Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium

Appendix XIII

專

In July 2018, the Tsinghua University professor Xu Zhangrun published a point-by-point critique of the Chinese Communist Party and Xi Jinping, its Chairman of Everything. In his biting broadside, one composed in elegant and at times bitingly humorous literary Chinese, Xu warned of the dangers of one-man rule, a sycophantic bureaucracy, putting politics ahead of professionalism and the myriad other problems that the system would encounter if it rejected further reforms. He appealed to the Chinese party-state to rein in Xi Jinping’s monomania before it was too late. That July 2018 Jeremiad was one of a cycle of works in which Xu repeatedly reminded his readers of the pressing issues related to China’s momentous struggle with modernity, the state of the nation under Xi Jinping and the mixed prospects for its future.

Xu Zhangrun would pay a heavy price for having published ‘Imminent Fears, Immediate Hopes’ — a Beijing Jeremiad 我們當下的恐懼與期待. Dismissed from his job as a professor of jurisprudence at Tsinghua University, banished from the campus and stripped both of his pension and his accreditation as a teacher, from mid 2020, Xu has lived in internal exile in the western suburbs of Beijing where, despite constant threats from the police and Chinese secret service, he continues to read, write and, when possible, publish. His is a Chinese voice of conscience that refuses to be cancelled.

In July 2021, China Heritage invited Professor Xu to comment on the third anniversary of the appearance of his ‘Imminent Fears, Immediate Hopes’. He composed an essay titled ‘Alarms and Excursions Permit No Peace’笳鼓悲鳴遣人驚 in response, a translation of which was published in The New York Review of Books under the title ‘Xi’s China, the Handiwork of an Autocratic Roué’. Below we reprint that essay and publish the original Chinese text for the first time. This is followed by an interview conducted by Matt Seaton of NYRB with the author and translator. We conclude with Bertrand Russell’s reflections on meeting V.I. Lenin in Moscow in 1920.

Upon learning that Xu Zhangrun had published yet another highly critical appraisal of Xi Jinping, his ‘keepers’ (state security and police officers) yet again subjected him to hours of interrogation, furious threats and verbal abuse. He responded by repeating his stance, formulated in July 2018, that jail was the only way to silence him.

***

In our series Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium, we previously noted that:

‘The threnody of the Xi Jinping decade is tedium, something born of the ceaseless oscillations within China’s hermetically sealed system and it signals its deadening presence through reversals and the glum repetition of various tropes of the past. In this era, what was formerly limited divergence has given way to convergence, difference to singularity, diversity to homogeneity. Where in the past there was wriggle room, a straitjacket now awaits; possibility is all too frequently replaced by ordained inevitability; contingency by certainty and the unpredictable is met with inflexibility and harshness. For those who have lived with China’s party-state over the decades the déja-vu quality of the Xi era is undeniable. It is an age that sets itself against the unpredictable, the contingent, against the disheveled nature of reality itself; as a result it is implausible, brittle and in constant crisis-mode….’

We have also repeatedly made the case that Xi is a logical extension of the Chinese Communist Party’s determination to cleave to its ideological traditions and structures of power.

‘[He] has, at great cost and with immense effort kept contending political, economic and social forces at bay. By foreclosing the future, Xi Jinping has, as we have noted elsewhere, and writers as diverse as Xu Zhangrun and Fang Zhou have noted, trapped China in a new vicious cycle of suffocating repetition. This phenomenon is by no means unique to China, since revisionism, the unresolved legacies of the past and historical repetitions bedevil many countries. In the case of the People’s Republic of China, however, there are no countervailing forces allowing for debate or an open-ended possibility of change. As a result, a sense of tedium is born not only of the repetitious nature of much that has been happening, but a wide-spread awareness that what has been undone during the Xi Jinping decade will, at some point in the future, itself have to undone.’

It is this claustrophobic cycle of becoming — and the grim prospects for meaningful social and political evolution in China in the short to medium term — that, in 2018, led Xu Zhangrun to speak out. Today, four years later, we commemorate his courageous rebellion in writing.

***

In ‘Aspects of Mao’, an essay written only days after the death of Mao in September 1976, Simon Leys observed that:

‘China has lost her “Great Leader”. This should allow her at last to start forging ahead again, after an all too long and abnormal interlude of chaotic rule and cultural stagnation. For a nation such as the Chinese, the loss should not be crippling: do truly great peoples ever need a “Great Leader”?’

We preface Xu Zhangrun’s evaluation of Xi Jinping, a man now hailed by the official media as ‘The People’s Leader’ 人民領袖 with a few words about China’s ‘uncrowned king’ 無冕之王. As the first decade of Xi Jinping’s rule draws to a close, nearly half a century after Mao’s demise, many ask whether in the twenty-first century China really needs ‘A People’s Leader’?

— Geremie R. Barmé, Editor, China Heritage

Distinguished Fellow, The Asia Society

20 July 2022

***

‘We have no need of any of this’

‘…we have the same job we always had, to say, as thinking people and as humans, that there are no final solutions, there is no absolute truth, there is no supreme leader, there is no totalitarian solution that says that if you will just give up your freedom of inquiry, if you would just give up, if you will simply abandon your critical faculties, a world of idiotic bliss can be yours. We have to begin by repudiating all such claims – grand rabbis, chief ayatollahs, infallible popes, the peddlers of mutant quasi-political worship, the dear leader, great leader, we have no need of any of this.’

