Viral Alarm

The 4th of May 2020 marked the one-hundred and first anniversary of the May Fourth demonstrations in Beijing 1919. Commemorations of that event, and the era to which it has given a name, at a time when the world is stricken by Covid-19 pandemic has given ideologues of various persuasions, and different climes, a particular opportunity. The China Heritage series ‘Viral Alarm’ offers an ongoing meditation on the coronavirus, its significance in the Chinese world, as well as its impact on China in the world. In this chapter we feature two online May Fourth commemorations which chime both with the events of 1919 and the political and social exigencies of 2020.

As a child of May Fourth myself — I was born on 4 May 1954 — added to the fact that my adult years have, for the most part, been involved with a study of the Chinese world, it is hardly surprising that date has been as inescapable as it has been significant. Indeed, I first became aware of the ‘palimpsest of May Fourth’ in my own history when, around the time of my fifteenth birthday in 1969, I first read Mao Zedong’s essay on the subject written thirty years earlier. Twenty years later, I would submit a doctoral dissertation completed under the supervision of Pierre Ryckmans (Simon Leys) that dealt, in the main part, with the May Fourth era and its mixed cultural and political legacies.

Previously, China Heritage has marked the May Fourth anniversary in various ways. See:

- ‘May Fourth at Ninety-nine’, 4 May 2018; and,

- ‘Anniversaries New & Old in 2019 — Remembering 5.4, Accounting for 4.28’, 4 May 2019

Even before that, in 2014, it featured in the history of The Australia Centre on China in the World, of which I was the founding director (see ‘CIW — Opening a Building’.)

***

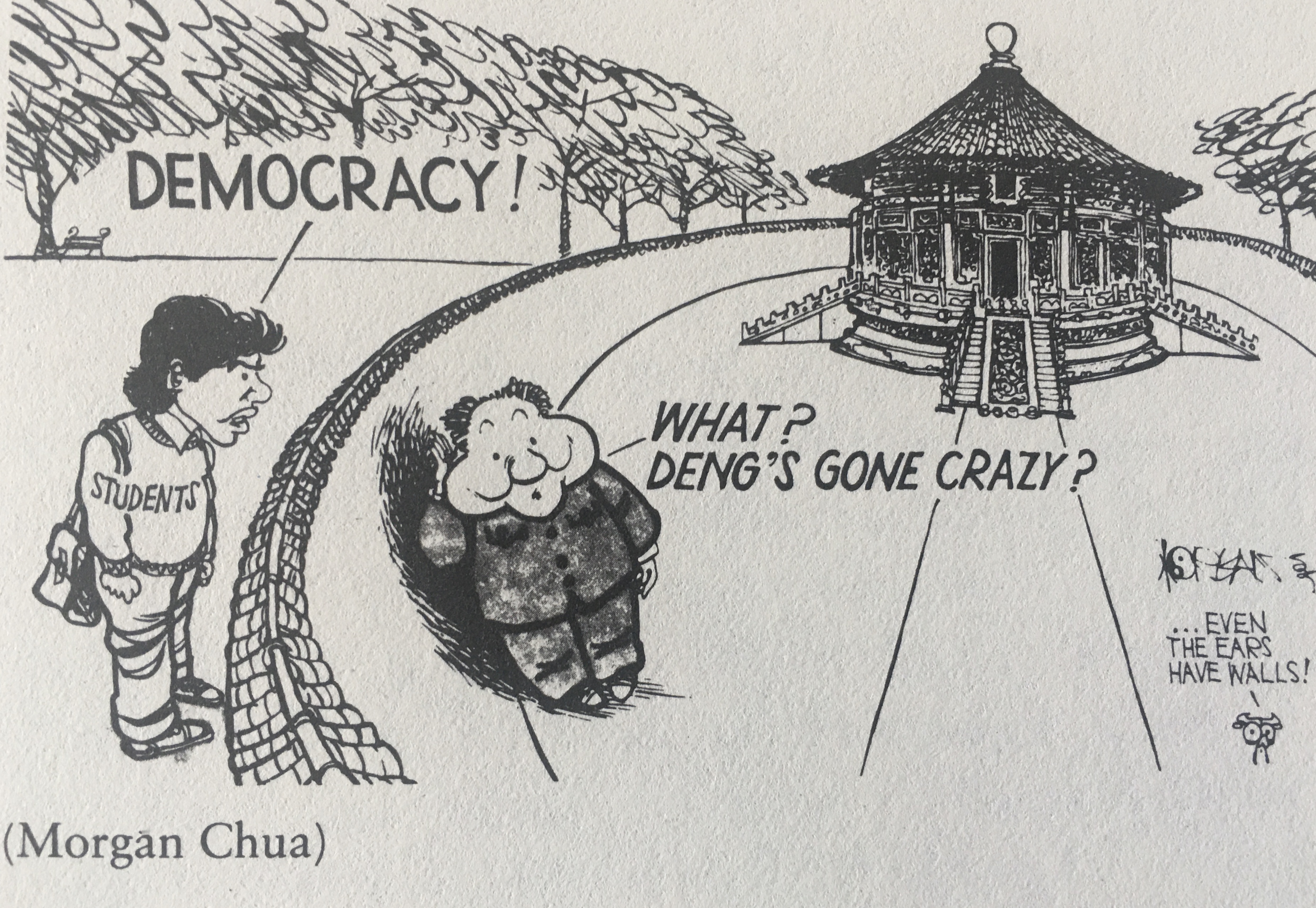

May Fourth 2020 has turned out to be another red-letter anniversary, one on which issues that have bedeviled China for over a century, and that have also been a spectre haunting the Sino-US relationship for the entire history of the People’s Republic, enjoyed a clarifying moment in the spotlight. In commemorating 4 May 2020, we discuss two very different messages delivered on the day to Young China. The first, created by a commercial video-sharing website in Shanghai, took the form of ‘agitprop-advertising’. The other was a ‘spot-off’ claim on the hearts-and-minds of China’s youth released as a recorded lecture in Standard Chinese from a White House that is the viral epicentre America’s politics of self-destruction. That someone, anyone, at the Trump White House would have the gall to lecture anyone else about ‘Mr Democracy’ and ‘Mr Science’ — those twin tutelary spirits of May Fourth 1919 — at the height of America’s coronavirus crisis was simply beyond satire. It was not, however, above critique.

The May Fourth messages both from Beijing and Washington despite their specific displays of bombast, hyperbole and self-delusion demonstrated just how much the contending great powers share in common, albeit often unconsciously. They also offered a Kafkaesque backdrop to the festive spirit of Zoomed-in birthday drinks and familial conviviality that I was able to enjoy in rural New Zealand.

***

‘Mangling May Fourth 2020’ is published in two parts under separate headings. In Part One — ‘Mangling May Fourth 2020 in Beijing’ — we cast a gimlet eye on events in Beijing. In Part Two part we invite readers to turn their gaze towards the topsy-turvy world to the Far East, and to Washington.

‘Viral Alarm’ is the theme of China Heritage Annual 2020. For a table of contents and links to other chapters in the series, see here. This essay is also a Lesson in New Sinology. as well as constituting another chapter in ‘Watching China Watching’.

The following observations and comments on Deputy US National Security Advisor Matt Pottinger’s 4 May 2020 ‘Reflections on China’s May Fourth Movement: an American Perspective’ are prefaced by an extended consideration of some aspects of the Sino-American relationship. This chapter of ‘Viral Alarm’ also draws on work that has previously appeared in China Heritage. It is composed in the style of ‘stopgap comments’, 補白 bǔbái, of the kind that Lu Xun published in 1925. ‘Stopgap comments’ or ‘gap-filling remarks’ are used to make up for editorial lacunæ or to indicate short pieces of prose or whimsy.

— Geremie R Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

14 May 2020

***

- (Note: For the Chinese text of Mr Pottinger’s speech, see here; and for the English, here. The official video can be seen here. The English text is also reproduced at the end of our comments.)

***

Gentle Reader:

Since I lack the politesse of my American friends and colleagues, the Antipodean muckraking that follows may prove to be unseemly to some readers. Delicate eyes are advised to go no further.

— GRB

***

As we noted in part one of this double May Fourth commemoration — ‘Mangling May Fourth 2020 in Beijing’ — the official Chinese Communist Party interpretation of the events of 1919 was formalised by Mao Zedong in his 1939 speech and for eighty-one years that dogma has been officially upheld, even if it has been the repeated subject of debate and contestation in the non-Party Chinese world.

Thus, it was no surprise that Official China responded to Matthew Pottinger’s May Fourth oration in predictably stilted fashion.

***

At a regular press conference on 6 May, Hua Chunying, one of a troika of increasingly abrasive Foreign Ministry wolf-warrior spokespeople, responded to a Dorothy Dixer posed by a journalist from The Global Times. Hua’s remarks are worth reproducing here as part of our archive of ‘May Fourth memories’:

Global Times: ‘US Deputy National Security Advisor Matt Pottinger in remarks to the Miller Center at the University of Virginia on May 4 said that “the heirs of May Fourth are civic-minded citizens”. I wonder if you have a comment on this?’

Hua Chunying: ‘This US official may think he knows China very well, but as we can see from his remarks, he doesn’t really understand China or the May Fourth spirit, because he’s strongly biased against China.

‘Mr. Pottinger was wrong in calling the May Fourth Movement a populist movement. The movement is a great patriotic revolution against imperialism and feudalism at a crucial moment for the Chinese nation. Patriotism is at its very core. And patriotism runs in the veins of the Chinese nation. The true heirs of the movement today are Chinese citizens with a patriotic heart. In this new era, carrying forth the May Fourth spirit means working for the building of a strong modern socialist country and realizing the great renewal of the Chinese nation. That is what being true civic-minded citizens means today. In the face of COVID-19, the Chinese people, united as one, fought a hard battle with extraordinary courage and perseverance, securing major success in containing the virus. This is the most vivid illustration of the May Fourth spirit.

