Intersecting with Eternity

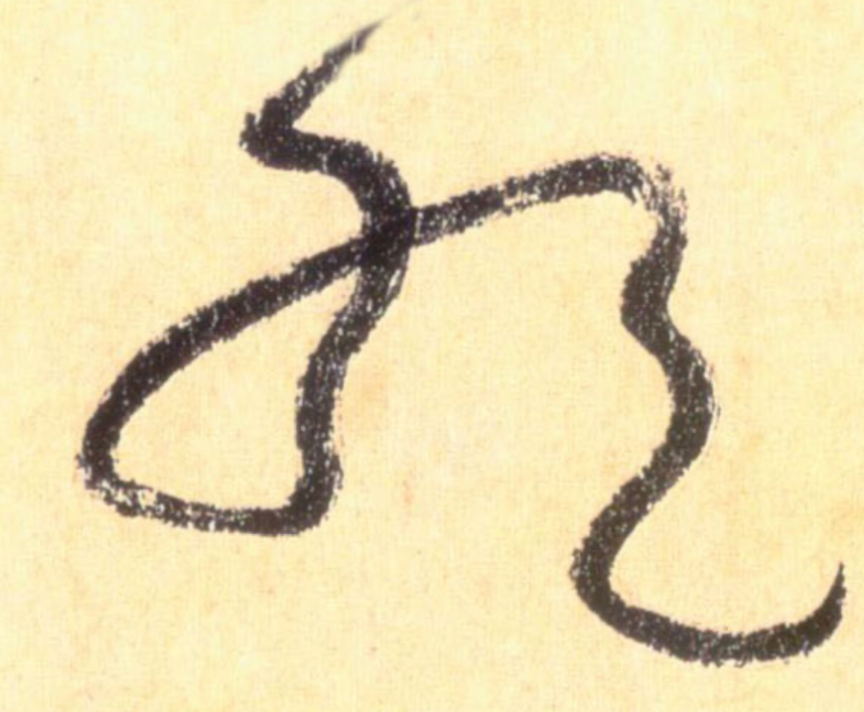

絕交

In the essay On Heritage we offered the Rationale behind China Heritage. We noted that the character 遺 yí — the leitmotif of our journal — in the hand of the Tang-dynasty artist Li Huailin 李懷琳 is taken from his grass-script 草書 version of a ‘Letter to Shan Tao’ 與山巨源絕交書, a famous epistle by Xi Kang, one of the celebrated Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove 竹林七賢. ‘In this letter’, Etienne Balazs tells us, one ‘written shortly before his death’,

Xi Kang broke off relations with his former friend Shan Tao, who had not kept his vow of uncompromising integrity, and who, after accepting a high post, had even dared to suggest that Xi Kang should become his assistant. Xi Kang, full of violent indignation, threw the offer back in his face, saying abruptly that his aspirations were not of this world, and explaining with such eloquence what Flaubert somewhere in his letters has expressed in the lapidary formula: Les honneurs déshonorent, le titre dégrade, la fonction abrutit.

Xi Kang (嵇康, also read ‘Ji Kang’, 223-262 CE) also tells his erstwhile friend that the ‘wayward’ ideas of Taoist sages had long influenced his predisposition to reject worldly office:

… My taste for independence was aggravated by my reading of Zhuangzi and Laozi; as a result any desire for fame or success grew daily weaker, and my commitment to freedom increasingly firmer. In this I am like the wild deer, which captured young and reared in captivity will be docile and obedient. But if it be caught when full-grown, it will stare wildly and butt against its bonds, dashing into boiling water or fire to escape. You may dress it up with a golden bridle and feed it delicacies, and it will but long the more for its native woods and yearn for rich pasture.

Like Xi Kang eighteen hundred years ago, our taste for independence was also aggravated by reading Laozi and Zhuangzi, among others; since then, the allure of golden bridles and delicacies has been but slight. Our aim in launching China Heritage in 2016, after long years spent in tertiary bonds, was to return to native woods and rich pasture. We did so by relocating to a small town in The Wairarapa, New Zealand, eight years ago this week.

