The Tower of Reading

採菊東籬下

悠然見南山

Tao Yuanming (陶淵明 or 陶潛, ?365-427 CE), recluse, poet and cultural paragon, is one of the most accessible writers in the Chinese tradition. We take advantage of the fact that Tao features in three chapters of Zhong Shuhe’s Tower of Reading to introduce readers to his work, his legendary reputation and the influence he had on other writers.

In the first of three chapters, we feature a note that Tao Yuanming addressed to his sons. With the help of Duncan Campell, the historian and literary translator who is a collaborator in this project, we also touch on the influence that Tao Yuanming had on Bo Juyi, one of the greatest poets of the Tang dynasty, an era of great poets. The other two chapters highlight Tao’s standing in the eyes of Su Dongpo and Lu You, two major literati of the Song dynasty.

First, we offer four perspectives on Tao Yuanming before highlighting the note that he wrote to his sons, one that, in Zhong Shuhe’s opinion, reflects his humanistic spirit. Our focus then turns to ‘Drinking Wine’, a famous poem that contains a famous line — 採菊東籬下,悠然見南山 ‘gathering chrysanthemums by the eastern fence, I catch sight of South Mountain’. This line is both the rubric of this selection from The Tower of Reading and a cue to introduce readers to some other works by Tao that are familiar to students of Chinese culture.

We continue with an effusive portrait of Tao Yuanming written by Lin Yutang, a modern writer and editor who advocated a home-grown tradition of humanistic individuality. Lin’s contemporary, the artist, essayist and translator Feng Zikai who embodied the spirit of Tao Yuanming, guides our literary sojourn to a conclusion.

[Note: For more on the search for, and invention of, a Chinese tradition of individualism and idiosyncrasy, see On the Spur of the Moment and Inspiration & Taste — considering ‘On the Spur of the Moment’, also in The Tower of Reading.]

***

Contents

(click on a section title to scroll down)

- Preface

- Four Perspectives on Tao Yuanming

- Tao Yuanming Writes to his Feckless Sons

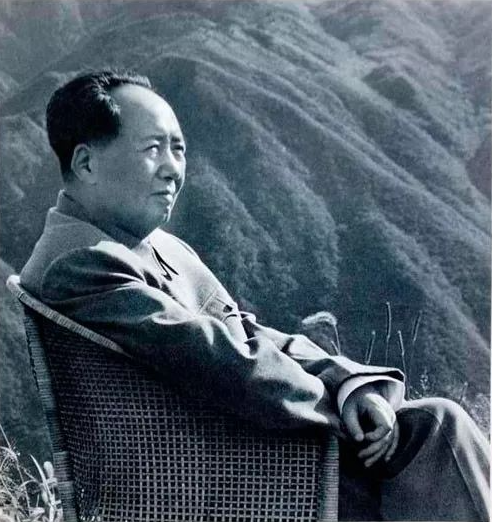

- Mao Zedong Ascends Southern Mountain

- One Poem, Four Translations and a Comment

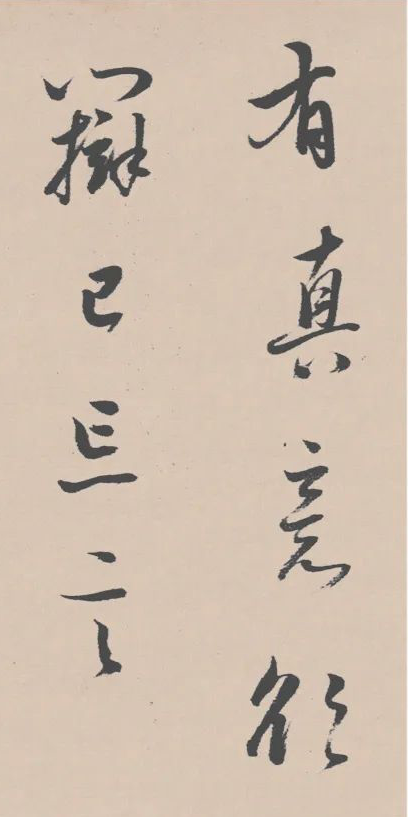

- A Calligraphic Interpretation of ‘Drinking Wine’

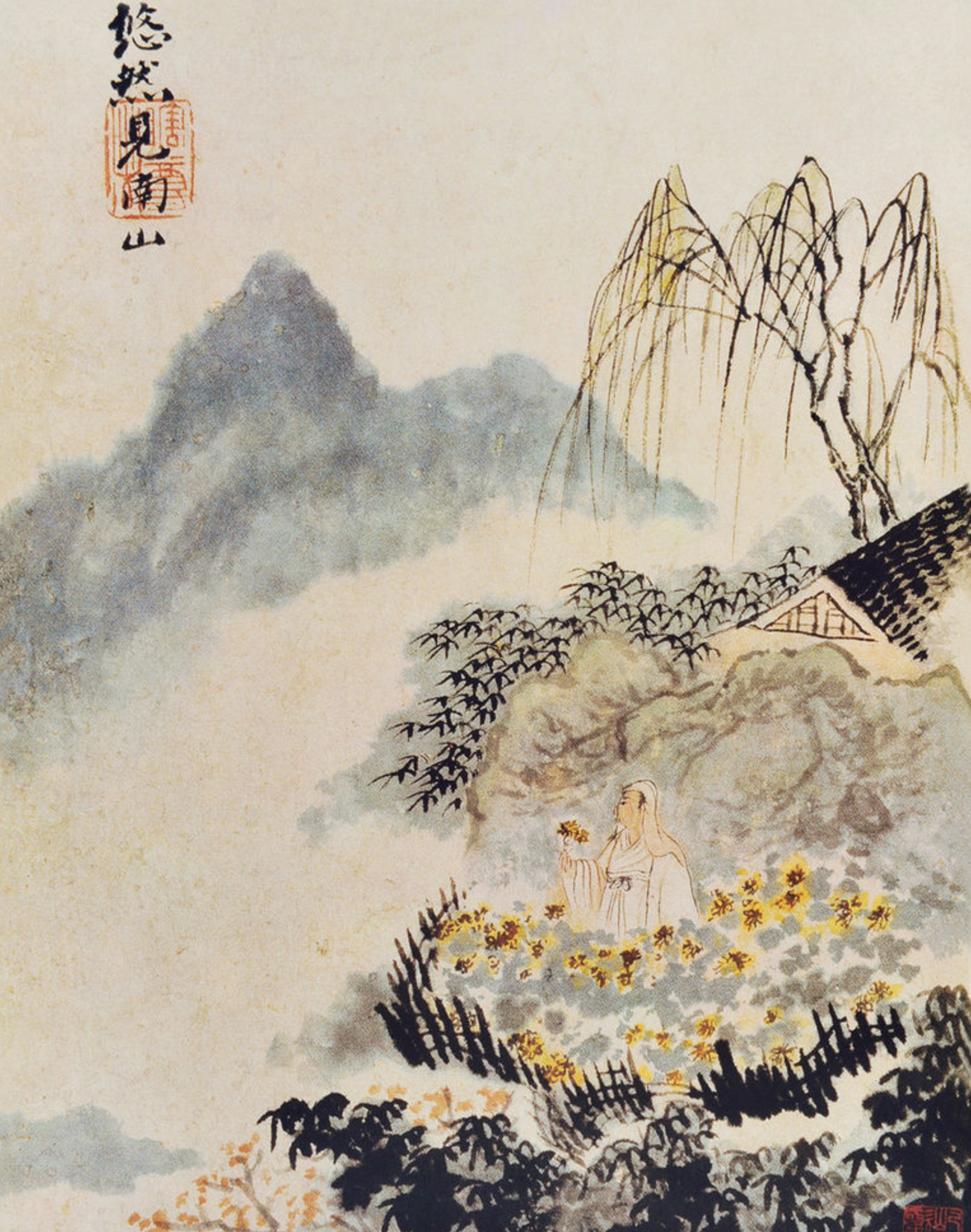

- Chrysanthemums in the Eastern Garden

- Bo Juyi on a Meeting of Minds

- Lin Yutang on the Lover of Life

Three Essential Works by Tao Yuanming:

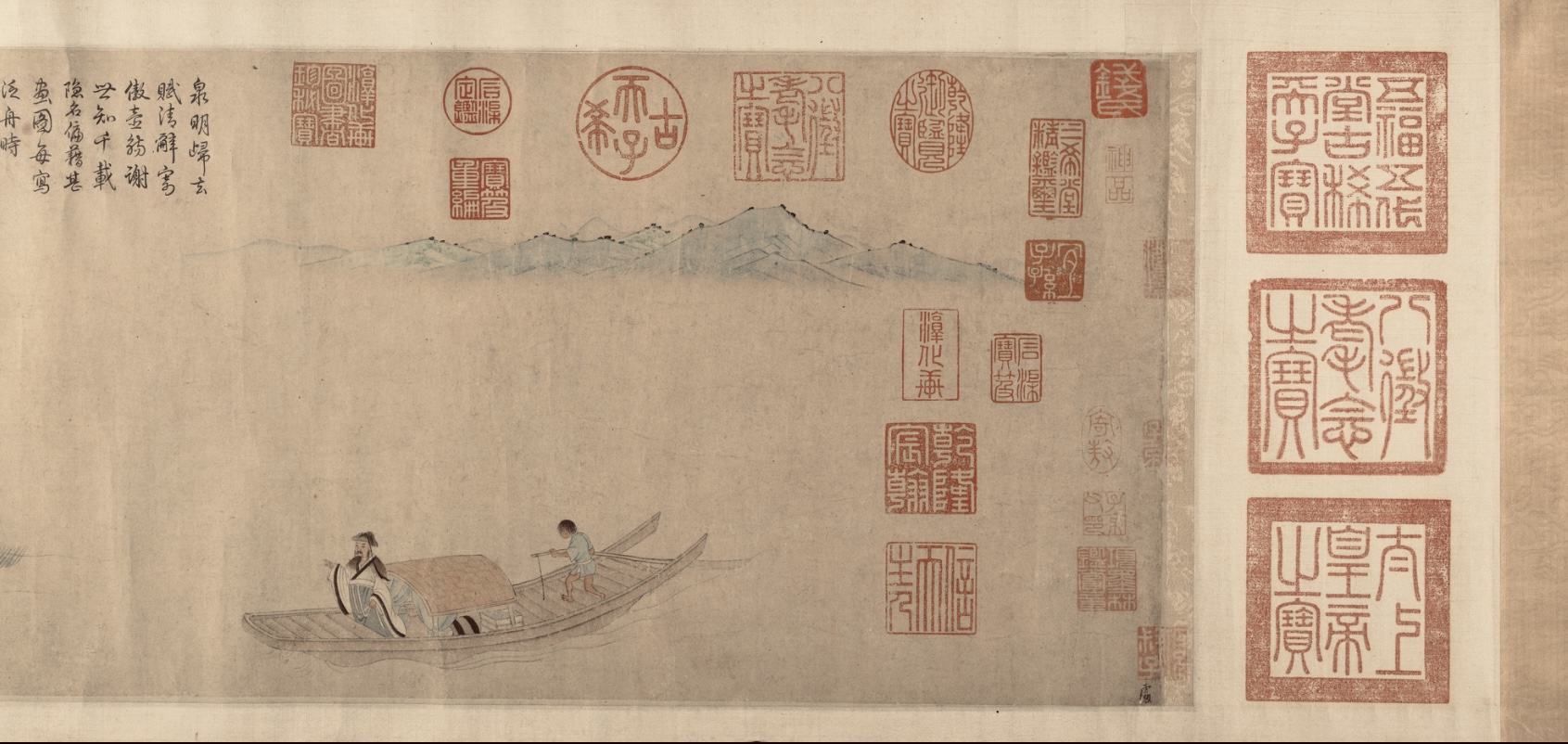

An Artistic Exile

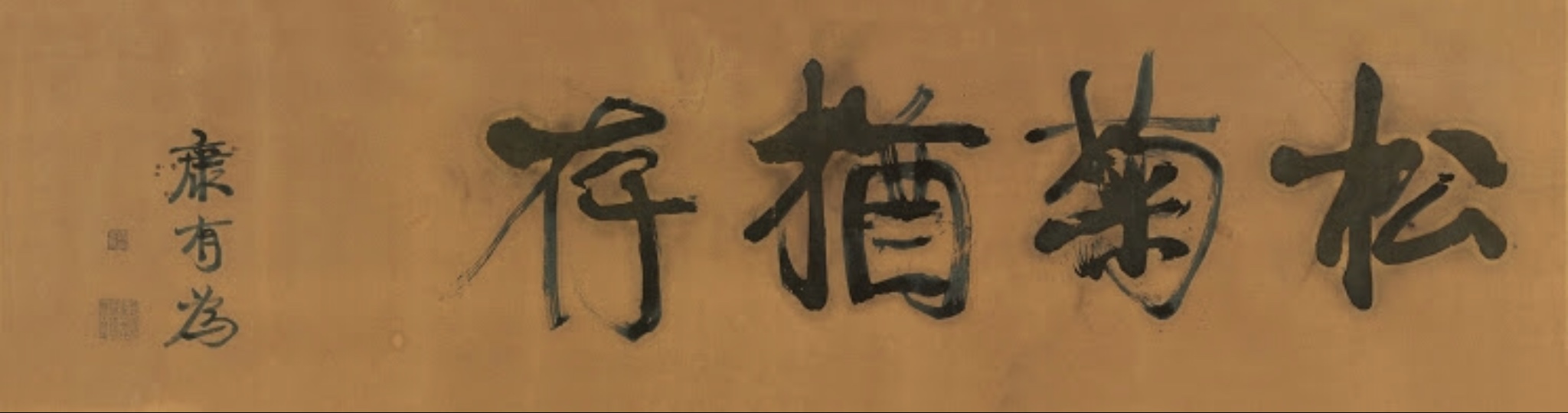

Calligraphy by Kang Youwei

***

As we noted in Introducing The Tower of Reading, be it in approach, temper or style, Zhong Shuhe’s work chimes with our own advocacy of New Sinology. Furthermore, taken as a whole, The Tower of Reading is also something of a commentary on China, one written by a littérateur imbued both with the ethos of China’s dual enlightenments (1917-1927 and 1977-1989) and the long tradition of what Republican-era writers like Zhou Zuoren and Lin Yutang championed as Chinese humanism. Through his translations, Zhong Shuhe helps readers appreciate pithy original texts which, more often than not, are in a terse telegraphic style that can easily elude the modern reader. In his appended commentaries Zhong reflects on a range of issues, drawing on life lessons while addressing a future that, as he suggests in asides ‘hidden between the lines’, may possibly be less ideologically hidebound than the present.

***

As ever I am grateful to Duncan Campbell for his generous contributions to The Tower of Reading. Duncan’s translations of Su Dongpo and Lu You’s comments on Tao Yuanming encouraged me to link them to Zhong Shuhe’s reflections on the abiding significance of the humanity of the recluse-poet. Thanks also to Reader #1 for reading the draft of this chapter and catching typos and various other infelicities.

This chapter in The Tower of Reading may best be enjoyed in concert with Substance, Shadow and Spirit, a poem by Tao Yuanming featured in Intersecting with Eternity.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

22 July 2024

***

Tao Yuanming in China Heritage

- Ninth of the Ninth 重陽 Double Brightness, 28 October 2017

- ‘I’d like to ride the wind to fly home’, by Wu Fei, 5 January 2024

- Inspiration & Taste — considering ‘On the Spur of the Moment’, 14 April 2024

Su Shi in China Heritage

- The True Face of Mount Lu, 1 January 2022

- ‘Streams Descending Turn to Trees that Climb’ — five years of China Heritage, 16 December 2021

Lu You in China Heritage

- Lu You Visits Jinling, China Heritage Annual 2017: Nanking

On Tao Yuanming, Reclusion & Reputation

- Susan E. Nelson, Catching Sight of South Mountain: Tao Yuanming, Mount Lu, and the Iconographies of Escape, Archives of Asian Art, vol.52 (2000/2001): 11-43

- John Minford and Joseph M. Lau, Classical Chinese Literature: An Anthology of Translations, Volume I: From Antiquity to the Tang Dynasty, New York: Columbia University Press, 2000

- Susan E. Nelson, Revisiting the Eastern Fence: Tao Qian’s Chrysanthemums, Art Bulletin, vol.83, no.3 (September 2001): 437-460

- Xiaofei Tian, Tao Yuanming and Manuscript Culture: The Record of a Dusty Table, Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press, 2005

- Wendy Swartz, Reading Tao Yuanming: Shifting Paradigms of Historical Reception (427–1900), Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center, 2008

- Peter C. Sturman and Susan S. Tai, eds, The Artful Recluse: Painting, Poetry, and Politics in Seventeenth-Century China, Santa Barbara Museum of Art, 2013

- A.R. Davis, T’ao Yuan-ming: His works and their meaning, 2 vols, Hong Kong, 1983

- Aat Vervoorn, Men of the Cliffs and Caves: The Development of the Chinese Eremitic Tradition to the End of the Han Dynasty, Hong Kong: Chinese University Press, 1993

- Alan J. Berkowitz, Patterns of Disengagement: The Practice and Portrayal of Reclusion in Early Medieval China, Stanford University Press, 2000

Preface

A recurring theme in Zhong Shuhe’s Tower of Reading, one that runs like a skein through his the short essays and comments that he appends to selected passages of classical prose, is that of frustrated humanism and the resilient quest for fundamental decency that refuses to be suborned by narrow politics and nationalism. Zhong sees in the work and influence of Tao Yuanming, the fourth-century poet-recluse, an example of a similar ancient strain in Chinese letters.

My own initial encounter with ‘Chinese humanism’ was in my mid teens, when I read my mother’s copy of The Importance of Living by Lin Yutang. There Lin writes about his own journey through China’s literary tradition; he tells the reader that:

I have always wandered outside the precincts of philosophy and that gives me courage. There is a method of appealing to own’s own intuitive judgement, of thinking out one own’s ideas and forming one’s own independent judgments, and confessing them in public with childish impudence, and sure enough, some kindred souls in another corner of the world will agree with you.

Even then, I precociously thought of myself as ‘a kindred soul in another corner of the world’. Again, as Lin observes:

A person forming his ideas in this manner will often be astounded to discover how another writer said exactly the same things and felt exactly the same way, but perhaps expressed these ideas more easily and more gracefully. It is then that he discovers the ancient author and the ancient author bears him witness, and they become for ever friends in spirit.

Lin speaks of the ‘genial souls’ and the ‘friends in spirit’ who were silent collaborators in The Importance of Living. The writers to whom Lin looked ‘up to more as masters than as companions of the spirit’, men ‘whose wisdom seems to have come entirely without effort because it has become completely natural’ were Zhuangzi, who has featured elsewhere in The Tower of Reading, and Tao Yuanming, whose simplicity of spirit, Lin observed, ‘is the despair of smaller men.’ (See Lin’s introduction to The Importance of Living, dated 30 July 1937.)

My early encounter with Lin Yutang would help guide me to and then subsequently through the life and times of Feng Zikai, an artist, writer, translator who, like Lin, was inspired by Tao Yuanming. In turn, An Artistic Exile, my study of Feng Zikai, would begin and end with references to Tao Yuanming. In pursuing that work as a doctoral student in the 1980s, I learned that much of the material in Lin’s The Importance of Living had first appeared in the journals he had published in Shanghai in the early 1930s when he was part of a group of writers and editors who promoted an alternative Chinese path to modernity. Tao Yuanming helped them in that quest

— The Editor

***

Four perspectives on Tao Yuanming

Tao Yuanming previously featured in Ninth of the Ninth 重陽 Double Brightness (28 October 2017), a chapter in our series of New Sinology Jottings. There we noted that the recluse-poet has long been celebrated for his association with the chrysanthemum. A number of his poems on that topic, and others related to the delights of drinking wine, are among the most often quoted, and over-interpreted, works in the literary tradition. Famed for having given up service to the state for a life of leisure, writing, drinking, and occasional agricultural pursuits, Tao Yuanming is the archetype of a man who has rejected the onerous demands of the day to pursue instead the cultivation of the self. This quest for quietude, one that remains tinged with worldly concerns and anxieties, is recorded in poems that, for over 1600 years, have inspired artists, writers and readers alike.

New Sinology Jottings introduce readers to aspects of culture, history and politics that resonate with the modern world; at the same time, they (re)introduce works integral to the mytho-poetic realm of China. For some, such things are fustian and irrelevant, nothing less than an affront to today’s neophilia, a drag on the relentless urge to escape from the past. However, as Lu Xun observed in his habitually scathing manner: ‘you can’t leave the earth by simply tugging at your own hair’ 人不能拽著自己的頭髮離開地球. Our terrestrial musings do, nonetheless, direct the gaze towards the immortal and over the years we have featured well-known works, not to replicate the cliché-festooned echo chamber either of Chinese state culture or of its mass media, but rather to encourage readers to consider the old with new eyes. That impetus also finds expression in The Tower of Reading and its companion, Intersecting with Eternity.

***

Prefect Tao and Hippy Culture

Geremie R. Barmé

In China’s modern cultural maelstrom Tao Yuanming’s reputation has risen and fallen a number of times. We have previously noted that his poem Substance, Shadow, and Spirit featured in Confessions 懺悔錄, an agonised reflection on the dilemmas of life, work and politics by the journalist Huang Yuansheng 黃遠生 in 1915, shortly before he was assassinated in San Francisco by associates of Yuan Shikai, republican China’s president-cum-emperor.

The first decade of the Republic saw Qing-era worthies reduced to the state of remnants or ‘disengaged people’ 逸民. During the turbulence of the May Fourth era (c.1917-1927) some students and cultural figures continued to find both a refuge and an inspiration in Tao’s work, as was the case for Lin Yutang and Feng Zikai. Political progressives, however, decried Tao’s influence for the debilitating effect they felt that it had on young people. The ancient poet’s quietism was at loggerheads with the patriotic passion that the nation required. Escapism and the private pursuit of self-cultivation, both of which are associated with Tao Yuanming, have been repeatedly rejected by China’s power-holders ever since. In the 1950s, the Communist Party criticised the debilitating effects of ‘grey sentiments’ 灰色情緒 among those young people who resisted the endless rounds of political mobilisation and below we note Mao Zedong’s contempt for ‘Prefect Tao’ in 1959.

Tao Yuanming was repeatedly pilloried during the Cultural Revolution years, as were those who had previously championed him. Still there were those who remained detached — the self-styled 逍遙派 — as well as underground artists and poets who nurtured themselves on the margins of the political drama. Then, in the early 1980s, young people were castigated for a lack of enthusiasm for what was hailed as a ‘new era’. The romantic Taiwan wanderer San Mao inspired self-fulfilment in some while others found solace in Tibet and Yunnan, decades before the present popularity of the borderlands. By the middle of the decade, literary critics as disparate as Liu Xiaobo and He Xin cited Tao Yuanming and his ‘gazing at Southern Mountain’ as dangerously disengaged. He Xin, patronised by Maoist ideologues, lumped the recluse together with Zhuang Zi and his fellows from the Wei-Jin era, and mocked them for being part of a corrosive ‘hippy culture’.

Then, as Tao’s reputation, along with many writers and artists who had been inspired by him over the centuries, enjoyed a revival with the rise of material sufficiency and its concomitant culture of leisure from the 1990s, the authorities and Party ideologues again issued warnings about the negative effects of world-negating paragons like Tao.

Despite the bravado of the Xi Jinping era (2012-) and all of the talk of ‘struggle’, ‘red genes’ and ‘self-revolution’, economic and social realities have witnessed a new wave of disengagement. The ‘homebody culture’ of the 2000s, one populated by male and female ‘shut-ins’, known as 宅男宅女, has become part of a larger phenomenon, or what some have called a malaise. Even before the advent of Xi Jinping in 2012, young people and cashed-up professionals were seeking refuge in China’s southwest, where towns like Dali and Zhongdian/ Shangri-la were becoming counter-cultural capitals. More recently, nearby Chiangmai in Thailand has also offered something of a safe haven.

[Note: See also With Jack Kerouac in Chiang Mai — Planet Speakeasy & The Other China, Chapter Thirty-one in Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium.]

In China proper, popular expressions like ‘involution’ 內卷 and ‘lying flat’ 躺平 exemplify world-weariness and disengagement among those with more limited economic opportunities. These terms are the contemporary equivalent of the old T-shirt slogans like ‘I’m pissed off, leave me alone’ 煩着呢,別理我, which were part of a craze in 1991-1992. At the time, I dubbed the widespread post-1989 anomie among young people as ‘the graying of Chinese culture’. Thirty years later, in 2022, it seemed that it found a new articulation in the expression We’re the Last Generation 這是我們最後一代,謝謝!

In 2024, some Chinese internet commentators characterised the country’s extended economic downturn as the ‘garbage time of history’ 歷史的垃圾時間, one the Beijing media said reflected the ‘ sense of disillusionment and powerlessness as larger historical forces render personal efforts seemingly inconsequential, leading to recurring failures in their aspirations for a prosperous life’.

