Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium

Chapter XVII

聚

China’s Highly Consequential Political Silly Season is a three-part meditation on the Twentieth Congress of the Chinese Communist Party convened in Beijing in October 2022. In it we recall the accession of Xi Jinping in 2012 and comment on the ‘terraforming’ impact that Xi and Xi Thought have had on China over the subsequent decade. A chapter in the series Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium, it is also included in Watching China Watching.

In Part Two, we add to our reflections on the ambience surrounding congresses of the Chinese Communist Party and pursue our discussion of the historical landscape of this era. In so doing we take up our observations about the ‘two centenaries’ and efforts to meld the Maoist decades with the post-Mao reform era and then Xi Jinping, a human synecdoche, the authority who as core leader is nothing less than ‘the Party’s brain and central nervous system, ultimate arbiter and sounding board’ 黨中央是大腦和中樞,黨中央必須有定於一尊、一錘定音的權威 (see 習近平談新時代黨的組織路線,新華網,2018年7月4日).

As we observed in Part One of this chapter, Xi Jinping is the ‘Great Reconciler’ of Chinese history; Xi and Xi Thought have, on paper at least, resolved all outstanding policy issues in key areas of the nation’s life that have bedeviled the Party for over four decades. The Party’s Third History Resolution, adopted in November 2021, effectively canonised Xi and his historical vision, in the process eliminating from the public realm all other historical, ideological and cultural possibilities for China’s foreseeable future. But it all builds on decades of debate on policy, history and the nature of modernity both within the Party and among members of the Chinese intelligentsia (see, for example, Red Allure & The Crimson Blindfold’).

America is well suited to appreciate Xi Jinping’s China and its vaunting ambitions. Despite ongoing debates about cold, chilly and hot wars, the two nation-civilisations are in open competition ideologically, economically, militarily, technologically and geo-politically. For this reason alone, it is understandable that the American info-sphere is obsessed with China’s political silly season just as China will obsess over the one that unfolds in America in 2024. We are all witness to or participants in this danse macabre (see, ‘The State of the Sino-American Pas de Deux in 2021’, China Heritage, 20 February 2021).

***

The expression ‘silly season’ — a period during which frivolous news and commentary flourishes — was first recorded in 1861, a fortuitous coincidence since in Qing China that was the year of the Xinyou Coup 辛酉政變 Xīnyǒu zhèngbiàn, a political upheaval that ushered in political, economic, military and cultural transformations that continue to unfold to this day. The ‘restoration’ 中興 zhōng xīng engineered by Prince Gong, a prominent member of the imperial house, and the Dowager Empress Cixi would revitalise the flagging fortunes of the Qing dynasty by means of a comprehensive strategy that would clean up a corrupt bureaucracy and overhaul the army. This was combined with an aggressive policy of industrialisation, modernised communications, reconfigured relations with foreign nations, managed trade and educational reform. The post-Mao Reform era of China is heir to that earlier history. What I call the decade-long ‘Xi Jinping Restoration’ is the latest phase in a process that remains open-ended and endlessly controversial. It is the contested continuation rather than the end of history.

Part Two of our consideration of China’s political silly season is framed by two poems by Mao Zedong. The first, ‘Returning to the Jinggang Mountains’, was composed in mid 1965 in the midst of the Socialist Education Campaign, a frustrated prelude to the Cultural Revolution. The image we have chose to accompany it is a reworked photograph taken by Jiang Qing, his wife, in 1961. It shows the Chairman contemplating the scudding clouds over Lu Shan and the glistening waters of the distant Poyang Lake, which are out of frame. At the time, Mao was fully aware of the disastrous consequences of his Great Leap policies, yet with hubristic self-assurance he pressed on to ‘grasp the moon from the heavens and turtles in the depths of the oceans’. Vaunting ambition and a tendency to claim victory even when caught in the jaws of defeat are defining qualities of the Communist Party’s tirelessly self-congratulatory world view.

As we noted in Part One, today China Watching is big business. Its artful pursuit can inflate reputations, aid and abet fund-raising and launch careers. Nor is there much evidence to suggest that wildly ‘spot-off’ prognostications incur significant reputational damage, let alone shame on the blindsided China Watcher. Serious analysts and prognosticators are also legion. Some even contribute meaningful insights into a party-state intent on frustrating independent analysis and commentary. A new aperçu, a catchy turn of phrase or a striking formulation might actually gain currency and further bolster reputations. A mirror image of such international earnestness also unfolds in China, where the stakes are much higher. Within the Chinese policy, army and intellectual establishments — the realm of what we term the ‘Skin-and-Hair Intelligentsia’ 皮毛知識界 (for more on this, see below) — a similar but far more earnest competition is underway. Phalanxes of contenders jostle to come up with a theoretical tagline or formation that they hope might catch the ‘Eye of Sauron’. In Part III of this essay, we illustrate our argument with two recent examples of such ‘memorial literature’ 奏摺文學.