***

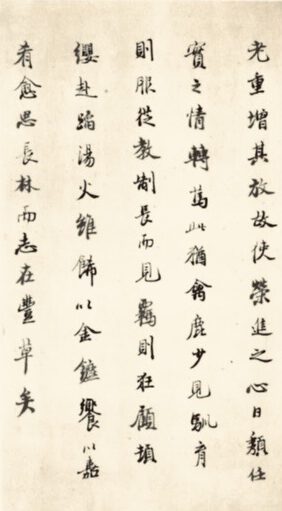

Below, we reproduce an excerpt from Xi Kang’s letter in the hand of Nara Singde (納蘭性德, 1655-1685). As Annie Ren 任路漫, a scholar of Chinese letters who is writing a biography of Singde, tells us that he is:

considered to be one of the greatest writers of ci-lyric 詞 poetry in the Qing dynasty. … [He] was twenty-one years old when he wrote this piece of calligraphy for Gao Shiqi (高士奇, 1645-1703), a Chinese scholar who gained imperial favour for his literary talent and calligraphic skills.

We are grateful to Annie for allowing us to include this material in our series Intersecting with Eternity, a mini-anthology of literary and artistic works, past and present, selected from the unbroken stream of human creativity and poetic self-reflection.

See also:

- Annie Ren, Wang Xi-feng’s Guide to Success in Modern China

- John Minford, Two Letters from The Stone

- John Minford with Annie Ren, Aisin Gioro Duncheng & Jottings from Four Pine Studio

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

30 August 2024

***

Also in Intersecting with Eternity

- A Note from The Tower of Reading on the Double Tenth 石如飛白木如籀

- A Solitary Pursuit — ‘… then begins a journey in my head’

So Starts the Spring - In Cloudy Mountains, an Impossible Realm

- An Ascension

- Kinship of the Soul

- Out of Range 彀外遺少

- Tao Yuanming — Substance, Shadow, Spirit 形影神

- Lao Shu — roaming through Tang-Song landscapes with my Wei-Jin brothers

- In my tear-wracked Solitude

- That Olive Tree in my Dreams

From The Tower of Reading

- ‘If this is what becomes of trees …’

- On the Spur of the Moment (and Inspiration & Taste — considering ‘On the Spur of the Moment’)