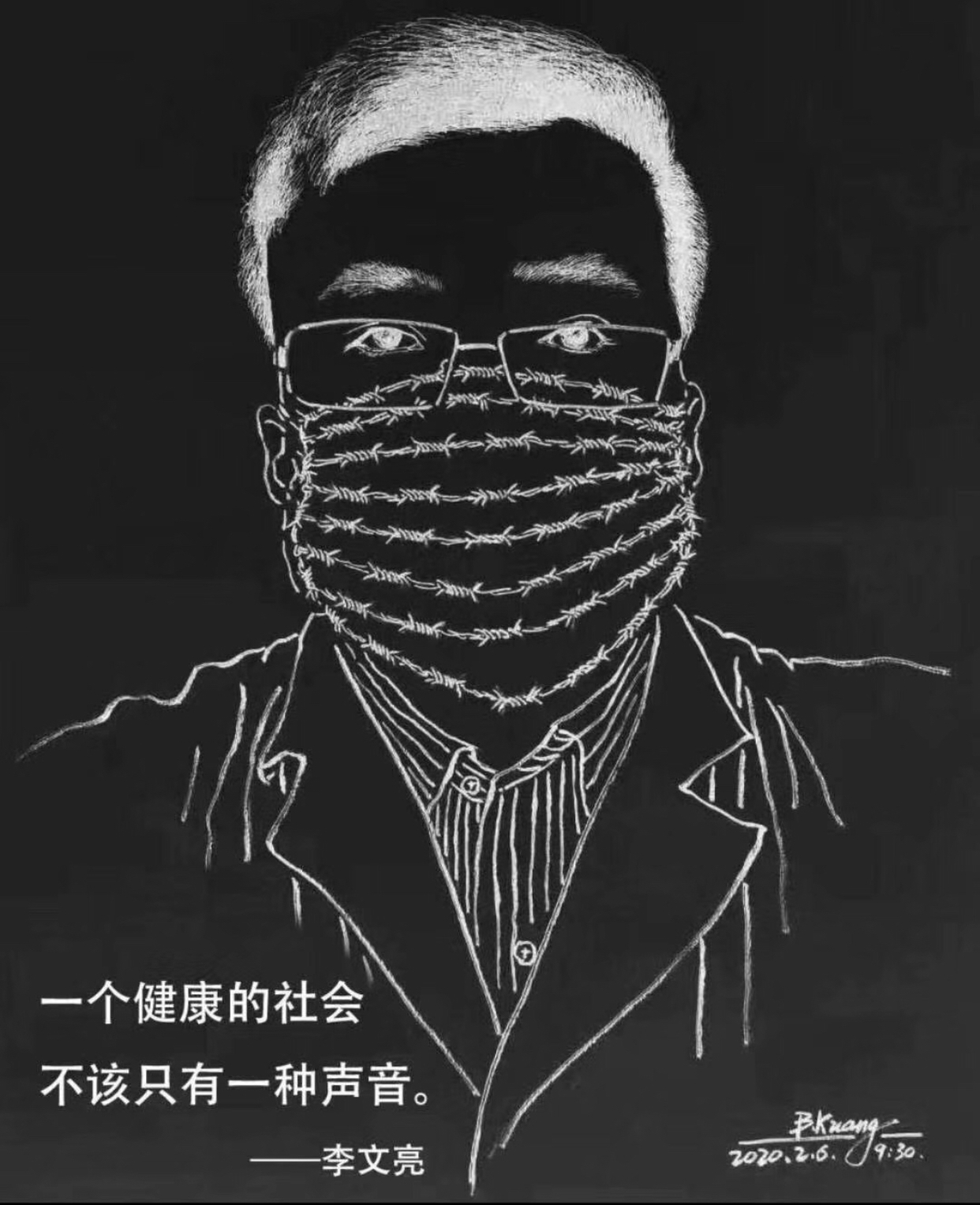

‘Perhaps Mr. Pottinger forgot what triggered the May Fourth Movement. It was because foreign powers were trading their privileges in Chinese territory at the Peace Conference in Paris after World War I, and the Chinese people would never accept such loss of rights and national humiliation. Today, 101 years from then, if there are still people in Washington who want to act like bullies and pin the blame on China to get away with their poor handling of COVID-19, the 1.4 billion Chinese people will never allow it. The late Dr. Li Wenliang would never allow it.

‘We advise US officials to learn more about Chinese history and mind their own business.’

In an account of this exchange published the same day, The Global Times added the sentiments of Zhang Yiwu 張頤武, a tenured Peking University lickspittle who can be relied on for an ill-honed quote:

‘Pottinger’s speech showed some US people still have the fantasy of disturbing China by causing confrontations and clashes within the country. They want to stir young people to seek so-called US democracy and cause domestic turbulence to interrupt China’s development, Zhang Yiwu, a professor from Peking University, told the Global Times.

‘ “But his distorted interpretation of the May Fourth Movement has not only been mocked by Chinese people but also exposed his incomprehension of Chinese youths and society,” Zhang said, noting Pottinger purposely neglected to say that the May Fourth Movement was a patriotic campaign, and he stressed several times that the movement was criticized by some people for being “unpatriotic” and “pro-American,” which made his political purpose so obvious.’

***

***

Needless to say, for Mr Pottinger and friends such run-of-the-mill obloquy was par for the course. As is so often the case when Official China lambasts the American imperium and its hauteur, however, the mockery was not totally baseless. Yet, like the distorting Party clichés about the May Fourth movement itself, the official Chinese line on the historical choices and desires of ‘the Chinese people’ are as disingenuous today as they were in the late 1940s when the Communists fought, cajoled and lied their way into power (for details, see below and, for an anthology of the numerous formal pledges made publicly by Party leaders regarding electoral democracy, human rights, free speech and so on to the Chinese nation in the years prior to the founding of the People’s Republic, see Xiao Shu 笑蜀, ed., The Voice of History — Solemn Promises of the 1940s 歷史的先聲——半個世紀前的莊嚴承諾, 汕頭大學出版社, 1999).

In 2020 such discomfort was exacerbated by the fact that apart from following an unsurprising script by casting the May Fourth era in terms of American influence, values and history, Pottinger’s speech also presented listeners with some on-brand, indulgent Trump-era self-congratulation, while inducing formication in some listeners. Below we offer some background to the occasions and a rather lengthy series of comments on Pottinger’s oration.

As for the hubristic claims made by Beijing, along with the continued repression of independent voices and civilian life in that country, see an overview compiled by Josh Rudolf in China Digital Times:

- ‘Top-Down Hooliganization, from Propaganda to Diplomacy (CDT Censorship Digest, April 2020)’, 5 May 2020

As for the obverse, that is, the Trump administrations ‘blame-Beijing’ strategy, see:

- Julian Borger, ‘US uses coronavirus to challenge Chinese Communist party’s grip on power’, The Guardian, 4 May 2020;

- Kevin Rudd, ‘The Coming Post-COVID Anarchy’, Foreign Affairs, 6 May 2020; and,

- Evan Osnos, ‘The Folly of Trump’s Blame-Beijing Coronavirus Strategy’, The New Yorker, 10 May 2020

- Chris Buckley and Steven Lee Myers, ‘From “Respect” to “Sick and Twisted”: How Coronavirus Hit U.S.-China Ties’, The New York Times, 15 May 2020

An Inconvenient Reality

‘The President and at least some of his most fervent supporters appear now to be in the lying-to-yourself-and-believing-it stage of the pandemic. Truth has become so inconvenient that it’s better left aside for some alternate, less inconvenient reality.’

Susan B. Glasser, ‘Has Trump Reached the

Lying-to-Himself-and-Believing-It Stage?’

The New Yorker, 8 May 2020

***

***

The Sino-American Danse Macabre

In recent years, when I have had the pleasure to address academic and general audiences in America, I have found solace that, given the particular political constellation formed by the administration of Donald Trump, the Republican majority in the US senate and the slanted configuration of the Supreme Court, one’s American cousins are now better placed than at any time in recent memory to understand the outrage, the frustrations and the hopelessness that men and women of conscience and basic decency experience in China on a daily basis. In the American case that slow-moving lava of anger is further excited by an Attorney General who promotes the overreach of executive authority and by the Murdoch and right-wing media claques which cheer on every new absurdity. The exceptionalism of both China and America now echoes with an ever-greater hollowness.

Those of us who are inextricably involved with both of those nations while living, for the most part, on the periphery of these cheek-by-jowl empires, have long witnessed a decades-long ‘apache dance’. For me, the contemplation of that fluid, constantly-transmuting dialectic brings to mind the description of the come-hither performances witnessed in the New York art world as described by Tom Wolfe in The Painted Word (1975):

‘The artist was like the female in the act, stamping her feet, yelling defiance one moment, feigning indifference the next, resisting the advances of her pursuer with absolute contempt … more thrashing about … more rake-a-cheek fury … more yelling and carrying on … until finally with one last mighty and marvelously ambiguous shriek — pain! ecstasy! — she submits … Paff paff paff paff paff … How you do it, my boy! … and the house lights rise and Everyone, tout le monde, applauds …’

In recent times, that bilateral gyration is more reminiscent of a danse macabre, the dance of death that flourished as an idea, a cultural trope and a reality in the late middle ages. During an era when war, pestilence and poverty might visit a cruel fate upon anyone at any time, the danse macabre was a reminder and warning, as well as a form of comic relief that was performed as a memento mori — a reminder that we all die. The danse macabre helped the living face the inevitable even as they dealt with the horrors of the day. As part of the dance, the cadaverous messengers of Death were unequivocal:

Quod fuimus, estis; quod sumus, vos eritis

‘What we were, you are; what we are, you will be’

***

A Haunting Past

For those in Asia and the Pacific, apart from irregular periods of uplift, since the late 1940s the Sino-American relationship has just as often been a threnody as it has been a panegyric. On 4 May 2020, we were reminded of two significant moments in that history that, although not manifestly relevant to understanding Mr Matt Pottinger’s ex cathedra remarks from the White House, are crucial nonetheless to locating them in the context of the US and China, yesterday and today.

