Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium

Chapter XXIII, Part I

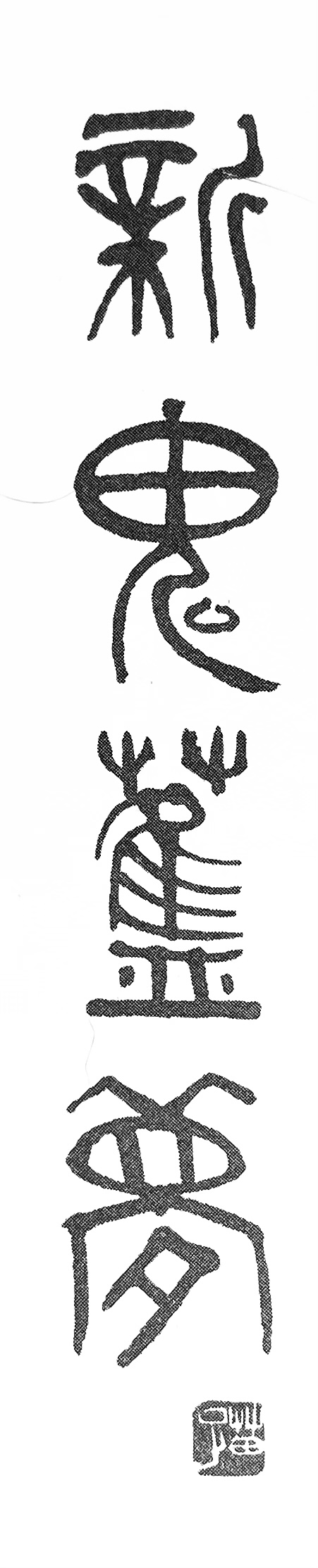

新鬼舊夢

The theme of ‘Chinese Time’, a two-part chapter in Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium published on the first two days of 2023, is the tension between forgetfulness and memory.

The year 2022 has ended in a confounding welter of protest, widespread illness and unaccounted for deaths resulting from erratic government policy. The mayhem of a system that is both aloof and intrusive brings to mind other periods of harsh politics, individual valour and murder that have been a feature of China’s modern history.

