Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium

Chapter Three, Part II

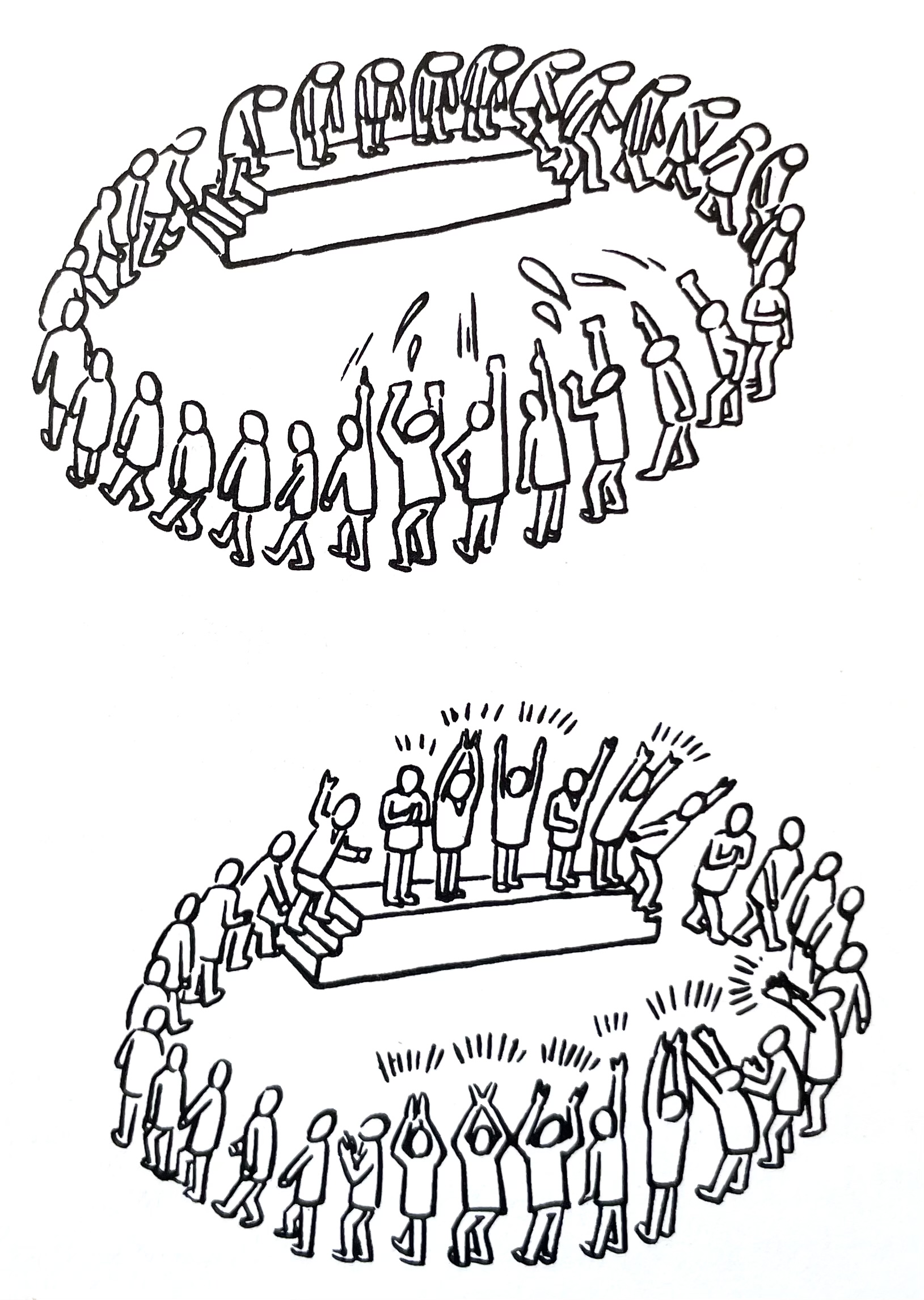

旋

Communist Chinese politics are a lugubrious merry-go-round … and in order to appreciate fully the déjà-vu quality of its latest convolutions, you would need to have watched it revolve for half a century. The main problem with many of our politicians and pundits is that their memories are too short, thus forever preventing them from putting events and personalities in a true historical perspective.

— Simon Leys, quoted in Watching China Watching

***

This is the third chapter in Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium is divided into two parts:

- Part I, The Tyranny of Chinese History which features material from The Tyranny of History: The Roots of China’s Crisis by W.J.F. Jenner, historian, translator and China scholar; and,

- Part II, The Lugubrious Merry-go-Round of Chinese Politics, which draws on New Ghosts, Old Dreams: China’s Rebel Voices by Geremie Barmé and Linda Jaivin.

Although the books The Tyranny of History and New Ghosts, Old Dreams can both be read online via Internet Archive, we encourage readers to seek out print versions of these texts.

***

Contents

(click on a section title to scroll down)

- Wheels & The Mysterious Circle of Mao Zedong — Liu Yazhou

- Never Say Never — Bo Yang

- On China’s National Characteristics — Wu Zuguang

- Recurring Nightmares — Qian Liqun

- I Us’ um Fork Now — Li Ao

- A Lesson from History —- Luo Beishan

- A Knowing Smile — Han Xiaohui

- A Long-term Struggle — Jiang Zemini

- From Sartre to Mao Zedong — Hua Ming

- What’s New? — He Xin

***

***

Preface

Thirty-five years since June Fourth 1989

Seventy-five years since 1st of October 1949

The 6th of January 2024 marked the beginning of China’s alternative anniversary season. On that day 35 years ago, Fang Lizhi addressed an open letter to Deng Xiaoping. The outspoken astrophysicist, who had been denounced for ‘bourgeois liberalism’ that threatened one-party rule in early 1987 and expelled from the Communist Party, reminded Deng Xiaoping that the year 1989 not only marked the fortieth anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China, but also the seventieth year since, during the May Fourth Movement, patriotic students in Beijing and other Chinese cities had called for democracy and rational politics.

Fang Lizhi urged Deng Xiaoping to grant a nationwide amnesty for political prisoners, in particular Wei Jingsheng, a pro-democracy activist jailed ten years earlier. Fang suggested that such ‘a humanitarian gesture … would contribute to a healthy social atmosphere.’

Furthermore, Fang reminded Deng that 1989 was also the bicentenary of the French Revolution, long an inspiration for China, and he said:

No matter how one views it, the slogans of liberty, equality, fraternity, and human rights have gained universal respect.

Fang ended his plea by suggesting that a magnanimous act on the part of Deng Xiaoping would also earn him ‘even greater respect in the future.’

The 6 January 1989 open letter gathered widespread support and it inspired numerous other pleas and petitions to the Chinese government from writers, scholars and scientists who were emboldened by the government’s reluctance to retaliate against Fang. Generally, the petitioners sought safety in numbers as they echoed Fang Lizhi’s call for an awakening of conscience, for fairness and justice. Many also warned that China’s dictatorial political system was stymying social and economic progress.

The spontaneous Petition Movement of early 1989 contributed directly to a mass protest movement that exploded following the death in mid April of Hu Yaobang, a purged liberal Party leader. Initially led by students, those protests were supported by a nationwide response of students in other cities, workers and people from all walks of life. On 4 June 1989, Deng Xiaoping and his comrades, having purged Zhao Ziyang, yet another liberal Party leader in a quasi-coup, ordered troops who had besieged the capital for nearly two weeks, to retake the city, regardless of the cost in human lives.

The Beijing Massacre of June Fourth 1989 not only marked the bloody end of the popular uprising and a historical denouement for hopes of political change, it was also the beginning of China’s Cold War with the West.

***

1989: When the New Cold War Inherited the Old

This storm was bound to come sooner or later. This is determined by the major international climate and China’s own minor climate. It was bound to happen and is independent of man’s will. It was just a matter of time and scale.

這場風波遲早要來。這是國際的大氣候和中國自己的小氣候所決定了的,是一定要來的,是不以人們的意志為轉移的,只不過是遲早的問題,大小的問題。

This is what Deng Xiaoping said when addressing to leaders of the PLA five days after they had imposed martial law under force of arms on the Chinese capital on 4 June 1989.

Deng’s speech reaffirmed the message of the front-page Editorial published by the People’s Daily on 26 April 1989, at the beginning of what would be six weeks of unrest in Beijing and dozens of other Chinese cities. That editorial, written on the basis of the directives of Deng and his elderly comrades, had been broadcast on the evening of 25 April and was published the following day.

The Editorial declared that student-led protests sparked by the death of former Party General Secretary Hu Yaobang were actually led by a secretive group — ‘an extremely small number of people’ — who were fomenting ‘turmoil’ 動亂 dòngluàn ‘to sow dissension among the people, plunge the whole country into chaos and sabotage the political situation of stability and unity. This is a planned conspiracy and a disturbance. Its essence is to, once and for all, negate the leadership of the CPC and the socialist system.’

