Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium

Chapter XXVII

虛船觸舟

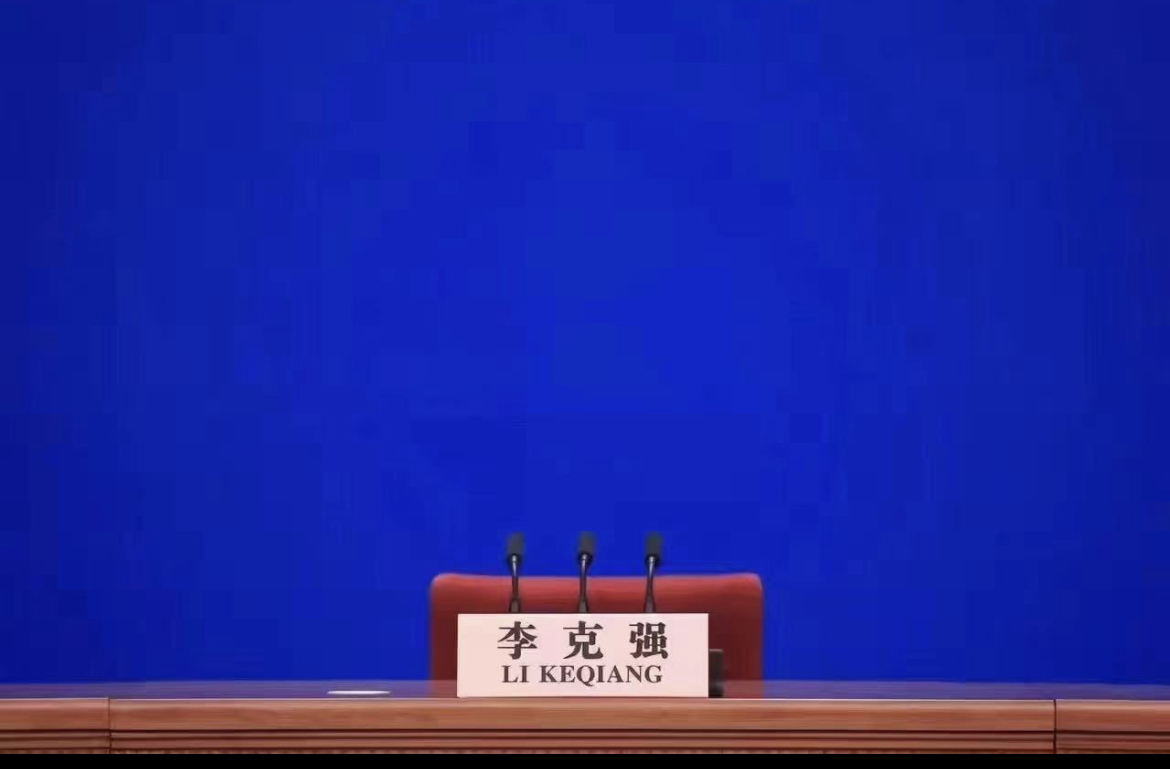

‘Frustrated in life, enfeebled in death’ 活得憋屈,死得窝囊. This was an epithet for Li Keqiang 李克强, China’s former premier who died on Friday October 27 at the age of 68, offered in an elegiac couplet (輓聯 wǎn lián) attributed to an anonymous author at Peking University, Lǐ’s alma mater, that circulated widely within hours of the announcement of his death. It was also a snarky reference to ‘glorious in life, magnificent in death’ 生得偉大,死得光榮, Mao Zedong’s famous epitaph for Liu Hulan 劉胡蘭, a fourteen-year-old Communist who was beheaded during the Civil War of 1946-1949.

The tenor of the couplet was in marked contrast to the wave of mourning that swelled over the following week, one that the authorities attempted to tamp down by issuing instructions to quash ‘overly effusive evaluations’ 評價過高的言論 of the dead premier. Anyway, as one independent Chinese journalist observed regarding the monotonous nature of the mourning for Li: ‘The space for speech in China has shrunk so much in recent years that many people have no experience or language to draw on when confronted with the need to express themselves publicly.’

Meanwhile, Li Yuan reported in The New York Times that:

Among many Chinese, Mr. Li’s death produced a swell of nostalgia for what he represented: a time of greater economic possibility and openness to private business. The reaction was jarring and showed the dissatisfaction in China with the leadership of Xi Jinping, China’s hard-line leader who grabbed an unprecedented third term in office last year after maneuvering to have the longstanding limit of two terms abolished. …

For them, Mr. Li, who had degrees in law and economics, represented the pragmatic technocrats who led the country out of poverty in the 1990s and 2000s.…

They recited Mr. Li’s most famous quotes: ‘Power must not be arbitrary‘ and ‘It’s harder to touch interests than souls.’ … The public’s response Friday [October 27] was the most significant outpouring of emotion since the White Paper movement last November, when thousands of Chinese in multiple cities went into the streets to protest the country’s harsh ‘zero Covid’ policies and many more people joined the outcry online.

Lun Zhang 張倫, a university classmate of Li Keqiang’s and a specialist in Chinese political and intellectual history based in Paris, observed that,

Li Keqiang was the most powerless premier in the history of the People’s Republic and as such he leaves no political legacy to speak of. If we are to talk about what little he left behind, you could say that in this era of enforced silence, when no one dares tell the truth, Li spent his time during Xi Jinping’s misrule holding things in and, when he was about to leave the political stage, knowing full well it was his last chance, at the very least he managed to make a few frank observations on behalf of the Chinese people… not that any of that made a whit of difference. … if one can find some comfort in the fact that a considerable number of decent everyday people have shown a measure of affection for him.

