Jottings in New Sinology

China Heritage marks New Zealand Chinese Language Week 2022 (25 September-1 October 2022) by reprinting a poem and a series of tweets by Chris Tse, New Zealand’s poet laureate (2022-2024), as well as a report by Eda Tang for Stuff News.

***

Many independent-minded Chinese writers and critics refer to the Xi Jinping decade (2012-2022) as an era of ‘draconian Qin-style rule’ 秦制 Qín zhì. ‘Qin’ is a reference to the rule of Qin Shihuang, the first emperor of China’s inaugural dynasty that lasted from 221 to 206 BCE. Excoriated for over two millennia, the Qin finally found a champion in Mao Zedong. He praised Qin’s relentless efforts to unify, modify and standardise life within its borders. Xi Jinping has inherited Mao’s obsession with the Qin and its mania for homogenisation (see ‘The Spectre of Prince Han Fei in Xi Jinping’s China’, China Heritage, 6 May 2021).

During the Xi Jinping decade, long-debated issues related to ethnic differences within China’s borders, language, culture and identity have been resolved in a manner that favours what could be dubbed the Macdonaldisation of Chinese civilisation. Xi’s cookie-cutter approach is also applied to the global Chinese world.

In You Should Look Back, the introduction to our series Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium, we announced that:

This series and its predecessors offer an extended commentary on contemporary China; they are also a personal meditation cum memoir related to the wonder and perplexity elicited by a lifelong involvement with that country, its peoples and their cultures. In the process we reflect on how a grand and vastly populous nation-civilisation that enjoys both global reach and significance has, under Xi Jinping and his aging Red Guard generation, been reduced to a pusillanimous scale. Official China has been whittled down to the size of the ego of the Sole Leader, 一尊 yī zūn, and the circumscribed vision of the Chinese Communist Party. Vibrant Other Chinas, however, flourish regardless.

No matter how grandiloquent the claims or bombastic the pronouncements issuing out of Beijing, a dolorous reality is undeniable: as the country enjoys levels of wealth and achievement unique in the history of the People’s Republic, a cabal of Party leaders and their intellectual courtiers assert that it is their prerogative to determine and define what China is, what being Chinese means (and can mean), as well as what the legitimate aspirations, languages, histories, thoughts and the state of being of all Chinese peoples should be.

For those who live in a global Chinese world long nurtured by the riches of Taiwan and Hong Kong, a Mainland revived during the decades of economic reform and the creativity of a plethora of Chinese diasporic communities, it is a tragedy of immense proportions that a clutch of rigid, nay-saying bureaucrats thus holds sway and that it arrogates to itself the power to legislate and police the borders of what by all rights should be a cacophonous multiverse of Chinese possibility. By imposing an educational regime that, to quote Xi Jinping, ‘grabs them in the cradle’ 從娃娃抓起, by creating a censorious media monolith that spews forth a carefully curated ‘China Story’ and by pursuing a ‘chilly war’ internationally with the encouragement of battalions of online vigilantes, the Party continues to terraform China and create a monotonous landscape. All of this is aided and abetted by a sharp-edged new phase in a century-long contestation with the United States and the Western world.

Although Xi Jinping’s enterprise builds on the twisted legacy of the Mao era and the darkest aspirations of the Deng-Jiang-Hu reform decades, it is obvious that his Empire of Tedium is also the handiwork of willing multitudes who travail at the behest of one man and the party-state-army that he dominates.

***

I began my formal study of Chinese — the modern and literary languages, history, literature, culture and thought — at the age of seventeen. Prior to that high-school classmates, including Australian-born Chinese friends who spoke Cantonese, Hokkien or both, along with ethnically Chinese exchange students from Singapore and Malaysia had already given me a sense of Sinophone linguistic and cultural (not to mention culinary) diversity.