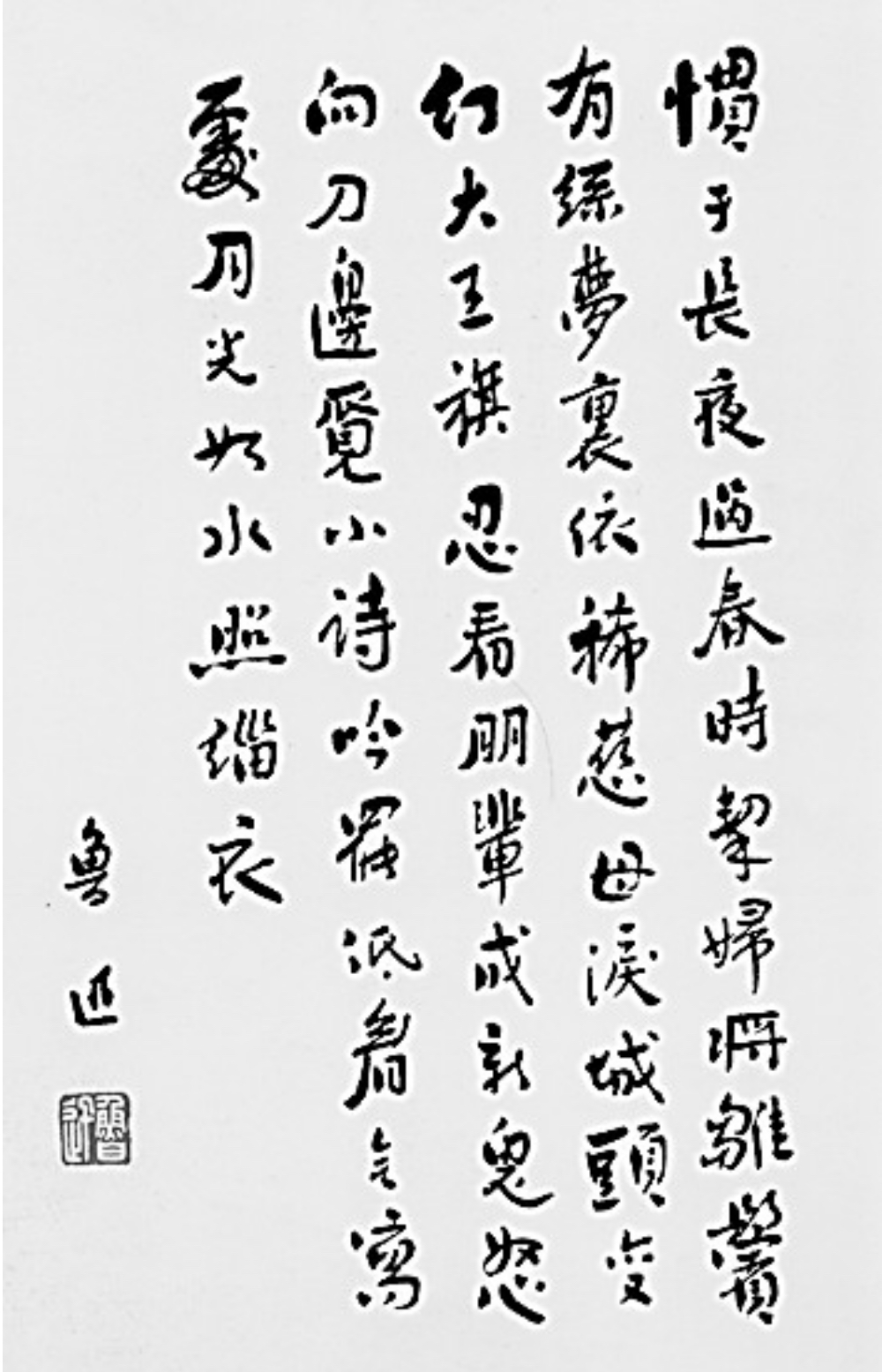

In 1933, Lu Xun composed an essay to commemorate five young writers who had been executed in secret by the Nationalist government two years earlier, in February 1931. ‘Written for the Sake of Forgetting’ 為了忘卻的紀念 remains one of his most famous works. Lu Xun included a poem he had composed in 1931 in his essay. One line of the poem read:

I can but stand by, looking on as friends become new ghosts

I seek an angry poem from among the swords

忍看朋輩成新鬼,怒向刀叢覓小詩。

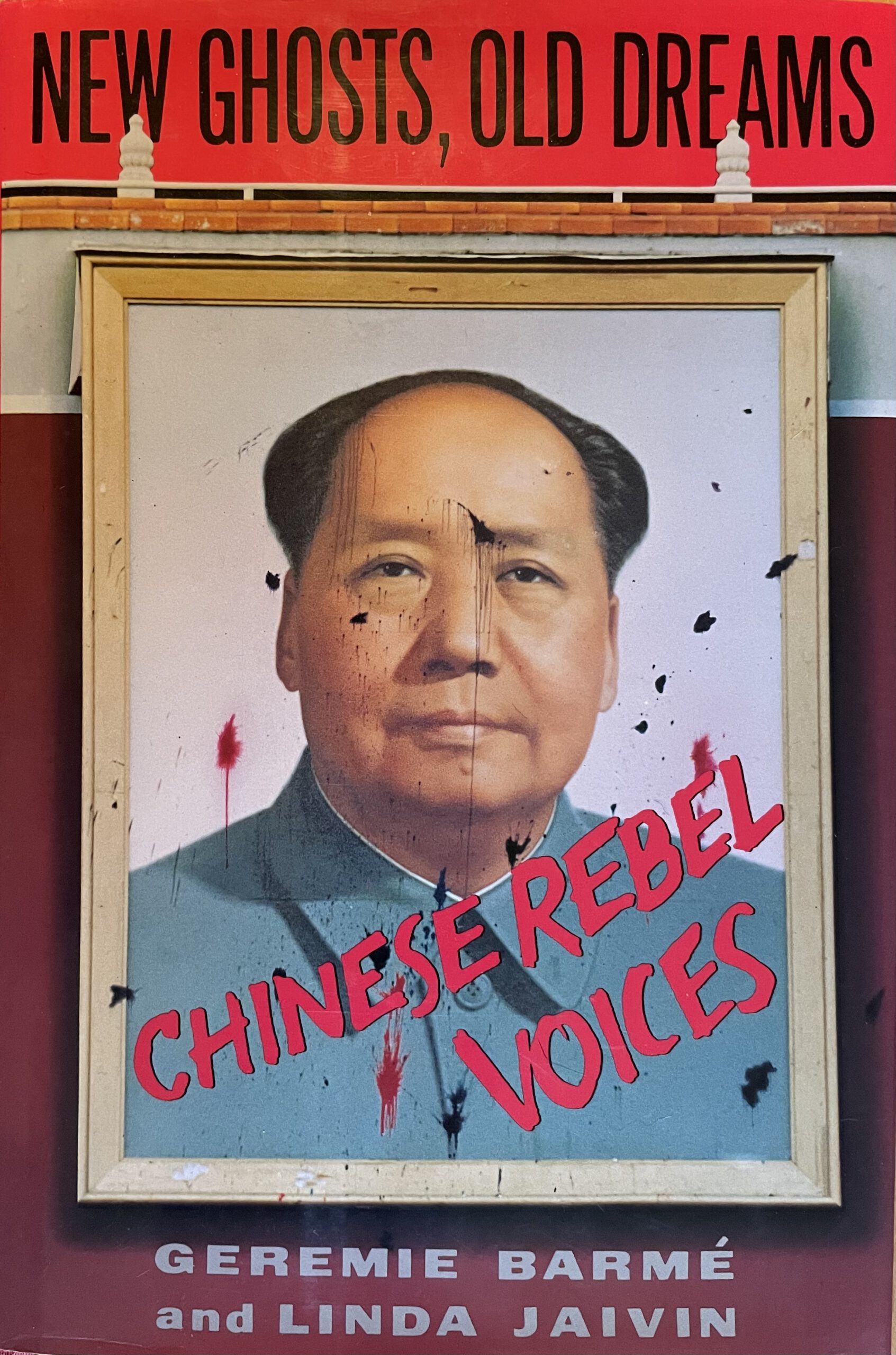

Some sixty years later, Lu Xun’s poem, and the essay in which it had subsequently appeared, inspired the title New Ghosts, Old Dreams: Chinese Rebel Voices, a book produced in response to the tumult of 1989. In late 2022, Zhang Lifan (章立凡, 1950-), an independent historian and writer based in Beijing, published a poem online on the ‘Blank Paper Rebellion’ of November that year. He modeled his doggerel verse on Lu Xun’s poem.

Zhang’s poem provided the inspiration for this chapter of Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium.

***

The book title New Ghosts, Old Dreams contains a double reference:

In early June 1989, at least a thousand (and possibly many more) ‘new ghosts’ were created when the Chinese government brutally crushed the peaceful student-led Protest Movement of that spring and began a political purge on a scale not seen in China since the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976).

The second part of the book’s title, ‘old dreams’, referred to the dreams of freedom and self-expression that Chinese individuals have pursued for millennia; the dreams of a modern, democratic, and equitable polity cherished by reformist intellectuals for nearly a century; and the dreams of being on an equal footing with the rest of humanity, true members of the international community.

In 2022, China saw ‘more new ghosts’ result from the government’s callous missteps, even as the ‘same old dreams’ persisted.