李克強他是中共建政以來最沒有實權的總理,所以他的政治遺產呢,就肯定就沒有什麼東西。他可能有的一些的遺產呢,可能就是恰恰在這個時代,在萬馬齊喑,這個人們都不敢再說什麼真話,整個是習近平倒行逆施的時候,他撐著那口氣,反正我要下台了,最後說幾句真話,替中國老百姓說幾句真話,面對中國的現實道幾句真情。但事實上呢,這是解決不了什麼問題的。… 畢竟他說的幾句真心話,還贏得了中國老百姓,善良的老百姓,人們對他真心的一些關愛吧。

As in the case of the death of Premier Zhou Enlai 周恩来 in 1976 and again following the demise of former Party General Secretary Hu Yaobang 胡耀邦 in 1989, people in China mourned Li Keqiang to express their own frustrations and anxieties. ‘Li’s humiliations,’ The Economist observed, ‘make him an icon for others whose hopes have been crushed in Xi-era China.’ Or, as David Bandurski of the China Media Project commented: ‘In a Chinese political context, there is always a great deal of forgetting in every act of remembrance.’

When considering the denouement of Li Keqiang in 2023, we are also reminded of Simon Leys’s observation regarding the enigma of Zhou Enlai:

…with all his exceptional talents, he should also present a sort of disconcerting and essential hollowness. Some 2,300 years ago, Zhuang Zi, giving advice to a king, pointed out to him that, when a small boat drifts into the path of a huge barge, the crew of the barge will immediately shout abuse at the stray craft; if however, coming closer, they discover that the little boat is empty, they will simply shut up and quietly steer clear of it. He concluded that a ruler who has to sail the turbulent waters of politics should first and foremost learn how to become an empty boat.

[Source: Simon Leys, ‘The Path of an Empty Boat: Zhou Enlai’, October 26, 1984, collected in Leys, The Burning Forest: essays on Chinese culture and politics, Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1986. The original passage in Zhuang Zi 莊子·山木 is: 方舟而濟於河,有虛船來觸舟,雖有惼心之人不怒; 有一人在其上,則呼張歙之, 一呼而不聞,再呼而不聞,於是三呼邪, 則必以惡聲隨之。 向也不怒,而今也怒。向也虛,而今也實。 人能虛己以游世其孰能害之 。]

***

***

Today, whether you characterize the Xi Jinping era as an age of stagnation, a state of malaise, or an empire of tedium, and regardless of the golden-hued nostalgia surrounding Li Keqiang’s memory, he too was essentially an ’empty boat’ that skillfully navigated treacherous waters. Li, like Zhou Enlai, was also ultimately an enabler who served a harsh and increasingly monomaniacal ruler; he was a collaborator in the excesses, follies and crimes of Xi Jinping’s first decade. Moreover, his ‘tragedy’ shares much in common with that of other Party leaders. As Liu Xiaobo 劉曉波 wrote in April 1989 during the national outpouring of mourning for Hu Yaobang, the purged Party general secretary:

Authoritarianism brooks no opponents, not even well-intentioned, helpful ones. For this reason the tragedies of Hu Yaobang and the rest of them are not personal tragedies but tragedies of the system itself; they are bound to be repeated as long as the authoritarian system remains. All of these tragic heroes have one thing in common: They were loyal but not trusted, they told the truth but were condemned for it.

[Source: Liu Xiaobo, ‘The Tragedy of a “Tragic Hero”: A Critique of the Hu Yaobang Phenomenon’, translated by G. Barmé and Linda Jaivin in New Ghosts, Old Dreams: Chinese Rebel Voices, New York: Times Books, 1992, p.35.]

In the days before Li Keqiang’s funeral at Baobaoshan, China’s state crematorium and columbarium, another elegiac couplet composed by his old Peking University classmates circulated online:

We remember the grand ambition we shared studying together at Peking University during that golden age, our energies focussed on how to create a better world

As our ways now part we mourn that you were never truly able to realise the dreams of our generation, your bequest is the unrequited hopes for the nation

憶燕園時光欣逢黃金歲月砥礪奮發後立修齊治平鴻鵠志

傷今朝永別惜君長才末展一代夢斷惟遺家國天下不了情

The dreams of the more open-minded members of Li Keqiang’s generation were initially stymied by the repression of 1989 and their denouement was, as we have argued elsewhere, presaged by the Counter Reform of 1989-1992, which in hindsight was a prelude to the Xi Jinping Restoration). When we ‘zoom out’ and consider the decades-long, multifaceted clash between ‘red’ 紅 (politically reliable) and ‘expert’ 專 (technocratic ability), we can also detect the lengthy shadow of the contest between Yan’an, the heartland of Party rectitude known as the Liberated or Red Zone 解放區、紅區, and the White Zone dominated by the Nationalist government — 白區、國統區 — where Communist Party members evolved a more sophisticated understanding of how to deal with the problems of modern government.

***

Li Keqiang bequeaths to China the spectres of three other elderly comrades whose passing may also afford people a chance to vent their frustration. They are: former premier Zhu Rongji 朱镕基 (95), Hu Jintao 胡錦濤 (81), Xi Jinping’s predecessor as Party General Secretary, and Wen Jiabao 溫家寶 (81), China’s premier before Li Keqiang.

Doubtlessly, Xi Jinping and his colleagues are already preparing for the passing of this long-superannuated troika and the opportunities their deaths may offer a restive population that has proven willing to express disquiet, dissatisfaction and protest in public.

***

Below, we offer two essays published on the day of Li Keqiang’s death. The first is by Li Chengpeng 李承鹏, an independent social commentator in Beijing. The second is by Wu Guoguang 吳國光, a political scientist at Stanford University who was a university classmate of the dead premier. We conclude our tribute with a poem by Jiang He 江河, one of the original ‘Misty Poets’ 朦朧詩人.

The essay by Wu Guoguang, like Eating Watermelon with Wu Guoguang, which was about the disappearance of China’s foreign minister Qin Gang 秦剛 and Lessons from the black box of Chinese politics, both of which were published by the now defunct China Project, is an ‘interpretive translation’. That is to say, rather than overly cluttering the translation with notes and bracketed explanations, I have, for the most part, incorporated them in the text and added a few stylistic flourishes of my own. I am grateful to Guoguang for indulging me. The translation of Li Chengpeng’s commentary also contains minor explanatory additions.

