Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium

Chapter XXIII, Part II

忘卻的紀念

It is five years since we announced the launching of China Heritage at the end of a speech titled Living with Xi Dada’s China — Making Choices and Cutting Deals and published A Monkey King’s Journey to the East, the inaugural article in our online journal. It is also ten years since the irresistible rise of Xi Jinping.

We marked 1 January 2022 — the beginning of the end of Xi Jinping’s first decennary as head of China’s party-state-army — by launching Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium, a series written and published online in the Wairarapa, on the southern tip of Te Ika-a-Māui, the North Island of Aotearoa New Zealand. (See ‘Ugh, here we are’, in China’s Highly Consequential Political Silly Season, Part II, 14 October 2022.)

***

In The True Face of Mount Lu, the preface to Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium, we ascended Mount Lu, or Lu Shan, the Hermitage Mountain, in Jiangxi 江西省廬山.

One of China’s most famous mountains, and a modern national park, Mount Lu has inspired poets, scholars, recluses, religious devotees over the ages. In the twentieth century the hill station at Guling provided both escape from the summer heat as well as a political platform for leaders both of the Nationalists and the Communists. During the era of High Socialism in the People’s Republic of China (c. 1949-1978) Mount Lu was the stage for the rise and the fall of the the most extreme policies of Mao Zedong and his co-conspirators, as well as for Mao’s cult of personality.

The complex terrain and numerous peaks of Mount Lu provide many perspectives both on the mountains themselves and the landscape surrounding it. Mount Lu frustrates the ambitious who hope to gain an all-encompassing perspective; these heights provide no olympian vantage point from which to survey or dominate the world. Rather, Mount Lu offers beguiling viewpoints and multiple angles from which to contemplate the passing cavalcade of history. It is for this reason that we offered a meditation on The True Face of Mount Lu as the prologue to China Heritage Annual 2022.

***

‘Chinese Time — the struggle of memory against forgetting’ begins with a consideration of Chinese Time. This is followed by a quotation from Xi Jinping’s late-December 2022 warning to members of the Chinese Communist Party to stay ‘on message’ and a famous essay by Deng Tuo on Mao Zedong’s ‘amnesia’.

‘Take it from me, we are losing the war because we can salute too well’ by Li Chengpeng is a letter addressed to the year 2022. Shortly after Li released it on 31 December 2022, a video recording of the letter was posted on YouTube.

We bring an end to the year with four alternative accounts of 2022. The first is the Xinhua News Agency’s official list of the ten most memorable moments of the year in Chinese and English followed by an analysis and commentary by Wuyue Sanren 五嶽散人, an independent media analyst in Japan. The third is a 盤點 pándiǎn or stock-taking by NetEase News 網易新聞 which, despite its fairly innocuous content, was swiftly deleted by the censorate. We conclude with three videos compiled by Wang Zhi’an, another independent journalist based in Japan.

We end our consideration of memory vs. forgetfulness with a passage from an essay by Simon Leys published shortly after the 4 June 1989 Beijing Massacre.

As China’s viral years of 2020 to 2022 pass, it is worth recalling Leys’s observations especially as people flock back to the People’s Republic often excusing themselves by muttering the tired old line that they too are ‘bolstering the reformist trends in China’. And so we recall the concluding sentiments of Lu Xun’s 1933 essay ‘Written for the Sake of Forgetting’ (in Gladys and Xianyi Yang’s translation):

‘It is not the young who are writing obituaries for the old, but during the last thirty years with my own eyes I have seen the blood shed by so many young people steadily mounting up until now I am submerged and steadily cannot breathe. All I can do is take up my pen and write a few articles, as if to make a small hole in the mud through which I can draw a few more wretched breaths.

What sort of world is this? The night is so long, the way so long, perhaps I had better forget and remain silent. But I know, if I do not do so, a time will come when others will remember them and speak of them …

不是年青的為年老的寫記念,而在這三十年中,卻使我目睹許多青年的血,層層淤積起來,將我埋得不能呼吸,我只能用這樣的筆墨,寫幾句文章,算是從泥土中挖一個小孔,自己延口殘喘,這是怎樣的世界呢。夜正長,路也正長,我不如忘卻,不說的好罷。但我知道,即使不是我,將來總會有記起他們,再說他們的時候的。……

***

The subtitle of this second part of ‘Chinese Time’ comes from a well-known line in The Book of Laughter and Forgetting, a novel by Milan Kundera:

‘The struggle of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting.’

— Geremie R. Barmé, Editor, China Heritage

Distinguished Fellow, The Asia Society

2 January 2023

***

Related Material from Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium

- Chapter Twenty-three — Chinese Time, Part I: 新鬼舊夢— More New Ghosts, Same Old Dreams, 1 January 2023; Part II: 忘卻的紀念 — the struggle of memory against forgetting, 2 January 2023

- Prologue 真面目 — The True Face of Mount Lu, 1 January 2022

- Chapter Three 迴 — Turn, Turn, Turn, 迴 The Tyranny of Chinese History, 10 March 2024; 旋 The Lugubrious Merry-go-round of Chinese Politics, 15 March 2024

- Chapter Twenty-one 醒 — Awakenings — a Voice from Young China on the Duty to Rebel, 14 November 2022

- Chapter Twenty-two 官逼民反 — Fear, Fury & Protest — three years of viral alarm, 27 November 2022 (see also Appendix XXIII 空白 — How to Read a Blank Sheet of Paper, 30 November 2022; Appendix XXIV 職責— It’s My Duty, 1 December 2022; and, Appendix XXV 贖 — ‘Ironic Points of Light’ — acts of redemption on the blank pages of history, 4 December 2022)

- An Announcement: 陰魂不散 — Tedium Continued — Mao more than ever, 26 December 2022

Additional Material:

- 梅六兒,新年寄語:酒後吐真言 總結2022年,油管,2022年12月31日

- Yuan Li, Amnesia Nation: Why China Has Forgotten Its Coronavirus Outbreak, The New York Times, 27 May 2020

- Louisa Lim, The People’s Republic of Amnesia: Tiananmen Revisited, Oxford University Press, 2015

- Linda Jaivin, Yawning Heights: Chan Koon-chung’s Harmonious China, China Heritage Quarterly, No. 22, June 2010

***

Contents

Click on a highlighted title to scroll down.

