Intersecting with Eternity

形影神

The recluse-poet Tao Yuanming (陶淵明 or 陶潛, 365-427 CE) is famed for having given up service to the state for a life of leisure, writing, drinking, and occasional agricultural pursuits. He is the archetype of a man who has rejected the onerous demands of the day to pursue instead the cultivation of the self. This quest for quietude, one also tinged with worldly concerns and fears, is recorded in poems that, for over 1600 years, have inspired artists and writers alike.

***

Tao Yuanming’s poem ‘Substance, Shadow, and Spirit’ addresses ancient and abiding tensions between lived reality, aspiration and transcendence. Referred to and quoted by writers over the ages, Tao’s message also featured in Confessions 懺悔錄, an agonised reflection on the dilemmas of life, work and politics in modern China published by the journalist Huang Yuansheng 黃遠生 in 1915, shortly before he was assassinated in San Francisco by associates of Yuan Shikai, republican China’s president-cum-emperor.

In Confessions, Huang wrote that living under Yuan Shikai he had become ‘schizophrenic‘ and, referring to Tao Yuanming, he mourns the fact that although his soul is dead his body lives on, like an automaton, in service to pettifogging existence. For China to reform and grow, he declares ‘I must first question myself, for if I am incapable of being a man what right do I have to criticize others, let alone the society and the state?’ What matters, above all, he declares is a spirit of ‘independence and self-respect’ 獨立自尊. Decades later, Liu Xiaobo would echo these sentiments in his appeal in June 1989 for people to confront their own failings, to confess their limitations and to seek redemption through action. (For more on Huang and Liu, see Confession, Redemption, Death: Liu Xiaobo and the Protest Movement of 1989, 1990; and also Liu Xiaobo on the Inspiration of New York, 31 December 2021.)

The quest to reconcile ‘substance’ and ‘shadow’ marks Chinese life into the twenty-first century. The agonies of writers like Lu Xun and Qu Qiubai would, for some, be resolved through self-renewal under the aegis of the Chinese Communist Party. Although that rebirth was agonised and short-lived, the call for confession and ‘self-revolution’ 自我革命 is once more a feature of contemporary Chinese life, advocated by none other than Xi Jinping, the party-state-army’s Chairman of Everything.

The contemporary recasting of an ancient dilemma according to Party dogma hardly appeals to everyone. In an era of ‘involution’, ‘lying flat’ and eremitism, the fatalism of the Spirit in Tao Yuanming’s poem finds a ready resonance:

甚念傷吾生,正宜委運去。

縱浪大化中,不喜亦不懼。

應盡便須盡,無復獨多慮。

Dwelling on such things wounds my very life.

The right thing to do is to leave things to Fate,

Let go and float along on the great flux of things,

Not overjoyed but also not afraid.

When it is time to go then we should simply go.

There is nothing, after all, that we can do about it.

***

Elsewhere I have noted that the lively tension between Substance, Shadow and Spirit 身、影、神, as discussed in the following poem by Tao Yuanming, best reflects my notion of what I call The Other China. Engagement, questioning, self-doubt and transcendence are recurring themes both in China Heritage and in its various precursors.

Tao Yuanming’s work is specific to one place and a particular time in dynastic history, but its appeal reaches beyond the narrow confines of religion, state ideology and heedless materialism. The words of Stefan Zweig, which are quoted in the introduction to Intersecting with Eternity, and what he calls ‘the invisible republic of the spirit’ come to mind:

Whoever makes his home within this invisible realm becomes a citizen of the world. He is the heir, not of one people but of all peoples. Henceforth he is an indweller in all tongues and in all countries, in the universal past and the universal future.

We would suggest that the ‘spirit’ that Zweig evoked over a century ago resonates today with the Spirit 神 of Tao Yuanming’s haunting poem.

***

***

This chapter in the series Intersecting with Eternity is a companion piece to three essays on Tao Yuanming in The Tower of Reading. The first focusses on Tao himself. In the other two, the celebrated poets Su Dongpo and Lu You reflect on his inspiration.

My thanks to Callum Smith for his help with the layout of William Acker’s translation of Tao Yuanming’s poem.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

12 July 2024

***

Also in Intersecting with Eternity

- A Note from The Tower of Reading on the Double Tenth 石如飛白木如籀, 10 October 2023

- A Solitary Pursuit — ‘… then begins a journey in my head’, 5 December 2023

- So Starts the Spring, 4 February 2024

- In Cloudy Mountains, an Impossible Realm, 30 April 2024

- An Ascension, 28 May 2024

- Kinship of the Soul, 30 May 2024

- Out of Range 彀外遺少, 25 May 2018

***

Substance, Shadow, and Spirit

Tao Yuanming

translated by William Acker

Whether nobly born or humble, whether wise or simple, there is none who does not diligently seek to spare his own life, but in so doing men are greatly deluded. Therefore I have done my best to set forth the reasons for this in the form of an argument between Substance and Shadow which is finally resolved by Spirit, who expounds Nature. May gentlemen of an inquiring turn of mind take it to heart.