The Chinese originals of both essays and Jiang He’s poem are also provided.

‘Li Keqiang, the “Empty Boat” of the Xi Jinping Era’ is Chapter Twenty-seven in our series Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium. Our thanks, as ever, to Lois Conner for permission to use her work.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

14 November 2023

***

Related Material:

- Xue Laidi, Flowers in Hefei, China Media Project, 10 November 2023

- Monster Mash — Mourning a Dead Premier & Mocking the Ghouls Among the Living, 4 November 2023

- Chaguan, Why Chinese mourn Li Keqiang, their former prime minister, The Economist, 2 November 2023

- They’re Afraid, 26 April 2019

- Objecting 我反對, 5 March 2018

- Ninth of the Ninth 重陽 Double Brightness, 28 October 2017

***

The second time I passed Red Star Road, I heard two ladies who had just finished laying flowers and were resting on a bench. Their accents were thick and clearly not local, more like people from eastern Anhui.

I heard them discussing things in their local dialect that I thought only university students speaking Mandarin talked about. “This is the true heart of the people,” one of them said. “The last time the people honored someone like this, it was Zhou Enlai.”

“No,” the other woman corrected her, “it wasn’t Zhou Enlai. It was a doctor in Wuhan named Li Wenliang.”

— from Xue Laidi, Flowers in Hefei, China Media Project, 10 November 2023

***

A Man ‘Shelved’ Long Before He Died

Li Chengpeng

27 October 2023

translated by Geremie R. Barmé

So, he’s gone. He wasn’t even all that far from Zhongshan Hospital in Shanghai when it happened. Since that hospital boasts a 96% success rate in dealing with heart attack patients, don’t you find it just a little hard to believe that a former national leader ended up in the minuscule 4% of people who don’t make it?

In what seemed like but an instant after his death, people were already speculating that the song ‘A Pity it Wasn’t You’ would be pulled by the censors for sure. But, since so many things have been banned of late, including The Internationale, there’s no surprises there. Guess that’s the crux of the matter: Li Keqiang didn’t die so much as get pulled out of circulation and that was because he was a preordained loser in the struggle. Li had actually been ‘shelved’ long before he died.

If you consider the rules of the game, starting with the Qin dynasty in the second century BC, no prime minister has ever counted for all that much. The older people among us will remember mourning for Zhou Enlai in January 1976; the young will recall the deaths of Hu Yaobang and Zhao Ziyang. Now there’ll be the usual argy bargy about whether he should be mourned with due pomp and circumstance. Sure, there’ll all pretty much the same, still you have to admit that some of them demonstrated that they were slightly more human than others.

Doesn’t really matter if there’s no contention; after all, we’re all part of the same program, the same operating system, one that’s fueled by endless amounts of garlic chives and huminerals. It’s a self-perpetuating mechanism that involves oversight, control and sacrifice. The disgruntled rail against the inequities of fate while those inured to it find solace in a belief that at least they are ‘participating in a process of history in the making.’

But that’s just where you’re kidding yourself. Get real: you’ve never ‘participated in history’ so much as been infested by history, allowing it to manipulate you body and soul.

Can you think of any occasion on which the death of a premier actually resulted in regime change? But I’m no ‘nihilist’: although I don’t believe that in ‘historical laws’ as such, I do know that you can discern a pattern in the past.

In 1644, the 17th year of the Chongzhen reign and the last year of the Ming dynasty, the court was confronted by 6 major crises: financial liquidity, a plague, a civil war, foreign invasion, corrupt politics and the small ice age … How many crises have we racked up so far? You do the math.

Anyway, I’m waiting to see if the wind starts blowing in another direction, though sometimes I do worry that we’ll all end up being pelted by hail stones.

These days, people are so much more vile than under the previous regime. Everyone should be awake to the fact that no one gets to enjoy freedom without having to pay a price. You all waited for Keqiang to do something for you just as, from 2015, he expected the economy might benefit from his “dual creativity’ policy [that supported mass entrepreneurship and innovation]. What did that amount to? So, don’t put your hopes in people taking to the streets now. Anyway, even if they do, I’m guessing that you’d rather observe the scene from the safety of your own apartment. Don’t fool yourself in to believing you’ll enjoy any fringe benefits… How do you think it’s going to go down?

There’s this friend of mine who always had a pretty good read on the political situation. Back in the day, he reckoned that the economy would pull through, but recently his business has gone belly up. Before he put an end to it all, I mean, before he hit the road, he admitted to himself that ‘there’s no salvaging the situation; nothing’s gonna do the trick.’ No new premier will, or could, save things. And some people actually convinced themselves that we had a Mrs Thatcher on our hands.

Zhang Juzheng, a famous chancellor in the Ming dynasty, lived to the age of 58; Li Keqiang made it to 68; and Shen Shixing, also of the Ming, was 78 when he died. None of them had any significant impact.

By the time you’ve got the measure of our system and allowed it to get your measure in return and homogenize you, you know full well what fate has in store. Li wasn’t all that old and could still enjoy a swim. Pity that he dropped dead like that without warning.

At first you thought things looked pretty promising [following the appointment of Xi Jinping and Li Keqiang in 2012-2013], but the collab soon fizzled out. You thought we’d got two for the price of one. You thought we’d been gifted a blind box, but it’s actually Squid Game.

Of course, as Li Keqiang said: ‘it is as impossible for the open door and reforms to end, as it is for the Yangtze and the Yellow River to flow in the reverse direction.’ It was the kind of statement that fooled people into thinking that there was someone at the center of power who really did get it. Remember that other line of his? — ‘All under heaven means that everyone has a stake in it, that’s why there’s that saying about ‘everyone being responsible for the successes and failures of the realm’.’ It resonated with people. Li was relatable. Even when they confronted with unrelieved hopelessness, people still cling to hope.

So, my advice is this: if you can’t offer some fresh flowers to his memory, at least you can go get a bunch of plastic posies. — Did you know that China produces 97% of the world’s plastic flowers? Come to think of it, our fake flower industry has a higher market share than Zhongshan Hospital’s boast about the percentage of heart patients that it saves.

