The Fifth Month of the lunar calendar is seen as being a precarious time: the height of summer approaches and pests and pestilence threaten the wellbeing both of people and of crops.

As we noted in Memory Holes, old & new, while there may be the promise of future bounty, an immediate danger is posed by the Five Poisonous Creatures 五毒: snakes 蛇, scorpions 蝎, centipedes 蜈蚣, toads 蟾蜍 and spiders 蜘蛛. It is a time, therefore, to Eliminate the Five Noxious Things 驅五毒. It is also the season to make good on debts and for mourning loss, in particular since, for over a thousand years, it has been associated with the death of the poet Qu Yuan (屈原, third century BCE) by drowning. For this reason it is also known as ‘Poet’s Festival’ 詩人節. In recent years, the ancient story of the poet-courtier exiled by his beloved ruler due to the calumnies of others, something he writes about at length in his poems, has been interpreted by members of the LGBT community as evidence that this day is also the first Gay Valentine’s in history.

In 2008, the re-calibration of public holidays in China saw for the first time in the near sixty years of the People’s Republic traditional holidays afforded prominence. The Double Five Festival (variously 端午節; 端陽節; 雙五節; 龍舟節) was now to be celebrated with a three-day holiday.

From the Song dynasty in the eleventh century this festival had seen politics, literature, romance and agriculture meld as the commemoration of Qu Yuan became associated with the summer solstice of the south and ancient rice fertility rites. As Endymion Wilkinson notes in Chinese History: A New Manual, ‘the main festivals of today are the direct descendants of those of the Song’ (p.525).

David Hawkes, the translator of the early poetry collection Chu ci 楚辭, which he calls The Songs of the South, notes that there were other poets before that collection appeared, ‘but the personality of the great founder and Archpoet Qu Yuan eclipsed them all’. (For this and a detailed study of issues related to Qu Yuan, the authorship of Chu ci and the early history of Chinese poetry, see David Hawkes, The Songs of the South: An Anthology of Ancient Chinese Poems by Qu Yuan and Other Poets, Penguin Classics, 1985).

***

In our New Sinology Jottings 後漢學劄記 the three commemorations in the Fifth Month (May-June in the Gregorian calendar) are interconnected: Duanyang on the Fifth Day of the Fifth Month, the 1st of June International Children’s Day and the Fourth of June.

— Geremie R. Barmé, Editor, China Heritage

30 May 2017

Fifth Day of the Fifth Month of the

Dingyou Year of the Rooster 2017

丁酉雞年五月初五端陽節

- This essay was reprinted as Appendix XI in Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium under the title ‘The Double Fifth Festival and the 35th of May 2022’, China Heritage, 3 June 2022

Dragon-Boat or ‘Upright Sun’ Festival 端陽

Pekinese call the festival of the fifth month the Duanyang, the fifth day (the day on which this festival falls) being the Single Fifth (danwu 單五) of the fifth month. Probably this word dan is a corruption of the sound of the word duan. Every year, preceding and on the Duanyang, noble families give presents to one another of zongzi 粽子 (Note: triangular masses of rice or glutinous millet, wrapped in leaves, which are especially made for this festival), to which are added such things as cherries, mulberries, water-chestnuts, peaches, apricots, cakes of the Five Poisonous Creatures 五毒餅, and rose-cakes. But for offerings to be made to the gods or to the ancestors, simply the zongzi, together with cherries and mulberries, are the proper things to give, the idea being to offer foods of the season.

