The refusal of one decent man

outweighs the acquiescence of the multitude.

千人之諾諾,不如一士之諤諤。

— Sima Qian, ‘Biography of Lord Shang’

司馬遷著 《史記 · 商君列傳》

trans. G.R. Barmé

In November 1978, Beijing audiences flocked to ‘Where Silence Reigns’ 於無聲處, a play first staged in Shanghai that addressed the question of the repression of the ‘Tiananmen Incident’ two years earlier. Over a number days in early April 1976, crowds had gathered in Tiananmen Square to mourn the recently dead Premier Zhou Enlai, and to protest against Mao and his radical supporters. By 1978, the protests were seen in a new light and China itself was undergoing a profound political and economic realignment.

The title of the play — ‘Where Silence Reigns’ — was inspired by a line in a classical Chinese poem by the country’s most famous modern writer, Lu Xun (魯迅, 1881-1936). The last line of Lu Xun’s untitled poem 無題, dated 30 May 1934, read 於無聲處聽驚雷, literally, ‘A startling clap of thunder is heard where silence reigns’. In other words: ‘a sudden sound breaks through the oppressive atmosphere’. As a whole, Lu Xun’s poem was a terse reflection of the seemingly hopeless state of China at the time; the famous last line extolled the promise of unexpected protest. Decades later, both Mao and his enemies — in particular disillusioned Red Guards — would quote the poem to affirm their claims about rebellion against repression and their hopes for a better future.

***

The play ‘Where Silence Reigns’ was staged at a momentous time in China’s modern history, a period that is being remembered and commemorated in many ways today, forty years later. Mao was dead, his radical revolutionary supporters had been arrested or sidelined, essential reforms of education and science were unfolding, men and women who had for decades been jailed, exiled or who were still living in the shadows were being exonerated, and the long-stagnant intellectual and culture life of the country were going through something of a ‘Beijing Spring’. The Party, the leaders of which were mired in the blood and violence of their misrule, was desperate to regain a measure of legitimacy and quickly. It rejected two decades of a destructive policy that favoured pitiless class struggle and universal ideological repression, and it turned its focus to rebuilding a crippled economy and improving the livelihoods of a people it had cruelly betrayed.

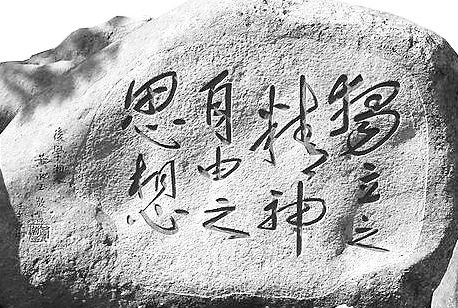

Silence or voicelessness, 無聲 wúshēng, was a theme of Lu Xun’s work, just as speaking out and being heard have been paramount concerns for Chinese men and women of conscience for the last forty years (as well as, when possible, the thirty years before that). In late July 2018, Xu Zhangrun (許章潤, 1962-), a professor of law at Tsinghua University in Beijing and a research fellow with the Unirule Institute of Economics, broke the silence that has spread under the draconian rule of Xi Jinping, the supreme party-state-army leader of the People’s Republic. In an eloquent and withering essay Professor Xu expressed his concerns about the state of Chinese politics and anxiety about the country’s future. China Heritage published an annotated English translation of that cri de coeur on 1 August under the title Imminent Fears, Immediate Hopes — a Beijing Jeremiad 我們當下的恐懼與期待. In the Editorial Introduction to the translation we observed that:

Xu Zhangrun’s powerful plea is not a simple work of ‘dissent’, as the term is generally understood in the sense of samizdat protest literature. Given the unease within China’s elites today, its implications are also of a different order from liberal pro-Western ‘dissident writing’. Xu has issued a challenge from the intellectual and cultural heart of China, or 文化中國, to the political heart of the Communist Party.

The author possibly sees himself within the ‘tradition of Confucian continuity’ 道統, the age-old stream of cultural becoming with which certain intellectuals identify. It is a tradition that long pre-dates Communist rule, and it is one that will continue to flourish long after they quit the historical stage. The content and powerful literary style of Xu’s ‘remonstrance’, as well as its tone of ‘moral outrage’ 義憤, not to mention the author’s scathing humour, will resonate deeply throughout the Chinese party-state system, as well as within Chinese society and among concerned citizens more broadly.

Xu Zhangrun’s reference to the Qin ruler, and his use of quotations and expressions drawn from Sima Qian (司馬遷, d. c.86 BCE), the Grand Historian of the Han dynasty who chronicled both the achievements and failures of early governance, is hardly accidental. The Party has declared itself, and its Leader, Xi Jinping, to be the nation’s Ultimate Arbiter and Sole Source of Authority 定於一尊, a term that Sima Qian first popularised when describing the autocracy of the Qin emperor. The Qin looms large in other ways as the relentless push by the Communist Party for ever greater unity, standardisation and a politically manipulated ‘rule of law’ resonates with Mao’s obsessions, as well as with the lessons of the Qin and its successor regimes.

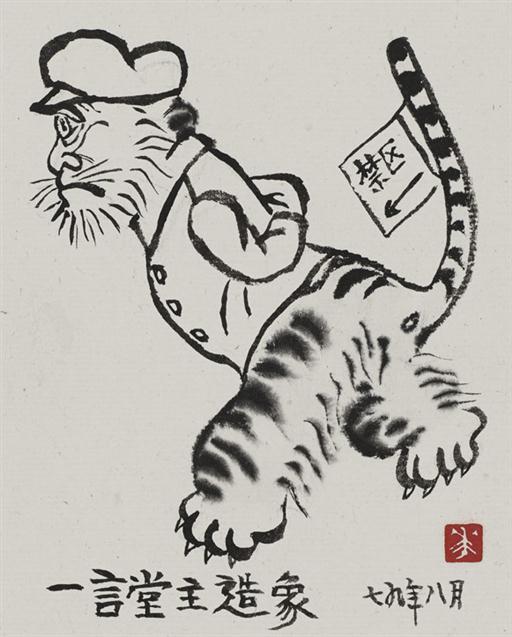

Since Mao found much in the rule of the First Emperor of which to approve, it is only fitting that critics of Xi Jinping not only detect the shades of the Great Leader in his inflated self-image (called a new personality cult, or ‘deification movement’ 造神運動), but also note traces in his behaviour of the Qin tyrant and his henchmen. As he wrote this essay in October 2018, Xu Zhangrun daresay had another lesson from the Qin era in mind — the advice of the brilliant and unscrupulous Li Si (李斯, 284-208 BCE), who counselled the First Emperor that, to prevent trouble, he should ‘burn the books and bury the scholars’ 焚書坑儒 (see China Heritage, 22 August 2017).

The Living Legacy of 1957

In 1957, as the Communist Party launched its second Rectification Campaign (the first was in Yan’an, from 1942-1944, discussed at length in our series Drop Your Pants!), it formulated six guiding principles for the nationwide movement. People were to be encouraged to speak up and help the Party, an organisation that Mao and his colleagues recognised was (now that it was in power) increasingly hampered by self-rewarded privileges and autocratic ways. So, it was declared that people should:

- Speak up without hesitation if they had complaints; 知無不言

- Be allowed to say everything they wanted to, 言無不盡

- Not be condemned for what they say. 言者無罪

On their side, Party cadres were to:

- Listen to all criticisms and take heed, 聞者足戒

- Accept those critiques that held true, 有則改之

- Work to improve regardless. 無則加勉。

Officially the aim of the movement was a dialectical dream, as well as being an impossibility, for as Mao himself said in July 1957, it was supposed to:

Foster a political environment that was centralised yet democratic, disciplined yet free; that forged a unified will while at the same time allowing for a sense of individual relaxation, in short, one that was both vital and lively’ 造成一個又有集中又有民主,又有紀律又有自由,又有統一意志、又有個人心情舒暢、生動活潑,那樣一種政治局面。

The resultant outpouring of discontent, however, was such that over 500,000 men and women from various backgrounds were condemned for what would be dubbed a ‘frenzied attack on the Party’ 瘋狂進攻. It was all a heinous plot by ‘Rightists’ and bourgeois elements determined to overthrow the Communist government. Acting on instructions from Mao Zedong, Deng Xiaoping oversaw a devastating purge of intellectual freedom and cultural life. Forty years later, in 1978, as the Party finally, and in desperation, redirected its energies towards economic reform, the vast majority of the condemned innocents of 1957 were exonerated. However, to this day, a small handful of ‘Rightists’ remain under a cloud, and, even in 1978, their crimes against the Party were held up as proof that the purge of 1957-1958, and Deng Xiaoping’s role in it, had been correct. Fateful decisions made then have not only transformed China’s economy, they have also stunted the country’s political growth. As a result, the long shadow of the past continues to darken the lives of men and women of conscience, social activists, cultural creators, thinkers, academics and students.

Another Lesson in New Sinology

Xu Zhangrun’s style of writing is clipped and concise. Not for him the clunky prose of New China Newspeak 新華文體, or the clumsy semi-European Chinese 歐化文體 generally favoured by academics and translators. Rather, his politically engaged literary gusto recalls the long written tradition of Chinese letters. For the last century, ‘half literary-half vernacular’ 半文半白 writing in a manner similar to this — although it might not always reflect Professor Xu’s panache — has been used to great effect by numerous authors, even as the vernacular language became the norm. It is a style that allows the writer to employ a range of classical devices — grammatical particles, turns of phrase, rhetorical devices (such as hidden, overt or oblique allusions 明喻、暗喻、借喻, etcetera), concise references — along with elements of modern prose and the unabashedly colloquial. Thus, in a passage elevated by historical allusions and literary turns of phrase, unexpected fusillades of common speech, slang or even vulgarities, punctuate and enliven the proceedings. This kind of writing has, and is, used by practiced writers to great effect, be it in advice papers to party-state leaders, in appeals to the public, when formulating dissenting views, or just in expressing penetrating views while drawing on hallowed traditions that address the mind as well as the heart. In this instance, as in his previous, extended essay, Xu Zhangrun’s voice conveys a powerful and daring message in what is often a deceptively breezy and sardonic tone. Careless readers, confident perhaps in deciphering lesser forms of written Chinese, may find themselves tempted to dismiss Xu’s writing as obscure and allusion-laden sophistry. They would be seriously mistaken to undervalue such work.

