Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium

An Announcement

陰魂不散

Mao Zedong was born on 26 December 1893.

At a banquet organised to celebrate the occasion in Zhongnanhai in 1966, the seventy-three year old Mao is said to have raised a glass to toast the ‘all-out civil war’ 全面內戰 that he and his revolutionary comrades had engineered that year (see 戚本禹回憶錄).

For decades, 26 December has been celebrated by disparate groups, some of which gather at Mao’s birthplace in Hunan province. In 2009, Mao Xinyu, Mao’s only grandson, submitted a formal proposal for the day to be declared as a national public holiday. The ensuing discussion also focussed on what the day might be called. These included ‘Eastern Saints Day’ 東聖節,’The Festival of the Masses 百姓節 and ‘People’s Festival’ 人民節. It is most commonly referred to as ‘Mao’s Birth Day’ 毛誕節 (see 毛粉瘋「毛誕」, 自由亞洲電台, 2021年12月27日, and for the celebrations in 2022, see here and here.)

***

The 26 December 2023, one year from today, will mark the 130th anniversary of Mao Zedong’s birth. A little over a month prior to that, on the 22 November 2023, Xi Jinping will celebrate an important milestone in Maoist history — the Chairman’s 22 November 1963 directive on The Maple Bridge Experience 楓橋經驗.

As China confronts the murderous Covid chaos resulting from the most egregious Mao-like act of Xi Jinping’s baleful decade in power, we acknowledge Mao Zedong’s birth and note the significance of Maple Bridge. In this addition to Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium, we are also announcing that the present series will continue into 2023 thus making this issue of China Heritage Annual into a double issue covering the years 2022 and 2023.

We will start the 2023 anniversary year with a chapter titled ‘The View from Maple Bridge’. The introduction to that three-part chapter will mark the fortieth anniversary of the resurrection of The Maple Bridge Experience in 1983. Launched at the behest of Deng Xiaoping and his fellow veteran comrades, the ideologically based policing campaign of that year evolved to become a model of social and political control that has been updated and enhanced ever since. As a result, the Maple Bridge Experience has been both a hallmark of life in post-Mao China and a central feature of Xi Jinping’s rule.

— Geremie R. Barmé, Editor, China Heritage

Distinguished Fellow, Asia Society

26 December 2022

毛誕節/ Boxing Day

***

Further Reading:

- Prelude to a Restoration: Xi Jinping, Deng Xiaoping, Chen Yun & the Spectre of Mao Zedong, China Heritage, 20 September 2021

- Geremie R. Barmé in conversation with Susan Shirk, Interpreting the Xi Dynasty, UC San Diego, January 2020

- A Hosanna for Chairman Mao & Canticles for Party General Secretary Xi, 22 October 2022

- When Zig Turns Into Zag the Joke is on Everyone, 12 December 2022

- In My End is My Beginning — Chairman Xi’s New Clothes, 13 December 2022

- Ever More Arrogant & Proud — Xi Jinping’s Rule in the End-time of Covid, 14 December 2022