- Chinese Time

- A Message from China’s Conducător

- Sixty Years Since Deng Tuo’s Evening Talks at Yanshan

- How to Treat ‘Amnesia’

- Li Chengpeng on a Strategy for Survival

- ‘Take it from me, we are losing the war because we can salute too well’

- Four Accounts of the Year 2022

- Tidal Waves of Truth

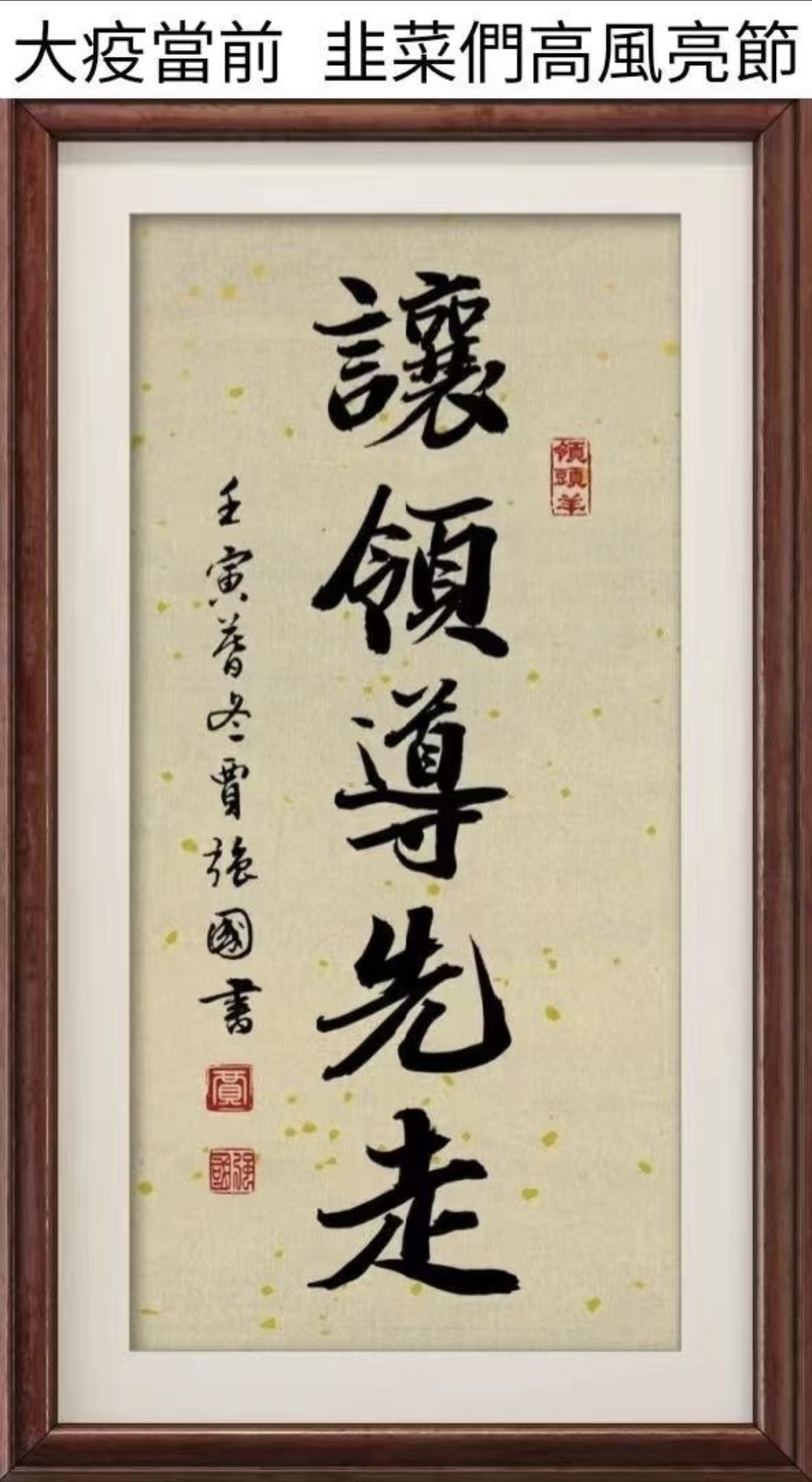

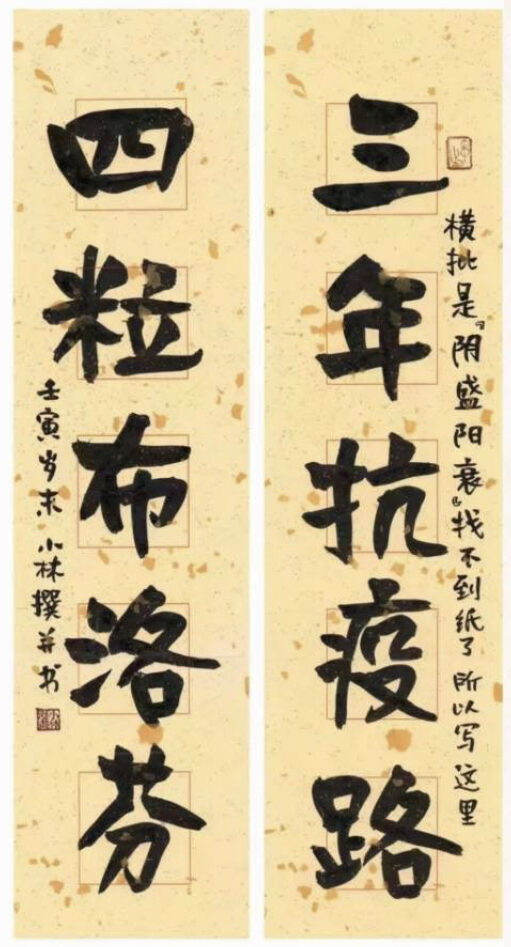

- Leaders Should Lead by Example

Lu Xun illustrated his essay ‘Written for the Sake of Forgetting’ with this woodcut by Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945). Source: MoMA

Chinese Time

The People’s Republic of China has only one timezone, and it is preternaturally set to follow Beijing Time. The clocks of the nation were adjusted to Beijing Time in 1949. As a result of political movements, economic policies and social engineering, the life of the nation and its peoples were forced to follow central time. In recent decades the dominant monolithic Chinese Time has repeatedly fractured, be it by necessity or due to circumstance. Although Beijing Standard Time continues to measure out the days, months and years of Official China, other parallel temporalities, and the memories that they generate, ‘go against the grain’ and jostle in uneasy co-existence with it.

