my sense of guilt would persist. So, why did I want to do it? Well, after all, it was something I could do safety from my perch overseas. I knew that it meant nothing in comparison to what Peng Zaizhou had done. I also thought it was both ridiculous and pitiful when I heard the rumour that over 600,000 WeChat accounts had been blocked. Relatively few of us so-called ‘rebels’ actually had our accounts closed [Note: see Jay Zhuang, The Beijing protest that turned thousands into ‘digital ghosts’, The China Project, 31 October 2022]. That’s because most of us had internalised the rules of the game long ago: we all knew what could and could not be said online. Most of the people whose accounts were suspended this time around weren’t generally that interested in such things [as protest or dissent]. They didn’t know the ground rules so they ended up running head on into trouble. Most of us knew not to talk about such things on WeChat. We knew that as soon as something like that happened if you didn’t steer clear of it, they’d shut you down.

That I was so aware of how the game was played only made me hate myself even more. There is this guy [Peng Zaizhou] ready to give up his life and here I am worried about losing my WeChat account. That’s why I wasn’t as afraid of them reporting on me, though the simple truth was that I had no experience in protesting.

Although people online were constantly warning me about what might happen, including friends in China telling me to keep clear of other Chinese students, I really had no idea what kind of people any of them were. Or, to be more precise, I had no clue how they might be responding to this particular incident. You couldn’t predict nor prepare yourself for how people would react. That was a significant factor in the tension and anxiety I felt on that first morning. By the time I returned to school to put up more posters [in the afternoon] I’d really lost all sense of trepidation. I even gave up wearing the face mask and sunglasses. Anyway, I thought wearing sunglasses on campus just made me stand out. It would be seen as being very odd. Although my tactics remained those of a guerrilla insurgent, I was no longer going into the field in full kit.

Li Yuan: But you were still like a frightened rabbit, scurrying off as soon as you’d put up a poster.

Kathy: Exactly! Because I couldn’t use my finger nails, or it was too high to put the tacks into the posters. I was so nervous — my palms were all sweaty and I was constantly looking over my shoulder. Since Chinese students generally went around in groups the thing that most frightened me was my fellow countrymen and women.

Li Yuan: Can you talk a bit about the responses you got to what you posted about the coronavirus on WeChat back in 2020, when you were still an undergraduate in China?

Kathy: I had really been damaged by my experiences in 2020. It was an extremely emotionally challenging period and the aftereffects stayed with me for a long time.

I was on a short-term overseas study program when the virus broke out. I knew I was quite naïve and I had never gone through a ‘Little Pink’ phase of patriotic zealotry. For that I have to thank my family, as well as other factors — things that I still find hard to explain — but I’m not entirely sure why I am the way I am. I guess you’d have to say that it’s just a quirk of personality. There’s one thing for sure, though: whenever I dig through the past in my mind, I know I was never a patriotic zealot.

[Note: For more on ‘Little Pinks’ 小粉紅, see Namewee 黃明志 et al, ‘The Right to Know & the Need to Lampoon’, China Heritage, 18 October 2021.]

However, having said that I should add that I was both in the Young Pioneers [Communist Party organisation for adolescents] and was later a member of the Communist Youth League [which requires its members to demonstrate a certain level of political commitment and enthusiasm]. And there’s no doubt that I grew up under the influence of the collectivist ethos of the Party and was nurtured by formal patriotic education. In my discussions with my new circle of friends over the last few days this topic has often come up. We all talk about how our personal growth is the result of an agonising process of conscious self re-education. Bit by bit, we have all vomited out the poison that was fed to us over the years. I know that’s also why I feel I can truly empathise with many of the Chinese students around me [who remain under the influence].

[Note: For more on ‘Party poison’, see the section ‘Still Suckled on Wolf’s Milk 喝狼奶長大的’ in Zi Zhongyun 資中筠, 1900 & 2020 — An Old Anxiety in a New Era, China Heritage, 28 April 2020.]

