Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium

Chapter XXXII, Part 1

畫地為牢

The gestation of Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium, a series in China Heritage devoted to the dolorous rule of the man whom I dubbed the ‘Chairman of Everything’ in 2013, started with the release in November 2021 of ‘Resolution on the Major Achievements and Historical Experience of the Party over the Past Century’, the third ‘history resolution’ published by the Chinese Communist Party since it was founded in 1921.

In June 1981, the Party had adopted a ‘Resolution on Certain Questions in the History of Our Party since the Founding of the People’s Republic of China’ in which Mao Zedong, whose personality, thought and politics had dominated the Chinese landscape for over thirty years, was reduced to a more modest, and manageable, size. Forty years later, the November 2021 resolution so inflated and canonised Xi Jinping, his thought and politics that they now occlude all other historical, ideological and cultural possibilities both for China today and the foreseeable future.

Given Xi’s ever-expanding hubristic rule and a personality cult that was, as I had frequently observed was ‘more cult than personality’, I had long expected the Party to release a ‘third history resolution’. The document consisted of one third confabulated history and two thirds immodest Xi Jinping boosterism. Whereas the 1981 resolution had brought a juddering end to a de-Maoification process begun before the Great Helmsman’s corpse had even been pumped full of formaldehyde, the 2021 decision inflated Xi Jinping’s reputation to cartoonish dimensions.

Initially, I thought readers of China Heritage might benefit from a fully annotated translation of the section of the 2021 document devoted to the party-state’s ‘cultural enterprise’ 文化建设. The gnomic style of the text was densely packed with New China Newspeak phrases, slogans and shorthand expressions, all of which required background notes and explications. Important though the task seemed to be, after writing a few thousand words I found myself overcome by boredom. I had been writing about Chinese culture — both official and unofficial — for over four decades and although the latest twists and turns in the story are significant and worth serious analysis, they are ultimately rather dull. So, instead of pursuing an annotated transition, I decided to revisit some of the key topics that I had addressed over the years in the form of an ongoing series of essays, one that I called ‘Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium’.

I follow a definition of ’empire’ referring to a power that will continue to expand as far as it can go, or until it is stopped (for more on this, see the series Translatio imperii sinici, also in China Heritage). The word ‘tedium’ in the title refers to a sense of ennui and exasperated foreboding, one that I share with many old friends both in- and outside China. How tedious, for example, to see old policies being revived and imposed even though their authors know full well that they hadn’t worked the first, second or even third time around. Now, yet again, they were being pursued with the ritualistic flourishes and clichéd diction of the past. Tragedy was not being repeated as farce, rather tragedy was being revisited as tragedy. Force majeure was the muscle memory of the party-state.

Before launching Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium in early 2022, I expressed my exasperation in History as Boredom — Another Plenum, Another Resolution, Beijing, 11 November 2021, China Heritage, 14 November 2021, which featured an essay by Václav Havel that remains essential reading for anyone who is interested in Xi Jinping’s China and its future.

***

It is nearly two years since the party released its Xi Jinping-centric third history resolution and one year since the Twentieth Congress of the Chinese Communist Party at which Xi claimed what amounts to ‘terminal tenure’. The Communists have marked these glum anniversaries by announcing the epochal significance of ‘Xi Jinping Thought on Culture’ 習近平文化思想, a new formulation for familiar old tropes that has been celebrated with considerable fanfare. Here, we offer an overview of the latest advance in Xi Thought with ‘Xi Jinping’s Cathedral of Pretense’ by David Bandurski of the China Media Project. We preface David’s incisive analysis with an essay written by George Urban in 1970, his introduction to a ‘compendium of devotional literature’ related to the Mao cult that he compiled in 1970. Urban’s old thoughts about Mao are refreshingly relevant to students of the new thoughts of Xi Jinping on culture. More to the point, given the adulation of Xi’s universal genius and ‘the miracles of China’ 中國奇蹟, speculation about his own wonder-working is unavoidable. For example, as in Mao’s day, will the mere recitation of quotations from His Works have a supernatural effect? Surely his devotees should demand nothing less.