— Christopher Hitchens, from the conclusion to remarks made in October 2011 upon receiving the Atheist Alliance of America’s Richard Dawkins award. It was his last public speech

***

Further Reading:

- We Need to Talk About Totalitarianism, Again, China Heritage, 31 March 2022

- Prelude to a Restoration: Xi Jinping, Deng Xiaoping, Chen Yun & the Spectre of Mao Zedong, China Heritage, 20 September 2021

- Justified Fears, Diminished Hopes, Unflagging Faith — Revisiting Xu Zhangrun’s July 2018 Jeremiad, China Heritage, 8 August 2021

- Geremie R. Barmé, One Decent Man, The New York Review of Books, 28 June 2018

- Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium, China Heritage, 1 January 2022-

- Xu Zhangrun Archive, China Heritage, 1 August 2018-

Contents

***

***

The People’s Leader

人民領袖

China’s state media began referred to Xi Jinping as ‘The Leader’ 領袖 lǐngxiù as early as 28 January 2014. People’s Daily published an account of popular Russian views of Xi based on the two times he had visited the Russian Federation. The report was titled ‘Approachability is the Manifestation of the Personal Demeanor of The Leader of a Great Power’ 平易近人中更顯大國領袖風采 and it claimed that a Russian graduate scholar in international relations had referred to Xi as ‘The Leader of a Great Power’ 大國領袖. Again, on 9 May 2015, People’s Daily online reported that a Russian scholar had hailed Xi for ‘being possessed of the demeanor of a Leader’ 領袖風采 lǐngxiù fēngcǎi. By using a not-uncommon form of linguistic sleight of hand China’s official media had introduced the concept of Xi Jinping as ‘The Leader’ by quoting foreign sources.

China had not had a 領袖 lǐngxiù since the days of Mao and once this old ‘trigger word’ was linked to Xi Jinping’s name there seemed to be no going back. On 1 October 2015, for example, during Xi’s state visit to the United States and participation in the summit meeting held to celebrate the seventieth anniversary of the United Nations held in New York, he was repeatedly hailed for his ‘demeanor as Leader’ 領袖風采. At the Sixth Plenum of the Eighteenth Party Congress over which Xi presided in October 2016, he was elevated to become ‘The Core’ 核心 héxīn of China’s Communist enterprise and in a series of articles on Party theory published by People’s Daily the following month he was repeatedly referred to as ‘The Leader’ 領袖 lǐngxiù.

Following the Nineteenth Party Congress held in late October 2017, Xi Jinping started his second five-year term in office and in a People’s Daily puff piece one of his Politburo comrades referred to him as ‘The Leader’, even though he was theoretically still primus inter pares. Meanwhile one local media outlet in Guizhou province, anxious to curry favour with Beijing, having detected the shift in the discursive-rhetorical terrain published a portrait bombastically titled ‘Our Great Leader General Secretary Xi Jinping’ 偉大領袖習近平總書記。It was the first time China had a ‘Great Leader’ since the demise of Mao just over forty years earlier.

***

***

Deng Xiaoping, whose legacy Xi Jinping was in the midst of dismantling, was now dragooned into supporting the rhetorical shift and Politburo member cum-sycophant Zhao Leji 趙樂際 quoted the long dead ‘architect of reform’ to the effect that:

‘The Party must have a leader and a leadership core.’ 黨一定要有領袖,有領導核心。

As his second term in office began, Xi Jinping was hailed as being ‘The Leader who is making China not only wealthy but also strong’ 一個使中國由富變強的領袖。And, on 18 November 2017, the leading Party news outlet published a report titled ‘Ten Things That Are Evidence of the Charismatic Leadership of Xi Jinping’ 十个真实细节带你感受习近平的领袖魅力。In the build up to the March 2018 convocation of the National People’s Congress at which the Chinese Constitution was revised to allow Xi Jinping potentially terminal tenure, People’s Daily and China Central TV produced a series of pre-Spring Festival videos titled ‘The People’s Leader’ 人民領袖. It was in this heady atmosphere of old-time fawning that Professor Xu Zhangrun, who had been writing pointed essays about the direction China was heading under Xi Jinping since early 2016, began planning his famous July 2018 jeremiad. He was further provoked by statements such as the following, made by Li Zhanshu 栗戰書, a consigliere-esque favourite of Xi’s who was both a Party leader and Chairman of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress, on 20 March 2018:

‘Comrade Xi Jinping is the Unquestioned Core of Our Party who is both firmly supported by the Whole Party and Beloved of the People. He is the Generalissimo of Our Armed Forces and The People’s Leader. He is the Helmsman guiding the nation on its journey of building Socialism With Chinese Characteristics in this New Epoch. He is The People’s Guide.’

習近平同志是全黨擁護、人民愛戴、當之無愧的黨的核心、軍隊統帥、人民領袖,是新時代中國特色社會主義國家的掌舵者、人民的領路人。

From 2019, it has been commonplace to hail Xi Jinping as ‘The Leader’ and local Party bosses have vied with each other to heap the Chairman of Everything with cringeworthy accolades both in the expectation that he would continue in office beyond 2022 and as part of the manufactured ‘grassroots’ support for him doing so.

