Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium

真偽莫辨

May Fourth 2024 marks the 105th anniversary of student protests in Beijing that have had a profound impact both on the political and cultural life of modern China. Previously, China Heritage commemorated the centenary of the May Fourth protests with a pair of essays:

- Mangling May Fourth 2020 in Beijing, 8 May 2020

- Mangling May Fourth 2020 in Washington, 14 May 2020

In 2024, we mark the anniversary of May Fourth, China’s Youth Festival 青年節, with three interconnected works:

- May Fourth at 105 — Protest, Resistance, Repression, 1 May 2024;

- Captive Minds & Academic Angst on May Fourth 2024 (the present essay); and,

- Buddha Youth, Protecting the Heart & Learning in War-Time.

As we observed in May Fourth at 105:

Long ago, ‘The Spirit of May Fourth’ 五四精神 — one that supposedly reflects the idealism as well as the avowed quest for rationality and democracy of the student demonstrators of 1919 — was interpreted and reinterpreted by the Communist Party to serve its shifting purposes. For decades the Party has made a mockery of an idealistic movement that played a crucial role in its founding in 1921 and it continues to benefit from a cynical successful manipulation of student enthusiasm and patriotic outrage. Since 1949, the Party has embodied a dissembling version of the cultural conservatism and political obscurantism against which the students demonstrated on 4 May 1919.

The charade continues and establishment intellectuals in the People’s Republic, as well as those unwitting collaborators and the majority with a healthy instinct for self-preservation, go along with the farrago.

Below, we recall Xi Jinping’s commemoration of May Fourth at Peking University in 2014, followed by a short historical overview of the origins of the ‘captive minds’ of contemporary China. We then turn to the anxieties of scholars today who find themselves caught between the demands of global academia and the Chinese party-state. In doing so we draw once more on the work of Center for China and Globalization (CCG), a Beijing think tank that addresses international observers from the nooks and crannies of China’s Velvet Prison.

***

Contents

(click on a section title to scroll down)

- Yan’an: Two Conversations that Adumbrated a Dark Future

- May Fourth 2014, 2024

- Back at the Beginning

- Two Universities

- Ever-present Threats to Wissenschaftsfreiheit

- Captive Minds: Plurality without Pluralism

- Yan Xuetong’s Angst

- Conflicted Loyalties—professional and partisan

- Yang Xingfo Warns the Twenty-first Century

- Postscript: ‘He maintains his course to death without changing’

***

The leitmotiv of this chapter is 偽 wěi, — counterfeit, forgery, an imitation, replica, fake, pseudo — and our rubric, the expression 真偽莫辨 zhēn wěi mò biàn — comes from a line in the The History of Sui 隋書:

All manner of strategic alliance was forged during the Warring States, making it impossible to discern true from false. The jostling claims of thinkers also created confusion and chaos.

戰國縱橫,真偽莫辨,

諸子之言,紛然淆亂。

This chapter in Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium is also included in our series Watching China Watching. As ever, our thanks to Reaader #1 for painstakingly reviewing the draft of this rambling essay.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

8 May 2024

***

Related Material

- 陳徒手,故國人民有所思:1949年後知識分子思想改造側影,北京:生活·讀書·新知三聯書店,2013

- Robert Bosch, Whispering advice, roaring praises: The role of Chinese think tanks under Xi Jinping, Merics, 8 May 2024

- Czesław Miłosz, The Captive Mind (1953), New York: Knopf, 1991

- Robert Jay Lifton, Thought Reform and the Psychology of Totalism: A Study of “Brainwashing” in China, New York: Norton, 1961. Reprinted with a new preface: University of North Carolina Press, 1989 (online at Internet Archive)

- May Fourth at Ninety-nine, 4 May 2018

- Anniversaries New & Old in 2019 — Remembering 5.4, Accounting for 4.28, 4 May 2019

- Xu Zhangrun, A Letter to My Editors, and China’s Censors, ChinaFile, 18 May 2021

- Xu Zhangrun, A Farewell to my Students, ChinaFile, 9 September 2021

Homo Xinensis

- Deathwatch for a Chairman, 17 July 2018

- Ruling The Rivers & Mountains, 8 August 2018

- The Party Empire, 17 August 2018

- Homo Xinensis, 31 August 2018

- Homo Xinensis Ascendant, 16 September 2018

- Homo Xinensis Militant, 1 October 2018

Yan’an: Two Conversations that

Adumbrated the Demise of the May Fourth Spirit

In The Lugubrious Merry-go-round of Chinese Politics, we noted that On the Road: A Century of Marxism 世紀行, a TV mini-series released by the Communist Party’s Propaganda Department in 1990 to counter the influence of the popular 1988 television documentary River Elegy 河殤, introduced Chinese audiences to an exchange that Mao Zedong had with the educator and progressive political activist Huang Yanpei (黃炎培, 1878-1965) at Yan’an in 1945.

Mao Zedong had asked Huang Yanpei what he had made of his visit to the wartime Communist base. Prefacing his response with praise for the collective, hard-working spirit evident among the Communists and their supporters, Huang said that he had his doubts about whether their wartime frugality and solidarity could last. He predicted that the revolutionary ardour of the Communists could well wane if they ended up in control of China, and wondered out loud whether the endemic political limitations and blemishes of earlier Chinese regimes would return to haunt the new one, despite the best efforts of its committed idealists.

Would autocracy, cavalier political behaviour, nepotism and corruption once more come to rule over China? Huang said he could see no way out of the ‘vicious cycle’ of dynastic rise and collapse, though he certainly hoped that Mao and his followers would be able to break free of the wheel of history. Mao responded unequivocally:

We have found a new path; we can break free of the cycle. The path is called democracy. As long as the people have oversight of the government then government will not slacken in its efforts. When everyone takes responsibility there will be no danger that things will return to how they were even if the leader has gone.

In December 2012, shortly after becoming Party General Secretary, Xi Jinping first referred to what was now called the Mao-Huang ‘cave reply’ 窯洞對 yáodòng duì himself, and it has been a feature of his remarks on Chinese history, democracy, corruption and China’s future ever since.

***

***

Fu Sinian (傅斯年, 1896-1950) was another member of the delegation of independent scholars and political activists that visited Yan’an in the summer of 1945. Fu was a noted May Fourth-era activist and a leading historian. He had been a student leader during the 4 May 1919 demonstrations, and was already an established cultural figure when he first encountered Mao who was a lowly library assistant at Peking University.

The Communist leader had spoken with chagrin about the fact that famous young academic stars like Fu had no time for country bumpkin like himself, although when they met in Yan’an, Mao made no mention of his long-harboured grievance. Instead, during the course of a private conversation on 4 July, Mao praised Fu for his intellectual contributions to the anti-feudal push of the May Fourth era, which itself helped engender the creation of the Communist Party. With suitable modesty Fu responded that his generation of agitators were like the upstarts Chen Sheng 陳勝 and Wu Guang 吳廣 who had rebelled against the tyranny of the Qin dynasty (second century BCE); it was Mao and his colleagues who were the real heroes, like Liu Bang 劉邦 and Xiang Yu 項羽. After all, Liu Bang went on to become the founding emperor of the Han, one of the greatest dynasties in Chinese history. It was a tactful response, one that flattered the Communist leader while preserving Fu’s own sense of dignity. It was an exchange also well suited to Yan’an, which was in the heartland of the area that formed the core of the Qin empire over two millennia earlier.

As was common practice among men of letters at the time, Fu asked Mao for a piece of calligraphy as a memento of their encounter. The following day he received a hand-written copy of ‘The Pit of Burned Books’ 焚書坑 by the late-Tang poet Zhang Jie 章碣 (eighth century). In the accompanying note Mao remarked, ‘I fear you were being too self-effacing when you spoke of Chen Sheng and Wu Guang… . I’ve copied out a poem by a Tang writer to expand [on our discussion]’. The poem spoke of the vain attempt by Qin Shihuang, the First Emperor of the Qin, to quell opposition to his draconian rule by burning books and burying scholars. The last lines read,

The ashes in the pit not yet cold, rebellion rose in the east,

Liu Bang and Xiang Yu were hardly men of letters.

坑灰未冷山東亂

劉項原來不讀書

(In full the poem reads: 竹帛煙銷帝業虛, 關河空鎖祖龍居。坑灰未冷山東亂, 劉項原來不讀書。)

It was Mao’s way of chiding a man who had been at the intellectual forefront for many years. In effect, he was saying that Fu Sinian’s rebellion against the feudal traditions of China was indeed vainglorious, more so than the failed uprising of the peasant rebels Chen Sheng and Wu Guang against the Qin. And besides real heroes like Liu Bang and Xiang Yu were men of action and had no care for book learning — to Mao the fatal flaw of so many May Fourth era intellectual activists. Mao’s false modesty in claiming that he and his cohort were, like Liu and Xiang, unlettered rebels, also betrayed a confidence that he would lead the Communist army to victory over the existing political order. It was a theme to which he would return many times.

