Watching China Watching

陷阱

Watching China Watching was launched in January 2018. The first chapter in the series consisted of The China Expert, an essay by Simon Leys originally published in 1981, and the now-famous Ten Commandments of László Ladány from 1982. In so doing we continued to pursue New Sinology, an approach to China that is mindful of current affairs as well as being grounded in a broader humanistic engagement both with the present and the past. We had previously addressed the topic of The China Expert 中國通, or Old China Hand, when introducing readers of China Heritage to the idea of Jao Tsung-I 饒宗頤, the great Hong Kong littérateur.

Today, China Experts and China Watchers flourish once more. A once nearly-defunct claque of people working in government for national political ends, journalists, academics, ne’er-do-wells, as well as the talented curious and literary dilettantes jostle and contend with each other in the New Epoch of Chairman of Everything Xi Jinping. The long-overlooked, or underestimated, skills of being able to read, listen to and understand the bloviations of the Chinese party-state are even somewhat in vogue. Although Xi Jinping has been a boon for strategic thinkers, think tanks and academic opinionators in Euramerica, China’s own market for strategists — 戰略家、謀略家、謀士、縱橫家、說客, and so on — has fallen under the sway of the Communist Party. [Note: The colourful and wildly imaginative efforts of the previous ‘hundred schools’ have been reduced to a far more modest and grey palette of opinion. Those on both sides of the divide do, nonetheless, share similar ambitions: to serve ideological interests, to make a name, curry favour and influence while enjoying a slice of the cake that through their efforts is ever bigger. One of the time-honoured ways of grabbing the discursive spotlight is to formulate an expression or catch-phrase that gains currency.

[Note: For an early comment on the rise of the strategist in China after 4 June 1989, see my introduction to A Word of Advice to the Politburo, January 1990.]

Many, although by no means all, of the non-mainland China Experts of the 2020s bear the genetic imprint of their predecessors.

What a successful China Expert needs, first and foremost, is not so much China expertise as expertise at being an Expert. Does this mean that accidental competence in Chinese affairs could be a liability for a China Expert? Not necessarily — at least not as long as he can hide it as well as his basic ignorance. The Expert should in all circumstances say nothing, but he should say it at great length, in four or five volumes, thoughtfully and from a prestigious vantage point. The Expert cultivates Objectivity, Balance and Fair-Mindedness, in any conflict between your subjectivity and his subjectivity, these qualities enable him, at the crucial juncture, to lift himself by his bootstraps high up into the realm of objectivity, whence he will arbitrate in all serenity and deliver the final conclusion.

— from The China Expert and The Ten Commandments — Watching China Watching (I), China Heritage, 5 January 2018

***

***

On 27 March 2024, The Global Times reported that:

Chinese President Xi Jinping met representatives from the US business, strategic and academic communities in Beijing on Wednesday, as China hosts a series of high-level events this week, demonstrating the country’s commitment to attracting more foreign investment and expanding its opening-up to the world.

Some experts believe that such a rare meeting between the top Chinese leader and the US representatives not only signals China’s expectation that bilateral relations will continue to improve since the San Francisco meeting between the Chinese and US top leaders in November 2023, but also shows that China is focusing more on engaging with American people as it welcomes US investment to achieve greater intertwining interests between the industries of the two sides. It is to “make the cake bigger,” experts said.

The representative of the ‘strategic community’ was none other than Graham Allison, a Harvard academic and self-described acolyte of Henry Kissinger whose China fame is related to his thesis regarding the ‘Thucydides Trap’. Initially essayed in an article published in the Financial Times in August 2012, Allison later expanded his thesis in a book titledDestined for War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides’s Trap?. The demise of his mentor — a centenarian Davros-like figure who died in November 2023 — has left a Kissinger-size hole in the Sino-American multiverse. Professor Allison might possibly believe that he is the right man in the right place at the right time. But the Harvard academic also has something of a ‘three-body problem’, shape-shifting as he does between his role as an academic, a market-oriented commentator and a new ‘old friend of China’. Like the three bodies of the eponymous novel and its screen adaptations, Allison is enmeshed in the gravitational pull of three personæ.

Then again, this is no problem at all. Insinuating a catch-phrase into political discourse, garnering fame, influence and funding, and being invited to High Table as part of what Lu Xun called the ‘feast of human flesh’. It’s what a strategist might call a ‘win-win’ situation.

