Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium

Chapter II

Part I

∓ 加減

The Sixth of July in the Year of the Dog —

I was reborn, from a sacrificial offering on an exquisite altar

Detention set me on a course to join a broader humanity

After my lustration, I share the embrace of a different fellowship七月六日,歲在庚子

我重生於一場優美的獻祭

因為囚禁,從此奔向了全人類

人類用泯於眾人將我緬懷

This is the first stanza in a pair of poems composed by Xu Zhangrun, formerly a professor of jurisprudence, on the eve of 6 July 2023. On that day three years earlier, a large contingent of police and security personnel had detained him at his apartment in the far western suburbs of Beijing. His captors told him that he was being investigated for having ‘solicited prostitutes’ while on a trip to southwest China with friends the previous November.

The resulting outcry, both in China and internationally, led to Xu’s release some ten days later without charge, but not before Tsinghua University, an institution where he had previously enjoyed a prestigious and celebrated career, had cashiered him, stripped him of his pension and eliminated his presence from the campus.

Professor Xu had been under investigation since July 2018, when he had released an unsparing and detailed critique of the Xi Jinping era. For over eighteen months China’s Stasi had subjected him to rounds of interrogation and escalating threats. Although banned from teaching, carrying out research or publishing, Xu had continued to write at a furious pace and he produced a series of essays in which he investigated the historical roots of China’s contemporary predicament. He also warned that, under Xi Jinping, China was turning into a Red Empire that would threaten the global order. Some of that work has appeared in translation in the Xu Zhangrun Archive on this site.

When the Chinese city of Wuhan was locked down during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, Xu Zhangrun again took aim at Xi Jinping and his maladministration. In Viral Alarm: When Fury Overcomes Fear, he declared that:

Ours is a system in which The Ultimate Arbiter [定於一尊, an imperial-era term used by state media to describe Xi Jinping] monopolizes all effective power. This led to what I would call “organizational discombobulation” that, in turn, has served to enable a dangerous “systemic impotence” at every level. Thereby, a political culture has been nurtured that, in terms of the actual public good, is ethically bankrupt, for it is one that strains to vouchsafe its privatized Party-state, or what they call their “Mountains and Rivers,” while abandoning the people over which it holds sway to suffer the vicissitudes of a cruel fate. It is a system that turns every natural disaster into an even greater man-made catastrophe. The coronavirus epidemic has revealed the rotten core of Chinese governance; the fragile and vacuous heart of the jittering edifice of the state has thereby been shown up as never before.

That defiant gesture doubtlessly contributed to Xu Zhangrun’s detention on 6 July 2020. Following his release, and with the help of an independent publisher in New York, Professor Xu would continue to flout the bans placed on him to produce a series of books. China’s Ongoing Crisis: Six Chapters (2019) continued his earlier work and Ten Letters from a Year of Plague (2020) was a multifaceted farewell to his former life. In Reading Erich Maria Remarque and Joseph Brodsky, rejecting the barbarism of our times (2022), he investigated the literary connections between two disaffected European writers and in From Heaps of Ashes (2022) he produced a poetic meditation on his fate. In an essay published by The New York Review of Books in August 2021, he dissected Xi’s particular autocratic style of rule.

[Note: See:

- Xu Zhangrun, Ten Letters from a Year of Plague 庚子十劄

- Xu Zhangrun, ‘Xi’s China, the Handiwork of an Autocratic Roué’, New York Review of Books, 9 August 2021

- ‘The Refusal of One Decent Man’, New York Review of Books, 21 August 2021

- Notre seul parapluie — ‘Life is a shitstorm, in which art is our only umbrella.’, China Heritage, 15 August 2022

- Xu Zhangrun at Sixty, China Heritage, 25 October 2022.]

***

Many other critics of Beijing’s response to the pandemic were also disappeared. They included the independent ‘citizen journalists’ Zhang Zhan 張展 and Chen Qiushi 陳秋實, both of whom attempted to report from the ground zero of the epidemic. The victims of COVID censorship also included Xu Zhiyong 許志永, a celebrated lawyer and civil rights activist, and Ren Zhiqiang 任志強, a property tycoon known for his outspokenness. Xu Zhiyong had openly called for Xi Jinping to resign and in a scarifying essay Ren had mocked the Chairman of Everything as ‘a clown whose threadbare performance had left him naked for all to see’. Both men were eventually handed heavy jail sentences on spurious charges.

China Heritage marked Professor Xu’s detention and release in July 2020 with two essays:

- 無可奈何 — So It Goes, 6 July 2020; and,

- Xu Zhangrun & China’s Former People, 13 July 2020

On the third anniversary of his release, both of those essays are reproduced below.

Although spared incarceration, from 2020 Xu Zhangrun has been consigned to ‘social death’ 社死 shè sǐ (an abbreviation of the term 社會性死亡 shèhuìxìng sǐwáng), an ostracism about which he has written eloquently (see Cyclopes on My Doorstep and Composed of Eros & of Dust — Xu Zhangrun Goes Shopping).

Pariahs, non-persons, others, or what in Soviet times were called ‘Former People’: individuals with no status, no identity, social ghosts, the invisible, reprehensible. unredeemable and unapproachable. ‘Banished to a Separate Registry’ 打入另冊 dǎrù lìng cè is the Qing-dynasty term that was revived during the Mao era to describe this particularly cruel form of ‘othering’. The ‘Separate Registry’ includes countless individuals and families, who have dared resist, or even gone so far as to speak out and protest against Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium.

In the face of reports about China’s demographic decline, the country’s population of Former People is burgeoning. Indeed, under Xi Jinping the ranks of Former People have increased at a rate not seen since the heyday of Maoism.

There is no reliable measure of when, how or why someone who has enjoyed a lifetime in the ‘Formal Registry’ 正冊 zhèng cè of normal existence ends up in the ‘Separate Registry’ 另冊 lìng cè of non-people or Former People. It can be the result of premeditated rebellion, as in the case of Xu Zhangrun or Peng Lifa, the Hero of Sitongqiao, who protested against Xi Jinping’s rule just before the Communist Party’s Twentieth Congress convened in October 2022. Or, errant behaviour can be unpredictable and sudden, as was the case with participants in the Blank Paper Rebellion of November 2022. It is impossible to know what motivated that brave lone woman who was arrested for waving an American flag and distributing leaflets that contained paragraphs from the US Declaration of Independence on the eve of June Fourth 2023.

***

Xu Zhangrun turned sixty on 25 October 2022. Born in an impoverished village in Anhui, a province that was devastated both by the murderous policies of the Great Leap Forward and by torrential rains and flooding, he was lucky to survive; one of his older brothers died of malnutrition.

Sixty years later and despite the dramatic change to China’s material circumstances, the authoritarian spectres of the past continue to haunt the present. Today, they do so in the person of Xi Jinping, the master of China’s party-state-army and chairman of everything, and via the leadership collective surrounding Xi that was anointed at the Communist Party’s Twentieth National Congress on 23 October 2022.

In a poem written to mark that day, Professor Xu wrote:

下一站,風陵渡

錦衣衛,去你媽

The next stop is a parting of the ways

In the meantime, fuck China’s KGB!

— from Xu Zhangrun at Sixty, 25 October 2022

***

Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium is dedicated to Xu Zhangrun. Here we remember that day he was formally relegated to the burgeoning ranks of China’s Former People.

We are grateful that China Heritage has been able to play a role in introducing Xu Zhangrun’s clarion voice to an international audience. Today, the 13th of July 2023, as we mark the sixth anniversary of the death of Liu Xiaobo, we mourn Xiaobo, we commemorate Xu Zhangrun’s resilience and we also remember Ruan Xiaohuan 阮曉寰 (aka ‘ProgramThink’ 編程隨想), a writer whose anonymous online rebellion gave heart to so many for many years.

As we observe in ‘Xi Jinping’s Demographic Boom’, Part II of this chapter, Liu Xiaobo was detained in December 2008, a year that can now rightly be seen as something of a preamble to the Xi Jinping Era. Shortly after Liu’s disappearance, Ruan Xiaohuan launched his anonymous ‘rebellion in writing’.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

13 July 2023

The Sixth Anniversary of Liu Xiaobo’s Death

劉曉波祭日

***

July the Sixth

七月六日

two poems by Xu Zhangrun

許章潤

with an inadequate, albeit well-intentioned, annotated translation by Geremie R. Barmé

July the Sixth — meaning is a buoy buffeted by the waves

carrying me into old age, proffering for now life on the verge

One

一

The Sixth of July in the Year of the Dog —

I was reborn, from a sacrificial offering on an exquisite altar

Detention set me on a course to join a broader humanity

After my lustration, I would share the embrace of a different fellowship

七月六日,歲在庚子

我重生於一場優美的獻祭

因為囚禁,從此奔向了全人類

人類用泯於眾人將我緬懷

Time extends to infinity even as its limits crowd upon us

There is no miracle on the horizon; even the sun grows haggard

From 6 July 2020, every dawn ushers in worshipful commemoration, farewell

My sojourn has led to Voronezh, any day could be my last

時間因太過遼闊而逼窄

平原沒有奇蹟,太陽愈見老邁

生日後的每一天都是祭日

七月六日,我的沃羅涅日

[Note: ‘Voronezh’ 沃羅涅日 refers to Voronezh Notebooks composed by

Osip Mandelstam (1891-1938) during the last years of his exile and shortly before his death. Anna Akhmatova visited the Mandelstams in Voronezh and wrote: ‘But in the room of the poet in disgrace/ Fear and the Muse keep watch by turns./ And the night comes on/ That knows no dawn.’]

