Hong Kong Apostasy

最可憐一片江山

According to the Chinese calendar, the 22nd June 2023 marks ‘the double fifth’ 端陽 duānyáng, that is, the Fifth Day of the Fifth Lunar Month. Known also as Dragon Boat Festival, commemorates the ancient poet Qu Yuan 屈原 (c. third century BCE), who is said to have drowned himself on this day.

The Fifth Month of the lunar calendar is seen as being a precarious time: the height of summer approaches and pests and pestilence threaten the wellbeing both of people and of crops.

As we noted in Memory Holes, old & new, while there may be the promise of future bounty, an immediate danger is posed by the Five Poisonous Creatures 五毒: snakes 蛇, scorpions 蝎, centipedes 蜈蚣, toads 蟾蜍 and spiders 蜘蛛. It is a time, therefore, to Eliminate the Five Noxious Things 驅五毒. It is also the season to make good on debts and for mourning loss, in particular since, for over a thousand years, it has been associated with the death of the poet Qu Yuan (屈原, third century BCE) by drowning. For this reason it is also known as ‘Poet’s Festival’ 詩人節. In recent years, the ancient story of the poet-courtier exiled by his beloved ruler due to the calumnies of others, something he writes about at length in his poems, has been interpreted by members of the LGBT community as evidence that this day is also the first Gay Valentine’s in history.

In 2008, the re-calibration of public holidays in China saw for the first time in the near sixty years of the People’s Republic traditional holidays afforded prominence. The Double Five Festival (variously 端午節; 端陽節; 雙五節; 龍舟節) was now to be celebrated with a three-day holiday.

***

Qu Yuan, and the poems ascribed to him, were a lifelong theme in the work of Huang Yongyu, the artist whose death at the age of ninety-nine we mourned in Yongyu, ave atque vale.

After having met Huang Yongyu at the ‘Yang’s Speakeasy’ at Baiwan Zhuang in 1981, I visited him in his large newly allocated apartment in the ‘minister’s compound’ at Sanlihe, just north of the the Academy of Science. There he introduced me to his macaque, recently famous as the model Yongyu used to create his Year of the Monkey commemorative stamp in 1980.

I also got an introduction to Zhong Shuhe 鐘叔河, an active publisher with Yuelu Publishers in Changsha, Hunan. Shuhe then introduced me to Zhu Zheng 朱正, a marvelously insightful scholar of Lu Xun and a man who took it upon himself to write the definitive account of the Anti-Rightist Campaign of 1957, one that continues to haunt China today. Born in 1931 and now both in their nineties, Zhong and Zhu are still with us.

Back in early 1981, Yongyu also happened to be at the centre of the first major cultural controversy since Mao’s death. Elements of his biography had had been incorporated into a film script entitled Unrequited Love 苦戀 that was eventually made into a film titled The Sun and Man 太陽和人. The protagonist of the film, an artist, had returned from overseas to contribute his talents to the socialist fatherland only to find himself subjected to years of persecution. He participates in the Tiananmen protests of April 1976 and while others chant slogans and recite poems protesting against the Maoists he puts up a painting on the theme of ‘Qu Yuan Questions Heaven’ 屈原問天, a reference to ‘Heavenly Questions’ 天問, a work attributed to Qu Yuan, China’s ‘ur-poet’. The inference is that, like the ancient poet, the modern-day artist has been spurned by the rulers. In the film, his daughter famously asks:

‘You love this country, but it is a bitter, unrequited love. Does this country really love you back?’

您愛這個國家,苦苦地戀著這個國家,可這個國家愛您嗎?

The loyal poet Qu Yuan, rejected by the court, is said to have drowned himself. In the 1981 film, the artist is forced to flee another round of political persecution. For at time he manages to survive in the wilds, eventually succumbing to illness but not before he has traced out a large question mark in the snow. The final scene shows a flock of birds in the form of the Chinese character 人 rén, ‘person’ or ‘humanity’.

In April 1981, both the scenario and the film of Unrequited Love led to a controversy, first within the PLA and then at the pinnacle of Communist Party power. Outraged by a film that was an affront to the Four Basic Principles that he had only recently declared underpinned the China state, Deng Xiaoping declared that this insidious had to be denounced, albeit within reason. The controversy surrounding Unrequited Love soon died down — memories of the vicious cultural purges of the previous three decades were still raw; anyway, Deng and his comrades did not want ideological wrangling to get in the way of their ambitious economic and political agenda. Nonetheless, the attacks on the film — which was never released — and on Bai Hua (白樺, 1930-2019), the author of the scenario, which had been published, adumbrated future purges of ‘bourgeois liberalisation’, a code for anything that questioned Communist Party rule or that championed independence of mind.

***

As we noted earlier, the 22nd of June 2023 is the Fifth Day of the Fifth Month in the Lunar Calendar. Known as the Dragon Boat Festival, this day commemorates the memory of the ancient poet Qu Yuan (see The Double Fifth Festival and the 35th of May 2022, 3 June 2022). Beijing marked the day by publicising party-state-army supremo Xi Jinping’s peerless insights into Qu Yuan’s legacy. Here we commemorate Huang Yongyu, an artist who often depicted Qu Yuan and the poems that are attributed to him in The Songs of the South 楚辭 Chǔ cí. We do so in the company of Lee Yee 李怡, Huang’s good friend and our mentor, and Jimmy Lai 黎智英, with whom Yongyu was close during his decade of self-imposed exile after June Fourth 1989. We conclude our commemoration of the Double Fifth with a painting that Huang Yongyu made for the writer Dai Qing 戴晴 in 1992. As we have long argued, the Counter Reform of 1989-1992 presaged Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium. (See Prelude to a Restoration: Xi Jinping, Deng Xiaoping, Chen Yun & the Spectre of Mao Zedong, China Heritage, 20 September 2021.)

In the ‘red-washing’ of Huang’s life and work engineered and policed by China’s censors, works such as these are edited out of the record. China’s mainstream media celebrates Yongyu as an ‘irrepressible genius’ 鬼才 guǐ cái who reveled in the naïveté of a ‘wilful man-child’ 頑童 wán tóng. Even relatively independent sources in- and outside China make scant mention of Huang’s lifelong pursuit of wry social and political commentary. Some critics resent Huang both for his prosperous longevity and his unconventional success. In a rhetorical environment given to confrontation, they also find his aphoristic humour to be too circumspect and his insights into the foibles of humanity nugatory.

