The Other China

眾說紛紜

This chapter in The Other China consists of two parts. In the first, we offer an idiosyncratic selection of twenty Chinese-language YouTube channels. The second section features ten podcasts recommended by Andrew Methven, creator of Slow Chinese 每週漫聞, a unique guide to modern Chinese that is suited both to beginners and advanced learners of the spoken and written language.

10 Podcasts you should listen to is reproduced with the kind permission of Andrew Methven and Jeremy Goldkorn, editor of The China Project, who first published it.

We also recommend:

- Slow Chinese 每週漫聞 Newsletter

- Phrase of the Week, The China Project (not updated from November 2023)

***

As we have previously noted, The Other China finds expression in myriad ways in a country dominated by a political party that would bend all to its will; it is a China that survived the depredations of the Mao era (1949-1978) and increasingly flourished during the decades of reform from 1978 to 2008. For decades, Hong Kong was a global nexus for The Other China (for more on this, see Hong Kong Apostasy in this journal) and, while doggedly resilient on mainland China, it flourishes too elsewhere. Indeed, The Other China, or what could also be called ‘Other Chinas’, is not limited to the People’s Republic, for it is part of a global culture unique to itself but also with universal aspirations and appeal.

The selection of podcasts and YouTube channels recommended below are part of the cacophony of Chinese voices that persists regardless of the cheerless machinations of the party-state.

***

This material is also included in the series Watching China Watching.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

10 August 2023

***

Update, 7 September 2023

- With Jack Kerouac in Chiang Mai — Planet Speakeasy & The Other China, 在路上 — Chapter Thirty-one of the series Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium, 7 September 2023

