Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium

Appendix XII

治

On 1 July 2017, China Heritage marked the twentieth anniversary of mainland China extending suzerainty over Hong Kong with a series of translations, commentaries and art works. (See Leung Ping-kwan (P.K.) 梁秉鈞, et al, Cauldron 鼎, China Heritage, 1 July 2017.)

Five years later, on 1 July 2022, we note the twenty fifth anniversary of Beijing’s takeover of Hong Kong, and the effective dissolution of the limited freedoms that Hong Kong enjoyed under what was known as the One Country, Two Systems policy framework. We do so by offering three essays by the veteran journalist Lee Yee 李怡 (李秉堯), founding editor of The Seventies Monthly 七十年代月刊 (later renamed The Nineties Monthly).

The first ‘What Nineteen Years Have Taught Us’ was published in Apple Daily on 1 July 2016 and the second, ‘The Mission of Our Times in Hong Kong’, appeared on 29 June 2017. Both were re-issued by Lee Yee on his Facebook page on 1 July and 29 June 2022 respectively. Here we are also reprinting from our own Hong Kong archive Lee’s reflections on the Hong Kong Prospect Institute 香港前景研究社, which he founded with a number of academics and social activists in 1982, and a comment on Sze-yuen Chung [鍾士元, 1917-2018], a senior civil servant who attempted to add a Hong Kong voice to the Sino-British negotiations concerning the future of the British crown colony in the early 1980s. Those efforts were in vain. After 1 July 1997, commentators and analysts like Lee Yee would often refer to Hong Kong as having ‘fallen’ 淪陷 lúnxiàn to the Communist rulers in Beijing.

After having lived and worked in Hong Kong for more than seventy years, Lee Yee relocated to Taiwan in mid 2021.

The 1st of July 2022 marks the halfway point of the ‘fifty years without change’ proffered by Beijing in its negotiations with the British government in the 1980s. The changes began immediately following the 1 July 1997 handover and have continued apace during the Xi Jinping era. From 1979, Lee Yee was something of a Cassandra. From the earliest days, Lee Yee warned readers about what the future held but, like the mythical Trojan prophet, it was his fate not to be believed.

For more on Hong Kong in China Heritage, see Hong Kong Apostasy. This dolorous commemoration is an appendix in the series Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium. See also ‘You can’t rebel, you can’t start a revolution, and you can’t be independent.’ — How Ni Kuang saw the future of Hong Kong, China Heritage, 4 July 2022.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

1 July 2022

***

Further Reading:

- Lee Yee 李怡, ‘Back in the Year — Hong Kong 1984’, China Heritage, 31 July 2019

- Ni Kuang 倪匡, ‘The Nobility of Failure’, China Heritage, 14 August 2019

- Xu Zhangrun 許章潤 & Yi-Zheng Lian 練乙錚, ‘A Protracted People’s Struggle’, China Heritage, 14 September 2019

- The Extreme Minority Singers of Featherston, ‘Singing for Hong Kong’, China Heritage, 24 September 2019

- Lee Yee 李怡 & To Kit 陶傑, ‘China, The Man-Child of Asia’, China Heritage, 26 September 2019

- Jason Wong Yiu-pong 黃耀邦, ‘Voiceless, but Not Silent’, China Heritage, 5 October 2019

- Lee Yee 李怡 & The Editor, ‘Jimmy Lai, the Twilight of Freedom & the Dawn of “Legalistic-Fascist-Stalinism” 法日斯 in Hong Kong’, China Heritage, 12 August 2020

- Tsang Chi-ho 曾志豪 and Ng Chi Sam 吳志森 (RTHK), et al, ‘Hong Kong & 講耶穌 gong2 je4 sou1’, China Heritage, 6 October 2020

- Lee Yee 李怡, ‘I Hereby Cancel Myself’, China Heritage, 24 April 2021

- Lee Yee 李怡, ‘Lee Yee on the Demise of Jimmy Lai’s Apple Daily’, China Heritage, 23 June 2021

- Lee Yee 李怡, ‘Apple Daily, “The Four Noes” & the End of Chinese Media Independence’, China Heritage, 24 June 2021

- 眼鏡中央電視台, ‘香港淪陷25年!’, 1 July 2022

***

Our humble bellies have ingested a surfeit of treachery,

eaten their fill of history, wolfed down legends —

and still the banquet goes on, leaving

an unfilled void in an ever-changing structure.

Constantly we become food for our own consumption.

For fear of forgetting we swallow our loved ones,

we masticate our memories and our stomachs rumble

as we look outwards.

