Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium

Chapter XXII

官逼民反

‘Tears of sorrow are flowing from the Far West

of China to the seaboard in the East.’

熱淚從中國的最西一直流到中國的最東。

A line circulating on Chinese social media captured the mood of sorrow following a fire in a residential high-rise in Urumqi, Xinjiang, on Thursday the 24th of November 2022. As people around China mourned the dead — and realised that relentless official lockdowns in their own cities meant that they could share a similar fate — that fire in far western China ignited nationwide outrage.

Protests spread to cities and campuses in China on Saturday night [26 November] amid rising public anger at the country’s strict but faltering controls against the spread of Covid, with a crowd in Shanghai going so far as to call for the removal of the national leader, Xi Jinping.

The demonstration occurred after an outpouring of anger online and after a street protest erupted on Friday in Urumqi, the regional capital of Xinjiang in western China, where at least 10 people died and nine others were injured a day earlier in an apartment fire. Many Chinese people say they suspect that those killed were hindered from escaping their homes by Covid restrictions — despite government denials.

The tragedy has fanned broader calls for officials to ease China’s harsh regimen of Covid tests, urban lockdowns and restrictions on movement three years into the pandemic.

The biggest protest on Saturday appeared to have occurred in Shanghai, where college and university students were among hundreds of people who gathered at an intersection of Urumqi Road — named after the city in Xinjiang — to mourn the dead with candles and signs. The numbers grew, defying police efforts to hold back the throng, and chants broke out, with people calling for an easing of the Covid controls, video footage showed.

“We want freedom,” the protesters chanted.

They used obscene language to denounce the demand that residents check in with a Covid phone app in public places such as shops and parks. While lines of police officers watched, some in the crowd directed their anger at Mr. Xi, a rare act of political defiance that was likely to alarm Communist Party officials, prompting tighter censorship and policing.

“Xi Jinping!” a man in the crowd repeatedly shouted.

“Step down!” some chanted in response.

— from Chris Buckley, Protests Erupt in Shanghai and Other Chinese Cities Over Covid Controls, The New York Times, 26 November 2022

***

***

This chapter in our series Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium follows on from Awakenings — a Voice from Young China on the Duty to Rebel, published on 14 November 2022.

This latest nationwide moment of awakening 覺醒 juéxǐng actually began in 2018 when a few courageous protesters openly opposed revisions to the Chinese Constitution that would enable Xi Jinping to rule indefinitely. Outspoken individuals like Xu Zhangrun, Ren Zhiqiang and Xu Zhiyong were soon silenced. A new, and more widespread, wave of protests broke out during the early phase of the coronavirus epidemic in 2020 following the death of the whistle-blower Dr Li Wenliang. The ‘People’s War’ against the coronavirus epidemic led by Xi Jinping included the further repression of dissent, including the silencing of Zhang Zhan, Li Zehua and Chen Qiushi, among others. (For details, see Viral Alarm — China Heritage Annual 2020.)

As we noted in Awakenings, on 13 October 2022, a lone protester unfurled two long cloth banners on the Sitongqiao Overpass near the university district in Beijing. It was only days before the ruling Communist Party convened its twentieth national congress and the protester, who called himself ‘Peng Zaizhou’ 彭載舟, issued a call for rebellion which he summed up in pithy slogans:

不要核酸要吃飯,

不要文革要改革。

不要封城要自由,

不要領袖要選票。

不要謊言要尊嚴,

不做奴才做公民。

We don’t want COVID tests. We want to eat.

We don’t want Cultural Revolution. We want reforms.

We don’t want lockdowns. We want freedom.

We don’t want a Leader. We want the vote.

We don’t want lies. We want dignity.

We aren’t slaves. We are citizens.

Peng concluded his list of grievances and demands with an even more daring act of lèse-majesté:

罷課罷工罷免國賊習近平。

Refuse to go to class. Go on strike. Remove Xi Jinping, traitor to our nation.

Peng Zaizhou, whose real name is Peng Lifa (the sobriquet Zaizhou 載舟 was a pointed reference to an ancient adage: ‘the people are like water, they can either buoy or bury the power-holders’), attracted the attention of passersby to his banners with smoke billowing from a fire he lit in a garbage bin and a pre-recorded message broadcast on a loudspeaker set up on the overpass. Earlier that day, he had released an online action plan in which he called on Chinese citizens to protest against Xi Jinping en masse on Sunday 16 October 2022, the first day of the Party Congress. He accompanied the material with a long historical poem.

Peng Zaizhou’s slogans reappeared during the weekend of protests that shook dozens of Chinese cities on 26-27 November 2022, as well as on university campuses throughout the country.

Peng Zaizhou’s solitary protest had been compared to the solo rebellion of Xu Zhangrun, the Tsinghua University professor of jurisprudence who had published a lengthy critique of Xi Jinping’s rule in July 2018. Both men were hailed as 孤勇者 gū yǒng zhě, ‘lone heroes’:

章潤一文驚天下,是思想的孤勇者。

載舟點火天下驚,是行動的孤勇者。

Xu Zhangrun’s essay shocked China; he is a lone intellectual warrior;

The fire Zaizhou lit has left China shocked; he is a lone action warrior.

Here we reprint Viral Alarm: When Fury Overcomes Fear, a translation that was originally published by ChinaFile on 10 February 2020. Composed by Xu Zhangrun in January 2020 just as the Wuhan influenza was turning into an epidemic, and on the eve of it becoming a global pandemic, that essay predicted how the party-state controlled by Xi Jinping would respond to and mishandle the national public health emergency. Xu saw beyond the initial, and largely effective, authoritarian responses to the crisis and pointed out the systemic limitations of Xi’s ‘new era’ that would inevitably result in ever-greater social anomie and disaster.

Professor Xu had been commenting on the depredations of the Xi Jinping era. In January 2012, he had expressed both hopes and fears for the future as the restrictive educational policies overseen by the general-party-secretary-in-waiting Xi were transforming Chinese higher education. As we record in ‘Ecce Homo and China’s Hopium Crisis’ — the forthcoming eighteenth chapter of Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium — with each passing year Xu Zhangrun’s warnings became more stark, just as his language became more pointed. In July 2018, he published a systematic critique of the fatal flaws of the Xi Jinping system and, even as he was being persecuted for his outspokenness, he continued to dissect the historical origins and potential disasters of Xi Jinping’s rule (for details, see the Xu Zhangrun Archive).

In Tally — the Threnody of Tedium, a preface to the present series, we observed that:

The threnody of the Xi Jinping decade is tedium, something born of the ceaseless oscillations within China’s hermetically sealed system. It signals its deadening presence through reversals and the glum repetition of various tropes of the past. In this era, what was formerly limited divergence has given way to convergence, difference to singularity, diversity to homogeneity. Where in the past there was wriggle room, a straitjacket now awaits; possibility is all too frequently replaced by ordained inevitability; contingency by certainty and the unpredictable is met with inflexibility and harshness. For those who have lived with China’s party-state over the decades the déja-vu quality of the Xi era is undeniable. It is an age that sets itself against the unpredictable, the contingent, against the disheveled nature of reality itself; as a result it is implausible, brittle and in constant crisis-mode.

The crisis sparked by the apartment fire in Urumqi on 24 November 2022 is the kind of ‘black swan event’ of which Xi Jinping and his comrades have been fearful for years. They have been far less willing to consider the danger they pose to themselves, something summed in the Qing-era expression 官逼民反 guān bī mín fǎn, ‘the repressive behaviour of officials incites popular rebellion’.

On Sunday, 27 November, students at Tsinghua University protested en masse. Their calls for ‘democracy and rule of law’ and ‘freedom of expression’ echoed the lone voice of Xu Zhangrun, the Tsinghua professor who had been stripped of his job and ejected from the campus in 2019.

***

This chapter in Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium should be read in conjunction with:

- Chapter Twenty-one 醒 — Awakenings — a Voice from Young China on the Duty to Rebel, 14 November 2022

- Appendix XXIII 空白 — How to Read a Blank Sheet of Paper, 30 November 2022

- Appendix XXIV 職責— It’s My Duty, 1 December 2022

- Appendix XXV 贖 — ‘Ironic Points of Light’ — acts of redemption on the blank pages of history, 4 December 2022

- Appendix XXVI 囿 — A Ray of Light, A Glimmer of Hope — Li Yuan talks to Jeremy Goldkorn & to a Shanghai protester, 10 December 2022

- Appendix XXVII 謔— When Zig Turns Into Zag the Joke is on Everyone, 12 December 2022

— Geremie R. Barmé, Editor, China Heritage

Distinguished Fellow, Asia Society

27 November 2022

***

Related Material:

- Awakenings — a Voice from Young China on the Duty to Rebel, China Heritage, 14 November 2022

- Xi the Exterminator & the Perfection of Covid Wisdom, China Heritage, 1 September 2022

- Jeremy Goldkorn, ‘Ugh, here we are’ — Q&A with Geremie Barmé, The China Project, 8 April 2022

- A voice from old Shanghai under COVID lockdown, The China Project, 6 April 2022

- 李老師不是你的老師, Twitter

- 狗哥,「白紙革命」之夜,2022.11.27,上海/北京/成都/廣州/武漢… , 油管,2022年11月28日

- 袁莉,那些年輕的抗議者:我們為什麼要上街,《不明白》播客,2022年11月29日

- Samuel Wade, In tweets: protests break out across China after Urumqi fire, China Digital Times, 27 November 2022

- Oliver Young, Mourning for victims of Urumqi fire escalates into nationwide anti-lockdown, anti-government protests, China Digital Times, 27 November 2022

- Yan Long’s analysis, Twitter

- William Hurst’s analysis, Twitter

- Chris Buckley, Vivian Wang, Chang Che and Amy Chang Chien, After a Deadly Blaze, a Surge of Defiance Against China’s Covid Policies, The New York Times, 27 November 2022

- 方的言 第1298期, 上海烏魯木齊中路,人群高呼「習近平下台」!,油管,2022年11月26日

- Chris Buckley, Protests Erupt in Shanghai and Other Chinese Cities Over Covid Controls, The New York Times, 26 November 2022

