Studying Short Classical Chinese Texts with

The Master of The Tower of Reading

念樓學短

Dedicated to Zhong Shuhe

in celebration of Dai Qing and

in memory of Huang Yongyu, Yang Jiang & Qian Zhongshu

***

Contents

(click on a section title to scroll down)

***

Preface

The Tower of Reading is a series published by China Heritage focussed on the work of Zhong Shuhe (鐘叔河, 1931-), one of the most influential editors and publishers in post-Mao China and a writer celebrated in his own right both as a prose stylist and as an interpreter of classical Chinese texts.

The full title of the series — ‘Studying Short Classical Chinese Texts with The Master of The Tower of Reading’ — is our translation of 念樓學短 niàn lóu xué duǎn, the enticingly lapidary name under which Zhong Shuhe published over five hundred newspaper columns over three decades (see 念樓學短2002年 and 念樓學短2020年).

Each selection features a short text of under 100 characters which Zhong translated into modern Chinese. To these Zhong appended ‘A Comment from the Master of the Tower of Reading’ 念樓曰 niàn lóu yuē, ‘casual essays’ — 小品文 xiǎopǐnwén or 雜文 záwén, modern terms for such works, akin to the traditional terms 筆記 bǐ jì, ‘jottings’ or 劄記 zhá jì, ‘miscellaneous literary notes’ — that expanded on the theme of the chosen text, or a particular historical figure or a particular incident. In these musings Zhong wryly remarks on human foibles, offers readers short meditative passages, reflections and amusing aperçu. For the most part, they reflect on his experiences during the Mao era when, like so many other men and women of letters, he had been persecuted, although his often acerbic comments also touch on contemporary life. Taken together, Zhong’s essay-commentaries offer a wry account of modern Chinese culture, thought and society.

For nearly three decades, from 1991 to 2020, Zhong Shuhe published hundreds of essays that drew upon the vast corpus of China’s written tradition. Each essay took as its theme a short classical text no more than 100 Chinese characters in length which Zhong then translated and interpreted for modern readers. In a foreword to a selection of the essays dated 4 June 2002, Zhong described his three-part approach in the following way:

- 學其短 xué qí duǎn is ‘the selection and study of short works by the ancients’ 學的是古人的文章;

- 念樓讀 niàn lóu dú offers ‘my reading [translation] of the selected text in modern Chinese’ 我對古人文章的「讀」法; and,

- 念樓曰 niàn lóu yuē, an impromptu commentary, ‘remarks for the diversion of my readers for which I, rather than the ancients, am solely responsible’ 再借題「曰」 上幾句,只能給想看的人看看,文責自負,不能讓古人替我負責。

[Note: For an example of this format and Zhong Shuhe’s style, see The Same Fair Moon 千里共嬋娟, 29 September 2023.]

***

Zhong’s Tower of Reading is constructed from divers sources, ranging from the first millennium BCE to the late-nineteenth century. They include the writings of thinkers like Confucius, Mencius and Zhuangzi, canonical historical material, both formal and casual literary compositions from famous writers, including Su Shi, Han Yu and Zhang Dai, as well as selections from various genres of writing, such as introductions, letters and informal notes. The process of selection overlaps with a tradition in Chinese letters summed up in the expression 文史哲 wén-shǐ-zhé — the literary, historical and philosophical tradition — a familiarity with which equips students, be they Chinese or not, with a basic appreciation of the kind of ‘comprehensive knowledge’ that is so deeply admired in China. In this, The Tower of Reading in approach, temper and style, chimes with our own advocacy of New Sinology (for more on this, see Jao Tsung-I on 通 tōng — 饒宗頤與通人; and, China Watching in the Xi Jinping Era of Blindness and Deafness).

Taken as a whole, The Tower of Reading is also something of a commentary on China, one written by a littérateur imbued both by the ethos of China’s dual enlightenments (1917-1927 and 1977-1989) and the long tradition of what Republican-era writers like Zhou Zuoren and Lin Yutang championed as Chinese humanism. Through his translations, Zhong Shuhe helps readers appreciate the originals, which were more often than not in a terse telegraphic style that can easily elude the modern reader. And in his commentaries, he is reflecting on his own life as well as addressing a future that, as he hints between the lines, is less ideologically hidebound than the present.

Although the short classical texts that Zhong selected are at the heart of the series, his commentaries, written in the tradition of the best modern essayists, are a singular achievement.

***

The Tower of Reading series itself replicates in a modest way the efforts of Zhong Shuhe who, from his elevated perspective, both literally and metaphorically, has surveyed a corpus of China’s recorded tradition and selected short prose pieces. The embracing view from The Tower of Reading is in stark contrast to The View from Maple Bridge, a four-part chapter in the series Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium.

This introduction is paired with ‘Intersecting with Eternity’, itself a selection of works that reflect our own understanding of the fragile skein between ideas, sentiment, literature and us. The Tower of Reading is nothing less than a laissez-passer into the Invisible Republic of the Spirit.

The Tower of Reading is a stand-alone section in China Heritage listed under Topics in the Menu Bar. Some of its contents will also feature both in Lessons in New Sinology and in The Other China. Although the focus of the series will be on Zhong Shuhe’s work, other essays, translations and artwork that relate to the theme of reading and thinking through time will also be included.

***

In late 2014, I bought a small two-volume selection of Zhong Shuhe’s a selection of Short Classical Texts from The Tower of Reading 念樓學短 titled Read Ancient Books with Me 帶你讀古書 in Beijing. Taking advantage of a lull between chemo- and radio-therapy following cancer surgery earlier in the year, I had gone to Beijing to see friends, buy books and enjoy what I thought would most probably be my last trip to a city where I come to study forty years earlier. Reading Shuhe’s selected classical texts and his sardonic essays, I decided that if I survived the cure of my illness, I would turn my attention to this unpretentious yet unique work.

After quitting academia in late 2015, my energies were focussed instead on moving to New Zealand and launching China Heritage. Then, in 2021, my long-delayed interest in The Master of The Tower of Reading was revived when my old friend Dai Qing suddenly got in touch from Changsha, Hunan province. She was visiting Zhong Shuhe in hospital, where he was recovering from a stroke and my name had come up in conversation. Dai, never one to prevaricate, immediately sent me some photos of the two of them together (and another with Zhu Zheng). Shuhe also instructed his assistant to scan some of the letters that I had written to him after our first meeting in 1981. I mentioned how much I admired Short Classical Texts and so he asked Dai to send me the latest two-volume edition. Due to Covid restrictions, it took over a year for the books to reach me. As soon as they did, thanks to the help of Wang Zhaohui in Beijing and her sister Wang Ziyin in Melbourne, I began planning The Tower of Reading.

With the encouragement of my old friend Duncan Campbell, the leading collaborator in this project, I am launching The Tower of Reading on this first day of the 2024-2025 Year of the Dragon. It is dedicated to Zhong Shuhe and to Dai Qing. I am also taking this opportunity to celebrate the connection between Huang Yongyu, who introduced me to Zhong Shuhe in 1981, myself and Yang Jiang and Qian Zhongshu, both of whom played a role both in my work and in that of Zhong Shuhe.

***

The first series of Short Classical Texts appeared in the form of newspaper columns in 1991 under the title ‘studying short pieces [of prose]’ 學其短 xué qí duǎn. An initial collection was published in Hunan in 2002 and again in Anhui in 2004. An expanded edition in five short volumes was produced by Hunan Arts Publishing House in 2010. The series was reissued in 2018 in a two-volume set containing 530 chapters arranged under fifty-four headings.