Talk of a secretive cabal engaged in a conspiracy to ‘once and for all negate’ the Party harked back to dark warnings about foreign interference in Chinese affairs that dated back to 1949 and which had been repeated on numerous occasions, not only during the Mao-Liu era (1949-1966) and the High Maoist years of 1966 to 1976 but also throughout the first decade of the Open Door and Economic Reform (1978-1988).

[Note: For the relevant background to the Sino-Western conflict, see The Harmonious Evolution of Information in China, March 2010; and, White Paper, Red Menace — Watching China Watching (VII), 17 January 2018.]

In his remarks on 9 June 1989, Deng reiterated and expanded on the message of the 26 April Editorial when he said that:

The incident became very clear as soon as it broke out. They have two main slogans: One is to topple the Communist Party, and the other is to overthrow the socialist system. Their goal is to establish a totally Western-dependent bourgeois republic. The people want to combat corruption. This, of course, we accept. We should also take the so-called anticorruption slogans raised by people with ulterior motives as good advice and accept them accordingly. Of course, these slogans are just a front: The heart of these slogans is to topple the Communist Party and overthrow the socialist system. …

In declaring that the aim of the backstage managers of the 1989 protests was to overthrow the Communist Party and turn China into ‘a totally Western-dependent bourgeois republic’ 一個完全西方附庸化的資產階級共和國, Deng acknowledged a decades-long conflict. By publicly identifying the plot against China, first on 26 April and again on 9 June 1989, Deng Xiaoping warned of the scale and significance of China’s clash with the US-led Western order. (For more on the historical context of this contestation, see We Need to Talk About Totalitarianism, Again.) And when, years later, China was encouraged to become a ‘responsible stake-holder’ in the ‘international rules-based order’ under the aegis of America, Deng’s remarks about the danger of the People’s Republic ending up as a ‘Western-dependent bourgeois republic’ resonated once more.

Deng had repeatedly warned against Western values, political ideas and cultural infiltration since early 1979. Advised by Party thinkers like Hu Qiaomu and with the support of a coterie of Mao-era colleagues, in 1979 Deng declared that ‘to achieve the Four Modernizations it is imperative to adhere to the Four Cardinal Principles in the realm of ideology. These principles are:

- Adherence to the socialist road;

- Adherence to the dictatorship of the proletariat;

- Adherence to the leadership of the Communist Party; and

- Adherence to Marxism-Leninism and Mao Zedong Thought.

‘As you all know,’ Deng told Party members, ‘none of these principles are new; our Party has been resolutely adhering to them all along.’ In June 1989, Deng would remark:

There is nothing wrong with the Four Cardinal Principles. If there is anything amiss, it is that these principles have not been thoroughly implemented: They have not been used as the basic concept to educate the people, educate the students, and educate all the cadres and Communist Party members.

The nature of the current incident is basically the confrontation between the Four Cardinal Principles and Bourgeois Liberalization. It is not that we have not talked about such things as the Four Cardinal Principles, work on political concepts, opposition to Bourgeois Liberalization, and opposition to Spiritual Pollution. What we have not had is continuity in these talks, and there has been no action — or even that there has been hardly any talk.

Although the Four Principles had been written into the Chinese constitution in June 1979 and were imposed during a series of fitful ideological and cultural purges (see, for example, The View from Maple Bridge, Part I, 5 February 2023), Deng and his colleagues were also cautious not to let the pursuit of ideological purity interfere with their desperately ambitious economic policies.

Following the destructive Anti-Spiritual Pollution Campaign of late 1983, Deng had even called for an embargo on ideological wrangling for three years. However, student protests in Shanghai and calls for media freedom and democracy in late 1986 put a momentary end to that spat of liberalisation. The subsequent purge of Party leader Hu Yaobang and prominent Party members presaged the denouement of 1989.

Readers will be familiar with the fact that my own doubts about the limits of change in post-Mao dated from early 1979. Although the Party urged people to ‘liberate thinking, seek truth from facts and look to the future’, by frustrating the reappraisal of the past it laid the groundwork for the radical historical denialism of the Xi Jinping era. Similarly, the Four Cardinal Principles, announced in March 1979 and subsequently written into the Chinese Constitution, were an affirmation of the party-state, just as the arrest of Wei Jingsheng was a warning about those who spoke out of turn or advocated an alternative future for the country.

In Seeds of Fire: Chinese Voices of Conscience, a culture-focussed account of post-Mao China published in 1986 which we expanded in the second edition, published in 1988, we chronicled Deng’s repeated warnings about liberalism. We suggested that further clashes between Party ideology and the social forces encouraged by China’s open door and reform policies were inevitable. Our account was also informed by the skepticism of leading Hong Kong critics of Beijing, independent thinkers in China itself and famously insightful writers like Simon Leys. Nonetheless, I found my own bleak view of events repeatedly dismissed by a raft of diplomats, journalists and academics who preferred a narrow and simplistic view of Deng Xiaoping’s economic pragmatism instead of undertaking the hard work to appreciate the ways in which Party ideology not only shaped policy but offered a holistic worldview and means by which China’s power holders made sense of themselves and the world.

In November 1988, between courses at the state dinner held for Chinese Premier Li Peng by the Australian Prime Minister Bob Hawke, I suggested that the power struggle between Li and Party General Secretary Zhao Ziyang — a topic of white-hot speculation both in- and outside China — was, for all intents and purposes, resolved. All that remained was social upheaval and the denouement. Before long, Zhao would indeed take the fall for Beijing’s economic missteps, the Party’s ideological drift and even China’s social anomie. (See Supping with a Long Spoon — dinner with Premier Li, November 1988). The consequences of Zhao Ziyang’s fall proved to be cataclysmic and we are still living with the aftermath of those momentous events.

In the above, I have drawn on Back When the Sino-US Cold War Began, written in the days before the thirty-foruth anniversary of the June Fourth Beijing Massacre in 2023 for the series, Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium. In that essay I also noted that:

In June 1989, Deng had unerringly identified the reason why, with the exception of Zhao Ziyang and some of his younger colleagues, the Communist Party’s leaders had been unified in their approach to the ‘turmoil’ of 1989. ‘What is most advantageous to us’, Deng said,

is that we have a large group of veteran comrades who are still alive. They have experienced many storms and they know what is at stake. They support the use of resolute action to counter the rebellion. Although some comrades may not understand this for a while, they will eventually understand this and support the decision of the Central Committee.

It was this group of elders — the Eight Gerontocrats 八大元老 — a coterie of Mao-era Party bosses who had ruled China from 1949 up to the mid 1960s with draconian ferocity, who proved to be the key to the Communist Party’s post-Mao political stability and systemic intransigence. Even as China had launched an ambitious program of reform from 1978, the Party gentry, which had tentacles and connections of fealty that extended to every corner of China, jealously protected the privileges of their caste and the vision that justified it. Having reluctantly contemplated late-Soviet-like constitutional reform (see Dai Qing’s 《鄧小平在1989》 and Dai Qing at Eighty), the Elders remained true to form in framing 1989 as part of a decades-long Cold War. They felt further justified by the collapse of the Soviet Union in late in 1991 (when, as Xi Jinping put it decades later, no ‘real man’ had defended the cause in Moscow) and they were reassured that the Cold War had never really ended. Soon, the threat of ‘peaceful evolution’ — a multi-pronged strategy of ‘The West’ dating from the 1950s to white-ant Party rule — was back on the agenda, and everything from ideas to colour revolutions would be framed as inimical. As we argued in Prelude to a Restoration, Xi Jinping is heir to the legacy of the Eight Gerontocrats.

***

***

興衰更替

From Prosperity to Contraction

In 2011, we devoted an issue of China Heritage Quarterly to the topic of the ‘Prosperous Age’ 盛世 shèngshì. As I observed in my editorial introduction:

In the late 1980s, as a decade of China’s Reform and Open Door Policies proffered a transformation of the country, anxieties over social change, economic inequalities, environmental degradation, weakness on the global stage and a sclerotic political system generated a national ‘crisis consciousness’ (youhuan yishi 忧患意识). To use Gloria Davies’ expression, ‘worrying about China‘ was widespread. As events would prove, people had good reason to be worried, and they still do.

From even before the 2008 Beijing Olympics a new wave of ‘China worry’ has been swelling in the People’s Republic. At the same time, and despite its awareness of the multiple problems besetting the country, the party-state has advertised the state of the nation as being one reflective of a ‘Prosperous Age’ (shengshi 盛世), or ‘Harmonious Prosperity’ (hexie shengshi 和谐盛世).

Shengshi is an ancient expression and it has been applied to a precious few periods in Chinese history. Such ‘golden ages’ have varied in length and content, but it is commonly recognized that during the Han 漢, Tang 唐 and Qing 清 dynasties there were remarkable periods of social grace, political rectitude and cultural flourishing. The self-proclaimed Prosperous Age of today’s People’s Republic has been nearly a century in the making; its achievement is far more contentious.

I want on to comment that ‘General wisdom, or common sense, would suggest that to declare a particular period or an era to be a Golden or Prosperous Age before it is over may be ill advised.’

It is often a fraught proposition to determine whether a renaissance is underway in the midst of a period of rapid socio-cultural change. And that begs the question whether frenetic economic activity is the ne plus ultra of human endeavour.