In advocating New Sinology 後漢學, we have repeatedly observed that if the world is to deal with China — and the multiplicity of ways that the Chinese universe expresses meaning (be it politically, intellectually, socially, economically or culturally) on a global scale — then surely a few of those who want to understand more than the formulaic kinds of ‘Translated China’ concocted by party-state propagandists and their in-house interpreters, might not merely be satisfied with keeping up with the latest political formulations, business palaver, advertising and pop culture memes or songs. They may also wish to delve with due seriousness into the millennia-old multiverse that underpins so many aspects of modern expression.

Similarly, for those who would take seriously expository Chinese prose — be the language of Communist officialdom, academia, the media, the arts (high and low) or the variegated world of dissent — an appreciation of the poetic, including the fact that the poetic and romantic suffuse expression at every turn — is of crucial importance. In a soci0-political and cultural landscape mediated by Chinese writing, as well as in the broad swathe of its audio-visual culture, the realm of poetry, or the mytho-poetic, has been transmogrified by countless writers, thinkers and educators from the dynastic era, through modern revolutions (Republican and Communist), to speak still with power to readers and audiences today. As we have pointed out in our series Drop Your Pants! this tradition can take the form of ‘revolutionary romanticism’, just as it finds expression among individuals who question, resist and challenge the Communist Party’s homogenising agenda.

In light of our long-term interest in New Sinology, we have taken the appearance of Professor Xu’s second essay to be what our American cousins would call a ‘teachable moment’. The bilingual version of Xu Zhangrun’s essay offered here includes a number of explanatory notes. In these we attempt both to convey the 微言大義 wēi yán dà yì, or ‘significant message contained in a subtle text’, and to offer by means of a gloss on select terms and expressions students of Chinese, native and foreign, some insight into the worlds beyond the words. Both the translation and the notes are based on my interpretation, and limited understanding, of a challenging original work by a learned, deeply humane and feisty writer of undoubted courage. Xu Zhangrun is, in the best sense of an ancient and hallowed word, 君子 jūnzǐ.

In keeping with the in-house style of China Heritage, Professor Xu’s original text is reproduced here in Regular Chinese orthography 正體字, rather than in the Crippled Characters 殘體字 officially promoted by the People’s Republic, and used in the original (for more on China’s ‘character confusion’, see The Chinese Character — no simple matter; and, 漢字簡化爭論).

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

10 November 2018

- Source: An edited version Xu Zhangrun’s article was first published on 6 November 2018, simultaneously appearing both on the website of the Unirule Institute of Economics 天則經濟研究所 and on the Chinese-language site of The Financial Times 金融時報. The following is a translation of the full, unedited version of the text, kindly provided by Professor Xu.

- For the translations by J.R. Hightower and Arthur Waley below, see John Minford and Joseph M. Lau, Classical Chinese Literature: An Anthology of Translations, Volume I: From Antiquity to the Tang Dynasty, New York: Columbia University Press, 2000

- As I have indicated in the above, this annotated translation is our latest Lesson in New Sinology. It is also included as essay XVII in The Best China.

Xu Zhangrun in China Heritage:

- Xu Zhangrun 許章潤, Imminent Fears, Immediate Hopes — a Beijing Jeremiad 我們當下的恐懼與期待, introduced and translated with notes by Geremie R. Barmé, China Heritage, 1 August 2018

- Xu Zhangrun 許章潤, To Summon a Wandering Soul, China Heritage, 28 November 2018

***

Explaining the Title

The title of Xu Zhangrun’s essay — 哪有先生不說話?!, literally, ‘When do teachers not want to speak up?!’ — is a line from a doggerel poem by the famous liberal scholar Hu Shi (胡適, 1891-1962). He was invited by Chiang Kai-shek, the leader of the Nationalist government, to a conference at the Cooling (Guling) hill station retreat of Lu Shan in Jiangxi province 江西廬山牯嶺 on the eve of formal war with Japan. The gathering included many other public figures, publishers, opinion makers and thinkers. The topic under discussion was the national crisis confronting the country and Hu made an impassioned speech in which he rejected much of the formulaic folderol of the others. A noted editor and publisher seated next to him dashed off a simple poem in admiration. Hu, famous for having encouraged the use of vernacular Chinese in writing poetry from the time of the literary revolution in 1917 (although the poems he produced were frequently lampooned as artless), immediately responded with an amusing reply (in my translation):

In springtime cats in heat do trill and meow,

While summer cicadas in chorus loudly sing,

All through the night frogs will simply croak,

And teachers, then? They just do their thing!

哪有貓兒不叫春,

哪有蟬兒不鳴夏,

哪有蛤蟆不夜鳴,

哪有先生不說話 ?!

— The Editor

Note: On Hu Shi’s later reticence, see the Translator’s Postscript below.

***

A Note on the Text

Professor Xu’s essay is presented twice: first, as in bilingual format, with each translated paragraph followed by the original. This is followed by an annotated version of the same material, with selected words, expressions and references in the Chinese original underlined and in bold, followed by ‘Translator’s Notes’ in information boxes.

Version One, Bilingual Text:

And Teachers, Then?

They Just Do Their Thing!

哪有先生不說話 ?!

Xu Zhangrun 許章潤

translated by Geremie R. Barmé

As I’ve been lecturing in the Tsinghua University School of Economics and Management Executive MBA program, my students have used [the dominant Mainland online Internet search engine] Baidu in the hope of learning more about the fellow who is instructing them. They are also interested in reading some of my other work as they feel it might be relevant to their own studies. Compared to people in my classes a few decades back, the majority of students today are in their late thirties or early forties, and there are pretty much even numbers of men and women. These are highly motivated individuals who are enthusiastic about their studies.

According to my dear friend Professor Donald Clarke, from the fateful day of 29 July 2018 [when the essay ‘Imminent Fears, Immediate Hopes‘ went live], online entries related to my name that previously numbered in the hundreds of thousands were suddenly reduced to a mere handful. To all intents and purposes, my existence online was extirpated. Over the next three months — that is until now — although a few dozen more entries mentioning my name have appeared online, but they shy away from substance and are for the most part are merely media reports and the like which just happen to contain some passing reference to my humble name. In effect, you can’t learn anything about me from them.

在經管學院為EMBA學員上課。他們搜索百度,希望多瞭解授課教師,閱讀與課程相關的教師著述。跟十來年前相比,今天學員年齡多在四十上下,男女搭配,精力充沛,尚存求知問道的熱情。據好友郭丹清教授(Donald Clarke)相告,時惟2018年7月29日,百度將我的詞條從數十萬刪到僅剩十條,算是悉數除祛。迄而至今,三月已過,猶有二三十條,羞羞答答,多為新聞報道,而牽連在下名字而已。如此,自然搜索不到任何信息。

It all has to do with that essay I published in late July — ‘Imminent Fears, Immediate Hopes’. Although I composed that work in response to a situation of pressing urgency with the aim of offering my suggestions, it was just as much a reflection of profound and long-term concerns. Overwhelming sentiments found expression therein; it has become more than evident that it also attracted unwelcome attention. In the normal course of events, it is commonplace for bookish scholars to give voice to their political views, and for those without political ambition to express all kinds of [arrant] opinion. It is simply par for the course; nothing more than jus natural — a natural right. But living as one does in a period of political irregularity during what is a momentous era of transformation, it was but inevitable that my writing was broadcast widely on the Internet, thereby offending against the taboos of the autocrats and causing discomfort to the hardened carapace of the totalitarians. Of course, it was also an affront to the ridiculously inexplicable and ham-fisted manifestations of the new personality cult and the deification of a certain individual. Eyes wide open I was fully aware of what I was doing and psychologically prepared for anything untoward that might befall me. That’s why I was not particularly perturbed by the initial wave of ‘gentle breezes and mild rains’ that consisted of the elimination of online material related to me and the blocking of my name. At first, I simply took no notice; moreover, it did not disturb me unduly. The wondrously efficacious methods of the age-old Qin tyranny are now but shabby techniques employed by the Newly Ennobled One. Although separated by two millennia, and despite variations on the theme, there has been no significant evolution [in how Qin methods are being imposed on today’s reality]. All in all, it comes down to the same old thing: ‘make people keep their mouths shut’. So what is happening to me is hardly a surprise!

事緣今年七月下旬,在下撰寫了「我們當下的恐懼與期待」一文,為當下計,作千歲憂。情非得已,情見乎辭,而終究彷彿情見勢屈。本來,書生論政,處士橫議,常規作業,天賦人權。但身處中國大轉型異常政治時段,其之流傳於網絡空間,觸犯專政禁忌與極權鱗甲,以及莫名其妙、土得掉渣的個人崇拜造神運動,勢不可免。我對此心知肚明,對於可能的橫逆也早有心理準備,故而對於刪除詞條、屏蔽姓名一類的「和風細雨」,根本不曾留意,更不會往心裡去。秦制妙法,新貴舊招,雖兩千年往矣,前後有別,卻了無進步,總不外鉗口二字,何足為奇。

Because this was brought to my attention by my students, I took a look at Baidu myself and was surprised to discover that online coverage of the Senior Bureaucrats and Theatricals who have been purged — people like the former security supremo Zhou Yongkang, Chongqing Party boss Bo Xilai, internet tsar Lu Wei and the Grand Qigong Master Wang Lin, you name it, all representatives of the varied dregs of society — is vast: they are all allowed tens of thousands of links. Even the infamous ‘Gang of Four’ — that unspeakably evil group — have entries so numerous as to be virtually beyond estimation.

