Nancy Berliner & the Art of the Broken

The Inner Treasury is burnt down,

its tapestries and embroideries a heap of ashes;

All along the Street of Heaven

one treads on the bones of State officials.

內庫燒為錦繡灰,

天街踏盡公卿骨。

— translated by Lionel Giles

These lines are from The Lament of the Lady of Qin 秦婦吟 by the Tang-dynasty writer Wei Zhuang (韋莊, 836-910). Wei’s ballad is a harrowing account of the rape of Chang’an, the dynastic capital, by rebel forces. The poet would later disown the work; a bureaucrat himself he was fearful of the political repercussions of having described the decline of the ruling house with such evocative intensity. Although the lines about ‘the ashes of brocade and embroidery’ 錦繡灰 would live on in popular culture for over a millennium, the full text of the poem was not recovered until the early twentieth century.

When reviewing The Hall of Uselessness, Simon Leys’s last collection of essays, Ian Buruma observes that:

In one of Leys’s most interesting and provocative essays on Chinese culture, he tries to find an answer to an apparent paradox: why the Chinese are both obsessed with their past, specifically their five thousand years of cultural continuation, and such lax custodians of the material products of their civilization. …

[I]f even the strongest works of man cannot in the end withstand the erosion of time, what can? Leys’s answer: ‘Life-after-life was not to be found in a supernature, nor could it rely upon artefacts: man only survives in man — which means, in practical terms, in the memory of posterity, through the medium of the written word.’ As long as the word remains, Chinese civilization will continue. Sometimes memories replace great works of art. Leys mentions the legendary fourth-century calligraphy of a prose poem whose extraordinary beauty was celebrated by generation after generation of Chinese, centuries after the original work was lost. Indeed, it may never even have existed.

— Ian Buruma, The Man Who Got It Right,

New York Review of Books, 15 August 2013

In bapo 八破, ‘8 Brokens’, a long-overlooked genre of Chinese art, Nancy Berliner identified a unique moment in late-dynastic culture as well as an art form that combined the evanesce of painting with the permanence of the Chinese word. The message in this medium points to the heart of the culture and the fragile achievements of tradition.

Berliner is a writer, connoisseur, collector, art historian, curator and a specialist in Chinese folk art. Her interest in bapo, or Eight Brokens art, led to a decades-long quest to collect examples of these forgotten fragments. Over the years her friends have followed her journey and, when she mounted an exhibition of 8 Brokens art at the Museum of Fine Art Boston in 2017, they celebrated her rare achievement. At our request, Nancy has written an account of how she pieced together the story of this neglected artistic form.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

28 March 2018

Further Reading:

- Nancy Berliner, The 8 Brokens Chinese Bapo Painting, Boston: Museum of Fine Arts Boston, 2018 (forthcoming)

- China’s 8 Brokens — Puzzles of the Treasured Past, Museum of Fine Arts Boston, 17 June 2017 — 29 October 2017, curated by Nancy Berliner

