Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium

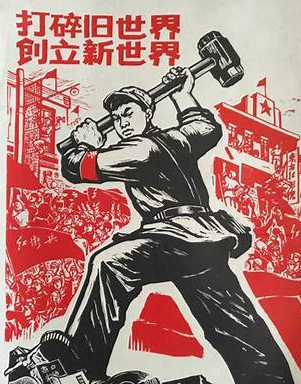

破舊立新

‘As it turned out, it was capitalism after all.’

So goes the first line in Burn Book by Kara Swisher, journalist, entrepreneur and advocate of digital sanity. The subtitle of Burn Book is ‘a tech love story’ and it is Swisher’s account of an industry which grew in tandem with her journalistic career.

The expression ‘burn book’ is a reference to Mean Girls, a 2004 teen-angst-comedy movie in which The Plastics, so called because ‘they’re shiny, fake and hard’, lord it over their schoolmates by keeping a cruel ledger of stories and gossip. The secretive collection of ‘burns’ is used to belittle enemies and demean rivals, as well as to generate malicious rumours just for the heck of it. It is an awesome artifact:

Cady Heron: They have this book, this “Burn Book”, where they write mean things about girls in our grade.

Janis Imi’ike: Ooh. Ooh! What does it say about me?

Cady Heron: You’re not in it.

Janis ‘Imi’ike: Those bitches!

Swisher’s ‘burn book’ is an historical report from the front lines of the burgeoning tech industry of Silicon Valley and the digital revolution that bristles with stories, gossip and feisty pinpointed malice.

***

As Swisher was promoting Burn Book, Netflix released 3 Body Problem, an adaptation of the Chinese sci-fi novel The Three-Body Problem by Liu Cixin. It seemed like an opportune moment both to revisit the moment when the oral historian Sang Ye and I ‘invented’ the Great Fire Wall of China and to digitise the translation I did of an interview Sang Ye conducted with the President of the Chinese UFO Research Organization in the late 1990s. He was also China’s point person who, in accordance with a 1995 decision of the Preparatory Committee for Human Contact with Extraterrestrials, would be number five in a line-up of dignitaries ready to make the first contact with aliens from outer space.

Swisher:

Worst of all, they were different in ways that made no difference. They’d insist that they wanted to “change the world” and “it was all about the journey” and “money was not the goal.” Those were all lies, of course, made more problematic by the fact that these men were lying to themselves most of all.

We conclude with George Orwell’s 1946 review of We, a novel by the Soviet writer Yevgeny Zamyatin written in the early 1920s that has the distinction of being the first work of fiction banned in the Soviet Union. Margaret Atwood writes in a new translation of the novel published in 2021, ‘here is the general plan of later dictatorships and surveillance capitalisms, laid out in “We” as if in a blueprint.’

The action of We takes place 1,000 years in the future; the protagonist of the book, D-503, is the lead engineer of a spaceship called Integral set to travel into outer space to rescue ‘unfamiliar beings on alien planets who may yet live in savage states of freedom.’ Zamyatin’s reversal of the story of Liu Cixin’s Three-body Problem in which aliens are bound for earth was a century ahead of its time.

***

The following essay is catalogued both in Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium and Watching China Watching. Our thanks as ever to Reader # 1 for commenting on the draft of this rambling mediation.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

20 April 2024

***

Contents

(click on a section title to scroll down)

***

How We Invented the Great Firewall of China

Geremie R. Barmé

My own involvement with the digital revolution has been a humble affair. It began in 1985 when I was working on Seeds of Fire: Chinese voices of conscience at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. The second edition of the book, published in New York in 1988, was edited using a Macintosh Plus, the state-of-the-art hardware manufactured by Apple.

The Mac changed everything and future generations of the technology would be a crucial tool in the armory used by the Long Bow Group in Boston to make the historical documentary films and websites that I worked on from 1991 to 2004. The impact of technological innovation on our work was immediate and it was crucial when we designed a website for The Gate of Heavenly Peace, the film we released in late 1995. Like many others, we also experimented with CD-Roms to create an encyclopedia of modern Chinese history in tandem with trying to figure out how to make the Long Bow Archive, a collection of film footage, stills and printed material amassed over decades by Richard Gordon and Carma Hinton, accessible to academics, students, journalists and researchers. Although the maxim of the time was that ‘information wants to be free’, we soon learned that prestigious universities in the Boston area were predominantly interested in asset stripping our work as part of their grand plans to get in on the ground floor of technological advances in pedagogy by using our work to raise capital for other ventures. As Kara Swisher points out in Burn Book, even then it was obvious that what could be would be digitised. It would also be manipulated and monetised by anyone, or institution, that was in a position to do so.

In the breathless introduction to his 1994 book Cyberia, David Rushoff claimed that its publication marked:

a very special moment in our recent history – a moment when anything seemed possible. When an entire subculture – like a kid at a rave trying virtual reality for the first time – saw the wild potentials of marrying the latest computer technologies with the most intimately held dreams and the most ancient spiritual truths. It is a moment that predates America Online, twenty million Internet subscribers, Wired magazine, Bill Clinton, and the information superhighway. But it is a moment that foresaw a whole lot more.

For students of China, the burgeoning of online communication also promised many things; but from its inception Sino-Cyberia was predominantly the dominion of technocrats and it was encrypted along with the ‘path dependency’ of the Chinese Communist Party and those under its sway. The dawning of the Internet age was hailed elsewhere as one of global openness and brotherhood. In China, with its self-regarding traditions of policed borders and aggrieved national pride the idea, and practice, of ‘Internet sovereignty’ 網絡主權 would gradually evolve.

Around the time David Rushoff was waxing lyrical, I published a study of post-1989 Chinese neo-nationalism — To Screw Foreigners is Patriotic and was soon attacked by some of the new (commercial) nationalists I had interviewed as a tool of American cultural imperialism. By then I was collaborating on various projects with the oral historian Sang Ye 桑曄, a writer I’d known ever since he and Zhang Xinxin 張辛欣 made headlines in 1985 with their Chinese Lives 北京人, a series of 100 interviews with people from various walks of life. Influenced by Studs Terkel, it was arguably the first work of China’s citizen journalism and instant history.

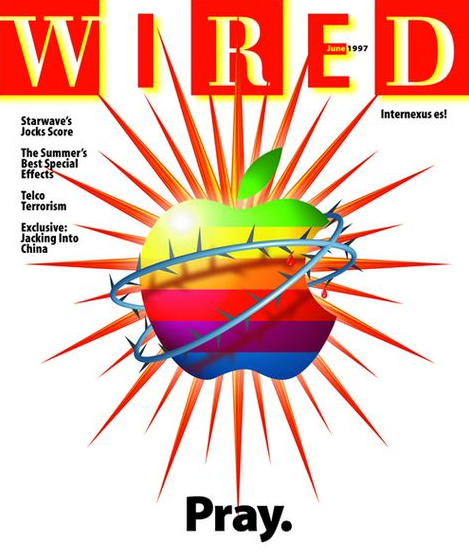

By the mid 1990s, Sang Ye was working on what would become China Candid: the people on the People’s Republic, a series of oral histories that offered a multi-perspective history of post-1949 China. I decided to send the editors of Wired Magazine — celebrated at the time as ‘the Rolling Stone of technology’ — my translation of a conversation Sang Ye had recently had with an outspoken young Beijing tech-head in Haidian, later famed as China’s ‘Silicon Valley’. The translation appeared in the July 1996 issue of Wired under the title Computer Insect. In the introduction to the piece I wrote:

In Chinese, they’re called diannao chong 電腦蟲, or literally, ‘computer insects’. In English, we call them hackers, software pirates, rip-off merchants, or geeks-on-the-make.

In Beijing, computer insects congregate in the university district near the northwest corner of the Chinese capital. It’s a part of town that most Chinese refer to as ‘Electronics Street’ 電子一條街, but for the pros, the pirates, and the hackers, it’s called ‘Thieves Alley’ 騙子一條街, plain and simple. Only one syllable differentiates the two names in Chinese, but that subtle switch is enough to span the gulf between the party line and the gritty truth — the virtual from the real.

Thieves Alley is a haven for China’s massive software pirating industry, and this is an interview with a master of the trade. He’s in his early twenties and wears gray suit pants, Adidas, and a bomber jacket — the uniform of young entrepreneurs in Beijing. A handsome young man with a biting tongue and quick wit, he’s always at the ready to answer his mobile phone. He calls himself one of the Four Heavenly Kings of Hacking, and he’s got enough attitude and ego to make the title stick.

From his mouth pours the brash, in-your-face voice of contemporary China. It’s the voice of a nation proud of its 5,000-year-old culture, but acutely aware that this culture has been humiliated by more than a century of technological backwardness, political decay, and imperialist aggression. The message is unambiguous and unapologetic:

We’re here. We’re mean. Get used to it.