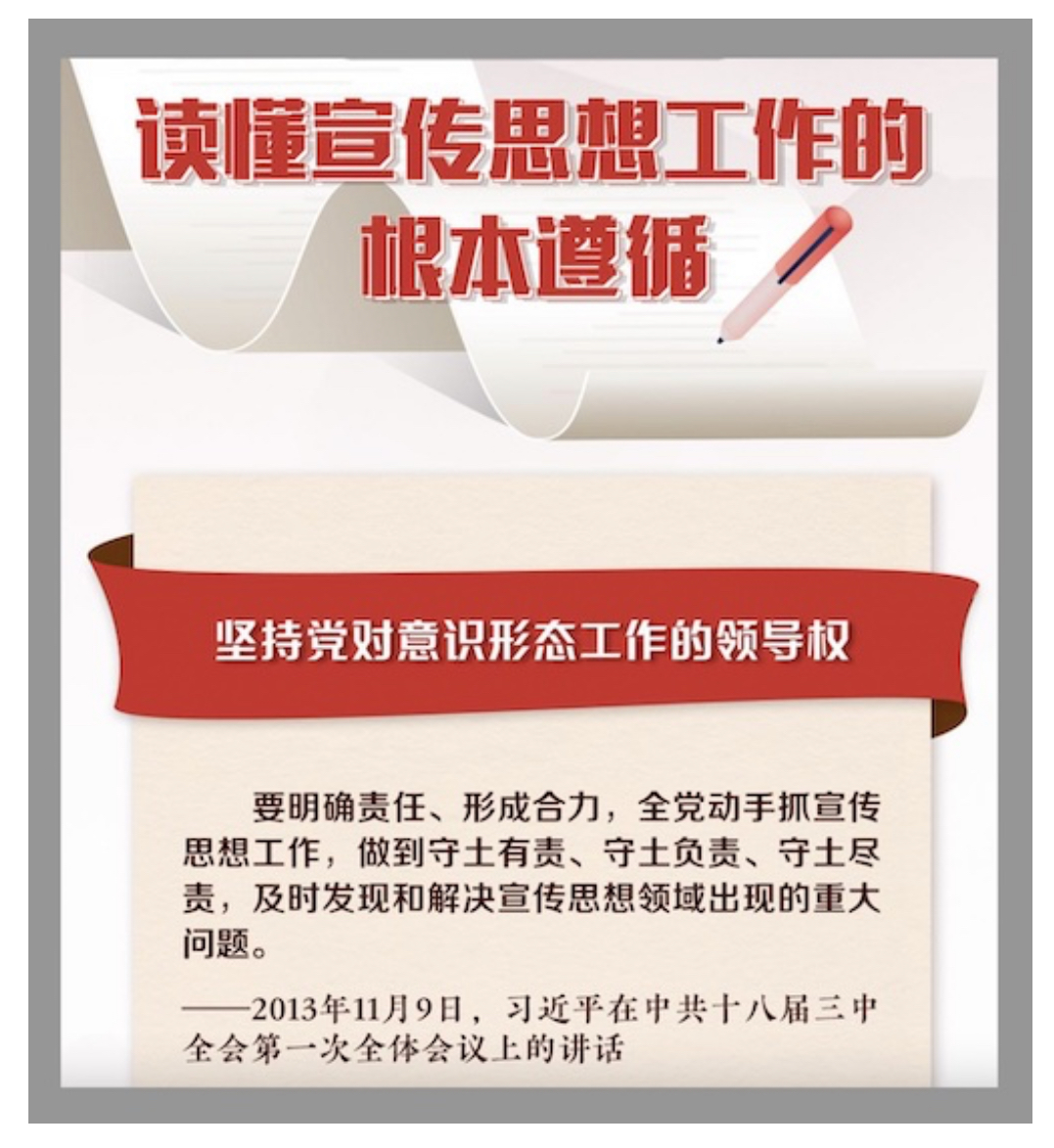

What, then, is Xi Thought on Culture? Well, it is one of ‘Six Great Thoughts’ 六大思想 authored by Xi Jinping and the eight-point shorthand version produced for mass consumption sums it up as: Party domination, ideological control, socialist values, the management of traditional culture, effective propaganda, investment in and support for approved cultural products and appropriate international exchanges. The propagandists sum up the effective ways to pursue the leader’s instructions in all of these eras in an eight-character expression — 明體達用、體用貫通. That is, to awaken to the multidimensional essence of Xi Jinping Thought so as to be able to effectively apply it in all situations and under all conditions. To do so successfully means that theory and practice will exist in perfect harmony. In other words, the monomaniacal nature of Xi Thought licenses it to expand and fill all possible policy spaces.

This use of 體用 tǐ yòng in the shorthand formulation above obviously recalls both the ‘essence / application’ policy of the Tongzhi Restoration in the 1860s — 中學為體、西學為用 (to maintain a Chinese soul while pursuing Western knowhow) — as well as Lin Biao’s exhortation regarding Mao Thought in the 1960s to ‘study and apply Mao Thought in all things’ 活學活用 (or 要帶著問題學,活學活用,學用結合,急用先學,立竿見影,在‘用’字上狠下功夫).

[Note: Both the 體用 tǐ yòng framework devised by Zhang Zhidong 張之洞 in the Qing and Lin Biao’s ideological utilitarianism under Mao hark back to the applied Confucianism of Wang Yangming (王陽明, 1472-1529).]

In practical terms, Xi’s Cultural Thought is hegemonic: the Party and the Party alone has the exclusive right to determine the nature, definition and significance of all forms of legitimate Chinese cultural, artistic and social expression. It claims the exclusive right to delineate the meaning of the past, the value of the present and the potential contributions of the present to ‘China’ — a quasi-mystical, transhistorical, ethnic-nationalist body that exists both in and beyond space-time itself. Xi Thought on Culture is the alpha and omega of Chineseness 中華性.

Or, as David Bandurski asks:

‘What does all of this nonsense mean? … Xi Jinping’s obsession with culture is about the need to disguise basic questions of power and legitimacy behind the elaborate stonework of political discourse.’

We are also reminded of Lee Yee’s observation about the then newly minted formula of ‘Xi Jinping Thought for the New Epoch of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics’ in 2017:

To put an individual’s name ahead of a pile of dogmas reminds me of something that [the former Chinese Party General Secretary] Hu Yaobang said [at the end of the Cultural Revolution as the personality cult of Mao Zedong was being dismantled]:

As soon as you create a personality cult, there is no room for democracy, no place to seek truth from facts, no hope for the liberation of thinking; what is inevitable is the restoration of feudalism. There is nothing more pernicious than this.

For an alternative to the official party-state view, see You Should Look Back, the introduction to Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium, our work on New Sinology and our new series, The Tower of Reading.