- 程亚林, 沉重的“锦灰”,《书屋》, 2007年

- Wei Zhuang, The Lament of the Lady of Qin, China Heritage Annual 2017: Nanking

- 韋 莊, 秦婦吟

- Nanking Broken, China Heritage, 13 December 2017

Preface: The Eight Brokens 八破

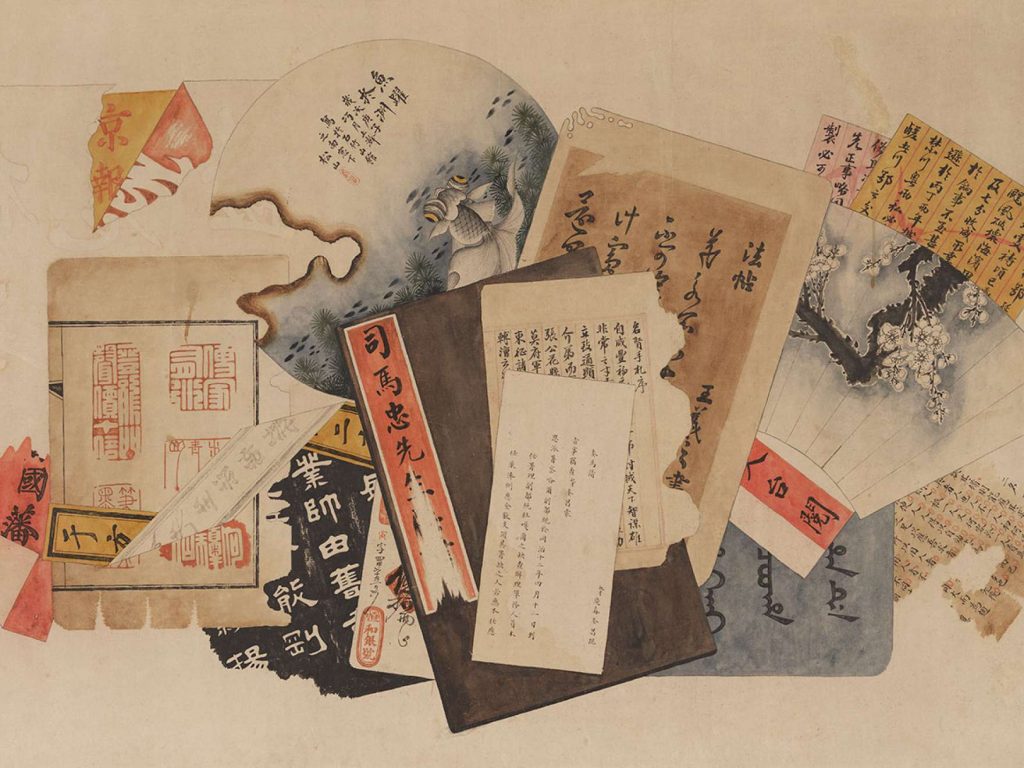

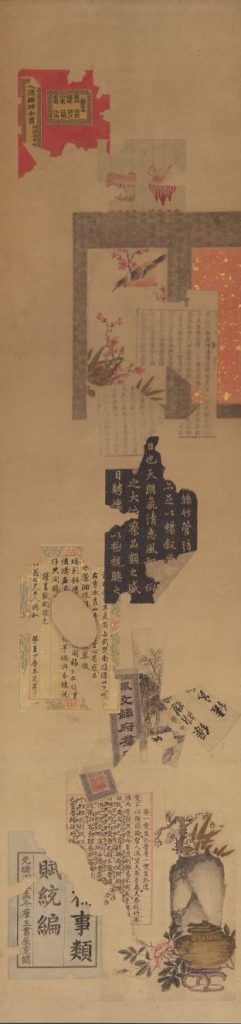

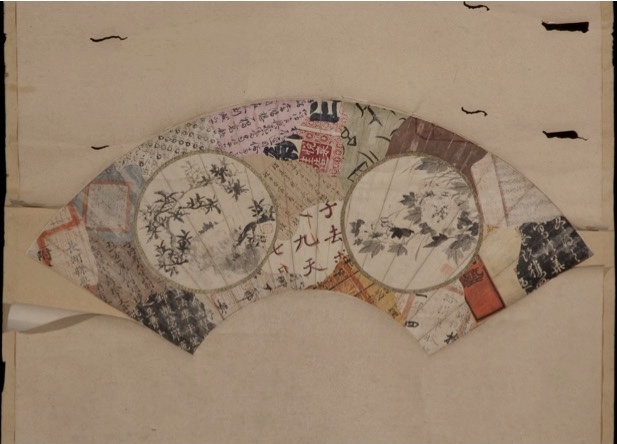

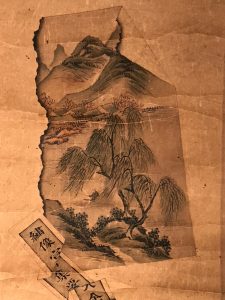

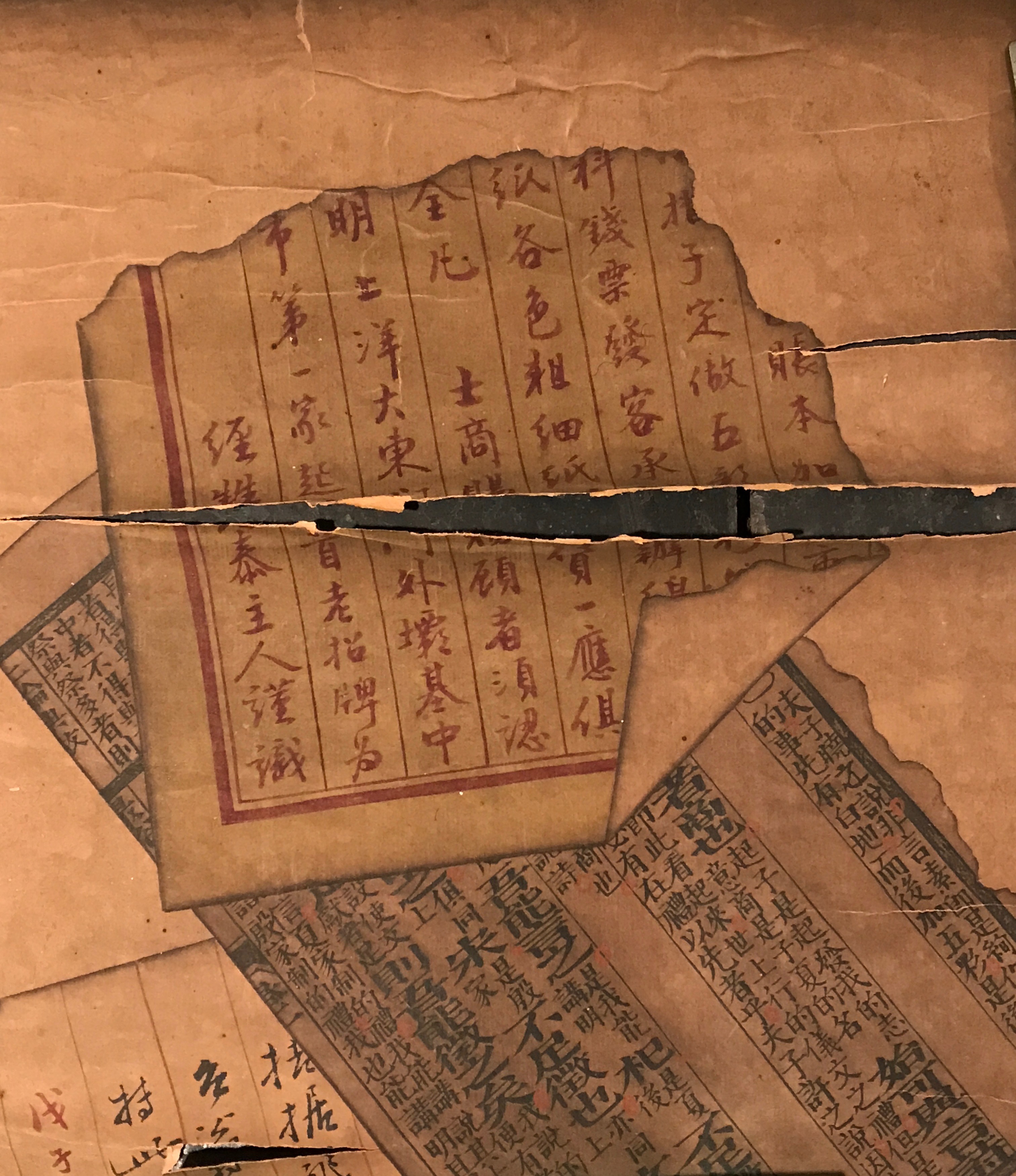

During the mid-nineteenth century, a surprising new genre of painting emerged in small and large urban centers of China. Instead of landscapes, birds and flowers, figures or traditional narratives, a number of artists began depicting, with an exacting likeness, bricolages of texts, papers and calligraphy that appeared to have been randomly tossed on the painting’s surface. Known as bapo 八破, literally ‘eight brokens’ (in this context, eight means ‘many’), or jinhuidui 錦灰堆 (‘brocade ash piles’) — they are also variously known as 百碎圖、集破、集珍、什錦屏 — these paintings shared three characteristics:

- they were meticulously painted and not, despite appearances, a collage of papers pasted on the surface of the painting;

- they depict works, or the torn remains of works, of varying cultural significance in the Chinese tradition; and,

- the material represented is ravaged: torn, burnt, worm-eaten or discarded remains of works that are shown in varying stages of disintegration.

To the contemporary eye, bapo works seem strikingly modern. It is an art form that evolved out of a confluence of several Chinese artistic traditions including:

- epigraphy, a wide-spread obsession with ancient calligraphic works;

- still-life bogu 博古 (‘multitudes of antiquities’) painting;

- the practice of creating and displaying auspicious images; and,

- the embrace of the age-old poetic motives such as huaigu 懷古 (‘yearning for the past’) and sangluan 喪亂 (‘death and destruction’).

Poems composed to mourn war-ravaged cities or palaces are a common feature of bapo art. Just as common is the use of calligraphic rubbings and pages that appear haphazardly torn from a book of poems. The term ‘brocade ash piles’ jinhuidui itself originates with a Tang-dynasty verse in which the poet records his grief upon seeing the ashes of brocade in the ruins of the women’s quarter of a palace.