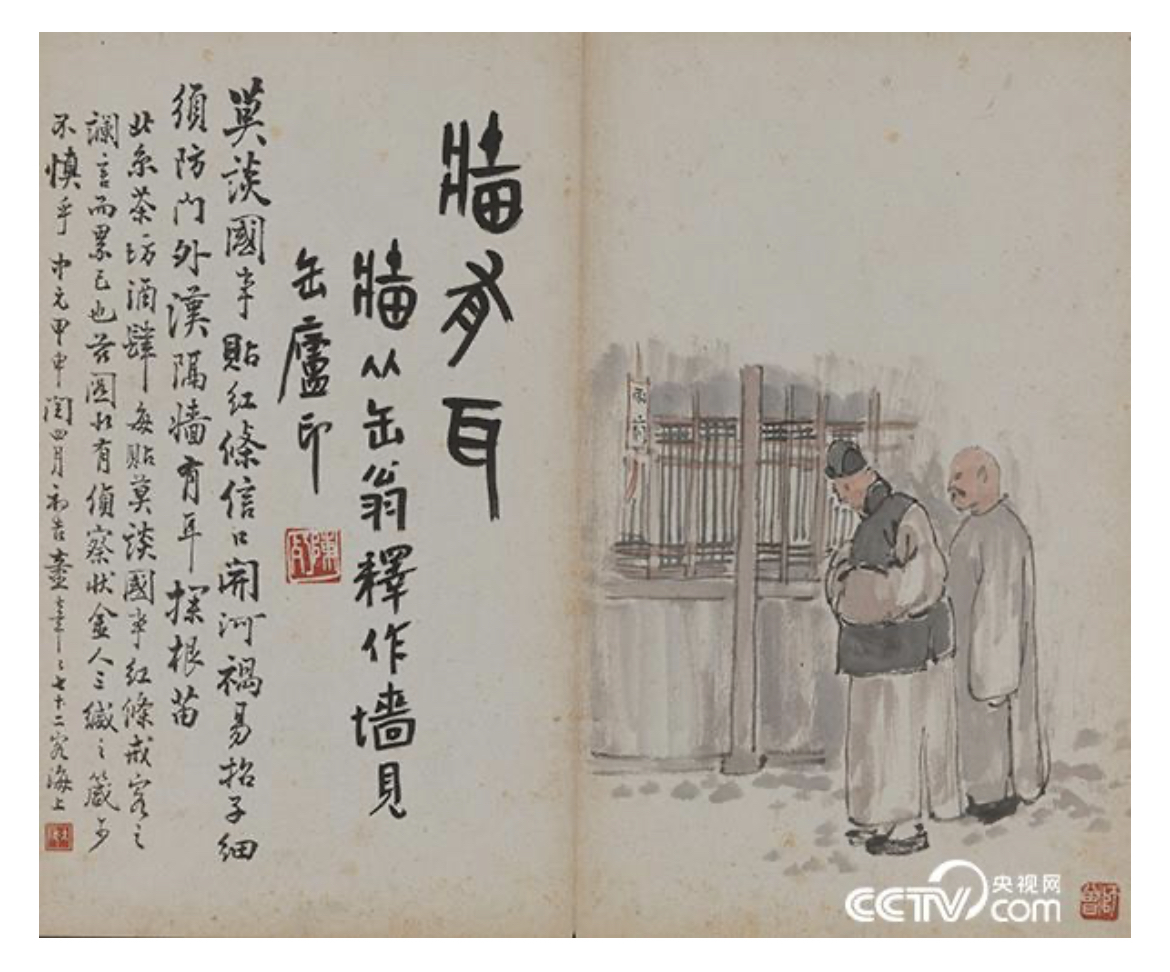

A red alert is posted to warn against discussing politics, for wagging tongues can only court disaster. Always beware of strangers lingering outside: they’re there to eavesdrop on what is being said. 莫談國事貼紅條,信口開河禍易招;仔細須防門外漢,隔牆有耳探根苗。

***

防民之口 甚于防川

It’s Easier to Dam a River Than

to Shut People Up

Geremie R. Barmé

In October 1974, Beijing was an eerily silent city. Apart from the tinkle of bicycle bells, the only sound that penetrated daily life was the bellowing broadcasts spat out from the ubiquitous loudspeakers in workplaces, factories and schools. They crackled to life like clockwork. After a blast of militant music a stentorian voice would provide the surround sound for early morning calisthenics and return at regular intervals — early morning, mid morning, lunchtime, mid afternoon, early evening and again just before bedtime — to bark reports from the Xinhua News Agency. These interventions were supposed to update the populace on ‘the latest fluctuations in ongoing class struggle’ 階級鬥爭的新動向.

Otherwise, in public at least, silence reigned.

As an exchange student in the People’s Republic of China who had studied modern and classical Chinese in Australia, from the moment I arrived in Beijing in October 1974 I was anxious to hear unscripted colloquial Chinese, to speak to people as well as make friends. Apart from our teachers, political commissars and a handful of approved classmates, it was all but impossible to speak with ‘civilian comrades’. Clerks in bookstores, shops, restaurants and department stores were brusque and laconic, at best. Whenever you got on a bus, the muted conversations between passengers died away entirely and the gruff commands shouted out by ticket-sellers were all but impossible to understand. (See Something In The Air — Watching China Watching (XXV), China Heritage, 8 June 2018.)

It wasn’t long before I learned the real-life relevance of the old expression 病從口入,禍從口出 bìng cóng kǒu rù, huò cóng kǒu chū: ‘illness enters the mouth, disaster flows from it’.

Mao Zedong died on 9 September 1976. The following month, a military coup saw the fall of his radical supporters and, within days, the floodgates of long suppressed speech in China began to creak open. I experienced it first hand when some of our teachers tentatively started speaking to us, sotto voce of course, about what they thought was going on. Thankfully, not long after, I was introduced to members of The Layabouts’ Lodge 二流堂 in Beijing and my Chinese life changed forever. Now I would learn the truth of another old saying: 聽君一席話,勝讀十年書… ‘I can learn more from talking with you than I could after ten years of study’.

Work in Hong Kong and frequent lengthy trips to Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou, introduced me to a world of lively discussion, debate and disagreement. Although Deng Xiaoping and his comrades refused to exonerate in full all of the victims of the Hundred Flowers Campaign, and the devastating repression that followed in its wake, China once more saw dozens of schools of voice contend. Apart from the Communist party-state they were, of course, all politically impotent, but they flourished to a greater or lesser extent for nearly four decades.