— from For Truly Great Men, Look to This Age Alone — Watching China Watching (XII), 27 January 2018

***

The Song and Dance about Democracy and Freedom

多、少,有、無

Chu Anping 儲安平

The Communist Party is presently making a big song and dance about “democracy.” But if we consider the basic spirit of the Communists, we must realize that they are antidemocratic. In terms of the spirit in which they rule, there is no difference between them and the fascists. Both aim at using a strong organization to control people’s thinking. The Communists are undoubtedly chanting “democracy” today in order to unite people to oppose the political monopoly of the Nationalists. But their real aim is their own political monopoly, not democracy. There is a prerequisite in the discussion of democracy, one that cannot be compromised: People must be allowed intellectual freedom. Only when they have such freedom, when they can freely express their ideas, will the spirit of democracy be realized. If only those who believe in Communism are allowed this freedom, there will be no [real] intellectual freedom or freedom of speech… . To be quite frank, our present struggle for freedom under Nationalist rule is really a matter of increasing the degree of our freedom. If the Communists were in power, the question would be whether we would have any freedom at all.

老實說,我們現在爭取自由,在國民黨統治下,這個“自由”還是一個“多”“少”的問題,假如共產黨執政了,這個“自由”就變成了一個“有”“無”的問題了。

— Chu Anping, 8 March 1947, trans. in New Ghosts, Old Dreams, 1992, pp.359-260

In Drop Your Pants!, our five-part series on the Communist Party’s 2018 patriotic education campaign, we discussed the creation in the 1920s of the Chinese party-state 黨國 dǎng guó, a Nationalist-era term revived in recent years to describe the People’s Republic. We also introduced the journalist Chu Anping’s observations on Party Empire 黨天下 dǎng tiānxià, a word he used to describe the Party’s totalitarian style and one that re-entered China’s political vocabulary as a result of the investigative historian Dai Qing’s study of Chu, and China’s suppressed liberal political traditions, in 1989.

Chu Anping disappeared during ‘Red August’ in 1966 at the beginning of the Cultural Revolution. His body was never found.

***

May Fourth 2014, 2024

Eighteen months into his tenure as head of China’s party-state-army Xi Jinping visited Peking University in northwest Beijing. Although ostensibly there to commemorate the 95th anniversary of May Fourth, the visit signalled the reassertion of Communist domination over China’s intellectual life. ‘The values of young people determine the values that underpin the future of society itself’, Xi told a select audience:

Youth is a time when your values are undergoing change and maturation and so it is crucial to control this phase in a person’s development. It’s a process that is akin to buttoning up your clothes: if you get the first buttonhole wrong then all your buttons will be in the wrong order. Life, as in buttoning up your clothes, is all about orderly progression. (From 習近平北大行勉勵學生「人生就像扣扣子」引熱議, 5 May 2014, my translation.)

The Chairman of Everything also declared that, by 2018, Peking University would be an institution of international standing that was firmly grounded in China, one that served faithfully the needs of the Communist Party. The aim of reorienting PKU was not to create ‘a second Harvard or Cambridge’, but rather to make ‘Peking University the preeminent university’ in the world.

This ambition, like so many other grandiose plans of the Xi Jinping era, aimed for the seemingly impossible, something encapsulated in the mocking Chinese formula 既要 jì yà0 … 又要 yòu yào, ‘to want this, while also having that’. We require ideological fealty and academic creativity and excellence. It is a contemporary version of Mao Zedong’s demand that Chinese academics and researchers had to be both Red, that is, politically reliable, and Expert, or professionally outstanding, summed up in the dictum 又紅又專 yòu hóng yòu zhuān.

[Note: In Canberra, Australia, I was joined by colleagues at the research centre that I had established to mark 4 May 2014, which also happened to be my sixtieth birthday, with a series of events. See 1-5 May 2014: A Building, Two Films, an Exhibition, Two Lectures, a Podcast and Two Performances, The China Story, 13 May 2014.]

***

Celebrating the Spirit of Militant Youth on 4 May 2024

The following excerpt is taken from Brilliant Youth — a TV special marking the 2024 May Fourth Youth Festival, broadcast by CCTV on 4 May 2024. The title of this part of the show is:

The Chinese Navy has set course to become a blue-water force! The officers and servicemen of the Shandong enthusiastically contribute their all to the martial might of the mothership!

中國海軍走向深藍!山東艦官兵為航母戰鬥力不斷躍升貢獻力量!

***

[Note: For more on how the Communist Party inculcates militant youth in the ‘May Fourth Spirit’, see also, Homo Xinensis Militant, China Heritage, 1 October 2018.]

***

Back at the Beginning

At the height of the Beijing summer in mid 1951, Liu Shaoqi, a Party leader who had played a key role in helping Mao forge ideological unity during the Yan’an Rectification Campaign of 1942-1943, commissioned Hu Qiaomu 胡喬木 to write a history of the Chinese Communist Party as a guide for the country that it now dominated.

Official anecdote holds that over seven days Hu — the man who we will recall had first called on Yan’an cadres to ‘drop their pants, cut off their tails and take a wash’ — drafted Thirty Years of the Chinese Communist Party 中國共產黨的三十年 while sitting in a bathtub to keep cool. (Hu’s draft was extensively revised by Liu Shaoqi and others. At the same time a plan was made for Hu’s fellow ideologue Deng Liqun 鄧力群 to draft an updated version of Liu’s crucially important 1939 speech The Cultivated Communist 論共產黨員的修養).

On 29 September 1951, Zhou Enlai, the recently appointed premier and foreign minister of the People’s Republic, addressed academics and administrators from Peking University and other tertiary institutions on the question of the need for China’s intelligentsia to subject itself to Thought Re-moulding. In his speech, Zhou used Hu Qiaomu’s text as a key reference. Zhou’s speech would inaugurate a nationwide process of what was known as ‘washing in public’ 洗澡 (for more on this, see Ruling The Rivers & Mountains).

Simon Leys once described Zhou, whom he met as part of a Belgian student delegation in 1955, as a man with ‘a talent for telling blatant lies with angelic suavity’. During the 1940s, he was the public face of the Communist Party’s United Front strategy. An apparatchik extraordinaire Zhou had a history of bloody betrayal and brilliant survival; he was also the Party’s human face when it came to dealing with the country’s educated men and women. Drawing on thirty years of subordinating his will to the needs of the Party, in his September 1951 speech Zhou told the country’s intellectuals how they could remould their thinking. It was a life-long process, he said, one that began by differentiating between friends 朋友 and enemies 敵人. Those who had been studying the Chairman’s works would have recognised the famous opening lines of Mao’s December 1925 Analysis of Classes in Chinese Society:

Who are our enemies? Who are our friends? This is a question of the first importance for the revolution. The basic reason why all previous revolutionary struggles in China achieved so little was their failure to unite with real friends in order to attack real enemies. 誰是我們的敵人?誰是我們的朋友?這個問題是革命的首要問題。中國過去一切革命鬥爭成效甚少,其基本原因就是因為不能團結真正的朋友,以攻擊真正的敵人。

Zhou went on to say that distinguishing friend from enemy involved, in the first instance, an adjustment of one’s political stance 立場 and social attitudes 態度 to make them accord with the policies of the party-state. Naïve patriotic sentiment must be transmogrified into support for the People and unity with the Proletariat, of which the Communist Party was the enlightened vanguard, as well as being the instrument of History. Thought Reform would be experienced as a rebirth 脱胎换骨, something akin to ‘washing the heart and a stripping skin off the face’ 洗心革面. The process would allow the country’s wayward intellectuals to achieve renewal by correcting the errors of their ways 改過自新.

In response to Zhou’s seemingly heartfelt speech, a group of academic leaders who were already carefully studying Party dogma in an effort to adjust to the new regime, now petitioned the government to re-educate them en masse. Starting with Peking University and Tsinghua University a movement to ‘Wash in Public’ would be launched. Over the following months, it involved every academic, university administrator, publisher and teacher in the country. It was a lengthy, painful and, for some, deadly experience. The essential repertoire of that movement, described briefly in Ruling The Rivers & Mountains, would be refined and applied time and again during the political movements that have been a feature of life in the People’s Republic.

We should recall that the 1951 Thought Remoulding-Patriotic Education movement was launched at a time of relative national elation: years of war had come to an end; the economy was stable; and there was a government of unity. What urban dwellers generally did not realise was that the nationwide rural reform that was taking place involved pitiless class struggle and mass murder. Few people outside the Party itself appreciated what had happened during the Rectification and subsequent Salvation movements in Yan’an from 1942 to 1944: how merciless, bloody and murderous they had been. In fact, the details would only come to light with the work of Gao Hua 高華 many decades later. They understood the patriotic agenda the Communists proclaimed for China well enough, but they did not appreciate the radical plans that the Party had in store.

In essence, people were required to confess to their ‘two-faced’ nature and to commit to transforming themselves as they endeavoured to forge a unity with the party-state and its ever-changing demands. In the case of the 1951-1952 campaign, academics were required to admit to and then disavow their allegiance to the old order, to academic independence, to free thought, to the Nationalist government’s education system, to the pro-American and Western orientation of teaching, research and publishing in China over the previous half a century. They were to denounce their innate slavishness to Western imperialism, its ideas and its values. Through acts of public confession, criticisms by their colleagues and by means of an ideological rebirth after making a pledge of fealty to the Communist Party they would renounce a two-faced stance that had previously let them get away with pretend patriotism despite the fact that they clung to the spiritual coat-tails of the West.