經學員提醒,遂查百度,發現凡近年落馬的高官伶優,如周永康、薄熙來、魯緯與「王林大師」等三教九流,均有數萬詞條。所謂的「四人幫」,萬惡的四人幫,更是詞連山海,條接雲天,多到數不過來。

That material — an admixture of fact and fabrication — crowds the online world, yet it offers the devoted reader enough real information to piece together the historical truth. More significantly, all the links — regardless of whether they lead to denunciations or approbation — provide from various angles a vivid picture of that vicious era, along with details of the corruption of the soul of China and the crimes of the system itself. And there it is — all that information that is constantly reminding hundreds of millions of interested readers of the absurdity and pitilessness of history. More importantly, this plethora of material provides evidence enough, albeit in dribs and drabs, to constitute a flood of awareness that may provide people with the mental and spiritual wherewithal to resist anything like that happening again. Not only could it inoculate people so that they are alert to resisting autocracy, but also so that they may guard against and resist all autocratic behaviour [including the kind authored by the ‘Newly Ennobled One’, mentioned above].

它們林林總總,虛虛實實,多少給予讀者拼聯歷史真相的機會。更為重要的是,這些有關他們的詞條內容,從不同視角,討伐抑或崇仰,展示了酷烈時代的靈魂扭曲和體制罪惡,等於在向億萬讀者時時提示歷史的吊詭與無情,從而也就是在為避免悲劇重演,於涓滴匯流中積攢抵抗的精神資源。不只是抵抗某一種專斷,而是對於一切專斷的提防與抵抗。

Lingering at the crossroads of past and present the solitary individual may awaken to the fact that one can find commune in shared public rationality, and shine thereby a light on our shared humanity, in particular providing a better understanding both of the fragility as well as of the dark recesses of the human heart. It is this that better allows us to protect and maintain the domain of our own humanity, something that pulses in us with every breath and which is our constant reality. Moreover, this shared rationality is not merely of benefit to readers of Chinese, it has universal validity. Foremost, however, it must nourish the global realm of Chinese. This should be self-evident and go without saying: there should be room for such views as mine; it is well known, flowing waters do not stagnate; My Nation My People: herein lies the possibility for a true revival.

今昔流連之際,孤單的個體理性方始可能串聯並合成公共理性,於燭照人性中遵守常識,特別是明瞭人性的脆弱與幽暗,而護持我們生息其間、須臾不可離易的人世家園。而且,此非僅只惠及漢語讀者,而實具普世意義,但首先沾溉漢語世界,自是不言自明,則網開一面,流水不腐,吾族吾民,生機活現也。

In the online links related to the ‘Gang of Four’, there is much repetition of the Communist appraisal of these people, including the clichéd formulations that their actions amounted to nothing less than a ‘Catastrophe for the Nation and a Disaster for the People’, and that their crimes were so numerous that they were ‘beyond number and ability to record’. Reading this brought to mind those days of trembling fear in my youth [the author was born on 1962, and was therefore in his teens during the last years of Mao and the ‘Gang of Four’], as well as the breathless wonder of countless masses who watched the Show Trial of the Four, anguish and amusement commingling. Even more does one treasure the breathing space now in which no longer is there an endless succession of escalating of campaigns related to class struggle.

其中關於「四人幫」的一個詞條,重述當年中共的表述,指斥其犯行「禍國殃民」,而罪惡「罄竹難書」,令我不禁回想起少年時代的觳觫歲月,以及後來審判大戲登場時的萬眾屏息,悲喜交加,更加珍惜此刻這個不搞「一浪高過一浪」階級鬥爭運動的喘息時光。

They were ‘A National Catastrophe and a Disaster for the People’, moreover, their crimes are beyond calculation and could fill libraries. Nonetheless, there are tens of thousands of Baidu entries on their lives and detailing their actions, and in some cases links to their writings [in particular those of Zhang Chunqiao and Yao Wenyuan] are available. For this worthless scholar, one who has laboured for over three decades to earn a modest living, a person who is ‘on the frontline struggle of the classroom’, no matter how much of a catastrophe I might threaten to create, it will never be on a national scale, and regardless of the disaster that I may present, at most it will corrupt but a few students. Why, therefore, have I been stricken from the Internet? Or, should I ask: do you honestly believe you can simply make me evaporate and disappear entirely from the ranks of humanity?

他們「禍國殃民」,進至於「罄竹難書」,尚有數萬詞條展示其生平,羅列其行止,甚至刊布其作品。在下一介教書匠,三十多年里,但求溫飽,「奮戰在教學第一線」,若禍則禍不及於國,要殃也只能殃及三、五學子,何至於將我從網上抹掉,或者,似乎認為如此這般就能將我從人間蒸發。

The only explanation I can think of is that a low-level tradesman in pedagogy like me — one who has no taste for street fighting and with no training in the use of any weapons — is actually regarded as being worst that the ‘National Catastrophe and Disaster for the People’ that was the ‘Gang of Four’.

唯一的解釋是,我這個底層教書匠,不嗜打架,也不會任何一件兵器,竟然比「禍國殃民」的「四人幫」還壞。

Secretaries draft the speeches that the bureaucrats read out. There’s one joke that goes:

A sentence at the bottom of the printed page of speech drafted by a functionary ends with a rhetorical question, but the particle word and question mark at the end of the sentence — 麼? [which turns the proceeding statement into a rhetorical question] — happened to be printed on the top of the following page. The bureaucrat making the speech mindlessly recites down to what he believes is the end of the speech, concluding with the bottom of the page. Then, looking up at an expectant audience, he pauses for a moment, and only then turns over the page. Upon discovering the missing word he reads it out with redoubled gusto. The actual effect was the equivalent of ‘Zhou Yongkang (although the name could be that of any equivalent character, such as Wu Yongkang, Zheng Yongkang, Wang Yongkang, or even Sima Yongkang) is not evil ﹫#$%& …… is an incorrect statement!’

Extrapolating from this one can come up with other examples, such as: ‘I am more evil than the “Gang of Four” ﹫#$%&…… is an incorrect statement!’ or ‘You people are competing in the stakes of evil with the “Gang of Four” ﹫#$%&…… is an incorrect statement!’

秘書寫稿子,官員念稿子。有一個笑話說的是,講話稿的頁末一句是個疑問句,因排版原因,語助詞連同疑問號「麼?」印在了下一頁。官員念完這句,環視台下,少頃,莊重翻頁,再補充上語助詞,音調鏗鏘,致使現場效果成了「周永康/吳永康/鄭永康/王永康/司馬永康不是一個壞人﹫#$%&……麼?」轉借此例,在下接續而來的造句作業是:「我比’四人幫’還壞﹫#$%&……麼?」抑或,「你們要和‘四人幫’比壞﹫#$%&……麼?」

In a season of discontent and buffeted by winds from all directions, silence now reigns in our realm. What remains is acquiescence of the multitude, such arrant stupidity and, grotesque folly. But as for my part, as a lowly pedagogue, and as Mr Hu Shi remarked over eighty years ago: ‘And teachers, then? They just do their thing!’ [that is, teachers speak out, and they’ll just keep on doing so]. But when speaking out one must make oneself heard, for only then can there be some kind of dialogue or exchange. Only then can we break free of the solitude of self and enjoy the realities of community, and thereby affirm our humanity. Moreover, our shared community, only through shared community, can we enjoy freedom. It is for this reason that Baidu’s effacement results in a sense of impotent resignation for we have no choice but to rely on the services of Baidu, this Leviathan. So how can one overlook such blanket obliteration?! How can one help from taking it personally?! To do otherwise, would require one to blind one’s eyes and dull one’s mind. Over time, [as a result of the media being stymied like this] the nation may will find itself reduced to the mindless state of swine.

只是值此八面來風時節,欲令天下無聲,惟剩諾諾,何其愚妄,何其滑稽。畢竟,身役教書匠,如八十多年前適之先生所言:「哪有先生不說話?!」而說話就得讓人聽見,才能構成對話與交談,讓我們擺脫孤立的私性狀態,獲得公共存在,保持人性。進而,我們的公共存在狀態,也唯有這種公共存在狀態,才賦予我們以自由。職是之故,對於百度的封殺,對於造成我們無奈只能用百度而無所選擇的那個巨靈,豈能不留意?!又豈能不往心裡去?!否則,閉目塞聰,一個民族可能慢慢會變成一頭豬。

And, it is for this reason that I now address you directly — that’s right, those of you who play the handmaidens to tyrants and help the devil do his handiwork — I say to you, including those who don’t mind getting their hands dirty by deleting and blocking online information, and especially those of Black Hearts who formulate such policies and issue instructions: I harbour no hatred for you; for all of you all I have nothing but sympathy. And let me add, you are still young and daresay possessed of a measure of talent; why not try finding a decent profession so you can make an honest living?

因而,我對你們,助紂為虐,為虎作倀,包括不嫌手臟而下手刪除、屏蔽信息的,特別是不怕心黑做出類此決策下達指令的,並無仇恨,只有滿腔的同情!再說了,年紀輕輕,身懷長技,為何不另找一個乾淨營生?

We are all living in bleak darkness; there is no dim light of dawn ahead. We can but extend a hand of sympathy [to each other] and then, hand in hand, we may advance through all treacherous barriers to achieve release.

Love and life are ours, yet while there are entertaining distractions the rattle of sabres is also heard, but let us not forget the heart-rending beauties of this autumnal season. I have but limited desires and ability. Don’t forget: ‘look, which blossoms open in the morning, what flowers flourish at night’. Friend: how entrancing yet is this, our human existence.

我們同處幽冥之中,不見熹微,唯以同情援手,手牽手,才能穿過這重重關隘而獲救。

暮雲朝雨,琴劍匆匆,秋意爛漫,千江一瓢,「看那花開在早晨,再看那花開在夜晚」,朋友,人間是多麼的美好。

29 October 2018

The Studio That Isn’t

Tsinghua University

2018年10月29日於清華無齋

Version Two, Bilingual Text with Notes:

And Teachers, Then?

They Just Do Their Thing!

哪有先生不說話 ?!

