Spectres & Souls

The following essay is Part Two of ‘The Fog of Words: Kabul 2021, Beijing 1949’ and the Prologue to ‘The Xi Jinping Restoration’. It should be read in conjunction with ‘Prelude to a Restoration: Xi Jinping, Deng Xiaoping, Chen Yun & the Spectre of Mao Zedong’ (China Heritage, 20 September 2021). We bookend our consideration of engineered ignorance in China with two works by Namewee (Wee Meng Chee 黄明志, 1983-), a popular Malaysian hiphop artist and lampooner.

Special thanks to Reader #One for alerting me to the release of Namewee’s ‘Hearts of Glass’, as well as for catching a number of typos in the final draft of this chapter.

This is part of ‘Over One Hundred Years’, a series of essays commemorating the centenary of the Chinese Communist Party in China Heritage Annual 2021: Spectres & Souls.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

18 October 2021

***

The Right to Know

The Need to Lampoon

Geremie R. Barmé

Chinese Lessons for the Taliban

On 22 August 2021, as Taliban forces extended control over Kabul, Namewee (Wee Meng Chee 黄明志, 1983-), a Malaysian hip hot artist and film-maker known for his parodies, both written and musical, and for serial offense to mainstream Chinese zealotry, published ‘Eight Suggestions for the Taliban’ 給塔利班八條建議 on his Weibo account. In translation they read:

- Shut down access to pernicious Internet services like Facebook, YouTube and Google thereby making it impossible for your people to maintain any contact with the outside world;

- Establish your own online media platforms and develop news outlets and social media apps. Over time, having your own official news services will allow you to realign peoples’ minds so much so that they will automatically regard all external criticisms of your regime as the handiwork of insidious foreign forces. They will dismiss criticism as nothing more than fake news and not worth wasting their time on;

- Set up a massive portrait of your leader outside the Presidential Palace. Plaster the streets with political slogans and introduce brainwashing classes in schools so young people will be instructed as to the greatness of the leader;

- Encourage select individuals to scale over your great firewall to engage in verbal warfare on foreign Internet sites. The moment anyone criticises you your online agents can flood the space with protests about it all being nothing more than ‘insults directed at Afghanistan and its people’. They will denounce whoever posted such criticisms as ‘anti-Afghani slime’ who should just fuck off and die;

- On National Day, be sure to spend up lavishly so you can invite a clutch of foreigners willing to sing patriotic favorites like ‘Ah, Afghanistan!’ and ‘Without the Taliban there would be no new Afghanistan’ during the celebrations;

- Lock up people who voice dissatisfaction with your regime, but make sure that when you address foreigners you don’t call the place you lock them up a prison. Also, make sure to detain and re-educate anyone who shows signs of independent thought. Then, invite the media to film the prisoners, who have been trained to show how happy they are. Also, make the inmates plant crops of watermelons that can be harvested and sold for hard currency;

- Produce reams of patriotic movies for the masses, things like ‘Warrior Afghani’ and ‘Warrior Afghani 2’. It’ll help you convince your people that yours is a mighty nation and that all foreigners are bastards; and,

- Pay some of your most popular online influencers to make video clips like ‘Shocking America!’, ‘Russia Is Worried’ and ‘I’ll Never Regret Being in Afghanistan’ that can be promoted locally as well as posted online overseas … …

— trans. Geremie R. Barmé

Namewee’s Weibo account was deleted, as was his post, but not before the Eight Suggestions were widely circulating on China’s ‘Red Net’.

A Curtailed Emancipation of Minds

In the conclusion to Part One of ‘The Fog of Words’ I mentioned some of the casualties of the Chinese Communist Party’s near century-long war on history and observed that it is ‘the citizens of China who, as a result of the Party’s tireless war, are denied the right to know, to discuss openly and interrogate freely their history, to revisit the past from new angles and in new ways. The mind-boggling fog of words that is generated by this protracted war also frustrates those who seek to understand more than the confabulated official China Story.’