As had been the case every other time that ‘grey sentiment’ found popular expression, official critiques were frequent and unfailingly stentorian in tone. In mid July 2024, a series of rebuttals of the expression ‘garbage time of history’ were published both by online influencers and state media. ‘Garbage time’ was a fictitious nonsense, they declared, an ill-warranted narrative trap that ‘amplified common obstacles and encourages inaction and self-abandonment.’ One propagandist opined that the authors of such pearl-clutching criticism were ‘highly alert to this rising trend, believing it to be even more dangerous than the “lying flat” mentality.’ As Amy Hawkins reported in The Guardian:

Beijing Daily, the official newspaper of the Beijing branch of the Chinese Communist party, also recently responded to the trend, with an article entitled: “‘History’s Garbage Time’? True or False?”

“Is there any ‘garbage time’ in our history? This is a false proposition that is not worth refuting,” the Beijing Daily writer declared in the 3,000-character piece refuting the proposition.

For old timers, such high dudgeon brought to mind the early 1990s when the economic downturn that unfolded in the wake of 4 June 1989 saw an uptick in cynicism and popular works of satire. It was, above all, a mood that questioned the Communist Party’s unwavering imposition of certainty.

[Note: See the chapters ‘The Graying of Chinese Culture’ and ‘Consuming T-shirts in Beijing’ in In the Red: on contemporary Chinese culture, pp.99-178.]

Then, a new wave of economic reforms launched by Deng Xiaoping acted as something of a deus ex machina. Three decades later, Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium seemed mostly to offer rebranded old solutions to new problems.

[Note: See also The Art of Survival in the Age of Xi Jinping, 4 May 2023; and Alexander Boyd, Garbage Time of History, China Digital Times, 1 August 2024.]

***

***

The Poet of Escape

Tao Yuanming, or Tao Qian, is one of the most widely admired of the early Chinese poets. He lived in the period of disunity known as the Six Dynasties, when northern China was in the hands of non-Chinese leaders, and the south, where Tao lived, was ruled by a succession of weak and short-lived dynasties that had their capital at the present-day city of Nanjing. Tao’s poetry fully reflects the unease and anxiety that beset Chinese society at this time. At the same time, however, it strikes a rare and hardwon note of peace and contentment that, though only sporadic, seems to hold out some hope for escape from sorrow and suffering, a hope that is given poignant symbolic expression in his famous fable of the Peach Blossom Spring.

Tao Yuanming was born near modern Jiujiang in Jiangxi province, within sight of the famous Mount Lu, the “southern mountain” that he mentions in his poetry. His father and grandfather had pursued official careers, and though it was against his inclination, he too in time took up a post as adviser to one of the military leaders of the time. He did not fare well in this and subsequent posts, however, and he longed for the quiet rural life of his birthplace. His last post, that of magistrate of Pengze, he quit after only eighty days, retiring to the countryside to become a farmer for the remainder of his years.

His extant poems seem to have been written mainly in his later years, when he was living in a small house on the outskirts of a village with his family (he had five sons).

Many poems describe the quiet joys of country life, though others speak of famine, drought, and similar hardships. The Taoist side of the poet’s nature no doubt told him he should be content with such a life of seclusion, but his dedication to Confucian ideals kept him longing for the less troubled times of the past, when virtue prevailed and a scholar could in good conscience take an active part in affairs of state. There is an overall ambiguity in his poetry — exclamations upon the beauties of nature and the freedom and peace of rustic life, set uneasily alongside confessions of loneliness, frustration, and fear, particularly fear of death. He sought solace in his lute, his books, and above all in wine, about half of his poems mentioning his fondness for “the thing in the cup,” though in one of the poems he wrote depicting his own funeral [“Dirge”], he declares that he was never able to get enough of it.

At a time when Chinese poetry on the whole was marked by ornate diction and elaborate rhetorical devices, Tao Yuanming chose to write in a relatively plain and simple style — in translation he may even sound rather flat on first reading. Probably because of this plainness of style, and the homey and personal nature of most of his poems, he was not highly esteemed by his contemporaries. It was some centuries before the true worth of his works was recognized, though few today would question that he is one of the finest of the pre-Tang poets.

— Columbia Book of Chinese Poetry: From Early Times, 1984

***

***

Cultural Paragon of the Elite

The poetry of Tao Yuanming (Tao Qian, 365-427), a reclusive gentleman who quit his official post to live obscurely on a small private farm, is the classic body of writing on life in retirement. In his famous prose-poem “Returning Home” 歸去來兮辭 Tao described his decision to give up his job, his eager journey home, and his expanding sense of pleasure and release as he settled into his rustic retreat; the text became a kind of manifesto of reclusion, both as an ideal way of life and as a moral choice.

His fable of the “Peach Blossom Spring” 桃花源 tells of a rural utopia concealed beyond a narrow rock tunnel, found by chance at the farthest reaches of a stream and never to be found again; it represents a wistful fantasy of escape from a troubled world. “Master Five Willows” 五柳先生傳, a short essay whimsically summing up his character and principles, and many of his other writings also revolve around themes of solitude, reading, thinking, drinking, freedom, the countryside, the simple life.

These came to be the central ideals of elite private culture in China, and Tao was thought of as their ultimate embodiment; countless later texts summon him up through allusion, paraphrase, and commentary. He has a very strong presence in the visual arts as well. “Returning Home” has been illustrated in painting again and again, as have the “Peach Blossom Spring” and other verses on getting drunk, the rustic life, and favorite natural objects such as chrysanthemums and pine trees.

— Susan E. Nelson, Catching Sight of South Mountain: Tao Yuanming, Mount Lu, and the Iconographies of Escape, Archives of Asian Art, vol.52 (2000/2001): 11-43, at p.11, Chinese characters added

The Illusion of the Archetypal Recluse

Literature is not a transcendental, self-contained entity immune to the interaction of a field of historical, social, and cultural forces; but for premodern Chinese readers, faith in direct communication with an ancient author often eclipsed the sense of temporal distance between them—to the degree that the ancient author became an eternally present figure, impervious to change and unbound by the mores of his or her times.

This is particularly true in the case of Tao Yuanming, who is considered the archetypal recluse, and who, in the modern age, has been treated as a poet who represents something “quintessentially Chinese.” In other words, Tao Yuan- ming is not only taken out of his historical circumstances, but is also restricted to a rather fixed image. Although scholars and critics have tried to complicate such an image by pointing out Tao Yuanming’s discontent and struggle with his decision to give up public service for a reclusive life, the basic aspects of Tao Yuanming as a man and a poet have been set in place: a lofty-minded recluse, intensely loyal to the declining and later overthrown Jin dynasty; a spontaneous, willful, unconventional person who is often portrayed as drinking excessively, both in his own works and in visual arts of the later period (mostly post-Tang); a poet who chooses to pursue self-fulfillment through a set of private values rather than through public life, who finds contentment and pleasure in retirement and leisure, who defies material hardship for the sake of adhering to his personal principles, and who writes natural, unaffected, and simple poetry of nature in celebration of such a lifestyle. The perception of Tao Yuanming as an intense Jin loyalist, although with a long history, was particularly endorsed by Southern Song neo-Confucians, who must have discovered a special pathos in Tao Yuanming’s loyalty, in that it could be easily related to their own times. The fall of the Northern Song into the hands of the “barbarian” rulers was only too similar to the end of the Western Jin (265–317), and the constantly threatened security of the Southern Song reminded them of the situation of Tao Yuanming’s own dynasty, the Eastern Jin. Although there is in fact nothing in Tao Yuanming’s own poetry and prose that suggests such loyalist sentiment, it has not only become one of the hallmarks of Tao Yuan-ming’s personality since the Song but also a guiding principle in the interpretation of his writings, sometimes leading to extremely tenuous and distorted explications, as in the famous case of his most obscure poem, “An Account of Ale” (Shu jiu [述酒]). In the modern age, the issue of loyalty in Tao Yuanming studies does not provoke the same kind of passionate interest as it did in imperial China, but other aspects of the traditional image of Tao Yuanming still prevail, and sometimes take on a no less poignant urgency, for, in the nation-building project of the twentieth century, elements of Tao Yuanming’s works—such as the harmony between man and nature believed to be exemplified in his poetry about farming—have for many people come to define the essence of “Chinese art” and “Chinese culture.” The argument that Tao Yuanming’s poetry is “not really unadorned and plain,” that he was able to endure inner conflicts and doubts about his life decisions, and that he suffered from anger and anguish at the usurpers and rebels of his age, only serves to confirm the established image of Tao Yuanming and his works.

— Xiaofei Tian, Tao Yuanming and Manuscript Culture, University of Washington Press, 2005, pp.12-13, Chinese text added

[Note: See also Brendan O’Kane, Tao Yuanming “Home Again”, Burning House, 17 April 2023.]

***

To My Feckless Sons

‘It is hard for you to provide for your daily needs yourselves. I am sending you this servant to aid you in the labor of gathering wood and drawing water. He too is a man’s son and should be well treated.’

汝旦夕之費。自給為難。今遣此力。助汝薪水之勞。此亦人子也。可善遇之。

— trans. A.R. Davis

***

Reproaching My Sons

責子

White hair covers my temples —

My flesh is no longer firm,

And though I have five sons

Not one cares for brush and paper.

A-shu is sixteen years of age;

For laziness he surely has no equal.

A-xuan tries his best to learn

But does not really love the arts.

Yong and Duan at thirteen years

Can hardly distinguish six from seven;

Tongzi with nine years behind him

Does nothing but hunt for pears and chestnuts.

If such was Heaven’s decree

In spite of all that I could do,

Bring on, bring on

The Thing Within the Cup.

白髮被兩鬢,

肌膚不復實。

雖有五男兒,

總不好紙筆。

阿舒已二八,

懶惰故無匹。

阿宣行志學,

而不愛文術。

雍端年十三,

不識六與七。

通子垂九齡,

但覓梨與栗。

天運苟如此,

且進杯中物。

— trans. William Acker, originally titled ‘Putting the Blame on His Sons’

A Comment from The Tower of Reading:

Tao Yuanming says that his poem ‘Reproaching My Sons’ was written when ‘white hair covers my temples’. Although he might have boasted of having five sons, the eldest of whom was sixteen, he tells us that the youngest, a nine year-old, ‘does nothing but hunt for pears and chestnuts’, oblivious to everything else. When he took up an official post in Pengze, he thought it best to despatch a male servant who could give them a hand ‘gathering wood and drawing water’. The short note he addressed to his sons, quoted above, was a reflection of paternal concern, though he famously makes the point the worker is also ‘a man’s son and should be well treated.’ In this simple line Tao expresses something akin to universal humanity, or what the Confucian thinker Mencius meant by his famous remark ‘treat with the kindness due to youth the young in your own family, so that the young in the families of others shall be similarly treated’ 幼吾幼,以及人之幼.

[Note: See 《孟子·梁惠王上》:老吾老,以及人之老;幼吾幼,以及人之幼。天下可運於掌, translated by James Legge as:

Treat with the reverence due to age the elders in your own family, so that the elders in the families of others shall be similarly treated; treat with the kindness due to youth the young in your own family, so that the young in the families of others shall be similarly treated – do this, and the kingdom may be made to go round in your palm.]

This single line allows us claim that Tao Yuanming was without doubt a humanist. The simple words ‘he too is someone’s son’ are an admonishment to Tao’s sons that the laborer should be treated in a humane way. The opposite sentiment, common enough, holds that others are not worthy of equal treatment.

Such inhumanity was displayed by Qin Shihuang in his treatment of scholars, by Hitler in the way he regarded Jews and in how Stalin treated kulaks as ‘the enemies of the people’. The line ‘even if a few hundred million die, a few hundred million will survive’ reflects a similar contempt for humanity.

[Note: Here Zhong Shuhe sidesteps the censors by quoting an incendiary statement made by Mao Zedong without mentioning Mao by name. In his speech to the International Meeting of Communist and Workers Parties held in Moscow in November 1957, Mao famously addressed the threat of nuclear war:

‘In the worst case scenario, only half of humankind will die; that still leaves the other half.’

極而言之,死掉一半人,還有一半人。

— 毛澤東,在莫斯科共產黨和工人黨代表會議上的發言,一九五七年十一月十八日

In the course of human history, the kind of wisdom displayed by Tao Yuanming — basic humanity and compassion — has been like a lodestar, something that from the earliest times has offered a path leading to a better future for all. As for the dictators and tyrants who have resorted to massacring and murdering people, sooner or later they all end up shamed and pilloried, despised by eternity.