— Geremie R. Barmé, Editor, China Heritage

Distinguished Fellow, The Asia Society

14 October 2022

***

China’s Highly Consequential Political Silly Season:

At the Congress:

***

Further Reading:

- Prelude to a Restoration: Xi Jinping, Deng Xiaoping, Chen Yun & the Spectre of Mao Zedong, China Heritage, 20 September 2021

- Red Allure & The Crimson Blindfold, China Heritage, 13 July 2021

- The Pirouette of Time — Introduction to ‘After the Future in China’, China Heritage, 28 January 2019

- Xi the Exterminator & the Perfection of Covid Wisdom, China Heritage, 1 September 2022

- The Curse of Great Leaders — the Xi Jinping decade and beyond, China Heritage, 20 July 2022

- Interpreting the Xi Dynasty, Geremie R. Barmé in conversation with Susan Shirk, UC San Diego, January 2020

- A People’s Banana Republic, China Heritage, 5 September 2018

- Deathwatch for a Chairman, China Heritage, 17 July 2018

- What’s New About Such Thinking?, China Heritage, 5 November 2017

- Who’s on First — China’s Successive Failures, China Heritage, 20 November 2017

- The Ayes Have It, China Heritage, 18 October 2017

- Cheng Li, Xi’s three difficulties: The leadership lineup at the 20th Party Congress, Brookings Institute, October 13, 2022

- MERICS, Who is the CCP? China’s Communist Party in Infographics, 12 October 2022

- 鄧聿文,習近平四面樹敵,為什麼黨內反對派對他奈何不得,VOA,2022年10月11日. For a translation of this article by Brendan O’Kane, see Who Are Xi’s Enemies, Foreign Policy, 15 October 2022

- Long Ling, Xi Jinping Studies, London Review of Books, 20 October 2022

- Neil Thomas, A Matter of Perspective: Parsing Insider Accounts of Xi Jinping Ahead of the 20th Party Congress, The China Story, 5 October 2022

- 中共二十大報導:習連任被指違背黨心民意 黨內及紅二代有“氣”無力?, VOA, 2022年9月21日

***

***

重上井岡山

毛澤東

久有凌雲志,

重上井岡山。…

可上九天攬月,

可下五洋捉鱉,

談笑凱歌還。

世上無難事,

只要肯登攀。

Returning to the Jinggang Mountains

Mao Zedong

Long have I aspired to reach for the clouds

And so I return to the Jinggang Mountains. …

We can grab the moon in the Ninth Heaven

And capture turtles deep in the Five Seas:

We’ll return amid triumphant song and laughter.

Nothing is insurmountable in the world

As long as you dare to scale the heights.

- Note: Composed in May 1965, these lines hinted at Mao’s undeterred ambition to pursue a radical vision for China. A year later, the chairman staged an autogolpe and fomented a civil war. The text of ‘Returning to the Jinggang Mountain’ was only made public in January 1976, at which time a sickly Mao contemplated how the flagging spirit of the Cultural Revolution could be rekindled

***

China’s Highly Consequential

Political Silly Season

Part II

Geremie R. Barmé

10 October 2022

‘The threnody of the Xi Jinping decade is tedium, something born of the ceaseless oscillations within China’s hermetically sealed system that signal its deadening presence through reversals and the glum repetition of various tropes of the past. In this era, what was formerly limited divergence has given way to convergence, difference to singularity, diversity to homogeneity. Where in the past there was wriggle room, a straitjacket now awaits; possibility is all too frequently replaced by ordained inevitability; contingency by certainty and the unpredictable is met with inflexibility and harshness. For those who have lived with China’s party-state over the decades the déja-vu quality of the Xi era is undeniable. It is an age that sets itself against the unpredictable, the contingent, against the disheveled nature of reality itself; as a result it is implausible, brittle and in constant crisis-mode.’

— from A Tally 單 — The Threnody of Tedium, 18 February 2022

***

‘Ugh, here we are!’

The idea of tedium has to do with repetition, a return to the past, the obvious; it sums up the sense of boredom and monotony that to my mind has been a major feature of the Xi Jinping decade. It’s what in my student days we were taught about Engels and the historical dialectic: how chance and necessity are interwoven.

