The Other China

不朽

Huang Yongyu (黃永玉, 1924-2023), artist, comic essayist and raconteur, passed away on 13 June 2023. He was ninety-nine years old.

Over the years China Heritage has featured Yongyu’s work as part of our annual celebration of the Lunar New Year. In early 2023, we both bid farewell to the Year of the Tiger and welcomed the Year of the Rabbit in Yongyu’s company. See:

- The Tail-end of Tiger Tyranny, 20 January 2023

- Now What? — Greeting the Guimao Year of the Rabbit 癸卯兔年, 21 January 2023

A number of the paintings in his Illustrated Calendar for the 2023 Year of the Rabbit 兔年掛歷, some of which we reproduced, were made from his sick bed in Room 715 at Peking Union Medical College Hospital.

In previous years, too, we included some of Huang Yongyu’s illustrations of the Chinese Zodiac in our own calendar, as was the case at the start of the Year of the Monkey (2016), the Year of the Rooster (2017), the Year of the Dog (2018) and Year of the Tiger (2022).

***

Gladys and Yang Xianyi introduced me to Huang Yongyu in 1981. We were in the living room of their small apartment in the Foreign Languages Press compound in Beijing. Linda Jaivin called it the ‘Baiwan Zhuang speakeasy’, after the suburb in northwest Beijing where FLP was located:

All the excitement of an era could be found in the Yangs’ large, neat if down-at-heel apartment crammed with books, art, alcohol, knickknacks, friends and followers. The core group of Gladys and Xianyi’s friends had known one another since before the revolution of 1949.

That group included Huang Yongyu.

Linda went on to recount details of a trip we made with the Yangs in the summer of 1986 to West Hunan 湘西, Yongyu’s beloved homeland, in 1986. She could just as well as been speaking about Yongyu himself when she observed that Xianyi

… and his peers were, in a sense, the last literati. I don’t believe that any generation in China since has been able to offer up a group of intellectuals with anything approaching the combination of traditional learning; contemporary sensibility; political nous; social grace; and ironic, sharp and yet never vulgar wit that Xianyi and his friends held in their very DNA. They were young when Communism was still a contested idea, when the old society was crumbling and uncertain but the new one with all its certainties and dogmas had not yet been born. Xianyi lived through revolution and then every ideological campaign that revolution, enshrined as government, threw at its people. He witnessed thirty years of social, cultural and economic reform. With his passing, and the passing of his coterie, China has lost more than just a few living legends and national treasures—it has lost a precious part of its cultural memory.

***

In 1983, Yongyu and I happened to be in Hong Kong at the same time. I was about to fly up to Beijing and Yongyu and his wife Zhang Meixi asked me to take a suitcase of odds and ends with me. By way of appreciation, Yongyu gave me a horizontal scroll painting that he had dashed off that morning. It was a large landscape in blue wash with a slash of brown cutting across the top half of the frame representing a mountain range. Two small dots of colour represented waterfowl in the river. He inscribed it with two lines from a quatrain by the Tang-dynasty poet Du Fu:

While you and your fame will fade

The rivers forever onward flow.

爾曹身與名俱滅,

不廢江河萬古流。

It was an elegant expression of the vast chasm separating the artist’s talent and my own modest abilities.