- Chang Che and Amy Chang Chien, Protest in Xinjiang Against Lockdown After Fire Kills 10, The New York Times, 25 November 2022

- Amy Chang Chien, Chang Che, John Liu and Paul Mozur, In a Challenge to Beijing, Unrest Over Covid Lockdowns Spreads, The New York Times, 24 November 2022

- Joy Dong and Vivian Wang, 3-Year-Old in China Dies After Covid Restrictions Delayed Care, The New York Times, 4 November 2022

- Vivian Wang and Joy Dong, Bus Taking People to Quarantine Crashes in China, Killing 27, The New York Times, 19 September 2022

- Geremie R. Barmé, The Good Caucasian of Sichuan & Kumbaya China, China Heritage, 1 September 2020

- Viral Alarm — China Heritage Annual 2020

- Xu Zhangrun Archive, China Heritage (1 August 2018-)

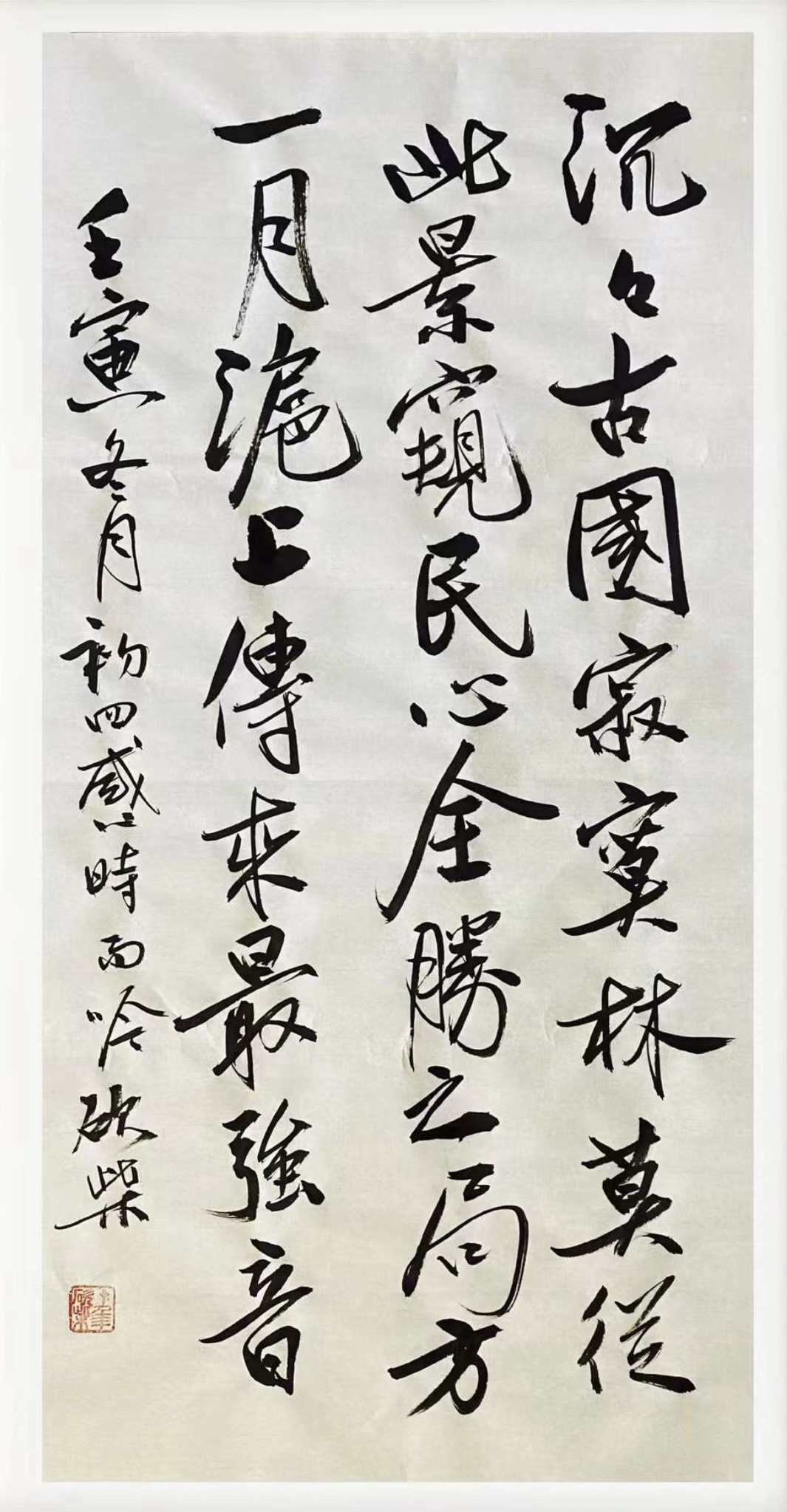

A Protest in Poetry

***

Silence may appear to reign in this ancient repressed land, but don’t be fooled into believing that this reflects the true state of people’s minds.

Thorough-going victory celebrated but a month ago [it has only been a month since Xi Jinping dominated the Twentieth Congress of the Chinese Communist Party in October 2022], yet the clamour from Shanghai proves louder still.

A poem composed by Kan Chai [aka 十年砍柴, pen name of the writer Li Yong 李勇] in response to current events

The Fourth Day of the Eleventh Month of the Renyin Year of the Tiger

[27 November 2022]

***

Contents

This chapter of Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium is divided into the following sections (click on a section title to scroll down):

- Politics in a New Era of Moral Depletion

- Tyranny in a New Era of Political License

- A New Era of Attenuated Governance

- A New Era of Revived Court Politics

- A New Era of Big Data Totalitarianism and WeChat Terror

- A New Era That Has Shut Down Reform

- A New Era of Isolation

- A New Era in Which to Seek Freedom from Fear

- A New Era in Which the Clock Is Ticking

***

Translator’s Preface

24 February 2020

In July 2018, the Tsinghua University professor Xu Zhangrun published an unsparing critique of the Chinese Communist Party and its Chairman of Everything, Xi Jinping. In it Xu warned of the dangers of one-man rule, the threats posed by an increasingly sycophantic bureaucracy and putting politics ahead of professionalism, as well as the myriad of other problems that the system would encounter if it resisted further substantive economic and political reforms and instead continued along its present path. That philippic was one of a cycle of works that Xu composed during 2018 in which he alerted readers to these and other pressing issues related to China’s momentous ongoing struggle with modernity, the state of the nation under Xi Jinping and the mixed prospects for the future. Scheduled to be published by Hong Kong City University Press, but then rejected due to ‘national security concerns’, those collected essays appeared with Boden Books in New York in May 2020 under the title China’s Ongoing Crisis: Six Chapters from the 2018 Year of the Dog 許章潤著 《戊戌六章》 .

Although he was demoted by Tsinghua University in March 2019 and banned from teaching, writing and publishing, Xu remained defiant. ‘When Fury Overcomes Fear’ — translated below, appeared online on 4 February 2020 as the coronavirus epidemic swept China and infections overseas sparked concern around the world. This translation was originally published by ChinaFile on 10 February 2020 and carried in China Heritage on 24 February 2022.

Xu’s writing style combines elements of classical Chinese in which references to or quotations from philosophy, history and literature are seamlessly interwoven in an elegant but highly personalized literary form that was commonly employed by members of China’s élite from the late-nineteenth to the mid-twentieth centuries. It is a prose free of Party jargon, although the author frequently makes mocking reference to officialese and to the kind of Europeanized Chinese popularized in the 1910s when the vernacular was promoted by political and cultural progressives. Despite that fact that the written language became more expressive of modern ideas it was soon overwhelmed by a kind of Communist Partyspeak that has for decades dominated China’s media.

In translating Xu’s work I hint at the orotund style of the original and occasionally use capital letters and or quotation marks to emphasize terms that have a particular significance for the author. Xu never refers to Xi Jinping by name, rather he employs various classical (and sometimes cheekily arcane) terms to lampoon the ‘People’s Leader’.

‘When Fury Overcomes Fear’ is translated and annotated with the author’s permission. We are grateful to Susan Jakes of ChinaFile for permission to reprint it here. In so doing we have retained the typographical style of the original, although we have added the original Chinese text.

***

Selected English-language Media Reports:

- Xu Zhangrun, ‘Viral Alarm: When Fury Overcomes Fear’, trans. Geremie R. Barmé, ChinaFile, 10 February 2020

- Jun Mai, ‘Chinese scholar blames Xi Jinping, Communist Party for not controlling coronavirus outbreak’, 6 February 2020

- ‘China said to target scholar who criticized government’s response to the crisis’, Live Updates, The New York Times, 11 February 2020

- Associated Press, ‘China’s Communist Party Faces Its Biggest Crisis Since SARS’, The New York Times, 12 February 2020

- Lily Kuo, ‘Coronavirus: outspoken academic blames Xi Jinping for “catastrophe” sweeping China’, The Guardian, 11 February 2020

- MCLC RESOURCE CENTER (Modern Chinese Literature and Culture), Ohio: Xu Zhangrun ‘Viral Alarm’, 12 February 2020

- Evan Osnos, ‘China’s “Iron House”: struggling over silence in the coronavirus epidemic’, The New Yorker, 12 February 2020

- Emma Graham-Harrison, ‘What China’s empty new coronavirus hospitals say about its secretive system’, The Guardian, 12 February 2020

- Bill Bishop, ‘Virus peak near?; Positive propaganda energy as emphasis on restarting economy increases; Xu Zhangrun’s new essay’, Sinocism, 12 February 2020

- Samuel Wade, ‘Coronavirus “Rumor” Crackdown Continues with Censorship, Detentions’, China Digital Times, 12 February 2020

- Nicholas Kristof, ‘I Cannot Remain Silent’, The New York Times, 16 February 2020

***

***

The ancients observed that “it’s easier to dam a river than it is to silence the voice of the people.” Regardless of how good they are at controlling the Internet, they can’t keep all 1.4 billion mouths in China shut. Yet again, our ancestors will be proved right. Nonetheless, since all of their calculations are solely made on the basis of maintaining control, they have convinced themselves that such crude exercises of power will suffice. They have been fooled by the self-deception of “The Leader,” but theirs is a confidence that deceives no one. Faced with this virus, the Leader has flailed about seeking answers with ever greater urgency, exhausting those who are working on the front line, spreading the threat to people throughout the land. Ever more vacuous slogans are chanted—Do this! Do that!—overweening and with prideful purpose, He garners nothing but derision and widespread mockery in the process. … The last seven decades [of the People’s Republic] have taught the people repeated lessons about the hazards of totalitarian government. This time around, the coronavirus is proving the point once more, and in a most undeniable fashion.

