The Other China

在路上

‘Hope is like a path in the countryside. To start out with there is nothing there but, as people walk this way again and again, a path appears.’

希望是本無所謂有,無所謂無的,這正如地上的路,其實地上本沒有路,走的人多了,也便成了路。

***

When he was seeing off Xi Jinping following their summit at the Filoli Estate outside San Francisco on 15 November 2023, US President Joe Biden expressed admiration for the Chinese ruler’s Red Flag limousine. The latest model in a series of state vehicles that dates back to the 1950s, and which was originally inspired by the 1955 Chrysler Imperial, in its heft and armor Xi’s heavy duty car emulates Biden’s own ride, nicknamed The Beast from the Bush era. In keeping with the peasant-imperial kitsch taste of China’s post-Mao rulers, however, the interiors of the doors of Xi’s vehicle are decorated with embedded polished stone landscapes that were fashionable among Qing-era officials.

The presidential encounter brought to mind a comical rhyme from an earlier phase in the China-US relationship. Dating from the early 1960s, friends of mine in the 1980s still got a laugh out of its pointed message:

See the sedan, beep-beep-beep,

Chairman Mao has taken his seat,

And in his Red Flag drives away.

US imperialist JFK,

Furious does an anxious reel,

Turns and slips on watermelon peel.

Falls on face, mud in mouth goes,

And right there in Dallas turns up his toes.

小汽車,滴滴滴,

上面坐著毛主席。

毛主席,坐紅旗,

氣死美帝肯尼迪。

肯尼迪,乾著急,

踩著一塊西瓜皮。

一摔摔個嘴啃泥,

嗝兒屁著涼達拉稀。

— translated by Linda Jaivin for Geremie R. Barmé, ‘Engines of Revolution’ in Autopia: Cars and Culture, London: Reaktion Books, 2002, p.182

***

‘Engines of revolution’ were a significant feature in China’s twentieth century. Although the U-127 was literally the ‘locomotive of history’ that V.I. Lenin used, both in life as well as in death, and even if the Chinese Communists inherited the metaphor — and even named one train engine ‘Mao Zedong’ — jeeps, sedans and limousines have been their preferred means of transportation.

Similarly, roads, paths, and directions have been central to Chinese political discussion for well over a century. In Xu Zhiyong asks ‘Whither China?’, part of the series Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium, we noted:

‘Where to from here?’ 向何處去, ‘Exploring every avenue’ 上下求索, ‘What’s to be done? 怎麼辦, ‘What is to be avoided and what is to be followed?’ 何去何從, ‘Who holds fate in their hands?’ 誰主沉浮 — these ancient questions are asked with ever greater urgency in China today.

The Chinese Communists, who adapted Stalinism in their pursuit of revolution and modernity, have long been obsessed developing a dogmatically capacious ‘political line’ 路線. Mao and his acolytes warned of driving the wrong way 逆行, going into reverse 開倒車 and travelling backwards 走回頭路. The socialist future dominated and directed by the one-party state promised a ‘golden highway’ 金光大道, anything else was heresy 歪門邪道.

The revolution, a process that readily inspired modernist metaphors of engines, skyscrapers and factories, also meant that the motor vehicle could convey powerful messages to the proletariat about the significance of their contribution to the state.

