Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium

Chapter XXII (supplement)

抱薪者

Below we feature an interview that Li Yuan 袁莉 conducted with Li Ying 李穎, ‘Teacher Li’ 李老師不是你老師, on the first anniversary of the November 2022 protests in China. Those protests are known as the White Page Protests, however, as Teacher Li points out, the year 2022 witnessed protests in cities throughout China not only related to the harsh Zero-Covid policies of Beijing but also focussed on a range of other social issues.

***

Li Yuan hosts Who Gets It — Searching for the Truth and Answers Together 不明白播客:一起探尋真理與答案, a Chinese-language podcast that features conversations with newsworthy individuals from all walks of life. Yuan is also the Asian tech reporter for The New York Times.

As Li Yuan wrote in a column about her conversation with Teacher Li:

Mr. Li is among a generation of young Chinese activists who stood up to their government and Mr. Xi out of a sense of justice and dignity. They are not professional revolutionaries but accidental activists who felt compelled to speak out when Mr. Xi was turning their country into a giant jail and their future into a black hole.

— ‘I Have No Future’: China’s Rebel Influencer Is Still Paying a Price, The New York Times, 12 December 2023

With Li Yuan’s kind permission, we offer an edited translation of her conversation with Teacher Li. It is included in Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium as a supplementary section to Fear, Fury & Protest — three years of viral alarm.

‘It’s only the end of the beginning — Teacher Li on Blank Pages, Li Keqiang, Snowflakes & Monsters’ should be read in conjunction with:

- Awakenings — a Voice from Young China on the Duty to Rebel, 14 November 2022;

- How to Read a Blank Sheet of Paper, 30 November 2022;

- It’s My Duty, 1 December 2022;

- ‘Ironic Points of Light’ — acts of redemption on the blank pages of history, 4 December 2022;

- A Ray of Light, A Glimmer of Hope — Li Yuan talks to Jeremy Goldkorn & to a Shanghai protester, 10 December 2022;

- When Zig Turns Into Zag the Joke is on Everyone, 12 December 2022;

- From the White Paper Protest to a White Wall in London, 20 August 2023; and,

- What Scares Me — a letter from Kathy on the first anniversary of the White Page Movement, 4 December 2023.

Taken together, this material offers an overview of the protests in China, as well as some of the international reactions to them, in late 2022.

***

***

We also recommend Teacher Li’s Chinese-language YouTube channel, in particular his discussion of politics-induced depression, his interview with an official internet content moderator and his reflections on the White Page Protests. See:

- 聊聊「政治性抑鬱」,以及我對抗政治性抑鬱的經歷, 11 September 2023

- 對話網絡審核員:一邊審核別人,一邊覺醒自己, 9 October 2023; and,

- 我的白紙運動:一週年, 25 November 2023.

And, of course, we also recommend Teacher Li’s X/ Twitter account:

(The name of Li Ying’s Twitter account — ‘whyyoutouzhele‘ — is a tongue-in-cheek reference to Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Zhao Lijian’s comments in late December 2021 that foreign journalists should ‘be secretly happy’ 偷著樂 tōuzhelè for being able to live safely in China during the COVID-19 pandemic.)

***

抱薪者 bàoxīnzhě, the Chinese rubric for this supplement to Chapter Twenty-two, means ‘a person who carries firewood’. It comes from Murong Xuecun’s observation, quoted in the conversation below, that ‘You can’t let the person carrying the firewood freeze to death in the wind and snow’ 為眾人抱薪者,不可使其凍斃於風雪 (for details, see Li Yuan, Widespread Outcry in China Over Death of Coronavirus Doctor, The New York Times, 7 February 2020).

Section headings, illustrations and notes have been added to this edited translation by China Heritage. I am grateful to Reader #1 for pointing our various typographical infelicities in the text and to UglySpoon 丑勺子 for suggesting ‘Teacher Li is not teacher of thee’ for Li Ying’s handle, 李老師不是你老師. Herein, however, we use ‘Teacher Li’ as a shorthand for the somewhat Taoist-inflected meaning behind the words, to wit: ‘The teacher who is no teacher is truly a teacher’.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

18 December 2023

First day of the show trial of

Jimmy Lai in Hong Kong

***

Updates:

- On 1 January 2024, Teacher Li launched ‘Snowflake Daily News’ 雪花每日新聞 on his YouTube channel.

- On 26 February 2024, Teacher Li issued an urgent alert via X/ Twitter advising readers that some of his followers in China had been ‘invited to tea’ 被喝茶 by the police for questioning. Within hours, large numbers of people had unfollowed 取關 his account. Other independent Chinese commentators reported a similar mass ‘shedding of fans’ 掉粉; and,

- For an update of Teacher Li’s circumstances, see

- The Persecution of Teacher Li, 16 May 2024.

— Ed.

***

Related Material:

- David Bandurski, Policing Pessimism, and Everything Else, China Media Project, 14 December 2023

- The Right to Know & the Need to Lampoon, 18 October 2021

- Zeyi Yang, How Twitter’s “Teacher Li” became the central hub of China protest information, MIT Technology Review, 2 December 2022

- 江雪,因「白紙抗議」的報道被質疑「倫理」,一個記者的回應

- 江雪,鮮花與詩流落何方?這一年,被抓捕的年輕人還好嗎? | 歪脑 WHYNOT

- 五岳散人,「白紙運動」一週年:把這個超級符號延續下去,接班六四敘事、成就新一代人的價值訴求

- One Year After the “White Paper” Protests: Reassessing China’s Politics and Society, Asia Society, 18 December 2023

For a while, Li’s Twitter bio featured a line that seems to belong to a world of epic tales. “Look at the giant tower which stands tall and reaches the heavens. Every moment, someone jumps from it. When I was little, I didn’t understand, and thought they were flakes of snow.” Li said he used to be a xiaofenhong, or “little pink,” referring to overtly nationalistic young people. “In this phase, when I see things that were unreasonable, or bad, I would have said, for the country to progress, we could sacrifice the welfare of this small group of people,” Li explained, “now I realize that these sacrifices were people’s lives.” With this insight, he said the falling snow from a grand tower became something else.

— Han Zhang, The Twitter User Taking on the Chinese Government, The Nation, 6 December 2022

***

***

The End was Just the Beginning of Something

李老師:白紙運動是開始,不是結束

Teacher Li in conversation with Li Yuan

袁莉對話李老是不是你老師

An edited and annotated translation by Geremie R. Barmé

[For the Chinese text of Li Yuan’s conversation with Teacher Li, click here. — Ed.]

Over a year ago, on the eve of the White Page Protests of November 2022, Li Ying (李穎, 1992-) was just another Chinese student studying in Italy. Like so many other young people, confronted by China’s political scene he felt something akin to impotent befuddlement. When would the harsh Zero-Covid policies be changed, when would he be able to go back to China and, more broadly speaking, where was China headed?

Amidst the White Page Protests, the worker unrest at Foxconn and widespread civil unrest, ‘Teacher Li’, as he called himself, and his Twitter account — ‘Teacher Li is Not Your Teacher’ — became a major international clearing house cum news hub for the dissemination of unofficial on-the-ground reports of what was happening in China.

Today, as we commemorate the White Page Protests of a year ago, I’ve invited Teacher Li to reflect on his experiences and discuss what he thinks might be unfolding. Among other things, I’m interested in the price he has had to pay for becoming, albeit unwittingly, a spokesperson for the present age; the sacrifices he’s made; the symbolic significance of ‘snowflakes’; his view of ‘love’; how he negotiates the conundrum summed up by Nietzsche as: ‘He who fights with monsters might take care lest he thereby become a monster.’ I also ask him how he feels about being crowned China’s ‘leading rebel’ and, most important of all, why he believes that the White Page Protests were not an end in themselves, but rather just the beginning.

— Li Yuan 袁莉

- 李老师:白紙運動是開始,不是結束, 不明白播客,EP-074,2023年11月25日

***

Li Yuan: Teacher Li, can you tell us what your life was like on the eve of the White Page Protests in China in November 2022?

Teacher Li: A year ago, just a little before the White Page Movement broke out, I had only recently graduated as an overseas Chinese student [in Milan, Italy]. Like most people at such a juncture, I was feeling a little lost and not sure whether I should go back to China or try to find some work here.

When I was studying I’d had a part-time job advising other Chinese students [who, like me, were studying art] on how they should go about compiling a portfolio of their work and even some things related to my own métier of painting. Since I was in Milan, I started getting involved in a few things and, in the process I became interested in Twitter. That was in April, around the time the authorities deleted my WeChat accounts and that was sort of how I ended up on Twitter. At first, people in China started asking me to post things on their behalf. At first, I was just helping out.