***

Conceived of as being a sequel to Seeds of Fire: Chinese Voices of Conscience (Hong Kong, 1986; 2nd ed., New York: 1988), New Ghosts, Old Dreams was more than a timely sequel. Containing material compiled and translated in the wake of 4 June 1989, it was compiled at a time when many of our friends were still in jail, under investigation or subject to constant surveillance. It attempted to record some of the events of 1989 while paying homage both to those who had lost their lives and to the indomitable spirit that had motivated the rebellion of April-May 1989.

It was a low point in China’s post-Mao era and elsewhere we have commented on its crucial relationship to the Xi Jinping decade (see Prelude to a Restoration: Xi Jinping, Deng Xiaoping, Chen Yun & the Spectre of Mao Zedong, China Heritage, 20 September 2021).

The agonising sorrow we felt working on New Ghosts, Old Dreams was frequently alleviated by some of the material we included — works of rambunctious fiction, moving poems, thoughtful essays, cartoons and art work. Similarly the passion of essays by Liu Xiaobo and Bo Yang, the baleful warnings of Lee Yee and Ni Kuang and the delicacy of Xi Xi’s vision of Hong Kong made what was essentially a mournful task also a reminder of what for many years I have called The Other China.

After Ghosts, Dreams, from the mid 1990s the main focus of my academic work was on dynastic China, in particular the Qing era. However, various other projects allowed me to continue producing work in the spirit of Seeds of Fire. These included the books Shades of Mao: the posthumous career of the great leader (1996) and In the Red: on contemporary Chinese culture (1999), the films The Gate of Heavenly Peace (1995, which I co-wrote) and Morning Sun (2003, which I co-directed and co-wrote), as well as a series of academic essays and translations through the 1990s and early 2000s.

Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium is the latest chapter in a story that began forty years ago with my contributions to Trees on the Mountain: Chinese Literature Today in 1983.

***

In response to a massacre of student protesters in 1926, Lu Xun wrote:

‘True fighters dare face the sorrows of humanity, and look unflinchingly at bloodshed. What sorrow and joy are theirs! But the Creator’s common device for ordinary people is to let the passage of time wash away old traces, leaving only pale-red bloodstains and a vague pain; and he lets men live on ignobly amid these, to keep this quasi-human world going. When will such a state of affairs come to an end?’

真的猛士,敢於直面慘淡的人生,敢於正視淋灕的鮮血。這是怎樣的哀痛者和幸福者?然而造化又常常為庸人設計,以時間的流駛,來洗滌舊跡,僅使留下淡紅的血色和微漠的悲哀。在這淡紅的血色和微漠的悲哀中,又給人暫得偷生,維持著這似人非人的世界。我不知道這樣的世界何時是一個盡頭!

In some respects, the series Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium is itself a memoir, a remembrance of things past. It also offers an account of some of the ‘pale-red bloodstains’ and ‘vague pain’ of the Xi Jinping era.

***

In late 2022, as China confronted the murderous Covid chaos resulting from the most egregious Mao-like act of Xi Jinping’s baleful decade in power, we marked the anniversary of Mao Zedong’s birth on 26 December 2022 in Tedium Continued — Mao more than ever. There we also announced that the present series will continue into 2023 thus making this issue of China Heritage Annual into a double issue covering the years 2022 and 2023.

‘Chinese Time’ is followed by ‘The View from Maple Bridge’, a three-part chapter marking the sixtieth anniversary of ‘The Maple Bridge Experience’ which evolved into a comprehensive system of social and political coercion and control. Maple Bridge is a central feature of Xi Jinping’s governance model.