— from P.K. Leung 梁秉鈞, ‘Cauldron’ 鼎

Translated by John Minford and Can Oi-sum

***

What Nineteen Years Have Taught Us

十九年的深刻教訓

Lee Yee 李怡

1 July 2016

Translated by Geremie R. Barmé

According to the Communist-Hong Kong authorities, 1 July 2016 marks the nineteenth year of Hong Kong’s ‘return’ to the People’s Republic of China. The younger generation of Hong Kong localists do not recognise this ‘return’ [回歸] at all; that’s because, since the territory of Hong Kong was ceded to the British by the Qing empire in the nineteenth century, this place has actually has a much longer history than that of the Chinese People’s Republic. Furthermore, from 1949, the PRC had at no point exercised suzerainty over the territory, so that’s why, on 1 July 1997, Hong Kong did not in fact ‘return’ to China.

There’s another reason why new-era localists do not recognise 1 July 1997: it’s because the negotiations between Beijing and London and the resulting agreement they reached at no point entertained the wishes of the actual people of Hong Kong. When Great Britain delivered Hong Kong to the Communists it merely transferred sovereign control over the territory. In other, less bland, words, 1 July 1997 marks the second colonisation of Hong Kong.

Prior to 1997, no one spoke about these things in such terms. In those days, although people were quite happy to claim their identity as being that of ‘Hong Kong people’, by in large they did not necessarily reject the idea that they were Chinese. When they travelled overseas, most people would identify themselves as being ‘Hong Kong Chinese’. Over the last nineteen years, however, Communist officials have repeatedly claimed that Hong Kong has enjoyed numerous special privileges and, in a recent interview, [the Beijing-appointed Chief Executive of Hong Kong] C.Y. Leung observed that ‘Beijing has been very good to Hong Kong in many ways’. Leung went on to point out that, actually, many Mainlanders were quite unhappy with the situation. Given such indulgence, Leung hinted, surely the people of Hong Kong should identify more strongly with ‘China’ that ever before. In fact, the opposite is true. According to opinion polls, Hong Kong people are increasingly less, not more, likely to identify with China. A neologism has even appeared in English-Language dictionaries: ‘Hongkonger’. Many now disavow the old identity of ‘Hong Kong Chinese’.

In that same interview C.Y. Leung also declared that not only is Hong Kong an ‘anti-communist city’, it’s an attitude that increasingly finds expression in being ‘anti-Chinese’. All of this serves to foster further support for ‘Hong Kong independence’.

In years gone by, Hong Kong Democrats may have been anti-communist but they were not anti-China. They believed in the reversal of the official verdict regarding the Fourth of June [1989] and the eventual creation of a democratic China. These views reflected an in-principle opposition to the tyranny of the Chinese Communist Party, but their quest for a democratic China was grounded in their identity as Chinese and a recognition that Hong Kong was part of China.

Over the past nineteen years, however, the people of Hong Kong have learned that China is indistinguishable from the Communist Party; moreover, according to Beijing, ‘patriotism’ is merely a smokescreen for ‘unquestioning fealty to the Communist Party’. They have also come to learn that Hong Kong people and Mainlanders have fundamental differences. Are Hong Kong people ‘anti-communist’? I would venture that they are more than that; they aren’t ‘anti’ so much as desirous of being in charge of their own affairs. They want autonomy.

今天7.1,中港共政權說是回歸十九周年,新一代本土派不認同這是回歸,因為香港是從大清帝國手上割讓和租借給英國的,香港歷史比中華人民共和國更長,後者既從未擁有過香港主權,也就沒有回歸這回事。新一代認為九七是在沒有取得香港居民同意下,由英國把主權轉移給中共國,所以是主權轉移。更尖刻的說法,是第二次殖民。

這種論述,在九七前後是不存在的。那時香港大多數人儘管都很執着「香港人」這個身份,但並不抗拒自己是中國人,到了外國,會跟外人說自己是「HongKong Chinese」(香港中國人)。經過十九年,中共官員一直說給香港許多優惠,日前梁振英接受專訪提到,「北京在很多方面給予香港單方面厚待」,甚至說因此引起大陸人不滿。既是厚待,香港人對中國的認同感應該比九七前後更強才是,然而正好相反,民調顯示,香港人對中國人的認同感持續下降,英文詞典有了新詞:Hongkonger,許多香港人都不再稱自己是「HongKong Chinese」了。

梁振英在日前的訪問中說,香港是一個反共城市,而部份反共行為或情緒已演變為「反中」及傾向「港獨」的立場。

以前香港的民主派都是反共不反中,平反六四或建設民主中國,都是反對中共的暴政統治,要促進中國民主,但立足點仍然是中國人,接受香港是中共國一部份。但十九年的現實演進,告訴香港人「共」與「中」是分不開的,在中共詞典裏,「愛國」只是「愛黨」的表面包裝。而在整個中國和中國人身上,都散發與香港和香港人不同的氣味。是否演變成「反中」呢?也許比「反中」更徹底,就是連反都不反了,而是要自顧自,尋求自主。

***

Original Source:

- excerpted from 李怡, ‘十九年的深刻教訓’, 《蘋果日報》, 2016年7月1日

It’s About Time People Woke Up

夢醒時分

Lee Yee 李怡

29 June 2017

Translated by Geremie R. Barmé

I read the following on the Chinese Internet:

‘I was invited to a meal and there was a judge among the other guests. I couldn’t resist asking him:

“You often see a line in a judgement following sentencing that says that the convicted person has also had their political rights stripped for so many years. What does that mean exactly?”