As is so often the case with heroic figures, pivotal historical moments, crises, tipping-points and so on, the passage of time, a greater understanding of the complex interaction of politics and society, as well as culture and economics, individuals and mere happenstance, all contribute to more nuanced, if not ‘correct’, evaluations of a certain epoch. In China’s modern history, however, enlightenments, rebirths and revivals have often been hastily announced and hailed in a mood of anxious exuberance. This often happens long before conclusions based on temperate reflection following a decent interval, measured understanding and deep reflection, can be drawn.

The dynastic term ‘prosperous age’ was revived in 2005 and it has now been in common use for nearly two decades ago. Now, in the second decade of Xi Jinping’s rule, however, with the Chinese economic slowdown, demographic decline and political stagnation, both that ancient term and its contemporary relevance are hotly contested once more. Some would argue that the revival of the nation’s fortunes during the three prosperous decades of the Deng-Jiang-Hu era have been squandered, even as Xi Jinping calls for the unleashing of ‘new productive forces’ 新質生產力 as part of the relentless march towards realising the China Dream.

***

A Spectre Still Prowles the Land

In The Tyranny of History, Part I of this chapter in Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium, we referred to the poet Sun Jingxuan 孫靜軒 who had warned about the ‘spectre prowling the land’ as early as 1980. Using the famous metaphor of The Communist Manifesto, the opening line of which was ‘a spectre is haunting Europe — the spectre of communism’, Sun was referring to what he called ‘feudalism’, a Marxist term that in the Chinese context meant autocracy and, in his poem, stood in both for Mao Zedong and Party autocrats like him. Beyond political autocrats, however, Sun was also referring to ingrained social and cultural habits that evolved over millennia and which were reinforced since the Song dynasty by an increasingly narrow State Confucianism. Familial and bureaucratic hierarchies, the attitude towards status, class and power, disdain for independent thought, were all characteristics of dynastic society against which men and women of conscience had rebelled since the late-Qing dynasty and in particular during the May Fourth Era (c.1917-1927.

[Note: For more on the state’s manipulation of Confucianism, see Between Master & Student in The Tower of Reading.]

Sun Jingxuan’s poem featured in Seeds of Fire: Chinese Voices of Conscience, mentioned above. New Ghosts, Old Dreams: Chinese Rebel Voices, from which most of the material below is drawn, appeared in 1992. It was a sequel to Seeds of Fire that updated our earlier cautionary tale. (See 新鬼舊夢— More New Ghosts, Same Old Dreams, 1 January 2023.) The present material, like Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium as a whole, is also a part of what, for me, has been half a century of work related to China, its culture, history and politics. — On 15 October 2024 I will commemorate the fiftieth year since I went to Beijing.

As a twenty-year-old exchange student who had studied classical and modern Chinese, as well as some history and Buddhology during my undergraduate years in Canberra, Australia, I had gone to in pursuit of my dual interests in revolutionary modern history and traditional thought and culture. I arrived in China during the latter stages of the Criticise-Lin Biao, Denounce Confucius Campaign and my studies — initially in Beijing, then in Shanghai and Shenyang — straddled the last years of Mao, his Cultural Revolution and the first year of post-Mao China. Later, from a perch in Hong Kong where I worked for a Chinese-language current affairs journal, I was able to closely follow both the unravelling and the reconstitution of the Maoist world and the era of the ‘Great Cultural Revolution’ 文化大革命, as it was often called.

Half a century later, it is sobering to hear the era of the Chairman of Everything Xi Jinping called by some independent commentators the ‘Minor Cultural Revolution’ 文化小革命. Like that terminology, it feels as though I, too, have come full circle; having witnessed the last years of the tragic past and the remarkable decades of transformation that followed, I, like so many of my old friends, associates and colleagues both in China and overseas, now contemplate the gradual slide of that country into the ignominy of the present.

In The Tyranny of History, the first part of this chapter, we illustrated our thesis concerning the weight of the Chinese past in the company of Yuan Li, Wang Lixiong and the historian W.J.F. Jenner. Here, in The Lugubrious Merry-go-Round of Chinese Politics, we continue by reprinting an interview conducted by the China writer and editor Jeremy Goldkorn in April 2022. Then, in an essay titled ‘They Can’t Burn All the Books’, we discuss the Chinese obsession with the short-lived Qin dynasty (221-206 BCE). Although it lasted a mere fifteen years, the Qin has exercised an influence over Chinese thought, politics and culture for well over two millennia. It continues to do so today. Following that, we reproduce a mini anthology of material from ‘Wheels’, the part of New Ghosts, Old Dreams in which a range of Chinese thinkers and writers wrestled with the topic of the cycles of history.

In the conclusion we offers three perspectives on that topic. The first is a somewhat upbeat message from Tiananmen, an eight-part TV documentary produced in Beijing in 1991 that was censored even before it could be screened. This is followed by another excerpt from Li Yuan’s conversation with Wang Lixiong in which the novelist discusses what will happen to China if and when monolithic Party control falters. In ‘Time’s Arrows’, the denouement of this chapter, I revisit a speech that I made at a conference convened in 1999 to discuss the fiftieth anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China.

***

In his role as head of the Communist Party’s Propaganda Department in the mid 1980s, Zhu Houze (朱厚澤, 1931-2010) promoted cultural liberalism and intellectual tolerance. When Hu Yaobang was purged and Fang Lizhi cashiered from the Party in January 1987, Zhu Houze was also removed. Demoted to a minor official role he was forced out again when Zhao Ziyang fell in June 1989.

Zhu remained a staunch advocate for political reform and the need for historical truth. In his later years, as the centenary of the Xinhai Revolution and the founding of the Republic of China approached, he made an observation about the cyclical nature of Chinese history, with a few caveats:

[In the century] from the Xinhai Revolution of 1911 to now, we have come full circle and return to where we started: autocracy. Our present autocracy, however, is far worse that anything in the dynastic past. The harsh way in which it controls is simply unprecedented and the means it uses to suffocate thought exceeds any earlier age. The cultural purges of the past are insignificant in comparison to it.

從辛亥革命到今天,我們轉了一圈,又轉回到了專制的起點,而且這個專制超過任何一個朝代,其控制的嚴酷前無古人,其對思想的鉗制超過歷代,相比之下,過去那些文字獄算不得什麼。

And that was in 2010!

***

My thanks to Linda Jaivin for graciously supporting the use of material from our book New Ghosts, Old Dreams: Chinese Rebel Voices here and to Reader #1 for reading the draft of this material and offering timely corrections.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

15 March 2024

Ides of March

***

Further Reading

Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium

- Prelude to a Restoration: Xi Jinping, Deng Xiaoping, Chen Yun & the Spectre of Mao Zedong, 20 September 2021

- Introduction 瞽 — You Should Look Back, 1 February 2022

- A Tally 單 — The Threnody of Tedium, 18 February 2022

- Chapter One 比肩 — We Need to Talk About Totalitarianism, Again, 31 March 2022

- Chapter Twenty-three — Chinese Time, Part I: 新鬼舊夢— More New Ghosts, Same Old Dreams, 1 January 2023; Part II: 忘卻的紀念 — the struggle of memory against forgetfulness, 2 January 2023

General

- Geremie R. Barmé, The Pirouette of Time — After the Future in China, 28 January 2019

- Geremie R. Barmé, Red Allure & The Crimson Blindfold, 13 July 2021

- Jianying Zha 查建英 & Geremie R. Barmé, The Spectre of Prince Han Fei in Xi Jinping’s China, 6 May 2021

- Translatio Imperii Sinici, China Heritage Annual 2019

- Du Mu 杜牧, The Great Palace of Ch’in — a Rhapsody 阿房宮賦, 25 February 2019

- Chan Koonchung 陳冠中, Sic transit gloria mundi — Ten Years of a Prosperous Age, 14 February 2019

- Liu Xiaobo 劉曉波, Bellicose and Thuggish — China Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow, 24 January 2019

- China’s Unfinished Twentieth Century, China Heritage Quarterly, Nos. 30/31, June/September 2012

- 1911: the Xinhai Year of Revolution 辛亥革命, China Heritage Quarterly, No.27, September 2011

- China’s Prosperous Age (Shengshi 盛世), China Heritage Quarterly, No.26, June 2011

- The Forbidden City, Harvard University Press, 2008

- The Rule of Dictatorship, The China Critic, 1934

On Chinese History

- F.W. Mote, Imperial China, 900-1800, Harvard University Press, 2003

- History of Imperial China, edited by Timothy Brook, Harvard University Press, six volumes, 2008-

- Ge Zhaoguang, What Is China? Territory, Ethnicity, Culture, and History, trans. Michael Gibbs Hill, Harvard, 2018

- Joseph R. Levenson, Confucian China and Its Modern Fate (1958-1965)

‘Ugh, here we are’

Australian sinologist, author, translator, and filmmaker Geremie R. Barmé first went to China in 1974. He’s seen a thing or two.