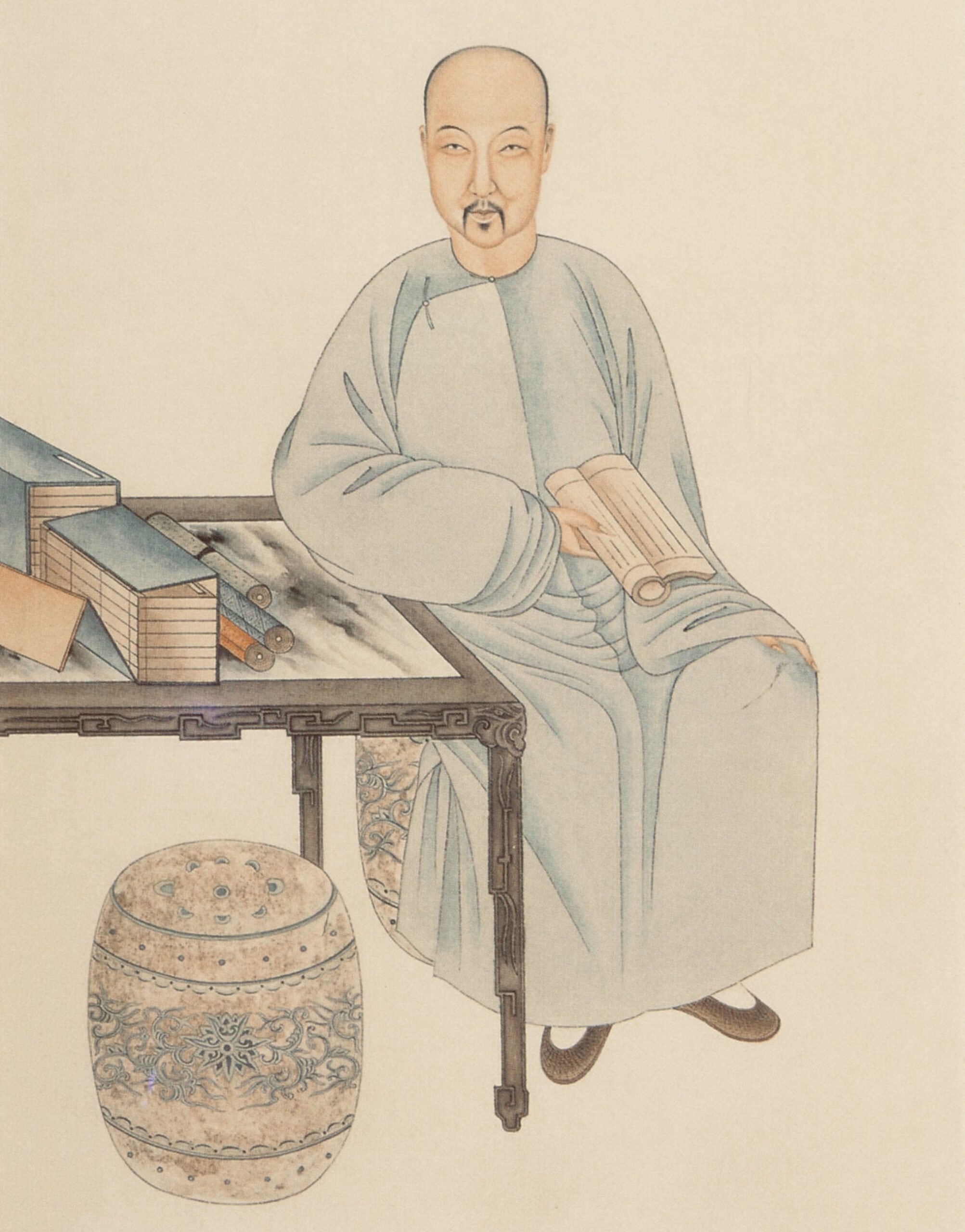

A nineteenth-century portrait of Nara Singde by Ye Yanlan (葉衍蘭, 1823-1897). Source: 清代學者像傳

***

***

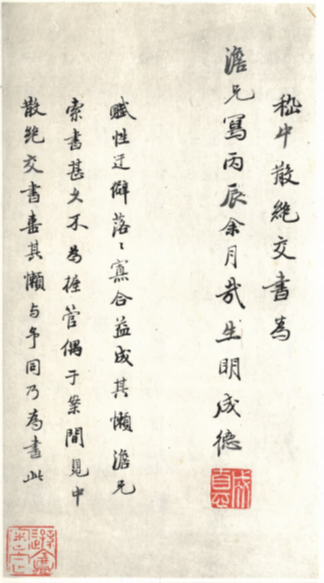

Xi Kang’s Letter to Shan Tao written for the perusal of Gao Shiqi at the start of the leap month of the Bingchen Year [1676]. Chengde [Singde]

Reclusive by nature, I’ve never been one to socialise. It’s something that has encouraged a certain indolence in me. Brother Dan [Gao Shiqi] has repeatedly urged for me to write out something for him, but I felt no particular urge to do so until I chanced upon this letter by Xi Kang. His brand of indolence resonates with me, that’s why I’ve copied his letter here.

嵇中散絕交書 為澹兄寫 丙辰余月哉生明 成德

賦性迂僻 落落寡合 益成其懶 澹兄索書甚久 不為握管 偶于案間見中散絕交書 喜其懶與予同 乃為書此

***

***

***

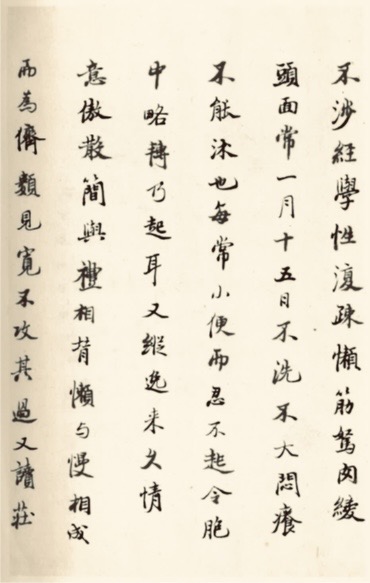

… I never took up the study of the Classics. I was already wayward and lazy by nature, so that my muscles became weak and my flesh flabby. I would commonly go half a month without washing my face, and until the itching became a considerable annoyance, I would not wash my hair. When I had to urinate, if I could stand it I would wait until my bladder cramped inside before I got up.