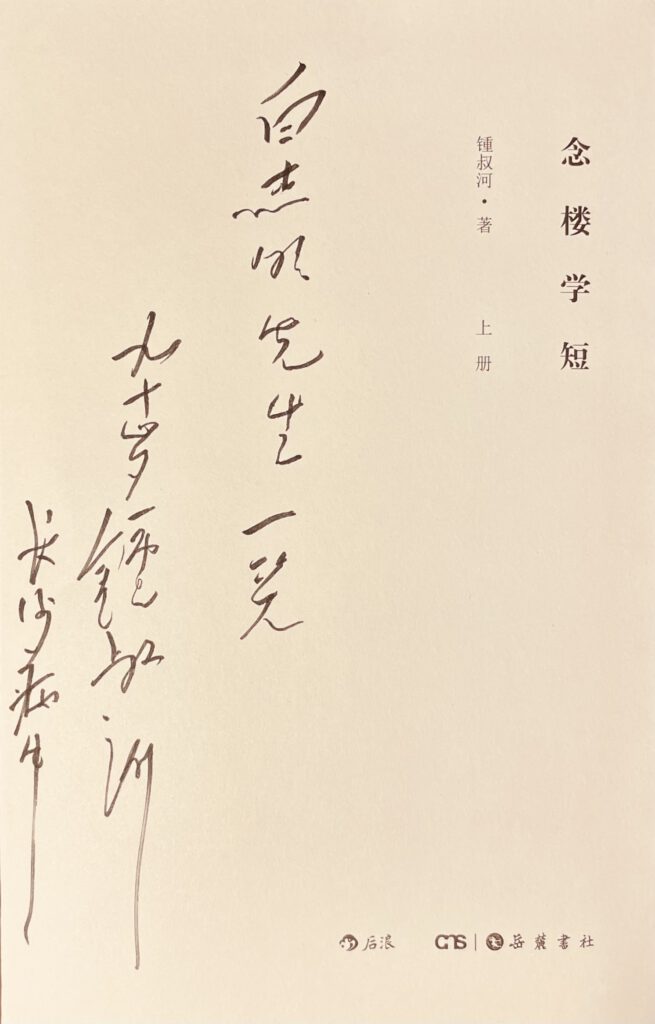

The Tower of Reading in China Heritage uses the two-volume edition of 念樓學短 published by Yuelu Publishing House 岳麓書社 in Changsha, Hunan province in 2020. The copy I use was a gift from Zhong Shuhe, signed on his sickbed.

***

Today, as we embark on the Year of the Dragon, we are changing the masthead of China Heritage so as to reflect the style and temper of The Tower of Reading. The Temple, a photograph by Lois Conner, replaces Mount Lu, also by Lois Conner, which was the visual leitmotif of Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium. For the background to The Temple, see The Temple & the Mastheads of China Heritage, 2016-2024.

My thanks to Reader #1, Duncan Campbell and Lois Conner for agreeing to cast an eye over this material. The remaining blemishes are a reflection of my own inadequacies.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

10 February 2024

The First Day of the First Month of

The Jiachen Year of the Dragon

甲辰龍年正月初一

***

Note:

This introduction to The Tower of Reading is one of four interconnected essays. The other three are:

- Why Read The Tower of Reading?

- An Irrealis Mood — The Empire of Tedium seen from The Tower of Reading; and,

- Intersecting with Eternity

These essays in turn frame a short anthology of works selected to reflect the theme of The Tower of Reading. That anthology that will be published intermittently along with chapters from Zhong Shuhe’s work.

***

On the style of Chinese characters used in The Tower of Reading:

The Tower of Reading originally appeared as a series of newspaper articles which were set in the Simplified Chinese Characters 簡體字 jiǎn tǐ zì imposed by Beijing throughout the People’s Republic of China (bar Hong Kong). To accord with the in-house style of China Heritage, we have converted those ‘Crippled Characters’ 殘體字 cán tǐ zì to traditional orthography, known variously as Full-form/ Complex Characters 繁體字 fán tǐ zì or Traditional Characters 正體字 zhèng tǐ zì.

***

Related Material:

- A Note from The Tower of Reading, 10 October 2023

- 湘籍學者鐘叔河回憶與楊絳交往30年,長沙晚報,2016年5月26日

- 鐘叔河回憶與楊絳交往三十載 往來書信曝光,鳳凰網,2017年5月25日

- 如何評論鐘叔河的《念樓學短》?,知乎,2019年7月15日

- 再登念樓,訪鐘叔河先生,搜狐,2020年3月19日

- 寂寞、懷疑、無知,所以讀書 | 鐘叔河,鳳凰網,2022年5月24日

- 老先生,編輯鐘叔河:他引領一代中國人“走向世界”,澎湃新聞,2022年9月2日

On YouTube (in Chinese):

- Zhong Shuhe in conversation with Xu Zhiyuan, 許知遠對話鍾叔河 難道能夠不「走向」它而走出它嗎?,《十三邀》 第六季第9期, 油管,2023年3月10日

- Zhang Xingdong 張興東, Thirty Chapters from The Tower of Reading, YouTube, 2022. Select episodes: 王顧左右; 何待來年; 未間然君他(暴君可殺); and, 惠子謂莊子(無用之用)

Encountering Zhong Shuhe

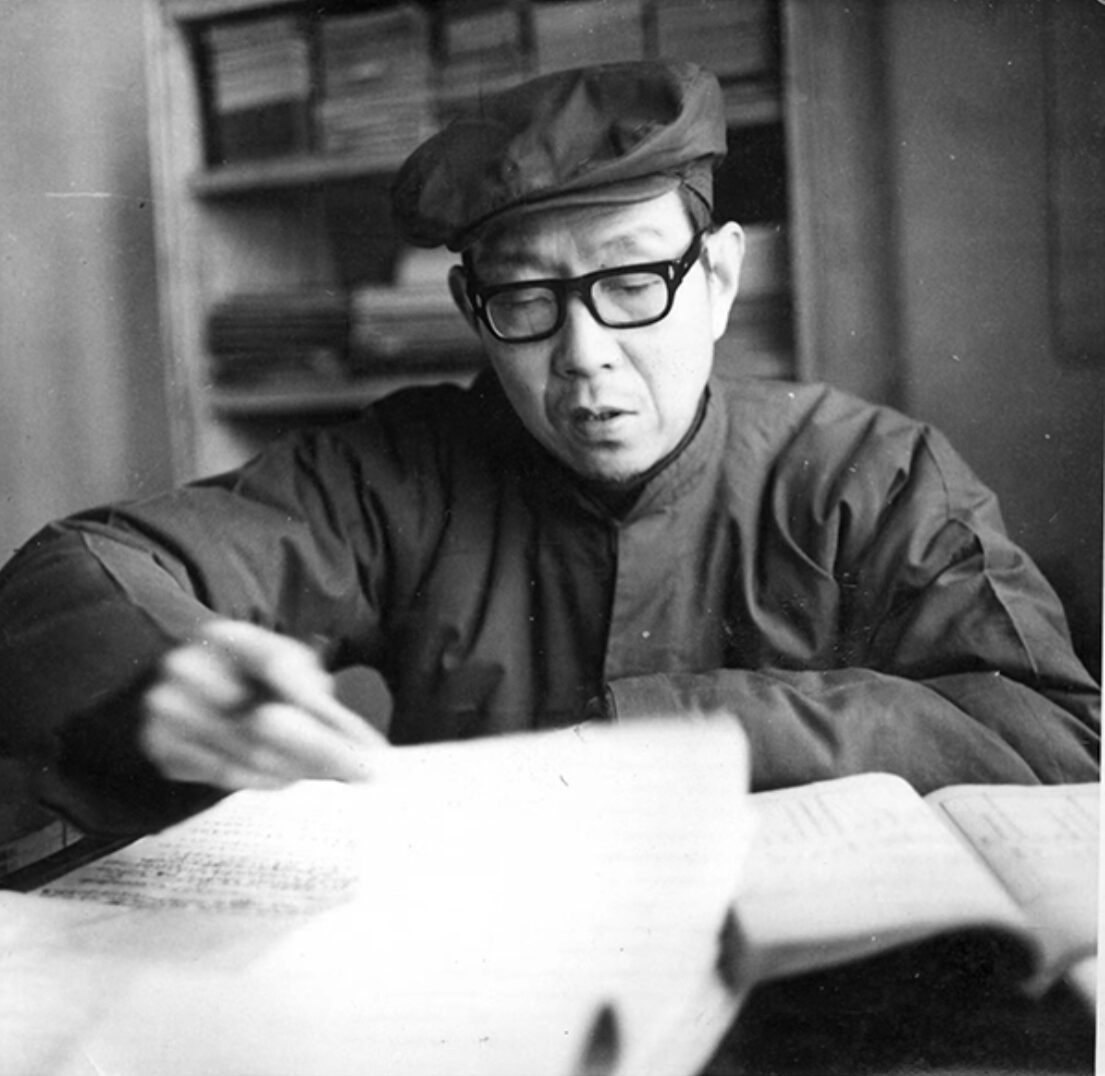

Zhong Shuhe in The Tower of Reading. This photograph dates from around the time we first met in Changsha, the provincial capital of Hunan, in the summer of 1981.