Xu Zhangrun 許章潤

translated and annotated by Geremie R. Barmé

As I’ve been lecturing in the Tsinghua University School of Economics and Management Executive MBA program, my students have used [the dominant Mainland online Internet search engine] Baidu in the hope of learning more about the fellow who is instructing them. They are also interested in reading some of my other work as they feel it might be relevant to their own studies. Compared to people in my classes a few decades back, the majority of students today are in their late thirties or early forties, and there are pretty much even numbers of men and women. These are highly motivated individuals who are enthusiastic about their studies.

According to my dear friend Professor Donald Clarke, from the fateful day of 29 July 2018 [when the essay ‘Imminent Fears, Immediate Hopes‘ went live], online entries related to my name that previously numbered in the hundreds of thousands were suddenly reduced to a mere handful. To all intents and purposes, my existence online was extirpated. Over the next three months — that is until now — although a few dozen more entries mentioning my name have appeared online, but they shy away from substance and are for the most part are merely media reports and the like which just happen to contain some passing reference to my humble name. In effect, you can’t learn anything about me from them.

在經管學院為EMBA學員上課。他們搜索百度,希望多瞭解授課教師,閱讀與課程相關的教師著述。跟十來年前相比,今天學員年齡多在四十上下,男女搭配,精力充沛,尚存求知問道的熱情。據好友郭丹清教授(Donald Clarke)相告,時惟2018年7月29日,百度將我的詞條從數十萬刪到僅剩十條,算是悉數除祛。迄而至今,三月已過,猶有二三十條,羞羞答答,多為新聞報道,而牽連在下名字而已。如此,自然搜索不到任何信息。

除祛 chúqū: to exorcise, obliterate or otherwise do away with a malignant influence, often due to fear

羞羞答答 xiūxiū dādā: a term from traditional theatre meaning bashful, shy or given to avoiding embarrassment

在下 zàixià: ‘unworthy self’, or ‘I/ me/ my’. This expression is frequently used in martial arts literature, as well as in traditional opera. 在下名字: my humble name, or worthless self

It all has to do with that essay I published in late July — ‘Imminent Fears, Immediate Hopes’. Although I composed that work in response to a situation of pressing urgency with the aim of offering my suggestions, it was just as much a reflection of profound and long-term concerns. Overwhelming sentiments found expression therein; it has become more than evident that it also attracted unwelcome attention. In the normal course of events, it is commonplace for bookish scholars to give voice to their political views, and for those without political ambition to express all kinds of [arrant] opinion. It is simply par for the course; nothing more than jus natural — a natural right. But living as one does in a period of political irregularity during what is a momentous era of transformation, it was but inevitable that my writing was broadcast widely on the Internet, thereby offending against the taboos of the autocrats and causing discomfort to the hardened carapace of the totalitarians. Of course, it was also an affront to the ridiculously inexplicable and ham-fisted manifestations of the new personality cult and the deification of a certain individual. Eyes wide open I was fully aware of what I was doing and psychologically prepared for anything untoward that might befall me. That’s why I was not particularly perturbed by the initial wave of ‘gentle breezes and mild rains’ that consisted of the elimination of online material related to me and the blocking of my name. At first, I simply took no notice; moreover, it did not disturb me unduly. The wondrously efficacious methods of the age-old Qin tyranny are now but shabby techniques employed by the Newly Ennobled One. Although separated by two millennia, and despite variations on the theme, there has been no significant evolution [in how Qin methods are being imposed on today’s reality]. All in all, it comes down to the same old thing: ‘make people keep their mouths shut’. So what is happening to me is hardly a surprise!

事緣今年七月下旬,在下撰寫了「我們當下的恐懼與期待」一文,為當下計,作千歲憂。情非得已,情見乎辭,而終究彷彿情見勢屈。本來,書生論政,處士橫議,常規作業,天賦人權。但身處中國大轉型異常政治時段,其之流傳於網絡空間,觸犯專政禁忌與極權鱗甲,以及莫名其妙、土得掉渣的個人崇拜造神運動,勢不可免。我對此心知肚明,對於可能的橫逆也早有心理準備,故而對於刪除詞條、屏蔽姓名一類的「和風細雨」,根本不曾留意,更不會往心裡去。秦制妙法,新貴舊招,雖兩千年往矣,前後有別,卻了無進步,總不外鉗口二字,何足為奇。

千歲憂 qiān suì yōu: this expression is taken from one of the ‘Nineteen Old Poems’ 古詩十九首, a famous series by different hands dating from just before the start of the Christian era. As John Minford has noted: ‘These poems had an enormous influence on all subsequent poetry, and many of the habitual clichés of Chinese verse are taken from them’. ‘A thousand year’s sorrow’ is from the second line of the poem known in Chinese as ‘The years of a lifetime do not reach a hundred’ 生年不滿百, which the translator Arthur Waley titles ‘Take a Lamp and Wander Forth’:

The years of a lifetime do not reach a hundred,

Yet they contain a thousand years’ sorrow.

When days are short and the dull nights long,

Why not take a lamp and wander forth?

If you want to be happy you must do it now,

There is not waiting till an after-time.

The who’s loath to spend the wealth he’s got

Becomes the laughing-stock of after ages.

It is true that Master Wang became immortal,

But how can we hope to share his lot?

生年不滿百,

常懷千歲憂。

晝短苦夜長,

何不秉燭遊。

爲樂當及時,

何能待來茲。

愚者愛惜費,

但爲後世嗤。

仙人王子喬,

難可與等期。

情見乎辭 qíng xiàn hū cí: ‘sentiments find expression in words’. Here 見 is pronounced xiàn not jiàn and means ‘to appear’ or ‘to manifest’. This well-known expression comes from the I Ching, or Book of Change, an ancient divinatory text and one of the Confucian classics. The original reads: 聖人之情見乎辭。It is proceeded by 情非得已 qíng fēi dé yǐ or ‘overwhelming sentiments’, which is also a well known line. The phrases share the word 情 qíng, one of the richest and most complexly nuanced terms in the Chinese language. Its meanings cover such ideas as ‘disposition’, ‘feelings’, ‘sentiment’ or, as one writer puts it, ‘the way reality registers on us’. For a detailed discussion of 情 qíng, see ‘The Definition of “Qing” ’ in Anthony C. Yu 余國藩, Rereading the Stone: Desire and the Making of Fiction in Dream of the Red Chamber (Princeton, 1997), pp.56-66

情見勢屈 qíng jiàn (or xiàn, as in 現) shì qū: an expression from the Han-dynasty historian Sima Qian that literally means ‘the situation revealed, the initiative is lost’, or ‘the enemy is on to me’

書生論政 shūshēng lùn zhèng, 處士橫議 chǔshì héng yì: together these well-known fixed expressions mean: ‘learned people who have no interest in officialdom are much given to casual comment on the politics of the day’. Here the author identifies with ‘bookish individuals’ 書生 shūshēng and ‘scholars with no bureaucratic aspirations’ 處士 chǔshì. Both 論政 lùn zhèng and 橫議 héng yì refer to the practice of commenting on politics without concern for official niceties. 處士橫議 chǔshì héng yì occurs in Mencius 《孟子 · 滕文公下》: 聖王不作,諸侯放恣,處士橫議, translated by James Legge as:

Once more, sage sovereigns cease to arise, and the princes of the States give the reins to their lusts. Unemployed scholars indulge in unreasonable discussions.

In the Xi Jinping Epoch, just as in the past, the Communists dismiss any political discussions that are not ‘on message’ as dangerous ’empty talk’ 空談 kōng tán or 清談 qīng tán, ‘prattle’. The slogan ’empty talk [idle discussion] harms the nation, practical action will ensure it thrives’ 空談誤國, 實幹興邦 kōng tán wù guó shí gàn xīng bāng was promoted by Deng Xiaoping during his 1992 Southern Tour. That trip to key centres of economic reform was aimed at lifting the country out of its post-1989 economic doldrums and in the process Deng made it clear that it was time to bring an end to futile ideological disputes and encourage further radical economic experimentation. In particular Deng condemned disruptive ideological nitpicking about the dangers of socialist capitalism as ’empty talk harming the nation’.

From 2011, Xi Jinping revived the expression to censor not only dissidents, but also policy experts and academics who had the gall to challenge the Party (and later Xi Jinping Thought itself). Independent political discussion and the expression of views that disrupt the status quo — or simply mock it — were decried as ‘pure talk’ 清談 from the Wei-Jin 魏晉 period (third to fifth century CE), a time when the freewheeling Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove 竹林七賢 flourished. ‘Idle discussions’ 清談, as well as ‘principled or judicious debate’ 清議 qīng yì — common among traditional scholar-bureaucrats who decried political hypocrisy and imperial follies in the late Ming (sixteenth century) and late Qing (nineteenth century) — are also policed by China’s modern party-state.

