Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium

Appendix LVII

傷感

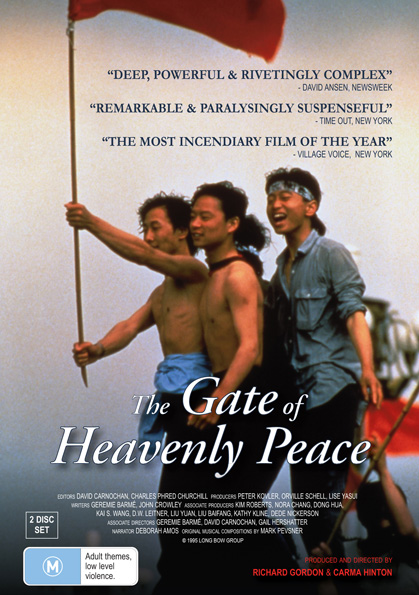

The Village Voice published ‘Anatomy of a Massacre’, a review-essay of the documentary film The Gate of Heavenly Peace by Richard B. Woodward on 4 June 1996. The film, directed by Carma Hinton and Richard Gordon, was produced by the Long Bow Group in Boston, where I worked both on that project, as well as on Morning Sun. Our lives at Long Bow were immeasurably enhanced by the presence of Nora Chang (張仲琪, 15 November 1962-1 November 2023).

As the year 2023 draws to an end, we remember with great fondness our dear friend Nora. She was one of the directors and producers of the film making group, as well as being the steady hand that managed our sprawling operation. She was an indefatigable colleague. Her quiet efficiency, wry humour and unfailing friendship also contributed in a myriad of ways to the unique atmosphere of Long Bow, something captured in Rick Woodward’s essay below.

Richard Woodward (1953-2023), a noted essayist and writer, also passed away this year and we miss him. We feel no sympathy, however, for Ted (‘The Unabomber’) Kaczynski, who died on 10 June 2023. He enjoys a cameo appearance below only because of his notorious typewriter.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

26 December 2023

毛誕

***

Related Material:

- On the Eve — China Symposium ’89

- Additional Readings and Links, The Gate of Heavenly Peace website

Also in Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium:

- Chapter Twenty-two 官逼民反 — Fear, Fury & Protest — three years of viral alarm, 27 November 2022 (see also Appendix XXIII 空白 — How to Read a Blank Sheet of Paper, 30 November 2022; Appendix XXIV 職責— It’s My Duty, 1 December 2022; and, Appendix XXV 贖 — ‘Ironic Points of Light’ — acts of redemption on the blank pages of history, 4 December 2022; and the Supplement, ‘It’s only the end of the beginning’ — Teacher Li on Blank Pages, Li Keqiang, Snowflakes & Monsters, 18 December 2023)

- Chapter Twenty-seven 虛船觸舟 — Li Keqiang, the ‘Empty Boat’ of the Xi Jinping Era, 14 November 2023 (see also Monster Mash — Mourning a Dead Premier & Mocking the Ghouls Among the Living, 4 November 2023)

- Appendix XLIX 陰魂不散 — Shades of Mao — Children Spying on Parents, Fragile Hearts in Patriotic Drag and the Fishwife who Trolled Ukraine, 9 September 2023; and, Xi at XI — More Mao Than Ever, 23 December 2023 (a supplement)

- Appendix LV 一週年 — What Scares Me — a letter from Kathy on the first anniversary of the Blank Page Movement, 4 December 2023

***

In memory of Nora Chang

Hurt Feelings

“We have news,” says Richard Gordon, bounding down the stairs and handing me the latest “review.” …

The “review” comes from the Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in Washington, D.C., the first time the government has dared put its views on paper. Composed on what one of the film’s writers, Geremie Barmé, calls “a really bad typewriter, a Unabomber typewriter” and sent to the director of the Washington international Film Festival, the letter urges removing the offensive work from their April schedule.

“As is well-known, a very small number of people engaged themselves in anti-government violence in Beijing in June 1989 but failed,” writes an embassy press officer. “The film the Gate of Heavenly Peace [sic] sings praise of the people in total disregard of the fact. If this film is shown during the festival, it will mislead the audience and hurt the feelings of 1.2 billion Chinese people.”