Original Chinese Text

學其短:The selected Classical Chinese text;

念樓讀:Zhong Shuhe’s translation into Modern Chinese; and,

念樓曰:Zhong Shuhe’s comment.

遣力給子書 陶潛

汝旦夕之費。自給為難。今遣此力。助汝薪水之勞。此亦人子也。可善遇之。

【学其短】

- 本文錄自葉楚傖《歷代名人短箋》。

- 陶潛,又名淵明,字元亮,東晉潯陽(今江西九江)人。

【念樓讀】你們年紀尚小,早晚生活安排,定有不少困難。現派去一名勞役,幫助你們做點打柴挑水之類的事情。他雖系奴僕,同樣是人生父母養的,對待他務必要和善一些。

【念樓曰】陶淵明在《責子詩》中嗟嘆過,自己「白髮被兩鬢」了,「雖有五男兒」,長子「阿舒已二八」還只有十六歲,最幼的「通子重九齡,但覓梨與栗」,更不懂事。所以他去彭澤當縣令,便派一名「力」(乾力氣活的奴僕)回家來助「薪水之勞」,照顧自己的兒子,這是出於父子之情。但在顧惜自己兒子的同時,他還能顧惜到這名「力」也是人家的兒子,說出「此亦人子也,可善遇之」這句話來,可謂充滿了博愛的精神,「幼吾幼以及人之幼」了。

就憑這一句話,陶淵明便當之無愧可稱為人道主義者。「此亦人子也」,就是將人當作人;但是還有一種與此相反的態度,則是不將人當作人。

秦始皇之對儒生,希特勒之對猶太人,斯大林之對富農和「人民公敵」,便是不將人當作人。「死掉幾個億,還有幾個億」,也是不將人當作人。

在人類歷史上,如陶公這樣的智者哲人,他們的仁愛之心、人道主義的思想,永遠是最燦爛的明星,指示著進化和提升的方向。屠戮、虐殺、迫害人之子的獨裁者和暴君,則一個個都已經或必然會被釘在恥辱柱上,永遠被人唾罵。

***

Source:

- Letter Five in ‘Short Family Letters’ 家人的短信十一篇之五, Section Twenty-four of Studying Short Classical Chinese Texts with The Master of The Tower of Reading 《念樓學短》,下冊,長沙:岳麓書社,2022年,第556-557頁。

Mao Zedong’s Ascent of Southern Mountain

On 29 June 1959, a little over a year and a-half after he addressed the International Meeting of Communist and Workers Parties in Moscow, mentioned above, Mao Zedong arrived at Lu Shan, the ‘Southern Mountain’ made famous by Tao Yuanming.

As chaos enveloped China at the height of the Great Leap Forward in 1959, Mao and his Communist colleagues convened at Mount Lu. The comfortable old summer villas of the town of Guling 牯嶺 (a Chinese transcription of ‘Cooling’, the name used by the foreigners who used the area as a hill station from the late-nineteenth century) now housed senior cadres and the meeting rooms and large auditorium built by Chiang Kai-shek, who had refitted the resort as his summer capital 夏都, became the site of one of modern China’s most momentous, and tragic, political clashes, known as the Lushan Conference 廬山會議.)

Mao settled in to a villa in the old summer resort town of Guling, the previous occupant of which had been his nemesis Chiang Kai-shek and his wife, Soong Mei-Ling.

The Party leaders had gathered in that otherworldly eyrie to assess the achievements of the Great Leap Forward, a nationwide movement launched in February 1958 that was aimed at catapulting China into a communist utopia. Neither that movement, nor the conclave at Lu Shan, went well. However, that all lay in the future and, as Mao reflected on the natural wonders of the scenery as he had been chauffeured up the mountain on that first day, he was moved to write a poem. Given the murderous results of the willful economic policies of the Great Leap — the number of people who starved to death in what is regarded as the greatest man-made famine in history is calculated in the tens of millions — Mao’s poem, Ascent of Lu Shan 七律·登廬山, is surely the most grotesque work in what was already a blood-soaked oeuvre.

Contemplating China’s leap into communism, Mao felt positively ‘dizzy with success’, to use Stalin’s old expression, and in his poem he breezily dismisses Prefect Tao 陶令 — Tao Yuanming — and his utopian parable, ‘The Peach Blossom Spring’ 桃花源記 (for the text of that essay, see below). It was only the Communists, under Mao’s sagacious leadership, of course, who had finally been able to turn the ancient writer’s vision into present reality; China was now truly a Land of Peach Blossoms:

Perching as after flight, the mountain towers over the Yangtze;

I have overleapt four hundred twists to its green crest.

Cold-eyed I survey the world beyond the seas;

A hot wind spatters raindrops on the sky-brooded waters.

Clouds cluster over the nine streams, the yellow crane floating,

And billows roll on to the eastern coast, white foam flying.

Who knows whither Prefect Tao Yuanming is gone

Now that he can till fields in the Land of Peach Blossoms?

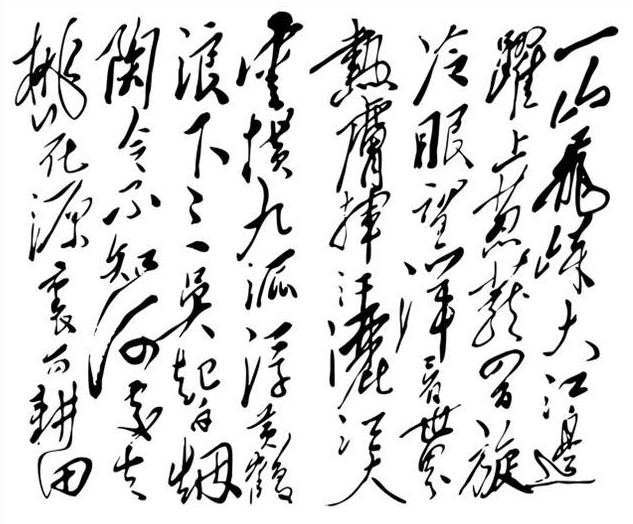

一山飛峙大江邊,

躍上蔥蘢四百旋。

冷眼向洋看世界,

熱風吹雨灑江天。

雲橫九派浮黃鶴,

浪下三吳起白煙。

陶令不知何處去,

桃花源里可耕田。

***

[Note: For more on Lu Shan/ Southern Mountain and our series Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium, see 真面目 The True Face of Mount Lu, 1 January 2022.]

One Poem, Four Translations

and a Comment

Selected by Duncan Campbell

‘Drinking Wine’ 飲酒詩 is a series of twenty poems on Tao Yuanming’s favourite subject. The fifth poem, which contains the line 採菊東籬下 悠然見南山, is the most famous and influential verse in the cycle. During modern China’s quest for Wealth and Power, it has also been the single most controversial line in Tao’s body of work. While for some it encapsulates other-worldly detachment, for others it sums up a corrosive quietism that threatens the vitality of the nation.

Duncan Campbell has selected four translations of Poem V in the ‘Drinking Wine’ cycle, to which we have added a comment on whether Tao suddenly glimpsed Southern Mountain or if he had fixated on it as he picked chrysanthemums at the eastern hedge of his garden.

Tao’s poem rightly also belongs in our series Intersecting with Eternity.

— Geremie R. Barmé

***

Preface to Twenty Poems on Drinking

Mine is a secluded life of leisure with few diversions. As the night lengthens in the autumn I have got into the habit of having a drink. With only my shadow to keep me company, I drain my supply to the dregs; inebriated, I dash off lines of verse to amuse myself. Quite a disorderly pile of poems has built up, so I’ve had someone write them out both to indulge myself and to delight others.

余閑居寡歡,兼秋夜已長,偶有名酒,無夕不飲。顧影獨盡,忽焉復醉。既醉之後,輒題數句自娛。紙墨遂多,辭無詮次。聊命故人書之,以為歡笑爾。

— trans. G.R.B.

飲酒詩

陶淵明

結盧在人境 而無車馬喧

問君何能爾 心遠地自偏

採菊東籬下 悠然見南山

山氣日夕佳 飛鳥相與還

此還有真意 欲辨已忘言

***

***

I

I built my hut in a zone of human habitation,

Yet near me there sounds no noise of horse or coach.

Would you know how that is possible?

A heart that is distant creates a wilderness round it.

I pluck chrysanthemums under the eastern hedge,

Then gaze long at the distant summer hills.

The mountain air is fresh at the dusk of day:

The flying birds two by two return.

In these things there lies a deep meaning;

Yet when we would express it, words suddenly fail us.

— from ‘Twelve Poems’, translated by Arthur Waley, 1918

II

I built my house near where others dwell,

And yet there is no clamor of carriages and horses.

You ask of me ‘How can this be so?’

‘When the heart is far the place of itself is distant.’

I pluck chrysanthemums under the eastern hedge,

And gaze afar towards the southern mountains.

The mountain air is fine at evening of the day

And flying birds return together homewards.

Within these things there is a hint of Truth,

But when I start to tell it, I cannot find the words.

— ‘I Built My House’, translated by William Acker, 1952

III

I built a cottage right in the realm of men,

yet there was no noise from wagon and horse.I ask you, how can this be so?—

when mind is far, its place becomes remote.I picked a chrysanthemum by the eastern hedge,

off in the distance gazed on south mountain.Mountain vapors glow lovely in twilight sun,

Where birds in flight join in return.There is some true significance here:

I want to expound it but have lost the words.

— ‘Drinking Wine V’, translated by Stephen Owen, 1996

IV

I live here in a village house withoutAll that racket horses and carts stir up,and you wonder how that could ever be.Wherever the mind dwells apart is itselfa distant place. Picking chrysanthemumsat my east fence, I see South Mountainfar off: air lovely at dusk, birds in flightreturning home. All this means something,something absolute: whenever I startTo explain it, I forget words altogether.

— ‘Drinking Wine’, translated by David Hinton, 2002

***

***

A Comment on

Seeing 見 and Gazing 望

採菊東籬下 悠然望南山

採菊東籬下 悠然見南山

The contested textual variant in this poem appears in the third position of the sixth line: the verb wang [望] (to gaze at) is also read jian [見] (to see). Cai Qi cites it as a primary example of the serious problem posed to editors and collators by “bad” manuscript copies: “The poet’s relaxation, detachment and complacency is expressed as such that he seems to have gone beyond the bounds of the universe. The vulgar editions usually have wang instead of jian. If so, then the line would be spoiled.” Such bad choices, Cai Qi alerts us, “simply destroy the fine tone of the entire poem.”

Cai Qi’s opinion originates from the great literary master of the age, Su Shi, who argues passionately for the reading jian:

Because of picking the chrysanthemum flowers, he happened to see the mountain, and what he saw corresponded perfectly to his state of mind. This line is most marvelous. In recent years all the vulgar editions have “gazing at South Mountain,” which takes away the life of the whole poem. The intention of the ancients was deep and subtle, but vulgar people carelessly alter the text as they wish. This is most abominable. [因採菊而見山,境與意會,此句最有妙處。近歲俗本皆作’望南山’,則此一篇神氣都索然矣。古人用意深微,而俗士率然妄以意改,此最可疾。]

Thus, for Su Shi, the act of seeing implies a casual effortlessness, the gift of acquiring something without looking for it; but “gazing” would indicate a longing on the poet’s part, too ardent, too eager, for the Northern Song master’s taste.