The Party’s attacks on ‘two-faced people’ 兩面派/ 兩面人 would continue, and unswerving loyalty to the Party, regardless of how contradictory or absurd its policy twists and turns might be, would remain as the cornerstone of repeated patriotic reeducation campaigns. The level of alarm was raised in 1959 when the United States announced its policy to undermine socialist countries in the Soviet Bloc by means of Peaceful Evolution 和平演變, that is the promotion of Western ideas, cultural forms, democratic ideals and through support for dissidents. The spectre of Peaceful Evolution haunts Xi Jinping’s government still and it responded from 2015 with a range of bans in universities on teaching and even reading about certain corrosive Western ideas (for more on this, see the Chronology below).

It was also Party loyalty that underpinned the early 1960s demand that academics, scientists and professionals of all kinds be ‘Red & Expert’ 又紅又專, that is, first and foremost they must study and internalise the Party ideology to become ‘Red’, while constantly striving to excel in their particular fields of knowledge, that is to be ‘Expert’. The concept of ‘Red & Expert’ also featured in the 2018 ‘Offensive to Promote the Spirit of Patriotic Struggle [that requires intellectuals to] Contribute Positively to Building the Enterprise in the New Epoch [of the Party-State and China]’ 弘揚愛國奮鬥精神、建功立業新時代活動, and has been central to the academic balancing act of the Xi Jinping era.

***

Two Universities 梁效

During his 4 May 2014 visit to Peking University, Xi Jinping paid a courtesy call on an agèd academic by the name of Tang Yijie (湯一介, 1927-2014). Media reports gushed about the intimate exchange between Party boss and a scholar renowned for his work on an official ‘Confucian Canon’ 儒藏, a project inaugurated in 2003 boasting a state grant of 1.5 billion RMB. With an end date in 2025, the new Confucian Canon would amass a vast corpus of works related to Confucianism in imitation of the pre-Communist scriptural canons of Taoism 道藏 and Buddhism 大藏经. In June 2010, Peking University had also established a Confucian Academy 北京大學儒學研究院 with Tang Yijie as its inaugural director.

Tang Yijie was a model academic for the unfolding Xi Epoch. He was both the embodiment of academic achievement— in-depth research into State Confucianism (something that Liu Shaoqi had featured in his 1937 speech The Cultivated Communist) — and unwavering loyalty to the Party.

For aficionados of Chinese cultural politics, the encounter between Xi Jinping and Tang, who died only a few months later, was heavy in irony. Sixty five years earlier, Tang had joined the Communist Party shortly after it set up a Party committee at the university. That same year his father, the noted philosopher Tang Yongtong (湯用彤, 1893-1964), who had been acting president of PKU following the flight to Taiwan of its former head, the famed liberal intellectual Hu Shi (胡適, 1891-1962), had lent his voice to an appeal by a group of leading academic administrators to Mao and Zhou requesting the re-education of the university’s faculty mentioned above. Up until that point, Tang Yongtong had been a respected historian known, along with Wu Mi 吳宓 and Chen Yinque 陳寅恪 as one of the Three Outstanding (Chinese graduated) Talents of Harvard University 哈佛三傑.

In 1954, following a veritable storm of other ideological campaigns and political purges, Hu Shi was made the object of a devastating nationwide attack, one that again started at Peking University. This time the denunciations, criticisms and confessions were aimed at ridding China of the influence of this cultural giant and May Fourth hero once and for all. Devastated by the scale and fury of the vitriol aimed in absentia at his old friend, Tang Yongtong suffered a stroke. He never fully recovered. In his last years, his son, a young philosophy student and devoted Party member by the name of Tang Yijie, cared for the ailing scholar while acting as his amanuensis and occasional ghost writer.

***

I encountered Tang Yijie at PKU shortly after Mao’s death. He was in political purdah for his role in the Mao-Gang of Four writing group known as Liang Xiao 梁效, a homonym for Liangxiao 兩校, or ‘the two schools’, that is Peking and Tsinghua universities. Formed in late 1973 and led by the Party Secretaries of the two universities and representatives of Unit 8341, Mao’s personal pretorian guard, the Liang Xiao writing collective involved dozens of academics who undertook research and writing projects aimed at adding a scholastic veneer to the Party’s factional infighting. As a Party loyalist, Tang had no choice but to follow orders. During its three-year collective career, Liang Xiao published some two hundred pseudo-academic essays in major Party newspapers and journals that were tailored to the dizzying dialectical shifts of the day. Liang Xiao’s work was deemed to be of such intellectual heft and political value that it was required reading at universities throughout the country. I read Liang Xiao as a student in my late-Maoist university days, and would soon hear about Tang Yijie and his colleagues by reputation.

A few titles from Liang Xiao’s oeuvre reflect the style and content of their tortuous polemics: ‘The Truth about Kong Qiu [the vulgar name for Confucius]’ 孔丘其人, ‘Research on the Historical Experience of the Confucian-Legalist Two-line Struggle’ 研究儒法鬥爭的歷史經驗, ‘Wu Zetian: a political talent’ 有作為的女政治家武則天, ‘The Direction of the Revolution in Education Must Not be Corrupted’ 教育革命的方向不容篡改, ‘Repulse the Rightist Tendency to Overturn Correct Verdicts’ 回擊右傾翻案風 and ‘A Critique of Deng Xiaoping’s Compradore Capitalist Economic Thinking’ 評鄧小平的買辦資產階級經濟思想.

***

After a face-saving period of criticism, reflection and self-renewal required following the death of Mao and the purge of the Gang of Four in late 1976, many writers involved in Liang Xiao would achieve fame and respectability. Tang Yijie was one of their number. By the time the refashioned Confucian luminary met Xi Jinping in May 2014 he was what is known in the trade as a ‘Practiced Political Athlete’ 老運動員, a term that is a play on the words ‘political purge’ 運動 and ‘athlete’ 運動員.

Although from the 1980s Tang became an acknowledged expert in Confucianism, he was hardly a dàrú 大儒, or Great Scholar of Principle, of the kind praised by the Tsinghua University professor of law Xu Zhangrun 許章潤. For Xu the term rú 儒, often clumsily translated as ‘Confucian’, means ‘a man whose learning and actions are grounded in Confucian principles of righteousness, fearlessness and probity’ (for more on this and Xu Zhangrun, see Imminent Fears, Immediate Hopes — A Beijing Jeremiad, China Heritage, 1 August 2018). In contrast, ‘New Confucian Academics’ 新儒家學者 are little better than intellectual merchants.

By the time Xi Jinping met him in May 2014, Tang Yijie would have been aware of the deadening restrictions on academic freedom of a kind that was reminiscent of the late-Cultural Revolution era when Liang Xiao had been active. Tang’s wife, the internationally noted comparative literature expert Yue Daiyun (樂黛雲, 1931-), would also appreciate what the new clampdown meant. Protected by fame and advanced age — other cases have shown that the Party apparat shies away from the overt persecution of its celebrated members — they nonetheless chose silence. It is for this reason that in China Heritage we commemorate the clear-thinking and plain-speaking of outstanding members of their generation like Wu Zuguang 吳祖光 and Yang Xianyi 楊憲益, as well as paying homage to the bravery of younger scholars like Liu Xiaobo 劉曉波, while noting the valour of active academics like Xu Zhangrun and the agonies of writers like Xu Zhiyuan 許知遠. There are those who could speak out in defense of independent thought and academic freedom, things that were crucial to them as they have built up their own reputations. They choose to do otherwise. Having long ago disavowed the political caprice and cruelty of the Maoist era, now that Xi Jinping’s New Epoch ushers in a Silent China, it is noteworthy that many who could well voice their opposition with little fear of retribution take the well-trodden path of complicity.

In many ways, Tang Yijie was a New Socialist Person; he was both Red and Expert; he had done the Party’s bidding, often to his own detriment, since joining its ranks in 1949. Homo Xinensis, the New Person of the Xi Jinping Epoch inherits the genes of the New Socialist Person, as well as the DNA of its noteworthy subspecies, Homosos, which is subject of our study Homo Xinensis Ascendant.

Tang Yijie passed away peacefully on 9 September 2014, thirty years to the day after Mao’s demise in 1976, and a little over four months after he met Chairman Xi.

— this above material draws on Homo Xinensis, part three of a five-part study of the early Xi Jinping era published by China Heritage in August 2018

Ever-present Threats to Wissenschaftsfreiheit

Freedom of opinion is nothing more than to speak the truth plainly, to search for truth … One is not deceived by the ancients or cowed by those in authority. It is to accept facts as facts even if they proceed from an enemy, and falsehoods as errors even if they proceed from one’s lord or father.