One can only hope that our fellow Chinese, both young and old, will finally take these lessons to heart and abandon their long-practiced slavish acquiescence. It is high time that people relied on their own rational judgment and refused to sacrifice themselves again on the altar of the power holders. Otherwise, you will all be no better than fields of garlic chives; you will give yourselves up to being harvested by the blade of power, now as in the past.

[Note: The term “garlic chives,” 韭菜 or Allium tuberosum, is used as a metaphor to describe the common people who are regarded by the power-holders as an endlessly renewable resource.]

— from Xu Zhangrun, Viral Alarm

Viral Alarm: When Fury Overcomes Fear

憤怒的人民已不再恐懼

Xu Zhangrun

許章潤

Translated and annotated by Geremie R. Barmé

February. Get out the ink and weep!

Sob in February, sob and sing

While the wet snow rumbles in the street

And burns with the black spring.

— Boris Pasternak

(Translated by Sasha Dugdale)

二月。墨水足夠用來痛哭,

大放悲聲抒寫二月,

一直到轟響的泥濘,

燃起黑色的春天。

—— 帕斯捷爾納克

Introduction

As the Year of the Pig [2019] gave way to the Year of the Rat [February 2020], a virus originating in Wuhan, capital of Hubei province—a city famed as the nation’s major transportation and communication hub—was spreading throughout China. Overnight, the country found itself in the grip of a devastating crisis and fear stalked the land. The authorities proved themselves to be at a loss as to how to respond effectively and the high cost of their impotence was soon visited upon the common people. Before long, the coronavirus was reaching around the globe and the People’s Republic found itself rapidly isolated from the rest of the world. It was as though the China famed for its Economic Reform and Open Door policies for more than three decades was being undone in front of our very eyes. In one fell swoop it seemed as though the People’s Republic, and in particular its vaunted system of governance, had been cast back to pre-modern times. As word spread about blockades being thrown up by towns and cities in an attempt to seal themselves against contagion, as doors were slammed shut everywhere, it actually felt as though we were being overwhelmed by the kind of primitive panic more readily associated with the Middle Ages.

The cause of all of this lies, ultimately, with The Axlerod [that is, Xi Jinping] and the cabal that surrounds him. It began with the imposition of stern bans on the reporting of accurate information about the virus which but served to embolden deception at every level of government, although it only struck its true stride when bureaucrats throughout the system consciously shrugged off responsibility for the unfolding crisis while continuing to seek the approbation of their superiors. They stood by blithely as the crucial window of opportunity that was available to deal with the outbreak snapped shut in their faces.

Ours is a system in which The Ultimate Arbiter [定於一尊, an imperial-era term used by state media to describe Xi Jinping] monopolizes all effective power. This led to what I would call “organizational discombobulation” that, in turn, has served to enable a dangerous “systemic impotence” at every level. Thereby, a political culture has been nurtured that, in terms of the actual public good, is ethically bankrupt, for it is one that strains to vouchsafe its privatized Party-State, or what they call their “Mountains and Rivers” while abandoning the people over which it holds sway to suffer the vicissitudes of a cruel fate. It is a system that turns every natural disaster into an even greater man-made catastrophe. The coronavirus epidemic has revealed the rotten core of Chinese governance; the fragile and vacuous heart of the jittering edifice of state is thereby on display as never before.

This viral outbreak, which has been exacerbated by the behavior of the power-holders and turned into a national calamity, is more perilous perhaps than total war itself. Everything is being caught up in the struggle—the nation’s ethical fabric, its politics, our society, as well as the economy. Let me say that again—the situation is even more perilous than total war, for it is leaving the nation open to a kind of devastation that even foreign invaders failed to visit upon us in the past. The ancients put it well, “Only thieves nurtured at home can truly despoil a homeland.” Although the Americans may well be trying to undermine our economy, The Axlerod is beating them to it here at home! Please note: just as the epidemic was reaching a critical moment, He big-noted himself as being “Personally This” and “Personally That“ [Note: When meeting Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, director-general of the WHO, on 29 January, Xi made a point of saying that he was “personally commanding” the response to the outbreak, a statement that was widely derided online]. They were vacuous claims that merely served to highlight His hypocrisy. Such claims excited nationwide outrage and sowed desolation in the hearts of the people.

It is true: the present level of popular fury due to the handling of the epidemic is volcanic; a people thus enraged may, in the end, also cast aside their fear. Herein I offer my analysis of these developments in a broader context. Mindful of the cyclical nature of the political Zeitgeist, and with an unswerving eye fixed on what has been unfolding here in China since 2018 [when Xi Jinping was granted limitless tenure and the author published his famous broadside against the Party-State], I have formulated my thoughts under nine headings. Compatriots: I respectfully offer them here for your consideration.

豕鼠交替之際,九衢首疫,舉國大疫,一時間神州肅殺,人心惶惶。公權進退失據,致使小民遭殃,疫癘散布全球,中國漸成世界孤島。此前三十多年「改革開放」辛苦積攢的開放性狀態,至此幾乎毀於一旦,一巴掌把中國尤其是它的國家治理打回前現代狀態。而斷路封門,夾雜著不斷發生的野蠻人道災難,跡近中世紀。原因則在於當軸上下,起則鉗口而瞞騙,繼則諉責卻邀功,眼睜睜錯過防治窗口。壟斷一切、定於一尊的「組織性失序」和只對上負責的「制度性無能」,特別是孜孜於「保江山」的一己之私而置億萬國民於水火的政體「道德性敗壞」,致使人禍大於天災,在將政體的德性窳敗暴露無遺之際,抖露了前所未有的體制性虛弱。至此,人禍之災,於當今中國倫理、政治、社會與經濟,甚於一場全面戰爭。再說一遍,甚於一場全面戰爭。此可謂外寇未逞其志,而家賊先禍其國。老美或有打擊中國經濟之思,不料當軸急先鋒也。尤其是疫癘猖獗當口,所謂「親自」云云,心口不一,無恥之尤,更令國人憤慨,民心喪盡。

是的,國民的憤怒已如火山噴發,而憤怒的人民將不再恐懼。至此,放眼世界體系,揆諸全球政治週期,綜理戊戌以來的國情進展,概略下述九項,茲此敬呈國人。

1. Politics in a New Era of Moral Depletion

First and foremost, I would posit that the political life of the nation is in a state of collapse and that the ethical core of the system has been rendered hollow. The ultimate concern of China’s polity today and that of its highest leader is to preserve at all costs the privileged position of the Communist Party and to maintain ruthlessly its hold on power. What they dub “The Broad Masses of People” are nothing more than a taxable unit, a value-bearing cipher in a metrics-based system of social management that is geared towards stability maintenance. [Note: ‘Stability maintenance’ 維穩, short for ‘protecting the national status quo and the overall stability of society’ 維護國家局勢和社會的整體穩定, is a term that includes the deployment of paramilitary forces, police, local security officials, neighborhood committees, informal community spies, Internet police and censors, secret service agents and watchdogs as well as everyday bureaucratic monitors who hold a brief to be ever vigilant and to maintain order and control over every aspect of society. This is part of China’s “forever war” against its own citizens.]

“The People” is a rubric that describes the price everyone has to pay to prop up the existing system. We are funding the countless locusts—large and small—whose survival is supported by a totalitarian system. The storied bureaucratic apparatus that is responsible for the unfettered outbreak of the coronavirus in Wuhan repeatedly hid or misrepresented the facts about the dire nature of the crisis. The dilatory actions of bureaucrats at every level exacerbated the urgency of the situation. Their behavior has reflected their complete lack of interest in the welfare and the lives of normal people. What is of consequence for them is their tireless support for the self-indulgent celebratory behavior of the “Core Leader” whose favor is constantly sought through their adulation for the peerless achievements of the system. Within such a self-regarding bureaucracy there is even less interest in the role that this country and its people can and should play in a globally interconnected community.

Those shameless bureaucrats allowed the situation to deteriorate to such an extent that they were directly harming average people. Meanwhile, “The Core” was steadfast as inefficiencies and chaos proliferated. Instead they focused particular attention on policing the Internet: They unleashed the dogs and have been paying their minions overtime to blockade the news of what is actually happening. Information has been getting out regardless, proof that even though the government is employing the tactics of a police state, and while the National Security Commission [the supreme policing agency created by Xi Jinping in November 2013] amasses ever greater powers, it can never truly achieve its vaunted aims.

The ancients observed that “it’s easier to dam a river than it is to silence the voice of the people.” Regardless of how good they are at controlling the Internet, they can’t keep all 1.4 billion mouths in China shut. Yet again, our ancestors will be proved right. Nonetheless, since all of their calculations are solely made on the basis of maintaining control, they have convinced themselves that such crude exercises of power will suffice. They have been fooled by the self-deception of “The Leader,” but theirs is a confidence that deceives no one. Faced with this virus, the Leader has flailed about seeking answers with ever greater urgency, exhausting those who are working on the front line, spreading the threat to people throughout the land. Ever more vacuous slogans are chanted—Do this! Do that!—overweening and with prideful purpose, He garners nothing but derision and widespread mockery in the process. This is a stark demonstration of the kind of political depletion that I am addressing here. The last seven decades [of the People’s Republic] have taught the people repeated lessons about the hazards of totalitarian government. This time around, the coronavirus is proving the point once more, and in a most undeniable fashion.