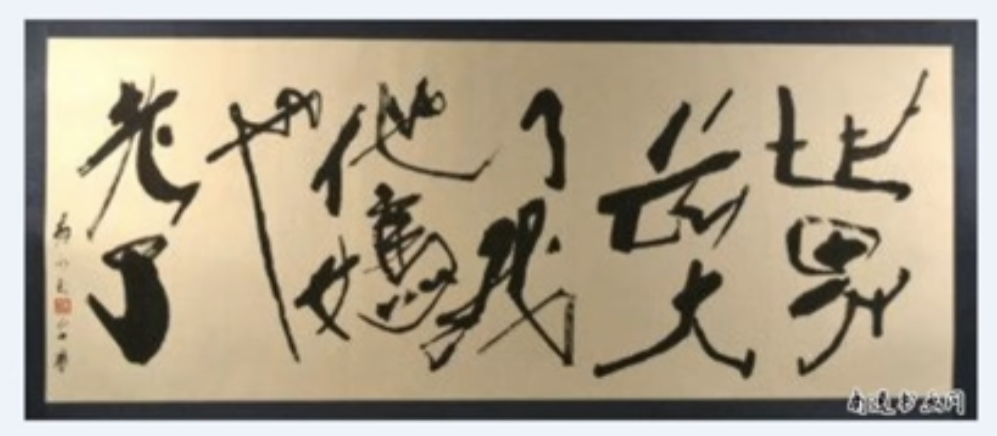

Such cloth-eared churlishness brings to mind the lines that Yongyu inscribed on the painting that he gave me in 1983:

While you and your fame will fade

The rivers forever onward flow.

爾曹身與名俱滅,

不廢江河萬古流。

[Note: See Yongyu, ave atque vale, 15 June 2023.]

***

‘Huang Yongyu, Lee Yee & Jimmy Lai’ is an addition to our series Hong Kong Apostasy, as well as being chapter in The Other China.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

22 June 2023

Fifth Day of the Fifth Month of the

Guimao Year of the Rabbit 2023

Dragon Boat Festival

癸卯兔年五月初五端午節

***

***

Related Material:

- The Double Fifth Festival and the 35th of May 2022, 3 June 2022

- 李怡,與黃永玉的交往,2022年4月22日

- 城寨,黃永玉逝世 壹傳媒大樓黎智英收藏多幅黃永玉名作去左邊?,油管,2023年6月14日

- 李怡,令我著迷的聯語 ,2022年7月24日

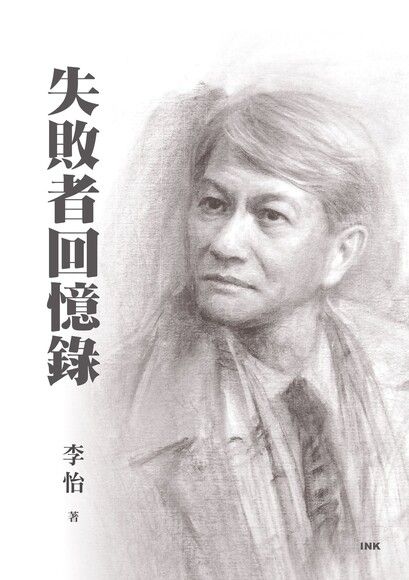

- 李怡,失敗者回憶錄,2021年7月12日至 2022年9月27日

- Lee Yee, ‘I Hereby Cancel Myself’, 24 April 2021

- Lee Yee, The Demise of Jimmy Lai’s Apple Daily, 23 June 2021

- Apple Daily, “The Four Noes” & the End of Chinese Media Independence, 24 June 2021

- Prelude to a Restoration: Xi Jinping, Deng Xiaoping, Chen Yun & the Spectre of Mao Zedong, 20 September 2021

- Lee Yee, three essays, 治 Hong Kong — twenty-five years after the fall (Appendix XII in Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium), 1 July 2022

- ‘You can’t rebel, you can’t start a revolution, and you can’t be independent.’ — How Ni Kuang saw the future of Hong Kong, 4 July 2022

- ‘For’ برای — in Memory of Lee Yee, 5 October 2022

- The Passion of Jimmy Lai, 21 April 2023

- Wang Xiaobo, ‘An Unconventional, Independent Pig’, trans. Sebastian Veg, in Outside the Pigsty Looking In, Two Views, China Heritage, 19 February 2019

- Jeffrey N. Wasserstrom, Vigil: Hong Kong on the Brink, New York: Columbia University Press, 2020

- Louisa Lim, Indelible City: Dispossession and Defiance in Hong Kong, Penguin Random House, 2022