***

We are grateful to David Bandurski for permission to reprint his essay on Xi CultThink. The typographical style of the original has been retained.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

13 October 2023

Anniversary of the Sitong Bridge Protest

彭立發四通橋事件一週年紀念日

***

Further Reading:

- 五嶽散人,「習近平文化思想」新鮮出爐,那麼咱聖上到底有文化麼:有,而且追根溯源能有幾百年的文化底蘊,油管,2023年10月14日

- Manoj Kewalramini, Interpreting Xi’s Thought on Culture, Tracking People’s Daily, 13 October 2023

- 當馬克思遇見孔夫子,湖南衛視、芒果TV,2023年10月9日

- Geremie R. Barmé, On Understanding Xi Jinping, The New York Times, 5 November 2015

- Lee Yee 李怡, What’s New About Such Thinking?, 5 November 2017

- Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Living Lies in China Today, 8 May 2019

- Isaiah Berlin, et al, Xi Jinping’s China & Stalin’s Artificial Dialectic, 10 June 2021

- Geremie R. Barmé, Red Allure & The Crimson Blindfold, 13 July 2021

- Geremie R. Barmé, Prelude to a Restoration: Xi Jinping, Deng Xiaoping, Chen Yun & the Spectre of Mao Zedong, 20 September 2021

- Tedium Continued — Mao more than ever, 26 December 2022

From Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium:

- The Curse of Great Leaders — the Xi Jinping decade and beyond, 20 July 2022

- A Hosanna for Chairman Mao & Canticles for Party General Secretary Xi, 22 October 2022

- Xi the Exterminator & the Perfection of Covid Wisdom, 1 September 2022

- When Zig Turns Into Zag the Joke is on Everyone, 12 December 2022

Homo Xinensis:

- The Editor and Lee Yee 李怡, Deathwatch for a Chairman, 17 July 2018

- Ruling The Rivers & Mountains, 8 August 2018

- The Party Empire, 17 August 2018

- Homo Xinensis, 31 August 2018

- Geremie R. Barmé, A People’s Banana Republic, China Heritage, 5 September 2018, also published as Peak Xi Jinping?, ChinaFile, 4 September 2018

- Homo Xinensis Ascendant, 16 September 2018

- Homo Xinensis Militant, 1 October 2018

From Viral Alarm:

- The Heart of The One Grows Ever More Arrogant and Proud, 10 March 2020

- Xu Zhiyong 許志永, Dear Chairman Xi, It’s Time for You to Go, ChinaFile, 26 February 2020

- Guo Yuhua 郭於華, The Poison in China’s System, 6 March 2020

- Xu Zhangrun 許章潤, Viral Alarm — When Fury Overcomes Fear, 24 February 2020

***

The Miracles of Chairman Mao

George Urban

[Editor’s Note: George Robert Urban (born Gyorgy Robert Ungar, 1921-1997) was best known as a broadcaster for Radio Free Europe and as an editor of Encounter magazine.]

Maoism is one of the wonders of ideological crossbreeding. Pure strains in ideology are, of course, always hard to come by; Marx and Engels were bourgeois Rhinelanders who settled in England. Their economic theories derived from, and were designed to cure, the ills of West European society then on its way to industrialization. Yet, in the hands of Lenin, they were first bent to the needs of an under-developed, agrarian Russia, and later further distorted to fit the Byzantine designs of Stalin. The results had a great deal to do with the autocracy which Leninism had replaced in Russia, but very little with what Marx and Engels had written about. Yet Lenin’s and Stalin’s sectarianism[1] strikes one as well within the “normal” tradition of European despotisms set against Mao Tse-tung’s thought and the application of his philosophy in the cultural revolution.

[1]’Revisionism’ would apply with almost equal justification, for in the unsettled heritage of Marx, heresies and orthodoxies are freely interchangeable, depending on who speaks from the pulpit.

Much ink and acrimony will be spent in deciphering the intellectual origins of Maoism: Marx and Lenin, Confucius and Mencius, silent assumptions about China’s cultural superiority, Mao’s nationalism and the xenophobia of his generation have all played their part. Whatever the mixture, the transplantation of a body of opinions from one socio-economic environment to another has always been a delicate operation. The history of religion abounds in examples. In the Maoist variety of communism the Marxist element had, inevitably, the roughest passage. Stalinism did not travel much better. Yet, the journey from Moscow to Peking has, in a sense, tempered the crudities of Stalin’s legacy. Maoism, though equally thought-killing and intolerant, has shown itself to be still fresh with the excitement of revolution and hence closer to the concerns of hungry and under-housed men and women than Moscow’s doctrine. The Soviet model, with its insipid conservatism and a proletariat well set on its way to embourgeoisement, has nothing to say to the under developed world to which China belongs. China has and her relevance may not be entirely confined to the poorer nations.

What is her message? When the verbiage is peeled off and the appalling cruelties of the 1951-52 “three-anti” and “five-anti” campaigns … are placed in historic perspective (and putting them in perspective is not to excuse them), we are left with a handful of ethical imperatives. Maoism is a serious call to a socially responsible moral conduct which has a great deal in common with Christian rectitude, especially in its Protestant and Victorian embodiment. It stresses the social virtues of temperance, frugality, humility, sacrifice and hard work. It insists on man’s ability to overcome nature, including his own, by a sheer assertion of will. It exalts the “socialist” organization (though it denies the hierarchy) of the family which serves as a microcosm of the state. Such values are in short supply in the West too. For those enjoying a sense of guilt about the surfeit and meretriciousness of our civilization, Maoism offers a beguiling guide for action.

