In 2019, the Fifteenth Day of the First Month 正月十五 falls on the 19th of February. It marks the first full moon of the Lunar New Year and it is a festive day generally known as Yuanxiao 元宵, literally ‘First Evening’.

China Heritage celebrates the First Evening of the 2019 Year of the Pig in the company of the writers Wang Xiaobo and Liu Xiaobo, translated by Sebastian Veg.

***

Sebastian Veg is a professor of twentieth-century Chinese intellectual history at the School of Advanced Studies in Social Sciences (EHESS), Paris. He is also an Honorary Professor at the University of Hong Kong. His research has focussed on the history of intellectuals, publications and public spheres. Beyond elite intellectuals and institutionalised knowledge, he is also interested in unofficial texts that circulate among social ‘counter-publics’ in what is known as ‘minjian’ 民間. After completing doctoral research on Lu Xun and May Fourth notions of literature and democracy and following a move to Hong Kong in 2006, he turned to contemporary China. He was Director of the French Centre for Research on Contemporary China (CEFC) in Hong Kong from 2011 to 2015.

Veg’s latest work — Minjian: the Rise of China’s Grassroots Intellectuals, Columbia University Press, 2019 — is devoted to the turn towards society among China’s post-1989 intellectuals (in it, he touches on both Liu and Wang Xiaobo, the authors translated below). He has also published an edited collection titled Popular Memories of the Mao Era — from critical debate to reassessing history, Hong Kong University Press, 2019, as well as having produced a series of articles on cultural and political activism in Hong Kong in the decades since the 1997 handover.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

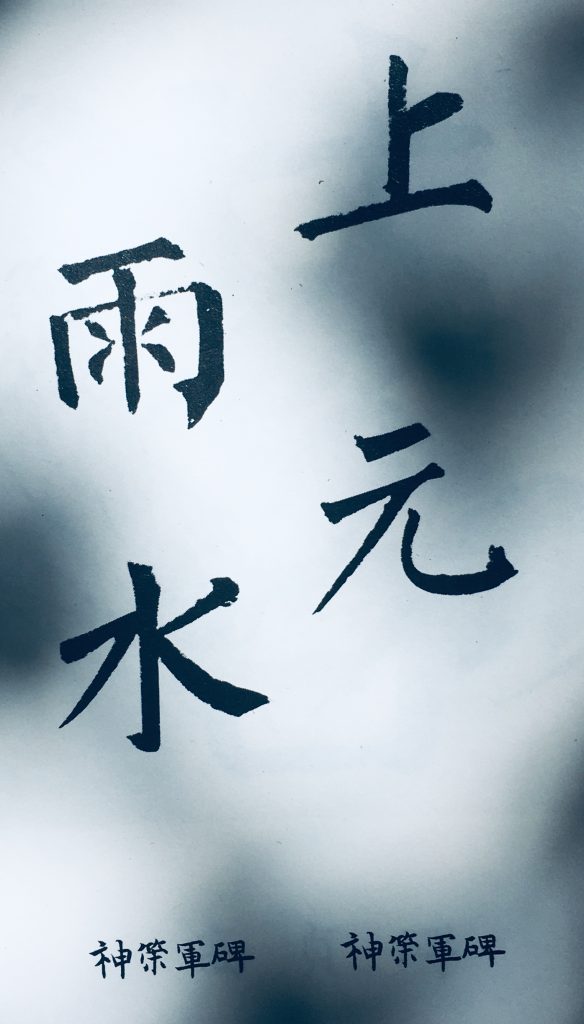

The Fifteenth Day of the First Month of the

2019-2020 Jihai Year 己亥年正月十五

19 February 2019

Out of the Pigsty:

Of Pigs, Swine and Independent Thinkers

Although pigs are a symbol of prosperity and opulence, the Year of the Pig (and the many anniversaries that crowd the Chinese calendar during 2019) inevitably also brings to mind the more unpleasant side of the porcine, traits of personality that in Hong Kong are associated with the dreaded ‘Kong Pig’ 港豬, a term used to describe those who are so occupied with material pursuits that they have no time for politics or society.