— Xiaofei Tian, Tao Yuanming and Manuscript Culture: The Record of a Dusty Table, University of Washington Press, 2005, p.31

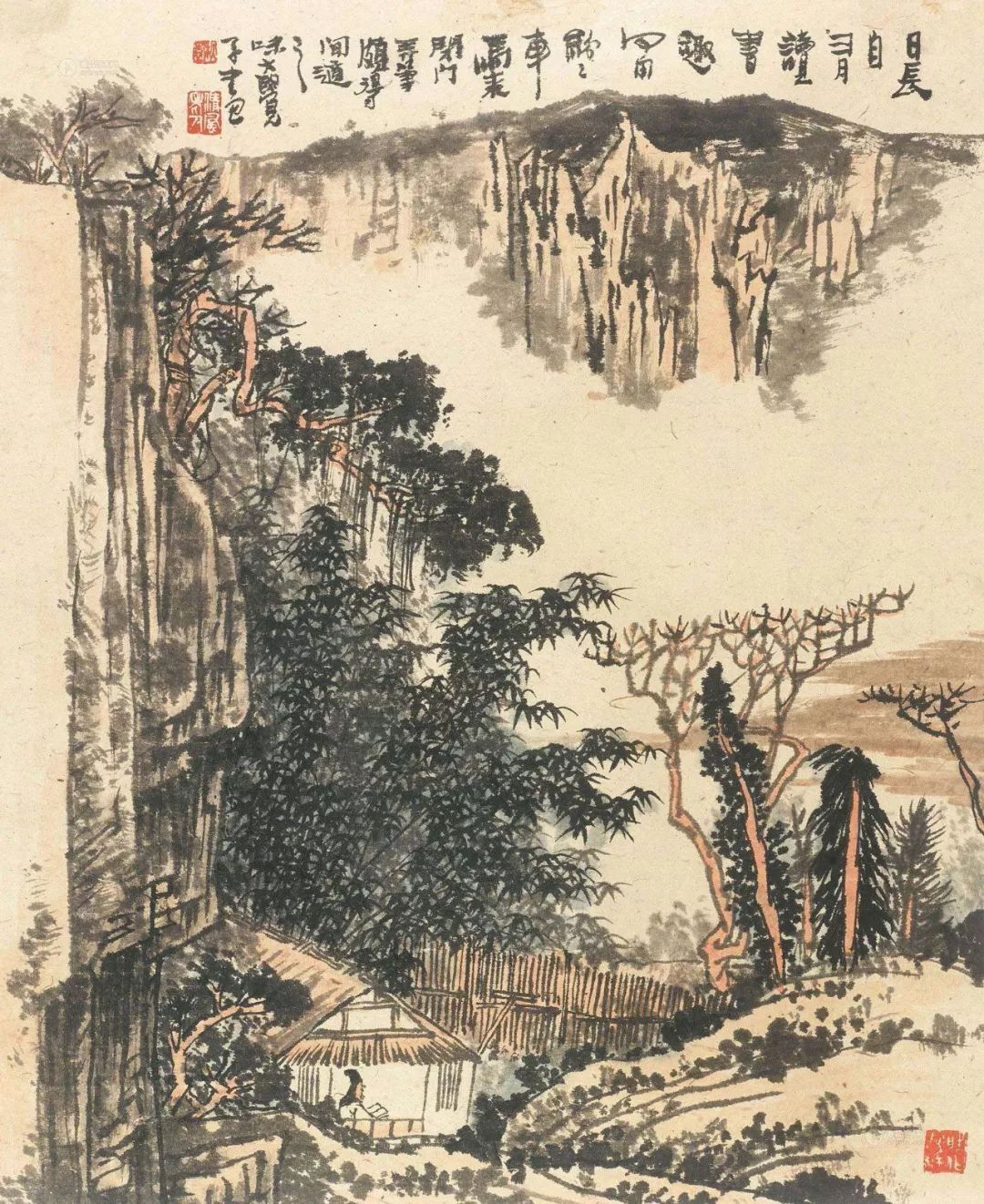

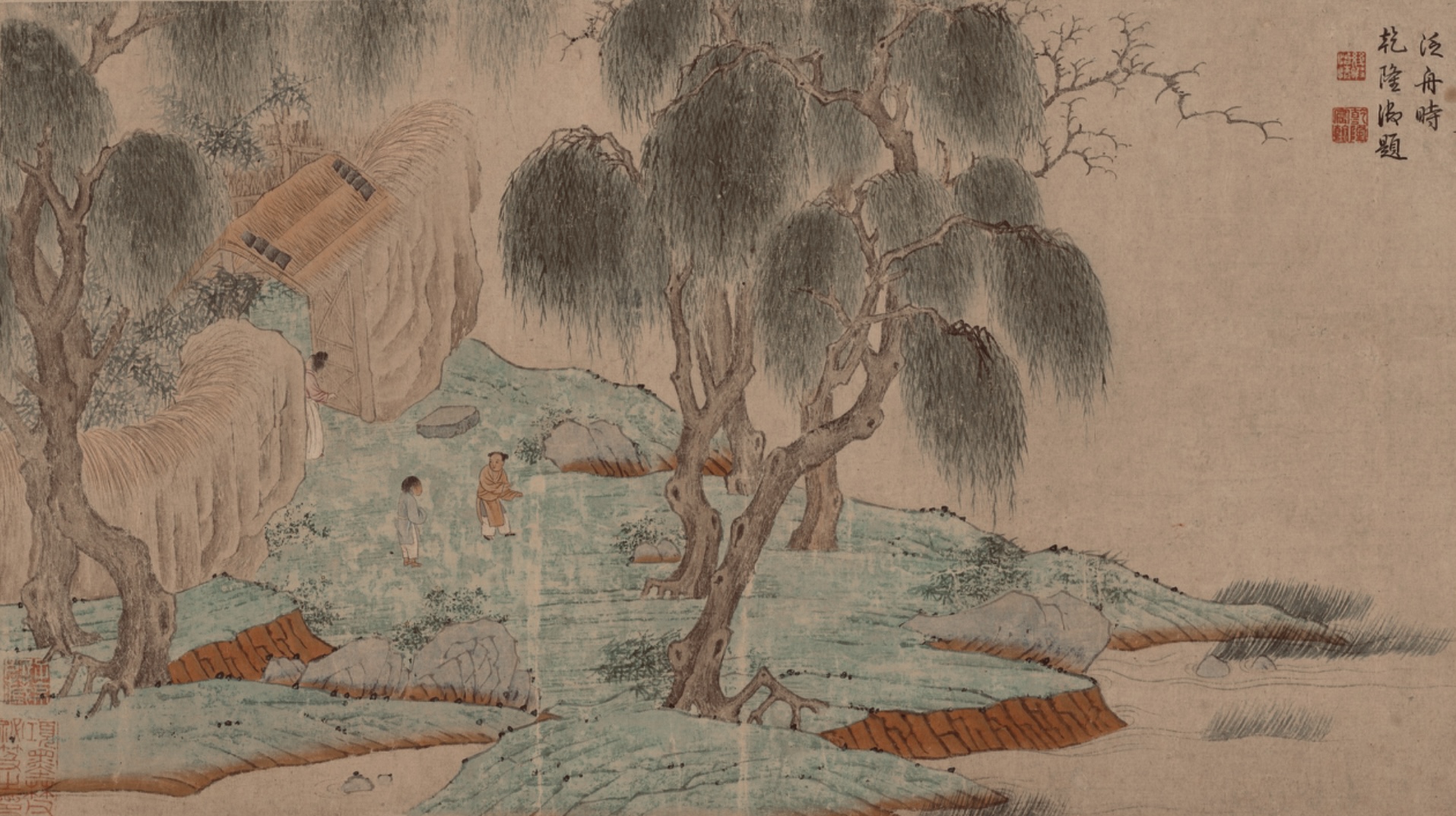

A Calligraphic Interpretation of ‘Drinking Wine’

Zhang Dejin

Chrysanthemums in the Eastern Garden

…an Inspector was sent by the commanders to Tao’s district. Tao’s subordinates told him that he ought to tie his girdle and call on the Inspector. Tao said with a sigh: ‘I cannot for five pecks of rice bow before a country bumpkin.’ The same day he untied his seal-ribbon and gave up the post… .

郡遣督郵至,縣吏白應束帶見之,潛嘆曰:吾不能為五斗米折腰,拳拳事鄉里小人邪。義熙二年,解印去縣。

— from ‘Biography of Tao Yuanming’, translated by A.R. Davis

***

Chrysanthemums were the favorite flower of Tao Qian (or Tao Yuanming, 365-427), a poet who retired in midlife to a small estate to live out his days in rustic obscurity, drinking wine and writing poetry. It was a rough period in Chinese history, with much of the land occupied by foreign invaders and the remainder governed by unstable and short-lived native dynasties. Tao chose to keep to himself. Private and quiet as his life was, though, his reputation grew steadily after his death, eventually reaching immense stature. Since the eighth century his poetry and life story have been familiar to every educated Chinese.

Tao kept a chrysanthemum patch by the eastern fence of his property, and from this one of the oldest extant paintings of him, a small scroll by the early thirteenth-century court artist Liang Kai 梁楷, takes its name: Scholar of the Eastern Fence 東籬高士. The poet is pictured walking in the breeze by a grove of trees and looking off into the distance, a chrysanthemum in his raised right hand (see below). The presentation of the flower-pinched carefully between his fingers and held upright and level with his face—is unmistakably meaningful. Whether held in his hand, set in a vase, or growing in the ground nearby, it was to remain Tao’s characteristic attribute in later images. …

What was the special quality of “Tao-ness” with which later people wanted to affiliate themselves? What, specifically, among the various ideas associated with Tao Qian, did the chrysanthemum signify as subject or attribute in the history of Chinese pictorial art?

— Susan E. Nelson, Revisiting the Eastern Fence: Tao Qian’s Chrysanthemums, Art Bulletin, vol.83, no.3 (September 2001), p.437, Chinese characters added

***

***

The Double Ninth, or Ninth Day as it was commonly called, was traditionally celebrated with a pleasant fall excursion. In a custom going back at least to the early third century, people would climb a scenic hill, drink chrysanthemum wine, and compose poetry. Tao’s famous eastern fence outing and poem correspond to this practice, and his verses quoted above on floating chrysanthemum petals in “this Care Dispelling Thing” were written on the Double Ninth. In later times the holiday became in some measure a commemorative Tao Qian occasion.? From the eighth century on, poems composed on the Double Ninth frequently mention him or paraphrase his verses; Double Ninth paintings allude to him as well.

— Susan E. Nelson, Revisiting the Eastern Fence, p.445

At Leisure on the Ninth Day

九日閑居

Tao Yuanming

When I was living in retirement, I delighted in the name of the Double Ninth. The autumn chrysanthemums filled my garden but I had no means of taking wine. So in want for it, I partook of the Ninth Day flowers and put my feelings into words.

余閑居,愛重九之名。秋菊盈園,而持醪靡由,空服九華,寄懷於言。

Life is short but desires are always many;

We men delight in living long.

The day and month come at due time;

Every common man delights in the day’s name.

The dews are chill, the genial breezes cease;

In the clear air the heavenly signs are bright.

Of the departed swallows not a shadow remains,

From the arriving geese there is abundance of noise.

Wine can drive out manifold cares,

Chrysanthemums may arrest declining years.

How is it with the rustic hut scholar?

In want, he watches the season passing.

The dusty cup shames the empty wine-jar;

The cold flowers vainly display themselves.

Adjusting my robe, alone I sing a song of leisure;

In my brooding arise deep feelings.

At rest, truly there are many joys:

My lingering is surely not without achievement?

世短意常多,

斯人樂久生。

日月依辰至,

舉俗愛其名。

露淒暄風息,

氣澈天象明。

往燕無遺影,

來雁有餘聲。

酒能祛百慮,

菊解制頹齡。

如何蓬廬士,

空視時運傾。

塵爵恥虛罍,

寒華徒自榮。

斂襟獨閒謠,

緬焉起深情。

棲遲固多娛,

淹留豈無成。

***

Written on the Ninth Day of the

Ninth Month of the Year Jiyou [409 CE]

己酉歲九月九日

Slowly, slowly,

the autumn draws to its close.

Cruelly cold

the wind congeals the dew.

Vines and grasses

will not be green again —

The trees in my garden

are withering forlorn.

The pure air

is cleansed of lingering lees

And mysteriously,

the Heaven’s realms are high.

Nothing is left

of the spent cicada’s song,

A flock of geese

goes crying down the sky.

The myriad transformations

unravel one another

And human life

how should it not be hard?

From ancient times

there was none but had to die,

Remembering this

scorches my very heart.

What is there I can do

to assuage this mood?

Only enjoy myself

drinking my unstrained wine.

I do not know

about a thousand years,

Rather let me make

this morning last forever.

靡靡秋已夕,

淒淒風露交。

蔓草不複榮,

園木空自凋。

清氣澄餘滓,

杳然天界高。

哀蟬無留響,

叢雁鳴雲霄。

萬化相尋繹,

人生豈不勞。

從古皆有冇,

念之中心焦。

何以稱我情。

濁酒且自陶。

千載非所知,

聊以永今朝。

— translations by William Acker

***

***

The Chrysanthemums in the Eastern Garden

東園玩菊

Bo Juyi

白居易

The days of my youth left me long ago;

And now in their turn dwindle my years of prime.

With what thoughts of sadness and loneliness

I walk again in this cold, deserted place!

In the midst of the garden long I stand alone;

The sunshine, faint; the wind and dew chill.

The autumn lettuce is tangled and turned to seed;

The fair trees are blighted and withered away.

All that is left are a few chrysanthemum-flowers

That have newly opened beneath the wattled fence.

I had brought wine and meant to fill my cup,

When the sight of these made me stay my hand.