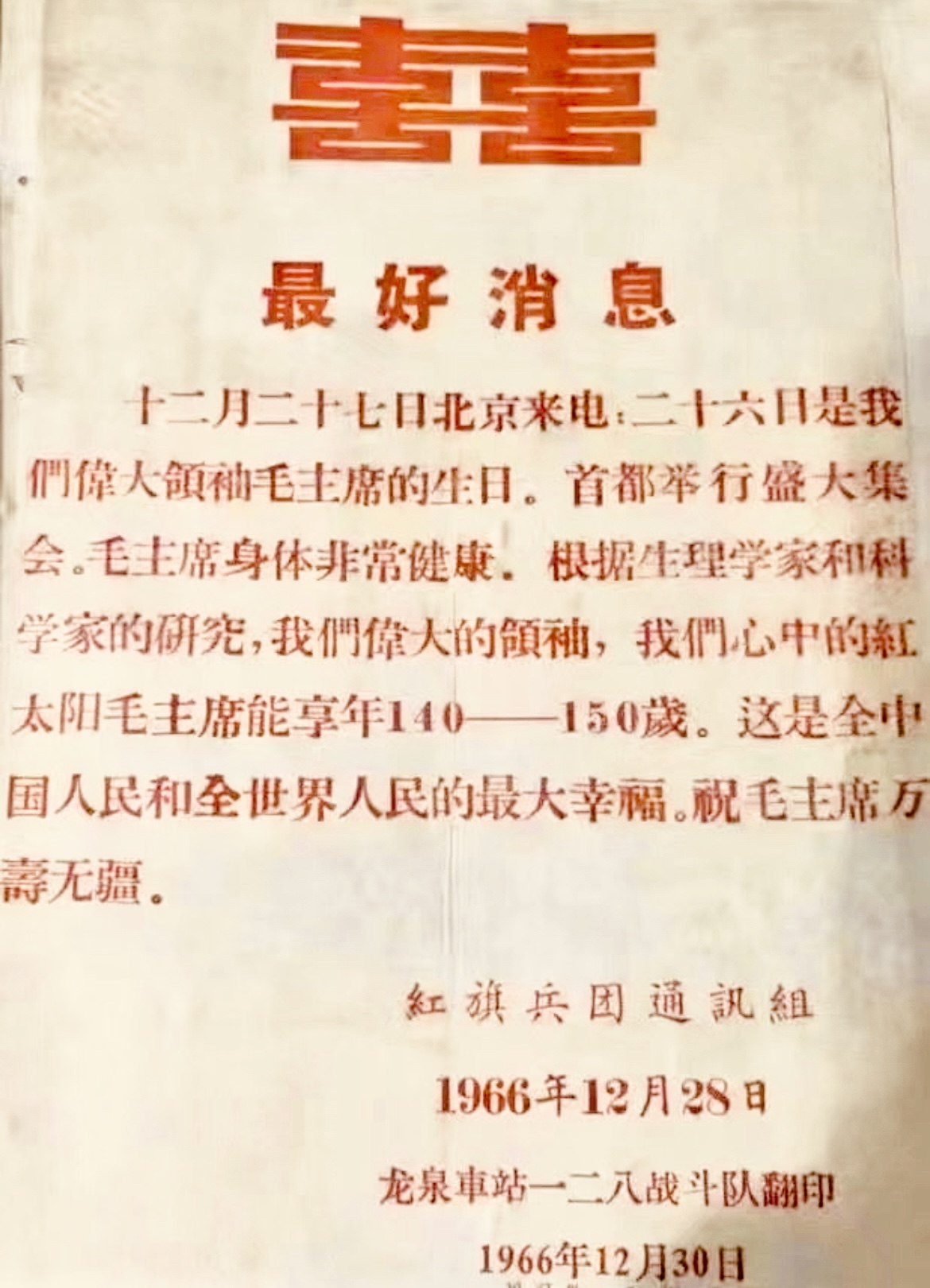

Around the time that Mao Zedong celebrated his seventy-third birthday and raised a glass to the civil war that he had engineered, Marshal Ye Jianying 葉劍英, one of the founders of the People’s Liberation Army, told a group of Red Guards that advances in medicine would enable Mao to live to 150. Above is a Red Guard circular from late December 1966 announcing that ‘best possible news’ 最好消息. Mao died ten years later in September 1976 and Ye Jianying oversaw the arrest of his widow, Jiang Qing, and her radical associates.

***

Shades of Mao

In April 1994, the Fairbank Center for East Asian Research, Harvard University held ‘Mao Craze, Mao Cult? A Symposium on Popular Culture in China Today’. On 23 April 1994, I presented a paper on the theme of ‘The Irresistible Fall and Rise of Mao Zedong’. The title was inspired by Bertolt Brecht’s 1941 ‘parable play’, The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui‘. In my presentation I argued that the popular Mao cult that had flourished in the wake of the bloody repression of the 1989 Protest Movement was a mixture of nostalgia, resistance and misplaced ideological fervour. I also suggested that, despite all of the cosmetic changes to the political and social life of post-Mao China, Maoist habits, ideas, language and politics remained the bedrock of contemporary China.

The paper I presented at Harvard formed the basis of the introduction to my book Shades of Mao: The Posthumous Cult of the Great Leader (1995). There I observed that:

The shade of Mao Zedong continues to cast a long shadow over Chinese life. Although the MaoCraze of the early 1990s has faded, replaced, for example, by such things as a passing fashion for late-Qing heroes like Zeng Guofan, some discussions of Mao and his legacy have continued in the public arena. Wang Shan’s China Through the Third Eye, a controversial best-seller in China in the summer of 1994, took as its central theme a comparison between the Mao and the Deng eras, often expressing sympathy if not outright support for Maoist policies. One of the constant refrains of the book was that the Chinese have failed to understand and appreciate Mao fully!