Then all of a sudden — I guess it must have been around October [2022] — right after Peng Zaizhou’s protest at the Sitongqiao Overpass [in Beijing], I reached something of a crossroads. Why, you might ask. Well, you see, I was hesitating about returning to China, mostly due to this lingering apprehension — because from 2019 and throughout the pandemic, I’d been completely uncertain about when it might all really be over. During the summer of 2021, since most people here in Europe had been vaccinated things pretty much returned to normal and people were moving around freely again. Meanwhile, back in China, things were increasingly tightening up. The contrast couldn’t be more obvious; I also felt it because my life was pretty much back on track. Going online you could see what was happening and from my family I also knew that the restrictions there were particularly harsh.

In 2022, the Omicron variant struck and when Shanghai was put on lock down [from February to August], I was feeling quite down about the future. The severity of the controls came as a real shock, as were the videos of Big Whites in Hazmat suits kicking in doors and dragging people away. It really was spooky; I definitely didn’t want to go back to that. Then again, my dad and mum were in China, so I was really conflicted. Should I wait until the pandemic was over before making a decision? But there was no indication that it would come to an end and that really hit hard. Were people simply going to put up with that crazy state of affairs without a peep? Then, suddenly, Peng Zaizhou launched his protest [in Beijing on 13 October against Xi Jinping and ongoing Covid restrictions] and that really had an impact on me. I realised that at least there was someone who was willing to speak out on behalf of everyone else. Someone whose protest was a call to others that encouraged them to overturn the harsh Covid policies. He was such an inspiration that I started reposting things about people resisting the zero-Covid policies on Kuaishou and TikTok. I knew lots of people were getting over the China’s Great Firewall and I wanted to share what I knew about the opposition that was happening in China with them, too. Then, when the White Page Movement broke out [in late November], everything changed for me.

***

***

Li Yuan: And so that’s how you ended up becoming the most important clearing house for unofficial information and news in the Chinese world?

Teacher Li: At that moment, yes. It’s no longer the case now.

Li Yuan: I think it still holds true even today. For me, personally, there are two new sources that I feel I have to check every day: one is the People’s Daily and the other is your Twitter/X account.

Teacher Li: Sure, I still post lots of things but new social media accounts are appearing all the time, which is great. I’ll admit that my account still has something of a role to play since I can report on breaking news with considerable speed. Take the death of Li Keqiang [on 27 October 2023]: I was able to follow events as they unfolded. I also report more general news, though my efforts aren’t really on the same level as the professional news outlets.

Yuan Li: You’re far too unassuming. After all, professional news hounds like me follow what you’re posting. (Teacher Li: Now you’re embarrassing me.) But can you give me some sense of the difference in quality and quantity of the tips and news that you’re being sent today compared to this time last year?

Teacher Li: Actually, it’s pretty significant. Before the White Page Movement, most of the things people sent me were, say, things like: we’re being taken away; they’re locking down our city; I’ve been placed in isolation and the conditions are terrible. Then there were all the posts I got reporting that people didn’t have enough to eat or drink, or that they were suffering from the cold … Then, exactly a year ago, suddenly all the posts I received were about people breaking out in protest all over the place. It was a massive change.

Yuan Li: No doubt a lot of things have happened over the last year, just as your personal circumstances are different. An online contact who’d asked you to post things for them and had been questioned by the police told me that: “Within the Great Firewall, Teacher Li is without doubt the most iconic renegade. They [the authorities] react to every tweet he posts as though it’s a major threat and they issue orders from on high down to every level of police control.” How do you feel about having the status of ‘Renegade in Chief’? Or, rather, how do think of yourself and your Twitter account?

Teacher Li: Yeah, I’ve heard that before. All levels of the security apparatus have their eye on my account, including people at the Cyberspace Administration. It’s my understating that whenever I post about a major story or event they issue a directive to the relevant censors to launch an investigation and ban any mention of it appearing on Chinese internet sites. (Li Yuan: How do you know that?) Because in the past, I interviewed one of the censors myself.

Li Yuan: Oh, that’s right, I listened to that interview.

[Note: For this interview, see: 對話網絡審核員:一邊審核別人,一邊覺醒自己, YouTube, 9 October 2023.]

Teacher Li: So, that ‘net invigilator’, or censor, told me about it herself. Then there’s the kind of things the local police would deal with, coming from the provincial level, or even higher up — instructions that were issued about how to handle a certain piece of information or story.

[Note: For more on this subject, see Directives from the Ministry of Truth as well as 404檔案館, both published by China Digital Times.]

Take the death of Premier Li Keqiang, for example, and the stories about how the police questioned people who had offered floral tributes [at his former homes]. That’s why I stopped posting stories about floral tributes [out of a concern that the police would use those reports to identify sources]. It’s bizarre that the authorities made such a big deal out of people wanting to commemorate their own premier.

[Note: See Monster Mash — Mourning a Dead Premier & Mocking the Ghouls Among the Living, 4 November 2023; and, Li Keqiang, the ‘Empty Boat’ of the Xi Jinping Era, 14 November 2023.]

How do I see my reputation as China’s ‘Renegade-in-Chief’? Well, in the first place, I’d say that’s hyperbole. I see my role in pretty simple terms: I’m helping people broadcast news about what’s happening on the ground in China, helping get word about what people have seen or experienced out into the world. It’s not as though I’m inciting people to do anything, or calling on everyone to take action at some point somewhere next month or anything like that.

And, as for how I see my Twitter account: it’s just a news source.

Of course, lots of people place a lot of faith in me, they hope that since everyone is following my posts, they hope that I’ll do something, or lead everyone in some way. But that’s not who I am, though I might be interested if I was actually in China. I’m not there, so what right do I have to instigate people who are? So, like I said, I’m a news source. Moreover, I really don’t think people should expect me to be responsible for speaking out. In my opinion, everyone should do what they feel is right for them. It’s not just up to me.

Yuan Li: Since you think of yourself as a news source, can you say a few words about how you decide what information you’re going to post?

Teacher Li: I have what you could call a ‘double standard’. If it’s an unfolding story — like the White Page protests, Li Keqiang’s death, or the Beijing floods [in August 2023] I’ll focus on posting accurate information in a timely fashion. Of course, I need to be certain that the event is actually taking place, something that is pretty easy to work out. In the case of a specific incident, like Li Keqiang’s death, for example, you can just reproduce things pretty automatically and be aware that people are making out that it’s like Hu Yaobang’s death [in April 1989 which sparked nationwide protests and the Tiananmen Incident on 4 June]. Same for the White Page Movement, when people used material about the Russian police ramming protesters with their vehicles and falsely claimed that it was the Chinese police. Or when people post things about mass protests and claim they are from China. There’s lots of things like that so, when it’s a breaking story, I’m more vigilant than usual.

In normal circumstances I’m a bit more relaxed and so mistakes are unavoidable. Why? Because I probably think that a particular erroneous post is not all that important, or that it is about something that I pretty much feel that the authorities might really do, so I go with it. My guiding principle is that I trust my netizen informants [網友] and I post their material accordingly.

Li Yuan: What do you do when you discover something’s false?

Teacher Li: If it’s wrong I simply delete it.

Li Yuan: During the recent commemorations for Li Keqiang how many reports would you get in, say, a day?

Teacher Li: It reminded me of the White Page Movement since I was getting something in every few seconds. Though, having said that, it wasn’t as frenetic as the White Page. Like, on 27 November [2022], I was basically getting about a dozen to twenty posts every second. On 2 November [2023, when Li Keqiang was cremated], I received over 300 emails.

Li Yuan: All about Li Keqiang?

Teacher Li: That’s right. People mourned him in various ways. Some wrote personalised notes to him, others just wanted to offer flowers. Then there were the people in Beijing who went out to the Babaoshan Crematorium and Cemetery. On 2 November I had some things to attend to and only had access to my phone. There were so many messages coming in I simply couldn’t handle them all.

Li Yuan: Anyway, you posted lots of them. You’ve always said that you’d been swept up by events and that, before you knew it, you’d become an international clearing house and media centre for China as a whole. Given that you are in fact confronting a vast repressive state apparatus aren’t you just a little bit afraid?

Teacher Li: Of course. At first I was terrified.

Li Yuan: When you say ‘at first’, do you mean during the White Page Protests?

Teacher Li: Yeah, more or less. From the evening of the 27th [of November 2022].

Li Yuan: The night of the protests in Shanghai.

Teacher Li: No, the protests at Liangmahe in Beijing [when protesters called for Xi Jinping to resign.]

Li Yuan: That was the following day, then.