Liu Xiaobo (劉曉波, 1955-2017) depicts a similar creature in ‘The Philosophy of Swine’. Writing eleven years after the June Fourth crackdown, Liu was haunted both by the magnitude of the tragedy and the speed with which it had been forgotten. In talking about the memory of the Massacre as being ‘diluted to the point of nothingness’ 被淡化得幾近於空無, Liu may well have been recalling Lu Xun’s 魯迅 prose poem ‘Among faint traces of blood’ 淡淡的血痕中, written in April 1926 to mourn the death of his student, Liu Hezhen 劉和珍.

Liu saw China’s era of peace and prosperity 太平盛世 in the new millennium crowded with a motley crew of old and new ‘courtesans’ — statists, memorialists 奏折派, farewell-bidders to the revolution (such as the philosopher Li Zehou 李澤厚), the new left and the new right — who collectively celebrated the state of political amnesia. To describe the right to ‘be without history’ — a right claimed by this diverse group — Liu employed an expression which, in hindsight, would have an uncanny resonance: it was ‘the right to leave the seat of history vacant’ 歷史缺席權. After being awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2010, Liu Xiaobo’s empty chair at the award ceremony became an Internet meme and remains a powerful symbol.

The extract I have chosen from Liu’s essay ends with a daring comparison between the random confluence of ‘new courtesans’ mired in the moral pigsty of post-Massacre cynicism and the random confluence of participants in the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests themselves. As we contemplate the thirtieth anniversary of the Tiananmen crackdown in the 2019 Pig Year, Liu’s remains a prescient and thought-provoking conclusion.

By contrast, Wang Xiaobo (王小波, 1952-1997) — an altogether more carefree thinker — describes an unconventional pig that he encountered when he was a rusticated youth in Yunnan during the years 1968 to 1971. Wang’s indomitable pig stands out by virtue of its ‘nonchalance’ 瀟灑 — a quality the author often commends in his writing — something that allows the creature to resist the verdict of the political commissar who, having labelled the pig as a ‘Bad Element’ 壞分子, decides to subject the creature to the dictatorship of the proletariat. The pig’s return to nature represents a spirit of resistance shared by those who refuse the attempts of others to organise and control their lives.

The contrast between the two pigs, and the two Xiaobo’s — one the strident moralist and the other, a nonchalant observer — perhaps also leads us to reflect on the validity of our moral judgments over time.

The Lunar New Year is, among other things, a time to exchange messages among friends and colleagues 師友. The translations that follow, which create a dialogue that never took place between the two Xiaobo’s, were undertaken as an ‘irreverent homage’ to Geremie Barmé (who has also returned to nature) and his work. They are a modest contribution to an ongoing conversation between hemispheres North and South, as well as between 泰西 (‘The West’, that is me in France) and 遠東 (‘The Far East’, that is China Heritage in New Zealand).

— Sebastian Veg

***

Further Reading:

- Sebastian Veg, On Wang Xiaobo: The Silent Majority and the Great Majority, China Heritage, 17 April 2017

- Liu Xiaobo, Yesterday’s Stray Dog 喪家狗, Today’s Guard Dog 看門狗, translated by Thomas Moran, China Heritage, 4 January 2019

- Liu Xiaobo, Bellicose and Thuggish — China Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow, translated by Michael S. Duke and Josephine Chiu-Duke, China Heritage, 24 January 2019

An Unconventional, Independent Pig

一隻特立獨行的豬

Wang Xiaobo

王小波

translated by Sebastian Veg

When I was a rusticated youth, I raised pigs and herded cattle. Even if no one takes care of them, these two kinds of animal are fully capable of living their own lives. They roam freely at their leisure, eating when hungry and drinking when thirsty and, when spring comes, they even fall in love. Their standard of living is very low, nothing to boast about. When the humans came, they organised their lives for them: now every cow and every pig’s life was given a main theme. For most of them, the theme was quite tragic: for the former it meant hard labour, for the latter it meant being fattened up for slaughter.

