The Other China

禽獸食祿

In my twenties, my circle of friends referred to the synchronised annual meetings of China’s pro forma legislative bodies in Beijing as ‘The Walking-Stick People’s Congress’ 拐杖人大 and ‘The Wheel-chair Consultative Congress’ 輪椅政協. This was because the membership of both bodies was politically ossified and those who participated in the stuffy ritualised events were predominantly agèd and frail. But, after decades of persecution at the hands of Mao and his henchmen, the enfeebled and crippled vied to attend the vainglorious gatherings even if they could only do so with assistance. Although delegates to what is now known as the ‘Two Sessions’ 兩會 in 2023 are physically more sprightly, judging from the inelasticity of their public statements, they are intoxicated by the Fountain of Senescence.

My first People’s Congress was convened with great fanfare in January 1975. Having recently started studying at Fudan University in Shanghai I was struck by the large hand-written slogans and posters festooned throughout the campus celebrating the event. Mao Zedong himself was in the chair and our school’s loudspeaker system crackled with news of the proceeding morning, noon and night.

It was at that Fourth National People’s Congress that Deng Xiaoping was made the de facto head of government (Zhou Enlai was ailing and Deng was named ‘First Vice-Premier’) and a program to pursue the Four Modernisations of agriculture, industry, national defense, as well as science and technology, was announced. This lofty goal was, however, drowned out by shrill exhortations to pursue tirelessly the Cultural Revolution and the Anti-Lin Biao Anti-Confucius campaign and strive for ever-greater accomplishments under the guidance of Mao Zedong Thought.

At that time, there was no parallel meeting of the National People’s Political Consultative Congress. It had been suspended in 1966 and would not be revived until 1978. Thereafter, friends in Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou and Hong Kong were always able to ferret out risible delights in the rhetorical stodge of the annual Two Sessions. Today both in- and outside China, industrial amounts of verbiage are churned out as pundits of all kinds read the entrails offered up in Beijing. But, back in the day, they were an occasion for shared jokes and poetic mockery.

Shortly after Mao’s death and the fall of the Gang of Four I had been embraced by members of Layabouts Lodge 二流堂 Èrlíu Táng, a loose salon of literary figures who, having survived decades of persecution, could once more enjoy getting together to eat, drink and gossip. The Lodge was a shadow of its past self, and I was only ever a gadfly at gatherings of the remaining members, but I amused them enough to be included and they had a profound influence on me.

It was in early 1978 that the most notorious moment in the short history of the recently resuscitated National People’s Political Consultative Congress was itself being discussed, although sotto voce. The scuttlebutt was prompted both the publication of the Selected Works of Mao Zedong Volume Five the previous year, which contained Criticism of Liang Shuming’s Reactionary Ideas, and the sudden reappearance of Liang himself after a hiatus of a quarter of a century.

In September 1953, Liang Shuming (梁漱溟, 1893-1988), the modern Confucian thinker and rural reformer, had famously clashed with Mao. Liang was mildly critical of how, following the Liberation of 1949, Party policy favoured the urban working class to the disadvantage of the countryside. Until then, Mao had regarded Liang as a zhèngyǒu 諍友, ‘a principled friend who dares to disagree’. Liang now took it upon himself to speak truth to power. During a heated exchange at a meeting of the Central People’s Government Council power spoke back. In response to a series of biting remarks that Mao directed at the scholar, Liang asked the Party Chairman if he had the ‘magnanimity’ 雅量 yǎliàng to allow him now to voice his views at length. Mao famously replied:

‘I very much doubt that I’ll indulge you with the kind of magnanimity that you want!’

您要的這個雅量,我大概是不會給的!

Mao did, however, say that he’d be magnanimous enough to allow Liang a seat on the National Consultative Congress; he wouldn’t even have to perform a ritual self-criticism. But, Mao added, ‘The only thing that you have coming your way is denunciation [批判].’ Subsequently, the Party Chairman published a scathing attack on the scholar who, having been thus dismissed, only resurfaced because he had managed to outlive his nemesis.

In 1978, this was now rich material for members of Layabouts Lodge.