— Geremie R. Barmé, Editor, China Heritage

Distinguished Fellow, Asia Society

1 January 2023

***

Related Material in Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium

- Chapter Twenty-three — Chinese Time, Part I: 新鬼舊夢— More New Ghosts, Same Old Dreams, 1 January 2023; Part II: 忘卻的紀念 — the struggle of memory against forgetting, 2 January 2023

- Chapter Three 迴 — Turn, Turn, Turn, 迴 The Tyranny of Chinese History, 10 March 2024; 旋 The Lugubrious Merry-go-round of Chinese Politics, 15 March 2024

- Chapter Twenty-one 醒 — Awakenings — a Voice from Young China on the Duty to Rebel, 14 November 2022

- Chapter Twenty-two 官逼民反 — Fear, Fury & Protest — three years of viral alarm, 27 November 2022 (see also Appendix XXIII 空白 — How to Read a Blank Sheet of Paper, 30 November 2022; Appendix XXIV 職責— It’s My Duty, 1 December 2022; and, Appendix XXV 贖 — ‘Ironic Points of Light’ — acts of redemption on the blank pages of history, 4 December 2022)

Tiananmen Gate, May 1989

Sitong Bridge, October 2022

The ‘Blank Paper Rebellion’ 白紙革命 of November 2022 is generally seen as having drawn inspiration from Peng Zaizhou (彭載舟, aka ‘Bridge Man’), a lone Beijing activist who called for the dismissal of Xi Jinping — the dictator and usurper — on 13 October 2022. It was a daring act on the eve of the Twentieth Congress of the Chinese Communist Party at which Xi would effectively be granted ‘terminal tenure’.

Peng’s one-man protest was the first of its kind in the Chinese capital since 23 May 1989. Then, at the height of the mass protests in Tiananmen Square, three young men from Liuyang county in Hunan province had unfurled banners on Tiananmen Gate reading:

五千年專制到此可以告一段落!

Time’s Up for Five Thousand Years of Autocracy; and,個人崇拜從今可以休矣

Enough of the Cult of Personality

The protesters then splattered the massive portrait of Mao Zedong hanging on the gate with eggs filed with pigment.

We used the image of the besmirched Mao as the cover illustration of New Ghosts, Old Dreams:

The three protesters were immediately detained by members of the Beijing Students’ Autonomous Federation. Although the students were demonstrating for democracy and freedom in the square, they were anxious to protect their credentials as ‘patriots’ and distance themselves from such an anarchic protest. The student vigilantes hastily organised a press conference at which they forced the Hunan protesters to confess their crime and admit that it had nothing to do with the protests. They were then handed over to the authorities. Mao’s portrait was replaced that same night.

The ‘Hunan Three’ — Yu Dongyue 喻東嶽, Lu Decheng 魯德成 and Yu Zhijian 余志堅 — spent years in prison. Following their release they found different ways to seek asylum in North America.

Following Peng Zaizhou’s protest at the Sitong Bridge Overpass in October 2022, some overseas Chinese commentators recalled the Hunan Three, although more generally their act of rebellion, as well as their suffering, go unmentioned.