‘He explained that: “When a criminal is deprived of their political rights it means that not only can’t they vote or be elected to office, they also no longer enjoy freedom of speech, the press, assembly, association, procession and demonstration [as stipulated in Article 35 of the Constitution of the People’s Republic of China.]

‘I then followed up by asking whether he, as a judge, enjoyed any of those rights himself. After a moment’s thought, the judge replied: “I don’t either”.’

Liu Xiaobo was jailed for having participated in a petition calling on the Communist authorities to honour the constitution and respect freedom of speech, human rights and universal suffrage. The demands that Liu and others made in Charter 08 — a manifesto released on 10 December 2008 to mark the sixtieth anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights [and which was initially signed by 303 Chinese intellectuals and human rights activists] — roughly accorded with what is already stipulated in the Chinese constitution. Nonetheless, the Beijing authorities arrested Liu and eventually found him guilty of ‘inciting the subversion of state power’. He was sentenced to eleven years in jail. The judgement also stripped him of his ‘political rights’ for a further two years — rights which, as we just noted, not even that Chinese judge enjoys.

在大陸網頁看到這樣一段:「飯局碰一法官,忍不住問他:『經常看到判決書說誰誰判刑幾年,剝奪政治權利幾年,是啥意思?』他解釋道:『剝奪政治權利就是剝奪犯人的選舉權和被選舉權,還有言論、出版、結社、集會、遊行、示威的權利。』我說:『法官,你本人有這些權利嗎?』法官想了想說:『我也沒有。』」

劉曉波惹來牢獄之災,源於他在2008年12月10日,亦即《世界人權宣言》紀念日發表《零八憲章》,主要是呼籲中共當局按憲法實現言論自由、人權和普選,其實就是呼籲實行憲法賦予的政治權利。卻因此被中共以煽動顛覆國家政權罪判處有期徒刑11年,剝奪連法官都沒有的政治權利兩年。

How is it that an appeal for the government to honour its own constitution was construed as ‘inciting the subversion of state power’? That’s because if the citizens of China really exercised their constitutional rights regarding freedom of speech, the press, assembly, association, procession and demonstration they could, in effect, be able to cramp the unbridled power wielded by China’s autocratic rulers. It therefore holds that any attempt to limit the universal rights of the autocrats would be tantamount to subversion of state power. Although the activism of Liu Xiaobo et al was limited to the written word, as far as the power-holders were concerned those words were also, ipso facto, an incitement.

Xi Jinping has claimed that Beijing will faithfully and fully implement the One Country, Two Systems policy framework without either deviation or distortion. A claque of Hong Kong toadies has gathered in a murmuration. While Beijing’s interpretation of the framework is supposedly a constant, stipulations regarding citizens rights found in Hong Kong’s Basic Law are actually subject to change. Freedom of speech, for instance, does not cover the right of people to discuss Hong Kong independence; nor does freedom of association vouchsafe anti-government demonstrations like the Occupy Movement; moreover, voting rights are subject to Beijing’s stage-management and oversight. For those empowered as the legitimate interpreters of the word and spirit of the Basic Law, such caveats do not, however, count as being deviations or distortions. As for the constant encroachment and expansion of Beijing’s power in Hong Kong, well that, too, is no distortion for it reflects fealty to One Country, Two Systems. In other words, don’t get bent out of shape over it.

要求按憲法實行公民的權利,怎麼就是顛覆國家政權呢?因為:人民有言論、出版、集會、選舉等權利,就意味專政掌權者的權力受到一定的約束。約束掌權者的權力,還不是要顛覆政權?儘管只有言論並無行動,但在掌權者眼中,言論就是煽動。

習近平講實踐一國兩制不走樣、不變形,應聲蟲也跟着講。但不走樣、不變形只是指中央的權力不走樣變形,而不是《基本法》規定的公民權利不走樣變形。言論自由不包括可以談論港獨的自由,集會自由不包括大型集會反對政府的佔領運動的自由,選舉權和被選權是在中共的「集中指導」下的選舉。這都是掌《基本法》解釋權者認為的不走樣變形。而中央權力的不斷擴大,也不是走樣變形。

Liu Xiaobo is a pacifist who, at the tail end of the 1989 Protest Movement in Beijing organised a group known as the ‘Four Gentlemen of Tiananmen’. On the morning of 4 June, they took it upon themselves to negotiate with the armed forces that had surrounded the square to allow the protesters to withdraw peacefully. It prevented a bloodbath. In the final statement that he made at his trial for his involvement in Charter 08, Liu Xiaobo declared that ‘I have no enemies’. ‘I have no enemies, and no hatred’, he declared.