My ongoing series on Xi-era tedium reflects the sense I’ve had for many years that something like Xi and his reign were inevitable, even if that inevitability depended on a particular contingency, that is, the appearance of the kind of mission-driven, messianic ruler that we find in Xi Jinping.

After 1978, people tended to focus on how many policies of the High Mao era were re-evaluated or negated. I was always aware, however, that the Mao-Liu-Deng era policies of 1949 to 1966 were, apart from the Great Leap Forward, generally re-affirmed. The Maoist past saw the dual suppression of the working class (workers, peasants, etc) by the Party nomenklatura, and the suppression of the urban elites (managers, bureaucrats, business people, educators, the legal profession, media, etc), as the Communists expanded their power in Leninist-Stalinist style to invade every aspect of society.

For all of the cosmetic changes to China’s party-state, its essence, its modus operandi, though marginally challenged and even reformable, remained; as a result, what had happened in the autocratic past could happen again. “Dual suppression” has also been a feature of the Xi Jinping era. The laboring masses serve at the pleasure of the Party nomenklatura, which has been greatly strengthened, and once more the elites have been goose-stepped into complying with prerogatives of the party-state.

Now, this is all part of the ambience of tedium that I have been investigating; it is a handy term that I use to sum up a sense that many of my friends in the Chinese world, not just in China, but internationally, also have, a foreboding that had been welling up for years prior to the advent of Xi Jinping. Personally, I had little doubt about the glum future as soon as Xi got into power; it was also a shared sense among many people who, ten years ago at the advent of this tired old new era of Xi, were in their 50s or above. So many felt, “Damn it, here we go again!” Here’s the ugly desire to dominate, to control, to patronize, to manipulate, to repress and to silence.

Not to be too “China boomer” about this, but anyone who had lived through the last sixty years or so, will have seen the partial reforms from the late seventies, the potential and failures (as well as the lessons) of the 1980s, then the fitful repressions in the 1990s, followed by more circumscribed opening up and so on. It was easy to be dazzled by material changes and many found it boring to take all that Party palaver seriously. I did and, for the past decade, my sense of ennui has been paired with the sentiment that, “Ugh, here we are.”

This same old stuff, more extreme, more over the top; we will witness this for years to come and, as we all do, be it in China or outside, the old addiction to hope, hopium, part of the last four and a half decades of the “hopioid crisis” of China, will mean that huge amounts of time and effort will be devoted to ferreting out every sign of change, every possibility of transformation, reform and opening up, every scintilla of difference that can be detected in the obsidian surface of Party control. It’s boring; it’s understandable; it’s forgivable. And, for all of the ingenuity of scholars, analysts et al, it is also mind-numbingly tedious.

— from Jeremy Goldkorn, ‘Ugh, here we are’ — Q&A with Geremie Barmé,The China Project, 8 April 2022

***

In the interview quoted here Jeremy Goldkorn, editor of The China Project, started by asking about a video clip of a disgruntled older gentleman in Shanghai who was recorded complaining about the extreme anti-Covid lockdown measures imposed in that city in March 2022. I remarked that:

‘His ad lib comments are a reflection of what I think of as “totalitarian reflux.” A political acid reflux or an autoimmune response. He’s literally had a gutful and suddenly the memory of all those other stomach-churning meals comes welling up, the bile fills the mouth, you feel grossed out and you just have to vent.’

Having initially examined the lure of what Svetlana Boym termed totalitarian nostalgia in 1990s China, I felt emboldened to update those reflections in We Need to Talk About Totalitarianism, Again, which is the first chapter in Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium. It has been encouraging to note the late-day realisation by some China boffins and public commentators that the Chinese Communists are ‘Marxist-Leninists’ and that Sinicized versions of historical and dialectical materialism underpin much of China’s practical politics. For my part, I have regarded these stock phrases as both inadequate and vacuous when considering post-1989 China. I would point out that the era of Xi Jinping Thought is, in particular, heir to a complex tangle of traditions, ideas and practices. As I remarked in 2014, it is clear from his public pronouncements that Xi sees himself as un homme providentiel who is the embodiment of History as sketched out in the Stalino-Maoist version of Marxist thought. At that time, I also observed that the Xi era was proving to be a boon for the New Sinologist for even eight years ago it was obvious that:

‘in today’s China, party-state rule is attempting to preserve the core of the cloak-and-dagger Leninist state while its leaders tirelessly repeat Maoist dicta which are amplified by socialist-style neo-liberal policies wedded to cosmetic institutional Confucian conservatism.’