Everyone in the house is delighted to have a smoking gun, especially Barmé. An erudite Australian academic with a reputation for seditious mischief (and arrogance) in his field of contemporary Chinese studies, he had flown to “Gulag Long Bow” to help with the Web page, which includes an interactive Tiananmen. (Click on Mao’s mausoleum on the Square and learn of its elevator, which takes the corpse up and down every day from the hall into an earthquake-proof chamber. Or stroll the Square as a “normal” or a “revolutionary” tourist.) Gordon’s job among the film’s opinionated collaborators was to speak up for “Joe Blow,” the viewer who wouldn’t know the many players or the subtle codes in which they speak; Barmé admits he “doesn’t give a fuck about Joe Blow.” Scornful of those who have credulously accepted Chai Ling’s and Li Lu’s version of events and embraced them as innocent martyrs, he wanted to call the film “Merchandising the Massacre.”

He fires off Long Bow’s reply: “Whereas we are heartened by any efforts of the diplomatic corps to engage in amateur film criticism and historiography, we feel that it is important that their naive enthusiasm not cloud the serious issues on which they choose to comment.” Bewildered by this “handful of people,” he cites the Beijing Evening News, which reported on August 3, 1989, that it took 156,000 people to wash away the 30,000 slogans and pick up the 80 tons of bricks after the disturbance. Then he e-mails both letters to friends in Australia where that night the futile effort to ban the film is a story again. CNN and the Washington Post also pick it up. Against an opponent that relies on such crude tools to stanch the flow of unwelcome information, the filmmakers have the Western media, as well as a better grasp of the truth, on their side. It almost isn’t a fair fight.

***

***

Anatomy of a Massacre

Richard B. Woodward

The Village Voice, 4 June 1996

Long before a frame of it was fed through a projector, “The Gate of Heavenly Peace” had incited the kind of publicity that money can’t buy. There was buzz, and the buzz was angry, ugly, personal. Rumors in the dissident Chinese press of what might be distorted (or revealed) about certain individuals involved in the bloody rebellion at Tiananmen Square in 1989 were enough to generate a stack of irate reviews.

Patrick Tyler put an innocent stick in this nest with a piece in The New York Times on April 30, 1995. After seeing a rough cut, he reported on the documentary’s upcoming release and its mildly revisionist views on the tactics and heroism of some of the students. On May 28th, an article in the South China Morning Post appeared about “possible legal action” against the film from Chai Ling and Li Lu, two of the most visible students who had escaped from China to the U.S. And by June, several veterans of ’89 had issued summary verdicts in the Chinese dissident magazine Tiananmen , certain they needn’t view the film to condemn it (and Tyler).

“They [the producing and directing team of Carma Hinton and Richard Gordon] are a bunch of opportunists,” wrote Bai Meng, who had manned the public address system in the Square. “As long as they call themselves intellectuals, their flagrant distortion of history is a criminal act… They are a bunch of flies. They are the true disease of our era.”

The Chinese government didn’t see the film either. But they did their bit to promote it, too, barring director Zhang Yimou from leaving China for the American premiere of his “Shanghai Triad” last September at the New York Film Festival because “The Gate of Heavenly Peace” was also scheduled. The NYFF refused to pull the film and screened it publicly for the first time anywhere on October 14. But at nearly every festival where the film was submitted, China seems to have strong-armed organizers to suppress it. The head of the Berlin Film Festival, after calling Hinton and Gordon to rhapsodize about the film, comparing it favorably to “The Sorrow and the Pity,” abruptly turned it down after the fuss in New York.

All of this furor should have been good for business. Using the NYFF showdown as a peg, Time and Newsweek wrote stories and praised the film’s evenhandedness. And were it a feature about religion or sex, maybe it could have been sold as a juicy scandal like “Hail Mary” or “Basic Instinct.”