Meanwhile, outside China the publication of Li Zhisui’s magisterial memoir in late 1994 elicited a new wave of debate about the Chairman, and his place in the nation’s history, among overseas Chinese, especially within the dissident diaspora, and the Chinese version of the book was much sought after on the Mainland. Committed intellectuals continue to debate the heritage of Mao, and many are concerned that the Mao heritage, reformulated by an ideologically bankrupt Party in terms of a crude nationalism, may be a dangerous factor in China’s future. To paraphrase William Bouwsma, however, Mao, much like water and electricity, is now a public utility. …

I concluded the introduction with the observation that:

‘Chinese cultural history, like that of many nations, is rich in examples of objects, symbols, and individuals who have been “lost and refound, overvalued, devalued, then revalued.” The battle for China’s past, over Mao’s reputation and the history of the Communist Party, will continue in both the public forum and among archivists and scholars in and outside China. One day Chinese readers will gain access to that unfolding past. In the meantime, Chairman Mao has entered the stream of Chinese history as man, icon, and myth, and there is little doubt that the Cult of the early 1990s is only the first of the revivals he will experience in what promises to be a long and successful posthumous career.’

A number of the other participants in the gathering at The Fairbank Center at Harvard University in April 1994 scoffed at my suggestion that the popular Mao cult, and even elements of Mao Thought and the Maoist tradition in Chinese politics, would continue to play a significant role in Chinese life. These noted scholars were my seniors both in years as well as academic standing — at the time, I was a mere postdoctoral fellow at The Australian National University in Canberra working in Boston part-time with a small documentary company on a film that would eventually be released under the title The Gate of Heavenly Peace. After my session, two senior scholars privately dissented from their colleagues. They were Lucien Pye and Benjamin Schwartz.

The Berlin Wall had fallen in 1989, the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991 and, with the end of the Cold War, Francis Fukuyama had announced ‘the end of history’. America, attended by its western allies, was embarking on its ‘unipolar moment’ as the world’s unchallenged superpower.

I disagreed with my esteemed colleagues at the time, and I have continued to do so ever since. Just as Mao Zedong went to ‘meet Marx’, they too have now all gone to meet their various makers. However, the shade of Mao continues to cast a long shadow over Chinese life and, under Xi Jinping, over the whole world.

***

The Shade of the 2020 Gengzi Year in 2022

A ‘gengzi year’ 庚子年 occurs in the thirty-seventh year in the traditional sixty-year lunar calendrical cycle. In modern times, and in the popular imagination, ‘gengzi years’ are associated with disaster and hardship: the gengzi year of 1840 coincided with the First Opium War with Britain; 1900 was the year of the Boxer Rebellion, discussed below; and 1960 marked a particularly harrowing period during the Great Famine that followed the Great Leap Forward.

As a mysterious new virus spread in China from February 2020, writers like Xu Zhangrun and Zi Zhongyun noted the portentous significance of the latest Gengzi Year (see Xu Zhangrun 許章潤, Viral Alarm — When Fury Overcomes Fear, 24 February 2020; and, Zi Zhongyun 資中筠, 1900 & 2020 — An Old Anxiety in a New Era, 28 April 2020).