‘None of the police who have monitored, arrested and interrogated me, the prosecutors who prosecuted me, or the judges who sentence me, are my enemies.’

Liu went on to say that:

‘I look forward to [the day] when my country is a land with freedom of expression, where the speech of every citizen will be treated equally well; where different values, ideas, beliefs, and political views … can both compete with each other and peacefully coexist; where both majority and minority views will be equally guaranteed, and where the political views that differ from those currently in power, in particular, will be fully respected and protected; where all political views will spread out under the sun for people to choose from, where every citizen can state political views without fear, and where no one can under any circumstances suffer political persecution for voicing divergent political views. I hope that I will be the last victim of China’s endless literary inquisitions and that from now on no one will be incriminated because of speech.’

劉曉波是一個和平主義者,遠在八九民運的晚期,他就組織「天安門四君子」,與當局商談,讓天安門的學生和平撤退,避免了部份屠殺。在因08憲章受審的法庭上,他作的最後陳述是「我沒有敵人」。他說:「我沒有敵人,也沒有仇恨。所有監控過我,捉捕過我、審訊過我的警察,起訴過我的檢察官,判決過我的法官,都不是我的敵人。」他說:「 我期待我的國家是一片可以自由表達的土地,在這裏,每一位國民的發言都會得到同等的善待;在這裏,不同的價值、思想、信仰、政見……既相互競爭又和平共處;在這裏……每個國民都能毫無恐懼地發表政見,決不會因發表不同政見而遭受政治迫害;我期待,我將是中國綿綿不絕的文字獄的最後一個受害者,從此之後不再有人因言獲罪。」

This statement resonates with sentiments expressed by Martin Luther King in his ‘I Have a Dream’ speech, although Liu was confronting a completely different kind of political environment. There was outrage in China online regarding the treatment of the American student Otto Warmbier by the North Koreans. He was only finally released on medical grounds when he was already at death’s door. In their grief over this case, some Mainland netizens were critical of Liu Xiaobo’s ‘no enemies’ and non-violent stance. As one observed:

‘If “I have no enemies and no hatred” holds sway then the whole society should just give in and be obedient. Forget about meaningful reform, and give up on human rights.’

The way the power-holders react to statements like ‘I have no enemies, I have no hatred’ is to act as though enemies are lurking everywhere and that hatred should only be allowed to proliferate. Anyone who talks about preserving the rights of Hong Kong people as guaranteed in the Basic Law is treated like an enemy and non-violent protests for the democratic rights of Hong Kong people are regarded as a real threat.

Surely the fate of Liu Xiaobo should be enough to shake people out of their complacency.

[Note: Liu Xiaobo died in custody two weeks after this essay was published.]

他彷彿在說着馬丁路德金的《我有一個夢》,但他面對的卻是截然不同的政權。當他像北韓虐待美國大學生瓦姆比爾那樣,在涉臨死亡才被釋放「保外就醫」,大陸網民在悲憤中就有人反思劉曉波的「我沒有敵人」和非暴力抗爭路線,「如果『我沒有敵人,我沒有仇恨』,那整個社會聽話就好,談甚麼變革,談甚麼人權」。

掌權者對「沒有敵人,沒有仇恨」的回應,是到處都是敵人、到處散播仇恨。維護《基本法》只要講香港人的權利,就是敵人;非暴力抗爭只要是爭市民的民主,就是敵人。

劉曉波的事,至少應該讓我們更清醒吧。

***

Original Source:

- 李怡, ‘夢醒時分’, 《蘋果日報》, 2017年6月29日

***

More on and by Liu Xiaobo:

- Liu Xiaobo interview with Bai Jieming (Geremie Barmé), December 1986, subsequently published under the title 中國人的街坊在自我覺醒——與個性派評論家劉曉波一席談 in The Nineties Monthly 九十年代月刊, March 1987

- G. Barmé, ‘Confession, Redemption, and Death: Liu Xiaobo and the Protest Movement of 1989’, 1990 & in Chinese at: 忏悔、救赎与死亡:刘晓波与八九民运, 石默奇译

- Liu Xiaobo, ‘The Tragedy of a “Tragic Hero” ’ and ‘At the Gateway to Hell’, translated by Barmé in Geremie Barmé and Linda Jaivin, eds, New Ghosts, Old Dreams: Chinese Rebel Voices, New York: Random House, 1992

- G. Barmé, China’s Promise, China Beat, 10 January 2010

- Barmé interviewed by Philippe Grangereau on Liu Xiaobo’s Nobel Prize, Libération, 8 October 2010

- Liu Xiaobo, No Enemies, No Hatred: Selected Essays and Poems, Perry Link, Tienchi Martin-Liao, Liu Xia, eds., Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013

