The Best China

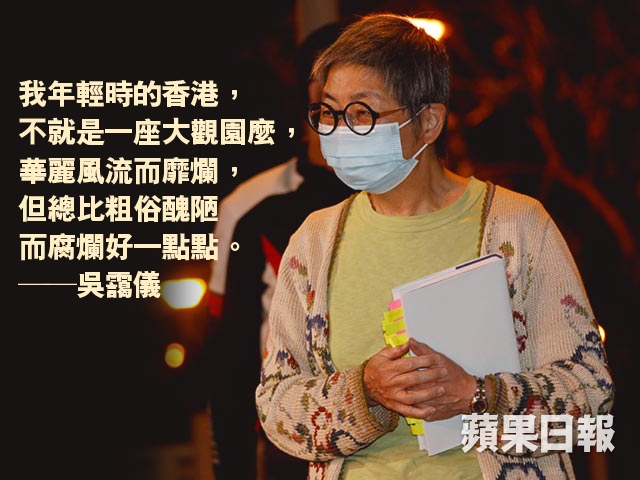

Margaret Ng (吳靄儀, Ng Ngoi-yee) is a noted politician, barrister, writer and columnist. She was a member of the Legislative Council of Hong Kong from 1995-2012. She has previously featured in two essays by Lee Yee published in our virtual pages:

- ‘The End of Hong Kong’s Third Way’, China Heritage, 22 April 2020; and,

- ‘The Road Not Taken by Margaret Ng 吳靄儀’, China Heritage, 24 April 2020

And, Ng was also one of the fifteen prominent democracy activists arrested on 18 April 2020 by the Hong Kong authorities for alleged illegal participation in the Anti-Extradition Bill protests of 2019.

In the following essay, published by Apple Daily, a leading independent newspaper in Hong Kong, on 26 April 2020, Margaret Ng discusses the fate of contemporary Hong Kong in relation to China’s most famous novel, The Dream of the Red Chamber.

For those who aspire to anything more than a glancing or transient engagement with the culture and history of China, The Dream of the Red Chamber (紅樓夢, also known as The Story of the Stone 石頭記) and Prospect Garden 大觀園 in the mansion where the action of the novel takes place remain of vital significance. The Dream as well as the Garden, the topic of Margaret Ng’s meditation on the fate of Hong Kong, have featured frequently in these virtual pages. The present essay is both a chapter in the series ‘Hong Kong Apostasy’ (for a full list of chapters scroll to the end of the following translation), part of our The Best China project, as well as being another Lesson in New Sinology.

‘Burning Down Prospect Garden’ has been translated with the kind permission of the author.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

1 May 2020

***

Related Material:

- ‘Two Letters from The Stone’ (in relation to Jia Tanchun 賈探春, who features in Margaret Ng’s essay), China Heritage, 19 March 2018

- Lee Yee 李怡, ‘The End of Hong Kong’s Third Way’, China Heritage, 22 April 2020; and,

- Lee Yee 李怡, ‘The Road Not Taken by Margaret Ng 吳靄儀’, China Heritage, 24 April 2020

- Alvin Y.H. Cheung, ‘Can We Finally Admit That “One Country, Two Systems” Is Dead in Hong Kong?’, Just Security, 30 April 2020

- John Dotson, ‘Beijing Promotes “National Security” Measures to Seek Tighter Control Over Hong Kong’, The Jamestown Foundation, 1 May 2020