He’s written and edited a number of books on modern and traditional China, and held a variety of prestigious academic positions, most recently as the founding director of the Australian Centre on China in the World in Canberra. He is also an occasional contributor to The China Project, and an old friend of mine.

Geremie is the founding editor of China Heritage, where he is currently publishing a series of his essays on “Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium.”

We spoke by video call on April 7 [2022]. This is an abridged, edited transcript of our conversation, part of my Invited to Tea interview series.

— Jeremy Goldkorn, 8 April 2022

***

JG: Earlier this week, we published a translation of yours of a rant by a Shanghainese man captured on video, that circulated virally in China for a couple of days before being censored. The man looks to be in his late sixties or seventies, and he rails at quarantine workers in hazmat suits about the lockdowns in Shanghai, comparing them, unfavorably, with earlier periods of crisis in China’s 20th-century history.

Can you talk a little bit about why somebody would talk about the death of Máo Zédōng 毛泽东 and Dèng Xiǎopíng 邓小平 now, and compare it with the way he’s being treated in Shanghai in the lockdown?

GRB: Well, it’s a fairly typical way to frame things for people of that generation — he says he’s in his late 60s and he’s labeled as an ‘old man’. Guess we belong to the same era as I’m 67 myself and the way he puts things resonates with me, as much of my “China life” overlaps with aspects of his generation.

So, since he is of that vintage, it’s hardly surprising that hardline government control today immediately brings to mind other periods when the government has intervened in daily life in an outrageously invasive fashion. For example, the fellow starts off by mentioning sparrows. This is a reference to policies of the Great Leap Forward era of his youth when, since the nation was starving due to Mao’s botched “leap” in Communism, the call went up to eliminate sparrows and other pests that threatened already-depleted food stocks. Then he mentions other events, like the Cultural Revolution. He scoffs at the “Big Whites” in hazmat suits for trying to outdo the extremism of the Cultural Revolution, to put on a show of being more revolutionary than everyone else.

He also makes reference to the official histrionics surrounding the death of Mao — ‘the red sun’ — in 1976 and the demise of ‘the son of the people’ Granddad Deng’s in 1997. Listeners attuned to the political codes of China will immediately pick up what he’s saying about those two very different leaders. The speaker is mentioning these moments in history in a rhetorical way to make the point that even during those times of extreme national anxiety the authorities did not go over the top as they are in Shanghai right now. Sure, people behaved badly in the Cultural Revolution, but he’s saying what’s happening now seems even more extreme.

His ad lib comments are a reflection of what I think of as “totalitarian reflux.” A political acid reflux or an autoimmune response. He’s literally had a gutful and suddenly the memory of all those other stomach-churning meals comes welling up, the bile fills the mouth, you feel grossed out and you just have to vent.

This is what he’s doing; it’s a coping mechanism of a kind familiar to anyone who has experienced the policy cruelties of the past. What he’s saying to anyone who will listen is that we’ve all been through this kind of thing before, but you lot really are making a fist of it this time.

JG: Right. Right. Totalitarian reflux!

GRB: Here’s this guy, and from the video it looks like he’s in a fairly modest part of the city, and he’s probably not part of the booming Shanghai middle-class. But nonetheless, he lives in a place that’s proud of being China’s most hypermodern city and a global metropolis, and as he vents he makes it clear that he feels that it’s an incredible affront to be under the control of what he refers to as mere peasants — that is, the people brought in from outside of Shanghai to manage and control the outbreak, because the central government doesn’t trust the local authorities to act in an efficient fashion.

He refers to them in terms of the peasant army, the People’s Liberation Army, that surrounded Shanghai during the civil war that then forced its way in and “liberated” Shanghai from the Republican government.

He makes the comparison in a fit of pique because he’s affronted by what is going on; that Shanghai is being brought to heel once more. Throughout his comments, history provides immediate points of reference as he “uses the past to mock the present”(借古讽今 jiè gǔ fěng jīn), as the saying goes.

It’s common for people to use historical allusions and analogies to frame their views of the present. He’s also saying we’ve been here before and I’m making these comments to shame you and to express my outrage: You’re handling things as badly or even worse than in the past. It’s a rhetorical ploy; after all, he knows he’s being filmed and he’s playing to the camera as he vents. He probably also feels that he’s speaking out on behalf of many who are forced to remain silent and, from the fact that this clip circulated so widely so quickly in China, he’s probably right. One of the things about education under the Chinese Communist Party is that people are trained to perform, to be articulate and also to give voice to outrage; however, for the Communists it’s very unsettling when all of that training is used against them.

Anyone who has lived in China will have friends who have the gift of the gab and, in their mashups of contemporary life, can readily draw on history, contemporary politics, economics and what have you to entertain with a monologue.

By saying this, I don’t want to distract from the fact that this guy is frustrated and furious. He’s got a heart condition and, despite the anomalous fact that he takes a break to light up a cigarette, he remains furious; in part it is because he knows that countless others are also furious.

JG: Let’s put this in the context of what you’ve been writing about recently, a series for your website, China Heritage, on “the empire of tedium” of Xí Jìnpíng 习近平. Can you describe what you mean by that phrase?

GRB: The idea of tedium has to do with repetition, a return to the past, the obvious; it sums up the sense of boredom and monotony that to my mind has been a major feature of the Xi Jinping decade. It’s what in my student days we were taught about Engels and the historical dialectic: how chance and necessity are interwoven.

My ongoing series on Xi-era tedium reflects the sense I’ve had for many years that something like Xi and his reign were inevitable, even if that inevitability depended on a particular contingency, that is, the appearance of the kind of mission-driven, messianic ruler that we find in Xi Jinping.

After 1978, people tended to focus on how many policies of the High Mao era were re-evaluated or negated. I was always aware, however, that the Mao-Liu-Deng era policies of 1949 to 1966 were, apart from the Great Leap Forward, generally re-affirmed. The Maoist past saw the dual suppression of the working class (workers, peasants, etc) by the Party nomenklatura, and the suppression of the urban elites (managers, bureaucrats, business people, educators, the legal profession, media, etc), as the Communists expanded their power in Leninist-Stalinist style to invade every aspect of society.

For all of the cosmetic changes to China’s party-state, its essence, its modus operandi, though marginally challenged and even reformable, remained; as a result, what had happened in the autocratic past could happen again. “Dual suppression” has also been a feature of the Xi Jinping era. The laboring masses serve at the pleasure of the Party nomenklatura, which has been greatly strengthened, and once more the elites have been goose-stepped into complying with prerogatives of the party-state.

Now, this is all part of the ambience of tedium that I have been investigating; it is a handy term that I use to sum up a sense that many of my friends in the Chinese world, not just in China, but internationally, also have, a foreboding that had been welling up for years prior to the advent of Xi Jinping. Personally, I had little doubt about the glum future as soon as Xi got into power; it was also a shared sense among many people who, ten years ago at the advent of this tired old new era of Xi, were in their 50s or above. So many felt, “Damn it, here we go again!” Here’s the ugly desire to dominate, to control, to patronize, to manipulate, to repress and to silence.

Not to be too “China boomer” about this, but anyone who had lived through the last sixty years or so, will have seen the partial reforms from the late seventies, the potential and failures (as well as the lessons) of the 1980s, then the fitful repressions in the 1990s, followed by more circumscribed opening up and so on. It was easy to be dazzled by material changes and many found it boring to take all that Party palaver seriously. I did and, for the past decade, my sense of ennui has been paired with the sentiment that, “Ugh, here we are.”

This same old stuff, more extreme, more over the top; we will witness this for years to come and, as we all do, be it in China or outside, the old addiction to hope, hopium, part of the last four and a half decades of the “hopioid crisis” of China, will mean that huge amounts of time and effort will be devoted to ferreting out every sign of change, every possibility of transformation, reform and opening up, every scintilla of difference that can be detected in the obsidian surface of Party control. It’s boring; it’s understandable; it’s forgivable. And, for all of the ingenuity of scholars, analysts et al, it is also mind-numbingly tedious.

If the Chairman of Everything gets his third term in office, people will constantly be on the lookout for any hint that Xi might be aging, his hair whiter, his girth larger, his pallor paler; every burp and fart will be the subject of conjecture. It really takes me back, even as a teenager reading the papers in Sydney in the mid 1960s, there was constant speculation about Mao’s whereabouts and his health. There was a perpetual China crisis related to Mao and his inner circle. And it mattered because Mao had power over a huge and mysterious nation.

Now nearly 60 years later, speculation has been rife since 2018 regarding Xi Jinping’s plans, his status and his possible successor. Today, due to the economic heft and geopolitical ambitions of the Chinese party-state, the systemic instabilities that Xi Jinping and his courtiers have re-introduced to the country’s political life are of profound consequence.

[Note: See Wu Guoguang, Lessons from the black box of Chinese politics, The China Project, 3 October 2023.]

All the while, the Communists present this façade of unbelievable unanimity and monolithic unity. A decade ago, some Party thinkers and leaders tried to edge their way towards substantive change that would allow China to develop a kind of social maturity that was more concomitant with its impressive economic achievements. Instead, Xi et al prefer a state of paternalistic infantilization. Now, the whole world is also held hostage to the tedious panoply of the past.