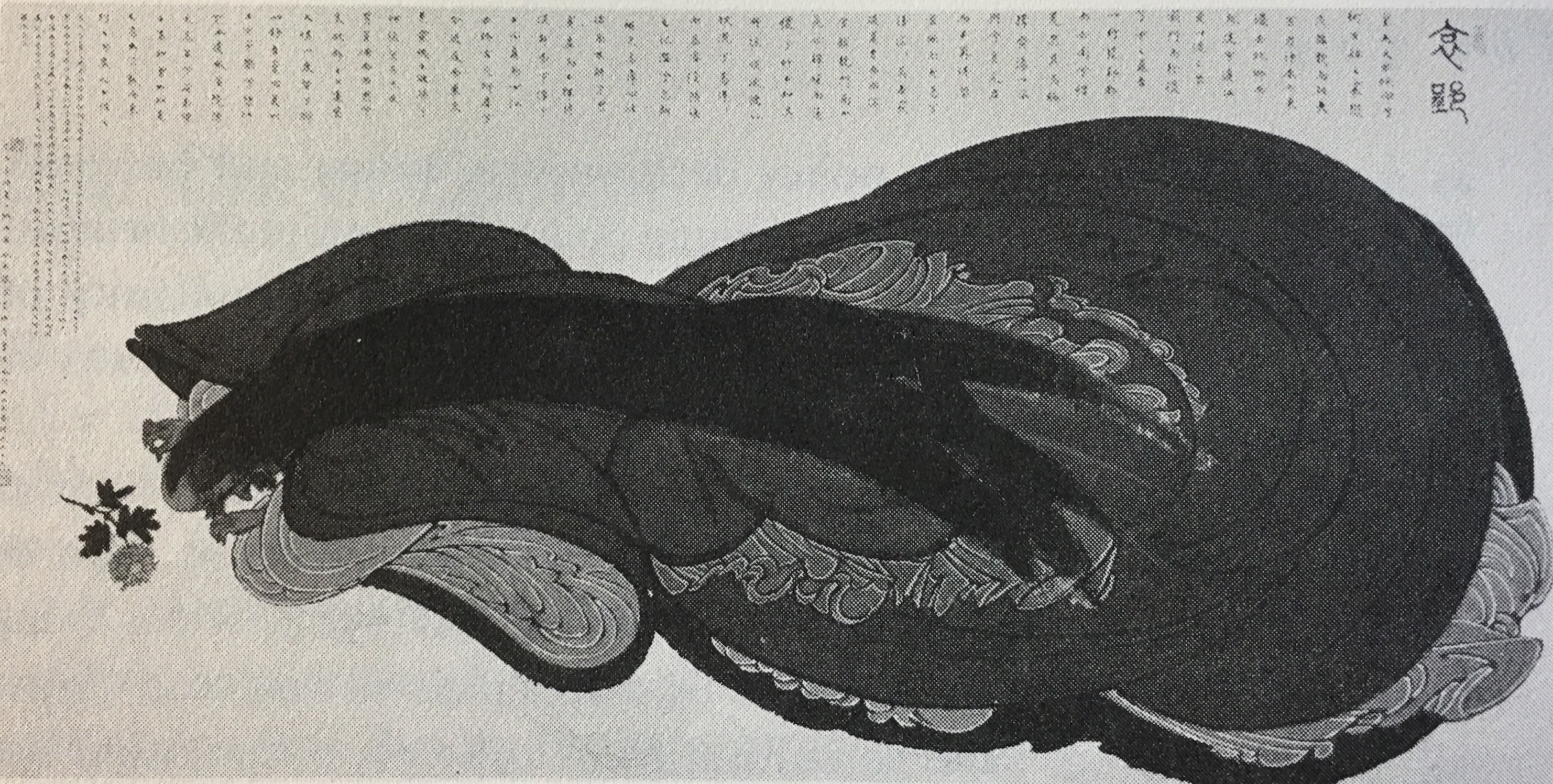

A Lament for Ying

哀郢

After the Fourth of June 1989, the celebrated artist Huang Yongyu 黃永玉, no stranger to political repression or controversy himself, painted Qu Yuan 屈原, China’s archpoet, prostrate in bereavement. Huang inscribed the text of ‘A Lament for Ying’ 哀郢, from ‘Nine Pieces’ 九章 in The Songs of the South 楚辭, on the painting. It was published in the Lee Yee’s journal The Nineties Monthly 九十年代月刊 in 1989 and included in New Ghosts, Old Dreams: Chinese Rebel Voices (1992).

***

***

High Heaven is not constant in its dispensations:

See how the country is moved to unrest and error!

The people are scattered and men cut off from their fellows.

In the middle of spring the move to the east began.

I left my old home and set off for distant places,

And following the waters of the Jiang and Xia, I travelled into exile.

…

My mind was drawn with yearning and my heart was grieved.

So far! I knew not whither my way was leading,

But followed the wind and waves, drifting on aimlessly,

A traveller on an endless journey, with no hope of return.

…

When your favour was courted with outward show of charm,

You were too weak; you had no will of your own.

But when, with deep loyalty, I tried to go in before you,

Jealousy cut me off and blocked my way to you.

…

You hate the deep and studious search for beauty,

But love a base knave’s braggart blusterings;

And so the crowd press forward and each day advance in your favours;

And true beauty is forced far off, and retires to distant places.

皇天之不純命兮,何百姓之震愆。

民離散而相失兮,方仲春而東遷。

去故鄉而就遠兮,遵江夏以流亡。

…

心嬋媛而傷懷兮,眇不知其所蹠。

順風波以從流兮,焉洋洋而爲客。

…

外承歡之汋約兮,諶荏弱而難持。

忠湛湛而願進兮,妒被離而障之。

…

憎慍惀之修美兮,好夫人之慷慨。

衆踥蹀而日進兮,美超遠而逾邁。

— from The Gate of Darkness, China Heritage, 4 June 2017, a revised and updated version of which was published under the title Tiananmen 1989 — Three Decades Behind China’s Gate of Darkness, 31 May 2019. This translation of ‘A Lament from Ying’ is taken from David Hawkes, The Songs of the South, pp.164-165

***

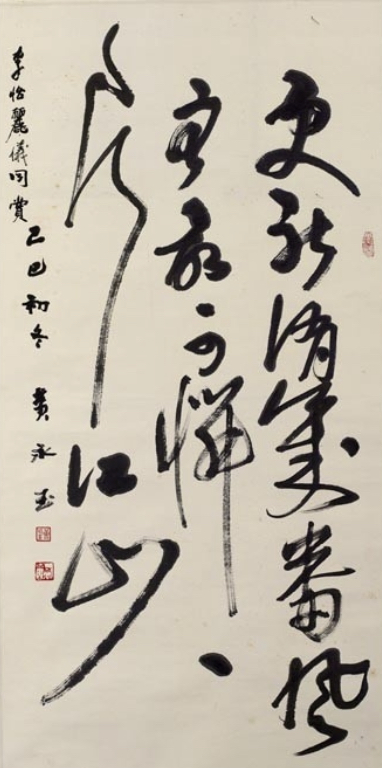

A Poetic Couplet for a Harrowing Year

In 1923, Liang Qichao created a new couplet by combing two lines of classical poetry:

更能消幾番風雨

最可惜一片江山

Battered though by repeated tempests,

These rivers and mountains enmesh our hearts.

In late 1989, Huang Yongyu presented a hand-written copy of this couplet to Lee Yee and his wife, Liang Liyi. (In this version, the character 惜 xī is changed to 憐 lián.) See: 黃永玉20多年前送我的字幅 ,2019年11月23日; 失敗者回憶錄171:令我著迷的聯語, 2022年7月24日; and, 失敗者回憶錄172:不解解不解,不解不解,2022年7月24日.)

Lee Yee used this couplet as the dedication to Exile 放逐:愛國愛港的懸念, a collection of essays that he published in 2008.

***

My History with Huang Yongyu

與黃永玉的交往

Lee Yee 李怡

translated by Geremie R. Barmé

‘When I‘m Chairman Mao, all the shit in this village will be mine!’