I remember, when I was young,

How easily my mood changed from sad to gay.

If I saw wine, no matter at what season,

Before I drank it, my heart was already glad.

But now that age comes,

A moment of joy is harder and harder to get.

And always I fear that when I am quite old

The strongest liquor will leave me comfortless.

Therefore I ask you, late chrysanthemum-flower

At this sad season why do you bloom alone?

Though well I know that it was not for my sake,

Taught by you, for a while I will open my face.

少年昨已去,

芳歲今又闌。

如何寂寞意,

復此荒涼園。

園中獨立久,

日澹風露寒。

秋蔬盡蕪沒,

好樹亦凋殘。

唯有數叢菊,

新開籬落間。

攜觴聊就酌,

為爾一留連。

憶我少小日,

易為興所牽。

見酒無時節,

未飲已欣然。

近從年長來,

漸覺取樂難。

常恐更衰老,

強飲亦無歡。

顧謂爾菊花,

後時何獨鮮。

誠知不為我,

借爾暫開顏。

— translated by Arthur Waley

***

***

Double Brightness

— to the tune Drunk in Flower Shadows

醉花陰·薄霧濃雲愁永晝

Li Qingzhao

李清照

light mists and heavy cloud

a day of sorrow that would never end

jui-nao incense oozing

from the censer’s maw.

another fine festival

Double Brightness

come and gone

First chill of midnight steals

in my silken-netted cage

touches

my jade pillow

by the eastern hedge, wine in hand,

in the golden aftermath of dusk

I stood

perfume darkly blowing in my sleeve

Vain to deny grief:

See, when the west wind stirs the blind

this visage

than the golden flower more frail

薄霧濃雲愁永晝,

瑞腦消金獸。

佳節又重陽,

玉枕紗廚,

半夜涼初透。

東籬把酒黃昏後,

有暗香盈袖。

莫道不銷魂,

簾卷西風,

人比黃花瘦。

— translated by John Minford

As the translator notes:

The one specific reference in this poem is to the Double Brightness Festival. But there has never been any doubt in the minds of Chinese readers that Li Qingzhao is here expressing, in the oblique manner of the ci-lyric form her grief at separation from her husband. She uses the festival to counterpoint this grief, and in the second stanza conjures up the shade of Tao Yuanming and his famous ‘chrysanthemums under the eastern hedge’. Tao’s detachment and repose are in stark contrast to the poetess’ all-too-human emotion. That emotion is none the less potent for being so understated.

On one level, the whole poem can be read as the woman lyricist’s response to the Double Brightness tradition in poetry, of which Tao the Hermit was the founding father.

A Meeting of Minds

Bo Juyi and Tao Yuanming

translated by Duncan Campbell

Preface to Poems Inspired by Tao Qian (811-814 CE)

When I retreated home to live on the banks of the River Wei, I closed my gate tight and didn’t venture out at all. It rained incessantly at the time and I had at hand little to amuse myself with. It so happened that a new batch of our family’s homebrew had just matured, and so I sat alone drinking as the rain poured down, I invariably becoming quite tipsy and remained in that state throughout the day. In this way, I brought a sense of self-contentment to my lazy and wayward heart, and my mind became focused on this to the exclusion of everything else. And, as a result of this, I began to chant some of Tao Yuanming’s poems, all of which seemed to coincide exactly with my own state of mind [適與意會]. In imitation of their form I came up with sixteen of my own poems. In my cups, I would sing madly; sobering up, I would immediately write them down. From these, you will know me; I hide nothing.

余退居渭上,杜門不出,時屬多雨,無以自娛。會家醞新熟,雨中獨飲,往往酣醉,終日不醒。懶放之心,彌覺自得,故得於此而有以忘於彼者。因詠陶淵明詩,適與意會,遂俲其體,成十六篇。醉中狂言,醒輒自哂。然知我者,亦無隱焉。

[Note: For the cycle of sixteen poems Bo Juyi composed in homage to Tao Yuanming, see 效陶潛體詩十六首.]

***

Paying a Visit to Master Tao’s Old Home, a preface and a poem

訪陶公舊宅並序

I have always much admired Tao Yuanming’s character, and some time ago when I was living in idleness on the banks of the River Wei, I wrote sixteen poems entitled ‘Written in Imitation of the Tao Qian Style’. Then, as I passed by Chaisang and through Chestnut Village during my present trip to Hermitage Mountain, I could not help thinking of him, so I paid a visit to old home. Having done so, I found myself incapable of remaining silent, thus the following lines. … …

予夙慕陶淵明為人,往歲渭川閑居,嘗有《效陶體詩》十六首。今游廬山,經柴桑,過栗里,思其人,訪其宅,不能默默,又題此詩云。

… His intestines were never full,

His body was never covered.

Often was he summoned but never did he respond,

Thus may it be said that he was a true sage.

I was born long after his lifetime,

Separated from him by a full five hundred years.

But each time I read his ‘Biography of the Master of the Five Willows’,

In my mind’s eye I can see him, my heart aquiver.In the past, I sang in his lingering style,

And wrote sixteen poems.

Today I pay a visit to his former residence,

And amongst the trees here he seems to be standing before me.

I admire not that his cup always contained some wine,

Nor that his lute was never with string.I admire rather that he cast aside the pursuit of wealth and fame,

Content to grow old and die here in this hilly garden.

Chaisang has been settled since distant antiquity,

And Chestnut Village is set amidst aged mountains and rivers.

I see no chrysanthemums growing beneath the hedge,

But the hollows here are shrouded in mist.Although I have heard nothing about his sons and grandsons,

The clan does not seem to have departed this place.

And every time I encounter someone surnamed Tao,

I find myself drawn powerfully to them.

… 腸中食不充,身上衣不完。連徵竟不起,斯可謂真賢。

我生君之後,相去五百年。每讀五柳傳,目想心拳拳。

昔常詠遺風,著為十六篇。今來訪故宅,森若君在前。

不慕尊有酒,不慕琴無弦。慕君遺榮利,老死此丘園。

柴桑古村落,栗里舊山川。不見籬下菊,但餘墟中煙。

子孫雖無聞,族氏猶未遷。每逢姓陶人,使我心依然。

***

About eight miles north of Mount Lu was a hamlet called Shang-jing. The poet Tao Yuanming (376–427) had once lived there. It was remarkable that Li Bai journeyed to the small village to look at Tao’s homestead and pay his respects at his grave, which had fallen into disrepair, the words on the stone hardly legible. Like his deserted homestead, Tao had remained obscure for more than three centuries after his death. Only two decades prior to Li Bai’s visit had Tao’s poetry begun to be recognized by Tang poets, particularly for his presentation of immediate experiences in nature and the daily life of the countryside. Evidently Li Bai was one of his new admirers. Viewed from Tao’s homestead, Mount Lu loomed in the distance, often half-hidden in clouds, against which birds sailed in the misty sky. The sublime scene depicted in Tao’s poem “Drinking Wine” must refer to this view:

“Picking chrysanthemums under my eastern hedge,/ I raise my eyes and see the mountain in the south.”

— Ha Jin, The Banished Immortal, A Life of Li Bai (Li Bo), Penguin, 2019

A Lover of Life: Tao Yuanming

Lin Yutang

It has been shown, therefore, that with the proper merging of the positive and the negative outlooks on life, it is possible to achieve a harmonious philosophy of the “half-and-half” [expressed in ‘the Half-and-Half Song’ by Li Mi’an] lying somewhere between action and inaction, between being led by the nose into a world of futile busy-ness and complete flight from a life of responsibilities, and that so far as we can discover with the help of all the philosophies of the world, this is the sanest and happiest ideal for man’s life on earth. What is still more important, the mixture of these two different outlooks makes a harmonious personality possible, that harmonious personality which is the acknowledged aim of all culture and education. And significantly, out of this harmonious personality, we see a joy and love of life.

[Note: For the details of ‘The Half-and-Half Song’ 半半歌 by Li Mi’an 李密庵, see Occupied with Idleness.]

It is difficult for me to describe the qualities of this love of life; it is easier to speak in a parable or tell the story of a true lover of life, as he really lived. And the picture of Tao Yuanming, the greatest poet and most harmonious product of Chinese culture, inevitably comes to my mind. There will be no one in China to object when I say that Tao represents to us the most perfectly harmonious and well-rounded character in the entire Chinese literary tradition. Without leading an illustrious official career, without power and outward achievements and without leaving us a greater literary heritage than a thin volume of poems and three or four essays in prose, he remains to-day a beacon shining through the ages, forever a symbol to lesser poets and writers of what the highest human character should be. There is a simplicity in his life, as well as in his style, which is awe-inspiring and a constant reproach to more brilliant and more sophisticated natures. And he stands, today, as a perfect example of the true lover of life, because in him the rebellion against worldly desires did not lead him to attempt a total escape, but has reached a harmony with the life of the senses. About two centuries of literary romanticism and the Taoistic cult of the idle life and rebellion against Confucianism had been working in China and joined forces with the Confucian philosophy of the previous centuries to make the emergence of this harmonious personality possible. In Tao we find the positive outlook had lost its foolish complacency and the cynic philosophy had lost its bitter rebelliousness (a trait we see still in Thoreau—a sign of immaturity), and human wisdom first reaching full maturity in a spirit of tolerant irony.

Tao represents to me that strange characteristic of Chinese culture, a curious combination of devotion to the flesh and arrogance of the spirit, of spirituality without asceticism and materialism without sensuality, in which the senses and the spirit have come to live together in harmony. For the ideal philosopher is one who understands the charm of women without being coarse, who loves life heartily but loves it with restraint, and who sees the unreality of the successes and failures of the active world, and stands somewhat aloof and detached, without being hostile to it. Because Tao reached that true harmony of spiritual development, we see a total absence of inner conflict and his life was as natural and effortless as his poetry.

Tao was born toward the end of the fourth century of our era, the great grandson of a distinguished scholar and official, who in order to keep himself from being idle, moved a pile of bricks from one place to another in the morning, and moved them back in the afternoon. In his youth he accepted a minor official job in order to support his old parents, but soon resigned and returned to the farm, tilling the field himself as a farmer, from which he developed a kind of bodily ailment. One day he asked his relatives and friends, “Would it be all right for me to go out as a minstrel singer in order to pay for the upkeep of my garden?” On hearing this, certain of his friends got him a position as a magistrate of Pengze, near Jiujiang. Being very fond of wine, he commanded that all the fields belonging to the local government should be planted with glutinous rice, from which wine could be made, and only on the protestations of his wife did he allow one-sixth to be planted with another kind of rice. When a government delegate came and his secretary told him that he should receive the little fellow with his gown properly girdled, Tao sighed and said, “I cannot bend and bow for the sake of five bushels of rice.” And he immediately resigned and wrote that famous poem, “Ah, Homeward Bound I Go!” [See below.] From then on, he lived the life of a farmer and repeatedly refused later calls to office. Poor himself, he lived in communion with the poor, and he expressed a certain paternal regret in a letter to his sons that they should be so poorly clad and do the work of a common labourer. But when he managed to send a peasant boy to his sons when he was away, to help them do the work of carrying water and gathering fuel, he said to them, “Treat him well, for he is also someone’s son.” [See Zhong Shuhe’s comment on this above.]

His only weakness was a fondness for wine. Living very much to himself, he seldom saw guests, but whenever there was wine, he would sit down with the company, even though he might not be acquainted with the host. At other times, when he was the host himself and got drunk first, he would say to his guests, “I am drunk and thinking of sleep; you can all go.” He had a stringed instrument, the qin, without any strings left. It was an ancient instrument that could be played only in an extremely slow manner and only in a state of perfect mental calm. After a feast, or when feeling in a musical mood, he would express his musical feelings by fondling and fingering this stringless instrument. “I appreciate the flavour of music; what need have I for the sounds from the strings?” [但識琴中趣,何勞弦上聲] [1]

[1] Considered one of his greatest sayings by the Chinese.

Humble and simple and independent, he was extremely chary of company. A magistrate, one Wang, who was his great admirer, wanted to cultivate his friendship, but found it very difficult to see him. With his perfect naturalness he said, “I’m keeping to myself because by nature I’m not made for the life of society, and I am staying in the house because of an ailment. Far be it from me to act in this manner in order to acquire a reputation for being high and aloof.” Wang therefore had to plot with a friend in order to see him; this friend had to induce him to leave his home, by inviting him to a feast and an accidental meeting. When he was half-way and stopped at a pavilion, wine was presented. Tao’s eyes brightened and he gladly sat down to drink, when Wang, who had been hiding nearby, came out to meet him. And he was so happy that he remained there talking with him the whole afternoon, and forgot to go on to his friend’s place. Wang saw that he had no shoes on his feet and ordered his subordinates to make a pair for him. When these minor officials asked for the measurements, he stretched forth his feet and asked them to take the measure. And thereafter, whenever Wang wanted to see him, he had to wait in the forest or around the lake, so that perchance he might meet the poet. Once when his friends were brewing wine, they took his linen turban to use it as a strainer, and after the wine had been strained, he wound the turban again around his head.