The voice of the brash young Beijinger sparked widespread commentary in the digital community of North America. It was four years before US President Bill Clinton quipped that attempting to control the Internet would be like ‘nailing jello to a wall’. ‘Liberty’, Clinton would boast, ‘will spread by cell phone and phone modem’, he proclaimed. ‘Imagine how much it could change China.’ For those who were mindful of the ways in which pro-party-state people were thinking about the digital revolution and the internet in China in 1996, however, a very different future was already taking shape.

Following the appearance of Computer Insect, Wired commissioned me to undertake a survey of the nascent Chinese Internet and so, in early 1997, Sang Ye and I joined forces. Travelling from the north to the south of the People’s Republic, and then on to Hong Kong we investigated the topic publishing our report in the July 1997 issue of Wired under the title The Great Firewall of China. It was an expression that would acquire a life of its own.

One of our interviewees was the head of the nascent body in charge of cyber security. He summed up their early approach as being ‘You make a problem for us, and we’ll make a law for you.’ In our conclusion we made an observation that unsettled many readers in North America at the time:

For now, the Net in China will remain a privileged realm, enjoyed by the well heeled and well educated, by foreigners, and by the government itself. The cabal of policy makers that is advising the national leadership – Public Security, China Telecom, politically well-connected entrepreneurs – is by no stretch of the imagination enlightened, digitally or otherwise. Internal debate will continue – which organizations or individuals will be allowed to get wired, which will be refused, what those who are online will be allowed to see, and who will profit. The one certainty, given the headstrong Chinese bureaucracy and the Maoist mentality that spawned it, is that China’s adaptations of the Net will be unique, and probably bizarre by Western standards.

China’s Open Door policies have had momentous, mostly uncalculated consequences. But that doesn’t mean that the China of the future is going to look more and more like us. It is going to continue to look like China – and will have the wherewithal to do so. As China gets stronger and more wired, it will still be limited by intellectual narrowness and Sinocentric bias. Pluralism and the open-mindedness that comes with it – the worldly curiosity of previous great powers and the idealism that often supports it – simply are not present. More to the point, they are not about to be encouraged.

Although the expression The Great Fire Wall of China caught on soon enough, our caution about the dark future of the Chinese internet — now frequently referred to as 简中圈 jiǎn zhōng quān, ‘the sphere of Simplified Chinese’ — was not nearly as welcome.

[Note: For more on this topic, see The Great Wall of China: a wonder and a curse!, China Heritage, 27 July 2017. I would note that some online versions of our June 1997 report on the Great Fire Wall appears without attribution. See also: Ziluan Zeng and Yuxuan Jia, Three decades, three paradigm shifts: how the internet transformed China, The East is Read, 7 May 2024.]

***

Star Trek vs. Star Wars

‘Anything that can be digitized would be, I thought many times,’ Swisher writes in Burn Book. Describing herself as being ‘like some tech Cassandra’ and ‘the skunk at the garden party’, she is unapologetic:

I maintained that part of my job was to make that stink and write about where it could all go wrong.

The line ‘as it turned out, it was capitalism after all’ is, as Swisher herself would have to admit, a cutesy faux-naïve opener for a story about rampant capitalism and her account offers and on-the-ground survey of territory long described as technocapitalism. Innovations in the area require further neologisms. In 2014, Shoshana Zuboff identified the salient features of what she called surveillance capitalism and, in 2024, Yanis Varoufakis dubbed the latest development in ‘late capitalism’ technofeudalism. In his book on the subject, Varoufakis argues that:

Apple, Facebook, and Amazon have changed the economy so much that it now resembles Europe’s medieval feudal system. The tech giants are the lords, while everyone else is a peasant, working their land for not much in return.

For those involved in the Chinese world, one might observe that ‘technofeudalism’ has long been germane to understanding ‘socialism with Chinese characteristics’; the party-state and its agents are the lords who mine and harvest wealth from the laboring masses who are popularly dubbed huminerals 人礦 and garlic chives 韭菜 (see Xi Jinping’s Harvest — from reaping Garlic Chives to exploiting Huminerals, 6 January 2023). In the Chinese case today, their inspirational guide/ saviour/ overlord is the latest avatar of the revolutionary personality lauded by Wang Hui 汪暉, China’s leading party-state sophist. (In his work on the subject, Wang eulogises V.I. Lenin, the man who famously declared that ‘Communism is Soviet power plus electrification’.) We would note that the technofeudalism of Varoufakis resonates with the discussion of the Sino-US rivalry in what Timothy Heath at the RAND corporation calls the New Middle Ages.

In China the party-state is building on the solid foundation of the past. As the protagonist of Lu Xun’s Diary of a Madman, published in 1918, writes:

There were no dates in this history, bur scrawled this way and that across every page were the words BENEVOLENCE, RIGHTEOUSNESS, and MORALITY. Since I couldn’t go to sleep anyway, I read that history carefully for most of the night, and finally I began to make out what was written between the lines; the whole volume was filled with a single phrase: EAT PEOPLE!

When promoting Burn Book in early 2024, Swisher frequently referred to her early realisation regarding the juggernaut of digitisation and the threat it posed both to the legacy media and information more generally. ‘Look, in every change in history’, she told a CNN journalist:

there is someone who had the legacy business and didn’t pay attention. And then there is someone who came in and ran rampant using different advantages over the landscape — and that’s what these people did. The mistake was to think they didn’t want your business, that they just wanted to help. Remember the “Twilight Zone” episode “To Serve Man”? It’s a cookbook! I kept saying, “It’s a cookbook, that they want to eat you!” And they’d be like, “No, they’re here to help us.” And I’m like, “They are not here to help you. They’re here to eat you.” It was so obvious to me.

At the end of To Serve Man, which was broadcast in 1962, the narrator intones:

The recollections of one Michael Chambers, with appropriate flashbacks and soliloquy. Or, more simply stated, the evolution of man. The cycle of going from dust to dessert. The metamorphosis from being the ruler of a planet to an ingredient in someone’s soup. It’s tonight’s bill of fare from the Twilight Zone.

In other words, ‘if you aren’t at the table you’re on the menu’. Swisher was quick to appreciate the ravenous appetite of the digital innovators she writes about in Burn Book:

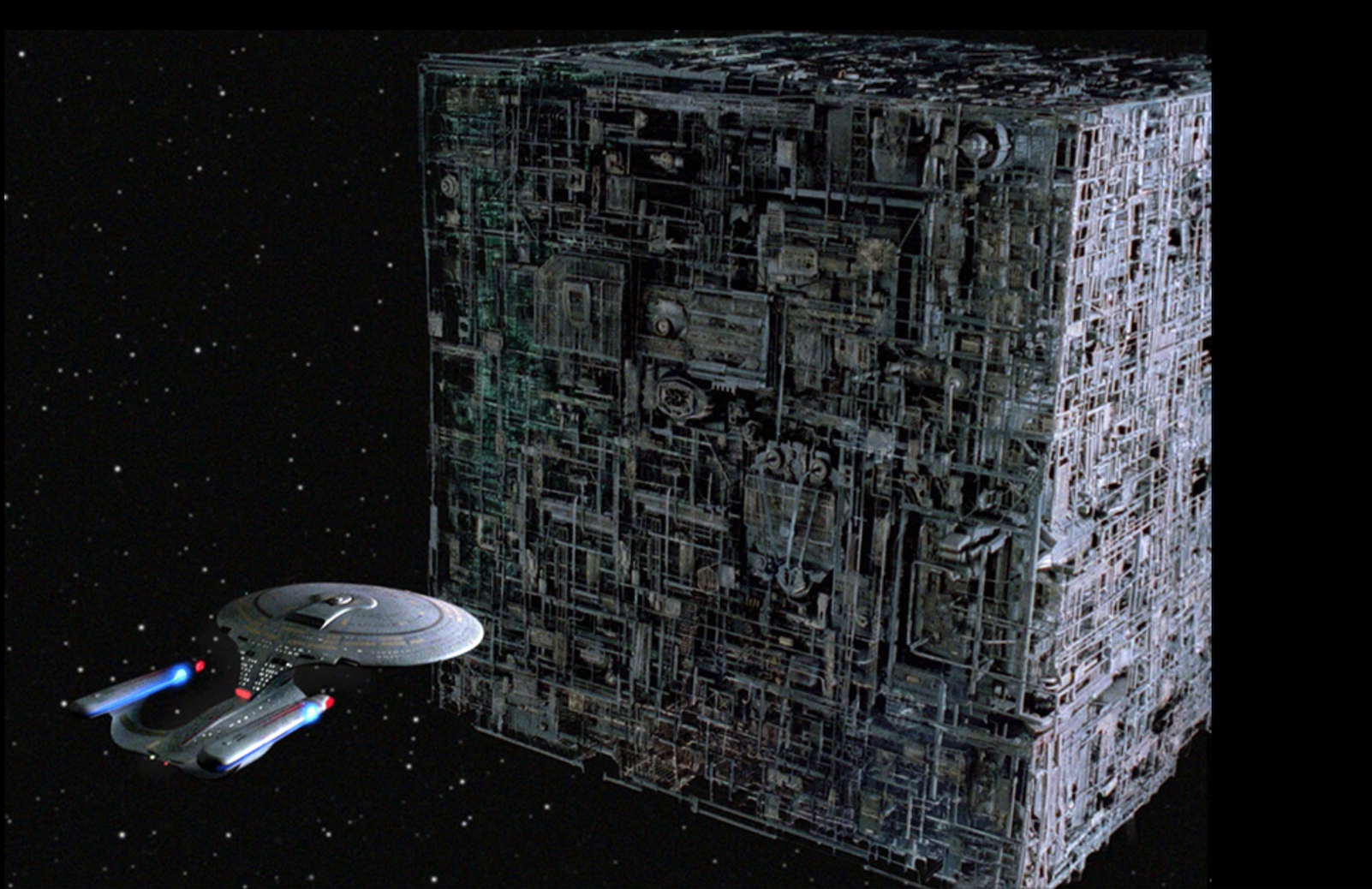

In truth, Google was becoming a Borg that would suck in all the world’s information and then spit it out for profit. And, eventually, resistance would be futile in every media.