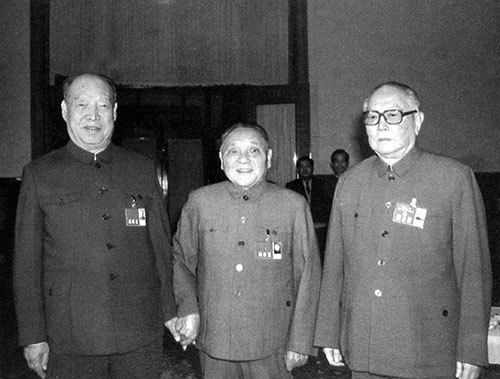

The policing of the past and official Chinese ‘historical nihilism’ is a prominent feature of the Xi Jinping Restoration (2012-), however, it is important to remember that the Communist Party’s war on the past was also central to all of the administrations of Xi’s predecessors. Even though the era of Deng Xiaoping (c.1978-1989) began with an unprecedented, albeit carefully circumscribed, expansion of the ‘right to know’, transitions to the successor ruling duopolies of Zhao Ziyang-Li Peng, Jiang Zemin-Li Peng/ Zhu Rongji, Hu Jintao-Wen Jiabao and Xi Jinping-Li Qiang were marked by restrictions on the right of Chinese people to know, whether it was about their past, the society they actually live in or the goings on of their political masters and the cloaked movement of capital.

Following the death of Mao Zedong in September 1976, the ‘right to know’ 知情權, or the right of citizens to have access to information, did, however, play a central role in the undoing of the bloody legacy of the High Maoism that held sway roughly from 1956 to 1976.

I first encountered the term ‘right to know’ in the summer of 1977, just after I started working in the editorial department of The Seventies Monthly in Hong Kong. For the previous three years I had studied at Maoist universities in Beijing, Shanghai and Shenyang and now I was soon shuttling between work in the British colony and visiting friends, buying books and learning about the post-Mao world in Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou. Having studied arcana related to the ‘Ten Great Lines Struggles’ 十次路線鬥爭 during which leftist and rightist political deviations were quelled by ever-victorious Mao Zedong Thought, and being schooled in the Eight Major Ideological Victories of Mao Thought on the literature and arts front, I was in a good position to see how the ridiculous edifice of Party history crumbled in places while essentially remaining unassailable.

Along with Lee Yee 李怡, our editor-in-chief, I followed daily news reports from Beijing detailing the reappearance of Deng Xiaoping and the fraying of Mao-era Communist Party dogma. The official media also reported, initially in dribs and drabs, and then in a tsunami of information, stories about the sudden reappearance of people who had long been thought to have died or been killed during the mêlée of the previous decades. There were also solemn obsequies for those worthies who had simply not made it. Veritable libraries of banned books were reprinted (just as now-illicit Maoist publications were pulped) and crammed the shelves of Cosmos Books 天地圖書, the bookstore appended to our basement editorial department, and outlets throughout the city; outlawed ideas, too, were tentatively aired and then more openly debated; even select episodes in Party history were deemed to be worthy of re-assessment.

As intoxicating as the de-Maoification years of 1976-1981 were, however, that era was hardly free from the firm guiding hand of the Party’s ideologues and propagandists. Behind their doleful guidance were re-habilitated cadres like Deng Xiaoping and his cohort, the men and women who had founded the People’s Republic along with Mao and their purged comrades, and in whose interests they now strove to validate and continue their life’s work.

A short-lived period of unregulated popular expression — the Democracy Wall at Xidan in Beijing (November 1978-November 1979) — was inevitably quelled when voices of dissent became too loud. At the time, I guessed that would probably be the case when I read ‘Do We Want Democracy or a New Autocracy’ 要民主還是要新的獨裁, a big-character poster posted on the wall in March 1979 by someone called Wei Jingsheng. (Wei was soon detained on trumped up charges and later sentenced to fifteen years in jail.)

The closing down and eventual bulldozing of Democracy Wall, marked, symbolically at least, not just the quelling of unruly protest, but rather the start of a protracted people’s war fought over the right to know. It is a conflict that continues unassuaged to this day. Of course, the Party preemptively claimed victory in its history wars as early as December 1978, first during a month-long work meeting and then at a plenary session of the Party that would later be celebrated as the starting point of the Open Door and Economic Reform Policies. During those wide-ranging meetings, even while he and his elderly comrades encouraged the nation to ‘look to the future’, Deng et al trained an unforgiving gimlet eye on the (and their) past. The harsh Party traditions of the Yan’an era (1937-1947) were reaffirmed, as were the achievements of the 1950s. From the starting point of the economic reform era, these crucial decisions would limit the extent of possible reform and underpin the ebb and flow of purges and ideological policing that have characterised post-Mao life in China.