— Nancy Berliner

Wu Tung Curator of Chinese Art

Museum of Fine Arts Boston

(This Preface is reproduced from Nanking Broken, China Heritage, 13 December 2017 — Ed.)

Casual Jottings On Shards of Art

碎藝隨筆

Nancy Berliner

Random scribbles in notebooks. Oddly-titled documents in old computer files. Scrambled mental images and flashes of memory. Dusty slides. Remembered conversations with old men in crumbling buildings. Snippets of information here and there.

A decades-long journey in search of a forgotten corner of art, research into a little-known history made up of fragments inevitably leaves in its wake a trail of jottings, irrelevant byways, frequently enjoyable tangents, as well as milestones and rare finds, precious jewels hidden in the befuddling dross. Chance discoveries inspire new trains of thought and discovery, leading perhaps nowhere.

Once, in my younger years, while trawling curiously through a Taiwan flea market I was arrested by an crumbly old scroll painting. Utterly puzzling, it presented a trompe-l’oeil-like depiction of deteriorating cultural treasures thrown together as if randomly tossed on the ground to create what for all intents and purposes was a haphazard composition. I bought it, but when I asked the art historians and curators I knew what it was, they shook their heads in bewilderment. Now, many years later, having finally come to some modest understanding of the history of what I now know are called bapo 八破, literally, ‘eight brokens’ paintings (among numerous other colorful appellations), I find myself sorting through my archive, remnants of the many ventures I went on as part of that drawn-out process of discovery. The residue of my studies confronts me like the jumble of objects in a bapo painting. So many individual items, each with a story of it own, all seemingly unrelated to one another. Yet, somehow, they coalesce into an integrated composition.

