The Tower of Reading

乘興而行,

興盡而返。

In this chapter of The Tower of Reading we focus on a well-known anecdote found in New Tales of the World 世說新語. Wang Huizhi’s impulsive behaviour also provides us with a pretext to discuss some ideas that lie at the heart of an abiding Chinese tradition of quirkiness, taste and individuality.

***

Contents

(click on a section title to scroll down)

***

Preface

The Tower of Reading is a series inspired by the work of Zhong Shuhe (鐘叔河, 1931-), one of the most influential editors and publishers in post-Mao China and a writer celebrated in his own right both as a prose stylist and as an interpreter of classical Chinese texts.

The full title of the series — ‘Studying Short Classical Chinese Texts with The Master of The Tower of Reading’ — is our interpretive translation of 念樓學短 niàn lóu xué duǎn, the enticingly lapidary name under which Zhong Shuhe published over five hundred newspaper columns over three decades (see 念樓學短2002年 and 念樓學短2020年). The short title for this endeavour in China Heritage is simply The Tower of Reading.

Each chapter features a short Classical Chinese text of under 100 characters which Zhong translates into modern Chinese. To these Zhong appends ‘A Comment from the Master of the Tower of Reading’ 念樓曰 niàn lóu yuē, ‘casual essays’ — 小品文 xiǎopǐnwén or 雜文 záwén, both modern terms for such works that are akin to the traditional terms 筆記 bǐ jì, ‘jottings’ or 劄記 zhá jì, ‘miscellaneous literary notes’ — that expanded on the theme of the chosen text, or a particular historical figure or a particular incident. Often, Zhong’s comments are whimsical reflections on his life.

The Tower of Reading in China Heritage offers translations of the classical texts and of Zhong Shuhe’s interpretive essays along with the original Chinese versions of both.

For more on the background to this project, see Introducing The Tower of Reading.

***

This chapter is the eighth of eleven selections from New Tales of the World 世說新語, ascribed to Liu Yiqing (劉義慶, 403-444 CE). This famous and popular fifth-century selection of anecdotes, stories and witticisms is known in English translation as A New Account of the Tales of the World.

Previously, in ‘If this is what becomes of trees …’, we introduced New Tales of the World with a short essay by Richard Mather, the scholar who translated the full text of that work. Here we introduce the tradition of reclusion, or escape from the world and we do so by drawing on the work of a number of translators and scholars.

This chapter is divided into two parts. Part One, below, focusses on three anecdotes related to Wang Huizhi (王徽之, 338-386 CE) and Part Two, published separately, offers an extended discussion of the cultural, linguistic and historical context of these anecdotes. In particular it focusses on the ‘word-constellations’ 興 xīng and 趣 qù.

The sense of 興 xīng — ‘impulse, rising, inspiration’ — lies at the heart of the anecdote that Zhong Shuhe selects and discusses here. As we will see, however, this layered term also describes a form of creative resonance. In ‘The Qualities of Poetry’ 詩品, Zhong Rong (鍾嶸, ?-518 CE) offers that 興 xīng refers to the kind of meaning hinted at beyond the limits of any given text 文已盡而意有餘,興也。

In Part Two, we also investigate the multiple dimensions of 趣 qù, a term that Zhong Shuhe uses at the end of his short comment on Wang Huizhi’s impulsiveness. The literary scholar David Pollard observes that, among other things, 趣 qù ‘is related to behaviour which is natural, apt, unreflecting, unselfconscious, unforced and free; it comes from following the inner promptings of one’s nature, or from being as one is.’ What better description could there be of Wang Huizhi ‘visiting Dai Kui on a snowy night’ 雪夜訪戴 in the fourth century?