The Shanghai debacle is but another example of Xi Jinping’s modus operandi, something that the Beijing academic Xǔ Zhāngrùn 许章润 analyzed in his February 2020 essay on the COVID crisis. China’s authoritarian leader who cosplays as a highly competent genius is an egotist who believes that he is History incarnate. The whole world has a front seat to the next crisis, the next round of instability. But, Xi has lots of company; as Gideon Rachman of the Financial Times has pointed out, this is after all “the age of the strongman.”

I began thinking about Xi’s empire of tedium around 2017. By then it was pretty clear that he would hope to enjoy term-less tenure. The veteran Hong Kong writer and political analyst Lee Yee (李怡 Lǐ Yí), who was my boss in the late 1970s, saw what was coming, as did Xu Zhangrun in Beijing. I followed and translated their work as part of my own endeavors to come to grips with the unfolding scenario. They, along with many others, were painfully aware that succession politics has bedeviled the Communists since they were founded in 1921.

JG: Beijing did seem to me to have, if not solved the question, at least found perhaps a more reasonable path forward from Jiāng Zémín 江泽民 and Hú Jǐntāo 胡锦涛. The way those two leaders came to power seemed to be both orderly.

During their rule, there seemed to be some responsiveness in the system, if not to the ordinary person on the street, at least to large parts of the Communist Party, rather than just a tiny group of people operating in a completely black box. Whereas now, we’re back in the old times. Is that the way you’re thinking about it?

GRB: There has only been one orderly transfer of power in over a century — that of Jiang Zemin’s hand over to Hu Jintao in 2003. Jiang Zemin himself got into power as the result of a coup against Zhào Zǐyáng 赵紫阳, just as Deng had been elevated to power as a result of an army led coup against the “Gang of Four.” Even Xi’s rise involved a power struggle with Bó Xīlái 薄熙来 and the purge of enemies. The politics of succession has been the bane of autocracies throughout history.

For people who are concerned about stability, whether it’s the stability of the markets, the economy, the real estate market, the stability of society, the succession issue is of outsize importance. Messianic self-belief has meant that Xi Jinping has re-opened the Pandora’s box of succession.

In 2017-18, the Communists collectively decided to throw China back into the cycle of uncertainty, one that has dogged the Party’s political history for a century.

That infuriated many but, for someone like me, I just feel ho-hum, here we are again. In 1992, in the wake of June Fourth in 1989, Linda Jaivin and I co-edited a book titled New Ghosts, Old Dream: Chinese Rebel Voices which looked at 1989 in the context of the previous century. One chapter, “Wheels” focussed on what Chinese thinkers and political activists had to say about the prison of history and cyclical return.

JG: How do you place China’s attitude toward the Russian invasion of Ukraine and its tacit and sometimes explicit support for Putin, in the context of the Chinese Communist Party’s early support from the Soviet Union, and the Soviet Union being China’s “big brother,” and then the Sino-Soviet split?

Here we are again, again, except this time, China’s the big brother, it would seem, but unable to articulate any kind of independent position on the war in Ukraine. It’s all about blaming America. Does this bring up for you any historical echoes?

GRB: Well, indeed. As you know recently, I published the first formal chapter in the series Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium, “We Need to Talk About Totalitarianism, Again.”

It’s a long rambling discussion of many issues to do with the problem of the Big T, totalitarianism. I frame the whole discussion in terms of the 100-year-long relationship between Russia/Soviet Union and China/the Chinese Communist Party.

Of course, most commentators rightly focus on what China is doing and saying right now, and why it’s doing and saying so in relation to Ukraine and Moscow. But I’m not a current affairs analyst, a journalist, nor am I an international relations expert. These transitory things are of current interest and, like most people, I follow them. Equally, like most others, I’m not equipped to comment on the why and wherefore of Beijing’s decision making. I am, however, interested in the broad historical context of contemporary events and, in that context, Beijing’s prevarications and calculations make a sense of their own, an internal and historical logic.

In discussions both of Russia and of China, it is popular to revisit Samuel Huntington’s views on the “clash of civilizations,” which had enjoyed considerable popularity following 9/11. I’ve never particularly agreed with Huntington’s caricatures of culture, civilization or history, but they have been used in significant ways. In China, they were quite modish after the events of 1989 in the context of China’s renewed cold war rhetoric and Communist-engineered “spiritual civilization.”

In the context of the Russia-Ukraine situation and China’s position, one is drawn back to the geopolitical, nationalist and ideological clashes that date back to the 1910s and the collapse/ reformation of empire following the violent termination of the Romanov dynasty in Russia and the abdication of the Manchu-Qing rulers of China.

In simplistic terms, both the Russian and Chinese empires, as well as the “transitio imperium,” that is, the legitimate transfer of power over former imperial territories, has been a process that has been underway for over one hundred years now. Of course, this is not limited to Russia or China, it is a process that continues to unfold among other former empires as well. This is the long tail of the twentieth century. To see contemporary events only in terms of the post-WWII world is to miss out much of the story. Both Putin and Xi Jinping have, in their very different ways, made this fairly obvious.

The Russia, China, America clash at the moment is one that has its origins in particular in that period. It’s a clash that’s an odd melange of the ideological, economic, cultural and racial. All that stuff about the Spiritual East and Decadent West — regardless of whether it comes from Putin’s coterie of fascist philosophers or Xi Jinping’s retrograde viziers — goes back to debates highlighted at the time of WWI and thereafter.

Of course, people are easily bored by all of this; if not, then they readily give in to what is known as historical or cultural determinism, a kind of lazy intellectual fatalism that is inherently static. However, when you see the Tsar-like Putin in his glorious isolation at the end of his priapic white conference table, or Xi Jinping in the guise of the Supreme Leader, it’s hard to ignore the shades of the past. Anyway, to do so is foolish.

In my work, I have over the years tried to explain that some of the tensions and ideas that seem merely to be of the moment have, in many cases, long historical roots; that political leaders, advised by a clutch of servile thinkers, are canny in manipulating long term grievances, ideological differences, and economic and social approaches to organizing life, not only to justify what they’re doing, but as a way of finding meaning for themselves and their regimes in the contemporary world. Again, this is by no means unique to Xi’s China, Putin’s Russia or, for that matter, Trumpian America.

All of this can be somewhat confounding for people who spend their time glued to screens obsessively following the second-by-second ructions of the market. It’s disconcerting, even rather retro and old-fashioned for these authoritarian leaders to be fixated on deep history and to believe somehow that their time has come. It somehow seems tacky and dated. Tough luck.

For some years Putin has been talking about reintegrating Russia and reviving holy mother Russia. For years Xi Jinping has been rabbiting on about “witnessing major changes unfolding in our world, something unseen in a century” (当今世界正经历百年未有之大变局). He’s used this expression over 40 times now; it’s actually a reference to the 1917 October Revolution that led to the creation of the Soviet Union.

JG: Which I think you pointed out in one of your essays. He first used that in 2017, right? The 100th anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution!

GRB: He used it in 2017. I remember at the time and, oh my God, this is what he’s talking about.

He’s used it again and again and again.

It is part of an integrated worldview. Whether one agrees with it and says that, oh, he’s just using it for a convenience, or whether this is a bit of historical showmanship, is to misunderstand that these are the ways that the Chinese Communist Party has painstakingly created a narrative for itself. It’s important to understand it, even if you find it abhorrent.

In the case of Putin, you need to read his July 2021 essay on Greater Russia and Ukraine. When he talks about holy mother Russia, the integrity of its geopolitical territory, the spirituality of its Orthodox Christian tradition and so on and so forth, you are in the land of the totalitarian. These are not merely the flights of fancy of an isolated autocrat. Similarly, Xi Jinping’s China Story has been crafted over many decades and it is underpinned by a form of revolutionary romanticism that melds elements of dynastic tradition with Stalino-Maoism.

JG: One last question, then. I’ve also been thinking about the filmmaker Michelangelo Antonioni, who went to China in 1970, 1971. He made a documentary film at the invitation of the Communist Party, and then was completely condemned for it after the film came out. Part of the reason I’ve been thinking about these things is that The China Project itself has been the subject of attacks by some young patriotic blogger nationalist thugs.

It seems to me there’s sort of an atmosphere in China, something that has been absent or at least has been toned down for the last 30 years or so, but it is coming back. It’s a certain particular type of hostility to the outside world, or perhaps it’s a hostility to anyone who tries to look at China and interpret it through a lens that is different from the way the Communist Party wants to see it. Does that make sense? How would you understand Antonioni and his treatment in China? Does that have any — not lessons — anything, any echoes today?

GRB: This is a question that really does take me back… Antonioni is never too far from my thoughts. The Italian director was invited to make a documentary in China in 1972, during the precursor of the country’s opening to the West. The film he produced — Zhongguo or Chung Kuo, Cina — was attacked by the enemies of the new Mao-Zhou policy and it was widely denounced, sight unseen.