There was then in the great Lushan Mountains, at whose foot he lived, a great society of illustrious Zen Buddhists, and the leader, a great scholar, tried to get him to join the Lotus Society. One day he was invited to come to a party, and his condition was that he should be allowed to drink. This breaking of the Buddhist rule was granted him and he went. But when it came to putting his name down as a member, he “knitted his brows and stole away.” This was a society that so great a poet as Xie Lingyun [謝靈運] had been very anxious to join, but could not get in. But still the abbot courted his friendship and one day he invited him to drink, together with another great Taoist friend. They were then a company of three; the abbot, representing Buddhism, Tao representing Confucianism, and the other friend representing Taoism. It had been the abbot’s life vow never to go beyond a certain bridge in his daily walks, but one day when he and the other friend were sending Tao home, they were so pleasurably occupied in their conversation that the abbot went past the bridge without knowing it. When it was pointed out to him, the company of three laughed. This incident of the three laughing old men became the subject of popular Chinese paintings, because it symbolized the happiness and gaiety of three carefree, wise souls, representing three religions united by the sense of humour.

[China Heritage note: for more on what is known as the ‘Three Laughs at Tiger Creek’ 虎溪三笑, see Bathing Baby Buddha, China Heritage, 3 May 2017.]

And so he lived and died, a carefree and conscience-free, humble peasant-poet, and a wise and merry old man. But something in his small volume of poems on drinking and the pastoral life, his three or four casual essays, one letter to his sons, three sacrificial prayers (including one to himself), and some of his remarks handed down to posterity shows a sentiment and a genius for harmonious living that reached perfect naturalness and never has yet been surpassed. It was this great love of life that was expressed in the poem which he wrote one day in November, A.D. 405, when he decided to lay down the burdens of the magistrate’s office.[1]

[1] This poem is in the form of a fu [賦], progressing in parallel constructions, like the Psalms, and sometimes rhymed.

— Lin Yutang, The Importance of Living, pp.119-123, Chinese text added

***

***

Homeward Bound

歸去來兮辭

translated by Lin Yutang

Ah, homeward bound I go! Why not go home, seeing that my field and garden with weeds are overgrown? Myself have made my soul serf to my body: why have vain regrets and mourn alone?

Fret not over bygones and the forward journey take. Only a short distance have I gone astray, and I know to-day I am right, if yesterday was a complete mistake.

Lightly floats and drifts the boat, and gently flows and flaps my gown. I inquire the road of a wayfarer, and sulk at the dimness of the dawn.

歸去來兮,田園將蕪胡不歸。既自以心為形役,奚惆悵而獨悲。悟已往之不諫,知來者之可追。實迷途其未遠,覺今是而昨非。舟遙遙以輕颺,風飄飄而吹衣。問徵夫以前路,恨晨光之熹微。

Then when I catch sight of my old roofs, joy will my steps quicken. Servants will be there to bid me welcome, and waiting at the door are the greeting children.

Gone to seed, perhaps, are my garden paths, but there will still be the chrysanthemums and the pine! I shall lead the youngest boy in by the hand, and on the table there stands a cup full of wine!

Holding the pot and cup I give myself a drink, happy to see in the courtyard the hanging bough. I lean upon the southern window with an immense satisfaction, and note that the little place is cosy enough to walk around.

The garden grows more familiar and interesting with the daily walks. What if no one ever knocks at the always closed door! Carrying a cane I wander at peace, and now and then look aloft to gaze at the blue above.

There the clouds idle away from their mountain recesses without any intent or purpose, and birds, when tired of their wandering flights, will think of home. Darkly then fall the shadows and, ready to come home, I yet fondle the lonely pines and loiter around.

乃瞻衡宇,載欣載奔。僮僕歡迎,稚子候門。三徑就荒,松菊猶存。攜幼入室,有酒盈樽。引壺觴以自酌,眄庭柯以怡顏。倚南窗以寄傲,審容膝之易安。園日涉以成趣,門雖設而常關。策扶老以流憩,時矯首而遐觀。雲無心以出岫,鳥倦飛而知還。景翳翳以將入,撫孤松而盤桓。

Ah, homeward bound I go! Let me from now on learn to live alone! The world and I are not made for one another, and why drive round like one looking for what he has not found?

Content shall I be with conversations with my own kin, and there will be music and books to while away the hours. The farmers will come and tell me that spring is here and there will be work to do at the western farm.

Some order covered wagons; some row in small boats.

Sometimes we explore quiet, unknown ponds, and sometimes we climb over steep, rugged mounds.There the trees, happy of heart, grow marvellously green, and spring water gushes forth with a gurgling sound. I admire how things grow and prosper according to their seasons, and feel that thus, too, shall my life go its round.

歸去來兮,請息交以絕游。世與我而相違,復駕言兮焉求。悅親戚之情話,樂琴書以消憂。農人告余以春及,將有事於西疇。或命巾車,或棹孤舟。既窈窕以尋壑,亦崎嶇而經丘。木欣欣以向榮,泉涓涓而始流。善萬物之得時,感吾生之行休。

Enough! How long yet shall I this mortal shape keep? Why not take life as it comes, and why hustle and bustle like one on an errand bound?

Wealth and power are not my ambitions, and unattainable is the abode of the gods! I would go forth alone on a bright morning, or perhaps, planting my cane, begin to pluck the weeds and till the ground.

Or I would compose a poem beside a clear stream, or perhaps go up Tungkao and make a long-drawn call on the top of the hill. So would I be content to live and die, and without questionings of the heart, gladly accept Heaven’s will.

已矣乎。寓形宇內復幾時。曷不委心任去留。胡為乎遑遑欲何之。富貴非吾願,帝鄉不可期。懷良辰以孤往,或植杖而耘耔。登東皋以舒嘯,臨清流而賦詩。聊乘化以歸盡,樂夫天命復奚疑。

— The Importance of Living, pp.123-125, Chinese text added

***

***

Tao might be taken as an “escapist,” and yet it was not so. What he tried to escape from was politics and not life itself. If he had been a logician, he might have decided to escape from life altogether by becoming a Buddhist monk. With Tao’s great love of life, he could not have been willing to escape from it altogether. His wife and children were too real for him, his garden and the bough stretching across his courtyard and the lonely pines which he fondled were altogether too attractive, and being a reasonable man, instead of a logician, he stuck to them. That was his love of life and his jealousy over it, and it was from this positive, but reasonable, attitude toward life that he arrived at the feeling of harmony with life which was characteristic of his culture. From that harmony with life welled forth the greatest poetry in China. Of the earth and earth-born, his conclusion was not to escape from it but “to go forth alone on a bright morning, or perhaps, planting his cane, begin to pluck the weeds and till the ground” [懷良辰以孤往,植杖而耘耔]. Tao merely returned to the farm and to his family. The end was harmony and not rebellion.

— The Importance of Living, pp.125

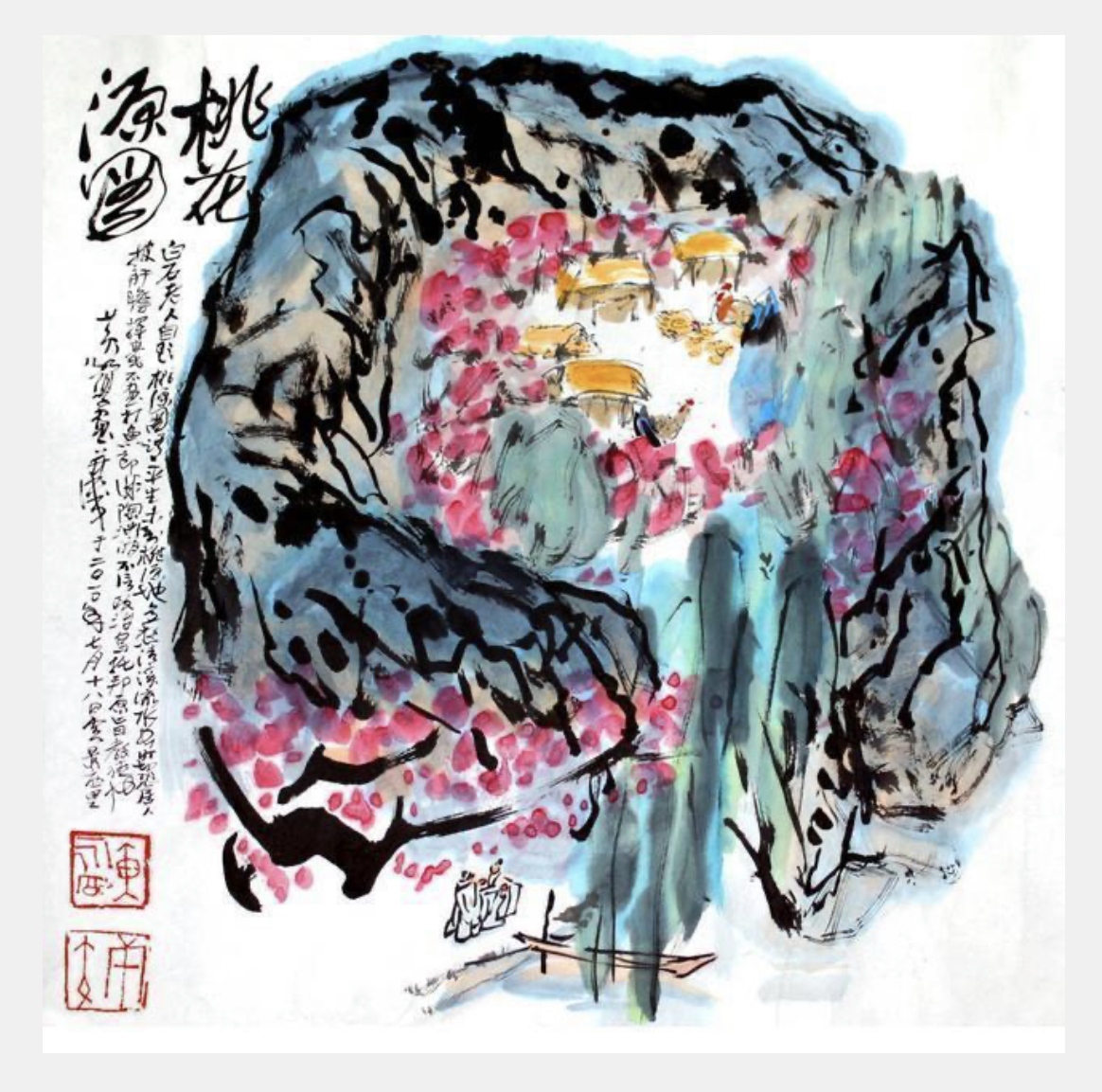

Record of the Peach Blossom Spring

translated by Cyril Birch; poetic encomium translated by J.R. Hightower

During the reign-period Taiyuan (326-397) of the Jin dynasty there lived in Wuling a certain fisherman. One day, as he followed the course of a stream, he became unconscious of the distance he had travelled. All at once he came upon a grove of blossoming peach trees which lined either bank for hundreds of paces. No tree of any other kind stood amongst them, but there were fragrant flowers, delicate and lovely to the eye, and the air was filled with drifting peach blossom.

晉太元中,武陵人,捕魚為業。緣溪行,忘路之遠近。忽逢桃花林,夾岸數百步,中無雜樹,芳草鮮美,落英繽紛。

The fisherman, marveling, passed on to discover where the grove would end. It ended at a spring; and then there came a hill. In the side of the hill was a small opening which seemed to promise a gleam of light. The fisherman left his boat and entered the opening. It was almost too cramped at first to afford him passage; but when he had taken a few dozen steps he emerged into the open light of day. He faced a spread of level land. Imposing buildings stood among rich fields and pleasant ponds all set with mulberry and willow. Linking paths led everywhere, and the fowls and dogs of one farm could be heard from the next. People were coming and going and working in the fields. Both the men and the women dressed in exactly the same manner as people outside; white-haired elders and tufted children alike were cheerful and contented.