***

I am grateful to Annie Ren 任路漫, a specialist in late-dynasty Chinese literature, who suggested translating some of Zhong Shuhe’s selections from New Tales of the World. Apart from translating Zhong Shuhe’s short comment on Wang Huizhi which features below, Annie also proposed including the material in the section titled ‘A Poem, the Recluse and a Saying’. We introduce that section with a painting by Xiang Shengmo and a poem by Dong Qichang taken from the catalogue for The Artful Recluse: Painting, Poetry, and Politics in Seventeenth-Century China, an exhibition held at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art in 2012. My thanks to Duncan Campbell for introducing me to that exhibition and for loaning me his copy of the catalogue.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

10 April 2024

***

Reference Material:

- 劉義慶著,世說新語,中國哲學書電子化計劃,full Chinese text

- Shih-shuo Hsin-yü: A New Account of Tales of the World, by Liu I Ch’ing, with commentary by Liu Chün, translated with introduction and notes by Richard B. Mather, 2nd ed., Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2002

- David Hawkes, The Age of Exuberance, in Classical, Modern and Humane, John Minford and Siu-kit Wong, eds, Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press, 1989, pp.306-308, reproduced with permission in China Heritage

- Peter C. Sturman and Susan S. Tai, eds, The Artful Recluse: Painting, Poetry, and Politics in Seventeenth-Century China, Santa Barbara Museum of Art, 2013

- Graham Sanders, Words Well Put: Visions of Poetic Competence in the Chinese Tradition, Harvard University Press, 2016

Also by Annie Ren:

- Wang Xi-Feng’s Guide to Success in Modern China

- A Profile, a Reverie & a Letter

- ‘If this is what becomes of trees …’

***

‘When the moment has passed’

While Wang Huizhi was living in Shanyin [modern-day Shaoxing, Zhejiang] one night there was a heavy fall of snow. Waking from sleep, he opened the panels of his room, and, ordering wine, drank to shining whiteness all about him. Then he got up and started to pace back and forth, humming Zuo Si’s [左思, d.306] poem, ‘Summons to a Retired Gentleman’ 招隱詩:

Propped on a staff I go to summon the retired gentleman,

Where weed-grown paths connect the then and now.

In the cliff cave there is no edifice;

Amid the mountains, only his singing zither.

While snow remains on the shadeward ridge.

Vermillion blooms blaze in the sunward grove.