須知言論自繇,只是平實地說實話求真理,一不為古人所欺、二不為權勢所屈而已。使理真事實,雖出之仇敵,不可廢也。使理謬事誣,雖以君父,不可從也。此之謂自繇。

— from Yan Fu 嚴復 ‘Translator’s Direction to the Reader’ 譯凡例 in his translation of John Stuart Mill, On Liberty, published in 1903, quoted in Benjamin I. Schwartz, In Search of Wealth and Power: Yen Fu and the West, 1964, pp.131-132

***

Academic Freedom Under Fire

Louis Menand

The right at stake in these events [that is, the student protests in America from October 2023] is that of academic freedom, a right that derives from the role the university plays in American life. Professors don’t work for politicians, they don’t work for trustees, and they don’t work for themselves. They work for the public. Their job is to produce scholarship and instruction that add to society’s store of knowledge. They commit themselves to doing this disinterestedly: that is, without regard to financial, partisan, or personal advantage. In exchange, society allows them to insulate themselves—and to some extent their students—against external interference in their affairs. It builds them a tower.

The concept originated in Germany—the German term is Lehrfreiheit, freedom to teach—and it was imported here in the late nineteenth century, along with the model, also German, of the research university, an educational institution in which the faculty produce scholarship and research. Since that time, it has been understood that academic freedom is the defining feature of the modern research university.

In nineteenth-century Germany, where universities were run by the government, academic freedom was a right against the state. It was needed because there was no First Amendment-style right to free speech. Lehrfreiheit protected what professors wrote and taught inside (although not outside) the academy. In the United States, where, after the Civil War, many research universities were built with private money—Chicago, Cornell, Hopkins, Stanford—the right was extended to protect professors from being fired for their views, whether expressed in the classroom or in the public square. The key event was the founding, in 1915, of the American Association of University Professors, which is, among other things, an academic-freedom watchdog.

Academic freedom is related to, but not the same as, freedom of speech in the First Amendment sense. In the public square, you can say or publish ignorant things, hateful things, in many cases false things, and the state cannot touch you. Academic freedom doesn’t work that way. Academic discourse is rigorously policed. It’s just that the police are professors.

Faculty members pass judgment on the work that their colleagues produce, and they decide whom to hire, whom to fire, and what to teach. They see that the norms of academic inquiry are observed. Those norms derive from the first great battle over academic freedom in the nineteenth century—science versus religion. The model of inquiry in the modern research university is secular and scientific. All views and all hypotheses must be fairly tested, and their success depends entirely on their ability to persuade by evidence and by rational argument. No a-priori judgments are permitted, and there is no appeal to a higher authority.

— from Louis Menand, Academic Freedom Under Fire, The New Yorker, 6 May 2024

Captive Minds: Plurality without Pluralism

Ketman brings comfort, fostering dreams of what might be, and even the enclosing fence affords the solace of reverie.

— Czesław Miłosz

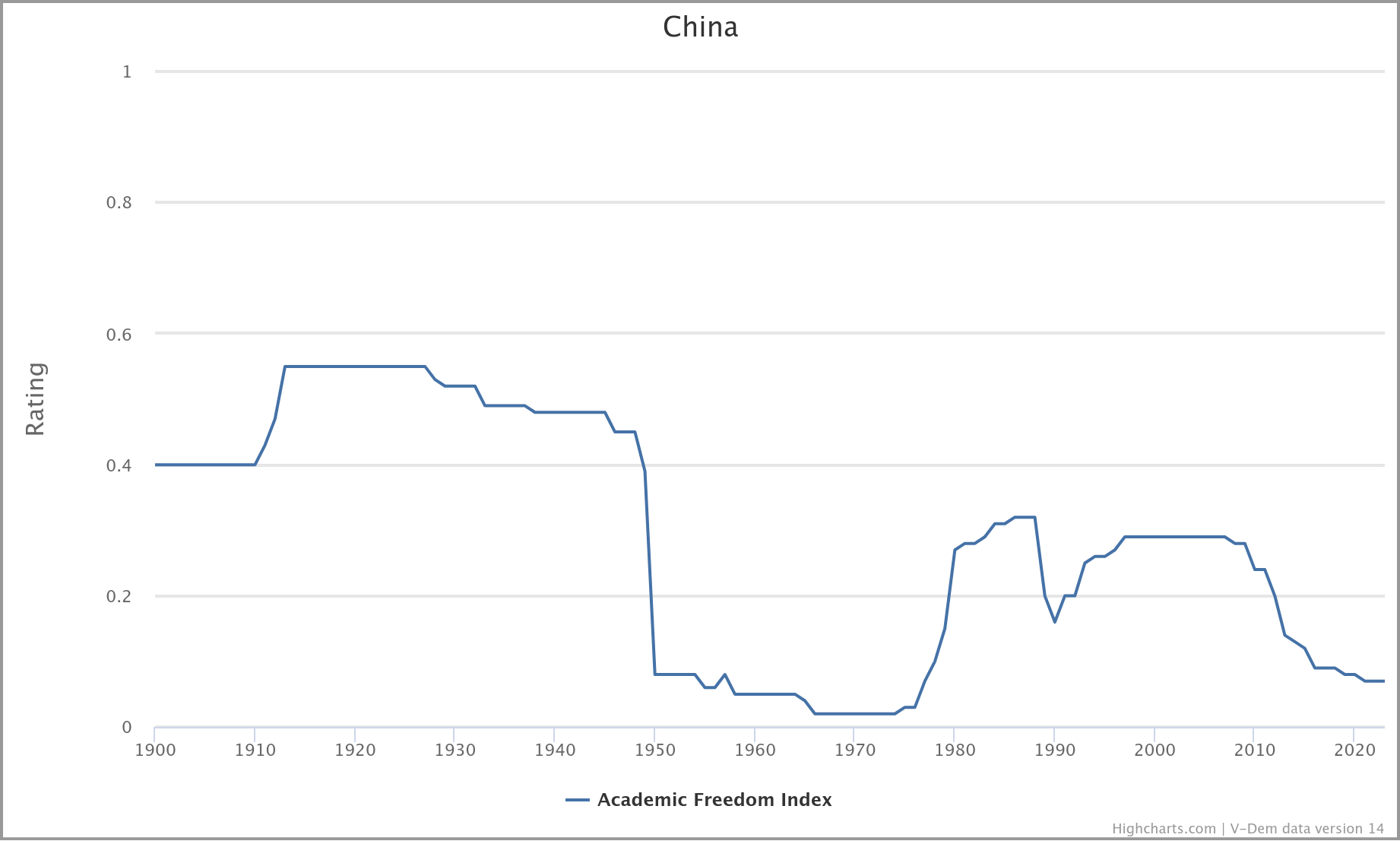

The Academic Freedom Index (AFI) assesses de facto levels of academic freedom across the world based on five indicators: freedom to research and teach; freedom of academic exchange and dissemination; institutional autonomy; campus integrity; and freedom of academic and cultural expression. The AFI currently covers 179 countries and territories, and provides the most comprehensive dataset on the subject of academic freedom.

***

***

The expression ‘captive mind’ in the title of this essay refers to The Captive Mind, a study of the allure of totalising authoritarianism and thought control written by Czesław Miłosz in 1951. A Chinese version of the book, translated by Stephen Soong 宋淇 under the title 攻心記, was published in Hong Kong in 1956.

As Tony Judt remarked The Captive Mind:

… is most memorable for two images. One is the “Pill of Murti-Bing.” Miłosz came across this in an obscure novel by Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz, Insatiability (1927). In this story, Central Europeans facing the prospect of being overrun by unidentified Asiatic hordes pop a little pill, which relieves them of fear and anxiety; buoyed by its effects, they not only accept their new rulers but are positively happy to receive them.

The second image is that of “Ketman,” borrowed from Arthur de Gobineau’s Religions and Philosophies of Central Asia, in which the French traveler reports the Persian phenomenon of elective identities. Those who have internalized the way of being called “Ketman” can live with the contradictions of saying one thing and believing another, adapting freely to each new requirement of their rulers while believing that they have preserved somewhere within themselves the autonomy of a free thinker—or at any rate a thinker who has freely chosen to subordinate himself to the ideas and dictates of others.

Ketman, in Miłosz’s words, “brings comfort, fostering dreams of what might be, and even the enclosing fence affords the solace of reverie.” Writing for the desk drawer becomes a sign of inner liberty. At least his audience would take him seriously if only they could read him:

Fear of the indifference with which the economic system of the West treats its artists and scholars is widespread among Eastern intellectuals. They say it is better to deal with an intelligent devil than with a good-natured idiot.

Between Ketman and the Pill of Murti-Bing, Miłosz brilliantly dissects the state of mind of the fellow traveler, the deluded idealist, and the cynical time server. His essay is more subtle than Arthur Koestler’s Darkness at Noon and less relentlessly logical than Raymond Aron’s Opium of the Intellectuals.

— Tony Judt, Captive Minds, Then and Now, New York Review of Books, 13 July 2010

***

The 4th of May 2024 marked the 105th anniversary of the May Fourth demonstrations in Beijing. It also happened to be my seventieth birthday and twenty-five years to the day since the release of my book In the Red: on contemporary Chinese culture. Published by Columbia University Press, In the Red was launched by Andrew J. Nathan at the SoHo salon of the fashion designer Vivienne Tam in Manhattan on the night of 4 May 1999. In the introduction to the book I wrote that:

I am interested in what happens in the culture as it develops within its own structures of power and symbolic universe; how the impact, affirmation, and multifaceted exploitation of the outside world is used in the creation of cultural status both in China and overseas; and how global cultural norms suffuse a system that is all the while rejecting and adapting them. I also make forays into issues such as how superficially determined power relationships (between, say, the state and independent artists) are described internally for a local Chinese audience and then depicted for consumption (that is, packaged and exported), initially in the broader realm of Chinese-language culture (including Hong Kong, Taiwan, and the overseas Chinese press) and then internationally.