The first of these unwelcome memories relates to August 1949 when, on the eve of the Communist victory on the Chinese mainland, the US Department of State released a ‘China White Paper’, the full title of which was United States Relations With China, With Special Reference to the Period 1944–1949. The White Paper was prefaced by a ‘Letter of Transmittal’, titled ‘A Summary of American-Chinese Relations’, composed by Dean Acheson, the US Secretary of State to President Harry Truman and dated 30 July 1949. Acheson noted that:

‘[N]ow it is abundantly clear that we must face the situation as it exists in fact. We will not help the Chinese or ourselves by basing our policy on wishful thinking. We continue to believe that, however tragic may be the immediate future of China and however ruthlessly a major portion of this great people may be exploited by a party in the interest of a foreign imperialism [that is, the Soviet Union], ultimately the profound civilization and the democratic individualism of China will reassert themselves and she will throw off the foreign yoke. I consider that we should encourage all developments in China which now and in the future work toward this end.’

— quoted in ‘White Paper, Red Menace’

China Heritage, 17 January 2018

As we noted in ‘White Paper, Red Menace’:

‘Among the devastating consequences of the White Paper and Dean Acheson’s “Letter of Transmittal” is that for Mao and his fellows they confirmed in no uncertain terms the long-term danger posed to a Communist party-state by “democratic individualists” 民主個人主義, that is men and women trained in or sympathetic to Western values, politics, economic thinking and scholarship. In his response to the White Paper, Mao named a few of the best known pro-West public figures, such as Hu Shih (胡適, 1891-1962), a celebrated academic and the Chinese Republic’s ambassador to Washington from 1938 to 1942.’

***

***

Evolving, But Not So Peacefully

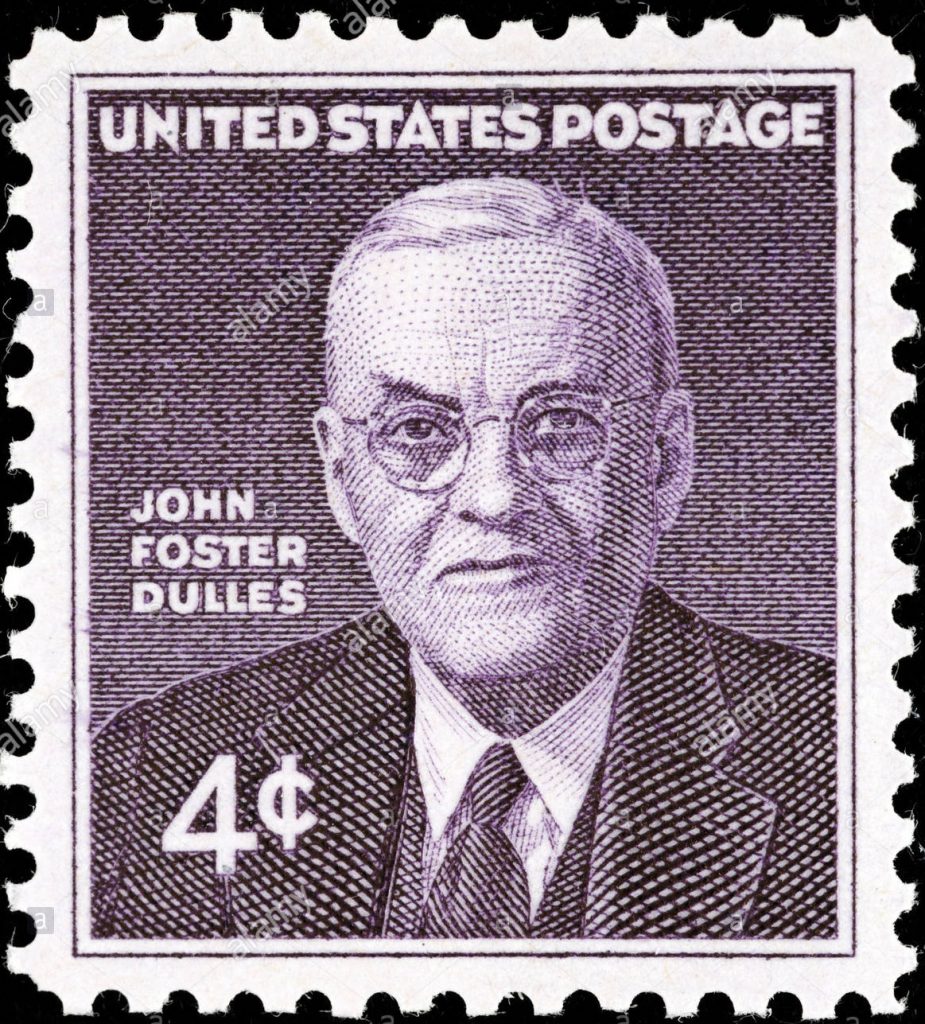

A second moment of historical significance for our present contemplation of 4 May 2020 dates from the 1950s. During that crucial decade, John Foster Dulles (1888-1959), along with his brother Allen Welsh Dulles (1893-1969), the first civilian director of the CIA, both of whom had long melded US corporate interests with the national interest, drove the interventionist foreign policy of the United States. (As John Foster Dulles once put it: ‘For us, there are two kinds of people in the world. There are those who are Christians and support free enterprise, and there are the others.’) Their baleful influence and contributions to the ideas and practice of ‘American Exceptionalism’ continue to cast a deathly shadow today. (See Stephen Kinzer, The Brothers: John Foster Dulles, Allen Dulles, and Their Secret World War, New York, 2013.)

In 1957, President Dwight Eisenhower introduced a policy of ‘peaceful conquest’ or ‘peaceful evolution’ in relation to the Soviet Union, the Eastern Bloc, as well as the People’s Republic of China. Put simply, it was a multi-faceted policy aimed at undermining from within the systems of socialist nations by ‘spreading Western political ideas and lifestyles, inciting discontent, and encouraging groups to challenge the Party leadership. ‘

The matrix of ‘peaceful evolution’ strategies was coordinated and promoted by John Foster Dulles. Mao Zedong followed Dulles’s pronouncements with forensic interest and even had documents related to ‘peaceful evolution’ speedily translated with commentary. He studied and critiqued Dulles’s own speeches word-by-word with the aid of an English dictionary. (Mao focussed on three speeches in particular: ‘Policy for the Far East’, which Dulles delivered before the California Chamber of Commerce on 4 December 1958; testimony made before the House Foreign Affairs Committee on 28 January 1959; and, ‘The Role of Law in Peace’, a speech which Dulles delivered to the New York State Bar Association on 31 January 1959.)

As Qiang Zhai, an expert in Cold War history, has noted in his work on the Chinese Communist Party elder Bo Yibo’s 薄一波 reflections on ‘peaceful evolution’:

‘The years 1958-1959 were a crucial period in Mao’s psychological evolution. He began to show increasing concern with the problem of succession and worried about his impending death. He feared that the political system that he had spent his life creating would betray his beliefs and values and slip out of his control. His apprehension about the future development of China was closely related to his analysis of the degeneration of the Soviet system. Mao believed that Dulles’s idea of inducing peaceful evolution within the socialist world was already taking effect in the Soviet Union, given Khrushchev’s fascination with peaceful co-existence with the capitalist West. Mao wanted to prevent that from happening in China. Here lie the roots of China’s subsequent exchange of polemics with the Soviet Union and Mao’s decision to restructure the Chinese state and society in order to prevent a revisionist ‘change of color’ of China, culminating in the launching of the Cultural Revolution in 1966. Mao’s frantic response to Dulles’s speeches constitutes a clear case of how international events contributed to China’s domestic developments. It also demonstrates the effects of Dulles’s strategy of driving a wedge between China and the Soviet Union.’

In my own 2009 editorial introduction to Qiang’s work I offered a short update to the effect that:

‘Since the initiation of the Reform era some three [now over four] decades ago, the Party’s policy on Peaceful Evolution has effectively been evacuated of its earlier pro-socialist ideological content. What remains is a theoretical justification sanctioned by both Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping for a nationalism (or ‘Chinese particularism’) wedded to authoritarian one-party politics. Deng and his colleagues were quick to blame the United States and other countries for politically manipulating the 1989 Protest Movement and attempting to use civil unrest in China to turn the country into a “bourgeois vassaldom” of the West. This “plot” aimed at encouraging China to evolve peacefully into a democracy dependent on international capital was supposedly the continuation of a struggle in which China’s Communist Party had been engaged since the late 1950s. Ironically, Deng’s internal Party opponents subsequently used the theory of Peaceful Evolution to oppose the next, bolder economic reforms that were initiated in 1992. We should note that the Party’s anxiety over Peaceful Evolution still informs many of its political, social, cultural and media policies.’

— editorial introduction to Qiang Zhai,

‘1959: Preventing Peaceful Evolution’

China Heritage Quarterly (June 2009)

(Note: see also:

- ‘China’s Promise’, China Beat, 20 January 2010; and,

- ‘The Harmonious Evolution of Information in China’, China Beat, 29 January 2010)

As Bo Yibo remembered it:

‘In his meeting with Kapo and Balluku of Albania on February 3, 1967, Mao contended: At the “Seven Thousand Cadres Conference” in 1962, “I made a speech. I said that revisionism wanted to overthrow us. If we paid no attention and conducted no struggle, China would become a fascist dictatorship in either a few or a dozen years at the earliest or in several decades at the latest”.’

***

When considering Matt Pottinger’s May Fourth remarks in the era of the Sino-American ‘Chilly War’ (not to mention America’s ‘Forever Cold Civil War’), I would suggest that it is worth recalling moments, and policies, like these, as well as familiarising oneself with documents that reflect the thinking of the time, be it in the United States or in China. History should not be regarded as being bunk when its dynamics underlie present gambits. Moreover, historical moments, as well as literary monuments, are integral to The China Story as told by leaders from Mao through Deng Xiaoping to Xi Jinping, just as counter-narratives loom equally large in the case that some Americans make for themselves.