杖策招隱士,

荒塗橫古今。

岩穴無結構,

丘中有鳴琴。

白雪停陰岡,

丹葩曜陽林。

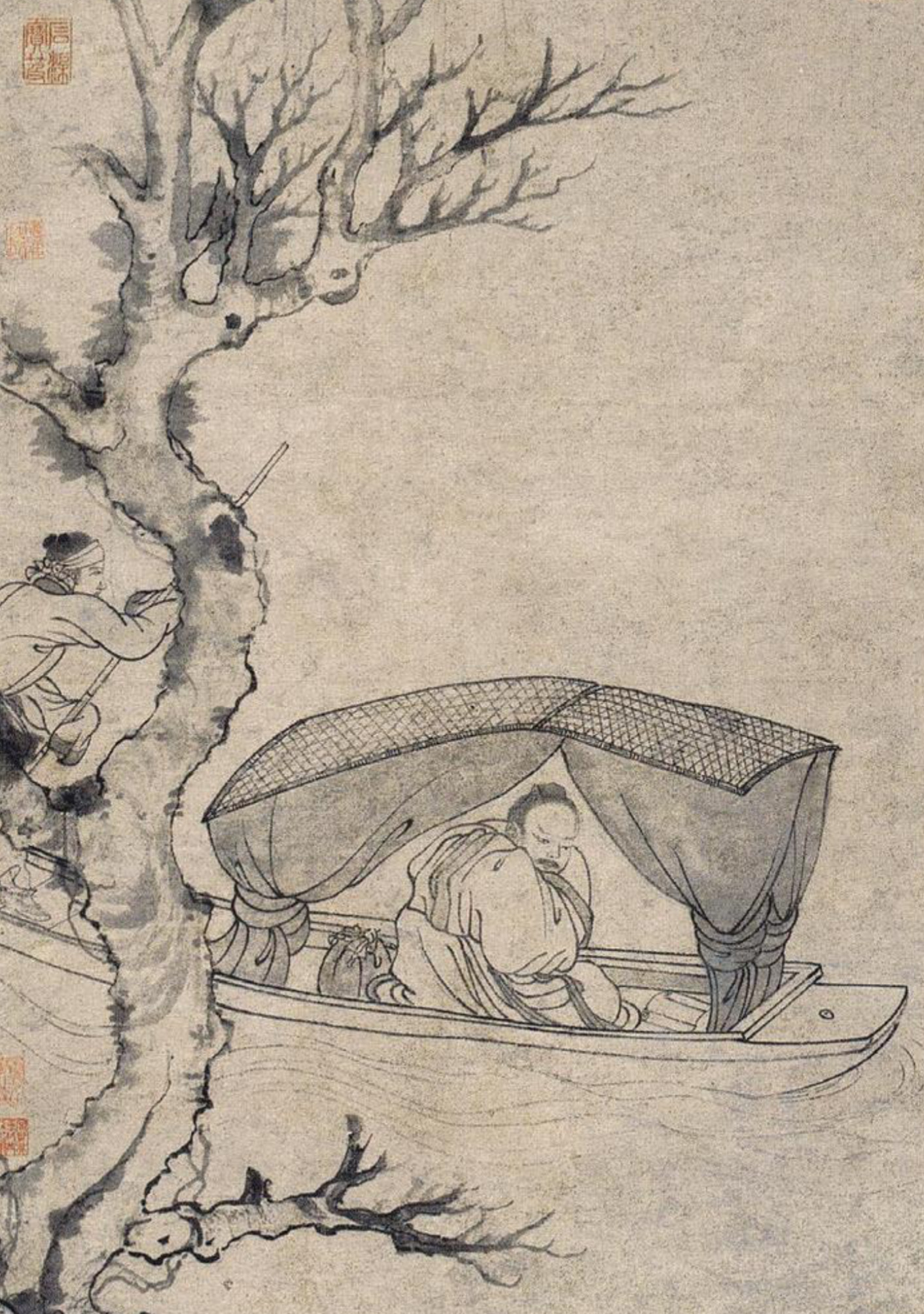

All at once he remembered Dai Kui [戴逵, c.331-396 CE], who was living at the time in Shan [south of Shanyin]. On the spur of the moment he set out by night in a small boat to visit him. The whole night had passed before he finally arrived. When he reached Dai’s gate he turned back without going in.

When someone asked his reason, Wang replied,

‘I originally went on the strength of an impulse, and when the impulse was spent I turned back. Why was it necessary to see Dai?

— translated by Richard B. Mather, A New Account of Tales of the World, p.389, with minor modifications

雪夜訪戴 劉義慶

王子猷居山陰。夜大雪,眠覺,開室,命酌酒,四望皎然。因起彷徨,詠左思招隱詩。忽憶戴安道。時戴在剡,即便夜乘小船就之。經宿方至,造門不前而返。人問其故。王曰,吾本乘興而行,興盡而返,何必見戴。

A Comment from The Tower of Reading:

It is slightly dismissive to include this episode of Wang Huizhi’s life (王徽之, 338-386 CE) in ‘The Free and Unruly’ 任誕 section of A New Account of Tales of the World. Actually, Wang’s quirky behaviour was simply a reflection of the zeitgeist of the Wei-Jin period.

- [Mather translated the section title 任誕 rèn dàn as ‘The Free and Unrestrained’, eliding thereby the somewhat dismissive tone of the original. — AR]

In a time of chaos and disunity, where the Confucian rites and laws have collapsed, scholars finally felt as though they were free to think and behave according to their natural propensities. It was an era in which people felt that they could act according to impulse and speak in a manner that was not circumscribed by the reactions of others, especially the power-holders.

There were a scant few moments in Chinese culture like this — the Wei-Jin period; the Northern-Southern dynasties (220-589); the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms (907-965); and also the Late Ming (1573-1644).

I find some of the individuals from those periods quite fascinating and their words and deeds quite thought-provoking even today.