Teacher Li: That’s right, the second day. Liangmahe was the largest protest in China. After I’d posted news about it, or even during it, I received numerous threats, private messages saying things like: ‘I’m gonna kill you’, or ‘Another peep out of you and you’re dead’. I had no idea if they were from some Little Pinkoid zealot or someone else. I felt pretty scared. Actually, I was so freaked out that I posted a few things saying you’d better not try it … then, after a while, gradually, well, I just got over it and ignored them. I reckoned there wasn’t really anything to be afraid of.

After the White Page Movement [when the Zero-Covid restrictions were suddenly lifted] and Chinese students studying overseas like me could go back, and when urban dwellers in China were finally free from all of the limitations that had been placed on movement — that’s to say, when life returned to normal, and you could eat out, go to the movies, go shopping, travel — I began to feel that I really had sacrificed my life. But that was okay. Even if I could never see my family again, or if I simply vanished, that was cool, too. That’s because I felt that I had done something meaningful, something for myself.

Li Yuan: Sure, I get it. And, may I ask, you’re thirty-one, right? Teacher Li: That’s right. Born in 1992. Li Yuan: Okay: That makes you 31. You live in Milan, Italy and how many cats do you have? Teacher Li: Two.

Li Yuan: So, it’s just you and the cats. Do you socialise much?

Teacher Li: On and off, not that much.

Li Yuan: You’re pretty much a homebody, then?

***

***

Teacher Li: More or less. During the mourning for Li Keqiang, for example, I didn’t go out for days on end, not even to the supermarket. I lived on McDonald’s.

Li Yuan: Sounds pretty much like my own lifestyle. Sometimes I really have to force myself to go out for a run, or do things like that. Another question: do you think you’ll stick with what you’re doing, ‘decentering’ information like you do? Though, in saying that I’m aware that you’re regarded as the ‘ultimate centre’ [for the dissemination of non-official information]. You’ve responded to that claim by saying that: ‘Of course, in a sense, I am a centre, but you must be careful not to listen to my voice alone.’ What do you think the long-term significance of your Twitter account is? Do you want to use it to do more?

Teacher Li: I didn’t set out to be a ‘centre’ of any kind. In any healthy society, there are all kinds of media outlets and opportunities for people to express themselves freely. Instead, [in the case of China] you now only have me. Though similar accounts like mine have been appearing, too, which is great.

In China people are subjected to extreme censorship, but the Chinese authorities can’t delete my tweets, despite all the times that they’ve reported me and the content of my posts. It’s ironical that if Chinese people want to known what’s happening in China they have to clamber over the firewall and look at my Twitter account. I really felt as though … from one angle it’s a tragic situation, though from another perspective it’s extremely fortunate that at least people have some place like this, one where they can get an idea of what’s happening around them and in their own country.

I hope my account can continue to broadcast the voices of Chinese people that reflect what’s really going on. If you follow Twitter you might, over time, see some major changes in China from one year to the next. Accounts like mine help people follow what’s going on, what’s changing, and you get a sense of hope from that.

[Note: Here Teacher Li is commenting on the issue of ‘the right to know’, 知情權 zhī qíng quán in Chinese. Although the Communists claimed monopoly control over news and information from 1949, since Mao’s death in 1986, people from all walks of life have struggled to gain access to reliable information about the society in which they live. At times, their efforts have even been aided and abetted by China’s version of ‘the deep state’. For more on this topic, see The Right to Know & the Need to Lampoon, 18 October 2021.]

Li Yuan: Let’s now talk about the changes happening to the Chinese themselves. In a video that you posted on YouTube in July this year you said:

‘Despite the strict censorship in China, there are signs that it is faltering. … What’s more important than some ‘dynastic change’ is the fact that Chinese citizens are experiencing an awakening.’

It’s been over a year since Peng Lifa’s protest at the Sitongqiao Overpass in Beijing and nearly exactly a year since the White Page protests. What, from your observations, has happened in China that makes you say this and what direction do things seem to be moving in?

Teacher Li: The most obvious change that I’ve observed is that people are increasingly taking their protests into the streets. At first, during the Covid years, most people trusted the government to take care of them. But now lots of people are going into the streets. Take the protests over medical insurance reform in Wuhan [in February 2023], for example, led by senior citizens; or the outrage over unfinished apartments and ‘rotten tail’ building projects [that left home buyers and investors in real estate alike in the lurch]. Then there’s the seniors in middle school all over the country who are starting to demand that their holidays be protected.

My sense is that in the wake of the White Page Movement, people began to realise that they could fight for their rights and that individuals should demand to have their needs addressed. To my mind, that’s a significant change.

Similar things are happening in regard to censorship. During the White Page protests we didn’t see that many examples of people directly challenging the authorities [衝塔 chōngtǎ] but, a year later, during the mourning for Li Keqiang, if you looked at TikTok late at night you’d see all these shorts in which people were cursing him [that is, Xi Jinping] and hoping he dies. It goes to show that people do want him gone.

Yuan Li: It’s summed up in that expression ‘Unfortunately Not You’ [the title of a popular song], isn’t that so?

Teacher Li: Absolutely. ‘Unfortunately not you’! ‘We need to keep healthy so we can outlive him’. Things like that were constantly popping up. It was a quantum leap. That’s why I have the sense that society, or the overall environment, including the economic downturn, and the kinds of pressures people are feeling in their everyday lives …. In the process, unbeknownst to everyone, people are simply becoming more daring.

But they are also increasingly cunning. Why do I say that their system of censorship is unravelling, because, say in the case of the name ‘Xi Jinping’, which is a taboo word, people completely avoid it and just speak about ‘The Steamed Bun’ 包子, or ‘Winnie’ 維尼. Of course, they can ban those words online, but what do you do about things like ‘[Shaanxi-style] Meat-filled Bun’ 肉夾饃 or ‘The Shaanxi Man’ 陝西人? You can’t outlaw such common expressions. You’ll run out of words.

Li Yuan: And there’s ‘A certain fellow from Beijing’ 北京某男子.

Teacher Li: Exactly! There’s no way you can shut it all down. Sure, an expression like ‘A certain fellow from Beijing’ can be censored, but what about ‘Meat-filled Bun’. It’s a common food. Or ‘The Shaanxi Man’? It’s like ‘Teacher Li’ 李老師: a name that you can’t ban since China has countless teachers with the surname of Li. Why do I say that they are losing their effectiveness? It’s because when something happens that people want to discuss, the sheer onslaught of the collective wit and the lightning speed of ordinary Netizens are able to outmanoeuvre the censors.

[Note: David Bandurski deftly discusses the absurd lengths to which China’s online content moderators have to go in pursuit of ‘the impossible art of censorship’. He notes that, as part of the ‘clear and bright action plan’ 清朗行動 to sculpt online content in 2023, the Cyberspace Administration of China outlined ‘three broad types of content, including “fake information” (虚假信息), “misconduct” (不当行为), and “incorrect concepts” (错误观念).’ ‘…[W]hile some of the language points vaguely to instances of misbehavior that could have real implications for the public, much of it looks like regulatory compulsion from a system that simply cannot stop clarifying itself — to the point that nothing is clear.’

Bandurski sums up the walking the tightrope of internet invigilation in the following way:

‘Go hard. But not too hard. Cut this, but not that. Back off, but wait — not so much. Squeeze tighter, but do not strangle. Are we clear?’

See David Bandurski, Policing Pessimism, and Everything Else, China Media Project, 14 December 2023.]

Li Yuan: Despite that, in my discussions with friends in China, people formerly known as the ‘liberal intelligentsia’, there’s a general mood of hopelessness. One contact who works in the media told me:

‘The sense I get from journalist friends, as well as my own experiences, tell me that since the White Page Movement, or from when the Zero-Covid policy was abandoned, things in the media have actually gotten worse.’ And among normal people there doesn’t seem to be a shared view of things. The widespread outrage over the harsh Covid policies ignited a rare spirit of communal agreement. But the consensus has faded and everyone is focused on how they can “simply get by” [苟 gǒu] — that is, “survive one way or another” [gǒu huó苟活]. My impression is that the mood is of despondency.’

What are your observations?

Teacher Li: Personally, I don’t feel downcast at all, quite the opposite in fact. I’m positively optimistic. That’s because although many other people are holding out hope for some event that will change everything. I don’t believe that’s possible.

I still think you have to understand China in the context of its particular national characteristics [國情 guó qíng, a combination of history, politics, society, economic arrangements, regionalism, etc]. If you’re Chinese, or if you’re living in China, you know the temper of the place. Things only happen slowly; people only change over time, when they become aware or ‘wake up’. That’s to say, things will change as people become aware of their social role and individual rights as citizens. Things will only change gradually. Some dramatic event is not going to turn things on their heads. And, even if something like that did happen, if the majority of everyday Chinese were not in that mental and emotional space, though they were granted democracy, it would be useless because it would soon be subverted by some political opportunist. It’s likely that you’d then end up with another emperor.