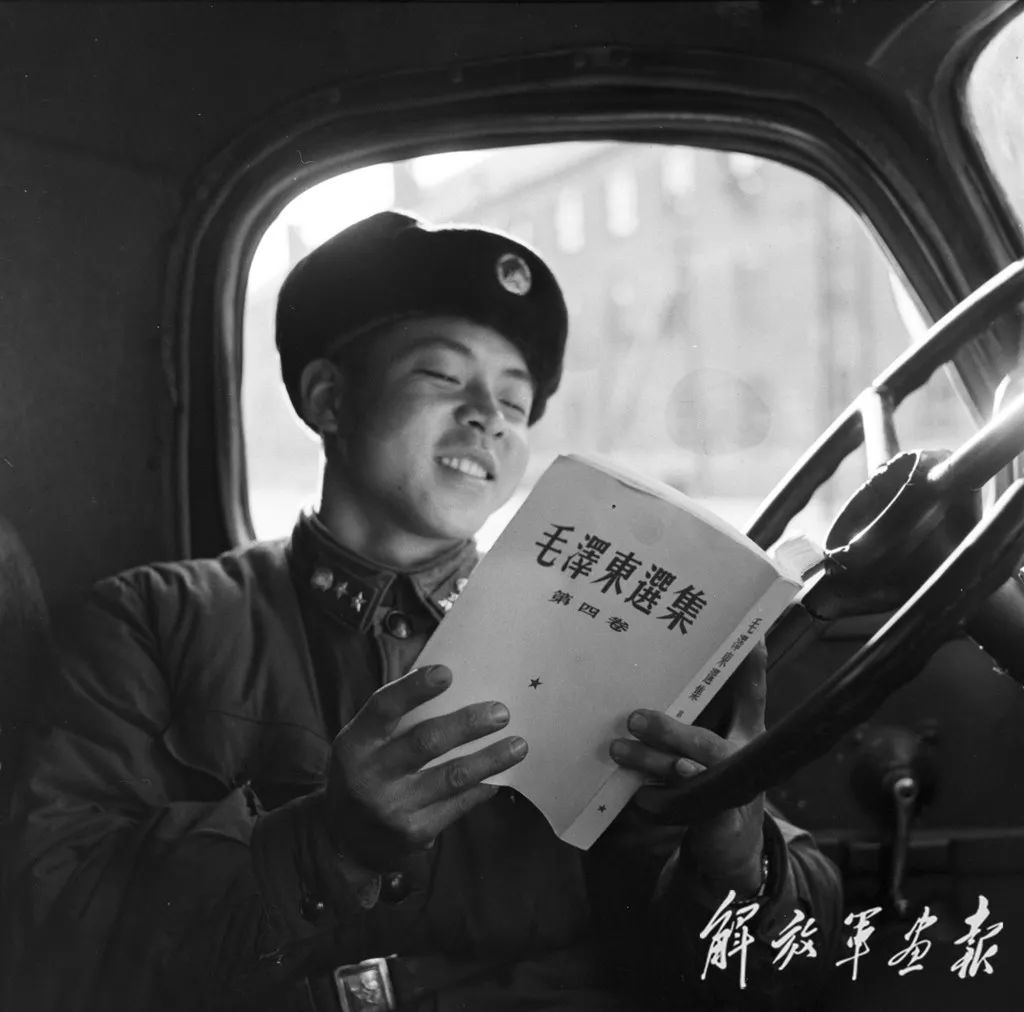

The renowned champion of do-gooder socialist docility in China is Lei Feng (雷鋒, 1940-1962), an army martyr used as a model of communist morality since his apotheosis in 1964, and a figure still regularly touted by the country’s social engineers. For nearly four decades the nation has been exhorted to emulate Lei Feng’s example of unwavering loyalty to the party, as well as to study his numerous bons mots, one of the most noteworthy being: ‘Just as a motor vehicle does whatever the driver wants, so people obey the directions of the party.’ This quotation was illustrated with an image of Lei Feng in the cabin of his army truck studying a copy of The Selected Works of Chairman Mao propped up against the steering-wheel.

‘For me’, Lei Feng wrote in his diary,

‘Chairman Mao’s writings are like food, or a weapon. They are like the steering wheel of a vehicle. You need food to survive, weapons in war and a steering wheel to drive. Chairman Mao’s writings are essential for carrying out the revolution.’

毛主席著作對我來說好比糧食和武器,好比汽車上的方向盤。人不吃飯不行,打仗沒有武器不行,開車沒有方向盤不行,乾革命不學習毛主席著作不行!

***

***

(Lei Feng was ‘martyred’ while attempting, unsuccessfully as it turned out, to direct a reversing truck: the vehicle hit an electricity pole that felled the ‘good student of Mao Zedong Thought.’ The irony surrounding his demise and his legendary devotion to the automobile has made him the butt of jokes ever since.)

Early in his tenure, Xi Jinping warned against talking ‘old roads and byways’ 老路、邪路. He would lead the country along the ‘correct path’ 正道 and his propagandists tirelessly praise him for ‘pointing out the way’ 指明方向 in every area of national policy. He is also celebrated for the guidance he offers the world.

Xi Jinping’s detractors, however, have dubbed him the ‘Great Accelerator’ 總加速師, a man whose wrong-headed policies appear to be hastening the decline and eventual collapse of the party-state itself. (For a digest of Xi Jinping’s unofficial titles, see Xi the Exterminator & the Perfection of Covid Wisdom, 1 September 2022.)

***

In 2021, China Heritage marked the Double Tenth Festival — 1o October National Day of the Republic of China on Taiwan, by publishing a translation of ‘As if to Break Free of the Autocratic Gloom’ 走出專制統治黑暗, a speech delivered by the journalist-historian Dai Qing 戴晴 in March 2011.