The various expressions related to unruly speech bring to mind Simon Leys’s who spoke of ‘the scholars of Donglin 東林黨 (a group of intellectuals at the close of the Ming period, who risked the worst kinds of torture by making political criticisms of a corrupt imperial regime).’ Their tragic destiny was prefigured in the famous poetic lines, translated by Leys:

Do not believe that men who wield the pen only know how to chatter emptily 莫謂書生空議論,

When they are under the executioner’s axe, they know how to show their red blood! 頭顱擲處血斑斑。

— quoted in It’s Time to Talk About

Evening Talks at Yanshan,

China Heritage, 20 July 2018

天賦人權 tiān fù rénquán: ‘inalienable right’. This concept is anathema to the Communists, particularly in the three decades since the suppression of the 1989 Protest Movement. Given a lack of inalienable rights in China, critics of the party-state say the country only has 人賦人權 rén fù rénquán, ‘rights bestowed by man’

異常政治時段 yìcháng zhèngzhì shíduàn: ‘a period of political abnormality’ or ‘irregularity’, in other words, Xi Jinping’s terminal tenure. This was legislated in early 2018 when China’s party-state controversially abandoned strict limits on the tenure of the country’s highest officeholders, introduced under nearly three decades earlier Deng Xiaoping (one might observe that, although the new rules applied to the titular heads of the Chinese government, Deng himself reigned as something of an ‘uncrowned king’ 無冕王 until his demise in 1997). Professor Xu pointedly addressed this issue, and suggested how best it might be resolved, in Imminent Fears, Immediate Hopes

極權鱗甲 jíquán línjiǎ: ‘hardened carapace of the totalitarians’. Here the author combines the modern political term ‘totalitarian’ jíquán, with 鱗甲 línjiǎ, an ancient kind of body armour made up of overlapping metal scales. In his prose, the writer often employs words and expression that contrast the contemporary with the ancient, with pointed rhetorical effect

土得掉渣 tǔde diàozhā: a colloquial expression, literally ‘so sodden that the earth is dropping off it’, meaning ‘embarrassingly crass’, ‘laughably vulgar’, ‘low-class’ or ‘uncouth’

個人崇拜 gèrén chóngbài: ‘personality cult’. In 1956, the Soviet Union, the sociality country on which China’s People’s Republic was modelling itself, denounced the personality cult surrounding its dead leader, Joseph Stalin. The newly appointed Communist leader, Nikita Khrushchev, addressed the issue in a major report to the Party titled ‘On the Cult of Personality and Its Consequences‘. Mao and his cohort, including Liu Shaoqi (the man who created the term ‘Mao Zedong Thought’) and Deng Xiaoping, rejected this attack on Stalin. Twenty five years later, following Mao’s death and the end of his extremist politics, Deng reneged on his earlier sycophantic stance and, in August 1980, when discussing how China might best avoid one-man rule and political ructions like the Cultural Revolution in the future, he said :

This issue has to be addressed by tackling the problems in our institutions. Some of those we established in the past were, in fact, tainted by feudalism, as manifested in such things as the personality cult, the patriarchal ways or styles of work and the life tenure of cadres in leading posts.

— Deng Xiaoping, Answers to the Italian Journalist

Oriana Fallaci, 21st and 23rd August 1980

造神運動 zàoshén yùndòng: the manufacturing of divinity or apotheosis. From the time of de-Maoification in the 1980s, the elevation of Mao to godlike stature was widely condemned both by the Party, and more broadly. In Shades of Mao: the posthumous career of the Great Leader (Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 1996), I discussed the limitations of those efforts and speculated on the afterlife of Mao and the personality cult in modern China. For more on Xu Zhangrun’s views on the Xi Jinping personality cult, see his Imminent Fears, Immediate Hopes

橫逆 hèng nì: misfortune or, in keeping with its use in the Confucian classic Mencius, ‘perversity and unreasonableness’. The term appears in a crucial passage in the ‘Lilou Chapter’ of Mencius:

Mencius said, ‘That whereby the superior man is distinguished from other men is what he preserves in his heart — namely, benevolence and propriety. The benevolent man loves others. The man of propriety shows respect to others. He who loves others is constantly loved by them. He who respects others is constantly respected by them. Here is a man, who treats me in a perverse and unreasonable manner. The superior man in such a case will turn round upon himself, “I must have been wanting in benevolence; I must have been wanting in propriety — how should this have happened to me?” He examines himself, and is specially benevolent. He turns round upon himself, and is specially observant of propriety. The perversity and unreasonableness of the other, however, are still the same. The superior man will again turn round on himself, “I must have been failing to do my utmost.” He turns round upon himself, and proceeds to do his utmost, but still the perversity and unreasonableness of the other are repeated. On this the superior man says, “This is a man utterly lost indeed! Since he conducts himself so, what is there to choose between him and a brute? Why should I go to contend with a brute?” Thus it is that the superior man has a life-long anxiety and not one morning’s calamity.’

孟子曰:君子所以異於人者,以其存心也。君子以仁存心,以禮存心。仁者愛人,有禮者敬人。愛人者人恆愛之,敬人者人恆敬之。有人於此,其待我以橫逆,則君子必自反也:我必不仁也,必無禮也,此物奚宜至哉?其自反而仁矣,自反而有禮矣,其橫逆由是也,君子必自反也:我必不忠。自反而忠矣,其橫逆由是也,君子曰:此亦妄人也已矣。如此則與禽獸奚擇哉。於禽獸又何難焉。是故君子有終身之憂,無一朝之患也。

和風細雨 hé fēng xì yǔ: literally, ‘gentle breeze and mild rain’. Climactic and meteorological expressions, mostly drawn from the tradition, are common in Communist parlance, and they generally convey a political message.

In late 1956, during the last period of true openness and contestation in the political and intellectual life of the People’s Republic when the Communists invited public criticism of their style of government, Mao Zedong said:

We are in favour of the method of the ‘gentle breeze and mild rain’ [和風細雨], and though it is hardly avoidable that in a few cases things may get a little too rough, the over-all intention is to cure the sickness and save the patient, and truly to achieve this end instead of merely paying lip-service to it. The first principle is to protect a person, and the second one is to criticize him. First he is to be protected because he is not a counter-revolutionary. This means to start from the desire for unity and, through criticism and self-criticism, arrive at a new unity on a new basis. Within the ranks of the people, if we adopt the method of both protecting and criticizing a person who has made mistakes, we shall win people’s hearts, be able to unite the entire people and bring into play all the positive factors among our 600 million people for building socialism.

我們主張和風細雨,當然,這中間個別的人也難免稍微激烈一點,但總的傾向是要把病治好,把人救了,真正要達到治病救人的目的,不是講講而已。第一條保護他,第二條批評他。首先要保護他,因為他不是反革命。這就是從團結的願望出發,經過批評和自我批評,在新的基礎上達到新的團結。在人民內部,對犯錯誤的人,都用保護他又批評他的方法,這樣就很得人心,就能夠團結全國人民,調動六億人口中的一切積極因素,來建設社會主義。

— Speech at the Second Plenary Session

of the Eighth Central Committee of the

Communist Party (15 November 1956)

Following this period known as the ‘Double Hundred’ campaign — the slogan was ‘Let a Hundred Flowers Blossom and a Hundred Schools of Thought Contend’ 百花齊放,百家爭鳴 — during which, as we just noted, intellectuals, political figures, academics, workers, students and others were encouraged to offer their frank criticisms of the way the Communist Party was ruling China, from mid 1957 Mao and his notorious bureaucratic manager, Deng Xiaoping, imposed a policy of ‘harsh winds and pelting rain’ 急風暴雨 jí fēng bào yǔ, that is, remorseless ideological struggle involving mass denunciations, media attacks and workplace vilification. The resulting purge of the Party’s critics — through exile, demotion, jailing, ostracism and a myriad of other administrative and police punishments — effectively crippled the nation’s intellectual and cultural life for the next two decades (for the Party’s account of this climatic change, see ‘1957年:從「和風細雨」到「急風暴雨」’, 新華網, 10 August 2009).

In 1979, at the height of the Chinese Communist post-Mao self-awareness, Deng Xiaoping used a four-character sentence when he emphasised the ruling party’s need ‘to open wide the avenues of expression’ 廣開言路 guǎng kāi yán lù. For example, in an opening address titled The United Front and the Tasks of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference In the New Period 新時期的統一戰線和人民政協的任務, given on 15 June 1979, Deng declared that:

We must give scope to the free airing of views and make full use of all talents. We must uphold the principle of the ‘three don’ts’: don’t pick on others for their faults, don’t put labels on people, and don’t use a big stick. And we must encourage the full expression of opinions, demands, criticisms and suggestions from all quarters, so that the government can benefit from them, promptly discover and correct its own shortcomings and mistakes and push forward all phases of our work.

我們要廣開言路,廣開才路,堅持不抓辮子、不扣帽子、不打棍子的「三不主義」,讓各方面的意見、要求、批評和建議充分反映出來,以利於政府集中正確的意見,及時發現和糾正工作中的缺點、錯誤,把我們的各項事業推向前進。

As is always the case with the Communists, however, this came with a crucial caveat, one of particular significance in light of the fact that Deng was addressing an audience that included many surviving ‘democratic personages’ 民主人士, along with the rump of the country’s non-Communist political parties 民主黨派, that he and Mao had all but obliterated in 1957. With the lingering legacy of that campaign in mind (not to mention the fact that he had only recently refused to exonerate the small handful of remaining ‘Rightists’ defamed in 1957), Deng reminded his listeners — and, by extension, the young dissidents recently swept up in the purge of outspoken Democracy Wall activists — that:

To achieve the Four Modernizations, it is essential that we strengthen the ideological and political education of the whole people, while maintaining the proletarian dictatorship over the handful of anti-socialist elements.

為了實現四個現代化,在堅持對極少數反社會主義分子實行無產階級專政的同時,需要在人民內部廣泛地加強思想政治教育。

秦制妙法,新貴舊招 Qín zhì miàofǎ, xīn guì jiù zhāo: the expression ‘Qin system’ 秦制 Qín zhì or ‘Qin-era form of rulership’ has had negative connotations since the fall of the Qin dynasty and throughout most of Chinese history, at least until the time of Mao Zedong and the Communists. It is also frequently used as a shorthand for the imperial system as a whole, and China’s autocratic political tradition. Here, the author pairs it with the expression 妙法 miàofǎ, long ago used to translate the Sanskrit term sad-dharma सद्धर्म, ‘the wondrous or good dharma’ or method, used in the title of one of the most famous Northern Buddhist sūtras. Here it means a canny approach or a deviously clever way of doing things. It is paired with 新貴舊招 xīn guì jiù zhāo, literally, ‘well-worn trickery of new rulers’. The term 新貴 xīn guì means ‘nouveau nobility’ or, to be more precise, ‘that recently elevated [head] noble’, that is Chairman of Everything Xi, who we refer to as the ‘Newly Ennobled One’. The word 招 zhāo is often used to describe complex martial arts moves involving hands and fists, and by extension trickery or prestidigitation. New and old are thus juxtaposed in a satirical manner — the tired methods of autocracy married to the skulduggery of contemporary power-mongers.

