In the Xu Zhangrun Archive

In the introduction to From Heaps of Ashes 劫灰 Xu Zhangrun 許章潤 quotes from ‘Our Only Umbrella’, an essay by Pierre Ryckmans that was originally presented as an address to celebrate the 2002 New South Wales Premier’s Literary Awards in Sydney, Australia.

China Heritage frequently draws on the insights and wisdom of Pierre Ryckmans and over the years we have commemorated his memory in various ways (see, for example, ‘In Memoriam’, An Educated Man is Not a Pot, ‘One Decent Man’, ‘The Curse of Great Leaders’ and ‘The Whimsy and Wisdom of Lao Shu’.) Below we offer a short excerpt from the introduction to Professor Xu’s new book (forthcoming from Bouden House 博登书屋 in New York), as well as an edited version of Pierre’s 2002 remarks and a reminiscence that Murray Bail published shortly after Pierre’s death in August 2014.

Using his nom de plume Simon Leys, Pierre included the full text of ‘Our Only Umbrella’ (in French ‘Notre seul parapluie — Du rôle de l’art dan les expéditions polarizes en particulier, et dans la vie en général’) in the collection Le bonheur des petits poissons — Lettres des Antipodes (Paris: JC Lattès, 2008). In his introduction to From Heaps of Ashes, Xu Zhangrun quotes Yang Nianxi’s Chinese translation of ‘Our Only Umbrella’ that was published in Shanghai in 2014 (see 李克曼著、楊年熙譯, 《小魚的幸福》 ,上海文藝出版社). The title of that collection — ‘the happy fish’ — is an excuse for us to reprint an excerpt from The View from the Bridge: Aspects of Culture, a series of lectures that Pierre presented in 1996. The leitmotif of that series was a famous parable about ‘happy fish’ 魚之樂 in Zhuang Zi 莊子. In 2011, Pierre granted us permission to reprint all of those lectures in China Heritage Quarterly (see the links provided below).

***

The full title of Xu Zhangrun’s new book is From Heaps of Ashes — reading Erich Maria Remarque and Joseph Brodsky, rejecting the barbarism of our times《雷馬克與布羅茨基——一個基於「劫灰意識」的「反人牲主義」》. See also Xu Zhangrun’s poem ‘A World Reduced to Ashes’ 劫灰, Yibao China, 27 July 2022.

For more on ‘heaps of ashes’, see ‘From a Heap of Ashes — Nancy Berliner & the Art of the Broken’, China Heritage, 28 March 2018 and ‘Nanking Broken’, China Heritage, 13 December 2017.