- Leader’s Time is the most important expression of the party-state. It divvies up the nation’s lived reality according to the pronouncements, speeches, obiter dicta, meetings and actions of The Leader, Xi Jinping, and his cohort. It calibrates future plans, sets deadlines and measures progress.. It is constantly enriched by His movements, both in- and outside China. It is the ultimate KPI. Every appearance of The Leader adds a new dimension to China’s spatiotemporal landscape; every foreign visit extends His notional embrace of the world. Although Leader’s Time is coterminous with the biological existence of the actual leader, the official obsequies will declare that the Leader ‘will live on in our hearts forever’. For his rivals and opponents, the Leader’s Time went into a countdown from 22 October 2022, the last day of the Twentieth Congress of the Chinese Communist Party.

- Party Time unfolds in tandem with Leader’s Time, although it both far predates it and will also extend far beyond His time. The tick-tock of Party Time is officially set at 1 July 1921. It encompasses all officially approved, gazetted, remembered and celebrated moments, personalities and events of the Party since then. Party Time contains within it New China Time, that is the time-scape of the People’s Republic of China’s party-state which was set in motion on 1 October 1949. The interwoven story of Party Time and New China Time will be coterminous. Even during the After Time — when they are freed from the censorious fetters of Party historians and ideologues — Party Time and New China Time will continue, commingled with actual historical time.

- Economic Time exists both in and around Leader’s Time and Party Time. Economic realities can be infamously resistant to the prerogatives of the party-state and, over the last seventy years, ignoring or flagrantly breaching Economic Time has resulted variously in calamity and disruption. Since the death of Mao Zedong in 1976, although the Leader and the Party have generally bowed to the demands of Economic Time, the present Leader displays a Maoist self-belief in the ability of ‘man to conquer nature’ despite economic reality.

- Social Time is multidimensional, rancorous and frequently the focus of contestation. It measures out the overlapping ways in which Chinese society unfolds amidst a welter of events, many of which are overseen (or overtly not seen) by both The Leader and The Party. More importantly, Social Time is the really of ‘actually existing socialism’, an on-the-ground reality that evolves sometimes because of and often despite Party Time. Unlike its predecessors in the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc, over its forty-five-year history China’s ‘actually existing socialism’ has frequently pitted economics against politics, or at least required China’s political masters to recognise if not bow to economic reality. Significant ructions in Social Time — unplanned and unexpected outbursts of undeniable reality — have been a common feature since 1976. This has been the case in China Proper, in the occupied territories of Tibet, Xinjiang, and in Hong Kong.

- Carceral Time pullulates within the shadow network of overt and covert surveillance. incarceration, labour reform, ‘vocational training’ and institutionalisation. This is the temporal gray zone of the party-state; its insistent metronome recalibrates the lives of all who are in its thrall. At just about any point, and for nearly any reason, an individual can find themselves transmigrated into this temporal twilight zone.

- Me Time is a temporal realm experienced on an individual level. It can respond to, act in regardless of, or be in direct opposition to the other times. Me Time is the realm of the private, the family, the clan, friendship circles, sodalities, professional alliances and of the ineffable heart-mind of the individual.

- Virtual Time is the most elastic and ineffable time zone. Contemptuous of borders and restraint, in it both the individual and the collective can thrive, be it online or in the heart. We have previously referred to the better angels who inhabit the realm of Virtual Time as citizens of the Invisible Republic of the Spirit. Its dark doppelgänger is populated by crippled souls confounded by conspiracy fantasies and glorify those who hanker after power, extol domination and revel in subjugation.

- (Taiwan/ The Republic of China has time-scapes unique to itself. The Leader, The Party and many people in the People’s Republic would like nothing so much as to force them all ‘into sync’ with Beijing Time.)

There are historical junctures when the various parallel and imbricated times, as well as Official and Other China bristle with unexpected synergy. I have experienced first-hand such moments in April 1976, December 1978-March 1979, December 1986, April-June 1989 and during the 2008 Olympic Year. Another significant juncture occurred in April 1999 when Falungong practitioners surrounded the Zhongnanhai party-state compound.

***

Further Reading:

- The Pirouette of Time — Introduction to ‘After the Future in China’, China Heritage, 28 January 2019

***

A Message from China’s Conducător

In November-December 2022, China’s carefully calibrated ‘time signature’ experienced another syncopation. As Beijing precipitously implemented an unplanned (and ill-conceived) policy U-turn to deal with the three-year-long coronavirus crisis, some local Party leaders flagrantly ignored both Leader’s Time and Party Time. Mindful of the possibility of mass protests over the daily Covid carnage, they responded to intense public pressure to report truthfully on the situation. (See, When Zig Turns Into Zag the Joke is on Everyone, China Heritage, 12 December 2022; and, Without a Covid Narrative, China’s Censors Are Not Sure What to Do, The New York Times, 22 December 2022.)

Subsequently, the Party devised an audacious narrative to justify its own policy confusion — lockdowns etcetera had spared The People the Covid maelstrom that had devastated the outside world and had allowed China time to prepare for a planned opening up, one which was now being carried out in a timely and punctilious fashion, and so forth and so on.

Party Central moved quickly to impose the new narrative and in late December at the first Democratic Life Meeting of the seven-man Politburo installed at the Twentieth Party Congress, Xi Jinping sternly reminded the 100 million members of the Party that adherence to firm, centralised Party leadership, and its narrative, was ‘not an abstract concept’ 黨中央集中統一領導是具體的而不是抽象的. Xi warned his comrades that:

‘At all times and in all circumstances, it is essential to maintain unity with Party Central. There must be strict harmony with the grand symphony being directed by Party Central. Any cacophony is as utterly unacceptable as are discordant voices that would sing a different tune.’

任何時候任何情況下都要堅持同黨中央保持高度一致,在黨中央統一指揮的合奏中形成和聲,決不能荒腔走板、變味走調。

Watching Xi Jinping deliver his New Year’s Message from his stage-set office on 31 December 2022, this writer was reminded of a line in Elena Gorokhova’s memoir, Mountain of Crumbs:

‘We know they are lying. They know they are lying. They know that we know they are lying. We know that they know we know they are lying. And still they continue to lie.’

Regardless of the brazen disparity between the Party’s rationalisations and stark reality, a People’s Daily commentary on the speech declared:

‘The ship of dreams needs a helmsman; the journey of revival needs someone to lead the way.’

夢想的航船,需要掌舵者;復興的徵程,需要領路人.