Too bad “The Gate of Heavenly Peace” is only a profound meditation on revolutionary politics that indirectly delivers a withering critique of the ability of American news networks to interpret a complex, developing story far beyond its borders. Edited to a large degree from TV coverage of the Tiananmen Massacre, the film likely won’t have the theatrical showing it deserves. The exorbitant cost of licensing this footage from the networks (and the prior release of the ludicrous “Moving the Mountain,” which covers some of the same ground) means that “one of the great documentaries of the last 20 years” (so sayeth Charles Taylor in The Boston Phoenix ) [Gate of Heaven, The Boston Phoenix, Jan. 5, 1996] will be restricted to not-for-profit venues.

The rockets of invective aimed at “The Gate of Heavenly Peace” from across the Pacific and from there in the U.S. may puzzle some who tune in next Tuesday for the PBS broadcast, an abridged two-and-a-half hour version of the three-hour original. The style of the film certainly can’t be called provocative. There is no hokey reenacting or Oliver Stone-like monkey business with recorded history.

The cinema of Hinton and Gordon has always been reserved and conservative, more steak than sizzle. Their series of award-winning documentaries shed light on daily life in a Chinese village without pyrotechnics. Notwithstanding its monumental scale, cast of millions, and attempt to condense 70 years of Chinese revolutionary politics, this latest effort doesn’t draw attention to itself either.

A sober analysis of the heady Beijing spring of ’89, when seven weeks of peaceful protest were crushed by the tanks of the People’s Liberation Army, “The Gate of Heavenly Peace” is a painstaking, almost day-by-day reconstruction of the April 15-June 4 events in and around Tiananmen, as shaped by the actions and words of students, workers, intellectuals, and government officials, many of them playing to the cameras, and as these events are now recalled by as many principals as could be rounded up. Although in many ways about the lingering power of images and ideology, the film is dominated by its reflective, articulate talking heads, whose words are translated in English voiceover. The grave narration by ABC news correspondent Deborah Amos serves as a guide through the ruins for foreigners, but nearly everyone else on the soundtrack speaks – or sings – in Chinese.

And yet despite its unflamboyant manner, this may well be the most incendiary film of the year. From the editorial pages of the Washington Post and L.A. Times to journals out of Hong Kong, Taiwan, the U.S., and China, the film has been argued over, denounced, and extolled, as often as not by those who haven’t seen it. Even the human rights community was at one point up in arms. After Tyler’s article, Robert Bernstein, the chairman of Human Rights Watch, tried to bully the filmmakers into interviewing one of his favorite dissidents, Li Lu. The debate has even reached into the status of intellectual cliché, spilling into the letters pages of the New York Review of Books , where Hinton and Gordon mixed it up with Ian Buruma. [Both the directors’ letter and Ian Buruma’s reply are available on the Long Bow website.]

Now that the revolution will be televised, many more can take sides and at least know what they’re talking about. As a bonus, to coincide with the June 4 broadcast on the seventh anniversary of the troops’ retaking of Tiananmen, America On-Line has declared the documentary’s address (WGBH.org/frontline) its Website of the day. Those with a hearty appetite for the topic can download nearly a thousand pages of documents plus film and audio clips amassed while researching the film, an encyclopedia on the spring of ’89.

It takes a special gift to piss off the Chinese government and many of their sworn ideological foes among the leaders of the rebellion and pillars of the American human rights establishment and your own father. But it’s a role that Carma Hinton was born to play. Born and raised in China, a teenager during the Cultural Revolution, she is the daughter of William Hinton, author of the classic agrarian study, Fanshen, who still deeply admires Mao and Zhou Enlai. This association has given some students all they need to discredit the film. Bai Meng dismissed Carma Hinton as “an American who grew up in China like a privileged aristocrat and maintains deep ties at the highest levels of the Chinese Communist Party.” No doubt surprising news to Deng Xiaoping, and Li Peng, and the filmmakers themselves.

“The Gate of Heavenly Peace” is anything but Hinton’s psychodrama, however, or an academic exercise. As China has vaulted over the dismantled Soviet Union to assume its place as the chief foreign policy concern of the U.S., the question of what happened at Tiananmen, and why, is vital for dealing with the sclerotic leadership still in charge.

“The whole Democracy Movement is the key to understanding China today,” says Xiao Qiang, New York director of Human Rights in China. “The government showed they have no legitimacy except brute force. Everything they do now is designed to reestablish legitimacy. They can’t have open discussion of the events. That would lead people to ask who was responsible for the massacre and that would lead to the collapse of the Communist Party.”