— translated by Annie Ren

[Editor’s Note:

The pivotal term in this anecdote is 興 xīng, ‘to be inspired’, ‘on the spur of the moment’, ‘impulse’. In the last line of his commentary, Zhong Shuhe also employs the expression 趣味 qùwèi, ‘to be of interest’, ‘beguiling’, ‘fascinating’. In Part Two of this chapter, we elaborate on the history and cultural resonances of these deceptively simple yet significant words.

In Modern Chinese, 雪夜訪戴 xuě yè fǎng dài is a common idiom, or 成語 chéng yǔ, that means ‘to act impulsively’, ‘as the fancy takes you’ or ‘on a whim’.]

***

Source:

- Chapter Eight in Section Fourteen of Studying Short Classical Chinese Texts with The Master of The Tower of Reading 《念樓學短·世說新語之八》,長沙:岳麓書社,2022年,上冊,第312-313頁。

***

Original Chinese Text

學其短:The selected Classical Chinese text;

念樓讀:Zhong Shuhe’s translation into Modern Chinese; and,

念樓曰:Zhong Shuhe’s comment.

乘興

雪夜訪戴 劉義慶

王子猷居山陰。夜大雪,眠覺,開室,命酌酒,四望皎然。因起彷徨,詠左思招隱詩。忽憶戴安道。時戴在剡,即便夜乘小船就之。經宿方至,造門不前而返。人問其故,王曰。吾本乘興而行,興盡而返,何必見戴。

【學其短】

- 本文錄自《世說新語·任誕》。

- 山陰,今紹興。

- 左思,晉代詩人,其《招隱詩二首》見《文選》卷二二。

- 戴安道,名逵,東晉隱士。

- 剡,剡溪,為曹娥江上游的一支,附近曾置剡縣,故址在今嵊州市西南。

【念樓讀】 王子猷住山陰的時候,有個冬天的晚上忽下大雪。他睡一覺醒來,推開臥房的門,叫家人送酒來喝。忽見屋外四處雪色又白又明,興致勃發,便不想睡了,在屋內走來走去,一面朗誦起左思的《招隱詩》來:

杖策招隱士,荒塗橫古今。

岩穴無結構,丘中有鳴琴。

白雪停陰岡,丹葩曜陽林。……

又因“招隱”想起了隱居在剡溪的友人戴安道,立刻叫人備條小船,冒著大雪乘船前往。小船搖到剡溪,天已大明。船一直搖到戴家的門口,這時子猷又不想進門了,叫船掉頭,仍走原路回家。

後來有人問子猷為什麼這樣做,他說:“我是趁著當時的興致上船的,興致滿足了,也就可以打轉了,何必一定要見到什麼人呢。”

【念樓曰】王子猷這件事,《世說新語》歸之于“任誕”門,略有貶意,其實它也只是魏晉風度的一種表現。在大一統瓦解、禮法崩壞之際,讀書人的思想解除了束縛,個性得以張揚,才有可能“乘興”做一做想做的事情,說一說想說的話,不必太顧及別人會如何看,尤其是執政者會如何看。魏晉南北朝、五代十國和明之末世,便是文化歷史上這樣的時期,我以為其中有些人事頗有趣味,亦可發深思。

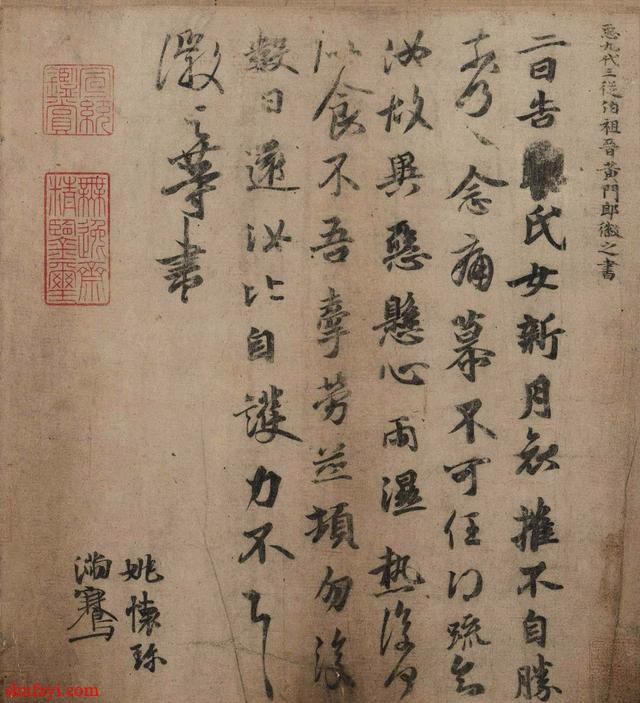

One of the early admirers of Xiang Shenmo’s landscape scroll on the theme of reclusion wrote:

‘The mountains are high, the valleys are beautiful. The forests are green and breezes caress the robes. The man does not look back and very much has an air of transcendence. What exactly is this painting?’ I [Xiang] replied, ‘Because I read the poems on the invitation to reclusion by Lu Ji and Zuo Si I was very much inspired and painted this piece as an accompaniment.’

山高溪秀,林翠撲衣,人不回顧,甚有超逸之風.此何圖也。曰:因讀陸機,左思招隱詩,有興于懷,將補是圖。

— from The Artful Recluse: Painting, Poetry, and Politics in Seventeenth-Century China, Peter C. Sturman and Susan S. Tai, eds, Santa Barbara Museum of Art, 2013

The admirer was none other than Dong Qichang (董其昌, 1555-1636), a noted calligrapher and controversial Ming-dynasty official, whose life and career skirted the issue of reclusion since, for a time, he was forced from office.

***

A Poem, the Recluse and a Saying

The poem by Zuo Si quoted by Wang Huizhi in the above is one of two poems that Zuo composed on the theme of reclusion. Here we offer the full text of the first of those poems along with a translation. Following a comment on the poet and the well-known expression associated with him, we quote a passage from Graham Sanders whose Words Well Put is a rare example of recent scholarship that discusses New Tales of the World in a manner that is both unaffected and judicious.

— Ed.

Summoning the Recluse

招隱詩

Zuo Si 左思

Leaning on my staff, I summon the recluse,

Since ancient times this wild road has lain here.

The cave in the crags is bare of criss-cross beams,

But among these hills is the sound of a singing lute.

White snow still lies on the mountain’s shadowy side,

Red petals flare on the sunny side of the woods.

A stony spring washes over precious jade,

Delicate fishes are swimming in its depths.

No need of strings, or bamboo instruments,

When mountains and waters give forth their pure notes.

Why bother now to whistle or to sing,

When bushy trees are humming mournfully?

Autumn chrysanthemums are food enough for me.

The lonely orchid I wear as a buttonhole.

My feet are tired from all this pacing about,

I would like to throw my hat-pins clean away.

杖策招隱士,

荒塗橫古今。

巖穴無結構,

丘中有鳴琴。

白雲停陰岡,

丹葩曜陽林。

石泉漱瓊瑤,

纖鱗或浮沉。

非必絲與竹,

山水有清音。

何事待嘯歌,

灌木自悲吟。

秋菊兼餱糧,

幽蘭間重襟。

躊躇足力煩,

聊欲投吾簪。

— trans. John Frodsham

[Note: Here ‘hatpins’ 簪 zān, also ‘hairpin’ or ‘clasp’, refers to bureaucratic insignia.]

Zuo Si (d.306) was renowned above all as a writer of rhapsodies 賦 fù. His trilogy, ‘The Rhapsodies of Three Capitals’ 三都賦, is a masterpiece that was so widely copied out when it appeared that the price of paper in Luoyang was said to have risen as a result. That episode was soon encapsulated in the four-word idiom 洛陽紙貴 Luòyáng zhǐ guì, literally, ‘paper in Luoyang is expensive’, a formulaic expression, or 成語 chéng yǔ, that is still in currency. It is now used to describe something that is fashionable, widespread or valuable.