The key to democracy is participation. If you put stock in everyone hoping for a change despite the fact that nobody wants to make a personal effort to change the status quo, it’s inevitable that, time and again, you’ll just see a reversal to type. At the time of the White Page Movement I said that similar unpredictable events were inevitable; they’re a response government repression. Why did the White Page Movement erupt? It happened in the wake of the apartment fire in Ürümqi [when people died locked in their apartments] and as a result of the government trying to repress the news about it. In the case of Li Keqiang’s death, they responded a bit better and gave people some space to publicly mourn. Even then, they were determined not to let things get out of hand and turn into an anti-government protest [冲塔]. At first, there was a widespread desire to mourn the dead premier, but attempts by the authorities to corral that sentiment led to much larger commemorations. When you tried to tamp it down, people started saying ‘Unfortunately not you!’

That’s why I reckon similar unexpected eruptions are likely and there will be moments of consensus, shared feeling as well. But when will something happen that could lead to the kind of consequential change that many people imagine leading to democracy, or greater freedom and openness? I can’t say. I feel every single Chinese person has to ask themselves: if you want a better society what are you prepared to do to bring it about? It’s a question every individual has to confront. Change is not going to come about as the result of some dramatic transient event of the kind that everyone seems to be hoping for, something that would overthrow the party-state and transform China. It’s simply not the way things work.

Li Yuan: I believe you’re the one who said that many people who were not rebellious previously are now willing to challenge the authorities [by posting negative messages]. How did you arrive at such a conclusion? Is it just what you’ve been observing about the general drift of things? I’m interested because I’m often asked about all of this and because the overall atmosphere in China is oppressive and people seem to be keeping their heads down hoping to survive as best they can. Yet, despite that, increasingly large numbers of people seem to be using VPNs to straddle the firewall and go online overseas added to evident signs of disaffection. Frankly, I’m not sure how to respond to the questions I get, or if perhaps there’s a better answer than the one I usually come up with. What about you?

Teacher Li: I am, of course, of the view that increasing numbers of people are trying to access information beyond the Great Firewall and find out more about what’s actually going on in China. You can judge it for yourself by the numbers of people following me on Twitter. Right after the White Page Movement I had around 70 to 80 thousand followers. It’s double that now: around 1.40 million.

[Note: In his conversation with Zeyi Yang, published in December 2022, Teacher Li said:

‘Before I reported on the Foxconn incident, I had about 140,000 followers, and then it got to 190,000 when I finished reporting on Foxconn. I lost count of how many followers I have now. Editor’s note: At the time of our interview, Li had over 670,000 followers on Twitter; by the time it was published, the number had increased to over 784,000.]

There’s no doubt that more people are interested in China and it’s the same in the case of Chinese who want to get a better idea of what’s happening around them. However, with China, the numbers of people you’re dealing with are astronomical. When the White Page protests broke out I had no idea people in universities all over China would participate. But they did and in considerable numbers.

[Note: See, for example, China Dissent Monitor, 2023 Issue 2: October-December 2022 and for a statistical breakdown of protests by time, province, type and frequency, see here.]

It reflects the way I’ve generally looked at China, call it a personal tradition if you will. Generally, most Chinese will keep their opinions to themselves. As a kid I myself was always regarded as being well-behaved. Consider what happened thirty years ago, in 1989, lots of people actually do remember, but they won’t make a peep about it. They might have sympathy for what happened, but they wouldn’t discuss their views openly, they’ll keep them private.

Or, take the case of Li Keqiang’s death. People didn’t go to the commemorations [outside his old home] so they could chant slogans, but they were thinking them. It’s not true that the Chinese are indifferent when it comes to politics. Go into a small eatery in any alleyway or that you might come across in any street in the country and you’ll find tucked away in all of those private rooms people discussing the politics of the day. Since they’re not doing so in public you have no idea how many people are actually politically engaged.

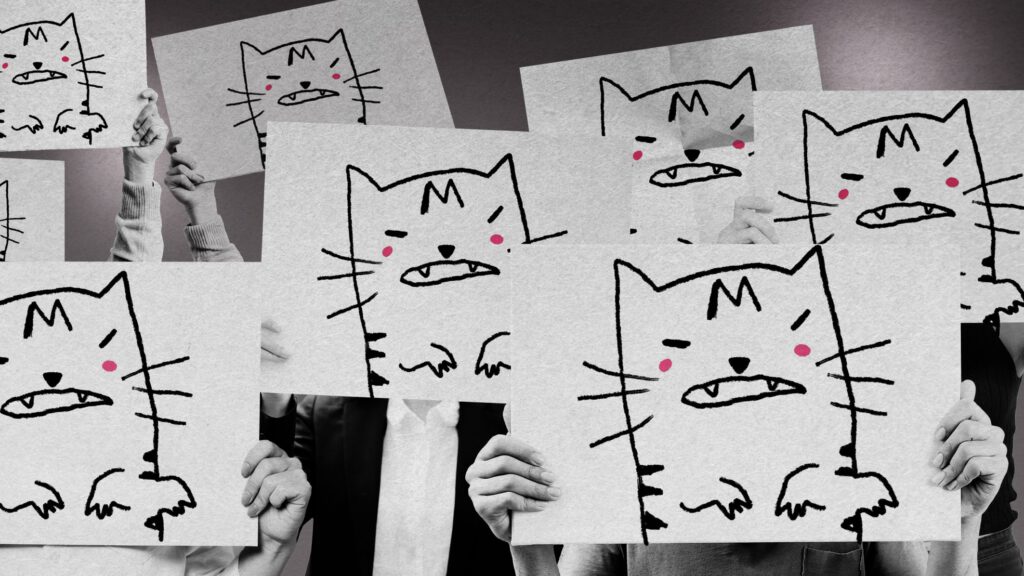

Of course, the repressive atmosphere at the moment is the result of strict censorship and social control. People know all too well not to speak out of turn; they know that if they do, they’ll have to pay a heavy price. If you raised a banner with the cat avatar from my Twitter account on it in China today, or if you spoke up, you’d be taken in. So, people keep their opinions to themselves, so much so that, superficially at least, everything is dead and no one is saying anything. But that’s only on the surface.

***

***

Snowflakes

Li Yuan: Can we talk about ‘snowflakes’? The pinned message on your Twitter account reads:

‘Look at the giant tower which stands tall and reaches the heavens. Every moment, someone jumps from it. When I was little, I didn’t understand, and thought they were flakes of snow.’

That was posted on 16 April 2022, around the time that you really got into using Twitter. Subsequently, you’ve frequently used the term ‘snowflake’ in a symbolic sense, like you did in a tweet dated 20 November 2022, just before the White Page protests erupted and while conditions under the Zero-Covid lockdowns were still pretty harsh. You wrote:

‘So, rather than opening up and allow everyone to deal with the chaotic nature of normal life, everyone is reduced to watching snowflakes fall. Maybe they’ll wait until the whole edifice collapses under the weight of the snow. Then, trembling with fear, people might finally scream out loud.’

Later, when Qin Gang, then Minister of Foreign Affairs, suddenly disappeared in June 2023, you said on another platform that:

‘There are numerous people like Qin Gang who, no matter how high and mighty they become, make a misstep and simply vanish from sight, as suddenly as a melted snowflake. Then it’ll be as though they never left any impression at all on this magnificent land.’

What is it about you and snowflakes? What do they represent for you?

Teacher Li: K. I first wrote about snowflakes on my old Weibo account, during the lockdown at Foxconn when quite a few workers killed themselves by jumping off buildings. I was mostly responding to that.

As a child, I had the same kind of patriotic indoctrination as everyone else. At school, we were all taken in by that grand narrative that we were taught [about Chinese history]. It was drummed into us that some people had to pay a price so that our nation could become strong and wealthy. As a kid, I thought that the people who were sacrificed were like snowflakes, like a decoration on that impressive tower. They made the tower seem all the more majestic.

Later, when you grow up, you want to scale and examine that tower for yourself. Eventually, you realise that you’re also one of the people who’s being sacrificed to sustain that grand narrative.

So when I responded to all of those suicides [at Foxconn using the image of snowflakes] I was also aware that people were being sacrificed for the sake of the government’s absurd Zero-Covid statistics, out of desperation some people even jumped out of apartment windows. They drifted down to the earth, just like snowflakes. To me it seemed absolutely crazy. Gradually, it occurred to me that common people like me were not the only snowflakes, even high-level government bureaucrats — the ones who lord it over the masses — they too are nothing more than snowflakes and, if they weren’t careful, they too would fall into oblivion. So, the much-celebrated ‘Prosperous Age of China’ 盛世 is, in reality, a ‘prosperous age for one person’ [that is, Xi Jinping].