In mid 1974, in my Chinese class in Canberra, we read the lead denunciation of the film that had been published in Red Flag magazine, the leading outlet for what passed as Communist Party theory back then. When the film was broadcast on Australian national TV shortly before I went to China as an exchange student in October 1974, the newly established Chinese embassy in Canberra went into rabid hyperdrive.

It was, to say the least, a “learning experience.”

Today’s wolf warrior diplomats still have quite a way to go before they can match the levels of high dudgeon and outrage perfected by the Maoists.

Anyway, the denunciation of Chung kuo stayed with me because many of the terms used at the time are trotted out, albeit without the past level of gusto, by the likes of Zhào Lìjiān 赵立坚 and Huà Chūnyíng 华春莹 today. Their tired lexicon is delivered with a kind of snide, curled-lipped hauteur that I find to be less than convincing. As for Antonioni’s film, it is still worth watching. It captures the rhythms and color of life in China that I experienced at the time. It is meditative, caustic and remains surprisingly moving. The people in it, sallow, malnourished, reticent and quiet, haunt the screen like ghosts.

Antonioni expressed a discordant view at a time when such a thing was absolutely verboten. In many ways, a similar situation exists in Xi Jinping’s China, although the masses haven’t been bludgeoned and starved into resentful submission; many revel in their subjugation to the Communists.

Nonetheless, the Xi Jinping New Era is a doleful time. Here is China, having achieved in the terms of its own modern history, unprecedented riches, hard-won (if draconian) social stability, extraordinary achievements in every major field of pursuit, yet it is as brittle, bitter, self-absorbed, and neurotic a nation as it has been at any other time since the end of the Qing dynasty.

The result is an incredible tragedy for humanity as a whole.

China cannot celebrate its achievements without at the same time denigrating anyone who might in any way question the means that have been used to realize these ends. A vast and majestic land is reduced to the sorry and pathetic scale of noxious self-regard. In many ways, the Cultural Revolution was a quintessential expression of the personality and worldview of Mao Zedong. Similarly, the pusillanimous, mean, reactive, bitter, aggrieved China of today reflects the personality of Xi Jinping and his fellow Politburo comrades, all of whom are creatures nurtured by High Maoism.

***

Source:

- Jeremy Goldkorn, ‘Ugh, here we are’ — Q&A with Geremie Barmé, The China Project, 8 April 2022

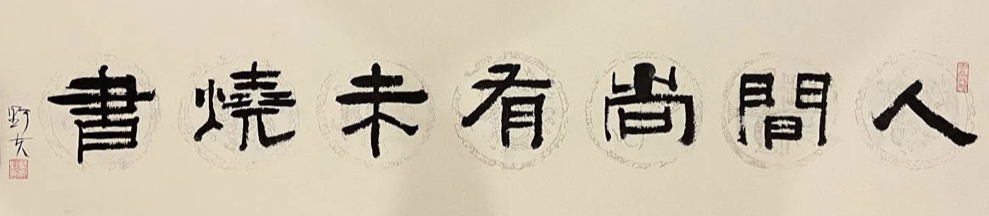

‘They Can’t Burn All the Books’

A Decades-long Obsession with the Qin Dynasty and its First Emperor

***

***

This work by a contemporary calligrapher features a line from a poem by Chen Gongyin (陳恭尹, 1631-1700), who composed it during the Ming-Qing cataclysm, the decades-long transition from the Ming dynasty to the Manchu-Qing empire. In full, the poem reads:

謗聲易弭怨難除,秦法雖嚴亦甚疏。

夜半橋邊哼孺子,人間猶有未燒書。

It may be easy to quell voices of protest,

But grievances are much harder to eliminate;

No matter how merciless its rule the Qin still missed some things.

Late at night by the bridge that young rebel still kept reading,

They can’t burn all of the [seditious] books.

Chen Gongyin was the son of Chen Bangyan 陳邦彥, a famous Ming loyalist who led the resistance to the Manchu-Qing invasion of South China in the 1640s. Captured in 1646, Chen the Elder was dismembered — 寸磔 cùn zhé — in public by his captors. Chen the Younger continued to support the Southern Ming resistance and, following its collapse, lived out his days in seclusion in Guangzhou.

The poem ‘On Reading Sima Qian’s Account of the First Qin Emperor’ 讀秦紀 has been quoted by rebels and resistance fighters ever since. In the Xi Jinping era, the line ‘they can’t burn all the books’ brings to mind ‘manuscripts don’t burn’, a famous line from The Master and Margarita, Mikhail Bulgakov’s celebrated novel about the devil’s visit to Stalinist Moscow. Bulgakov’s line inspired Manuscripts Don’t Burn, a 2013 Iranian film about an attempt to kill a busload of Iranian writers. Artworks are more readily destroyed than the spirit of resistance.

***

China has been obsessed with the First Emperor Qin Shihuang and his short-lived dynasty ever since it collapsed in 206 BCE.

In The Tyranny of Chinese History, Part I of this chapter, Bill Jenner observed that ‘the Qin had inherited a very old notion — that there could and should be only one legitimate central government — and taken it a lot further. This view has survived to the present day.’

As Jenner also notes about Mao Zedong, who would later be described as ‘Karl Marx plus Qin Shihuang’ 馬克思加秦始皇:

In one of his most revealing poems [‘Snow’ 雪 — ed.] he compares favourably the personalities of his age — by implication, himself — with the great emperors of the past: Qin Shi Huang, Han Wu Di, the founders of the Tang and Song dynasties and Genghis Khan. The final message of the piece is that none of them combined martial prowess with culture and sheer style in the way he did. This poem was written in 1936, when the Communists controlled only a small and backward corner of China, far from the centres of wealth and power. Yet already he was thinking like an emperor.

[Note: For more on ‘Snow’ and Mao’s imperial style, see For Truly Great Men, Look to This Age Alone, China Heritage, 27 January 2018. And, on Qin Shihuang and Xi Jinping, see The Heart of The One Grows Ever More Arrogant and Proud, 10 March 2020]

Mao expressly, and repeatedly, identified with China’s history of rebellion, and in particular with upstarts who founded dynasties (Qin Shihuang was an exception). He declared that this latest uprising, led by a proletarian vanguard and directed by visionary revolutionary leaders with a modern anti-feudal political philosophy like himself, would break the dynastic cycle forever and found a new government that would outshine in achievement all the greatness of the past.

On 4 July 1945, Mao Zedong asked the educator and progressive political activist Huang Yanpei (黃炎培, 1878-1965) what he had made of his visit to the wartime Communist base at Yan’an in Shaanxi province. Huang lauded the collective, hard-working spirit evident among the Communists and their supporters, but he doubted whether their wartime frugality and solidarity could last. He predicted that the revolutionary ardour of the Communists would inevitably wane if they ended up in control of China and he wondered out loud whether the endemic political limitations and blemishes of earlier Chinese regimes would return to haunt the new one, despite the best efforts of its committed idealists.

Would autocracy, cavalier political behaviour, nepotism and corruption once more come to rule over China? Huang said he could see no way out of the ‘vicious cycle’ of dynastic rise and collapse, the ‘historical cycle’ 歷史週期率 lìshǐ zhōuqīlǜ, though he certainly hoped that Mao and his followers would be able to break free of the wheel of history. Mao responded unequivocally:

We have found a new path; we can break free of the cycle. The path is called democracy. As long as the people have oversight of the government then government will not slacken in its efforts. When everyone takes responsibility there will be no danger that things will return to how they were even if the leader has gone.

***

***

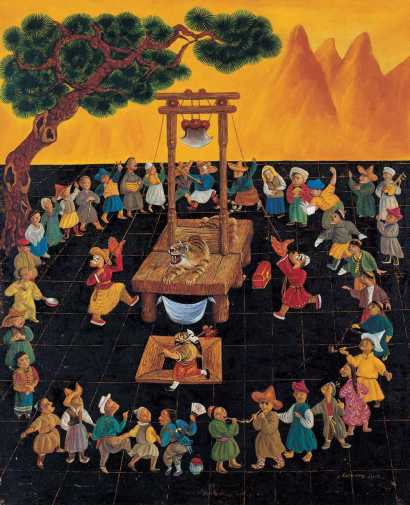

The popular 1988 television documentary River Elegy 河殤, which was pointedly critical of the inward-looking legacy of the Qin dynasty, was followed in August 1990 by an official made-for-TV riposte, On the Road: A Century of Marxism 世紀行.

On the Road was the first mass media work of propaganda to introduce Chinese audiences to the Mao Zedong-Huang Yanpei exchange at Yan’an in 1945. It did so at the height of the Counter-Reform Era of 1989-1992, a period that in Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium we repeatedly refer to as the Prelude to the Xi Jinping Restoration.

In December 2012, shortly after becoming Party General Secretary, Xi Jinping first referred to what was now called the Mao-Huang ‘cave reply’ 窯洞對 yáodòng duì himself, and it has been a feature of his remarks on Chinese history, corruption and China’s future ever since. The First Emperor of the Qin also enjoyed renewed prominence in the nation’s political discourse.