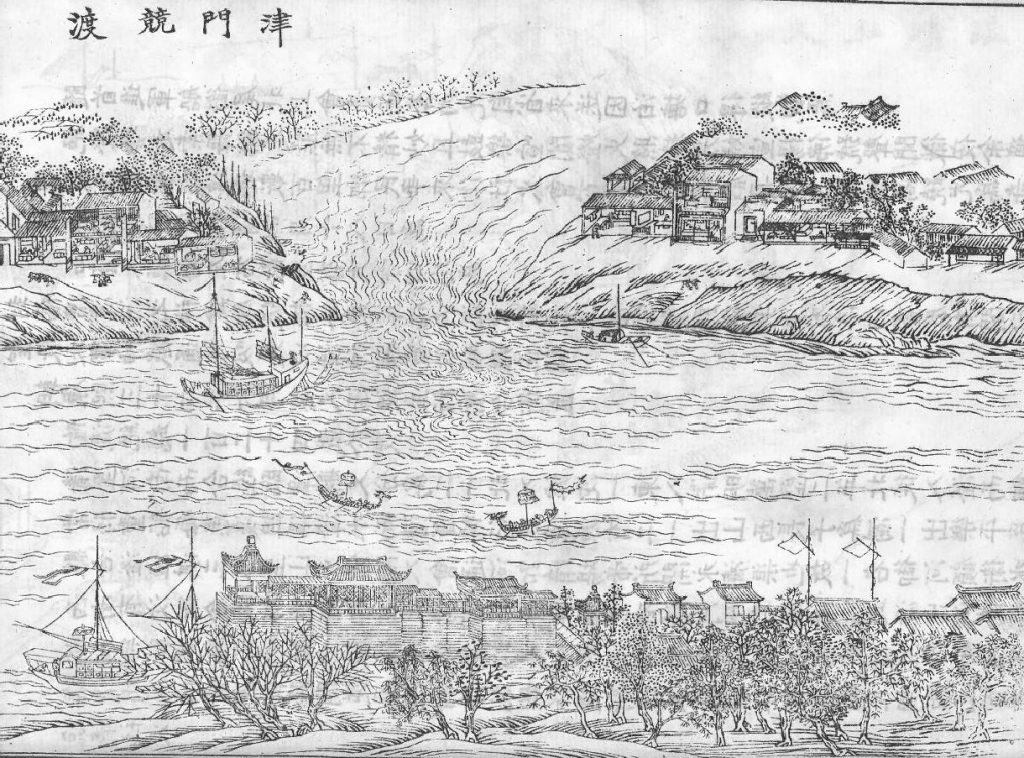

(Translator’s Note: This is probably a myth. The Duanyang festival comes at a time when rain is needed for the growing crops, and the zongzi originally were probably offerings to the scaly dragon, who is the controller of the rain, to induce him to bring rainfall. Likewise races take place in the south, though not so much in the north, between long ‘dragon boats’, which have carved dragon heads and are paddled by many men. This custom supposedly originated much earlier in an attempt, through sympathetic magic, to induce by means of the dragon boat contests, the dragons of the air to struggle together and so send down rain.)

Other Duanyang customs in the former imperial capital included:

- using Realgar Wine 雄黃酒 to paint the foreheads, noses and ears of small children ‘to ward off poisonous creatures’. The character ‘king’ 王, which is supposedly a marking on the forehead of a tiger, was painted on children;

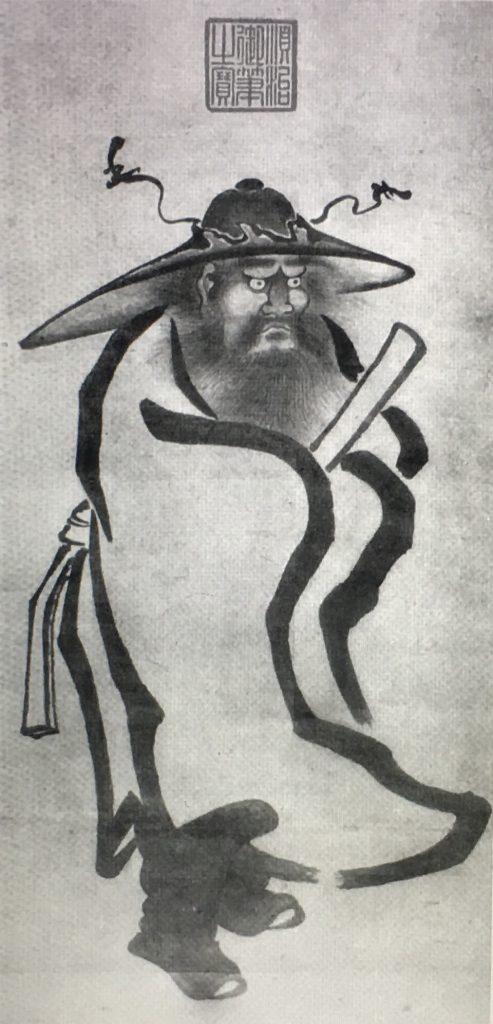

- the devil chaser Zhong Kui 鍾馗驅魔, featured in our discussion of the Year of the Rooster, would also make an appearance, along with the Five Poisonous Creatures, representations of which would be seen as acting as lucky charms;

- leaves of the calamus 菖蒲 and mugwort 艾子 ‘are put up at the sides of gates to avert what is unpropitious. This, too, is a survival from the ancient belief that the mugwort leaves look like a tiger, and the calamus leaves like a sword’; and,

- ‘figures of all kinds of gourds are cut out of colored silks and paper. These are pasted in an inverted position above gates and gate-screens so as to pour out thereby all poisonous vapors. But after the fifth day of the fifth month they are taken off and thrown away. (Note: The gourd, being used by Chinese apothecaries as a receptacle for drugs, suggests the power of healing, and hence is much used at this season as a protection against noxious influences.)’

— from Annual Customs and Festivals in Peking,

as recorded in the Yanjing suishiji 燕京歲時記,

by Tun Li-Ch’en, translated and annotated by Derk Bodde,

Peip’ing: Henri Vetch, 1936, pp.42-45.