***

Zuo Si’s Poem and Wang Xianzhi

Graham Sanders

The only mention of snow in the poem is found in the first line of the third couplet, which, with its mention of “shady ridge” and “sunny grove,” does not apply very well to Wang’s nocturnal surroundings. And this seems to be the point. There is no anxiety on Wang’s part (nor should there be on the part of the reader) about making his performance suit the occasion. There is no need to bridge the gap between the conditions of the poem’s origination and its current application. It is simply enough that snow lies on the ground outside and that snow is mentioned in the poem—a happy coincidence that requires no further justification. Yet out of this happy coincidence another impulse is generated that moves Wang to action. As the speaker of the poem, he decides to emulate the speaker in the poem by going to “summon the recluse”: his friend Dai Kui. The narrative underscores the spontaneity of this impulse by stating that Wang’s friend “suddenly came to mind” and that “he set out at once on a small boat to visit him.” …

The very poem that provides the text for Wang’s performance, Zuo Si’s “Summoning the Recluse,” is traditionally read as an exhortation made to a talented man who has chosen reclusion over service to an unworthy government. Wang chooses the poem for its aesthetic dimension, pointedly ignoring its “original” meaning and application. Both Wang and Dai are already in service; they adopt the label “recluse” provisionally, with a knowing wink, to describe their leisure time spent in natural surroundings.

— from Classical Chinese Literature: An Anthology of Translations, John Minford and Joseph S.M. Lau, eds., New York: Columbia University Press, 2002, p.436 and Graham Sanders, Words Well Put: Visions of Poetic Competence in the Chinese Tradition, Harvard University Press, 2006, pp.153-155

***

Two More Anecdotes about Wang Huizhi

Wang Huizhi (王徽之, 字子猷), the fifth son of the calligrapher Wang Xizhi 王羲之, had a reputation as an eccentric and undisciplined character who never took seriously the minor official posts he occupied. He loved poetry and the company of the bamboo that he cultivated in his mountain retreat at Shanyin in Zhejiang. He was known to be particularly fond of his younger brother, Xianzhi 王獻之, and died only a short time after him.

The following are two other anecdotes about Wang Xianzhi from ‘The Free and Unruly’ 任誕 section of A New Account of Tales of the World:

Wang Huizhi was once temporarily lodging in another man’s vacant house, and ordered bamboos planted. Someone asked, ‘Since you’re only living here temporarily, why bother?’ Wang whistled and chanted poems a good while; then abruptly pointing to the bamboos, replied, ‘How could I live a single day without these gentlemen?’

王子猷嘗暫寄人空宅住,便令種竹。或問:暫住何煩爾。王嘯詠良久,直指竹曰:何可一日無此君。

[Note: For more on bamboos, see Duncan Campbell, When Bamboo Invites a Zephyr, China Heritage.]

Wang Huizhi once came out of retirement to the capital and his boat was still moored by the banks of the Blue-green Stream. He had long known that Huan Yi [桓伊, a well-known military commander,] was skilled at playing the transverse flute [笛] but had never made his acquaintance. It happened that Huan was passing by along the shore while Wang was in the boat. One of the passengers, recognizing him, said, ‘It’s Huan Yi’. Wang immediately had someone convey his greetings, saying, ‘I hear you’re skilled at playing the flute. Might you play for me?’

Huan was already distinguished and famous at the time, but since he, too, had long been aware of Wang’s reputation, he immediately turned around and dismounted from his carriage, and, sitting informally on a folding stool [胡床], played three tunes for him. When he had finished playing, he immediately remounted his carriage and departed. Neither guest nor host exchanged a word.

王子猷出都,尚在渚下。舊聞桓子野善吹笛,而不相識。遇桓於岸上過,王在船中,客有識之者云:是桓子野。王便令人與相聞云:聞君善吹笛,試為我一奏。桓時已貴顯,素聞王名,即便回下車,踞胡床,為作三調。弄畢,便上車去。客主不交一言。

— adapted from Robert Mather’s translation

***

Looking for the Recluse and Not Finding Him

尋隱者不遇

Jia Dao 賈島

Beneath the pines I asked his servant boy,

Said, “The master’s gone off picking herbs;

He’s somewhere on this mountain,

But the clouds are so thick I can’t tell where.”

松下問童子,

言師採藥去。

只在此山中,

雲深不知處。

— translated by Stephen Owen