In 2018, seventy-three years after Mao met with Huang Yanpei in Yan’an, Xi Jinping was acclaimed the unquestionable leader of the People’s Republic of China; his role was hailed as 定於一尊 dìng yú yī zūn, ‘The Ultimate Arbiter’ — an ancient imperial epithet famously used to describe the unchallenged power of Ying Zheng (嬴政, 259-210 BCE), Qin Shihuang, the First Emperor of the Qin. Only months earlier, Xi had been bestowed with the equivalent of lifetime tenure as chairman of the country’s party-state-army. Mao’s bold claim that the Communist Party would break the cycle of Chinese history was now up for debate.

As we noted in China Heritage Annual 2019, the theme of which was Translatio Imperii Sinici — ‘the transhistorical nature of Chinese imperial power’ — ever since the collapse of the last dynasty in 1911, ‘Empire’ — or 帝業 dì yè, ‘the imperial enterprise’ in traditional terms — has been a source of anxiety for China’s political leaders, revolutionaries, thinkers, business people, journalists and citizens. Sun Yat-sen, the revolutionary leader who became first president of the Republic of China, warned that even some of the revolutionaries around him regarded the restoration of dynastic rule and empire was inevitable. Sun said:

In China there has for the last few thousand years been a continual struggle around the single issue of who is become emperor! 中國幾千年以來,所戰爭的都是皇帝一個問題。

For his part, Mao Zedong, regardless of his own imperial airs, was obsessed with the possibility of a restoration, 復辟 fù bì, of the ‘semi-feudal and semi-capitalist’ past. After the Communist state of the People’s Republic of China, history, and how it was recounted according to Party dogma, was a central feature of national life.

Documents related to the failed coup in 1971 referred to Mao as ‘Qin Shihuang’ and one of the most striking lines that featured during the mass protests in Tiananmen Square in April 1976 was:

China is not the China of the past and The People are not irredeemably ignorant. The era of Qin Shihuang has gone forever. 中國已不是過去的中國,人民也不是愚不可及,秦皇的時代已一去不返了。

Since Mao’s death in 1976, Party leaders, thinkers and historians have recalled the Chairman’s 1945 exchange with Huang Yanpei, and they have been increasingly obsessed with the issue of 興衰 xīng shuāi, ‘the rise and decline [of rulership]’, an expression famously used by Sima Qian (司馬遷, 145-? BCE), the Grand Historian of the Han dynasty, to describe the waxing and waning of political fortunes.

***

The obsession with the Qin dynasty and the First Emperor has by no means been limited to Mao Zedong and Xi Jinping. Jiang Zemin, Deng Xiaoping’s successor, is said to have urged Zhang Yimou to make Hero (英雄, 2002), a cinematic blockbuster and an unabashed paean to the founder of China’s first dynasty. The film ends with a panoramic view of the rising sun and the Great Wall winding over undulating mountain landscape. A subtitle declares:

‘In 221 BC, after the King of Qin unified China he put an end to warfare and constructed the Great Wall to protect the state and the people. He was China’s first emperor and is known to history as Qin Shi Huang.’

公元前二二一年,秦王統一中國後,結束戰爭,修建長城,護國護民,成為中國歷史上第一個皇帝,史稱秦始皇。

Jiang reportedly saw himself as something of a latter-day grand unifier and we should remember that it was under Jiang that the People’s Republic began its informal ‘imperial reorientation’. As the economy boomed, the capital Beijing was redesigned to emphasise once more the north-south axis of the Ming-Qing imperial city, something that featured in the opening ceremony of the Beijing Olympics in August 2008. Jiang also had symbolic structures like the Altar to the New Century 中華世紀壇 built that imitated design motifs of the Forbidden City.

During Jiang’s tenure as party-state-army leader the topic of the rise and fall of empires were discussed during the in-house seminars on history and the future of China at which hand-picked scholars addressed members of the ruling Politburo. The tombs of legendary rulers and sage leaders were lavishly reconstructed and annual ceremonies held to commemorate the eternity of Chinese governance. In a myriad of ways, Jiang who, like Xi Jinping, was advised by the Party theoretician-historian Wang Huning, wove mythology and dynastic history into the fabric of contemporary China. It was a process that continued apace, and with ever greater official largesse, during the Hu Jintao decade (2003-2012).

Opponents of imperial revivalism also used old tropes to criticise Party leaders who would combine the dynastic past and Stalino-Maoism with the economic exuberance unleashed by Deng Xiaoping. Over the years, writers frequently referred to an essay by fourth-century poet Tao Yuanming 陶淵明 in which he described a secluded idyl created by people who had ‘fled the chaotic rule of the Qin’ 避秦時亂 bì Qín shí luàn. Hong Kong critics of Beijing reminded people that generations of mainland refugees had escaped from ‘the harsh rule of the Qin’ 避秦苛政 bì Qín kè zhèng and contributed to making the British colony into a place where they could enjoy economic and personal freedoms unknown in the People’s Republic.

As he rose to power in 2011-2012, some of Xi Jinping’s old friends who acted as something of a ‘kitchen cabinet’ are said to have frequently discussed dynastic history with the new leader — the reasons behind the longevity of certain imperial houses, the fate of particular emperors, the intermeshing of China’s millennia-long history with Marxist-Leninist views about historical inevitability, and so on. Speculation centered on Xi’s upcoming reign and his place in history. It is impossible to ignore the imperial reverberations in Xi Jinping’s bloated oeuvre of speeches, remarks and essays. It is said that Mao’s mindset was determined by 帝王思想 dìwáng sīxiǎng, an emperor’s frame of reference. Only time will tell whether Xi Jinping, a man who would outshine Mao, has can be as successful in ‘the art of autocracy’ 帝王之術 dìwáng zhī shù as his predecessor.

Throughout the Xi era, both ruler and ruled have repeatedly drawn on the lessons of the Qin and the First Emperor to castigate the present and warn about the future. And, apart from the ruler and his dissolute successor, the man who led a rebellion against the Qin has also haunted Chinese leaders. For decades, the uprising of Chen Sheng 陳勝 was even part of the school history curriculum. Until February 2019, that is, when it was reported that the famous account in Han-dynasty historian Sima Qian’s Historical Record had been removed from text books. No reason was given.

Elsewhere we have noted that both Xi Jinping and Xu Zhangrun, his most intractable critic, have been given to quoting The Great Palace of Qin 阿房宮賦, a famous account of the destruction of the legendary Epang Palace of Qin Shihuang written by the Tang poet Du Mu (杜牧, 803-852). Arguably the best-known poem on the cycles of Chinese history, it contains the immortal lines:

The Rulers of Ch’in had not a moment

To lament their fate,

Those who came after

Lamented it.

When those who come after

Lament but do not learn,

Then they too will merely provide

Fresh cause for lamentation

From those who come after them.

秦人不暇自哀

而後人哀之

後人哀之

而不鑒之

亦使後人

而復哀後人也。

Both Xi Jinping and Xu Zhangrun have quoted these lines as a warning — those who do not learn from history will be condemned to repeat it.

1. Wheels & The Mysterious Circle of Mao Zedong

In the mini-anthology below, we feature material drawn from ‘Wheels’, Part IV of New Ghosts, Old Dreams: Chinese Rebel Voices. In our editorial introduction Linda Jaivin and I wrote:

The traditional Chinese worldview saw history as a cyclical development: dynasties were founded, flourished, and then, growing corrupt, fell into decline, to be overthrown and replaced by a new imperial house that would then repeat the cycle.

Although historians have shown this to be an overly simplistic, even fallacious, view, the notion of cycles still has a potent grip on the Chinese imagination, one further strengthened by the television series River Elegy and the “historical” writings of authors like Jin Guantao.

There are all kinds of cycles, or wheels. They can be found in the supposedly immutable alternation of order and chaos [or, as Liang Shuming put it: 循環於一治一亂而無革命], in the traditional calendar, which represents time as a series of sixty-year cycles (with years of danger and calamity, such as the Year of the Dragon [in 1988-1989, and again in 2024-2025]), and in the Buddhist doctrine of reincarnation within the Wheel of Life. (A common pre-May Fourth curse was “May you fall into the wheel!”) In “Wheels” we attempt to illustrate several cycles related to the events of the late 1980s; cycles to which many of those involved in the r989 Protest Movement felt themselves bound.

The wheel of protest, denunciation, and self-flagellation has been revolving in China since 1949. Each new political movement—and there have been dozens of them, as Wu Zuguang comments in his speech “On China’s National Characteristics”—represents another turn of that wheel. …

The 198os also saw the recycling of the old debate concerning China’s “national characteristics” and the revival of interest in China’s “national essence” …

In applying the heavy hand of “order” to quell what it perceived as unbearable “chaos” in 1989, the party was itself following a pattern thousands of years old. Just as the first Qin emperor, Qin Shihuang, had responded to criticism by killing his critics and burning their books, so too did the government of Deng Xiaoping, Yang Shangkun, and Li Peng react to the petitions and pleas for dialogue with bloodshed and censorship. …

In Part II, “Bindings,” we saw how both reformers and individualists have tried to break free of the cycle of history, sometimes with fatal consequences. Often they have ended up “rediscovering the wheel”: The essays and polemics of Li Ao, Bo Yang, Liu Xiaobo, and others repeat and reformulate the concerns of leaders of the 1898 Reform Movement and the May Fourth generation. …

The attraction of the wheel—these cycles of history—is both subtle and insidious. It causes people to think that change is impossible, that progress is a dream, and that the future is reflected in nothing so much as the past. After all, the traditional aim of each revolution, each turn of the dynastic wheel, was not to progress into the future but to pursue a dream of returning to the Golden Age of the past. The belief in the cycles of history itself is tyrannic, for it feeds a gloomy fatalism that serves the status quo.