One can only hope that our fellow Chinese, both young and old, will finally take these lessons to heart and abandon their long-practiced slavish acquiescence. It is high time that people relied on their own rational judgment and refused to sacrifice themselves again on the altar of the power holders. Otherwise, you will all be no better than fields of garlic chives; you will give yourselves up to being harvested by the blade of power, now as in the past. [Note: The term “garlic chives,” 韭菜 or Allium tuberosum, is used as a metaphor to describe the common people who are regarded by the power-holders as an endlessly renewable resource.]

首先,政治敗壞,政體德性罄盡。保家業、坐江山,構成了這一政體及其層峰思維的核心,開口閉口的「人民群眾」不過是搜刮的稅收單位,數目字管理下的維穩對象和「必要代價」,供養著維續這個極權政體的大小無數蝗蟲。公權上下隱瞞疫情,一再延宕,只為了那個圍繞著「核心」的燈紅酒綠、歌舞昇平,說明心中根本就無生民無辜、而人命關天之理念,亦無全球體系中休戚相關之概念。待到事發,既丟人現眼,更天良喪盡,遭殃的是小民百姓。權力核心仍在,而低效與亂象並生,尤其是網警效命惡政,動如鷹犬,加班加點封鎖信息,而信息不脛而走,說明特務政治臨朝,國安委變成最具強力部門,雖無以復加,卻已然前現代,有用復無用矣。其實,老祖宗早已明言,防民之口甚於防川,哪怕網信辦再有能耐,也對付不了十四萬萬張嘴,古人豈余欺哉!蓋因一切圍繞江山打轉,自以為權力無所不能,沈迷於所謂「領袖」之自欺,而終究欺瞞不住。大疫當前,卻又毫無領袖德識,捉襟見肘,累死前方將士,禍殃億萬民眾,卻還在那裡空喊政治口號,這個那個,煞有介事,令國人齒冷,讓萬方見笑。此亦非他,乃政體之「道德性敗壞」也。若說七十年里連綿災難早已曉瑜萬眾極權之惡,則此番大疫,更將此昭顯無遺。惟盼吾族億萬同胞,老少爺們,長記性,少奴性,在一切公共事務上運用自己的理性,不要再為極權殉葬。否則,韭菜們,永難得救。

2. Tyranny in a New Era of Political License

Secondly, tyranny ultimately corrupts the structure of governance as a whole and it is undermining a technocratic system that has taken decades to build. There has been a system-wide collapse of professional ethics and commitment.

There was a time, not too long ago, when individual moral imperatives found fellowship with systemic self-interest in a way that led to a vast corps of competent technocrats taking the stage. Over time, they formed a highly capable coterie of specialists and administrators even though, as anyone would readily admit, the process also resulted in managerial arrangements that were far from ideal. After all, China’s new technocracy was riven by its limitations and beset by serious problems of every kind. Nonetheless, one of the reasons that the technocratic class evolved and managed to function at all was that by instituting administrative competence within a system that allowed for personal advancement on the basis of an individual’s practical achievements in government, countless young men and women from impoverished backgrounds were lured to pursue self-improvement through education. They did this in order to devote themselves both to meaningful and rewarding state service. Of course, at the same time, the progeny of the Communist Party’s own nomenklatura—the so-called “Red Second Generation” of bureaucrats—proved themselves to be all but useless as administrators; they occupied official positions and enjoyed the perks of power without making any meaningful contribution. In fact, more often than not, they simply got in the way of people who actually wanted to get things done. But enough of that.

Unfortunately, as a result of the endless political purges of recent years [carried out by Xi Jinping and his deputy Wang Qishan in the name of an “anti-corruption campaign”] and along with the revival of “Red Culture,” the people in the system who have now been promoted are in-house Party hacks who slavishly obey orders. Consequently, both the kind of professional commitment and expertise previously valued within the nation’s technocracy, along with the ambition people previously nurtured to seek promotion on the basis of their actual achievements, have been gradually undermined and, with no particular hue and cry, they have now all but disappeared. The One Who Must Be Obeyed who talks about the importance of transmitting “red genes” through a reliable Party body politic, the man with the ultimate decision-making power and sign-off authority, has created an environment in which the system as a whole has fallen into desuetude. What’s left is a widespread sense of hopelessness.

The bureaucratic and governance system of China that is now fully on display is one that values the mediocre, the dilatory and the timid. The mess they have made in Hubei Province, and the grotesque posturing of the incompetents involved [in dealing with the coronavirus] have highlighted a universal problem. A similar political malaise infects every province and the rot goes right up to Beijing. In what should be a “post-leader era,” China has instead a “Core Leader system” and it is one that is undermining the very mechanisms of state. Despite all the talk one hears about “modern governance,” the reality is that the administrative apparatus is increasingly mired in what can only be termed inoperability. It is an affliction whose symptoms I encapsulate in the expressions “organizational discombobulation” and “systemic impotence.”

Don’t you see that although everyone looks to The One for the nod of approval, The One himself is clueless and has no substantive understanding of rulership and governance, despite his undeniable talent for playing power politics. The price for his overarching egotism is now being paid by the nation as a whole. Meanwhile, the bureaucracy drifts directionless, although the best among them try to get by as best they can. They would like to take positive action, but they are hesitant and fearful. For their part, meanwhile, bureaucratic schemers avail themselves of the muddle and, although they have no motivation to be proactive, they are quite good at making trouble. The situation works to their advantage; they shove the competent bureaucrats aside and create in their place an environment of overall chaos.

其次,僭主政治下,政制潰敗,三十多年的技術官僚體系終結。曾幾何時,在道德動機和利益動機雙重驅動下,一大批技術官僚型幹才上陣,而終究形成了一種雖不理想、弊端重重、但卻於特定時段頂事兒的技術官僚體系。其間一大原因,就在於掛鈎於職位升遷的政績追求,激發了貧寒子弟入第後的獻身衝動。至於乘勢而上的紅二們,從來屍位素餐,酒囊飯袋,成事不足敗事有餘,在此不論。可惜,隨著最近幾年的不斷整肅,紅色江山老調重彈,只用聽話的,自家的,其結果,技術官僚體系的德性與幹才,其基於政績升遷的那點兒衝動,不知不覺,乃消失殆盡。尤其是所謂「紅色基因」的自家人判准及其圈定,讓天下寒心而灰心,進而,離德離心。於是,這便出現了官場上普遍平庸而萎頓委瑣之態。鄂省亂象,群魔亂舞,不過一隅,其實省省如此,舉朝如此矣。其間原因,就在於這個後領袖時代,領袖制本身就在摧毀治理結構,口言現代治理卻使整個國家治理陷入無結構性之窘境。此間症狀,正為「組織性失序」和「制度性無能」。君不見,惟一人馬首是瞻,而一人暝朦,治國無道,為政無方,卻弄權有術,遂舉國遭罪。百官無所適從,善者只堪支應,想做事而不敢做事,惡者混水摸魚,不做事卻還攪事,甚而火中取栗,遂劣勝優汰,一團亂象矣。

3. A New Era of Attenuated Governance

Furthermore, the day-to-day governance of China is in a state of terminal decay. This manifests itself in two ways:

In the first place, the economic slowdown is now an undeniable reality, and all indications are that things will only get worse over the current year. This presents the nation with a situation unrivaled since the economic downturn that followed the 1989 “disturbances” [that is, the 4 June Beijing Massacre]. Such a situation will only serve to exacerbate further the aforementioned “organizational discombobulation” and “systemic impotence.” Equally undeniable is the state of things more broadly including:

- A collapse in consumer confidence;

- Widespread panic about the longterm security of private property;

- Administrative and academic frustration and pent-up anger;

- A general shutting down of society as a whole; and,

- A depressed cultural and publishing industry.

What is thriving, however, is all that ridiculous “Red Culture” and the nauseating adulation that the system heaps on itself via shameless pro-Party hacks who chirrup hosannahs at every turn.

Of particular and profound concern are the massive political miscalculations that have been made: first, regarding the uprising in Hong Kong; and, then, in forecasts about the elections in Taiwan. The political problems [in Hong Kong] are the product of a blatant refusal to abide by the undertaking stipulated in the Hong Kong Basic Law regarding general elections [for the Chief Executive of the territory]. Repeated missteps in the Special Administrative Zone have been followed by clumsy and haphazard moves that have led to the complete collapse of public confidence in the territory’s political leadership. The upshot is a fundamental disaffection towards Beijing among the masses of a place that is, if truth be told, the most prosperous and civilized part of China’s territory. The whole world has witnessed the ugly reality of the polity that lurks behind this situation.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the Pacific Ocean, as the Sino-American relationship continues into uncharted territory, the fact that for the Superpower politics are not merely about grand claims that no one has a right to comment on the internal affairs of such nations, all of these happenings [in Hong Kong and Taiwan, which Beijing emphasizes are solely China’s “internal affair”] have a direct impact on the unfolding fate of our own nation. It is at this very juncture that The Axelrod, befuddled as usual, is for his pains also having to deal with an America led by a man who repeatedly “trumps” him by virtue of his own unpredictability [Note: Here the author alters the Chinese transliteration of Trump’s name to read “extremely befuddling,” that is someone who “stumps” everyone]. What you end up with is an unholy mess. There is a proliferation of online comments claiming that through His actions He is actually aiding and abetting the Yankees pursue their “Imperialist Steadfast Desire to See Us Destroyed.” In other words, [canny commentators are suggesting that] He is helping the U.S. achieve the very things it could never have dreamed of accomplishing itself. This is not just a way of ridiculing Him, it is a profoundly painful reality for all of us.

Secondly, the power holders have in recent years accelerated their efforts to stamp out anything that resembles or contributes to the existence of civil society in China. Censorship increases by the day, and the effect of this is to weaken or obliterate those very things that can and should play a positive role in alerting society to critical issues [of public concern]. In response to the coronavirus, for instance, at first the authorities shut down all hints of public disquiet and outspoken commentary via censorship; they then simply shut down entire cities. First people’s hearts die and then Death stalks the living. It takes no particular leap of the imagination to appreciate that along with such acts of crude expediency a soulless pragmatism can make even greater political inroads. Given the fact that the country is, in effect, run by people nurtured on the “Politics of the Sent Down Youth” [that is, of the Cultural Revolution era—today’s leaders came of age during the late 1960s and early 1970s, a period of unparalleled political cynicism] this is hardly remarkable. After all, we are living in a time when what once passed for a measure of public decency and social concern has long quit the stage.

