The Other China

學無中西之別也,無古今之別也,

唯有學與不學之別也。

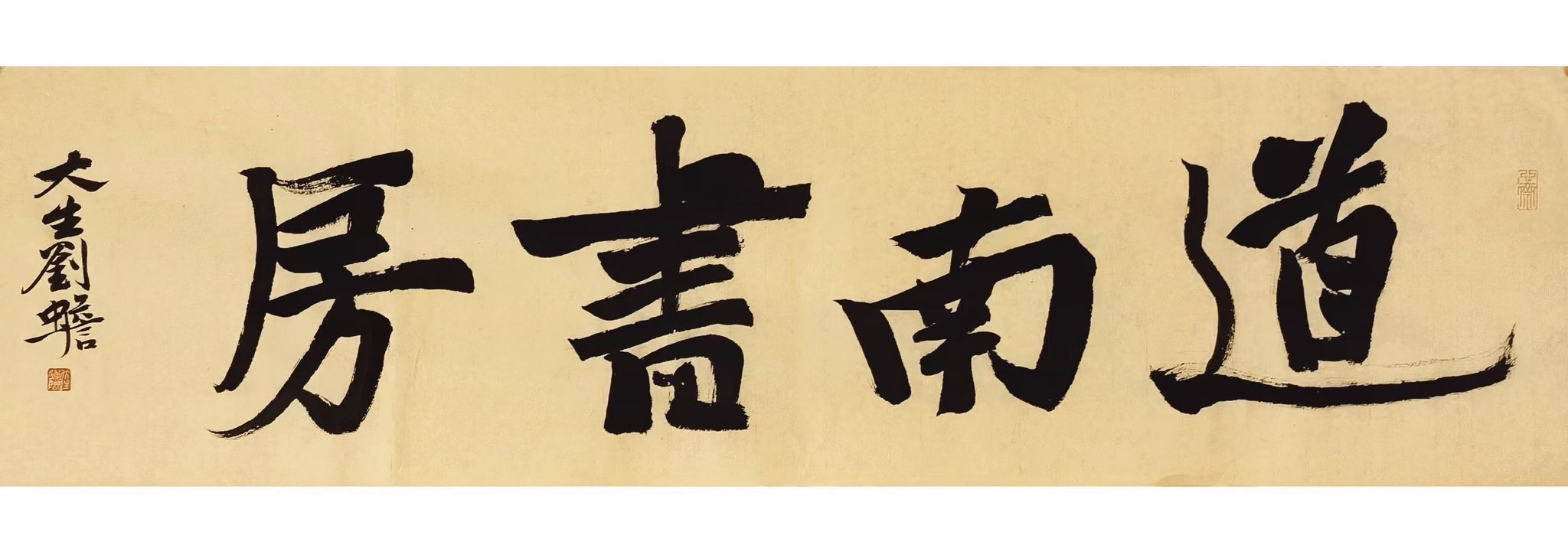

Liu Chan 劉蟾, who also goes by the pen name Dasheng 大生, is a writer, scholar and calligrapher. Born in Shaanxi, he lives in Beijing where he edits The Chinese Study 中國書房. Liu Chan’s work has often featured in The Other China (see below). Here he discusses 書房精神 shūfáng jīngshén, an expression that we translate as ‘studiolo of the heart’.

***

In our discussion of the Studio, or Scholar’s Study — 齋 zhāi — published in 2008, we observed that:

The Studio is a creative space that can exist as the name of a writer, the physical location of a myriad of cultural pursuits, a shifting abode of no fixed address, or an imaginary retreat from the world. The heritage of the Studio is one that remains vital for creative Chinese writers and artists; it continues to enliven the work and mental lives of many. The tradition of naming and celebrating Studios continues—for the wealthy and pretentious who would lay claim to some role in preserving or reinventing Chinese culture, as well as for the harried scholar or writer, many of whom live in towns and cities scattered throughout the Chinese world, and internationally, work on in often cramped studies, pursuing the life of the mind and their cultural inheritance. Today, Studio names are used by book-sellers and parvenus, by the newly rich Chinese artists who churn out paintings in large ateliers, minions producing their brand art work en masse for a greedy international market. The Studio can be the crass site of market capitalism, but the ineffable dimension of the Studio as a private space for individual pursuit remains. The Studio exists too in the imaginations and fantasies of those who attempt to appreciate and bring a creative recollection to the world that produced much of the finest literature and art of traditional China. The Studio dwells too in the minds of those who engage with the world of Chinese letters through translation.