It is worth noting here, that given the educational limitations of the Cultural Revolution generation of China’s present leaders, it is likely that, despite their predilection for reciting speeches punctuated with classical quotations, they would probably find Xu Zhangrun’s allusion-laden literary prose challenging.

鉗口 qián kǒu, also 箝口, to close the mouth tightly, or to have someone silenced. This shorthand stands for 鉗口結舌 (also written 箝口結舌 or 緘口結舌), that is ‘to seal the mouth and tie the tongue in a knot’. Through the ages, while some wise souls repeatedly cautioned against it, others have been enthusiastic advocates.

What is noteworthy about Professor Xu’s outspokenness in 2018, and the defense of liberal ideas and economic policies by other members of the Unirule Institute of Economics in Beijing, is not that such views are uncommon within the intelligentsia — there is anecdotal evidence to suggest that they are — but that the academic liberal stars, as well as their fellow internationally fêted champions of left-wing thought, have been egregious in their silence. In their 1990s to 2012 heyday, these men and women enjoyed both state largesse and overseas kudos. As the limited freedom of expression grudgingly tolerated by Xi Jinping’s predecessors gave way to ever greater ideological policing, and while academic independence was being further eroded, the studied circumspection of this generally loquacious and always opinionated clutch of academicians has been noteworthy, if unsurprising. (For more on this topic, see Elephants and Anacondas, China Heritage, 28 June 2017)

Because this was brought to my attention by my students, I took a look at Baidu myself and was surprised to discover that online coverage of the Senior Bureaucrats and Theatricals who have been purged — people like the former security supremo Zhou Yongkang, Chongqing Party boss Bo Xilai, internet tsar Lu Wei and the Grand Qigong Master Wang Lin, you name it, all representatives of the varied dregs of society — is vast: they are all allowed tens of thousands of links. Even the infamous ‘Gang of Four’ — that unspeakably evil group — have entries so numerous as to be virtually beyond estimation.

經學員提醒,遂查百度,發現凡近年落馬的高官伶優,如周永康、薄熙來、魯緯與「王林大師」等三教九流,均有數萬詞條。所謂的「四人幫」,萬惡的四人幫,更是詞連山海,條接雲天,多到數不過來。

落馬的高官伶優 luòmǎde gāoguān língyōu: ‘Senior Bureaucrats and Theatricals’. This expression is paired with 三教九流 sān jiào jiǔ liú, which now generally has a negative connotation, translated as ‘the varied dregs of society’. By inference the author is suggesting that both the high-level Communist cadres purged in the targeted anti-corruption regime of Xi Jinping-Wang Qishan initiated in 2013, and the performance artists — such as the life-style guru Wang Lin, and other unnamed celebrities in the entertainment industry — share not only a benighted fate (that of 落馬 luòmǎ — being ‘thrown by a horse’ or ‘bucked out of their saddles’; actually they were dragged from their saddles), but perhaps also their roles are not that dissimilar. As Shakespeare famously puts it in As You Like It (Act II, Scene VII):

All the world’s a stage,

And all the men and women merely players;

They have their exits and their entrances.

Or, again, as the great Chinese novelist Cao Xueqin 曹雪芹 writes:

陋室空堂,當年笏滿床;

衰草枯楊,曾為歌舞場;

蛛絲兒結滿雕梁,

綠紗今又在蓬窗上。

亂烘烘你方唱罷我登場。

Mean hovels and abandoned halls

Where courtiers once paid daily calls:

Bleak haunts where weeds and willows scarcely thrive

Were once with mirth and revelry alive.

While cobwebs shroud the mansion’s gilded beams,

The cottage casement with choice muslin gleams….

In such commotion does the world’s theatre rage:

As each one leaves, another takes the stage.

—《石頭記》好了歌 註

from The Story of the Stone

trans. David Hawkes

(For more on theatrical metaphors and Chinese politics, see the section ‘Show and Tell: Palliative Resistance’ in Homo Xinensis Militant, China Heritage, 1 October 2018)

That material — an admixture of fact and fabrication — crowds the online world, yet it offers the devoted reader enough real information to piece together the historical truth. More significantly, all the links — regardless of whether they lead to denunciations or approbation — provide from various angles a vivid picture of that vicious era, along with details of the corruption of the soul of China and the crimes of the system itself. And there it is — all that information that is constantly reminding hundreds of millions of interested readers of the absurdity and pitilessness of history. More importantly, this plethora of material provides evidence enough, albeit in dribs and drabs, to constitute a flood of awareness that may provide people with the mental and spiritual wherewithal to resist anything like that happening again. Not only could it inoculate people so that they are alert to resisting autocracy, but also so that they may guard against and resist all autocratic behaviour [including the kind authored by the ‘Newly Ennobled One’, mentioned above].

它們林林總總,虛虛實實,多少給予讀者拼聯歷史真相的機會。更為重要的是,這些有關他們的詞條內容,從不同視角,討伐抑或崇仰,展示了酷烈時代的靈魂扭曲和體制罪惡,等於在向億萬讀者時時提示歷史的吊詭與無情,從而也就是在為避免悲劇重演,於涓滴匯流中積攢抵抗的精神資源。不只是抵抗某一種專斷,而是對於一切專斷的提防與抵抗。

Lingering at the crossroads of past and present the solitary individual may awaken to the fact that one can find commune in shared public rationality, and shine thereby a light on our shared humanity, in particular providing a better understanding both of the fragility as well as of the dark recesses of the human heart. It is this that better allows us to protect and maintain the domain of our own humanity, something that pulses in us with every breath and which is our constant reality. Moreover, this shared rationality is not merely of benefit to readers of Chinese, it has universal validity. Foremost, however, it must nourish the global realm of Chinese. This should be self-evident and go without saying: there should be room for such views as mine; it is well known, flowing waters do not stagnate; My Nation My People: herein lies the possibility for a true revival.

今昔流連之際,孤單的個體理性方始可能串聯並合成公共理性,於燭照人性中遵守常識,特別是明瞭人性的脆弱與幽暗,而護持我們生息其間、須臾不可離易的人世家園。而且,此非僅只惠及漢語讀者,而實具普世意義,但首先沾溉漢語世界,自是不言自明,則網開一面,流水不腐,吾族吾民,生機活現也。

須臾不可離易 xūyú bù kě lí yì: in writing about the innate value of humanity, the ‘garden of human existence’ 人世家園, the author employs a slightly altered version of a well-known line from the opening of The Middle Way or Golden Mean 中庸, one of the ‘Four Books’ of the Confucian classics:

The Way may not be departed from even for an instant. If it could be abandoned so easily, it would not be the path. 道也者,不可須臾離也,可離非道也。

普世意義 pǔshì yìyì: ‘universal validity’ or general applicability, by inference the author is referring to the ongoing clash between the Communist Party’s invented of Core Socialist (and supposedly uniquely Chinese) Values versus the Universal Values 普世價值 of Western liberal democracies, which the Communists condemn as unsuited to China and its peoples. (For more on this, see Homo Xinensis, China Heritage, 31 August 2018)

網開一面 wǎng kāi yī miàn: literally, allow an opening in a net set to capture something/ someone a way to escape/ survive. This is used to mean ‘allow for some leeway’ or ‘show some reasonable compassion’. This expression, like so many employed by the author, also comes from Sima Qian’s Records of the Grand Historian 史記. The account of the rulers of the Yin-Shang dynasty 史記 · 殷本紀 includes a story about the ruler Tang on his travels saw nets set up on all four sides to capture animals. He ordered that one side be left open so some creatures could escape; anyway, he reasoned, all living things were ensnared in the net of his own rulership (the text reads: 湯出,見野張網四面,祝曰:自天下四方,皆入吾網。湯曰:嘻,盡之矣。乃去其三面。祝曰:欲左,左;欲右,右。不用命,乃入吾網。)

吾族吾民 wúzú wúmín: there are various similar formulations such as 吾國吾民 and 吾土吾民. The most famous of these is 吾國與吾民, the Chinese translation of My Country and My People (1935), a popular book about China’s plight by the essayist, translator and humourist, Lin Yutang (林語堂, 1895-1976)

生機活現 shēngjī huóxiàn: ‘living evidence of true [national] vitality’. This passage celebrates the humanist spirit, its universal validity and its importance for contemporary China. This generous view is in stark contrast to the party-state’s pinched nationalism

In the online links related to the ‘Gang of Four’, there is much repetition of the Communist appraisal of these people, including the clichéd formulations that their actions amounted to nothing less than a ‘Catastrophe for the Nation and a Disaster for the People’, and that their crimes were so numerous that they were ‘beyond number and ability to record’. Reading this brought to mind those days of trembling fear in my youth [the author was born on 1962, and was therefore in his teens during the last years of Mao and the ‘Gang of Four’], as well as the breathless wonder of countless masses who watched the Show Trial of the Four, anguish and amusement commingling. Even more does one treasure the breathing space now in which no longer is there an endless succession of escalating of campaigns related to class struggle.