***

In the summer of 1981, the artist Huang Yongyu 黃永玉 wrote me a letter of introduction to Zhong Shuhe 鐘叔河. I had only recently met Yongyu, a noted artist, essayist and raconteur, at the apartment of Gladys and Yang Xianyi 杨憲益 in Beijing. At the time I was working on a translation of Lost in the Crowd 幹校六記, a Cultural Revolution memoir by the translator and writer Yang Jiang 楊絳. Yang and her husband, the academic Qian Zhongshu 錢鍾書, also encouraged me to meet Zhong Shuhe, a man who was fast gaining a reputation as an energetic and creative editor in the south. In turn, Zhong Shuhe introduced me to Zhu Zheng 朱正.

Apart from their formal employment, both men had only recently returned to public life after decades of political persecution. Zhong would play a role in helping China recuperate aspects of its forgotten history and lost culture and Zhu Zheng, apart from his work on the literary paragon Lu Xun, went on to become the leading chronicler of the Anti-Rightist Campaign, the 1957 purge of the country’s intellectual and cultural life from which the People’s Republic has never recovered.

Huang Yongyu was a proud native of Hunan and he took every opportunity to promote people, products and places in the province. He was enamoured by ‘Going Out to the World’ 走向世界叢書, a series of books launched in 1980 edited by Zhong Shuhe. The volumes included accounts of the outside world and travel diaries written by late-Qing-dynasty officials, the stories of the first students to study in the West, essays and notes on Japan, Asia and Europe by diplomats, business people and travellers. Previously unknown to Chinese readers, these books offered a view of China and the world from the Tongzhi Restoration era of the 1860s, through the Self-strengthening Movement and the years of frustrated reform before the eventually collapse of China’s last imperial dynasty in 1911.

Zhong’s selections were inspired and his timing flawless. In late 1978, China had disavowed the inward looking radicalism of the Mao-Liu decades (1949-1978) and the Communist Party launched reforms that in some respects were a revival and continuation of the failed restoration policies of the late Qing.

[Note: For more on this, and the relationship between ‘dynastic revival’ 中興 zhōngxīng, the reforms of the Deng era and the revanchism of Xi Jinping, see Prelude to a Restoration: Xi Jinping, Deng Xiaoping, Chen Yun & the Spectre of Mao Zedong.]

Over the years, the series ‘Going Out to the World’ swelled to dozens of volumes all of which were selected, edited and published by Zhong Shuhe. A landmark in contemporary Chinese publishing history, the series was also a constant reminder to readers — including academics, theorists and the politically engaged — of the circuitous way the country had travelled in its quest for ‘wealth and power’.

[Note: See 明鵲,丁超逸, 葛蓓兒,老先生,編輯鐘叔河:他引領一代中國人“走向世界”,澎湃新聞,2022年9月2日.]

My circle of friends in Beijing and Hong Kong were also enthusiastic about Zhong Shuhe’s work. Qian Zhongshu wrote a preface for the series and the editor Pan Jijiong 潘際坰 in Hong Kong featured it in the arts pages of Ta Kung Pao, for which I wrote a regular column in Chinese. Yang Xianyi, who was now finally enjoying some of the respect and authority as China’s leading English translator along with his wife Gladys Yang, was also interested in exploring the possibility of selecting some of Zhong’s books for inclusion in Panda Books, a Penguin-like venture of translated titles published by the Foreign Languages Press in Beijing.

Zhong Shuhe was also a key figure in the revival of Republican-era writers and works that had been banned and denounced for over three decades. As one of a number of tenacious editors who would help China rediscover the lost voices of moderation, sense and humanity silenced by the shrill slogans of revolution his work thus chimed with my own burgeoning interests in the silenced voices of important cultural figures like Zhou Zuoren, Lin Yutang and Feng Zikai. (See An Artistic Exile: A Life of Feng Zikai (1895-1975), 2002.) In particular, Shuhe championed the case of Zhou Zuoren, brother of Lu Xun, a leading modern essayist who has been cast aside because of his wartime collaboration with the Japanese occupation in Beijing.

Today, in the second decade of Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium, it is hard to recapture the excitement, curiosity and yearning for discovery of the early 1980s. I treasure my memories of those years, as I do my contact with Zhong Shuhe and many of his admirers.

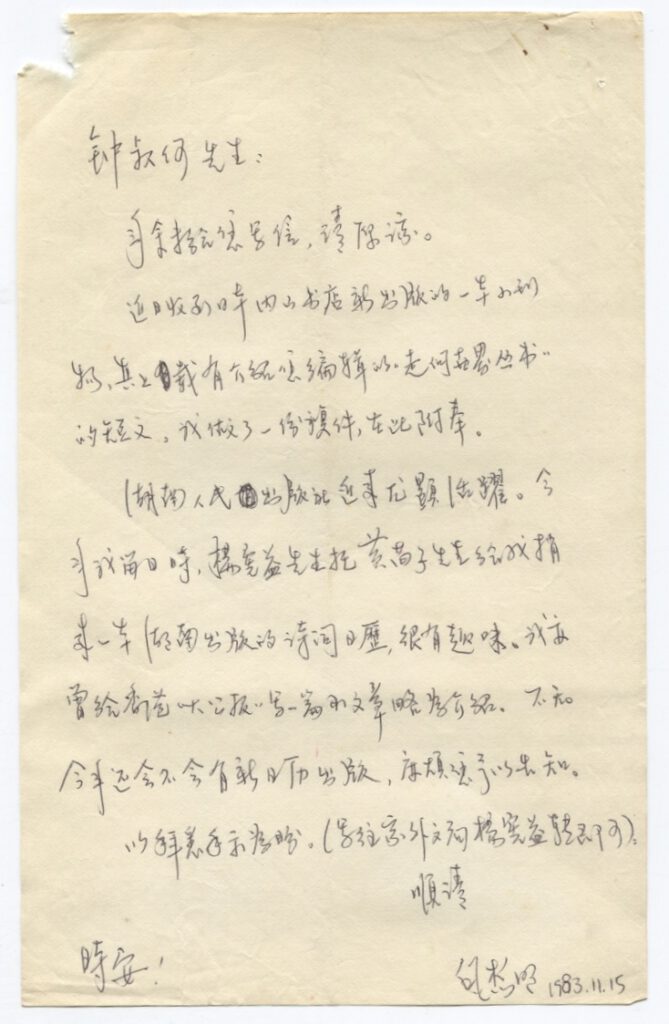

Over the years, we exchanged letters; I kept our correspondence in my files and, in 2022, I was delighted to learn from Dai Qing that Shuhe also had my letters to him:

Dai Qing, who had known Zhong Shuhe for about as long as she had known me, was visiting the long-retired publisher in Changsha. He was in hospital following a stroke and, for some reason they had ended up talking about me. Dai, who was always irrepressibly enthusiastic, immediately sent me a photo of them together. Shuhe also asked her to send me photos of some of my letters in his archive. At their joint request, I wrote another note and, at my request Shuhe signed a copy of the latest two-volume edition of Studying Short Classical Chinese Texts with The Master of The Tower of Reading:

The Timeless Studio

In a centuries-old tradition, Zhong Shuhe named his study, or personal studio 書齋 shū zhāi — ‘The Tower of Reading’ 念樓 niàn lóu. It is a homophone for 廿樓 niàn lóu, ‘the twentieth floor’, a reference to Zhong’s apartment on the twentieth floor of a building in the residential compound of the Hunan Publishing Conglomerate, formerly Hunan Publishing House, where he worked for many decades. More prosaically, 念樓 niàn lóu simply means ‘the twentieth floor’. In English we have chosen to call it ‘The Tower of Reading’ and, following tradition, we think of Zhong Shuhe as The Master of the Tower of Reading 念樓主人.