The ambitions of Xi Jinping and his courtiers are not, however, limited to his being crowned ‘The People’s Leader’ in China. On 25 June 2022, Reference News, a Party organ that is often used to reassure the leadership that their wisdom and unparalleled genius is also recognised on the international stage, published a lead report modestly titled:

‘Xi Jinping Points the Way for the Development of the Whole World’

習近平為全球發展指明方向

Official China’s media constantly lauds Xi Jinping for ‘pointing the way’ 指明方向 in all realms of Chinese life, thought and governance. In response, wags both on- and off-line mockingly refer to him as ‘Emperor Pointer’ 指明帝王.

Source:

- Much of the above material is digested from Ping Fan 平凡, ‘中共二十大臨近,「領袖」稱號進入快車道’,《美國之音》,2022年7月14日

***

Xi’s China, the Handiwork of an Autocratic Roué

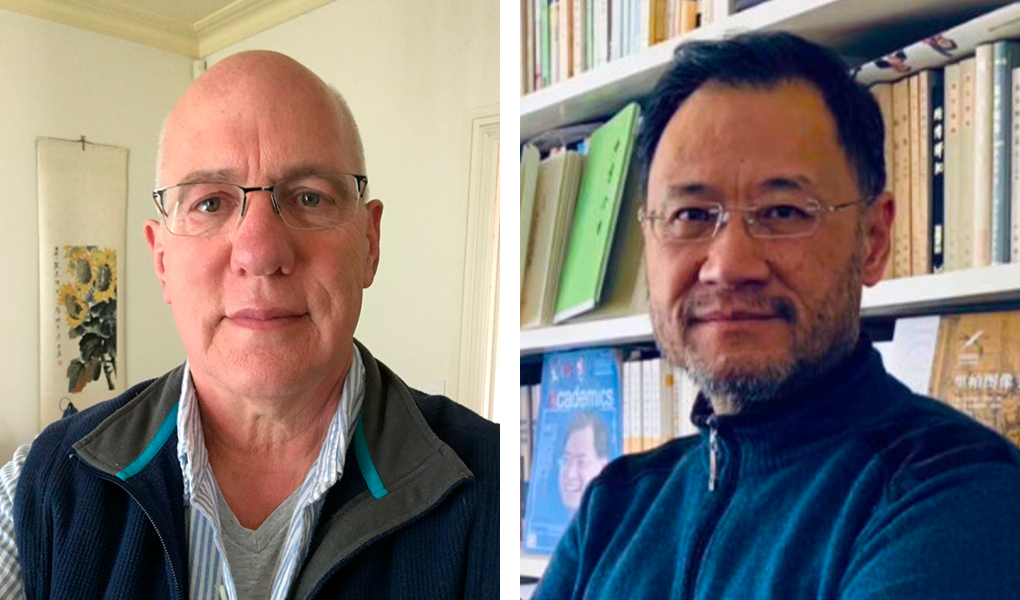

Xu Zhangrun, translated by Geremie R. Barmé

“Of course, the regime has rained down punishments on me for my criticisms; I expected that. It only exposes its inherent fragility and unfitness for the modern world.”

— August 9, 2021

Translator’s Note: Xu Zhangrun was, until last year, a professor of jurisprudence at Beijing’s Tsinghua University, one of China’s most prestigious colleges. A celebrated lecturer and author of numerous works on the law, he was a noted essayist, and also the editor of a major series of books on legal reform.

In July 2018, Xu published “Imminent Fears, Immediate Hopes,” a point-by-point critique of the policies of Xi Jinping’s government. Since then, he has been subjected to relentless persecution—his life’s work has been outlawed, his online presence deleted, and his career destroyed. Dismissed by Tsinghua in 2020, stripped of his pension, housing, and teaching credentials, Xu now lives in a book-filled apartment in the far western suburbs of Beijing, getting by on his savings. He is forbidden from leaving the city or accepting help from friends.

In February this year, Geng Xiaonan, a noted cultural activist and Xu’s most outspoken supporter, was sentenced to three years’ jail in a far-flung women’s penitentiary. Tried on charges related to her publishing business, few observers doubt that the real reason for her punishment was her advocacy on behalf of Xu Zhangrun and other dissidents.

Even with numerous sound-sensitive CCTV cameras trained on his apartment, and regardless of continued abuse and interrogations, Xu persists in his writing. His latest book, Ten Letters from a Year of Plague, has just appeared through an independent Chinese publisher in New York.

The following essay, adapted and edited in translation, was written to mark the third anniversary of the publication of “Imminent Fears, Immediate Hopes.”