One of my central interests is the investigation of how, under the party’s aegis, comrades have become consumers without necessarily also developing into citizens.

— Introduction: a Culture in the Red, pp.xiii-xiv

Although the focus of In the Red was on contemporary Chinese culture, many of the observations made in it related equally to the intelligentsia and the Chinese academy. As we consider the complex skein of relationships between China’s power-holders, academics, propagandists and international scholars today, those observations are still salient:

The term nonofficial culture covers a complex skein of interrelated phenomena. Depending on the angle from which it is observed, or the point at which it impinges on the observer, nonofficial culture can also be spoken of as a parallel or even parasite culture. As such, it is neither nonofficial nor necessarily antiofficial. Much of it was and still is produced with state funding and certain (often low-level) official or state involvement. It may not be directly sanctioned or beholden to the overculture, and it cannot simply be classified as oppositional. Whereas the term nonofficial culture has becoming increasingly modish outside the mainland since 1989 to describe the works—film, art, theater, literature—produced in this cultural demi-monde as antiofficial, dissident, or underground, in the 1990s when commercial culture came to reign even on the mainland, the term nonmainstream or underculture was more appropriate. There is, however, no adequate nomenclature to describe the disparate range of cultural material produced over the past twenty years [moreover, in 2024, over the past thirty-five years], for it has grown, metamorphosed, and developed within the orbit of an avowedly socialist state whose gravitational pull is often all too irresistible and that has itself undergone an extraordinary transformation. Both have matured together and used each other, feeding each other’s needs and developing ever new coalitions, understandings, and compromises.

— from Introduction: a Culture in the Red, pp.xiv-xv

***

CCP™ & Adcult PRC, a revised version of which was included as a chapter in In the Red, highlights the intersection of advertising and avant-garde/ popular culture, on the one hand, and politics and propaganda (or ‘representational pedagogy’), on the other. It addresses the question: ‘what happens when corporate competition feeds into patterns established by party-ordained ideological conditioning?’ In it, I observed that:

The party has moved to present itself not simply as the ruling political party, zhizheng dang [執政黨], an expression used to sheathe the apparatus of rule in a cloak of constitutional formality, but also as the final or ultimate historical choice of the Chinese people. Moreover, its multifaceted propaganda/public relations organizations increasingly represent it through a statist-corporate voice that offers basic definitions of group morality and ethics, consensus, coherence, and community in ways more familiar to us from international corporate advertising practice than Maoist hyperpropaganda. Not only does the party manipulate routine public pronouncements and orchestrate news reporting to achieve this end; it pursues its goals also through a range of national media entertainments and promotions. It realizes this through the party’s Propaganda Department, the government instrumentalities devoted to public enlightenment like the Ministries of Culture and Television and Broadcasting … as well as a myriad of subordinate organizations: party newspapers, Central TV, Central People’s Radio, and so on. At other times, the party’s messages are conveyed through nonparty organs and allied mass media that are directed at one level or another by in-house party committees. Such committees function as both surrogates for party authority and representatives if not mediators for nonparty interests. As a result, they are enmeshed in a complex of relationships that range from the purely propagandistic-ideological to the corporate-promotional. …

The nascent avant-garde culture of the 1980s and early 1990s employed subversive strategies and engaged in an insurgent reworking of traditional party symbols, language, or histories. In this process, many of the artists functioned in parallel to official culture. If not working for state institutions, at least they often fed off their funding and structures while advancing their own agendas. Some of the cultural products of these artists were in turn cannibalized in the 1990s by party propagandists, especially younger media workers (some of whom also play a double role as nonofficial artists), to serve, expand, and diversify the interests of entrenched power elites, including themselves. In the continued, often fractious, negotiation between state and nonstate state culture, this mutual cannibalization led to the creation of a relatively more vital audiovisual pedagogical culture. …

— from CCP™ & Adcult PRC, In the Red: on contemporary Chinese culture, New York: Columbia University Press, 1999, pp.235-254

***

When the East is Read

In 2009, Beijing allocated dedicated funds to enhance its international propaganda/ PR/ outreach activities. Capitalising on the success of what, from 2007, propagandists referred to as ‘telling the China story’ 講中國的故事 in the lead up to the 2008 Beijing Olympics, the authorities launched a Global Strategy for China’s External Propaganda 中國對外宣傳大佈局, known simply as大外宣 dàwàixuān ‘large-scale external propaganda’.

The new propaganda push built on an enterprise that evolved during the 1930s and flourished during the Sino-Japanese War and the Civil War of the 1940s. Following the ‘PR disaster’ of June Fourth 1989, renewed efforts were made to enhance the effectiveness of Party propaganda both in China and internationally. Again, as I observed in CCP™ & Adcult PRC:

Generational changes have meant that the party’s media outlets, as well as the media in general, are run by worldly younger men and women, people trained in the post-Mao educational environment who are more in touch than their predecessors with the social realities of the country. As I noted, some of those “propagandists” (the word has a quaint air when once considers the role of these individuals) also are active participants in nonofficial cultural activities. Through this new corps of media personnel, the overall party view of history, nationhood, and identity has to an extent been successfully refashioned and has become part of the basic range of signs, the paleosymbolism, that propagandist advertisers appeal to even when they do not directly represent them or even place any store in them. As Mihajlo Mihajlov observed in regard to Soviet propaganda in the past, “those very myths and fictions themselves become instruments of power even when the subjects cease to believe in them.”

Today, China’s efforts to influence international opinion are multifaceted. Apart from official news outlets, diplomatic channels and soft culture pursuits, a range of unofficial and quasi-official actors flood the zone with information. The label dawaixuan is readily used by online commentators to lambast anyone or anything that promotes pro-Beijing messages. The ‘red scare paranoia’ of the present age also means that useful and balanced information about on-the-ground Chinese realities is also dismissed as propaganda.

Among the information/ influence operations the Center for China and Globalization (CCG) in Beijing is noteworthy. Although CCG promotes itself as being ‘a leading non-governmental think tank’, even the most generous consumers of its publications and activities recognise that it is ‘party-state adjacent’. Its publications include the substack newsletters The East is Read, quoted at length below, and Pekingnology, edited by Zichen Wang, a former Xinhua journalist, and CCG Update.

Although operating within the byzantine matrix of dawaixuan, publications like The East is Read and Pekingnology are what, for want of a better term, I think of as ’boutique prop-info’ 精巧小外宣. They are a soft power effort to influence professional opinion internationally that also offer a useful reflection by relatively thoughtful (even self-aware), and often incisive, people working within the system whose opinions range from the orthodox to the permissibly heterodox. They reflect a plurality of ideas in contemporary China. We would note, however, that pluralism — regardless of what some wrong-headed observers may claim — has simply been policed into silence.

China Heritage has previously featured the work of the Center for China and Globalization (CCG) in:

- Xi Jinping’s Silos — the corrosive individualism of collectives, 8 January 2023, Appendix LIX in Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium; and,

- Professor Graham ‘Thucydides Trap’ Allison’s Three-Body Problem in Watching China Watching, 28 March 2024

Officially tolerated quasi-independent publications like Pekingnology and The East is Read are part of the ‘grey information economy’ that flourishes within what, since the 1980s, we have called China’s ‘velvet prison’. (For more on this topic, see Less Velvet, More Prison and Elephants & Anacondas.) And, as we have noted elsewhere:

Participants in the grey information economy, be they academics, policy wonks, journalists or freelance commentators partake of a hallowed tradition in which canny authors ‘write between the lines’. Theirs is a well-honed art that enables writers of all kinds to communicate uncomfortable truths within the boundaries of permitted speech. The adept can utilise their authorial dexterity to identify issues of pressing concern, skirt around the systemic origin of problems without challenging the system itself and even offer palliative advice and partial cures to egregious problems. An ancient art honed to perfection under the party-state, it is often referred to as ‘hitting line-balls’ 打擦邊球. Practitioners are, to use a short-hand, expert at ‘pointing at the mulberry while vilifying the locust’ 指桑罵槐. Other well-worn clichés also reflect this well-practiced technique of seeking the solace of self-expression within a repressive environment. They include:

拐彎抹角 、含沙射影 、借題發揮 、

隱晦曲折 、旁敲側擊 、指雞罵狗。

The Hungarian writer Miklós Haraszti summed up this state of affairs decades ago:

Communication between the lines already dominates our directed culture. This technique is not the speciality of the artist only. Bureaucrats, too, speak between the lines: they, too, apply self-censorship. Even the most loyal subject must wear bifocals to read between the lines: this is in fact the only way to decipher the real structure of our culture… .

The reader must not think that we detest the perversity of this hidden public life and that we participate in it because we are forced to. On the contrary, the technique of writing between the lines is, for us, identical with artistic technique. It is a part of our skill and a test of our professionalism. Even the prestige accorded to us by officialdom is partly predicated on our talent for talking between the lines… .