In that same year, in his Erewhon Studio, 無齋 wú zhāi, at Tsinghua University in Beijing, the scholar Xu Zhangrun 許章潤 wrote:

Above a heavenly vault o’erstretched with books,

below the expansive earth spread with volumes.

A desk to read tucked beneath the skies,

a place to write supported by the ground.

I’m delighted that I will always have a desk for reading and writing.

It can always be found; it is everywhere:

between those lofty skies and this sustaining earth.

這天,是書;這地,是書。

這天,是書桌;這地,是書桌。

哈,啊,我家書桌在天地間。

— from A Writer’s Desk & the Vastness of China

***

***

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

5 March 2025

***

Related Material:

- Jao Tsung-I on 通 tōng — 饒宗頤與通人, 23 June 2017

Liu Chan in The Other China:

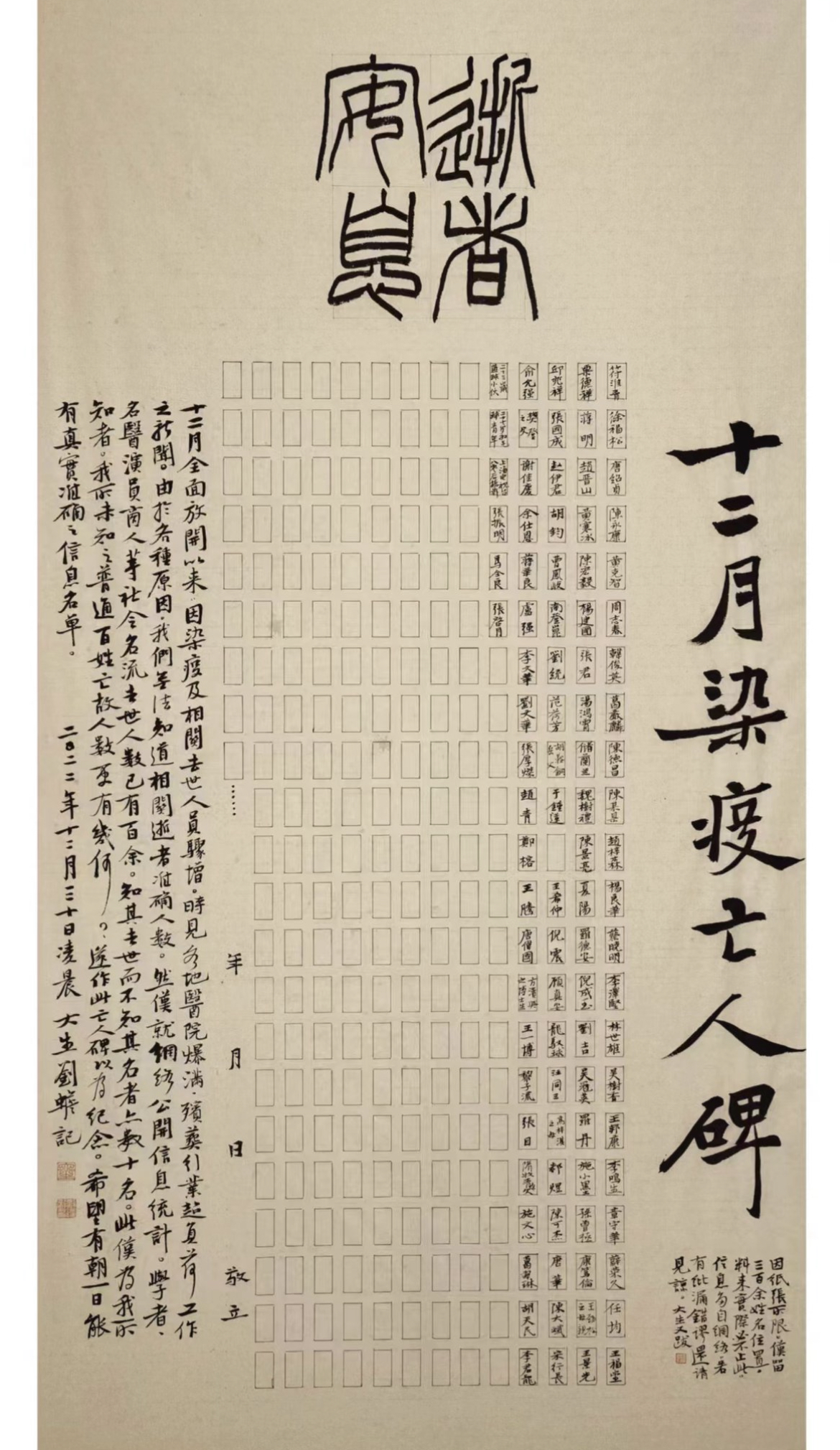

- Liu Chan’s Memorial for the Departed, 12 January 2023

- On Rumours & Lies — Dasheng’s Little Lectures, 16 January 2023