The reaction to the film among some who bravely opposed the government, however, leads one to wonder if they are any more ready to engage in critical debate. Was reform achievable in ’89 until it was derailed by a radical faction? Or, as Buruma suggests, is reform of a totalitarian regime an oxymoronic fantasy? Did Chai Ling, the young woman on every TV station during and after Tiananmen, break faith and encourage the bloodbath? Or is it unfair to question the motives and tactics of Antigone when the state looms as the obvious oppressor?

Not the least remarkable aspect of “The Gate of Heavenly Peace”, which in historical sweep and nuance does bear comparison to “The Sorrow and the Pity,” is its examination of this worldwide media event as a drama of tragic dimensions. The film argues that ’89 must be seen in the context of Chinese history, a history that many Americans mistook as a mirror of their own.

Yet at the same time anyone with scars from mass protest – whether antiwar, civil rights, SDS, prochoice, prolife, ACT UP, or Solidarity – will feel the shock of recognition. All activists have to calculate: Do we keep pushing for change and risk a violent backlash? Or should we settle for incremental gains that may prove to be a sham? The Chinese students miscalculated, and at least 300 people (according to students, thousands) were killed. The film replays this familiar carnage. But more poignantly, it documents the euphoria one can feel when the state gives way to mass resistance, the fatigue of infighting among strategists, and the bitterness and second-guessing that go on when the dream dies.

Those who watched and cheered the protesters from afar, thinking they say their younger selves flickering on CNN, may discover, after a look here at the ways defiant idealism can sometimes darken into blind folly, that they were more right than they ever wanted to know.

The headquarters of Long Bow in Brookline, Massachusetts, is a rickety shrine to Chinese pop culture and American information technology. A swaybacked, three-story gray house in a bucolic setting, it could be the off-campus hangout for wiseass M.I.T. undergrads. Mao memorabilia and kitsch cover the walls: Young Mao going to organize the workers, Mao greeting Elvis, Mao morphed with Marilyn or with Mona Lisa. Desks are strewn with Web manual and topped by aging desktop computers. On the stairs lies a copy of The Sayings of Pat Buchanan, which blends with the decor only because of its pungent title: “Deng Xiaoping is a chain-smoking, Communist dwarf.”

Major money went into this operation. The documentary had funding from the Ford and Rockefeller foundations, NEH, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (ITVS), and $150,000 from MCA Universal Studios. (By contract, Universal and Amblin, Steven Spielberg’s company, still own rights to any toys or amusement parks spun off the project.) A $25,000 AVID digital video-editing machine occupies a room upstairs. Otherwise, little of the $1.6 million that it cost to make the film is still evident. The motto at Long Bow: “Another day’s work, another day deeper in debt.”

“We have news,” says Richard Gordon, bounding down the stairs and handing me the latest “review.” An enthusiastic, funny, easily distracted man of 42 (his nickname for himself is “Aunt Blabby”), Gordon shoots and co-directs all the films that he works on with Hinton, who is upstairs on the phone talking to a reporter in San Francisco. (The couple live with their two children 15 minutes away in Dorchester.)

The “review” comes from the Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in Washington, D.C., the first time the government has dared put its views on paper. Composed on what one of the film’s writers, Geremie Barmé, calls “a really bad typewriter, a Unabomber typewriter” and sent to the director of the Washington international Film Festival, the letter urges removing the offensive work from their April schedule.

“As is well-known, a very small number of people engaged themselves in anti-government violence in Beijing in June 1989 but failed,” writes an embassy press officer. “The film the Gate of Heavenly Peace [sic] sings praise of the people in total disregard of the fact. If this film is shown during the festival, it will mislead the audience and hurt the feelings of 1.2 billion Chinese people.”