… Debates between the lines are an acceptable launching ground for trial balloons, a laboratory of consensus, a chamber for the expression of manageable new interests, an archive of weather reports. The opinions expressed there are not alien to the state but are perhaps simply premature. (Quoted in Less Velvet, More Prison.)

Publications like The East is Read and Pekingnology have a Janus-face. They look inward for guidance from the party-state while reporting material beyond the ken, or beneath the eye-sight, of official propagandists. They also hark back to some of the quasi-independent aspirations of the Chinese media that flourished before the monomaniacal propaganda regime of the Xi Jinping era re-imposed monotony and tedium, and they hint at a possibility, no matter how distant in the future, when a multiplicity of Chinese voices may be heard.

***

The following digest, by the editors of The East is Read, provides an insight into the present state of China’s academic Velvet Prison, as well as of the thoughtful, and agonised, process by which some leading scholars strive to protect and advance their work. Although those quoted below are all Establishment Intellectuals, their efforts, while contributing to the party-state which they must serve, also enhance The Other China and engage in various ways with China’s (fitfully) evolving global Republic of Letters.

The Giant Panda in the Room, the name that cannot be spoken in such polite academic society and one that is elided when telling the China Story in a way that can actually engage international professionals, be they academics or others, is Xi Jinping, CoE (Chairman of Everything) of the Chinese Communist Party, auteur of His Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for the New Era and the multifarious ways in which Xi has re-infiltrated Chinese life with the self-serving imperatives of the party-state.

The scholarly ruminations below betray, as one correspondent commented, the fact that ‘their authors are obliged by the times and the dictates of self-preservation to couch their thoughts and recommendations in euphemism, elision and abstraction. One needs program notes to divine what they really mean. Or maybe I’m simply reflecting my personal reaction as one once pursuing degrees in, ugh, Political Science and International Relations. Even then, I knew in my heart, as did many of my profs, that “Area Studies” was a more legitimate and meaningful academic endeavor than the pursuit of the Holy Grail of new “theoretical structures” and “methods of quantitative analysis” to reveal all in a flash.’ (For more on this, see New Sinology in 1964 and 2022.)

As the academics below steer a course between the Scylla of self-serving loyalty to an academy controlled and funded by the party-state and the Charybdis of professionalism and international recognition that operates according to its own protocols, the dark shadow of Party dominion looms, unmistakable, unavoidable and, by and large, unmentionable.

For our dissuasion of the lost tradition of free thought and independent scholarship in China today, see The Two Scholars Who Haunt Tsinghua University, China Heritage, 28 April 2019

***

The thrall in which an ideology holds a people is best measured by their collective inability to imagine alternatives.

— Tony Judt, Captive Minds, Then and Now

Yan Xuetong’s Angst

Yan Xuetong, Director of the Institute of International Studies at Tsinghua University is an internationally recognized scholar.

In New Ghosts, Old Dreams: Chinese rebel voices (1992), we used the metaphor of bound feet 纏足 chán zú/裹腳 guǒ jiǎo to discuss the stifling of independent thought and free expression in modern China. The bound foot was a symbol of the bound self, the bones of individuality broken by intellectual convention, social conformism, ideological dogma and patriarchal power. We referred to true individuals as people who have never allowed their feet to be crushed by convention and who had natural or unbound feet 天足 tiān zú; they were people generally deemed by the rest of society to have grown ‘too big for their boots’.

Reformers, who would loosen the bindings not only for themselves but also for their fellows, were more like women whose bindings have been taken off after they initially had their feet, or spirit, broken by the dogma and convention. While the crushed bones and toes of their ‘liberated feet’ — 放足 fàngzú or 解放腳 jiě fàng jiǎo — might gradually assume a more natural appearance, nonetheless, they were forever condemned to hobble.

Today, in Xi Jinping’s China where 真偽莫辨 — it is hard to distinguish the true from the counterfeit — many Sethinking people who have not been completely silenced are condemned to hobble 一瘸一拐 yī qué yī guǎi.

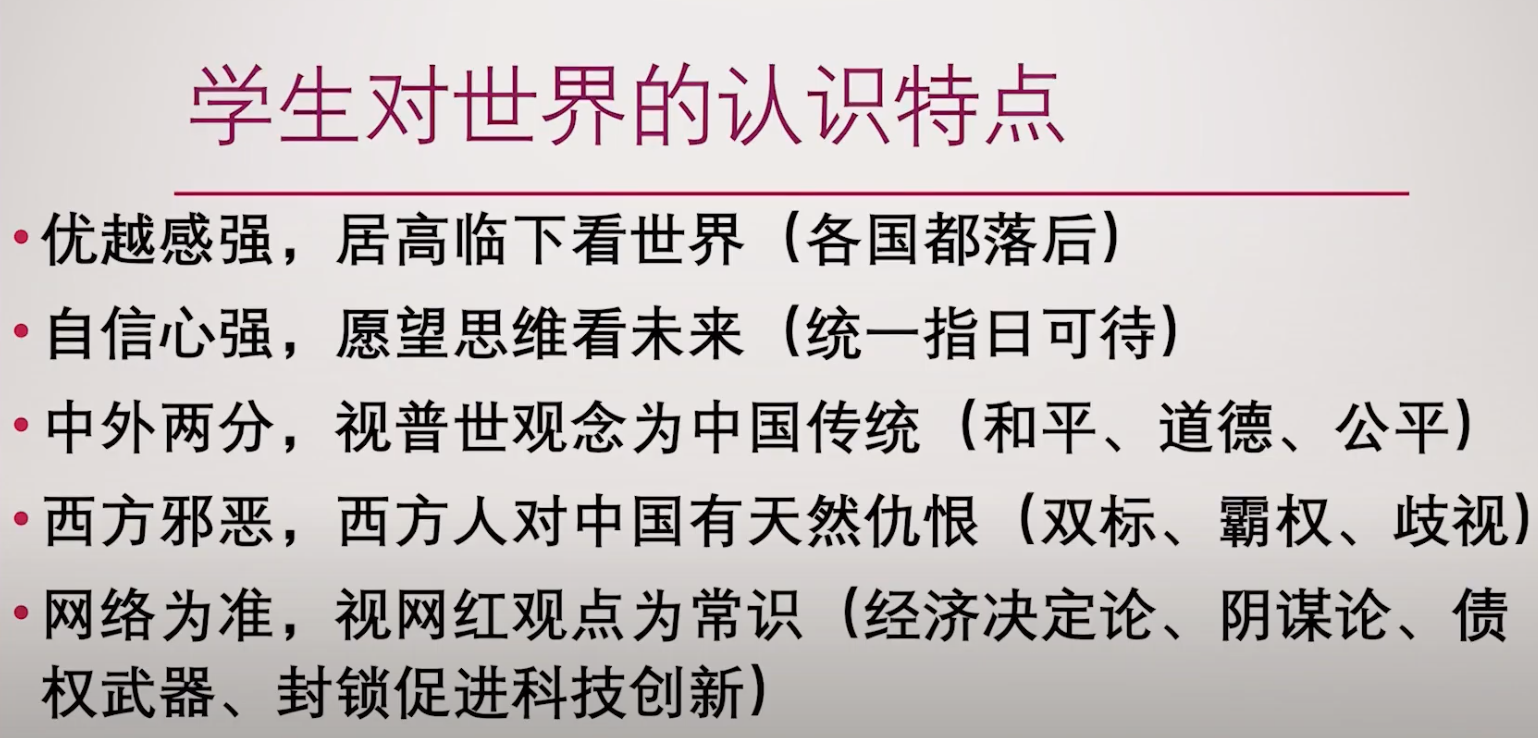

In January 2022, the following video enjoyed a viral moment. In a mood of high dudgeon, Yan Xuetong discusses the mindset of university students that he has encountered in recent years:

On the Patronising Worldview of China’s Millennials

一闊臉就變

***

[Note: For transcription of Yan’s remarks, see 【CDTV】清華國際關係研究院院長閻學通評00後:優越感強、中外兩分、西方邪惡,《中國數字時代》,2022年1月22日; and, for a précis of Yan, see Shangjun Yang, Peiyu Li and Zichen Wang, Yan Xuetong says telling truth from falsehood is top priority for students of international relations, Pekingnology, 11 December 2023, which also includes useful translations of some of Yan Xutong’s observations about academia and the field of International Relations in contemporary China.]

***

The subtitle that we added to Yan Xuetong’s comments above —一闊臉就變 yī kuò liǎn jìu biàn, or ‘their demeanor changes as soon as they’re on top’ — comes from a famous poem written by Lu Xun for Wu Qishan 鄔其山, aka Uchiyama Kanzō 内山完造, a Christian Japanese bookseller who was active in Shanghai and sympathetic to ‘the left’, in 1931:

廿年居上海,每日見中華。

有病不求藥,無聊才讀書。

一闊臉就變,所砍頭漸多。

忽而又下野,南無阿彌陀。

—— 鲁迅《贈鄔其山》

***

In his remarks, Yan Xuetong mentions the outsize impact that online influencers have on his students. Three decades, three paradigm shifts: how the internet transformed China, another report published by The East is Read (7 May 2024), offers a useful overview of the subject although, as is the case of the discussion of academia disciplines in contemporary China quoted below, the editors offer no broader context for the material they introduce. For Yan’s thoughts on influencers, again we refer readers to Yan Xuetong says telling truth from falsehood is top priority for students of international relations, Pekingnology, 11 December 2023, mentioned above.