At the present moment, people are fixated on whether the masses will take to the streets with their flowers to commemorate him… … In 1976, they protested after Premier Zhou Enlai’s death, while it was mourners for Hu Yaobang, the purged Party General Secretary, in 1989. After that it was Zhao Ziyang, another purged party leader, that they remembered. Then there was the Blank Page protests of November 2022.

You get the feeling that in China only in death do our politicians offer an opening for possible change; at least, that’s when you can take to the streets bearing floral tributes … Today, it looks like people are passively waiting on the sidelines, scope out who might actually have the guts to do something. And this is how we treat political change in this place: wait and see. I might be a coward and I admit that I’m one of their number.

So, will there be some miracle this time around? If not, at least we have those bouquets of plastic flowers to fall back on.

People who have suffered harm surge forth bravely, generation after generation, in wave after wave. Then again, who’s to say: in this empire of ours there’s no telling who might bite the dust next.

***

Source:

- https://x.com/dayangelcp/status/1717856446233387276?s=46&t=Ui_QrHprvgDYWq8yYN6VWA, published on X on 27 October 2023

***

The Tragedy Represented by Li Keqiang is Far from Over

Wu Guoguang

an interpretive translation by Geremie R. Barmé

Li Keqiang, a man who was until March this year the second most prominent politician in China, died of a sudden heart attack at the relatively young age of 68. His passing has reverberated through the international commentariat and the editors of VOA have asked me to share my perspective. I felt duty bound to write something, though the following is little more than a series of disjointed reflections.

The Tragedy of a Generation

I have to admit that, at this moment, I’m experiencing a mixture of bitter regret and heartfelt sorrow. When the university entrance exams were revived after Mao’s death, some forty five years ago now, Li Keqiang and I were in the initial intake of students at Peking University. He was in the Faculty of Law; I pursued Chinese literature. Back then, campus life flourished and it wasn’t long before we came across each other. We were never particularly close, but we did bump into each other fairly frequently.

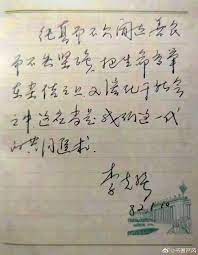

Last year, when sorting out my possessions before moving west to California, I came across an old diary in which I’d recorded some details of our relationship. I’d make a point of noting that Li impressed me as having an independent spirit and a mind of his own.

Although our paths rarely crossed after university, I distinctly recall the last time I saw him. It was at a symposium organized by the Central Committee of the Communist Youth League focussed on the future of popular non-Communist Party civil and political groups during the lead-up to the Thirteenth Party Congress [in 1987]. I’d been invited since I was in a working group tasked with developing an agenda for political reform presented to the Congress. Our hosts were Liu Yandong and Liu Qibao, both leaders of the League, and Li Keqiang, who by then was in the League’s secretariat, made a point of coming over to say hello. By that point I’d heard accounts from our alma mater that cast him in a pretty unflattering light. They related to the student unrest in late 1986 [when student demonstrators in Shanghai calling for media freedom and democracy inspired others in Beijing and elsewhere] when the Party’s Youth League had dispatched him to Peking University — a place regarded as a bellwether of the nation’s student life — to enforce order and help keep a lid on things. Word was that he took a hard line against the protesters and made sure that no PKU students joined the protests. It seemed fairly obvious that Li had abandoned the relative independence of mind that I had previously admired in him for the sake of his political future. At our final meeting that day we merely exchanged a few pleasantries.

I broke with the Communist Party and got out of China after the repression of the mass demonstrations on June Fourth 1989 and the next time I saw Li Keqiang was when I was teaching in Hong Kong. He’d risen to become governor of Henan province and I spotted him on CCTV. He was with Jiang Zemin, the head of the Party who had been installed after June Fourth. Jiang was undertaking an inspection tour of the province and Li looked as though he was a tour guide. There was no hint of the youthful enthusiasm that I remembered from our university days. What I saw instead was an unctuously attentive subordinate. Although he didn’t exactly fawn over Jiang, it was quite a show. Looking back on it now, it was obvious even then that he was already thoroughly ‘in character.’ I guess that’s what also made Li Keqiang something of a tragic figure.

Of course, the case of Li Keqiang is hardly an isolated one. How many young idealists have ended up following a similar trajectory? Whether for the sake of becoming a government official, or in the pursuit of money, power, and fame, people are all too willing to betray their inner voice and contort themselves as required in the service of baser ambitions. In the process, many turn themselves into useful handmaidens of power. They court the Party’s trust, crave official largesse, and serve willingly. According to the metrics of worldly success — power and influence — among our generation of 1977, Li Keqiang was without doubt the standout success. After all, he did end up as premier of China! By the same token, he was also the most tragic figure of a generation of young Chinese whose heartfelt aspiration was to play an ongoing role in helping the country forever leave behind the dark legacy of Mao.

A System that Kills Off Conscience

To be fair, though, I should note that even at the height of power, Li Keqiang demonstrated that he was not entirely free of the pangs of conscience. In reporting his death, many media outlets have recalled that rare moment back in May 2020 when he frankly admitted that 600 million Chinese were surviving on only 1000 yuan, or USD150, a month, despite all of the official assurances that Xi Jinping’s policy to eradicate extreme poverty was on track. People are also making a great deal of that observation he made during his farewell to the staff of the State Council in March this year that ‘heaven sees everything that we do and will judge us for it.’ At the time, this was taken as evidence of his frustration.

I remember when, during the early days of his tenure as premier, Li spoke about his childhood and the memories he had of seeing peasants begging for food. He said, back then, impoverished farmers would even apply for a letter of permission from their local party committee that they could use to protect them from official harassment when they were on the road. He was quite emphatic that China must never return to the benighted days of Mao.