- Brainwashing vs. Educating — Dasheng’s Little Lectures, 17 January 2023

- Resisting Cultural Capture — Dasheng’s Little Lectures, 18 January 2023

- In the Eyes of the Beholder — Dasheng’s Little Lectures, 19 January 2023

- A Protection Mantra for the Year of the Rabbit, 22 January 2023

- Praise for the Orange Tree, Remembering the Plum, 8 February 2023

- High Peaks, Translucent Torrents, 24 February 2023

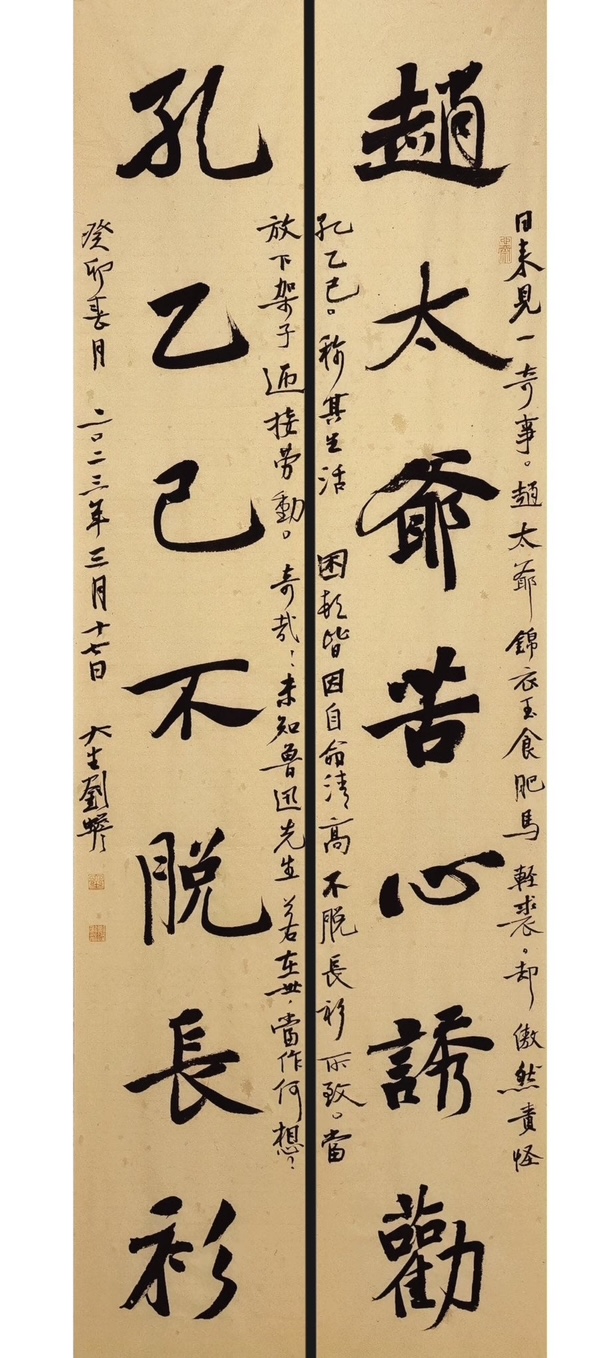

- Craven, Servile Knaves Hold Office, 7 March 2023

- Shades of Mao — Children Spying on Parents, Fragile Hearts in Patriotic Drag and the Fish Wife who Trolled Ukraine, 9 September 2023

- Liu Chan’s Calligraphic Comment on 7 October 2023, 8 October 2023

- Caged Birds and Turd Blossoms, 1 March 2024

Liu Chan’s work also features in:

- Xi Jinping’s Harvest — from reaping Garlic Chives to exploiting Huminerals, 6 January 2023; and,

- Xi Jinping’s Harvest — an anthem for China’s disaffected Huminerals, 7 January 2023.