One could go so far as to say that from the highest echelon to the very bottom of the system, this lot [of leaders in power today] represent the worst political team to have run China since 1978. That is why I believe that it is imperative that the nation act on and truly put into practice Article 35 of the Constitution. That is to say [we ourselves should advance Five Key Demands]:

- Lift the ban on independent media and publishing;

- Put an end to the secret police surveillance of the Internet and allow people their right to freedom of speech so they can express themselves with a clear conscience;

- Allow citizens to enjoy their right to demonstrate as well as the freedom of assembly and association;

- Respect the basic universal rights of our citizens, in particular their right to vote in open elections.

[And, fifthly,] It should also be a matter of pressing urgency that an independent body be established to investigate the origins of the coronavirus epidemic, to trace the resulting cover-up, identify the responsible parties and analyze the systemic origins of the crisis. Then and only then [after the coronavirus epidemic has passed] can we truly engage in what should be a meaningful “Post [Anti-Virus] War Reconstruction.”

再次,內政治理全面隳頹。由此急轉直下,遂表現為下述兩方面。一方面,經濟下滑已成定勢,今年勢必雪上加霜,為「風波」以來所未有,將「組織性失序」和「制度性無能」推展至極。至於舉國信心下跌、產權恐懼、政學憤懣、社會萎縮、文化出版蕭條,惟剩狗屁紅歌紅劇,以及無恥文痞歌功頌德之肉麻兮兮,早成事實。而最為扼腕之處,則為對於港台形勢之誤判,尤其是拒不兌現基本法的普選承諾,著著臭棋,致使政治公信力跌至谷底,導致中國最為富庶文明之地的民眾之離心離德,令世界看清這一政體的無賴嘴臉。那邊廂,中美關係失序,而基於超級大國沒有純粹內政的定律,這是關乎國運之犖犖大端。恰恰在此,當軸顢頇,再加上碰到個大洋國的特沒譜,遂一塌糊塗。網議「帝國主義亡我之心不死」,想做而沒做成的事,卻讓他做成了,豈只調侃,而實錐心疼痛也哉。另一方面,幾年來公權加緊限制與摧毀社會發育,鉗口日甚,導致社會預警機制疲弱乃至於喪失,遇有大疫,便從封口而封城,死心復死人矣。因而,不難理解的是,與此相伴而來的,便是政治市儈主義與庸俗實用主義蔓延政治,無以復加,表明作為特殊時段的特殊現象登場的「知青政治」,早已德識俱亡。可以說,上上下下,他們是四十年來最為不堪的一屆領導。因而,此時此刻,兌現《憲法》第35條,解除報禁,解除對於網絡的特務式管控,實現公民言論自由和良心自由,坐實公民遊行示威和包括結社在內的各項自組織權利,尊重全體國民的普遍人權,特別是政治普選的權利,而且,對於病毒的來源、隱瞞疫情的責任人及其體制性根源,啓動獨立追責機制,才是「戰後重建」之大道,也是當務之急也。

4. A New Era of Revived Court Politics

Then there is the re-emergence of court politics or palace intrigue. The lurch towards the totalitarian in recent years along with a concomitant ratcheting up of policies aimed at insinuating the Communist Party into every aspect of civil government has, as we have noted in the above, resulted in the near paralysis of normal bureaucratic operations. The system lacks any real sources of positive motivation and the concentration of authority along with the concomitant impotence of actual power means that the Tail [or underlings] can all too readily Wag the Dog—ergo the existence of a Security Commission that imposes harsh punishments as part of the overall mechanisms that have to be used to keep the show on the road and the bureaucratic game ticking over. Due to the lack of freedom of speech and the absence of a modern bureaucratic system, let alone the absence of anything even approaching a “His Majesty’s Loyal Opposition,” the whip itself knows no restraint and the National Security Commission [established by Xi] rules with an iron fist, each layer of bureaucracy answering upwards until it reaches the pinnacle, The Sole Responsible Person. And that individual is but a man of flesh and blood who cannot possibly “be across” all aspects of governance.

A Party-State system that has no checks or balances, one that actually resists the rational allocation of duties and responsibilities, invariably gives rise to the rule of a clique of trusted lieutenants. Hence we have seen the equivalent of a court emerge and the political behavior endemic to a court. To put it more clearly, the “collective leadership” with its “Nine Dragons Ruling the Waters” [Note: Prior to the Xi Jinping era, there were nine members of the ruling Politburo Standing Committee. Xi’s leadership saw this number reduced to seven] and its concomitant claque of rulers acting in an equilibrium is no longer operable. With the over concentration of power and a relative decline in efficacy, the One Leader’s inner circle becomes a de facto “state within a state,” something that the Yankees have taken to calling the “deep state.”

Following the founding of the People’s Republic in 1949, a non-party bureaucracy was established which was empowered to carry out basic administrative tasks. Even Mao was able to tolerate someone like Premier Zhou Enlai running his part of the government. With the appearance of the Revolutionary Committees and Security Organs [which replaced the police and the judicial system as a whole during the Cultural Revolution, from 1966 until the 1970s] that system was overthrown. In the four decades [after Cultural Revolution policies were formally rejected from 1978], for the most part a modicum of balance existed between the roles of Party leader and state leader [that is, between the General Secretary of the Communist Party and the Premier who, as head of the State Council, was in charge of the formal structures of government]. Even though the Party and State were still melded, the state bureaucracy was given the task of implementing Party directives. It is only in the last few years that a new kind of hermetically sealed governance has come to the fore and, because of the nature of hidden court politics, it is one that has further enabled the sole power-holder while granting license to the darkest kinds of plotting and scheming. Such a rulership structure stifles systemic innovation and forecloses the kinds of changes that might enhance regularized forms of governance. With the way ahead reduced to something akin to a “political locked-in syndrome,” and since a meaningful retreat is all but impossible, the system is put under constant strain. It is virtually impossible for anyone to act in any meaningful fashion. Instead, all are forced to look on in impotent frustration as things deteriorate. This may well continue until the situation is simply beyond salvaging.

Faced with all of this, the social economy itself is left in tatters; the basic ethical skein of society as a whole is rent by the changing winds of political fashion, so much so that people’s already fragile sense of citizenship is further depleted. In the absence of anything that can meaningfully be called civil society, there is no hope that a mature form of politics can possibly evolve. The brittleness of the situation is such that, whenever there is the slightest disturbance—let alone a major disaster—everyone and everything is endangered; we are all powerless to help each other. In such circumstances, what may start out as a molehill can all too readily burgeon into a mountain.

The present chaos in Wuhan has thrown Hubei into confusion, but as we noted earlier, the root cause of the expanding problem lies in Beijing: The One who devotes himself energetically to “Protecting the Mountains and Rivers and Maintaining Rulership Over the Mountains and Rivers” [of China. Note: “Rivers and Mountains” is a poetic expression for China as a unified entity under authoritarian control]. His self-interest is not grounded in the sovereignty of the people, nor in a system of governance that is about “building a nation on the basis of civilization, or freedom.” The end result of His style of rulership is, as commentators on the Internet have widely remarked of late, that although “Major Tasks Can Be Accomplished by Concentrating Power” in times of crisis the reality is that “Major Mishaps Are Also Generated by Overly Concentrated Power.” The coronavirus epidemic is a clear demonstration of this.

復次,內廷政治登場。幾年來的集權行動,黨政一體之加劇,特別是以黨代政,如前所述,幾乎將官僚體制癱瘓。動機既靡,尾大不掉,遂以紀檢監察為鞭,抽打這個機體賣命,維續其等因奉此,逶迤著拖下去。而因言論自由和現代文官體制闕如,更無所謂「國王忠誠的反對者」在場,鞭子本身亦且不受督約,復以國安委一統轄制下更為嚴厲之鐵腕統領,最後層層歸屬,上統於一人。而一人肉身凡胎,不敷其用,黨國體制下又無分權制衡體制來分責合力,遂聚親信合議。於是,內廷生焉。說句大白話,就是 「集體領導」分解為「九龍治水」式寡頭政制失效、相權衰落之際,領袖之小圈子成為「國中之國」,一個類似於老美感喟的隱形結構。揆諸既往,「1949政體」常態之下,官僚體系負責行政,縱便毛時代亦且容忍周相一畝三分地。「革委會」與「人保組」之出現,打散這一結構,終至不可維持。晚近四十年里,多數時候「君相」大致平衡,黨政一體而借行政落實黨旨。只是到了這幾年,方始出現這一最為封閉無能、陰鷙森森之內廷政治,而徹底堵塞了重建常態政治之可能性也。一旦進路閉鎖,彼此皆無退路,則形勢緊繃,大家都做不了事,只能眼睜睜看著情形惡化,終至不可收拾之境。置此情形下,經濟社會早已遭受重創,風雨飄搖於世俗化進程中的倫理社會不堪托付,市民社會羸弱兮兮,公民社會根本就不存在,至於最高境界的政治社會連個影子都沒有,則一旦風吹草動,大災來臨,自救無力,他救受阻,必致禍殃。此番江夏之亂,現象在下,而根子在上,在於這個孜孜於「保江山,坐江山」,而非立定於人民主權、「以文明立國,以自由立國」的體制本身。結果,其情其形,恰如網議之「集中力量辦大事」,頓時變成了「集中力量惹大事」。江夏大疫,再次佐證而已矣。

5. A New Era of Big Data Totalitarianism and WeChat Terror

They now pursue their rule over the people via what I would call “big data totalitarianism” and “WeChat terror.” Although the Communist Party has formulated its ideology in various guises over the decades, it has not fundamentally changed. That is how the nationalism that underpins their enterprise is presently cast in terms of “the revitalization of the great Chinese nation,” while the broad-based aspiration for national wealth and power was formulated [in the 1970s] under the slogan of “[achieving] the Four Modernizations” [of agriculture, industry, defense and science and technology]. Twists and turns have followed one upon another, including such ideological formulations as the Three Represents [of the Jiang Zemin era that stated that the Party “represents the means for advancing China’s productive forces; represents China’s culture; and, represents the fundamental interests of the majority of the Chinese people] and the The New Three People’s Principles [reformulated in the early 2000s on the basis of ideas first articulated in the Republican period, 1912-1949] right up to the “New Era” announced under Xi Jinping [and written into the Communist Party Constitution in late 2017].