Mao holds that the mortification of self is the first stage of revolution. This has already produced an effervescence in the student generation in Western Europe and America, even if in forms so distorted that they can hardly be said to be more than tangentially related to Mao’s message.[2] It contains a yet more important factor. Although Maoism has scrupulously distanced itself from anarchism — and had very sound reasons for so doing in the light of the excesses of the cultural revolution — it advocates a continuously recurring social regeneration and places it at the heart of the cultural revolution. This rejuvenation of the sinews of society, Mao’s war on bureaucracies and establishments of all kinds,[3] carry an emotional charge that makes them seem at least superficially relevant to the problems of sophisticated, industrialized societies. That Mao’s message comes to us from an étatism which is not demonstrably less oppressive, and is certainly more de-personalizing, than the one it has ousted, is not appreciated in the West, or else it is discounted as the Party’s over-reaction to Mao’s iconoclasm.

[2] “Make love not war” and “political power grows out of a barrel of a gun” make strange bedfellows, though Eldridge Cleaver’s claim that “revolutionary power grows out of the lips of a pussy” offers a bizarre explanation of their juxtaposition.

[3] This, in the language of Chinese (and Far Eastern) history is simply breaking the “dynastic cycle” in which leading positions in the state hierarchy were hereditary, not elective. The cultural revolution may thus be seen as an antidote to the personal, psychological degeneration of a leadership which, having conquered power, has opted for a period of rest and consolidation.

But Mao’s influence is paradoxical. If his stress on Confucian and, some would say, Christian moral values engages our sympathy, the way in which these values are applied and propagated evokes our repugnance. The saintly life is preached from an ant-heap. It invites emulation by social insects, not men. The ideal type of Maoist rectification is the fully conditioned moron who, by some freak, is both unquestioningly obedient to the Maoist ethic and capable of displaying superb feats of initiative. Can such clearly inhuman means serve ostensibly humane ends?

In the context of Chinese civilization the paradox is not as profound as it would appear to Western eyes. Filial piety (xiao 孝), respect for the rules of propriety (Li 禮), the emulation of human models, a high sense of conformity in speech, dress and ceremony, a traditional trust in the malleability of the human material (“The people are born good, and are changed by external things”,[4] the Shujing 書經, Book XXI, third century B.C.), all prepared the ground for the acceptance of Maoism as China’s substitute religion in an age of transition.

[4] According to a Western Han legend, often regarded as one of the foundation stones of Chinese education, Mencius’s mother changed her domicile three times before her son began to show moral and intellectual improvement.

In a sense the cultural revolution itself is a typically Chinese rather than a Marxist phenomenon. No other communist country has had one;[5] but then communist countries are seldom run by poets. There is more than superficial connection between Chiang-ching’s (Mme. Mao’s) reform of the Peking opera and the dictum in Yueji 樂記 (China’s ancient Record of Music): “We must discriminate sounds in order to know the airs; and airs in order to know the music; and the music in order to know the character of the government”.[6] One can trace, in the imagery and usages of Maoism, almost every detail back to the Chinese classics. For instance, the Maoists’ predilection for casting their slogans in numbered categories (the “two-lines”, the “three-capitulations and one abolition”, the “four-olds”, the “five-category elements”, and so on, see Glossary) derives directly from the sacred books of China. Thus in the Shujing the “Great Plan” falls into “nine divisions”; we read of “eight objects of government”, “the five punishments”, “the five dividers of time”, “the five personal matters”, etc.

[5] China had. In 1898 the Emperor Guangxu undertook to modernize China by sweeping cultural reforms. However, he was deposed by the Manchu Empress Dowager, Cixi, his edicts were rescinded and he remained a prisoner for the rest of his life.

[6] Zhdanov had no such tradition to follow in Russian culture. His musical purism was based, much more clearly than the Chinese variety, on police power.

None of this is to pass moral judgement on the Chinese people’s fitness to be treated as political adults. But it would be surely foolish to deny that while to a Frenchman, with 1789, Blanqui, Proudhon and the Paris Commune in his intellectual heritage, “rectification”, would seem an insufferable insult to his intelligence, a modern Chinese, heir as he is to centuries of conformism, emperor cult,[7] and a hierarchic view of society, would react to demands for cheng-feng [整風] (mental remoulding) with greater tolerance and perhaps a sense of amusement and irony. Whatever its origins, in Mao’s eyes “re-moulding” is not an inhumane means, and it is even less inhumane by the yardstick of the Stalinist purges. It obviates the need for physical liquidation, diverting the Party’s attention from the body to the mind of the object of rectification.

[7] Paying homage to “deified” leaders has been widely practiced even in modern China, The Nanking government set in train an official cult of Sun Yat-sen by ordering all government offices and schools to hold memorial sessions of Sun each Monday. These consisted of three bows before Dr. Sun’s portrait, readings from Sun’s will and the observance of three minutes silence. Later a cult of Chiang Kai-shek was added. Whenever the names of Sun and Chiang appeared in print, they were elevated in the same way a were the names and canonized titles of emperors.