***

On the Modern-day Creative Studio

齋 zhāi, 芸窗 yún chuāng,

書齋 shū zhāi, 書房 shū fáng

Today’s studio can have many forms, or none. At one extreme, at its most abstract, it can be the formless studio of the mind, the personal universe that surrounds the individual, furnished and imbued with that person’s favourite words, images, tunes, fabrics, vibrating with their unique scent and aura. It can be present, or past, or both, or neither. We all create and recreate our own studios, every minute of every day. To a greater or lesser extent, we may share them, or we may lock ourselves away, maintaining them as bastions of privacy in an increasingly public world. We open and close the studio doors. These studios are an extrusion of our selves; they are of us, but do not belong to us. As Liang Shiqiu remarked, ‘I don’t own my cottage; I am merely one of its tenants.’

Today’s studio, and the constantly shifting heritage of those scholar’s studios of old, may be something as banal as a laptop computer, that most versatile of modern mobile studios, seated at which the writer feels at home and creates home (wherever or whatever that may be). A less electronically-minded individual, like the peripatetic Hong Kong writer Leung Ping-kwan 梁秉君 (a present-day practitioner of the perennial art of biji wenxue [筆記文學]), carts his personal studio around with him more literally in a rucksack, like a snail’s shell, trundling bundles of unfinished manuscripts and unanswered letters from port to port (and often losing them during his explorations, in particular in such unreliable ports as Marseille!), resting from time to time to scribble a post-card or two in a makeshift studio/café (for example, in a Prague sidestreet, which then becomes an intrinsic part of the literary product, ‘Postcards from Prague’), or pausing in some bar down a dark alley to catch breath, to celebrate the moment with a motley group of friends in this their temporary home.

His is a genuine perpetuation of the timeless and quintessentially Chinese (but strangely universal) world of the studio-picnic, the meeting of true and like minds, the sharing of hard-won identities, the celebration of a fragile community, fighting off the dark, struggling to conjure away the ever encroaching barbarism of our age with a few poignant phrases.

It’s late at night now. Outside the streets are empty and desolate. But we can still sit here, we can still linger awhile amid the lights and voices, drunk on the illusion of this warm and joyous moment. (From Leung’s story ‘Postcolonial Affairs of Food and the Heart’.)

— from John Minford, ‘The Scholar’s Studio zhāi 齋’

China Heritage Quarterly, March 2008

***

***

Zhong Shuhe’s Tower of Reading

The following section is based on the introductions that Zhong Shuhe wrote for various editions of his series from 2002 to 2018. I have reworked the material into a short narrative to which the original texts are appended. Extrapolations based on my reading of Zhong Shuhe’s prefaces are solely my responsibility.

First, however, we offer a few paragraphs from an introduction that Zhong Shuhe wrote for a selection of Classical Texts from The Tower of Reading published in 2023. — GRB

‘Selected classical texts compiled by Zhong Shuhe, a nonagenarian publisher. Study the lapidary prose of the ancients as you imbibe their wisdom. Advance into the future in the company of tradition.’

九旬出版家鍾叔河先生精選文言短篇合集;學習古文的簡約,汲取古人的智慧,於傳統中走向未來

— publisher’s promotional tag for Remarkable Writing:

Selections from The Tower of Reading, Beijing 2023

The original print run for Classical Texts from The Tower of Reading was 6000 copies and over the past two decades some 200,000 copies of later editions of the book have been produced. In total, I selected 530 short classical texts of under 100 characters each, drawing material from the pre-Qin era [before the second century BCE] right up to the early years of the Republic in the twentieth century. My selection was eclectic and I included passages from the Confucian classics, traditional histories, bureaucratic documents right up to works of fiction, miscellaneous writings as well as epistles and diaries. I thought of my audience as including anyone who is interested in reading accessible classical texts as well as those who want to hone their own writing skills. All descendants of the Yellow Emperor have the right to read and to write, that even includes a duty to express themselves.

The criterion I’ve applied to selecting Classical Texts from The Tower of Reading was that the selections had to be succinct and well written. Brevity itself makes them even more easy to read [念 niàn], or for that matter to recite out loud [唸 niàn]. Their charms are self-evident, moreover they have passed the test of time and will continue to do so.

The inscription on an ancient tripod, Confucius on the subject of ceaseless change, Liu Bang’s Three Stipulations, Qian Liu’s plea to his wife — they are all famous works that people have committed to memory and recited through the ages. They have also all played a role in the social life of their times. Although none of their authors were regarded as being writers as such, their works enjoy the undying appeal of literature, both in style and content.

Zhong Shuhe, aged 92

Changsha, Hunan province

23 July 2022

— from Remarkable Writing: Selections from The Tower of Reading

絕妙好文:念樓學短選讀,北京:人民文學出版社,2023年

《念樓學短》初版六千部,二十年來,兩卷本和五卷本共計已印行二十多萬部,收百字古文五百三十篇,作者從先秦正考父到民國章炳麟,文體從經史公文到小說雜誌到書信日記,讀者則是一切願意讀點古文、願意學寫文章的人——這本來就是黃帝子孫應享的權利和應盡的義務。

《念樓學短》收的是傳統的好文章,好的首要標準就是短。因為短,所以好讀,好背誦,好欣賞,能傳世。正考父《鼎銘》,孔子「在川上曰」,劉邦「約法三章」,錢鏐請夫人「緩緩歸」,都是千古傳誦的名篇。它們寫作時各有社會功能,它們的作者從未被定位為文學家,但它們都具足了人文之美——內容的美和形式的美,也就是具足了文學性。…

二千零二十二年七月二十三日於長沙,時年九十二歲。

***

During the summer months of 1989 after the political cataclysm that had rocked Beijing and sent seismic shockwaves throughout China, Zhong Shuhe decided to lose himself in his study, The Tower of Reading. Delving deep into the world of classical Chinese letters, Zhong compiled a volume of short, accessible texts for the education, and entertainment, of his grandchildren. He likened his meandering through the vast corpus of the past and his composition of explanatory essays to the writer Lu Xun’s efforts to distract himself from the dire political situation of his own day. In the 1910s, Yuan Shikai, president of the Republic of China and a military strongman, had thrown the nation into chaos when he declared himself founding emperor of a new dynasty.

At the time, Lu Xun, the pen name of Zhou Shuren (周樹人, 1881-1936), was working for the Ministry of Education and was lodging at the Shaoxing prefectural guild hall in the capital. As Yuan pursued his imperial plans, government agents scoured the city identifying and arresting opponents to what was widely regarded as a betrayal of the republican revolution of 1911. To avoid suspicion, Lu Xun let it be known that in his spare time he was focussing on collecting and studying rubbings of the inscriptions on old stone stelae.

Later celebrated for his contributions to epigraphy, Lu Xun surreptitiously continued to pursue his interest in contemporary culture and politics. As he copied out the texts on ancient stelae, he composed Diary of a Madman, which is regarded as China’s first and most famous modern short story.

The significance of Zhong Shuhe’s reference to Lu Xun was unmistakable. As he put it in Preface Six to his book, dated 10 June 2006: 抄錄短文加以介紹的工作,事實上是從一九八九年夏天開始的,說是為了課孫,其實也有一點學周樹人躲進紹興縣館抄古碑的意思。

‘In the blink of an eye, two decades have passed,’ Zhong went on to say. ‘When I started this project I was approaching my sixth decade, now I’m nearly in my eighth.’ 一眨眼二十年過去,我已從「望六」進而「望八」。He wistfully adds:

‘I will not live to see the Yellow River run clear and my heart swells with emotion’ 俟河之清, 人壽幾何,真不禁感慨系之。

That is to say, he held out no hope that there would be any significant political change in China in his lifetime. Now, in the first half of the 2020s, Zhong Shuhe is in his nineties and Xi Jinping has only just embarked on his second decade in office.