The Three Represents and the ideas [and policy latitude of the time] expressed the relative apogee of possibility under the Communists; since then there has been an evident downward curve which, in recent years, is evidence that the Party is increasingly obsessed with maximum control over their “Rivers and Mountains.” To that end, they are now evolving a form of big data totalitarianism. Of course, the relative move away from the totalitarian controls of the Maoist era [during the 1980s and 1990s] seemed at the time to presage some hope that the system as a whole might actually be able to transition into something else. Following the 2008 Beijing Olympics, however, that trend petered out as Maoist-style forms of social control were gradually re-instituted. That trend has been more evident over the past six years [under Xi Jinping].

Unlimited government budgets have funded technological developments that are turning China into a mega data totalitarian state; we are already subjected to a 1984-style of total surveillance and control. This state of affairs has enabled what could be called “WeChat terrorism” which directly targets the country’s vast online population. Through the taxes the masses are, in fact, funding a vast Internet police force dedicated to overseeing, supervising and tracking everyone and all of the statements and actions they author. The Chinese body politic is riven by a new canker, but it is an infection germane to the system itself. As a result, people live in a state of constant anxiety; they are keenly aware that the Internet terrorism is by no means merely limited to personal WeChat accounts being suspended or shut down entirely, nor to the larger enterprise of banning entire WeChat groups [which are a vital way for individuals to debate issues of interest]. Everyone knows that the online terror may readily escape the virtual realm to become overtly physical: that is when the authorities use what they have learned online to send in the police in real-time. Widespread anxiety leads to relentless self-censorship; people are beset by nagging fears about what inexplicable punishment may suddenly befall them.

As a result, the potential for meaningful public discussion [of issues of the day, including the coronavirus] is stifled. By the same token, the very channels of communication that should in normal circumstances exist for the dissemination of public information are choked off, and a meaningful, civic early-warning system that could play a crucial role at times of local or national emergency is thereby outlawed. In its place we have an evolving form of military tyranny that is underpinned by an ideology that I call “Legalistic-Fascist-Stalinism” [Fa-Ri-Si 法日斯], one that is cobbled together from strains of traditional harsh Chinese Legalist thought [Fa 法; that is, 中式法家思想] wedded to an admix of the Leninist-Stalinist interpretation of Marxism [Si 斯; 斯大林主義] along with the “Germano-Aryan” form of fascism [Ri 日; 日耳曼法西斯主義]. There is increasing evidence that the Party for all of its weighty presence, is in fact a self-deconstructing structure that constantly undermines normal governance while tending towards systemic atrophy. Therefore, when a political arrangement like the one I have been describing here is confronted by a major public health emergency, as is now the case, the so-called “All Powerful Totalizing System” under the Chairman of Everything produces real-world effects that expose the profound inadequacies of the system as a whole. Among other things, it has left the country without even enough face masks to go around.

As I write these words, in the city of Wuhan, and within the province of Hubei, there are still countless numbers of people unable to get adequate medical attention, people who have been abandoned as they wail in hopeless isolation. Will we ever know how many people have as a result been condemned to a premature death? This is the reality of the so-called “all-powerful state;” its “good-for-nothing” nature is now on display for all to see. China’s party-state system that has systematically outlawed society itself, as well as the civic realm [this is a translation of the capacious term minjian; for more on this, see Sebastian Veg, Minjian: Rise of China’s Grassroots Intellectuals], cut off all sources of information apart from its own and given sole license to its own propaganda apparatus. A nation like this may well attempt to strut, but the reality is that it is little more than a crippled giant, if it can even be called a giant.

第五,以「大數據極權主義」及其「微信恐怖主義」治國馭民。過往三十多年,在底色不變的前提下,官方意識形態口徑經歷了從「振興中華」的民族主義和「四化」的富強追求,到「三個代表」和「新三民主義」,再至「新時代」云云的第次轉折。就其品質而言,總體趨勢是先升後降,到達「三個代表」拋物線頂端後一路下走,直至走到此刻一意赤裸裸「保江山」的「大數據極權主義」。相應的,看似自毛式極權向威權過渡的趨勢,在「奧運」後亦且止住,而反轉向毛氏極權回歸,尤以晚近六年之加速為甚。因其動用奠立於無度財政汲取的科技手段,這便形成了《1984》式「大數據極權主義」。緣此而來,其「微信恐怖主義」直接針對億萬國民,用納稅人的血汗豢養著海量網警,監控國民的一言一行,堪為這個體制直接對付國民的毒瘤。而動輒停號封號,大面積封群,甚至動用治安武力,導致人人自危,在被迫自我審查之際,為可能降臨的莫名處罰擔憂。由此窒息了一切公共討論的思想生機,也扼殺了原本應當存在的社會傳播與預警機制。由此,「基於法日斯主義的軍功僭主政治」漸次成型,卻又日益表現出「組織性失序」和「制度性無能」,其非結構性與解結構性。職是之故,不難理解,面對大疫,無所不能的極權統治在赳赳君臨一切的同時,恰恰於國家治理方面居然捉襟見肘,製造大國一時間口罩難求。那江夏城內,鄂省全境,至今尚有無數未曾收治、求醫無門、輾轉哀嚎的患者,還不知有多少因此而命喪黃泉者,將此無所不能與一無所能,暴露得淋灕盡致。蓋因排除社會與民間,斬斷一切信息來源,只允許黨媒宣傳,這個國家永遠是跛腳巨人,如果確為巨人的話。

6. A New Era That Has Shut Down Reform

The last cards in the deck have been played and the possibilities for further meaningful reforms have been locked out. Or, to put it more directly, the Open Door and Economic Reform policies are dead in a ditch. From when [Xi Jinping declared], in late 2018 that “we must resolutely reform what should and can be changed, we must resolutely not reform what shouldn’t and can’t be changed” right up to the publication of the Communiqué of the Fourth Plenary Session [of the Nineteenth Party Congress] last autumn, we can definitely say that the Third Great Wave of reform and opening in modern Chinese history [the first wave dates from the self-strengthening movement of the 1860s] has now petered out. In reality, the process of shutting down reform started six years ago [following the rise of Xi Jinping in late 2012].

Observing the trends in global history throughout the 20th century it is fairly evident that right-wing governments have proven, when forced by pressure or circumstance, that they may be able to evolve and overcome their internal systemic dilemmas without always having to resort to mass blood-letting. Even in the case of the “Eastward Wave of Soviet Change” [Su Dong Bo, literally “the (politically transformative) wave that broke over the Eastern Bloc controlled by the Soviet Union.” This clever shorthand is based on the name “Su Dongpo,” a famous Song-dynasty poet]—in particular in the case of the socialist governments of the Eastern Bloc under Soviet control—even they managed a peaceful transition, something that, at the time, was both surprising and a relief. However, in China today, the authorities have blocked off all possible roads that may potentially lead to positive change. We must seriously doubt whether any form of peaceful transition might now even be conceivable. If that is the case, one cannot help but think of the old poetic line [from the Yuan dynasty] that, “The people suffer whether the state prospers or fails.” We can only hope that in the wake of the coronavirus, the people of China will reconsider their situation and that this ancient land will awaken to its predicament. Might it, perhaps, be possible to initiate a Fourth Wave of Reform?!

第六,底牌亮出,鎖閉一切改良的可能性。換言之,所謂的「改革開放」死翹翹了。從2018年底之「該改的」、「不該改的」與「堅決不改」云云,至去秋十九屆四中全會公報之諸般宣示,可得斷言者,中國近代史上的第三波「改革開放」,終於壽終正寢。其實,這一死亡過程至少起自六年前,只不過至此算是明示無誤而已。回頭一望,二十世紀全球史上,但凡右翼極權政治,迫於壓力,皆有自我轉型的可能性,而無需訴諸大規模流血。縱便是「蘇東波」,尤其是東歐共產諸國等紅色極權政體,居然亦且和平過渡,令人詫異而欣慰。但吾國刻下,當局既將路徑鎖閉,則和平過渡是否可能,頓成疑問。若果如此,則「興,百姓苦;亡,百姓苦」,夫復何言!但願此番大疫過後,全民反省,舉國自覺,看看尚能重啓「第四波改革開放」否!?

7. A New Era of Isolation

Given the logical unfolding of things discussed in the foregoing, China looks like it will, once more, be isolated from the global system. The modern global system is one that took shape in the Mediterranean [with the rise of the European trading powers] and reached an apogee on either side of the Atlantic Ocean [with the imperial dominance of the United Kingdom and the United States]. Over the centuries, China has engaged in endless tugs of war with that system, rejecting or embracing it at various times. Back and forth it has gone as the nation has lurched one way and careened another over the years. For over three decades [from 1978 to 2008], a hard-won and painful realization led to this country to “bow in humble acknowledgement” [as the author titled an essay in late 2018] as well as “actively pursue change,” right up to giving birth to its own new form of engagement with the world system that would, over time, become itself something of a new mainstream.

It is a sad reality, however, that in recent years China has increasingly acted imprudently and against its own best interests. Furthermore, the “Open Door” has evidently opened just about far as it is going to; the totalitarian impulses of the Extreme Leftists have led them to take a stand; they will not tolerate any kind of systemic evolution that could possibly lead to a peaceful transition and enable China finally to evolve [away from authoritarianism and the one-party state]. That’s why this place has repeatedly found itself at loggerheads with the modern global system. Despite this, and after all the to-ing and fro-ing, by virtue of its sheer scale and as a result of a generally more open mindset China was fitfully finding its place in the modern world system and even becoming an important player in it. Its mere global presence also forced people to engage with new interpretations of staid geopolitical narratives about the meaning of “the center” and “the periphery” [China and other economies like it having been traditionally regarded as peripheral actors in the world system, in recent decades the “centre” of geopolitical concerns has shifted].