插隊的時候,我餵過豬、也放過牛。假如沒有人來管,這兩種動物也完全知道該怎樣生活。它們會自由自在地閒逛,飢則食渴則飲,春天來臨時還要談談愛情;這樣一來,它們的生活層次很低,完全乏善可陳。人來了以後,給它們的生活做出了安排:每一頭牛和每一口豬的生活都有了主題。就它們中的大多數而言,這種生活主題是很悲慘的:前者的主題是乾活,後者的主題是長肉。

… Here I’d like to mention a pig that was somewhat unique. By the time I started raising pigs, he was already four or five years old. In principle, he was being bred for meat, but he was dark and lean, with two bright, penetrating eyes. The fellow was as nimble as a goat, he could clear his one-metre-high enclosure with an agile leap and could even jump onto the roof of the pigpen, just like a cat — so he was always roaming around rather than staying in his pen. Since all the rusticated youths assigned to raising pigs thought of him as a pet, he was my pet too. That was because he treated us well and let us approach within a few metres of him; while if any others approached, he ran off.

…以下談到的一隻豬有些與眾不同。我餵豬時,它已經有四五歲了,從名分上說,它是肉豬,但長得又黑又瘦,兩眼炯炯有光。這傢伙像山羊一樣敏捷,一米高的豬欄一跳就過;它還能跳上豬圈的房頂,這一點又像是貓——所以它總是到處遊逛,根本就不在圈里呆著。所有餵過豬的知青都把它當寵兒來對待,它也是我的寵兒——因為它只對知青好,容許他們走到三米之內,要是別的人,它早就跑了。

… All in all, the rusticated youths who raised pigs liked him, they liked his unconventional and independent style, and his nonchalant demeanour. The locals weren’t so romantic; they said: this pig is not normal. The leaders hated him, but I’ll get to that in a moment. As for me, I not only liked him, I respected him; regardless of the fact that I was already in my teens, I called him ‘Older Brother’. As I mentioned earlier, this Older Brother Pig could imitate all sorts of sounds. I suspect that he even tried to learn human speech, unsuccessfully. If he had succeeded, surely we could have had a heart-to-heart conversation. But that wasn’t his fault. The sounds made by pigs and humans are just too different.

…總而言之,所有餵過豬的知青都喜歡它,喜歡它特立獨行的派頭兒,還說它活得瀟灑。但老鄉們就不這麼浪漫,他們說,這豬不正經。領導則痛恨它,這一點以後還要談到。我對它則不止是喜歡——我尊敬它,常常不顧自己虛長十幾歲這一現實,把它叫做「豬兄」。如前所述,這位豬兄會模仿各種聲音。我想它也學過人說話,但沒有學會——假如學會了,我們就可以做傾心之談。但這不能怪它。人和豬的音色差得太遠了。

Later, Brother Pig learned how to imitate a factory siren, and that got him into trouble. There was a sugar factory where we were and its siren sounded at midday every day to mark a change of shift. If our division was working in the fields, when we heard the siren we’d stop work and return to our digs. Every morning at ten, Brother Pig would jump onto the roof of the pen and imitate the siren. On hearing it people working in the fields come back to the barracks — a full hour and a-half before the factory siren actually sounded. To be honest, we couldn’t entirely blame him for it; after all, a pig is no boiler and the sound he made was a bit different from the siren, but the locals swore they couldn’t tell them apart.

後來,豬兄學會了汽笛叫,這個本領給它招來了麻煩。我們那裡有座糖廠,中午要鳴一次汽笛,讓工人換班。我們隊下地乾活時,聽見這次汽笛響就收工回來。我的豬兄每天上午十點鐘總要跳到房上學汽笛,地裡的人聽見它叫就回來——這可比糖廠鳴笛早了一個半小時。坦白地說,這不能全怪豬兄,它畢竟不是鍋爐,叫起來和汽笛還有些區別,但老鄉們卻硬說聽不出來。

Because of this, the leadership called a meeting and determined that Brother Pig was a Bad Element who was interfering with the spring ploughing: dictatorial measures were called for — I had already grasped the spirit of the meeting, but I wasn’t particularly worried about him, because if by dictatorial measures they were thinking of using a thick rope and a butcher’s knife, that would never work. It was not for lack of trying, but one hundred men could not hold him down. Dogs were also useless: Brother Pig would shoot away like a torpedo, and a dog couldn’t get within several metres of him.