A Prospect Garden

— from Yan’an to Hong Kong

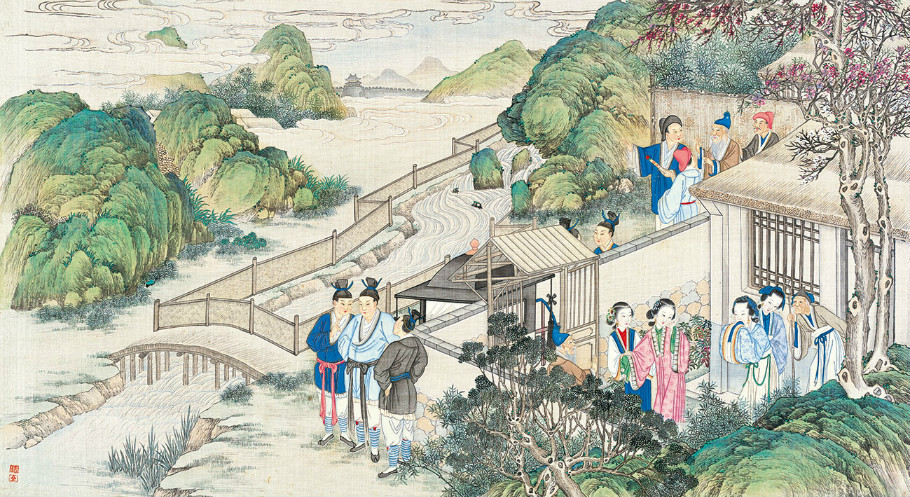

In 1938, the Communist Party leader Mao Zedong told a group of progressive writers and journalists that they should regard China as being like Prospect Garden 大觀園. That sprawling garden was part of the Jia family mansion, which is the mis-en-scène for the famous and popular late-dynastic novel, The Dream of the Red Chamber (紅樓夢, also known as The Story of the Stone 石頭記), written by Cao Xueqin in the eighteenth century. The novel is a veritable encyclopedia of late-traditional Chinese life and culture, as well as being a beguiling story of predestination, love, wealth and stately decline. For social critics and progressive historians in the twentieth century this most detailed, albeit fictional, account of Qing life was seen as a story, or parable, about social decay and an indictment of the very world that it depicts. The fact that studies of the novel came to be known as ‘Redology’ 紅學 — as a would-be textual genre in its own right — reflects something of the importance it is accorded in Chinese scholarship.

Mao had just led the party forces to complete the Long March, yet he chose to turn to a novel and its famous fictitious garden to provide a metaphor for the writers and agit-prop journalists who were gathered at the party base in Yan’an in northwest China as they prepared a new phase in the propaganda offensive against the invading Japanese and the recalcitrant Nationalist (KMT) forces of Chiang Kai‐shek.

Fascinated by the book for many years, Mao would claim that he had read The Dream of the Red Chamber five times (and his wife, the latter‐day cultural activist Jiang Qing, would go so far as to declare herself to be ‘half a Redologist’ 半個紅學家). Mao would suggest that the story of family intrigue and personal rivalries depicted in the book and its vast Prospect Garden should be seen as a decoction and artistic refraction of the decadence of late-imperial Chinese society and its class conflicts. He frequently commented on the book and, after coming to power, he would use the novel and conflicting interpretations of its meaning to orchestrate the first nationwide cultural purge that would develop into an attack on liberal democracy and its Chinese champions. The purge of that particular garden was part of the first major ‘weeding out’ of opinion, both popular and scholastic, that would no longer be tolerated under party rule.

However, on that late April day in 1938, when he was addressing the future writers and propagandists of the party who were studying at the Lu Xun Arts Academy in Yan’an, Mao had the following to say, ‘You are young artists and the world in all of its complex variety belongs to you. This is the garden in which you work… .’ He continued,

For you the whole of China is like the Prospect Garden. You must live in it and be as familiar with it as [the novel’s characters] Jia Baoyu and Lin Daiyu. You can’t just be journalists. That’s because such work is done by ‘passers-by’ [that is, superficially]. There’s a saying that goes: ‘Looking at the flowers from horseback is not as good as looking at the flowers while the horse is standing still. But it is even better to get off the horse and look at the flowers [up close]’. I hope you’ll get off your horses.

現在你們的大觀園是全中國,你們這些青年藝術工作者個個都是大觀園中的賈寶玉或林黛玉,要切實地在這個大觀園中生活一番,考察一番。… 俗話說: “走馬看花不如駐馬看花,駐馬看花不如下馬看花。” 我希望你們都要下馬看花。

Mao admonished his audience to observe closely the flowers in the garden that was China. Only then, he told them, could they understand the complex socio-political topography of the Prospect Garden, and gain thereby a true appreciation of the tortuous relationships among the inhabitants of that garden. They would then be equipped to delve into the restive, unsettled and iniquitous garden that was China itself.

For Mao, the garden of China, however, was not merely a place to visit, study or report on. More critically, it was a realm in which productive struggle and titanic transformation must take place.