There was no record of bapo in the art history texts, so my investigations involved the painstaking search for physical examples of bapo work, then the seeking of advice and guidance from people who might help me on my journey after which I would follow the leads I was given allowing me to continuing stumblingly my travels through the Chinese world and through time. I wanted to understand the chronology of this art, to fix in my own mind a story of the evolution of bapo. Here, now, I will try not to be embarrassed about the bapo-like randomness of the paragraphs that follow.

***

16 March 1992

Yang Boda is the Director of the Palace Museum in Beijing. His is a widely respected position. Last year a close friend, someone sympathetic to my bapo research, was his interpreter in Paris for a week. One day, André placed a bapo painting before Director Yang in the hope that he might glean some historical understanding or insight about such works that he could then convey to me. Yang immediately admitted that he never seen such a thing before, but he promised he would look into it after returning to Beijing.

***

I met Tang Suguo 湯夙國, a Beijing traditional folk artisan, in an elevator at the Art Academy in the 1980s. His father was the renowned ‘Doughman Tang’ 麵人湯, a man who created fantastic characters from Chinese history and culture in miniature, out of coloured dough. His talent was so widely celebrated that Doughman Tang was instructed by the Office of the Imperial Household to create work for the emperor. Doughman Tang was not only an expert in Chinese folktales, he also delved into classical Chinese culture. His son followed suit and studied Tang the Elder’s refined technique while also pursuing his interest in classical Chinese scholarship. On top of this already unusual combination of elite and folk culture, Tang Suguo was also something of a rebel, and like many other young men and women in 1980s China he was fascinated by ‘the foreign’. He wore his hair long, a common Beijing fashion statement that announced that he was an ‘artist’. Given his multi-layered personality, I thought that Tang Suguo would be the ideal person to explain bapo art, something which I had come to appreciate encompassed both folk and literati culture.

‘If I were you,’ he replied to my first questions, ‘I wouldn’t waste my time on such things. I’d much rather study original Wen Zhengming calligraphy [of the Ming dynasty] or the genuine whatever, rather than bothering with these people’s half-assed copies. If they just use objects created by other people, how can we possibly call it art?’

***

I find an entry in my journal from 11 March 1993 noting that I went again to see Wang Shixiang 王世襄, the eighty-plus year-old connoisseur, collector, art historian, gourmand and an outstanding scholar of everything from gourd cricket cages 蟈蟈葫蘆 to pigeon whistles 鴿哨. He lives in a tiny courtyard home on Fangjia Yuan Alley 芳嘉園衚衕 overflowing with precious Ming-era furniture. He asked what I was up to and I told him that I was still trying to research bapo art. As usual he laughed, but he also told me that since our previous conversation on the subject he had given it some thought and that he was coming around to the idea that perhaps bapo was related, at least in its underlying concept, to jinhuidui 錦灰堆, literally ‘piles of brocade ash’ art, a style of painting that first appeared during the Yuan dynasty that generally depicted rotten vegetables and fruit peel.

I took out an article I had recently published on the subject, and my preliminary findings [see Nancy Berliner. ‘The “Eight Brokens”: Chinese Trompe-l’oeil Painting’, Orientations, vol.23, no.2 (February 1992): 61-70]. He looked at the pictures, as did his wife. She laughed and said in her charmingly direct manner that carried no personal judgment: ‘You know,’ she said, ‘to be brutally honest, I don’t like these things at all. Of course, it’s fine to do research about this stuff, and figure out what it all is, but I really don’t like it.’ She told me that she thought they reflected a vulgar, lowly stratum of society. Her dislike for bapo didn’t bother me at all. I appreciated the honesty.

Some days later, Wang Shixiang calls to tell me that a friend of his had just contacted him out of the blue asking about the origin of bapo. The man was Wen Tingkuan 溫廷寬, a historian of Chinese sculpture. He happened to be reading an article that mentioned bapo. He recalled such paintings from his youth and was determined to find out what they were and where they came from. He said that he had called everyone he knew — and even people he didn’t know — to collect information, but no one knew anything. The only written evidence he could find, Wen said, was in a dictionary of Beijing dialect 北京土語詞典. The book noted that bapo was a type of painting which included eight different type of things that were falling apart. Wen’s last resort was to contact Wang Shixiang. Wang, in turn, called me and sent me off to visit the elderly scholar.

Thrilled to have learned that there was another soul in this vast city who was intrigued by bapo, I bicycled over to Mr. Wen’s home and after he invited me in to his small apartment I told him all I knew about bapo. As we chatted, he began talking about his life and his own collecting habits, so I asked if I could see some of his collection. He pulled out his box of ceramics.