Key Party slogans reflected the limits of change. The title of Deng’s closing address to the December 1978 Third Plenum of the Eleventh Party Central Committee may have been ‘Emancipate the mind, seek truth from facts and unite as one in looking to the future’, but in it he flag-posted the territory of ideological emancipation. The Party spoke of its approach as one that would 撥亂反正 bō luàn fǎn zhèng、正本清源 zhèng běn qīng yuán, ‘restore order in the face of the chaotic political excesses [of the recent past] by returning to the correct path [of an even more distant past] and ‘to set things right again and allow the source to run pure’. Other slogans recast two well-known set expressions for contemporary use. They were 承前啓後 chéng qián qǐ hòu、繼往開來 jì wǎng kāi lái, both of which emphasised the importance of inheriting the best of past practice as a way of building a better future. Even ‘Seek Truth From Facts’ 實事求是 shí shì qiú shì, the vaunted slogan of so-called ‘pragmatists’ like Deng Xiaoping, had its origins in the ideological headiness of the Yan’an era. Anxious to see economic change as the forerunner to fundamental societal and political change, many people regarded the revived slogan as exemplifying a fundamental change in Party thinking; in reality it reflected the dual nature of the reform era — economic change and adaptive Party hegemony. The slogan, like the Yan’an period itself, is also an inspiration during the Xi Jinping Restoration.

Yet these were not merely slogans for they were a decoction of a political and social temper that, since the late 1970s through the early 1980s, found expression in a nostalgic mood for the achievements of the 1950s. Ironically, while many recalled the seemingly simpler, happier days of that era, even though many had suffered the policy betrayals of that era, the celebrated reforms in the countryside and in industry and business starting in the late 1970s which offered a measure of autonomy to key actors in the economy, were for the most part only possible because Party leaders were consciously, if trepidatiously, overturning some, but hardly all, of the harsh policies that it had so vigorously pursued in the early years of the People’s Republic (for details see the ‘Chronology of Perfidy’ in ‘The Fog of Words’). If one was paying attention, one could make out the features of China’s autocratic future even as reform seemed to conjure up more winsome possibilities.

At the time, acute observers like Simon Leys saw the paradox at work:

‘For instance, when, in 1979, the “People’s Republic” began to revise its criminal law, there were good souls in the West who applauded this initiative, as they thought that it heralded China’s move toward a genuine rule of law. What they failed to note, however — and which should have provided a crucial hint regarding the actual nature and meaning of the move in question — was that the new law was being introduced by Peng Zhen, one of the most notorious butchers of the regime, a man who, thirty years earlier, had organised the ferocious mass accusations, lynchings and public executions of the land-reform programs.’

***

***

What is relevant to understanding the present era of Restoration, about which more will be said below and in subsequent essays, is that despite radical policy adjustments and impressive innovations that allowed the economy to boom and society to evolve, at no point in 1978 or 1979 did the Communist Party negate in any significant way its core ideology, that is the body of ideas, not to mention institutional practices born of them, that evolved during the Yan’an era (mid 1930s to late 1940s) and subsequently in the 1950s.

Thus, in 1978, regardless of promises that the wrongs of the past would all be righted, a purge that devastated the intellectual, professional and cultural life of China, and stymied labour activism for over two decades, was once more deemed by the Party to have been entirely justified, even if it had gotten somewhat out of hand and proved to be ‘too broad in scope’. Similarly, even as various individuals who had been denounced and silenced in the early 1950s were formally ‘rehabilitated’ — that is had damaged reputations salvaged and emoluments restored — overall the historical importance and impact of the draconian Stalinist-like policies of the era were reaffirmed, and they are still celebrated.

As Deng Xiaoping himself declared in March 1980: ‘up until 1957 Comrade Mao Zedong’s leadership was absolutely correct’. It was a statement that was less about Mao, the leader whose mummified corpse was on display in a crystalline sarcophagus in Tiananmen Square, and more about validating Deng and the surviving cohort of Party leaders who helped Mao formulate and implement the policies that had devastated the nation for three arduous decades.

The Closing of the Chinese Mind

As we noted in ‘The Fog of Words: Kabul 2021, Beijing 1949’:

‘1956-1957: The Hundred Flowers Campaign that initially licensed the leaders of former political parties as well as intellectuals, students, writers, media professionals, cultural figures and workers to criticize the Party’s “work style” (that is, its autocratic ways) led to a large-scale purge when Mao realized that workers in key industrial cities were on the point of rebelling against the Party’s heavy handed and exploitative rule. In the following months, Deng Xiaoping, who was given oversight of the logistics of the purge, engineered the exile of over 500,000 men and women to distant locales and labor camps.’