The Borg made their first appearance in the TV series Star Trek: The Next Generation in 1989. The timing struck me as being particularly fortuitous since, following the Beijing Massacre of June Fourth that year, it chimed rather neatly with the Chinese Communist Party’s reassertion of its collective will. (See Back When the Sino-US Cold War Began, 1 June 2023.) As I have previously remarked: China’s ideo-social-cultural ultra-stable system 超穩定性結構 — to use a formulation devised by Jin Guantao and Liu Qingfeng in the 1980s — resembles the Borg, an army of cybernetic organisms linked to ‘The Collective’, a hive mind the sole purpose of which is the assimilation of all available ideas and technologies in a quest to achieve perfection. The shibboleth of the Borg — ‘resistance is futile’ — is repeated robotically whenever they encounter opposition. (See Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium, Chapter Seventeen 聚 — Part II, 14 October 2022.)

… the ideology of much of Silicon Valley and the New Right alike … is a conflation of libertarianism, reactionary sentiment, and instinctive anti-wokeism, that characterize Thiel and Silicon Valley fellow-travellers like Elon Musk. It is, at its core, a religious mission …

… Thiel, like many others in Silicon Valley, appears to advocate for a kind of Nietzschean techno-vitalism: a faith not in genuine ideals but in their power to shape and subdue a fundamentally stupid and innately violent populace: a populace who know enough only to want whatever it is they think that other people want… .

… humans fall into two categories. On the one hand, you have the clear-eyed quasi-divine mages of technology, like Francis Bacon. … On the other hand you have the fools, the sheeple, the so-called NPCs, or “non-playable characters” who can be controlled by those who know how to control their desire.

— from Tara Isabella Burton, The Temptation of Peter Thiel, Wisdom of Crowds, 15 November 2023. The focus of Burton’s essay is ‘accelerationist techno-vitalism’.

The irony is the techno-oligarchs, like party engineers of human souls see the masses as sheeple: exploitative resources for extracting value with no volition. They are the sheeple with no free Will while the masses as individuals have volition and consciousness that’s not necessarily locked up in those with the Will to Power. The Techno-optimist Manifesto can profitably be considered alongside the Legalo-Fascist-Stalinism 法日斯 of the Engineers of the Soul in China.

‘As it turned out, it was capitalism after all.’

Generating profit for the tech behemoths of Silicon Valley, whose history and generally venal aspirations are dissected in Burn Book and, for the Chinese party-state, generating the wealth to secure the country’s status and reach as a Superpower 強國. Although it might be a ‘major cyber power, it is not yet a cyber superpower’ 中國已經成為網絡大國,但還不是網絡強國.

As Li Chengpeng, an independent writer who splits his time between Chengdu and Chiang Mai, wrote in an essay welcoming the new year of 2024:

My advice as this new year begins is, don’t just stand out on your balcony chanting “Embrace the New Year, a New Year and New Beginning.” And don’t be fooled into thinking that just because it’s a new year you’ll be paying off your mortgage any time soon, or you’ll be elevated to some new social status. You’re not passing the new year as much as the new year is already passing you by. It’s speeding along as if it were a runner in a relay race and, as the baton is passed on, you’re going to find yourself struggling between the pumping legs of the racers. What you have to do is “remember your mission and hold true to your original intentions” [the Party’s slogan for a national education campaign in 2019]—regardless of the year, people like you and me are just like a bunch of garlic chives; we are all “huminerals”! And, I know that no matter what university my kids end up studying at, in the end it is just another “mining college” [for the training of exploitable “huminerals”].

[Translator’s note: “Garlic chives” (韭菜, jiǔcài) is a vegetable that continues growing after each harvest. It is a popular term used to describe the boundlessly renewable resource of young men and women of working age. In 2022, another old sardonic term for “The People” enjoyed renewed currency. Rén kuàng (人矿), literally “human mine”—also Huminerals, Renmine, Humine, and Humore—first coined in the early 1980s, was widely used to describe the expendable nature of working people.]

— from Li Chengpeng, “When It All Comes down to It, China Has No Real ‘New Year’”, ChinaFile, 21 February 2024

As an official retrospective of the decade since the first meeting of the Central Leading Group for Cybersecurity and Informatization was convened in 2014 at which a ‘grand blueprint’ for turning China into a cyber power was outlined. In a recent retrospective essay published in People’s Daily, the author Xin Ping observes that:

Missing the opportunities of the times is a pain that is deeply engraved in the minds of every Chinese person [the most famous ‘missed opportunity’ in modern Chinese history is the failure of the Tongzhi Restoration of the 1860s]. As one of the greatest inventions of the 20th century, the Internet has brought unprecedented and profound changes to human society, propelling humanity into an era of vitality and hope. Whether one can adapt to and lead the development of the Internet has become a crucial factor in determining the rise and fall of a great nation. To a certain extent, those who grasp the network can grasp the world. Seizing the historical opportunity of the information revolution is a significant strategic choice related to the construction of a strong country and national rejuvenation. 錯失時代機遇,是每個中國人刻骨銘心的痛。作為20世紀人類最偉大的發明之一,互聯網給人類社會帶來了前所未有的深刻變革,推動人類進入活力迸發、充滿希望的信息時代。能不能適應和引領互聯網發展,成為決定大國興衰的一個關鍵。一定程度上說,得網絡者得天下。把握信息革命歷史機遇,是事關強國建設、民族復興的重大戰略抉擇.

— from 信平,這十年,我們闊步邁向網絡強國,《人民日報》, 2024年3月19日

Xin Ping goes on to note that:

At present, there is a historic intersection between the trend of the information revolution and the overall strategic situation of the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation along with the profound changes unseen in a century taking place in the world. General Secretary Xi Jinping pointed out profoundly, ‘informatization has brought the Chinese nation rare opportunities in a thousand years’; ‘we must seize the historical opportunity of informatization development, without any hesitation, without any slack, without letting it slip away, and without making historic mistakes.’ Entering the new era, the Party Central Committee with Comrade Xi Jinping at its core has firmly grasped the ‘time’ and ‘momentum’ of the information revolution, coordinating the promotion of network security and informatization work… 當前,信息革命時代潮流與中華民族偉大復興戰略全局、世界百年未有之大變局發生歷史性交匯。習近平總書記深刻指出:「信息化為中華民族帶來了千載難逢的機遇。」「我們必須抓住信息化發展的歷史機遇,不能有任何遲疑,不能有任何懈怠,不能失之交臂,不能犯歷史性錯誤。」進入新時代,以習近平同志為核心的黨中央牢牢把握信息革命的「時」與「勢」,統籌推進網絡安全和信息化工作。

Of course, given the hagiographic simpering that surrounds China’s party-state-army Chairman of Everything Xi, the report goes on to claim that the Party General Secretary was pondering the digital future as early as the 1980s. Today, he is thinking on a global scale:

With extraordinary theoretical courage, outstanding political wisdom, and strong sense of mission as a Marxist politician, thinker, and strategist, General Secretary Xi Jinping has scientifically applied Marxist standpoints, viewpoints, and methods, based on the foundation of the times, profoundly pointing out that the Internet is the most dynamic field of development in our era. Internet and information technology represents a new productive force and a new direction of development, and information has brought a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to the Chinese nation. Answering the question of the times, he clearly put forward that ‘whoever grasps the Internet will grasp the initiative of the times; whoever disregards the Internet will be left behind by the times’… 当今世界,信息革命时代潮流奔涌向前,以互联网为代表的网络信息技术日益成为创新驱动发展的先导力量,推动社会生产力发生了新的质的飞跃,提出了一系列全新的重大时代课题。习近平总书记以马克思主义政治家、思想家、战略家的非凡理论勇气、卓越政治智慧、强烈使命担当,科学运用马克思主义立场观点方法,立足时代之基,深刻指出互联网是我们这个时代最具发展活力的领域,网信事业代表着新的生产力和新的发展方向,信息化为中华民族带来了千载难逢的机遇。回答时代之问,鲜明提出“谁掌握了互联网,谁就把握住了时代主动权;谁轻视互联网,谁就会被时代所抛弃”。引领时代之变,始终从把握信息时代潮流的高度,对因时而变做好网络安全和信息化工作进行了深刻阐述,彰显出强烈的历史主动精神.