***

Ressentiment of The Disappointed

Apart from the above lessons from recent ‘ancient history’, Mr Pottinger’s remarks brought to mind observations made when we updated our work on Chan Koonchung (陳冠中, b.1952), the Hong Kong-Beijing author of The Fat Years in early 2019. At that time, I observed that:

‘Since the rise of Xi Jinping in late 2012, it has been a commonplace for The Disappointed — that is, a disparate group of the powerful, the influential and the opinionated scattered both within and outside China — to bewail how the leader has reasserted Party power and encouraged in the People’s Republic a more muscular regional and global stance.

‘The Disappointed have been confronted, and affronted, by what is now dubbed China’s ‘authoritarian turn’. To reverse a well-known expression, one has the impression that The Chinese People (albeit the un-elected representative of the People, the Communist party-state) have hurt their feelings!

‘The Disappointed can be thought of as those “China Hands” nostalgic for beliefs and hopes that were predicated on a range of economic, political and cultural assumptions, along with a kind of condescension that smacked of colonial hauteur. That is to say, in their obsessive focus on neo-liberal economic goals along with unquestioned presumptions about globalisation they — be they politicians, analysts, business people, academics, journalists or a host of others, including Chinese factional players — repeatedly ignored or underestimated what the Party and its theoreticians (along with fellow-travelling academic New Marxists) were saying, thinking and actually doing. Too often this encouraged a purblind belief in immutable historical and economic forces that supposedly predetermined China’s path forward. Such near-burlesque confidence — which, in many respects, mirrored the dogmatic historical determinism of the Communists themselves — has been challenged by significant changes in official policy and rhetoric over recent years.

‘Readers familiar with our publications, and of views that date back to the early 1980s, will be aware that a number of “inflection points” in post-1978 history long foretold the possibility of the kinds of changes that have been witnessed under Xi Jinping and Wang Qishan. In this 2019 anniversary year, we would do well to recall three such moments:

- March 1979: the dissident Democracy Wall activist Wei Jingsheng posted his essay ‘Do We Want Democracy or New Autocracy?‘ 要民主還是要新的獨裁 leading to his arrest and long-term imprisonment. Wei’s poster was followed a few days later by the announcement of the Four Basic Principles 四項基本原則, ‘core Party values’ that have remained at the heart of the one-party state, its Constitution and its draconian rule ever since;

- January 1987: following student demonstrations in favour of media freedom in late 1986, the ouster of Hu Yaobang, Communist Party General Secretary, and the purge of dissenting Party members who championed ‘bourgeois liberalisation’, that is who advocated political reform, a free media along with intellectual and cultural pluralism. These events reflected an on-going political and ideological contest that resulted in

- June 1989: the fall of Zhao Ziyang, the Beijing Massacre and Deng Xiaoping’s re-affirmation of the dangers of Western-led attempts to encourage ‘peaceful evolution’, that is a policy first championed by the United States in the late 1950s aimed at encouraging socialist countries like China to abandon one-party dictatorships in favour of citizens’ rights and constitutional democracy.

‘Even for the latecomers, in particular from the 2007-2008 Olympic Year, it was evident that the People’s Republic was leaning further in to its noxious brand of authoritarianism. This too was a significant “inflection point”, and Chan Koonchung addressed it perceptively. …

‘Only now are The Disappointed fitfully catching up with four decades of reality, not to mention the last decade of China’s “prosperous age”, and all that it truly entails.’

— from my introduction to ‘Sic transit gloria mundi

— Ten Years of a Prosperous Age’, 14 February 2019

***

Mangling May Fourth in Washington 2020

On 4 May 2020, Matthew Pottinger (in Chinese 博明, alternatively 馬修·波廷格 , 1973-), the United States Deputy National Security Advisor, addressed via video link an audience at the Miller Center at the University of Virginia. Apart from its noteworthy content, the speech was significant in that it was delivered by a senior White House official in Standard Chinese.

Over the years, Mr Pottinger, with whom I have had friendly exchanges, may well have performed many meritorious acts behind the scenes and beyond media or public scrutiny, but there can be no doubt that he is also a willing participant in and apologist for decisions made by the administration of President Donald Trump — many of which have been articulated by Vice President Mike Pence and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo — that, despite some comely rhetoric, have in fact and in effect undermined long-term American interests in dealing with today’s China. In particular, one thinks of the expulsion of journalists in March 2020 , participation in the attempts to pressure intelligence agencies to gather information about the possible origins of the coronavirus in a Wuhan lab, as well as the decision to cut US funding to the WHO during the pandemic, all of which Pottinger is said to have been involved (see, for example, David Nakamura, Carol D. Leonnig and Ellen Nakashima, ‘Matthew Pottinger faced Communist China’s intimidation as a reporter. He’s now at the White House shaping Trump’s hard line policy toward Beijing.’, The Washington Post, 30 April 2020; and Mark Mazzetti, Julian E. Barnes, Edward Wong and Adam Goldman, ‘Trump Officials Are Said to Press Spies to Link Virus and Wuhan Labs’, The New York Times, 30 April 2020).

In the following essay, the second part of our commemoration of May Fourth 2020, we suggest that is difficult to avoid thinking about American policy bombast as being integral to a kind of ‘lying-to-yourself-and-believing-it’ syndrome. Our stance is averse to what is often lazily dismissed as ‘cultural relativism’, nor does it in any way deny the realities of the Chinese People’s Republic — something that has, for the present writer, been a major focus of a lifetime of work. In fact, it is for this very reason I believe that a major speech in Chinese regarding a significant national anniversary made by a leading official in the White House calls for a measure of New Sinology scrutiny. Having contributed to a speech presented in Chinese by a prominent Australian politician — the then-prime minister Kevin Rudd — to a student audience at Peking University, that latter-day and much-diminished May Fourth bastion, I feel adequate to the task. (Note: (see ‘Contentious Friendship’, China Heritage, 29 April 2018. Also, the main campus of the pre-1949 Peking University was located at Shatan’er in central Beijing/ Beiping. It took over the elegant grounds of Yenching University during the Soviet-style restructuring of China’s tertiary institutions in 1952.)

***

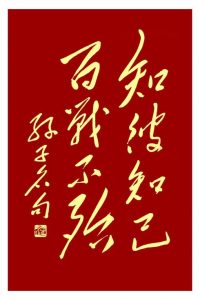

Know Thyself Primer

— a vade mecum for the Sino-American danse macabre

For China Heritage, Matt Pottinger’s May Fourth speech offers a ‘teachable moment’. To that end, we intersperse our comments on the speech itself with a modest new venture titled Know Thyself Primer 知己知彼語彙. In a number of mini-lessons we provide a selection of commonplace Chinese aphorisms and terms that, we believe, may be useful both to policy wonks and strategists like Mr Pottinger as well as others who, although they may have with less volatile agendas, have to wrestle either with the Trump administration or the People’s Republic, or indeed with both. For less engaged readers, Know Thyself Primer may prove to be a thumbnail guide to the linguistic landscape of resistance from a civilisation that has been burdened by (and self-generated) an autocracy for well over two millennia.

Below, we offer initial excerpts from Know Thyself Primer. Future entries, which contribute to the ongoing China Heritage series Lessons in New Sinology, will appear as the occasion arises. We would also recommend:

- The China Expert and The Ten Commandments — Watching China Watching (I), China Heritage, 5 January 2018

- Non-existent Inscriptions, Invisible Ink, Blank Pages — Watching China Watching (II), China Heritage, 7 January 2018

- On New China Newspeak 新華文體 — Watching China Watching (III), China Heritage, 9 January 2018

As well as:

- Karin Malmstrom & Nancy Nash, ‘The Man With the Key Is Not Here’ 管钥匙的人不在, a China Heritage reprint

— The Editor

***

Know Thyself Primer

Exordium

In his May Fourth speech, Matthew Pottinger mentions a number of unofficial journalists whose activities have featured in ‘Viral Alarm’: Chen Qiushi, Fang Bin, Li Zehua (see ‘The Heart of The One Grows Ever More Arrogant and Proud’, 10 March 2020). He follows this roll call with the laudable, if somewhat hopeful, averment that: ‘When small acts of bravery are stamped out by governments, big acts of bravery follow.’ Mr Pottinger then speaks about the ‘big acts of moral and physical courage’ reflected in the outspokenness of people like Xu Zhangrun, Ren Zhiqiang, Xu Zhiyong and Fang Fang, again, all of whom feature in our China Heritage Annual 2020. (For an extended comment on this section of Pottinger’s speech, see the section ‘Whistleblowers’ below.) Our readers will be familiar with the daring outspokenness of Professor Xu Zhangrun of Tsinghua University since his work has been a particular focus of our work since July 2018, when he published ‘Imminent Fears, Immediate Hopes’ 我們當下的恐懼與期待.

In that famous essay, which for the most part focussed on systemic problems in the People’s Republic under Xi Jinping, Xu Zhangrun was also unsparing in his assessment of the American predicament. Here, allow me to recall the observations Professor Xu made at that time by way of introducing our Know Thyself Primer:

‘[O]n the other side of the Pacific, a crowd of the Ghoulish Undead nurtured on the politics of the Great Game and the Cold War have taken the stage. Certainly, they have their own analysis of world affairs and a particular understanding of the cultural upheavals of today, but like their opposite number here [that is, Xi Jinping and his Politburo], they lack a truly historical perspective; they are shortsighted and avaricious. Since their diagnosis is faulty, the prescriptions they offer are completely off the mark. Trained in a mercantilism that favoured the capitalist elite, with a personality amplified by bloated self-regard and a lifetime habit of rapaciousness, the result is [in Trump, a person possessed of] a prideful quasi-imperial mindset that is coupled to heinous vulgarity. We now have [to deal with] the crudest of blackmailers, a person who knows no shame. What, therefore, [in the case of the United States today] we are presented with is but a degraded civilisation under the tutelage of a flailing and desperate imperialism, one that is itself in terminal decline. Their boastful and vainglorious patriotism stokes the fires of national disaster; here we know them all too well as ‘Patriot-Scoundrels’ [愛國賊, literally ‘patriot thieves’; a kind of shyster who boastfully promotes themselves while sullying everything else under the guise of loyalty].