In 1957, as the Communist Party pursued what was known at the time as its Second Rectification Campaign (the first, launched in 1942 by Mao in Yan’an, is discussed at length in our series Drop Your Pants!), the Party announced six guiding principles that would serve to encourage people to give voice to their concerns and complaints about the self-rewarded privileges and autocratic ways that were a feature of its rule. People from all walks of life, it was announced, should feel free to:

- Speak up without hesitation if they had complaints; 知無不言

- Be allowed to say everything they wanted to, 言無不盡

- Not be condemned for what they say. 言者無罪

On their side, Party cadres were to:

- Listen to all criticisms and take heed, 聞者足戒

- Reform all errors that were uncovered, and 有則改之

- Work to improve constantly regardless. 無則加勉。

In July 1957, Mao summed up the aim of this great airing of public discontent that was something of a dialectician’s dream, not to mention being a logical absurdity, for it was to:

‘Foster a political environment that was centralised yet democratic, disciplined yet free; that forged a unified will while at the same time allowing for a sense of individual relaxation, in short, one that was both vital and lively.’

造成一個又有集中又有民主,又有紀律又有自由,又有統一意志、又有個人心情舒暢、生動活潑,那樣一種政治局面。

The resulting outpouring of discontent regarding of a myriad aspects of Party governance, however, was such that over 500,000 men and women (some estimates go as high as one million) from various backgrounds were condemned for engaging in what would be deemed to be a ‘frenzied attack on the Party’ 瘋狂進攻. Mao declared that the protests were actually part of a heinous plot by ‘Rightists’ and bourgeois elements who were determined to overthrow the government and replace it with some sham pseudo-democratic, market-driven regime. Acting on instructions from Mao and the Politburo, Deng Xiaoping oversaw a devastating purge of the nation’s intellectual and cultural life.

The result was the intensification of a policy of ‘unknowledge’ or ‘agnotology’, that began with the first cultural purge of 1950 and which, reaching new heights during the Socialist Education Campaign of 1964, would create a national policy of what came to be known as ‘ignorance education’ 愚民教育, in other words engineered ignorance.

Twenty years after the devastation of 1957-1958, when the Party reluctantly, and in desperation, directed its energies away from ceaseless internecine political warfare towards economic reform, the vast majority of the condemned innocents of 1957 were exonerated. However, a small handful of unredeemable ‘Rightists’ would remain under a cloud, as they do to this day, and their crimes against the Party were held up as proof that the original purge, and Deng Xiaoping’s role in helping close the Chinese mind, had been justified, timely and urgent.

To validate the repression of intellectual freedom in 1957 (and to justify the anti-intellectual campaigns of 1983, 1987 and 1989), the Party decided that the devastation was justified because five men had expressed anti-Party sentiments (even if they had reluctantly spoken up at the urging of the Party and had couched their remarks in mild terms). As Deng claimed in 1980:

‘The necessity for the anti-Rightist struggle of 1957 should be reaffirmed. After the completion of the socialist transformation, there was indeed a force — a trend of thought — in the country that was bourgeois in nature and opposed to socialism. It was imperative to counter this trend. I’ve said on many occasions that some people really were making vicious attacks at the time, trying to negate the leadership of the Communist Party and change the socialist orientation of our country. If we hadn’t thwarted their attempt, we would not have been able to advance. Our mistake lay in broadening the scope of the struggle.’

— from ‘Talk with some leading comrades of the Central Committee’, 19 March 1980

To repeat the point: the fateful deliberations at the Third Plenum in late 1978, along with a re-affirmation of those policy choices in the Party’s ‘Resolution on Certain Questions in the History of Our Party since the Founding of the People’s Republic of China’ in July 1981, and again in early 1992 (see ‘Prelude to a Restoration: Xi Jinping, Deng Xiaoping, Chen Yun & the Spectre of Mao Zedong’), doubtlessly transformed China’s economy, but they were in many ways of a piece with policies that had been instituted in the early 1950s that continue to stunt the country’s political, social, intellectual and cultural evolution. During the Xi Jinping Restoration, the long shadow of that past darkens the lives of men and women of conscience, social activists, cultural creators, thinkers, academics, students and citizens from all walks of life.