***

Studiolo of the Heart

Editor’s Note: Dasheng 大生, also known as Liu Chan 刘蟾, is a writer and calligrapher who advocates for integrating Chinese traditional aesthetics with modern life. As chief editor of Chinese Study 中国书房, he emphasizes the importance of learning across civilizations rather than rigidly dividing East and West. Citing Wang Guowei 王国维, he argues that scholarship should focus on universal human concerns rather than cultural exclusivity.

Regarding traditional studies, Dasheng highlights the study 书房 as an intellectual and aesthetic concept rather than a physical space. He believes young people, even without a dedicated study, can embrace the literati spirit—valuing independent thought, critical engagement, and refined simplicity. Rather than recreating historical lifestyles, he encourages absorbing classical wisdom and applying it to contemporary life. He warns against extremes of either wholesale Westernization or cultural isolation, instead advocating a balanced, evolving tradition that dialogues with global modernity.

How can we harness the resources of China’s Confucian, Buddhist, and Daoist heritage, using creative transformation and innovative development to provide wisdom for people’s well-being, livelihoods, and social progress? On August 7, 2022, Phoenix Net hosted the “Salute to Guoxue: Fifth Global Huaren Guoxue Grand Ceremony” Wudang Summit Forum. Experts from the fields of Guoxue (Chinese classical studies), cultural communication, cultural tourism, and holistic wellness gathered to discuss how best to “revitalize” traditional Chinese health-related knowledge and strategies for connecting them to the market.

[Note: For more on Guoxue 國學, see Brian Moloughney, Sinology vs. the Disciplines, Then & Now, China Heritage, 24 September 2022.]