Li Keqiang grew up in Hefei, the provincial capital of Anhui, and spent time in a people’s commune in Fengyang county as part of Mao’s policy for the ‘re-education’ of urban young people. Back in the day, because they simply couldn’t survive on the meagre annual harvest peasants in his commune were forced to go begging in the off season. I grew up in southern Shandong province, just north of Anhui, and I remember during the winter peasants from Anhui who would roam around our local villages going from house to house begging for food. Both Li and I were witnesses to that history and in the interview he gave, the newly minted premier showed that he hadn’t forgotten the past. To me, it showed that he was not entirely bereft of a conscience.

But, in retrospect, it was also proof of the tragedy he made of his own life. He of all people knew full well that the Communist system cannot tolerate anyone who tries to maintain a conscience. Maybe, at some point, he had actually believed that when he finally achieved a position of authority within the Party he would be able to make some positive changes; maybe he might create some space for the exercise of individual conscience? And, in reality, eventually, he really did get within arm’s length of the very pinnacle of power. In the final tussle of 2012, however, he lost out to Xi Jinping.

What were the factors that contributed to Xi’s winning China’s ultimate competition? Some people claim that his success lay in the fact that he hid his true ambitions; others claim it had everything to do with the to-the-manor-born self-assurance of a Communist nepo-baby. To my mind, however, it probably had to do with the machinations of former Party General Secretary Jiang Zemin and his fixer Zeng Qinghong. It’s speculated that those two were determined to frustrate the rise of Li Keqiang, the man who was supposedly Hu Jintao’s choice as successor. Just how the power play unfolded at the time is unclear; just another part of the murky inner workings of the Party itself. Yet it does beg the question: how come retirees like Jiang and Zeng ended up playing such a decisive role? Wasn’t it because they controlled the PLA, the legal system and the Party apparat? After all, if you hold sway over the organs of state violence, you can still effectively rule the roost. In all of the machinations there was no room for individual conscience; moreover, how could the Party elders tolerate someone who might actually believe in changing things for the better?

Since the system itself wasn’t going to accommodate him, Li Keqiang had no choice but to make peace with the status quo and there’s ample evidence that he suffered from a split personality, a kind of internal dissonance that was, to my mind, Li’s personal tragedy. Maybe there really were two Li Keqiangs: one, the twisted creature that clawed its way to the height of state power; the other, the shell of a human being that secretly nurtured the kind of common sense and decency you find in a normal person. Maybe behind the façade there was even a measure of sincere empathy for the Chinese masses. No matter: everyone knows that in China’s party-state, decency is regarded as a character flaw and one that can be exploited by your enemies.

When Xi Jinping and Li Keqiang started out on their decade-long collaboration in 2012-2013, Li simply didn’t have the cunning of Xi Jinping, a man who had long-ago mastered ‘the science of the thick and the black’ 厚黑學, acquiring in the process ‘an obdurate hide as thick as a wall and a heart as black as pitch.’ Since he simply couldn’t compete in these dastardly stakes, Li inevitably ended up being diminished by Xi. I would, however, emphasize that this was not necessarily due to any real machiavellian genius on the part of Xi Jinping, it was simply germane to the ecology of the Communist Party itself. The rules of the game mean that the more ruthless and calculating you are, the greater your chance of success.

[Translator’s Note: Xi Jinping’s parting shot at Li Keqiang came in the form of the official ‘death notice’ (讣告) the text of which extolled the genius leadership of Xi Jinping no fewer than five times. In comparison, Mao’s name was only mentioned four times in the obsequies for Zhou Enlai in 1976. The announcement also squarely laid responsibility for China’s Covid response on Li, even though Xi Jinping had boastfully claimed sole credit for the policy, that is until it foundered.]

Frustrated in Life, a Loser in Death—an example of ‘Stalin’s Logic’

Li Keqiang’s life was thus circumscribed by what, despite his position and prestige, was essentially a personal tragedy. His sudden death was a shock, coming as it did a mere seven months after he left office, and that before he had even reached formal retirement age. A personal tragedy followed by a sorrowful denouement. After all, a 68 year-old is, relatively speaking, still at the height of their powers and, in light of the excellent health care available to members of the party-state, we would have expected Li to have been able to enjoy many more years of life. Was there anything untoward or suspicious about his demise? Questions may well be asked, but there will be no answers. What I can say is that, no matter how you look at it, politics definitely played a role in Li Keqiang’s death. Regardless of whether he was assassinated, or died from a health condition exacerbated by long years of frustration and psychological distress, politics played a role; it always does play a role when a Party leader dies. This is as true in the case of victims of Stalin’s Great Terror, as it is in Mao’s persecution of his rival Wang Ming in the 1930s, or in the way he treated Premier Zhou Enlai — remember, Mao denied him appropriate and timely treatment for bladder cancer. There’s no dearth of Chinese politicians who, like Li Keqiang today, were ‘frustrated in life, enfeebled in death.’ Li’s demise is just another byproduct of what I call ‘Stalin’s Logic.’

***

The following section, ‘Stalin’s Logic,’ is drawn from Wu Guoguang’s essay ‘The Spiral Effect of Autocracy and Misrule: More on ‘Stalin’s Logic’ 獨裁與惡政的螺旋效應:再談‘斯大林邏輯’, VOA, 16 October 2023.

‘Stalin’s Logic’

What is ‘Stalin’s Logic’? It’s not the same as the ‘dark arts of imperial rule’ 帝王之術 of which Mao was also a master.

‘Stalin’s Logic’ is about the dialectical relationship between the autocrat and his misrule. For example, the extremism of ‘zero-Covid’ was abandoned without warning resulting in what’s called a ‘tsunami of Covid cases.’ Although he authored the catastrophe, the autocrat, Xi Jinping, remained beyond blame even as he punished those around him. The anti-market policies and the contempt for business entrepreneurs demonstrated by Xi over the years have had a direct and negative impact on the Chinese economy. They have threatened the employment prospects of over a hundred million people, and had a negative impact on the incomes and buying power of countless others, yet these misconceived policies are a signature of the Xi Jinping autocracy. Although milder in effect and more limited in scale than the man-made famines of Stalin in the early 1930s and Mao in the late 1950s, Xi’s zig-zag politics nonetheless share a lineage with those earlier misbegotten eras. Like Stalin and Mao before him, Xi Jinping has turned on some of his most loyal lieutenants in the wake of his policy missteps and disasters.