Back in the day, this was the ultimate dream of a peasant. The celebrated artist Huang Yongyu first encounter this particular China Dream when, like countless others, he was packed off to work the countryside in an effort to revolutionse his thinking [in the early 1960s]. For the farmer who told Huang about his ambition, Mao Zedong was the equivalent of an all-powerful emperor. Since human excrement was the best fertiliser, the peasant thought that real power would mean control over the poo in his village.

Recently, a friend of mine said that this old anecdote came to mind as she witnessed what was happening in Hong Kong. She’s also a writer and so, naturally, she got the point of Huang Yongyu’s story: even if a peasant became emperor of China their DNA meant they would still see the world through the eyes of a peasant. Hong Kong today, [in 2022], is in the grip of China’s peasant-in-chief.

***

Huang Yongyu was born into a Tujia family in Fenghuang county, Hunan province, in 1924. Today, he is one of China’s most renowned artists and by 2019 it was said that that the market value of his paintings was something in the vicinity of one million RMB [approx. USD 140,000] per square foot.

Huang is back living in Beijing. Since he is twelve years older than me that means he’s just about to become a centenarian. I think of him often and wonder how his health is holding up these days.

[Note: see Yongyu, ave atque vale in this journal.]

「如果我做了毛主席,這條村子的大糞就全是我的了!」這是知名畫家黃永玉引述他在中國下放農村時聽到一個農民說他的人生夢想:做毛主席就是做皇帝,種田最重要就是有大糞作肥料,所以擁有整條村子的大糞就是他的人生目標。

有朋友說,香港的近況讓她想到我告訴過她的這句話。朋友是搞創作的,能夠理解這句話的深層意義,不就是意味著有小農基因的人當上皇帝後的「理想」嗎?香港已經正式掌握在這樣的農人手上了。

黃永玉1924年出生於湖南鳳凰縣,土家族人,是當代中國最富盛名的藝術家之一。他作品的價格近年來一直在上漲,2019年已經超過100萬人民幣一平方尺了。他現住北京,比我大12歲,接近百歲了,不知道他身體情況怎樣?時刻惦念著。

Huang and I had a lot to do with each other in the years after June Fourth 1989. In the immediate aftermath of that event, Yongyu created works that gave expression to bitter outrage; later, in a more meditative mood, he made a painting that depicted [the ancient poet] Qu Yuan in prostrate anguish. The top third of the painting was taken up by the text of ‘A Lament for Ying’ [for this painting, see above].

At the time I interviewed him [for The Nineties Monthly] which featured a short account of his life: He had relocated to Hong Kong in 1946 and took up a lectureship at the Central Art Academy in Beijing in 1953, returning to live in Hong Kong in 1988. Although he went back to China frequently, after June Fourth Huang confessed that he faced a quandary: ‘I don’t want to live overseas,’ he told me, ‘nor do I have any wish to return to the Motherland. So, where does that leave me?’

[Note: See also黃永玉一家是通過怎樣有趣的經歷才成為真正的「大雅寶人」?, 油管, 2022年9月2 日 and the essay大雅寶衚衕甲二號安魂祭, first published in two parts by The Nineties in January and February 1990.]

Back then, Yongyu often invited me over to his place for a meal and conversation and was more than happy when I brought friends with me. In fact, I seem to remember that I introduced him to Jimmy Lai 黎智英 and they got on so well that they were in frequent contact. Subsequently, Huang Heiman 黃黑蠻, Yongyu’s son, ended up related to Jimmy through marriage. Jimmy also became something of a collector of Yongyu’s work and he hung Huang’s paintings at home and throughout the headquarters of Next Media [in Tsuen Wan, the publishing company he founded in 1990].

Yongyu was also a superb calligrapher and essayist. In fact, I often thought that this literary style outshone his painting. He was always smoking a pipe, loved his dogs, enjoyed reading, listening to music… Above all, he used art to express a wicked sense of humour. He delighted in telling wry aphoristic stories and was a brilliantly engaging conversationalist. Take, for example, the way he expressed his view of what would happen following Beijing’s takeover of Hong Kong in 1997. Yongyu observed that,

‘The people who spit wherever they please [then a notorious characteristic of Mainland Chinese] will end up arresting the people who don’t spit all over the place.’

Every conversation with him was a pure delight.

跟黃永玉往來較多是在1989年六四後。他先是發表了含悲帶憤的畫作,其後感情就轉深沉,畫了屈原伏地哀痛、全文抄下屈大夫《哀郢》全詩的大畫。我在89年底給他做了一個訪問,略講了他的生平:1946年來香港、1953年去北京擔任中央美術學院講師、1988年又重回香港定居。來港後仍然常回中國。六四後他說他不知道怎麼辦了:「外國我不願意去,祖國我不想回,吾將焉赴?」

這之後,他常邀我去他家吃飯聊天。我帶一兩個朋友去見見這位大師,他也很樂意。黎智英似乎也是我介紹他們認識的。他們來往更多。後來黎智英和黃永玉的兒子黃黑蠻還成為連襟。黎智英收藏很多他的畫作,在壹傳媒大樓,或他家中,都有黃老的傑作。

黃永玉除有畫名之外,他的書法、文章也非常精彩。我甚至覺得他的文采更勝於他的畫作。他嗜煙斗,養狗,看書,聽音樂,繪事中常有自娛而不供發表的諷世之作。他健談風趣,博學多聞,談話時多用比喻。比如談到九七後的香港,他說屆時也許是「隨地吐痰的人抓捕不隨地吐痰的人」。跟他聊天是一件賞心樂事。