***

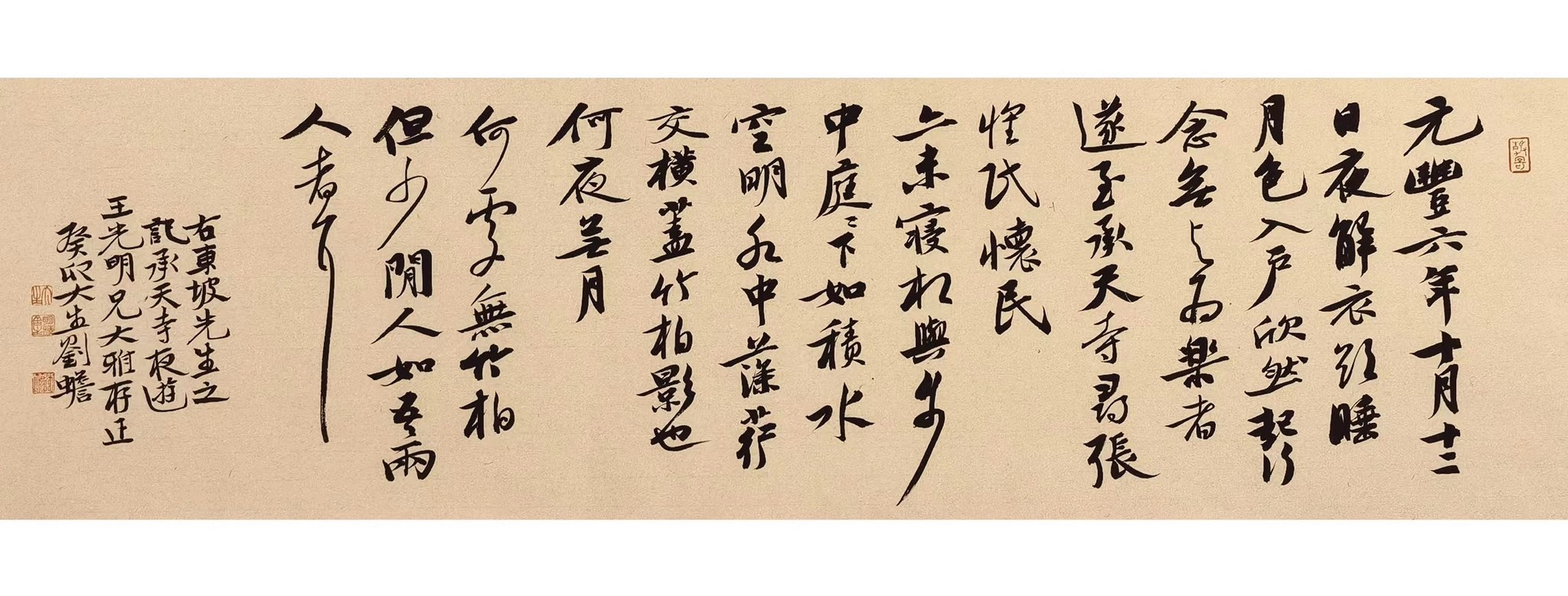

This calligraphic work in the hand of Liu Chan was written for Wang Guangming in the Guimao Year of the Rabbit (2023-2024). The text is ‘Walking at Night at Chengtian Temple’ 記承天寺夜遊 by Su Dongpo. See When Two Chinese Scholars Went for a Walk.

***

Liu Chan is editor-in-chief of Chinese Study 中国书房 and he is a member of the post-1980 generation of writers and calligraphers. For over a decade he has focused on the intersection of cultural tradition and aesthetic expression. In his view, Chinese traditional aesthetics crystallizes the ancient pursuit of both practical living and spiritual aspiration—within it lie abundant methods for self-cultivation. The real question is how to integrate these traditions into the present and engage younger people. In an interview with Phoenix Net, Dasheng noted that even a modest study can embody a cultural spirit—reflected in the owner’s aesthetic and cultural ideals—and that this spirit has much to offer today’s youth. At the same time, while inheriting traditional culture, he cautions modern Chinese not to overemphasize an East-West distinction, emphasizing the importance of mutual understanding among civilizations.

The following is an edited transcript of the interview.

Phoenix Net: The Huaren Guoxue Grand Ceremony, running since 2014 and now in its fifth edition, is dedicated to “saluting Guoxue, inheriting and innovating, learning from other civilizations, and reviving refinement.” [致敬国学,继承创新,文明互鉴,重建斯文] Of these phrases, which resonates most with you at the moment?

Dasheng: I’m most drawn to the phrase “learning from other civilizations.” [文明互鉴] Because the very term “Guoxue” carries a certain air of exclusivity. It emerged in modern times precisely in response to the influx of Western learning. Once we look deeper, however, we see that whether it’s Chinese or Western scholarship, they both address the same fundamental question: How can human beings live better, with greater dignity? The methodological core—focusing on facts, forming logical arguments—differs very little. The difference lies in research scope: Chinese scholars focus on China, while Western scholars look to the West, each with its own canonical texts.

Naturally, we acknowledge a great many differences shaped by regional factors and cultural customs. But deeper down, there are more shared elements than we might imagine. I particularly admire Wang Guowei 王国维 for saying, “In learning, there is no real difference between Chinese and Western, nor between ancient and modern—only between diligence and neglect.” [學無中西之別也,無古今之別也,唯有學與不學之別也。] The most vital principle in scholarship is to see how ideas interconnect, not just where they diverge. At times, it’s unhelpful to obsess over the East-West divide; we ought to focus more on commonalities.

Why do I say this? Because an overemphasis on the East-West split often leads to two possible outcomes: one is assuming Chinese culture is useless and thus adopting wholesale Westernization, which can be a disaster; the other is seeing no overlap at all between Chinese and Western civilization, insisting all things Western are alien and must be rejected, leaving us trapped in a rigid, conservative position with no alignment to modern civilization.

In today’s world—especially in a globalized context—neither extreme is appropriate. That’s why I highlight the elements in Chinese tradition that align with modernity and encourage dialogue between Eastern and Western cultures. Historically, what we label as “Chinese traditional culture” has constantly evolved, continually absorbing foreign influences from East, West, North, and South, ultimately creating what we now call tradition.