My work with the oral historians Sang Ye, Zhang Xinxin and Dai Qing helped me appreciate the bristling soundscape of post-Mao China and its historical antecedents. Other projects — my own career as a writer of Chinese essays in the Hong Kong press, translation work focussed on contemporary thought and the arts, and doctoral research that was focussed on the suppressed tradition of non-partisan culture — allowed me to listen to and learn from a world that was not dominated by Official China. In a myriad of ways, I was in conversation with The Other China.

In October 1986, at the height of the Pax Hu Yaobang, a time of relatively benign cultural and political rule in China, the state-controlled Chinese Writers’ Association organised an international symposium on contemporary literature at Jinshan, the steel town outside Shanghai. Hosted by Wang Meng, a prominent novelist and the recently appointed minister of culture, the gathering was a canny effort at arts public relations. Many of the international participants were leading translators of Chinese letters and Sinologists; one was even a member of the Nobel Academy. Some of China’s most popular and faddish writers — men and women who had risen to prominence as pathbreaking novelists, poets, and essayists in the 1980s — also were present, although there were a few notable absences. Over the ensuing days, much of the discussion centered on a common obsession on the mainland: the Nobel Prize for literature, that international stamp of cultural approval. Amid the lobbying of the Nobel academician, there also were recriminations from among disgruntled local participants that the Chinese arts — which, they contended, had come of age in the decade since the end of the Cultural Revolution in 1976 — had been badly served by the academics and professionals who translated mainland literature into Western languages. If only Sinologues could do justice to the cutting-edge Chinese works through their translations and critiques, it was argued, then mainland culture would be sure to find the international recognition it so richly deserved.

In their speeches, many of my overseas colleagues concentrated on the literary innovations that had led to the appeal of post-Maoist literature to an increasingly sophisticated and demanding audience in China. For my part, I chose to reflect on the revival of individualistic prose, in particular the casual essay, from the late 1970s. This was a development that showed how more intimate and personal concerns in literature were being overwhelmed by newly unleashed market forces and literary sensationalism. Having just spent a year in Hong Kong working on a volume of contemporary Chinese writing (Seeds of Fire: Chinese voices of conscience), I felt that the publishing furor and writing fever that had followed in the train of political relaxation and the recent commercialization of the arts had led, among other things, to a wave of national graphomania. In my concluding remarks, I quoted a passage from Milan Kundera, a writer who was then relatively unknown in China (although after 1989, much of his work was published in translation, and he become something of a literary paragon, if not a cliché):

The irresistible proliferation of graphomania among politicians, taxi drivers, childbearers, lovers, murderers, thieves, prostitutes, officials, doctors, and patients shows me that everyone without exception bears a potential writer within them, so that the entire human species has good reason to go down into the streets and shout: “We are all writers!”

For everyone is pained by the thought of disappearing, unheard and unseen, into an indifferent universe, and because of that everyone wants, while there is still time, to turn himself into a universe of words.

One morning (and it will be soon), when everyone wakes up as a writer, the age of universal deafness and incomprehension will have arrived.

When my speech was reprinted in Literary Gazette (Wenyi bao) [文藝報], the main official cultural newspaper in Beijing at the end of 1986, the Kundera quotation was inexplicably deleted.

— these paragraphs, including the quotation from Kundera, are taken from the introduction to my book

In the Red, on contemporary Chinese culture, New York, 1999

For all of the cacophony, and the boundless excitement of being able to hear a raucous concert of voices, even then the ‘universal deafness and incomprehension’ about which Milan Kundera had warned, seemed to be on the horizon. In the ‘universe of words’ that characterises the Xi Jinping era, a new silence also reigns.

***

China Heritage was launched online in December 2016. At the time, I quoted a famous line from the Annals of Tacitus, ‘Solitudinem faciunt, pacem appellant’, which Lord Byron translated as:

Mark where his carnage and his conquests cease!

He makes a solitude, and calls it — peace.

The Xi Jinping era has, above all, been characterised by an increased policing both of public speech and private expression. The term often used to describe the quelling of China and its voluble population is 被禁言 bèi jìn yán, ‘to be silenced’.

China Heritage, however, along with numerous other publications and sources has demonstrated that China’s restless, voluble and thoughtful world continues to express itself in irrepressible and irascible ways. (These paragraphs are taken from Five Years Ago Today — Xu Zhangrun’s Sublime Madness in the Soul, 24 July 2023.)