Frankly I’m no fan of people who act all superior and treat [narrow nationalists] with condescending sarcasm — though, that’s not to say sometimes emotion simply does get the better of you and you simply can’t help yourself. I really wish I could tell them that I do honestly get where they are coming from and that I understand them. But then, I feel a profound sense of regret and sorrow. That’s because all of us are products of the same educational environment and we [that is, people in our online group] are deeply aware of how they’ve ended up like this [as hardline patriots], all the online friends I’m engaged with now share the same psychological dilemma.

The way I see it is that I’ve gone through two distinct phases, both of which have had an intense impact on my thinking. The first was when I went to university. Back then in all innocence I thought that, since we had successfully run the grueling gauntlet of entrance exams and were now all in the same big city at an institution that would give us a pretty good education, that’s to say we had so many shared experiences, we’d now have a lot in common and that meant it’d be easy to communicate with each other.

At the time I didn’t go online very much, though I hardly thought of myself as a ‘conscientious objector’ [反賊 fǎn zéi, that is, a rebel, or traitor. 反賊 fǎn zéi is an old term for insurgents opposed to imperial rule that has been revived in recent years]. — At the time I didn’t even know the expression 反賊 fǎn zéi, and I hadn’t ever participated in any of discussions or conversations of that kind. In my innocence I simply thought that, of course I was patriotic like everyone else, so what was wrong about thinking about these kinds of [taboo] issues? It was ridiculous to think that anything like that could get me into trouble. I was completely oblivious. Soon enough reality stepped in to teach me a lesson or two and gradually I came to realise that I simply couldn’t get through to or communicate with the vast majority of my classmates.

During my four years at university at most I encountered one or two people with whom I shared a common language. But then there was the fact that I had learned to be careful about the people I spoke to — I’d run into trouble a few times when I had just started college, so I was wary of socialising too much. After you’ve run into a brick wall a few times you naturally steer clear of situations in which you might get hurt. You see, whenever I clashed over certain issues with my fellow students, or when I heard them talking about things the way that they did, I took it personally. I always felt aggrieved as though I had been personally rejected.

Li Yuan: Can you give me an example?

Kathy: Like my own original circle of friends, many of whom I’ve now deleted from my social media accounts, or simply blocked. Anyway, I used to have lots of friends and on the surface it was all happy-go-lucky and they all seemed pretty cool. We knew each other from our offline lives and lots of them really seemed to care for and about me, at least in normal times and I’d never have thought we had any problems or they were a threat in any way. But on the day that [Speaker of the United States House of Representatives] Nancy Pelosi visited Taiwan [2 August 2022], it was as though my whole friendship circle was taken over by collective madness, everyone, but I mean everyone, reacted in the same robotic manner as if they had all been pre-programmed to flip out. They came out with all of this incredibly scary stuff and each and every one of them acted as though somehow the Taiwan issue was the most important for China and everyone expressed fervent hopes for a military resolution of the Taiwan issue so that the island could be forcibly integrated with China. None of them showed any hint that any of it was problematic in any way, or that they were actually calling for naked violence. It was as though all of a sudden we simply didn’t speak the same language. It was incredibly painful for me. If they were all nothing more than robotic androids with no independent will, I thought to myself, I’d have no problem cutting them off entirely. But that wasn’t the case, they were all individuals.

The coronavirus outbreak in 2020 had been an even greater shock. I guess it was the final straw, the thing that finally put an end to my naive belief that I could meaningfully communicate with other people. Up until then I had this fantasy that, having gotten into university and being able to study with all these other people, we were part of a very select and privileged group. But then, overnight, I realised that I simply wasn’t one of them at all. But at the time we were all overseas, something that was even more of a privilege; we had shown ourselves to be capable, and we had the support of our families to allow us to study there. As students who enjoyed this kind of privilege to live in a western democracy, shouldn’t we have some kind of fellow feeling and share a basic understanding of things. Shouldn’t we at least be able to communicate meaningfully with each other?

The pandemic broke out shortly after I arrived in the UK and what was happening in China really hit me hard. I was profoundly depressed. It was on a whole other level from how I feel about things today. Watching the news from Wuhan and China generally left me tearful. I started crying the moment I woke in the morning, I couldn’t focus on my studies and I couldn’t even face going to some classes because I was simply in a constant state of profound emotional anguish.

***

***

Li Yuan: What is it about what was happening in Wuhan that affected you like that? Could you remind listeners who might have forgotten those events.