Li Yuan: So, what you’re saying is anyone may be sacrificed for the cause, or simply melt away like a snowflake, and that no one will be the wiser. Everyone’s just supposed to go along with it all. Is that what you mean?

In September, you posted a video about politics-induced depression on YouTube in which you said one way to cope with the kind of political malaise that people are experiencing in China today was to cut back on consuming unnecessary information or news that was too emotionally draining. But how about yourself: you spend at least five to six hours on Twitter every day, reposting material that’s been sent to you. You’re deliberately exposing yourself to a world of hopelessness and political impotence. How do you keep going and have you thought of quitting? Or, rather, why haven’t you simply stopped? Frankly, I’m in awe of your resilience. Sometimes I can’t face checking Twitter myself.

Teacher Li: I get your point, but I’d respond by pointing out that I am driven by a sense of mission and of responsibility — as well as being a Twitter-addict. There’s all those people waiting for you from before you even wake up in the morning, hoping that you’ll broadcast their voices. You feel that you simply have to keep going. As for how long I can keep it up, I seriously thought about quitting back in April this year.

Li Yuan: How come?

Teacher Li: The pressure was just too great. At the time, there were some pretty intense things happening in my private life and, on top of that, the police turned up repeatedly at my mum and dad’s place back in China. Of course, they weren’t necessarily always threatening; sometimes, they even came bearing gifts and the like. But I knew it for what it was: harassment. Right after the White Page protests although the political demands of protesters went unfulfilled, but they’d helped pressure the authorities to abandon the Zero-Covid policy. At that point I pretty much felt as though I could call it quits. My Twitter account had fulfilled its mission and it was about time for me to turn to something new.

Actually, at the time, I felt at a loss and wasn’t sure what I should do next. It coincided with the fact that some of the ventures I was involved in back in China had been closed down, and then there was my status as an overseas student and issues with my mentoring activities. It was all over and I was unemployed. And it’s not as though I could monetise what I was doing on Twitter, but I couldn’t simply expect to survive on people’s charity. So, I was thinking that I could hand control of my Twitter account over to someone else, or even close it down altogether. Maybe I’d stay on in Italy and find something to do here.

My parents wanted me to stop and suggested that they could send me a monthly stipend as though I was still studying. Then, in April, the Chinese authorities shut me out of my bank account and even my gaming accounts were suspended. It proved that they weren’t going to let me get away with what I’d been doing and it meant that there was no going back for me. So I reckoned, since they were on my case, I’d keep up the fight from my end. My belief in the righteousness of my cause had been further inflamed by my sense of personal grievance. That was back in April.

Li Yuan: That’s to say that the Communist Party turned you into a permanent rebel.

Teacher Li: That’s right, at my end it was like a conditioned reflex. By constantly pressuring me they created the very thing they didn’t want… making me increasingly, what would you call it: extreme? Though I don’t really feel …

Li Yuan: … like an extremist. I don’t think you are.

Teacher Li: But they kept ramping up the pressure, forcing me into public rebellion regardless of what they thought they might achieve. I’ve come to accept it now and my rather small account has become a big account, though I reckon a good sixty to seventy percent of the traffic I get is a result of their efforts.

[Excision, from minute 32:47 to minute 37:40]

Li Yuan: So, now, YouTube is your main source of income?

Teacher Li: That’s right and it’s enough to keep me and my cats going. However, since I think of myself as having no future to speak of — because my eyes are wide open — I won’t be surprised if suddenly a gang of people broke into my place and I ended up “jumping out a window” [that is, being defenestrated]. Or, I might end up topping myself because of extreme political depression. You know what I’m saying? You have to put things in perspective, and that means I don’t necessarily have to devote myself to making money or saving for the future. Of a month, I pretty much spend everything I make.

[Note: ‘A large following on X has brought Mr. Li little income. His account had more than 300 million views from Oct. 15 to Nov. 1, he said, earning him $280. To make a living, he started a YouTube channel in July, posting videos commenting on Chinese current affairs. Revenue from ads and donations bring him little over $3,000 a month on average, enough to feed himself and his two cats, he said.’ — Li Yuan, NYT]

Li Yuan: I’m really surprised to learn that you have such a dark view of your future.

Teacher Li: Relax; it’s just that I don’t particularly see that I have much of a future at all.

Li Yuan: Why do you think that? I feel that you’re a kind of hope for China’s future.

Teacher Li: I see it like this: the Chinese police really have it in for me and I know that because of just about all the people who’ve been ‘invited to tea’ and interrogated about me report that the authorities really, really hate me. They do so for various reasons, including because what I do has really added to their work load. On top of that, they’re worried that some of their own people might even send me some snippets. That anxiety means that they have to do a lot more of what they call ‘thought work’ [that is, ongoing indoctrination and brain washing] among themselves.

Even though I think of my account as a news service, that’s certainly not the way they see it. From their perspective, the longterm threat I pose is that, maybe some day, I might suddenly call on my followers to take to the streets. What if they actually do? So they are constantly on my case; they want nothing so much as to drag me back to China. Failing that, what other options do they have?

So that’s why I’m psychologically prepared: it’s okay if I die at any point. And, when I do, at least I’ll know that my account is part of the larger story … There’ll be a fitting conclusion to my tale. I’ll be remembered as being someone who devoted themselves to a cause and persisted right up to the end. That would be the most fitting. If I don’t die, however, then I have a feeling that things will just drag on as they are.

So, that’s why I’m so relaxed about things nowadays. With this kind of mindset I’m no longer scared of them and I don’t get all worked up about what I’ll do next. I’m not afraid. They can come calling any time they want.

Li Yuan: So, though you might have prepared for the worst possible scenario, you’re not actually going to do anything about it yourself, right?

Teacher Li: That’s right, I’ve just adjusted my attitude. I’ve got over the political malaise I was going through and now I’m in a much better place. I’m encouraged by seeing that some Chinese are willing to stand up and are aware of the need to fight for their rights. Even if it’s only something like those high-school students protesting over their holidays [as in the case of the ‘2nd of September uprising’ in the city of Yongcheng, Henan province]. Thinking about things like that helped me get over my lethargy.

Li Yuan: So, you’ll keep relying on your YouTube channel for an income. Will you get someone to help out, as well? Or will you be posting videos on a more regular schedule?

Teacher Li: Actually, I’ve had lots of friends who’ve wanted to organise a support team that might help reduce the danger facing any single individual. But, I don’t really want to involve anyone else, whether it’s helping running my channel or to become a YouTuber with me. Because I know what I’m doing is very risky and I don’t want to implicate anyone else. So, I’ve never really done anything about getting anyone to help out.

In the future, it’d be good if more accounts like mine appeared; even now there are a few, like Yesterday, which posts information about protests in China. So I think that it’s inevitable that more independent accounts will be created and they will attract submissions and gather information. Over time, I might even be able to let go and get back to my original interests — painting or at least teaching art. When I’ve completed my mission maybe I can have the kind of life that I’d originally planned for myself.

[Excision, from minute 42:57 to minute 46:57]

Parallel Chinas

Li Yuan: …. At the time of the Blank Paper Movement, you spoke about two co-existent realities. One was the blank paper protests in first-tier Chinese cities which were directly influenced if not inspired by Peng Zaizhou’s rebellious act at the Sitongqiao Overpass in Beijing [on 16 October 2022]. During those protests many people chanted his slogans. The other reality unfolded elsewhere. It consisted of: 1. the mass protests and clashes with the authorities like at the Foxconn Factory [in Zhengzhou]; 2. Civilian unrest in Ürümqi [following a deadly fire in an apartment building on 24 November] during which protesters stormed a military headquarters; and, 3. Tens of thousands of demonstrators took to the streets of Wuhan on 27 November [destroying metal barriers and overturning Covid testing stations].

You observed that: ‘The blank pages and slogans in major urban centres attracted the most attention, but they were something of a distraction from the core issues behind the protests of the masses elsewhere that reflected that anger of people on the lower rungs of society who have been repeatedly sacrificed for the sake of maintaining the lifestyle of others who are better off. People had no other outlet, no one was concerned about their circumstances and that left them with no choice but simply “to disappear in silence and, before they did, to explode”.’

[Note: Here Teacher Li reworks the line ‘不在沈默中爆發,就在沈默中滅亡’, a famous quotation from ‘Remembering Liu Hezhen’ 記念劉和珍君, an essay by Lu Xun written to commemorate a student who was killed during an anti-government protest.]