***

***

Twenty YouTube channels you should watch

Geremie R. Barmé

The expression 聆聽 lìng tīng means to listen attentively. Here I use 聆 lìng as a shorthand for the practice of paying attention to diverse voices and to listen — to really listen — to what they have to say. To do so is not for the sake of some utilitarian purpose, careerist aim, or short term advantage, but so as to learn and to seek to understand. For those who wish to hear and know how to listen, China is far from silent. The droning monotone of Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium can’t drown out the roiling cacophony of an unquiet reality.

Here we introduce a selection of twenty podcasts that offer, in sum, a fusion of politics, news and entertainment. Like the old tea houses which were revived for a short time after Mao and silenced (or rather forced to conform) under Deng, these podcasts offer a rich, rambling and diverting array of approaches to and views of contemporary China. Some are produced in China and they artfully skirt around the increasingly egregious restrictions imposed on online publishing. Others issue from Japan, North America and Taiwan. For them, the byword is that 百無禁忌 bǎi wú jìn jì, anything goes and nothing is taboo.

However, YouTube is a commercial operation and, ultimately, the trade involves ‘attracting eyeballs’ 博眼球 and carving out a niche in the ‘attention economy’ 注意力經濟. Despite the relaxed style of many of these creators, as we eavesdrop in on the monologues we are mindful that of the complex political and economic forces lurking at every turn.

Serious people may well dismiss these yammering tongues and readers would be well advised to revisit our old essay Rumour — a Pipe Blown by Surmises, Jealousies, Conjectures and read Eating Watermelon with Wu Guoguang — a summer seminar in China Watching, The China Project, 1 August 2023. The mainstream media in China has long been given to ‘stuffing the ears of men with false reports’ and there is a universal zest for truth, or at least making sense of things.

Some of the YouTube channels featured below are converted into MP3 files and shared anonymously by WeChat groups in China (although I am no longer on WeChat, I sometimes receive copies of such files from friends). The surveillance state of Chinese socialist-capitalism engenders in its turn the tireless surveillance of its subjects. While conspiracy theories flourish with abandon internationally, in China, where the state is the main source of conspiracy thinking, unofficial conjecture is a key weapon in the arsenal of the powerless. As it may be deadly to ‘speak truth to power’, people still do their best to whisper their speculations behind power’s back.

***

The following Chinese-language YouTube channels are arranged by the alphabetical order of the Romanised names of their presenters or titles. They are selected on the basis of my own listening/ viewing habits, for which I make no apology:

- Beitong北同 — a member of LGBT+ community offers reflections on life, relationships and family in two Chinese cities

- Cui Yongnian 崔永元 — a former TV star who retired from the official media to teach and offer his insightful (and often acerbic) commentary on contemporary issues (his bête noire is Sima Nan, see below)

- Dou Wentao 竇文濤 — a popular TV presenter and conversationalist known for knowing the limits. He perfected his artfulness as an onscreen personality for Phoenix TV in Hong Kong. His shows include《鏘鏘行天下》(ongoing),《鏘鏘三人行》(discontinued) and《圓桌派》(discontinued). His work, along with the efforts of his interlocutors, offers a glimpse of a China that is always on the cusp of becoming a reality

- Erye (Tankman) 《二爺故事》 — the online persona of Deng Haiyan 鄧海燕, a former policeman and self-identified rebel or ‘traitor’ 反賊 fǎn zéi who comments on history, politics and China’s culture of lies from his base in the United States. Listen to Erye’s conversation with Wang Zhi’an: 專訪“二大爺”鄧海燕, 4 August 2023

- Fang Zhuan 方磚《方的言》— this besuited bald commentator claims to offer original and insightful impartiality. His tag line is 方的言:’方外之人,隨心之言’. Or, as the description of his channel puts it: ‘這裡有時事熱評,有婚姻情感,有育兒心得,也有信仰見解。無論是嬉笑怒罵還是直言不諱,都是100%原創新作。’

- GouGe 狗哥 《狗哥狗哥DogChinaShow》— with the help of his canine companion this YouTuber reflects on newsworthy stories and ongoing absurdities

- Liang Hongda 梁宏達 《老梁》— a master storyteller enthralls with tales from the past and reflections on the present

- Mei Liu’r 《梅六兒-侃大山》 — this multiloquous Beijing raconteur engages with listeners as though he is shooting the breeze over a few beers, or in the company of a bottle of Erguotou 二鍋頭

- Old Peking Teahouse 老北京茶館 —— 時政相聲 — featuring the comic dialogues of the hosts Li Zheng 李正 and Liu Zhuo 劉卓. They describe their channel as follows: 天下大勢,微妙互動。幽默段子小輕鬆,盡在老北京!有料有幽默、有梗有真情;把一個紛亂當下,演說成大笑劇情。清茶一杯喜相逢,不見不散老北京!