Everyone in the house is delighted to have a smoking gun, especially Barmé. An erudite Australian academic with a reputation for seditious mischief (and arrogance) in his field of contemporary Chinese studies, he had flown to “Gulag Long Bow” to help with the Web page, which includes an interactive Tiananmen. (Click on Mao’s mausoleum ion the Square and learn of its elevator, which takes the corpse up and down every day from the hall into an earthquake-proof chamber. Or stroll the Square as a “normal” or a “revolutionary” tourist.) Gordon’s job among the film’s opinionated collaborators was to speak up for “Joe Blow,” the viewer who wouldn’t know the many players or the subtle codes in which they speak; Barmé admits he “doesn’t give a fuck about Joe Blow.” Scornful of those who have credulously accepted Chai Ling’s and Li Lu’s version of events and embraced them as innocent martyrs, he wanted to call the film “Merchandising the Massacre.”

He fires off Long Bow’s reply: “Whereas we are heartened by any efforts of the diplomatic corps to engage in amateur film criticism and historiography, we feel that it is important that their naive enthusiasm not cloud the serious issues on which they choose to comment.” Bewildered by this “handful of people,” he cites the Beijing Evening News, which reported on August 3, 1989, that it took 156,000 people to wash away the 30,000 slogans and pick up the 80 tons of bricks after the disturbance. Then he e-mails both letters to friends in Australia where that night the futile effort to ban the film is a story again. CNN and the Washington Post also pick it up. Against an opponent that relies on such crude tools to stanch the flow of unwelcome information, the filmmakers have the Western media, as well as a better grasp of the truth, on their side. It almost isn’t a fair fight.

Visitors to Long Bow, though, can check their David and Goliath metaphors at the door. Gordon, Hinton, Barmé, and the film’s other writer, John Crowley, are good postmodernists. The narration subtly explores how tropes and rhetoric shape our understanding of the news and history. To accompany the famous TV footage of the young man facing down the tank in the streets of Beijing, reported quite differently by Dan Rather and Chinese commentators, the voiceover cautions that “events do not deliver their meaning to us. They are always interpreted.” No one who worked on “The Gate of Heavenly Peace” would deny his or her role as mediator either. They began on the assumption, says Hinton, that “China needs fundamental reforms.”

According to Barmé, it was Gordon who brought “the visual sense, the eye for the absurd detail” to the film. (A goofy clip of Bob Hope singing atop the Great Wall, sashaying through Tiananmen, golf club on his shoulder, is unmistakably Gordon’s work.) Hinton, on the other hand, has “an exhaustive knowledge of China and an exhausting need to be fair,” says Barmé dryly. “Carma wanted every event to be contextual. Richard knows that you have to tell history on film through images. He helps her focus. It’s symbiotic. But it can be tense to be around when they’re working together.”

As she summarizes it one afternoon around Long Bow’s kitchen table, “All the boring historical analysis is my fault. All the fun and interesting material that people actually like to watch is Richard’s.”

Four years older than her husband, Hinton is an impressive figure – beautiful, if severe. With her fast gait, little or no makeup, and cropped hair, she seems without pretension or time to waste. When not attending to her two children or this consuming project, she has been finishing her doctoral thesis in art history at Harvard (the topic is demons in 15th-century Chinese scroll painting).

I had seen Gordon and Hinton at the NYFF press conference after the first screening, and I went to the China Institute in February when she screened a section of the film by herself. Both times I was struck by her speech – the rapid cadences and dropped articles give her away as one who speaks Chinese more fluently than English – and by her candor about the failing of her film and the documentary form in general.

At the China Institute, she showed video clips of two Chinese students describing the same April 20 “atrocity” (when they petitioned the leaders inside Xinhuamen with demands and were rebuffed by guards). Only one student, Wuer Kaixi, made the final cut, however, because, as she said with chagrin, “He is more emotional and he turns up at other times throughout the film. We would have shown both clips, but the sky had changed color. We took the least bad path.”

Beginning the project with misgivings (“I knew you couldn’t satisfy any of the factions”), she had decided it needed doing while watching American TV coverage of ’89 in Boston. Her frustration and anger only grew while reviewing archival footage. “The news focused on slogans about democracy,” she told the room at the China Institute. “I noticed that almost no Chinese people who were interviewed in the Square had a chance to finish a sentence, much less a thought.”

The interviews she conducted for “The Gate of Heavenly Peace” are her way of filling in at least some of the record, even if she herself now feels trapped by the compromises of telling history with a camera. “Film is better suited to action than cool debate,” she said, making it clear which she prefers, “and whatever happens on camera carries more weight than events off camera.”