There was the base of a Ming blue-and-white bowl with a drawing of two children playing. A five-inch-long chunk of a Song dynasty Cizhou vase that he said cost him two silver dollars. Then there was a small pink Qianlong-era enamel cup, with turquoise glaze on the inside, and a large chip off the edge. He had had a special display box made for this cup. Under the cabinet was a Qin-dynasty tile with a small inscription on it. And tucked far in the back of a cabinet, which he promised to show me next time, was a Shang Anyang bronze jue 爵 ritual vessel. It was cracked and missing a small piece, but nonetheless it was an excellent example, he said. And as he picked through the box, he kept mumbling ‘Oh, Wang Shixiang has real treasures, these are just junk.’ And indeed they were just broken bits of pottery; but they were his treasures.

He had collected all of these objects over forty years ago and had kept them safe all this time. It was moving to see how he cared for these treasures. For him each one had a story and its own special artistic value. And so what if they were broken? In its own way, bapo was alive and well in China.

I run into Tang Suguo again. He recalled that when he was a child his father called anything broken, like their clothing when it frayed and fell apart, ‘bapo’.

12 March 1992

I spend the morning with the scholar Zhu Jiajin [朱家溍]. He can look at the disparate ‘broken images’ in bapo paintings — the old books, the calligraphy and the ephemera — and tell me exactly what each one is. He studies a cigarette card pictured in one painting — small colorfully illustrated souvenir cards that came in cigarette packages in the early twentieth century — and he identifies the cigarette company that published this particular kind of card. He does all of this as he is puffing away on his own cigarette. He says he collected cards like that when he was young.

***

I visit Director Yang in his office at the Palace. We sit drinking tea in over-stuffed chairs. As promised, after returning to Beijing from Paris, he had asked around about bapo. Most people had had no idea about or memory of the art form but, one old man — a researcher in the Bronze Department — said he had a vague memory of it. Give me time, he said. Several days later, the old man came to see the Director and told him he remembered someone he had known many decades ago, a person long since passed away, who had specialized in painting bapo. He made a living out of his work, but over time the market for this kind of art had dried up and he had to find a new line of work. He ended up as a registrar in an antique store, recording newly acquired objects. Now, couldn’t he hang up his paintings and sell them in the shop?, Yang had asked. No, said the man, his boss thought that broken objects like that brought bad luck. The elderly bronze researcher died two months after sharing his memories with Yang. No one else in the Palace could offer any information about bapo. We only deal with imperial objects here, Yang told me, no one would ever bring us anything like that. He urged me to go around as quickly as possible and talk to as many little old men as I could find, Old Peking People 老北京, as they are called: go to the Central Art Academy, to the Arts and Crafts Academy, he said, and see what they might have to tell me.

***

Zhu Shuyi was a senior curator specialising in jade and the decorative arts at the Shanghai Museum. We had met when she first came to America with the then director of the museum in the 1980s. Years later, when I knew her better, she told me about her experiences during the Cultural Revolution. She was working at the Shanghai Museum during the years when owning old and valuable objects was not socially or politically acceptable. Many people had rushed to donate their collections to the Museum. Zhu Shuyi’s job was to review the proposed donations and decide which of them would be appropriate for the museum’s collection. Did anyone bring in any bapo paintings?, I asked. Oh, yes, she said, ‘but we would never accept anything as common as bapo. I told them to take their paintings away.’

***

It was 1993. I went to a friend’s home for dinner. They were not part of the art world so I never thought of mentioning my obsession with bapo. But, that night, she asked what subject I was pursuing in Beijing lately and I told her ‘late-nineteenth century and early twentieth century painting’. She wasn’t satisfied with that and in the end I had to give her a long and detailed explanation about bapo, a subject she’d never heard about and something she could barely conceptualize or picture in her mind. She said the only thing it reminded her of was — she laughed as she said this — a fabric design that was popular in the fifties: a white background with images of broken vases and pots. A classmate of hers had made a shirt out of some of that material and it struck her as the oddest thing. Who would wear broken pots and ceramics? She had thought it so bizarre that she even remembered discussing it with her mother. ‘I’m sure even my mother remembers that fabric. Isn’t it odd what images ours memories hold on to?’ As we were talking, her son walked in. He said he remembered the fabric, too. ‘They had a tablecloth made of it in the home of a classmate of mine,’ he offered. My friend asked if these broken pot images were the same as the broken works of calligraphy and torn paintings in bapo?

10 May 1992

I strolled through the Tianjin flea market, a place where I had occasionally come across bapo paintings. Among all the random odds and ends people had brought out to sell, I found a large, though crumbling, bapo painting. It was on cheap paper and also mounted on paper, torn and falling off its wooden scroll end. In the taxi I took from the flea market the driver remarked that the painting I’d bought was in a pretty bad state. ‘What are you going to do with it?’, he asked. I told him I had a friend who mounted pictures and that I’d ask him to remount it. ‘But’, the driver said, ‘I see someone’s burned a hole right through it in one place, how can you fix that?’ I explained that hole was painted on to look like it was burned. ‘That was painted on?’ I don’t think he believed me.