A year has gone by since those parallel protests broke out. Do you think that these two very different phenomena — one centred on elite cities, the other dispersed among the lower rungs of society — continue to unfold in parallel? From what you understand, have there been any changes to or contact between the two?

Teacher Li: They are co-existent. Occuring during the same time period they shared certain commonalities, in particular because they all opposed the harsh Zero-Covid policies. Even so, their demands differed. The mass protests called for an end to lockdowns, a demand for work and for a return to normal life, while the opposition in the big cities, in particular for intellectuals at universities, also agitated for more fundamental change. The latter groups knew that even if the restrictions were lifted for now, in the long run the authorities would inevitably impose further restrictions. That’s why people agitated for more systemic change. The shared aspirations of both groups — an end to harsh lockdowns — meant that two very different kinds of protest enjoyed a moment of unity and it ended up that people went into the streets at the same time.

Now, a year later, I don’t see any evidence that these different constituencies are taking any joint action. So, I can’t really answer your question. Of course, when people mourned the Li Keqiang that was another moment when ‘the elites’ and ‘the masses’ shared a common impetus to express themselves. This was particularly evident online where lots of people said ‘If only it had been him [that is, Xi Jinping]’.

Of course, insofar as they are all living in the same country and are faced with similar things, these very different groups do have overlapping interests to agitate for change. Although their demands might be different at a particular moment, there is also a certain overall unity. Behind the shared reaction to Zero-Covid, people had various agendas and aspirations.

Li Yuan: It’s really hard to be definitive, isn’t it? I feel I need to reassess my previous analysis since, during last year, I failed to pay enough attention to the welling up of mass protests. So, we can’t really claim that the main reason that the authorities lifted the lockdowns was the White Page protests or that it was even the mass agitation at places like Foxconn in Zhengzhou and in Wuhan.

Teacher Li: At the time, I had the feeling that people were too focussed on those slogans [being chanted by protesters in Beijing, Shanghai, etc], which had originated with the Sitongqiao Overpass incident, as well as on the people holding up blank pieces of paper. In Wuhan, however, the city where the largest demonstrations broke out, no one was carrying blank sheets of paper. The demonstrators were focussed on smashing the barriers and partitions [erected as part of the Zero-Covid lockdowns] and demanding a return to work. It’s all too easy to overlook the demands of that broader constituency.

***

***

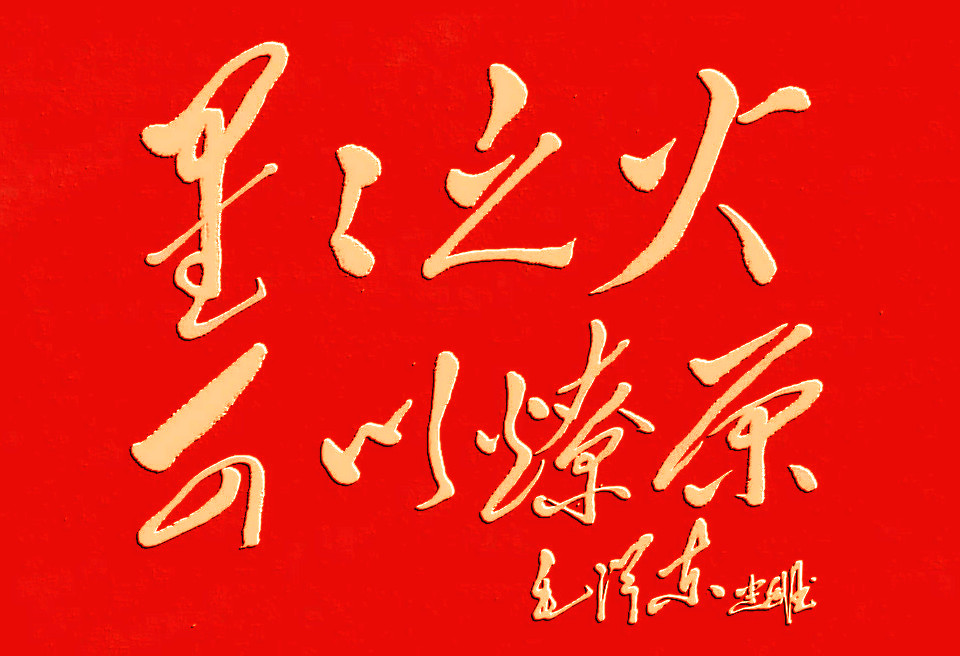

Illuminating Sparks

Li Yuan: You posted a tweet following Li Keqiang’s death that read:

‘Today, I’ve been putting out a lot of posts related to the public mourning for Li Keqiang and some people have responded that such individual acts of resistance don’t mean much. The way I see it, however, is that “sparks” [星火 xīnghuǒ] don’t necessarily have to “start a prairie fire” [燎原 liáo yuán]. That’s because by their very existence, sparks illuminate their surroundings and alert us to the existence of decent people who share our sense of justice. They let you know that you are not alone.’

Do you think of yourself, or rather your Twitter account, as being such an illuminating ‘spark’? That’s do say, do you get lots of messages every day that, in effect, are telling you that your activities give people the feeling that they are not alone?

[Note: In January 1930, Mao Zedong wrote a letter to Lin Biao berating him for underestimating the potential of a mass revolutionary uprising. An ancient expression that Mao used in the letter — ‘a single spark can start a prairie fire’ 星星之火,可以燎原 — was used as the title of the piece in the Maoist canon and it remains a leitmotif for revolutionary hopefuls everywhere. ‘Sparks’ 星火 xīnghuǒ and ‘Seeds of Fire’ 火種 huǒzhǒng, ‘tinder’ or ‘kindling’, a term used by Lu Xun in 1936 to describe people and ideas that were ‘combustible’ and that could bring about fundamental change in China, have featured in popular discourse, as well as the ‘mytho-poetic historical complex’ we have described elsewhere ever since. See also Ian Johnson, Sparks: China’s Underground Historians and Their Battle for the Future, Oxford University Press, 2023.]

Teacher Li: Given the heft of my account, I reckon that I could actually claim that I’m a beacon. (Li Yuan: That’s quite a boast. Good on you!) I mean, the sheer scale of my account makes it quite formidable.

I say that because there are many people who don’t necessarily appreciate the impact of what I’m trying to do. They think that my efforts are like adding a single blossom to the overall floral tribute, a mere drop in the ocean with no impact or meaning. It changes nothing. But, say during that moment of mourning for Li Keqiang, there were lots of people who felt powerless to do anything, or they lacked the courage to express their feelings publicly. But when they saw that I was posting news about what was going on, they might realise that people in their city were already going out to mourn the premier with floral tributes, or expressing themselves in other ways. It buoyed people’s spirits; it taught them that things aren’t quite what you think they are; people aren’t quite as disinterested as you might think. Society is not indifferent. In fact, there’s many other people in your city who think and feel just like you do.

[Note: ‘Kathy’, a Chinese student studying in England makes a similar point about ‘an awareness of community’, or at least shared values, in her interview with Li Yuan. See Awakenings — a Voice from Young China on the Duty to Rebel, 14 November 2022.]

Li Yuan: In your tweet that line ‘such individual acts of resistance don’t mean much’ set off a bit of an online discussion. Do you ask yourself that same question, whether your individual acts of resistance mean anything? Previously you probably had your doubts, do you still?

Teacher Li: Actually, no, I didn’t. I’ve always been very clear about what I’m doing, and that is to contribute to a better China. People often write to thank me for helping them know about things that are going on in China that they otherwise couldn’t learn. This was particularly so during the mourning for Li Keqiang, and people wrote to express their gratitude because despite attempts by the local authorities to ban commemorations my posts let them know what was actually happening in their own cities. They told me that they were relieved that what they were feeling was not unusual and that most other people felt just like them.

Li Yuan: So, you daresay saw all those comments about the commemoration of Li Keqiang actually being the expression of a popular yearning for a legendary ‘upright official’ [青天 qīng tiān] and that the lack of such paragons in political life is the real reason why China isn’t democratic and why the the democracy movement is a failure. Again, the message one got was that, even though people were expressing a measure of opposition to the status quo, they were doing so from a place of relative safety and that, ultimately, it didn’t amount to anything.

[Note: ‘Upright official’ or ‘clear-sky official’ 青天 qīng tiān or 青天 qīng tiān guān, is an old expression used to describe a just, incorruptible and decent official. The most famous ‘clear-sky official’ is Bao Zheng (包拯, 999-1062 CE) of the Northern Song dynasty, who is popularly known as ‘Clear-sky Bao’ 包青天 or ‘Lord Bao’ 包公.]