Over lunch in a deli not far from Long Bow, Hinton related pieces of her own history, a saga unto itself. her left-wing roots are wonderfully bizarre. A great-aunt, Ethel Voynich, wrote the 1897 novel, The Gadfly, which, although written in English and set in 19th-century Italy, became a bestseller, during the ’50s, in the Soviet Union. It was translated into 18 Soviet languages and became a movie and an opera. “Everyone there of a certain age knows it,” Hinton assures me.

Her grandmother, Carmelita Hinton, for whom she is named, founded the progressive-minded Putney School in Vermont. Her parents met there. William Hinton read Edgar Snow’s Red Star Over China and set off in 1945 to work in China with the U.S. government’s Department of War Information. He learned to admire Mao and Zhou, then still holed up in the hills. In 1948 his wife joined him; and a year later – two months after Mao declared the People’s Republic in Tiananmen Square – Carma was born, a revolutionary baby.

“Even though I had friends, I was constantly made aware that I didn’t belong,” says Hinton of a foreign childhood complicated further by her parents’ estrangement soon after her birth. (She did not see her father for 18 years. He returned to the U.S. in 1953 just in time for the McCarthy era. His passport was confiscated along with a footlocker of notes he had taken about a Chinese village called Fanshen, or Long Bow. After the obligatory HUAC showdown, he sued the government for his papers and wrote his book in the U.S., returning to China in 1971 as a hero.)

A teenager in Beijing when Mao unleashed the Cultural Revolution in 1966, Hinton was thrilled to learn from the denunciation of old leaders that not all Communists were correct: “That was a revelation.” She lacked a cadre pedigree to qualify as a Red Guard, but she wrote posters, left school, and traveled to the countryside. “The Cultural Revolution fed our anti-authoritarian feelings. It was like a vacation. There was supposed to be freedom now to create. And what did they create? Terror.”

In the behavior of Chai Ling and others in the Square during ’89, Hinton recognizes many of the same slogans and attitudes from her teenage years. “During the Cultural Revolution, we didn’t take a single step to build anything up. There was no school. We had a ball. We learned that everyone should have a say. But then what? We never got around to creating structures. Did we change anything except attack?”

“The Democracy Movement in ’89, same thing. They could only shout slogans about revolution again. That’s the only language they know. Everyone wanted to go straight to the top and tamper with national politics, instead of doing hard, practical work for democracy on a local level. Partly because of Communism, people don’t know how to talk to the government, and the government certainly doesn’t know how to talk to them.”

Hinton viewed the Chinese leadership close-up in 1971 when she reunited with her father, who took her to Fanshen/Long Bow. She sat in on five meetings he had with Zhou Enlai, some lasting all night. But the chief lesson she took away from the experience was: “Every political leader has to be smooth and diplomatic and can’t tell the truth.”

Disillusion with China led her to leave soon afterward (she arrived in Hong Kong the day Kissinger’s visit was announced.) At the University of Pennsylvania, where she met Gordon, she planned to be an artist but “couldn’t find a voice that was meaningful.” Not until she and Gordon returned to Long Bow in 1979 to make a film on stilt dancers did she recover her feelings for the country. She also hit upon a career. They have returned to the village every couple of years to make four other films, all of them grounded in the routines and texture of daily life.

Given that Hinton has quite deliberately followed in her father’s footsteps, I was curious what he thought of the film. I knew the two had serious political differences. “He doesn’t like it,” she says with a touch of exasperation as she hands me his number and fax in Outer Mongolia, where he lives with his new wife. “But I’ve learned not to speak for him.”

I had never called Ulan Bator before and I wasn’t sure phones would reliably connect me. But William Hinton picked up on the second ring and, after turning down the television, proceeds to praise the film (“the best thing that’s been done”) and then run it down.

“The unrest was much greater all over China than anyone could get on film,” he says in a hearty voice. “Carma wasn’t here. I was. I thought the blame for what happened should have been squarely on Deng. It’s true the students were provocative. But the government should be much more mature and far-seeing. You don’t slaughter your own people. They lost 50 years of love and prestige with that move.”