Romanised words have been converted to Hanyu pinyin.

***

Archpoet Qu Yuan, Eternal Prisoner of the State

Like so many figures of legend, myth, history and culture, Qu Yuan has become the prisoner of the modern nation-state. In China’s search for wealth and power, the political class (including politically active thinkers and academics) have built on the traditions of state Confucianism to dragoon everything into the service of the state and what is today vaunted as The China Story.

The figure of Qu Yuan, and the poetry ascribed to him, is one of the most prominent examples of such woeful anachronism. The skein of Qu Yuan’s story as ‘China’s first patriotic poet’ is most eloquently summed up by David Hawkes, whose work on Chu ci is worth re-reading every Dragon Boat Festival as the name and reputation of the hapless Qu Yuan is once more evoked by the cloying official media of China.

As with so many aspects of modern Chinese cultural nationalism, the cataclysm of the Sino-Japanese War set the tone. As Hawkes writes in his masterful introduction to The Songs of the South:

During the Sino-Japanese war of 1937-45 it became the fashion to represent Qu Yuan as the great Patriot Poet, even as the People’s Poet. An article by the great liberal scholar Wen Yi-duo was actually published under the second of these titles. It ended with these words:

‘Although Qu Yuan did not write about the life of the people or voice their sufferings, he may truthfully be said to have acted as the leader of a people’s revolution and to have struck a blow to avenge them. Qu Yuan is the only person in the whole of Chinese history who is fully entitled to be called “the People’s Poet”.’

Guo Mo-ruo’s play Qu Yuan, written during ten days in 1942 and compared by his enthusiastic friends with Hamlet and King Lear, accords his subject a similar treatment. Under the People’s Republic this view of Qu Yuan became de rigueur. A little book for high-school students published in 1957 opens with the words, ‘Qu Yuan is the first great patriotic poet in the history of the country’s literature’. An inevitable consequence of this view has been a reluctance to question Qu Yuan’s authorship of any of the works traditionally attributed to him — as if the rejection of even the most improbable of these attributions would in some way diminish his stature — and a revulsion against the highly sceptical attitude which many scholars formerly entertained towards the biography.

In fact these modern attempts to ‘reclaim’ an ancient poet for our own times are, I believe, anachronisms. The idea of Qu Yuan as a great patriot rests on a misunderstanding of the biography. By preferring self-immolation to the pursuit of a career in some other state Qu Yuan was not displaying the sort of loyalty we should associate with an intelligence officer who chooses to blow his brains out rather than defect to a foreign power: loyalty of that kind implies an idea of nationalism totally unheard of in Qu Yuan’s day. Rather, he was demonstrating the chivalrous, aristocratic kind of personal loyalty which Zi Chan would very well have understood but which in the thoroughly ‘liberated’ world of the fourth century B.C. was remarkably old-fashioned.

As for the ‘People’s Poet’, that notion stems from the fact that Qu Yuan is the nominal hero of a popular festival, the Double Fifth or Dragon Boat festival, which is celebrated in South China in the early summer with boat-races and the eating of a kind of glutinous rice-cake called zong-zi 粽子. In fact, as Wen Yi-duo himself was the first to admit, the Double Fifth festival is much older than Qu Yuan and was not associated with him until centuries after his death. The Swedish anthropologist Gøran Aijmer has very plausibly suggested that it was originally a fertility festival associated with the planting-out of the rice. The dragons, i.e. the Nagas of the river, not Qu Yuan, were the original recipients of the offerings, and the boats with their dragon-headed prows represented the beneficent powers who, it was hoped, would bestow fertility on the paddy-fields.

It was the Confucian literati who were responsible in this, as in so many other cases, for foisting one of their own heroes on to a popular local cult, just as the Christian priesthood in Europe succeeded — nominally at any rate — in capturing the old pagan festivals for their own religion. …

The Confucian cult of Qu Yuan… a whole class — that of the office-holding men of letters — found a heroic symbol of itself, one that would serve to shore up a bureaucrat’s flagging self-esteem in times of rejection, unemployment and adversity. To speak out for what one believed to be the right policy, even if one was alone in believing it and when the cost of doing so was demotion, disgrace or even death — that was the scholar-official’s idea of honour. It was, in a way, a curiously literary one, because it meant that he looked no longer towards his contemporaries but towards a literate posterity to judge him. Qu Yuan first gave expression to this heroic ideal and we see it again and again being developed in the later poems of this anthology [i.e., The Songs of the South]. The following lines may not have been written by the great Master himself, but they echo what he more than once stated in the Li sao [離騷, ‘On Encountering Sorrow’]:

The world is muddy-witted;

none can know me;

the heart of man cannot be told.