***

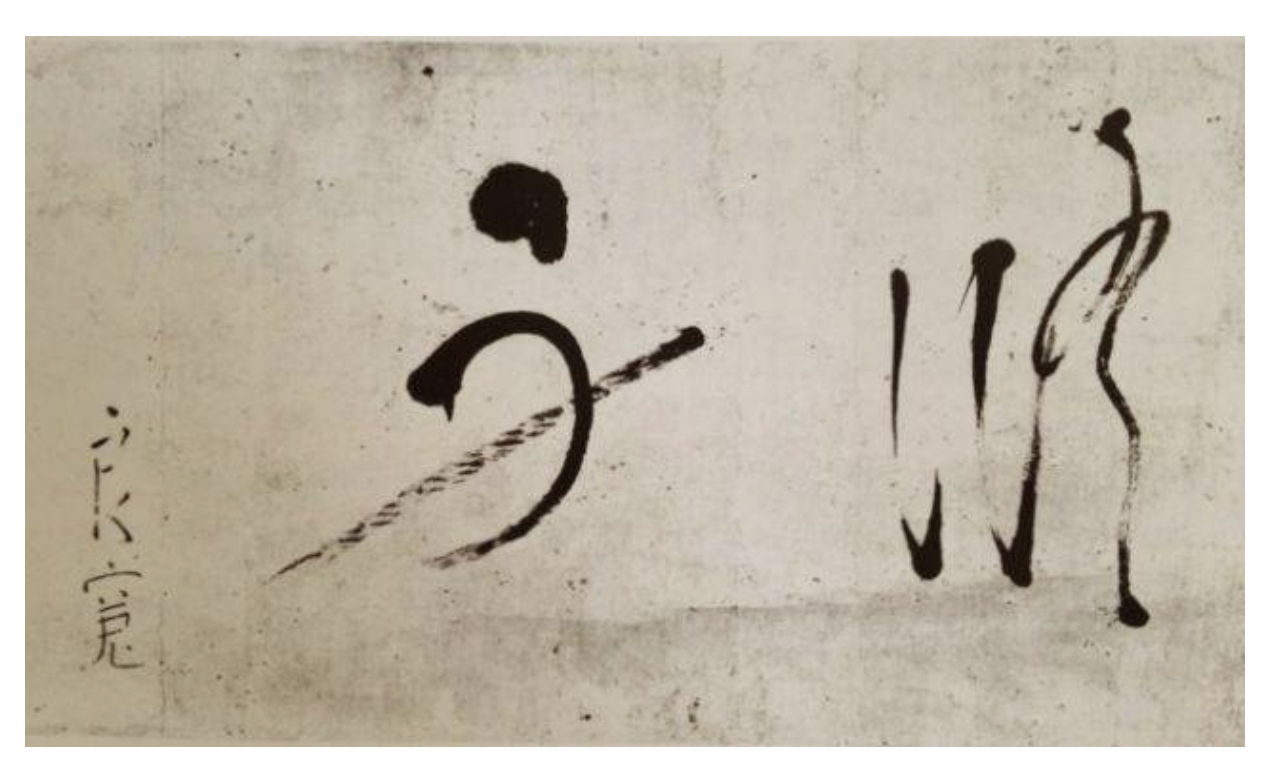

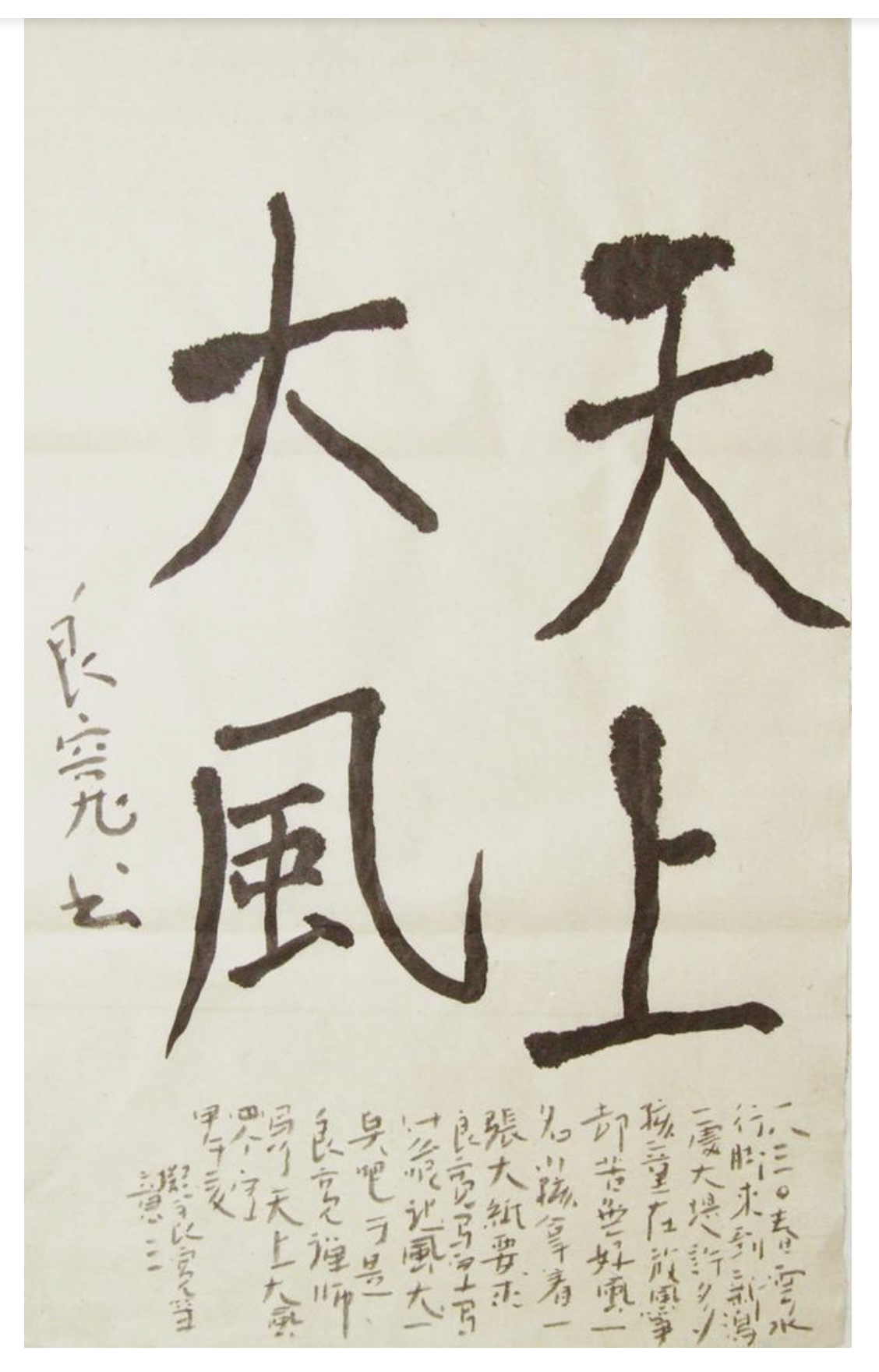

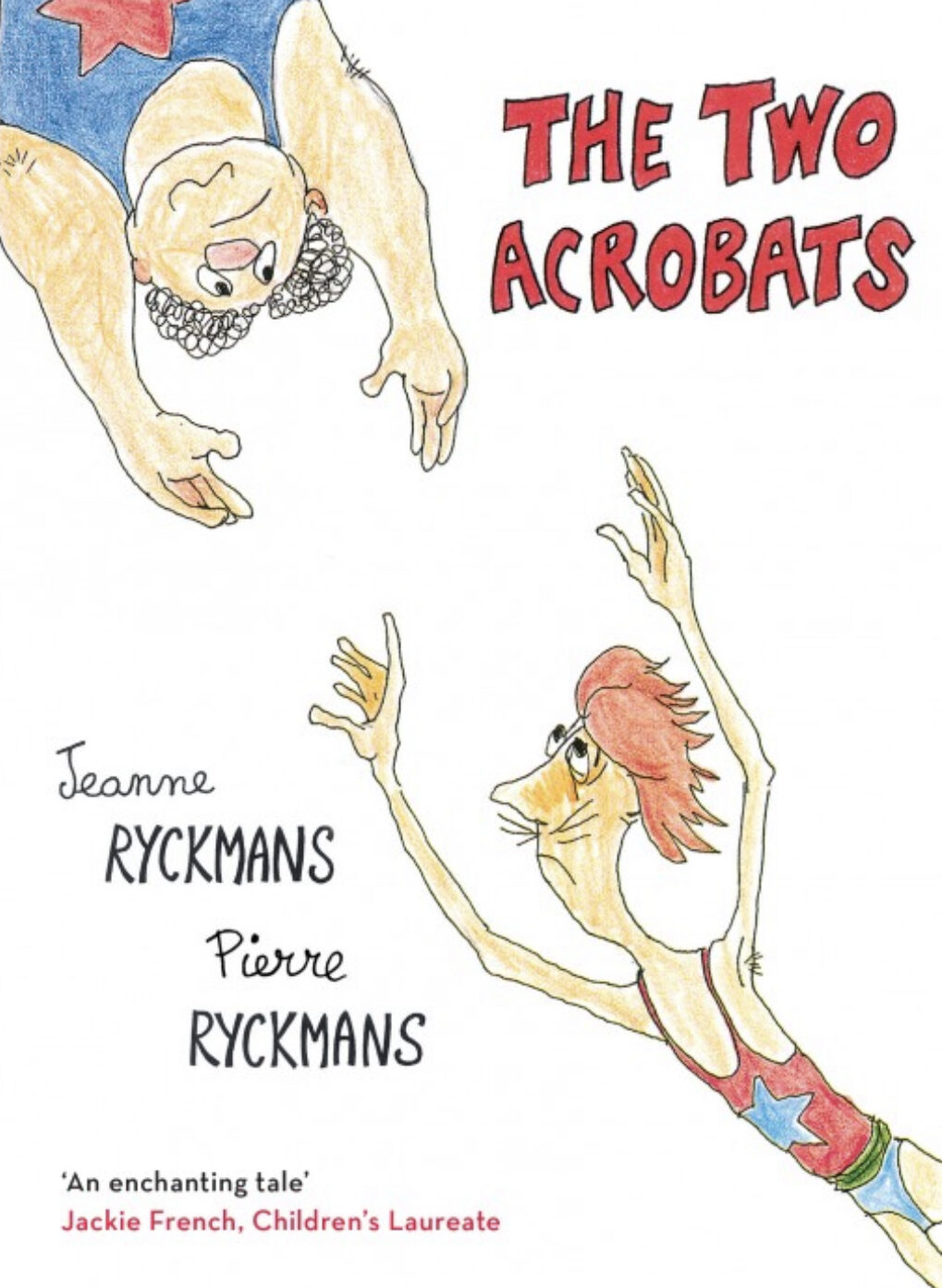

Here we feature four works of art: two pieces of calligraphy by the Japanese monk artist Ryōkan 良寬, a painting by Guo Jian 郭健, an Australian-based Chinese artist, and the cover illustration that Pierre made for The Two Acrobats (Melbourne: Black Ink, 2015), the result of a collaboration with Jeanne Ryckmans, his daughter.

— Geremie R. Barmé, Editor, China Heritage

Distinguished Fellow, The Asia Society

14 August 2022

Eternity is in love with the productions of time.

— William Blake, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell

***

***

Gales of Exile

流亡的天上大風

— Introducing From Heaps of Ashes

Xu Zhangrun

translated by Geremie R. Barmé

‘… people who do not read fiction or poetry are in permanent danger of crashing against facts and being crushed by reality. And then, in turn, it is left to Dr Jung and his colleagues to rush to the rescue and attempt mending the broken pieces.’ [Xu Zhangrun quoting Pierre Ryckmans in the introduction to From Heaps of Ashes.]

In the wake of the calamity that I have experienced since 2020, I have found solace in the ‘magnificent uselessness’ of literature. In particular, the novels of Erich Maria Remarque and the poetry of Joseph Brodsky have been my salvation. Their agonies and their joys have rescued me. Their boundless thirst for life and their contempt for the perversities of human nature are as a raft for my solitary soul, one on which I navigate my way by the stars and steer a course with the wind in my sails. On this raft I have been able to traverse the ocean of my desolation.