We would also direct readers to Three decades, three paradigm shifts, a translation published by The East is Read, of an essay by Wang Qingfen 王箐豐 whose WeChat blog 元淦恭說 ranges over such topics as the economy, urbanisation, travel and cuisine. Wang’s short retrospective of the Chinese internet concludes by saying that:

Today, more than ever, a global mindset and cosmopolitanism are essential. As Chinese enterprises, both within the internet sector and beyond, expand globally with unprecedented strength, they also encounter significant challenges and opposition. Their efforts to navigate and conquer global markets deserve the utmost support and recognition.

These sentiments are very much in keeping with the emollient style of The East is Read as a whole: thoughtful opinion including softball suggestions to the powers that be that is punctilious in avoiding the Giant Pandas in the room.

In Wang’s account of ‘paradigm shifts’, it is as though the vast guerrilla war waged by netizens against the party-state that has raged unabated for nearly three decades rages simply didn’t exist. In Wang’s world it appears as there is no Great Firewall; there is no mention of VPNs and their bumpy history; nor any mention of the negative impact of the shuttering of Chinese databases and academic content to the outside world. Sidestepped too is the issue of whether the chokehold that the party-state maintains over the free flow of information has an impact on Chinese innovation. Of course, ignored also is the exponential growth of the integrated digital surveillance state and the secretive world of ‘internet privilege’ 網絡特權 that allows some members of the Party nomenklatura, as well as economists, scientists, and others, priority access to the global internet. To delve into such topics, Wang Qinfen and the editors of The East is Read, would have to abandon the permissible and venture into the vast realm of the unsayable. For some observations on these topics, see ‘You are garlic chives!’ — Trisolarans, Burn Book and China’s Men in Black, 20 April 2024.

***

The rules are simple: they lie to us, we know they’re lying, they know we know they’re lying but they keep lying anyway, and we keep pretending to believe them.

— Elena Gorokhova, A Mountain of Crumbs: A Memoir, 2011

Conflicted Loyalties—professional and partisan

In October 2016, Li Hongzhong, Party Secretary of Tianjin and a member of the Central Committee proved himself to be ahead of the laudatory curve that extolled Xi Jinping when he formulated the following palindrome-like slogan:

忠誠不絕對就是絕對不忠誠。

If you’re not absolutely loyal, you’re absolutely not loyal.

— from A Hosanna for Chairman Mao & Canticles for Party General Secretary Xi, Chapter Twenty-two in Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium, 22 October 2022

***

The following material is reproduced from The East is Read. They style of the original has been retained.

— GRB

China’s top educators grapple with unprecedented challenges to Poli Sci and International Relations

Consensus of leading political scientists and IR scholars at key forum over future of their disciplines

Haokai Li, Zichen Wang and Yuxuan Jia

27 April 2024

Introduction

Almost all universities in the Chinese mainland, including every prestigious one, are state-operated. The Ministry of Education of China sets nationwide categories for academic disciplines at Chinese universities.

To manage this, the Ministry has implemented a three-tier system to categorize all academic disciplines within Chinese universities into 14 学科门类 Fields of Disciplines: Philosophy, Economics, Law, Education, Literature, History, Science, Engineering, Agriculture, Medicine, Management, Military Science, Art, and Interdisciplinary Studies. Each field of discipline encompasses 一级学科 Major Disciplines, which further include various 二级学科 Minor Disciplines.

For instance, the Field of Laws, one of the 14 Fields of Disciplines, includes the Major Discipline of Political Science, which encompasses minor disciplines such as Political Science Theory, History of the Communist Party of China, Marxist Theory, Ideological and Political Education, International Politics, International Relations, and Diplomacy, etc. In practice, if you major in International Relations or Marxist Theory at a Chinese university, the academic certificate you receive, as ordered by the Ministry of Education, will show you have a Bachelor of Laws.

This classification system plays a crucial role in shaping the academic landscape of Chinese universities, significantly influencing department structures, faculty titles, funding allocations, and publication opportunities.

In 2020, the Ministry of Education introduced a new Field of Discipline named “Interdisciplinary Studies,” which includes, among others, a Major Discipline called 国家安全学 “National Security Studies.” In September 2022, the ministry made 区域国别学 “Area Studies” another Major Discipline under “Interdisciplinary Studies.”

As a result, universities are now obligated to adjust their academic priorities and reallocate resources accordingly, reflecting the enhanced status of the newly elevated discipline and implementing the will of the government.

The following is the summary of a recent forum, held on December 2, 2023 at Tsinghua University, of China’s leading educators in Poli Sci and International Relations grappling with the changes, provided to The East is Read by Professor Yan Xuetong, Director of the Institute of International Studies, Tsinghua University. The summary is also publicly available on a WeChat blog.

— Zichen Wang and Yuxuan Jia

[Note: Yan Xuetong was also the author of ‘On the Patronising Worldview of China’s Millennials’, quoted above. That video and this report in The East is Read are unrelated. — GRB.]

时代之变:政治学与国际关系学科建设的挑战与方向—2023年清华政治学与国际关系学科发展论坛综述

The Shift of Times: Challenges and Directions of Advancement in Political Science and International Relations Disciplines

— An Overview of the 2023 Tsinghua Forum on the Development of Political Science and International Relations

In recent years, spurred by shifting socio-economic development and evolving restructuring of disciplines, the disciplines of Political Science (Poli sci) and International Relations (IR) have encountered unprecedented challenges and opportunities, and the future trajectory of discipline development emerges as an urgent issue to address.

In 2020 and 2022, the Academic Degrees Commission of the State Council and the Ministry of Education announced the inclusion of National Security Studies and Area Studies as major disciplines into the field of Interdisciplinary Disciplines respectively. This marked a significant restructuring and integration of the disciplines of Poli sci and IR. Concurrently, there is a gradual contraction in the scale of these disciplines, a decrease in the number of schools participating in the China Discipline Evaluation [a nationwide ranking program of university disciplines by the China Academic Degrees and Graduate Education Development Centre under the Ministry of Education], as well as reductions in faculty and student numbers. These shifts have prompted extensive and in-depth discussions within the academic community about the structuring of disciplines, their focus, and how to train future scholars.

It was against this backdrop that on December 2, 2023, the School of Social Sciences, the Department of International Relations, and the Department of Political Science at Tsinghua University jointly hosted the “2023 Forum on the Development of Political Science and International Relations.” Thirty-two faculty leaders and scholars of Poli sci and IR from 20 prestigious institutions—including Tsinghua University, Peking University, Renmin University of China, the Central Party School of the Communist Party of China, University of International Business and Economics, Beijing Foreign Studies University, China Foreign Affairs University, Beijing Language and Culture University, Nankai University, Nanjing University, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shandong University, Sun Yat-sen University, Tongji University, Sichuan University, East China University of Political Science and Law, Central China Normal University, Zhengzhou University, Jinan University, and Tianjin Normal University—participated in this forum.

The opening ceremony of the forum was presided over by Prof. Zhao Kejin, Vice Dean of the School of Social Sciences at Tsinghua University. Prof. Yang Yongheng, Director of the Office of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences Administration at Tsinghua University, delivered the opening remarks. Scholars engaged in lively discussions on topics such as:

- challenges facing the development of Poli sci and IR;

- directions for discipline development in the New Era;*

- establishment of an independent knowledge system in the disciplines of Poli sci and IR; and,

- objectives for talent cultivation in Poli sci and IR.

The summary below encapsulates the key viewpoints shared during the forum.

[Note: ’New Era’ 新時期 is a term meaning ‘since Xi Jinping came to power in late 2012’. — Ed.]

Challenges Facing the Development of Political Science and International Relations Disciplines

Scholars explored the challenges facing the development of Poli sci and IR based on the unique characteristics and current situations of these disciplines at their respective universities. They addressed pivotal issues including “restructuring of disciplines,” “opening up internationally and specialization of the disciplines,” “the relationship between politics and academic research,” and the emergence of 学术网红 “influencers masquerading as scholars.”

Prof. Yan Xuetong, Distinguished Professor in Humanities and Dean of the Institute of International Relations at Tsinghua University, emphasized the urgent need to tackle the practical challenge of discipline development amidst obstacles facing Poli sci and IR in China. He identified three prevailing dilemmas in the current development of IR and Poli sci:

- A contraction in the scale of these disciplines, leading to continuously reduced societal impact.

- A decline in openness internationally and a growing gap in academic excellence from international peers, even though international exchanges remain essential for their development.

- A decrease in the rigor and specialization of these disciplines, as evaluations based on academic contribution declined.

Prof. Wu Xiaolin, Vice Dean of the Zhou Enlai School of Government at Nankai University, articulated four key concerns about the development of Poli sci and IR.

- The restructuring has led to the fragmentation of traditional Poli sci. This has not only precipitated a developmental crisis in traditional disciplines but has also resulted in the restriction of enrollment quotas and academic resources. However, from a broader perspective, one can optimistically view it as the expansion of disciplines.

- The increasing focus on employment and income has diminished the attractiveness of humanities and social sciences.