For years thereafter, I frequently acted as a ‘poetry mule’ when Yang Xianyi 楊憲益, Huang Miaozi 黃苗子, Wu Zuguang 吳祖光, and sometimes other aficionados of the defunct Layabouts Lodge exchanged the doggerel verse — 打油詩 dǎyóu shī — that they composed which made light of the portentous events of the day. Without ready access to telephones until the mid 1980s and, despite the fact that the Beijing postal service was highly efficient, my elders enjoyed having an eager, bike-riding ‘foreign friend’ hand deliver their slightly subversive compositions in person, collect updates and deliver good-humoured ripostes. (Those familiar with the layout of Beijing will appreciate my itinerary — from Xianyi’s apartment at the Foreign Languages Press at Baiwanzhuang in the west, to Zuguang’s place at Dongdaqiao in the east and then on to Miaozi’s place — he and his artist wife Yu Feng 郁風 originally lived in a cramped courtyard at Dongjiaominxiang in the old city before moving to a state-allocated apartment at Tuanjiehu further to the east than Zuguang.)

It was part of an ancient tradition among men and women of letters; it was also, in more ways than one, an education.

[Note: See also Poetic Justice — a protest in verse, 5 April 2019.]

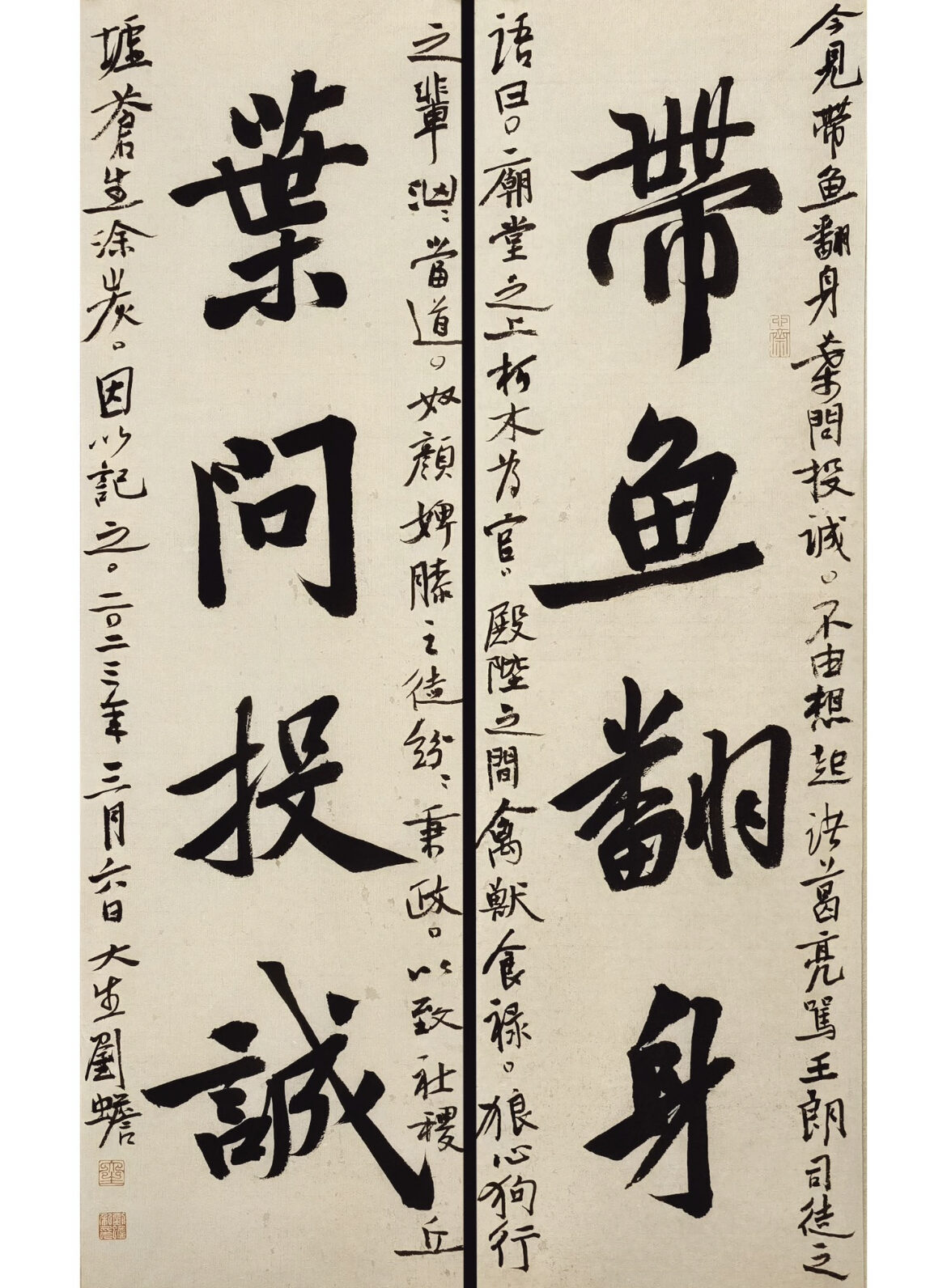

As the annual Two Sessions shifted into stilted action in early March 2023, I was reminded of those youthful adventures by Liu Chan, calligrapher, editor and essayist. Liu published a couplet mocking two new members of China’s legislative bodies in his inimitable calligraphic style and a colophon in which he quoted a well-known passage from The Romance of the Three Kingdoms. I somehow think that it would have amused the members of Layabouts Lodge. Zuguang and Miaozi may well have been inspired to compose replies and Xianyi would definitely have invited Liu Chan to join him and Gladys for a meal followed by a night of drinking and mischievous conversation.

[Note: Xianyi celebrated his own appointment to the Political Congress observing wryly that the next time they decided to arrest him — he had been jailed for four years during the Cultural Revolution — at least they would have to convene a meeting and go through a formal process of sorts.]