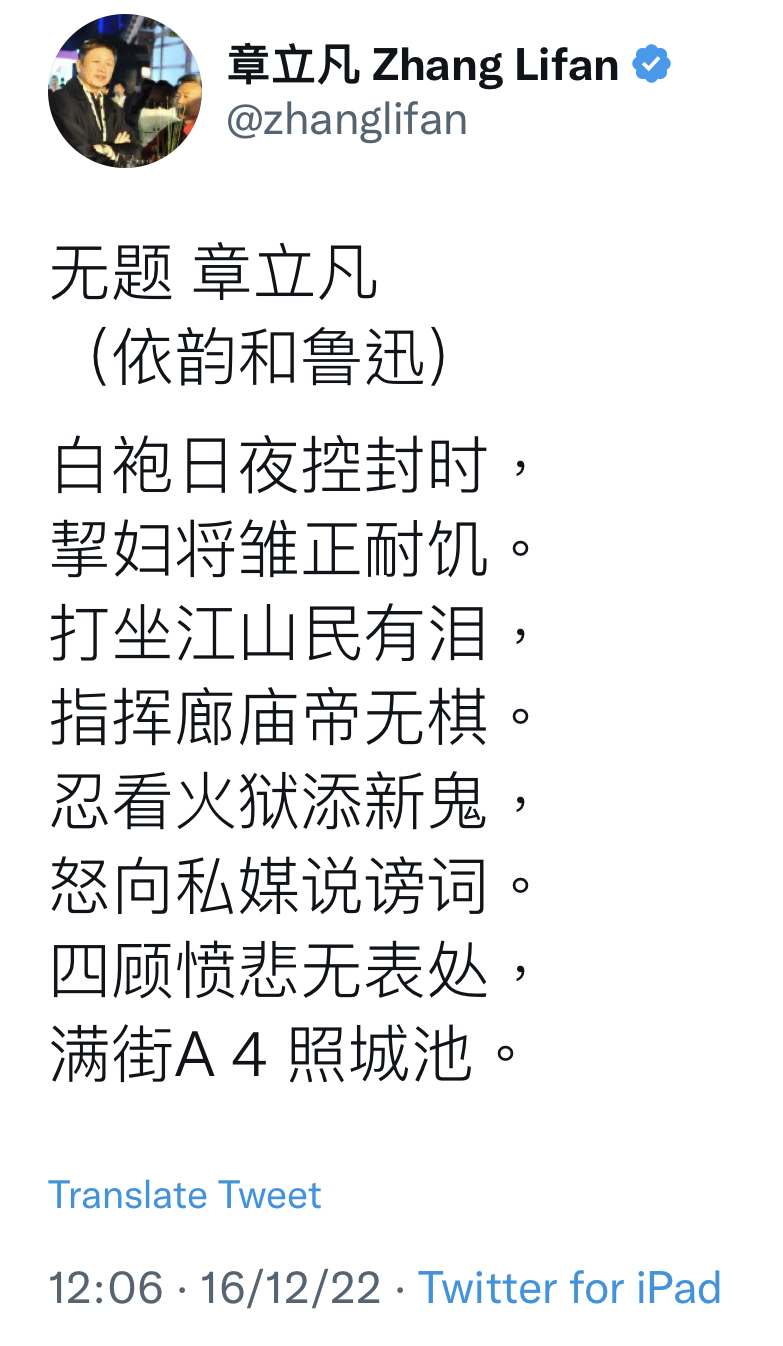

A Poem of Protest by Zhang Lifan

in Imitation of Lu Xun

***

Zhang’s poem accords with the style of Lu Xun’s original 1931 verse, although it is shorter in length and satirical in intent. Roughly translated it reads as follows:

The White Robes imposed lockdowns day and night

As families, wives and children suffered the pangs of hunger

You rule the Rivers and Mountains, heedless as the people shed tears

Though your commands from on high falter, yet you have no new moves

While we are forced to witness ever more souls consigned to hell

Resorting in our anger to social media to express contempt

With no place for us to express our indignation and our sorrow

City streets instead have filled with blank sheets of paper

— trans. G.R. Barmé

無題

章立凡

(依韻和魯迅)

白袍日夜控封時,挈婦將雛正耐飢。

打坐江山民有淚,指揮廊廟帝無棋。

忍看火獄添新鬼,怒向私媒說謗詞

四顧憤悲無表處,滿街A4照城池。

- Zhang Lifan (章立凡, 1950-) is the son of Zhang Naiqi (章乃器, 1897-1977), a prominent economist and progressive politician who played a key role in China’s post-1949 economy. A ‘Major Rightist Element’ purged when Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping crushed the Hundred Flowers Movement in 1957, Zhang was not formally exonerated until 1980. The fate of his father profoundly influenced Zhang fils. Because of his activism during the 1989 Protest Movement, Zhang Lifan was excommunicated by Official China. He has been an independent scholar ever since, speaking out whenever the opportunity has presented itself.