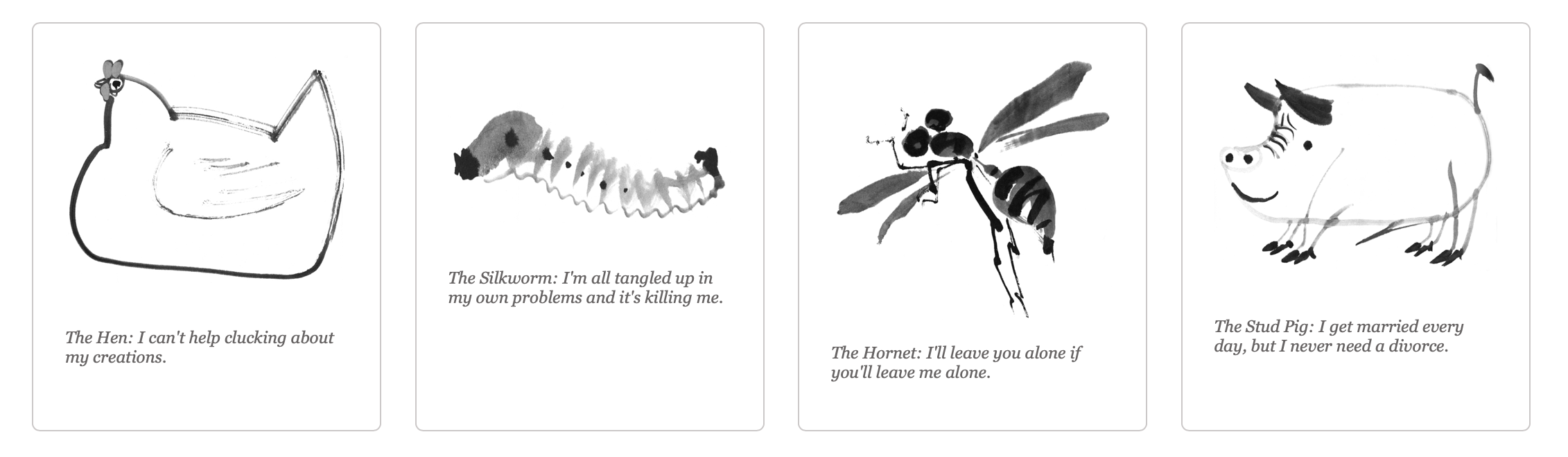

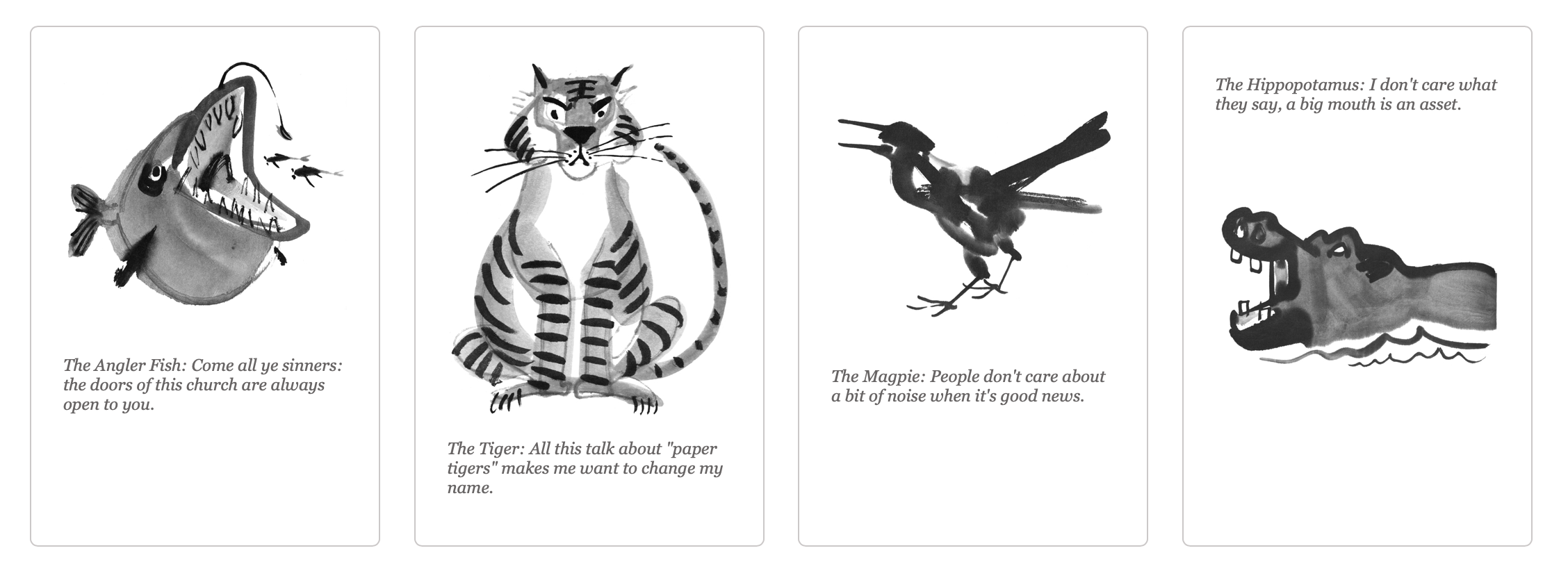

That same day, the artist also granted me permission to use and translate material from Yongyu’s Three Records 永玉三記, a handsomely produced collection of sketches and bons mots recently published by Sanlian Books in Hong Kong.