其中關於「四人幫」的一個詞條,重述當年中共的表述,指斥其犯行「禍國殃民」,而罪惡「罄竹難書」,令我不禁回想起少年時代的觳觫歲月,以及後來審判大戲登場時的萬眾屏息,悲喜交加,更加珍惜此刻這個不搞「一浪高過一浪」階級鬥爭運動的喘息時光。

禍國殃民 huò guó yāng mín: literally, A Catastrophe for the Nation and a Disaster for the People. Following the announcement of the arrest of the ‘Gang of Four’, usually described as being a ‘smashing’ 粉碎, a series of approved terms of denunciation of the so-called counter-revolutionary plotters — Wang Hongwen, Zhang Chunqiao, Jiang Qing and Yao Wenyuan — was used constantly to describe them (the four prominent party-state leaders were, in fact, ousted in a military coup by a junta directed by Marshall Ye Jianying and fronted by the recently installed Party chairman Hua Guofeng). One of the most common propaganda expressions was ‘The Gang of Four Catastrophe for the Nation and Disaster for the People’ 禍國殃民的四人幫 and they were shrilly denounced collectively for having ‘imposed a political line of national destruction, an extreme-rightist line that would result in the fall from power of the Communist Party and the collapse of the nation 他們推行的是一條禍國殃民的路線,亡黨亡國的路線,是一條極右的路線, etcetera. We would note that the expression 禍國殃民 huò guó yāng mín was initially popularised by none other than the fifth member of the ‘Gang of Four’, Mao Zedong. In a famous speech titled ‘Oppose Stereotyped Party Writing’ 反對黨八股 made at the start of the Yan’an Rectification Campaign in 1942, Mao listed eight indictments against ossified Party prose, the eighth of which was that such clunky writing ‘would wreck the country and ruin the people’ 禍國殃民

罄竹難書 qìng zhú nán shū: another traditional expression used to condemn crime and evil. Dating from the Warring States period when bamboo strips were used to preserve written texts, it literally means: ‘even if all the bamboo was used up, it would be impossible to record [all of the crimes]’ of so-and-so. From 1976, this hackneyed expression was employed to exaggerate the crimes of the ‘Gang of Four’. In reality, the Politburo of the Communist Party supported the build up to the Cultural Revolution from the Socialist Education Campaign of 1964, and voted in favour of key decisions regarding the nationwide purge starting in mid 1966. The ‘crimes beyond calculation’ indicated by such terms as 罄竹難書 qìng zhú nán shū involved far more than the ‘Gang of Four’, for they include Mao Zedong himself and many other party-state leaders such as Zhou Enlai, an early and enthusiastic supporter of the Cultural Revolution, Jiang Qing, and Lin Biao

觳觫歲月 húsù suìyuè: literally, ’a time of trembling fear’. The author, born in 1962, was four years old when the Cultural Revolution was formally launched in 1966 and fourteen when Mao died. He was eighteen years old when the Show Trial of the ‘Gang of Four’ was staged in 1980-1981. The expression 觳觫 húsù, ‘shaking with foreboding’, appears notably in Mencius, the canonical Confucian text quoted earlier, where it is used to describe the demeanor of an ox being led off to the slaughter as part of a religious ceremony. 觳觫 húsù would later describe the terror of people facing execution. In the account of Mencius’s dialogues with King Hui of the Kingdom of Liang 梁惠王 it is recorded that:

I heard the following incident from Hu He: ‘The king,’ said he, ‘was sitting aloft in the hall, when a man appeared, leading an ox past the lower part of it. The king saw him, and asked, ‘Where is the ox going?’ The man replied, ‘We are going to consecrate a bell with its blood.’ The king said, ‘Let it go. I cannot bear its frightened appearance, as if it were an innocent person going to the place of death.’ The man answered, ‘Shall we then omit the consecration of the bell?’ The king said, ‘How can that be omitted? Change it for a sheep.’ I do not know whether this incident really occurred.

曰:臣聞之胡齕曰,王坐於堂上,有牽牛而過堂下者,王見之,曰:牛何之。對曰:將以釁鐘。王曰:舍之。吾不忍其觳觫,若無罪而就死地。對曰:然則廢釁鐘與。曰:何可廢也。以羊易之。不識有諸。

They were ‘A National Catastrophe and a Disaster for the People’, moreover, their crimes are beyond calculation and could fill libraries. Nonetheless, there are tens of thousands of Baidu entries on their lives and detailing their actions, and in some cases links to their writings [in particular those of Zhang Chunqiao and Yao Wenyuan] are available. For this worthless scholar, one who has laboured for over three decades to earn a modest living, a person who is ‘on the frontline struggle of the classroom’, no matter how much of a catastrophe I might threaten to create, it will never be on a national scale, and regardless of the disaster that I may present, at most it will corrupt but a few students. Why, therefore, have I been stricken from the Internet? Or, should I ask: do you honestly believe you can simply make me evaporate and disappear entirely from the ranks of humanity?

他們「禍國殃民」,進至於「罄竹難書」,尚有數萬詞條展示其生平,羅列其行止,甚至刊布其作品。在下一介教書匠,三十多年里,但求溫飽,「奮戰在教學第一線」,若禍則禍不及於國,要殃也只能殃及三、五學子,何至於將我從網上抹掉,或者,似乎認為如此這般就能將我從人間蒸發。

一介 yī jiè: a literary term meaning ‘one’, generally equivalent to 一個, but with a slightly self-deprecating or diminutive connotation. Here, in keeping with his sardonic style, the author is assuming mock humility

教書匠 jiāo shū jiàng: another term of bemused self-abasement. The author calls himself a mere ‘artisan’ or ‘craftsman’ 匠 jiàng engaged in teaching 教書 jiāo shū. Traditionally, ‘teaching tradespeople’ indicated failed examination candidates who made a living by teaching pupils in private schools 私塾

蒸發 zhēngfā: literally ‘to evaporate’; it is used in such terms as 人間蒸發 and 蒸發人間, that is ‘people who have vanished into thin air’, or those who have been ‘disappeared’. In contemporary usage, it is also similar to the English term ‘ghosting’, meaning to end a relationship without any explanation

The only explanation I can think of is that a low-level tradesman in pedagogy like me — one who has no taste for street fighting and with no training in the use of any weapons — is actually regarded as being worst that the ‘National Catastrophe and Disaster for the People’ that was the ‘Gang of Four’.

唯一的解釋是,我這個底層教書匠,不嗜打架,也不會任何一件兵器,竟然比「禍國殃民」的「四人幫」還壞。

Secretaries draft the speeches that the bureaucrats read out. There’s one joke that goes:

A sentence at the bottom of the printed page of speech drafted by a functionary ends with a rhetorical question, but the particle word and question mark at the end of the sentence — 麼? [which turns the proceeding statement into a rhetorical question] — happened to be printed on the top of the following page. The bureaucrat making the speech mindlessly recites down to what he believes is the end of the speech, concluding with the bottom of the page. Then, looking up at an expectant audience, he pauses for a moment, and only then turns over the page. Upon discovering the missing word he reads it out with redoubled gusto. The actual effect was the equivalent of ‘Zhou Yongkang (although the name could be that of any equivalent character, such as Wu Yongkang, Zheng Yongkang, Wang Yongkang, or even Sima Yongkang) is not evil ﹫#$%& …… is an incorrect statement!’

Extrapolating from this one can come up with other examples, such as: ‘I am more evil than the “Gang of Four” ﹫#$%&…… is an incorrect statement!’ or ‘You people are competing in the stakes of evil with the “Gang of Four” ﹫#$%&…… is an incorrect statement!’

秘書寫稿子,官員念稿子。有一個笑話說的是,講話稿的頁末一句是個疑問句,因排版原因,語助詞連同疑問號「麼?」印在了下一頁。官員念完這句,環視台下,少頃,莊重翻頁,再補充上語助詞,音調鏗鏘,致使現場效果成了「周永康/吳永康/鄭永康/王永康/司馬永康不是一個壞人﹫#$%&……麼?」轉借此例,在下接續而來的造句作業是:「我比’四人幫’還壞﹫#$%&……麼?」抑或,「你們要和‘四人幫’比壞﹫#$%&……麼?」

周永康/ 吳永康/ 鄭永康/ 王永康/ 司馬永康, that is: Zhou Yongkang/ Wu Yongkang/ Zheng Yongkang/ Wang Yongkang/ Sima Yongkang: this is sarcastic reference to a well-known informal Communist Party formulation about traitors and turncoats in its ranks. A familiar example is that of Lin Biao, the hand-picked successor to the Great Helmsman Mao himself. After Lin’s mysterious death in September 1971, many Party stalwarts would respond to querulous interrogations that the immutable laws of materialist dialectics predicted that the appearance of such political scum was inevitable: if there hadn’t been a Lin Biao, there would have been a Zhang Biao, Chen Biao or Liu Biao.

As a ‘fresh-off-the-boat’ twenty-year-old student, I was given just this explanation by Teacher Bi 畢老師, our ‘ideological guidance counsellor’ at the Beijing Foreign Languages Institute, in November 1974. Teacher Bi patiently explained to me that treacherous individuals like Lin Biao had only revealed their true nefarious character over time and, although Chairman Mao was quite literally ‘all seeing’ 洞察一切, in his wisdom he decided that it was best to let things take their course before acting against the traitor. Daresay, a similar argument has been made in regard to Xi Jinping’s egregious failure over many years to confront the unbridled corruption of Zhou Yongkang, Xu Caihou and many others who have now been condemned

In a season of discontent and buffeted by winds from all directions, silence now reigns in our realm. What remains is acquiescence of the multitude, such arrant stupidity and, grotesque folly. But as for my part, as a lowly pedagogue, and as Mr Hu Shi remarked over eighty years ago: ‘And teachers, then? They just do their thing!’ [that is, teachers speak out, and they’ll just keep on doing so]. But when speaking out one must make oneself heard, for only then can there be some kind of dialogue or exchange. Only then can we break free of the solitude of self and enjoy the realities of community, and thereby affirm our humanity. Moreover, our shared community, only through shared community, can we enjoy freedom. It is for this reason that Baidu’s effacement results in a sense of impotent resignation for we have no choice but to rely on the services of Baidu, this Leviathan. So how can one overlook such blanket obliteration?! How can one help from taking it personally?! To do otherwise, would require one to blind one’s eyes and dull one’s mind. Over time, [as a result of the media being stymied like this] the nation may will find itself reduced to the mindless state of swine.