The Original Poem by Lu Xun

無題·慣於長夜過春時

魯迅

慣於長夜過春時,挈婦將雛鬢有絲。

夢里依稀慈母淚,城頭變幻大王旗。

忍看朋輩成新鬼,怒向刀叢覓小詩。

吟罷低眉無寫處,月光如水照緇衣。

***

Accustomed I’ve grown to the endless spring nights

Taking refuge with my wife and son, my hair gone grey

I see my weeping mother in my dreams

While they battle for control of the cities

I can but stand by, looking on as friends become new ghosts

I seek an angry poem from among the swords

My chant done, my brow furled, where will these poems go?

The icy moonlight covering me in a shimmering cloak of darkness.

— trans. GR Barmé

***

Source:

- Lu Xun, ‘Written for the Sake of Forgetting’ 為了忘卻的紀念, 7-8 February 1933

New Ghosts, Old Dreams

an excerpt from the Introduction (1992)

Geremie Barmé & Linda Jaivin

In early 1931, Lu Xun, one of China’s foremost literary figures, composed these lines upon hearing of the execution of five young writers. He mourned the murdered young as “new ghosts.”

In early June 1989, at least a thousand (and possibly many more) “new ghosts” were created when the Chinese government brutally crushed the peaceful student-led Protest Movement of that spring and began a political purge on a scale not seen in China since the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976).

New Ghosts, Old Dreams: Chinese Rebel Voices is an anthology of Chinese writings. Although we were inspired to compile this book by the events of 1989, we have not limited its contents to writings concerning them. Instead, through a selection of fiction, poetry, songs, essays, speeches, plays, petitions, reportage, documents, satire, newspaper articles, and even excerpts from the script of a television miniseries, we explore the social and cultural roots of the 1989 Protest Movement and provide a basis for understanding what has occurred in China since then.

Underlying many of the writings is a profound awareness of crisis — social, economic, political, cultural, and environmental — and an agonized concern for the dilemmas faced by China as it approaches the twenty-first century. The feeling that the Chinese government would not honestly confront the nation’s problems, many of them caused by its own mistaken or inept policies, was one factor that drove so many ordinary citizens in Peking, Shanghai, Chengdu, and other cities into the streets in the first half of 1989 to support what were initially student demonstrations.

The second part of the book’s title, “old dreams,” refers to the dreams of freedom and self-expression that Chinese individuals have pursued for millennia; the dreams of a modern, democratic, and equitable polity cherished by reformist intellectuals for nearly a century; and the dreams of being on an equal footing with the rest of humanity, true members of the international community.

While this book focuses on the sounds of discontent, protest, and despair that formed the chorus of Chinese urban life in the late 1980s, they also contain clear echoes of both the recent and distant past. There are resonances from the Tiananmen Incident of 1976, in which the popular mourning for Premier Zhou Enlai turned into a massive expression of protest against the Cultural Revolution, Jiang Qing, and indeed Mao Zedong himself. There are also reverberations from the Democracy Wall Movement of 1979, when thousands of young people in cities all over China demanded the redressing of past wrongs and called for increased democracy and human rights so that a disaster like the Cultural Revolution could never occur again. Indeed, the tenth anniversary of the imprisonment of Wei Jingsheng, a Democracy Wall activist and China’s most famous political prisoner, was one of the causes of the protests in 1989.

But 1989 was also the seventieth anniversary of the May Fourth Movement, which involved the first serious reevaluation of China’s traditional culture. In 1919 students demonstrated en masse for the first time against their new government, agitating for reform under the banner of “democracy and science.” Seventy years later, many Chinese felt that the issues of the May Fourth Movement were as relevant as they had ever been. Both the slogans of the original May Fourth Movement and references to it were prominent in the 1989 Protest Movement. Two members of the original May Fourth Movement generation, the Shanghai-based writer Ba Jin and the novelist and poet Bing Xin, even played a small but significant supporting role in the 1989 movement.

As the authors of the controversial television miniseries River Elegy put it, “It is as though so many things in China must start all over again from the May Fourth Movement.”

This “recycling” of history is one of the main themes of the book.

While Part IV (“Wheels”) is devoted to illustrating the cycles of recent Chinese history, other examples are inserted throughout the text. That is why, for example, in “The Cry,’ we use an essay about the dispersing of a student demonstration in 1919 just before touching on the subject of the massacre of 1989.