***

Further Reading:

- Xi the Exterminator & the Perfection of Covid Wisdom, 1 September 2022

- A Hosanna for Chairman Mao & Canticles for Party General Secretary Xi, 22 October 2022

- In My End is My Beginning — Chairman Xi’s New Clothes, 13 December 2022

- Ever More Arrogant & Proud — Xi Jinping’s Rule in the End-time of Covid, 14 December 2022

Sixty Years Since Deng Tuo’s

Evening Talks at Yanshan

Xi Jinping’s monumental Covid obfuscations in 2022 were reminiscent of Mao Zedong’s infamous prevarications of 1962 — a willful denial of the gruesome reality wrought by the policies of the Great Leap Forward. Today, as then, satire and veiled criticisms offer some relief from near universal despair.

A series of essays was published in Beijing Evening News under the heading ‘Evening Talks at Yanshan’ 燕山夜話 during 1961-1962. Writing under the nom de plume Ma Nancun 馬南邨, Deng Tuo (鄧拓, 1912-1966), a senior and loyal Party scholar-bureaucrat, composed the essays in the aftermath of Mao’s murderous Great Leap Forward. They enjoyed tremendous popularity. However, as Simon Leys remarked, ‘Foreign observers were puzzled: why should these modest little articles dealing with various historical literary anecdotes arouse such enthusiastic interest?’

The answer was provided in 1966, with the first stage of the Cultural Revolution. Violent attacks were launched against Deng Tuo. … The attacks included a detailed exegesis of Deng’s writings, identifying the hidden meaning of each of his articles. Actually they had constituted so many parables, transparent to the initiates, which daringly criticized the person, style, and policies of Mao Zedong.

As Leys wrote in The Chairman’s New Clothes (1972), his famous 1972 account of the Cultural Revolution:

***

It is perhaps no exaggeration to say that to future historians who approach this period of bureaucratic tyranny, people such as Wu Han and above all Deng Tuo will appear as those who, throughout these shameful years, really saved the honour and dignity of the Chinese intellectuals. The price which they eventually had to pay was heavy. They knew this in advance, but they did not shirk their mission. Deng Tuo took as his moral pattern the scholars of Donglin 東林黨 (a group of intellectuals at the close of the Ming period, who risked the worst kinds of torture by making political criticisms of a corrupt imperial regime), and foresaw his own destiny in the following lines:

Do not believe that men who wield the pen only know how to chatter emptily 莫謂書生空議論,

When they are under the executioner’s axe, they know how to show their red blood! 頭顱擲處血斑斑。

… Resorting to historical parables in order to criticise the present is a Chinese tradition which is as old as historiography itself (even the “Chronicle of Springs and Autumns”, which is attributed to Confucius, was read by the old commentators as a kind of coded message, with each word concealing scathing judgements on political morality); through centuries of autocracy and imperial censorship, Chinese scholars have had little more than this with which to challenge orthodoxy and make unconventional opinions heard.

This form of parable, which is the traditional weapon of Chinese polemics, was used with a superior dexterity and verve in the political writings of Deng Tuo. From the beginning of 1961 until September 1962, Deng Tuo published a series of short articles in various Peking newspapers (Beijing Daily, Beijing Evening News, Guangming Daily and the periodical Frontline). Under the guise of moral fables and historical anecdotes (sometimes serious, sometimes humorous), literary and artistic commentaries and various other pieces, they present a devastating critique of Maoism. These articles deal with a wide range of issues, but certain broad themes can be distinguished.

- A plea for the rehabilitation of Peng Dehuai 彭德懷 [the Minister of Defense ousted in 1959 by Mao and denounced in a campaign led by Liu Shaoqi for his frank appraisal of the devastation of the Communist Party’s Great Leap Forward policies], under the guise of sketches of various historical figures who had incurred the displeasure of the sovereign by attempting to alleviate the sufferings of the people.

- Attacks against the person and style of Mao: his taste for hollow slogans, his tendency to substitute words for reality, his thirst for personal glory, his vanity, his intolerance of criticism, his lack of realism, his inability to listen to the advice of competent people, his blind obstinacy. It is false that Mao is a “great man”. He is a “whining Zhuge Liang”, an amnesiac who forgets his own promises and goes back on his word; he should, as a matter of urgency, “keep quiet and take a rest”, or he will find that his psychologically unbalanced nature has turned to “wild insanity”.

- A criticism of the Maoist political line. Mao, with his subjective and arbitrary political line, resembles the emperors of former times surrounded by their little circle of corrupt eunuchs; his policies are worked out without any consideration for suggestions from the base, and he ignores and despises the opinion of the masses. Lacking specialised knowledge and practical experience, Mao pursues unrealistic chimeras; he substitutes trickery for real intelligence, and practices despotism which is based on violence and coercion, in defiance of the principles of social and political morality.

- A criticism of the “Great Leap Forward”. This was carried through without any consideration for the natural limits of human strength, and imposed too heavy a burden on the peasants. Mao’s dream of a fantastic multiplication of a modest initial capital merely led to the evaporation of this capital; illusion was substituted for reality as the point of departure, and an unrealistic “moral factor” was substituted for objective material conditions, so that the whole enterprise came up against a wall of realities.

- On the positive side, Deng Tuo reminded the intellectuals of their responsibilities and their mission. Their duty was to right wrongs, as the wandering knights [遊俠 yóu xiá] used to do. They had to shout the truth aloud and “meet the tyranny of the wicked with indomitable resistance”, even at the risk of their lives; they had to remain attentive to the world around them, and politics had to remain their constant concern. Their studies and their teachings had to be opened to political commitment; in their writings, they had to learn every means possible of making the truth heard, directly or indirectly.

— Simon Leys, The Chairman’s New Clothes (1972), pp.33-35

(romanisation converted to Hanyu pinyin)

***

How to Treat ‘Amnesia’

專治「健忘症」

Deng Tuo 鄧拓

translated by Geremie R. Barmé

- At the time, the following essay was interpreted as a comment on Mao Zedong who, after having orchestrated the tragedy of the Great Leap Forward, behaved with impunity. Sixty years later, Xi Jinping’s COVID zig-zag has been mocked in similar terms (see When Zig Turns Into Zag the Joke is on Everyone, 12 December 2022). Contemporary scholars have argued that Deng Tuo was not, in fact, alluding to Mao’s notorious ‘forgetfulness’. Regardless, in 2022-2023, no Party intellectual, nor indeed any establishment intellectual, has had the daring to emulate Deng Tuo (see Where is China’s Intelligentsia during the Covid Emergency?, 22 December 2022; also Less Velvet, More Prison; and, Elephants & Anacondas).

— trans.

There’s lots of sick people in the world who suffer from every kind of affliction. Amnesia is one of the more peculiar illnesses; it is both particularly disruptive and not easily cured.