I know that death cannot be avoided,

therefore I will not grudge its coming.

To noble men I here plainly declare that

I will be numbered with such as you.

世溷濁莫吾知,

人心不可謂兮。

知死不可讓,

願勿愛兮。

明告君子,

吾將以為類兮。

— David Hawkes, The Songs of the South, pp.64-66.

***

Embracing Sand 懷沙

This is the poem which Si-ma Qian quotes in full in his biography of Qu Yuan. ‘Then,’ he adds, after he has finished quoting it, ‘clasping a stone to his bosom, he threw himself into the River Mi-luo and perished.’… The whole poem reads like a greatly expanded restatement of the closing lines of Li sao, in which the poet despairs of finding anyone to join with in ‘making a life in government and resolves to end it all in the river. This was the sense in which Si-ma Qian understood the title of this poem and remains the most obvious way of understanding it today.’

In the teeming late summer

When flowers and trees burgeon,

My heart with endless sorrow laden,

Forth I went to the southern land.

滔滔孟夏兮,草木莽莽。

傷懷永哀兮,汩徂南土。

Eyes strain unseeing into the hazy gloom

When a great quiet and stillness reign.

Disquieted and tormented,

I have met sorrow and long been afflicted.

眴兮杳杳,孔靜幽默。

郁結紆軫兮,離慜而長鞠。

I soothed my feelings, sought my purposes,

Bowed to my wrongs and still restrained myself.

Let others trim square to fit the round:

I shall not cast the true measure away.

撫情效志兮,冤屈而自抑。

刓方以為圜兮,常度未替。

To change his first intent and alter his course

Is a thing the noble man disdains.

I made my marking clear; I set my mind on the ink-line.

My former path I did not change.

易初本迪兮,君子所鄙。

章畫志墨兮,前圖未改。

Inwardly sound and of honest substance,

In this the great man excels so richly.

But when Chui the Cunning is not carving,

Who can tell how true a line he cuts?

內厚質正兮,大人所盛。

巧倕不斲兮,孰察其撥正。

When dark brocade is placed in the dark,

The dim-eyed will say that it has no pattern.

And when Li Lou peers to discern minutest things,

The purblind think that he must be sightless.

玄文處幽兮,矇瞍謂之不章;

離婁微睇兮,瞽以為無明。

What is changed to black;

The high cast down and the low made high;

The phoenix languishes in a cage,

While hens and ducks can gambol free.

變白以為黑兮,倒上以為下。

鳳皇在笯兮,雞鶩翔舞。

Jewels and stones are mixed together,

And in the same measure meted.

The courtier crowd are low and vulgar fellows;

They cannot understand the things I prize.

同糅玉石兮,一概而相量。

夫惟黨人之鄙固兮,羌不知余之所臧。

Great was the weight I carried, heavy the burdens I bore;

But I stand and stuck fast in the mire and could not get across.

A jewel I wore in my bosom, a gem I clasped in my hand;

But, helpless, I knew no way whereby I could make them seen.

任重載盛兮,陷滯而不濟。

懷瑾握瑜兮,窮不知所示。

The dogs of the village bark in chorus;

They bark when they do not comprehend.

Genius they condemn and talent they suspect —

Stupid and boorish that their manner is!

邑犬之群吠兮,吠所怪也。

非俊疑傑兮,固庸態也。

Art and nature perfected lay within me hidden;

But the crowd did not know of the rare gifts that were mine.

Unused materials I had in rich store;

Yet no one knew the things that I possessed.

文質疏內兮,眾不知余之異採。

材樸委積兮,莫知余之所有。

I multiplied kindness, redoubled righteousness;

Care and probity I had in plenty.

But it was not my lot to meet such as Chong Hua;

So who could understand my behaviour?

重仁襲義兮,謹厚以為豐。

重華不可遌兮,孰知余之從容!

It has always been so — this failure of happy meeting;

Through I do not know what can be the reason.

Tang and Yu lived a great while ago —

Too remote for me to long for!

古固有不並兮,豈知其何故也?

湯禹久遠兮,邈而不可慕也?

I must curb my rebelling pride and check my anger,

Restrain my heart, and force myself to bow.

I have met sorrow, but still will be unswerving;

I wish my resolution to be an example.

懲違改忿兮,抑心而自強。

離慜而不遷兮,願志之有像。

Along my road I will go, and in the north halt my journey.

But the day is dusky and turns towards the evening.

I will unlock my sorrow and ease my grief,

And end it all in the Great End.

進路北次兮,日昧昧其將暮。

舒憂娛哀兮,限之以大故。

Luan 亂曰

The mighty waters of the Yuan and Xiang with surging swell go rolling on their way;

浩浩沅湘,分流汩兮。

The road is long, though places dark and drear, a way far and forlorn.