貴賤賢愚,莫不營營以惜生,斯甚惑焉;故極陳形影之苦,言神辨自然以釋之。好事君子,共取其心焉。

Substance Speaks to Shadow

Heaven and Earthendure and do not perish;Mountains and riversdo not change with time.Grasses and trees partakein this constant principle,Although the frost and dewcause them to wilt or flourish.Of all things Man, they say,is most intelligent and wise,And yet he aloneis not like them in this.Appearing by chancehe comes into this world,And suddenly is gonenever to return.How is one to feelthe lack of such a oneWhen even friends and kinfolkscarcely think of him?Only that the thingshe used in life are left —Coming across themmay make us shed a tear.I have no artto soar and be transfigured [1]That it must be soI cannot ever question.I only beg that youwill agree with what I sayAnd when we can get winenever perversely refuse it!

Shadow Replies to Substance

I cannot tell youhow to preserve life,And have always been ineptin the art of guarding it. [2]Yet truly I desireto roam on Kun and Hua [3]But they are far awayand the road to them is lost.Ever since I met youand have been with youI have known no othersorrows and joys but yours.Though I seemed to leave youwhen you rested in the shade,I never really left youuntil the day was done. [4]But this associationcannot last forever;Mysteriously at lastwe shall vanish in the darkness.After our death —that our name should also perishAt the mere thought of thisthe Five Passions seethe within me.Should we not laborand strive with all our mightTo do good in such a waythat men will love us for it?Wine, as they say,may dissipate our grief,But how could it everbe compared to fame?

Spirit Resolves the Argument

The Great Balance [5]has no personal power,And its myriad veinsinterlace of themselves. [6]That Man has his placeamong the Three Forces, [7]This is certainlydue to my presence with you.And although I amdifferent from you both,At birth I am addedand joined together with you.Bound and committedto sharing good and evilHow can we avoidmutual exchange?The Three Emperorswere the Primal Sages.Now, after all,whither are they gone?And though Grandfather Peng [8]achieved longevityYet he too had to gowhen he still wished to stay.Old and youngall suffer the same death,The wise and the foolish —uncounted multitudes.Getting drunk dailyone may perhaps forgetBut is not wine a thingthat shortens one’s life?And in doing goodyou may always find pleasureBut no one is obligedto give you praise for it.Dwelling on such thingswounds my very life.The right thing to dois to leave things to Fate,Let go and float alongon the great flux of things,Not overjoyedbut also not afraid.When it is time to gothen we should simply go.There is nothing, after all,that we can do about it.

***

Notes

[1] According to popular taoism, which was gradually becoming institutionalized into a church in Tao’s time, the adept could achieve these things by the practice of taoist yoga (a system of breath control), an elaborate and strict sexual regimen and, above all, a strict diet with avoidance of grain and meat and reliance on vegetables, herbs, and drugs of various kinds. Tao here shows himself to be rather skeptical of such claims.

[2] This refers specifically to taoist yoga, sexual regimen, and diet, which at the very least were supposed to confer longevity.

[3] After long and successful practice of “the art of preserving life,” culminating perhaps in the discovery of some elixir of immortality, the taoist adept was supposed to become transfigured. His very body was transformed into some finer substance, and he soared away to certain realms of the Immortals, where he lived in houses of gold and subsisted on air and dew. The Kunlun mountains far in the west, Mount Hua at the great bend of the Yellow River, and Mount Penglai floating in the midst of the Eastern Ocean were believed to be such abodes.

[4] The material soul (po [魄]), which unlike the spirit (shen [神] or hun [魂]) remains with the body after death like a sort of lingering eddy of animal magnetism, was identified with the visible shadow. But it remained with the body, whether visible or not.

[5] The Tao (Way) is the sum totality of all things, spirit, matter and the laws by which they operate, conceived of as one great monad. But though ultimately all is one, this monad expresses itself, operates, and ceaselessly creates through two apparently opposing forces, yin (shade) and yang (light). These terms are applied very widely to account for all sorts of dualities such as positive and negative, male and female, active and passive, etc. Neither one of these forces ever destroys or diminishes the other; the quantity and strength of each in these in the universe as a whole remain constant. The term Da Jun [大鈞] (“great scales,” “great balance”) expresses this truth, and so may almost be taken as an equivalent to Tao itself.