Losing myself in their works I have been able to meld their literary élan with my own existence. Thus, I have survived and I live on. In their company I exist in the flow of time and the boundlessness of meaning, I am a wayfarer on the turbulent seas of eternity where past and present overlap.

As a character in a novel by Mario Vargas Llosa puts it:

‘Life is a shitstorm, in which art is our only umbrella.’

(“La vie est une tornade de merde, dans laquelle l’art est notre seul parapluie.”)

Masters Remarque and Brodsky: in your persons, in your works and through the cultural nourishment that you bequeathed, you have also offered me an umbrella that protects me from the vicissitudes of fate and the fragility of life, an umbrella that shields me from the shitstorm that is my life.

Your bounty allows me to travel back and forth between my unquenchable thirst for life and the despairing borderlands of obliteration. My native reflexes that force me to go on regardless mean that I can can still observe the scudding clouds in the sky that leave no trace and, every day, I can be startled anew by the morning frost and the autumn leaves bunched up at my doorstep. Your marmoreal example emboldens me to persist, no matter how abject and fragile my own state. At dawn, I stir myself to write and can thereby roam over the vastness of the world, carried forth like a reed in a storm. I do not act out of some befuddled sense of purpose, rather it is the typhoon of reality that constantly excites me into action. Pour my soul into my writing I level my accusations and address the world about what has happened to my homeland. My resolve and my trajectory are that of a boulder and just as full of purpose as that famous Stone.

⋯ “一個人若不看小說,也不讀詩,便等於硬碰硬地撞在現實的墻壁上,弄得頭破血流,要不就是整個被沉重的現實壓垮,這時得向榮格和其他心理學家求助了,收攏破裂的碎片,重新組合。”

回想庚子已還,正是文學的“崇高的無用”救了我,是雷公和布神救了我,是它們和他們的沉痛與欣悅救了我,是他們對於生命的無限眷念和痛恨於人性的九曲回腸,化作一葉扁舟,如啟明的星辰展開了風帆,將我渡過這片人間的沙海。沉潛於他們的作品,便是努力在跟他們於此在之人格同一化,由此活著,活在時間裡,活在意義中,活在今古一脈連綿不絕的大化滄浪之間。無他,正如諾獎得主略薩的小說人物所言,“生活是場使得污穢滿天飛的龍捲風,而藝術是我們唯一的保護傘。”雷公和布神,你們,你們的作品,你們用命寫作而遺澤後世的爛漫篇章,就是我自認學關天意、而賤命一條的保護傘啊。承你們所賜,我因眷念多汁的愛情這一息意念而在冥河的此岸流連忘返,懷揣著動物性的慶幸,看天上大風滾過不留痕跡,看門前霜晨葉落而駭神驚心。因你們青銅有范,我靠形而上的貪慾所鼓蕩著的勃勃生命力的天真而苟活至今,黎明即起硯田筆耕於神馳八極,如風中的蘆葦。我不是因迷戀理念而行動,毋寧,是生活本身的龍捲風將我推搡、驅迫著去行動,也就是用文字去訴說心靈,為這方水土的不幸向世界哭訴,如心懷精靈般快意的永恆翻滾的石頭。

In the process of absorbing your works, as well as through words spoken and thoughts expressed over generation, each day I visit the Shrine of the Illustrious Heroes of Civilisation, and there I tarry. Nearby I have been building my own pantheon so I can constantly confront the misdeeds of this tyranny and its unpredictable nature. This then is my own umbrella and it shields me from the shitstorm of China’s reality. There Job’s pleas resound and travel far and wide. Even as ‘the age of homelessness has dawned’ [as Czesław Miłosz put it in ‘Why Religion?’], I have found a spiritual home, and it is one that accommodates a multitude. My home, my abode is [, as the Zen monk Ryōkan wrote,] ‘on the Eastern shores of the Milky Way …’.

In the ‘Reminiscences of Leo Nikolaevich Tolstoy’ that he compiled over 120 years ago, Maxim Gorky once observed the old writer:

‘He was sitting with his head on his hands, the wind blowing the silvery hairs of his beard through his fingers: he was looking into the distance out to sea [, and the little greenish waves rolled up obediently to his feet and fondled them as they were telling something about themselves to the old magician.

‘It was a day of sun and cloud, and the shadows of the clouds glided over the stones, and with the stones the old man grew now bright and now dark. The bowlders were large, riven by cracks and covered with smelly seaweed; there had been a high tide. He, too, seemed to me like an old stone come to life, who knows all the beginnings and the ends of things, who considers when and what will be the end of the stone, of the grasses of the earth, of the waters of the sea, and of the whole universe from the pebble to the sun. And the sea is part of his soul, and everything around him comes from him, out of him. In the musing motionlessness of the old man I felt something fateful, magical, something which went down into the darkness beneath him and stretched up like a searchlight into the blue emptiness above the earth; as though it were he, his concentrated will, which was drawing the waves to him and repelling them, which was ruling the movements of cloud and shadow, which was stirring the stones to life. Suddenly, in a moment of madness, I felt, “It is possible, he will get up, wave his hand, and the sea will become solid and glassy, the stones will begin to move and cry out, everything around him will come to life, acquire a voice, and speak in their different voices of themselves, of him, against him.” I can not express in words what I felt rather than thought at that moment;] in my soul there was joy and fear, and then everything blended in one happy thought: “I am not an orphan on the earth, so long as this man lives on it.”’