— Geremie R. Barmé

***

- A Note on ‘Roué’:

Here and elsewhere, Xu Zhangrun has mocked Communist Party leaders like Xi Jinping and the purged Bo Xilai for pursuing what he calls ‘The Politics of the Successor Playboys’ 公子哥式治國. 公子哥兒 gōng zǐ gē ér is a term used to describe the self-indulgent wastrels of the traditional imperial nobility. It denotes both lineage and lifestyle, and it reflects an attitude of unquestionable entitlement. Given the combination of Xi Jinping’s advanced years and adolescent political passions, I decided that ‘roué’, a term derived from the idea that ill-restrained individuals deserved to be ‘broken on the rack’, or rouer, could well apply to the shameless political posturing of the man who occupies the empty heart of China.

— GRB, 20 July 2022

In March 2018, the Chinese legislature approved revisions to the constitution that effectively put an end to the already minimal political advances achieved following the economic reform policies originally introduced by the Communist Party in late 1978. Although the revisions [which abolished term limits on national leaders, making it possible for President Xi Jinping to stay in power indefinitely] unsettled China’s legal world, the outrage was expressed sotto voce; the disquiet barely went beyond what in the Soviet Union used to be called “kitchen table talk.”

Meanwhile, in public, a host of obsequious legal scholars vied to offer fawning praise for the new dispensation. Seemingly unabashed as they betrayed previous held views, they gave no hint of any internal moral struggles or sense of ambivalence about their conversion. Quite the opposite: many appeared to relish the fact that they were able to navigate the situation so adroitly. Instead, they focused their energies on how they could best realign themselves and pursue professional advancement.

At this crucial juncture, China’s political, business, and academic elites revealed a core of craven self-interest and vacuous hypocrisy. The display was even further evidence of the degraded state of our nation’s public life, one that has long been characterized by brazen political opportunism, systemic corruption, and the celebration of populist thuggery.

Various edicts were issued from on high that banned all public discussion, let alone disapproval, of the constitutional changes. The authorities made it quite clear that dissent would be severely punished. In particular, legal scholars were cautioned to keep their own counsel.

At the time these changes were being proposed, I bumped into a colleague from Tsinghua University who had long enjoyed a seat on the National People’s Congress [the legislative body that would soon rubber-stamp the constitutional reforms]. He was quick to tell me that he, too, was outraged by the mooted changes. They were, he assured me, indeed absurd, an egregious act of revanchism. In the same breath, he said: “But I’m just letting off steam. Of course, when the time comes to vote, I’ll be raising my hand along with everyone else. No one is crazy enough to paint a target on their back.”

His attitude was evidently shared by a majority of the men and women who had a substantive say in the matter [with the revision passing by 2,958 votes to two]. Fear drove them to come up with various rationalizations for their actions, and so our country is now under the sway of a Great Reversal. This came to pass not in stealth, but openly and with the acquiescence and complicity of China’s intelligentsia. Their stance has proved to be little different from that of the imperial slave-subjects of yesteryear; it has hastened China’s lurch back into the familiar old rut of totalitarianism. What has all of this wrought? It is more than evident: we now live in a nation beset by mounting domestic and external challenges.

I believe that legal scholars like me are akin to a priesthood that serves natural law, rather than merely justifying the requirements of the state. We should be the guardians of a system of justice based on due process, one that ensures equality before the law; a system that is underpinned by the conviction that all citizens can and should feel secure in an environment of unthreatened coexistence. That is why, in 2018, I decided that to remain silent at such a critical moment would be a betrayal of my life’s work. If even people like me shied from speaking out at such a time, what hope was there for Chinese society?

My belief that it was incumbent upon educators like me to give voice to their indignation and concern publicly led me to write “Imminent Fears, Immediate Hopes,” an in-depth analysis and critique of the state of modern China. It was in a mood of immense relief that I published it online in late July 2018; I had acted out of a duty to speak up and my hope was that my words would reach as wide an audience as possible. I even dared to think that what I had said might embolden others to raise their voices.

“Imminent Fears, Immediate Hopes” was a warning to my compatriots, alerting them to things that were happening right here and now. It was an appeal calling on people to protect China’s reforms—hard-won advances derived from the immense sacrifices that countless numbers of our fellow citizens had made over four decades. It was also an exhortation to people to do what they could to prevent China’s further backward slide, one that I believe might all too easily lead to a new civil war. My admonition was also born of the anxiety that China could yet again find itself isolated by the international community.

Naturally, my essay was an open challenge to the powers-that-be, and I knew full well that by publishing it, I was courting disaster. Yet I was at peace with myself, and awaited with equanimity what fate had in store for me. As expected, the punishments rained down on me with increasing severity until, in the summer of 2020, the authorities finally bared their teeth.

They resorted to the tried-and-true methods of the proletarian dictatorship: they destroyed my livelihood and they incarcerated me. They hoped to repress my heresy by crushing my spirit. The only thing that they have managed to do, however, is to turn me into a semi-exile under partial house arrest in my own land. I was mentally prepared for all of this, and all that I had expected has duly been visited upon me. I regret nothing.

What does dismay me, however, is that since I published “Imminent Fears, Immediate Hopes,” everything I feared might happen has come to pass, and new evidence in support of my case emerges every day. The “Eight Fears” that I identified in July 2018 are now a reality. In the space of three short years, particularly after the Covid-19 pandemic, the totalitarian tendencies of the Chinese party-state have become more evident. What was already an obnoxious oligarchy has now been replaced by a Chinese version of the Führerprinzip, along with a brutal form of purge politics based on the Leninist-Maoist model.