Kathy: From the start it was clear that this was an unknown virus and that it was spreading like wildfire. Official state media insisted that there was no danger of human-to-human transmission, but that left you wondering what the blazes would happen to everyone now. After a while, however, there was clearly no way they could conceal the truth any longer. The epidemic really took off during Spring Festival in Wuhan. You were hearing about doctors in local hospitals who didn’t even have time to eat a bowl of instant noodles and there were all those pictures of stricken people screaming and protesting. They were like scenes from a war movie. In the streets, Wuhan looked as though it had been struck by a refugee crisis. No one had a clue what to do. At that point, you couldn’t even buy a face mask.

Being overseas at the time I didn’t even know how to think about what was happening then, despite all of this real-life drama, CCTV broadcast the usual New Years Song and Dance Extravaganza as though nothing was happening. I was dumbfounded by the stark contrast between those two realities. As for my personal circumstances, although I was overseas I was not naïve enough to think I could talk freely to people about what I was really thinking. As usual, I remained withdrawn and kept pretty much to myself, just as I had over the years. To keep myself safe, I made no effort to reach out or speak to anyone. Anyway, I really wasn’t in the mood to hear the kinds of things that people would probably come out with.

Just to go back to the posters for a moment. After that earlier experience, I realised that what I was most afraid of wasn’t being reported — although there was a considerable likelihood of that happening: I was scared of clashing with other people in person, of being confronted by what they said and forced to hear all that stuff. That’s what really disturbed me.

The fact of the matter is that I simply couldn’t bring myself to hate them all individually, even though most of the time it was hard not to despise them en masse. Yet I still feel that I really do care about them both as individuals and also as my compatriots. In part it’s because we’re all coping with being in a foreign country together. Although I’ve got a very good Taiwanese friend, the way we approach things is so different that actually they are as foreign to me as any other foreigner. Of course, they express their support for me, they understand and want to help me, but they are simply not the same as fellow Chinese; they cannot really stand alongside me as I would with other people from China. But, then again, my actual compatriots here say things to my face that I find appalling and incredibly hurtful.

Li Yuan: What are the things that you are afraid of hearing the most?

Kathy: Just by looking at them, or from the way that they carry themselves, I know they’d act as though they neither care about nor have any interest in politics. Of course, they’re at the more moderate end of the spectrum, quite unlike full-on patriotic extremists. So the hurt I experience as a result of their indifference is relatively minor, though their offhand manner still haunts me. I simply don’t know how to get through to them, how to change their minds or how to get people like that to engage with us meaningfully.

Li Yuan: Back in the day, were you able to share your reaction to the epidemic in Wuhan with anyone?

Kathy: I posted lots of things on my personal Weibo account to which my real-life friends paid some attention. Again, I’d emphasise my naïvety and simplistic view of things. Given what was happening with the virus I didn’t think it was such a big deal to express my views, nor did I worry about reposting messages by people who were seeking help under the trending topic of ‘Wuhan Virus’. I didn’t think I’d necessarily be helping anyone by doing so, but I didn’t know what else I could do. Of course, I convinced myself that reposting messages was not meaningless because, when we all individually decide to take action and word gets out as a result, I thought that there might be some kind of positive outcome. At least people like me were showing some support for those who were in desperate straits.

That’s also when things fractured. Or rather that’s when I realised the extent of people’s fractured views of reality. That was when I noticed that very few of my university classmates were re-posting any messages from or about Wuhan. Maybe they shared a bit of information about the situation, but it was not all that much. It was as though, although they were following the news, they had an inbuilt reticence about broadcasting or sharing it. I guess that what they did was better than nothing.

Gradually, a feeling of incomprehension and angst welled up in me and I began to feel contempt for them because they seemed so completely unmoved and uninvolved about the dire situation. I tried to get into their heads, to understand things from their perspective. This was something of a habit of mine, a thought process that I actually didn’t really like — but then again, maybe it was my long-term visceral response to things conditioned by the fact that I was a Chinese person from my particular environment — yet I couldn’t help being incredibly judgmental about everyone else. Sure, I appreciated them in all of their varied complexity, and I tried to be like them and adjust myself to the circumstances and say whatever was regarded as being appropriate for the context and I’d also second guess what they were thinking and how they approached things.