***

In Burn Book, Kara Swisher talks about how she sees the contrasting scenarios for the technological future:

Over time, I’ve come to settle on a theory that tech people embrace one of two pop culture visions of the future. First, there’s the “Star Wars” view, which pits the forces of good against the Dark Side. And, as we know, the Dark Side puts up a disturbingly good fight. While the Death Star gets destroyed, heroes die and then it inevitably gets rebuilt. Evil, in fact, does tend to prevail.

Then there’s the “Star Trek” view, where a crew works together to travel to distant worlds like an interstellar Benetton commercial, promoting tolerance and convincing villains not to be villains. It often works. I am, no surprise, a Trekkie, and I am not alone. At a 2007 AllThingsD conference well-known tech columnist Walt Mossberg and I hosted, Apple legend Steve Jobs appeared onstage and said: “I like Star Trek. I want Star Trek.”

Now Jobs is long dead, and the “Star Wars” version seems to have won. Even if it was never the intention, tech companies became key players in killing our comity and stymieing our politics, our government, our social fabric, and most of all, our minds, by seeding isolation, outrage, and addictive behavior. Innocuous boy-kings who wanted to make the world a better place and ended up cosplaying Darth Vader.

On the other side of the Pacific, an alternative Darth Vader thrives under the impenetrable carapace of the Party General Secretary as those microdosing on Hopium elsewhere reluctantly realise that the choice has never between Star Trek and Star Wars; it’s always been about a Yin-Yang amalgam of the two.

[Note: I’d note that in the ‘Star Wars franchise’ the Ewoks speak variously a vitiated form of Kalmyk and a hybrid of Tibetan with Nepalese. George Lucas wanted a primitive tribe to play a role in bringing down the Galactic Empire and it is well known that the resistance, to which the Ewok belong, are modelled on Viet Cong guerrillas.]

***

Hopium for Humanity in Star Trek

***

&, a Disturbing Lack of Faith in Star Wars

***

‘Speaking of fucked, I am sorry to say: We are.’

‘Speaking of fucked, I am sorry to say: We are.’

Exhibit A: In 2016, Zuckerberg posted on Facebook, “It’s great to be back in Beijing! I kicked off my visit with a run through Tiananmen Square, past the Forbidden City and over to the Temple of Heaven.” The photo he shared with the world shows him in a gray T-shirt and black shorts, blowing past a portrait of Mao Zedong in the background. He has a huge grin on his face, and there’s no acknowledgment that hundreds, maybe thousands, of student protestors were massacred by Chinese government troops in that same place. Zuckerberg was only five years old at the time of the Tiananmen Square Massacre, but it’s hard to believe the topic never came up during his fancy education at Exeter and Harvard. In the photo, Zuckerberg is surrounded by five or six other joggers, presumably from his team. Did none of them know the historical significance of the place? Did someone tell Zuckerberg and he ignored it? Or were they too scared to mention it? When I pressed him about it in a meeting and told him he seemed like a tool of the Chinese government—which had dined out on the photo—he flatly told me no one else had raised this issue with him.

Exhibit B: My next long interview with Mark after the sweaty one took place in mid-2018 when he sat for a Recode Decode podcast and he told me that Holocaust deniers might not mean to lie. …

While Zuckerberg was not evil, not malevolent, not cruel, what he was, and continued to be, was extraordinarily naïve about the forces he had unleashed. Time has since shown that Zuckerberg was woefully unprepared to rein in the power of his digital platform as Facebook’s population swelled to 3 billion active users and it became the most important and vast communications, information, advertising, and media behemoth the world had ever seen.

No, Zuckerberg wasn’t an asshole. He was worse. He was one of the most carelessly dangerous men in the history of technology who didn’t even know it. Unfortunately, he wasn’t the worst of them.

— from ‘The Most Dangerous Man’ in Kara Swisher, Burn Book

***

Judgement Day — YOU ARE BUGS

In The Great Firewall of China we quoted Xia Hong, the PR man for a company called China InfoHighway. He told us that ‘A network that allows individuals to do as they please, lets them go brazenly wherever they wish, is a hegemonistic network that harms the rights of others.’ And he made the following prediction:

As we stand on the cusp of the new century, we need to—and are justified in wanting to—challenge America’s dominant position. Cutting-edge Western technology and the most ancient Eastern culture will be combined to create the basis for dialog in the coming century. In the 21st century, the boundaries will be redrawn. The world is no longer the spiritual colony of America.

Judgment Day for the Internet is fast approaching. At most it can keep going for three to five years. But the end is nigh; the sun is setting in the West, and the glories of the past are gone forever.

— from The Harmonious Evolution of Information, China Beat, 29 January 2010 (this essay followed up on our 1997 report in Wired)

Clarence Shi (Da Shi): You said they weren’t coming for over 400 years. So how do you know they’re gonna be nice?

Ye Wenjie: Nice?

Da Shi: Usually, when people with more advanced technology encounter people with more primitive technology, it doesn’t work out well for the primitives.

[tense music playing]Ye Wenjie: You’re the good cop?

Da Shi: Depends who you ask.

Ye Wenjie: Where’s the bad cop?

Da Shi: Watching. So, 15th of August 1977, E.T. phoned home. You got a reply from the aliens?

Ye Wenjie: Yes. From the San-Ti listener who received my message.

Da Shi: The San-Ti, he… it told you, “Don’t do this. This will be bad for your people.” But you did it anyway.

Ye Wenjie: I did.

Da Shi: Why?

Ye Wenjie: Because our civilization is no longer capable of solving its own problems.

— from ‘Judgement Day’, 3 Body Problem, Season 1 Episode 5

***

In November 1962, at a radar station overlooking the Black Sea at the western edge of Crimea, humankind sent its first message to extraterrestrials. It consisted of just three Russian words in Morse code, bounced off of Venus and ultimately headed towards HD 131336, a star almost 2,160 light years away. The first word, Mir, can be variously translated as ‘world’ or ‘peace’. The other words, Lenin, and SSSR, (the Latinised Russian acronym for the Soviet Union), were a little less ambiguous.

— Matt Reynolds, The almighty tussle over whether we should talk to aliens or not, Wired, 26 September 2018

***

Ye Wenjie 葉文潔, the ‘causus belli,’ at the heart of 3 Body Problem, is an astrophysicist who in her youth witnessed a struggle session at Tsinghua University in Beijing during the violent early phase of the Cultural Revolution. A powerless bystander, she witnessed her father being denounced by Red Guards, abused by her mother and then beaten to death. Despite the taint of the association, Ye is able to pursue her studies in the same field as her dead father and is eventually recruited by the People’s Liberation Army as a technical officer at a secret military base that is involved both in terrestrial surveillance and scanning the heavens for evidence of extraterrestrial life.

Ye Wenjie decides to respond to a message that she receives from an alien civilisation, despite the inherent threat contained in it. Years later, as that nebulous warning becomes a contemporary reality, Ye tells her interrogator, quoted above, that the reason why she had responded to the aliens was because she believed that only outsiders could possibly help humanity solve its problems.

Ye’s determination to aid and abet the destruction of the old world of humanity so that an alien civilisation might build a new world on earth is an ironic fulfillment of the pledge made by the Red Guards who murdered her father to:

Destroy the Old World, Build a New World!

破壞舊世界,創建新世界!

In March 1949, on the eve of the Communist victory on mainland China, Mao addressed a plenary session of the Central Committee of the Party. In his closing remarks he declared that:

We must not only be good at destroying the old world, we will prove to be good at building a new one. 我們不但善於破壞一個舊世界,我們還將善於建設一個新世界。

Only weeks later, the Chairman hailed the capture of Nanjing, the capital of the Republic of China, with a poem which included the line: ‘In heroic triumph heaven and earth have been overturned’ 天翻地覆慨而慷. Thereafter, he would constantly contrast the new China with its dark predecessor. A decade later as his Great Leap Forward ravaged the nation he waxed lyrical during a visit to his birthplace, claiming that his party-state-army ‘dare to make sun and moon shine in new skies’ 敢教日月換新天.

To destroy the old world so as to build it anew was also the avowed ethos of the Cultural Revolution. One of the key additions that Mao made to the May Sixteenth Communique, the Communist Party’s formal announcement of the Cultural Revolution in 1966, read:

Nothing new can be built without destruction. Destruction is criticism, revolution. Destruction requires reasoned argument which is in turn construction. The word ‘destruction’ takes the lead, construction follows in its wake. 不破不立。破,就是批判,就是革命。破,就要講道理,講道理就是立,破字當頭,立也就在其中了。

We’ll wield our powerful cudgel, armed with magical powers, and turn the old world on its head and remake the universe. We’ll devastate and pulverise everything and create chaos as we go, the more chaotic we make everything the better. 我們就是要掄大棒、顯神通、施法力,把舊世界打個天翻地覆,打個人仰馬翻,打個落花流水,打得亂亂的,越亂越好!