Populist statism and institutional statism have become intertwined and now aid and abet what I have previously called “Big Data Totalitarianism.” In tandem with this, mainstream global politics have undergone profound changes in recent years. On the international stage, the politics of the “war on terror” is giving way to a new anti-Communist animus aimed at China. Previously, the People’s Republic enjoyed a collaborative and relatively harmonious relationship with the international community. That has seen a sea change as many nations have radically revised their views of our country and the direction it is taking. By generating imaginary enemies in all quarters, China is further isolating itself, even if the vast scale of the People’s Republic will ensure its continued international influence, at least for the time being.

As for my “Eight Hopes,” they remain nothing more than wishful thinking.

Today, China is yet again confronting a question that has long bedeviled it: Where do we go from here? As the Covid-19 pandemic gradually passes—and along with that crisis, the justification for the heightened totalitarian approach the government has employed to deal with it—China will, I believe, once more see support for a republican constitutional system that enjoys the benefits of a resilient and vital democracy.

I recall that in early 2020 the political philosopher Slavoj Žižek argued that the best way for the world to respond to the Covid-19 pandemic was to implement a version of “war communism.” Such wrongheaded sophistry suggested a cure to a medical crisis that would merely serve to open the door to a far more insidious infection of the body politic. Žižek’s summons to totalitarian politics is nothing less than an invitation to disaster. His proposal was absurd, ill-conceived, and delusional.

I have often referred to China’s party-state governance model as “Legalist-Fascist-Stalinism.” The rulers overwhelmingly concentrate on what are traditionally called the “Rivers and Mountains”; this [imperial concept] is their patria. When confronted by such questions as “What power have you got? Where did you get it from? In whose interests do you use it? To whom are you accountable? And how do we get rid of you?” the Chinese system is struck dumb, unable to respond.

More to the point, it is a system completely lacking the kind of democratic processes that can ensure a peaceful transfer of power. Without a stable political process of succession, the fate of the nation ultimately relies on armed might and coercion. In the final analysis, the authoritarian party-state system stands in stark opposition to historical progress, to human love, and to normal political life. That is why, to this day, it enjoys no real popular appeal.

Above, I observed that China has lurched back into “the familiar old rut of totalitarianism.” Despite appearances, the Communist Party has never veered far from that path. Its fundamental nature has remained unchanged and, whenever it has weathered a crisis, the Party merely redoubles its efforts. Whatever it may achieve is always hamstrung by the energy it puts into denying all other political possibilities and by its dogged refusal to evolve. The obdurate pursuit of power and the insatiable appetite for self-approval have created a system that, at its heart, is paranoid and brittle. By treating the people as nothing more than objects that demand a constant regime of stability maintenance, or even as enemies that must be corralled, it further drives itself into a cul-de-sac.

For well over a decade, China has seen an ostentatious kind of performance that I think of as “The Politics of the Successor Playboys.” It has been dominated by two scions of the Party nobility. First [during the ascendancy of Bo Xilai], there was a parade of comely policewomen in the cities of Dalian and in Chongqing, as well as the “Red Songs and Black Attack” movement [a neo-Maoist campaign supported by Bo, active from 2009 to 2012]. For his part, Xi Jinping has devoted considerable energy to pursuing vanity projects, like his so-called toilet revolution [to improve public bathrooms], and launching a series of policies aimed at cleaning up the country’s urban aesthetics. These include a concerted effort to demolish unsightly buildings and force low-income residents out of prime city real estate, and a raft of regulations aimed at standardizing shop signs and eliminating displeasing overhead wires and cables. Even the dead have not been spared his zeal, and farmers are now forbidden to exercise the traditional practice of burying deceased family members on their own land. So strictly do local officials enforce this ban that they seize and burn handcrafted coffins.

Then there is all the hue and cry about the “One Belt, One Road” initiative and the much-vaunted policy of eliminating extreme poverty, something that was supposedly carried out according to a predetermined timetable. All of these appear, superficially at least, to be major achievements that reflect a purportedly daring political vision. In reality, they are symptomatic of a particular brand of political willfulness; they are a modern-day version of Mao’s revolutionary romanticism. More than anything, they are smug displays of delusional hubris.

As ever-new projects and vanity policies are pursued with immoderate enthusiasm, we are actually witnessing the handiwork of an autocratic roué. The accumulated political, social, and economic bounty that was painstakingly acquired since 1978, one that carried in its wake the promise of a modicum of political evolution, has been squandered. Now we are seeing the reckless depletion of the remaining reserves of China’s reform era.

This is further proof that for a nation to play a meaningful part in the modern international world, it is insufficient to revel in possessing an almighty state with limitless political power. What is necessary is the building of a civilized society and a political system that is underpinned by a meaningful culture of law. There is no escaping the fact that nations need a form of politics grounded in a constitutional order. By that, I mean a modern constitutional framework that protects the freedom and human rights of its citizens. In the present era, this is still the best path for any truly rational society.

To advocate on behalf of such a system is not merely a self-serving and pragmatic response to historical inevitability; rather, if China is to hope for collective political salvation, it is a necessity. China and the Chinese people lack a truly resilient political system; we are instead burdened with one that, despite its formidable appearance, is inherently fragile. It is threatened to its core by every tempest.