At the time I had the feeling that one of the main reasons that my fellow Chinese avoided talking about the virus was that things like that would somehow look out of place on their home pages, taint all the pretty photographs they posted and the upbeat accounts of the meals they ate outside and the entertainment they were enjoying — all those happy moments. That’s really what I thought was going on, both then and even nowadays as well.

By now I have accumulated quite a bit of experience, but back then these were all new feelings to me. It surprised me to realise how people really thought. Up to that point I had innocently presumed that it was only natural for everyone to respond to the situation the same way and to think about things like me. I wasn’t calling for the political system to be overthrown or anything like that, I just wanted to ask why so many people were suffering and find out what I could do to help out.

As for what my circle of friends and classmates were thinking at the time, well, I had a pretty good idea since I was expressing my views quite directly on Weibo and within my social circle. Though I had done so previously, the coronavirus epidemic of 2020 really set me off. I felt triggered and I said far more than I ever had before. I even got lots of unexpected responses.

I don’t know if people remember a person on Weibo by the name of Xu Kexin? She was a female university student who published a lot of very frank things about the epidemic under her real name. Online vigilantes outed her as a result of which she was subjected to a lot of abuse. I don’t know whether it was just in comments on her Weibo account or more broadly, but people dubbed her as being member of what they called the ‘Hate China Party’ [恨國黨 hèn guó dǎng, a broad term for ‘people who hate their country’, as opposed to those who love China, 愛國黨 aì guó dǎng]. From then on it was a popular term of abuse.

Because I didn’t think anything that Xu Kepin published was particularly ‘anti-China’, I felt outraged on her behalf. The expression ‘Hate China Party’ or ‘China Hater’ was absurd and completely off the mark. Only later when I published things on Weibo did I have to admit to myself that it looked as though I was also in the ‘Hate China Party’. I got lots of online messages as well as texts sent to my phone from people I didn’t even know. They warned me that I should delete my Weibo account immediately otherwise I’d get into trouble with my university and might not even be allowed to graduate. They told me that what I had been posting was completely beyond the pale. They seemed to be suggesting that what I said was ‘reactionary’ and that meant that I was a ‘reactionary’, too.

I wrote a lot about Fang Fang’s Wuhan Diary in my WeChat group because I was deeply impressed by her account, in particular as I saw with mounting trepidation how guided public opinion 輿論導向 was shifting with every passing day and how under the influence of the [party-state’s] gargantuan [propaganda] apparatus people were being brought into line, being devoured by the machine. Before my very eyes they were turning into bolts in the machine itself [like the model PLA soldier Lei Feng celebrated for his ‘bolt spirit’ 螺絲釘精神]. Most people I knew were deeply moved by Fang Fang’s on-the-ground account. We supported what she was doing and she was having an increasing influence as more and more people learned of what she was saying. Later on, increasingly numbers of people — most of whom I guess never read Fang Fang’s diary — fell under the sway of the official line. They’d parrot it robotically and probably even believed that the thoughts of the state were actually their own thoughts. They began spouting the wooden language of officialdom mechanically.

The kind of stuff that the Pinks or the people around me spouted was merely ‘the official line’, it wasn’t necessarily what they really thought. I often tell people that I don’t actually feel as though our views or political opinions are all that different because, in reality, I don’t think most people have consciously formulated political views of their own. They haven’t done so because they’re not interested. When you’re an empty vessel and have no strong individual will of your own yet you live in that kind of [propaganda-heavy] environment you can’t help being consumed by it. The system is simply too overwhelming to resist. So, when they come out with all of that stuff of course you feel that none of it is really them; they’re expressing acquired opinions that they’ve learned by rote. They might repeat them with fluency and conviction out of a deluded belief that they’re actually expressing a personal opinion.

So when ‘public opinion’ turned against Fang Fang and everyone started criticising her in increasingly harsh terms I felt a mounting sense of terror. I told my online group of friends that we simply had to express support for Fang Fang’s Wuhan Diary. How could you find fault with it? Though it wasn’t long before this, too, was unacceptable and I started getting messages from various people, including university classmates, as well as others who acted as though they were my elders and betters, who wrote in the most condescending tone as if they were in a position to ‘educate me’. They weren’t doing so out of concern that my opinions might get me into trouble; they wanted to lecture me about how misguided I was and that I had ‘ideological problems’.