修路幽蔽,道遠忽兮。

The nature I cherish in my bosom, the feelings I embrace, there are none to judge.

懷質抱情,獨無匹兮。

For when Bo Le is dead and gone, how can the wonder-horse go coursing?

伯樂既沒,驥焉程兮。

The lives of all men on the earth have each their ordained lot.

民生稟命,各有所錯兮。

Let my heart be calm and my mind at ease: why should I be afraid?

定心廣志,余何所畏懼兮?

Yet still, in mounting sorrow and anguish, long I lament and sigh.

曾傷爰哀,永嘆喟兮。

For the world is muddy-witted; none can know me; the heart of man cannot be told.

世渾濁莫吾知,人心不可謂兮。

I know that death cannot be avoided, therefore I will not grudge its coming.

知死不可讓,願勿愛兮。

To noble men I here plainly declare that I will be numbered with such as you.

明告君子,吾將以為類兮。

— trans. David Hawkes, The Songs of the South, pp.169-170.

The Chinese text has been added.

A Model for the Ages

Why do the Chinese always go in for this particular brand of tragedy — starting with Qu Yuan, who drowned himself in the Miluo River? Why is it the Chinese feel so much more deeply for tragic heroes like Zhou Enlai, Peng Dehuai, and Hu Yaobang than for ones like Wei Jingsheng? Is the last really worth so much less than the others as a person and a political victim? The answer to my first question should be obvious to everyone: Authoritarianism brooks no opponents, not even well-intentioned, helpful ones. For this reason the tragedies of Hu Yaobang and the rest of them are not personal tragedies but tragedies of the system itself; they are bound to be repeated as long as our authoritarian system remains. All of these tragic heroes have one thing in common: They were loyal but not trusted, they told the truth and were condemned for it.

— Liu Xiaobo, ‘The Tragedy of a Tragic Hero’, trans. G.R. Barmé

Mao Takes to the Waves

Mao Zedong was interested in Qu Yuan, and his fate, from an early age. The tragic ‘Patriotic Poet’ appealed both to his (later revolutionary) romanticism, and to his instincts for practical politics.

Mao’s schooling at Changsha in Hunan province imbued him with the aspirations of a modern activist at the same time as evoking the ancient fate of Chu, and its fallen city (more of which on the Fourth of June). As a student (when he was known by the sobriquet ‘Mr Twenty-eight Strokes’, which was the number of pen strokes that made up his original name) he meticulously copied out the text of Qu Yuan’s ‘On Encountering Sorrow’ 離騷. It was in regular script 楷書, and executed in a cautious hand (although he may have been satisfied with such a loyal display of industriousness, recently a high-school student has pointed out that the Chairman-to-be’s rendition of the 2490 characters in the poem contains no fewer than thirty-two errors in orthography).

Today, Mao’s hand written copy of the ancient poetical text is a celebrated feature of the Chu Cultural Park at Moshan 磨山楚國文化遊覽區 near Wuhan.

In his mature years the Chairman would pen a doggerel verse about the Archpoet (屈子當年賦楚騷,手中握有殺人刀。艾蕭太盛椒蘭少,一躍衝向萬里濤) and he repeatedly referred to Chu ci and its ‘democratic tenor’, urging other Party leaders and cadres to revisit the lyrical classics. With characteristic callousness, he once even quipped that if Qu Yuan hadn’t been ‘sent down to undergo labor reform’ 下放勞動 he would have never composed his timeless masterpiece (thus offering an unexpected insight into his view of rustication).