My initial university mentors were a Belgian, who delivered the main language lectures, and a Russian who had grown up in Beijing/Beiping. She was a peerless tutor who invigilated over pronunciation and our study of syntax. Advanced Chinese was taught by a Mainland-born Taiwanese literary scholar, a Hong Kong Cantonese speaker and a former Manchu noble from Old Peking. Our survey course in literature, which covered the Shang to the Qing, was the province of a classically trained American Chinese Catholic nun from a ancient Jiangnan lineage who also happened to be an expert in Neo-Confucian thought. Our Classical Chinese instruction was initially overseen by a scholar from a Han Bannerman 漢軍 family and then by an Australian Jew known for his translation of Mencius into Hebrew. In our final year our main lecturer, whose focus was Tang and Song prose and poetry, happened to be an internationally famous literary sojourner and artist who had grown up in Jiangxi province. (See In Memoriam.)

In their disparate ways these teachers introduced us to the overlapping nature and geopolitical diversity of 國語 guóyǔ, 華語 huáyǔ and 普通話 pǔtōnghuà. They also drilled us in the daunting thicket of romanisation systems, from Wade-Giles and Gwoyeu Romatzyh to Hanyu Pinyin. Through readings selected from newspapers, literary journals and esteemed works of literature, we encountered first the more stately Republican-era forms of Chinese, then Hong Kong pop culture and advertising ‘brogue’ and, finally, the kind of mainland Newspeak featured in the pages of Red Flag 紅旗 Hóng qí, the theoretical organ of the Communist Party that was renamed Fact Seeking 求是 Qiú shì in 1988.

By studying classical and literary Chinese we were enjoyed an overview of the numerous forms and genres of the written language from the pre-Qin to the late-Qing. Even as undergraduates we came to appreciate what I would later call the ‘Chinese multiverse’. After some years studying in Shanghai and Shenyang during the dying days of Maoism, I worked in Hong Kong and ended up having a fifteen-year part-time career as a writer of Chinese essays — 小品、雜文、隨感 — in that unique city.

Throughout my fifty-year ‘life in Chinese’ I have been sorely aware that the natural proclivity and unnatural policies of the China’s Communists are aimed at making sure that ‘everyone is allowed to be different, but in exactly the same way.’

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

27 September 2022

***

A New Sinology, or a more profound and humanly rich engagement with China and the Chinese world, is not a study of an exotic, or increasingly familiar Other. It is an approach that also constitutes a concerted attempt to include China as integral to the idea of a shared humanity in all of its contradictory, unsettling as well as inspiring complexity. It is a study, an engagement, an internalization that enriches the possibilities of our own condition. … Nor is this merely an engagement in one direction. For to talk of some divide, some chasm that has to be bridged or crossed, is to accept too easily the belief that difference predominantly creates barriers and distances. It also limits us unnecessarily to the idea that studying about China, learning its languages, cultures and thought systems is to limit ourselves to being interpreters of a ‘correct’ view of what China and Chineseness is. While such linguistic and cultural translation is essential for the growth of all peoples, our engagement with China is not merely that of sophisticated interpreters equipped through dint of hard work and long years of study with some privileged insider knowledge.

— from Geremie R. Barmé, ‘China’s Promise’

The China Beat, 20 January 2010

***

Further Reading:

- Chris Tse website

- Chris Tse: @chrisjtse

- Tze Ming Mok: @tzemingdynasty

- Eda Tang: @tangytot

- Pou Tiaki: @PouTiaki

- Chinese Languages in Aotearoa, Te Papa

- NZCLW: @chineselangweek

- Hearsay News: “My Wife’s Chinese, so Knee How”, Craccum, 10 October 2022

- Jack Yan, ‘New Zealand Chinese Language Week Reviewed — In Cantonese’, 2 October 2022

- Charlotte Graham-McLay, ‘Cool, candid and sometimes angry, New Zealand’s laureate wants to make poetry pop’, The Guardian, 30 September 2022

- Alexia Russell, ‘Why Chinese Language Week is causing angst’, The Detail, 30 September 2022