In recent years, however, the country’s increasingly aggressive international posture has been out of kilter both with realistic assessments of China’s actual national strength as well as the trends in global affairs as a whole. Added to all of that has been the changing internal dynamics of China itself, dynamics that have seen a steady drumbeat egg on the regime of “Legalistic-Fascist-Stalinism.” All of this taken as a whole has elicited alarm and trepidation among other players in the new great game of global politics; they are now alert to the potential rise of a Chinese “Red Empire” [for more on this, see Xu, “China’s Red Empire—To Be or Not To Be”]. Just as China has been trumpeting the concept of a global Community of Shared Destiny [since late 2013], the international community rejects it. What a tragic irony! Instead of embracing a real community, China is increasingly isolating itself from it.

No matter how complex, nuanced and sophisticated one’s analysis, the reality is stark. A polity that is blatantly incapable of treating its own people properly can hardly be expected to treat the rest of the world well. How can a nation that doggedly refuses to become a modern political civilization really expect to be part of a meaningful community? That’s why although mutually beneficial economic exchanges will continue unabated, China’s civilizational isolation will remain an undeniable reality. This has nothing to do with a culture war, even less can it be encapsulated in—and dismissed by—such glib concepts as a “clash of civilizations.” Nor is this situation simply a matter of a new wave of anti-Chinese sentiment, or Sinophobia or a desire to put China down. I say that despite the fact that, for the moment, dozens of countries have imposed travel restrictions on people from the People’s Republic.

Nonetheless, I would remind readers that as the present China scare increases talk about the threat of a “Yellow Peril,” that long occluded and sclerotic ideological construct, must invariably intensify . Internationally, the due appreciation for universal values and human rights was hard won and it only achieved widespread acceptance following a tortuous period of contestation. These concepts have long been a standard element in the treaties and agreements that underpin the international community. China’s own international engagement and its worthiness of enjoying a substantive place in the international community depend too on how these philosophical issues are understood and treated [that is, if the People’s Republic can evolve and accept internationally recognized rights and universal values, which at present are rejected as a threat to Party domination in China]. Over time who will prosper and who will move against the tides of history—that is, who will end up being isolated—these are questions that can only be answered in the process of some places being isolated by others or as a result of those states that decide to self-isolate and end up alone. Those nations [and here the author is thinking of China] may end up appreciating their assumed pulchritude as reflected back at them in the mirror of their imperial self-regard.

The way to turn things around, to re-establish the image of China as a responsible major power that can shoulder its global responsibilities, requires that the internal affairs of this country must be set in order, but that can only happen if we as a people join together on the Great Way of Universal Human Values. Of particular importance is that this nation has to ground itself substantively in the political concept that Sovereignty Resides in the People. It all comes down to how this country chooses to manage its own affairs. I believe that the only way for China to end its global and historical isolation and become a meaningful participant in the global system, as well as flourish on the path of national survival and prosperity, is to pursue a politics that both embraces constitutional democracy and fosters a true people’s republic. When that time comes, and in accord with the flow of events, it is not unimaginable that China might even be worthy of joining the G7, which would as a result become the Group of Eight or G8.

第七,由此順流直下,中國再度孤立於世界體系,已成定局。百多年里,對於這個起自近代地中海文明、盛極於大西洋文明的現代世界體系,中國上演了多場「抗拒」與「順從」的拉鋸戰,反反復復,跌跌撞撞。晚近三十多年里,痛定思痛,「低頭致意」以及「迎頭趕上」,乃至於「別開生面」,蔚為主流。惜乎近年再度犯二,犯橫,表明「改開」走到頭了,左翼極權「退無可退」,無法於和平過渡中完成自我轉型,因而,也就怪異於現代世界體系。雖則如此,總體而言,幾番拉鋸下來,中國以其浩瀚體量與開放性態度,終於再度躋身現代世界體系,成為這個體系的重要博弈者,重新詮釋著所謂「中心—邊緣」的地緣敘事,也是事實。但是,與國力和時勢不相匹配、太過張揚的外向型國策,尤其是內政回頭,日益「法日斯化」,引發這個體系中的其他博弈者對於紅色帝國崛起的戒慎戒懼,導致在高喊「人類命運共同體」之際卻為共同體所實際拒斥的悲劇,而日呈孤立之勢,更是眼面前的事實。事情很複雜而道理卻很簡單,一個不能善待自己國民的政權,怎能善待世界;一個不肯融入現代政治文明體系中的國族,你讓人怎麼跟你共同體嘛!故爾,經濟層面的交通互存還將繼續存在,而文明共同體意義上的孤立卻已成事實。此非文化戰爭,亦非通常所謂「文明衝突」一詞所能打發,更非迄今一時間數十個國家對中國實施旅行禁限,以及世界範圍的厭華、拒華與貶華氛圍之悄悄潮漲這麼簡單。——在此可得提示者,隱蔽的「黃禍」意識勢必順勢冒頭,而買單承受歧視與隔離之痛的只會是我華族同胞,而非權貴——毋寧,關乎對於歷經磨難方始凝練而成的現代世界普世價值的順逆從違,而牽扯到置身列國體系的條約秩序之中,吾國吾族如何生存的生命意志及其國族哲學,其取捨,其從違。在此,順昌逆亡,則所謂孤立者,全球現代政治文明版圖上之形單影隻、孤家寡人也。扭轉這一局面,重建負責任大國形象,擔負起應擔之責,而首先自良善內政起始,必然且只能皈依人類普世文明大道,特別是要坐實「主權在民」這一立國之本。在此,內政,還是內政,一種「立憲民主,人民共和」的良善政體及其有效治理,才是擺脫孤立、自立於世界體系的大經大法,而為國族生存與昌盛之康莊大道也。那時節,順時應勢,中國加入G7 而成G8,亦且並非不可想象者也。

8. A New Era in Which to Seek Freedom from Fear

The People are no longer fearful. These are the common people—men and women who struggle to make a living, a populace that has put up with so much trepidation, a vast population that has only with the most extraordinary difficulty freed itself from the various myths about Power—they are a people who will not forever be willing to hand over submissively the scant freedoms they enjoy to a tyrannical system, or their right to work for a better life. Why indeed should they submit to an prideful polity that arrogates unto itself the exclusive right to apportion life and death, and survival itself?

Because of this Great Virus, the People are enraged; they’ve had enough. They have witnessed how the facts about the viral outbreak were hidden from them and how the health and safety of the common people was ignored by an unfeeling bureaucracy. Long before now, they have repeatedly paid a heavy price — the constant levies imposed on them to support the grandiose celebrations and bloated self-congratulation which the party-state uses to advertise prosperity and peace. All the while the people are treated as straw dogs [that is, sacrificial victims to be dispensed with at will]. They witness the ever-increasing death toll [caused by the virus], yet they are being shut down on WeChat and forced into silence while the power-holders extol their own heroism and shamelessly heap plaudits on themselves. Mass sentiment can be summed up in that line [made famous in Bei Dao’s 1976 poem]: I—DO—NOT—BELIEVE! And they won’t put up with it any more.

Well may they say that the human heart is ineffable and inexplicable; it has no practical use. Experience would seem to have proven this fact repeatedly and we cannot ignore the grim truth.. After all, what about Big Cock Li [Li Peng, whose personal name, Peng, is also a term for a mythical huge bird], the man [who was directly responsible for the Beijing Massacre of 1989 and the nationwide repression that followed in its wake]? Millions bayed for his blood, but he peacefully lived out his allotted time [dying at the age of ninety-one in July 2019] even though the masses strained to spit on him in disgusted outrage. Do we not lament the fact that Heaven repeatedly fails to deliver justice? Even though, if truth be told, Heaven too must suffer along with all of us. If we are to believe that it is the heart—our sense of human decency—is what makes us what we are, rather than the bestial organs of wolves and dogs, then it is the heart too that responds most meaningfully to the vicissitudes of life—be they joys or sorrows, disaster or good fortune, fairness as well as to profit, loves and hates. It is but human to be conflicted by wants and needs, to be prone to suffer the agonies of separation and harbor the hope for happiness. It is by means of that heart that a way forward may be forged, through thickets of pain as well as despite the rotten realities of our world.

When humanity itself is tested even up to the very point of extinction, know that this may presage the true “End of His Days.” As for those addle-brained morons and all of those smarmy gadabouts who think nothing bad can ever happen to them, they are an undifferentiated mob: they play no positive role in history, nor indeed does the course of unfolding events change because of their existence, or anything they do.

第八,人民已不再恐懼。而說一千道一萬,就在於生計多艱、歷經憂患的億萬民眾,多少年里被折騰得一佛升天二佛出世的「我們人民」,早已不再相信權力的神話,更不會將好不容易獲得的那一絲絲市民自由與三餐溫飽的底線生計,俯首帖耳地交還給僭主政制,任憑他們生殺予奪。毋寧,尤其是經此大疫,人民怒了,不乾了。他們目睹了欺瞞疫情不顧生民安危的刻薄寡恩,他們身受著為了歌舞昇平而視民眾為芻狗的深重代價,他們更親歷了無數生命在分分鐘倒下,卻還在封號鉗口、開發感動、歌功頌德的無恥荒唐。一句話,「我不相信」,老子不乾了。若說人心看不見摸不著,最最無用,似乎經驗世界早已對此佐證再三,也不無道理。這不,萬民皆曰可殺,他卻坐享天年,如那個人人唾罵之李大鳥者,令人感慨天不長眼,天道不公,可實際上,天是苦難本身,與我們一同受罪。但是,假如說人之為人,就在於人人胸腔里跳動著一顆人心,而非狼心狗肺,其因生老病死而悲欣交集,其因禍福義利而恨愛交加,其因落花而落淚、流水而傷懷,則人心所向,披荊斬棘,摧枯拉朽矣!人心喪盡之際,便是末日到來之時!至於腦殘與歲月靜好婊們,一群烏合之眾,歷史從來不是他們抒寫的,更不因他們而改變奔流的航道,同樣證之於史,不予欺也。

9. A New Era in Which the Clock Is Ticking

The deplorable reality is evident and the countdown has started—the time to establish a meaningful constitutional order is upon us. It should be recognized that the March 2018 revision of China’s Constitution [which allowed for Xi Jiping to stay in power beyond the limited term in office previously stipulated by law] opened the door to all manner of evil. It has legislated that a totalitarian specter may once more cast a long shadow over us. However, at that very moment, things were taking an unexpected turn; just as that stampede into the past began, systemic decay became increasingly evident. Putting aside the issue of disgruntled popular sentiment, in the above we have already noted the bungled policies related both to Hong Kong and to Taiwan, as well as the disorderly fashion in which the Sino-American relationship has been unfolding. Added to all of that is an overall economic decline that eludes simple resolution as well as the real-time international isolation that China has been experiencing [due to its increasingly aggressive foreign posture]. All of these things are symptomatic of policy failure, yet further proof that “Strong Man Politics”—a phenomenon that flies in the face of modern political life—produces results that are at glaring variance with the avowed aim of their author [that is, Xi Jinping].