***

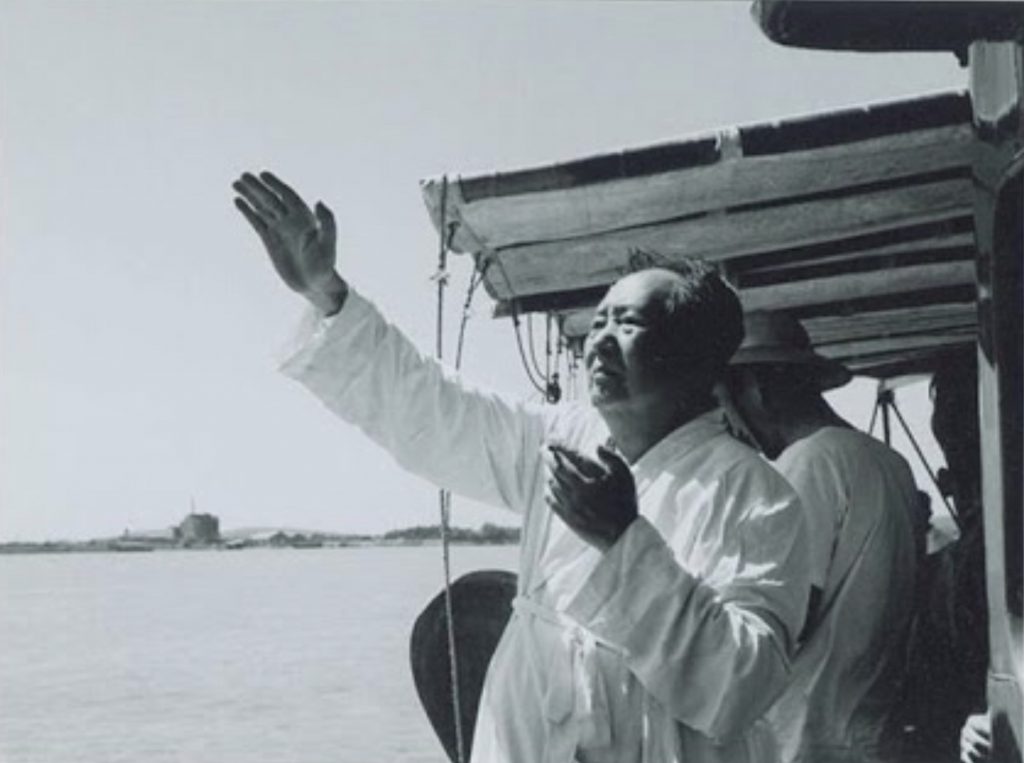

Wuhan was also the site of some of Mao’s greatest performances: his heroic swims in the Yangtze River. He first took the plunge publicly in June and July 1956 and again, ten years later, in 1966. What was at the time hailed as his remarkable crossing of the mighty Yangtze River took place on the cusp of the history of modern China. Mao was at the height of his prestige and enjoyed extraordinary political good will.

In 1956, directed by Mao the Communist Party’s propaganda organs issued a call for ‘A Hundred Flowers to Blossom and a Hundred Schools of Thought to Contend’ 百花齊放,百家爭鳴. This led to an outpouring of grievances and the Party bureaucracy was roundly castigated for the draconian first years of the People’s Republic during which, despite social stability and an improvement in living conditions after years of warfare and strife, judicial murder, zealotry and constant policing had also made the lives of millions a misery. It was at this juncture, buoyed by a confidence that his rule was broadly supported, that the Chairman swam in the Yangtze and wrote one of his most famous poems:

Swimming

to the tune of

Shuidiao getou

June 1956

水調歌頭 · 游泳

I have just drunk the waters of Changsha

And come to eat the fish of Wuchang.

Now I am swimming across the great Yangtze,

Looking afar to the open sky of Chu.

Let the wind blow and waves beat,

Better far than idly strolling in a courtyard.

Today I am at ease.

“It was by a stream that the Master said —

‘Thus do things flow away!’ ”

Sails move with the wind.

Tortoise and Snake are still.

Great plans are afoot:

A bridge will fly to span the north and south,

Turning a deep chasm into a thoroughfare;

Walls of stone will stand upstream to the west

To hold back Wushan’s clouds and rain

Till a smooth lake rises in the narrow gorges.

The mountain goddess if she is still there

Will marvel at a world so changed.

才飲長沙水,

又食武昌魚。

萬里長江橫渡,

極目楚天舒。

不管風吹浪打,

勝似閒庭信步,

今日得寬餘。

子在川上曰:

逝者如斯夫!