Meanwhile, we must cope with our anxieties as best we can, holding on to what inspiration we can. Even as this age of darkness advances, I know that regardless of my benighted circumstances, my soul rises up, confident in humanity’s better future.

[Beijing, 25 July 2021]

***

Xu Zhangrun, formerly a professor of jurisprudence at Tsinghua University, is a writer who lives in Beijing. Since August 2020, he has been a non-residential Associate in Research at the Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies at Harvard University.

Geremie R. Barmé is a fellow at the Center on US–China Relations, the Asia Society, New York, and is the editor of China Heritage. His books include The Forbidden City (Wonders of the World) and An Artistic Exile: A Life of Feng Zikai (1897–1975).

***

Source:

- Xu Zhangrun, ‘Xi’s China, the Handiwork of an Autocratic Roué’, trans. G.R. Barmé, New York Review of Books, 9 August 2021

Chinese Text:

笳鼓悲鳴遣人驚

Alarms and Excursions Permit No Peace

Xu Zhangrun

許章潤

The Chinese title of Xu Zhangrun’s essay is taken from a poem by Zhang Xiaoxiang (張孝祥, 1132-1170) depicting the Tartar-Jin invasion of the Song empire. It depicts the pressing threat (‘the trumpets and drums of war’ 笳鼓) of a foreign army. ‘Alarms and excursions’, which I use here, is a well-known stage direction in Shakespeare.

I also considered a title inspired by the writings of Liang Shuming (梁漱溟, 1893-1988), who is one of Xu Zhangrun’s intellectual predecessors and heroes. ‘We have no choice but to take a stand’, is my translation of ‘吾曹不出如蒼生何’, which is adapted from the title of an early and famous essay by Liang published in October 1917. That essay contains the following well-known lines:

余以為若不辦,安得有辦法。若要辦即刻有辦法。今但決於大家之辦不辦,大家之中自吾曹始,吾曹之中必自我始。個個之人各有其我, 即必各自其我始。我今不為,而望誰為之乎。嗟乎。吾曹不出如蒼生何。

— Geremie R. Barmé

***

戊戌初春,修憲既成,三十多年所謂「改開」之政治成果,也是此一歷史時段僅有的積極政治遺產,頓失維繫,付諸東流。當此之際,中國法學界一派譁然,但止於私議,付諸嘈嘈切切,至多類似於當年蘇聯之「廚房聚會」。尤有甚者,恬不知恥奉迎拍馬之徒所在多有,此刻紛紛出籠,跪伏頌聖,醜態百出。主動被動之間,真心违心两头,了無愧怍,內心深處沒有一絲道德緊張,相反卻沾沾自喜於「遊刃有餘」,慶幸終於獲得了進言晉身之階,將這個國家政商學三界菁英階層之浅陋、自私、孱弱、猥瑣和虛偽暴露無遺,而伴隨著上下政治無恥、全民集體腐敗、群氓式狂歡的是國族規模的斯文掃地。

在此前後,宮府諭旨,層層傳達,大意謂有關此次修憲,必須一律閉嘴,不得妄議,否則重懲。法家拂士尤然,嚴禁置喙。猶記清華園裡路遇一位同仁,其久膺人大代表,憤然於修憲之輕率,慨然於倒退之荒唐,卻又以「說歸說,我到時還是要舉手的,何必撞在槍口上呢」自我解套,可謂其時一般人士之心態與身姿之普遍寫照。於是乎,人人觳簌,個個取巧,倒行逆施便在這個國族全體公民,尤其是在她的知識公民的臣民般沉默與順服中,堂而皇之地袍笏登場,而此後政情往極權老路一退再退,不知伊於胡底,乃有今日之內外不堪與困頓重重也。

2

法學家是自然之法的祭司,守衛的是基於程序正義之公義,追求的是奠基於憲政的規則之治下全體公民政治上的和平共處,於此不發一言,已然失職。而吾曹不出,奈蒼生何!於是,幾經思考,在下於是年七月發表「我們當下的恐懼與期待」一文,以萬字道憂憤,化悲情為討檄,伸公義於人間。一吐為快,大聲疾呼,既在盡士志於道之本分,更希冀引發全民思考,提醒萬眾警怵,從而捍衛以億萬人血淚苦難為代價方始幸獲之「改開成果」,阻止政治上的公然倒行逆施,防止中國陷入全面內戰,避免華夏邦國再度遭遇全球政治孤立。至於其將開罪有司,而必遭沒頂之災,早在計數之內,乃以「生死由命」慨然靜待。其後處罰接踵,逐步加重,終至去夏獠牙招展,動用專政手段斬殺思想,斷吾生計,縲紲吾身,致令章潤在自己的祖國陷入半流放半軟禁之困境。既已靜待,則雖猶如此,而在所不計,無所惜哉。