These lines come from the Red Guard manifesto of 1966 to which Mao Zedong replied on 1 August 1966 expressing his support for their rebellion.

Marx said: the proletariat must emancipate not only itself but all mankind. If it cannot emancipate all mankind, then the proletariat itself will not be able to achieve final emancipation. 馬克思說,無產階級不但要解放自己,而且要解放全人類,如果不能解放全人類,無產階級自己就不能最後地得到解放。

Superficially at least, these sentiments appeared to echo the popular, if erroneous, interpretation of Thesis Eleven in Karl Marx’s Theses On Feuerbach: ‘The philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways; the point, however, is to change it.’

The fervour of Maoism built not only on an iconoclastic tradition dating from the French Revolution, the Paris Commune and the October Revolution, it was also part of a modern lineage linked to the Taiping Civil War. The Heavenly Kingdom would replace the rule of the Manchu-Qing with a new heaven and a new earth. Both its rhetoric and behaviour were violent and uncompromising. Just as the Boxer uprising of 1900 shared a lineage with the Taiping, so too did the racist pogroms and destructive fury of the first years of the Republic of China. Millennial extremism and overheated rhetoric have been an undercurrent in Chinese political life ever since. The Cultural Revolution is part of an indigenous Chinese history that dates back to the Taiping.

[Note: For more on this topic, see Zi Zhongyun, 1900 & 2020 — An Old Anxiety in a New Era, 28 April 2020.]

The more immediate origins and year-span of the Cultural Revolution itself are also confounding. It is a lazy convention to accept the Chinese Communist Party’s timeline of events although, in fact, shortly after the failure of the Great Leap Forward Mao began planning to reprise his radical utopian vision. During his speech at the Meeting of the Seven Thousand Cadres convened in September 1962 to address the recent disaster, Mao not only skirted around the subject of his responsibility for what is widely regarded as being the largest man-made famine in human history, he also hinted at his strategy to pursue his goals through other means. Despite the meeting focussing on the need for urgent economic recovery, Mao’s priority remained ever greater political purity. ‘From now on,’ he declared, ‘class struggle must be the theme of every year and repeatedly emphasised month after month. It must be the theme whenever we convene plenums and whenever a Party committee holds a meeting. It must be emphasised at every meeting for only then will we develop a clear-headed Marxist understanding of things.’ 從現在起以後要年年講階級鬥爭,月月講,開大會講,黨代會要講,開一次會要講一次,以使我們有清醒的馬列主義的頭腦。

Even as some of the stifling controls over the economy were relaxed, Mao launched a campaign the slogan of which was ‘Never Forget Class Struggle’ 千萬不要忘記階級鬥爭。The message was repeated ad nauseam in the media, as well as in films, theatre productions, songs and poetry competitions. It was also the focus of a new wave of radicalisation in education and everything from kindergarten classes to university lectures were affected.

In 1963, the Four Cleans Movement, also known as the Socialist Education Campaign, swept rural China with the aim of identifying, denouncing and re-educating Party cadres who were ‘taking the capitalist road’ 走資派. As a precursor to the formal Cultural Revolution, the Four Cleans, the fourfold aim of which was to ‘purify politics, purify economics, purify the organization, and purify thought’, was accompanied by mass meetings at which local cadres were subjected to violent denunciations, forced to engage in self-criticisms and judged in kangaroo courts. The tactics recalled the Party’s harsh process of thought reform during the Rectification Campaign in the wartime base of Yan’an in the early 1940s, one that the Party imposed on the general populace after 1949. Both were a precursor to what would come in 1966.

Radicalisation in the educational sphere was spearheaded by hardline Maoist activists among both teachers and administrators. Their extreme rhetoric and a targeted effort at releasing the inchoate and violent id that had repeatedly roiled the country from the time of the Taiping War a century earlier, created a feverish atmosphere among the impressionable adolescents. They were taught that devious class enemies and traitors were omnipresent; they threatened to betray the revolution and turn China into slave of the West.

The young were effectively subjected to ‘gaslighting’. A process that, according to Kate Abramson, a philosophy professor and author in 2014 of Turning Up the Lights on Gaslighting, ‘is not the same as brainwashing … because it involves not simply convincing someone of something that isn’t true but, rather, convincing that person to distrust their own capacity to distinguish truth from falsehood.’

The zealotry reached a crescendo in 1966 and, when Mao and Party Central formally launched the Cultural Revolution in the middle of the year. Not surprisingly, students turned on the selfsame teachers who had primed fanatical devotion in them for years. The educators were now regarded as being part of a covert reactionary and revisionist establishment that plotted in a myriad of ways to frustrate the revolution. Chairman Mao and his comrades called on the young to destroy the status quo so that the true revolutionary line in education could finally be implemented. Quoting Mao, the middle-school students who founded the Red Guard movement declared that ‘rebellion is justified’ and in the violent ecstasy of revolutionary romanticism a line from one of Mao’s poems became the currency of the day:

The Golden Monkey wrathfully swings his massive cudgel

And the jade-like firmament is cleared of dust.

金猴奮起千鈞棒,

玉宇澄清萬里埃。

And, as we noted above, in their manifesto, the Red Guards trumpeted their mission:

We will wield that massive cudgel ourselves. We will prove our invincibility and the force of our righteousness. In the process we will turn the old world on its head, throw things into confusion and devastate everything. We’ll create absolute chaos, the more chaotic the better!

我們就是要掄大棒、顯神通、施法力,把舊世界打個天翻地覆,打個人仰馬翻,打個落花流水,打得亂亂的,越亂越好!

A famous early victim of the bloodthirsty student rebels was Bian Zhongyun 卞仲耘, a school administrator in Beijing. She was previously known as a model Party hardliner praised for her uncompromising zealotry. Her death at the hands of a clutch of her students is the subject of Though I Am Gone, a documentary film centered on the emotive testimony of her husband that panegyrises the long-dead Maoist zealot.

Like the Red Guards and their mentors, Ye Wenjie, the angular-faced, holier-than-thou anti-hero of 3 Body Problem is brought low by her own pitiless sense of mission. Her immediate followers are arrested while the other members of her cult travel the high seas with their families on Judgement Day, a decommissioned oil tanker under the command of Mike Evans, her partner. The authorities, determined to lay their hands on the communications that ‘the movement’ of Ye and Evans have had with the aliens, devise a plan that will literally shred Judgement Day so they obtain a precious device with the stored data. As Christopher T. Fan puts it in his review of the series:

When the movement’s leader, an American named Mike Evans, finally clocks what’s happening to his ship and its passengers, he drops to his knees and presses the precious hard drive to his heart a beat before he’s zithered. The Netflix adaptation depicts the drive as an index card–sized red block that resembles a little red book—a striking embellishment not found in any other version. Given the pivotal role that the Cultural Revolution plays in the story, as proof positive that humanity deserves only the worst, this little red drive might symbolize the misguided fervor of Maoism. It might even be tempting to read it as symbolic of a post-2008 American fantasy about “capitalism with Chinese characteristics”—the secrets of economic growth revealed only to acolytes like Evans who embrace the good news of the United States’ future overlords.

Fan the poses a rhetorical question and provides an answer that chimes with our thesis that ‘as it turns out, it is capitalism after all’:

Little red drive—or little red herring? The allegorical confusion here might actually offer us a moment of clarity. Reversing the allegory and imagining 2024 America as a version of 2006 China reveals not so much how both are the same but how globalization continues apace, even if apparently under more than one aegis: Evans’s drive is both China red and Netflix red. Evans and his movement refer to the San-Ti as “Our Lord.” One thing that has certainly become clearer since 2006 is that the US and China are both beholden to the same sovereign. If the San-Ti are going to kill us all, it’s because they’re figures for global capital itself, and the stakes are not geopolitical but planetary. Four hundred years left actually sounds pretty good.

Capitalism, like Stalino-Maoist socialism and its heirs, shreds the old world in a tireless process of self-aggrandising creation.

***

China’s ‘second revolution’ — the period I call High Maoism (from 1957 to 1976) — ended up devouring its own, but that was by no means an aberration; it was of a piece with the reign of terror that the Communist Party had visited on the Chinese nation from 1949 just as the harvesting of ‘garlic chives’ today is undertaken to feed a quest for wealth and strength that began 150 years ago.

[Note: For more on the Cultural Revolution, see Morning Sun, a film and website released by the Long Bow Group in 2003.]

***

The controversial opening scene of 3 Body Problem, the Netflix adaptation of Liu Cixin’s novel, depicts a mass struggle session at Tsinghua University in the early months of the Cultural Revolution. The anachronistic jumble of slogans that festoon the stage (some dating from much later in the movement) are a visual shorthand for a period that covered the murderous first two years of the movement.

The scene, and in particular its bloody denouement, were immediately controversial. As Li Yuan of the New York Times reported:

Instead of pride and celebration, the Netflix series has been met with anger, sneer and suspicion in China. The reactions show how years of censorship and indoctrination have shaped the public perspectives of China’s relations with the outside world. They don’t take pride where it’s due and take offense too easily. They also take entertainment too seriously and history and politics too lightly. The years of Chinese censorship have also muted the people’s grasp of what happened in the Cultural Revolution.