***

***

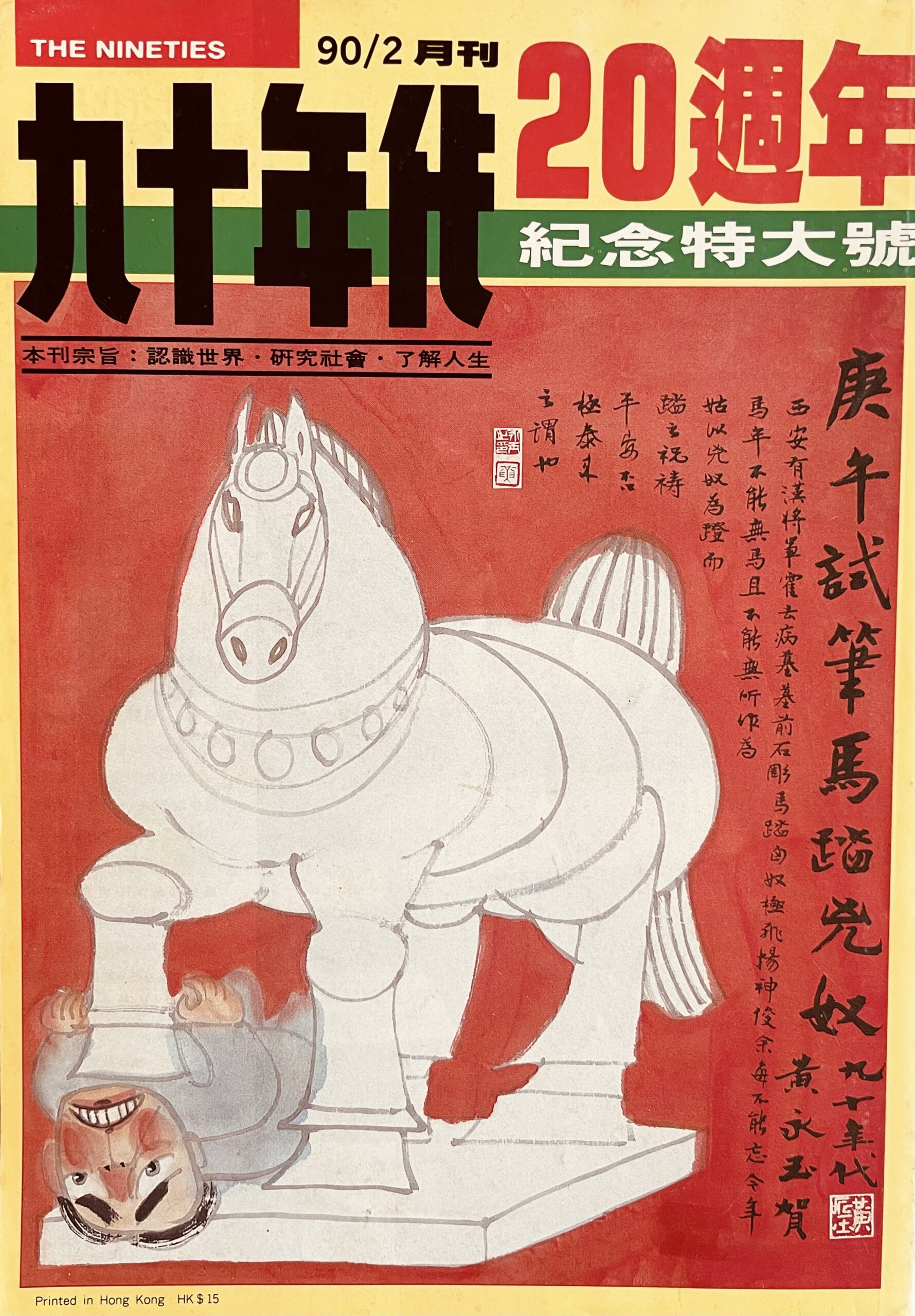

On one occasion after the events of 1989, Huang sketched a portrait of me in the space of about twenty-five minutes. That framed picture enjoyed pride of place in our living room. In the lead up to the 1990 Year of the Horse, he presented The Nineties Monthly with a painting titled ‘May the Horse Trample the Barbarian Underfoot’. The inscription on it read:

‘In Xi’an the tomb of the Han dynasty general Huo Qubing is decorated with a horse trampling a Xiongnu barbarian. The spirit of that sculpture has long stayed with me. As the Year of the Horse approaches we cannot be without horses of our own, nor can our horses be deficient in any way. I present to you a horse that may will trample today’s barbarians, both as a symbol of good fortune and in the hope that our shared sorrow will make way for better times.’

***

[Note: In the editorial introduction to the February 1990 issue of The Nineties, Lee Yee wrote:

‘We are grateful to Mr Huang Yongyu for painting a cover illustration for this issue. We believe that “The Horse Tramples the Barbarian Underfoot” reflects the wishes for the new year of a majority of Chinese, wherever they may be.’

感謝黃永玉先生為本期所畫的封面畫。「馬踏兇奴」,相信反映了海內外絕大多數的華人對馬年的期望。]