- Chris Tse, ‘A collection of thoughts on New Zealand Chinese Language Week’, The Spin-off, 30 September 2022

- Tze Ming Mok, ‘The Thursday Poem: Bad example’, The Spin-off, 29 September 2022

- Justin Wong, Where are the languages of the first Chinese New Zealanders in ‘Chinese Language Week’?, Dominion Post, 27 September 2022

- Eda Tang, ‘Please stop saying ‘ni hao’ if you want to be an ally to Chinese people’, Stuff News, 25 September 2022

- James A. Millward, ‘(Identity) Politics in Command: Xi Jinping’s July Visit to Xinjiang’, The China Story, 16 August 2022

- Introduction 瞽 — You Should Look Back, China Heritage, 1 February 2022

- Jianying Zha 查建英 & Geremie R. Barmé, ‘The Spectre of Prince Han Fei in Xi Jinping’s China’, China Heritage, 6 May 2021

- Hong Kong Apostasy, China Heritage (1 July 2019-)

- Xu Jilin 许纪霖, ‘Shanghai Culture Lost 上海:城市风情依旧,文化何处寻觅?’, China Heritage Quarterly, No.22 (June 2010)

- Edward McDonald, ‘The ‘中国通’ or the ‘Sinophone’? — Towards a political economy of Chinese language teaching’, China Heritage Quarterly, No.25 (March 2011)

- Michael (名可名非常名) Churchman, ‘Confucius Institutes and Controlling Chinese Languages’, China Heritage Quarterly, No.26 (June 2011)

Unlike other language weeks celebrated in Aotearoa, NZCLW does little to involve and empower the community it should be representing. Imagine if a group of Pākehā organised something called Pasifika Language Week for a primarily non-Pasifika audience but only focused on Sāmoan and sidelined all other languages because not enough people speak them or because they have no business or economic value. That’s what NZCLW feels like to some Chinese New Zealanders, many of whom are descendents of the first Chinese to arrive in Aotearoa, who were Cantonese speakers.

— Chris Tse, ‘A collection of thoughts on New Zealand Chinese Language Week’, The Spin-off, 30 September 2022