His objections rhyme with those voiced by many of the student writers of Tiananmen, with a macabre twist. William Hinton sees Deng as the villain, too, but mainly because of his capitalist reforms. It’s clear I have entered a time tunnel when I ask if he minds being called “an unrepentant Maoist.”

“What’s to repent?,” he thunders. “Mao had nothing to be ashamed of or be sorry for. Mao was struggling hard for a Socialist China and was defeated. One of the problems with the film is that Carma didn’t find anyone who admired Mao. There are a lot of cheap shots at him in the film.. Among the peasants Mao’s prestige was and remains very high.”

This is only too true, as Shades of Mao, Barmé’s new book on the post-’89 nationalist cult of the Great Leader, documents. But even if many viewers bring to “The Gate of Heavenly Peace” their own agenda, few are likely to share William Hinton’s belief that the ultimate blame for the bloodbath lies not with Mao and his legacy of terror, but with Deng, who betrayed the revolution.

At one level the film reveals the grotesque miscommunication that took place at Tiananmen. The aging Communist hard-liners, living off waning revolutionary energy, couldn’t help but see any questioning of its authority as “counterrevolutionary” or, in the stock denunciation of the late ’80’s, “bourgeois liberalism.” Neither the students nor any other group had avenues to petition for reform and so, finally, they took to the streets. But as the film eloquently says: “When individuals stand up to power, they bring to the encounter the lessons that power has taught them, and the harm it has done them. Merely to stand up does not free us from these things.”

Not that anyone at Long Bow is a relativist. The scholarly credentials on the film are impeccable. Orville Schell was a producer; Jonathan Spence, Jeffrey Wasserstrom, Gail Hershatter, Andrew Nathan, and others consulted. One reason the film took so long and cost so much was the care taken not to screw facts into ready-made forms. David Carnochan edited with help from a book on daily weather in Beijing during ’89, making sure the 200 to 300 hours of new footage they collected were properly dated in the chronology.

“We had some great material that we thought was shot on the night of June 3,” says Gordon, “But it turned out to be June 2 and we had to start over. David became an expert on reading the sky for clues.”

The most charged archival footage in the film is an interview with Chai Ling on May 28, six days before the military crackdown. [The complete Chinese transcript of this interview is available on the Chinese Gate website.] The tiny, frail 23-year-old graduate student, who emerged as self-proclaimed Commander in Chief of Defend-Tiananmen Square Headquarters, confesses to American journalist Philip Cunningham her despair over the movement. Shot with a home video camera in a Beijing hotel room, which adds a voyeurist seaminess to the scene, Chai seems hysterical, understandable after a hunger strike and with thousands of groups massed at the edge of the city.

She thinks that other student leaders are “after my power” and expresses the need to “resist compromise, resist these traitors.” Her despair with the movement has led her to the belief that “you, the Chinese, are not worth my struggle! You are not worth the sacrifice.”

Finally, in words that sound eerily like a Weatherwoman who thinks that only deadly backlash will expose the true face of Fascist America, she says, “The students keep asking, ‘What should we do next? What can we accomplish?’ I feel so sad, because how can I tell them that what we are actually hoping for is bloodshed, for the moment when the government has no choice but to brazenly butcher the people? Only when the Square is awash with blood will the people of China open their eyes. Only then will they really be united. But how can I explain any of this to my fellow students?”

This statement has turned into a sideshow of its own, with Chai Ling and her supporters claiming that the Chinese word “qidai” [期待] should be translated as “expect” rather that “hope for.” But even if this were true (and according to most translators, it isn’t), her other sentiments are peculiar enough.

Did the student leadership urge people to stay in the Square for their own glorification, even after they suspected that the PLA was willing to pull back again? Was a window of opportunity closed in the middle of May, when small-scale democratic forums might have been set up? Or was it inevitable that Li Peng’s hardliners would smash the moderates in the party?

The questions are crucial and still much debated in China. Many intellectuals, such as Dai Qing, who appears in “The Gate of Heavenly Peace,” regard Chai Ling as “a criminal.” The most agonized figure in “Moving the Mountain” is Wang Xiaohua [sic], who weeps because she feels responsible for leading young people to slaughter. Wei Jingsheng, now in prison in China and the leading intellectual figure of the Democracy Movement since the ’70s, has criticized the students for “acting foolishly.” He did not want to appear in “Moving the Mountain” according to the research director on that film, Drew Hopkins, if Li Lu were to be canonized, which is what happened.