This kind of ‘policy spiral’ is in fact germane to the rule of Communist autocrats; flawed policies and political purges are mutually reinforcing. The more power the autocrat amasses the less he feels constrained: he launches policies on the basis of personal whim, despite the fact that they may readily result in disaster. Paradoxically, the more treacherous the political landscape becomes under the autocrat’s wilful rule, the greater the autocrat’s hunger for even more power, ever greater control. Insecurity and paranoia feed the autocrat’s belief that if only they had more power …. Purges and the dismissal of trusted underlings are a characteristic response to the political maelstroms they create and a knee-jerk reaction to the autocrat’s escalating suspicion that they are surrounded by potential enemies.

The Communist Party’s highly centralized top-down Bolshevik system, inherited from the Soviet Union and enhanced over the decades, offers the autocrat enticing levers of control the existence of which tends to further embolden the determined monocrat. Since, ultimately, they are not responsible to anyone, misrule is all but inevitable. The autocrat’s political missteps reinforce his belief that only more power will enable him to deal with the crises that are actually of his own making. This is the deep-structure of ‘Stalin’s Logic.’

[Translator’s Note: This vicious cycle characterized both Stalin and Mao’s rule. We would suggest that ‘Stalin’s Logic’ overlaps with the “artificial dialectic’ identified by Isaiah Berlin as early as 1951. Then Berlin observed that:

‘The avoidance of … opposite dangers—the need to steer between the Scylla of self-destructive Jacobin fanaticism and the Charybdis of post-revolutionary weariness and cynicism—is therefore the major task of any revolutionary leader who desires to see his regime neither destroyed by the fires which it has kindled nor returned to the ways from which it has momentarily been lifted by the revolution. …

‘Instead of allowing history to originate the oscillation of the dialectical spiral, he placed this task in human hands. The problem was to find a mean between the ‘dialectical opposites’ of apathy and fanaticism. Once this was determined, the essence of his policy consisted in accurate timing and in the calculation of the right degree of force required to swing the political and social pendulum to obtain any result that might, in the given circumstances, be desired. …

‘The governed, a passive, frightened herd, may be deeply cynical in their own fashion, and progressively brutalised, but so long as the ‘line’ pursues a zigzag path, allowing for breathing spells as well as the terrible daily treadmill, they will, for all the suffering it brings, be able to find their lives just—if only just—sufficiently bearable to continue to exist and toil and even enjoy pleasures.’

Wu Guoguang’s ‘Stalin’s Logic’ and Isaiah Berlin’s ‘artificial dialectic’ help us better understand Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium. Furthermore, as Simon Leys observed:

‘Dialectics is the jolly art that enables the Supreme Leader never to make mistakes—for even if he did the wrong thing, he did it at the right time, which makes it right for him to have been wrong, whereas the Enemy, even if he did the right thing, did it at the wrong time, which makes it wrong for him to have been right.’]

***

Everyone in the perverted political ecosystem of China’s party-state lives with frustration. Even when they die they are still prisoners of the system that they helped perpetuate. Ultimately, everyone is a loser. If you zoom out then, think about the ‘Chained Woman’: wasn’t her fate the same as the Party’s own ‘political prisoners’?

And what about the countless victims of the Covid epidemic; to a person they too were ‘losers.’ Then there’s the case of Qin Gang 秦剛, the ousted foreign minister, a few months ago. Won’t he live out his days in teeth-gnashing frustration? In the fullness of time, moreover, it is more than possible that even Xi Jinping himself will end up a loser, imprisoned by benighted wilfulness and victim of his own myth-making. So, although the curtain suddenly fell on the personal tragedy of Li Keqiang, the ‘tragedy of Li Keqiang,’ which is itself a drama with paradigmatic significance, is far from over.

***

Source:

- 吳國光,國事光析:‘李克強悲劇’並未落幕,VOA,2023年10月27日 and 獨裁與惡政的螺旋效應:再談’斯大林邏輯’, VOA,2023年10月16日

***

You & Them

Jiang He

Translated by Geremie R. Barmé

There’s really no need

No need at all to explain his death with conspiracy theories

I can tell you for a fact that he was indeed murdered

Killed slowly and exquisitely

After all, he was an accomplice in his own endJust like him, you too are being done to death

Little by little, by them

A crime in progress dragged out over timeThey have embedded in you the means for your demise

In your mind as well as in your body

Infecting every moment with fragility, fear, insincerity and impotenceThese assassins implement their plot by

Murdering your desire, killing your ability to express yourself

Bit by bit, excruciatingly slowly

Dissolving you

Why do I say ‘them’ and not some fucking ‘one’?From the most basic place

Language — the way we communicate —

They devour our words,

Eliminate expressions deemed too ‘sensitive’

Insinuating in their place their lies

That constant stream of nonsenseJust listen to yourself: is there any truth left in you?

Genocide is occurring in China, too

Why have the young held up those blank pages? Does this country know no shame?

Those blank sheets paper our world like death shroudsSo, I say: mourn not the passing of any one person — there are too many to mourn

It’s wrong, surely, that so very many people

Chant funereal laments,

Mourn themselves,

Long before they’re even died

27 October 2023

***

Source:

- https://x.com/jianghelaoyu/status/1718579693257990610?s=46&t=Ui_QrHprvgDYWq8yYN6VWA, published on X on 29 October 2023

***

Chinese Texts:

李承鹏

他走了。

旁邊是搶救心梗成功率高達96%、曾拯救上萬病人的上海中山醫院。

你相信正國級會輸給那4%?