[Note: For more on Kissinger in China Heritage, see Kissinger Scores a Century, 27 May 2023; and, Kissinger — a myth in his own time, 13 December 2023. For Lu Xun on the ‘feast of human flesh’, see Cauldron.]

***

***

Emperor One Direction

指明帝曰

Xi Jinping made an important speech at a meeting focussed on the study of the important speeches of Xi Jinping in which he called on all members of the Communist Party to study Xi Jinping’s important speeches.

習近平在全黨學習習近平重要講話的會議上發表重要講話要求全黨學習習近平重要講話。

— from Deng Yuwen, quoted in Xi at XI — More Mao Than Ever, 23 December 2023

***

For connoisseurs of autocracy, we recommend an observation made by Hu Ping 胡平, a veteran champion of free speech. He noted that the word ‘dictator’ — one notably used by US President Joe Biden to describe Xi Jinping’s incontrovertible role in China — comes from the Latin ‘dictate’, to assert, declaim, or say for the purposed of being noted down. That Chinese audiences make a show of jotting down the Leader’s every utterance, no matter how stale, rote or trivial, is par for the course. For prominent American businessmen and academics to ape the performance is nothing less than delicious.

— GRB

***

At the meeting at Beijing’s Great Hall of the People, Graham Allison was called upon to offer an encomium to Xi Jinping directly:

‘I’ve been a careful reader of Your Thoughts, Your Speeches, Your Press Statements and Discussions for many years. …’

我一直是您认真的‘读者’。多年以来,我认真学习您的思想、您的讲话,以及您的记者发布会和谈话。

Allison, like his fellow Americans, also expressed gratitude to Xi for his positive role in the US-China Summit of November 2023 which ‘shored up the expectation and confidence of all sectors of American society and the world in U.S.-China relations.’ It was all exquisitely cringeworthy although hardly the most embarrassing own-goal at Harvard of late.

***

Update

In an interview published by Global Times on 30 March 2024, Professor Allison opined that:

President Xi said earlier in his conversations with US Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer in October, “I am in you and you are in me.” For the US and China today, it means our survival requires a degree of cooperation. That’s a big idea. For me to survive, I have to work with you. And for you to survive, you have to work with me. I believe it’s true.

The metaphor that I use is, in biology, there’s this phenomenon in which occasionally human beings are born as inseparable, conjoined Siamese twins. There are two heads. But they have the same nervous system or the same gastrointestinal system. If either of us were to strangle the other one, we commit suicide. That’s pretty stabilizing, because I now have a stake in you and you have a stake in me.

Grasping for a new quote-worthy soundbite, Allison delivered yet another nonsense. The good professor really is a gift that keeps on giving.

For our view of what we have long referred to as the US-China danse macabre, see:

- Mangling May Fourth in Beijing, 8 May 2020; and,

- Mangling May Fourth in Washington, 14 May 2020

For a view of the prospects for China’s reforms under Xi Jinping and what that means for gastrointestinal fortitude of opportunistic American China Watchers, see:

- 專訪吳國光:習近平逆轉型,剛性統治下改革開放不會再現,VOA,油管,2024年3月30日

***

The Peloponnesian War by Thucydides formed a significant part of my high-school Ancient History course and our teacher, a scholar of Greek and Latin in his own right, guided us through the key chapters, speeches and events in that magisterial work. Over the decades since then, I have often returned to that text and read some of the scholarship related to it and that’s why when I encountered Professor Allison’s formulation of the Thucydides Trap, I — like so many others — immediately recognised what in the Antipodes we call ‘a furphy’. It was not surprising, however, that since it seemed to favour Beijing’s agenda that Chinese propagandists readily latched onto the topic and overseas China apologists have been similarly taken with the idea.

With all the talk from the 1990s of China’s ‘peaceful rise’, and given my Maoist education and innate skepticism, not to mention the sobering geopolitical realities confronting Australia and New Zealand, I have long recommended another, even more famous, episode of Thucydides’s work. Known as the Melian Dialogue the exchange between an embassy from Athens and the citizens of the island of Melos has long been used to illustrate the ruthless nature of power politics. Even before Allison sprung his Thucydides Trap, Hugh White, an international relations scholar and an old colleague at ANU, employed the Melian Dialogue to warn Australians of their hapless condition in the face of the America-China contest. For the interested reader, there is even a game devoted to negotiating The Melian Dilemma.