***

Yang Boda and I had been sitting in the museum’s reception room for foreigners and chatting for two hours about the bapo problem. He had studied each one of the photocopies of made of my collection slowly and carefully. ‘These are precious materials,’ he kept saying as he pointed to the papers. ‘I’ve never seen any of this before, so this is a rare opportunity.’ He poured us some tea.

Yang, who had lived through all the vicissitudes of modern Chinese history, began musing about cycles in history. ‘Sometimes,’ he said, ‘beauty is too perfect.’ (The expression he used was wanmei 完美; it is made up of the two words: ‘complete’ 完 and ‘beauty’ 美 — something akin to ‘the extreme of beauty’, or ‘beauty perfected’.) ‘When we reach the extremes,’ he continued, ‘we have to turn back and make things flawed in some manner. So instead of perfect old calligraphic works or stone or bronze rubbings, we have defective ones, things that are in decay, falling apart. That too is an aesthetic, a type of beauty, in itself. The beauty of the imperfect.’

17 March

Over the years, the flea market and the state-owned antique shops in Tianjin had yielded numerous bapo paintings. I returned over and again to see what might rise to the surface. I had taken the train from Beijing to Tianjin that day hoping to find more bapo works, but mostly hoping that Ms. Yu Shuying, the manager of one of the state-owned antique stores, would introduce me to her master. Last year, she had said that he might know something about bapo, but he had been unavailable as he was in hospital. I rang up the antique store after I’d settled in to my hotel. They told me Yu Shuying had just returned from overseas and wouldn’t be coming in for a while. Damn! I went anyway to see if I could find her. No amount of pleading would persuade her workmates to call her in and, the more I insisted, the more resistant they became, daresay suspicious as to why a foreigner wanted to contact her. By the time I left, I was furious with frustration.

I dragged myself off to another antique store. The woman in charge of paintings there took out some pictures of rocks that she had put aside for me, but said she didn’t have any bapo. Then she broke my heart: she had sold one only two weeks earlier.

There was one other antique store in Tianjin. When I had gone there the previous year, the master had said that he remembered that somewhere back in storage there was a set of four bapo works, but he didn’t know exactly where. Come back next year, he said. When I find them, I’ll hold on to them for you. So I made my way to his shop in high hopes that he had kept his promise. There he was, a Mr. Chen. He took a while to remember me, but eventually he did and, yes, he did remember that there was a set of four, but no, he had never located them. Maybe you could look, now, I suggested. He sent a young man off into the storage room. We sat making small talk for fifteen minutes. Finally, the young man emerged from the back room. He hadn’t found anything. Again, the old man said, when we find them I’ll definitely keep them for you. I urged them to look again, now: please check all the cabinets. After a little bit more coaxing, he went back again. I felt he was just shuffling paintings around and not really trying, but I knew I couldn’t insist any further. Another fifteen minutes passed: tea, chat and flipping through a stack of paintings on fans. Finally, the younger man emerged from the storeroom. ‘You’re in luck today.’ He was holding four scrolls. They were beat up, but they were bapo and done by the same artist as another fan painting I had bought seven years ago in Xi’an in far off Shaanxi province. Yay! A small triumph in my little pursuit.

***

Xiao Zhu is a mounter of paintings; it’s a skill he learned from his father, and as a mounter he comes across all kinds of work. Over the years he’s mounted many of the tattered remains of bapo art that I scrounged up in flea markets and, once he had come to understand my ‘mission’, he helped me tremendously. In addition to finding bapo paintings for me, he also introduced me to older people in the trade. One of them was a man named Cao who worked at the Palace Museum. Cao’s theory was that objects were depicted in a broken state, in bapo, because to be complete is, according to popular Chinese belief, unlucky. Being complete or whole means that an object has reached its end. For instance, he said, there is a story that when the palace in Beijng was constructed it only had 9999.5 rooms, rather than a full 10,000. To have built 10,000 would have meant, symbolically, that the dynasty was complete, whole and so finished – daotou 到頭, he added: it had reached its end.

***

Lao Tian was around my age. He was the privileged son of an important official who spent his days pursuing his own scholarly research. He said he had a friend at Rongbao Zhai 榮寶齋, the main state-owned painting and painting supply store at Liulichang 琉璃廠, the pre-revolutionary antique market neighborhood in Beijing. The friend had been in charge of acquiring old paintings for years, and, Tian said, he might have heard about bapo. Tian set up a meeting. Many children of high cadres dress in Western suits and leather shoes, but Tian always impressed me because he wore faded, worn out sweaters, and baggy Chinese trousers. His friend at Rongbao Zhai was of a similar ilk. I didn’t notice his clothes, but his shoes — black with hand-sewn cotton soles 千層底布鞋 — immediately caught my eye. They were the kind old men wear, but Tian’s friend, Sa, was no more than forty. With his scruffy old shoes, he was a little bapo himself.