‘Be it in China or abroad, in the present or in the past: we’ve seen their kind before. One is reminded of those [recent] jokes about how ‘Bad People Have Gotten Older’ [a reference to a popular comic observation that: ‘It’s not that old people have suddenly turned bad, it’s just that bad people have gotten older’ 不是老人變壞了,而是壞人變老了]. Everyone is the product of the education they’ve had. So [for the ‘Old Red Guard’ on that side of the ocean, Donald Trump] there’s no way he can break out of those self-made shackles; he simply doesn’t give a damn, on top of which he’s completely lacking in self-awareness. Dealing with new problems within the framework of an out-of-touch mindset while nonetheless exuding supreme confidence, he inevitably makes the mistakes of the willful. Their ideas and policies are, as Alexis de Tocqueville said [of the Ancien Régime], nothing more than a load of musty debris.’

— Xu Zhangrun 許章潤, ‘Imminent Fears, Immediate Hopes’

我們當下的恐懼與期待, China Heritage, 1 August 2018

with minor emendations

***

On 16 December 2016, I presented an opening address at a conference on Chinese thought and culture held in Melbourne, Australia. My remarks were titled ‘Living with Xi Dada’s China Making Choices and Cutting Deals’ and at the end of my talk I announced the formal launch of China Heritage, the successor to China Heritage Quarterly (2005-2012) and a continuation of my work on The China Story (2012-2016).

On 1 January 2017, China Heritage published its inaugural essay, ‘A Monkey King’s Journey to the East’, which was a light-hearted meditation on Xi Jinping’s China and Donald Trump’s America written for these dark times. It began:

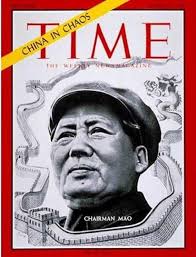

‘The 13 January 1967 issue of Time magazine featured Mao Zedong on its cover with the headline ‘China in Chaos’. Fifty years later, Time made US president-elect Donald Trump its Man of The Year. With a ground-swell of mass support, both men rebelled against the established order in their respective countries and set about throwing the world into confusion. Both share an autocratic mind set, Mao Zedong as Chairman of the Chinese Communist Party, Donald Trump as Chairman of the Board. As Jiayang Fan noted in May 2016, both also share a taste for ‘polemical excess and xenophobic paranoia’. For his part, Mao’s rebellion led to national catastrophe and untold human misery.’

‘The 13 January 1967 issue of Time magazine featured Mao Zedong on its cover with the headline ‘China in Chaos’. Fifty years later, Time made US president-elect Donald Trump its Man of The Year. With a ground-swell of mass support, both men rebelled against the established order in their respective countries and set about throwing the world into confusion. Both share an autocratic mind set, Mao Zedong as Chairman of the Chinese Communist Party, Donald Trump as Chairman of the Board. As Jiayang Fan noted in May 2016, both also share a taste for ‘polemical excess and xenophobic paranoia’. For his part, Mao’s rebellion led to national catastrophe and untold human misery.’

I also commented that:

‘The Chinese Communist Party under its Chairman of Everything, Xi Jinping, hasn’t had to confront such an erratic and populist leader since Mao Zedong launched the Cultural Revolutionary fifty years ago.’

When, on 4 May 2020, Matt Pottinger addressed ‘the Chinese people’ from a vantage in Trump’s White House, it would seem that those inklings had long since become reality. Though in terms of scale, horror and term, Trump is at best a mere mini-Mao, but his MAGA fixations have contributed directly to a national catastrophe that has occasioned and will continue to produce untold human misery. It is with such an awareness, and in this spirit, therefore, that we offer the following preliminary lessons from our Know Thyself Primer.

***

Know Thyself Primer (I)

相得益彰

Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping both quoted Mencius 孟子, the ‘Second Sage’ 亞聖 yà shèng after Confucius himself, to the effect that it is futile to:

以其昏昏,使人昭昭 yǐ qí hūn hūn, shǐ rén zhāo zhāo, or

‘attempt to enlighten others despite the fact that you are befuddled yourself.’

The full line in Mencius reads:

孟子曰:賢者以其昭昭使人昭昭,今以其昏昏使人昭昭。

—《孟子 · 盡心下》

Mencius said, ‘[Anciently], men of virtue and talents by means of their own enlightenment made others enlightened. Now-a-days, [those who would be deemed such, seek] by means of their own darkness to make others enlightened.’

— Tsin Sin, II: XX, in James Legge, The Chinese Classics: Vol.2

The Life and Teachings of Mencius (1875)

To cast this in colloquial English, it means: ‘You just don’t get it, yet here you are lecturing others!’

We would recall that in late 1964 Mao had remarked that wrong-headed approaches to reality were ultimately doomed to failure — he egregiously, and disastrously, ignored his own advice. In the late 1970s, Deng would then quote Mao quoting this line from Mencius in tandem with the expression 實事求是 shí shì qiú shì — ‘seek truth from facts’, or ‘face reality’ — a formulation that had been long favoured by the Communists, even if it had been honoured more in the breach than in the observance. Deng and his colleagues employed expressions like these to enable the Communist Party and China to slough off previous ideological constraints and pursue a fluid pragmatism .

***

Know Thyself Primer (II)

裏外不是人

In my January 2017 caricature-comparison of Donald Trump and Mao Zedong I enumerated a number of superficial similarities between these two figures. In 2020, the fourth year of Trump and the eighth year of Xi Jinping, there is ample evidence to suggest that these autocratic personalities also share more than a few traits in common. This is witnessed by the fact that one allows himself to be hailed as ‘The Ultimate Arbiter’ 定於一尊 while the other crowed about being ‘The Chosen One’. Again, Xu Zhangrun offers us a guide.

In ‘When Fury Overcomes Fear’, his scathing assessment of Xi Jinping’s handling of the coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan published online in early February 2020, Xu Zhangrun identified a range of government-wide problems created by or entrenched under Xi. At the risk of being decried for xenocentrism, ethnocentrism or just plain old cultural relativism, below we quote a number of passages from Xu’s February essay to reflect the present Sino-US ‘doppelgänger effect’ — a phenomenon in which the division between Self and Other would seem to dissolve. Xu excoriates the Chinese party-state, but his words could effortlessly be applied ‘back East’, that is to say, to Washington. Simply read Washington for China, the Republican Party for the Communist Party and Trump’s White House for the Party-State:

Recto & Verso

‘The political life of the nation is in a state of collapse and … the ethical core of the system has been rendered hollow. The ultimate concern of China’s polity today and that of its highest leader is to preserve at all costs the privileged position of the Communist Party and to maintain ruthlessly its hold on power. What they dub “The Broad Masses of People” are nothing more than a taxable unit, a value-bearing cipher in a metrics-based system of social management

‘ “The People” is a rubric that describes the price everyone has to pay to prop up the existing system.

‘The storied bureaucratic apparatus that is responsible for the unfettered outbreak of the coronavirus in Wuhan repeatedly hid or misrepresented the facts about the dire nature of the crisis. The dilatory actions of bureaucrats at every level exacerbated the urgency of the situation. Their behavior has reflected their complete lack of interest in the welfare and the lives of normal people. What is of consequence for them is their tireless support for the self-indulgent celebratory behavior of the “Core Leader” whose favor is constantly sought through their adulation for the peerless achievements of the system.

‘Ever more vacuous slogans are chanted—Do this! Do that!—overweening and with prideful purpose, He garners nothing but derision and widespread mockery in the process.’

— from ‘Politics in a New Era of Moral Depletion’

‘Tyranny ultimately corrupts the structure of governance as a whole and it is undermining a technocratic system that has taken decades to build. There has been a system-wide collapse of professional ethics and commitment.

‘The people in the system who have now been promoted are in-house Party hacks who slavishly obey orders. Consequently, both the kind of professional commitment and expertise previously valued within the nation’s technocracy, along with the ambition people previously nurtured to seek promotion on the basis of their actual achievements, have been gradually undermined and, with no particular hue and cry, they have now all but disappeared. The One Who Must Be Obeyed … the man with the ultimate decision-making power and sign-off authority, has created an environment in which the system as a whole has fallen into desuetude. What’s left is a widespread sense of hopelessness.

‘Despite all the talk one hears about “modern governance,” the reality is that the administrative apparatus is increasingly mired in what can only be termed inoperability.

‘Don’t you see that although everyone looks to The One for the nod of approval, The One himself is clueless and has no substantive understanding of rulership and governance, despite his undeniable talent for playing power politics. The price for his overarching egotism is now being paid by the nation as a whole. Meanwhile, the bureaucracy drifts directionless, although the best among them try to get by as best they can. They would like to take positive action, but they are hesitant and fearful.’

— from ‘Tyranny in a New Era of Political License’

‘A Party-State system that has no checks or balances, one that actually resists the rational allocation of duties and responsibilities, invariably gives rise to the rule of a clique of trusted lieutenants. Hence we have seen the equivalent of a court emerge and the political behavior endemic to a court.

‘… It is only in the last few years that a new kind of hermetically sealed governance has come to the fore and, because of the nature of hidden court politics, it is one that has further enabled the sole power-holder while granting license to the darkest kinds of plotting and scheming. Such a rulership structure stifles systemic innovation and forecloses the kinds of changes that might enhance regularized forms of governance. With the way ahead reduced to something akin to a “political locked-in syndrome,” and since a meaningful retreat is all but impossible, the system is put under constant strain. It is virtually impossible for anyone to act in any meaningful fashion. Instead, all are forced to look on in impotent frustration as things deteriorate. This may well continue until the situation is simply beyond salvaging.’