In 2016, Professor Xu Zhangrun 許章潤, a famously outspoken Beijing-based legal scholar whose work has featured prominently in China Heritage since August 2018, characterised Xi-era theology as ‘Legalist-Fascist-Stalinism’ 法日斯 Fǎ-Rì-Sī. It was his shorthand for the hybrid body of ideas that was ‘cobbled together from strains of traditional harsh Chinese Legalist thought [法 Fǎ; that is, 中式法家思想] wedded to an admix of the Leninist-Stalinist interpretation of Marxism [斯 Sī; 斯大林主義] along with the “Germano-Aryan” form of fascism [日 Rì; 日耳曼法西斯主義].’ (For more on this, see China’s Heart of Darkness, China Heritage, 14 July 2020.)

The pullulating traditions of the Chinese Communists thus reach back to Legalist cynicism and Neo-Confucian moral absolutism which are combined with a Marxist historical landscape that has been filtered through Lenin and Stalin via Mao Zedong. In particular, we recall that Stalin’s version of Marxist-Leninist dogma was sinified by Mao Zedong along with other Party leaders and their fellow-travelling thinkers (an amorphous and shifting coterie of enthusiasts, propagandists, secretaries, pliant historians, philosophers, academics and journalists) over the four decades from the late 1920s up to the early 1960s. (The thinking behind the Cultural Revolution era of 1964 to 1976, however, owed more of a debt to Leon Trotsky than to the Vozhd.)

Xi Jinping and his colleagues have inherited a syncretic ideology known as ‘Mao Thought’ (long referred to as ‘the quintessence of the Party’s collective wisdom’ 集體智慧的結晶) that has been cherry-picked, revised and expanded by the theories and political practices of the Deng-Jiang-Hu era. In his report to the Nineteenth Party Congress in October 2017, Xi Jinping effectively announced that ‘Xi Jinping Thought’ (which he modestly called ‘Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for the New Era [of himself]’) was the latest creative stage in the evolution of a century old ideological enterprise. For a decade Xi Jinping’s ‘empire of tedium’ has thus gathered unto itself the disparate strands of the past and interwoven them with a gimcrack version of traditional thought along with nootropic infusions from a plethora of au courant international ideas. This unwieldy corpus continues to bloat as think tanks, aspiring academics and political wannabes feed its hungry maw.

‘Theoretic innovation’ 理論創新 is married to ‘creative transformation’ 創造性的轉換 in a guided process aimed at achieving ever greater heights — of rhetoric if not real-world achievement. The genius of Xi Jinping Thought is not only in what it presently encompasses, but also in its unstoppable forward motion. This juggernaut is a matrix of self-adjusting, self-reaffirming and self-preserving practices. It offers a worldview grounded in materialism and economic determinism, one that sometimes brings to mind the technological utopianism championed by some America billionaires and the rapacious earthy vision of the Dominionists.

For followers of popular culture, China’s ideo-social-cultural ultra-stable system 超穩定性結構 — to use a formulation devised by Jin Guantao and Liu Qingfeng in the 1980s — resembles the Borg, an army of cyborgs featured in Star Trek since 1989 (starting with the episode ‘Q Who’). These cybernetic organisms are linked to ‘The Collective’, a hive mind the sole purpose of which is the assimilation of all available ideas and technologies in a quest to achieve perfection. The shibboleth of the Borg — ‘resistance is futile’ — is repeated robotically whenever they encounter opposition.

***

The Skin-and-Hair Intelligentsia

Advising the Centre

The Communist Party leadership has, throughout its history, relied on intellectuals and ideologues to rationalize the quirks and shifts of its decision making. The more talented and astute of this caste serve a function not entirely dissimilar to that of advisers or censors at the imperial court, or perhaps their role can be likened to the itinerant ‘lobbyists’, 遊說之士 yóu shuì zhī shì, or the ‘strategists’, 縱橫家 zòng héng jiā, literally ‘those who suggest lateral and horizontal alliances’, of the Warring States period. In the ‘Five Vermin’ 五蠹 chapter of the classical philosophical text Hanfeizi, strategists are singled out along with scholars, knights-errant, fawners, merchants, and artisans as being the true enemies of the state. (Prince Han warns that for all of their convincing babble, lobbyists serve their own interests: 遊說之士孰不為用矰繳之說而徼幸其後。For more on this, see ‘The Five Vermin Threatening China’.)