漁人甚異之,復前行,欲窮其林。林盡水源,便得一山,山有小口,彷彿若有光。便舍船,從口入。初極狹,纔通人。復行數十步,豁然開朗。土地平曠,屋舍儼然,有良田﹑美池,桑﹑竹之屬。阡陌交通,雞犬相聞。其中往來種作,男女衣著,悉如外人。黃髮垂髫,並怡然自樂。

Some, noticing the fisherman, started in great surprise and asked him where he had come from. He told them his story. They then invited him to their home, where they set out wine and killed chickens for a feast. When news of his coming spread through the village everyone came in to question him. For their part they told how their forefathers, fleeing from the troubles of the age of Qin, had come with their wives and neighbors to this isolated place, never to leave it. From that time on they had been cut off from the outside world. They asked what age was this: they had never even heard of the Han, let alone its successors the Wei and the Jin. The fisherman answered each of their questions in full, and they sighed and wondered at what he had to tell. The rest all invited him to their homes in turn, and in each house food and wine ere set before him. It was only after a stay of several days that he took his leave.

見漁人,乃大驚,問所從來。具答之。便要還家,設酒、殺雞、作食。村中聞有此人,咸來問訊。自云:先世避秦時亂,率妻子、邑人來此絕境,不復出焉,遂與外人間隔。問今是何世,乃不知有漢,無論魏晉。此人一一為具言所聞,皆嘆惋。餘人各復延至其家,皆出酒食。停數日,辭去。

“Do not speak of us to the people outside,” they said. But when he had regained his boat and was retracing his original route, he marked it at point after point; and on reaching the prefecture he sought audience of the prefect and told him of all these things. The prefect immediately dispatched officers to go back with the fisherman. He hunted for the marks he had made, but grew confused and never found the way again.

此中人語云:不足為外人道也。既出,得其船,便扶向路,處處志之。及郡下,詣太守,說如此。太守即遣人隨其往,尋向所志,遂迷不復得路。

The learned and virtuous hermit Liu Ziji heard the story and went off elated to find the place. But he had no success, and died at length of a sickness. Since that time there have been no further “seekers of the ford.”

南陽劉子驥,高尚士也,聞之,欣然規往。未果,尋病終。後遂無問津者。

… …

Five hundred years this rare deed stayed hid,

Then one fine day the fay retreat was found.

奇蹤隱五百 一朝敞神界

The pure and the shallow belong to separate worlds:

In a little while they were hidden again.

淳薄既異源 旋復還幽蔽

Let me ask you who are convention-bound,

Can you fathom those outside the dirt and noise?

借問遊方士 焉測塵囂外

I want to tread upon the thin thin air

And rise up high to find my own kind.

願言躡清風 高舉尋吾契

***

***

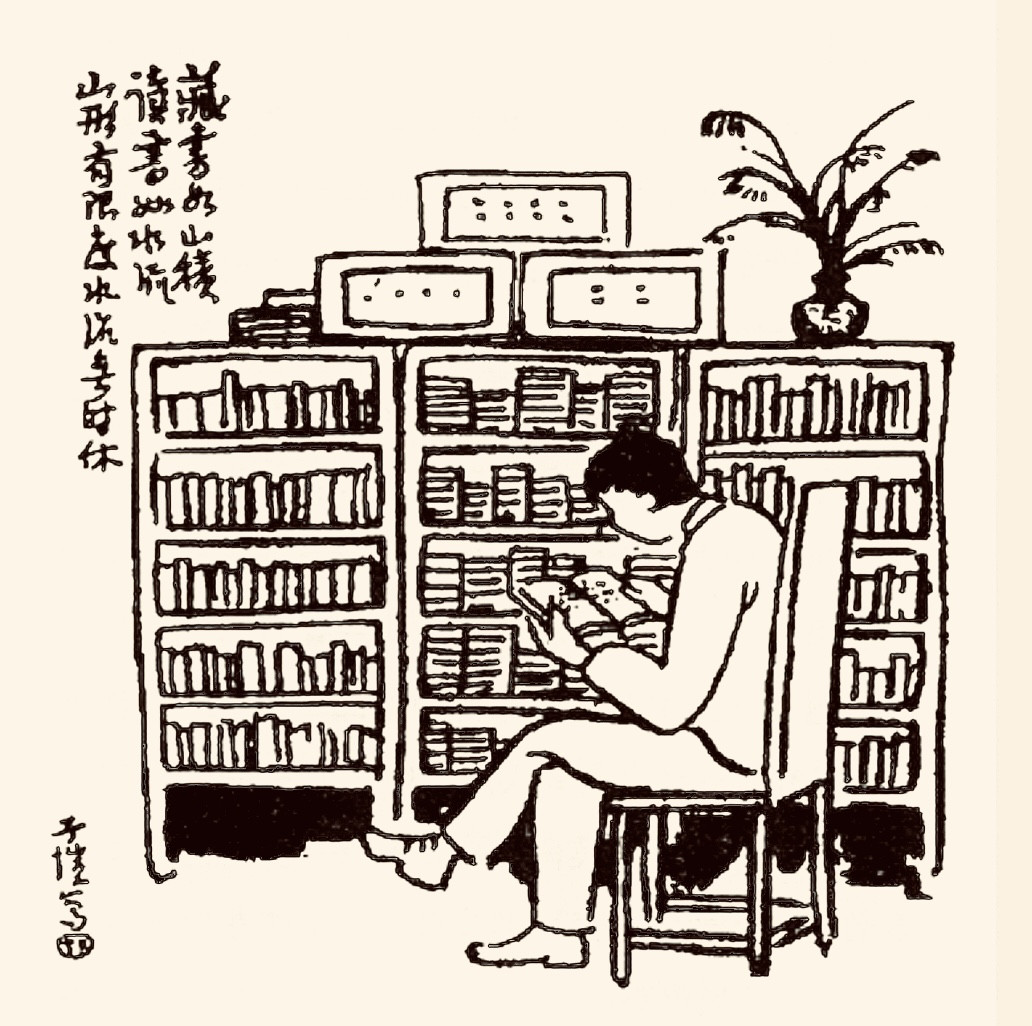

Biography of the Master of the Five Willows

Translated by Duncan Campbell

Nobody knows where the master was born, nor indeed are the details of his name at all clear. Five willow trees happened to grow besides his house and so he took them as his sobriquet. He lived a life of idle tranquillity and was a man few of words, completely uninterested in the pursuit of either wealth or fame. He loved reading books, although he never insisted on achieving a deep understanding of whatever it was he was reading; nonetheless, whenever he came across a passage that he felt spoke directly to him, his delight was such that he would neglect to eat. By nature, he was addicted to wine and yet the poverty of his family circumstances was such that his supplies were often insufficient to his needs.

Knowing that such was the case, his friends and relatives would occasionally invite him for a drink. He would arrive only to gulp down whatever was put in front of him, always intent only on becoming as drunk as possible before abruptly taking his leave, sparing not a thought for the sensibilities of his hosts. His own home was a desolate sort of place, open to the elements of sun and wind. His clothing, too, was poor and tattered, his pantry jars frequently empty. And yet he delighted in life, often writing things for his own amusement, thus giving expression to his innermost thoughts. Never devoting a single thought to considerations of profit or loss, he saw out his allotted span of life.

His encomium reads: “Qian Lou’s wife once said: ‘Be not concerned about the humbleness of your station or your poverty, do not hanker impatiently for fame and fortune.’ How excellent is her counsel. And how true of this man this was. A wine cup in hand, a poem upon his lips, such was the manner in which he brought joy to his innermost self. Was he perhaps a man of the distant age of Wuhuai or of Getian?”

五柳先生傳

先生不知何許人也,亦不詳其姓字,宅邊有五栁樹,因以為號焉。閑靜少言,不慕榮利。好讀書,不求甚解;每有會意,便欣然忘食。性嗜酒,家貧不能常得。親舊知其如此,或置酒而招之,造飲輒盡,期在必醉;既醉而退,曾不吝情去留。環堵蕭然,不蔽風日;短褐穿結,簞瓢屢空,晏如也。常著文章自娛,頗示已志。忘懐得失,以此自終。贊曰:黔婁之妻有言:不戚戚於貧賤,不汲汲於富貴。極其言,兹若人之儔乎。酣觴賦詩,以樂其志,無懐氏之民歟。葛天氏之民歟。

[Note: For a contemporary adaptation of ‘Mr Five Willows’, see Bai Jieming 白杰明 (Geremie R. Barmé), Six Chapters — One Hundred and Twenty Years, China Heritage, 1 January 2020.]

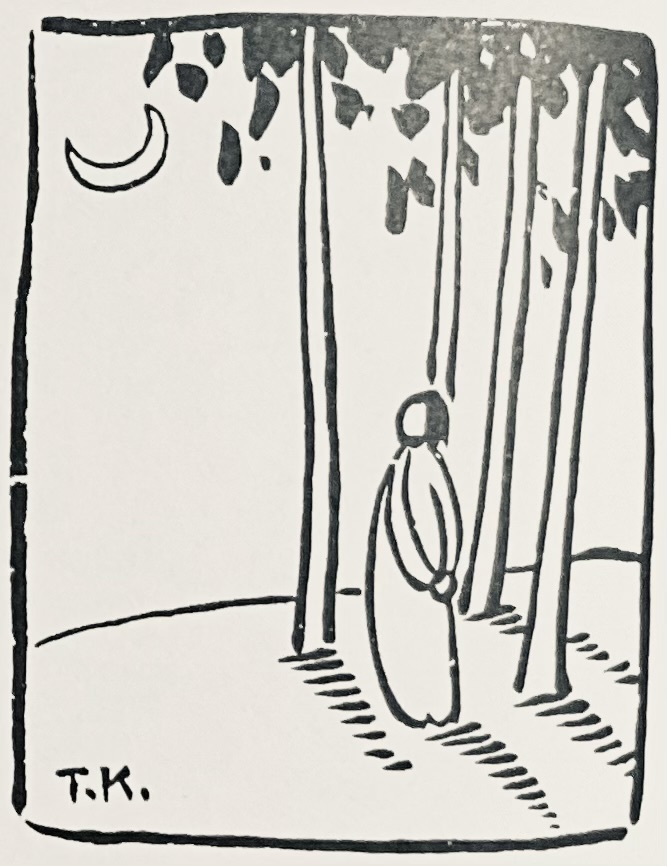

Tao Yuanming and Feng Zikai

***

As mentioned earlier, An Artistic Exile, my biography of Feng Zikai (豐子愷, 1897-1975), begins by referring to Tao Yuanming’s idyllic vision of untrammelled rural life. It ends as follows:

… perhaps, Zikai no longer appears to the mainstream culture of China and Taiwan as a fringe figure of marginal interest. Rather, many readers now find in his work a spirit that has outlasted the evanescent changes of politics and the uncertainties wrought by economic weal and bane. In his exile, the condition of all humanity, many have come to recognize their own state of being, and in his work some find solace and—as Feng would put it—a temporary escape from the suffering, anger, belligerence, and sorrows of the transient world. The artistic exile of Feng Zikai defined much of his life and activities. It is in the world of his art and writing, however, that a permanent road back to his realm can be found by any who choose to seek it out.

When the lone fisherman who happened upon the peaceful rustic world described in Tao Yuanming’s record of the Peach Blossom Valley returned to the strife and turmoil of his own day, he thought that the place could be recovered whenever he needed to return. When others followed the fisherman’s instructions in search of the valley, however, they could never find the path:

At once it became again secret and secluded.

Let me ask you who are convention-bound,

Can you fathom those outside the dirt and noise?

I want to tread upon the thin thin air

And rise up high to find my own kind.

… 旋復還幽蔽

借問遊方士 焉測塵囂外

願言躡清風 高舉尋吾契

— An Artistic Exile, 2002, pp.373-374

[Note: For more on Feng Zikai in The Tower of Reading, see Inspiration & Taste — considering ‘On the Spur of the Moment’.]

Pines and Chrysanthemums Remain

“The three paths are almost obliterated / But pines and chrysanthemums are still here!” 三徑就荒,松菊猶存 With this exclamation of recognition and pleasure, Tao stepped back onto the grounds of his property early in his prose poem “Returning Home” 歸去來兮辭, an account of his personal odyssey, a manifesto of the values of rustic reclusion, and one of the most famous texts in Chinese literature. He had just resigned from his job—a minor post in the government bureaucracy, away from home—and was now resolved to spend the rest of his days in his well-loved garden. The garden is a pervasive presence in his poetry: haven from society and the contentious political scene of the day, stimulus and metaphor for his thoughts about self, nature, destiny, and the mortal condition. “How easy it is,” he wrote, “to be content with a little space.”

— Susan E. Nelson, Revisiting the Eastern Fence: Tao Qian’s Chrysanthemums, p.440, Chinese characters added