In regard to how his project had evolved so that he felt free to extemporise on contemporary Chinese life, Shuhe tells us in Preface Six, dated 10 June 2009, that:

I conceived of this series as a way to introduce readers to short classical texts. However, over time, my own explanations and elaborations on the topics at hand grew in length; they outgrew the succinct originals and ended up taking up most of the space of each entry. Nonetheless, I would observe that at best I’d give my contributions — written with all due sincerity though they may be — a score of 60 out of 100.《念樓學短》的本意,當然是為了向古人學短,但寫的時候,就題發揮或借題發揮的成分越來越多,很大一部分都成了自己的文章。我的文章頂多能打六十分,但意思總是誠實的。

In the introduction to selections from The Tower of Reading that had previously been published in the Beijing press, Shuhe had written that:

Even if my own additions are not particularly outstanding, at least they are relatively short. It saved time and energy for all concerned and I thought that was a beneficial contribution.’

He went on to say, ‘I was being quite sincere because I really don’t think that I am a particularly good writer. I was always worried about rabbiting on unnecessarily.’ After all, he continued:

Since I advertised the series as being aimed at ‘Studying Short Classical Texts’, I couldn’t very well betray my own brief. Even if that meant that I’d make less money out of the venture, at least I spared myself the kind of ridicule suffered by Old Lady Wang and her bound feet [the foot bindings of which were notoriously ‘smelly and too long’].

《學其短》幾年前在北京報紙上開專欄時,序言中說:「即使寫不好,也可以短一些,彼此省時省力,功德無量。」這當然是有感而發。因為自己寫不好文章,總嫌囉唆拖沓,既然要來「學其短」,便不能不力求其短,這樣稿費單上的數位雖然也短,庶可免王婆婆裹腳布之譏焉。

— from Preface Two, 10 December 1998

In Preface Three, dated 11 June 2001, Shuhe muses that:

‘Studying Short Classical Texts’ is something that the literati regard as being beneath contempt and which academics also find distasteful. I, however, have found great satisfaction in this undertaking. I lack the talent required to write at length; anyway, I’m generally put off by those pretentious works that deal with topics deemed to be ‘so important that length is no object’. Brevity was at least my original aim although over time I’ve come to realise that whether reading a text or evaluating a person, the same standards apply. Height and looks are not that important; attraction lies in the depth of thought, the substance of the individual and their general conviviality.

Originally, I selected these classical texts with an eye to giving my granddaughters something to read. At university, however, none of them pursued the humanities. So, I’m no longer providing a service to anyone in particular, nor am I all that interested in translating short excerpts from classical texts into modern Chinese. That’s why I decided to add new wine of my own to these very old bottles [in the form of short expository essays]. Rather, I would observe that that my new wine is very much the same wine of the ancients, and it is still faithfully contained in their original bottles. What is different is that in my ‘Tower of Reading’ is that, apart from my ‘reading’ of the texts [in the form of 念樓讀], I also comment on them [in essays in the form of 念樓曰].

I derive considerable pleasure from what I do or, as Tao Hongjing put it long ago: ‘Would that I could share with you my delight in watching the scudding clouds’. I should hesitate to extrapolate [on the themes of the selected texts] too liberally, but once I get going it is hard to rein myself in.

我自己對於古文今譯這類事情其實並無多大興趣,於是便決定在舊瓶中裝一點新酒。——不,酒還應該說是古人的酒,仍然一滴不漏地裝在這裡;不過寫明「念樓」的瓶子里,卻由我摻進去了不少的水,用來澆自己胸中的壘塊了,即標識為「念樓讀」尤其是「念樓曰」的文字是也。

這正像陶弘景所說的,「只可自怡悅,不堪持贈君」。借題發揮雖然不大敢,但箭在弦上不得不發時,或者也會來那麼兩下吧。

Again, as he says in Preface Five, dated New Year’s Day 2004:

‘Translating classical texts into modern Chinese’ is not the main appeal of this undertaking. It is being able to write about how I respond to those texts. The hundreds of texts that I have selected for this series provide a pretext for my reflections. In an age of prosperity such as ours there is, theoretically at least, no good reason to find a pretext to indulge one’s musings. However, the desire to slake one’s thirst with the spirits of the ancients is surely something that not even the most saintly can ignore.

Yet, since it’s about ‘studying short pieces of prose’, and since I’m mindful of the reader, I do my best not to mis-read these texts, or at least not to misconstrue them too much. Fidelity is a constant concern, although I must admit that there are cases when, for example, I might find it hard to avoid translating a dynastic-era term like ‘being exiled from the court’ [貶謫] as ‘being sent down to the countryside’ [下放]. People have pointed out to me that ‘to be exiled from the court’ was one way that the authoritarians of the past punished men of talent, while being ‘sent down’ by the Communist Party and the People’s Government was a positive policy aimed at training cadres. It is, therefore, inappropriate to equate the two. But, as I see it, in both cases people who had been at the top were sent to the bottom, moved from the centre out to the periphery. The only difference was that there was no way a person could disobey an imperial command and they meekly submitted to their exile while those ‘sent down’ in the modern era were packed off amidst the clamorous beating of drums and gongs with big red paper flowers pinned to their chests. As a result, I write about things like that as the mood takes me without getting too bogged down.

可是我的主要興趣卻不在於「今譯」,而是讀之有感,想做點自己的文章。這幾百篇,與其說是我譯述的古文,不如說是我作文的由頭;雖說太平盛世無須「借題發揮」,但借古人的酒杯,流關中的金塊,大概也還屬於「夫人情所不能止者,聖人弗禁」的範圍吧!

當然,既名「學其短」,對「學」 的對象自然也要尊重,力求不讀錯或少讀錯。在這方面,自問也是盡了力的,不過將「貶謫」釋讀成「下放」的情況恐仍難免。雖然有人提醒,貶謫是專制朝延打擊人才的措施,下放是黨和人民政府培養幹部的德政,不宜相提並論。但在我看來,二者都是人從「上頭」往「下頭」走,從「中心」往「邊緣」挪。不同者只是從前聖命難違,不能不「欽此欽遵」克期上路;後來則有鑼鼓相送,還給戴上了大紅花,僅此而已。於是興之所至,筆亦隨之,也就顧不得大多了。

Appendix: Chinese Texts

Allow me to avail myself of a line from Zheng Banqiao [the Qing-era scholar-bureaucrat and artist]:

‘If there’s anything worthwhile here, read on. If not, you can use these pages to paste over your windows or to seal jars and bowls.’

No one uses paper for window repairs these days or to cover containers, so readers should simply feel free to chuck all of this into the bin.

借用鄭板橋的一句話:「有些好處,大家看看;如無好處,糊窗糊壁、覆瓿覆益而已。」如今不會用廢紙糊窗糊壁封壇蓋碗了,就請讀者將其往字紙桶里一丟吧。

— Zhong Shuhe, 20 August 1991

from Preface One below

***

- 說明: An Explanatory Note on the project by Zhong Shuhe;