— from GR Barmé, ‘Beijing, a garden of violence’

Inter-Asia Cultural Studies, 9:4 (2008): 613-615

***

The Beijing authorities and their agents in Hong Kong, be they official surrogates or the vast network of public and private informants, have had countless opportunities to study Hong Kong up close and in detail for over seventy years. For more than two decades since July 1997, they have been in possession of the Prospect Garden of the former British colony. However, time and again, their decisions and their actions have betrayed both a willful ignorance and an ideological obduracy. Rather than following Mao’s injunction to get off their horses and really study the blooms in the garden they inherited from the British colonists, the party authorities in Hong Kong and Beijing have chosen to restrict themselves mentally to the confines of Zhongnanhai, the Lake Palaces compound in the heart of Beijing. Those palaces are themselves the remains of a defunct pleasure garden inside the Qing-dyansty Imperial City; they have been the seat of party-state rule since the founding of the People’s Republic in October 1949. In many crucial ways, even now Hong Kong’s Prospect Garden remains as alien to Beijing as it was before 1997. Over long years, the wreckers-in-charge have white-anted and discarded previous agreements regarding Hong Kong’s governance. Their haplessly implemented strategy is little better than another kind of 攬炒 laam5 caau2, mutually assured devastation.

— Ed.

***

A Lexicographical Note

抄 chāo

抄家 chāo jiā

攬炒 laam5 caau2

抄 chāo:

- To make an exact or a variant copy of a text by hand 抄寫 chāoxiě; to produce a version of a manuscript, or such a manuscript itself, a 抄本 chāoběn (sometimes even a variorum, that is an editio cum notis variorum). (For an account of the knotty history of manuscript editions of The Dream of the Red Chamber, see here.) By extension it also means to copy someone else’s work and claim it as one’s own, that is to plagiarise 抄襲 chāoxí, as well as to make copies of a document or a work with the aim of either limited or wide dissemination 傳抄 chúanchāo. This is a particularly common practice during periods of repression or censorship;

- To search and confiscate 抄沒 chāomò; to search, ransack and plunder a house/ individual/ family 抄家 chāo jiā which, by extension, leads to 抄斬 chāozhǎn, that is to plunder a household and execute all of the inhabitants (family members, a whose lineage or those associated with it), as in 滿門抄斬 mǎn mén chāo zhǎn; and,

- To take a short-cut 抄近 chāo jìn, or to follow a byway 抄小道 chāo xiǎodào and, by extension, to outflank an enemy, as in 包抄 bāo chāo.

抄家 chāo jiā:

This term has dire associations, as indicated in the above. It means to ransack a home/ family/ estate/ lineage with the aim of unearthing incriminating evidence, compiling an inventory of illicit items, confiscating goods or fabricating a story of malfeasance. Such actions are usually launched as part of a local power struggle, a factional dispute, business disagreement or due to palace intrigue (what Simon Leys called ‘the lugubrious merry-go-round of Chinese politics). During the early Maoist era the practice of 抄家chāo jiā was bestowed with a quasi-legal status as part of the Communist Party’s formal policy of confiscations and divestments aimed at unseating the landlord class, the prosperous peasantry, capitalists, well-off individuals, disloyal creative figures and the bourgeoisie as a whole. The term 抄家 chāo jiā generally signifies wholesale plunder and destruction. Such actions, also known as 查抄 cháchāo, ‘to investigate and turn upside down’, frequently led to the authorities imposing judicial sanctions, various forms of ongoing prosecution/ persecution, ordering summary executions or just outright extrajudicial murder. In the periods of ‘High Maoism’ — c. 1956-1959 and 1964-1978 — 抄家 chāo jiā had an even more chilling significance that was related to targeted attacks on individuals and their families, often undertaken under the guise of self-righteous ‘revolutionary actions’ authored, for example, by Red Guards in search of incriminating evidence related to supposedly covert anti-Party activities or intentions. These mini-putsches frequently served to cover up confiscations and attacks orchestrated by radical members of the Maoist gentry (Kang Sheng 康生, the head of Mao’s secret police, and Chen Boda 陳伯達, one of his political secretaries, had a notorious talent in this regard). With a post-Mao change of policy, from the late 1970s and well into the 1980s, various gestures of restitution were made by the authorities as part of a half-hearted attempt to mollify individuals and families who had suffered these indignities, as well as inestimable material losses. Lives lost, heirlooms destroyed, properties devastated and treasuries long-since confiscated or pulverised might have been recognised even if compensation was denied or simply impossible.