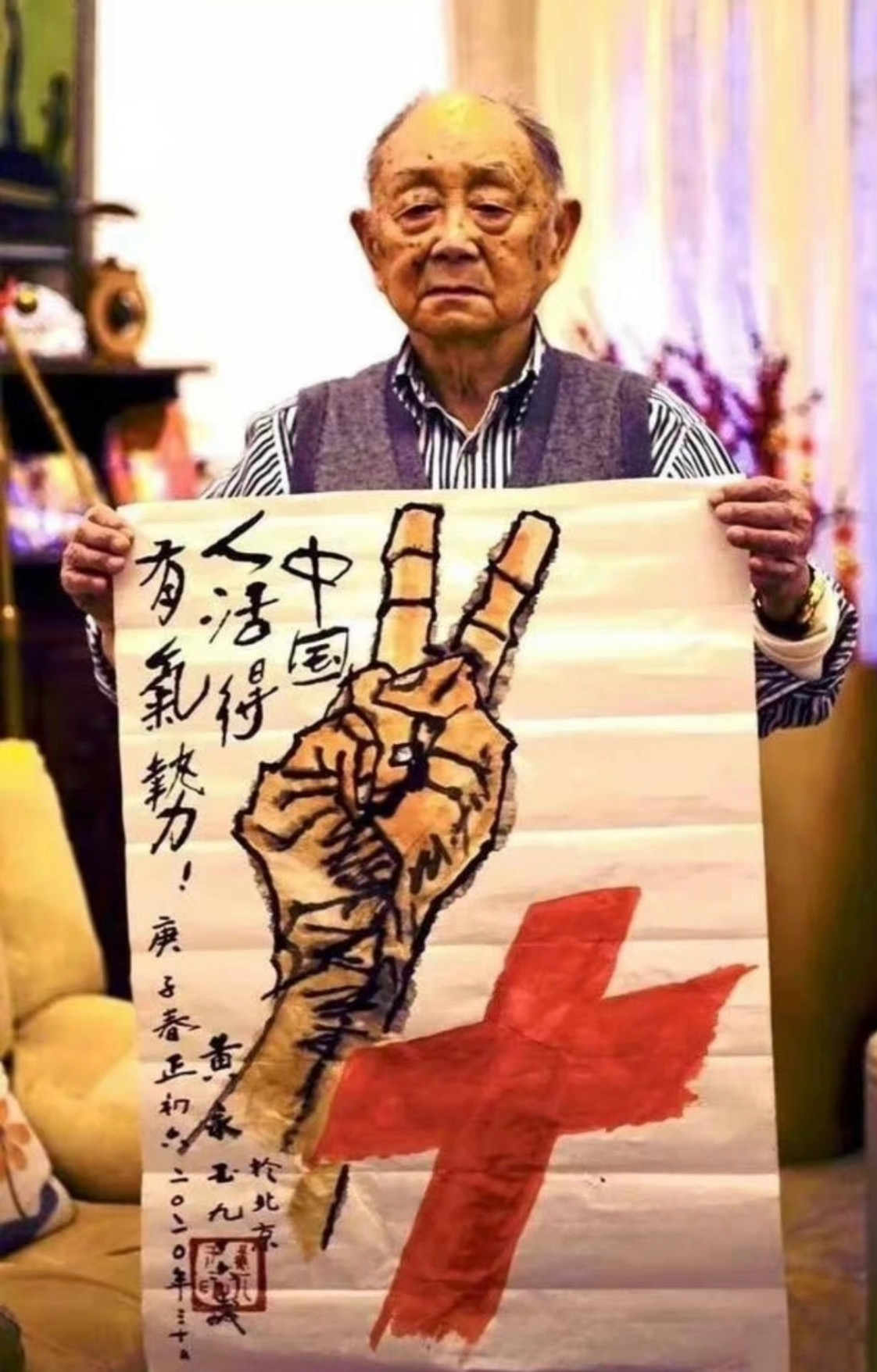

At the time, others were more upbeat. One of their number was the artist Huang Yongyu (黃永玉, 1924-), a celebrated veteran whose art has featured in our work for nearly four decades — we included a number of his ‘animal cracker’ paintings in the 1986 collection Seeds of Fire and, more recently, I featured a woodblock image he made for the 1993 Year of the Dog in which he mocked the MaoCraze (see Mondo Cane, The Year of the Dog 2018 戊戌狗年, China Heritage, 16 February 2018).

On 30 January 2020 — the Sixth Day of the First Lunar Month of the Gengzi Year of the Rat — Huang Yongyu painted a hand in the gesture of a victory sign. The calligraphic inscription on the painting read: ‘The Chinese are living their best life’.

(The way I see it, however, the ‘two-figure salute’ looks like a reverse peace sign, or an ‘up yours’ gesture.)

***

The 26th December 2022 marked both Mao’s birthday and a time of peak Covid chaos in the People’s Republic of China. A digitally altered version of Huang’s painting circulated on the Chinese internet. It was elegant in its simplicity and the message was unequivocal:

For some Chinese netizens, the one-figure salute was the most eloquent way to mark Mao’s birthday and the omnishambles that is the signature of the Xi Jinping era.