Further, I was long left to my own devices, and my disposition became arrogant and careless, my bluntness diametrically opposed to etiquette; laziness and rudeness reinforcing one another. But my friends were indulgent, and did not attack me for my faults.

Besides, my taste for independence was aggravated by my reading of Zhuangzi and Laozi; as a result any desire for fame or success grew daily weaker, and my commitment to freedom increasingly firmer. In this I am like the wild deer, which captured young and reared in captivity will be docile and obedient. But if it be caught when full-grown, it will stare wildly and butt against its bonds, dashing into boiling water or fire to escape. You may dress it up with a golden bridle and feed it delicacies, and it will but long the more for its native woods and yearn for rich pasture.

— translated by James Hightower

不涉經學。性復疏嬾,筋駑肉緩,頭面常一月十五日不洗,不大悶癢,不能沐也。每常小便,而忍不起,令胞中略轉乃起耳。又縱逸來久,情意傲散。簡與禮相背,嬾與慢相成,而為儕類見寬,不攻其過。又讀莊老,重增其放。故使榮進之心日穨,任實之情轉篤。此由禽鹿少見馴育,則服從教制,長而見羈,則狂顧頓纓,赴蹈湯火,雖飾以金鑣,饗以嘉肴,逾思長林,而志在豐草也。又讀莊老,重增其放。故使榮進之心日穨,任實之情轉篤。此由禽鹿少見馴育,則服從教制,長而見羈,則狂顧頓纓,赴蹈湯火,雖飾以金鑣,饗以嘉肴,逾思長林,而志在豐草矣。

On Nara Singde

Annie Ren

Nalan Xingde or Nara Singde (納蘭性德, 1655-1685) is considered to be one of the greatest writers of ci-lyric 詞 poetry in the Qing dynasty. Gu Zhenguan (顧貞觀, literary name 梁汾, 1637-1714), a famous ci poet from Wuxi and a close friend of Singde’s, describe his poems as being filled with ‘refined beauty and a sense of melancholy’ 婉麗淒清. Singde’s teacher, Xu Qianxue (徐乾學, 1631-1694), nephew of the renowned scholar Gu Yanwu (顧炎武, 1613-1682), described his calligraphic hand as ‘vigorous and free-flowing’ 遒逸, noting that it was modelled on Chu Suiliang’s 褚遂良 traced version of the ‘Preface to the Orchid Pavilion Poems’ 禊貼, as well as the internal section of the Yellow Court Scripture 黃庭內景經, the originals of both of which were in the hand of Wang Xizhi 王羲之 (see below for Singde’s thoughts on calligraphy).

[China Heritage note: see Duncan Campbell, Orchid Pavilion: An Anthology of Literary Representations, China Heritage Quarterly, No. 17, March 2009.]

Nara Singde was twenty-one years old when he wrote this piece of calligraphy for Gao Shiqi (高士奇, 1645-1703), a scholar-official who enjoyed imperial favour for his literary talent and calligraphic skills. Gao is best known for the personal account he wrote about his travels with the Kangxi Emperor, including two excursions to the Imperial Hunting Lodge at Jehol, in 1681 and 1683 respectively, as well as a three-month journey across the Manchu homeland in 1682. Serving in the imperial bodyguard, Singde also accompanied the emperor on these expeditions.