Some commenters said that the series got made mainly because Netflix, or rather the West, wanted to demonize China by showing the political violence during the Cultural Revolution, which was one of the darkest periods in the history of the People’s Republic of China.

“Netflix is just pandering to Western tastes, especially in the opening scene,” said one person on the social media platform Weibo.

The blockbuster books and their author, Liu Cixin, have a cultlike following in China. That’s not surprising because Chinese society, from senior leadership, scientists, entrepreneurs to people on the street, is steeped in techno utopianism. …

If their main complaint about the Netflix adaptation is that the creators took too much liberty with the plot and the main characters, their other major complaint is that the opening scene about the Cultural Revolution is too truthful or too violent.

Some doubted the necessity of mentioning the political event at all. Others accused the show of exaggerating the level of violence in the struggle session.

Scholars believe that 1.5 million to eight million people died in “abnormal deaths” in the decade from 1966 to 1976, while more than 100 million Chinese were affected by the period’s upheaval.

Any discussion of the Cultural Revolution, a political movement that Mao Zedong started in 1966 to reassert authority by setting radical youths against those in charge, is heavily censored in China. Mr. Liu, the author, had to move the depiction of the struggle session from the beginning of the first volume to the middle because his editor was worried it couldn’t get past the censors. The English translation opened with the scene, with Mr. Liu’s approval.

“The Cultural Revolution appears because it’s essential to the plot,” Mr. Liu told my colleague Alexandra Alter in 2019. “The protagonist needs to have total despair in humanity.” …

There’s a cottage industry of making videos on Chinese social media about “The Three Body Problem.” But few dare to address what led the daughter, a physicist, to invite the aliens to invade the Earth. A video with more than five million views on the website Baidu referred to the Cultural Revolution as “the red period” without explaining what happened. Another video with more than eight million views on the video site Bilibili called it “the what you know event.”

It’s not surprising that fans of the book may have heard of the Cultural Revolution, but they don’t have a concrete idea about the atrocities that the Communist Party and some ordinary Chinese committed. That’s why the reactions to the Netflix series are concerning to some Chinese.

A human rights lawyer posted on WeChat that because of his age, he saw some struggle sessions when he was a child. “If I lived a bit longer, I might even get to experience it firsthand,” he wrote. “It’s not called reincarnation. It’s called history.”

— Li Yuan, What Chinese Outrage Over ‘3 Body Problem’ Says About China, New York Times, 8 April 2024

Li Yuan followed up her article in the Times by interviewing ‘Auntie Gao’ 高阿姨, a nonagenarian who was a student at Tsinghua University during the early days of the Cultural Revolution, on her podcast Who Gets It 不明白播客. Gao, who watched the first episode with members of the three generations of her family, tells Yuan that she thought the scene of the struggle session at Tsinghua powerfully encapsulated the hysterical atmosphere and violence of the time. The slogans compress a number of years into one scene, a kind of artistic license that someone like Auntie Gao — a member of what, it should be remembered, is modern China’s most hypercritical generation — found acceptable.

Auntie Gao: … my kids asked me whether it was really that brutal? I immediately responded that yes, it was.

Although no one was beaten to death at a public struggle session at Tsinghua, I feel that the series represented in shorthand form the situation at the time. It really was that cruel. That’s why I’ve said that this version of the Three-body Problem is pretty realistic. Who would have thought that a few minutes of screen time would elicit such a response worldwide? It’s as though people have forgotten what the Cultural Revolution was really like. They’ve forgotten how brutal and violent it was.

孩子們就問我說有那麼殘忍嗎?我馬上回答有。雖然在清華的批鬥現場上沒有打死過人,但是我覺得這個電影是濃縮了那個時候的情況,真的這麼殘忍。所以這些方面我覺得這個《三體》的表現是比較真實的,而且沒有想到幾分鐘的場景,在全世界引起這麼大的反響,好像人們確實忘了文革,忘記它有這麼殘忍、暴力了。

— 袁莉,高阿姨:我目睹了奈飛版《三體》中的文革暴力,《不明白博客》,2024年4月13日

To reiterate the point made above, although her father was murdered by Red Guards during the Tsinghua rally, Ye Wenjie ends up behaving like the ultimate Red Guard, one motivated to ‘destroy the old world’ 打碎舊世界, an ethos that was nurtured and engineered by Mao Zedong, the Communist Party and the Chinese revolution over many years.

Like the Red Guards at Tsinghua, Ye was educated under Maoism just as her ill-fated father would have been transformed by the Thought Re-education Campaign of the early 1950s and the political ructions that followed. In her own twisted way Ye Wenjie shares a kind of radical idealism with her enemies; it is one that is still the bane of humanity, be it in fiction or in reality.

Mao’s 1949 pledge to destroy the old world and create a new order has resonances far beyond the first three decades of the People’s Republic. Beyond the campaign to Eradicate the Four Olds and Establish the Four News 破四舊、立四新 in 1966, the slogan ‘destroy to build’ 不破不立, like many other aspects of the Maoist past, enjoys a new lease on life under Xi Jinping, a man who wears the badge of his Maoist past with pride. As recently as September 2019, during an official visit to the Revolutionary Memorial at Xiangshan in northwest Beijing, Xi reminded the nation that:

History has proven that the Chinese Communist Party and the Chinese People are not only capable of destroying the old world, but also good at building a new world. As we look ahead, the prospects for a beautiful future are limitless. 歷史充分證明,中國共產黨和中國人民不僅善於打破一個舊世界,而且善於建設一個新世界。展望未來,中國的發展前景無限美好。

Now, like the fictional Trisolarans in 3 Body Problem, Xi Jinping and the Chinese Communist Party are at pains to advance the cause of their destructive-creative enterprise globally. To do so, they are, in effect, gaslighting the world.

[Note: Merriam-Webster defines gaslighting as the ‘psychological manipulation of a person usually over an extended period of time that causes the victim to question the validity of their own thoughts, perception of reality, or memories and typically leads to confusion, loss of confidence and self-esteem, uncertainty of one’s emotional or mental stability, and a dependency on the perpetrator.’]

***

Beam Me Up: the UFOlogist

An Oral History Interview by Sang Ye

translated by Geremie R. Barmé

Born in Shanghai in 1937, he received a degree in international trade from a university in Beijing in 1962. He had been President of the Chinese UFO Research Organization since 1986 and would, in accordance with a 1995 decision of the Preparatory Committee for Human Contact with Extraterrestrials, be number five in a line-up of dignitaries ready to make the first contact. The list was headed by Boutros Boutros-Ghali, the former Secretary-General of the United Nations, and former US President Jimmy Carter. Apart from his work as founder of China’s National Federation of UFO organizations, according to his name card he was also a university professor, a consultant to the Executive Board of the National Association of Qigong Science, a Superior Assessor of the Institute of Paranormal Studies, a member of the Executive Board of the Investigation Association on the Hong Kong and Macao Economies, a permanent member of the Executive Council of the International Association of Cultural and Commercial Development (USA), etcetera, etcetera. Over the past thirty years he had had various careers as a diplomat, interpreter, research scholar and government bureaucrat.

Many people in China have been fortunate enough to see UFOs, myself included. My own sighting was during the darkest age of Chinese history. It was 1970, and I was at a May Seventh Cadre School in the countryside. Only one year earlier I had been in the stratosphere myself when I acted as Chairman Mao’s Spanish interpreter. I was one of the lucky few who spent some time in the presence of our own Red Sun. In 1970, however, I had very much returned to terra firma. I was undergoing self-renewal through labor and thought reform.

Of course I didn’t think that extraterrestrials would be our salvation. It never occurred to me; no one would think that. Anyway, there’s no such thing as a savior. The only person qualified to save us was Chairman Mao. He’d already liberated us and now we were working to save others, to liberate all of humanity. At the time we were incessantly warned that we were surrounded by enemies: American imperialism on the one hand and Soviet revisionism on the other. We faced the ever-present threat of a new world war. The Soviets encroached on our borders so they were the more dangerous foe; they might launch an invasion at any moment. That’s why when I saw my UFO the last thing I thought of was extraterrestrials. I was convinced it was the Russians.

It was dark and the UFO was as bright as a full moon, though smaller. It was turning over and over in the sky, maybe that’s how it generated power. There are many ways of generating power, after all. For example, you can wind an automatic watch just by moving your hand.

I don’t know if that’s how this particular UFO worked but I believe we should be prepared to entertain such hypotheses. Our race, the human race in the twentieth century, may be relatively familiar with our own immediate physical environment, which we can access though our own senses and artificial extensions of them—various tools and instruments—but there is no conclusive proof to suggest that the universe conforms with our narrow perceptions of it. After all, it’s only in the last three decades with the development of space technology that we’ve been able to search for extraterrestrial civilizations. Of course, up until now these efforts have proved fruitless, but we must be willing to admit that we are hardly in an ideal position to explore the universe yet. Our efforts to learn the truth are frustrated by the limitations of modern science, and it may take several generations before we get some results.