***

Shortly after publishing my translation of her account of life in a Maoist cadre school, I visited Yang Jiang, scholar, translator and essayist in her Beijing apartment. Her husband, Qian Zhongshu, a celebrated writer in his own right was also there. In private he was a gleeful raconteur. It just so happened that the Chinese Writers’ Association had recently announced that an annual Mao Dun Literature Prize would be awarded to an outstanding writer. Named after a writer whose work had focussed on the evils of capitalism and the plight of the oppressed, Mao Dun 茅盾 was in particular good odour since he had applied to rejoin the Communist Party on his deathbed in 1981.

Over tea, Zhongshu launched into one of his signature stand-up comedic routines. Quoting passages from Mao Dun’s most famous works from memory, Qian pointed out grammatical errors, syntactical absurdities and linguistic infelicities. He was channeling the kind of nitpicking erudition celebrated by Chinese men of letters for millennia, and he peppered his remarks with quotations from French and English. He chided both the dead Mao Dun and Yao Xueyin 姚雪垠, who was not only very much alive but who also happened to be one of the recipients of the inaugural round of Mao Dun prizes. — Yao was famous for pandering to Mao Zedong’s obsession with Li Zicheng 李自成, a late-Ming peasant rebel who was a totemic figure for the Communists. Switching to English, Zhongshu observed that writers like Yao may well enjoy the ‘ego trip’ of recognition but they deserved nothing but contempt for being ensnared in the ego trap of self-regard reinforced by the approval of the Communist Party.

Book launch, simulcast dialogue with a Party apparatchiki, media coverage and book sales all topped off by meeting with and addressing The One, Xi Jinping — Professor Allison delights in an ego trap of his own making.

***

Following a glowing report on Graham Allison’s Beijing promotional tour, we reproduce a review of Destined for War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides’s Trap? by Arthur Waldron. We are grateful to Professor Waldron and Jeremy Goldkorn for permission to reproduce that review. As ever, my thanks to Reader #1 for looking over the draft of this chapter in Watching China Watching.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

28 March 2024

***

- Mary Beard, Which Thucydides Can You Trust?, New York Review of Books, 30 September 2010

- Joseph S. Nye, The Kindleberger Trap, Belfer Center, Harvard University, 9 January 2017

- Ian Buruma, Are China and the United States Headed for War?, The New Yorker, 19 June 2017

- Hugh White, et al, Is War with China Coming? Contrasting Visions — Book Review Roundtable, Texas National Security Review, 1 November 2017

- The Thucydides Trap Project, Belfer Center, Harvard University

- The Melian Dilemma

- Mary Beard: ‘The ancient world is a metaphor for us’, Financial Times, 20 April 2021

***

Graham Allison’s speech at the Center for China and Globalisation

Founding Dean of Harvard Kennedy School explores a path away from Thucydides’ Trap through U.S.-China strategic concept.

Hi, this is Yuxuan from Beijing. Today, the statement “The ‘Thucydides’s Trap’ is not inevitable” emerged during a dialogue between President Xi Jinping and “representatives from the American business community and strategic academic circles.”

Just five days earlier, Prof. Graham Allison, Founding Dean of the Harvard Kennedy School and former U.S. Assistant Secretary of Defense, who popularized the term “Thucydides’s Trap,” elaborated on the concept at the Center for China & Globalization (CCG). He reflected on the early interest President Xi showed in the idea, advocating for a new model of major power relations between the U.S. and China that incorporates both cooperation and competition.