- Polishing the Turd 《朽木可雕》 — well-honed satirical monologues offering a sardonic view of China’s topsy-turvy realities. As channel self-description reads: 人生枯燥,不如揚把沙子加點料。一個不太嚴肅的媒體頻道,喜歡我們的節目歡迎您常來,不喜歡我們的節目您就多看幾遍,看到喜歡為止 。

- Tang Shizeng 唐師曾 《唐和尚Peaceduck Tang》— a retired veteran reporter shares accounts of his everyday life at Houhai in Beijing and reflections on his storied past. For an explanation of Tang’s approach to vlogging, see Five Years Ago Today, 24 July 2023

- Wang Yajun 王歪嘴 — a comic commentator, gourmand and merchandise marketer with a particular spin on current events

- Wang Zhi’an 王志安《王局拍案》 — a former disaffected media personality provides insightful commentary on contemporary politics and mainland life from a safe haven in Japan. For a revealing interview with Wang Zhi’an conducted by Li Yuan 袁莉, see 王志安:央視、審查和“大外宣”,2023年1月7日

- Wenzhao 《文昭談古論今》 — notwithstanding his rumoured connection with Falungong, this presenter engages the listener with carefully crafted monologues on the news of the day and reflections on historical precedents

- Wuyue Sanren 五嶽散人 — based in Kyoto, Japan, this Beijing native uses his channel to ‘say whatever the fuck I like. … if what I have to say resonates with others, that’s all well and good. If not, why should I care?’ (See: I’d rather support stray cats in Japan than donate a single penny to China’s disaster relief efforts, 8 August 2023.)

- Yang Jinlin 楊錦麟 《老楊到處說》 — a veteran journalist and reporter for Phoenix TV who dissects the news of the day in well-wrought essays the texts of which are included with each episode

- Yuan Tengfei 袁騰飛 — a former high-school teacher known for his historical insights and voluble wit offers valuable lessons on both the past and the present

- Xu Zhiyuan 許知遠 《十三邀》 — a canny writer who navigates the censorship-rich environment of Beijing to produce a balletic series of one-on-one conversations with leading public figures (for Xu’s reflections on his artful accommodation with the status quo, see Elephants & Anacondas, 17 June 2017).

To this raucous mix, we would add two notorious Beijing-based blackguards, both of whom wrap themselves in the blood-red of the Chinese flag. They reflect the bleak obverse of The Other China:

- Hu Xijin 胡錫進《胡侃》— a voluble sophist who rose to fame as the editor of The Global Times, the preeminent model for party-state yellow journalism; and,

- Sima Nan 司馬南《司馬南頻道》— a noxious but engaging ultra-nationalistic influencer

Apart from the twenty YouTube channels mentioned in the above, we also recommend the archive of EYECTV 眼睛中央電視 produced in Taiwan, a double-entendre-laden comic take on the news in both Chinas (see, for example, October 1 & October 10 — Two Chinas, Whose Fatherland?, 1 October 2022). Wen Tzu-yu (溫子渝, 1994-), a Taiwanese YouTuber known by the moniker 八炯 bā jiǒng who is based in Hualien, continues the irreverent tradition on his channel 攝徒日記Fun TV. Wen takes particular delight in goading ‘Little Pinks’ 小粉紅. Other media commentators relevant for students of contemporary Chinese society, politics, the economy and culture include Lizzi C. Lee 李其, Ho Pin 何頻 《想點就點》 and Bei Ming 北明, a journalist at Radio Free Asia who was active from 1997 t0 2022, as well as Manya Koetse’s What’s on Weibo. For some apolitical diversion, two go-two sites focus on Old Peking (see 北京瑞姐) and the cringe-worthy and vapid lives of Crazy Rich Beijingers (see 田田小阿姨).