Teacher Li: In my opinion, from the moment that public mourning Li Keqiang was banned, mourning itself became a form of public resistance.

As for whether people were yearning for an upright official, the actual situation on the ground in China means that none of that talk about democracy or mass movements really means anything to people. There simply isn’t that kind of civic awareness. If you ignore all of that and presume that people only want a good official rather than being able to enjoy the fruits of democracy, that’s not quite right either. People are not there to fulfill your aspirations and you can’t criticise them for not living up to your demands or hopes. If it’s so important for you, you go devote yourself to it.

What’s China’s on-the-ground reality, or ‘state of the nation’ [國情 guó qíng]? Most people have no idea what is really going on in their own country, let alone what’s happening in their own vicinity. You think you can tell them what Li Keqiang did during his stint in Xinjiang, or what he got up to when he was in charge of Henan province? [Neither periods in Li’s political career were particularly praiseworthy.] They simply don’t have a clue, or even the wherewithal to take it in. For them, Li Keqiang was ‘a good man’ [好人 hǎorén], a decent person, plain and simple. They remember that during the Zhengzhou floods [in Henan in July 2021] he said some things that seemed genuinely moving, or that he said a few true things [such as, China has 600 million people with a monthly income of 1,000 RMB]. He seemed personable and relatable. That’s about as much as most people know about Li Keqiang.

[Note: For more on the political failures and mixed legacy of Li Keqiang, see Li Keqiang, the ‘Empty Boat’ of the Xi Jinping Era and Monster Mash — Mourning a Dead Premier & Mocking the Ghouls Among the Living.]

So, for them, a good man was died and they were moved enough to mourn his passing. Of course, they will also be wondering how a relatively young state leader could die from a heart attack in such unexpected circumstances. Maybe there was even foul play? Meanwhile, they were all thinking: that fellow [Xi Jinping] is now into his third five-year term and he’s even got himself a new premier.

So I do my best to help people understand and, in the process, I also have to try and appreciate how people are feeling, I have to ground my approach in Chinese reality and do my bit to appeal to people’s sense of civic awareness. Only when significant numbers of people share a broader appreciation of civic consciousness can China be gradually nudged forward. If you are thinking that suddenly one day people will go into the streets and demand democracy, well, you’re kidding yourself. All that shouting of slogans about ‘democracy’ and ‘freedom’ — what kind of realistic view of social change does that really reflect? Even if you plaster the streets in such slogans most people still won’t have a clue what you’re talking about.

Li Yuan: I guess neither of us have a worldview that’s based on the official ‘core socialist values’…

Teacher Li: True enough and that’s why, when you ask me for some recommended readings in a moment, one of my picks is Xi Jinping’s On the Governance of China. People need to get into it.

Li Yuan: That’s right and people have to study His Thought regarding the correct management of online activities, blah dee blah.

In your online writings you often touch on the topic of ‘love’. You ask: ‘What’s exactly is love?’ You observe that the only true wealth that everyday people have is the power of love. You’ve also expressed a hope that people will talk about love more. You’ve also expressed a fear that your love is often too pointed, so much so that it can be damaging. You’ve said: I’m always in awe of people who are loved and that most of the time most of us merely put on a show of truly understanding what love means.

In your old WeChat account you even published a longish essay that people dubbed ‘A History of the Disappearance of Pure Love’. You’ve also warned that love can be used to cover up and avoid real social issues. For example, you’ve said: Love can’t transform a person who is addicted to domestic violence, just as you can’t remake a nation with love alone, especially when you can’t meaningful differentiate between the state, the government, a political party and yourself.

Can you tell us why you are so obsessed with this topic? And what is it about the subject of love that so troubles you?

Teacher Li: It’s a big topic for me because I’m one of those ’emotive influencers’ [that is someone who attracts followers by revealing details of their personal life]. Nah, just kidding. But it’s true, I often used to write things about love on WeChat, including offering my so-called insights. A lot of my artwork also takes love as its subject matter.

For me, love is at the heart of who I am and what I do. I’m driven by love for my homeland to do all of this, a love that hopes for the best. I love my parents and I hope to see them again. I love the people here where I live and I hope that things go well for them. During the pandemic lockdowns, I longed for freedom. I’m entirely motivated by love and express it in my art as well as in my writing.

That’s why I often talk about love in the things I post. It’s because love is such an important part of all of our lives. Love is the motivation behind why so many people do things to improve the world. If I hated China or its people then I wouldn’t be expending all this energy doing what I do. I’d just get on with my own life. The power of love is what compels me forward.

***

***

Monsters: ‘The best revenge is not to be like your enemy.’

Li Yuan: Many people become hardened by the struggle itself. As Nietzsche famously put it [in his book Beyond Good and Evil]: ‘He who fights with monsters might take care lest he thereby become a monster.’ That is, in the process of your struggle you may well end up being the same as your oppressor. How do you manage to strike a balance between your resolute determination to resist and the soft demands of the kind of love that you espouse? I ask because everyone sees how, on the Chinese-language international internet, even people who think of themselves as being ‘liberals’ expend inordinate amounts of energy and vitriol arguing with and attacking each other. The level of animosity, and hate even, is such that it seems to be just as vicious as the attacks that they launch on the real enemy. I’m somewhat baffled by these exaggerated levels of animosity. How do you reconcile those two very different impulses — fiery resistance and embracing love. How does one maintain a sense of loving forbearance in such a poisonous environment?

[Note: ‘The best revenge is not to be like your enemy’ is a quotation from Marcus Aurelius.]

Teacher Li: Yes, indeed, that quote from Nietzsche is spot on and, I must admit, in my own struggles I too have felt my heart hardening.

Perhaps the most agonising aspect of having a public account like mine is that I hear from quite a lot of people who are thinking of killing themselves. They want to tell me things and, at first, I tried to cope… tried to offer them understanding and support, even spending a little time with them in the hope that they would change their minds. But, after a while, I discovered that it was of no use. They might get in touch one day and we’d talk for ages then, when I woke the next day, there’d be a farewell message waiting for me. They’d disappeared. Things like that happened five or six times a month.

Li Yuan: That many?

Teacher Li: Yes. Over time, I had to harden myself in response to that kind of situation and when people sought me out I simply wouldn’t respond. They might share their troubles and so on, but I’d just keep quiet, even when I felt as though I wanted to reach out. So, what you said just now really strikes a chord with me. I never imagined that I’d become like this and I feel really guilty about it. If I ignore them… But there isn’t anything I can do. If I took them all on I don’t think I could cope at all.

Li Yuan: If you don’t protect yourself, you simply won’t be able to function or do what you want to.

Teacher Li: … I think all of the online squabbling and arguments are pretty normal. In an open society, everyone feels free to express their opinions and ideas. Debates, or rather squabbles, should be seen as being par for the course. Sadly, in the context of China, however, things invariably end up with accusations being made that you are a Communist or a sympathiser. (Li Yuan: ‘A propagandist working to influence international opinion’ 大外宣 dà wài xuān, in other words.) Exactly! Things always end up in the same place. It’s extremely unfortunate.

Lots of people attack me as well, or try to pick a quarrel with me. In most circumstances I lean towards tolerance and acceptance; they have a right to exist, too. When it comes to overt abuse, however, I just block them. If they are inclined to discuss their issues with me, I’m okay with that. As for all those pitched battles online in which everyone proves to be completely unforgiving, they leave me feeling despondent.

Li Yuan: Now I’d like to ask you a question about the younger generation of protesters and how you feel they differ from the June Fourth generation of dissidents [in the late 1980s and early 1990s]? You’re aware that the dissidents of that era are aging and you also know about their online behaviour. What do you think about your own future — what kind of person do you hope to be in, say, thirty or forty years? Although you just said that you have no long-term plans, still young people like you generally have some kind of expectation about or hope for how they’ll turn out in the end. More broadly speaking, what kind of country do you hope China will be in the future?

Sorry, that’s quite a pile of questions. What I’m interested in is the kind of promises that you make to yourself, and what you think of the older generation and what your hopes are for the upcoming generation.

Teacher Li: In the first place, I think its a different age and that those two forms of protest are very much the product of very different circumstances. Up to June Fourth [and the Beijing Massacre], people had been living in a relatively more relaxed political environment and protesters from around the country had been free to converge on Beijing and actually occupy Tiananmen Square. They were even able to pressure government leaders into engage in formal dialogue with them. And they launched a mass hunger strike [to pressure the authorities]. Of course, they also paid a heavier price [than the White Page protesters], some even with their lives.