By engaging with these two masters — Erich Maria Remarque and Joseph Brodsky — I am similarly emboldened:

‘I am not an orphan on the earth, so long as their writing lives on.’

The age of homelessness is at hand. Its presence is constant; it is never far off. However, the homeless are at home in exile, just as poetry could cleave Mount Buzhou. Those who reprimand may readily be reprimanded in turn. It matters not. We have suffered enough, now it is time to put ourselves to the test.

經此生命化過程,藉此隔代言說和運思,我徜徉於文明的先賢祠,而為自己建構了一個私人萬神殿,為的是可以在面對、時刻面對強權和暴政的迫害與不測時,為自己營造一方遮風擋雨的安身立命之所。在那裡,約伯的呼號,響徹各各地。“無家的時代已經來臨”,我卻由此而有了一個棲息的精神家園,我卻因此而擁有眾多的精神家庭成員,我的家,我的家喲在“銀河河灘/之東……”。 一百二十多年前,高爾基觀察晚年的托爾斯泰,只見他獨自面朝大海坐著,雙手托著下巴,指間銀鬚隨海風飄拂,如同一塊遠古的、有了生命的、知曉萬物的開始和終結的石頭,那時,伴隨著歡樂和恐懼,觀察者湧現心頭的唯有一種強烈的幸福感:“只要這個人活在塵世,我就不會成為塵世上的孤兒。”轉用此語,不妨說,雷公與布神啊,“只要你們的作品依舊行世,我就不會是塵世的孤兒。”

是的,無家的時代已經來臨,早已經來臨,從來就不曾離去,流亡者偏就以此時代為家,如歌的斧斤砍向不周之山。譴責可能遭遇譴責,那就譴責吧;我們受夠了折磨,該是輪到折磨去盡情折磨自己的時候了。

— an excerpt from the introduction to Xu Zhangrun 許章潤, From Heaps of Ashes — reading Erica Maria Remarque and Joseph Brodsky, rejecting the barbarism of our times《雷馬克與布羅茨基——一個基於「劫灰意識」的「反人牲主義」》

***

Related Material:

- ‘A Day in the Life of Xu Zhangrun’, SupChina, 1 August 2022

- ‘Composed of Eros & of Dust — Xu Zhangrun Goes Shopping’, China Heritage, 31 December 2020

- ‘Cyclopes on My Doorstep’, China Heritage, 22 December 2020

***

In Praise of Reading and Fiction

‘Like writing, reading is a protest against the insufficiencies of life. When we look in fiction for what is missing in life, we are saying, with no need to say it or even to know it, that life as it is does not satisfy our thirst for the absolute — the foundation of the human condition — and should be better. We invent fictions in order to live somehow the many lives we would like to lead when we barely have one at our disposal.’

— Mario Vargas Llosa, Nobel Lecture, 7 December 2010

***

The Fish are Happy

Pierre Ryckmans

Zhuang Zi and his friend the logician Hui Zi were taking a stroll on the bridge over the River Hao. It was a beautiful day, and they stopped for a moment to watch the little fish below. Zhuang Zi said, ‘Look at the fish, how free and easy they swim-that is their happiness!’ But Hui Zi immediately objected, ‘You are not a fish; whence do you know that the fish are happy?’ ‘You are not me,’ replied Zhuang Zi, ‘how can you possibly know that I do not know if the fish are happy?’ Hui Zi said, ‘We’ll grant that I am not you, and therefore cannot know what you know. But you must grant that you are not a fish, and therefore cannot know whether the fish are happy or not.’ Zhuang Zi replied, ‘Let us return to the original question. When you asked me “Whence do you know that the fish are happy?” your very question showed that you knew that I knew. Still, if you insist on asking whence I know, I will tell you: I know it from this bridge.'[1]

To make a minute exegesis of such a piece would ruin it—it would be as brutish as pulling off the wings of a butterfly. Still, I merely wish to underline one point. Hui Zi’s attitude represents the fallacy of a certain cleverness. With his abstract logic, he attempts to erode Zhuang Zi’s living grasp of reality. But Zhuang Zi, in turn, develops his unanswerable riposte in two movements, on two different levels. In a first move, he shows Hui Zi that he can beat him at his own game, countering logic with logic. Indeed, on a strictly formal level, a question of the type ‘Whence do you know’ does not put your knowledge into question—it takes it for granted, and merely queries the starting point of your inference. But Zhuang Zi does not stop there; to win a sterile contest of wits is unsatisfying. In his final move, with a pun, he breaks free from the fetters of empty intellectual games, and enters the realm of reality, which in the end, alone matters. Borrowing Hui Zi’s original word whence, he transforms its meaning: whereas Hui Zi had used it in the abstract sense of logical deduction, Zhuang Zi now takes it in its literal sense—’from which point in space’—and he answers it literally. But the literal answer proves also to be the most profound-more profound even than the truth, for any truth can only be about reality, whereas here we reach what truth is about: reality itself, which is irrefutable: I know it from this bridge. Here, one is reminded of Samuel Johnson’s powerful retort to an interlocutor who had invoked Berkeley’s idealism, questioning the reality of reality: without a word, he vigorously kicked a rock of good size, that was lying on the ground.[2]