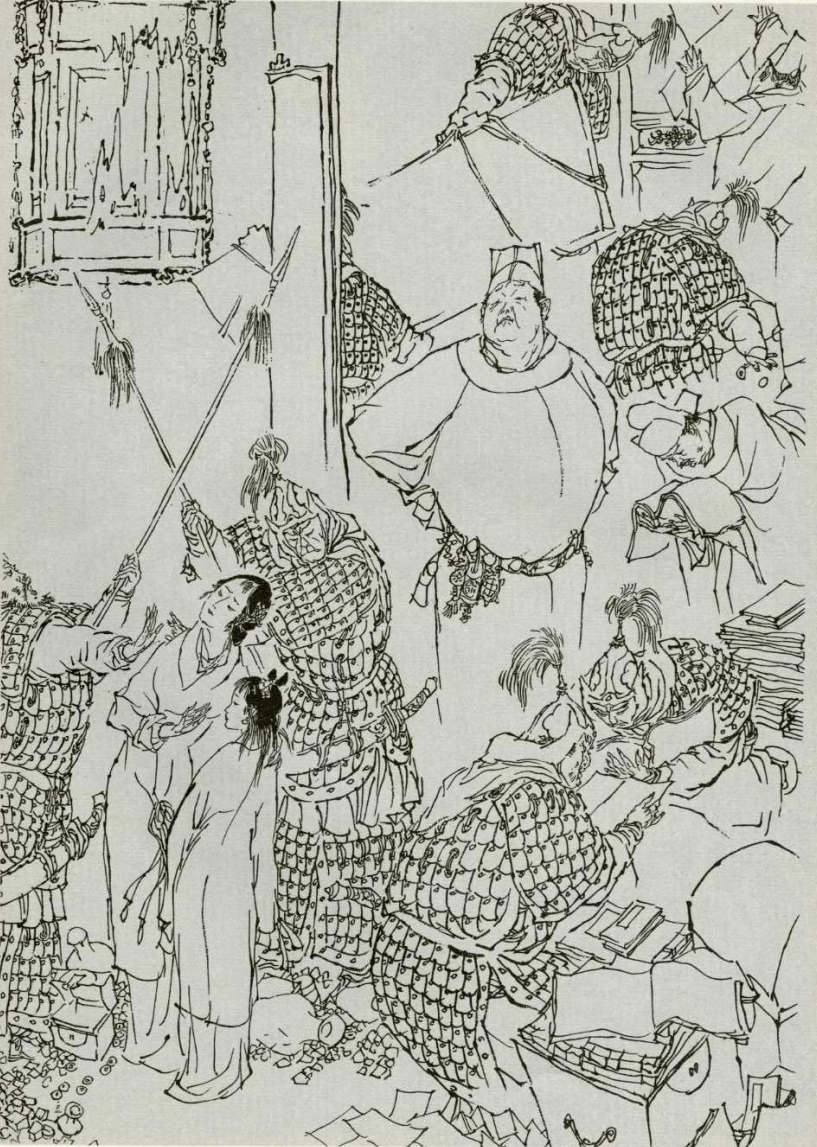

In Chapter 74 of The Dream of the Red Chamber, discussed by Margaret Ng below, the raid on Prospect Garden which is aimed at uncovering nefarious behaviour and guilty secrets is called 抄揀 chāo jiǎn, literally an act of ‘searching and sifting through’. Chapter 105 of the novel — ‘The Embroidered Jackets invade Ningguo House’ 錦衣軍查抄寧國府 — famously describes a ‘search and itemised confiscation’ 查抄 chá chāo assault on the Jia Family Mansion and its inhabitants ordered by none other than the emperor himself.

During these invasive searches, doors of the rooms to be examined, as well as the lids of boxes, chests and any vessels that may contain contraband, are sealed with paper strips known as 封條 fēngtiáo. This practice continues to the present day. The language and images featured in Chapter 105 of The Dream of the Red Chamber continue to feature in works of the imagination as well as in modern-day news stories involving state-condoned invasions of property, the compiling of inventories and confiscations.