In our era, one in which online life is so developed, lots of people don’t even think about protesting in the streets. They follow things on their phones and feel that they are participating by posting things on Weibo or in a friends’ chat group. Having said that, the space for public expression, control over what you say and do, is far more extreme these days. You can’t just issue a call for people to gather and demonstrate: your message will be deleted before anyone has even seen it. So, the level of control is different from the past, as is the ever-present atmosphere of terror.

Back in the day, the June Fourth protesters could flee the crackdown and even get out overseas. These days, lots of people that I know about in China have had their passports confiscated. The ways in which people protest reflect their circumstances. Ultimately, I don’t think there’s much value in making a forced comparison between the protesters of June Forth and the White Page Protests of today, or in thinking that the former were more courageous and the latter have proved to be more creative.

To my way of thinking, June Fourth was an endpoint since, once they had cleared the Square [on the morning of 4 June 1989] China entered a three-decade-long era of silence, one during which there were no other comparable mass demonstrations. The White Page Protests, however, were more like a beginning. Although I’ve got a pile of interview requests from various media outlets seeking my reflections on the first anniversary of the White Page Protests, I’ve turned them all down. It’s because I feel that the White Page Protests marked the beginning of something, not the end, so I don’t feel like commemorating them as though it is all over. If, in ten or twenty years time, it indeed turns out that the protests were just a one-off thing, there’ll be time enough to commemorate an anniversary.

Li Yuan: Then what do you think of the old protesters from 1989? How does their experience speak to you?

Teacher Li: I have nothing but respect for them. There’s people like Zhou Fengsuo [周鋒鎖, 1967-] who are still actively engaged. He supports new groups and is involved in all kinds of ways. Or there’s organisations like Humanitarian China that help lots of people. I’ve got a great deal of respect for such groups. In say thirty or forty years I hope I’ll be able to be someone like Zhou Fengsuo.

Of course, there’s some of the older generation who cast aspersions and accuse others of being Communist agents of influence. They’re a reminder that I don’t want to end up like them. Long into the future, I hope people will think well of ‘Teacher Li’, though I also hope that I’ll be remembered as an artist or for doing other things as well. It’ll give my life some sense of accomplishment. Maybe, by then, China will be in a better state than it is now, or at least there will be more outlets like mine. Maybe, at least, there’ll be a better environment for [dissenting Chinese] overseas so accounts like mine will be unnecessary. Anyway, that’s my hope.

Li Yuan: I share your hope.

Teacher Li: At least I want things to change to the extent that someone like me becomes superfluous. That’ll be proof that things are improving and that things in China are getting better. What kind of China do I hope to see? I really haven’t ever said anything about that. Significant change in China has to be rooted in Chinese realities. It’s a question that all Chinese people need to ask themselves. What kind of China do you wish for: the answer is up to you; the future is in your hands.

Li Yuan: A final question — ‘asking for a friend’, as they jokingly say in America — when do you think you’ll be able to return to China?

Teacher Li: I don’t have any plans to go back. I knew from when the White Page Protests broke out that I’d never be able to return. I gave up thinking about it long ago.

Li Yuan: In effect you’re saying that you don’t see a significant change to the Communist Party’s domination of China during your lifetime?

Teacher Li: Not necessarily. Like I said earlier, everything is highly circumstantial and unpredictable. I don’t waste time speculating about the future — ‘Woe is me! When can I go back home?’ I just don’t think about it. Since it’s impossible, I’ve stopped thinking about it. Anyway, there’s no way I’ll be going back while they’re still in power, and that’s why I don’t give it any thought. It’s as though I’ve become one of those cinematic superheroes: in life you’re some pathetic loser, but sitting in front of a computer screen you’ve got all of this attention, over a million Chinese following you. It’s truly bizarre.

Li Yuan: A kung-fu warrior that everyone is paying attention to, despite the fact you’re actually broke. In the context of crass mainstream Chinese values, do you feel that they are losers, too, though with an outsized influence?

Teacher Li: Yeah, it’s sort of the paradox of my situation. Over past twelve months quite a few people have expressed that hope that I could play the role of a sage, a holy man. They seem to think that you don’t actually need an income or money — it would actually be sinful for you to make money out of what you do. Yet, without money, people look down on you and that reinforces a commonplace view that you can’t make money doing this kind of work. So I feel very conflicted.

Not that any of this influences me unduly. After all, I didn’t set up my account to make money. Of course, money is important if you want to survive, but making money isn’t my concern. I feel that my account has brought me a lot of satisfaction: I’ve garnered heaps of attention as well as a great amount of online traffic and that’s made it much easier for me to launch a YouTube channel that it is for others. Many other people have done much more than me, but they’ve ended up in jail and have soon been forgotten. Even when people have issued appeals on their behalf, no one really cares. At least I’m living free outside of China. So, all in all, I’m in a pretty good place.

Li Yuan: To turn that line from the writer Murong Xuecun (慕容雪村, 1974-) on its head: ‘You can’t let the person carrying the firewood freeze to death in the wind and snow.’

[Note:

“He who holds the firewood for the masses is the one who freezes to death in wind and snow.” 為眾人抱薪者,不可使其凍斃於風雪。 The original version of the saying came from the Chinese writer Murong Xuecun about seven years ago when he and some friends were raising money for the families of political prisoners.

It was written as a reminder to people that it was in their interest to support those who dared to stand up to authority. Many of those people had frozen to death, figuratively speaking, as fewer people were willing to publicly support these dissenting figures.

— from Li Yuan, Widespread Outcry in China Over Death of Coronavirus Doctor, The New York Times, 7 February 2020.]

Teacher Li: You can’t really blame people. They were courageous enough to speak up, even if they couldn’t get their message out. Within the Great Wall of China, you simply have no clue that people have spoken out on your behalf in the past, or have decried the injustice you’ve suffered. Take, for example, Peng Zaizhou [Peng Lifa, 1974-]: is his protest known about more widely? Compared to such people — my elders — I really am lucky.

Li Yuan: Yes, no doubt… and you’re so much better off than many many others in China. At least you’re free, safe and able to have your voice heard. Too many people in China — as well as countless others we never hear about — remain unknown. That’s why your voice is so important, not only now, but it will be far into the future, since it is one that, whether people straddle the Fire Wall now, or at some point later, they will realise that at least there is one place like yours. They’ll be able to see the effort you made to record what has actually been going on, things that no one could see or know about in China itself. That’s why I also feel grateful to you, Teacher Li.

Teacher Li: You’re embarrassing me. Really, I’m just doing something that I want to. I’m behaving like a citizen in my own right, freely choosing my own path. I must admit that I’m subjected to lots of things behind the scenes — attacks, insults, lots of stuff like that. People accuse me of being a swindler, or they cast aspersions on my private life. You have no idea. There’s a lot of that kind of pressure and sometimes it can really get to me.

Li Yuan: I can well imagine.

Teacher Li: Generally, I’m not public about these goings on, nor do I name names, or anything like that. It’s also because I don’t want to spread a message of fear that may well put people off doing something similar to what I do.

Li Yuan: Many people suffer from exactly that kind of anxiety. I follow your personal account so I know that sometimes you feel quite dejected. Back in September, or maybe it was October, I noticed a very different tone in what you were writing … Maybe I was misreading things, but it seemed to me that you were feeling pretty hopeless about everything.

Teacher Li: Not really. Sometimes I just let myself get carried away. Over all, I pretty much maintain a deep sense of devotion to that land and its people.

Li Yuan: For someone as young as you, I’m really impressed that you can maintain such a level equanimity, despite what you’ve been through and regardless of what China is subjecting itself to.

Teacher Li: I’ve put myself on the line. Once you’ve been through something life-changing like this … Though I don’t interact with virtually anyone physically most days, even if I am engaging with lots of people virtually. My days are packed and I just focus on the goings-on that are unfolding in front of me. Despite all of these experiences, surprisingly I’m more calm than ever. That’s probably because I have a better appreciation of people back [in China] and what’s happening there.

***

***

Li Yuan: I really appreciate the fact that you agreed to speak with me, Teacher Li. As you know, it’s customary for me to ask my guests to recommend three books or artistic works to our listeners. Can I ask you for your recommendations?

Teacher Li: I knew this was coming and I’ve been anxious about it from the moment I agreed to this interview. What kind of thing do you think I should recommend?

Li Yuan: I didn’t imagine such a request would be that unsettling for you, after all, it’s not as though I’m asking you to predict the future of China.

Teacher Li: True enough. Actually, I have given it some thought and I’d like to recommend two books. One is The Story of Art by E. H. Gombrich, which still offers a good introduction to the subject. If listeners get a chance to visit Italy, they’ll find that this book offers useful background to the artworks they’ll encounter in the museums here.