***

***

The Mysterious Circle of Mao Zedong

Liu Yazhou

It was three days before his death, and Mao Zedong could no longer talk. He put his thumb and forefinger together to form a circle and showed the doctors and nurses. Then, afraid they hadn’t understood, he lifted his arm with great effort and traced a circle in the air.

But what did it mean? Was this some mysterious cipher? A prophecy? In the last days of his life, he bequeathed a riddle in the shape of a circle to his empire.

The doctors panicked. Hua Guofeng, Wang Dongxing,* and the rest rushed to his bedside. They tried to work out what he meant, like children playing a guessing game. Jiang Qing came as well, but not even she knew what her husband’s gesture signified… .

* Hua was to be Mao’s successor as party chairman, Wang was head of security.

I don’t understand what he meant, either. No one will ever know for sure. But if you ask me, I’d say he was describing his own history.

History is circular.

Everything is circular.

Isn’t that so?

He began in Tiananmen Square, and that’s where he ended up. He had traveled in a big circle.

He returned to Tiananmen Square, never to leave again. He became the square’s resident in perpetuity, its only resident… .

The largest tomb in the modern world was erected on Tiananmen Square. But it’s not really a tomb. It’s a spacious, resplendent villa. It has a white marble armchair inside. You can see it when you enter the main hall. There’s a bed, too, and that’s where you’ll find him. The place is air-conditioned and has an elevator. In the morning the elevator takes him up to the hall where he works, and at night it lowers him to the depths where he sleeps.

Mao Zedong presides over Tiananmen Square. He is forever observing his people, and the people are forever watching him, ever mindful of his Thought. No matter how you look at it, he is immutable.

Mao Zedong, male, from Xiangtan County, Hunan Province, 1.78 meters tall, born of a rich peasant family.

This passage concludes the book The Square — Altar for an Idol by Liu Yazhou [廣場——偶像的神壇], which was published in Hong Kong in early 1990. The thirty-seven-year-old novelist is the son-in-law of Li Xiannian, China’s former state president.

Another popular explanation for the “mysterious circle of Mao Zedong” is that the dying chairman was trying to tell those around him to work together and not to purge one another after he was gone. If so, no one paid any attention.

[Note: Liu Yazhou (劉亞洲, 1952-) also features in 蔭 — Shadows of 1644, Chapter Five of Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium, which focusses on another historian obsession of the Communists, the failed peasant rebellion of 1644. Liu was a well-connected army writer who suddenly disappeared in 2021. Known to be an outspoken opponent of Xi Jinping within the Party elite, people were not surprised to learn that he was secretly tried on charges of corruption and supposedly handed a suspended death sentence, which in practice is the equivalent of life imprisonment. In early 2023, Party Central reportedly ordered the withdrawal of Liu’s work from circulation and the elimination of his ‘malign influence’ within the army.]

***

2. Never Say Never

Bo Yang

The violent suppression of the Protest Movement took many observers by surprise. For years, the Chinese had been assuring one another— and foreigners — that the Cultural Revolution, or any similar regime of repression and terror, could never recur in China. Bo Yang, however, thought differently, as is shown by what he wrote after his return to Taiwan from a trip to the mainland in 1988.

[When traveling on the mainland] we often heard people say that a violent upheaval like the Cultural Revolution could not occur again in China. They reasoned that people had suffered more than enough and would be on their guard in the future.

I hold precisely the opposite view. I believe that an upheaval could erupt at any moment, even though it might go against the trend of the times—indeed, against human nature itself—just like the Cultural Revolution. What people really mean when they say it “couldn’t happen again” is that it’s impossible for the old actors to take to the stage again: Madame Jiang Qing reappearing on the rostrum to harangue the crowds, Mao Zedong popping up on Tiananmen Gate to egg on the Red Guards. Of course that couldn’t happen. History doesn’t replay itself like that. But the crux of the matter is that any soil in which poisonous weeds have flourished in the past can surely produce more poisonous weeds; as long as the factories for manufacturing Cow Demons and Snake Spirits [An expression used in the Cultural Revolution to describe counterrevolutionaries and other political criminals] still exist, they will be able to produce more Cow Demons and Snake Spirits. In Mainland China the soil and the factories are intact. It’s just that they’re temporarily out of order due to extreme overwork. But the moment ambitious men are once again inspired, disaster will revisit the land.

The government’s policy has been to encourage forgetfulness, and, indeed, the people themselves have already pushed the Cultural Revolution out of their minds. The most chilling phrases one hears on the lips of Chinese people are “Just forget it!” and “Let bygones be bygones!” These sayings will be the downfall of the Chinese people. Superficially they would appear to be the voice of a generous spirit; in fact, they cloak profound fear. At the Nazi concentration camp at Dachau, there’s a plaque on which is engraved the following warning [by George Santayana]: “Those who do not remember the past are condemned to relive it.” The same is true of Mainland China: As soon as people forget the calamity of the Cultural Revolution, it will be sure to happen again! We won’t have to wait until the 1990s either—the eighties have already given us the Anti-Spiritual Pollution Campaign and the Anti-Bourgelib Campaign. Even the television newscasters felt compelled to put on Mao jackets during those movements. Those two campaigns petered out only because the leaders exercised some self-restraint, not because the people opposed them.

Ba Jin once proposed the establishment of a “Cultural Revolution Museum,” [see Seeds of Fire, pp.381-84], a suggestion that elicited an enthusiastic response from people around the country and energetic opposition from officialdom. In any standoff between the people and the officials, the people always lose. The goal of the authorities has been to make people forget the wounds they’ve received. This is just another example of the curious workings of the official mind.

What’s even stranger is that right up to the present day, the People’s Government still insists on upholding Mao Zedong Thought, but because even they have some sense of shame, they hasten to explain that “Mao Zedong Thought has nothing to do with Mao Zedong himself!” This is the sort of absurd logic to which only the Chinese dare resort— the officials who came up with this twisted logic, however, are probably convinced that other people are as stupid as they are.

***

3. On China’s National Characteristics

Wu Zuguang

Wu Zuguang made the following speech on March 22, 1989, at the National People’s Political Consultative Congress in Peking.* Wu had been forced to resign from the party in 1987 as part of the campaign against Bourgelib, although he retained his non-party posts such as the vice chairmanship of the China Dramatists’ Association. His outspoken criticism of censorship in the arts and political purges had for many years infuriated such leaders as Vice President Wang Zhen . After his resignation, Wu became even more critical of the government and began addressing such basic issues as the political system itself.

I wonder how many comrades attending this congress have ever really delved into the daily life of the nation? How many of you have ever come into close contact with the people, been jostled on public buses, for example, or elbowed your way into the shops and markets, squeezed up to the bookstalls, or crowded into restaurants—really tasted the whole range of flavors that makes up Chinese life? How much do you know about what concerns people today? Of course, the people have no end of concerns: inflation, students’ lack of interest in their studies, the hardships suffered by teachers, the enviable fortunes made by official and private speculators alike. They are perturbed by the rapid decay of public morality and the ever-increasing corruption of the privileged class…. They are also concerned as to whether leaders in the Center are really capable of understanding popular sentiment. Popular sentiment is, in short, the sentiment of the nation.

But what I want to talk about today is the subject of guoqing [國情], “national characteristics.” This is because I have heard the expression used three times recently. The first was when Fei Xiaotong, the vice chairman of the National People’s Political Consultative Conference [and a famous sociologist], used it a few months ago. The second time was last month in a comment by General Secretary Zhao Ziyang. Most recently it was used in mid-March by Yuan Mu, the spokesman for the State Council. On all three occasions the speakers were using the term “national characteristics” to deny that the Western multiparty system and parliamentary politics could be imported to China. They all gave the same reason: the Western political setup is not suited to China’s national characteristics.

I was born after the elimination of feudal rule from China. I have lived through the internecine warfare of the warlords, the success of the Northern Expedition, the autocratic rule of the Nationalists, the eight years of the Anti-Japanese War, the three years of the War of Liberation, and the appearance of a liberated New China.

The birth of the People’s Republic of China was the glorious achievement of the Communist Party of China. It saved the people of China from the distress and suffering of the past century, leading them into a new, peaceful, and happy world. During the exhilarating days that followed the establishment of the People’s Republic, I was so intoxicated with joy that I would even wake up in the middle of the night laughing. The nation seemed the picture of prosperity, and I contemplated the future of our great motherland with boundless optimism. Comparing the past with the present, the people of China were so grateful to the party and Chairman Mao that we worshiped them to the point of fanaticism. …