- Despite a decrease in international academic exchanges, maintaining active international engagement is crucial, as the development of a discipline cannot be isolated from the international community.

- The emergence of so-called “influencers” within Poli sci and IR raises concerns, as they could potentially skew public opinions and perceptions of the disciplines. Therefore, Wu stressed the importance of adhering to academic standards and maintaining professional integrity within these fields.

In terms of focus and positioning, managing the relationship between Poli sci and IR and other disciplines, particularly traditional ones like Marxism and public administration, as well as emerging ones such as Area Studies and National Security Studies, has become a central issue among scholars.

Prof. Tang Shiqi, Dean of the School of International Studies at Peking University, observed that ongoing transformations within disciplines have significantly impacted their focus. As institutions and universities increasingly shift their attention toward disciplines like National Security Studies or International Affairs, the growth of Poli sci and IR is encountering heightened pressures.

Prof. Hu Zongshan, Dean of the School of Politics and International Relations at Central China Normal University, highlighted the challenges facing the development of Poli sci and IR as scholars increasingly move towards fields such as Marxism and public administration. Additionally, a decline in academic publications and a lack of specialization within the Poli sci and IR disciplines also pose significant obstacles. He argued that only through enhancing specialization can the continuous development of Poli sci and IR be secured, lest they become characterized by 假大空 “fake, grand, and empty.”

Prof. Liu Changming, Dean of the School of Northeast Asia Studies at Shandong University, also addressed this topic. He highlighted the blurred boundaries between Poli sci and other disciplines as a primary factor hindering the development of Poli sci. He stressed the importance of clearly delineating which issues should be tackled by Poli sci and which should be handled by other disciplines such as public administration or Marxism. Furthermore, he noted that the scarcity of theoretical innovation is a significant challenge for the development of Poli sci, as many textbooks continue to rely on outdated theories that are ineffective in addressing contemporary societal issues.

Moreover, some scholars engaged in discussions surrounding the specific challenges encountered in the development of Poli sci and IR disciplines at their respective institutions.

Prof. Xie Tao, Dean of the School of International Relations and Diplomacy at Beijing Foreign Studies University, detailed the practical difficulties at their institution. He noted the suspension of undergraduate programs in Poli sci and public administration at Beijing Foreign Studies University, coupled with the rise of Area Studies, has posed significant challenges to the advancement of the Poli sci and IR disciplines. In this context, deciding whether to maintain the traditional IR discipline has become a difficult decision.

Prof. Huang Qixuan, Associate Dean of the School of International and Public Affairs at Shanghai Jiao Tong University, outlined two primary challenges in their discipline development, along with proposed solutions.

- Maintaining a delicate balance between organized research and academic autonomy. He expressed concern that an excessive emphasis on organized research could burden young faculty members and stifle individual innovation. Therefore, he advocated providing faculty members with opportunities for independent exploration while they are put in organized research.

- Discipline development should not occur in isolation but must include a push for opening up internationally, particularly through enhancing publication in international journals and producing high-quality books.

Prof. Yu Li, Associate Dean of the School of Politics and Public Administration at Zhengzhou University, shared insights from the arduous journey of developing the Poli sci discipline at her university. She proposed a discipline development strategy that uses Poli sci as the foundation, supported by Interdisciplinary Studies, and encouraged her colleagues to face the challenges of discipline development with responsibility and confidence.

Prof. Wei Ling, Secretary of Party Committee of the School of International Relations at University of International Business and Economics, discussed the opportunities and challenges of developing disciplines at her university. She noted that the integration of resources and support for key projects, such as the major disciplines promotion funds and the Computing Laboratory for National Security (CLNS), has established a strong foundation for discipline development. However, she also identified significant challenges, including the potential shrinkage of traditional disciplines due to restructuring of disciplines and dual pressures on enrollment capacity and educational resources resulting from restrictions on student and faculty numbers.

The Directions for Discipline Development in the New Era

Scholars provided valuable insights and experiences on enhancing the disciplines of Poli sci and IR in the New Era, focusing on future directions for their development. There was a universal agreement on adopting an international approach to promote these disciplines, improve standards, and encourage professionalism while rejecting trends in favor of money and vanity as well as the pursuit of becoming influencers on the Internet. They emphasized that theoretical and methodological innovation is crucial for deepening the development of these fields. These perspectives collectively form the core consensus on the development of the disciplines among the participating scholars.

Prof. Yan Xuetong from Tsinghua University advocated for four crucial principles for the future development of Poli sci and IR.

- Following the fundamental principle of opening up internationally, encouraging collaborative education programs, international exchanges, and publishing in international journals. Guard against the trend that seeks to legitimatize closing the door to opening up.

- Maintaining high academic standards, keeping significant distance from the ecosystem of online influencers, enhancing professional awareness and capabilities, and prioritizing the education of students.

- Upholding scholarly rigor, rejecting propaganda in academic publications and the use of mass media publications as criteria for evaluation and promotion.

- Encouraging specialization among scholars and opposing the phenomenon of “pseudo-intellectual” masquerading as know-it-all, unfounded viewpoints, and sensationalism in academic output.

Prof. Huang Qixuan from Shanghai Jiao Tong University also introduced three principles for the development of the disciplines.

- Encouraging interdisciplinary integration and collaboration within Poli sci, nurturing promising scholars in this field.

- Adhering to methodology-driven and scientific research.

- Maintaining an international vision and aligning the discipline landscape with strategic demands in a timely manner to contribute to the establishment of China’s independent knowledge system.

Prof. Zhao Kejin from Tsinghua University provided three suggestions for enhancing the disciplines.

- Emphasizing the quality of development, ensuring domestic and international impact and reputation, even amidst an overall decline in the scale of the disciplines.

- Emphasizing innovation in theory, the cornerstone for sustainable development of disciplines.

- Promoting integrated development across disciplines, as updates to traditional methods through interdisciplinary integrations becomes increasingly important when digitalization disrupts many theories of the industrial age.

Prof. Di Dongsheng, Vice Dean of the School of International Studies at Renmin University of China, asserted against pessimism in the face of challenges, seeing opportunities within crises. He observed that Poli sci is on the brink of an upward turn in its development cycle. In a time increasingly characterized by pragmatism, he underscored the critical importance of sustaining the academic and theoretical development of the discipline. He puts forward three suggestions.

- Highlighting the importance of textbook knowledge, and recognizing students’ foremost duty of learning.

- Guarding against the seduction of becoming influencers and emphasizing the professionalism of scholarly research.

- Establishing a conducive learning environment to solidify students’ basic knowledge in their disciplines.

Prof. Zhu Feng, Executive Dean of the School of International Relations at Nanjing University, recognized the significant national strategic demands on IR amidst “changes unseen in a century,” along with inherent driving forces for promoting an independent IR discipline. He shared Nanjing University’s experience in developing the IR discipline, which involves the basic discipline of Poli sci and its branch, international politics, as well as area studies. He emphasized that area studies contain not only historical and language studies, but should also encompass a wide range of fields such as culture and society. He advocated for selecting foundational theories for the future development of area studies, urging that these theories be grounded in social science perspectives.

Prof. Men Honghua, Dean of the School of Politics and International Relations of Tongji University, put forward a development strategy for the disciplines based on Tongji University’s experience. This strategy focuses on promoting first-class faculty, underpinned by a high-quality talent education system, guided by signature research outputs, and supported by comprehensive international exchanges and cooperation. He highlighted that strategic studies, particularly strategic studies on China, should be central to discipline advancement. He emphasized the importance of nurturing strategic talents who possess historical and theoretical knowledge, professional expertise, international vision, and practical capabilities. Additionally, he stressed the need to establish a platform that integrates research, teaching, and consultation functions, pursue national rejuvenation amid significant global changes, deepen cooperation with ministries, and promote the discipline with the goal of leading China’s strategic development, focusing on the country’s modernization, strengthening think tank development, and serving the strategic needs of the nation.

Prof. Wu Zhicheng, the Vice Dean of the Institute of International Strategic Studies at the Central Party School of the Communist Party of China, highlighted the role of scholars in Poli sci and IR as pioneers of academic research, pacesetters of the social ethos, and staunch supporters of the Chinese modernization. He emphasized the importance of focusing on the theoretical, systematic, and concise transformation of knowledge, treating science with a scientific attitude, and developing academia in an academic manner. He called for integrating new ideas, thoughts, and strategies into the discipline system to support these goals.

Establishment of an Independent Knowledge System in Poli sci and IR

Establishing an independent knowledge system has become a core topic within the field of Chinese philosophy and social sciences. While the independent knowledge system in the field of Poli sci (including public administration, International Relations, and diplomatic theory) is maturing within the national context, its global influence is still limited. Building China’s independent knowledge system in Poli sci and IR is pivotal not only for fostering academic autonomy and innovation but also for enhancing the international stature of these disciplines. Faced with this challenge, several scholars have put forth their insights and proposals aimed at not just innovating autonomously in Poli sci and IR theories but also in applying these theories practically and broadening their international reach.

Prof. Zhao Kejin identified three essential conditions for building China’s independent knowledge system in Poli sci and IR.

- Academic autonomy. He argued that true independence in knowledge systems can only be achieved when scholars produce academic outcomes independently.