Sometimes these hired hands — although voluntary careerists also feature prominently — have proved to be highly capable. This was true in the case of crafty party apparatchiki like Chen Boda, Zhou Yang, and Hu Qiaomu in the 1940s and 1950s or others like Yao Wenyuan in the 1960s. In the 1980s and 1990s, there has been no dearth of men and women ready to offer policy advice to the power holders. Similarly, in the commercial environment, ideas too have become a commodity, and a futures market in ideology has seen a steady growth. Think tanks and newly founded journals vie for the attention of both a public readership and the elitist cognoscenti. It is invariably the fate of the passive-aggressive intellectuals that their ideas are used by the victors in a given political struggle to justify their actions, and for the modern zòng héng jiā, this is one of the chief aims of their intellectual activity. But there can be hidden dangers also for the volunteer strategist, for in periods of political crisis, their carefully balanced advice can also be used to support irrational policy decisions and to damn the author who has so eagerly sought the attention of his leaders.

Over the years, many talented intellectuals have written for the party leadership, and although they have generally remained hidden from view in their preferred role as authors of internal reports, they have often enjoyed considerable influence. Their true importance is sometimes revealed only after the passage of time or, suddenly, by purges of the party’s ranks. In the past, many memorialists were satisfied with positions as crucial members of some high-level writing group or as rōnin intellectuals in search of patronage from the powerful.

[Note: These paragraphs are from ‘Screw You, Too’, the Appendix to my In the Red: Contemporary Chinese Culture, New York: Columbia University Press, 1999, pp.365-366]

***

When marking the fortieth anniversary of my friendship with Dai Qing, a journalist, novelist and investigative historian whose work has been banned in China since 1989, I celebrated her unwavering spirit of honesty, her tireless quest to question and to speak out, her refusal to play the role of dissident that others would assign to her, and her scintillating prose and sardonic understanding, one that is always tempered by a profound humanity. I also remarked on her work on Liang Shuming, Wang Shiwei, Chu Anping, Zhang Dongsun, Huang Wanli and others in the tradition of intellectual independence. They are figures whose examples stand as an accusation against the vast majority of state intellectuals who, today more so than at any point since 1976, accommodate and serve the power-holders. In so doing they may well conform with an ancient lineage of servitude mentioned above, but they also knowingly betray the promise and sacrifices of their more independent-minded forebears.

What then are they, these modern-day intellectual courtiers? Whether they justify themselves as reluctant fellow-travellers or memorialists, hoping that a line here or a thought there may be ‘taken on board’ by the party-state, or men and women who contribute their particular brand of sophistry to intellectual authority, all the while enjoying the lavish emoluments and opportunities that complicity affords, these are China’s twenty-first century ‘Skin-and-Hair Intelligentsia’ 皮毛知識分子.

The neologism ‘Skin-and-Hair Intelligentsia’ is of my invention. It is inspired by comments that Mao Zedong made in the summer of 1957 at the height of the Anti-Rightist Campaign, the vast ideological purge stage-managed by Deng Xiaoping (and subsequently re-affirmed by the Party from 1978) that crippled the ability of Chinese people from all walks of life to pursue any substantive form of independent, and effective, intellectual and critical engagement with the nation’s political life. Official figures hold that over 500,000 men and women were blighted by the 1957 purge, although unofficial estimates are much higher. The intellectual and political life of China has never recovered from that devastating intellectual pivot.

At the time, Mao quoted a line from The Commentary of Zuo 左傳, an ancient narrative history, to declare that ”The intellectuals must transform themselves into proletarian intellectuals.’

‘There is no other way out for them. “With the skin gone, to what can the hair attach itself?” [皮之不存,毛將焉附] … At present what kind of skin do intellectuals attach themselves to? To the skin of public ownership, to the proletariat. Who provides them with a living? The workers and peasants. Intellectuals are teachers employed by the working class and the labouring people to teach their children. If they go against the wishes of their masters and insist on teaching their own set of subjects, teaching stereotyped writing, Confucian classics or capitalist rubbish, and turn out a number of counter-revolutionaries, the working class will not tolerate it and will sack them and not renew their contract for the coming year.

‘… Some intellectuals are now unsettled. Suspended as they are in mid-air, they have nothing to hang on to above and no solid ground to rest their feet on below. I say, these people may be called “gentlemen in mid-air”. Flying in mid-air, they want to go back but are unable to because they find their old home, those skins, gone. … They still hanker after what they know is gone. What we are doing now is persuading them to wake up. After this great debate, I think they will wake up somehow or other.’

— Mao Zedong 毛澤東, ‘Beat Back the Attacks of the Bourgeois Rightists’

在上海各界人士會議上的講話 (記錄要點), 一九五七年七月八日

Mao’s sixty-year-old clarion ‘wake-up call’ finds a ready echo in Xi Jinping’s new era. It is one in which the old, fragile market of ideas rejects embargoed products in favour of questionable sophistry and self-serving posturing.