攬炒 laam5 caau2:

This Cantonese term, which originated in online gaming, enjoyed great currency during the 2019-2020 Anti-Extradition Law Protests in Hong Kong. It means, to take someone down with you when you are facing defeat/ death/ destruction yourself. In the commercial world the expression is described as a ‘scorched-earth defence’, that is ‘a form of risk arbitrage and anti-takeover strategy’:

‘When a target firm implements this provision, it will make an effort to make itself unattractive to the hostile bidder. For example, a company may agree to liquidate or destroy all valuable assets, also called “crown jewels”, or schedule debt repayment to be due immediately following a hostile takeover. In some cases, a scorched-earth defense may develop into an extreme anti-takeover defense called a “poison pill”.’

A Cantonese-language definition offers the following:

‘If you are going to go down, then “jade and stone will both be destroyed” and the person who is trying to hurt you will end up being hurt just as bad. If you get into a trouble then your persecutor is going to be “broiled in the same wok”.’

攬炒就係同人哋玉石俱焚、兩敗俱傷嘅意思,即係若果自己出事,都要攬住加害者一鑊熟。

In Standard Chinese, the set-expression 同歸於盡 tóng guī yú jìn, ‘to travel the path to obliteration with each other’, expresses a similar sentiment. So too does a line in the 2014 film ‘The Hunger Games: Mockingjay’: ‘If we burn, you burn with us’, which enjoyed a new lease during the protests.

In the following essay, however, Margaret Ng suggests that the real desperadoes and wreckers are the Hong Kong authorities, the ‘willing executioners’ of Beijing’s will.

— Ed.

Burning Down the House

Hold tight, wait ’til the party’s over

Hold tight, we’re in for nasty weather

There has got to be a way

Burning down the house

— lyrics by Talking Heads, from the album

‘Speaking in Tongues’ (1983)

***

Burning Down Prospect Garden

紅樓夢之「攬炒」

Margaret Ng

吳靄儀

Translated by Geremie R. Barmé

As my readers may well be aware, I have been rather preoccupied of late and, although I readily concede that I have no particular insight into the meaning of the popular expression 攬炒 laam5 caau2, I must say that it brings to mind an incident in the novel The Dream of the Red Chamber. In Chapter 74 — ‘Lady Wang authorises a raid on Prospect Garden’ 惑奸讒抄揀大觀園 — Jia Tanchun [the outspoken younger half-sister of the book’s protagonist, Jia Baoyu, who is outraged to have been caught up in an unseemly attempt by the main household to cast an unflattering light on residents of Prospect Garden] makes a declaration that I think is worth sharing with my readers:

‘The searching will begin soon enough in this household when the day of confiscation arrives. Didn’t you hear the news this morning about the Zhens? They tempted fate, just as we are now doing, by carrying out a quite unnecessary search of their own servants, and now there is a confiscation order against them and they are being searched themselves. No doubt our time too is coming, slowly but surely. A great household like ours is not destroyed in a day. “The beast with a thousand legs is a long time dying.” In order for the destruction to be complete, it has to begin from within.’

— trans. David Hawkes in Cao Xueqin, The Story of the Stone,

Volume III: The Warning Voice, Chapters 54-80, p.471

[Note: For a very different use of this passage by Xi Jinping, see ‘The Heart of The One Grows Ever More Arrogant and Proud’, China Heritage, 10 March 2020]

近日有點事忙,城中熱話「攬炒」,本人也沒有什麼真知灼見,只是又想起《紅樓夢》第七十四回敍述抄檢大觀園,探春的一段話,抄錄如下,以饗讀者:

「你們別忙,自然連你們抄的日子有呢。你們今日早起不曾議論甄家自己家裏好好的抄家,果然今日真抄了。咱們也漸漸的來了。可知這樣大族人家,若從外頭殺來,一時是殺不死的。這是古人曾說的『百足之蟲,死而不僵。』必須先從家裏自殺自滅起來,纔能一敗塗地呢。」

It occurs to me that I’ve quoted this passage before. It was in the lead-up to the handover of Hong Kong [to Beijing on 1 July 1997], and I thought that Tanchun’s words offered an apt metaphor to describe how I envisaged the future of our city. You see, at that time, I had absolutely no doubt that there would be those among our number, that is Hong Kong people, who, because they were so enamored of the new power-holders and cravenly pursued self-interest, would invariably prove to be our collective undoing. As Tanchun says: ‘The destruction would begin within’. And now, indeed, ‘our time has come, slowly but surely.’ Albeit, it’s the end-result of a concerted effort spanning over twenty years — but that’s only because we have shown ourselves to be particularly recalcitrant, or was it just that Hong Kong was blessed by fate? Anyway, here we are, and this ‘beast with a thousand legs has been a long time dying.’