有人猜《可惜不是你》要下架。這幾年下架的多了,包括國際歌。

這麼理解就對了,他不是死了,而是下架了。

在一場注定失敗的角逐中。下架。

自秦以來的遊戲規則設定:首輔算個屁。

老一點的悼念過周總理,年輕的知道胡趙去世。如題,人們開始爭論、謾罵該不該悼念,一丘之貉還是尚有良心。

不爭,不重要,我們都在程序里,程序里的韭菜和礦,被操控被犧牲,心態不好的罵一句老天不公,心態好的,自以為參與了歷史。

別自作多情,你從未參與歷史,是歷史強行進入你的身體。

有死一個首輔改朝換代的先例嗎。

我當然不是虛無主義者,歷史就算沒規律,也有跡可循。崇禎十七年,六大危機:白銀,鼠疫,內亂,外敵,自己亂政,小冰河期……算算,現在佔幾條。

我也在等風來,有時候也怕,等來的是大雹子。

人心之壞,遠逾前朝。

沒有人不付出代價就換來自由,你等克強經濟等雙創等來了什麼,你盼別人上街、自己在樓上看風景,安全,實惠還不側漏……現在如何。

一個善於把控局勢自稱經濟還有救的朋友破產了,他臨終,哦不對,臨走前說了一句沒騙自己的話:這裡沒救了,不可能搞好。

一個首輔改變不了什麼,你以為是昂格魯撒克遜的撒切爾夫人呢。

張居正活了58歲,李克強活了68歲,申時行活了78歲,他們都沒改變什麼。

當你認定這個體制並成為肱骨之臣,就要接受這命運。未老,尚能泳,暴斃。

你選擇了開頭,結尾是打包買一送一。當初不是開盲盒,而是魷魚遊戲。

當然,「長江,黃河不會倒流,中國開放的大門不會關上」,會讓人覺得朝中尚有希望。

他那句「天下,其實是每個人的‘天下’,所以‘天下興亡’,才會‘匹夫有責’。」聽上去挺有人味。

沒希望,總得有點希望吧。

沒鮮花,塑料的也行。

一個數據,我國是全世界塑料花最大生產國出口國,佔世界97%。比中山醫院搶救心梗還成功。

人們最富激情的問題是:會不會有人拿著花上街紀念……

1976年周總理,1989年胡耀邦,還有趙紫陽,還有2022年白紙運動。

結論:中國的每一次變革,是寄望於死幾個人,拿著鮮花上街紀念……靜觀其變,看誰勇敢。

這是我們偉大的變革觀。懦弱的我亦在其中。

有奇跡嗎,沒有的話,來束塑料花。

被傷害的人們,一代代用自己的勇敢方式滾滾向前。

誰他媽知道這個帝國明天又死誰呢。

***

Source:

- https://x.com/dayangelcp/status/1717856446233387276?s=46&t=Ui_QrHprvgDYWq8yYN6VWA, published on X on 27 October 2023

「李克強悲劇」並未落幕

2023年10月27日

吳國光

半年多之前還是中共第二號人物的李克強在年僅68歲的時候猝然去世,輿論震驚。編輯希望我寫寫這個話題,礙難推辭,只是心中五味雜陳,不知從何說起。

一代人的悲哀

不能說沒有酸楚和悲哀。四十五年前,文革後恢復高考的第一批大學生入學,我和李克強同時進入了北京大學,他在法律系,我在中文系。那個時代的校園很活躍,我們入學之後不久就相互認識了,關係雖不密切,但也時有過從。去年夏天搬家到加州,整理舊物時,我還發現大學時代日記里記有幾筆和他的交往。那個時候他給我的印象是一位具有獨立思考能力的同學。

大學畢業之後,我們來往不多。記得最後一次見面是在1987年,我參加中共十三大籌備過程中的政治改革政策設計,某天到團中央座談如何改革群團組織,劉延東、劉奇葆出面接待,與他們同為團中央書記的李克強專門過來與我寒暄了一番。不過,那時我已經從北大同學那裡聽到了一些對他的不滿,起因在於:1986年冬天有一場全國性學潮,李克強專程到北大坐鎮,嚴令要控制住校園,決不能讓北大學生上街。為了所謂政治前途,看來李克強已經放棄原有的獨立思考能力了。

八九去國,隨後我與血腥鎮壓了學生和民眾的中共徹底決裂,再次見到李克強就是任教香港的時候從中央電視台的節目中看到了。那時他已經貴為河南省長,陪同江澤民視察的時候,完全沒有了當年校園裡的意氣風發,而是一副陪小心的官僚相,說不上奴顏婢膝,卻也看得出慎微逢迎。現在回頭來看,他的人生悲劇,那時已經漸入戲骨。

當然,不僅僅是李克強這樣做。多少當年的青春志士,後來都走上了這樣的人生道路:為了當官,為了發財,為了權勢,為了名利,不斷地扭曲自己,直到扭曲成黨國所需要、所信任、所賞識、至少是所不排斥的人材。以這樣的價值觀來看,李克強還被視為七七級一代人中最為成功的,畢竟坐上了總理寶座。曾經最有希望、也最有歷練而可能推動中國走出毛共黑暗的一代人,如果以李克強為標桿,那真正是一代人的悲哀。

共產黨制度是毀滅良知的

公平地說,即使是身為中共高官的李克強也還應該良知未泯。輿論還記得他關於中國有六億人口每月收入僅一千元人民幣的實話,網民這當口也在重復他那句「人在做天在看」的無奈之言。我記憶猶新的是,他在總理任上曾經回憶起毛時代農民出外乞討還需要黨組織開介紹信的事情,以此說明中國不能倒退到毛時代。李克強在安徽長大,並曾經在鳳陽插隊,毛時代那裡的農民每年冬天都要出外討飯,一年的收成不足以填飽一年間的肚皮。那個時代,我在家鄉魯南地區生活,冬天里常能見到這些操著皖中或蘇北口音挨家挨戶叩門乞討的人們。這是我們親身見證的歷史,而李克強沒有忘記它,這就是良知還在了。

然而,這正是李克強人生悲劇的又一體現。他應該知道,良知是與共產黨體制難以相容的。也許,他有想過,有一天當自己當上共產黨的最高領導人時,他可以改變這種體制,使之與良知相容?確實,他一度非常接近登上最高權力的位置,但決賽中輸給了習近平。問題是,習近平是靠什麼贏得那個位置呢?有人說是善於裝孫子,有人說是身為紅二代,更關鍵的是江澤民曾慶紅為了阻擊胡錦濤選擇的接班人李克強而選擇了習近平。很明顯,這一過程如何展開,本身就是中共制度所決定的。為什麼江澤民曾慶紅就比胡錦濤更有力量來決定是李還是習?還不是因為他們掌控軍隊,掌控政法,也掌控黨機器。一個掌控暴力機器就能掌控一切的制度,怎麼可能與良知相容?怎麼可能容許你去改變這種體制?