[Note: for a translation blog devoted to the long-winded jibber-jabber of avid members of the Skin-and-Hair Intelligentsia, see Reading the China Dream. See also ‘The Scribblers Mafia’ in Victor Shih, Coalitions of the Weak (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022), p.156ff.]

***

During the power transition from 2010 to 2012, writers, commentators and analysts of all kinds (and not just establishment intellectuals) availed themselves of every available outlet to debate the future direction of the Party and China. It was a rare moment of contestation that recalled fleeting periods of relative relaxation in 1978-1979, 1986 and 1988-1989, 2000-2003 and 2008. We heard, for example, from the Children of Yan’an, a private group consisting of the children and grandchildren of some of the Party’s founders. Confident that they were well within their rights to offer advice they called for a revitalization of the Party’s traditional ethos of hard work and clean living. For others, the outspokenness of the Children of Yan’an reflected the Party’s crisis of faith. In the melee of opinion a common refrain was the old expression: ‘when it’s the end of days vile and bizarre characters appear everywhere’ 末世征兆妖孽四起.

Others expressed their hopes and fears more directly. In August 2012, for instance, the independent critic Rong Jian 榮劍 published his searching ‘Ten Questions for China to Answer’ 十問中國, and in September that year Caijing 財經, a leading business magazine, ran a hard-hitting three-part analysis of the political legacy of the Hu-Wen era written by Deng Yuwen 鄧聿文, an analyst at the Central Party School. Other less critical members of the official community of analysts also spoke up. One of their number was Yuan Peng 袁鹏, a senior analyst at a Ministry of State Security think tank who wrote ‘Where Are the Real Threats to China?’ in which he warned of the threat to the system posed by five marginal but potentially dangerous groups: rights lawyers, underground religious activities, dissidents, Internet leaders and socially vulnerable individuals.

In 2022, however, these voices are absent — following Xi Jinping’s rise and the reinvigoration of Party control, the Children of Yan’an went into abeyance; in 2021 Rong Jian was placed under surveillance and since writing a scathing critique of the darling of China’s high-end New Leftists he is also forbidden from publishing anything; Deng Yuwen comments on Beijing politics from a safe haven in Pennsylvania (see, for example, Xi Jinping’s Enemies and their Impotence) and, having been elevated to become the head of his old think tank, Yuan Peng offers his more unvarnished analytical insights for Party leaders. As for average Chinese citizens, business people and the government bureaucrats who actually keep the show on the road, as well as commentators, journalists and academics, that is the people for whom the Twentieth Party Congress matters the most? For all intents and purposes they cannot participate publicly, or meaningfully, in the proceedings.

***

XJPXSDZGTSSHZYSX

In Xi Jinping’s China the cacophony and contestation of the past has largely been eliminated. Even so, surreptitious oppositional voices still fitfully avail themselves of social media platforms while works published overseas circulate for a moment before being scrubbed away by the censors and their algorithms. These occasional eruptions and sallies might give the hopeful observer the impression that a dogged and lively resistance is conducting a guerrilla war on the suffocating world of the Borg. For the foreseeable future, however, the Hive Mind is dominant and expands to fill all available spaces in the name of ‘Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era 習近平新時代中國特色社會主義思想. In Hanyu Pinyin romanisation the ruling ideology is Xi Jin Ping Xin Shi Dai Zhong Guo Te Se She Hui Zhu Yi Si Xiang. When writing about the ubiquity of Xi Thought for the London Review of Books on the eve of the October 2022 Twentieth Party Congress, Long Ling refers to this unwieldy word-sentence as ‘XJPXSDZGTSSHZYSX’.

‘The study of XJPXSDZGTSSHZYSX isn’t limited to party members, or to adults,’ Long observes:

When schools went back in September, students found a new textbook, Student Book of Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era. In April, the ministry of education issued a new curriculum for compulsory education and stipulated that it adopt ‘the implementation of the Student Book of Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era as its main task’. The ministry has developed four editions of the Xi textbooks for primary school, junior and senior high school students. On the covers of all of them are quotes from Xi Jinping. When children under ten get out their textbooks, the first thing they read is: ‘Do up life’s first button well.’ The motto for ten to twelve-year-olds is: ‘Happiness is achieved through hard work.’ The official media call these words ‘golden sentences containing the power of truth, thought, wisdom and personality’, and Xi classes are called ‘golden lessons’. The ‘happiness’ quote was taken from Xi’s 2018 New Year address, and has spread across Chinese TV channels, billboards and the internet. The sentence preceding it reads: ‘No pies fall from the sky.’