We sat down on the stuffed chairs in a room reserved for visitors. Sa said had seen many bapo but had never acquired any for the shop. The state, he said, only recognised big names, so they would never take in that kind of picture. Still, he had agreed to meet me because he was curious to learn that someone was interested in such art. Sa said he had never studied bapo and so anything he said was not to be taken as fact. Nonetheless, he had been giving it some thought. He said it is best to look not just at the development of a single style but to consider what else was going on at the time. He had been pondering this when he had walked into the room we were now sitting. He indicated the set of four vertical wooden plaques hanging on the wall. Each of these featured an arrangement of shapes — a vase, a cup, a pomegranate — cut out of the wood. The empty spaces had then been fitted with glazed purple and turquoise Jun-ware-style porcelain. They were probably the remains of badly broken Song dynasty ceramics. Looking at the plaques my mind filled with bapo parallels. The treasuring of broken antiquities.

***

Chengxiang had been mounting my crumbling bapo paintings for years and knew I was interested in gleaning tidbits about bapo history. He joined in the hunt and put out feelers among his friends. One day, in 1992, he reported that a friend had seen a contemporary bapo painting in a shop window at Liulichang. After a bit more digging, we learned that the painting was being sold by a certain Mr. Kou. But Mr. Kou declined to meet me and refused to share the name and location of the artist who’d made the painting. The only information the friend could squeeze out of the illusive Mr. Kou was that the artist was in Hebei Province.

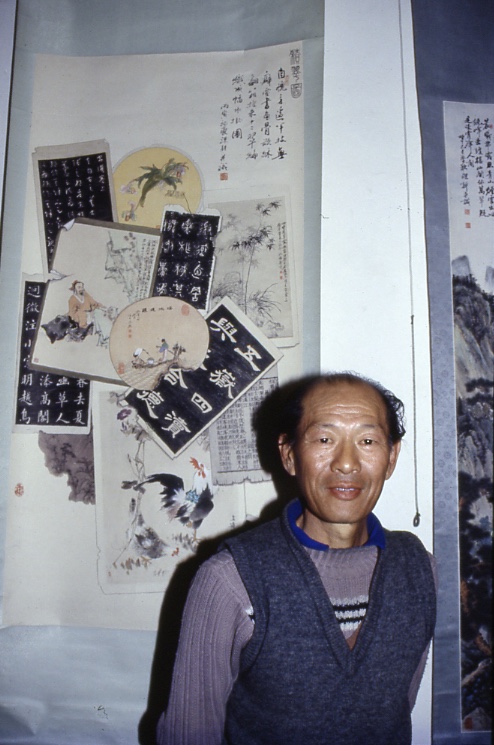

As ludicrous as it might sound, determined to outwit the evasive Mr. Kou, Chengxiang and I decided to try tracking down the unnamed artist. We packed a small travel kit, as well as a camera, some film and cash, and took a train south to Dezhou where we rented a car and started hopping from town to town. The landscape was featureless: flat and desiccated, with no distinctive architecture. In each county, we stopped in at the local cultural bureau and began explaining bapo and our quest. There were insisted-upon viewings of local painting exhibitions, and many cups of tea. But eventually we would be sent on to the next county. On the third day, the scent started getting stronger. Someone had heard of such an artist. Driving, down dirt roads, into towns, out of towns, somehow eventually a cultural officer directed us to a basic, low 90s-era cement apartment building in a small county town, and there on the first floor was a thin, ruffled man with bapo paintings hanging on the wall. Yang Renying. I was nervous, slightly uncomfortable — what was I doing here? — yet elated. A living bapo artist.

***

6 November 1992

In Shanghai. Dai Jiahua, a mounter at the Shanghai Museum has promised to take me to see the eighty-three year old artist Tang Yun [唐雲; there’s now a museum dedicated to him on the southeast shore of at Changqiao on West Lake 西湖長橋 — Ed.]. He tells me that Tang has an impressive private art collection. He is particularly interested in work by Ba Da Shanren [八大山人、朱耷] and the Eight Eccentrics of Yangzhou 揚州八怪. He also collects Yixing-ware 宜興 teapots, some of which, the mounter notes, are now worth hundreds of thousands of yuan. The old artist is also a tea fanatic and only drinks tea from Hangzhou that costs 300 yuan a pound. He has spring water flown in for making tea and has bought four apartments in this new apartment complex. Tang is a generous man, the mounter adds; he donated 50,000 yuan to victims of the Anhui floods the previous year. He also made a present of several extremely expensive tea pots to my friend, one of which he accidentally broke.