In November 2012, Xi Jinping led members of the Politburo Standing Committee to see ‘The Road Toward Rejuvenation’ exhibition at the National Museum of China. They had all just been elevated at the Seventeenth Party Congress and Xi had been selected Party General Secretary. In the remarks that he made at the museum Xi used the keynote slogan of December 1978 to adumbrate his tenure: 承前啓後 chéng qián qǐ hòu、繼往開來 jì wǎng kāi lái. As we noted in the above, both mean to inherit the best of the past as a way of building a better future. However, we have previously argued that the cage of autocracy condemns its inhabitants to rely repeatedly on the remedies of the past to deal with contemporary problems.

The Unappeasable and Their

Hearts of Glass

‘So sorry to cause offense

Hurt your feelings, your self-esteem

Is that sound your hearts of glass

Breaking into little bitty pieces?’对不起/伤害了你/伤了你的感情/我听见有个声音/是玻璃心碎一地

— Namewee, ‘Hearts of Glass’, 15 October 2021

Following the mass Protest Movement of 1989 and its bloody denouement on June Fourth, the Communist Party launched a nationwide re-education campaign. Although targeted at the educable young it also attempted to impose a strict ideological framework on the population at large. The ‘patriotic education campaign’ was in many respects similar to the national brainwashing pursued in the name of Party-legislated patriotism in 1951. Implemented during what we have called the Counter Reform years of 1989-1992, patriotic education and re-education have been a central pillar of Party rule for three decades. State education, popular propaganda and commercial zealotry have functioned in tandem to ‘manufacture ignorance’.

In a public lecture presented in Singapore in March 2015, Chen Danqing (陳丹青, 1953-), an artist and critic known for his outspoken insights, observed that:

‘These days people are pretty much oblivious to the fact that they live in a state of officially engineered ignorance [被愚民], and they even don’t care. Ultimately, an ideal situation is achieved whereby people dumb themselves down; they consciously make themselves more stupid.’

人民差不多已經不知道他們被愚民,他們不在乎被愚民。最後,簡直是出神入化,就是民開始自愚,自己愚自己。

— from Chen Danqing, ‘Mother Tongue and Motherland‘

陳丹青,《母語與母國》

As I observed some two decades earlier:

‘As the children of the Cultural Revolution and the reform era come into power and money, they are finding a new sense of self-importance and worth. Some of them are resentful of the real and imagined slights that they and their nation have suffered in the past, and their desire for strength and revenge is increasingly reflected in contemporary Chinese culture. Unofficial culture has reached or is reaching an uncomfortable accommodation with the economic, if not always the political, realities of the mainland. As its practitioners negotiate a relationship with both the state in all its complex manifestations and capital (often, but not always, the same thing), national pride and achievement act as a glue that further seals the pact. The patriotic consensus, aptly manipulated by diverse party organs, acts as a crucial element in the coherence of the otherwise fragmented Chinese world; timely exploitation of it in the public realm can also lead to political and commercial rewards.’

— ‘To Screw Foreigners is Patriotic: China’s avant-garde nationalists’,

The China Journal, no.34, (July 1995)

***

The Xi Jinping Restoration champions a formidable new era in Chinese agnotology. As we have indicated, ‘mass stupefaction’ 愚民 has featured throughout the history of the Chinese People’s Republic, having reached dizzying heights during the Cultural Revolution era. What supports the Party’s drive for post-1989 self-induced ignorance, a state further exacerbated since 2012, is the celebration of virulent sentiment, the glorification of intellectual self-castration and the willful rejection of information and knowledge.

In his mock ‘Eight Suggestions for the Taliban’ with which this essay began, the artist Namewee lampooned media policies pursued by the Xi-era Chinese authorities. We conclude our prologue to The Xi Jinping Restoration with another work by Namewee, ‘Hearts of Glass’ 玻璃心 (aka ‘It Might Break Your Pinky Heart’), a collaboration with Kimberley Chen Fang-yu (陳芳語, 1994-), a successful Australian singer, actress, and model based in Taiwan, that was released on 15 October 2021.

Namewee’s puce-suffused ditty is a playful, innuendo-laden mockery of China’s unappeasable, triumphalist and xenophobic ‘Pink Culture’ and its champions, known as ‘pinkies’ 小粉紅, aka ‘little punks’, or what I think of as ‘puce punks’, and it riffs on the cliché — ‘You have hurt the feelings of the Chinese People’ 你傷害了中國人民的感情 — a tired formulation of high dudgeon.