***

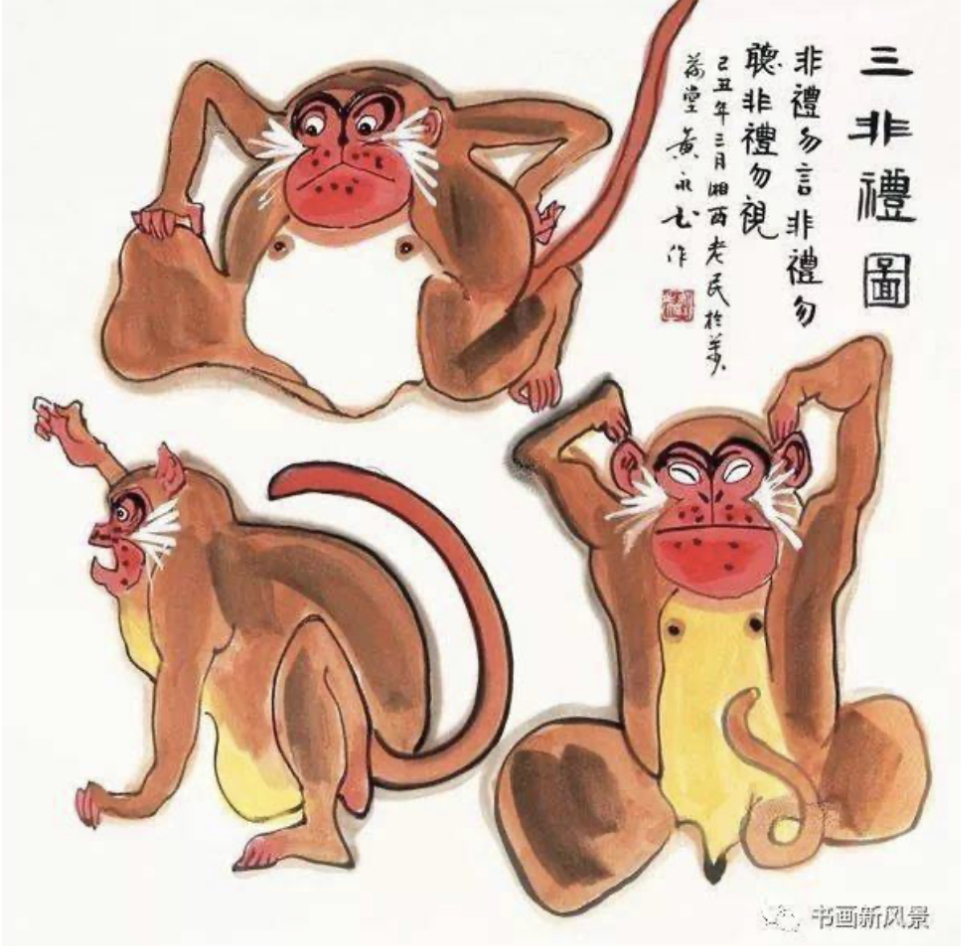

After that, Yongyu made a cover illustration for The Nineties for every Lunar New Year. I was particularly delighted by ‘The Three Dont’s’, the painting he made for the Year of the Monkey in 1992. His inscription read:

‘ “Speak According to Propriety , See All That Which Accords with Propriety, Listen only to what Propriety Permits” — for over two millennia they’ve promoted “propriety” 禮 lǐ and cautioned people to keep above the fray. But their version of “propriety” always changes. The wolves had their version of propriety, just as the tigers had theirs. Anyway, their “Three Dont’s” are solely directed at the common people. They have nothing to do with the those who invented “propriety”. I’ve always thought it was unfair that in the Orient the monkey is made to advocate speaking, seeing and hearing no evil. This Year of the Monkey I’ve made a painting that shows monkeys who dare to see, to listen and to abuse the power holders. It’s high time monkeys had a better rap.’

***

***

Yongyu kept painting zodiac images for the cover of our magazine right up until The Nineties ceased publication in 1998.

After Master Huang decided to take up an invitation to relocate to Beijing we saw far less of each other.

89年,他用了25分鐘畫了我的一幅速寫像。我裱起來裝鏡框,一直放在家裡的客廳中。1990舊曆年前,他為馬年畫了一幅「馬踏兇奴」給《九十年代》賀年,並寫上「西安有漢將軍霍去病墓基前石雕馬踏匈奴,極飛揚神俊,余每不能忘。今年馬年,不能無馬且不能無所作為,姑以兇奴為蹬而踏之,祝禱平安亦否極泰來之謂也。」

其後每年過年,他都給我們雜誌的封面畫一幅當年的生肖圖。最有趣的是1992年猴年他畫的三非禮圖,並寫道:「非禮勿言,非禮勿視,非禮勿聽。要知道,這兩千多年來,這個禮字變化多端,狼有狼的禮,虎有虎的禮,反正『勿』的對象只是庶人,和禮的發明者和追隨者,是沒有關係的。東方讓猴子來擔當執行禮的象徵,十分不公。適逢猴年,畫其敢看,敢聽,敢罵聲勢,以平其反。」

一直畫到1998年虎年,《九十年代》停刊。後來,黃老終於受邀再到北京定居。我們來往就少了。

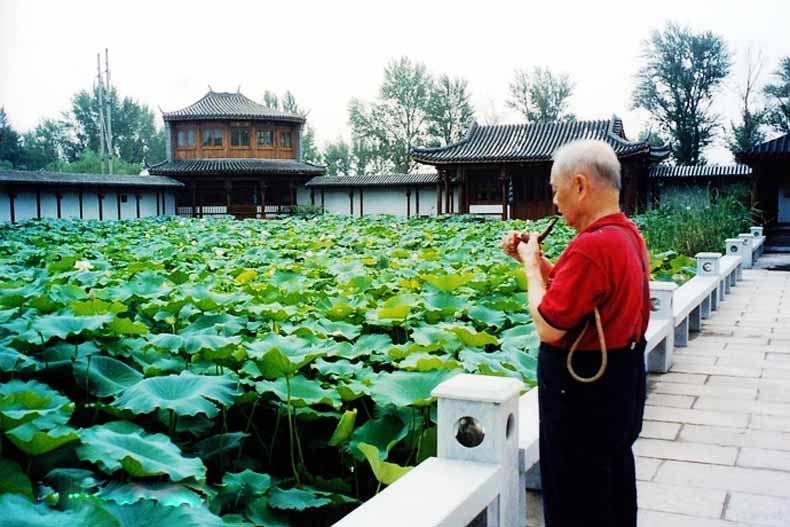

In April 2009, Yongyu called me while I was visiting family in Canada [shortly after my wife Liang Liyi’s death from cancer in late 2008]. He was in Hong Kong for a few days. Although we couldn’t meet up that time, I promised that I’d get up to Beijing that August to celebrate his birthday. On that trip I was joined by the writer Cheung Wan and some other friends. It was wonderful to see him again and the conversation flowed. He told stories about his years of labour reform during the Cultural Revolution; about how he’d had to dig up shit with his hands and that, no matter how hard he tried, he never seemed to be able to get rid of the stench.

He laid on a magnificent banquet that night which ended with a bowl of noodles for each of us. Contemplating his bowl, Yongyu said while it would be an insult to the noodles not to enjoy them, because he was so full it would be an even greater insult to his stomach if he forced them down. When he finally picked up his bowl I asked how he would have reacted if he’d been presented with a bowl of noodles like that during the Cultural Revolution. ‘I would have burst into tears!’, he said.

I was completely taken aback by this remark. That he’d have cried for joy over a humble bowl of noodles was a measure how truly horrific those days had been.

For the next few years I’d make an annual pilgrimage to Beijing to celebrate his birthday. At first, he was living at the Villa of Boundless Lotuses, his country estate. Later he downsized to live in Sun City, a large retirement compound north of the capital. After the Hong Kong protests of 2014, I stopped going to Beijing altogether.

***

***

2009年四月,我在加拿大接到黃老電話,說回港幾天,未能和我見面。我表示八月他過生日時去北京看他。那年,就跟蔣芸等一起去了北京。他見到我很高興,我們之間似乎有說不完的話。他講了許多文革時下放勞動的事,說用手去掏大糞,之後洗手,怎麼洗都覺得有臭味。

那天晚宴,吃得很豐盛。最後來了一碗麵。黃老看著麵說,這麼好的麵,不吃對不起它,吃下去就對不起自己。他終於選擇了對不起自己。我問他,如果文革下放有人捧這碗麵給你,你會怎麼反應?他說,我會哭!