— from ‘A New Era of Revived Court Politics’

Stopgap Comments

on ‘Reflections on China’s May Fourth Movement:

An American Perspective’

Remarks Made by Deputy National Security Advisor Matt Pottinger

to the Miller Center at the University of Virginia

4 May 2020

(Note: For the Chinese text of Mr Pottinger’s speech, see here, and for the English, here. The official video can be seen here. The English text is also reproduced at the end of these comments.)

***

***

In his address, Matt Pottinger first sets the scene by locating himself at the White House following which he conveys to his audience ‘warm greetings from the 45th President of the United States, Donald J. Trump’. Then, having duly dealt with the pleasantries required on such occasions, as well as having signalled the unique circumstances that have forestalled an embodied encounter with his audience — that is the coronavirus epidemic which, by this stage, was infiltrating the White House itself — Mr Pottinger addresses the significance of the occasion: ‘China’s historic May Fourth Movement … a potent topic for discussing the China of then and now.’

The Rise & Demise of Hu Shih

In his thumbnail account of the events of 1919 and the analysis that follows, Mr Pottinger singles out two figures, men whom he hails as ‘Chinese heroes’, embodiments of ‘the May Fourth spirit, then and now’. The first of these is Hu Shih (胡適, 1891-1962) who, as the speaker rightly observes:

‘… is naturally identified as one of the most influential leaders of the May Fourth era. He was already an influential thinker on modernizing China.’

Pottinger goes on to say, or rather overstate, that:

‘Hu Shih would contribute one of the greatest gifts imaginable to the Chinese people: The gift of language. Up until then, China’s written language was “classical,” featuring a grammar and vocabulary largely unchanged for centuries. As many who have studied it can attest, classical Chinese feels about as close to spoken Chinese as Latin does to modern Italian. The inaccessibility of the written language presented a gulf between rulers and the ruled—and that was the point. The written word—literacy itself—was the domain primarily of a small ruling elite and of intellectuals, many of whom aspired to serve as officials. Literacy simply wasn’t for “the masses.” ‘

Gross simplification is inevitable in such a short, politically charged speech. Nonetheless, even here we can detect that the author is laying the groundwork, for a major theme his remarks, which reaches a crescendo far below:

‘In his view, written Chinese—in form and content—should reflect the voices of living Chinese people rather than the documents of dead officials. “Speak in the language of the time in which you live,” he admonished readers. He believed in making literacy commonplace. He played a key role promoting a written language rooted in the vernacular, or baihua—literally “plain speech.” Hu Shih’s promotion of baihua is an idea so obvious in hindsight that it is easy to miss how revolutionary it was at the time. It was also highly controversial.

‘… Hu Shih, wielding the language he had helped bring to life, skillfully dismantled arguments against broadening the social contract. “The only way to have democracy is to have democracy,” Hu Shih argued. “Government is an art, and as such it needs practice.” Hu Shih didn’t have time for elitism.

‘Still, May Fourth leaders were constantly sapped of energy by accusations, sometimes leveled by government officials or their proxies among the literati, that the movement was slavishly pro-Western, insufficiently Chinese, or even unpatriotic.’

These words will ring with a more sombre tone later when we contemplate Pottinger’s exultation of ‘democratic populism’, one that is

‘… about reminding a few that they need the consent of many to govern. When a privileged few grow too remote and self-interested, populism is what pulls them back or pitches them overboard. It has a kinetic energy. It fueled the Brexit vote of 2015 and President Trump’s election in 2016.’

Of course, Hu Shih is a ready made paragon whose name is regularly invoked in the kind of speechifying delivered by ‘China literate’ Western university leaders and political figures. I am familiar with, indeed even fond of the genre. After all, as I noted in the above, it is a genre to which I contributed, having had a hand in a speech delivered at Peking University by Prime Minister Kevin Rudd during his official visit to Beijing in April 2008. (See ‘Rudd rewrites the rules of engagement’, Sydney Morning Herald, 12 April 2008.)

At the time, in commenting on Rudd’s speech I pointed out that, in the decades after May Fourth, Hu Shih moved closer to the power-holders. Mao Zedong was so obsessed with his influence and role in post-1949 Taiwan that, in late 1954, he launched a nationwide campaign to purge Hu’s influence in academia, government and the nation’s political life. In some crucial ways the politics of the People’s Republic never recovered from what was formally called a denunciation of ‘Third Way’ or ‘Middle Path’ political thinking. (For the abiding significance of the 1954 movement in, for example, the Hong Kong today, see Lee Yee 李怡, ‘The End of Hong Kong’s Third Way’, China Heritage, 22 April 2020.)

This is no place to quibble further about Pottinger’s outline account of the youthful Hu Shih’s importance to the May Fourth period, or indeed about the evolution of vernacular written Chinese (my views can be found in ‘On New China Newspeak 新華文體’). Here, we would suggest that the story of Hu Shih, and his post-May Fourth history is also noteworthy when discussing Chinese democracy, even if it is not particularly uplifting.

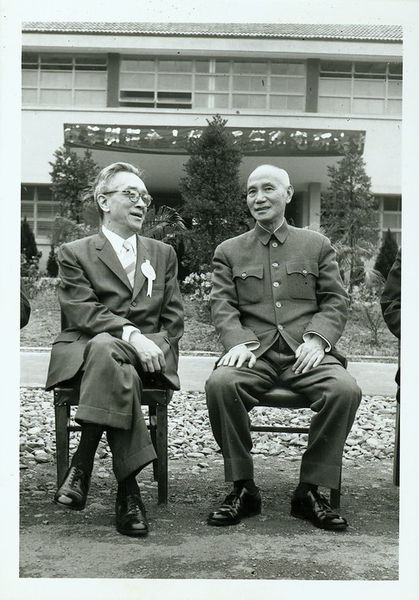

However, having made significant contributions to the liberal tradition of modern Chinese life in the 1920s and 1930s Hu Shih would, over time, find the gravitational pull of politics, power and prestige exerted by Chiang Kai-shek, Mao Zedong’s political nemesis, and the Nationalist Party that he led hard to resist. Hu followed the Republic of China to Taiwan whence it relocated following the bloody Nationalist Party prelude of 28 February 1947 and defeat at the hands of the Communists on the mainland. Although the last decade of Hu’s life was crowned with honours it was also elegiac. As Chiang Kai-shek’s 諍臣 zhèngchén — ‘outspoken counsellor’, although the term can just as well mean ‘an autocrat’s intimate’ — Hu Shih gradually reduced his earlier lofty liberal aspirations to a maxim: ‘tolerance is more important than freedom’ 容忍比自由重要. When American officials today discuss Hu Shih, it is therefore incumbent upon independent scholars to recall that the harsh authoritarianism of the Nationalist government in the 1950s — to which Hu Shih lent his support, and for which he was duly rewarded — was a polity that was endorsed and supported by the United States.

In his later years, Hu Shih’s once-spirited defence of independent political values and free speech faltered, then failed. Granted, there are reports that, in April 1958, he had the momentary temerity to disagree with Chiang publicly. It was on the occasion of the president-for-life’s visit to Academia Sinica, a prestigious institution of which Hu was president, at Nan-kang outside Taipei. Chiang made an observation that the liberalism promoted during the May Fourth era by people like Hu had directly contributed to the rise and eventual dominance of the Communists on the Mainland. Even though Hu’s protest was little more than a muffled ‘That’s not correct’. It was the last time that Chiang visited the Academy.

***

***

Shortly thereafter, in a pitiful denouement to a sometimes stellar career, Hu‘s reputation as an exponent of democratic virtues was irrevocably tarnished as a result of the infamous ‘Lei Chen Case’ 雷震事件 of 1960 which involved the banning of Free China 自由中國, a journal of independent opinion which published critiques of Chiang Kai-shek’s dictatorial government and advocated for both economic and political reform. Hu had been the chief executive of the journal although the editor-in-chief was Lei Chen 雷震. Lei, who was a former political adviser to Chiang Kai-shek, had become a prominent advocate of democracy and opposition politics, and he was a leading figure in the establishment of the China Democratic Party 中國民主黨. The philosopher and educator Yin Hai-kuang 殷海光 was also a frequent contributor to the editorial pages of Free China and his principled support for the new opposition party helped cement his reputation as the intellectual leader of liberalism on the island. Lei Chen was arrested, tried by a military tribunal and jailed for ten years. Yin was accused of ‘fomenting rebellion’ and silenced. Many others would be subjected to long years of political persecution. Following Lei Chen’s downfall, apart from impotent handwringing and counselling Chiang to exercise restraint, Hu maintained a studied distance from his erstwhile colleagues. His critics note that he even failed to muster sufficient courage to visit the imprisoned Lei, an old friend.

This final benighted chapter in the story of China’s most famous twentieth-century liberal is the theme of Confronting Autocracy — the contrasting attitudes of Hu Shih and Yin Hai-kuang 面對獨裁——胡適與殷海光的兩種態度 (Taipei: Yunchen Wenhua 允晨文化, 2017) by Chin Heng-wei 金恆煒, a noted Taiwanese political commentator, essayist and editor. In his May Fourth speech Pottinger refers positively to the admirable work of John Pomfret on the history of the US-China relationship, as well as to Vera Schwarcz’s The Chinese Enlightenment. Given the US-China confrontations of recent years, and the ongoing existential threat of Taiwan to the People’s Republic, and vice versa, the unsavoury aspects of Hu Shih’s egregious failure to defend liberal democracy by actually ‘speaking truth to power’ when it mattered and resiling from principles he advocated when it proved to be impolitic to do so, are also worthy of note. Therefore I have composed this particular ‘stopgap comment’ 補白.