Subsequently, I have used work from Yongyu’s Three Records in the books Seeds of Fire (1986) and New Ghosts, Old Dreams (1992), the film and website Morning Sun (2003), as well as China Heritage (2016-). Below, we reproduce the introduction to A Can of Worms 罐齋雜記 in fond memory of Huang Yongyu.

The rubric of this chapter in The Other China is 不朽 bù xiǔ, ‘immortality’, a reference to the ‘three immortalities’ 三不朽 sān bù xiǔ of ‘morality, deeds and words’. ‘Ave atque vale’ in the title is a reference to atque in perpetuum, frāter, avē atque valē — ‘and forever, brother, hail and farewell’ — the last line of a famous poem of mourning by Catullus.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

15 June 2023

***

A Can of Worms

Huang Yongyu

translated by Geremie R. Barmé (revised)

A Can of Worms 罐齋雜記 is a collection of aphorisms and witty lines that Huang distributed among his friends; some of the writings made humorous use of Party jargon. In the summer of 1966, these private writings were declared to be counter-revolutionary. Huang was criticized, denounced in public meetings, and severely beaten. — Ed.

My CAN OF WORMS

I started writing these ‘animal tidbits’ during moments of boredom and frustration while in Xingtai in 1964. It was just before the earthquake and I’d been sent to a commune production brigade there as part of the ‘Four Cleans’ Campaign. Eventually, I realised that I had a collection of over eighty works. Some comrades thought they were great fun; they laughed so hard they couldn’t stand up straight. I, too, was pleased with the result and I thought I’d try to publish a small volume of them, with illustrations, when I got back to Peking.

The ten year holocaust started out with over one thousand comrades in the arts being rounded up and confined in the western suburbs of Peking. Although comfortable enough, we were in a state of intense nervous anxiety. It was a time when one could find little joy in life. After a month or so they read our names from a roll and shipped us off to ‘school’ to attend our first exuberant and magnificent struggle meeting, all of which was done in the style of a Roman triumph.

On the second day at ‘school’, I was called into a classroom empty apart from a row of young people seated at the front like a panel of judges. I stood before them in the middle of the room. I noticed that one of them was smiling. It was one of the fellows who had thought A Can of Worms such fun back in 1964, perhaps he was even one of those who laughed so much he couldn’t stand straight… I was ordered to hand over the manuscript.

As a mentally stable person, I have been able to tolerate all manner of abnormality over the past decades. Yet even now, whenever I think of the smile on the face of that young man, a shiver of horror goes through me.

The great master Leonardo da Vinci painted that famous smile on Mona Lisa’s lips, but I wonder if anyone would want to paint a terrifying, haunting smile of the kind that played over the features of that young man? To paint the smile of a Judas, Iago or Haake, smiles that revel in murder, calumny and betrayal.

Over thirty years ago, I saw a cinematic adaptation of Erich Maria Remarque’s novel Arch of Triumph. It starred Ingrid Bergman, and Charles Boyer played her lover Dr. Ravic. That marvelous actor Charles Laughton was Haake, the head of the Nazi secret service. He smiled while torturing Ravic, licking his lips in pleasure.

I must have been too young and innocent then for I thought that evil would have to appear ugly, instantly recognizable for what it was. How could they possibly portray such a terrible man smiling like that? And who would have thought that one day I would come across that very same smile in real life; or that I would have ten long years in which to reflect on their similarities and differences?

The eighty or so aphorisms in A Can of Worms were once a cross which at first I had to bear and upon which I was eventually nailed. Eventually, however, I was taken down from it although my release meant that some people were no longer smiling.

Nonetheless, it is my heartfelt wish that soon these people too will be able to smile or even laugh as other healthy and normal people do; to live like human beings and not as I had to, like a wild beast or an insect. How I hope they will never again attempt to feed off the lifeblood of others or even stir up trouble.

The originals of my sketches were lost to me though, thanks to the efforts of friends and strangers, they have been collected and preserved — some people even copied them from the posters used to denounce me. The amusing thing is that some of the maxims attributed to me and collected in that fashion were not by me at all. You could tell at a glance that they were better than mine. Since I didn’t do them, I’ve had no choice but to leave them out of this collection, albeit with the greatest reluctance.

— 11 April 1983, preface to a work completed in 1964

***

Source:

- Huang Yongyu, Morning Sun website, 2003

***

***