風檣動,

龜蛇靜,

起宏圖。

一橋飛架南北,

天塹變通途。

更立西江石壁,

截斷巫山雲雨,

高峽出平湖。

神女應無恙,

當驚世界殊。

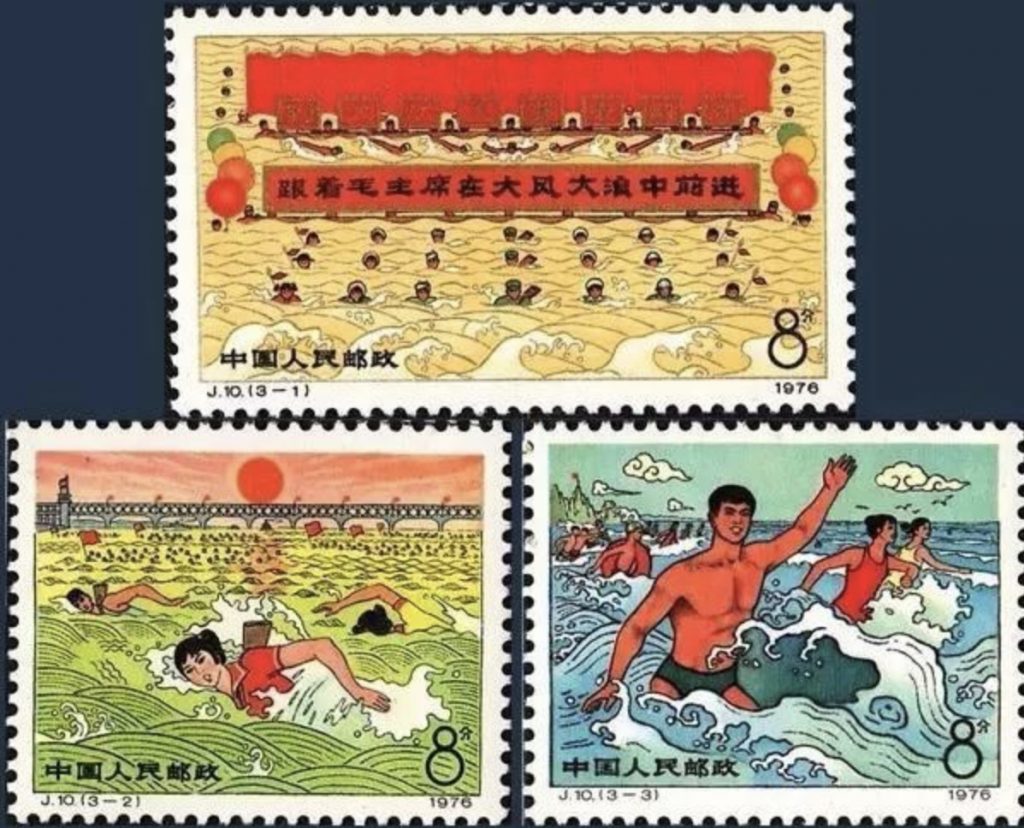

A decade later, in July 1966, following a period of secrecy and a media blackout, Mao suddenly reappeared to swim in the Yangtze River near Wuhan again. He joined in the annual celebrations that now marked the poet-leader of China. He was no failed or frustrated courtier like Qu Yuan, a man who drowned himself in despair of the politics of his day. Rather he was a giant in the water, braving wind and waves to forge ahead in the face of seemingly insurmountable obstacles.

During a one hour swim the seventy-three year-old supposedly travelled fifteen kilometres. The feat was hailed by the Chinese media as nothing less than heroic. The seven hundred million people of China were called on to Open their Eyes and Look to the Future, to Brave the Winds and Ride the Waves and Advance guided by the genius of Mao Zedong Thought 在光輝的毛澤東思想的指引下,七億人民放開眼界看未來,乘風破浪向前進! (for the full, histrionic panegyric in People’s Daily, see here.)

Immediately thereafter, Mao, who had been directing a rebellion against his Politburo colleagues in the early months of the Cultural Revolution from behind the scenes, returned triumphant to Beijing and launched what was in effect a civil war that would only come to an end with his death over a decade later.

For Mao’s 1966 swim in the Yangtze and the politics of the time, see the following excerpt from the 2003 documentary film Morning Sun (click on the following title):

Idly Strolling in a Courtyard

Qu Yuan and the Mountain Spirit

Xi Xi

Translated by Christina Sanderson, from The Teddy Bear Chronicles

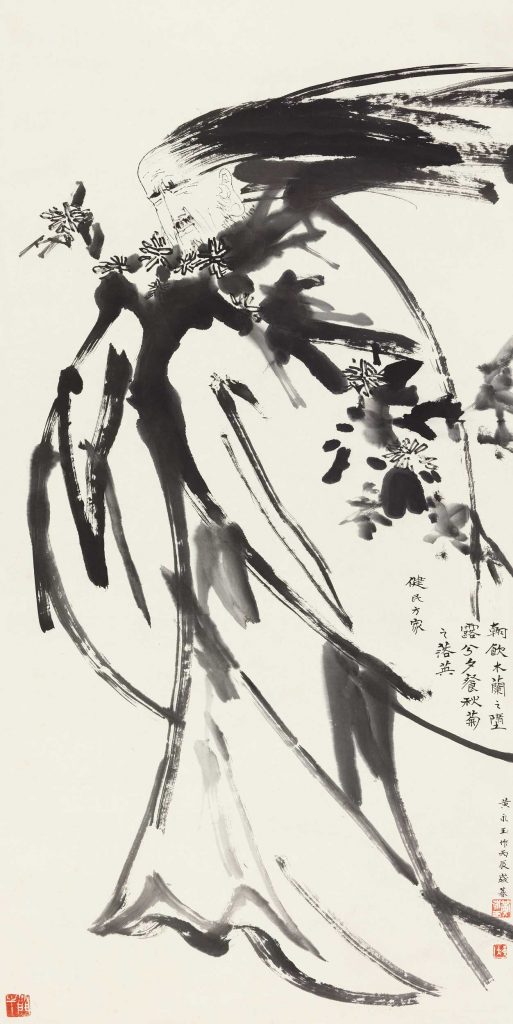

The Mountain Spirit in Qu Yuan’s Nine Songs collection of poems is a beautiful, mountain-dwelling sprite who glances and smiles at people. In her heart there is a lover for whom she yearns day and night, though she can never set eyes on him. In actual fact, the “Mountain Spirit” is an incarnation of Qu Yuan himself. They are one-in-two, two-in-one. 屈原詩篇《九歌》裡的山鬼,是個美麗的山精,會斜眼看人,會對你微笑;她的心中有個朝思暮想的愛人,可惜總是見不到。其實,山鬼就是屈原自己,一而二,二而一