There is no shame in being unarmed

Our lot has always been to cultivate mulberry and pick ferns

Even so, the Earth continues its course despite Their Rules

Arrogant prison bars cannot prevent the sun shining or rain falling

On July the Sixth, those ancient ashes are born to us on the wind

無需為手無寸鐵而羞愧

種桑採薇,地球從不服從圓規

傲慢的鐵柵也得承受雨淋日曬

七月六日,天空飄過遠古的灰

[Note: ‘Pick ferns’ 採薇 is a reference to the Han-dynasty Grand Historian Sima Qian’s biography of Boyi and Shuqi, China’s earliest ‘dissidents’, which records that the brothers ‘found refuge at Shouyang Mountain, fed off ferns rather than eat the unrighteous millet of the Kingdom of Zhou and starved to death’ 義不食周粟,隱於首陽山,採薇而食之,及餓且死。’Ancient ashes’ 遠古的灰 are the result of the conflagrations of history. See Words of Gratitude, Elegies of Anger, 23 January 2023.]

The echos in the empty valley resound, belonging to none

July the Sixth, humanity itself now the kin of flowing waters

My soul signs to the Mountains and Rivers in a secret language:

I have lived and now death is mine — the desolate reality for all beings

空谷觸痛的回聲沒有姓氏

七月六日,人類是流水的義子

心靈以啞語對山河秘語

我生過,我死過,眾生孤獨

Two

二

This, too, is life of a sort, one in which

I pay my respects to eternity’s imperfect future tense

The workings of the universe — in weal and bane — are mysterious

Each new sacrifice allows pause for further contemplation

依舊活在一種生活方式裡

向永恆未完成的時態禮讚

一轉頭,淨化之火家道中落

獻祭的絢爛退而屏息凝思

Worship this inebriation, drink to the lees

Calamity ever unfolds around such revelries

We accept this world amidst dark premonitions

In the age of the cynic, They turn a deaf ear to the distant thunder

崇拜微醺,也感恩深醉

形而上學在歡樂中出軌

接受世界只因預感災難將至

忿世嫉俗的時代聽不到驚雷

[Note: ‘Distant thunder’ 驚雷 is a reference to a poem by Lu Xun dated 30 May 1934, the last line of which reads 於無聲處聽驚雷, literally, ‘A startling clap of thunder is heard where silence reigns’.]

Regardless, Earth is our precious realm, not the Skies above

The End of Our History must lie in modest gestures of remembrance

An existence that has not found expression in poetry is not worthy of praise

Their grandiose claims are ultimately exercises in futility

畢竟大地比天空更加昂貴

歷史終結於死後記憶的式微

未曾化作詩句的存在不值得讚美

奮發圖強,所以無所作為

July the Sixth — meaning is a buoy buffeted by the waves

Carrying me into old age while proffering life on the verge

My speech is still my own, not their standard parole

Theirs is not my country; flames and floods encircle me

七月六日,坐標漂浮於蒼海

一步跨入老年,歲月索居邊陲

但方言的古意不理會腔圓字正

我沒有國家,烈火和洪水將我包圍

The Eighteenth Day of the Fifth Lunar Month

of the Guimao Year of the Rabbit

5 July 2023

癸卯惡月十八,二零二三年七月五日

***

Book Signing, 17 July 2023, Beijing

Filmed by Tang Shizeng

***

‘And I Was Alive’

And I was alive in the blizzard of the blossoming pear,

Myself I stood in the storm of the bird-cherry tree.

It was all leaflife and starshower, unerring, self-shattering power,

And it was all aimed at me …Blossoms rupture and rapture the air,

All hover and hammer,

Time intensified and time intolerable, sweetness raveling rot.

It is now. It is not.

This is Mandelstam’s last known poem, written in 1937, the year before his death, en route to the Siberian Gulag to which he had been sentenced by Stalin. Mandelstam was last seen picking through garbage for scraps of food, dressed far too lightly for the bitter winter. In the last months of his life, just before he was sent to that cold and brutal place, he wrote this joyful poem, this fierce song.

—

The New Yorker, 11 June 2013

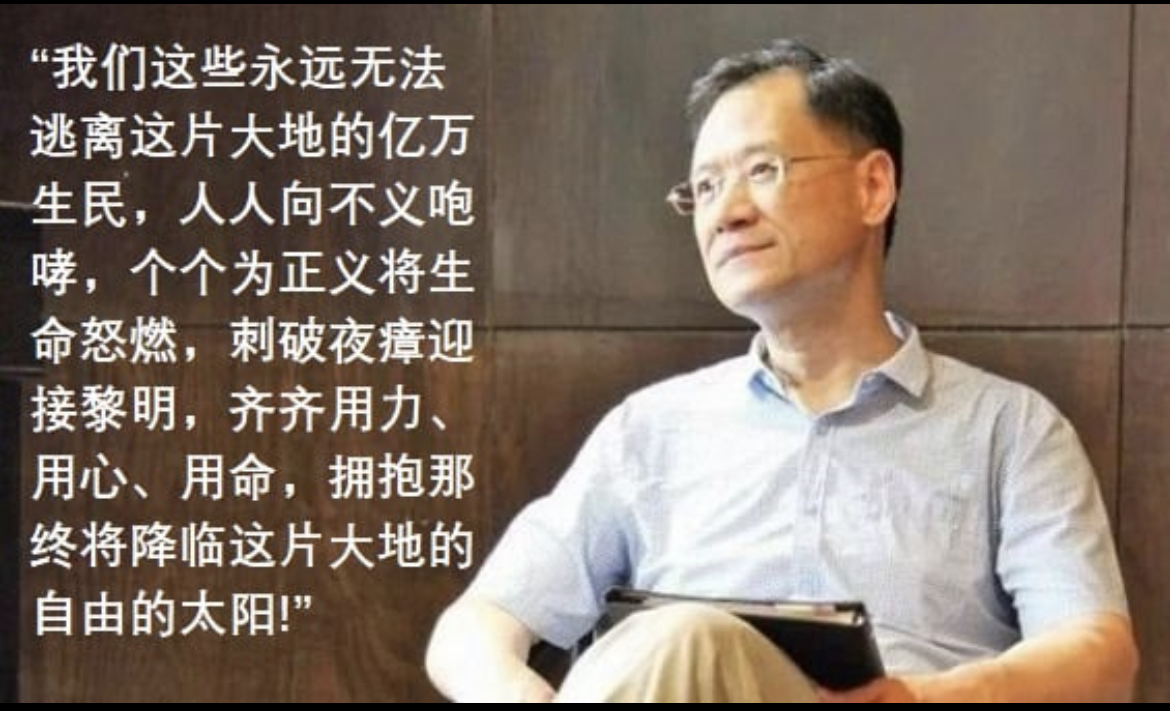

Hundreds of millions of people tied to this land, unable to flee, voice in a myriad of ways furious protest against all of the injustices. Our burning aspiration for decency constantly tries to dispel the darkness that would bury us all.

Working together these hearts and spirits can surely embrace the sunshine of freedom that one day will be ours.

— Xu Zhangrun

***

Xu Zhangrun’s Detention in July 2020, Two Essays

— from Xu Zhangrun vs. Tsinghua University in

the Xu Zhangrun Archive

- 無可奈何 — So It Goes, 6 July 2020

- Xu Zhangrun & China’s Former People, 13 July 2020

***

無可奈何 — So It Goes

The work of Professor Xu Zhangrun has featured in the virtual pages of China Heritage since August 2018. We were preparing to publish Professor Xu’s latest essay, one that he was writing to commemorate his famous Jeremiad — ‘Imminent Fears, Immediate Hopes’ 我們當下的恐懼與期待 — but have been prevented from doing so as the author was detained by the authorities on the morning of Monday 6 July 2020.

Professor Xu’s latest book — a collection of the six major critiques of the Xi Jinping government that he published during the 2018-2019 Year of the Dog — was slated to appear with City University of Hong Kong Publishing House in May 2020, and to feature at the Hong Kong Book Festival. Even before Beijing imposed its ‘Hong Kong Region Security Law’ on 1 July, Professor Xu’s publisher had been pressured to drop the book. In late June, Bouden House 博登書屋, a New York-based Chinese-language publishing house, produced the volume under the title《戊戌六章》. In response to a request from the author and the publisher, I suggested an English title that reflected the contents of the book: China’s Ongoing Crisis — Six Chapters from the Wuxu Year of the Dog. For details of this book, and the introduction, which Professor Xu invited me to write, see Bai Jieming 白杰明, ‘Six Chapters — One Hundred and Twenty Years‘, China Heritage, 1 January 2020.