A mother whose ten-year-old son attends one of Beijing’s elite state primary schools told me: ‘I can’t tell the difference between the Chinese language classes and the ideology classes.’ This is consistent with, indeed is stipulated in, the new curriculum. The ministry of education requires the integration of Xi lessons not only into Chinese language and history classes, but mathematics, physics, geography and even PE. The textbook for the lower years of primary school includes ‘Lesson Two: I follow the Communist Party wholeheartedly,’ which has a section titled ‘Grandpa Xi Jinping cares about the people.’ The lesson plan instructs teachers to infiltrate the essence of Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era to students so that they seek happiness for the people, rejuvenation for the nation and contribute to the world. The class is designed to make students feel love and admiration for President Xi Jinping from the bottom of their hearts, and to feel proud that China has such a great leader.

Teaching plans for older classes suggest that teachers ask: ‘Do you know how the people exercise their rights to govern the country? Please discuss this in a group, based on your life experience, literature review and interviews.’ The expected answer is: ‘I know that the people exercise their rights through the national and local people’s congresses. My family members have participated in the election of representatives to the people’s congress.’ One day my friend’s child, who will have been educated like this, will type ‘agree’, just as I did when voting for this year’s Party Congress representatives from my branch. A generation of children are learning to recite the quotes of Xi Jinping and will remember them all their lives, just as my generation and my parents’ generation can quote Mao.

— Long Ling, Xi Jinping Studies, London Review of Books, 20 October 2022

***

EyeCTV on the Twentieth Congress of China’s Communist Party

中共二十大:習帝而作

- Note: At EyeCTV’s regular press conference held on behalf of the Ministry of Winnie Affairs on 5 October, ‘Geng Shuang’ commented on rumours about plans for Xi Jinping to ascend the dragon throne as ‘Founding Emperor Dumpling’ 習包祖 as well as baseless scuttlebutt about a coup against the General Secretary in Beijing. The screenshot features a Winnie the Pooh doll in pop, or ‘Bottled Xi’ 习進瓶, a reference to Xi’s house arrest. The legend at the top of the screen reads: ‘Chinsult Press Conference: the Department of Bandit Foreign Affairs reveals that Winnie the Poo Xi Jinping will declared himself emperor at the Twentieth Congress of the Chinese Communist Party’ (for more from EyeCTV, see October 1 & October 10 — Two Chinas, Whose Fatherland?, China Heritage, 1 October 2022)

***

The Tiger’s Arse & Echo Chambers

At the time that we launched the series Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium we noted that the Year of the Tiger (1 February 2022 to 21 January 2023) would be a period marked by exaggerated claims, intimidation and hubristic overreach (see Greeting the Year of the Tiger 壬寅虎年, 31 January 2022.) We also referred to the celebrated twentieth-century writer Lu Xun’s use of the expression 拉大旗作虎皮 lā dàqí zuò hǔpí, literally ‘to wrap yourself in a large flag as though it were a tiger skin’. It is a way of mocking people who disguise their lack of substance with bluster.

In the ‘Silly Season’ we have quoted official Chinese media and Xi Jinping himself to illustrate the histrionics common in China today. Overblown official rhetoric has increased in inverse proportion to the silencing of other voices (for more on this, see Mendacious, Hyperbolic & Fatuous — an ill wind from People’s Daily, China Heritage, 10 July 2018).

The post-Mao reform era had begun with Deng Xiaoping and his colleagues criticising what they called the ‘Monologue Hall’ 一言堂 that had dominated the Party for decades. In their efforts to re-engage both Party members and the public in their program of economic and structural change they called for ‘the pathways of expression to expand’ 廣開言路 so that a ‘Chamber of Collective Voices’ 群言堂 could flourish. People would only speak out and offer constructive views if they were not scared of ‘touching the Tiger’s Arse’, or rubbing the leaders the wrong way. (In a self-critical mood resulting from his murderous Great Leap policies and the criticisms of his comrades, in 1962 Mao famously warned the Party that no one in power should be allowed to think that ‘their tiger’s arses can’t be touched’ 老虎屁股摸不得. — bouncing back from that rare moment of contrition in the mid 1960s, the Chairman would, however, demonstrate that his was one arse that was sacrosanct.)