But this time it was for real, the political commissar took two dozen people with him and a Type 54 pistol; the deputy political commissar organised another dozen people and a rifle used for guarding the crops. They took two different routes so as to be sure to be able to surround and seize Brother Pig. I was conflicted: I should have rushed out with two butcher’s knives to do battle by his side by virtue of our friendship, but the idea seemed too extraordinary to me — after all, he was just a pig. Another reason was that I didn’t dare oppose our leader, I’m afraid this may really have been the crux of the matter.

In the end, I looked on from the sidelines. I admired his calm: he coolly skirted the line of people between the leader with the pistol and the deputy leader armed with the rifle. He let the men shout and the dogs bark, but never strayed from the line. In this way, if the man with the pistol opened fire he would kill the man with the rifle and vice-versa; if they shot at the same time, they would both be dead. As for the pig, being a small target, he would come out of it unscathed. They circled around each other several times, until Brother Pig detected a breach and broke out; he ran off in the most nonchalant way. Later, I saw him again in the sugarcane fields, he had grown tusks. Although he still recognised me he wouldn’t let me approach. His coolness towards me hurt, but I have to commend him for keeping his distance from unpredictable humans, including me.

領導上因此開了一個會,把它定成了破壞春耕的壞分子,要對它採取專政手段——會議的精神我已經知道了,但我不為它擔憂——因為假如專政是指繩索和殺豬刀的話,那是一點門都沒有的。以前的領導也不是沒試過,一百人也治不住它。狗也沒用:豬兄跑起來像顆魚雷,能把狗撞出一丈開外。誰知這回是動了真格的,指導員帶了二十幾個人,手拿五四式手槍;副指導員帶了十幾人,手持看青的火槍,分兩路在豬場外的空地上兜捕它。這就使我陷入了內心的矛盾:按我和它的交情,我該舞起兩把殺豬刀衝出去,和它並肩戰鬥,但我又覺得這樣做太過驚世駭俗——它畢竟是只豬啊;還有一個理由,我不敢對抗領導,我懷疑這才是問題之所在。總之,我在一邊看著。豬兄的鎮定使我佩服之極:它很冷靜地躲在手槍和火槍的連線之內,任憑人喊狗咬,不離那條線。這樣,拿手槍的人開火就會把拿火槍的打死,反之亦然;兩頭同時開火,兩頭都會被打死。至於它,因為目標小,多半沒事。就這樣連兜了幾個圈子,它找到了一個空子,一頭撞出去了;跑得瀟灑之極。以後我在甘蔗地裡還見過它一次,它長出了獠牙,還認識我,但已不容我走近了。這種冷淡使我痛心,但我也贊成它對心懷叵測的人保持距離。

In all my forty years I’ve never encountered another living being that dared ignore the strictures of life like that pig. But, then again, I’ve seen far too many people who want to organise other people’s lives, or who willingly accept being organised. That’s why I cherish the memory of that unconventional, independent pig.

我已經四十歲了,除了這只豬,還沒見過誰敢於如此無視對生活的設置。相反,我倒見過很多想要設置別人生活的人,還有對被設置的生活安之若素的人。因為這個原故,我一直懷念這只特立獨行的豬。

— Sanlian Life Weekly 三聯生活周刊, November 1996

***

Online Source: https://baike.baidu.com/item/一只特立独行的猪/19968237

The Philosophy of Swine

豬的哲學

Liu Xiaobo

劉曉波

translated by Sebastian Veg

The blood-stained terror of June Fourth left China bogged down in a swamp from which it couldn’t extricate itself. Although Deng Xiaoping’s Southern Tour in 1992 broke the deathlike silence that engulfed us, the ‘miraculous soft landing’ achieved by Zhu Rongji’s economic iron wrist only served to postpone the storm of the deep-rooted economic crisis, rather than eradicating any of its systemic causes. Whether in the fields of culture, politics or thought, a poisonous atmosphere served to stifle all voices, immediately followed by the anaemic clamour, rampant corruption and suppression of dissent that heralded an imminent golden age of peace and prosperity.