Li Yuan: How did you respond to all of that?

Kathy: Oh, I simply deleted the lot! (Laughs) Truth be told, I was too scared to take them on or to argue back. I’m pretty much a coward when it comes to confrontation.

Liu Xiaobo on Self-worth

Sometimes, many young Chinese want to get political in a whole mess of ways, demonstrations and the like. But that’s all external to the self. In my opinion Chinese people will only be truly liberated when they learn to live for themselves, to take their own path in life. They need to think: Everything I am is because of me. … In reality, the reason things are like this now is due to a hive mentality. The young can’t prove their self-worth by themselves alone, they need the validation of the collective. If you act as an individual, even if you do something ridiculous, or things that are of no benefit to society as a whole, but they are things that no one has ever thought of or done, then I think your life will have been worthwhile.

中國很多年輕人有的時候要去干預政治、亂七八糟、參與遊行,這些東西都是外在的。我覺得,中國人真正的解放得等到每一個人只為自己而生存,他一輩子的生活道路只為他自己完成。他要建立這種信念:我的一切都是我自己的。… 實際上,產生現在的狀況還是一個群體意識。他感到自己在生活中不能靠自己,不能證明自己的價值,必須投入一個群體才能夠證明自己。但是如果你幹自己的,即使幹的事荒謬、對社會是毫無意義的事,但只要是別人沒有想出來的,沒有幹過的,你幹了,我就覺得這個人這一輩子就行了。

— from 中國人的解放在自我覺醒, 《九十年代月刊》,1987年3月

In the New Enlightenment decade of the 1980s years, Liu Xiaobo was understandably obsessed with self-actualization and personal fulfillment. When the mass Protest Movement of 1989 broke out in Beijing, however, while maintaining his rugged individuality, Liu also embraced such concepts as duty, virtue and collective obligation. Jailed as the figurehead of Charter 08, a collective action launched by intellectuals and social activists challenging Chinese authoritarianism, Liu died a martyr to a collectivist cause that championed the dignity of the individual. (See Liu Xiaobo on the Inspiration of New York, China Heritage, 31 December 2021.)

Li Yuan: When you were taking a break from putting up your posters [in support of the Bridge Man] did you catch what those other Chinese students were saying in response?

Kathy: Yes, it’s all been very educational. After what happened on Friday I went back to the question of whether putting up posters was a meaningful act. I realised that it was worth further deliberation. On top of that, what happened on Friday had given me a real boost because I found some like-minded new acquaintances, and even some real friends, with whom I’ve been able to join up with. I wasn’t alone. It was like a balm that soothed an open wound.

Over that twenty-four hour period — from Thursday through Friday — I had been in a state of constant and extreme agitation. One minute I’d be agonising in solitary despair and the next, when I looked at my Instagram, there was all this support from fellow Chinese students in America, Canada, Japan, Korea and countries all over Europe. I was so touched I burst into tears, though this time for good reason. That’s why I felt offline contact with people can be so incredibly important. If I could only speak to and get to know one person in real time, I felt as though I’d be able to get a grip and calm down. Then, when I discovered supporters among classmates at my school, people who were actually physically very close to me, my tears stopped because I felt as though my wounded soul had suddenly been offered comfort. After meeting up with those classmates on Friday night I went back to school to put up more posters, and I did so again the next day .

Come Monday, when I was at school by myself, I decided to do some more posting, though this time the wording of the posters was far more moderate. I really liked that new series of posters and I was very grateful to the friend who designed them for me. The slogans were:

‘Stand with Uyghurs, Tibetans, the people of Xinjiang, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Ukraine, Iran and all others who are repressed throughout the world.’

And.

‘We went food, we want love, we want pluralism, queer [sic].’

As a result, something really interesting happened. Maybe it’s because I was becoming a bit more practiced, or because of what I’d previously encountered, or due to the contact I had with those friends offline, but I had a new sense of courage. Anyway, I really hated wearing sunglasses and a face mask. I thought to myself, since I’m doing what I think is right I have every right to stand up as a proud and independent individual.