Despite Singde’s insistence on his laziness, biographical accounts written by his friends after his sudden death at the age of thirty paint him as a voracious reader and diligent servant of the Throne. Friends noted that he would attend Court from the crack of dawn and leave only when the evening drum were sounded. He devoted his leisure time to his studies, his concentration unbroken during both the sweltering Beijing summer and the bitter winter. When accompanying the Emperor on his travels, Singde would:

Hunt during the day and read by lamp light in the evening. The sound of him reading could be heard amidst the insistent snoring of his fellow men.

日則校獵,夜必讀書,書聲與他人鼾聲相和。

In 1682, Singde was sent on a secret military mission to investigate Russian imperial defences in the Amur region. Led by the Manchu generals Langdan and Pengchun, the mission traversed the barren desert surviving only on the supplies they carried with them. To map out the waterways that intersected with the Sungari River 松花江, the envoys also rode on ice for days at a time. Singde’s friend Jiang Chenying 姜宸英 recalls that:

Though the journey had been full of danger and hardship, upon his return, Singde pulled out stacks of paper from his pouch. On them, written in fine characters, were poems containing sketches of local produce, customs and the landscape. Oblivious to his haggard looks, he showed these poems to his friends, much to their delight.

君雖跋涉艱險,歸時從奚囊傾方寸札出之,疊數十紙,細行書,皆填詞若詩,略記其風土方物。雖形色枯槁不自知,反遍示客,資笑樂。

Singde’s greatest regret, according to Jiang Chenying, was that he could not live like Xi Kang or other members of the Bamboo Grove society, to ‘roam freely among the mountains and rivers, indulging in poetry and wine without any restraints’ 放浪山水,跌宕詩酒,無所拘束.

Despite his noble status (his father, Mingju 明珠, was a powerful official, and his mother was the granddaughter of Nurhaci, the founding father of the Manchu-Qing empire), Singde rarely consorted with prominent courtiers. Instead, he counted as his close friends ‘dejected and hard-up scholars who refused to abandon their principles in exchange for worldly success’ 困鬱守志不肯脫俗之士. The most notable example of this was his cross-generational friendship with Gu Zhenguan (mentioned earlier), a man who was eighteen years his senior. Though a highly respected poet, Gu’s attempts to gain political influence in Beijing all ended in failure, but this did not prevent Singde from regarding him as a bosom friend. In a poem to Gu Zhenguan , composed within days of their first meetings, the twenty-one year old Singde vowed eternal friendship. His pledge was widely acclaimed in the capital:

By nature a mad scholar,

By chance born in a rich family,

I have been stained by the dust of the court.

But my heart is with the heroes of Zhao,

Wishing to sprinkle their tombs with all my wine!

How could I expect anyone to know this heart of

mine?

And yet you, O my bosom friend, have seen

through me!

You and I are both young,

And both take to song and wine.

Before the cups how many tears we have shed,

Sympathetic tears for the poor and down-trodden!

See how the moonlight liquefies in our eyes!

德也狂生耳。

偶然間、緇塵京國,烏衣門第。

有酒惟澆趙州土,誰會成生此意。

不信道、竟逢知己。

青眼高歌俱未老,向尊前、拭盡英雄淚。

君不見,月如水。

Let us drink our fill tonight!

Let the garrulous women backbite!

Now as before, gossip is their sole delight!

Worry not over the vicissitudes of our floating life.

Or else we will be regretful from

The very beginning of our lives!

Leave everything to Fate with a cold smile!

The bond between our hearts will survive

All the Cycles of Existence!

The entanglements of our next life

Already tied up in our former incarnations.

Still let’s not forget our wows

We’ve made today!

共君此夜須沉醉。

且由他、蛾眉謠諑,古今同忌。

身世悠悠何足問,冷笑置之而已。

尋思起、從頭翻悔。

一日心期千劫在,後身緣、恐結他生裏。

然諾重,君須記。

— this is a slightly modified version of 金縷曲(贈梁汾), translated by John C.H. Wu and published in Renditions: Special Issue on Tzu, nos.11 & 12 (Spring & Autumn 1979): 258-259

***

On Calligraphy

Nara Singde

Calligraphy is an obsession of mine. As I see it, the quality of calligraphy lies not in the ability to imitate the Old Masters, but in one’s innate talent. This is because calligraphy arises from a moment of inspiration and not through conscious, deliberate effort. The Zuo Commentary states that ‘People’s hearts are as different as their faces’. The Jin dynasty general Huan Wen was greatly pleased when people said he looked like Liu Kun, but Liu Kun’s old maidservant observed otherwise.