Dai commemorated the centennial of a revolution that promised an end to China’s millennia-old autocracy. For most of the twentieth century, however, new forms of despotism had dominated the country’s political landscape, be it on the Mainland or on Taiwan. From the late 1980s, the clash between two ideologically disparate forms of Chinese authoritarianism transmogrified into a contest between the one-party Communist state of the People’s Republic and the market-oriented constitutional democracy of the Republic of China.

The civil war that broke out in 1927 following a short period of Nationalist-Communist collaboration continues to this day. On Taiwan, although the promise of the Xinhai Revolution was only realised some eighty years after 1911, it is now under constant external threat. On the Mainland, a reinvigorated monocracy that is heir to a dark past holds sway. The People’s Republic claims that it is the legitimate successor regime both to dynastic China and the ‘bourgeois revolution’ of 1911. As a successful modern autocracy it affirms the orthodox lineage of rulership — 正統 zhèngtǒng and 道統 dàotǒng — while betraying the original promise of fundamentally revolutionary political change with which the country’s revolutionary century began.

On the opposite shore of the Taiwan Straits, the Republic of China has inherited the mantle of the Xinhai Revolution to become a constitutional democracy of a kind that was envisaged by the foes of the Qing and millennia of autocratic rule.

In 2024, Taiwan poses an existential threat to Beijing. To validate the historical mandate of one-party rule under the Communists, Taiwan must be subjugated. Meanwhile, as we have previously noted, on the mainland,

The threnody of the Xi Jinping decade is tedium, something born of the ceaseless oscillations within China’s hermetically sealed system and it signals its deadening presence through reversals and the glum repetition of various tropes of the past.

Beijing’s obsession with political high drama — 大是大非 — makes it difficult for Taiwan to practice politics of the everyday, even when the quotidian is what really matters for most people.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

12 January 2024

Eve of the General &

Presidenical Election on

Taiwan/ ROC

***

Post-Election Update

I know that I am an autocrat, but I will be the last one. I will use my power as an autocrat to bring an end to autocracy. We must travel the road of democracy and the rule of law.

我知道我是專制者,但我會是最後一位 —— 我以專制來結束專制。

民士法治之路,是我們一定要走的路。

— Chiang Ching-kuo 蔣經國

President of the Republic of China, 1978-1988

The Significance of Our Win

1. Taiwan has told the world that we stand on the side of democracy, not autocracy. We will continue to travel in the company of our global democratic allies;

2. Through their actions the people of Taiwan have successfully resisted outside interference in our politics. We have confidence in our ability to elect our own president; and,

3. Of the three contending parties, the Lai-Hsiao ticket has garnered the most popular support. It is proof that our nation will continue on the correct path; we will not be diverted nor will we turn back.第一個意義,台灣告訴全世界,在民主和威權之間,我們選擇站在民主這一邊。中華民國台灣,會繼續和國際民主盟友並肩同行。

第二個意義,台灣人民用行動,成功抵禦外部勢力的介入。因為我們相信,自己的總統自己選。

第三個意義,在三組候選人中,賴蕭配得到最多的支持,代表國家會繼續走在正確的路上,不會轉向,更不會走回頭路。

— from Lai Ching-te’s victory speech

賴清德勝選感言

Lai Ching-te is on a political path of no return.

賴清德踏上政治這條不歸路。

— various PRC commentators, August 2023

13 January 2023

Thirty-sixth Anniversary of

Chiang Ching-kuo’s death

蔣經國祭日

***

***

Further Reading:

- Gerrit van der Wees, Taiwan: The facts of history versus Beijing’s myths, Council on Geostrategy, 8 January 2024

- Brian Hioe, Taiwan’s Election Under China’s Shadow, Dissent Magazine, 10 January 2024

- We ‘can never win’ a war: Taiwan’s former president Ma on the best way to deal with China, DW News on YouTube, 10 January 2024

- David Sacks, Why China Would Struggle to Invade Taiwan, Council on Foreign Relations, 10 January 2024

- Alice Su & David Rennie, Taiwan goes to the polls, Drum Tower, 10 January 2024

- Taiwan’s very special 2024 presidential election, DW News on YouTube, 12 January 2024