***

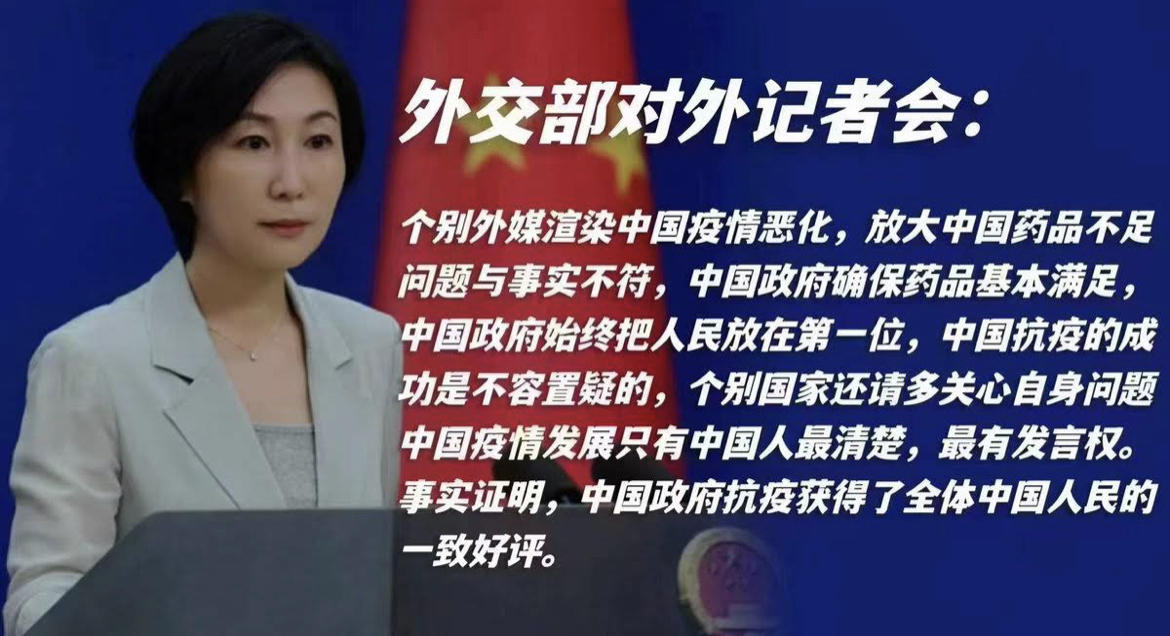

Despite egregious policy failures in the handling of the coronavirus epidemic, Mao Ning, a spokesperson for China’s Foreign Ministry, blamed the international media for blatantly misrepresenting on-the-ground realities.

Addressing a regular press briefing for the foreign media on 23 December 2022, Mao declared that ‘The People come first’. Despite undeniable evidence to the contrary, she extolled the government for successfully responding to the situation, ensuring that the public had more than adequate access to medical supplies and health care:

Mao Ning (毛寧, 1972-), hails from Mao’s hometown and is a member of the Mao lineage. A spokesperson for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs since September 2022, she carries on the clan’s modern tradition in both word and deed. Mao told her audience of foreign journalists that:

‘The evidence is in: All the People of China have nothing but praise for the manner in which the Chinese government has responded to the epidemic.’

It was a counterfactual statement worthy of her infamous / illustrious ancestor. A corrective to Mao Ning’s phantasmagoria can be found in Chang Che’s report, Covid Is Spreading Rapidly in China, New Signs Suggest, The New York Times, 25 December 2022.

As Li Yuan reported in The New York Times:

Xu Kaizhen, a best-selling author famous for novels that explore the intricate workings of China’s bureaucratic politics, wrote on his verified Weibo account that the abrupt change made it abundantly clear “what our government will do, what it likes to do, what it can do, what it doesn’t like to do, what it can’t do and what it doesn’t want to do.”

If good governance is about transparency, responsibility, accountability and responsiveness to the needs of the people, the Chinese government has barely practiced it, either in its harsh “zero Covid” policy or in its haphazard reopening.

It could have spent its resources on increasing vaccine coverage among older people and adding I.C.U. beds. Instead, it spent money on mass Covid testing and enormous quarantine camps.

It could have communicated scientific facts about symptoms and death rates of the Omicron variant. Instead, it fanned fears about Covid.

It could have stocked up on fever medicines and provided the public with the best vaccines available. Instead, it made it extremely difficult for people to buy antipyretics and didn’t approve the public use of foreign mRNA vaccines, which have proved more effective than the Chinese ones in preventing severe symptoms.

Unlike many governments that took steps to flatten the infection curve before reopening, the Chinese government suddenly let go of nearly all restrictions, most likely an effort to rush an enormous country to herd immunity while leaving the old and vulnerable in precarious situations.

Its main advice to the public: “You’re in charge of your own health.” The slogan has been repeated by state media and local governments since the reopening.

But the pandemic is a public health crisis, and such crises are part of the reason governments exist.

— Li Yuan, With ‘Zero Covid,’ China Proved It’s Good at Control. Governance Is Harder., The New York Times, 26 December 2022

***