[She said:

Your eyes might be similar, but yours are unfortunately too small. Your face has a likeness, but yours is pointy; your beards are very similar, though sadly yours is red and, though your body shapes have something in common, unfortunately your are short. As for your voices, there is a similarity, unfortunately yours has an effeminate timbre.

眼甚似,恨小。面甚似,恨薄。須甚似,恨赤。形甚似,恨短。聲甚似,恨雌。]

This is also true of calligraphy. If I were to assemble one thousand skilled calligraphers in a room and examine their handwriting, none of their handwriting will be identical. If I were to gather one thousand unskilled calligraphers, their handwriting will also be different from one another. If there could only be one style of calligraphy, then we only need one master like Wang Xizhi for the eternity. Even though Wang Xizhi studied under Lady Wei, in the end, Lady Wei’s style remained hers, and Wang Xizhi’s style remained his own. Likewise, those who imitate Wang Xizhi’s ‘Preface to the Orchid Pavilion’ will interpret his brushwork and intent differently. The spirit of calligraphy will die if everyone simply reproduces original as faithfully as possible.

Wang Shaozong [circa. seventh century] once said,

When I write, I always purposely empty my mind, and let my brush flow naturally. I heard that Yu Shinan never practiced by imitating ancient masters, he writes on his stomach with his fingers while lying in bed, and I do the same.

Su Shi also remarked,

My calligraphy is not bound by any method. Indeed, the extraordinary skills of the ancients are heaven-sent, inspired by the moment, their brush moves naturally with the heavens without conscious awareness. Whenever I find myself in possession of fine ink and brushes, sometimes, without deliberate intention, I might produce a satisfying stroke. Otherwise, the more I strain and force myself to write, the worse my writing becomes.

As for Chen Yi’s idea that one must be reverential when using the brush—a view that reflects his Confucian mindset—that has nothing to do with the art of calligraphy.

Ancient masters of calligraphy would draw inspiration from such disparate things as a sword dance, the burbling of a flowing river, or a snake in combat. None have anything to do with writing, yet, inspiration can be found everywhere.

I have often observed that, if once has truly mastered the texts of Mencius and Zhuangzi, you will be able to appreciate the essence of calligraphy. Through the ages, who among you can grasp the meaning of my words? I have composed this reflection on calligraphy for those who mistakenly pride themselves on pursuing a mere ability to imitate the Ancients.

— translated by Annie Ren

原書

予篤好書,每謂書有天分,而非盡關乎仿傚;書有興會,而不必出乎矜持。《傳》云:人心不同,有如其面。桓溫欲似劉琨,而琨婢以為甚似而非。予謂惟書亦然。聚千百能書之人於此,其筆跡無一同。聚千百不能書之人於此,其筆跡亦無一同。使必出於同,則千古書法,止一右軍足矣。即如右軍學衛夫人,而究之衛自衛、王自王。臨蘭亭者,亦各自見筆意也。若銖而較,寸而合,豈復有真面目耶。王紹宗曰:我書每精心空思,率意而成。聞虞世南不臨摹,但被中書肚,我亦如之。坡公云:我書意造本無法,蓋古人絕技,必有神明所寓,興會所觸,動與天隨而不自知。予每當筆硯精良時,或無意中有得意之筆。否則不但掣肘迫書,即稍一勉強,而愈作愈不佳。程子所云作字須敬,此亦儒者持心語,而書法豈關此哉。古之能書者,或觀劍器,或聽江聲,或見蛇鬥,此豈有書之事哉。然而會心有在矣。予嘗謂熟讀蒙莊,即可悟作書之理。悠悠千古,解吾語者誰也。予恐書家之涉仿傚矜持者,有鸚哥驕秦吉了之誚,故作書原。

***