Those suffering from amnesia present with an array of symptoms. They include, for example, an inability to remember what they’ve seen, difficulty recalling what they’ve said and, even worse, an unwillingness to acknowledge what they’ve done. Sufferers of amnesia often end up being forced to eat their own words or blathering things that cannot be believed. In more serious cases people end up completely stymied: is the afflicted person pretending to be a crazy or are they really just as stupid as they seem to be? Regardless, they’re untrustworthy. … …

It would appear that the symptoms of this particular amnesiac are very serious indeed and it’s impossible to predict how bad things might become. More likely than not, they will either go nuts or end up as an imbecile.

世上有病的人很多,所患的病症更是千奇百怪,無所不有,其中有一種病症,名叫「健忘症」。誰要是得了這種病症,就很麻煩,不容易治好。

得了這種病的人,往往有許多症狀,比如,見過的東西很快都忘了,說過的話很快也忘了,做過的事更記不得了。因此,這種人常常表現出自食其言和言而無信,甚至於使人懷疑他是否裝瘋賣傻,不堪信任。…

According to traditional Chinese medical texts, there are two main causes of amnesia and the condition manifests itself in two particular ways. The Numinous Pivot records that amnesia is caused by a person’s qi being out of kilter. This leads both to forgetfulness as well as extreme mood swings. The sufferer has difficulty speaking, is given to outbursts of temper and may well end up going barking mad. Another common cause of the affliction is head trauma. This leads to the patient experiencing waves of numbness, blood rushing to the head and episodes of fainting. As in the previous case, if the condition is not treated immediately, the patient may end up becoming a complete idiot.

If either of these conditions is detected the sufferer must immediately take bedrest; they mustn’t say another word; and, they mustn’t do anything at all. If they force themselves to speak or act it could well result in serious jeopardy.

Given this dire state of affairs, can’t any proactive measures be taken to help the amnesiac? Of course there are. Ancient Chinese witch doctors were of the belief that when a person was having an episode their head should be doused in dog’s blood and then washed in cold water. It was believed that this would momentarily stimulate clarity of mind. If this treatment proved not to be immediately efficacious, then it had to be repeated two more times. Of course, there is no scientific basis for such witch doctor’s cures, so that’s why we should try a treatment based on modern Western medicine. It takes the form of ‘shock therapy’ administered via a blow to the head from a bludgeon that has been specially designed for such cases. After giving the amnesiac a through bludgeoning, the patient should be revived immediately.

Needless to say, this should be regarded as a treatment of last resort. … …

看來這位健忘病者的症狀,已經達到相當嚴重的地步。但是,我們還不能估計這種病症發展到最嚴重的時候,會變成什麼樣子,大概總不外乎發瘋或者變傻這兩個結果。

據中國古代醫書記載,患這種病的原因確有兩類,因此,就表現出兩個極端化的症狀。如據《靈樞經》所載,這種病的一個起因,是由於所謂氣脈顛倒失常,其結果不但是健忘,而且慢慢地變成喜怒無常,說話特別吃力,容易發火,最後就發展為瘋狂。還有另一種病因,則是由於腦髓受傷,一陣陣發麻,心血上衝,有時不免昏厥,如果不早治,必致成為傻子。如果發現有這兩極化任何一種的現象,必須趕緊完全休息,什麼話都不要說,什麼事情都不能做,勉強說話做事,就會出大亂子。

那麼,對這種病症,難道就沒有一點積極治療的方法嗎?當然不是。比如,古代有的巫醫,主張在發病的時候,馬上用一盆狗血,從病人的頭上淋下去,然後再用冷水沖洗,可使神志稍清,一次不愈,則連治三次。不過這是巫醫的做法,沒有科學根據,不足置信。現代西醫的辦法,有的是在發病的時候,用一根特製的棍棒,打擊病人的頭部,使之「休克」,然後再把他救醒。不過這種辦法一般的也不敢採用。

***

Source:

- 馬南邨, ‘三家村札記·專治「健忘症」’,《前線》,1962年第14期

***

Li Chengpeng on a Strategy for Survival

There’s been talk of a gradual relaxation of the lockdown:

A pair of lovers driving in Guangzhou hesitated as they approached a check-point. They were expecting that they’d have to have their green health code verified. When no one asked to see their phones they let out a cheer from the depths of their souls. A female friend in Lanzhou said to me: ‘I just want to sing from my balcony at the top of my lungs.’ A father in Chengdu who was no longer required to subject his children to daily Covid tests celebrated by making a TikTok video.

Some of my socially aware friends have remarked that none of these people seem to realise that all those young people with their blank sheets of paper had helped win the freedom that they’re celebrating. Nor do they know that many of those young protesters were detained and still can’t be contacted. We don’t even know their names.

But, I reckon that they do know; they’re just pretending to forget. Ever since the days of Caishikou Market [the execution ground in Qing-dynasty Beijing], our people have long since learned to nurture lifelong grudges when dealing with their enemies and blithely forgetting anyone who has ever done them a favour.

The most fundamental survival strategy in China is forgetfulness.

據說逐步解封了。廣州一對戀人小心翼翼駕車經過關卡時發現真不查碼,爆發出靈魂的歡呼。剛解封的蘭州姐們開心地說「我要在陽台上高歌一曲」。成都的爸爸為孩子不用天天核酸了,發了抖音慶祝。我的一些有良知的朋友們說:他們不知道,正是那些舉白紙的年輕人幫他們爭取來了自由,而年輕人被帶走,失去聯繫,甚至沒人知道名字。

他們其實是知道的,只是假裝忘了。自菜市口之後,國人就學會用一生來記住仇人,但一秒鐘就會忘記恩人。

遺忘,是這個民族的戰略生存之道。

— Li Chengpeng, ‘In my opinion, you should fuck this country in the eye’ 我想,你們給這個國家留點碧蓮,也是應該的, 議報,2022年12月5日

***

‘Take it from me, we are losing the war

because we can salute too well’

Excerpts from ‘A Letter Written to the Year 2022’

Li Chengpeng 李承鵬

translated by Geremie R. Barmé

Li Chengpeng (李承鹏, 1968-) started out as a popular sports reporter but in recent years he has gained notoriety for his scathing essays on contemporary China. The title of his ‘Letter Written to the Year 2022’ is taken from All Quiet on the Western Front, a novel by Erich Maria Remarque published in 1928. Remarque’s work also features in From Heaps of Ashes — reading Erich Maria Remarque and Joseph Brodsky in our barbaric times, Professor Xu Zhangrun’s book-length meditation on contemporary China (see Notre seul parapluie — ‘Life is a shitstorm, in which art is our only umbrella.’, China Heritage, 15 August 2022).