Telescopes extend our range of vision, just as spacecraft act as new means for physical movement. Humankind may have taken one giant step on the moon, but it was still just one step. We are still a long way from understanding the world, let alone the universe. I attended a UFO conference in Brisbane not too long ago. I was there for a few days and saw a number of places, but on that basis alone I could hardly claim to know Australia.

Every year we hear of numerous eyewitness reports of sightings. There’s been an increased frequency of sightings and also of the discovery of physical evidence of visitations, particularly in the last few years. People have taken pictures of UFOs, and some have actually been on board them. People have even found the remains of spacecraft. However, scientists remain sceptical, even when presented with the actual pieces. All they can tell us is that some of the metal shards are special alloys. Although they maintain they’re not from UFOs, they can’t really say for sure. The point is that the facts behind all of this evidence are far beyond the realm of general human experience. People’s minds are closed to other possibilities and, when they are confronted with something that’s outside the bounds of the conventional, they feel threatened. Apart from that, a UFO experience cannot be repeated on demand; we can’t replay it at will—so all of the evidence remains inconclusive. Life is short and opportunities are limited. If you say that the only way you’ll be convinced about the existence of UFOs is if you can see one, get on board and bring back some concrete evidence then, given the present situation, we have a problem. UFOs aren’t at your beck and call.

Our organization has numerous contacts with scientists, and a number of our members are top-ranking scientists. Take Xue Chengwei, for example, the present head of our Beijing Branch. He’s a noted rocket scientist. And Shen Shituan, our honorary chairperson, is the President of the Chinese Aeronautical University. We also welcome the most hardened sceptics who are convinced that there’s no such thing as extraterrestrial life. Zhou Yousuo, for instance, insists that UFOs are nothing more than atmospheric phenomena or balls of plasma. He claims that he can reproduce these so-called UFO phenomena in his laboratory on request.

That’s to say, even top scientists have blind spots. We are all limited by our contingent framework of knowledge. Our thinking is bound by objective conditions; our views and methodologies are similarly constrained. I am convinced by facts, not by the reproduction of plasma effects in a laboratory. Zhou may well argue that the UFO I witnessed was nothing more than a ball of plasma, but that doesn’t deter me. He can keep on saying that. What I find convincing is something like the map of Piri Reis. Once upon a time people treated that old parchment document as though it was little more than a joke, a wildly inaccurate fantasy. But as human knowledge has advanced it’s proved to be extraordinarily accurate. Although Antarctica looks a bit misshapen to us, it just happened to be marked in the correct position on the map 8,000 years ago. Today we have to rely on satellites and spaceships to get such accurate pictures of the earth. I believe people 8,000 years ago must have needed them as well.

We have a membership of over five thousand, most of whom have had a university education. Our funding comes from a range of sources: membership fees, financial support from local government technical and scientific associations, and grants that we’ve gone out and applied for ourselves. The central government has never given us a cent.

No, we don’t get any help from extraterrestrials either! Though, to be more precise, I should say that we have no evidence that we’ve received support from extraterrestrials. Again, because of our limited perceptions it is impossible to say categorically whether we’ve been getting covert aid or not. Naturally, that brings us to the question of Men in Black. MIBs are extraterrestrials who live among us disguised as human beings. They’re more than just observers, as they also take part in human affairs. They have great power, and they play an important role in fostering—and actively discouraging and preventing—certain developments on earth.

As superior life forms they are a force for the good. They constantly inspire humanity and contribute to our collective wisdom, helping us move on to ever-higher planes of civilization. Statistical studies done overseas have shown that some eighty percent of all important discoveries throughout history were made semi-consciously or by people in a state of hypnotic suggestion. It’s more than likely that these discoveries were actually inspired by aliens transmitting information through extrasensory perception. It’s also possible that they’ve employed other media to relay messages. For example, some scientists admit they’ve received documents containing data that’s a little more advanced than contemporary scientific research—more advanced, but not so far ahead of our own science that it’s beyond our comprehension. They’ve never been able to discover the genius behind it.

As to the question of how aliens have hindered certain developments on earth, we are convinced that MIBs have prevented us from pursuing in-depth research into certain mysterious phenomena. In some cases, they actively discourage people from their investigations. That’s why, on one level, UFOs remain just that: Unidentified Flying Objects. The mystery may itself be the result of direct intervention by MIBs. Manipulating politicians and scientific authorities to launch attacks on so-called pseudo-science is one of their most common tactics.

During his presidential campaign Jimmy Carter announced his commitment to making public all government information related to UFOs, but when he got into office he reneged on that pledge. Making these things public could have been the single most important political decision in the history of the human race. By revealing those secrets he could have sparked widespread social chaos, as well as creating a major threat to established religions and belief systems. But that was only one reason for his decision. There may well have been another: the aliens themselves decided they didn’t want to reveal themselves. Perhaps everything that has happened is part of an elaborate extraterrestrial ruse.

[Editor’s Note: In March 2024, the All-Domain Anomaly Resolution Office of the Defense Department of the United States released a study that found no evidence of aliens or extraterrestrial intelligence.]

The time isn’t yet ripe for aliens to establish open and sociable communications with humanity. Although we’ve been in contact now for at least ten thousand years, the gap between our civilizations is still far too great. If relations were established today that led to people-to-alien exchanges and visits I fear it would be counterproductive for both sides. It’s like a relay race. We want to take the baton from those running ahead of us, but we’re too slow. We have to put on a spurt to get up to speed. The baton cannot be handed over until we are running fast enough.

As for the origins of our species, people in China generally accept the Darwinian-Marxist theory that we have evolved from apes through manual work. But if you look at it from another angle, you could just as well argue that the human race is part of an alien experiment. This is not unreasonable. After all, modern science has proved that it must have taken longer than the known lifespan of the earth—calculated to be forty-six billion years—for humans to have evolved from the simplest organism. Thus, it is quite likely that aliens developed our human stock elsewhere and then transferred it to the earth where we have gradually evolved to the stage at which we find ourselves today.

But I don’t believe that aliens observe us in the same way, say, that we watch ants fighting with each other. Certainly, the earth has been supervised and controlled by extraterrestrials throughout human history and will continue to be in the future, but that knowledge doesn’t change my view of life itself. It hasn’t made me particularly fatalistic or pessimistic.

Jesus Christ could have been an extraterrestrial. After all, he cured diseases and averted disasters with telekinesis. He even modified the spiritual make-up of human kind. There are many accounts of his powers. As for other gods, spirits and the bodhisattvas, so-called ‘idols,’ there is nothing mysterious about them at all. They are all agents of alien intelligence.

Chairman Mao? Chairman Mao was Chairman Mao, plain and simple.

As for other mystical phenomena like astrology, fortune telling, the belief in superior civilizations that existed before recorded history, and so on, I’m interested in them all, especially extrasensory perception and qigong. UFO research is a vast field that inevitably leads to an investigation of all of these things. But, take my word for it, I’m not gullible; I don’t believe everything. The deceptions of fake qigong masters and the like have negative effects on our work, though they’re not all that damaging. After all, our organization pursues aims that are closely related to the work of modern science. Ours is a serious enterprise that has nothing to do with the gamut of superstitious qigong beliefs, and all that talk about adepts who have trained secretly in the mountains for five hundred years or inherited a tradition handed down by masters over several generations, and such like.

False UFO sightings are reported for any number of reasons. Some are honest errors of judgment by people who have mistaken natural phenomena for UFOs. Some are also hoaxes concocted by individuals who have nothing better to do with their lives than make up wild stories for their own amusement. The perpetrators are usually crooks who are trying to work some swindle. They act in a secretive and covert fashion but, despite their best efforts to fabricate fake aliens, alien medicines, alien agents, intergalactic linguistics, and so on, their scams are easily exposed.

Just because you come across a few fakes is no reason to think that real ones don’t exist. There’ve been cases of itinerant workers in China pretending to be the children of high-level cadres. But they’ve only been able to get away with it because there really are high-level cadres.

In general, the state maintains a hands-off attitude towards the issue of UFOs. This allows us to pursue our activities in an environment that’s so relaxed that even our overseas colleagues are quite surprised. Despite this, however, our legitimacy is still questioned: conventional science does not recognize the validity of our inquiries.

‘You’re just like a small group of religious fanatics. How can you be sure your beliefs aren’t just another heresy?’ Journalists asked me questions like that when members of the Heaven’s Gate cult in America committed suicide [in 1997] in the belief they’d be taken to heaven by an alien mother ship hidden in the tail of the Hale-Bopp Comet. I said it was an excellent question, but that no, we can’t find anyone qualified to act as a guarantor of our beliefs. However, the cult members who committed suicide do not represent us, or our beliefs. Indeed there may have been a quirky extraterrestrial among them with strong non-scientific fixations. Their leader may have been such a being and that explains how he attracted all those aberrant followers.