The song poked fun at what is known as ‘Chinsulting’ 辱華, that is behaviour, statements and actions that self-righteous Mainlanders deem to be unacceptable and decry with spittle-flecked hysteria. As the Taiwanese singer Chen Chia-hsing 陳嘉行 observed when he applauded Namewee’s spoof, as someone born in Taiwan ‘being alive is a Chinsult too… If you want to be a free person, you will inevitably Chinsult, and as time passes, you get used it, therefore the earlier you Chinsult, the earlier you begin to enjoy the freedom.’

The music video of the song, filmed at the pink-infused Amaze Spa 兔子迷宮·礁溪浴場 in Yilan 宜蘭, pointedly provides the lyrics in Simplified Chinese Characters, the state-dictated version of the written language common on the Mainland (outside the PRC they are also known as ‘crippled characters’ 殘體字), and is packed with satirical tropes:

- NMSL (nǐmāsǐle 你妈死了; ‘your mum is dead’, or ‘drop dead’);

- Cotton (a reference to forced labour in Xinjiang)

- A panda ensconced in garlic chives (韭菜 jiǔcài are an endlessly renewable resource, reference to the exploitation of low-wage, disenfranchised workers);

- Apples and pineapples (a reference to the closure of Apple Daily in Hong Kong and a Mainland ban on Taiwanese pineapples 鳳梨);

- Hami melons (from Xinjiang, harvested by forced labour) and re-education (camps for Uyghurs);

- Teddy bears and honey (an reference to ‘Winnie the Pooh’ Xi Jinping);

- The suffocating embrace of Taiwan by the Mainland; the Great Firewall;

- Granddad (formerly ‘Uncle Xi’);

- Carrying a burden long distances (a mocking reference to Xi Jinping’s bravura about his peasant prowess);

- Gourmet delights such as cats and dogs; and,

- Zoonotic nemeses like civets and bats (a reference to SARS and COVID-19).

The song is a tongue-in-cheek apologia addressed to PRC pinkies who vault over the Great Firewall in droves to attack and denounce whatever appears in the international media, on social media platforms or more generally online, or among non-complaint Chinese-writing people that they find ‘triggering’.

It is performed by two artists from ethnically Chinese communities in Malaysia and Australia, countries in which ethnic, cultural and intellectual diversity have long been the norm, even though such diversity is readily debated and ‘contested’. Over the years, Namewee has made work in a range of Sinophone/ 華語 languages and dialects that expresses an inclusiveness underpinned by a cultural confidence, and, like that of Kimberely Chen, it is a confidence that floats free from the constraints of the Mainland Chinese party-state and the conformist demands it makes on everyone it chooses to claim as ‘Descendants of the Yellow Emperor’ 炎黃子孫. The message of creators like Namewee and Chen is one that does not fit neatly into the claustrophobic ‘China Story’ of the Xi Jinping era. In the case of ‘Hearts of Glass’, however, it immediately enjoyed global popularity. The song offered an important lesson for Chinese and non-Chinese listeners alike, one that was all the more appealing because in an age of outrage it dealt with a serious subject with a refreshingly irreverent lightness of touch.

Defending himself against accusations that the burlesque mocked Mainlanders, Namewee said in series of tweets that (inadvertently) recalled the Party line during the Hundred Flowers Campaign of 1956-1957 that ‘You may believe what you wang, I claim plausible deniability’ 言者無意 聽者有心。That is to say: make what you will of the song; if it unsettles or outrages you, that’s on you.

Namewee’s ‘Hearts of Glass’, along with the new Weibo account he had registered to promote it, was immediately blocked on the Mainland. At the time of writing, the song had been viewed on YouTube over 5.2 million times (see below for an update) and Kimberley Chen had posted a response to the Mainland ban in which she sang:

‘So sorry to cause offense

Weibo’s deleted the account, so what? I hear something:

It’s your hearts of glass shattering on the ground

Not a problem: I still got Instagram and Facebook!

We’re too direct, too in your face

Sorry to tell you, but we’re trending No. 1 on YouTube’對不起傷害了您。微博刪掉沒關係,

我聽見有個聲音,是玻璃心碎一地。

沒關係我還有IG,也還有FB

或許不該太直白 超直白

I’m so sorry

Youtube trending 第一名

Chen ends her YouTube message by saying:

‘Don’t be afraid to be yourself.’