- LeLe Farley, Dear 柯粉… 【原視頻被舉報】,油管,2024年1月12日

- 吳國光,國事光析:台灣大選之際談談民主與獨立,VOA,2024年1月12日

- Nathan Batto, The election results and what’s next, Frozen Garlic, 14 January 2024

Also in China Heritage:

- Introducing Translatio Imperii Sinici — China Heritage Annual 2019, 14 January 2019

- Prelude to a Restoration: Xi Jinping, Deng Xiaoping, Chen Yun & the Spectre of Mao Zedong, 20 September 2021

- Celebrating Dai Qing at Eighty, China Heritage, 1 October 2021

- October 1 & October 10 — Two Chinas, Whose Fatherland?, 1 October 2022

- 1978-1979, Year One of the Xi Jinping Crisis with the West, 20 December 2022

- Jun Zhang, Driving toward Modernity: Cars and the Lives of the Middle Class in Contemporary China, Cornell University Press, 2023

On the Road — Taipei 2024

Good drivers keep their hands on the wheel & eyes on the road. These several years, we’ve driven through challenges, reforms, & the pandemic. We’ve made it this far down the road of democracy, no matter how winding & rough, thanks to the support of the #Taiwanese people.

Now, it’s time I hand the keys to @ChingteLai & @bikhim for the next part of the journey. I have no doubt they are capable & dependable drivers, & that they will make sure we stay on the right path.

— Tsai Ing-wen, 6 January 2024

President Tsai and her two successors drive around the island of Taiwan, passing seven well-known scenic spots as they go. At one point in the video, Tsai looks into the rear-view mirror and sees a blue lorry and a white sedan speeding by in the opposite direction (at minute 2.20). They represent the retrogressive politics of the KMT Nationalist Party, the symbol of which is blue and the problematic program of the ‘white’ Taiwan Progressive Party.

‘On the Road’ offers a vision of normalcy. The style of the video is unpretentious, its language mild — both are in marked contrast to the stentorian thundering and visual hyperbole favoured by the Chinese Communists. Sense and sensibility on Taiwan long ago parted company — 分道揚鑣 — with the Mainland. Beijing believes a ‘Chinese Taiwan’ will circle back into its orbit. With each passing year, however, Taiwan continues to resist the pull free of the deadening cycle of Chinese history.

For a discussion of this campaign video, see: 蔡英文載賴清德“在路上” 影片 景點曝光暗藏真相, 筱君 台灣 PLUS, 油管,2024年1月3日. See also:

- 台灣競選視頻《在路上》引吸千萬點閱 新華社《永遠在路上》成反差,《亞洲自由電台》,2023年1月8日; and,

- 五岳散人,台灣《在路上》與新華社《永遠在路上》:土鱉法西斯審美的反擊,油管,2023年1月9日

Burying the Republic of China,

on the Mainland

‘On 15 February 1912, three days after the Manchu ruler abdicated, President Sun Yat-sen took part in a ceremony of sacrifice, obeisance and prayer at the tomb of Hongwu [founding emperor of the Ming dynasty, r.1368-1398]…. On 3 April 1912, The Times published a translation of the prayer’. It concluded with the following:

‘The spiritual influences of your grave at Nanking have come once more into their own. The dragon crouches in majesty as of old, and the tiger surveys his domain and his ancient capital. Everywhere a beautiful repose doth reign. Your legions line the approaches to the sepulcher; a noble host stands expectant. Your people have come here today to inform Your Majesty of the final victory. May this lofty shrine wherein you rest again fresh luster from today’s event and may your example inspire your descendants in the times which are to come. Spirit! Accept this offering!’ 鬱鬱金陵,龍盤虎踞,宅是舊都,海宇無叱。有旆肅肅,有旅振振,我民來斯,言告厥成。喬木高城,後先有輝,長仰先型, 以式來昆。伏維尚饗。

— quoted in Light Returns 光復, China Heritage Annual 2017: Nanking

In 2011, the Communist Party authorities of Nanjing marked the centenary of the end of dynastic China by erecting ten tomb stone-like obelisks. Of these, six marked the historically recognised dynasties that had ruled from the area and one celebrated the capital of the insurgent Taiping Rebellion of the mid-nineteenth century. The last stele in the series (pictured below) was erected to mark the twenty-seven years of the Republic of China, the capital city of which had, more often than not, been in Nanjing. (For details, see 十朝歷史文化園.)