Tang Yun’s apartment looks unremarkable, but the walls are covered with paintings by major artists. There’s a Lin Fengmian 林風眠, a Shitao 石濤, as well as calligraphy by Zheng Banqiao 鄭板橋. He offers me tea from an exquisite Yixing pot made in the shape of bracket fungus 靈芝. We chat for a bit before I ask him about the Republican-era Chinese Artists’ Association 中國畫會. He was one of the only two surviving members. I had read that a bapo artist by the name of Yang Weiquan 楊謂泉, who was working in Shanghai in the 1930s, was also a member. The association, Tang Yun explained, included about one hundred artists, but not just anyone could join. They had standards. Yes, he remembered hearing the name Yang Weiquan, but he did not belong to his group. I showed him one of Yang’s bapo paintings.Tang said they called such work dafan zizhilou 打翻字紙簍 (a turned over basket of papers with writing on them), but no one in his group would have painted such things. It was merely gongyipin 工藝品, a kind of handicraft, he remarked with disdain.

A few days later, I went to the Shanghai Library which was then still housed in the grand but now musty old building of the Shanghai Race Club. Unbelievably, the librarians were able to locate a booklet, published in 1937, listing members of the Chinese Artists’ Association. It included Yang Weiquan, age fifty-two, from Minhou county in Fujian province. It even provided an address, #142 Huajin Pailou [華錦牌樓].

14 April 1992

An Australian friend had suggested I contact the writer and journalist Sang Ye 桑曄. When we met at the arranged spot in front of the China Art Gallery [中國美術館] in Beijing he tells me that he thought we were meeting because I was researching missionaries in China. After a few minutes of confused conversation, we discovered that we share a totally irrelevant hobby: scrounging around in mounds of refuse and flea markets in search of the remnants of past lives, old customs and dated fashions.

I learn that a decade earlier Sang Ye had been obsessed with collecting paintings with religious or superstitious themes. His current passion is objects related to the Cultural Revolution. He has amassed over 7,000 different Mao badges, not to mention a collection of enamel cups featuring Mao’s poetry as well as such things as cabinets with Mao poems carved into the mirrors. His heart is now set on acquiring a Cultural Revolution rug with Mao’s portrait on it, for which the rug company is asking $100,000.

Sang Ye’s garbage-foraging has led him to collect numerous stacks of various items. When I tell him that I am pursuing research on bapo painting, and pull out some photographs of the paintings, I discover that he knows this kind of art. He says he occasionally came across such work in junk stores and elsewhere, but that he had never paid much attention to it. But he has a phenomenal memory and he is soon coming up with numerous little details and facts for me. He recalls that he had seen a number of bapo paintings at the Capital Library 首都圖書館 [next to Beihai Park in central Beijing] years ago. He had asked people there what they were doing in the library, but no one seemed to have a clue, apart from the fact that they seemed to be related to books in some way. He also recommended I visit the prolific essayist Zheng Yimei 鄭逸梅, a ninety-plus year old man in Shanghai. He was sure would know about za bacou 雜八凑 [‘a gathering of the eight miscellaneous things’] (another one of those various colorful names for bapo). I eventually made it to Shanghai but was devastated to learn that Zheng Yimei had died the previous month at the age of ninety-eight. (I later learned that he had indeed written a number of essays related to bapo, included in Selected Writings of Zheng Yimei 鄭逸梅選集.)

2017

Every few days over the past several months I have repeatedly gone to my basement and sifted through piles of papers in a cardboard box labeled ‘BAPO’ searching for a scrap that I had came across maybe two years earlier. The box held random odds and ends related to my research, photocopies as well as various notes that I had tossed in over the years for safekeeping. The little piece of paper that I had come across a couple of years ago was a short letter that dear Wang Shixiang had sent to me in the 1980s about the relationship between bapo and the expression jinhuidui 錦灰堆, ‘piles of brocade ashes’.

Jinhuidui is a term used mostly in the Jiangnan area for bapo paintings but Wang Shixiang had been looking into the term and its origins. The Yuan dynasty artist Qian Xuan [錢選] had used the expression as the title of a painting, one that was no longer extant. Qian himself had probably adopted the term from a mournful Tang-dynasty poem [see Wei Zhuang’s The Lament of the Lady of Qin in the Editorial Introduction above].

Wang Shixiang became so enamored with the phrase that he used it as the title of his last book, a three-volume selection of his essays [錦灰堆: 王世襄自選集, 2001]. I had been deeply touched when, a couple of years ago, I had rediscovered his more-than-twenty-year old note. This was indeed one of those precious, meaningful snippets of words upon a paper that is part of my own virtual bapo work. I can’t find it just now; it is among my own piles of ashes, waiting to be rescued.

— January 2018

***

- I am deeply indebted to Geremie Barmé of China Heritage for his constant inspiration, for encouraging me to gather together these imperfect memories and diverse notes, and for his confidence that they would make a meaningful whole. — The Author

Note:

As Zheng Yimei comments in Curious Stories and Elegant Distractions 珍聞與雅玩:

無論一頁舊書,半張殘貼,以及公文、私札、廢契、短簡,任何東西都可以臨摹逼真,畫成縑幅… …把這些東西加以錯綜組織,有正有反、有半截、有折角,或似燼餘、或如揉皺,充分表現藝術意味,耐人欣賞。