It is rumoured that the appearance of that volume, along with the fact that Xu Zhangrun had repeatedly stated that he would continue to write and publish his views undaunted, led to the decision to silence him. In his work Professor Xu repeatedly warned that censorship and enforced silence — 箝口 qián kǒu — was having disastrous consequences for China, and by extension for the world.

The following essay is included in ‘Xu Zhangrun vs. Tsinghua University’, as well as being a chapter in our series ‘Viral Alarm’, itself a collection inspired by Xu Zhangrun’s ‘When Fury Overcomes Fear’, which he published in early February 2020. This material is also included in Lessons in New Sinology.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

6 July 2020

***

Recommended Reading:

- Nadezhda Mandelstam, Hope Against Hope, 1970, translated by Max Hayward

- Nadezhda Mandelstam, Hope Abandoned, 1974, translated by Max Hayward

As Clive James observed:

Hope Against Hope is about a gradual, reluctant but inexorable realization that despair is the only thing left to feel: it is the book of a process. Hope Abandoned is about what despair is like when even the memory of an alternative has been dispelled: the book of a result. The second book’s subject is spiritual desolation as a way of life. Several times, in the course of the text, Nadezhda proclaims her fear that the very idea of normality has gone from the world.

“I shall not live to see the future, but I am haunted by the fear that it may be only a slightly modified version of the past.”

— from Clive James, Cultural Amnesia (2007), p.416

Nadezhda Mandelstam died in 1980. ‘Nadezhda’ Наде́жда is Russian for ‘hope’.

***

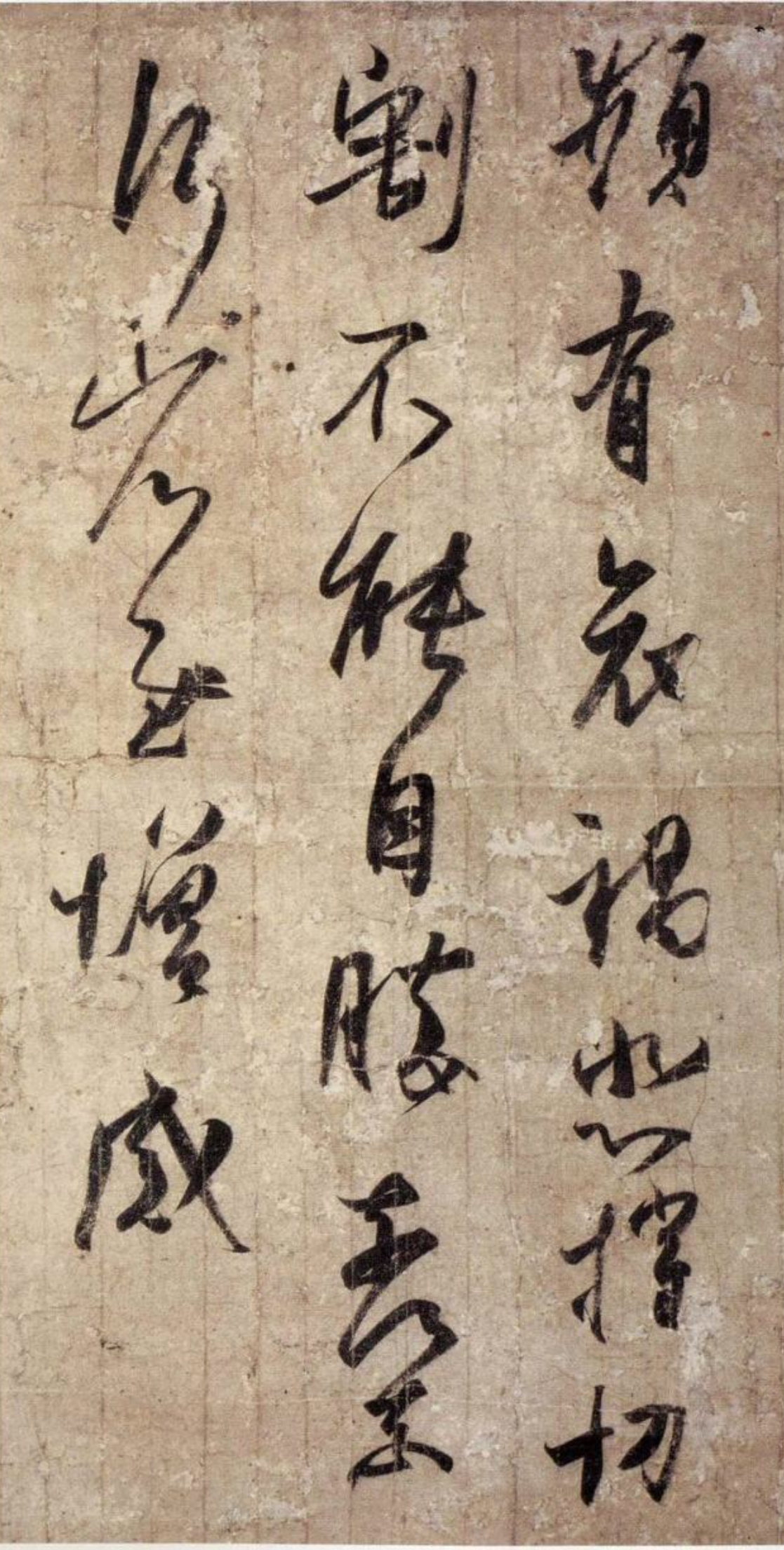

This fragment in the hand of Wang Xizhi (王羲之, 303-361 CE), who is famed as ‘The Sage of Calligraphy’ 書聖, reads:

‘Time and again grieving over calamity. Heartache as painful as a slashing blade; acute feelings overwhelm. Hope, then? Hope forlorn. Consolation only inflames despair.’

Our thanks to Annie Luman Ren 任路漫 for recommending this excruciatingly exquisite work.

— GRB

癩瘡疤

lài chuāngbā

Xi Jinping, the Chairman of Everything who is now also known in Chinese as ‘Xidalin’ 習大林 (Xi + Stalin), heads a regime that shares much in common with the fictional Ah Q, the most famous invention of Lu Xun. It seems apposite that Ah Q’s centenary will coincide with the anniversary of the founding of the Chinese Communist Party. The protagonist of ‘The True Story of Ah Q’ is known for his unerring ability to score own goals and for constantly snatching defeat from the jaws of victory, right up to the bitter end.

From ‘A Brief Account of Ah Q’s Victories’

… Ah Q who ‘used to be much better off’, who was a man of the world and a ‘worker’, would have been almost the perfect man had it not been for a few unfortunate physical blemishes. The most annoying were some patches on his scalp where at some uncertain date shiny ringworm scars had appeared. Although these were on his own head, apparently Ah Q did not consider them as altogether honourable, for he refrained from using the word ‘ringworm’ or any words that sounded anything like it. Later he improved on this, making ‘bright’ and ‘light’ forbidden words, while later still even ‘lamp’ and ‘candle’ were taboo. Wherever this taboo was disregarded, whether intentionally or not, Ah Q would fly into a rage, his ringworm scars turning scarlet. He would look over the offender, and if it were someone weak in repartee he would curse him, while if it were a poor fighter he would hit him. Yet, curiously enough, it was usually Ah Q who was worsted in these encounters, until finally he adopted new tactics, contenting himself in general with a furious glare.

It so happened, however, that after Ah Q had taken to using this furious glare, the idlers at Weizhuang grew even more fond of making jokes at his expense. As soon as they saw him they would pretend to give a start and say:

‘Look! It’s lighting up.’

Ah Q rising to the bait as usual would glare in fury.

‘So there is a paraffin lamp here,’ they would continue, unafraid.

Ah Q could do nothing but rack his brains for some retort. ‘You don’t even deserve… .’ At this juncture it seemed as if the bald patches on his scalp were noble and honourable, not just ordinary ringworm scars. However, as we said above, Ah Q was a man of the world: he knew at once that he had nearly broken the ‘taboo’ and refrained from saying any more.

If the idlers were still not satisfied but continued to pester him, they would in the end come to blows. Then only after Ah Q had to all appearances been defeated, had his brownish queue pulled and his head bumped against the wall four or five times, would the idlers walk away, satisfied at having won. And Ah Q would stand there for a second thinking to himself, ‘It’s as if I were beaten by my son. What the world is coming to nowadays!… ‘

Thereupon he too would walk away, satisfied at having won.

— from ‘The True Story of Ah Q’, in

Lu Xun: Selected Works, Volume I

translated by Yang Xianyi and Gladys Yang

Beijing, 1956, p.108-109

In his regular ‘Ways of the World’ 世道人生 column published in Apple Daily, Lee Yee remarked on 6 July 2020 that, overnight, Hong Kong had experienced a great leap in time from 30 June 2020 to 1 July 2049. ‘The thing about authoritarianism’, he observed, is that ‘orders issued on high are invariably pursued with excessive vigour by underlings.’ 專權政治的特點,是上頭有旨意,下面就加碼執行。After listing the restrictions on free speech and assembly that are multiplying by the day he says that upon learning that the Hong Kong Department of Education would soon be organising lessons related to the new security law for kindergartens, some online commentators said it was best to start from before the cradle by introducing ‘foetal state security education’.