I told that reporter just to forget all about it. But enough of that, let’s get back to what we were talking about.

I don’t want to get involved in discussing the policies of the past. For the moment at least the government is concentrating its efforts on building up China’s market economy. People fortunate enough to be living in this transitional age are easily overwhelmed by materialism; they lose sight of the important things in life. That’s why I believe that our mission to explore a phenomenon that many people believe doesn’t even exist, that is to say alien civilization, is of value in and of itself. We can claim that we have already achieved something: we are doing our best to provide some spiritual nourishment for a pragmatic society.

I’m in a minority even at home. My sons don’t believe in aliens, and their mother is even more skeptical. They’re extremely critical of my views. That makes it three against one, and one of them is a high-level cadre into the bargain: my wife is a bureau chief. If we were all on an American-style jury they’d have to work very hard to get me to agree with their verdict. In China that’s not necessary; the minority has to defer to the will of the majority.

The thing is that there’s no jury to adjudicate on these issues. If you don’t agree, that’s your tough luck; there’s no place for you to make your case. As for being allowed to arbitrate yourself, you couldn’t imagine it even in your wildest dreams. The truth will never be put in the dock and tried. People who take it upon themselves to judge the truth will be struck down to the sound of God’s laughter.

Human knowledge can no longer be simplistically categorized into opposing schools of materialism and idealism. We have to contemplate the problems facing humanity from a higher level. If you insist on labeling my approach in terms of some ‘ism’ or other, I suppose you could say it’s a superior form of materialism. But even that’s an artificial category. Trying to draw a distinction between science and pseudo-science is always a subjective exercise. If you are confronted by something that can’t be found in any of your weighty tomes then you shouldn’t presume that you’re in a position to judge its validity impartially.

History has proved that most of the predictions that Nostradamus made three centuries ago were accurate, including the timing of the explosion of China’s first hydrogen bomb. The new millennium is upon us. Whether or not the Armageddon he foresaw will come to pass is a pressing issue. But to obsess about such things only serves to undermine our commitment to life in the here and now. Our very existence on this planet is precarious and perhaps one day humanity will be confronted with a holocaust of its own making. That’s when I believe aliens will come to our aid. And when they do appear on earth, our small group–the Preparatory Committee for Human Contact with Extraterrestrials—will be ready to carry out the task for which it was set up.

Yes, of course, I’m a member of the Chinese Communist Party.

[Editor’s Note:

Sang Ye subsequently chanced again upon the President of the Chinese UFO Research Organization again at the time of the Falun Gong protests [in 1999]. The Chinese Communist Party was attempting to deal with the followers of the nationwide cult which boasted sixty million adherents on the mainland and had staged a surprise protest outside the party headquarters, Zhongnan Hai. Meanwhile, there was more stirring news from the front for UFO activists. The president told Sang Ye that a higher form of intelligence formerly covertly active in northeast China was preparing to move on Beijing. This being had already revealed that many Chinese politicians and social leaders were actually aliens. Despite this confirmation that perhaps even Chairman Mao had been an ET in disguise, the visitors to earth were experiencing financial difficulties. Increased economic pressures meant that finding new sources of funding had become a key issue for further UFO research; more importantly, the aliens active in human guise—the MIBs—needed more money themselves to deal with the inflationary pressures that they were experiencing both in reformist China and elsewhere. Despite these problems, the most startling news was that researchers in China had uncovered the secret of propulsion used by alien spacecraft, as well as having discovered an alien-sourced cure for cancer, among other diseases. ‘As a by-product of our investigations into UFO phenomena,’ the president remarked to Sang, ‘these discoveries will not only have a profound impact on the economic well-being of China, but will have long-term payoffs for our nation in terms of energy resources, transportation and medicine. This will put China at the forefront of the advanced nations in the new millennium.’

In parting he reminded Sang Ye that their activities were sanctioned by no less an authority than Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, for did not that great Russian revolutionary say, ‘Contact with extraterrestrials will force mankind to radically revise all pre-existing philosophical and moral tenets’?]

***

Source:

- Sang Ye, ‘Beam me up’, trans. Geremie R. Barmé, Humanities Research, 2, 1999: 71-78, included in Sang Ye, China Candid: the people on the People’s Republic, edited by Geremie R. Barmé, with Miriam Lang, University of California Press, 2004, pp.289-297. The Chinese text was published in 桑曄,《1949,1989,1999》,香港:牛津大学出版社,1999

We

George Orwell on Yevgeny Zamyatin

Orwell’s novels Animal Farm and 1984 were on my high-school syllabus. It was during Star Trek screening. I didn’t read Zamyatin’s We until the 1980s.

In The Threnody of Tedium, a ‘tally’ that introduces the series Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium, we observed that Xi’s tenure as Chairman of Everything, Everyone and Everywhere brings to mind the words of the grand inquisitor O’Brien in 1984:

‘But always – do not forget this, Winston – always there will be the intoxication of power, constantly increasing and constantly growing subtler. Always, at every moment, there will be the thrill of victory, the sensation of trampling on an enemy who is helpless. If you want a picture of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face – for ever.’

Under Pax Xinensis it is likely that the boot of power will be AI-designed footwear crafted from high-end materials and labour-farm leather. These luxury items will be promoted both by Chinese and fellow-traveller influencers and available for online purchase as well as international delivery.

‘Click like and subscribe.’

***

“Do you realise that what you are suggesting is revolution?”

“Of course, it’s revolution. Why not?”

“Because there can’t be a revolution. Our revolution was the last and there can never be another. Everybody knows that.”

“My dear, you’re a mathematician: tell me, which is the last number?”

“But that’s absurd. Numbers are infinite. There can’t be a last one.”

“Then why do you talk about the last revolution?”

George Orwell

Review of “WE” by E.I. Zamyatin

Several years after hearing of its existence, I have at last got my hands on a copy of Zamyatin’s We, which is one of the literary curiosities of this book-burning age. Looking it up in Gleb Struve’s Twenty-Five Years of Soviet Russian Literature, I find its history to have been this:

Zamyatin, who died in Paris in 1937, was a Russian novelist and critic who published a number of books both before and after the Revolution. We was written about 1923, and though it is not about Russia and has no direct connection with contemporary politics—it is a fantasy dealing with the twenty-sixth century AD—it was refused publication on the ground that it was ideologically undesirable. A copy of the manuscript found its way out of the country, and the book has appeared in English, French and Czech translations, but never in Russian. The English translation was published in the United States, and I have never been able to procure a copy: but copies of the French translation (the title is Nous Autres) do exist, and I have at last succeeded in borrowing one. So far as I can judge it is not a book of the first order, but it is certainly an unusual one, and it is astonishing that no English publisher has been enterprising enough to reissue it.

The first thing anyone would notice about We is the fact—never pointed out, I believe—that Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World must be partly derived from it. Both books deal with the rebellion of the primitive human spirit against a rationalised, mechanised, painless world, and both stories are supposed to take place about six hundred years hence. The atmosphere of the two books is similar, and it is roughly speaking about the same kind of society that is being described, though Huxley’s book shows less political awareness and is more influenced by recent biological and psychological theories.

In the twenty-sixth century, in Zamyatin’s vision of it, the inhabitants of Utopia have so completely lost their individuality as to be known only by numbers. They live in glass houses (this was written before television was invented), which enables the political police, known as the “Guardians”, to supervise them more easily. They all wear identical uniforms, and a human being is commonly referred to either as “a number” or “a unif” (uniform). They live on synthetic food, and their usual recreation is to march in fours while the anthem of the Single State is played through loudspeakers. At stated intervals they are allowed for one hour (known as “the sex hour”) to lower the curtains round their glass apartments. There is, of course, no marriage, though sex life does not appear to be completely promiscuous. For purposes of love-making everyone has a sort of ration book of pink tickets, and the partner with whom he spends one of his allotted sex hours signs the counterfoil. The Single State is ruled over by a personage known as The Benefactor, who is annually re-elected by the entire population, the vote being always unanimous. The guiding principle of the State is that happiness and freedom are incompatible. In the Garden of Eden man was happy, but in his folly he demanded freedom and was driven out into the wilderness. Now the Single State has restored his happiness by removing his freedom.

So far the resemblance with Brave New World is striking. But though Zamyatin’s book is less well put together—it has a rather weak and episodic plot which is too complex to summarise—it has a political point which the other lacks. In Huxley’s book the problem of “human nature” is in a sense solved, because it assumes that by pre-natal treatment, drugs and hypnotic suggestion the human organism can be specialised in any way that is desired. A first-rate scientific worker is as easily produced as an Epsilon semi-moron, and in either case the vestiges of primitive instincts, such as maternal feeling or the desire for liberty, are easily dealt with. At the same time no clear reason is given why society should be stratified in the elaborate way it is described. The aim is not economic exploitation, but the desire to bully and dominate does not seem to be a motive either. There is no power hunger, no sadism, no hardness of any kind. Those at the top have no strong motive for staying at the top, and though everyone is happy in a vacuous way, life has become so pointless that it is difficult to believe that such a society could endure.