For more by Li Chengpeng, see ‘Li Chengpeng’s Columns’ 李承鵬專欄 in Yi Bao《議報》。

— the translator

In a time of injustice, the final refuge of decency is in the writing of history.

在不義的時代,寫史是最後的正義了。

I’ve never been given to writing a summation of the year. If I’d done so, I was convinced that I’d inevitably end up with too much uric-acid-generating purine in my chicken soup [for the soul]. Secondly, I never thought there was much difference between one year and the next. Say, for example, this day three years ago: back then you never would have imagined that a major disaster loomed over Wuhan or that crematoriums in the city would soon be piled high with corpses. The same holds true for today, three years later: who could ever have imagined how long it would take for crematoriums in Beijing, the capital city of China, to get through all of the bodies that have piled up outside?

Three years ago, on 31 December 2019, [the whistle-blower] Dr Li Wenliang was forced to sign a confession which said that ‘I was wrong; there is no virus.’ Now, three years later to the day, when you sign a death certificate for a relative who has succumbed to the coronavirus you have to declare that ‘the deceased did not die from the coronavirus and I will accept full responsibility for any false statement that I make to the contrary.’

Could you have ever imagined that, given the last three years, your life would now turn out like this? Then again, you’ve had absolutely no choice in the matter. Since you can’t take Ibuprofen, even if you wanted to, what right do you think you have to chose a tomorrow for yourself that will more to your liking?

That’s why, in reality, the years 2019 to 2022 are one single year. It’s also why the years from 1949 to 2022 also constitute one single, very long year.

If I really wanted to say something about the nightmare that was 2022, I guess I’d address a letter to it: … …

我從來不寫年度總結,一是怕雞湯嘌呤太高,再就是我一直不明白年度與年度有何區別。你看,三年前的今天,你想象不到再過幾天武漢就將大難臨頭,火葬場屍積如山;三年後的今天,你也想象不出首都北京的火葬場還花多長時間才能燒完那些屍體。三年前,李文亮必須簽保證書「我錯了,那不是病毒」;三年後,你去辦死亡證明也得簽承諾書「我承諾,逝者XXX非因新冠病毒肺炎去世,若有隱瞞,願負一切責任」。你也不敢想象三年後,你的生活是什麼樣子,因為你沒有選擇權,你連布洛芬都沒得選,哪敢選擇明天。

所以,2019年—2022年,是一年。其實1949年—2022年也是一年。

如果一定要為悲慘的2022年寫點什麼,就寫一封信吧:… …

And so when I think of 2022 I feel that even if we don’t deserve the kind of ‘red dignity’ [that the Communist Party bestows upon itself], at least we can hold on to our black humour.

Many people have died this year: from those who were killed while being transported to that temporary hospital in Guiyang to the people who died in the conflagration in that Urumchi apartment building. Then, of course, there was the young violinist who jumped out a window during the Shanghai lockdown; the nurse with Covid who died at the entrance to her own hospital while waiting to be taken in for treatment; the miscarried fetus in Xi’an; and, of course, there was that 28 year-old who died during enforced isolation. Remember him? He was the fellow who, by the time his family was allowed to go looking, had already gone stiff with rigor mortis? Remember, too, how his parents cursed … So very many have died. I have lost count and I can’t recall. Although each and every one of them died in a different way, they all share one thing in common: None of them had to die.

The Chilean poet Pablo Neruda put it like this:

… death also goes through the world dressed as a broom,

lapping the floor, looking for dead bodies,

death is inside the broom,

the broom is the tongue of death looking for corpses,

it is the needle of death looking for thread.

But in the case of these people, there was nothing sudden about their deaths — they were all murdered. If, for example, on that particular day, the local Party leader had been happy because they’d had sex with their lover, and so they didn’t order that busload of people to be forcibly packed off to a temporary hospital. None of them would have died.

The National Health Commission claims that: ‘The people support our coronavirus policy and it will pass the test of history.’ How truly shameless do you have to be to make such a claim? [The infamous harlot] Pan Jinlian might as well say that history has vindicated her approach to love. Forgive us, Ms. Pan, I know you had your reasons.

Liang Wannian, head of the Chinese National Health Commission’s Covid Response Expert Team, claimed that government policies had prevented excessive mortality. Do you know about Black Holes? No one can never know what goes on inside a black hole. Well, we have one here on earth and it is called the National Health Commission. No one will ever know just how many deaths its black hole is hiding.

是的,我的2022,我是這麼想的——如果我們不配擁有紅色的尊嚴,總得守住黑色的幽默。

這一年,死了很多人。有貴陽轉運方艙的大巴,有烏魯木齊的大火,有上海封城時翻身跳樓的小提琴手、被一張核酸證明憋死在自家醫院門口的護士,有西安孕婦腹中流產兒,還有蘇州一個28歲青年感染後獨自隔離,死了好幾天才被發現。當父母趕來找到他時,身體已硬了,父母當街大罵XXX……太多,我實在記不清。他們死法各有不同,但有一個共同點:他們本不該死。

雖說智利詩人聶魯達說「死亡是針每個人的一件忽然的事」。但他們的死並非忽然,而是謀殺。要是那天領導因為跟小三撩騷心情好,決定今晚不轉運住戶,他們就不會死。

國家衛健委:我國防控得到了人民認可,經得起歷史檢驗。臉皮得厚到什麼程度才說得出經得起歷史檢驗,潘金蓮可不可以說自己經歷了愛情的考驗。對不起,潘姑娘,你還是有苦衷的。

首席專家梁萬年:我國疫情期間並未發生大面積死亡。宇宙中有個天體叫黑洞,你永遠不知道裡面發生了什麼。我國有個組織叫衛健委,你永遠不知道死了多少人。

The action of the film Back to 1942 [which is set against the backdrop of wartime famine] takes place during the days of the ‘evil Old China’. Henan province is shown strewn with the corpses of people who starved to death. The actor Li Xuejian plays the provincial governor and at one point he goes to the wartime capital of Chongqing to report to President Chiang Kai-shek. They are shown walking over a bridge and Chiang asks in sombre tones, How many have died? The governor replies, Well, our official statistics put it at 1062 people. Chiang locks his eyes in a stare: And, in reality? ‘Well, it’s about three million’, the governor replies.