‘It’s just like the ringworms on Ah Q’s head,’ Lee Yee observed about ever-encroaching censorship and self-censorship:

‘He refrained from using the word “ringworm” or any words that sounded anything like it. Later he improved on this, making “bright” and “light” forbidden words, while later still even “lamp” and “candle” were taboo. ” There are so many taboo or sensitive words on the Mainland Internet, and they continue to proliferate, that people often have to come up with roundabout ways to say the most commonplace things. Once you have rulers who think like Ah Q then they will continue to extend the absurdity endlessly.

Recently, Roy Tsui (Lam Yat-hei 林日曦) started his talkshow [on TVMost] by saying that since so many topics were now out-of-bounds, he could fit the whole two-hour program into a minute.

正如阿Q有癩痢頭,他忌諱人家說『癩』,以及一切近於『賴』的音,後來推而廣之,『光』也諱,『亮』也諱,再後來,連『燈』『燭』都諱了。」現在大陸網頁的敏感詞越來越多,多到連一句正常的話都要用一些不相干的同音字。阿Q心態到了掌權者那裏,效應就無限伸延。

林日曦在Talk show開場時說,兩個小時的節目現在一分鐘就講完,因為許多話題變得敏感了。

— Lee Yee, ‘At a Loss for Words’

李怡, ‘失語狀態’, 2020年7月6日

***

順我者昌

shùn wǒ zhě chāng

Professor Xu Zhangrun 許章潤 was detained on the morning of Monday 6 July 2020. Friends in Beijing reported that he had been taken into custody by police from Sichuan province and there was a suggestion that he would be charged with ‘soliciting prostitutes’ during a trip to Sichuan in the autumn of 2019 organised by his supporters.

The accusation of ‘soliciting prostitutes’ 嫖娼 has been used so frequently by the Chinese authorities that a new twist has been given to an old expression. The saying ‘submit to me and you will prosper; resist and you will perish’ 順我者昌,逆我者亡 shùn wǒ zhě chāng, nì wǒ zhě wáng first appears in the pre-Qin text Zhuangzi when the villainous brigand Liuxia Zhi 柳下跖, better known simply as Robber Zhi 盜跖, grants the obsequious Confucius (Kong Qiu 孔丘) an audience. ‘Let him come forward,’ bellows Zhi:

‘Confucius came scurrying forward, declined the mat that was set out for him, stepped back a few paces, and bowed twice to Robber Zhi. The robber, still in a great rage, sat with his legs sprawled out, leaning on his sword, eyes glaring. In a voice like the roar of a nursing tigress, he said,

“Qiu, come forward! If what you have to say takes my fancy, you will live. But if I take offense, you will surely die!” ’

盜跖曰:使來前。孔子趨而進, 避席反走,再拜盜跖。盜跖大怒,兩展其足,案劍瞋目,聲如乳虎,曰:丘來前。若所言順吾意則生,逆吾心則死。

Even before they met, Robber Zhi had sent word to the peripatetic thinker that:

‘Your crimes are huge, your offenses grave. You had better run home as fast as you can, because if you don’t, I will take your liver and add it to this afternoon’s menu!’

子之罪大極重,疾走歸。不然,我將以子肝益晝之膳。

— from ‘Robber Zhi’, Zhuangzi《莊子 · 盜跖》

The Complete Works of Chuang-tzu

translated by Burton Watson

with modification

Sun Yat-sen, the leader of the movement that led to the establishment of the Republic of China in 1912 and a man celebrated in the People’s Republic as the Father of the Nation used the expression when talking about the tide of progressive change and democratic revolution:

‘World progress is like a tidal wave. Those who ride it will prosper, and those who fight against it will perish.’

世界潮流,浩浩蕩蕩,順之則昌,逆之則亡。

— quoted in Barmé, ‘The Tide of Revolution’

China Heritage Quarterly, December 2011

In his powerful critiques of the vaunted ‘New Epoch’ under Xi Jinping, Xu Zhangrun aligns his own efforts with the long-frustrated impulses for progressive change and meaningful reform that date back to the Tongzhi Restoration of the 1860s. The Open Door and Economic Reform policies of post-Mao China are not the simple invention of Deng Xiaoping and his cohort of Communist leaders, rather they are a continuation of that early effort at national self-strengthening in the nineteenth century and the more mature attempts under the Republic of China to create a constitutional democracy promised by leaders as varied as Sun Yat-sen, Chiang Kai-shek and Mao Zedong. Here we would recall that, throughout the 1940s, Mao and fellows repeatedly promised in numerous public statements, speeches and interviews that China under the Communists would finally realise the democratic aims of the republican revolution of 1911. (For a collection of this material, see Xiao Shu 笑蜀 ed., Voices of History: solemn promises made half a century ago 歷史的先聲——半個世紀前的莊嚴承諾, published on the eve of the 1st October National Day in 1999 (and immediately banned).

Today, the ancient expression that ‘resistance is futile’, inspired by Robber Zhi’s thuggish rejection of Confucius’s appeal to morality has been reworked as:

順我者昌,逆我者被嫖娼。

shùn wǒ zhě chāng, nì wǒ zhě bèi piáochāng‘Submit to me and you will prosper; resist and you will be accused of soliciting prostitutes.’

When commenting on trumped up criminal charges in terms of the Chinese tradition it is handy to refer to the expression 莫須有 mò xū yǒu, ‘it could be true’, from the Song dynasty, or the older line 欲加之罪,何患無辭: ‘if you need to accuse someone of a crime, there’ll always be an excuse’. Given what Xu Zhangrun has called the 法日斯 (Legalistic-Fascist-Stalinist) nature of Xi Jinping’s China, I prefer a line attributed to Lavrentiy Beria, the head of Joseph Stalin’s state security administration:

‘Show me the man, and I’ll give you the crime.’

***

無可奈何

wú kě nài hé

The Chinese and English title of this chapter in our series ‘Viral Alarm’ — the theme of China Heritage Annual 2020 that was inspired by Professor Xu’s essay ‘Viral Alarm — When Fury Overcomes Fear’, published by ChinaFile on 10 February 2020 (for a bilingual version of this text, see China Heritage, 24 February 2020) — contains two literary references.

The first — 無可奈何 wú kě nài hé — appears in many texts from pre-Qin times onwards. Here we use it to refer to the concluding paragraph of the last essay that Xu Zhangrun published shortly before his detention:

‘Ultimately, we all confront a reality in which both Good and Bad are inextricably enmeshed; ours is a world damaged and inadequate, yet it is also one both of beautiful grandeur as well as of vile evil. It has come to be that our spirits inhabit this physical realm; we cope as best we can. There’s nothing for it but to move fitfully ever onwards. With each step we fulfill a life that is one third blithe ignorance, one third hopeful longing, and one final third that is an awareness: it is all simply what it is.’

畢竟,眼面前的人世,從來善惡交纏,永遠百孔千瘡,是那般美好而又邪惡。靈肉一具,一旦抛到人世,沒奈何混跡其中,只好往前挪步。一步一步,則人生三分,一分懵懂,一分渴望,更有一分無可奈何。

— from 無齋先生,‘蓬萊上國的漢方名醫’,2020年6月27日

For this writer, the expression 無可奈何 wú kě nài hé brings to mind a well-known poem by Yan Shu of the Song dynasty:

一曲新詞酒一杯,

去年天氣舊亭台。

夕陽西下幾時回。

無可奈何花落去,

似曾相識燕歸來。

小園香徑獨徘徊。

— 晏殊,《浣溪沙》

A cup of wine, songs with new lyrics,

Back in this pavilion, the same weather

The setting sun, what of the morrow?

Blossoms falling now, it is the way

Swallows from an earlier time return

And me, pacing in this small garden.

***

***

So It Goes

As we noted in the introduction to the Xu Zhangrun Archive compiled by China Heritage:

Since mid 2018, Professor Xu’s works have generated widespread discussion — and sotto voce debate — in China; they have also attracted international attention. In late March 2019, the Communist Party Committee that administers Tsinghua University, Xu Zhangrun’s employer, informed him via the university’s Human Resources Office that his wages would be further reduced; that he was stripped of all of the duties and privileges as a professor at Tsinghua, effective immediately; and, that a formal Investigation Group would scrutinise in detail his activities and writings. That investigation would inform the Party bosses, both at Tsinghua and in Zhongnanhai, how he would be further disciplined, cashiered or legally sanctioned.

Tsinghua University’s actions elicited an immediate response among some of Xu Zhangrun’s colleagues, ranging from disbelief to outrage. The news also caused consternation among many Tsinghua graduates and within the wider community. We have translated some of those reactions under the title ‘Xu Zhangrun vs. Tsinghua University’ in the Xu Zhangrun Archive.