這是我意想不到的回答。一碗麵,就喜極而泣,可見當年是怎樣困頓的生活啊!

我們又連續幾年在他生日前後去北京,從他居住的萬荷堂,到他新遷入的太陽城。2014年後,我們就沒有再去了。

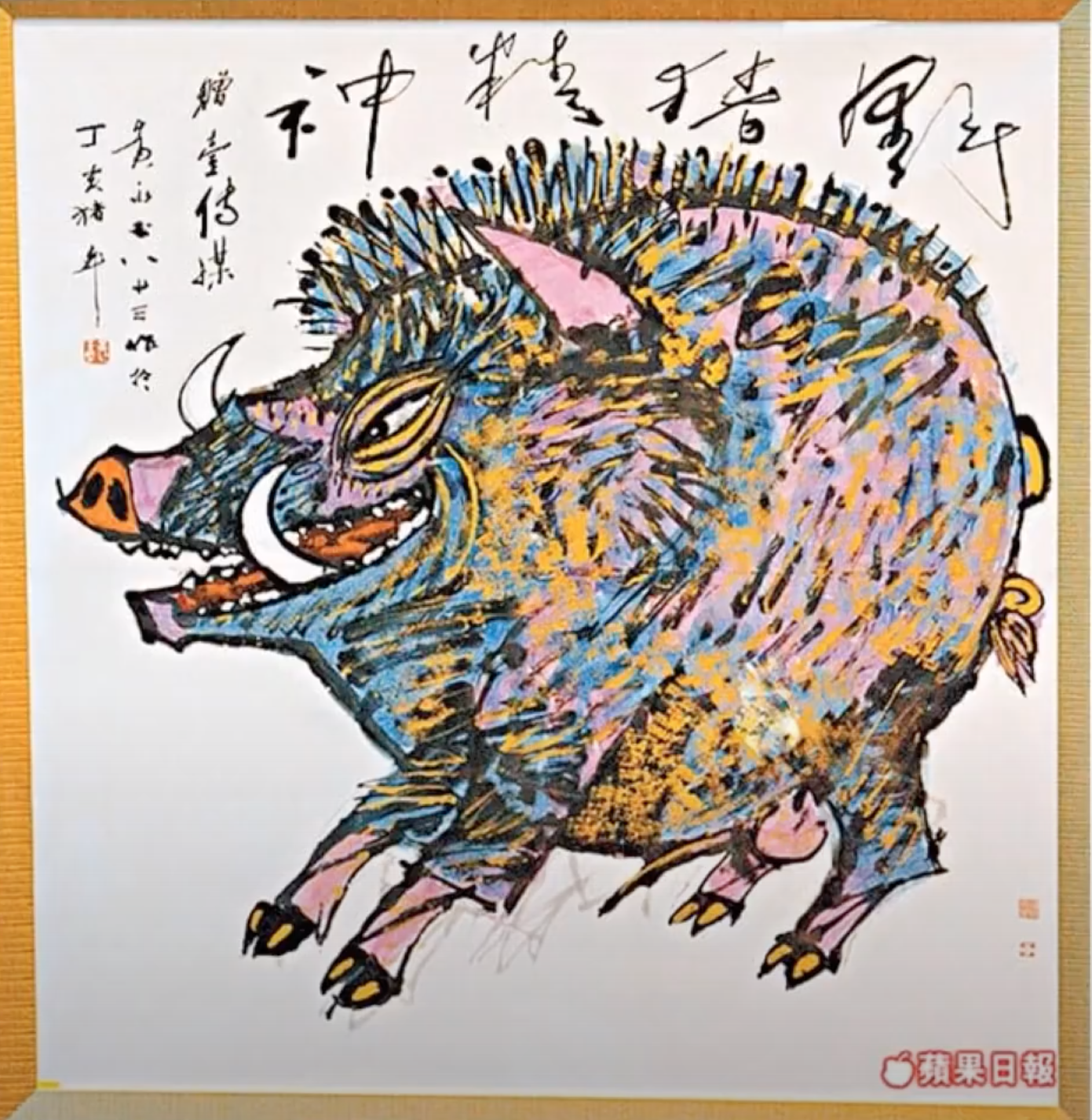

When another Year of the Pig came around in 2007, I was writing editorials for Apple Daily. That year Jimmy Lai hung a painting that Huang Yongyu had made for the Lunar New Year in the foyer of the Next Media building. A ferocious wild boar with protruding tusks, the creature looked as though it was possessed. Yongyu’s calligraphic scrawl read simply ‘Spirit of the Wild Boar’. In my the editorial I wrote to mark the Lunar New Year in Apple Daily I wrote:

‘What precisely is the “spirit of the wild boar”? Wild pigs are known for their ability to run. That’s how the old expression “fast and fearless [like a boar]” came about. The spirit of the wild boar is about valour, being untamed, daring to go out into the world and make one’s own way, a refusal to abide by the rules, a willingness to upturn tradition. A less flattering way of putting it is to say that the spirit of the wild boar is that of the rebel while a more positive spin would be that it’s about being free and unfettered, having a liberated sense of self. It is noteworthy that a number of Chinese characters feature the element ‘swine’ 豕 shǐ, like the words ‘resolute’ 毅 yì, ‘bristling and unrestrained’ 豪 háo, as well as 蒙 mēng, ‘to make a wild guess’ or ‘to deceive’. It just goes to show that from the earliest times the spirit of the wild boar was praiseworthy.’

Even though Huang Yongyu was in Beijing, the painting he did that year for Next Media was his way of saying that the organisation should exemplify a spirit of bravery and boundary breaking.

The ‘Spirit of the Wild Boar’ also summed up the animating energy behind Hong Kong’s long years of creative freedom. In the territory wild boar had long been a protected species until around 2021 when one of the creatures bit a chunk out of a policeman who was in the hills. Overnight, official policy changed and people were encouraged to hunt down and kill the animal. It was a change that was rich in symbolism since it also marked the elimination of Hong Kong’s feral vitality.