[6] Within the Tao, yin and yang, spirit and matter, the passive and the active, are all inexhaustible, indestructible, and equal. All phenomena and effects, visible or invisible, are produced by their ceaseless motion and constant interplay. Although this view of the universe leaves no room for a personal God, or deus ex machina, it cannot be called atheistic or materialistic, but is closer to what we know as pantheism or monism.

[7] The Three Cosmic Forces (San Cai [三才]) are Heaven, Earth, and Man. Chinese thought is by no means so unanthropocentric as is commonly said.

[8] The Chinese Methuselah, a very shadowy figure who had no special cult, but was merely proverbial for longevity.

***

Source:

- William Acker, T’ao the Hermit: Sixty Poems by T’ao Chi’en (365-427 A.D.), London: Thames and Hudson, 1952. See also Arthur Waley, Substance, Shadow, and Spirit.

Original text:

形影神

陶淵明

貴賤賢愚,莫不營營以惜生,斯甚惑焉;故極陳形影之苦,言神辨自然以釋之。好事君子,共取其心焉。

形贈影

天地長不沒,山川無改時。

草木得常理,霜露榮悴之。

謂人最靈智,獨復不如茲。

適見在世中,奄去靡歸期。

奚覺無一人,親識豈相思。

但余平生物,舉目情淒洏。

我無騰化術,必爾不復疑。

願君取吾言,得酒莫苟辭。

影答形

存生不可言,衛生每苦拙。

誠願游昆華,邈然茲道絕。

與子相遇來,未嘗異悲悅。

憩蔭若暫乖,止日終不別。

此同既難常,黯爾俱時滅。

身沒名亦盡,念之五情熱。

立善有遺愛,胡為不自竭。

酒云能消憂,方此詎不劣。

神釋

大鈞無私力,萬理自森著。

人為三才中,豈不以我故。

與君雖異物,生而相依附。

結托既喜同,安得不相語。

三皇大聖人,今復在何處。

彭祖愛永年,欲留不得住。

老少同一死,賢愚無複數。

日醉或能忘,將非促齡具。

立善常所欣,誰當為汝譽。

甚念傷吾生,正宜委運去。

縱浪大化中,不喜亦不懼。

應盡便須盡,無復獨多慮。

***

***

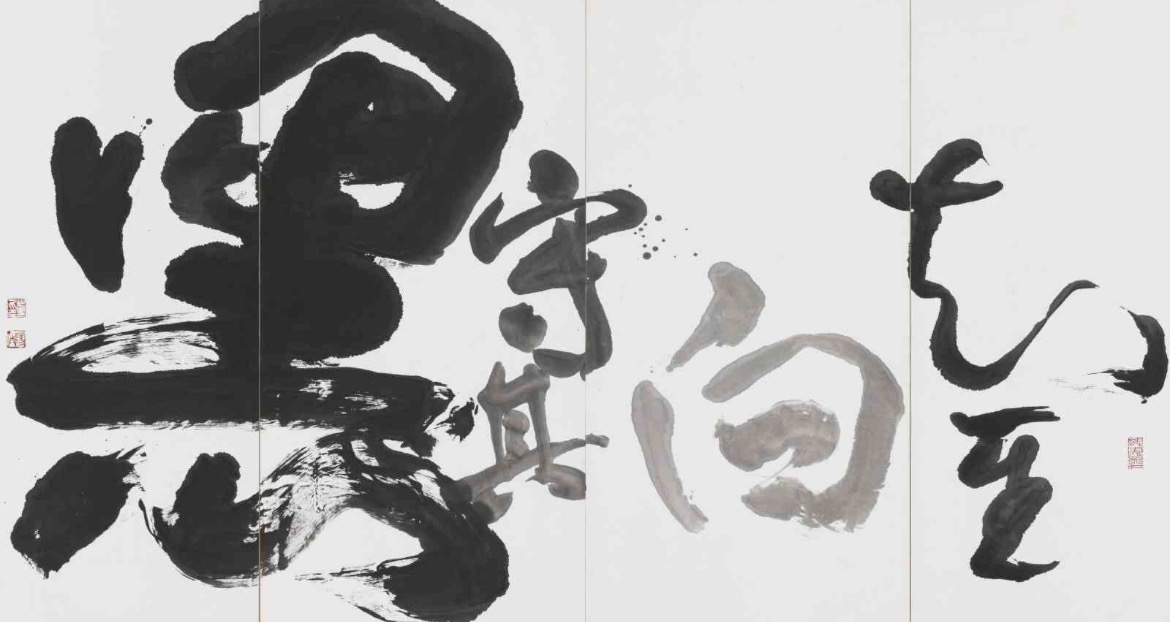

Note on two calligraphic works by Tong Yang-Tze 董陽孜:

- 大象無形,《道德經·第四十一章》

- 知其白守其黑,《道德經·第二十八章》