「六四」的血腥恐怖使中國陷入倒退的泥潭而難以自拔。雖然1992年鄧小平的南巡打破了死一樣的沈寂,但是朱熔基的經濟鐵腕所創造的「軟著陸奇跡」,也只是延緩了深層經濟危機的提前爆發,而並沒有消除任何危機的制度性根源。而在文化上政治上思想上,先是一片肅殺之氣中的萬馬齊喑,繼而是極盡渲染太平盛世的貧血喧囂、腐敗橫行和鎮壓異己。

Amid the massive influx of Hong Kong and Taiwan culture to the Mainland, the explosion of local mass culture, along with the ‘mainstream melody’ extolling the ‘three emphases’ [on study, politics and integrity, under Jiang Zemin] and patriotic education, people seemed absorbed by prosperity and pleasure. Deng Xiaoping used the promise of ‘moderate affluence’ to buy off the memory of the masses: not only were innumerable tragedies of history forgotten, but even the most recent bloodbath was diluted almost to the point of nothingness.

港台文化的大舉登陸、本土的大眾文化的沸沸揚揚,伴著以「三講」和愛國主義為核心的「主旋律」,人們似乎陶然於繁華和享樂之中,鄧小平用「小康」購買著民眾的記憶,不僅歷史上的無數大悲劇被遺忘,就連最近期的慘案也被淡化得幾近於空無。

In this context of nation-wide amnesia and apathy, the elites, under the pretext of indigenising and professionalising scholarship, conspired with the dominant ideology to devise a ‘Philosophy of Swine’. Closely intertwined with the hegemonic discourse of ‘taking economic development as the centre’, it uses all knowledge as evidence to support the ‘philosophy of moderate affluence’ underpinning stability and economic growth to thereby rationalise a form of escapism that extols the ‘right to be without history’. It is, in a word, the rationale for allowing pigs to eat their fill until they nod off and, upon waking, to eat their fill all over again. At most, they might linger at the stage of lustfulness arising from material comfort, but never again will they entertain inappropriate ambitions.

在這種全民族的遺忘和麻木之中,精英們形成了一股以學術化本土化為藉口的與主流意識形態共謀的「豬的哲學」。它緊緊地攀附於「以經濟建設為中心」話語霸權,把所有的智慧都用於論證怎樣才能保持穩定以發展經濟的「小康哲學」,論證「歷史缺席權」式的逃避的合理性,一句話,就是論證怎樣讓豬們吃飽了就睡,睡醒了就吃,至多讓它們停留在飽暖思淫欲的階段,再不能有其它的非分之想。

In the context of China’s current system, any resolve to reform can only be a political resolve, any theoretical discourse in the humanities must reply immediately to the dictatorial coercion exercised by the system itself. How can economic reform be depicted as a ‘male virgin’ untainted by politics? How can pompous foreign theory be used to make an argument for cowardice?

在中國目前的制度背景下,任何改革決策都是政治決策,任何人文理論的話語都必須對這一制度的獨裁性強制在場作出回應。怎麼就能把經濟改革弄成不受任何政治污染的處男呢?怎麼就能冠冕堂皇地以各種洋理論來為懦弱辯解呢?

In economics the statist theory of a ‘strong centre’ and its caucus of consultants, the ‘memorialist party’ of neutral economics; in politics the theory that [it is time to bid] ‘farewell to revolution’, the new left and pro-market factions; in culture the almost all-encompassing unbridled nationalism and indigenisation of scholarship … they are all constituent parts of the rising cynicism of the Philosophy of Swine.

經濟上的「強中央」的國家主義理論和「幕僚派」、「奏折派」的中立經濟學;政治上的「告別革命論」、「新左派」和「市場派」;文化上的幾乎覆蓋所有角落的瘋狂的民族主義和學術的「本土化」……皆是犬儒化的豬哲學的組成部分。

What is indeed intriguing is that these elites from the Five Lakes and Four Seas have assembled without any common goal or premeditation; they have congregated involuntarily, coincidentally, spontaneously inside the pigpen, just as unwittingly as, eleven years ago, some of them became embroiled in the ‘1989 Movement’.

耐人尋味的是,這些來自五湖四海的精英們為了一個共同的目標走到一起,並沒有事前的預謀,而完全是不由自主、不約而同,自發地走進了「豬圈」,想控制都控制不住,如同他們中的一些人在十一年前自發地捲入「八九運動」一樣。

— Tendency 動向, September 2000

***

Online Source: http://www.liu-xiaobo.org/blog/archives/6026