Looking from the bridge, to know that the fish are happy is ultimately an act of faith. The saying ‘to see is to believe’ must be reversed: to believe is to see.

Notes:

[1] Zhuang Zi, chapter 17, ‘Autumn floods’. For English translations, see Burton Watson, The Complete Works of Chuang Tzu, New York & London: Columbia University Press, 1986, pp.188-9; see also A. C. Graham, Chuang Tzu: The Inner Chapters, London & Sydney: Unwin Paperbacks, 1986, p.123.

[2] ‘After we came out of church, we stood talking for some time together of Bishop Berkeley’s ingenious sophistry to prove the non-existence of matter, and that everything in the universe is merely ideal. I observed that, though we are satisfied his doctrine is not true, it is impossible to refute it. I never shall forget the alacrity with which Johnson answered, striking his foot with mighty force against a larger stone, till he rebounded from it, “I refute it thus”. This was a stout exemplification of the first truths of Père Bouffier, or the original principles of Reid and of Beattie, without admitting which we can no more argue in metaphysicks, than we can argue in mathematicks without axioms.’ Boswell, Life of Johnson (entry of 6 August 1763).

— from Pierre Ryckmans, ‘Learning’ in

The View from the Bridge: Aspects of Culture (1996)

reprinted with the author’s permission in

China Heritage Quarterly, Issue 27

***

The View from the Bridge: Aspects of Culture

Pierre Ryckmans (ABC Boyer Lectures, 1996)

***

Art shields us from the storms of life

Pierre Ryckmans

28 May 2002

Some time ago, the English actor Hugh Grant was arrested by the police in Los Angeles. He was performing a rather private activity in a public place, with a lady of the night. For less famous mortals, such a mishap would have been merely embarrassing, but for such a famous film star the incident proved quite shattering.

In this distressing circumstance, he was interviewed by an American journalist, who asked him a very American question: “Are you receiving any therapy or counselling?” Grant replied: “No. In England, we read novels.”

Half a century earlier, the great psychologist Carl Gustav Jung developed the other side of this same observation. He phrased it in more technical terms: “Man’s estrangement from the mythical realm and the subsequent shrinking of his existence to the mere factual — that is the major cause of mental illness.” In other words, people who do not read fiction or poetry are in permanent danger of crashing against facts and being crushed by reality. And then, in turn, it is left to Dr Jung and his colleagues to rush to the rescue and attempt mending the broken pieces.

Do psychotherapists multiply when novelists and poets become scarce? There may well be a connection between the development of clinical psychology on the one hand, and the withering of the inspired imagination on the other — at least, this was the belief of some eminent practitioners. Rainer Marie Rilke once begged Lou Andreas Salome to psychoanalyse him. She refused, explaining: “If the analysis is successful, you may never write poetry again.” (And just imagine: had a skilful shrink cured Kafka of his existential anxieties, our age — and modern man’s condition — could have been deprived of its most perceptive interpreter.)

Many strong and well-adjusted people seem to experience little need for the imaginative life. Thus, for instance, saints do not write novels, as Cardinal Newman observed (and he ought to have known, since he came quite close to being a saint, and he wrote a couple of novels).

Practical-minded people and men of action are often inclined to disapprove of literary fiction. They consider reading creative literature as a frivolous and debilitating activity. In this respect, it is quite revealing that, for example, the great polar explorer Mawson — one of our national heroes — gave to his children the stern advice to not waste their time reading novels; instead, he instructed them to read only works of history and biography, in order to grow into healthy individuals.

This reflects two very common fallacies. The first consists in failing to see that, by its very definition, all literature is in fact imaginative literature.

The second results from a mistaken notion of what “health” is.

Whatever fragile harmony we may have been able to achieve within ourselves is exposed every day to dangerous challenges and to ferocious batterings, and the issue of our struggle remains forever uncertain. A character in a novel by Mario Vargas Llosa gave (what seems to me) the best image for this common predicament of ours: “Life is a shitstorm, in which art is our only umbrella.”

This observation, in turn, brings us to the very meaning of the NSW Premier’s Literary Awards. Any well-ordered state must naturally provide for public education, public health, public transports, public order, the administration of justice, the collection of garbage, etc. Beyond these essential services and responsibilities, a truly civilised state also ensures that, in the pungent squalls of their daily lives, citizens are not left without umbrellas — and therefore, it encourages and supports the arts.