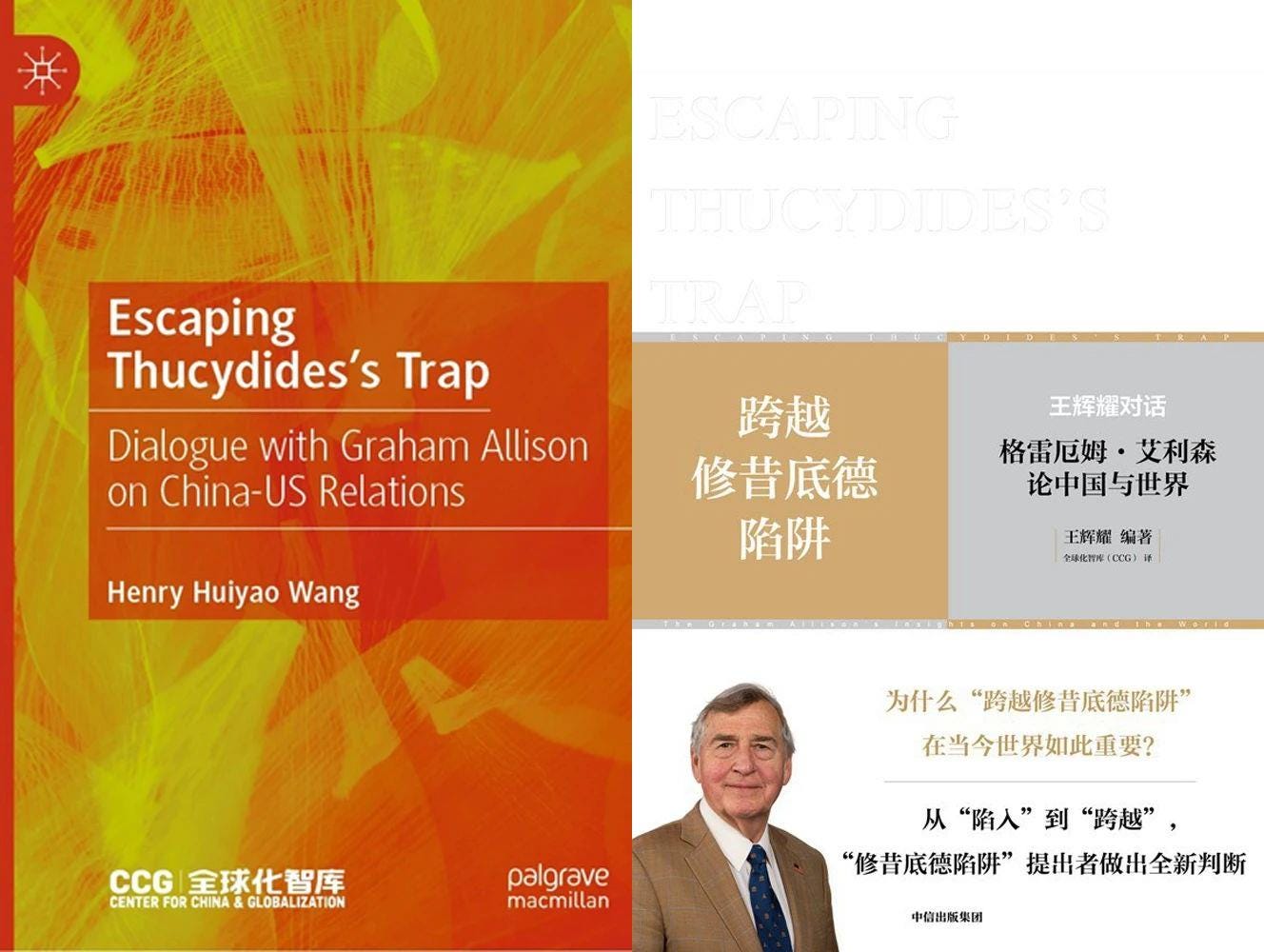

On Friday, March 22, 2024, CCG held a book launch event to release the English edition of the book “Escaping Thucydides’ Trap: Dialogue with Graham Allison on China-US Relations“, published by Palgrave Macmillan, as well as its Chinese edition, published by CITIC Press Group. The book launch was followed by an engaging discussion featuring Henry Huiyao Wang, Founder & President of CCG, and Prof. Graham Allison. This was their third collaboration within the CCG’s Global Dialogue series, with the previous sessions held in April 2021 and March 2022.

“Escaping Thucydides’ Trap: Dialogue with Graham Allison on China-US Relations“ presents a comprehensive collection of Allison’s views and writings on US-China relations from 2017 to 2022, covering a range of topics including the balance of power between the two sides, where the relationship is headed, and lessons from history on how conflict can be avoided. The book also includes an introduction and afterword by Dr. Henry Huiyao Wang, editor of this volume.

The event garnered extensive coverage from multiple media outlets, including Beijing Daily, China News Service, Pheonix TV, Bejing News, China Review News Agency, and China’s Diplomacy in the New Era (dplomacy.org.cn). It was also promoted through the official WeChat blog of the Chinese Embassy in the U.S.

To ensure wide accessibility, CCG broadcasted the event live across various Chinese online platforms such as WeChat, Weibo, Douyin, Kuaishou, Baidu, and Bilibili. The video recordings of the event, both in English and Chinese, are available on YouTube and CCG’s official WeChat blog.