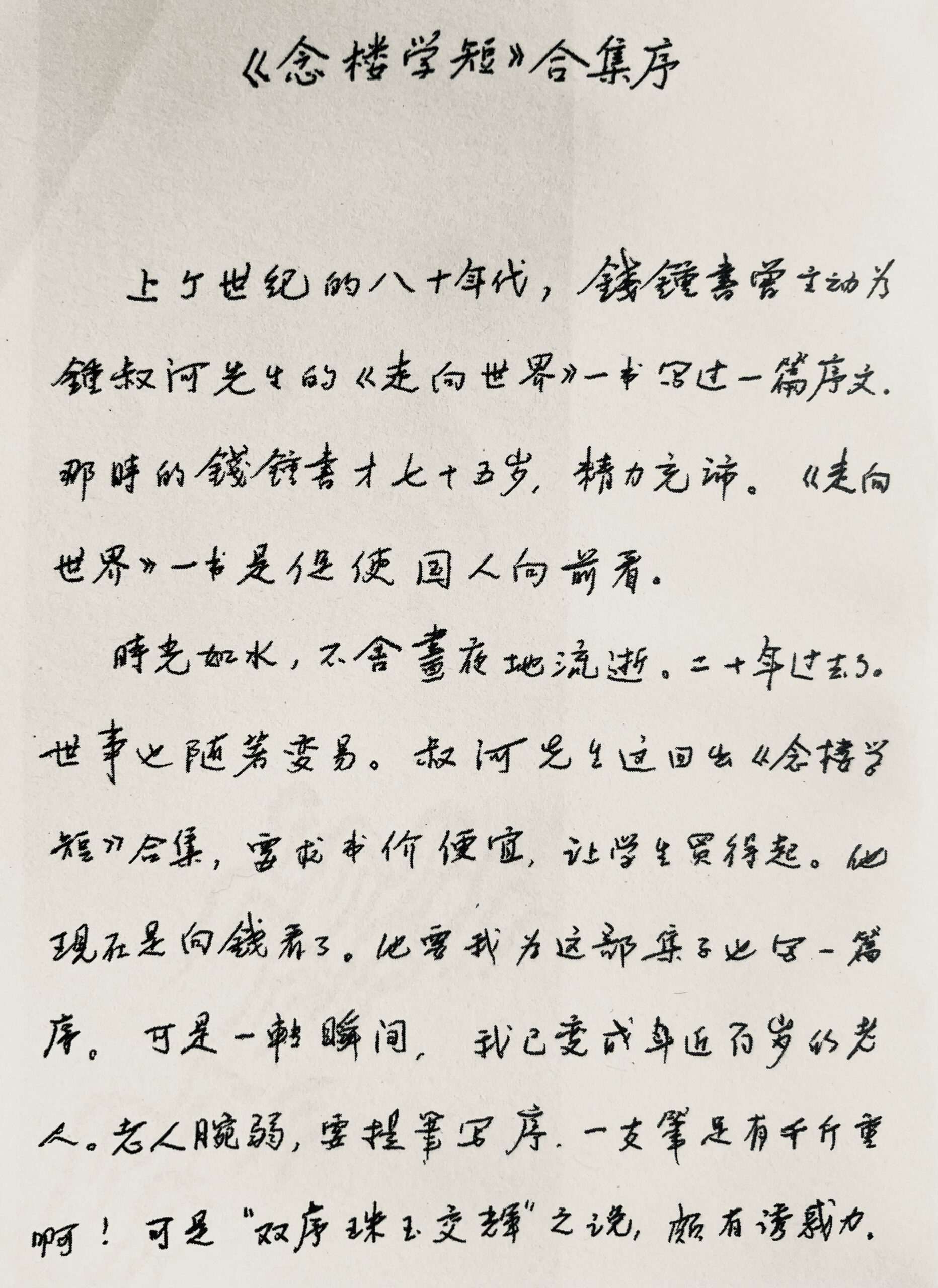

- Yang Jiang’s 2009 introduction to the complete edition of Studying Short Classical Chinese Texts with The Master of The Tower of Reading 《念樓學短》;

- Seven prefaces written by Zhong Shuhe for various editions of Studying Short Classical Chinese Texts; and,