The beauty of all literary awards is that they produce only winners — there can be no losers here, for this is not a competition and, in this respect, actually resembles more a lottery.

Without doubting the quality of his work, a writer who receives a literary award is perfectly aware that he is being very lucky indeed. Not only he knows that this honour could have gone to any other writer on the short list, but he also knows that there are many writers not on the shortlist, who may have deserved it equally well; and furthermore, it is quite conceivable that the writer who should have deserved it most did not even succeed in having his manuscript accepted for publication.

Yet these considerations should not tarnish in the least the happiness of the winners. Ultimately, lotteries are designed to benefit not their winners, but handicapped children, or guide dogs for the blind, or whatever good cause is sponsoring them. And it is the same with the literary awards: year after year, they have only one true and permanent winner, always the same — and it is literature itself, our common love.

***

- This edited version of the address Pierre Ryckmans made on the occasion of the NSW Premier’s Literary Awards on 27 May 2002 appeared in The Sydney Morning Herald on 28 May 2002. The full text was published under the title ‘Notre seul parapluie — Du rôle de l’art dan les expéditions polarizes en particulier, et dans la vie en général’, in Simon Leys, Le bonheur des petits poissons — Lettres des Antipodes, Paris: JC Lattès, 2008

Pierre Ryckmans

Remembering a man of letters, and a friend

Murray Bail

“Dying is so banal,” Pierre Ryckmans said from his bed in Sydney a few weeks before he died. To a visitor who suggested he’d call again the following week, on the Tuesday or Wednesday, he said from his bed set up in the lounge room facing the harbour and the sunrises, “I’ll be here.” And now that he has died he is here, and yet not here. He is no longer here, not among us anymore, no more of his enquiring conversations, and the letters written in a small hand, not with a fountain pen, certainly not a biro, but one of those Rapidographs, employed by architects and town planners in the 1960s, his Canberra address written in full on top of the letter, and written again – just in case – on the back of the envelope, also in Indian ink, letters which sometimes consisted almost entirely of additions to a thought marked by an asterisk, and written at right angles to the main letter. The meandering manner of his letters became his distinctive style which had spilled over from his essays, the Montaigne method taken to extreme. Some years ago he made the journey to Montaigne’s chateau in Bordeaux and had himself photographed at the front gate.

Pierre Ryckmans is no longer here in any of those sorts of appearances, yet he remains with us through his one and only novel, or novella, The Death of Napoleon, and his essays, mostly for the New York Review of Books and various French journals, often reviews which had spread into essays, and his translation of Confucius (1997), which is notable for having more pages of notes, all interesting – more than interesting – than the entire Analects. At least a writer can be conscious of a slight advantage: there is always the possibility of an afterlife, although the writer cannot know if or for how long it will be, even if in the next century somebody picks up a writer’s book from a dusty shelf, or in a rubbish tip, and begins reading.

A writer’s thoughts can be transmitted when he is no longer thinking. In 1971 Pierre’s indignant view of China after Mao and the Cultural Revolution, set out in The Chairman’s New Clothes followed by Chinese Shadows, landed like a rock in a pond, giving fright to the fish feeding near the surface, the ripples which affected a generation still spreading. But the list of essayists who continue to be read after a hundred years is not long – Montaigne, Hazlitt quickly come to mind. Many more?

Dumas, Victor Hugo and Dickens, whose novels were immensely popular in their day, had over time mysteriously entered the upper echelons of the high-cultural, Pierre liked to point out. Such a trajectory fitted his conservative instincts. Although he knew most of French literature, including much that is yet to reach English, as well as the main Russian and German novels, his persistent interest – curiously – leaned towards England: Chesterton, Maugham, Evelyn Waugh and Graham Greene were some. And Johnson: he would not allow a word to be said against Dr Johnson, even the Doctor’s absurdly trenchant, “No man but a blockhead ever wrote except for money” – although Pierre himself never wrote merely for money.

He was a conservative, the product of a Catholic childhood in Brussels. It was a family of long-established law publishers. An uncle was governor-general of the Belgian Congo. All very solid. Perhaps too solid. In 1949 his brother entered a monastery, where he remained for many years. Pierre turned east, to the vast complexity of China. Remaining European, he turned from Europe. To his wife, Hanfang, he would begin a sentence in English, switch to French, then finish in Mandarin. At the same time, Pierre’s traditional values were given flexibility by his attraction to personalities who had broken free of the majority. Mother Teresa in the Calcutta slums Pierre defended against Christopher Hitchens. And there was Simone Weil, an infuriating outsider of a different order. In 2012 Pierre translated and introduced Weil’s utopian pamphlet proposing the abolition of all political parties, which in itself is way to one side, almost to the hinterland of the other side. His sympathies extended to George Orwell, the Etonian turned policeman who argued clearly and firmly against the establishment; and when Pierre spoke of Géricault it was not the well-known Raft hanging in the Louvre or the paintings of shivering horses, but his five portraits of patients from an insane asylum.