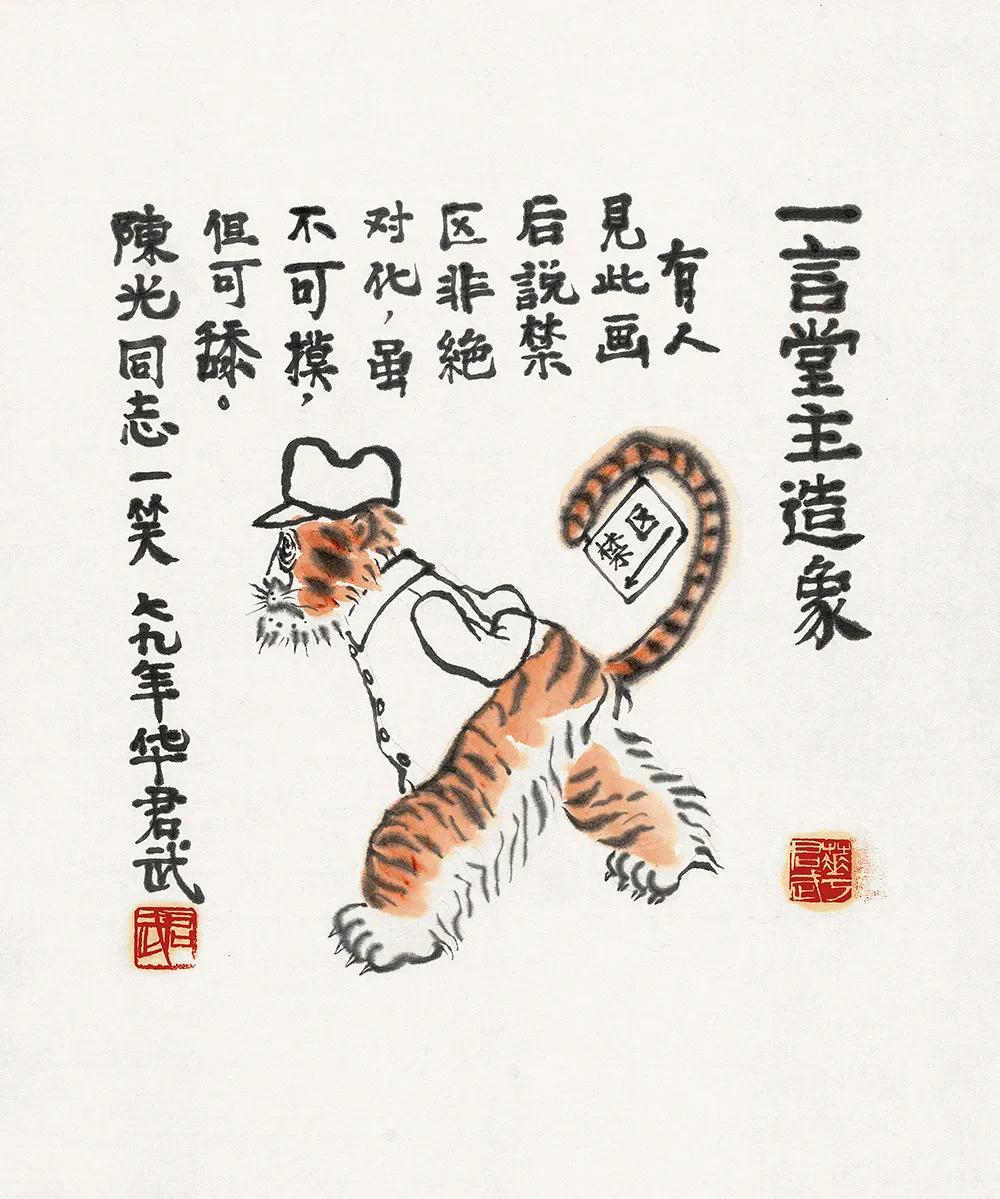

In A Winking Owl, a Volant Dragon & the Tiger’s Arse, the proem to this series, we illustrated the connection between the Master of Monologue Hall 一言堂主 and the Tiger’s Arse by reproducing a painting made by the artist Hua Junwu in 1979:

The inscription of this ‘Portrait of the Master of Monologue Hall’ reads:

‘People have said about this painting that the no-go zone 禁區 jìnqū [of the tiger’s arse] is not absolute. Although it can’t be touched, it certainly may be licked.’

有人見此畫說禁區非絕對化,雖不可摸,但可舔。

As Linda Jaivin has observed: ‘Disparate voices have always struggled to be heard above the megaphonic drone of the party’s yi yan tang, or “one-voice shop”, an old expression for a store whose owner forbids haggling over prices that now stands as a metaphor for autocratic rule.’

In 2022, Xi Jinping is the sole proprietor of China’s One-voice Shop 一言堂主.

***

End of Part II

***

China’s Highly Consequential Political Silly Season:

At the Congress:

***