Dr. Huiyao Wang’s dialogue with Prof. Graham Allison at “Escaping Thucydides Trap”

Prof. Allison’s engagement in CCG was part of a productive trip. After the CCG event, he attended the China Development Forum, met with Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi on Tuesday, and on Wednesday, was welcomed by President Xi Jinping.

The CCG Update today presents a transcript of Prof. Allison’s speech at the book launch. Please note that the transcript has not been reviewed by Prof. Allison or his staff and may contain errors.

***

Source:

- Jiawen Zhang and Yuxuan Jia, CCG Update, 27 March 2024

See also:

- Henry Huiyao Wang and Graham Allison in Conversation and Q&A, CCG Update, 31 March 2024

There is no Thucydides Trap

Arthur Waldron

Arthur Waldron is a notable scholar of Chinese history and military affairs whose views are often out of sync with conventional wisdom. In this book review, he argues persuasively against a concept that has become a pillar of establishment thinking on China.

— Jeremy Goldkorn

12 June 2017

***

Book review: Destined for War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides’s Trap, by Graham Allison (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin, 2017)

***

Let us start by observing that perhaps the two greatest classicists of the last century, Professor Donald Kagan of Yale and the late Professor Ernst Badian of Harvard, long ago proved that no such thing exists as the “Thucydides Trap,” certainly not in the actual Greek text of the great History of the Peloponnesian War, perhaps the greatest single work of history ever.

Astonishingly, even the names of these two towering academic giants are absent from the index of this baffling academic farrago. It was penned by Graham Allison, a Harvard professor — associated with the Kennedy School of Government — to whom questions along the lines of “How did you write about The Iliad without mentioning Homer?” should be addressed.

Allison’s argument draws on one sentence of Thucydides’s text: “What made war inevitable was the growth of Athenian Power and the fear which this caused in Sparta.” This lapidary summing up of an entire argument is justly celebrated. It introduced to historiography the idea that wars may have “deep causes,” that resident powers are tragically fated to attack rising powers. It is brilliant and important, no question, but is it correct?

Clearly not for the Peloponnesian War. Generations of scholars have chewed over Thucydides’s text. Every battlefield has been measured. The quantity of academic literature on the topic is overwhelming, dating as far back as 1629 when Thomas Hobbes produced the first English translation.

In the present day, Kagan wrote four volumes in which he modestly but decisively overturned the idea of the Thucydides Trap. Badian did the same.

The problem is that although Thucydides presents the war as started by the resident power, Sparta, out of fear of a rising Athens, he makes it clear first that Athens had an empire, from which it wished to eliminate any Spartan threat by stirring up a war and teaching the hoplite Spartans that they could never win. The Spartans, Kagan tells us, wanted no war, preemptive or otherwise. Dwelling in the deep south, they lived a simple country life that agreed with them. They used iron bars for money and lived on bean soup when not practicing fighting, their main activity. Athens’s rival Corinth, which also wanted a war for her own reasons, taunted the young Spartans into unwonted bellicosity such that they would not even listen to their king, Archidamus, who spoke eloquently against war. Once started, the war was slow to catch fire. Archidamus urged the Athenians to make a small concession — withdraw the Megarian Decree, which embargoed a small, important state — and call it a day. But the Athenians rejected his entreaties. Then plague struck Athens, killing, among others, the leading citizen Pericles.

Both Kagan and Badian note that the reason that the independent states of Hellas, including Athens and Sparta, had lived in peace became clear. Although their peoples were not acquainted, their leaders formed a web of friendship that managed things. The plague eliminated Pericles, the key man in this peace-keeping mechanism. Uncontrolled popular passions took over, and the war was revived, invigorated. It would end up destroying Athens, which had started it. Preemption would have been an incomprehensible concept to the Spartans, but war was not, and when the Athenians forced them into one, they ended up victors. The whole Thucydides Trap — not clear who coined this false phrase — does not exist, even in its prime example. So now we can turn to the hash Professor Allison makes of the unfamiliar material he has chosen.