既然不相容,還要去適應,這就難免出現人格分裂——人格分裂本身就是人生悲劇。也許那裡有兩個李克強:一個李克強不斷扭曲自己以在中共體制內沿著權力等級步步攀升,一個李克強還保留了一些常識、良知和對於民眾的同情心。殊不知,後者在共產黨權力場上可以成為一個人的軟肋。當習近平和李克強在2012-13年開始了十年共事的時候,李克強黑不過習近平,壞不過習近平,因此也就必定被習近平欺侮。重復一句:這不是習近平的本事,而是共產黨制度所決定的。所謂制度,就是遊戲規則。按這套遊戲規則玩,越黑越壞就越是能贏。

活得憋屈,死得窩囊——也是斯大林邏輯的一種表現

李克強的從政生涯固然是一場悲劇,但是,誰也沒有想到,在他已經以不到官定退休年齡而提前退出領導層之後的短短七個月後,他的人生會這樣突然地落下帷幕,為悲劇再加一層!68歲,對當今的人們來說仍在盛年;中共高官保健條件那麼好,更是個個高壽如龜。李克強的死,其中有沒有什麼不可告人的手腳呢?人們可以這樣質疑,但沒有人能夠知道答案。對此,我只能說:被謀害死也好,因為多年心情壓抑、感覺窩囊而引發病情去世也好,政治人物的生活乃至生死都必定是有某些政治因素在內的。從斯大林時代怪案連連,到毛澤東當年整王明,再到周恩來不能及時開刀治癌,活得憋屈並死得窩囊的共產黨高級領導人多了去了,也都是「斯大林邏輯」的一種表現!

***

【獨裁必然帶來治理上的惡果。過去幾年中,從對於新冠肺炎的「動態清零」,到無預警放開的「疫情海嘯」,製造了巨大的人命犧牲和人道災難。反市場和敵視民營經濟的經濟政策,加劇了中國經濟增長的放緩,直接、負面地影響了上億民眾的就業、收入和消費。習近平的這些惡政與斯大林、毛澤東當年製造大飢荒的惡政是一脈相承的,因此,在災難之後進行政治整肅的權力邏輯也是一以貫之的。

這裡,可以發現在獨裁與惡政之間存在一種螺旋效應,二者相互之間推動升級。就獨裁領導人來說,越是個人集權,就越是沒有制約;決策越是任性,越是造成治理上的災難,也就是造成惡政;而越是出現治理的災難,獨裁者也就越發感到已經高度集中在自己手裡的權力還是不夠用。地位不安全,於是越發要進一步強化個人權威,進一步實行政治清洗,進一步壓制乃至消滅可能的不滿,首先是出現在精英階層的不滿。共產黨的整個權力體系作為獨裁體制,恰恰為這種個人集權和政治清洗提供了足夠的、強大的制度手段,也由於不向民眾負責而必然走向惡政。因為獨裁而形成惡政,因為惡政而愈發獨裁,這才是深層的「斯大林邏輯」。

— 摘自吳國光,獨裁與惡政的螺旋效應:再談「斯大林邏輯」, 美國之音, 2023年10曰16日】

***

可是,在共產黨制度下,誰又不是活得憋屈、死得窩囊呢!想一想「鐵鍊女」,那活得豈止是憋屈?想一想新冠疫情中的千萬逝者,那死得豈止是窩囊!或者說,前幾個月還志得意滿的秦剛,現在難道就活得不憋屈嗎?若干年後的習近平,誰又敢說他會死得不窩囊呢?因此說,儘管李克強的人生悲劇已經嘎然謝幕,但「李克強悲劇」遠未落幕。

***

Source:

- 吳國光,國事光析:‘李克強悲劇’並未落幕,VOA,2023年10月27日 and 獨裁與惡政的螺旋效應:再談’斯大林邏輯’, VOA,2023年10月16日

你和他們

江河

不必了。不必為這個人的死

揣摩什麼陰謀論

我告訴你,他是被殺死的

被慢慢地,一點一點殺死的

他也曾不斷地充當殺自己的幫凶

你,也一樣,你的生命

被他們一點一點地,慢慢殺著

這場罪行經久不斷地進行

在你的脆弱,恐懼,言不由衷,無力感中

何止在你的頭腦,在你全部的身體中

他們安插進讓你自毀的工具

他們殺你的想法,殺你的慾望,殺你的表達

一點一點,慢慢地,慢慢地,一點一點地

溶解著你

為什麼我說他們,而不僅僅是他媽的一個人

連你都被拉進他們的同伙

從最根本的地方開始

從語言,從話語

他們大規模地以敏感詞為緣由

吞噬掉通常的話語,日常的語言

聽聽他們的謊言,空洞的沒有盡頭的胡言亂語

聽聽你自己,還在說真話嗎

民族文化的滅絕,在中國發生

為什麼年輕人舉著白紙,羞恥吧這個國家

白紙無數的白紙像屍布鋪天蓋地

不必了,不必再哀悼哪個人

該哀悼的人太多了

總不能讓這麼多人

活著的時候

為自己的生命唱葬歌

2023年10月27日

***

Source:

- https://x.com/jianghelaoyu/status/1718579693257990610?s=46&t=Ui_QrHprvgDYWq8yYN6VWA, published on X on 29 October 2023

***