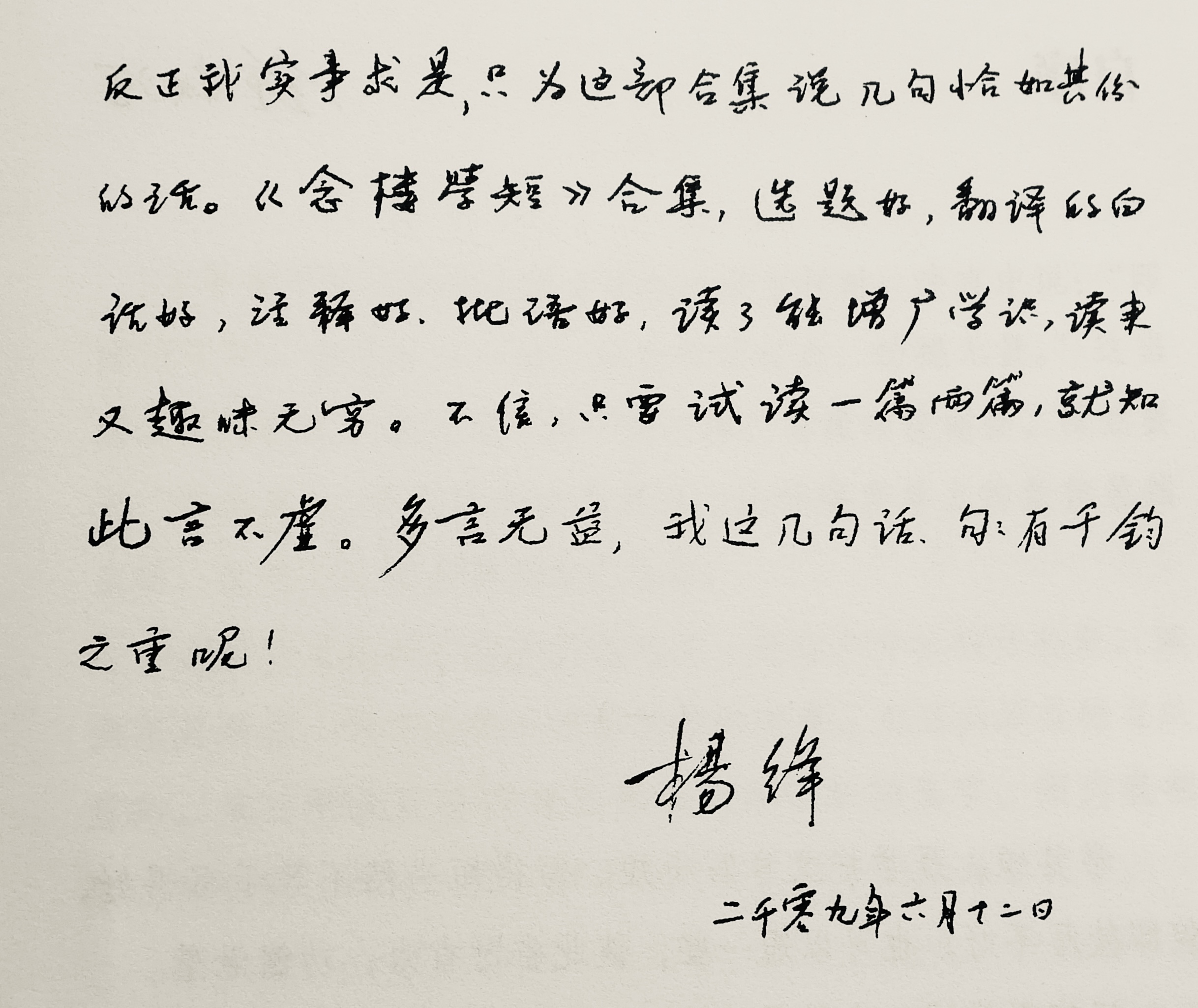

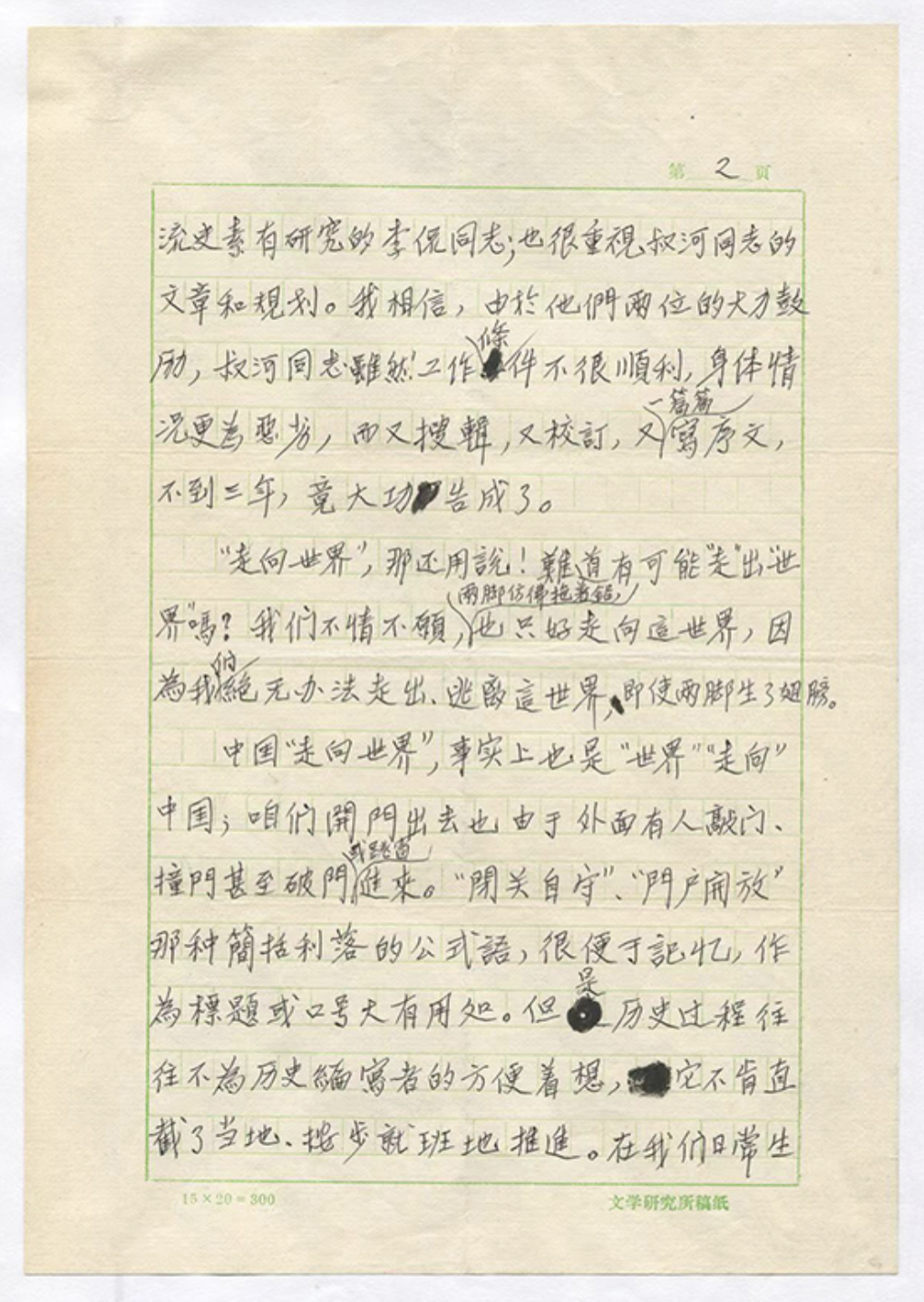

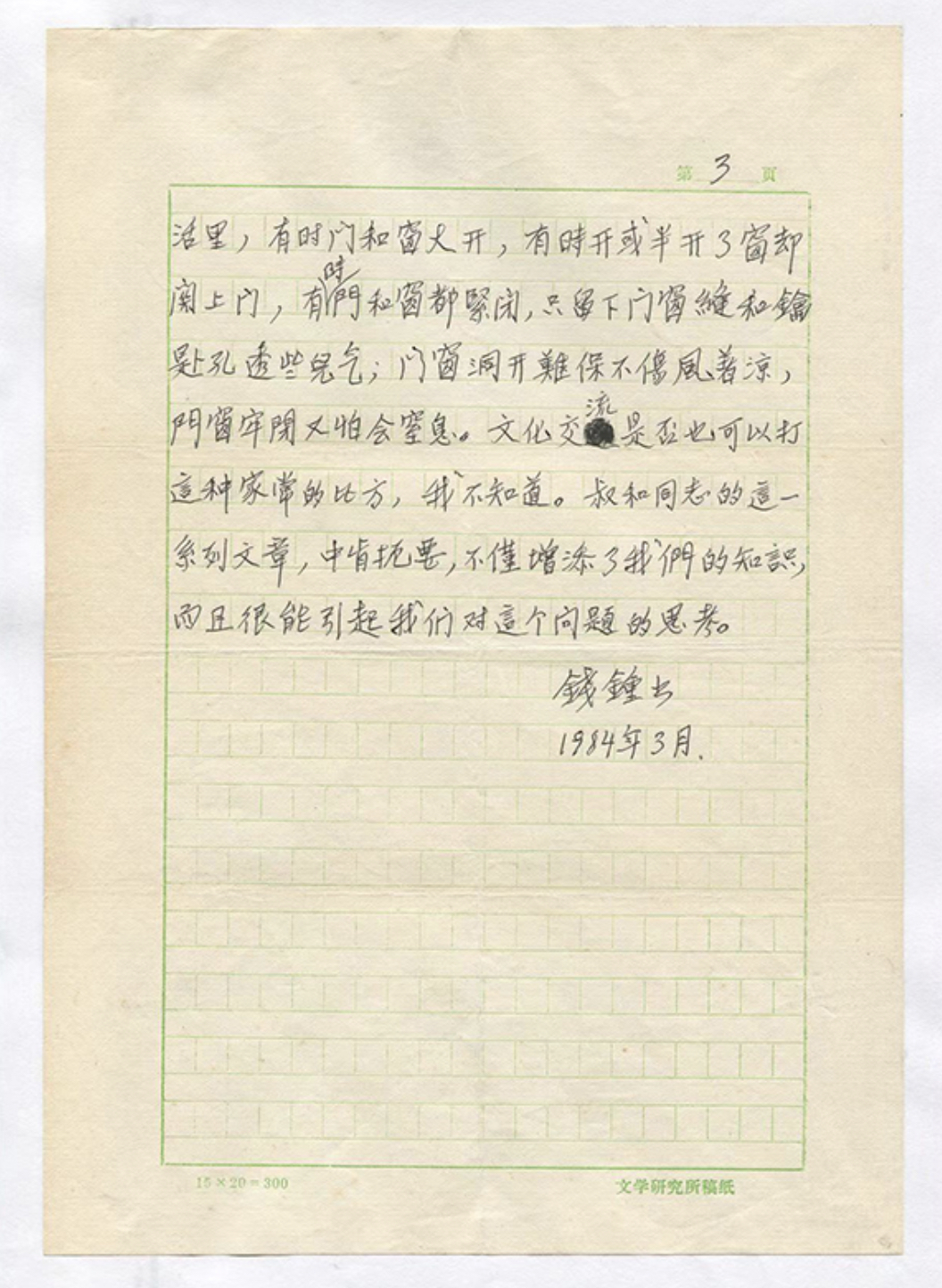

- Qian Zhongshu’s 1984 introduction to the series Going Out to the World 《走向世界叢書》,edited by Zhong Shuhe.

***

說明

《念樓學短》的文宇,從一九九一年九月開始,以專欄形式發表於各地報刊,專欄名多稱「學其短」。十年後開始出書,安徽出的便叫《學其短》(安徽教育出版社二00四年五月初版),湖南出的為了避免重名,便另取名《念樓學短》。

《念樓學短》(湖南美術出版社二00二年八月初版)和《學其短》都是一卷本,出版後都重印過。到二0一0年,《學其短》合同期滿,湖南美術出版社合二為一,將兩卷內容匯編為五卷(《逝者如斯》《桃李不言》《月下》《之乎者也》《毋相忘》),統稱《念樓學短合集》多次印行後,於二0一八年交由後浪出版公司發行,始改版為如今的上下兩冊。

今上冊收文二百六十一篇,從《論語十篇》至《春在堂隨筆八篇》,分為二十五組;下冊收文二百六十九篇,從《議論文十三篇》至《臨終的短信八篇》,分為二十八組:全書共計收文五百三十篇,分為五十三組。