Of course, back in the day, when all this began, the Hong Kong people who were wrecking the place from inside were nothing more than a bunch of posturing clowns who, through shameless fawning and flattery, became enablers and sell-outs. Today, these types, ‘our own people’, have got themselves into positions of substantial power and from there they have acquired the wherewithal to destroy the promised ‘high degree of autonomy’ [offered by Beijing as a key aspect of Hong Kong’s post-1997 governance system]. In the process, it is these people who are also undoing the various checks and balances integral to the system.

It is all well and good for the Hong Kong and Macao Liaison Office [that represents Beijing in the territory] to have declared unilaterally that it feels legitimately justified in exercising its ‘supervisory rights’ over Hong Kong [and therefore not be bound by Article 22 of the ‘Basic Law’ which states that ‘no department of the Central People’s Government and no province, autonomous region, or municipality directly under the Central Government may interfere in the affairs which the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region administers on its own in accordance with this Law’]. But what it will take for that kind of ‘supervision’ to have any meaningful impact is if Hong Kong’s own ‘leader’ [that is, the Chief Executive Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor] bows to the dictates of the Office in the process of everyday governance, then, and only then, will Beijing be able to ride roughshod over us with impunity.

依稀記得,九七前我也引用過這段話喻香港未來,必得有貪圖私利扳附權勢的自家香港人,自己從內頭破壞,香港才會崩潰,果然「漸漸的來了」,大概要花上二十幾年的工夫,也算是我們骨頭硬,不然就是香港命大,「死而不僵」。可是,當年那些從內頭破壞香港的人,不過是阿諛奉承,推波助瀾,賣口乖的小丑,今日的方真是手中有權,能操刀親手自內毀掉「高度自治」及作為香港保護罩的種種制度的「自家人」。單憑兩辦聲稱可對特區行使「監督權」是不夠的,必然要有特區自己的「首長」俯從兩辦指點特區日常工作,才可以橫行無忌,通行無阻。

[When the raiding party approaches they find] an infuriated Tanchun ‘standing in the open doorway, surrounded by maids with lighted candles’. Thereupon [as doubt has been cast on her], ‘she ordered the maids to open all her boxes. She also made them bring in her dressing-cases, jewel-boxes, bedding-rolls and miscellaneous wrapped-up bundles of clothing and open them all up for Xifeng to inspect.’ [Hawkes, Stone III, p.470] — she was afforded a measure of dignity and at least the odious underlings involved in the ugly scene were held back from taking advantage of things for their own nefarious ends, despite the fact that their vile demeanor was on full display. At this stage in the action of the novel, the grand Jia Family Mansion has yet to be utterly undone, even though its ultimate decline is not far off.

因此怒探春的抗議,就是「命眾丫鬟秉燭開門而待」、「把箱一齊打開,將鏡奩、妝盒、衾袱、衣包,若大若小之物,一齊打開,請鳳姐去抄閱」──保留一點體統尊嚴,還不致爪牙惡僕恣意胡為,惡形惡相。那個階段,賈府還未「一敗塗地」,只是也不遠了。

Tanchun warns the uninvited ‘guests’ not to be in such a rush: it’ll be your turn soon enough. Isn’t that what the expression 攬炒 laam5 caau2 really means? It is others — those at the head of the household, or the forces outside it — who are really behind the actions of Wang Xifeng [who leads the raiding party on the Prospect Garden in the hope of uncovering untoward behaviour among its inhabitants]. The people who do the actual dirty work are the underlings of Wang Shanbao’s wife. Having served their purpose, it’s not long before they too are set upon and everything that they have so painstakingly and illicitly accumulated — be it power, wealth or baubles — is whisked away. Indeed, Wang Shanbao’s wife [who constantly schemes against others] gets her comeuppance later in the chapter when the raid reveals the guilt of members of her own family [as the narrator of The Dream of the Red Chamber records: she ‘who had sought out the wrongdoing of others with such single-minded persistency, was now mortified to discover that the only wrongdoer she had succeeded in unmasking was her own granddaughter.’ (Hawkes, Stone III, p.478)]