***

This chapter in The Other China is fondly dedicated to the memory of Yang Xianyi, Huang Miaozi and Wu Zuguang.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

7 March 2023

***

On the ‘Two Sessions’ in Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium:

- 你儂我儂 — ‘It’s all ruined by the politics’, 5 March 2023

- 萬變不離其宗 — The Harry Houdini of Marxist-Leninist regimes; the David Copperfield of Communism; the Criss Angel of autocracy, 6 March 2023

- 白茫茫一片真乾淨 — A Landslide Victory Marking the End of the Beginning, 10 March 2023

- 鴨架湯 — It’s Time for Another Serving of Peking Duck Soup, 12 March 2023

The Beltfish is Back

&

Ip Man Bends a Knee

Liu Chan 劉蟾

Upon learning that ‘Beltfish Zhou’ had found favour once more and that Ip Man had further demonstrated his loyalty, a passage from the speech that Zhuge Liang addressed to Wang Lang came to mind:

‘The court is replete with noxious officials and sycophants feed like rabid beasts. Men with hearts of wolves and the demeanor of curs crowd the scene while craven, servile knaves hold office. The sacred shrines of state are reduced to ruins and the common people are desperate.’

廟堂之上,朽木為官,殿陛之間,禽獸食祿;狼心狗行之輩,滾滾當道,奴顏婢膝之徒,紛紛秉政。以致社稷丘墟,蒼生塗炭。

I decided to record my response here.

Dasheng Liu Chan

6 March 2023

[Note: The full text of Zhuge Liang’s speech appears in Chapter Ninety-three of Romance of the Three Kingdoms 《三國演義》第九十三回 · 武鄉侯罵死王朗。]

***

***

Beltfish Zhou 周帶魚

Readers of China Heritage last encountered Zhou Xiaoping (周小平, 1981-), aka ‘Beltfish Zhou’, in 2017 when, in a footnote to an article on the craze for nationalist Hanfu fashions, we noted that:

On 15 March 2017, to great online fanfare Zhou Xiaoping 周小平, a man derided in the non-official media as party-state leader Xi Jinping’s Internet courtier (in October 2014, Xi had extolled Wang’s online logorrhoea as representing pro-Party ‘positive energy’ 正能量), announced his marriage to Wang Fang 王芳, a popular songstress known for cloying renditions of revolutionary songs 紅歌. The nuptials featured a pastiche ceremony and pictures emerged of the couple swaddled in Hanfu costume.