Despite the fact that all of that was back in the days of the ‘evil Old China’, at least then the authorities admitted that the dead had starved to death during the war. Some kernel of historical truth was mixed up in all of the fiction. We, however, live in a vaunted Prosperous Age, so the deceased don’t even have the right to die from the coronavirus. The authorities try avoiding the term ‘virus’ at all costs. Surely, Ah Q would approve. … After all, the government spokesperson has claimed that China has dealt with the pandemic more successfully than any other country. They have even celebrated the fact the ‘opening up process’ [since early December 2022] has been orderly and measured. … …

電影《一九四二》,萬惡的舊社會,河南餓殍遍地,飾演省長的李雪健跑到重慶面謁蔣介石。氣氛凝重,兩人走在橋上。

蔣介石問:培基啊,河南這次餓死多少人。李雪健:嗯,政府統計,是,1062人……蔣介石(回頭,凝視):實際呢……李雪健:嗯……實際,大約……三百萬人。

即使萬惡舊社會里,那些餓殍也允許被證明死於飢荒,畢竟遭遇戰亂,畢竟歷史真假參半。但盛世亡靈卻不被允許死於新冠,新冠肺炎也改名新冠感染,這讓忌諱「光」「亮」「癩」的阿Q都感到釋然……因為,新聞發言人說:中國的防疫是全球最成功的,這次放開是有秩序按步驟的。… …

In retrospect, a lot of the things that happened during 2022 seem ridiculous, even absurd. Upon closer inspection, however, they still reflect the irrefutable logic of power. When an organisation [like the Chinese Communist Party] is not constrained in any way and under no pressure to respond to public opinion, it can easily claim to enjoy unquestioned moral authority. It can then go about brainwashing society and mobilising people to go about doing evil with a sense of holy purpose, even when that evil is directed at oppressing themselves … [T]he upshot is to further entrench unrestrained power and enhance the belief among the power-holders that they are possessed of some kind of moral superiority. The cycle is self-perpetuating and it reinforces itself.

Once you appreciate this fact you’ll understand why the year 2022 saw the system reach a new high-watermark in terms of the number of online posts that were deleted and the number of people [who were called in by the police to] drink tea. Ever greater heights now await! The logic of the formula at work here goes as follows:

The blockading of the truth = allows for the affirmation of the morally superior stance of the power-holders = and the further enhancement of totalitarian control.

In an environment in which commonsense has taken a holiday — as in the case of the New Year’s headline of Southern Weekend which extolled its chicken-soup-like recipe that China can boast ‘A belief system built on the willingness of people to throw themselves into the struggle regardless of their personal safety’, or in the case of [the uber-patriotic academic] Jin Canrong’s grand claim that ‘Since the Chinese race has suffered for over three millennia, next year we will finally be able to stand at the pinnacle of the world’ — people are encouraged to forget the pain of all of their suffering. If that doesn’t work, then [the system tries at a minimum to] convince people that whatever suffering they are experiencing at the moment is well worth while because it is actually part and parcel of a journey that is leading to a bright and better future.

Despite everything that happened during the year, the authorities constantly encouraged everyone to think that the devastation wrought by the virus being limited by a policy that put ‘the lives of the people over anything else’ [以人為本]. But, were you aware what really mattered more than anything to them was the opinion of that one person [本人以為, that is, Xi Jinping]. … What you thought was an epidemic, has turned out to be yet another political movement. For good reason people are asking, when will they ever really release us from their ‘lockdown’. … …

2022年發生了很多怪事,表面上荒誕不經,其實都符合事情強大的運行邏輯——當一個機構組織沒有了權力制約,就將沒有輿論阻力,沒有輿論阻力,就將擁有巨大道德優勢,這種官方道德優勢是一種洗腦,動員人們滿懷神聖感參與做惡,以及對自己做惡……然後進一步鞏固沒有制約的權力,進一步抬高官方道德優勢,是精巧的輪回效應。

所以你明白為什麼2022年刪貼銷號喝茶達到頂峰且還會有更高峰,屏蔽真相=建立官方道德優勢=極大鞏固權力,很符合邏輯。在缺乏常識的地方,像《總有一種奮不顧身的相信》這樣的雞湯和金燦榮那種「這個民族經歷了三千年苦難後,明年將真正站在世界之巔」宏大敘事,讓人忘卻痛苦,至少讓人們以為目前痛苦是達到光明彼岸的一種必須擺渡。

2022發生了很多事,總而言之就是:你以為在疫情肆虐下,會「以人為本」,最終卻成了「本人以為」……所以這不是一場病毒,這是一場運動。總有人問,為什麼還不解封。… …

I’ll conclude this Letter to 2022 by referring to the novel All Quiet on the Western Front. I feel what we’ve been through is somewhat similar [to the environment of WWI described in that book]. The novel is about a young man by the name of Paul Bäumer and his group of idealistic friends who sign up to fight in the Great War. They are shocked by the grueling reality of life on the front — the violence, the darkness, the hunger, the sadism of their commanding officers and the merciless meat-grinder that is war. One by one they die in action. Wounded, Paul returns home on leave, but is repelled by all of the empty glorification of war that he encounters there. His revulsion results in him being seen as something of a traitor to the cause. Paul returns to the front to face the constant bombardment and the churning advance of the tanks. One of his friends stabs himself to death in despair and Paul watches as his lifeblood drips away … The war is all-encompassing and eventually everyone loses any hope that it will ever come to an end. Paul constantly ask himself what it is all for.

On one uneventful day on the front, Paul is bayonetted. He dies with his doubts unresolved. His death is neither tragic nor heroic. The war had started with grand sound and fury, but its denouement comes about without fanfare. In fact, it ends so suddenly that people are left stunned.

‘He fell in October 1918, on a day that was so quiet and still on the whole front, that the army report confined itself to the single sentence: All quiet on the Western Front.’

Throughout his time at the front Paul had thought to himself: ‘If you give up you can escape being hit, but the moment you start thinking about what’s happening, you’ll lose the will to live.’ And, ‘Some people ask questions, others don’t. Those who don’t question anything are proud of their silence.’ And, again, ‘Our youth will pass by as death stalks us.’

In the end, we too return to a profound line [from earlier in the novel]:

‘You take it from me, we are losing the war because we can salute too well.’