So, when I went back to school on Monday I didn’t hide behind a disguise nor did I avoid other Chinese students. I set to work sticking up posters in a corridor in the busiest part of the campus. I could tell there were people walking around behind me, many of them Chinese, but by now I really didn’t care. I must admit that I was a little nervous when a couple of them stopped nearby to take a look, in particular because they were male. Maybe I was even a little scared. I kept an eye on them since I had no idea what I’d do if they got violent and they were obviously keeping an eye on me, too. We stared each other down for thirty seconds or so and then they seemed to glance away even as they kept looking at the posters. I wondered whether this was their way of showing support, maybe they were even allies? So I kept looking over at them nervously, in part to see if they tried to rip my posters down. The standoff went on for a while. Then, suddenly, both of them slyly gave me the thumbs up. It was pretty comical, actually, since we were the only Chinese around.

As I said, I was used to ‘foreign students’ [that is ‘non-Chinese’] showing their support and offering encouragement — they’d praise my courage and give me a thumbs up and wish me the best. But the way those two Chinese students gave me the thumbs up was something completely different, it was a guarded and surreptitious gesture. Didn’t matter: it was very reassuring and so I smiled at them. One of them even hung around to have a chat. It was fantastic.

Like I said before, I’ve never totally lost my naïvety or maybe you’d call it my stupidity. So, I just opened up and asked him whether, since I had so many posters, he wanted to give me a hand. I had everything that was required, like tacks and scotch tape, and I said I could share them with him, if he wanted, that is. To be completely honest, I really had spent quite a lot of money on all that printing, but I was so anxious to find someone who got what I was doing to give me a hand that I made my offer straight up. He replied — and it’s not as though I doubt his story — that he was busy and he took off. Later, I realised that I’d probably been too pushy. Anyway, it was still a positive experience and it happened right when I most needed to take a break. I took a moment for myself opposite the café in the walkway where I’d been working. I wasn’t avoiding anyone and I held onto my cache of posters with my work materials laid out next to me.

A group of Chinese students walked past. They stopped and started exclaiming loudly as soon as they saw what was on the announcement board. I really wondered what they were carrying on about. Maybe they were excited and supportive, but that wasn’t it. Anyway, I still found it to be pretty odd since they looked like the kind of people who’d probably be in favour of my message. I just stood there real chill, though I must admit that I nearly went over to say hello. I was right behind them and though they would have immediately caught sight of me just by turning their heads, they acted as though I wasn’t there. Go figure.

I’m glad I didn’t make an approach since, after they’d nattered among themselves for a while, I heard one of them suddenly splutter: ‘It’s a disgrace!’ Then the rest chimed in, agreeing loudly. They all went on that it was such a loss of face demanding to know who had the gall to do such a thing? Then, one of them blurted: ‘People should know not to air dirty laundry in public.’ That’s exactly what they said, really. The rest then parroted that old line like half a dozen times aggressively agreeing with each other in really loud voices. Whenever I tell this story to my friends they respond by asking: ‘What exactly do they mean by dirty laundry?’ Right? It’s like I said earlier: it felt like it was a line that they’d learned to parrot. Of course, they’d internalised the script they had been fed. Who knows, they probably even believed what they were saying.

I really became furious when they started discussing among themselves whether they should tear the posters down. Even though I was outnumbered I immediately started psyching myself up for a confrontation. If they made a move on my posters I’d take them on. Even before I had plucked up the courage to say anything, however, they suddenly scampered off. You see, as soon as one of them suggested they tear the posters down, and although they started egging each other on, they were becoming increasingly anxious. Someone said: ‘Maybe it’s not such a good idea. We are at school, after all.’ That put an end to the playacting and they rushed off.

Li Yuan: I bet they wouldn’t really have dared tear them down.