Phoenix Net: You serve as chief editor of Chinese Study 中国书房, and the idea of a study 书房 is deeply embedded in Chinese culture. But given the high cost of housing in many cities, owning a private study is becoming prohibitively expensive. Do you have any recommendations for addressing this tension?

Dasheng: Let me first clarify what we mean by “study.”

Researching the traditional Chinese study isn’t about recreating the classical literati lifestyle, where each person has a refined room filled with antique books and objects, indulging in brush and ink. Rather, our aim is to understand how ancient scholars lived, to grasp their aesthetic tastes, and then to distill the spirit of Chinese classical aesthetics—which differs significantly from Western aesthetics, possessing its own unique qualities. Unfortunately, we haven’t fully articulated these qualities yet. Early modern scholars wrote important works on aesthetics, but there’s still a need to move forward and build on that.

[Note: For more on the Chinese Study, see Zhai, the Scholar’s Studio, China Heritage Quarterly, no.13 (March 2008).]

***

[Note: See Liu Chan’s Memorial for the Departed, China Heritage, 12 January 2022.]

***

So, studying the old Chinese study is primarily about clarifying the literati aesthetic and then integrating it with the modern world to benefit our lives today. That’s the guiding principle behind our research into “Chinese Study.”

From there, let’s address the high housing costs. Many young people indeed can’t afford to set aside a special room as a study. This results from social factors beyond individuals’ control, and it’s not that young people are uninterested in reading. I trust that, in time, as things evolve, housing will become more reasonable, hopefully ensuring that everyone can have a roof over their head. Maybe then, if conditions permit, you can carve out a comfortable study space.

In practical terms, if you don’t have room for a dedicated study, you can still make do with a small corner or a few books. Even if you read in the bathroom, you can feel some pleasure. That corner becomes a little study of its own.

Studying is about exploring an ideal realm—absorbing the aesthetic and spiritual lessons of ancient scholars. So, even if we don’t have a large, physical study, we can still adopt the study’s ethos. That ethos might include taking responsibility, maintaining a critical eye, valuing independence, and the minimalist, straightforward aesthetic cherished by ancient literati. Whether or not you have the space for an elegant study room, these values remain ones we can learn from and uphold.

***

[Note: See Cindy Carter, Word(s) of the Week: “Kong Yiji Literature” (孔乙己文学, Kǒng Yǐjǐ Wénxué), China Digital Times, 29 March 2023.]

***

Source:

- 二哥專欄, Dasheng: There Is No True East-West Divide in Learning — A “Study” Spirit Is Possible Even Without a Dedicated Study, Chinese Calligraphy Review 中華書法評論, 3 March 2025, translated from 大生:學無中西之別 即使沒書房也可以有書房精神,鳳凰國學網,2022年9月2日. Minor stylistic changes have been made by China Heritage.

Chinese Text (in the original ‘crippled characters’ 殘體字)

大生:学无中西之别 即使没书房也可以有书房精神

凤凰国学

如何激活以儒释道为代表的中华传统文化资源,通过创造性转化和创新性发展,为当代普罗大众的身心健康、安身立命乃至社会发展提供智慧支持? 2022年8月7日,凤凰网主办的“致敬国学:第五届华人国学大典”武当高峰论坛上,来自国学研究、文化传播、文旅康养等领域的众多专家跨界对话,议题聚焦于中华传统养生智慧的“活化”问题与市场转化策略。

受邀参与本次论坛圆桌对话的《中国书房》主编大生,本名刘蟾,是“80后”青年作家和书法家,十余年来一直关注文化传统与审美表达的关联。在他看来,中国传统美学是古人对生活实践与精神追求的沉淀,其中蕴含着丰富的修身养性之道。如何跟现代进行共融,怎样让现在的年轻人更多地接手?大生在接受凤凰网专访时表示,一个小小的书房,自有其文化精神,其中寄寓了书房主人的审美选择与文化追求,值得今天的年轻人学习。当然,在继承传统文化的同时,大生也提醒,作为现代中国人,尤其应当注重文明互鉴,不宜过分强调中西之别。

以下是整理后的采访实录:

凤凰网:华人国学大典,从2014年办到今天已经第五届了,主旨是“致敬国学,继承创新,文明互鉴,重建斯文”。这几句话当中,你现在最看重的是哪一句?