In the persecution of Xu Zhangrun, which began surreptitiously at the behest of Chinese officialdom in August 2018, some of the country’s leading academics and intellectuals identify a ‘case study’ in the broader malaise affecting the country’s educational and cultural life. For years, it has been widely recognised that even the limited intellectual freedoms tolerated under previous Communist Party leaders were under increased threat as a result of the implementation of revived ideological controls throughout the publishing, academic and cultural spheres. With the circulation in 2013 of ‘Document Number Nine’, which alerted Party members about the infiltration of potentially destabilising ‘Western Values’, and in light of the trial and jailing in September 2014 of the respected, and moderate, Uyghur academic Ilham Tohti, even relatively naïve and hopeful independent-minded educators in the country’s universities and schools became tremulously aware of a rising tide of Communist Party obscurantism.

As we have repeatedly observed in China Heritage (and in our work that goes back to the early 1980s), however, the origins of the escalating crisis in Chinese education and culture has its origins in 1978. At that time, just as the Communists formally recognised the disaster their rule had visited upon the country and made a series of decisions that would form the basis of the four decades of what is known as ‘Economic Reform and Global Openness’ 改革開放, they also made a fateful adjudication: at the urging of Deng Xiaoping, Hu Qiaomu and other ideologues it was decided that the repression of outspoken academics, intellectuals and others in 1957, known as the ‘Anti-Rightist Campaign’ was, in essence, correct. Although over 300,000 men and women unjustly persecuted due to that campaign were eventually exonerated, the charges against five ‘Rightists’ were upheld and used as an excuse to justify the purge, one that had been overseen by Mao Zedong and coordinated by the logistical genius of Deng Xiaoping.

The affirmation of the political necessity of the 1957 purge of intellectual and cultural life — along with the Thought Reform Movement of the early 1950s that initially crushed academic freedom (for more on this, see ‘Ruling The Rivers & Mountains’) — has repeatedly given the Party ideological license to police university life as it sees fit. In re-imposing stricter ideological controls on education, and in particular in tertiary educational institutions, Xi Jinping’s party-state has merely been exercising prerogatives long ago made possible by major Party decisions announced in 1978, in 1987, and again after 4 June 1989 and repeatedly since then.

The ‘Xu Zhangrun Incident’, as some call it, is not merely about intellectual and academic freedom. Rather, it reflects the Xi-generated crisis in China’s ability to think about, debate and formulate ideas free of Communist Party manipulation, ideas that rightfully could and should benefit Chinese society, the nation and the world as a whole.

‘The Xu Zhangrun Archive’, or ‘Xu Case File’ offers some of the key works in Professor Xu’s recent oeuvre, as well as a sample of reactions to those works and an overview of his ongoing persecution.

***

On 30 March 2019 we received the text of a powerful article by an academic at Tsinghua University written in support of Professor Xu. We believed we had a clear understanding that China Heritage had permission to publish that text in translation. We were mistaken. Subsequent to publication, we were belatedly informed that the essay was, in fact, not intended for circulation outside the People’s Republic, nor indeed did the author want its existence to be reported. We were baffled by this surprising information, however, given the nature, and delicacy, of the situation, we were hardly in a position to protest ourselves, after all, it was impossible to determine what, if any, exogenous factors may have contributed to this untoward development.

We removed the translation and original text of that now self-silenced voice from China Heritage. The original Editorial Introduction and Dedication to the piece remain, as a 有字碑, a ‘stele covered in writing’ (as opposed to the famous ‘un-inscribed stele’ at the Tang-dynasty Qianling Tomb 乾陵無字碑), positioned to mourn silently such an untimely evaporation.

As 31 March 2019 marked the fiftieth anniversary of the publication of Kurt Vonnegut’s novel Slaughterhouse-Five, I found solace in the wise mantra-like statement used by the author to punctuate a dark meditation on the evil of the times:

So it goes.

— from ‘Silence + Conformity = Complicity’

China Heritage, 30 March 2019

***

碑銘

bēi míng

The future cannot be known; indeed there may come a time when this Gentleman’s work no longer enjoys preeminence, just as there are aspects of his scholarship that invite disputation. Yet his was an Independent Spirit and his a Mind Unfettered — these will survive the millennia to share the longevity of Heaven and Earth, shining for eternity as do the Sun, the Moon and the very Stars themselves.

來世不可知者也,先生之著述,或有時而不彰。先生之學說,或有時而可商。惟此獨立之精神,自由之思想,曆千萬祀,與天壤而同久,共三光而永光。

— Chen Yinque 陳寅恪 on

Wang Guowei 王國維

3 June 1929(from ‘The Two Scholars Who Haunt Tsinghua University’, China Heritage, 28 April, 2019)

Xu Zhangrun, on commemorating Wang Guowei and Chen Yinque at Tsinghua University:

***

In Zhuangzi, Robber Zhi ends his encounter with Confucius by declaring:

‘What you have been telling me — I reject every bit of it! Quick, now — be on your way. I want no more of your talk. This “Way” you tell me about is inane and inadequate, a fraudulent, crafty, vain, hypocritical affair, not the sort of thing that is capable of preserving the Truth within. How can it be worth discussing!’

Confucius bowed twice and scurried away. Outside the gate, he climbed into his carriage and fumbled three times in an attempt to grasp the reins, his eyes blank and unseeing, his face the color of dead ashes. Leaning on the crossbar, head bent down, he could not seem to summon up any spirit at all.

Returning to Lu, he had arrived just outside the eastern gate of the capital when he happened to meet Liuxia Ji [Robber Zhi’s brother].

‘I haven’t so much as caught sight of you for the past several days,’ he said, ‘and your carriage and horses look as though they’ve been out on the road — it couldn’t be that you went to see my brother Zhi, could it?’

Confucius looked up to heaven, sighed, ‘I did.’

‘And he was enraged by your views, just as I said he would be?’

‘He was,’ said Confucius. ‘You might say that I gave myself the burning moxa treatment when I wasn’t even sick. I went rushing off to pat the tiger’s head and plait its whiskers — and very nearly didn’t manage to escape from its jaws!’

丘之所言,皆吾之所棄也,亟去走歸,無復言之。子之道,狂狂汲汲,詐巧虛偽事也,非可以全真也,奚足論哉。孔子再拜趨走,出門上車,執轡三失,目芒然無見,色若死灰,據軾低頭,不能出氣。歸到魯東門外,適遇柳下季。柳下季曰:今者闕然數日不見,車馬有行色,得微往見跖邪。

孔子仰天而嘆曰:然。

柳下季曰:跖得無逆汝意若前乎。

孔子曰:然。丘所謂無病而自灸也。疾走料虎頭,編虎須,幾不免虎口哉。

— from ‘Robber Zhi’, Zhuangzi《莊子 · 盜跖》

The Complete Works of Chuang-tzu

translated by Burton Watson

with modification

Those who are caught in the jaws of Xi Jinping’s New Era cannot expect such a fortuitous escape from the tiger’s maw.

***

Xu Zhangrun & China’s Former People

Former People, Бывшие люди (Byvshiye lyudi), is the title of a novella by Maxim Gorky published in 1897. Known in English translation as Creatures That Once Were Men, Gorky’s story would inspire the Bolsheviks to employ the term ‘Former People’ when speaking about survivors of the defunct ancien regime. Their number included members of the aristocracy, the clergy, the Tsarist military and bureaucracy. As individuals whom the progress of history had cast aside, Former People were treated as ‘has-beens’ in every regard.

I had the good fortune to be befriended by a number of China’s Former People from just after the death of Mao Zedong in late 1976. As many of those men and women were gradually recognised as now being members of ‘The People’ during the early post-Mao years, I would also come to know others who were well on the way to joining the ranks of a whole new category of China’s Former People.

***

As I noted in 1987, despite their pursuit of Economic Reform Policies and Openness to the World, the Chinese Communists never intended to abandon, or even seriously reform, the repressive mechanisms of the state that had shored up their power over the decades. In fact, the proliferation of Chinese Former People, that is men and women of conscience who were consigned to the party-state’s memory hole, has been an ineluctable fact from the time of the arrest of Wei Jingsheng 魏京生 in early 1979 and the bulldozing of the Xidan Democracy Wall in Beijing not long after.

Then, with the purge of Party General Secretary Hu Yaobang in January 1987 (see ‘Memory Holes, Old & New’), the post-Mao intellectual and cultural landscape has been increasingly scarred by the vestigial presence of ‘China’s Former People’.

As I observed in October 2018:

Under Xi Jinping, head of the party-state-army of China’s People’s Republic, the country’s memory hole industry has enjoyed a new boom. It is an enterprise devoted to the obliteration of the images, memories and works of individuals deemed to be persona non grata. China’s memory holes are generously engineered to disappear ideas, events and even discomfiting eras. They gobble up dissidents and their writings; they also devour the enemies within, men and women purged for real or concocted crimes against the Party. Moreover, from 2017, the international academic industry also learned that some of their publishers were collaborating in the memory hole industry by deleting research work that was displeasing to the Communist authorities from the online journals and books that they ‘sold into’ the mainland Chinese market (see ‘Burn the Books, Bury the Scholars!’, China Heritage, 22 August 2017).

Under Mao, the most common term for ‘former people with Chinese characteristics’ was ‘The Five Black Categories of People’ 黑五類. These were:

- Landlords 地主;

- Rich Farmers 富農;

- Counter-revolutionaries 反革命;

- Bad Elements 壞份子; and,

- Rightists 右派.