最後,給2022年寫的這封信將用《西線無戰事》作為結尾,因為很像。故事講的是一戰時,保羅等七個德國年青人為了崇高理想報名參軍,等到前線才發現遠不是他們想象的,殘忍、黑暗、飢餓、長官的虐待毆打,戰爭是絞肉機,一個個夥伴在身邊倒下。保羅養傷中途回到家鄉,卻因不願過多頌揚戰爭而遭人們非議,甚至被認為是叛徒。他回到戰爭,沖天的炮彈、巨獸般的坦克、絕望的戰友用叉子扎死自己,鮮血像泉水一樣汩汩湧出……戰爭膠著,看不到希望,不知何時結束,所有人感到一切很渺茫。他一直想,為什麼我們要打這場戰爭,這場戰爭有什麼意義。

他還沒想清楚,就以很路人的方式忽然被一個無名小卒從背後捅死,一點都不悲壯,一點都不英雄,甚至沒有一點結束感。戰爭轟轟烈烈開始,極其草率地宣佈結束,突然得讓人們都沒法接受。他於1918年10月陣亡。那天,整個前線寂靜無聲,軍隊指揮部戰報上的記錄僅有一句:西線無戰事。因為,雖然死很多年輕人流了很多血,但雙方並沒有推進陣地,所以並不代表發生了戰爭。

所以,西線無戰事。

保羅一路打仗,一路內心獨白,比如「人只要屈服,就能躲避打擊,但去思考,就立即活不下去」,比如「有些人提問,有些人不問,那些不問的人為自己的沈默感到驕傲」,比如「年華將化為烏有,我們終有一死」。

他最後說的那句最深刻:

「聽著,這場戰爭我們輸定了,因為我們敬禮敬得太好。」

***

Source:

- 李承鵬,致2022一封信:這場戰爭輸定了,因為我們敬禮敬得太好, 2022年12月31日

***

Four Accounts of the Year 2022

We end our account of memory vs. forgetting with four perspectives on the year that has just passed:

- The first is an official summation of the year’s news released by the Xinhua News Agency;

- The second offers a critique of the Xinhua account by Wuyue Sanren, a former mainland journalist who now lives in Japan;

- The third, by NetEase News, follows the official narrative within reason, but it both honest enough and popular enough for the authorities to censor it; and,

- In conclusion, we offer Wang Zhi’an’s three-video retrospective on the year.

***

Xinhua’s Ten Best News Stories for 2022

- 新華社評出2022年國內十大新聞, 新華社, 2022年12月29日

- Xinhua, Top 10 China news stories of 2022

***

The Memory of Official China vs. the Memory of an Individual

Wuyue Sanren 五嶽散人

Source:

- 五嶽散人,国家记忆VS个人记忆:新华社的十大新闻与我个人总结的十大新闻, 油管,2022年12月30日

***

Rather than Losing Yourself in the Stars,

Better to Live in the Here and Now

A Retrospective of 2022 by NetEase News 網易新聞 Censored in China

網易新聞2022年度事件盤點:幻想星辰大海不如活在當下

‘We are too quick to accept the reality presented to us, even though that reality is totally unrealistic. The year 2022 should not come to an end with a simple full-stop. Life is a garden with many forked paths (a reference to Jorge Luis Borges’s 1941 story The Garden of Forking Paths).’

我們太容易接受現實

因為現實總是那麼不真實

2022年不該被這樣畫上句號

人生還有小徑分叉的花園

***

Source:

- 網易新聞2022年度事件盤點:幻想星辰大海不如活在當下, 中國數字時代, 2022年12月29日

***

An Unforgettable Year

Wang Zhi’an 王志安

A prominent journalist and broadcaster with Central China TV in Beijing, Wang Zhi’an (王志安, 1968-) resigned from his job in 2017. After a new media venture was closed down Wang’s social media accounts were cancelled by the internet censorate and his work banned. Wang lives in self-imposed exile in Japan where he hosts Wang Sir‘s News Talk 王局拍案, a popular news analysis channel on YouTube. See also:

- Awakenings 醒 — a Voice from Young China on the Duty to Rebel, 14 November 2022; and,

- 袁莉, 王志安:央视、审查和“大外宣”, 《不明白播客》,2023年1月7日

As if in the blink of an eye, the year 2022 has come to an end. For most people in China it was an extremely challenging time. We have been through so very much — far too much.

Even though the year has drawn to an end, we should not, we cannot, forget what we have been through.

The following videos have been compiled to help us remember. May they serve as a record of our time together.

一轉眼,2022年就要過去了。這一年,對於生活在中國境內的每一個人,可能都分外艱難。這一年,我們經歷了太多太多。雖然這一年就要過去了,但我們過去一年的共同經歷,我們無法忘記,也不該被忘記。

歲末之際,我們製作了三集回顧視頻,希望這些記憶,永遠留存在,我們的歷史里。

— trans. GRB

***

1. Lockdowns

2022我們無法忘記之一:封城

2. Separations

2022我們無法忘記之二:別離

3. Outcry

2022我們無法忘記之三:吶喊

Tidal Waves of Truth

Simon Leys

Yet sometimes—as we have just witnessed in Beijing—truth breaks free. Like a river that ruptures its dams, it overwhelms all our defenses, violently erupts into our lives, floods our cozy homes, and leaves high and dry in the middle of the street, for all to see, the fish that used to dwell in the deep.

Such tidal waves can be very frightening; fortunately, they are relatively rare and do not last long. Sooner or later, the waters recede. Usually, brave engineers set to work at once and start rebuilding the dykes. The latest attempts by the Communist propaganda organs to explain that “no one actually died on Tiananmen Square” may betray a slightly excessive zeal (one is reminded of the good souls who, probably wishing to restore our faith in human nature, insisted that, in Auschwitz, gas was used only to kill lice), but if we give them enough time, in due course their ministrations will certainly succeed in healing the wounds that the brutal dumping of raw and untreated truth inflicted upon our sensitivities.

Whenever a minute of silence is being observed in a ceremony, don’t we all soon begin to throw discreet glances at our watches? Exactly how long should a “decent interval” last before we can resume business-as-usual with the butchers of Beijing? The senile and ferocious despots who decided to slaughter the youth, the hope and the intelligence of China, may have made many miscalculations—still, on one count, they were not mistaken: they shrewdly assessed that our capacity to sustain our indignation would be very limited indeed.

The businessmen, the politicians, the academic tourists who are already packing their suitcases for their next trip to Beijing are not necessarily cynical—though some of them have just announced that, this time, the main purpose of their visit will be to go to Tiananmen Square to mourn for the martyrs!—and they may even have a point when they insist that, in agreeing once more to sit at the banquet of the murderers, they are actively strengthening the reformist trends in China. I only wish they had weaker stomachs.

Ah humanity!—the pity of us all!…

— from Simon Leys, The Curse of the Man Who Could See

the Little Fish at the Bottom of the Ocean,

New York Review of Books, 20 July 1989.

Also quoted in Supping with a Long Spoon —

dinner with Premier Li, November 1988

***

Leaders Should Lead by Example

Jia Qiangguo