Writing shortly after Hu Shih’s death on 24 February 1962, Jerome B. Grieder, author of Hu Shih and the Chinese Renaissance: Liberalism in the Chinese Revolution, 1917-1937, made the following observation:

‘… Chiang Kai-shek composed and wrote out in his own hand a memorial scroll summarising the accomplishments of the man who had been one of his most reasonable, and at times his most perceptive, critics. Hu Shih, wrote the President, was

A model of the old virtues within the New Culture—

An example of the new thought within the framework of old moral principles.‘There is no reason to assume that Chiang was doing more than paying his sincere respects to the dead. He was, perhaps, unaware of the fact that he had in a certain sense described the position into which Hu Shih had been forced by the circumstances of his own temperament and beliefs and of the times in which he lived. And surely Chiang Kai-shek had not intended to remind us, as he did nevertheless, that if his small realm [Taiwan] is indeed the repository of what is good and true from China’s past, it is also the repository of the intellectual frustrations of the last several decades. Unable to forsake the past, unable to praise except in terms of ancient beliefs and values, it is the victim of a crisis of identity which may yet destroy it.’

— Jerome B. Grieder, ‘Hu Shih: An Appreciation’

The China Quarterly, no.12 (October-December 1962): 92-101

reprinted in China Heritage Quarterly, Issue 29 (March 2012)

***

Know Thyself Primer (III)

中美命運共同體

Since 2013, Xi Jinping and his government have advocated the creation of ‘a community of shared destiny’ (see China Story Yearbook 2014: Shared Destiny). The concept has also been a prominent feature of China’s global response to the coronavirus pandemic (see, for example, 席來旺, ‘全球抗疫中「人類命運共同體」理念充分彰顯’, 人民網,2020年5月13日). Here, once more, we would suggest that the following paragraphs from Xu Zhangrun’s February 2020 coronavirus protest could be read as a Sino-American palimpsest:

‘No matter how complex, nuanced and sophisticated one’s analysis, the reality is stark. A polity that is blatantly incapable of treating its own people properly can hardly be expected to treat the rest of the world well. How can a nation that doggedly refuses to become a modern political civilization really expect to be part of a meaningful community? That’s why although mutually beneficial economic exchanges will continue unabated, China’s civilizational isolation will remain an undeniable reality. This has nothing to do with a culture war, even less can it be encapsulated in—and dismissed by—such glib concepts as a “clash of civilizations.” Nor is this situation simply a matter of a new wave of anti-Chinese sentiment, or Sinophobia or a desire to put China down. I say that despite the fact that, for the moment, dozens of countries have imposed travel restrictions on people from the People’s Republic.

‘Nonetheless, I would remind readers that as the present China scare increases talk about the threat of a “Yellow Peril,” that long occluded and sclerotic ideological construct, must invariably intensify . Internationally, the due appreciation for universal values and human rights was hard won and it only achieved widespread acceptance following a tortuous period of contestation. These concepts have long been a standard element in the treaties and agreements that underpin the international community. China’s own international engagement and its worthiness of enjoying a substantive place in the international community depend too on how these philosophical issues are understood and treated [that is, if the People’s Republic can evolve and accept internationally recognized rights and universal values, which at present are rejected as a threat to Party domination in China]. Over time who will prosper and who will move against the tides of history—that is, who will end up being isolated—these are questions that can only be answered in the process of some places being isolated by others or as a result of those states that decide to self-isolate and end up alone. Those nations [and here the author is thinking of China] may end up appreciating their assumed pulchritude as reflected back at them in the mirror of their imperial self-regard.’

— Xu Zhangrun, ‘When Fury Overcomes Fear’

***

***

Human Rights Betrayed

The second May Fourth hero singled out by Mr Pottinger in his speech was P.C. Chang (Peng Chun Chang 張彭春, 1892-1957). Here Pottinger’s observations about democratic values, basic freedoms and Chinese culture are cogent and noteworthy. The affirmation of the significance of Chinese democracy in Taiwan today is also welcome. As the speaker says about P.C. Chang:

‘In China’s philosophy of moral cultivation and rigorous education, Chang saw advantages that could be combined with ideas from the West to form something new.

‘This culminated in Chang’s crowning achievement: His decisive contributions to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. This was the document drafted after World War II by an international panel chaired by Eleanor Roosevelt. Chang, who was by then a veteran diplomat representing China, was a member of the panel. The declaration’s aim was to prevent despotism and war by morally obligating governments to respect fundamental rights. The rights enshrined in the 1948 declaration include life, liberty, and security; the right not to be held in slavery or subjected to torture; the right to freedom of religion; and the right to freedom of thought.

‘ “Marrying Western belief in the primacy of the individual with Chinese concern for the greater good” Chang helped craft a document that would be relevant to all nations, John Pomfret wrote. A declaration on human rights was not simply about the rights of the individual, in Chang’s view. It was also about the individual’s obligations to society.

‘Chang’s biographer, Hans Ingvar Roth of Stockholm University, highlighted the weight of Chang’s contributions to the Declaration: “Chang stands out as the key figure for all of the attributes now considered significant for this document: its universality, its religious neutrality, and its focus on the fundamental needs and the dignity of individual human beings.” ‘ [Note: links added by China Heritage]

Certainly, these ideas are supported by liberal thinkers in Mainland China with courage, conviction and through many instances of personal sacrifice. However, it is these very ideas and ideals that are abused, undermined and ridiculed by the American administration that Matt Pottinger represented when speaking to Chinese audiences worldwide, and in particular in the People’s Republic, on May Fourth.

Over the last three years, numerous commentators have dissected the lawlessness that flourishes under the Trump administration; it is not a singularity limited merely to the mobster-like personality of US President Donald Trump: it is its global governing principle. Of course, we would emphasise that, to use Xu Zhangrun’s formulation for Xi’s impact on government, ‘organizational discombobulation’ has been a feature of partisan politics in America for many years. In regard to the egregious behaviour of the present administration, however, we would refer readers to the introductory paragraphs of the latest Human Rights Watch World Report:

‘In 2019, the United States continued to move backwards on rights. The Trump administration rolled out inhumane immigration policies and promoted false narratives that perpetuate racism and discrimination; did not do nearly enough to address mass incarceration; undermined the rights of women and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people; further weakened the ability of Americans to obtain adequate health care; and deregulated industries that put people’s health and safety at risk.

‘In its foreign policy, the Trump administration made little use of its diminishing leverage to promote human rights abroad; continued to undermine multilateral institutions; and flouted international human rights and humanitarian law as it partnered with abusive governments—though it did sanction some individuals and governments for committing human rights abuses.’

But, Mr Pottinger, if we put all of that to one side, given Mr Trump’s penchant for evaluating women on a numerical scale: tell me, how do you think Eleanor Roosevelt would score?

***

***

Ink & Blood

墨寫的謊說,決掩不住血寫的真實。

‘Lies written in ink can never disguise facts written in blood.’

— Lu Xun, 29 March 1926, quoted by Matt Pottinger on 4 May 2020

‘The real opposition is the media. And the way to deal with them is to flood the zone with shit.’

— Steve Bannon, 2018

‘What you’re seeing and what you’re reading is not what’s happening.’

— Donald Trump addressing veterans, 25 July 2018

In his speech Mr Pottinger goes on to say that:

‘Those with the fortitude to seek and speak the truth in China today may take comfort, however, in something Lu Xun wrote: “Lies written in ink can never disguise facts written in blood.” ‘

It is an entirely laudable sentiment, in particular as it follows on from a roll-call of some of the brave few who dare to ‘live in truth’ and ‘speak truth to power’ in China. Yet, again, such sentiments issuing forth from the White House as the ‘Trump Death Clock’ in Times Square, New York City, was flashing out a constant update of the national carnage wrought by the dilatory and obfuscating actions of a president faced by the coronavirus pandemic left this audience of 瞠目咋舌 chēng mù zé shé — ‘eyes wide and tongue stuck out’ — in wonderment at Mr Pottinger’s ‘audacity of hope’.

As luck would have it, on 4 May as Mr Pottinger talked about ink and lies, The Lincoln Project released an ad titled ‘Mourning in America’, which predictably sent Trump into a Twitter-rage.

***

Or, there was Peter Wehner writing about the burlesque in Washington just as Pottinger was speaking out against the Chinese Communist Party’s endemic culture of lies. Wehner listed ‘some of the essential traits of Donald Trump’:

‘the shocking ignorance, ineptitude, and misinformation; his constant need to divide Americans and attack those who are trying to promote social solidarity; his narcissism, deep insecurity, utter lack of empathy, and desperate need to be loved; his feelings of victimization and grievance; his affinity for ruthless leaders; and his fondness for conspiracy theories. …’

He then tells his readers:

‘What this means is that Americans are facing not just a conventional presidential election in 2020 but also, and most important, a referendum on reality and epistemology. Donald Trump is asking us to enter even further into his house of mirrors. He is asking us to live within a lie, to live within his lie, for four more years. The duty of citizenship in America today is to refuse to live within that lie.’

— Peter Wehner, ‘The President Is Unraveling’, The Atlantic, 5 May 2020

Wehner also quoted Alexandr Solzhenitsyn’s 1970 Nobel lecture:

‘The simple step of a simple courageous man is not to partake in falsehood, not to support false actions… . Let that enter the world, let it even reign in the world—but not with my help.’

That may not be an essential credo for American Republicans today, but the bevy of red-baiting China Experts might wish to compare their own circumstances with those described by Simon Leys, my mentor, in 1977:

‘The psychology and behaviour of Peking’s ruling clique are those of gangsters. This is not just a colourful and polemical way of speaking but a sober statement of fact, and in fact it is the underworld which might find the comparison insulting — after all its members do have some sense of honour (even of a perverse variety), personal loyalty, and a warped kind of brotherhood in arms. That is a lot more than can be said for the turncoats and cut-throats of the Forbidden City, whose ceaseless intrigues and mutual waylaying round the corners of the corridors of power, as well as their cynically shifting alliances, are proof of a lack of principle which would have brought a blush to the cheeks of the members of the secret societies of the old Shanghai underworld.’