Ignoring all this, Allison takes Thucydides literally: Wars (sometimes) begin when rising powers like Athens threaten established powers like Sparta. But do they really? The case is difficult to make. Japan was the rising power in 1904 while Russia was long established. Did Russia therefore seek to preempt Japan? No. The Japanese launched a surprise attack on Russia, scuttling the Czar’s fleet. In 1941, the Japanese were again the rising power. Did ever-vigilant America strike out to eliminate the Japanese threat? Wrong. Roosevelt considered it “infamy” when Japan surprised him by attacking Pearl Harbor at a time when the world was already in flames. Switch to Europe — in the 1930s, Germany was obviously the rising, menacing power. Did France, Russia, England, and the other threatened powers move against it? They could not even form an alliance, so the USSR eventually joined Hitler rather than fight him. Exceptions there are, and Allison makes a half-baked effort to find them, but these are not the mainstream. Is this some kind of immense academic lapse?

No. What has really happened is that Allison has caught China fever, not hard around Harvard, although knowing no Chinese language and little Chinese history.

As a result, Allison seems to have been impressed above all by Chinese numbers: population, army size, growth rate, steel production, etc. So if that sentence from Thucydides is correct, then China is clearly a rising power that will want her “place in the sun” — which will lead ineluctably to a collision between rising China (Athens) instigated by the presumably setting U.S. (Sparta), which will see military preemption as the only recourse to avert a loss of power and a Chinese-dominated world. To escape this trap, Allison demands that we must find a way to give China what she wants and forget the lessons of so many previous wars. Many of Allison’s colleagues at Harvard also believe this to be true.

The reality, however, is that Allison’s recipe is actually a recipe for war. Appeasement of aggressors is far more dangerous than measured confrontation. Did China become more aggressive in the South China Sea in the 2000s because the Obama administration got tougher or because it went AWOL on the issue? I’d say the latter is more likely. When it comes to China, we might want to be more mindful of the “Chamberlain Trap” after the peace-loving prime minister of England, one of the authors of the disastrous 1938 Munich agreement that sought to avoid war by concessions, which in fact taught Hitler that the British were easily fooled. That is the trap we are in urgent need of avoiding.

As an intellectual exercise, let us try making the modest substitution in Allison’s argument of Europe for China. Europe — excluding Russia and some other, smaller, countries — has a land area of 3.9 million square miles, which is to say larger than the U.S. at 3.79 million. The European Union GDP is roughly $20 trillion (nominal) while that of the United States perhaps $1 trillion less. Europe had 1,823,000 forces in uniform in 2014, compared with 1,031,000 for the United States today.

Where am I going? If we add educational and technical levels as well as standard of living, one might be forgiven for thinking that, by the numbers, Europe, not China, was the leading potential challenger to the United States. That of course is what the late Jean-Jacques Servan-Schrieber argued in his immensely popular and influential bit of futurology Le Défi Américan [“The American Challenge”] in 1967. It may well be that the great, almost unspoken question of this century is the future of Europe. So far, however, Europe and America have not proven “destined to war.”

Nor are America and China. My late colleague and mentor Ambassador James Lilley liked to recall a lecture given by an American professor about Taiwan. The speaker became increasingly heated, declaring that unless Washington immediately yielded to Beijing’s demands about Taiwan, a nuclear war was unavoidable. A PLA general in attendance was at first puzzled, and then agitated. He turned to the ambassador to whisper a question: “Who is this guy? Does he think we are crazy?” In other words, come whatever, we Chinese are intelligent enough to realize that war — not to mention nuclear war — with the United States would be an insane action that would destroy all China has achieved in the years since Mao’s death in 1976. As I see it, it’s far more likely, but certainly not as sexy, to believe that there will be no “destined” war between China and the U.S. because the Chinese might actually have a clearer reading of history than the scholars at Harvard.

Allison’s book is chock-a-block with facts. And the impressive statistics of China’s growth in military power that Allison cites are real. So are its advances in technology. Furthermore, since 1995, two years before Deng Xiaoping’s death, Beijing simply used military force to seize a maritime formation called “Mischief Reef” from the Philippines — a clear reversal of Deng’s policy of always maintaining good relations with the United States. By 2012, China had occupied the Philippines’ Scarborough Shoal as well, and continues to do so, while fortifying and creating islands in the South China Sea, where long runways were built for military aircraft, rockets deployed, submarines anchored, and in the East China Sea promulgating an Air Defense Identification Zone that just happened to include one Korean island China would like, and another group of such Japanese islands. In other words, since Ambassador Lilley took his friend to hear the American professor, Chinese policy seems to have changed, but how much, and more importantly, why?