Given China’s restricting cultural perimeters which have always set narrow limits to personal and intellectual freedom (well reflected in the cutting down of Chairman Mao’s little flowers after the “contending and blooming” of 1956 and 1957),[8] Mao’s particular method of conditioning the people may not, in itself, hamper the growth of industrialization and modernization but may, on the contrary, enhance it. (Whether industrialization and modernization are humane ends is another question). To us this may seem like an inordinate price to pay for a modicum of organization and comfort, but to a hungry country such as India, which is rapidly sinking into anarchy and is already ungovernable, the Maoist model may not be so repulsive.

[8] Nevertheless the Chinese intellectuals could draw on a long line of historic precedents for believing that their criticisms were being honestly sought and that they would be acted upon. A time-honoured tradition of China ascribes to the intellectuals a duty to criticize the ruler. Confucius says that that it is a minister’s office to oppose his ruler to his face (Analects, 14.23). The “right of remonstrance”, later institutionalized in the “Censorate”, elevates, in fact, the scholar to the status of political critic.

It is to the ordinary, mostly illiterate and superstitious masses that the devotional literature which has built up around Mao Tse-tung is principally addressed. Mao is sophisticated enough to realize that although some learned treatise of his on the nature of contradiction or aesthetics will be willingly mouthed by the Chinese peasant if it is foisted upon him by authority, the charisma of Mao and the doctrine he represents will have no personal impact unless they are depicted in the kind of language Chinese peasants understand.

This requires adopting the mental attitudes and vocabulary of the parable, the proverb, the fairy story and the cautionary tale as they have come down in Chinese folklore and literature. Chairman Mao’s “miracles”, of which this book offers a modest selection, are all geared to some essential point in the Chinese Party’s programme. Some support the extension of medical services to the rural areas, others demonstrate the feasibility of running hospitals and clinics without sophisticated personnel and medicines of which China is chronically short. But over and above that they evince the universal validity of Mao Tse-tung’s philosophy. The message is simply that Maoism is a cure-all: in hoc signo vinces. The naive homilies, the endless labouring of moral points that are already painfully obvious, the chilling contrast between the good peasant and the wicked landlord, between the socialist masses and the “handful of capitalist roaders”, between God (Mao) and the Devil (Liu) have a classical Chinese and also an Old Testament ring about them. Some of this material that pours forth from the (officially controlled) press and radio has a quality that endears by virtue of its sheer simplicity. Some of it attracts and amuses by its absurdity. But there are also items that assault our sense of natural justice. They assume that the individual has no intrinsic merit and deserves no respect unless he is a worker, a poor, or a lower-middle peasant, with two unpleasant corollaries; firstly, that those who are not members of this class are fair game for those who are and, secondly, that the state has a right to release the unconfessed springs of class-consciousness in those who belong to the chosen class but are insufficiently aware of it. This is the Marxist-Maoist doctrine of Original Virtue: custom, selfishness and remnants of bourgeois thinking may, for a time, suppress its call, but the state is there to help the sinner cleanse himself of these corrupting influences. Through contrition, confession and penance (“struggle, criticism, transformation” in the language of the cultural revolution) the class-deviant is “liberated” and restored to his natural role as an appointed maker of history. These are important elements in Maoism, yet its real significance lies elsewhere.

The voice of Mao Tse-tung is the voice of the church militant speaking with the reforming fanaticism and intolerance of a Savonarola. Mao’s battle is for the soul of the world communist movement, and the restoration of China’s power and self-respect is only the first step on that way. To a young and dedicated communist, especially if he is an African, a Latin American or Asian, Moscow’s voice is unprophetic and heavy with the boredom of establishment. It is the voice of a sated giant whose economic targets are those of the United States and whose social and cultural values are daily growing more akin to those of the United States. Peking inspires because it speaks from poverty and because its avowed aim is (to adapt Macaulay) to make men perfect, not to make imperfect human beings comfortable.

It is true that the cultural revolution is about industrialization, about thought-reform, about a power struggle. But its full importance lies beyond. In the short run, the challenge of Maoism as it emerges from the upheavals of 1966-69 is a challenge to the Eurocentric tradition of the world communist movement and therefore also to the power and influence of the Soviet Union. For the first time in the history of communism the defiance of the Soviet Union has been written into a communist party’s constitution. In the long run, Maoism may furnish the non-white races of the world with a religion to rally the power implicit in their numerical superiority over the white races.

An aura of primitive religion pervades the extracts which follow. The legends being officially propagated cover the gamut of religious appeal from sacrifice and the sanctity of relics to the mystic union with the (still living) godhead. In China today a new hagiography is being seeded, appealing to the irrational in the name of a faith which claims exclusive commerce with a scientific understanding of history.

— GRU

London, June 1970

***

Source:

- George Urban, ed., The Miracles of Chairman Mao: a Compendium of Devotional Literature, 1966-1970, London: Tom Stacey Limited, 1971. The Wade-Giles romanisation of the original has been converted to Hanyu Pinyin.

***

Mind, Heart, Soul: Overthinking Culture

In the annals of modern Chinese political sycophancy, Lin Biao, creator of the ‘Little Red Book’ and architect of the Mao Cult is a paragon and inspiration for latter-day toadies. In 1966, Lin declared that:

‘Comrade Mao Zedong is the greatest Marxist-Leninist of our era. He has inherited, defended and developed Marxism-Leninism with genius, creatively and comprehensively and has brought it to a higher and completely new stage…. Mao Zedong’s thought is the guiding principle for all the work of the Party, the army and the country. … The broad masses … should really master Mao Zedong’s thought; they should all study Chairman Mao’s writings, follow his teachings, act according to his instructions and be his good fighters…. Once Mao Zedong’s thought is grasped by the broad masses, it becomes an inexhaustible source of strength and a spiritual atom bomb of infinite power.’