— from China’s State of Warring Styles, 27 March 2017

As a result of an essay titled A Sunshine Boy for the Mother Country 我待祖國如暖男, something akin to being a manifesto promoting simple-minded cultural nationalism, Zhou was known as ‘Sunshine Boy’ and the term 暖男 nuǎnnán gained online currency.

[Note: See David Bandurski, Zhou Xiaoping, “sunshine Boy”, China Media Project, 24 October 2014.]

Not everyone was suffused with fuzzy feelings when they thought of this latter-day Lei Feng. After he defamed a seafood producer in print and refused to recant for having spread malicious misinformation about them, his detractors dubbed him ‘Beltfish Zhou’ 周帶魚. For his part, Sunshine Boy blamed the incident on ‘pernicious foreign forces’ beholden to Falungong.

Online controversies and real world scandals have dogged Zhou’s multifaceted career and he had all but disappeared from sight until his sudden elevation to the National People’s Political Consultative Congress in early 2023. As a dual representative of the Communist Youth League and the All-China Youth Federation Zhou declared that he would be a ‘legislative fiend’ 提案狂魔 tí àn kuáng mó and he immediately set to work making a series of preposterous submissions to the Congress.

With a finely honed sense of cynicism, and knowing full well that submissions tabled at the NPPCC are logged but never seriously discussed, let alone passed on for meaningful deliberation or action, Zhou issued a call for laws that would legalise the assassination of Taiwanese politicians and cultural activists. The aging Xi-era Wunderkind cannily uses his role as patriotic play-actor to generate ever-new political and business opportunities.

[Note: In his calligraphic epithet, Liu Chan refers to Zhou’s re-elevation as 翻身 fān shēn — to be emancipated, turn over or make a comeback. In the Land Reform era of the late 1940s and early 1950s, the term 翻身 fān shēn was used by the Communists to describe the (short-livesd) ‘emancipation of the peasants’. Readers of a certain vintage will be familiar with the expression since it featured in the title of William Hinton’s influential 1966 book Fanshen: A Documentary of Revolution in a Chinese Village. In Liu Chan, 翻身 fān shēn has a double meaning: Zhou has reappeared and/ or the Party-as-chef has flipped the beltfish in the frying pan.]

***

Ip Man, a wolf warrior avant la lettre

Ip Man (aka Yip Man 葉問, 1893-1972) was a celebrated martial artist, grandmaster of the Wingchun School 詠春拳 and the teacher of Bruce Lee. His life inspired a series of kungfu movies (2008-2019) starring Donnie Yen Ji-dan (甄子丹, 1963-).

The real life Ip Man was know for resolute resistance and, like the vast majority of his fellows, for choosing to live in colonial Hong Kong rather than in Mao’s China. Here Liu Chan skewers Donnie Yen’s ‘Ipso Man’ by using the term 投誠 tóu chéng, ‘willing submit to the enemy’, pointing out thereby his betrayal of Hong Kong.

[Note: See To Kit’s comments in Ip Man 好 Man 呀!甄子丹鬧場哄動美中港, 風雲谷: 236, YouTube, 11 March 2023.]

Known for his pro-China stance — he described the 2019-2020 Hong Kong Protest Movement as ‘riots’ — Donnie Yen was elected to the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference in 2023. As a representative of the ‘Literature and Arts’ sector he replaced Jackie Chan 成龍, a fellow Hong Kong action star and odious pro-Beijing lickspittle.

Responding to questions from journalists during the ‘Two Sessions’ Yen declared that he consistently used his film work to ‘tell The China Story well.”

Yen has a role in John Wick: Chapter 4 and he was also invited to be a presenter at the 95th Academy Awards in Los Angeles. This led to a letter of protest being sent to the ceremony’s organisers which read in part:

‘We are deeply concerned about your decision to invite an actor (Donnie Yen) who supports human rights violations to be a presenter at the Academy Awards. As a globally renowned film award, the Oscars should represent respect for human rights and moral values, not support for oppression and human rights abuses.’

The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences ignored the protest and Yen duly introduced a performance of best song nominee ‘This is a Life’ by Stephanie Hsu and David Byrne from the film Everything Everywhere All at Once at the Academy Awards ceremony on 12 March 2023.