In 1989, the maw of the state disappeared so many people and events that some writers would speculate that surely the country was suffering from a form of collective amnesia. While the names of some student activists, leading intellectuals and a few workers are known, the vast number of 1989 Former People — those killed, jailed or punished in various ways over the years — are rarely known and not acknowledged publicly.

The writers and activists Dai Qing 戴晴 and Liu Xiaobo 劉曉波 were involved in the mass protest movement of April-June 1989. At the time, both were prominent public figures and prolific authors who were at the height of their fame and influence. In the wake of the 4th of June Beijing Massacre, both were jailed. Even though they were eventually released, thereafter their formerly vibrant careers were obliterated (their works, however, continue to be published in Hong Kong and Taiwan). For their audiences in the People’s Republic, however, they were for all intents and purposes no better than Former People, or non-entities. As Dai Qing said to me in late 1990:

‘Well, they may have let me out of a small jail, but in reality I’m still in the vast jail that is China.’

***

Xu Zhangrun 許章潤, an outspoken critic of the Xi Jinping government, was detained on Monday the 6th of July 2020 at his apartment in the western suburbs of Beijing. He was released after six days without any formal charge being laid on Sunday the 12th of July. Ever since publishing ‘Imminent Fears, Immediate Hopes’ 我們當下的恐懼與期待, a breathtaking jeremiad, in late July 2018, he has been China’s most recalcitrant Former Person. In late October, unbowed by pressure from his employer Tsinghua University to remain silent, he wrote:

In the normal course of events, it is commonplace for bookish scholars to give voice to their political views, and for those without political ambition to express all kinds of [arrant] opinion. It is simply par for the course; nothing more than jus natural — a natural right. But living as one does in a period of political irregularity during what is a momentous era of transformation, it was but inevitable that my writing was broadcast widely on the Internet, thereby offending against the taboos of the autocrats and causing discomfort to the hardened carapace of the totalitarians. … Eyes wide open I was fully aware of what I was doing and psychologically prepared for anything untoward that might befall me. That’s why I was not particularly perturbed by the initial wave of ‘gentle breezes and mild rains’ that consisted of the elimination of online material related to me and the blocking of my name. At first, I simply took no notice; moreover, it did not disturb me unduly. The wondrously efficacious methods of the age-old Qin tyranny are now but shabby techniques employed by the Newly Ennobled One. Although separated by two millennia, and despite variations on the theme, there has been no significant evolution [in how autocratic Qin-era methods are being imposed on today’s reality]. All in all, it comes down to the same old thing: ‘make people keep their mouths shut’. So what is happening to me is hardly a surprise!

— from Xu Zhangrun, ‘And Teachers, Then? They Just Do Their Thing!’

China Heritage, 10 November 2018

But Xu Zhangrun refused to keep his mouth shut.

In the vaunted ‘New Epoch’ of Xi Jinping, the five main problematic social groups, or ‘black categories’, are rights lawyers, underground religious activists, dissidents, Internet leaders (influencers), as well as various vulnerable groups. Perhaps ‘Upright Professors and Outspoken Educators’ will become another category in the country’s ever-expanding register of Former People.

***

***

Our series ‘Viral Alarm’ — which is also the theme of China Heritage Annual 2020 — is inspired by ‘When Fury Overcomes Fear’, an essay by Xu Zhangrun related to the coronavirus and China’s ongoing leadership crisis.

As ever, I am grateful to Reader #1 for his timely suggestions and corrections. He also reminded me of a saying cum-prophecy current around half a century ago:

‘It will someday be recorded in footnotes that in the Age of Sakharov there lived and ruled for a time the minor politician Leonid Brezhnev.’

***

Note: All translations are mine, unless otherwise indicated.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

13 July 2020

劉曉波祭日

The Third Anniversary of Liu Xiaobo’s Death

***

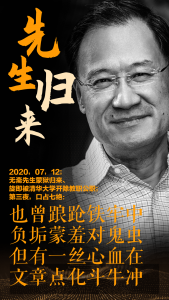

On 14 July 2020, a message was circulated on the Chinese Internet containing a poem written by Xu Zhangrun:

‘On 12 July, the Master of Erewhon Studio returned. Thereupon, Tsinghua University stripped him of his job and cancelled his professional ranking. On the third night of his release [the 14th of July], out came an impromptu verse:

Stumbling thence into their clutches, imprisoned,

Reputation befouled, vile minions still besmirch.

So long as blood yet courses through these veins,

Revelatory essays surge forth, energy undiminished.

也曾踉蹌鐵牢中

負垢蒙羞對鬼蟲

但有一絲心血在

文章點化斗牛衝

(The expression 斗牛 dǒu niú in the last line refers to the constellations 斗宿 dǒu xiù (Dipper) and 牛宿 niú xiù (Ox), two mansions or lodges in the northern Dark Warrior 玄武 quadrant of the sky, one that relates to protection and longevity.)

***

Count Alexander Ilyich Rostov is the protagonist of A Gentleman in Moscow, a novel by Amor Towles published in 2016. The action of the book starts with a session of the ‘Emergency Committee of the People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs’ convened on 21 June 1922. Following a short interrogation, the commissars tell the Count that:

‘… our inclination would be to have you taken from this chamber and put against the wall.’

But there are ‘those within the senior ranks of the Party’ who remember Rostov for having written a powerful poem attacking the autocratic old regime. They therefore regard him as something of a pre-revolutionary hero. In recognition of that contribution Rostov is granted leave to return to the Metropol Hotel, where he has been residing since 5 September 1918. ‘But make no mistake’, the commissars warn:

‘should you ever set foot outside of the Metropol again, you will be shot.’

In the blink of an eye, Count Rostov has become a Former Person.

— Amor Towles, A Gentleman in Moscow

New York: Viking, 2016

***

Related Material:

- ‘The Pity of It’, China Heritage, 13 July 2017

- Xu Zhangrun 許章潤, ‘In Memoriam — Shrouds of Ice on a River Incarnadine’, China Heritage, 4 June 2020

- The Editor, ‘無可奈何 — So It Goes’, China Heritage, 6 July 2020

- Xu Zhangrun 許章潤, ‘I Will Not Submit, I Will Not Be Cowed’, China Heritage, 10 October 2019

- Xu Zhangrun 許章潤, ‘Abiding Until Daybreak’, China Heritage, 30 September 2019

- Various, ‘A Writer’s Desk & the Vastness of China — 1989, 2019’, China Heritage, 4 June 2019

- The Xu Zhangrun 許章潤 Archive, China Heritage, 1 August 2018-

- G.K. Chesterton, ‘Introduction to Creatures That Once Were Men’

Media Reports:

- Chris Buckley, ‘Seized by the Police, an Outspoken Chinese Professor Sees Fears Come True’, The New York Times, 6 July 2020

- Chris Buckley, ‘Outspoken Chinese Professor Is Said to Be Released From Detention’, The New York Times, 12 July 2020

- Gao Feng, ‘China’s Tsinghua University Fires Outspoken Lecturer Xu Zhangrun’, translated and edited by Luisetta Mudie, Radio Free Asia, 14 July 2020

- Josephine Ma and Guo Rui, , South China Morning Post, 18 July 2020

- ‘清華大學向許章潤發出開除處分文件 稱其違反教師行為準則’, 《自由亞洲電台》, 2020年7月18日

Commentary:

- 白信, ‘自由主義的哀歌 清華大學與北京「最後一個士大夫」脫鈎’, 《德國之聲》,2020年7月15日

- 時事大家談, ‘專訪林培瑞和黎安友:美中關係為何在習時代翻船?’,《美國之音》,2020年7月15日

- 時事小品, ‘隔空嫖娼’,《新唐電視》, 2020年7月20日

***

What the Fate of Xu Zhangrun

Means for Thinking China

Geremie R. Barmé

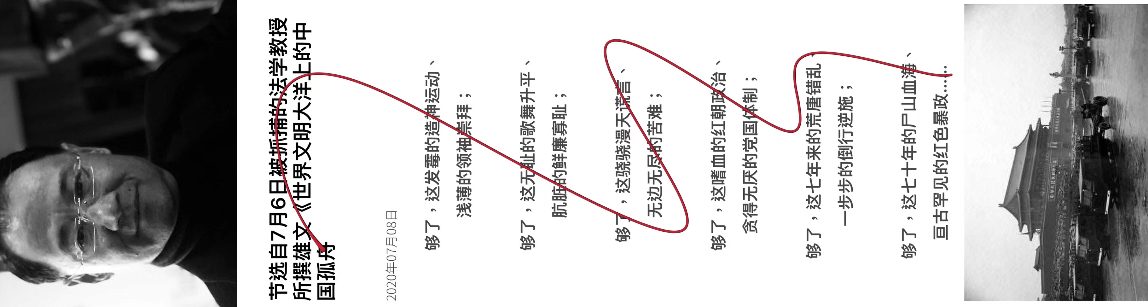

‘Enough already of your odious deification and the vacuous new personality cult,’ 够了,这发霉的造神运动、淺薄的领袖崇拜 wrote Xu Zhangrun, China’s most famous critic of Xi Jinping and his authoritarian rule, who was detained at his apartment in the western suburbs of Beijing on Monday 6 July 2020. Writing in the powerful style for which he has become famous — one that melds classical turns of phrase and biting humour to create a powerful form of polemic — Xu continued:

‘Enough of the shameless hosannahs lauding peace and prosperity that serve only to cloak a corrupt reality.