— Lin Biao, Foreword to The Quotations Of Chairman Mao, 1966

In Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium, Li Hongzhong and Cai Qi are both standout political courtiers. Li is known for what may well be the most fawning expression of devotion to date:

忠誠不絕對就是絕對不忠誠。

If you’re not absolutely loyal, you’re absolutely not loyal.

— from 李鴻忠,忠誠不絕對就是絕對不忠誠 以「無我」示忠, 2016年10月22日

In May 2023, Cai Qi, a member of the Communist Party’s ruling Standing Committee, vied for the title of obsequiousness when he declared that Xi Jinping Thought must ‘take root in people’s minds, hearts and souls’ 入腦入心入魂.

‘In the pursuit of our ideological education plan’, Cai declared, ‘it is essential to organise the coordinated study of the Selected Works of Xi Jinping in such a fashion that Xi Jinping Thought takes root in people’s minds, hearts and souls.’

要深入開展主題教育,把《習近平著作選讀》學習運用工作組織好、安排好,推動習近平新時代中國特色社會主義思想入腦入心入魂。

— Cai Qi 蔡奇, member of the Standing Committee of the Party’s Politburo, 23 May 2023

Then, in October 2023, Li Hongzhong then went one better…

‘After studying Xi Jinping’s Cultural Thought I feel as though I have been born again. All of a sudden I’m possessed of the genius of both Liu Bowen and Zhuge Liang. My mind has achieved a new stage of enlightenment. ‘

Li went on to praise Chairman Xi’s works as being ‘ten-thousand times more profound than the wisdom of Lao Tzu’s Tao Te Ching and able to lead all of humanity to ever greater glories!’

‘Chairman Xi is China’s Amitābha, the Eagle of the Himalayas, the Roaring Dragon of Changbai Moutains!’

中央政治局委員,十四屆全國人大常委會副委員長李鴻忠在學習首次提出的《習近平文化思想》

學習研討會上發言:學習了習近平的文化思想後,猶如醍醐灌頂,瞬間覺得自己如同諸葛亮、劉伯溫附體,腦海裡一下子想通了很多。他稱贊習主席的著作比老子的《道德經》深邃一萬倍,必將指引全世界的人民走向更加輝煌的末來!他說:習主席就是中國的如來佛、珠穆朗瑪峰的雄鷹,長白山的咆哮巨龍!

— attributed to Li Hongzhong 李鴻忠, October 2023

***

Xi Jinping’s Cathedral of Pretense

David Bandurski

13 October 2023

With the addition of a grandiose new buzzword in China for culture and civilization, it may seem that a towering future is on the horizon. We take a hard look at the foundations of “Xi Jinping Thought on Culture.”

With all the talk in recent months in China of “new civilizational splendor” (文明新辉煌) in everything from sports to Marxism, heritage protection to village life, it is impossible not to sit up and take notice of the country’s fulsome messaging on culture. Surely, something must be happening. No? As officials emerged last weekend from the latest Chinese Communist Party work conference, the language mounted further. They unveiled yet another eponymous phrase for the country’s top leader: Xi Jinping Thought on Culture (习近平文化思想).

In the Party’s flagship People’s Daily newspaper, a front-page tribute on Wednesday deemed the phrase a “significant milestone” (里程碑意义), suggesting excitedly that the general secretary had “accurately grasped the trend of mutual ideological and cultural agitation worldwide.” What does all of this nonsense mean? Why is China building the rhetoric over culture and civilization to such dizzying heights?