- 劉曉波文選, 獨立中文筆會 (select essays by Liu Xiaobo, in Chinese)

- ‘Mourning’, 30 June 2017

- ‘The Pity of It’, 14 July 2017

- An Interview, 15 July 2017

- Liu Xiaobo, ‘The Specter of Mao Zedong’ (1994), reprinted in ‘Prelude to a Restoration: Xi Jinping, Deng Xiaoping, Chen Yun & the Spectre of Mao Zedong’, 20 September 2021

- ‘Liu Xiaobo on the Inspiration of New York’, 31 December 2021

Hong Kong Apostasy Reprint

The title of the following essay by the venerable Hong Kong political analyst Lee Yee 李怡 — ‘The Mission of Our Times’ 時代使命 — compresses two slogans that, in their origin and import, could not be more different.

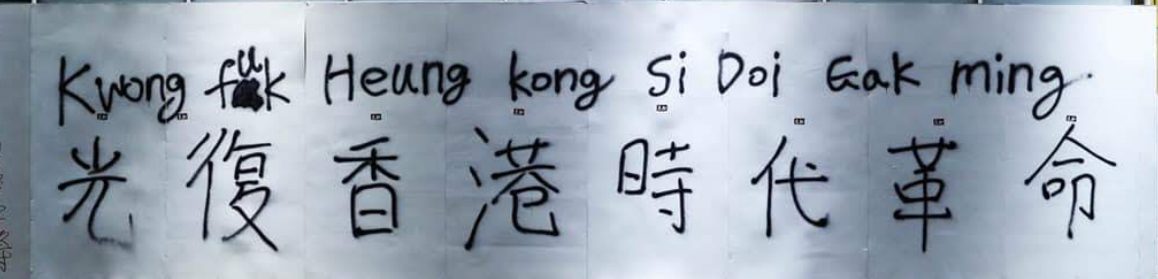

Previously, we introduced Lee’s interpretation of a slogan formulated by the independence activist Edward Leung Tin-kei (梁天琦, 1991-) — ‘Restore Hong Kong, Revolution of Our Times!’ 光復香港, 時代革命! Gwong fuk heung gong, si doi gak ming!. As I noted elsewhere:

‘the obduracy of Hong Kong and Beijing hard-liners turned the slogan of an irrelevant and infinitesimal minority into the rallying cry of a generation.’

Here the author combines Leung’s call to action with the keynote political theme of the Chinese Communist Party under Xi Jinping announced at the Nineteenth Party Congress in October 2017 — ‘Forget Not Our Original Intentions; Hold Fast to Our Mission’ 不忘初心, 牢記使命. This slogan, and its voluminous ex cathedra interpretations, form the ideological core of an ongoing Party re-education campaign launched in June 2019.

***

I first met Lee Yee in October 1974 when I was passing through Hong Kong on my way to study in the People’s Republic. Three years later, he employed me as a translator and editor. Along with my other mentors — Simon Leys, Yang Xianyi, Gladys Yang, Wu Zuguang, Winnie Yeung Lai-gwan, to name but a few — Lee Yee was an important guide in my developing appreciation and understanding of the Chinese world. It was under his aegis too that, over the years, I would follow the unfolding drama of Hong Kong, starting with the fateful March 1979 meeting between Deng Xiaoping and Murray MacLehose, the governor of the British colony. It was that encounter that triggered the five-year-long negotiations over the fate of the territory.

In this essay, Lee touches on some of the valiant attempts by Hong Kong leaders and opinion makers — Sze-yuen Chung, Lydia Dunn, Quo-wei Lee, as well as Sze-Kwang Lao, Hsü Tung-pin and himself — to play a public role during those negotiations by contributing ideas towards a better future for the city. All of those efforts were aimed at preventing, or at least forestalling, the deep-seated and systemic crisis that has been unfolding in China’s Special Administrative Region like a slow-motion train wreck since 1997.

Lee Yee’s perspective is crucially important for those who would understand the decades-long efforts of men and women of conscience to help vouchsafe the most unique, and only truly global, city in the Chinese world. His essays should also be recommended to the swathes of new-born Hong Kong Experts whose pontificating — be it in Chinese, English or other languages — now guides and shapes international opinion. Of course, in an ideal world, Lee Yee’s work would also be read in Mainland China.

***

Readers may be understandably appalled by the fact that Lee Yee quotes approvingly the views of Steve Bannon, the dyspeptic former White House Chief Strategist and a notorious one-time ‘Trump whisperer’. When forging a path through the verbiage of AmeriNazis, the odium of which is not dissimilar to the noxious prose of The People’s Daily, I find it helps to hold one’s nose.

Present US policy towards the People’s Republic and the gimcrack stance of the Administration towards Hong Kong bring to mind the words of the ill-fated Thomas Beckett in T.S. Eliot’s verse-drama Murder in the Cathedral:

Now is my way clear, now is the meaning plain:

Temptation shall not come in this kind again.