In conclusion, we would note the competition for attention among YouTube channels hosted by international Chinese-speakers is also considerable. It can be entertaining and occasionally even informative. Pro-PRC foreign influencers, mocked as ‘Foreign 50 Centers’ 洋五毛, churn out clunky propaganda in which they parrot Beijing’s ‘China Story’ talking points, as well as ‘China-is-oh-so-normal’ travelogues. They are derided by their more independent rivals as publicity shills for the party-state, or 大外宣 dà wài xuān. The rivalry between ‘Afu’ Thomas阿福 (Thomas Derksen) and ‘Lao Lei’ 老雷 (Christoph Rehage), two German vloggers, illustrates the signature style and vitriol of this rancorous niche market. Meanwhile, the songs of Teacher Grey 格雷老師 which float above the fray have proved to be popular (see Hands off Snakey — Teacher Grey’s Chinese Lessons, 16 March 2023) while the indefatigable LeLe Farley 樂樂法利 (aka ‘MC樂兒’) jokes, raps and dances around them all on his burlesque YouTube channel. And so it is that a Manichaean clash between the Shills 洋五毛 and their nemeses 洋反賊 rages online around China’s Great Firewall. For those who retain a vestigial belief in human progress, the good news is that maybe, just maybe, by the time Xi Jinping’s fourth term in office comes around a Sino-Occidental avatar of Randy Rainbow will be spawned.

***

Additional Recommendations

Among numerous non-Beijing-affiliated news outlets in Chinese and English, including Radio Free Asia, RFI, BBC, DW and VOA, we also recommend, in alphabetical order, the following websites and podcasts:

***

Chinese-language news sites recommended by Andrew Methven:

1. 163 (網易)

2. 36Kr (36氪)

2. The Initium (端傳媒)

4. Lianhe Zaobao (聯合早報)

5. China Digital Times (中國數字時代)

And, our own additions:

Ten Chinese-language podcasts you should listen to

Andrew Methven

The China Project, 17 July 2023

I run a newsletter about learning Chinese, so I’m always on the lookout for ways to stay up to date on colloquial language, the slang and phrases used in daily life. One of the most helpful strategies I’ve found is to listen to Chinese-language podcasts — but I’m not talking about those designed specifically for language learners. Podcasts aimed at a Chinese audience are a great source of “real life” content: They bring authentic conversations in China to you on topics that are being talked about inside the country right now.

Immersing yourself in podcasts about China is a great way to learn about contemporary society as well. But there are so many to choose from. Where do you begin?

I have you covered. I’ve spent hours searching for the best Chinese-language podcasts, and put together this list of 10 favorites. The best part? These do not have to strictly be for the language learner. I think everyone will find something in this list to enjoy.

The criteria I used to put this together:

- The language is authentic: All these podcasts are designed for a native Chinese audience.

- Conversational: Some pods are interviews, others are conversations between one, two, or three presenters.

- Relevant to contemporary life: All podcasts in this list reflect elements of life in China, including discussions about gender, work, life, family, and business.

- Not state-owned: None of these podcasts are state-sponsored or produced. They reflect the views of real people living in China, or Chinese people observing from abroad.

- Available on mainstream podcasting platforms: All pods are available on Apple and Spotify, as well as major Chinese podcasting platforms, such as Ximalaya.

This list isn’t definitive; it is a small selection out of the hundreds of great Chinese podcasts out there. If your favorite is missing, please let me know. (If you enjoy this list, check out my weekly newsletter about Chinese-language trends, and of course follow my weekly column for The China Project, Phrase of the Week.)

***

1. Story FM | 故事FM gùshì FM

How it describes itself: “Here, you can use your voice to tell your story.”

Hosted by Kòu Àizhé 寇爱哲, a self-described collector of stories, Story FM is about stories from all walks of life in China. Shows are normally around 40 minutes long. Kou gives a short introduction, and then it’s handed over to the guest to narrate their story.

Our take: With over 750 episodes in the archive, Story FM is a great resource for exposure to real language from everyday people in China about interesting, engaging, and difficult topics. It can be challenging as a language learner because some speakers have heavy accents, but the show is slickly produced, and you’ll usually be able to settle into the rhythms of the storytelling.