***

***

On 29 March 2023, the Taiwan election year, Ma Ying-jeou, former KMT President (2008-2016) and the first former or current Taiwanese president to visit the People’s Republic, paid his respects at the tomb of Sun Yat-sen, founder of the Republic of China. The tomb is situated next to the Xiaoling mausoleum of Zhu Yuanzhang, founder of the Ming dynasty, and the site of the corridor of stele discussed in the above. Ma declared, ‘People on both sides of the Taiwan Strait are Chinese people, and are both descendants of the Yan and Yellow Emperors.’

In an interview with Deutsche Welle on the eve of the January 2024 election in Taiwan, Ma controversially remarked that Taiwan simply had to ‘trust Xi Jinping’. One critic said that the former president was suffering from ‘political infantilism’ 政治幼稚病 and there was no doubt that Ma’s simple-minded defeatism was revealing and reflected a blinkered ethnic nationalism. Yet, he knew better than most that, over the course of nearly a century, trusting the Communist Party had rarely worked to the advantage of the KMT. Regardless, Ma’s last-minute intervention probably damaged rather than enhanced his cause.

***

Always on the Road — Beijing 2024

走好新的赶考之路的必由之路

As we have previously noted, 1988-1990 was a significant turning point in the shared tradition of China’s modern autocracies. On Taiwan, politics began a transition towards the kind of open democracy proffered by the Republican revolution in the 1910s. On the Mainland, a massacre of peaceful protesters in Beijing and the suppression of dissent throughout China, were a reaffirmation of one-party dictatorship. The resulting years of Counter-Reform from 1989 to 1992 would be a source of inspiration to what we have long referred to as Xi Jinping’s Restoration.

In 1990, the Propaganda Department of the Communist Party released a TV series aimed at reaffirming the virtues of Party rule. Written by well-connected members of the Party elite, it was produced under the guidance of Deng Liqun, a formidable Maoist ideologue.

The series, discussed below, revived two tropes from pre-1949 Party history. One was the ‘Cave Dialogue’ of 1944 in which Mao Zedong addressed the question of how the Communists could avoid the fate of dynastic Chinese autocracies. The second dated from 1948, when Mao had used a metaphor about ‘being on the road to take the imperial exams’ when discussing taking power in Beijing.

[Note: For more on this topic, see Introducing Translatio Imperii Sinici — China Heritage Annual 2019, 14 January 2019.]

Both of these historical vignettes feature prominently in the Xi Jinping era. The first lies at the core of ‘full-process democracy’, the second is the inspiration for Xi’s claim that through a tireless battle against corruption, the Party can renew itself and forever be on the road to perfection. Together, these are known as the ‘Two Answers’ 兩個答案, or the way to ‘escape the cycle of history’ 跳出歷史的週期律。In keeping with the metaphor of imperial exams, Xi Jinping offers the following neat formula:

The era confronts us with exam questions. We are the ones who must answer those questions and The People are our examiners. 時代是出卷人,我們是答卷人,人民是閱卷人。

Two days after Tsai Ing-wen and the DPP released the campaign video ‘On the Road’, Xi Jinping addressed members of the body in charge of his signature anti-corruption campaign. China Daily reported that in his remarks:

Xi emphasized that as the world’s largest Marxist ruling party, how can our party successfully break free from the historical cycle of rise and fall and ensure that the Party will never change its nature, convictions or its character? … “Let the people supervise the government,” was the first answer Comrade Mao Zedong proposed to this question. On that basis, we have provided the second answer — constantly advancing the Party’s self-reform.

Elsewhere, state media declared that:

… under the core party leadership of Xi Jinping, the party has the courage and wherewithal to govern itself to the highest standards. This marks a new phase in the century long effort by the Party to revolutionise itself and, by means of self renewal, to successfully break free of the cycle of history [that for millennia condemned China’s rulers to futility and repeating the errors of the past].

The Communist Party’s declaration that they were ‘on an eternal road’ 永遠在路上 of self-renewing dominance clashed with the progressive democratic message of Tsai Ing-wen and her DPP colleagues on Taiwan.

***

On the Communist Party’s Road

In the party’s venture into the commercial world, I noted in 1992, television remained the key outlet for up-market propaganda. Although serious book series and journals were aimed more at middle-school and university students and other social elites, it was the nightly bombardment of the general public with television images that was a major focus for the propagandists.

The popular 1988 television documentary River Elegy 河殤, was followed in August 1990 by an official made-for-tv riposte, On the Road: A Century of Marxism 世紀行. This four-part series was first screened amid considerable fanfare on Central Television and was followed by the publication of the bombastic narration in the pages of the Guangming Daily, one of the nation’s leading newspapers.