Given this suffocating situation, there is a widespread anxiety that we are caught in a stalemate. People are bedeviled by it and strain to think of ways to break through the logjam and excite new possibilities. Of course, there is a fervent hope among many that certain internal dynamics [within the Communist Party] may lead to a way forward; perhaps, they think, something welling up from below that may influence those above positively. Just as such a pipe dream seemed to be capturing people’s imaginations, developments in Hong Kong and Taiwan showed instead how the periphery can suddenly throw the centre off kilter. Events in those two places have been so dramatic that, in fact, they may even offer a ray of hope. For it is perhaps, only perhaps, that with such a path forward—one in which the periphery gradually influences the centre and makes imaginable some kind of peaceful transition, that a particular Chinese Way out of our present political conundrum may be found. Perhaps too the “besieged city” [of Wuhan], beset as it is by crisis, may also prove to be a Jerusalem—a place of hope and peace; an old city proffering new hope.

To put it another way, a breakthrough originating from the periphery may augur once more [as it did in the 1890s, the 1910s, the 1940s and again in the 1980s] a moment that favors a push towards meaningful constitutional and legal rule in China. We may well be at just such a juncture; even as the faint light of a new dawn is discerned on the horizon, we nonetheless remain in the gloaming—we may no longer be lost in the pitch dark of night, yet the roseate promise of a new day still eludes us. Throughout, that bastion of power holds itself together tightly, its crumbling edifice reluctant as ever to acquiesce to the popular will. But, look there, the draw bridge that leads a way out [that is, the promise offered by events in Hong Kong and Taiwan] has been lowered, just so far. Is this not a time spoken of by prophets—even though many will fail and fall before the dawn light ushers in a new day?

第九,敗象已現,倒計時開始,立憲時刻將至。戊戌修憲,開啓邪惡之門,集權登頂之際,恰恰是情勢反轉之時。自此一路狂奔倒退,終至敗象連連。撇開人心已喪不論,則前文敘及之港台應對失策與中美關係失序,以及經濟下滑之不可遏止、全球孤立,表明治理失敗,違忤現代政治常識的強人政治事與願違。大家面對悶局而恐懼其已成僵局,苦思焦慮其開局與再佈局,期期於內部生變式與自下而上式之破局猶如水中撈月之時,港台形勢發展實已自邊緣捅破鐵桶,而開闢出一線生機。此種自邊緣破局、而漸進於中心的和平過渡之道,或許,將成為中國式大轉型的收束進路。此時,吾友所說之「難城」,或為華夏舊邦新命之耶路撒冷。換言之,邊緣突破意味著現代中國的立憲時刻再度即將降臨。當此關口,天欲曉,將明未明,強權抱殘守缺,不肯服膺民意,則崇高之門既已打開,可得預言者,必有大量身影倒斃於黎明前矣。

***

Conclusion: Rage, rage against the dying of the light

I present these Nine Points for the consideration of my fellow countrymen and women. Everything I say is obvious and no more than common sense. Nonetheless, allow me to reiterate my key point: when our nation has yet to enter a normal state of rule; when our people and our civilization are yet to transition into a truly modern era, we must continue forward with fortitude and hope; we must strive to bring about constitutional democracy and realize a real People’s Republic. We have been part of this long-breaking wave of modernity for over one and a half centuries [since the fledgling reform movement of the 1860s in the Qing dynasty]. It is herein that we play a role. That’s right, we, We the People, for [as I have previously said] how can we let ourselves continue to “survive no better than swine; fawn upon the power-holders like curs; and live in vile filth like maggots”?!

以上九點,呈諸國民,均為常識。而一再申說,就在於國家治理未入常態政治軌道,國族政治文明有待現代轉型,而於積善前行中,期期以「立憲民主,人民共和」收束這波已然延續一個半世紀的文明大轉型。正是在此,我們,「我們人民」,豈能「豬一般的苟且,狗一樣的奴媚,蛆蟲似的卑污」?!

As I write these words I am forced to reflect on my own situation, one which also dramatically changed in 2018 [when the author published his famous anti-Xi Jeremiad]. Having raised my voice then I was punished for “speech crimes.” Thereafter, [in March 2019] I was suspended from my job as a university lecturer and cashiered as a professor, reduced to a minor academic rank. I was also placed under investigation by my employer, Tsinghua University and my freedoms have been curtailed ever since. Writing as I do herein, I can all too easily predict that I will be subjected to new punishments; indeed, this may well even be the last thing I write. But that is not up to me.

行文至此,回瞰身後,戊戌以來,在下因言獲罪,降級停職,留校察看,行止困限。此番作文,預感必有新罰降身,抑或竟為筆者此生最後一文,亦未可知。

Confronted by this Great Virus, as we all are, to me it seems as though a vast chasm has opened up in front of us and I feel compelled to speak out yet again. There is no refuge from this viral reality and I cannot remain silent. To act in any other way would be to betray my nature. In Western philosophy, they call it “righteous indignation;” it is a kind of fury that results from repeated abrasion. Our own thinkers speak of it as “humanity combined with a sense of justice.” It is [what Mencius] called “the true way of the human heart” and, thus agitated, I—a bookish scholar who dares to think of himself as an “intellectual”—am prepared to pay for it with my life. [Here the author is referring to the famous Confucian text Mencius where it says: “Benevolence is the heart of man, and rightness his road. Sad it is indeed when a man gives up the right road instead of following it and allows his heart to stray without enough sense to go after it.” — trans. D.C. Lau, Mencius, Book VI, Part A: 11.]

但大疫當前,前有溝壑,則言責在身,不可推諉,無所逃遁。否則,不如殺豬賣肉。是的,義憤,如西哲所言,正是義憤,惟義與憤所在,惟吾土先賢揭櫫之仁與義這一 「人心人路」之激蕩,令書齋學者成為知識分子,直至把性命搭進去。

Ultimately, it is about Freedom—that Transcendent Quality; well-spring and fulcrum of conscious action; that secular value that is the most divine aspiration of humankind; that innate sensibility that truly makes us human; that ineffable “quiddity” that we Chinese share with all others. The spirit of the world, that spirit incarnate on earth, makes possible a glorious unfolding of Freedom itself. This is why, friends—my countless compatriots—though a sea of flames confronts us, can we let ourselves be held back by fear?

畢竟,自由,一種超驗存在和行動指歸,一種最具神性的世界現象,是人之為人的稟賦,華夏兒女不能例外。而世界精神,那個地上的神,不是別的,就是自由理念的絢爛展開。如此,朋友,我的億萬同胞,縱然火湖在前,何所懼哉!

Oh, Vast Land beneath our feet, it is You that I now address:

You inspire the most profound feelings, yet you can be cruel in your dispensation. Despite the bounty of your promise all too often you assail us with ceaseless troubles. Bit by bit you gnaw away at our patience, inch by inch you chip away at our dignity. Do you deserve all of the praise we direct at you or are you worthy only of our curses? There is one thing that I do know, and it is a hard-won truth: at the mere mention of you my eyes fill with tears and my heart gasps. So it is that I say unto You, in the words of the poet [Dylan Thomas]:

I will not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

腳下的這片大地啊,你深情而寡恩,少福卻多難。你一點點耗盡我們的耐心,你一寸寸斫喪我們的尊嚴。我不知道該詛咒你,還是必須禮贊你,但我知道,我分明痛切地知道,一提起你,我就止不住淚溢雙眼,心揪得痛。是啊,是啊,如詩人所詠,「我不要溫和地走進那個良夜,老年應當在日暮時燃燒咆哮;怒斥,怒斥那光明的消逝。」

Yet people like me—feeble scholars—are useless; we can do nothing more than in our lamentation take up our pens and by writing issue calls for decency and advance pleas for Justice. Faced with the crisis of the coronavirus, confronting this disordered world, I join my compatriots—the 1.4 billion men and women, brothers and sisters of China, the countless multitudes who have no way of fleeing this land—and I call on them: rage against this injustice; let your lives burn with a flame of decency; break through the stultifying darkness and welcome the dawn.

Let us now strive together with our hearts and minds, also with our very lives. Let us embrace the warmth of a sun that proffers yet freedom for this vast land of ours!

因而,書生無用,一聲長嘆,只能執筆為劍,討公道,求正義。置此大疫,睹此亂象,願我同胞,十四萬萬兄弟姐妹,我們這些永遠無法逃離這片大地的億萬生民,人人向不義咆哮,個個為正義將生命怒燃,刺破夜瘴迎接黎明,齊齊用力、用心、用命,擁抱那終將降臨這片大地的自由的太陽!

Drafted on the Fourth Day of the First Lunar Month

Of the Gengzi Year of the Rat [28 January 2020]

Revised on the Ninth Day of the First Month [2 February]

As a snow storm suddenly assailed Beijing

庚子正月初四初稿,

初九定稿,

窗外突降大雪

***

***