***

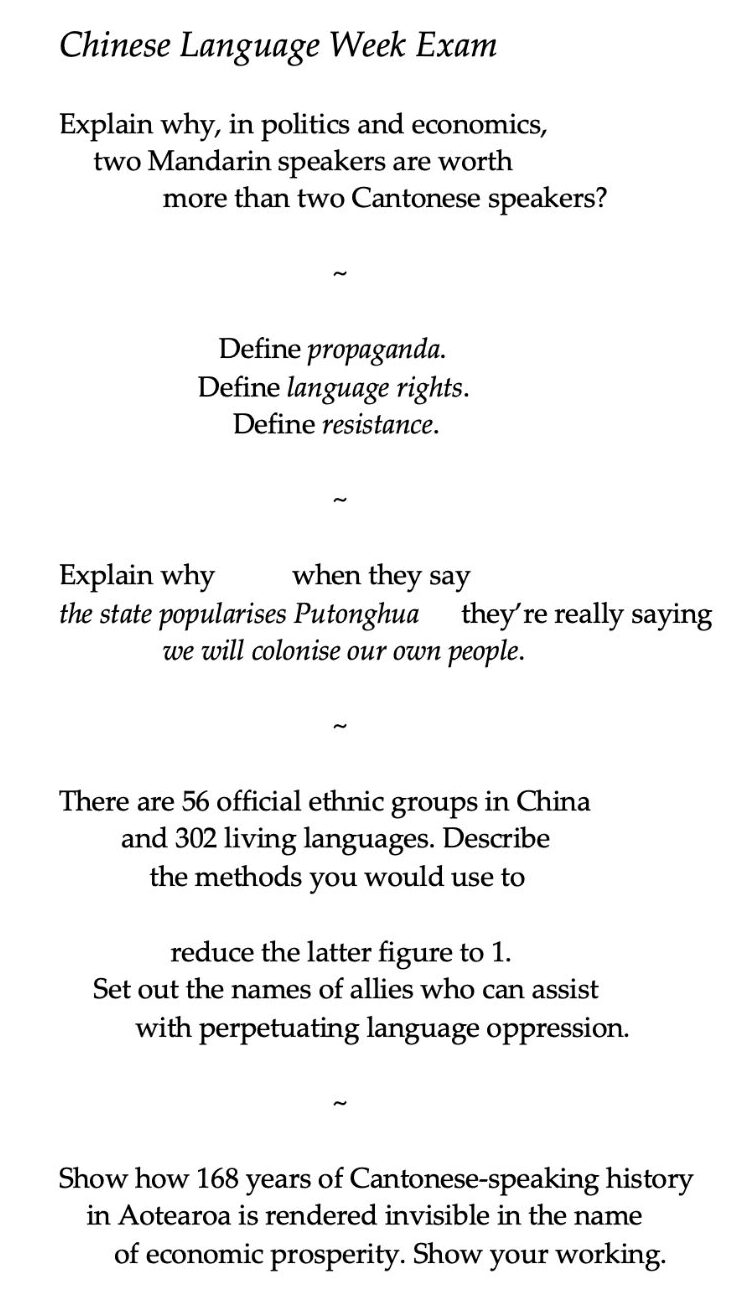

A poem for New Zealand Chinese Language Week by Chris Tse

***

Setting an Exam

Chris Tse on NZCLW

via @chrisjtse

A month or so ago I was approached to write a poem for New Zealand Chinese Language Week. I declined and set out my reasons. There were more messages exchanged about the benefits of promoting/learning Mandarin; nothing about meaningful change to include other Chinese languages.

I told them I’d been through their Facebook posts for the past year and Cantonese was only mentioned twice — in other organisations’ posts that were shared by the NZCLW page. For years people have left comments asking them to be more inclusive.

The organisers have been told and given feedback time and time again to no avail. I was told there aren’t enough resources to promote other ‘dialects’ but that going forward there would be opportunities to promote ‘other dialects during the week’ (very non-commital/non-specific).

Yesterday’s articles, and the Twitter discourse earlier in the week, are a good summary of the many feelings and frustrations surrounding #NZCLW for non-Mandarin speakers. It’s really sad to feel like you’re shit at being Chinese because you don’t speak the ‘right’ language.

Anyway, the poem in the first tweet is one of two I started writing for myself over the past few weeks. The second poem is sadder but it might not be ready this week so let’s just fucking rage until they finally listen to us. 加油.

— from a thread on Twitter, 26 September 2022

***

‘This is gonna be cringe’:

Chinese Language Week falls flat for Chinese Kiwis

Eda Tang

“Next week is going to be a tough week for our Chinese communities,” tweeted Sidney Wong (黃吉贊), a Cantonese speaker and doctoral student in linguistics.

New Zealand Chinese Language Week (NZCLW) kicks off on Sunday, and Wong is one of many Chinese New Zealanders actively distancing themselves from the event.

It would, he added, see many Chinese communities “continue to be erased and made invisible in the name of economic prosperity”.

Tze Ming Mok, a social scientist and Asian community advocate, thinks the name is misleading.

“Really what it is, it’s the week of Mandarin language education in service of capitalism and New Zealand’s foreign affairs agenda. [It’s] not really a week for Chinese people.”

Mok is disappointed to see that of the seven board members of the New Zealand Chinese Language Trust, Labour MP Naisi Chen is the only Chinese person.

“It’s not like we’re lacking in Asian people who speak Chinese,” says Mok.

“We already know that it’s not for us as it’s literally just a webpage full of white people.

“My expectations of Chinese Language Week were always like, ‘well, this is gonna be cringe’ and they have met my expectations.”

The NZCLW campaign has largely been fronted by non-Chinese ‘Mandarin Superstars’ who share their experiences of learning Mandarin and the opportunities it has afforded them.