‘Enough of the choking lies and the boundless suffering that they conceal, and enough of this blood-thirsty Red Dynasty and its rapacious party-state.

‘Enough, I say: over the past seven years [the period Xi Jinping has been in office] we’ve had a bellyful of your absurd policies and the relentless march into the past.

‘Enough, too, of the seven long decades in which you have piled up mountains of corpses and shed blood enough to fill a sea. Yours is the handiwork of a tyranny the likes of which the world has rarely seen.’

够了,这无耻的歌舞升平、肮脏的鲜廉寡耻;够了,这骁骁漫天谎言、无边无尽的苦难;夠了,这嗜血的红朝政治、贪得无厌的党国体制;够了,这七年来的荒唐错乱、一步步的倒行逆施;够了,这七十年的尸山血海、亙古罕見的红色暴政……

These are the closing lines of ‘China, a Lone Ship of State on the Vast Ocean of Global Civilisation’, an essay Xu published on 21 May. It was the latest in a series of lengthy critiques of that country’s ongoing political crisis that Xu began three years ago. Friends in Beijing speculate that one of the reasons for his sudden detention was that he had just released a collection of those fiery essays with a small independent Chinese publishing house in New York — originally slated to appear in May through Hong Kong City University Press, that publisher had been pressured by authorities to drop the project. Instead, Bouden House 博登書屋 produced it under the Chinese title《戊戌六章》, literally, ‘Six Chapters from the Wuxu Year’, the English title is China’s Ongoing Crisis — Six Chapters from the Wuxu Year of the Dog (for details of this book, and for the introduction and table of contents, see ‘Six Chapters — One Hundred and Twenty Years’, China Heritage, 1 January 2020). He released the book in direct contravention of direct orders from his employer, Tsinghua University, which some call ‘China’s MIT’.

For years, Xu Zhangrun had warned of the invasive presence of Communist Party ideology on his campus, and in his increasingly incensed writings he identified the autocratic rule of Xi Jinping — the man he lambasts as ‘The Axelrod’ 當軸 — as the culprit in chief. I translated his most famous critique of the Xi Jinping era — ‘Imminent Fears, Immediate Hopes’ — which appeared in late July 2018 and, on the eve of his detention on 6 July, Xu told me that he was preparing a new essay to commemorate that landmark work.

For his continued defiance, Tsinghua had suspended Xu from his job as a professor in its law faculty in March last year. He was also banned from contact with students and his income was drastically reduced. The university also forbade him from speaking to the media, writing, engaging in research or publishing any work. They also placed him under formal investigation for writing and lecturing on topics that contravened an infamous 2012/2013 secretive directive known as ‘Document Number Nine’. Circulated to the Communist Party committees that control China’s universities, the document banned a host of topics related to potentially destabilising ‘Western values’ including human rights, media freedom, judicial independence and constitutionalism.

Xu was undaunted and, as we noted in the introduction to this essay, he continued to speak out:

‘It is commonplace for bookish scholars to give voice to their political views, and for those without political ambition to express all kinds of opinion. It is simply par for the course; nothing more than jus natural — a natural right. … Eyes wide open I was fully aware of what I was doing and psychologically prepared for anything untoward that might befall me. … It comes down to the same old thing: ‘make people keep their mouths shut.’ So what is happening to me is hardly a surprise!’

During his period in custody Tsinghua University rushed through a final determination on his status and, on the second day of his incarceration a delegation from the university personnel department visited him to read out an administrative sentence adjudged on the spurious basis of ‘moral turpitude’ 道德敗壞: he was stripped of his job; his professional status as a professor was invalidated; his pension was taken away; and, health coverage was withdrawn. In the event, Professor Xu was freed a few days later and, according to friends, he therefore speculated that his detention was merely a trial run. (He received a hard copy of Tsinghua’s ‘letter of cancellation’ dated 15 July 2020 delivered by courier following his release.) It seemed possible that the authorities, taken aback by the furore both in China and overseas resulting from his sudden disappearance, had thought better of their precipitate action. Now they had withdrawn to regroup; their next gambit could well be both more decisive, and final.

Xu Zhangrun’s situation reflects the broader fate of intellectual and political life in China today. But, as Xu himself observed, quoting a famous saying: ‘It’s easier to dam a river than to silence people.’ 防民之口 , 甚於防川.

Following his suspension by Tsinghua, dozens of friends and colleagues protested in essays, classical-style poems and, in one case, a folksong. Their number included Zi Zhongyun 資中筠, a prominent authority on Sino-US relations retired from the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Zhang Weiying 張維迎 and Zhang Qianfan 张千帆 legal scholars at Peking University, as well as the noted sociologist Guo Yuhua 郭於華. His supporters — as well as hundreds who signed petitions in support that were launched both in- and outside China — praised him as a champion of ‘an independent spirit and an unfettered mind.’

‘An independent spirit and an unfettered mind’ 獨立之精神, 自由之思想 is an expression used by the Tsinghua University historian Chen Yinque 陳寅恪 in an epitaph that he wrote in 1929 for his colleague Wang Guowei 王國維, a renowned literary scholar who had committed suicide. (For details, see ‘The Two Scholars Who Haunt Tsinghua University’, China Heritage, 28 April, 2019.) Chen’s encomium was etched on a stele set up on the Tsinghua campus paid for by students of the two scholars. It stood there until the iconoclastic frenzy of the Cultural Revolution, when it ended up as a bench in a science lab. The stele was set up again in 1985, just as China’s universities were becoming entwined with international academic partners. Eventually, as intellectual life in China once again flourished, Chen Yinque’s credo about Free Thought and the Independent Spirit became something of a credo, not only at Tsinghua, but also at universities and for educators throughout the People’s Republic. Today, the message of Chen’s mantra is under siege once more, just as it had been throughout the Mao era.

On the 108th anniversary of the founding of Tsinghua University on 28 April 2018, a month after Xu had been put under investigation, he and his supporters gathered at the Chen Yinque-Wang Guowei stele to pay tribute to the endangered tradition of free thought in China. The group also paid their respects to Xu Zhangrun who had recently been prevented from seeking medical treatment in Japan. Xu recorded a video message that was posted by Voice of America:

‘… graduates of Tsinghua University have come to pay their respects to Masters Wang and Chen as an act of reverence for our intellectual forefathers and as a way of showing support for the continuing importance of having ‘A Spirit of Independence and a Mind Unfettered’. It is a message that has been obstructed by various things for far too long. It is exactly what China needs today more than ever.’

In late 1953, with the support of no less a figure than Mao Zedong himself, Chen Yinque had been offered a position to lead a new history research institute in the re-established Academia Sinica in Beijing (the original academy had relocated to Taiwan from Nanjing at the time of the 1949 Communist victory on the Mainland). In a statement in which he declined the invitation, Chen referred to the 1929 epitaph that he had written for Wang Guowei: ‘It remains my belief,’ he told the emissary from Beijing, ‘that the most important qualities for a scholar to possess are intellectual freedom and an independent spirit.’ Moreover, he said: ‘To achieve a truly independent spirit and real free will requires a struggle, it is in fact a life-and-death struggle.’ Anyway:

‘I read Das Kapital [in 1912] … and I concluded that if one accepted the Marxist-Leninist worldview it would not be possible to pursue scholastic research.’

***

***

Xu Zhangrun’s criticisms of the Xi Jinping era began long before he published his famous July 2018 jeremiad; and he has long been aware of the price he would eventually have to pay for his daring. In the introduction to a volume of his essays published in 2016, Xu wrote:

My youth was spent in poverty and hunger; it was a time when silence reigned supreme and society was fearful even of private exchanges. We lived in trembling fear and it was only in my middle years that I no longer had to worry about everyday essentials.

I have witnessed the changing seasons: the gradual passing of winter and the promise of spring; as well as the taste of bitterness as it gives way to sweet possibility, new hope flickered alive in dead embers. There was no telling that as events unfolded, for the truth still lay buried under the surface; there was backtracking aplenty and always the possibility of a dramatic political reversal. So I was still fearful in my heart. Untrammeled sleep has always eluded me, invariably I have found myself lost in thought even at the midnight hour and the urge to express myself was never far away.

筆者半生已過,從少幼溫飽不繼,寒蟬僵鳥,道路以目,觳觫存世,到中年衣食無憂,眼見這方水土冬去春回,苦盡甘來,寒灰更然,卻不料,時勢遷轉,尚未水落石出,抑或有所迂迴,彷彿岸谷之變,故而依舊心存危懼。危懼寸心,遂寢食難安,午夜沈吟,總想傾述。

I was convinced that no matter what punishment may eventually be visited upon me, I would surely have the right to raise my voice in baleful protest. To the end of my days I will be here in this land, subject both to its bitter cruelties and enjoying its embracing charms, its successful advances as well as its retreats. Our lives are all bound up with it, and so too it will effect the myriad of generations to come. There is nowhere we can flee from this fate and it is impossible to turn a blind eye to our reality.