自序七篇按發表時間先後刊出,而以楊絳先生作《念樓學短合集序》手跡冠於卷首。

***

《念樓學短》合集序

楊絳

***

***

自序七篇

钟叔河

壹

學其短,是學把文章寫得短。寫得短當然不等手寫得好,但即使寫不好,也可以短一些,彼此省時省力,功德無量。

漢字很難寫,尤其是刀刻甲骨,漆我竹簡,不可能像今天用電腦,幾分鐘就是一大版。故古文最簡約,少廢話,這是老祖宗的一項特長,不應該輕易丟掉。

我積年抄得短文若干篇,短的標準,是不超過一百個漢字,而且必須是獨立成篇的。現從中選出一些,略加疏解,交《新聞出版報》陸續發表。借用鄭板橋的一句話:「有些好處,大家看看;如無好處,糊窗糊壁、覆瓿覆益而已。」如今不會用廢紙糊窗糊壁封壇蓋碗了,就請讀者將其往字紙桶里一

丟吧。

一九九一年八月二十日於長沙。

(首刊一九九一年九月一日《新聞出版報》)

***

貳

《學其短》幾年前在北京報紙上開專欄時,序言中說:「即使寫不好,也可以短一些,彼此省時省力,功德無量。」這當然是有感而發。因為自己寫不好文章,總嫌囉唆拖沓,既然要來「學其短」,便不能不力求其短,這樣稿費單上的數位雖然也短,庶可免王婆婆裹腳布之譏焉。

此次應《出版廣角》月刊之請,把這個專欄續開起來,體例還是照舊,即只介紹一百字以內的文章,而且必須是獨立成篇的。也還想趁此多介紹幾篇純文學以外的文字,因為我相信,有很多人和我一樣,常親近文章,卻未必敢高攀文學。

學其短,當然是學古人的文章。但古人遠矣,代溝隔了十幾代,幾十代,年輕人可能不易接近。所以便把我自己是如何讀,如何理解的,用自己的話寫下來。這些只是我自「學」的結果,頂多可供參考,萬不敢叫別個也來「學」世。

一九九八年十二月十日於長沙。

(首刊一九九九年《出版廣角》第一期)

***

叁

《學其短》從文體著眼,這是文人不屑為,學人不肯為的,我卻好像很樂於為之。自己沒本事寫得長,也怕看「講大道理不怕長」的文章,這當然是最初的原因;但過眼稍多,便覺得看文亦猶看人,身材長相畢竟不最重要,吸引力還在思想、氣質和趣味上。

《學其短》所選的古文,本是預備給自己的外孫女兒們讀的。如今課孫的對象早都進了大學,而且沒有一個學文的,服務已經失去了對象。我自己對於古文今譯這類事情其實並無多大興趣,於是便決定在舊瓶中裝一點新酒。——不,酒還應該說是古人的酒,仍然一滴不漏地裝在這裡;不過寫明「念樓」的瓶子里,卻由我摻進去了不少的水,用來澆自己胸中的壘塊了,即標識為「念樓讀」尤其是「念樓曰」的文字是也。

這正像陶弘黑所說的,「只可自怡悅,不堪持贈君」。借題發揮雖然不大敢,但箭在弦上不得不發時,或者也會來那麼兩下吧。

二千零一年六月十一日於長沙城北之念樓。

(首刊二千零一年六月十九日《文匯報・筆會》)

***

肆

《學其短》十年中先後發表於北京、南寧和上海三地報刊時,都寫有小序,此次略加修改,仍依原有次序錄入,作為本書序言。要說的話,歷經三次都已說完,自己認為也說得十分清楚了。

三次在報刊上發表時,專欄的名稱都是《學其短》,這次卻將書名叫做 《念樓學短》。因為「學其短」 學的是古人的文章,不過幾十百把個字一篇,而「念樓讀」和「念樓曰」卻是我自己的文宇,是我對古人文章的「讀」法,然後再借題「曰」 上幾句,只能給想看的人看看,文責自負,不能讓古人替我負責。

關於念樓,我曾經寫過一篇文章,最後一向是這樣說的:

「樓名也別無深意,因為——念樓者,即廿樓,亦即二十樓也。」

二千零二年六月四日。

(首刊二千零二年湖南美術出版社《念樓學短》一卷本)

***

伍

《學其短》標出一個「短」 字,好像只從文章的長短著眼,原來在報刊上發表時,許多人便把它看成古文短篇的今譯了。

這當然不算錯,因為我拿來「讀」 和「曰」的,都是每篇不超過一百字的古文,又是我所喜歡,願意和別人共欣賞的。誰若是想讀點古文,拿了這幾百篇去讀,相信不會太失望。

可是我的主要興趣卻不在於「今譯」,而是讀之有感,想做點自己的文章。這幾百篇,與其說是我譯述的古文,不如說是我作文的由頭;雖說太平盛世無須「借題發揮」,但借古人的酒杯,流關中的金塊,大概也還屬於「夫人情所不能止者,聖人弗禁」的範圍吧!

當然,既名「學其短」,對「學」 的對象自然也要尊重,力求不讀錯或少讀錯。在這方面,自問也是盡了力的,不過將「貶謫」釋讀成「下放」的情況恐仍難免。雖然有人提醒,貶謫是專制朝延打擊人才的措施,下放是黨和人民政府培養幹部的德政,不宜相提並論。但在我看來,二者都是人從「上頭」往「下頭」走,從「中心」往「邊緣」挪。不同者只是從前聖命難違,不能不「欽此欽遵」克期上路;後來則有鑼鼓相送,還給戴上了大紅花,僅此而已。於是興之所至,筆亦隨之,也就顧不得大多了。

公元二千零四年元旦。

(首刊二千零四年安徽教育出版社《學其短》一卷本)

***

陸

二千零二年由湖南美術出版社初版的《念樓學短》一卷本,只收文一百九十篇。此次將在別處出版和以後發表於各地報刊上的同類短文加入,均按《念樓學短》一卷本的體例和版式作了修訂,以類相從編為五十三組,分為五卷,合集共計五百三十篇。

抄錄短文加以介紹的工作,事實上是從一九八九年夏天開始的,說是為了課孫,其實也有一點學周樹人躲進紹興縣館抄古碑的意思。一眨眼二十年過去,我已從「望六」進而「望八」,俟河之清,人壽兒何,真不禁感慨系之。

《念樓學短》的本意,當然是為了向古人學短,但寫的時候,就題發揮或借題發揮的成分越來越多,很大一部分都成了自己的文章。我的文章頂多能打六十分,但意思總是誠實的。此五卷合集,也妄想能和八五年初版的拙著 《走向世果》一樣,至今已四次重印,得以保持稍微長點的生命。《走向世界》書前有錢鍾書先生一序,這次便向楊絳先生求序,希望雙序珠玉交輝,作為永久的紀念。九十九歲高齡的楊絳先生身筆兩健,肯作,這實在是使我高興和受到鼓舞的。

二千零九年六月十日。

(首刊二千一十年湖南美術出版社《念樓學短合集》)

***

柒

《學其短》 和《念樓學短》每回面世,都有一篇自序,這回已是第七篇;好在七篇加起來不過三千五百字,平均五百字一篇,還不太長。

《念樓學短》和《學其短》,開頭都是一卷本,後來合二為,一卷容納不了五百三十篇文章,於是成了五卷本。至今五卷本已經印行三次,銷路越來越廣,印數越來越多;應讀者要求,還會出簡要版,出數字版,五卷本便覺得累贅了。

從本版起,《念樓學短》將分上下卷印行,五卷本成了兩巷本,但內容五十三組五百三十篇仍然依舊,只將各組編排次序略予調整。比如將「蘇軾文十 篇」「陸游文十篇」調整到「張岱文十篇」「鄭變文十篇」一起,以類相從,也許會更妥貼些。

八十年前見過一本清末外國傳教士編印的書,將《聖經》中同一段話,用各種文宇翻譯出來,各佔一頁,只有中國文言文的譯文最短。我說過,我們的古文「最簡約,少廢話,這是老祖宗的一項特長,不應該輕易丟掉」。但老祖宗的時代畢竟是過去了,社會和文化畢竟是在進步。我們要珍重前人的特長,更要珍重現代化對我們的要求和期待,這二者是可以很好地結合起來的,我以力。

二千零一十七年於長沙,時年八十六歲。

***

《走向世界叢書》序

錢鐘書

***

***

***