探春直斥,你們別忙,連你們也抄的日子會來──「攬炒」不就是這個意思麼?外頭、上頭,不外是要王熙鳳之流帶頭,讓王善保家的之流的惡僕去下手,開了門,這些人就沒有利用價值了,輪到她們被抄了,積聚了什麼財富權勢都一鋪清袋。那王善保家的馬上就有報應:抄家抄出自己的親戚來。

As long as Hong Kong was assured of a high degree of autonomy it enjoyed a formidable international status. From that flowed the auctoritas and dignitas — authority and accrued worth — that could justifiably be claimed by the Chief Executive and senior government officials. However, as soon as they collectively went down on bended knee in the august presence of ‘The Emperor Supremo’, as Martin Lee has dubbed Xi Jinping, what dignitas could they still claim? Do any of them really believe that family bondservants can ever be elevated to become masters or mistresses of the household?

特區一日有高度自治,香港一日有國際地位,特首高官一日才有多少尊嚴地位、值一些錢,一時「太上皇駕到」(李柱銘語)全部下跪,還有什麼地位可言?難道真的會升級做主子麼?

In this essay I’ve quoted from Chapter 74 of Yu Pingbo’s Critical Edition of the Dream of the Red Chamber in Eighty Chapters published in four volumes by Chunghwa Shuchü in January 1971 and reprinted in March 1981. (I’m not interested in all that obsessive discussion about the various manuscripts and editions of the novel.) When I set off to pursue my studies at Cambridge I only took a few books with me. The Dream of the Red Chamber was one of them. The binding and paper of my edition of the novel made it particularly easy to read no matter whether I was sitting or lying down. It’s been a faithful companion for nigh on four decades now, and every few years I leaf through it again.

Wasn’t the Hong Kong of my youth a kind of Prospect Garden? Luxurious, fashionable yet also decadent? Be that as it may, surely it was marginally better than the degraded, unprepossessing and rotten place that it has become.

我抄錄的是《紅樓夢八十四回校本》第七十四回「惑奸讒抄檢大觀園 矢孤介杜絕寧國府」,俞平伯校訂,中華書局1971年1月版,1981年3月重印,平裝一套四冊,我沒有講究版本,只是當年孑身赴劍橋,書只攜三四本,這八十回校本排版紙張釘裝都方便坐卧閱讀,就伴我伴了近四十年。每隔一段時間就會想起翻看。我年輕時的香港,不就是一座大觀園麼,華麗風流而靡爛,但總比粗俗醜陋而腐爛好一點點。

***

Source:

- 吳靄儀, ‘紅樓夢之「攬炒」’, 《蘋果日報》, 2020年4月26日

***

Hong Kong Apostasy

Proem

- Leung Ping-kwan (P.K.) 梁秉鈞, et al, Cauldron 鼎, China Heritage, 1 July 2017

- P.K. Leung 梁秉鈞, Terracotta Warriors on the Rhine 萊茵河旁的兵馬俑, trans. John Minford, China Heritage, 18 April 2019

- Chan Kin-man 陳健民, ‘A Hong Kong Farewell’, China Heritage, 24 April 2019

- Wang Ke’er 王珂兒, ‘Mother China, a Fatherland for Two Millennia’, China Heritage, 14 June 2019

Contents

- Lee Yee 李怡, ‘Endgame Hong Kong’, China Heritage, 5 July 2019

- Tsang Chi-ho 曾志豪 and Ng Chi Sam 吳志森 (RTHK), ‘Hong Kong Headliner — Kill Bill’, China Heritage, 14 July 2019

- Lee Yee 李怡, ‘Young Hong Kong’, China Heritage, 16 July 2019

- Lee Yee 李怡, ‘Hong Kong Goes Grey for a Day’, China Heritage, 20 July 2019

- Lee Yee 李怡, ‘This is Who We Are — We Are Hong Kong’, China Heritage, 22 July 2019

- Wong Wing-sum 黃泳欣, ‘Hong Kong Headliner Makes Headlines’, China Heritage, 24 July 2019

- Lee Yee 李怡, ‘Living and Learning in Hong Kong 2019’, China Heritage, 29 July 2019

- Lee Yee 李怡, ‘Back in the Year — Hong Kong 1984’, China Heritage, 31 July 2019

- Lee Yee 李怡, ‘Restoring Hong Kong, Revolution of Our Times’, China Heritage, 6 August 2019