The last temptation is the greatest treason:

To do the right deed for the wrong reason.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

28 August 2019

***

Related Material:

- Lee Yee 李怡, ‘Back in the Year — Hong Kong 1984’, China Heritage, 31 July 2019

- Lee Yee 李怡, ‘Restoring Hong Kong, Revolution of Our Times’, China Heritage, 6 August 2019

- He Weifang 賀衛方, ‘Hong Kong — 2019, 2003, 1984, 1979’, China Heritage, 12 August 2019

- Ni Kuang 倪匡, ‘The Nobility of Failure’, China Heritage, 14 August 2019

***

The Mission of Our Times

時代使命

Lee Yee 李怡

Translated and annotated by Geremie R. Barmé

Even my old friend Ni Kuang has said that he never thought Hong Kong people would continue to protest so courageously. First one, then two million took to the streets; throughout there have been young people on the frontlines facing life-threatening danger. He also remarked that, if Hong Kong people had openly opposed the looming domination of the Chinese Communists back in the year, there would be no need for millions to take to the streets now. Back then, he says, 500,000 would have been more than enough to intimidate the British, so much so that they would not have so easily handed Hong Kong over to Beijing. But at the time, the majority of Hong Kong people didn’t comprehend the stark reality lurking behind the façade of the Communists. Ni recently observed that:

‘Only a few writers like you and me opposed the Handover [on 1 July 1997]. But our views simply didn’t resonate in the wider society. Everyone let a precious opportunity slip through their hands.’

[Note: For Ni Kuang’s views as referred to here, and published in an interview conducted by Apple Daily, see Ni Kuang 倪匡, ‘The Nobility of Failure’, China Heritage, 14 August 2019]

倪匡兄說,他想不到現在香港人會如此勇敢抗爭,一兩百萬人上街,年輕人不顧死活地在前線衝。他說,如果當年香港人這樣站出來反對共產黨統治,莫說百萬人,就算50萬人,英國也不敢把主權拱手給中共。那時候的香港人不認識共產黨真面目,「只有我跟你幾個寫作人反對,整個社會沒有強烈回響。失去了大好時機。」

During the negotiations between the Chinese People’s Republic and the British [from late 1979 to 1984] Sze-Kwang Lao [勞思光, 1927-2012, a philosopher and independent thinker who moved to Hong Kong as a result of the ‘White Terror’ imposed on Taiwan by Chiang Kai-shek], Hsü Tung-pin [徐東濱, who was born in Beijing but relocated to Hong Kong and was one of the main writers for the Ming Pao 明報 ‘stable’ of anti-Communist publications], along with me, established the Hong Kong Prospect Institute [香港前景研究社 which, apart from both private and public advocacy, also published the book《香港前景: 香港前景研究社基本資料》in 1982]. Our institute formulated a number of proposals that suggested how the British administration of Hong Kong might continue to function and evolve. However, our ideas failed to gain any wider traction.

At the time, those who were most trepidatious about what could happen after 1997 were absorbed in their preparations to emigrate; while those who had no similar way out simply gave in to fatalism. There was also a minority — including university students — who actually believed that, following the Handover, the ‘People of Hong Kong’ would finally be put in charge. They were beclouded by what was a kind of hazy patriotic sentiment and they shared a visceral belief that it would somehow be ‘immoral’ for Hong Kong to remain under British rule.

As I have previously mentioned, during those years [of the negotiations from 1979 to 1984] Sze-yuen Chung [鍾士元, 1917-2018], a Senior Member of the Hong Kong Executive Council [and a man later dubbed ‘The Godfather of Hong Kong Politics’], shuttled between London and Beijing because of the concerns that he, and others like him, had about the transfer of sovereignty to the People’s Republic. London accorded him scant attention while, up in Beijing, he had a famously unhappy encounter with Deng Xiaoping.

[Note: Following fruitless discussions with the British prime minister Margaret Thatcher in London, Sze-yuen Chung and two other eminent Hong Kong political figures — Lydia Dunn and Quo-wei Lee — travelled to Beijing June 1984 where they were received by Deng Xiaoping. Deng made a point of emphasising that he was only meeting with them as a courtesy. Although he regarded them as prominent Hong Kong individuals, in his eyes they had no authority or indeed any capacity to represent anything apart from their own views. In fact, at the time, in the signature style of Communist Party sniping, Chung was derided as being little more than ‘a bastard courtier without a court’ 孤臣孽子.