唯所痛惜者,上文所懼所盼,自戊戌、己亥、庚子而辛丑,絡繹紛呈而至,第次水落石出。所懼之事,概為八項,悉數盡現。僅僅三年,伴隨著大疫肆虐全球,極權政治日甚,曾經的寡頭共治早已蛻變為領袖獨裁,一種列寧—毛式整體主義的清洗政治。而民粹国家主义与建制国家主义交相振荡,經由酷烈整肅政治,正在愈益定型為大數據極權政治。與此同時,世界主流政治文明谱系中的除名进程已然起航,意味著曾經日漸敦睦的諸邦取消了對於中國的政治文明認證,華夏終陷四面楚歌,已成國際社會之孤家寡人,唯恃體量暫立。如此,全球反恐時代告一段落,正在進入全球反共時段。至於所盼之事,亦為八項,盡皆落空,無一兌現,讓這個多難之邦再度面臨何去何從之艱難關口。而隨著疫情減緩,危機應急式極權政治漸失優勢,民主制度的共和效能將會再顯強勁生命力,其勢顯然。

在此,順提一句,最近齊澤克氏(Slavoj Žižek)所謂世界需行「戰時共產主義」之議,病急亂投醫,無異於前門拒狼後門納虎,為極權政治捲土重來招魂,禍莫大焉!其之荒謬至極,糊塗透頂,正為癡人說夢矣。

3

究其實,此刻華夏「法日斯主義」極權政治唯以「江山」為念,無法應對「你的權力來自哪裡?」、「為什麼你有權力?」、「憑什麼你來統治?」這類關乎統治正當性與政權合法性的基本質問,更缺乏民主程序來實現權力的和平授受。一句話,無法清楚交代權源的正當性,故而最終只能落諸槍桿子之圖窮匕見。而說到底,就在於黨國專制獨裁體制逆歷史、反愛、悖政治,至此時代,早已不得人心矣。前文指陳「極權老路」,就在於既定政體其實從未超脫此徑,不過時隱時顯,或行或藏,端看形勢,而內裏極權本色從無變化,一旦渡過危機,羽翼豐滿,便本色上演也。但也正因為此,它自斷退路,以致於權焰熾烈之際反倒時刻膽戰心驚,在將全體人民視為維穩對象乃至於敵人之際,無異於將自己逼上了死路。

此間雖說訴諸花架子,演變為公子哥式治國——如重慶和大連的美女騎警巡街,如廁所革命,如唱紅打黑,如無限度強拆與「驅低」,如統一商戶招牌、整頓城市天際線、禁止農民土葬而公然搶奪焚燒壽棺,乃至於一帶一路和定期全民脫貧——凡此種種,看似雄才大略,而實為權力的任性;彷彿某種「革命浪漫主義」,而實則了無敬畏感的譫妄。總而言之,一種頤指氣使、作威作福以及心血來潮的公子哥做派也。如此造次,遂將1978年以降三代國民胼手胝足、接續奮鬥所獲之政治、社會和經濟積蓄與本來漸趨良性之國家間政治局面,幾乎揮霍殆盡,眼看快要悉數賠光了。

凡此說明,值此時代,僅僅著迷於傳統的「權勢國家與權力政治」,卻無「文明國家與文化政治」理念,萬難安穩立足世界。而其間繞不過去、堪為國族托底的是「憲政國家與憲法政治」,一種以自由和人權為幟之現代立國建政的大經大法,不妨說,此乃可見歷史時段內,有限理性的人類政治的「最終出口」。這不是基於歷史必然性的功利性自我適應,而是我們不得不進行的政治上的集體自救。而吾國吾民所缺,也是此刻政體之所以強大卻又似乎風雨飄搖之軟肋,也正在於此也。

4

三年前,拙文甫刊,英譯旋由白傑明教授推出,輾轉廣布全球。其與前後相連諸文,合共十篇,於庚子仲夏收刊於拙集《戊戌六章》,申說著一介知識公民有關這個轉折時代的痛苦思慮和無盡擔憂。其中多數篇章亦由白兄迻轉英文,凝聚的是雙方對於「中國問題」的共同深度思考,分享的是同情、友愛與對於人間不公不義遏止不住之噴薄憤慨。先賢所謂「並刀昨夜匣中鳴,燕趙悲歌最不平」,概莫即此之謂也。轉眼三載遽逝,物是人非,而文中憂懼猶然,唯情勢日甚,彷彿快到攤牌時分,卻又莫非新的黑暗世紀正在降臨,世界進入新型文明孕育期之前冥晦時光?!

歷史無語,吾人不知。唯立足當下,戒慎戒懼,勿懈勿怠,哪怕不幸身處黑暗時代,亦且永懷對於人類未來之光明心態,而孜孜護持自由之心火不滅。此所以白兄修訂重刊拙文英譯,而在下謹此略綴數言之緣由,更為普天之下熱愛自由、直面強權暴政而不屈之魂靈所惺惺相惜、宣喻於手足大眾者也!

二零二一年七月二十五日,辛丑伏月十六,於故河道旁。

***

The Refusal of One Decent Man

Xu Zhangrun, with Geremie R. Barmé, interviewed by Matt Seaton

“What I have done is to continue in a tradition long hallowed among educated individuals in China by following the dictates of my conscience to speak out against tyranny.”