***

Update (22 October 2021)

- ‘Hearts of Glass’ notched up over twelve million views on YouTube in the week following its release; and,

- Namewee 黃明志 & Kimberley Chen 陳芳語, ‘Please Handle With Care! The Making Of【Fragile 玻璃心】’, YouTube, 22 October 2021

***

***

Hearts of Glass

玻璃心

(It Might Break Your Pinky Heart)

Music & lyrics: Namewee

黄明志

Featuring: Kimberley Chen Fang-yu

陈芳语

Translated by Geremie R. Barmé

Warning: If you are a fragile pink, proceed with caution

警告:玻璃心患者慎入

You never even listen to what I gotta say

Launching your assaults, wave after wave

I just don’t get it: how come you’re so insulted?

You’d think you’re at war with everyone

说的话 你从来都不想听

却又滔滔不绝出征反击

不明白 到底辱了你哪里

总觉得世界与你为敌

You claim (I belong to you)

Don’t try to escape (come home, quick)

You gotta win it all (so unreasonable)

Yet you want me (to explain)

Our ‘indivisible relationship’

And I’m supposed to protect your fragile pinky heart

你说我 (属于你)

别逃避 (快回家里)

一点都不能少都让你赢 (不讲道理)

你要我 (去说明)

不可分割的关系

还要呵护着你易碎玻璃

So sorry to cause offense

Hurt your feelings, your self-esteem

Is that sound your hearts of glass

Breaking into little bitty pieces?

对不起伤害了你

伤了你的感情

我听见有个声音

是玻璃心碎一地

Sorry I’m so willful

Guess the truth hurts

I’m too direct, too in your face

I’m So Sorry

I got you all in knots

对不起是我太任性

讲真话总让人伤心

或许不该太直白 超直白

I’m So Sorry

又让你森七七

You got that pure pinkie heart of yours

You so love: doggies, cats, civets and bats

So just behave, don’t jump the Firewall

If Grandaddy Pooh knew you’ll be in his Thoughts

你拥有 粉红色纯洁的心

热爱小狗小猫蝙蝠果子狸

要听话 别再攀岩爬墙壁

爷爷知道了又要怀念你

You say (you’re hard working)

You carry a burden on one shoulder (walking non stop)

Harvesting cotton, collecting that sweet honey (common prosperity)

Going all out (gotta get outta poverty)

Cutting you garlic chives every day

Throwing 1000 yuan your way (dumb fucks)

How happy happy you are!

你说你 (很努力)

不换肩 (走了十里)

扛着棉花 采著牠爱的蜂蜜 (共同富裕)

拼了命 (要脱贫)

每天到韭菜园里

收割撒币月领一千真开心

So sorry to cause offense

Hurt your feelings, your self-esteem

Is that sound your hearts of glass

Breaking into little bitty pieces?

对不起伤害了你

伤了你的感情

我听见有个声音

是玻璃心碎一地

Sorry I’m so willful

Guess the truth hurts

I’m too direct, too in your face

I’m So Sorry

I got you all in knots

对不起是我太任性

讲真话总让人伤心

或许不该太直白 超直白

I’m So Sorry

又让你森七七

If I talk, I gotta bring a muzzle

Scared I’ll end up planting Hami melons

Get myself re-educated

If I bite an apple you wanna slice of our pineapples

You over there cursing my mom

Puhleese stop stealing my shit

If you think I’ll kneel and beg forgiveness

You got it all wrong

Talking to you is as useless as lipstick on a panda

Shocked as hell, you just go piss your pants

And suck in a deep breath

说个话 还要自带消音

怕被送进去 种哈密瓜再教育

吃了苹果 你又要切凤梨

在那边气噗噗 就骂我的妈咪

拜托你 别再偷我的东西

要我跪下去 Sorry我不可以

跟你说话 像对熊猫弹琴

真的惊呆了吓尿了 倒吸一口气

So sorry to cause offense

Hurt your feelings, your self-esteem

Is that sound your hearts of glass

Breaking into little bitty pieces?

对不起伤害了你

伤了你的感情

我听见有个声音

是玻璃心碎一地

Sorry I’m so willful

Guess the truth hurts

I’m too direct, too in your face

I’m So Sorry

I got you all in knots

对不起是我太任性

讲真话总让人伤心

或许不该太直白 超直白

I’m So Sorry

又让你森七七

Sorry you’re

All bent outta shape

Sorry baby

It’s just that you got a heart of glass

对不起

伤害了你

Sorry baby

玻璃心

***