In his published account of the fateful Beijing encounter Chung said that Deng told his Hong Kong guests point blank:

‘You know full well that China and the British are engaged in negotiations [over the future of Hong Kong]. We are going to resolve things with the British; we will brook no interference from others. In the past, there was some talk about a “three-legged stool” [that is, representatives of Hong Kong people and interests might also play a role in the negotiations]. There are two legs, not three.’ 中英的談判你們是清楚的,這個問題我們會和英國解決,而且這些問題決不會受到任何干擾,過去所謂三腳凳,沒有三腳,只有兩腳。

When Chung pressed him further, Deng responded:

‘In effect what you are saying is that you don’t think that the people of Hong Kong have confidence [in us]. That’s your opinion; the reality of the matter is that you do not trust the People’s Republic of China!’ 概括來說,你們說香港人沒有信心,其實是你們的意見,是你們對中華人民共和國不信任。

In regard to the future administration of the territory, Deng offered the following:

‘As to who will run Hong Kong I can tell you that we will not cross the line. The future government and administrators of Hong Kong should by and large be Chinese patriots … they will be duty bound to run Hong Kong well. … The Central Government doesn’t want a red cent of your money; things are sure to go well. Any other concerns that they [that is, Hong Kong people] express are unnecessary.’ 將來香港由誰來治理,我們有個界線,將來香港政府及其附屬機構的治理人員,主體上應是愛國者 … 他們的任務是把香港搞好。… 中央不願意在香港取一個銅板,所以做的事一定是好的,他們(香港人)的擔心是多餘的。

It was during this period that Deng first officially articulated the concept of ‘One Country, Two Systems; Hong Kong People Will Govern Hong Kong’ 一 國兩制,港人治港.

— trans. G.R. Barmé]

I interviewed Sze following the conclusion of the Sino-British negotiations and he said in a tone of utter exhaustion: ‘I had no real standing; it’s because I wasn’t appointed democratically’. [See ‘Back in the Year — Hong Kong 1984‘, China Heritage, 31 July 2019]. Again, as we have previously noted:

There are those who have waved the Union Jack during the 2019 Resistance Protests. Seeing that flag brings to mind the press conference [on the 21st of December 1984] that British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher held in Hong Kong after she had signed the ‘Sino-British Joint Declaration’ in Beijing. The reporter Emily Lau [Lau Wai-hing 劉慧卿, 1952-, who was then working for The Far Eastern Economic Review] asked the Iron Lady:

‘Prime Minister, on Wednesday, you signed an agreement with China promising to deliver over five million people into the hands of a Communist dictatorship. Is this morally defensible or is it really true that in international politics the highest form of morality is one’s own national interest?’

Thatcher’s reply was:

‘May I not put it to you that the situation now is vastly better for Hong Kong and accepts and honours and acknowledges the fact that China wishes the lifestyle of Hong Kong to continue under that Agreement?

‘I think you would have had great cause to complain had the Government of Great Britain done nothing until 1997, and I believe that most of the people — indeed, the overwhelming number of people in Hong Kong — think the same. You may be the solitary exception.’

[Note: Previously quoted in Lee Yee’s essay ‘Time to Talk About the Baltic Chain Again’ included in ‘Holding Hands in Hong Kong’, China Heritage, 26 August 2019]

Of course, that was not the case at all for, in reality, the vast majority of Hong Kong people were not satisfied with the outcome of the negotiations. Regardless of that, no strong voices were raised in protest.

在中英談判期間,勞思光、徐東濱及包括我在內的幾個知識人組織「香港前景研究社」,就延續英國管治設想了不少方案,但在社會得不到回應。擔心97後景況的人紛紛移民,無法移民的就接受宿命;也有包括當時的大學生在內的少數人,相信會有真正的港人民主治港。一種朦朧的民族意識,覺得要英國延續殖民統治似乎「不道德」。行政局議員鍾士元率團奔走倫敦、北京,表達香港人對主權轉移的憂慮,在倫敦不太受重視,到北京見鄧小平則不歡而散。在中英談判大局已定的時候,他接受我訪問,疲倦地說:「你叫我跟中英對抗,這是不可能的,我沒有後盾,沒有選民。」1984年戴卓爾夫人在香港舉行記者會,時任記者的劉慧卿問她:「你們將500多萬香港人交給獨裁的共產政權,在道義上是否說得通?」她回答說,我們甚麼都做了,「所有香港人都滿意,你是唯一的例外。」當然不是,實際上是絕大部份香港人不滿意,但確實沒有太強的抗議聲音。

One can appreciate the reasons for that lack of response for back then, even if people were mindful of their past negative experiences [with the People’s Republic], in Hong Kong itself they had no particular sense of repression or coercion. The ambience was vastly different from the kind of general apprehension that people in Hong Kong are experiencing today. Yet here we haven’t been through a ‘democratic christening’ [whereby the electorate acquires a sense of their rights and responsibilities as citizens]; the freedoms and legal system we have enjoyed for so long were not hard won through struggle, rather they were introduced holus-bolus by the British. Just as we don’t usually pay any attention to the precious quality of the air we breathe, so too Hong Kong people have previously not been particularly mindful of the boon of freedom and the legal system. You don’t really start fighting for your life until you are actually struggling for every breath. Without that sense of threat you wouldn’t ever get people to take part in a demonstration. In retrospect it wasn’t true that people simply didn’t take advantage of the opportunities to protest when they should have; they simply didn’t think about the existence of such freedoms, or in fact that they were even necessary. — Put simply, among Hong Kong people there was neither the atmosphere nor the conditions required for mass mobilisation.