According to its website, NZCLW “is designed to increase Chinese language learning in New Zealand [and] seeks to bridge the cultural and linguistic knowledge gap between China and New Zealand by delivering fun and practical initiatives that assist Kiwis to learn Chinese”.

Jo Coughlan, chair of the New Zealand Chinese Language Week Trust, says “there are many languages within China, but New Zealand Chinese Language Week focuses on Mandarin.

“This is the language taught in New Zealand schools and universities, and our purpose is to encourage New Zealanders to learn Chinese, so we concentrate on the language taught in our education institutions.”

According to the 2018 census, there are at least 18 Chinese languages spoken in Aotearoa.

Efforts to include other Chinese languages have been pushed by Richard Leung, who is the immediate past president of the New Zealand Chinese Association and a leader in Auckland’s Chinese community.

Leung says while it’s good the Ministry for Ethnic Communities granted $20,000 towards NZCLW from its development fund, it’s disappointing the event hasn’t become more diverse as a result.

“Supporting an organisation that has chosen to erase the needs and histories of communities in Aotearoa New Zealand doesn’t seem diverse or inclusive, and it does nothing to support the Government’s initiatives to strengthen social cohesion.”

Leung discussed his concerns with board members of the NZCLW Trust, and got an essay by Nigel Murphy about Chinese language history in New Zealand uploaded to the trust’s website.

He also lobbied for the Prime Minister and the Minister for Ethnic Communities to include Cantonese, Hokkien and Teochew greetings in their video greetings for NZCLW, and pushed for a more accurate description of NZCLW on the Ministry of Education’s website.

But he says this is just “a small start”.

“NZCLW has nothing about being proud of our culture and heritage, unlike all the other language weeks. It is not about preservation of our whakapapa, [but] the refusal to preserve endangered languages and cultures.”

Leung says it would be more accurately described as Mandarin Language Week, and is concerned that “in one or two generations, Cantonese will be very much an outside-of-China language, even in Hong Kong”.

Cantonese-speaking students in Hong Kong have told i-Cable that they were punished at school for speaking Cantonese. In 2010, the Chinese government attempted to cut Cantonese broadcast programming in Guangzhou, sparking protest and fierce criticism.

Latest census data shows that 36% of Chinese New Zealanders speak Mandarin, 20% speak Cantonese, 20% speak other Chinese languages, and the remainder – almost a quarter – do not speak any form of Chinese. Up until 2018, Cantonese was the most spoken Chinese language in the country, before it was overtaken by Mandarin.

“Ignoring the existence of other Chinese languages is deeply disrespectful to the legacy and struggles of early Chinese migrants to Aotearoa New Zealand and their descendants,” Leung says.

The importance of heritage

Grace Gassin, Te Papa curator of Asian New Zealand Histories, leads a project called Chinese Languages in Aotearoa that highlights complex issues of cultural identity within various Chinese New Zealand communities, sharing their stories in Mandarin, Hokkien, Cantonese and Hakka.

Gassin says the issue with Chinese Language Week is that often it’s “more about trade or economics or about Chinese New Zealand ties, rather than the kind of kōrero that local Chinese communities want to have and are struggling to have heard.”

Gassin, who is a Hokkien speaker, says all Chinese heritages matter, “regardless of whether your language is deemed economically useful”.

If we want to be more linguistically inclusive, she adds, then we need to support Chinese Kiwis to “stay connected to a mother tongue that in some ways has been lost through an assimilation process and these other kinds of historic processes”.

Coughlan acknowledges that the NZCLW Trust is not a New Zealand-Chinese organisation nor a Chinese organisation.

“The trust was set up initially by academics, diplomats, and business people to encourage non-Chinese New Zealanders to learn Chinese,” she says.

“New Zealand has a diverse and vibrant society, and we hope our work contributes to that.”

***

Source:

- Eda Tang, ‘This is gonna be cringe’: Chinese Language Week falls flat for Chinese Kiwis, Stuff News, 25 September 2022

***