Since the attack on Scarborough Shoal, now six years ago, my own opinion is that China expected to have occupied a lot more. Her slightly delusional view of her claims, first made explicit in ASEAN’s winter meeting of 2010 in Hanoi, was that “small” countries would all bow respectfully to China’s new preeminence. This has failed to occur. All of China’s neighbors are now building up strong military capabilities. Japanese and South Korean nuclear weapons are even a possibility. Over-relying on their traditional concept of awesomeness (威 wēi), the Chinese expected a cakewalk. They have got instead an arms race with neighbors including Japan and other American allies and India, too. With so much firepower now in place, the danger of accident, pilot error, faulty command and control, etc. must be considered. But I’d wager that the Chinese would smother an unintended conflict. They are, after all, not idiots.

Allison also provides us with a mélange of statistics showing the great industrial might of China. She produces tons of steel, more than markets can absorb, likewise coal, while serving as the workshop of the world where the computer on which I am writing was manufactured. The mountains of Chinese exports that have shuttered manufacturing in America seem, like the American powerhouse of 50 years ago, set to overwhelm the world rather as Servan-Schreiber expected American-owned business to do in Europe — but did not.

China’s tremendous economic vulnerabilities have no mention in Allison’s book. But they are critical to any reading of China’s future. China imports a huge amount of its energy and is madly planning a vast expansion in nuclear power, including dozens of reactors at sea. She has water endowments similar to Sudan, which means nowhere near enough. The capital intensity of production is very high: In China, one standard energy unit used fully produces 33 cents of product. In India, the figure is 77 cents. Gradually climb and you get to $3 in Europe and then — in Japan — $5.55. China is poor not only because she wastes energy but water, too, while destroying her ecology in a way perhaps lacking any precedent. Figures such as these are very difficult to find: Mine come from researchers in the energy sector. Solving all of this, while making the skies blue, is a task of both extraordinary technical complexity and expense that will put China’s competing special interests at one another’s throats. Not solving, however, will doom China’s future. Allison may know this on some level, but you have to spend a lot of time in China and talk to a lot of specialists (often in Chinese) before the enormity becomes crushingly real.

What’s more, Chinese are leaving China in unprecedented numbers. The late Richard Solomon, who worked on U.S.-China relations for decades, remarked to me a few weeks before his death that “one day last year all the Chinese who could decided to move away.” Why? The pollution might kill your infants; the hospitals are terrible, the food is adulterated, the system corrupt and unpredictable. Here in the Philadelphia suburbs and elsewhere, thousands of Chinese buyers are flocking to buy homes in cash. Even Xi Jinping sent his daughter to Harvard. Does that imply a high-profile political career for her in China? Probably not. It rather implies a quiet retirement with Xi’s grandchildren over here. Our American private secondary schools are inundated by Chinese applicants. For the first time this year, my Chinese graduate students are marrying one another and buying houses here. This is a leading indicator. If it could be done, the coming tsunami would bring 10 million highly qualified Chinese families to the U.S. in 10 years — along with fleeing crooks, spies, and other flotsam and jetsam. Even Xi’s first wife fled China; she lives in England.

Allison, however, misses this; “immigration” is not in his index. Instead, he speculates about war, based on some superficial reading and sampling of the literature, coming to the question “What does Xi want?” — which I take as meaning that he thinks Xi’s opinion matters — which makes nonsense of the vast determining waves of economic development, not to mention his glance at Thucydides — with the opinion following that somehow we should try to find out what that is and cut a deal. This is geopolitics from a Harvard professor? This is the great wave of history?

How to conclude a look at so ill conceived and sloppily executed a book? Do not blame Allison. The problem is the pervasive lack of knowledge of China — a country which is, after all, run by the Communist Party, the police, and the army, and thus difficult to get to know. This black hole of information has perversely created an overabundance of fantasies, some very pessimistic, some as absurdly bright as a foreigner on the payroll can make them.

Forget the fantasies, therefore, and look at the facts. In the decades ahead, China will have to solve immense problems simply to survive. Neither her politics nor her economy follow any rules that are known. The miracle, like the German Wirtschaftswunder and the vertical ascent of Japan, is already coming to an end. A military solution offers only worse problems. My advice would be to skip Professor Allison and read instead the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights and recall that two of its handful of principal authors were not Europeans or Americans but rather Charles Malik of Lebanon and Peng-chun Chang of China, accomplished brother of the celebrated founder of Nankai University in Tianjin.

Perhaps not war, but cultural and political synergy, is what is, in fact, “destined.”

***

Source:

- Arthur Waldron, There is no Thucydides Trap, The China Project, 12 June 2017

***