[Note: See also Wang Xiaobo’s essay ‘An Unconventional, Independent Pig’, translated by Sebastian Veg, in Outside the Pigsty Looking In, Two Views, China Heritage, 19 February 2019.]

2007年,我開始為《蘋果》寫社論。那年是豬年,我走進壹傳媒大樓,見大堂掛著黃永玉新近贈壹傳媒的畫,畫中是一隻獠牙剛鬣、兇猛神威的野豬,並寫有「野豬精神」四字。於是我在社論中寫:「甚麼是野豬精神?野豬善於奔跑,成語中有『豬奔豨突』,豨特指勇猛的大野豬,豬奔豨突是形容沛然莫之能禦的銳利勇猛之勢。野豬精神,代表的是剛勇、不馴,敢於闖蕩,不依常規,能顛覆傳統。說得不好聽是叛逆,說得好聽是自由自在,是個性解放。古人造字,毅、豪、蒙,都與『豕』相關,說明野豬精神,在古代是具正面意義的。」黃永玉那時已經身在北京,但他仍然以這種剛勇、自由的闖蕩精神向壹傳媒贈畫鼓勵。

實際上,野豬精神也就是香港在充分自由時代的創新精神。香港過去一直以保育政策與野豬共存,但在2021年,卻因野豬咬傷輔警而突然改為對野豬獵殺政策。或許這是一個含有象徵意義的改變:意味著香港過去的自由闖蕩的野豬精神宣告滅絕。

***

Source:

- 李怡,李怡回憶錄 135:與黃永玉的交往,Matters,2022年4月22日, or listen to a recording of Lee Yee’s essay in Cantonese here.

***

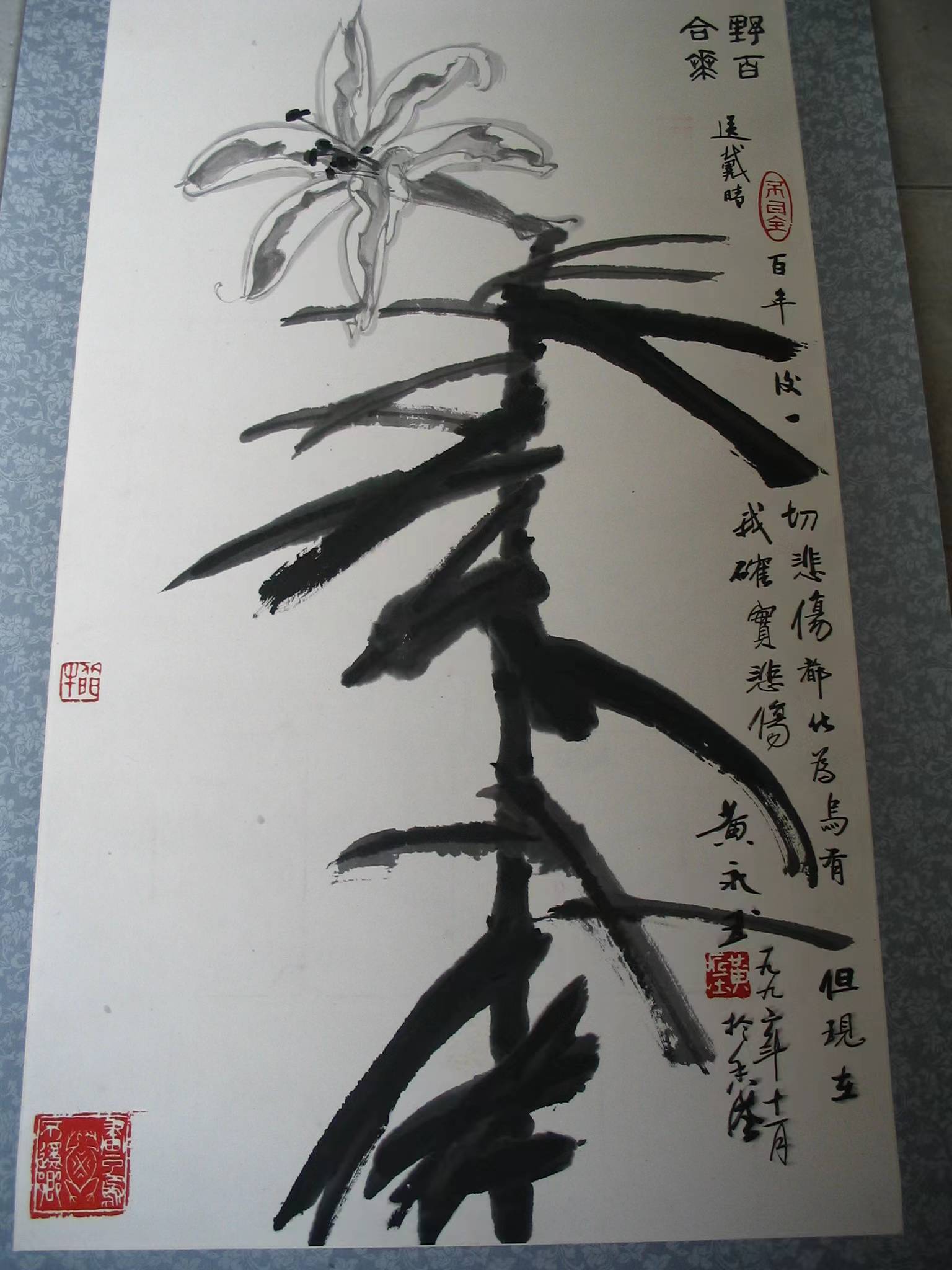

The Sorrow of Wild Lilies

***

The journalist Dai Qing was jailed for her involvement in the Protest Movement of 1989. Following her eventual release, she was allowed to visit Hong Kong, where she encountered Huang Yongyu and Jimmy Lai, both of whom had long admired her work.

The title of the painting that Huang made on that occasion — ‘Wild Lilies’ 野百合花 — refers to Dai Qing’s explosive investigation into the case of Wang Shiwei 王實味, a Party dissident who was beheaded for his 1942 essay ‘Wild Lilies’.

The inscription on the painting reads:

‘All of our sorrow may well be forgotten in a hundred years, but for now it weighs heavily on me.’

Dai Qing used Huang’s painting as the cover illustration for Wang Shiwei and “Wild Lilies”: Rectification and Purges in the Chinese Communist Party, 1942-1944, edited by David E. Apter and Timothy Cheek, Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 1994.