[Note: ‘Wheels’ is reproduced in ‘Chapter Three 迴 — Turn, Turn, Turn’ of Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium.]

We have chosen to call the events of the first half of 1989 the Protest Movement. Other writers, in Chinese and English, have variously called it the Student Movement, the Democracy Movement, or the Peking Spring. Although the street demonstrations of April and May 1989 were led to a great extent by students from Peking’s major educational institutions, they had already been developing from events earlier in the year (and even in I988) and from late April grew to become a widely based movement involving leading intellectuals and writers of several generations, journalists, central government cadres, factory workers, private entrepreneurs, members of nearly every profession from medical doctors to hotel chefs, and to some extent even peasants (who helped stop army trucks from getting into Peking from the surrounding countryside).

While the movement claimed democracy to be one of its major goals, it came to encompass grievances and demands as varied as its participants. Journalists demanded greater independence for the press, students lobbied for better conditions in the universities, intellectuals petitioned for a greater role in the polity, and nearly everyone wanted an end to official nepotism and corruption. For many, the protests were actually aimed against the inequalities and unsettling social changes resulting from the party’s 1980s reform policies themselves. The aims of the movement were vaguely described as freedom and democracy, but as some of the selections in “The Cry” illustrate, democracy was not one of the movement’s strongest points. Rather, its overriding theme was that of protest — against dictatorial one-party rule, a lack of both individual and group autonomy, economic and political mismanagement, and government unresponsiveness to its people’s concerns.

New Ghosts, Old Dreams is a sequel to an earlier anthology, Seeds of Fire: Chinese Voices of Conscience. Like Seeds of Fire, it contains selections or excerpts from a wide range of translated materials, put together in such a way as to illustrate common concerns or points of conflict and … is in essence an “anti-reader” on China but not an “anti-China” reader.

It attempts to expose Western readers to the Chinese world’s range of debate on her problems. In these pages there is much humor and some hope, but little optimism and few solutions. By the late 198os, China was facing a series of unprecedented crises in almost every sphere and optimism was restricted to propaganda and official speeches.

The Protest Movement, with its moving scenes of street marches and young and forceful leaders and the horrible massacre that followed, have lent the first half of 1989 a rather holy aura. It is easy, even tempting, to gloss over the more complicated reality — the motivating energy and humor, as well as the social and cultural complexities of the period.

New Ghosts, Old Dreams attempts to demonstrate that the elements of conflict present in 1989 predated the Protest Movement itself by many years, and that certain of these existed before Communist rule — some Chinese writers even feel they are indigenous to Chinese culture itself.

We have tried to offer Western readers a path through the labyrinthine intricacies of the Chinese cultural and political dilemma, presenting as their guides some of that nation’s most extraordinary contemporary writers.

We have made no attempt to be “representative.” The selections do not, by and large, address the situation in the Chinese countryside, for example, though the issues of unchecked population growth and impending environmental catastrophe raised by urban intellectuals are directly relevant to the future of all Chinese citizens and indeed to the rest of the world. Nor have we dwelt on the political infighting that has been part and parcel of every upheaval in Mainland Chinese history.

In general, we chose the materials translated here with an eye to content and style, and in both we have preferred the spicy over the bland, even if the bland is more typical of contemporary Chinese writing. It is a book intended, after all, to be provocative. We hope that allowing these Chinese men and women of conscience (and some of their detractors) to speak directly to Western readers will challenge accepted Western views on China, stimulate discussion, and create a greater awareness of China’s difficult situation.

There are no simple answers to the range of questions facing China in the 1990s that are posed in this anthology. But we do suggest that if one knows where China has been, it is a little easier to imagine where it is headed, or at least to understand where it is today.

— Canberra, Australia

***

‘There’s a sheet of blank paper in every heart.’

每人心中都有一張白紙。

— Gao Yu 高瑜, 2 January 2023