Thinking of his love,

Standing alone in sadness

「思君子兮徒離憂」哪。

The poet-official Qu Yuan is our earliest ancestral master of symbolism. In his thinking he went far beyond his time. In his poetry, sometimes he transforms into a beautiful hermaphrodite, fragrant as herbs. Other times he becomes an orange. Sometimes he directs profound questions to the heavens. 他是象徵派的始祖大師,而且遠遠超越他的時代,有時化身芳草美人,雌雄同體;有時又化身成橘子;有時,對上天發出深刻的問題。

The Mountain Spirit I’ve made is covered all over with fur, tangled in a few artificial vines and flowers, of course. Both she and Qu Yuan are entwined with sweet-smelling plants. Qu Yuan was from the Southern State of Chu, a creative, romantic region, the Chinese artistic centre of its day. Qu Yuan himself explained that his love for strange clothes began in childhood and carried on undiminished into maturity. That is why I’ve made this flamboyant suit for him, made up of a shirt sewed onto a skirt. 我縫的山鬼滿身披毛,當然纏些絲蘿。屈原和她都是芳草滿懷的。屈原是楚人,楚是藝術之都,充滿浪漫的想像。屈原自稱從小喜愛奇服,到老不衰,我於是縫了一襲多彩的深衣給他。「深衣」是上衣和下裳相連的單衣。

There are quite a few different kinds of these one-piece suits. This particular one worn by Qu Yuan is embellished with overlapping waves along the bottom hem, which reveal the coloured stripes of his inner-garment. In ancient China both men and women wore skirts, as trousers had not yet been invented. Despite China’s reputation as one of the greatest civilisations so far as clothing is concerned, the conservative strain has been very strong. Qu Yuan’s contemporary, King Wuling of Zhao introduced clothing from the Hu ethnic minority. This transformed everyday wear from the long Han Dynasty robes to short jackets with narrow sleeves. It also brought about the common wearing of boots. Both of these new trends were better suited to horse riding and archery. Despite the fact that this new style made the nation stronger, something about it nevertheless disgusted the conservative nobility. Their abhorrence to such clothes lay dormant until the king lost power, when it finally erupted. 深衣的欵式也頗多。屈原這件深衣下襬呈波浪交叠弧線,露出彩條子的內裙。古代男女都穿裙,因為並沒有發明褲子。中國號稱是衣冠文明大國,可是另一面,衣飾的保守力量其實也很大。跟屈原同時的趙武靈王引入「胡服」,改漢服為短衣、窄袖,穿長靴,方便騎射,令國家強大,可是也令保守的貴族反感,這種反感埋在心底,到他晚年失權就爆發出來。

Qu Yuan’s weird clothes must have offended the eyes of many, but what was actually so strange about them? His weird clothes were, after all, but one of the many aspects of his eccentric behaviour. In such topsy-turvy times as his, not conforming to trends counted as “odd behaviour”. 屈原的奇服,一定也令許多人看他不順眼。但其實何奇之有呢?奇服不過是他種種奇行之一,在是非顛倒的時代,不肯變心而從俗,從內而外,當然就成為奇行了。

He carried a long sword

Of coloured liuli glass…

「佩長鋏之陸離兮」

Qu Yuan’s sword was a long and very beautiful object. As it was classified as an ornament, it would have been worn with the blade pointing forward. I couldn’t find a real one for the bear, so I’ve substituted a chopstick. It has colourful cloisonné enamel decorations on it. Pretty nice, huh? 屈原的佩劍既長,又艷麗,我找到實物,就用一隻筷子替代,上有景泰藍彩飾,蠻漂亮哦。

Qu Yuan mentioned that he used to wear some kind of tall headdress (guan), but I really don’t know what that looked like. If it was a guan worn in the Han Dynasty, then it was clearly one of the ones with tilted boards. I thought it best to let the poet go freely, humming along the river bank with his hair loose. 屈原說他戴高冠,真不知是什麼樣子,漢人好像很清楚,像一幅斜斜的板子,那恐怕也是漢人的想像。還是讓詩人在江畔披髮行吟吧。

***