— August 21, 2021

On August 9, 2021, we published “Xi’s China, the Handiwork of an Autocratic Roué,” a robust denunciation of the Chinese political system and its leadership by Xu Zhangrun that was translated for the Review by Geremie R. Barmé, a fellow at the Asia Society in New York. Despite a distinguished career as a legal commentator, scholar, and law professor at Beijing’s Tsinghua University, Xu’s record of outspoken criticism led first to his suspension and then, last year, his dismissal from his university post.

Deprived of his livelihood and forced into private life, Xu refuses to be intimidated in the face of regular interrogations and police surveillance. These conditions also mean that he is forbidden from communicating with friends or journalists, so we are indebted to Geremie Barmé for helping us compile the following portrait based on exchanges he has had with Xu over recent years.

Xu Zhangrun was born in an impoverished township in rural Anhui province in 1962. The region had recently been devastated by the famine brought about by the Great Leap Forward, Mao Zedong’s quixotic attempt to advance communism in China through a crash program of industrialization. Besides a flood that all but wiped out Xu’s town, one of his earliest memories is of an older brother’s dying from illness brought on by malnutrition.

His was a family that, though impoverished, valued education—the young Xu never even had a desk, but that did not stop him reading and studying. The family was always under a cloud, however, because Xu’s father was branded as a “class enemy” after the Communist takeover in 1949. His father was repeatedly put through the humiliations of self-criticism sessions and the like—a feature of Maoist rule—and even his children, Xu and his siblings, were subjected to similar abuse.

Mao died in 1976, and not long after, Xu’s persistence was rewarded with a place at university; he completed a master’s at a law school in Beijing and was immediately offered a teaching job in law. Following a postgraduate degree in Australia, he took up a lectureship at Tsinghua in 2000. Even after the crackdown that crushed the Tiananmen Square protests, optimism about reform in China still seemed possible in the 1990s and 2000s, as he told Barmé:

People of my generation who had experienced the violence of the Cultural Revolution era welcomed the Economic Reforms and Open Door Policy [initiated in 1978], no matter how limited their scope. We were hopeful that, starting with baby steps, the country might gradually evolve and become a constitutional democracy. We were united in the belief that a return to the capricious and totalitarian violence of the past would be a disaster.

Not only have those hopes faded, but most of Xu’s reform-minded contemporaries have fallen silent. Especially with the rise of Xi Jinping—China’s most autocratic and “personalist” ruler since Mao—many have also kowtowed to the party apparatus. “Their stance has proved to be little different from that of the imperial slave-subjects of yesteryear,” Xu writes in his essay. “It has hastened China’s lurch back into the familiar old rut of totalitarianism.”

Xu opened his account as a high-profile critic of the regime in 2016 with an essay titled “Appeal for a True Republic,” which got more than 100 million page views online.

Since then, what I have done is to continue in a tradition long hallowed among educated individuals in China by following the dictates of my conscience to speak out against tyranny. I don’t think of myself as a dissident as such; I’m more of a conscientious objector daring to confront tyranny.

By doing so, Xu rejects the notion that his work is simply “samizdat protest literature.” “My aim is not just to protest the actions of the authorities,” he explained. “I am also addressing the Chinese public as best I can. China’s reform era has long since come to an end, and I see no alternative but to take up the battle in defense of liberal humanist ideals.” Courageous as this is, Xu’s “rebellion through writing” can seem a lonely mission—and he has despaired of many of his fellow academics and legal professionals. But that is not the whole picture, he hastened to add:

As a result of the official persecution I suffered after 2019, hundreds of Tsinghua graduates issued appeals and signed petitions on my behalf, and numerous fellow academics wrote essays, poems, and even a song, in support of me and my right to enjoy freedom of expression—as theoretically protected by the Chinese constitution.

I asked Barmé what most impressed him about Xu’s stand. “When I read his July 2018 essay [a jeremiad titled “Imminent Fears, Immediate Hopes”], I was particularly interested in his criticism of what is now known as the ‘special provisioning system,’ one that showers the Party nomenklatura with coveted access to luxury goods and a raft of privileges,” Barmé explained. “I was also very much taken with his refined—and challenging—literary style, something that echoed the most important polemics from the late nineteenth century.”

It is evidently challenging to the Chinese authorities. After Xu’s recent book Ten Letters from a Year of Plague appeared, its independent Chinese publisher in New York came under pressure from Beijing to withdraw it. “The Chinese authorities even made an offer to buy back the manuscript,” Barmé told me, “an egregious instance of interfering in the internal affairs of another country.” For his part, Barmé has made Xu’s cause his own, supporting Xu’s writing through his own online platform, China Heritage:

My mentor Simon Leys’s great work, The Chairman’s New Clothes: Mao and the Cultural Revolution (1971), uses as an epigraph this ancient Chinese adage: “The refusal of one decent man outweighs the acquiescence of the multitude.” Having worked on the writings of Chinese men and women of conscience since the mid-1980s, I thought that it was important to help non-Chinese-language readers understand not only Xu Zhangrun’s message, but also the vast cultural and historical world to which it gives expression.

***

Source:

- ‘The Refusal of One Decent Man’, Xu Zhangrun, with Geremie R. Barmé, interviewed by Matt Seaton, New York Review of Books, 21 August 2021

Bertrand Russel on Meeting Lenin in 1920