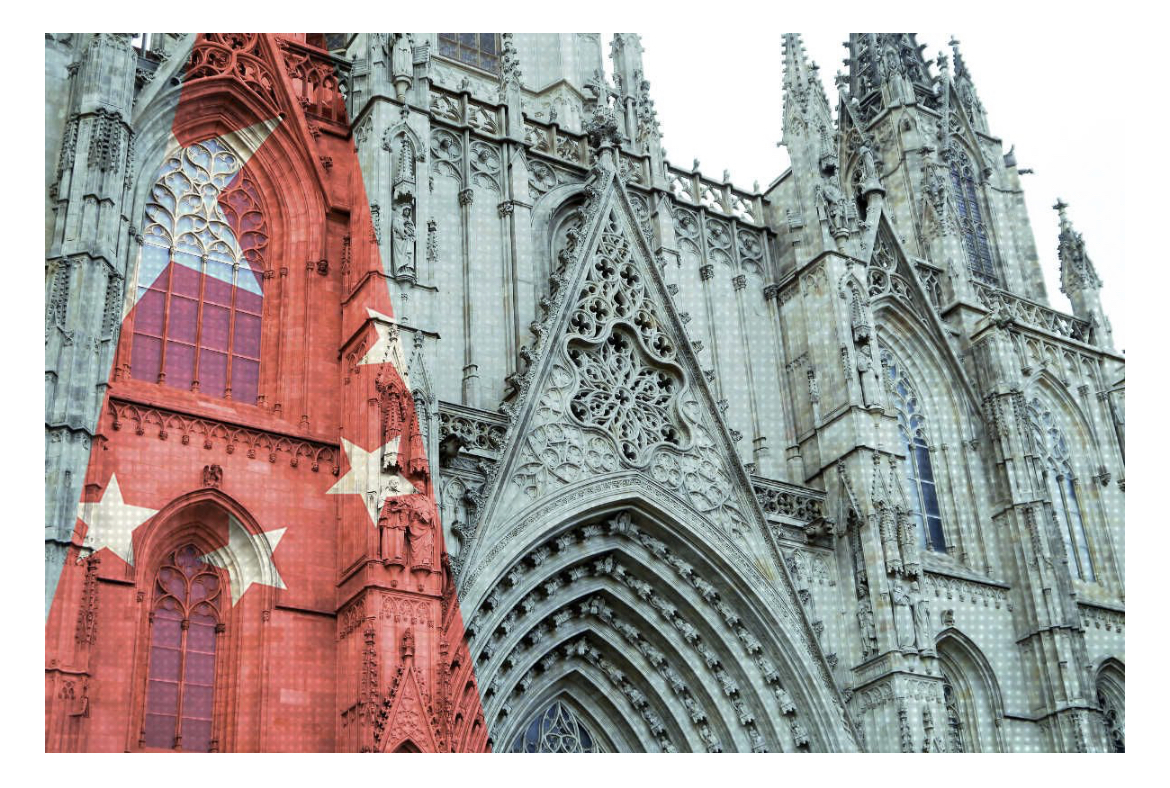

If we avoid becoming distracted by the monumentality of the cathedral of language before us, and gaze past its gothic flourishes, the answer is deceptively simple. Xi Jinping’s obsession with culture is about the need to disguise basic questions of power and legitimacy behind the elaborate stonework of political discourse.

Grab your chisels. Let’s break this down.

The Nine Adheres

According to explications of “Xi Jinping Thought on Culture” provided this week by the People’s Daily and other official media, Xi’s brand-new cultural concept is actually the culmination of a “series of important speeches” he delivered around two previous meetings on propaganda and ideology.

During these meetings, which have traditionally been called National Propaganda and Ideology Work Conferences (the word “culture” was tellingly added for this latest one), Xi outlined the nature of the CCP’s work on several facets of what can be included under the broader umbrella of culture: “work on literature and the arts” (文艺工作); “the Party’s work on news and public opinion” (党的新闻舆论工作); “cybersecurity and informatization work” (网络安全和信息化工作); “philosophy and social science work” (哲学社会科学工作), and “cultural heritage development” (文化传承发展).

These conferences, in other words, laid the foundation for the “significant milestone” the leadership claims to have reached just six days ago.

To better understand the foundations of “Xi Jinping Thought on Culture,” we can unpack the first of these conferences, held in August 2018, during which Xi Jinping laid out what he called the “Nine Adheres” (九个坚持).

Not surprisingly, given that they are important components of the “Xi Jinping Thought on Culture,” the “Nine Adheres” have been dragged out again this week by Party-run media, and even graphically represented. They are drawn from various speeches Xi has made during his time as the Party’s top leader, including during his first meeting on ideology in August 2013.

Read through the “Nine Adheres” and you will be hard-pressed to find anything whatsoever related to culture or civilization outside the guardrails of political power. There is nothing to do with the arts or artists, with cinema or filmmakers, with publishing or writers, with choreography or dancers. There is nothing to do with music or melodies — save for references to the “main melody” (主旋律), a phrase about the imperative of ensuring the CCP’s voice is dominant.

This point, that the CCP’s driving motivation is the control of culture, may seem painfully obvious. But it is crucial, nevertheless, to clearly acknowledge the foundations. The danger, otherwise, is that we read too much into the elaborate discourse of civilization, and imagine China under the CCP is tipping toward a cultural renaissance, or trying to empower one, rather than cynically leveraging culture to legitimize a one-party authoritarian dictatorship under an emerging cult of personality.

In this vein, one cautionary tale comes from former British Prime Minister Tony Blair, who after a visit to China in 2009 in which he was inundated with the latest CCP-speak on “cultural sector reforms” claimed in an op-ed for the Wall Street Journal that the country was in the constructive throes of a “New Cultural Revolution.”

So let’s look at the “Nine Adheres,” which the People’s Daily tells us is foundational to “Xi Jinping Thought on Culture.” I include the full list below, with remarks.

- Adhering to the CCP’s leadership authority over ideological work.

This should be self-explanatory. It is the claim by the CCP under Xi’s leadership to have an exclusive and ultimate say over matters concerning ideology, which encompasses the entire universe of ideas and their expression through media, the internet, the arts, philosophy, the social sciences, and so on.

- Adhering to the fundamental task of the “Two Reinforcements” (两个巩固) in ideological work.

Here, a catchphrase is used to explain a catchphrase, again reminding us that its important to pick apart the edifice of CCP discourse, brick by brick. This refers to “reinforcing the guiding role of Marxism in the ideological sphere” and “reinforcing the common ideological foundation for unity and struggle by the whole Party and the entire people.” The explication by the People’s Daily Online also mentions Xi Jinping’s emphasis on the need for both “a correct political orientation and guidance of public opinion,” the first self-explanatory and the second an explicit reference to the need for CCP control of the media and information to maintain political control.

- Adhering to the use of Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for the New Era to arm the entire Party, and to educate the people.

Here within the cathedral, in the chapel dedicated to “Xi Jinping Thought on Culture,” we see the recurrence of the motif that gives purpose to the entire cathedral — the god-like dominance of Xi Jinping. The CCP’s leadership is established first, followed by the guiding role of Marxism, and then the emphasis on the leadership of Xi and his inspirational contributions to the governance and belief system — at base, a claim to his legitimacy as top Party leader.