Also see:

2. Cyber Pink | 疲惫娇娃 pí bèi jiāo wá

How it describes itself: “A pan-cultural podcast that takes conversations from the dinner table to the depths of the universe, using female voices to expand participation and imagination of the world.”

The format is conversations between the host and usually two to four guest speakers about a wide range of topics, from popular movies or TV shows to relationships, family, and lifestyle. The host is based in the U.S., so topics often have a U.S. focus. Although the blurb suggests it features “women’s voices,” there is normally a mix of men and women guests on the show.

Our take: Great content about current topics, in natural, conversational language. Some themes are familiar to a Western audience (such as movies or TV shows), but they are discussed from a Chinese perspective. Show notes are in Chinese and English, which is helpful if you want to read into the context before listening. Shows are quite long (normally more than an hour), so you might want to split into shorter chunks. You can follow the show on Twitter @CyberPinkFM.

3. Stochastic Volatility| 随机波动 suíjī bōdòng

How it describes itself: “A pan-cultural podcast initiated by three female media professionals, updated every Wednesday at noon.”

Presenters are Fù Shìyě 傅适野, Zhāng Zhīqí 张之琪, and Lěng Jiànguó 冷建国, who are based in China. The format is a conversation on a topic about life in China, usually focused on younger themes such as graduating from university, finding work, fitness and health, and so on. There’s normally a hook, such as a movie the hosts have watched, a book they’ve read, or something in the news. Shows are around an hour long, and there are nearly 200 episodes in the archive.

Our take: Good for listening in on conversations that are probably happening in China every day. It’s helpful that it’s the same three people in each show, so you can get used to how they speak. The downside to this is there is less variety of voices. Three speakers is a good number to help train your ear to keep up with conversations. Anything over three voices can be too challenging. Show notes are helpful but only in Chinese, so a bit more of a challenge.

4. Other Waves | 别的电波 biéde diànbō

How it describes itself: “In the face of boring reality, let’s talk about something else! We are a talk show based on urban youth culture and discussions about youth pop culture.”

The two main presenters are Zhí Lìyuán 直立猿 and Hán Duì 韩队, who are joined by two more members of the production team for each show. The show is produced by a media company, BIEDE别的, based in Beijing, whose stated aim is to provide engaging and interesting content for young people in China. There is a slightly more commercial feel to the content, such as shows being sponsored by Chinese brands.

Our take: Shows are around two hours long. Conversations are free-flowing, normally with four people engaged in lively discussions. Presenters have strong northern accents. Listening to this show takes me back to hard-to-hear conversations in rowdy bars in Beijing. The website is easy to navigate, but show notes are very brief.

5. Bigger Than Us | 声东击西 shēng dōng jī xī

How it describes itself: “The world is big, but people are limited by everyday life and social media. So let us, as reporters, help you open some unexpected windows, access different information, and stimulate different thinking. Here, we talk to all kinds of interesting and informative professionals who can bring inspiration, and there will be mysterious guests appearing from time to time.”

The hosts are Xú Tāo 徐涛 and Zhāng Jīng 张晶, who are seasoned Chinese media professionals. The format is informal interviews on a wide range of current affairs with one or two guest speakers. Recent shows range from discussions about sci-fi to interviewing a Chinese reporter who was in Ukraine covering the war.

Our take: The high-quality production combined with an informal and chatty style make this an easy listen. Conversations do get lively, so it can be a challenge to keep up. The variety of different guests for each show is great exposure to different speaking styles.

6. Out of Time | 不合时宜 bùhé shíyí

How it describes itself: “Out of Time is a podcast co-created by three (former) media people living in different time zones.”

The show’s title, 不合时宜, is an idiom meaning “inappropriate, out of place, or misplaced.” Here, it refers to the show hosts being in different time zones. Conversations tend to revolve around themes of gender and topics linked to life as a young woman in China. Hosts are Ruò Hán 若含, Mèng Cháng 孟常, and Wáng Qìng 王磬. Shows are normally presented by two of the three hosts, with a guest speaker, in a conversational interview style.