He could hardly be called a relativist, or a post-modernist; he wasn’t even a modernist. These were academic definitions. And it was Pierre, remember, who had wondered aloud (in print) whether universities were needed, as if they were like so many Belgiums in miniature.

If he thought a work deserved it, he readily proclaimed “a masterpiece!” This he applied to the gold standards, such as Proust and War and Peace, but also to the lesser known, Canetti’s The Voices of Marrakesh, for example, or a Simenon novel. It was refreshing to have someone nearby to honour without apology the highest achievements in art. The last film he saw was in black-and-white from Poland, Ida. It was the most affecting film he had seen in years, a masterpiece.

An assiduous cultural tourist he nevertheless (in the Boyer Lectures) spoke of the reductions produced by mass tourism, how the visual experience was altered, even diminished by the unseeing crowds. Vermeer, Bruegel, Daumier and Corot were some of the painters he admired. Of the moderns it was Vuillard, Bonnard, not Cézanne; Bonnard’s spreadeagled nude in the National Gallery of Victoria was one of Pierre’s “it’s a masterpiece!”, as it surely is. He was forever curious as to why anyone should prefer Cézanne.

Similarly, of Australian painters he preferred Lloyd Rees to Sidney Nolan. And yet it was Fairweather who lived in isolation on a mosquito-infested island he responded to most, partly because of Fairweather’s Chinese line and subject matter – only partly, because it was always the spiritual that Pierre expected from art. His essay on Fairweather, where he places him in the exalted tradition of the amateur in Chinese painting, remains one of the best things written about the artist. Aside from Chinese calligraphies he was wary of abstraction. And he actually found it worthwhile every year to trudge around the Archibald Prize portraits, with a mind open to surprise.

He was industrious, yet he wrote essays in praise of doing nothing.

In 2007 he “wrote” a book, Other People’s Thoughts, consisting entirely of quotations of others. It begins, “Adventure is a product of incompetence” – Amundsen.

More and more he became interested in the lives of writers, how their behaviour in ordinary life, their marriages and so on, was in contradiction to the more nuanced and compassionate treatment given to their characters – Tolstoy would have to be the most alarming example. Pierre’s affectionate essay on Balzac which catalogues some of his contradictions and his bizarre behaviour generally is so relentless as to have the reader unable to stop laughing – in admiration of both Balzac and the essayist – and in the one on Simenon, he marvels in a forensic aside at the crime writer’s staggering output and his staggeringly prolific success with women. Often he preferred the short reminiscence: he said he got more from Shirley Hazzard’s sightings of Graham Greene on Capri than all the words in the official three-volume biography.

Pierre was drawn to water, even the brown shallows of Canberra’s Lake Burley Griffin, where he managed to sail, but especially the ocean. The attraction was certainly not trivial: his history of the sea in French literature, published in French in 2003, came to two volumes, and later there was his account of the wreck of the Batavia, concentrating on the gruesome behaviour of the survivors. Perhaps without realising he included an “octopus” in the title of one of his books of essays. With his silver beard Pierre from some angles maintained a nautical air. The number of copies of Two Years Before the Mast he handed around must have kept the book afloat. He envied anyone who had been on a recent voyage, and turned positively childlike in anticipation of travelling around the Pacific visiting islands for 15 days in 2010, on a French warship of his choosing, one of the fringe benefits of being made an Honorary Commander along with 19 other writers, of the French Navy. Needless to say, he had read Conrad many times, a writer of many masterpieces, not only the novels and stories (‘The Secret Sharer’), his essays and letters, and every scrap concerning his life, quoting the extreme difficulty Conrad suffered in writing, although the final results showed no trace of difficulty at all.

Pierre was attentive, softly spoken. It is unusual for anybody, especially over 65, to centre their conversations unaffectedly around questions. As he turned slightly deaf, he would lean forward, more attentive still. Only when giving approval, “a masterpiece!”, did the voice rise, although playing boules he was inclined to shout out “merde!” a bit too freely. A gent, who opened the champagne; yet now and then he smoked a cheap dark cigar, and for some reason stopped halfway down, where he cut it to finish the next day. Again, this is not what a cigar smoker is supposed to do. He liked living in Canberra, he said, because it was “secretive”. And just to make quite sure, the house was in a cul-de-sac, with natural bush behind, away from the sea where he had asked for his ashes to be scattered.

***

Source:

- Murray Bail, ‘Remembering a man of letters, and a friend’, The Monthly, October 2014

***

Mandarin in Extremis

There’s an absolutely wonderful story, I don’t know where I read it, perhaps in Plato, which recounts how when they brought the poison to Socrates, they found him studying Persian. ‘But why are you studying Persian?’, they asked. Socrates replied, ‘Simply because I want to learn Persian. Ah — so I have to take the hemlock now? Then I’ll take it.’ This strikes me as absolutely marvellous. God grant that Death finds me thus, trying to learn Mandarin Chinese.

— Mario Vargas Llosa, interview with María Luisa Blanco, Babelia, 20 May 2006, translated by Richard Rigby and quoted in ‘More Other People’s Thoughts’, China Heritage, 8 May 2017

***