- Adhering to the cultivation and fulfillment of socialist core values.

This is, yet again, about obedience to the Party-led value system. For more on “socialist core values” and their rigid interpretation, see “The Battle of Brick Lane.”

- Adhering to cultural confidence as the foundation.

This is where Xi Jinping’s claim to legitimacy, a bare-bones structure of power assertions to buttress his leadership and that of the Party, is filled out with the finer details of traditional Chinese culture. This is not really about culture, however. It is about the populist appeal to the inspirational nature of Chinese culture — populist because it is about affirming China’s rise in the contemporary world against a backdrop of historical exploitation and disrespect (a key part of the CCP narrative). “Chinese civilization” (中华文明) is referenced here, using a May 2022 passage from Xi Jinping, to advance the notion that the CCP has a cultural-political claim on the entire global Chinese population, including the diaspora. “Chinese civilization . . . is the spiritual tie that binds all the Chinese of the world, and a treasure of Chinese cultural innovation.” Civilizational pride is a keystone of Xi’s claim to legitimacy in his third leadership term.

- Adhering to the communication power, leading power, and influence power of news and public opinion.

Now that the list of adheres has established the dominance of the CCP, Marxism, and Xi Jinping, and filled this hard superstructure with frescos of cultural/civilizational glory, it is time to think about how the messages of the Party can be most effectively communicated. It’s not surprising to find language here about the need for “media convergence development” (媒体融合发展), and the remaking of the “mainstream media” (主流媒体), which in the CCP context refers to Party-run media exclusively. That also means CCP control of the message, of course, and we should note that the language of information control dominates. The People’s Daily Online emphasizes quotes from Xi that stress “adhering to the leadership of the CCP [over news and public opinion],” and the “correct political orientation.”

- Adhering to the people-centered orientation of creation.

Now that claims to power and its underlying value orientation have been handled in 1-6, the final third of the “Nine Adheres” can deal with more peripheral matters of importance. Here, the CCP insists upon innovation and creation within the guardrails already established. Essentially, within the bounds of control, culture should consider the needs of the population and the proclivities of the audience. This is about “satisfying the spiritual demands of the people.” For more on how the CCP applies the notion of “the people,” see Ryan Ho Kilpatrick’s recent post. We can also note that this combination of control and audience positioning is not new in the reform era. During the Hu Jintao era, for example, it was conveyed through the idea of the “Three Closenesses” (Find out more in the CMP Dictionary).

- Adhering to a clear and positive online space.

Through the 1980s and the 1990s, before the rise of the internet as the primary means of communication, enforcing the political and cultural guidelines of the CCP was in many ways a far simpler matter — even if, in the midst of broader social and economic change, it was never simple. Since Xi Jinping came to power, the focus has shifted decisively to the internet when it comes to information control, evidenced by the growing dominance of the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC), created through an agency shakeup in 2014. The control of cyberspace is now paramount to the Party. The language from Xi Jinping in the People’s Daily Online explainer for the “Nine Adheres” comes from Xi’s speech at the April 2018 work conference on cybersecurity, in which he said the CCP “must strengthen positive propaganda online, [and] adhere with a clear banner to the correct political direction, [correct] guidance of public opinion, and [correct] values orientation.”

- Adhering to the telling of China’s story well, and the communicating of China’s voice well.

In a new world of mobile digital information, it is no longer sufficient for a ruling political party in an authoritarian system to focus on domestic information and ideological control alone, as the Chinese are potentially exposed to alternative systems and values despite a massive information control infrastructure. Therefore, it is important that the CCP reinforce power and control back home through greater “discourse power” (话语权) on the global stage. So the last of the “Nine Adheres” is fundamentally about soft and sharp powerdevelopment, and what the CCP still calls “external propaganda” (外宣).

While official Party media claim this week that Xi Jinping has “put forward a series of new ideas, new perspectives, and new assertions” that have culminated in the concept of “Xi Jinping Thought on Culture,” the hard stone of the “Nine Adheres” reminds us that the foundational assertions are about CCP power and the necessity of cultural control in defense of that power.

Of course, even if Xi was a culturally accomplished president — a Havel, Disraeli, or Franco — the suggestion that he has grasped a “cultural agitation worldwide” would be preposterous. The point, however, is that “Xi Jinping Thought on Culture” has nothing whatsoever to do with culture, though we will surely hear in the months to come about Xi’s designs for a cultural refulgence.

To understand this latest new catchphrase, just imagine a soaring cathedral of lavish discourse. The monument, which is named “Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for the New Era,” embraces the empty core of CCP power, giving it a seeming solidity. For some time now, there have been five chapels along each side, each a place to worship the god-like achievements of the top leader. There are chapels to foreign policy (习近平外交思想), rule of law (习近平法治思想), the economy (习近平经济思想), environmental policy (习近平生态文明思想), and national defense (习近平强军思想).

Now, in Xi Jinping’s unprecedented third term, the monuments must be all the grander to disguise the hollowness at the core and to expand the space for the necessary rituals of power. A new chapel, the sixth, is erected, giving new symmetry to the structure.

Now unveiled, the chapel of “Xi Jinping Thought on Culture” can be visited, worshipped, and talked about. A grand distraction for China’s grandest leader in generations.

***

Source:

- David Bandurski, Xi Jinping’s Cathedral of Pretense, China Media Project, 13 October 2023