Our take: Shows offer a mix of young male (Meng) and female (Ruo and Wang) voices. Topics are engaging and give a good spectrum of what young people are talking about in China today. Conversations tend to be more controlled than some of the other podcasts in this list, so are easier to follow. Show notes are comprehensive, production is high quality.

7. Bumingbai Pod | 不明白播客 bù míngbái bōkè

How it describes itself: “The most interesting conversations in China right now are happening in private. This podcast hopes to share interesting conversations with Chinese listeners around the world, and to shine a little light and warmth in this dark and chaotic era. This podcast is a personal project of several professional journalists. The name ‘Don’t Understand’ is because there are so many unexplainable things worth exploring in this magical country.”

Probably the best known internationally of the podcasts in this list, the creator is New York Times journalist Li Yuan (袁莉 Yuán Lì). The show covers a wide range of topics, often focusing on things that are censored in China or more sensitive political topics. It’s an interview format with Yuan and one other guest, ranging from well-known experts to everyday people. The latter are often speaking under anonymity. There’s also a good range of topics discussed, with recent episodes featuring discussions on the invisible employment ceiling at 35, young people in China who cannot find work, and the connection between food, politics, geopolitics, and identity in Taiwan.

Our take: This is a great show for seasoned China-watchers, exploring topics that are relevant to China but often with an international or geopolitical angle. Conversations offer deep insights. The production is high quality. Interviews sometimes take place in public spaces, so sound quality can be a challenge, and if interviewees are speaking anonymously, their voices are distorted, which can be distracting. But overall, the content is fantastic and engaging.

8. News Sauerkraut Restaurant | 新闻酸菜馆 xīnwén suāncài guǎn

How it describes itself: “News Sauerkraut Restaurant is an internet radio program, independent new media.”

Hosted by two experienced Chinese journalists, Wáng Zhǎngguì 王掌柜 and Dīng Dīng 丁丁, this weekly show explores news topics being discussed in China each week. It’s mostly China-based news, but sometimes the hosts will discuss international stories that are trending in China. Recent episodes include discussions on the Titan submarine implosion, depression among young people in China’s cities, and Coco Lee’s suicide. Shows are around an hour long.

Our take: News Sauerkraut Restaurant is probably the podcast of choice for listening in to conversations about current affairs and news in China, with two hosts with very different speaking styles. Overall, an excellent listen.

9. Lively Morning Coffee | 声动早咖啡 shēng dòng zǎo kā fēi

How it describes itself: “A 15-minute morning ritual to effortlessly synchronize everyday life with the business world. This is an early-morning podcast released every weekday morning, bringing you a light interpretation of business technology closely related to daily life, and helping start a new day full of energy.”

Hosted by Meng Yi, supported by Zelin and Yifan, this show presents highly produced business news from around the world in bite-sized portions (15 minutes).

Our take: If you’re looking for quick takes delivered in standard Mandarin that are livelier and more engaging than a CCTV news broadcast, then this is for you. Each episode is 15 minutes, which means they can be consumed in one sitting. The news-like structure means the shows are easier to follow, but offer little exposure to “conversational” language.

10. One Call Away | 打个电话给你 dǎ gè diàn huà gěi nǐ

How it describes itself: “We are Wendy and Iphie, typical young women currently living in Hong Kong and Beijing. One is engaged in and addicted to movies, the other is passionate about anthropology and social innovation.”

The format of the show is a phone conversation between the two hosts, Iphie and Wendy (one in Beijing, one in Hong Kong). Conversations are free-flowing and engaging, covering what’s going on in the lives of the two hosts. Recent episodes have revolved around a wide range of topics, including empathy, experiences on overseas holidays, and sexual harassment. Discussions are often linked to news events.

Our take: This is excellent content if you’re looking for more informal conversational language. The phone call format makes it feel more personal. Both hosts have clear pronunciation, and their conversations flow freely without cutting across each other. They combine current affairs and news with personal experiences and stories.

That’s my current top 10 favorite native Chinese-language podcasts. I’m always discovering new shows, so if you want to keep up to date with the latest language trends in China, and listen to the latest Chinese-language podcasts, sign up for my free weekly newsletter.

***

Source:

- Andrew Methven, 10 Chinese-language podcasts you should listen to, The China Project, 17 July 2023