原因是當年香港人縱使有些人有舊日經驗,但現實生活中並沒有受壓迫欺凌的感覺,跟現在香港人的切身感受不一樣。香港人沒有經過民主洗禮,自由法治是英國統治帶來的,毋須香港人去爭取,就像呼吸空氣一樣自然而不覺珍貴;沒有壓迫感窒息感,也就沒有抵死抗爭的意識,連遊行示威也發動不起來。現在回過頭去看,不是錯失機會,而是沒有機會——不存在可以發動民眾的氣候和條件。

Should we claim then that it is now simply too late for the People of Hong Kong to rise up and resist? Of course, it is true that Hong Kong is already completely in the thrall of an autocratic government. In terms of power disparities alone, obviously resistance is futile; it’s somewhat akin to throwing eggs against a rock. The odds of winning are zero. But this David vs. Goliath-like stand off between protesters and the government has in itself an aura of righteous majesty and it is something that has taken the world by surprise. Just the other day, the former White House Chief Strategist Steve Bannon said in an interview that:

‘Time and again with resolution and resilience, they have tirelessly gone out to protest. They are the heroes of the day and should be nominated for a Nobel Prize. These men and women have demonstrated to the world what freedom is all about. They do not give in despite facing down totalitarianism, theirs is a spirit of daring; they are not only an example for the young people of the whole world, they are an inspiration for us all. This is momentous; history is being made here and now. The protests in Hong Kong will be recorded in the annals of history.’

[Note: This quotation has been back-translated from Chinese. For Bannon’s (opportunistic) views on Hong Kong, see Zooming In with Simone Gao, ‘Steve Bannon: If There Is Another Tiananmen in Hong Kong, the CCP Will Collapse’, Youtube, 22 August 2019]

Bannon also claimed that if the Communists are so inflamed by developments in Hong Kong that they repeat the June Fourth Massacre, it will surely lead to their own collapse.

現在香港人的奮起抗爭是不是已經時不我與了呢?不錯,香港已成專制政權的囊中物,就力量對比來說,香港的抗爭確實是以卵擊石,沒有勝算。但這種以弱抗強的鬥爭,也賦予了香港抗爭運動令全世界驚訝佩服的正義光環。早兩天,白宮前首席戰略顧問班農接受訪問時說,香港年輕人「一次又一次堅韌不拔、志在必得、毫不鬆懈、絕不退縮地上街抗爭,他們是當代英雄,應提名諾貝爾和平獎。他們向世人展現自由的男女,面對極權毫不示弱、挺身而出的精神,他們不僅是全世界年輕人的榜樣,而且是所有人的榜樣,我覺得非常偉大,歷史就在我們面前,香港遊行必將載入史冊。」並說,如果中共惱羞成怒,像六四那樣鎮壓,那麼中共的死期也到了。

In the past, the People of Hong Kong did indeed squander chances they might have had to avoid falling into the clutches of the totalitarian state. The irony, however, is that now history has bestowed on the People of Hong Kong an unprecedented second chance. They now still have the right to use the fragile freedoms they still possess to oppose the overwhelming might of an authoritarian state. These may be but feeble gestures, but they represent the spirit of all of those in China, and throughout the world, who aspire to freedom.

Right at this moment, the People of Hong Kong are on the front line of the universal human quest for freedom and opposition to subjugation. But, just as the old saying holds: it’s like ‘a mantis trying to stop the careening wheels of a chariot’. You may well wonder whether the People of Hong Kong, who merely number a few million souls, are too paltry a force to be able to shoulder such a grand responsibility. Of course they are. However, for better or worse, if you are living in Hong Kong right here and right now, you have no choice but to resist. To do otherwise is to give in to servitude.

This, then, is Hong Kong’s ‘Mission of Our Times’.

歷史上香港人錯失了一個免於落入極權手中的機會,正因如此,歷史也給了香港人一個人類史上前所未有的機會,就是以微弱的自由力量,去抗拒一個超強的專制力量。而微弱的自由力量的背後,是全人類包括中國人在內的追求自由的心靈。香港人現在就站在人類歷史上自由對抗奴役的最前線,螳臂擋車。也許你會說,勢單力薄的香港幾百萬人,擔負得起這樣的重任嗎?當然擔負不起,但是,幸也罷,不幸也罷,生在這時代的香港,不想做奴隸除了抗爭就沒有選擇,這就是香港人的時代使命。

***

Original Source:

- 李怡, ‘時代使命’, 《蘋果日報》, 2019年8月26日

***