On the Road was produced by the party’s own Department of Propaganda, advised by Deng Liqun, who was one of the most active Maoists in the land and a man trained in the art of the cultural purge back in Yan’an in the early 1940s and who remained active throughout the 1990s as the party’s leading critic of incipient liberalization.

Each of the four half-hour episodes in the series extolled one of the party’s Four Basic Principles (that is, adhere doggedly to socialism, to the People’s dictatorship, to the party leadership, and to Marxism-Leninism and Mao Zedong Thought). The tone of the show was set by the theme song that began each episode. The opening credits would roll as the popular pop-rock singer Liu Huan 劉歡 boomed out:

- You are a seed of fire, igniting this slumbering land 你是一個火種,點燃這片沈睡的土地 (the screen shows an image of Karl Marx)

- You are a prophecy, describing the path for all human ideals 你是一個預言,划出人類理想的軌跡 (cut to a picture of Lenin)

- You are a banner, fluttering in the wind ready to face all on-coming storms 你是一面旗幟,飄飄揚揚迎著風風雨雨 (images of Mao)

- You spoke a truth, you are a banner, having fallen and risen, you emerged victorious 你訴說一個真諦,你是一面旗幟,幾度沈浮,你又幾度崛起 (Deng Xiaoping shown bobbing up and down in the water as he does the breast stroke)

In addition to these four patron saints of Deng’s China, On the Road heaped praise on other leaders like the aged Chen Yun, a supporter of the planned economy, and Wang Zhen, an incoherent and incontinent ex-army leader extolled for opening up the barren northeast wilds for agriculture, a feat he accomplished with an army of forced labor. And on the subject of the party’s track record, the narrative—most of it written by formerly “liberal” intellectuals like Qin Xiaoying—waxed eloquent.

The series also depicted the four decades of Communist rule as almost an unmitigated triumph. “Our party,” the narrator intoned, “can cope with success, but even more important, it is a party that can weather defeat.” The disasters of the late 1950s and the Cultural Revolution were thus blithely passed over. The narrators reserved a special dig at the West when discussing the future fate of socialist China. As footage of the collapse of Communism in Eastern Europe in late 1989 appeared on the screen, the commentary deftly summed up the mood of bravado that characterized so much post-1989 propaganda by the new generation:

As the 20th Century draws to a close, socialism is faced with a serious test. Western politicians see a bloodless victory coming in 1999, and have gone so far as to predict that socialism will be “routed.” But aren’t they being a little premature … ? After all, socialism has always marched resolutely forward amidst all of their curses!

In 1991, a number of other series in a similar mold appeared, including the State Education Commission-sponsored Song for the Holy Land, a multi-episode paean for reform screened in November. … Not all the TV documentaries of this period, however, were so relentlessly pro-government.

The eight-hour documentary Tiananmen was a far more complex and critical series about contemporary China. Made over a three-year period for Central Television by the young TV directors Shi Jian and Chen Jue, members of one of the first semi-independent media workshops in Beijing, it presented enough of a layered and ambiguous view of China from the late 1980s that it was not broadcast on the mainland. And a surreptitious screening at the International Film Festival in Hong Kong in early 1992 led to punitive bans being placed on the feral directors for some time. One quotation from the narration for the last episode, “Remembering Things Past” 往事 gives the flavor of this extraordinary production. After a series of interviews about the Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution intercut with footage taken at Tiananmen Square, the narrator concludes the series with the following words:

Life has chosen us to shoulder the burden of the present. We continue our travels, regardless of what life has given or withheld.

What forgetfulness has resigned us to, memory forces us to accept. Now at this moment as you face life square on, as you continue your struggle, what is it that keeps you going? As life goes on, as the months and days pass. As time itself passes, utterly impartial …

Perhaps you will hear the events of a distant past; they may recount some tale of hope, long borne, and now clearly calling out to be heeded. For life needs to be heard; the months and days need to be heard. Time itself needs to be heard, in all its detail …

Today goes on, every moment so very real.

Our present travails will also be recalled, and reflected upon

Today, too, is life, a witness …

— from ‘The Greying of Chinese Culture’ (1992), revised as a chapter in In the Red, New York: 1999, pp.119-122

[Note: See also Barmé, ‘From ‘River’ to ‘Road’’, Far Eastern Economic Review, 25 October 1990, p.32.]

***

Tsai Ing-wen on the Road of Democracy

走民主路

***