- He Weifang 賀衛方, ‘Hong Kong — 2019, 2003, 1984, 1979’, China Heritage, 12 August 2019

- Wu Ningkun 巫寧坤, Dylan Thomas, et al, ‘Rage Against the Dying of the Light — poems for tenebrous times’, China Heritage, 13 August 2019

- Ni Kuang 倪匡, ‘The Nobility of Failure’, China Heritage, 14 August 2019

- Canny Leung Chi-Shan 梁芷珊, ‘Like Water, Boiling Water’, China Heritage, 15 August 2019

- Kitty Hung Hiu Han 洪曉嫻, ‘How Dare You Hong Kong People Resist!’, China Heritage, 18 August 2019

- Brian Leung Kai Ping 劉繼平, ‘I am Brian Leung: they cannot understand; they cannot comprehend; they cannot see’, China Heritage, 20 August 2019

- Tsang Chi-ho 曾志豪, ‘Hong Kong’s Acclimation’, China Heritage, 21 August, 2019

- Lester Shum 岑敖暉, ‘Auntie Carrie, Puh-leeze!’, China Heritage, 22 August 2019

- Lee Yee 李怡 and others, ‘Holding Hands in Hong Kong’, China Heritage, 26 August 2019

- Lee Yee 李怡, ‘The Mission of Our Times in Hong Kong’, China Heritage, 28 August 2019

- The Stand News Exclusive Interview, ‘Cockroaches That Would Slay Dragons’, China Heritage, 1 September 2019

- Kitty Hung Hiu Han 洪曉嫻 and Lester Shum 岑敖暉, ‘Freedom-Hi & #ProtestToo’, China Heritage, 4 September 2019

- Concerned Hong Kong Citizens, ‘For We are Like Olives’, China Heritage, 6 September 2019

- P.K. Leung 梁秉鈞, ‘Leaf Margin — a poem by P.K. Leung’, trans. John Minford, China Heritage, 8 September 2019

- The Stand News 立場新聞 Report, ‘A Summer of Blood and Tears — according to six Hong Kong high-school students’, China Heritage, 9 September 2019

- The Stand News 立場新聞 Interview, ‘An Anthem to Restore Hong Kong’, China Heritage, 12 September 2019

- Xu Zhangrun 許章潤 & Yi-Zheng Lian 練乙錚, ‘A Protracted People’s Struggle’, China Heritage, 14 September 2019

- Cecil Clementi & P.K. Leung 梁秉鈞, ‘Hong Kong, 1925; 1997; 2019 — Splendeat Sapientiae Lumen ex Oriente‘, China Heritage, 18 September 2019

- The Extreme Minority Singers of Featherston, ‘Singing for Hong Kong’, China Heritage, 24 September 2019

- Lee Yee 李怡 & To Kit 陶傑, ‘China, The Man-Child of Asia’, China Heritage, 26 September 2019

- ‘Liberate Hong Kong — The Hundredth Day Declaration: Our Resolute Fight for Universal Suffrage and Battle against State Violence’「光復香港」百日宣言, China Heritage, 26 September 2019

- Yangyang Cheng, ‘Writing Home on China’s Seventieth Birthday’, China Heritage, 1 October 2019

- Jason Wong Yiu-pong 黃耀邦, ‘Voiceless, but Not Silent’, China Heritage, 5 October 2019

- Various Hands, ‘The Double Ninth in 2019 — Settling Scores, Fleeing The Qin and Eating Crabs’, China Heritage, 7 October 2019

- Lao Tzu 老子, ‘The Best is Like Water’, trans. John Minford, China Heritage, 16 October 2019

- Lee Yee 李怡, ‘Superfluous Words’, China Heritage, 20 November 2019

- Yangyang Cheng, ‘Talking to My Mother About Hong Kong’, China Heritage, 30 November 2019

- Lee Yee 李怡, ‘The End of Hong Kong’s Third Way’, China Heritage, 22 April 2020

- Lee Yee 李怡, ‘The Road Not Taken by Margaret Ng 吳靄儀, China Heritage, 24 April 2020

- Margaret Ng 吳靄儀, ‘Hong Kong 攬炒 — Burning Down the House’, China Heritage, 1 May 2020