只是值此八面來風時節,欲令天下無聲,惟剩諾諾,何其愚妄,何其滑稽。畢竟,身役教書匠,如八十多年前適之先生所言:「哪有先生不說話?!」而說話就得讓人聽見,才能構成對話與交談,讓我們擺脫孤立的私性狀態,獲得公共存在,保持人性。進而,我們的公共存在狀態,也唯有這種公共存在狀態,才賦予我們以自由。職是之故,對於百度的封殺,對於造成我們無奈只能用百度而無所選擇的那個巨靈,豈能不留意?!又豈能不往心裡去?!否則,閉目塞聰,一個民族可能慢慢會變成一頭豬。

八面來風時節 bā miàn lái fēng shíjié: literally, ‘in this season as the Eight Winds are blowing on all sides’. Here this means ‘at a time when unsettling news is accosting [us/ you/ China] form all directions’, that is, economically, at home and internationally. For details concerning the ‘Eight Winds’ 八風, see here; and for a discussion of ‘wind’ 風 in the context of contemporary Chinese politics and writing, see Mendacious, Hyperbolic & Fatuous — an ill wind from People’s Daily, China Heritage, 10 July 2018

天下 tiānxià: ‘All-Under-Heaven’, ‘realm’, ‘China’, ’empire’, ‘the civilised world’. For an extended essay on this word in the context of the modern Chinese party-state, see The Party Empire, China Heritage, 17 August 2018. Hero 英雄 (2002), a globally successful film directed by Zhang Yimou 張藝謀, China’s audio-visual ‘imagineer-in-chief’, ends with the death of the failed assassin Nameless 無名, the revelation that the ruler is, in fact, the First Emperor of the Qin, and a one-word panegyric for his immortal achievement: 天下 tiānxià. In translated the subtitled version of the film this is translated as ‘Our Land’, an act of elision that glossed over the well-known history of the realm of the Qin Empire, one created and maintained by pitiless warfare, relentless violence and ceaseless repression

無聲 wúshēng: as noted in the Introduction, this expression means ‘silence’ or ‘voiceless’. The writer Lu Xun helped to popularise it in an era of protest and repression when he spoke of ‘voiceless China’ 無聲的中國 and his hope that in the future the young would speak up (see Silent China & Its Enemies, China Heritage, 13 July 2018). Even Deng Xiaoping, who was no friend of free speech, famously used the expression ‘silence’ 無聲 in his closing remarks at a work meeting of the Communist Central Committee held in December 1978:

The worst thing for a revolutionary political party is to fail to listen to the people; it’s deeply worrying if there is nothing but silence [literally, if even the magpies and sparrows are quiet]. 一個革命政黨,就怕聽不到人民的聲音,最可怕的是鴉雀無聲。

Given Deng’s crucial role in the suppression of intellectual and academic freedom in the 1957 purge of ‘Rightists’, this was a hard-won realisation. However, it was soon followed by the silencing of a new generation of outspoken men and women; they were deemed the wrong kind of ‘people’. Most famous of their number was Wei Jingsheng (魏京生, 1950-), who was arrested in March 1979 after having published in samizdat form a pointed essay about Deng and the Party titled ‘Democracy or Renewed Dictatorship?’ 要民主還是要新的獨裁. The silencing of the voices of men and women of conscience in China’s People’s Republic has continued in waves of varying intensity and unpredictable frequency ever since. Another common expression for this in the written language is 噤聲 jìn shēng, literally ‘silencing voices’.

We would note that, shortly after Xu Zhangrun wrote this essay, and only days before it appeared on the Unirule Institute website, Sheng Hong 盛洪, the executive director of the Unirule Institute of Economics, as well Jiang Hao 蔣豪 of the same institute, were officially barred from attending a conference at Harvard University being held to commemorate and discuss China’s four decades of Reform. Sheng was reportedly told that his presence at Harvard would ‘endanger national security‘. In an interview granted to Radio Free Asia in mid July 2018, Sheng had remarked:

In a society that has one voice we offer a second voice. It’s better two have two voices than only one. Shouldn’t things be seen from more than just one angle? … During the present Trade War with the United States we have expressed our view that, in reality, as long as China perseveres with Reform and the Open Door policies, continues to support the principles of free trade and market economics, there will be no clash with the US.

假如一個社會只有一種聲音,那麼我們就是第二種聲音,有兩種聲音就比只有一種聲音好。我們是否應該有多一個角度看問題?… 這次的貿易戰我們也提出我們的看法:實際上,中國堅持改革開放,堅持自由貿易和市場經濟原則,我們和美國沒有什麼衝突。

諾諾 nuònuò: to be obsequious, compliant or fawning. The expression has two famous uses in relation to pre-Qin historical figures:

1. As noted in the Introduction, in Sima Qian’s ‘Biography of Lord Shang’ 史記 · 商君列傳第八 it says:

The refusal of one decent man outweighs the acquiescence of the multitude

千人之諾諾,不如一士之諤諤。(Also used by Simon Leys as the untranslated epigraph in The Chairman’s New Clothes, his 1971 exposé of the Cultural Revolution. See One Decent Man, The New York Review of Books, 28 June 2018, vol.64, no.11)(The context is: 趙良曰: 千羊之皮, 不如一狐之腋; 千人之諾諾, 不如一士之諤諤。武王諤諤以昌,殷紂墨墨以亡。); and,

2. Han Fei 韩非, one of the thinkers behind the Qin autocracy, warned against sycophants:

A person who is already offering obedience before an order is given;

Some one who utters their compliance before a task is assigned.

Constantly examining their master’s countenance to gauge their wishes.

此人主未命而唯唯,未使而諾諾,先意承旨,觀貌察色以先主心者也。— from ‘Eight Kinds of Treachery’ in Hanfeizi 韓非子 · 八奸

This is the origin of the common modern expression 唯唯諾諾 wěiwěi nuònuò, ‘servile compliance’

適之先生 Shìzhī xiānshēng: ‘Mr Shizhi’, Shizhi was the main ‘courtesy name’, or style zì 字, used by Hu Shi (胡適, 1891-1962) when writing. 先生 xiānshēng, literally ‘one born before’, or elder — a term of respect. Although now commonly used like Mister/ Mr in English, 先生 xiānshēng retains the older meaning of ‘teacher’ or ‘master’

巨靈 jù líng: literally, ‘Giant Spirit’ or ‘Monstrous Force’, is a reference to Thomas Hobbes’s Leviathan. In the frontispiece to this work, Hobbes quotes the ‘Book of Job’: ‘Non est potestas Super Terram quae Comparetur ei. Iob. 41 . 24’ — There is no power on earth to be compared to him

閉目塞聰 bì mù sāi cōng: in ‘On Practice’ 實踐論 (1937), a fundamental Chinese Marxist-Leninist theoretical tract, Mao Zedong used a variation of this expression — 閉目塞聽 bì mù sāi tīng — when he wrote: ‘For a person who shuts his eyes, stops his ears and totally cuts himself off from the objective world there can be no such thing as knowledge.’ 一個閉目塞聽、同客觀世界根本絕緣的人, 是無所謂認識的

變成一頭豬 biànchéng yītóu zhū: here the author seems to be recalling the statement, ‘Let me control the media and I will turn any nation into a herd of swine’, made by Joseph Goebbels, head of the Nazi Reichsministerium für Volksaufklärung und Propaganda, or Reich Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda (1933-1945)

And, it is for this reason that I now address you directly — that’s right, those of you who play the handmaidens to tyrants and help the devil do his handiwork — I say to you, including those who don’t mind getting their hands dirty by deleting and blocking online information, and especially those of Black Hearts who formulate such policies and issue instructions: I harbour no hatred for you; for all of you all I have nothing but sympathy. And let me add, you are still young and daresay possessed of a measure of talent; why not try finding a decent profession so you can make an honest living?

因而,我對你們,助紂為虐,為虎作倀,包括不嫌手臟而下手刪除、屏蔽信息的,特別是不怕心黑做出類此決策下達指令的,並無仇恨,只有滿腔的同情!再說了,年紀輕輕,身懷長技,為何不另找一個乾淨營生?

Here, when the author directly addresses the Internet Invigilators, one is reminded of the novelist and essayist Murong Xuecun’s 慕容雪村 Open Letter to a Nameless Censor, 20 May 2013

助紂為虐 zhù Zhòu wéi nüè: a common expression used to condemn those who aid and abet evil-doers. It takes on a particular significance here the author is addressing those complicit in the exacerbated repression of online expression under Xi Jinping. Given the present state of academic and intellectual freedom in China today, by employing this otherwise cliched four-character term, the author casts the Supreme Leader as the infamous Tyrant Zhou 紂, or King Zhou 紂王. Zhou, synonymous with tyranny, is the pejorative name of Di Xin 帝辛, the last ruler of the Shang, and one that was imposed on him posthumously by his victorious enemies.

Again, we return to the Qin dictatorship. After the short-lived Qin was overthrown by an army under Xiang Yu 項羽, Hegemon of Chu 楚霸王, its capital was reduced to ashes. During the ensuing struggle for hegemony, Xiang Yu clashed with Liu Bang 劉邦, the King of Han 漢王. At one point, Liu’s army occupied Xiang Yu’s own capital city and Liu was soon indulging himself in the luxuries of its palace, as well as the pleasures of the flesh provided by Xiang Yu’s harem. Liu’s advisers cautioned him against indulging in such sybaritic behaviour since, in essence, it demonstrated that he had helped oust an old tyranny (that of the First Emperor of Qin) only to replace it with another, his own. His advisers said that he was 助紂為虐 zhù Zhòu wéi nüè, ‘helping the tyrant to continue his misrule’. These details are recorded in Sima Qian’s Records of the Grand Historian. It will come as no surprise that Mao Zedong commented positively on the achievements of the Tyrant Zhou, in particular because he crushed all opposition to his reign and expand his territory.

為虎作倀 wèi hǔ zuò chāng: this too is a common clichéd expression used to decry those who help evil people pursue their dastardly plots. It was believed that a person killed by a tiger would become an evil spirit, or 倀鬼, one that would then go on to help the tiger harm others. It is similar to 為虎添翼, ‘giving a tiger wings with which to fly [and cause even greater mayhem]’

無仇恨 wú chóuhèn: ‘I harbour no hatred for you’. This immediately brings to mind the dissent Liu Xiaobo’s final statement at his 2010 trial in which he said: ‘I have no enemies; I harbour no hatred’ 我沒有敵人, 也沒有仇恨

We are all living in bleak darkness; there is no dim light of dawn ahead. We can but extend a hand of sympathy [to each other] and then, hand in hand, we may advance through all treacherous barriers to achieve release.