— Simon Leys, ‘Peking Duck Soup’

China Heritage, 23 January 2018

To concluding this ‘stopgap note’, I’ll quote another passage from the observations I made in January 2017:

‘Since its founding in 1949, the People’s Republic of China has lived in a post-truth bubble. With its guided media and vast propaganda-industrial complex the Party maintains its rule over facts with relentless vigilance. The neo-liberal West has, from the days of the Reagan-Thatcher duumvirate, increasingly relied not merely on economic growth, but also on the distortion of reality to bolster its hold over consumer’s hearts-and-minds. We have lived into an age in which the Lying East and the Lying West are reaching a new kind of equilibrium. Some call this not-cold, not-hot war a chilly war of ideologies, 涼戰, or at least of vested interests. It has created a face off of like-against-like and, for students of the political and cultural dilemmas of the twentieth-century it provides a harrowing lesson in real-time politics.’

— ‘A Monkey King’s Journey to the East’

China Heritage, 1 January 2017

***

Know Thyself Primer (IV)

自暴自棄

‘Given the way things have been going in China, this country is set upon making enemies for itself in all directions, so much so that what is unfolding right now is unsettlingly similar to the situation back in the ‘gengzi year’ of 1900. This time around, however, the United States is no longer the country it once was. After a century during which it enjoyed virtual hegemony, it is now a nation riven by division and conflict; it is a tangle of chaos. America is facing a profound systemic crisis, one that begs thorough-going reform. Moreover, neither side can presently boast of having the kinds of far-sighted and open-minded politicians who lived at the beginning of the twentieth century, people who could formulate policies that not only benefitted themselves but also generated common weal, policies that over time contributed to nations learning to beat swords into plowshares.

‘Absent, too, are the leaders possessed of a magnanimity of spirit and a sense of global responsibility of the kind that we witnessed in those first precious years following the Second World War. Instead, the landscape is populated by politicians who put narrow party interests ahead of all else. Wherever we look we see leaders who have been back footed by a pandemic that is sweeping the world. Will the ‘self-correcting mechanisms’ embedded in the American system still prove effective? Yet, even if they are, it is impossible to know how long any substantial re-calibration there may take. Regardless, we should be in no doubt as to the fact that the present state of affairs and the actions being taken [by the Americans] are not advantageous to China.’

— Zi Zhongyun 資中筠 in ‘1900 & 2020

— An Old Anxiety in a New Era’,

China Heritage, 28 April 2020

***

***

Better Angels

‘So who embodies the May Fourth spirit in China today?’, Mr Pottinger asks rhetorically:

‘To my mind, the heirs of May Fourth are civic-minded citizens who commit small acts of bravery. And sometimes big acts of bravery. Dr. Li Wenliang was such a person. Dr. Li wasn’t a demagogue in search of a new ideology that might save China. He was an ophthalmologist and a young father who committed a small act of bravery and then a big act of bravery. His small act of bravery, in late December, was to pass along a warning via WeChat to his former medical school classmates that patients afflicted by a dangerous new virus were turning up in Wuhan hospitals. He urged his friends to protect their families. ,,,

‘Then Dr. Li did a big brave thing. He went public with his experience of being silenced by the police. The whole world paid close attention. By this time, Dr. Li had contracted the disease he’d warned about. His death on February 7 felt like the loss of a relative for people around the world. Dr. Li’s comment to a reporter from his deathbed still rings in our ears: “I think there should be more than one voice in a healthy society, and I don’t approve of using public power for excessive interference.” Dr. Li was using Hu Shih-style “plain speech” to make a practical point.’

Indeed, Mr Pottinger, if only the WHOLE world had in fact paid close attention to Li Wenliang’s bravery, not merely on the basis of some wishful thinking about a popular rebellion against Beijing. Who among us does not fervently wish that the governments of the likes of Donald Trump and Boris Johnson, that’s right, the populist role models that Mr Pottinger praises (see below), had treated the message, and not just the example, of Li Wenliang seriously. Mr Pottinger also mentions the names of citizen journalists ‘who tried to shed light on the outbreak in Wuhan’ — Chen Qiushi, Fang Bin and Li Zehua — as well as writers who ‘follow the long tradition of scholars serving as China’s conscience’ like Xu Zhangrun, Xu Zhiyong and Ren Zhiqiang, as well as the doctor Ai Fen. (Here we would recall the American ‘White Paper’ of August 1949, quoted in the above, and the sentiment expressed at the time regarding ‘the long-term danger posed to a Communist party-state by ‘democratic individualists’ 民主個人主義, that is men and women trained in or sympathetic to Western values, politics, economic thinking and scholarship.’)

For this reader, however, it is repugnant to see these names in the service of sentiments issuing from a Washington bureaucrat who has contributed to Trump-era America’s incoherent and vacillating China policy, one which has, among many things, disrupted regional alliances, undermined valuable reporting on China, aggravated tensions across the board and reaped few, if any, significant benefits. For someone who has been alert to and alarmed by simple-minded approaches to post-Mao China, and as a writer and academic who has publicly given voice to my reservations in my work for nearly four decades, now to witness this careening shambles is nothing less than tragicomic.

At this juncture, I would also point out that, for decades my work has partly focussed on what, over time, I have come to call ‘The Other China’. That is:

‘one that is educated, informed, skeptical, well-read, often well-traveled and part of a modern global society. This Other China is often silenced, ignored or ill-understood, but it will flourish well beyond the tenure of Xi Jinping.’

— Jane Perlez, ‘Q. and A.: Geremie R. Barmé on

Understanding Xi Jinping’

The New York Times, 9 November 2015

Similarly, in dealing with America, and finding inspiration and worth in much from the other side of the Pacific, one recalls ‘the better angels’ first spoken of by Abraham Lincoln in his inaugural address as US president on the steps of the Capitol Building in Washington on 4 March 1861. It was on the eve of the Civil War and Lincoln was pleading to a divided nation. Today, the better angels of America are still inspiring, but they do so not with platitudes or vacuous references to ‘populism’. Such things are forged from darker matter and they evoke division, discrimination and hate. Just as the actions of the men and women of conscience in The Other China inspire us, so do the better angels of America.

Following the roll-call of the brave, Mr Pottinger offers a lapidary truth known to people in oppressive societies throughout history:

When small acts of bravery are stamped out by governments, big acts of bravery follow.

On 4 May 2020, this succinct statement begs a question: Isn’t such a sterling sentiment sullied by having been delivered from the epicentre of American political baloney and hypocrisy?

***

***

Perhaps then Rick Bright is better qualified than Mr Pottinger to teach us about ‘small acts of bravery’ at a time of national need:

‘Bright, who was director of the Department of Health and Human Services’ Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority until his removal in April, said in a formal whistle-blower complaint that he had been protesting “cronyism” and contract abuse since 2017. …

‘The 89-page complaint, filed with the Office of Special Counsel, which protects federal whistle-blowers, also said Dr. Bright “encountered opposition” from department superiors — including Health and Human Services Secretary Alex M. Azar II [a former pharmaceutical lobbyist and executive, and current United States Secretary of Health and Human Services] — when he pushed as early as January for the necessary resources to develop drugs and vaccines to counter the emerging coronavirus pandemic….

‘The document paints Dr. Bright as sounding the alarm about the emerging coronavirus threat and pressing his superiors to do more to prepare — including purchasing masks that would later turn out to be in short supply — at a time when Mr. Azar was downplaying the crisis.

‘On Jan. 23, he met with Mr. Azar and Dr. Kadlec to press “for urgent access to funding, personnel and clinical specimens, including viruses,” that would be necessary to develop treatments, the complaint said. But Mr. Azar and Dr. Kadlec “asserted that the United States would be able to contain the virus” through travel bans, the complaint said, adding that Dr. Bright was cut out of future department meetings related to Covid-19.’

— Sheryl Gay Stolberg, ‘Virus Whistle-Blower Says

Trump Administration Steered Contracts to Cronies’

The New York Times, 5 May 2020

(Interestingly, it was Peter Navarro, a hardline China-policy colleague of Mr Pottinger, who reportedly offered support to the ‘Li Wenliang of Washington’. The Bright whistleblower case is ongoing.)

As Xu Zhangrun has noted, Li Wenliang and others who dare to speak out, protest or demand that they be treated with dignity, are victims of China’s ‘big-data totalitarianism’. As Xu has noted:

‘Through their taxes the masses are, in fact, funding a vast Internet police force dedicated to overseeing, supervising and tracking everyone and all of the statements and actions they author. The Chinese body politic is riven by a new canker, but it is an infection germane to the system itself.’

— Xu Zhangrun, When Fury Overcomes Fear’, 4 February 2020

Meanwhile, in the United States, the coronavirus epidemic offers opportunities to its high-tech companies in their ongoing efforts to enhance a homegrown version of ‘surveillance capitalism’ that will be competitive with Chinese state-private innovations. Naomi Klein is one of those who has sounded a warning bell against coronavirus-era ‘techno-optimism’:

‘Tech provides us with powerful tools, but not every solution is technological. And the trouble with outsourcing key decisions about how to “reimagine” our states and cities to men like Bill Gates and Eric Schmidt is that they have spent their lives demonstrating the belief that there is no problem that technology cannot fix.

‘For them, and many others in Silicon Valley, the pandemic is a golden opportunity to receive not just the gratitude, but the deference and power that they feel has been unjustly denied.’

— Naomi Klein, ‘Screen New Deal’, The Intercept, 8 May 2020

The pandemic has a deadly impact on individuals with serious underlying conditions, just as it has revealed the serious underlying systemic and governance conditions of nations that have mishandled it. When those in power, be they in Beijing or Washington, commend the bravery and sacrifice of whistleblowers like Li Wenliang, a Biblical cliché comes to mind: ‘Medice, cura te ipsum’ (Physician, heal thyself).

***

Of course, we can well imagine that such distasteful bilateral comparisons might cause discomfort, but would that they might also occasion a moment of reflection. This brings us to another next lesson from our Know Thyself Primer:

Know Thyself Primer (V)

苟活