We may enjoy lives of boundless possibility, but only if we speak out. After all, people are voluble creatures and you’ll shrivel up and die if you’re forced to hold your tongue. I am just an insignificant teacher, someone for whom talking is their stock in trade. So, I must have my say and I will speak out until I have given voice to everything that I feel I must. And I will say it all clearly; I will speak up so that everyone can hear me — for this is both my profession and my duty.

至少覺得,若遭刑戮,也有張口喊痛的權利。此生有盡,既棲息此方水土,則其冷暖榮枯,關係身家性命,影響千秋萬代,無法逃避,不可能假裝看不見,則人生無盡,有話說話,人是說話的動物,不說會憋死,身為一介教書匠,說話,把該說的話說出來,說清楚,說給大家聽,蔚為天職。

However, friend, if you are one whose mouth is always filled with paeans of praise, you have no real regard for this land and its fate. You are nothing more than a transient grifter. Behind all of that sound and fury you are nothing but a sham. How could you expect me to have any respect for you?

是呀,若果你口中總是贊美詩,可並非與這塊土地生死相連,不過暫居撈金,而振振有辭,裝神弄鬼,朋友,你讓我怎麼敬服你呢?!

After all, we all confront the need to cultivate ourselves even as we are dwarfed by the dark mountains [of human existence]. Nothing for it but to live, strive.

而且,化性起伪,怀山襄陵,我们怎么活呢?

— from ‘Introduction to a New Edition’

許章潤,《國家理性與優良政體》

香港城市大學出版社, May 2016

***

***

The defense of academic freedom in China today — one spearheaded by Xu Zhangrun over the past three years — recalls that stele on the Tsinghua campus, just as those who support Xu repeatedly quote that epitaph written for Wang Guowei ninety years ago:

‘The future cannot be known; indeed there may come a time when this Gentleman’s work no longer enjoys preeminence, just as there are aspects of his scholarship that invite disputation. Yet his was an Independent Spirit and his a Mind Unfettered — these will survive the millennia to share the longevity of Heaven and Earth, shining for eternity as do the Sun, the Moon and the very Stars themselves.’

The plangent fate of Xu Zhangrun, one of China’s new Former People, reflects the tragic reality that the lights of independent thought and the free spirit have long been on the wane in China. For two long years Tsinghua University has given license to, as well as enacted, a shameful ‘death by a thousand cuts’ 千刀萬剮 of a paragon. Xu Zhangrun will live on in Chinese history and letters as a giant in the company of Wang Guowei and Chen Yinque while his tormentors will be consigned to infamy.

For those who now choose to continue collaborating with Tsinghua University, be they in China or at international academic institutions, a stark choice looms, one between the convenience of mutual benefit on the one hand and the challenge posed by intellectual probity on the other. Xu Zhangrun chose moral clarity and in doing so he rejected the acquiescence of silence.

***

The brazen bell is smashed and discarded;

The earthen crock is thunderously sounded

黃鐘譭棄,瓦釜雷鳴

‘Is it better to risk one’s life by speaking truthfully and without concealment, or to save one’s skin by following the whims of the wealthy and highly placed?

‘Is it better to preserve one’s integrity by means of a lofty detachment, or to wait on a king’s mistress with flattery, fawning, and strained, smirking laughter?

‘Is it better to be honest and incorruptible and to keep oneself pure, or to be accommodating and slippery, to be compliant as lard or leather?

‘Is it better to have the aspiring spirit of a thousand li stallion, or to drift this way and that like a duck on water, saving oneself by rising and falling with the waves?

‘Is it better to run neck and neck with the swiftest, or to follow in the footsteps of a broken hack?

‘Is it better to match wing-tips with the flying swan, or to dispute for scraps with chicken and ducks?

‘Of these, alternatives, which is auspicious and which is ill-omened? which is to be avoided and which is to be followed?’

— from ‘Divination’ 卜居, attributed to Qu Yuan 屈原

trans. David Hawkes, Songs of the South, pp.204-205

***

***

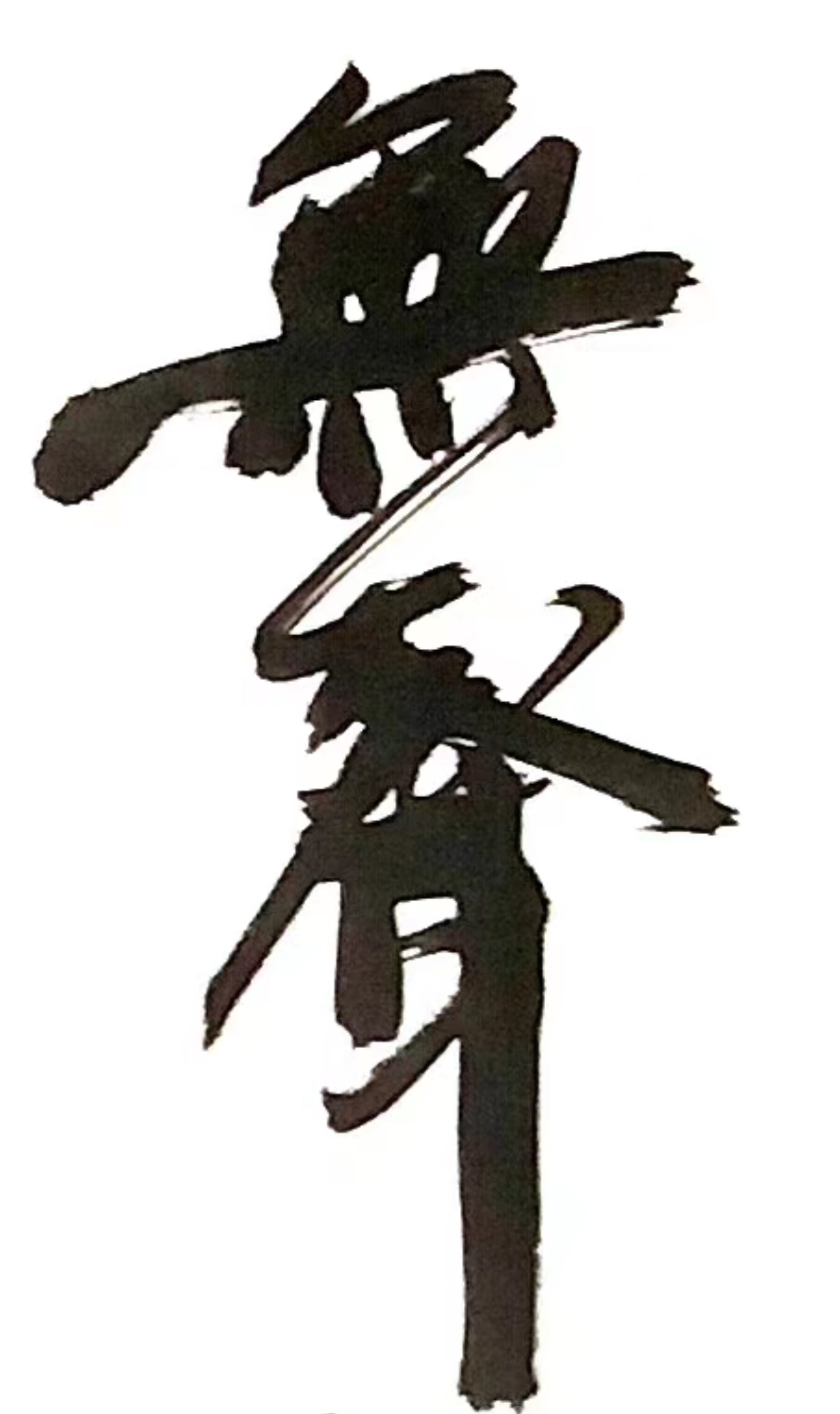

Erewhon Studio 無齋

From 2016, Xu Zhangrun wrote most of his most pointed work in his ‘Erewhon Studio’ 無齋 at Tsinghua University in Beijing. The name 無齋 wú zhāi literally means ‘The Studio That Isn’t’. I translate it as ‘Erewhon’, a reference to the title of a novel by Samuel Butler published in 1872. A satire of Victorian social mores, the book was about ‘nowhere in particular’, ‘erewhon’ being a reverse working of the word ‘nowhere’. Butler’s fictional ruminations are thought to have been inspired in part by his time in New Zealand.

The name ‘Erewhon Studio’ thus links Xu Zhangrun’s prose, with its satirical undertow and utopian aspiration, and New Zealand, a distant island nation where China Heritage is produced.

Of course, Xu Zhangrun’s essays, created ‘no-where’, are really about ‘now-here’.

Since being cashiered by Tsinghua University in early July 2020, and ejected from the Tsinghua campus, Professor Xu’s Erewhon Studio has migrated to his humble apartment some forty kilometres to the west.