Kathy: That’s right. It was an important bit of information for me because it bolstered my resolve as far as dealing with other groups of Chinese students. It went like this: If I was there alone most passersby wouldn’t hang around for too long, maybe they’d stop to take a photo or two, though I had no way of telling whether they were doing so to collect information or not. I preferred to think that the people who stopped to take pictures were showing support. But, if they came in a group, things tended to be more sketchy. They’d gather around and get into a discussion. Various groups were like that. One in particular seemed very worked up, but when I listened in I could tell that they were just bullshitting and coming out with things like: ‘Oh, that thing at the overpass. Yeah, yeah, I know that. I saw something about it.’ ‘Yeah, I’ve seen that things like these posters have appeared at other schools.’ ‘So, it’s even happening at our school.’ For them my protest posters were nothing more than a passing curiosity, a momentary diversion.

I really didn’t get it: since you know what this is about and you are overseas, it shows that you know what happened on Sitong Bridge [and what it means]. Yet they all made out as though they didn’t understand what it was all about and that they weren’t interested in knowing more. It was as though none of it had anything to do with them. Once they start snapping pictures, one of them would invariably say: ‘Better be careful not to get anyone in your shot. Before you know it, Public Security will be on your case.’ To them it was all just some kind of joke.

Li Yuan: Even when they’re all in London.

Kathy: That’s right. After joining in the joke they’d move on. Two or three groups were like that. From my observations that day I get the impression that those types were against what we are doing. They might be Little Pinks, or part of a large group of official Chinese students who were studying overseas. They weren’t prepared to post anything up there themselves to attack us, nor did they have the gumption to tear our posters down. At most they’d probably just report us. The worst would be when they scribbled ‘FAKE’ in big letters on a poster. To me, they were no better than the Chinese police who were always tamping down so-called rumours.

Li Yuan: Yup, ‘fake news’.

Kathy: For them reality doesn’t exist, there is no story here, no logic to what is happening, no deeper meaning, no glaring evidence of anything untoward. All they wanted to do was label our posters with that one word as a way of tell everyone that the posters were reporting baseless rumours.

***

The Woke Strategy of Wang Zhi’an

The journalist Wang Zhi’an (王志安, 1968-), formerly a prominent journalist with Central China TV and now in self-imposed exile in Japan where he hosts a news analysis channel on YouTube, is a gradualist (see 王局拍案). In an interview broadcast by Radio Free Asia, Wang said that the quixotic protest of Bridge Man was of little significance. He yearns to be a journalist back in China, a country that he describes as being a veritable goldmine of stories. To pursue the truth by reporting on lived Chinese reality Wang believes he could ‘nudge people towards a more awakened state’:

I don’t belong to any group or faction. I want to focus my energies doing some work in the media. Frankly, I’m not interested in any of them — reformers or revolutionaries. I don’t think the revolutionaries can ever succeed and there’s not much of a future for reformers, either. In my opinion, just about the only thing you can do in a place like China is nudge people towards a more awakened state. The greatest value in my kind of work in broadcasting is to show people what is really going on and through that demonstrate what needs to change and how things might change. So, I don’t regard myself as being anti-Communist, or anti-Party, for that matter. I’m against an inequitable social system and unfair public policies.

我認為我什麼派都不是。我只是希望通過我自己的努力,做一點媒體的工作吧。我對那個革命派改良派我都不感興趣,說白了啊。因為我覺得革命派你也成不了,改良派反正也沒有什麼太大的前途。在中國這樣的一個社會里,能做的我覺得就是推動老百姓覺醒,我自己的看法。如果我傳播的真相,能夠讓他們意識到,這個社會需要改變應該怎麼改變,這是最大的價值。所以我認為我不反共,我也不反黨,我反對的是不合理的社會制度不合理的公共政策。

— from 王志安:我對革命派改良派都沒興趣 我能做的是推動百姓覺醒,《亞洲自由電台》,2022年11月1日

***

Li Yuan: The Sitong Bridge Incident occurred shortly after you arrived in London and you took it upon yourself to carry out a poster campaign. Then you joined a group on Telegram called ‘London My Duty Democracy Wall’. Can you tell me why you decided to join that group?

Kathy: Actually, my thought process was pretty simple. As people know from what I’ve said on my social media accounts, overall I’ve been pretty lucky. Because I took action fairly early on I was able to make some friends in the group, fortunately for me that’s translated into meaningful and supportive friendships offline, too.