大生:我最看重的是第三句:文明互鉴。因为“国学”这个概念本身就带着一定的“排他性”。这个概念产生于近代,是相对于西学东来的背景而有的。实际上,我们在深入研究以后会发现,不管是中学还是西学,其实都是关注人的问题,都是在关注怎么样让人能够生活得更美好、更加有尊严。包括双方所用的方法,其实也大同小异,都要实事求是、推理论证。区别只是你研究的范围是中国领域,他研究的范围是西方领域。不同的范围,研究的经典对象不一样。

当然,我们要承认双方有很多不同,这是地域性以及文化习俗决定的。但是,我们要看到它背后其实有更多相同的东西。我特别推崇王国维先生一句话,就是“学无中西之别也,无古今之别也,唯有学与不学之别也。”做学问最关键的,应该是有一种“互通”的感觉,不仅要看到不同,还要看到其相同的地方。某些时候,也不要刻意的、过分的强调“中西之别”,我们更应该看到它们之间互通的一些地方。

我为什么这么说呢?其中一个原因是:如果我们一直过分强调中西之别,带来的结果往往就有两种:一种是认为中国传统文化都不行,要全面推倒中国传统文化,全面西化,这个可能就是一种灾难;另外一种,是认为中国传统文化跟西方完全不一样,你们西方所有的东西对我们来讲都是外来的,都应该排斥,也就会导致我们一直走一种顽固、保守的状态,不能和现代文明进行很好的对接。

我觉得这两种状态在今天的语境下,在全球化背景来看,都不太合适。所以,今天我更加会强调传统文化当中和现代文明相通融的那些因素,更加强调东西方文明的对话和交融。实际在历史上,我们也知道,中国现在所谓的“传统文化”,也是不断变化的,也是历朝历代不断吸纳外国文化,吸纳西方、东方、北方、南方,吸纳融合各地文化而最终形成的结果。

凤凰网:您是《中国书房》的主编,书房在中国文化当中其实也是一个很好的承载物。但是现在城市的房价很高,导致我们想要一个书房的成本很大,这个矛盾您有什么好的建议吗?

大生:我首先想对书房这个概念稍微做一个阐释。

我们今天研究书房,并不是说要像古代文人士大夫一样,每个人都要搞一间很雅的屋子,摆上一些古籍、古玩,在那儿玩一玩笔墨纸砚。我们今天研究书房的一个主要目的,是要了解古人的生活方式,了解中国古代的文人审美趣味,把我们中国古人审美的特点和精神总结出来——因为中国的古典审美确实和西方审美有很大的不同,并且有它独到的地方,但是非常可惜,我们还没有很好的一个阐释和总结。近代以来有几位前辈做的非常好,写了很多关于美学的著作。但是我们依旧需要再往前走一步。

所以说,做古代的书房研究更主要的,是想把古代文人审美给搞明白、搞清楚,然后再把这个东西和现代进行结合,以便服务今人,让我们今天的生活变得更加美好。

这是我们做中国书房研究的一个初心和初衷。

基于这个初衷,再来回应您刚才这个问题。我觉得现,在的房价确实非常高,很多年轻人可能没有拥有书房的条件,这是一定的社会原因造成的,也不能怪年轻人,也不能怪大家不读书。我相信随着时代的变化,随着时间的推移,房价也会趋于稍微理性,应该保证人人都能有房子住。这大概还是可期的。到时候,可以根据条件,布置一个舒适的书房环境。

在现实中,如果没有专门的书房空间——哪怕有一个小的角落,有几本书,这个空间也可以成为简易书房。像我们刚去北京的时候,住得非常简陋,但是随便一个角落,放几本书,哪怕在上厕所的时候看会书,也会觉得很享受,这就是自己的临时小书房。

研究书房这一块,主要还是学习理想中的、古人的审美和精神。所以,即便不具备宽敞的、具象的书房,我们依旧可以学习古人的书房精神。比如敢于担当、敢于批判、独立自主的古代士人精神,以及化繁为简、大方素雅的审美选择等等……我觉得无论是否有条件拥有一个漂亮的书房,这种精神都是我们可以学习和继承的。

***

Source:

- 大生:学无中西之别 即使没书房也可以有书房精神,凤凰国学网,2022年9月2日.