Chai Ling, who eluded the police and has also settled in Boston, refused many attempts to be interviewed for “The Gate of Heavenly Peace”. Nor would she speak to me. At first she was “too busy.” When I offered to call at another time, she said with fatigue, “It’s over. I don’t want to get involved.” Under her China Dialogue foundation, however, she has gone about denouncing the film. Plugged into the human rights movement, she advised Hillary Clinton, before her trip to Beijing for the International Women’s Conference, according to Gordon and Hinton. “If Washington listens to her, no wonder things are so screwed up,” grouses Hinton.

[Note: For Chai Ling’s repeated attempts to sue the Long Bow Group, see here. — Ed. China Heritage.]

The uproar before the film was seen underlines the investment that all sides had in their versions of the truth. Besides the Chinese government, the Human Rights community also had something to lose in a cold, hard look at certain facts. Having presented the students who escaped to the U.S. as pure young idealists (a process that reached its apotheosis in Li Lu, star of “Moving the Mountain”), some worried that “The Gate of Heavenly Peace” would come down too hard on Li and Chai Ling when, after all, the government did the killing. Imagine a rumor that an upcoming film would blame the students for what happened at Kent State.

In June 1995, two weeks after Tiananmen magazine appeared, with its attack on the film as well as on “the overlord of the American media, The New York Times,” Gordon and Hinton got a call from Orville Schell who had heard from Robert Bernstein. An active champion of human rights who aided any number of Soviet rebels, including Sakharov, Bernstein is the former head of Random House. Under his own imprint at John Wiley, he publishes banned writers from around the world; he controls the English-language rights to the writings of Wei Jingsheng. (Bernstein’s efforts have earned him the nickname, “Dissident, Inc.”)

“Bernstein and two other prominent human rights organization executives held a conference call with Orville Schell (producer on our film),” states Gordon in a letter to me. “They expressed concern…about the way that Li Lu was going to be presented. They demanded that we interview him for the film, and asked to see transcripts relating to him. We responded that they should see the film before passing judgment… and that our film was complex. … We most certainly were not ‘blaming the students for the massacre.’

“I was upset because… Sidney Jones [head of Asia Watch] and Robin Munro [director of Asia Watch’s Hong Kong office] had been very helpful to us throughout the process of making the film. Bob Bernstein himself had written a letter to Chai Ling on our behalf, asking her to give us an interview. … However I felt that… based on his personal friendship with Li Lu, Bob had crossed over a line. He is a very powerful man, and he was applying a great deal of pressure on Orville Schell.”

Gordon, Hinton, and Schell did not give in. But they agreed to screen a rough cut for Bernstein and the two other concerned members, if Barmé and Marilyn Young of NYU could also attend. Bernstein canceled the meeting, though, when a screening room supposedly could not be found.

Bernstein denies that any pressure was put on them. “I think the film is wonderful,” he says. “It should have been nominated for an Academy Award.”

But Gordon’s account is backed up by a fax from Schell to the filmmakers at that time (and now in possession of the Voice), as well as by the testimony of Hinton and Barmé. Neither Bernstein nor Schell would return my calls asking for clarification.

No one can dispute Bernstein’s stellar record in defense of human rights around the world, or the catalogue of torture and killing in China before and after ’89. But a naive and uncritical view of those events in the U.S. has led to its own distortions. The veneration of Li Lu is a prime example.

The tailoring of Chinese dissidents for American consumption would make a delicious study in radical chic. Barmé, who has directed the Tiananmen Documentation Project at the Australian National University since 1989, finds no evidence that Li held any strong political convictions until he appeared in the Square, three weeks before the massacre. From then on, he seems to have done little except conspire with Chai Ling to suppress moderate voices in the student movement. In the hagiography of Li that is “Moving the Mountain” (directed by Michael Apted and Sting’s wife, Trudie Styler), his own self-importance (“I just hope that when history calls I will be ready”) seems matched only by the need of the filmmakers to fashion a bright, attractive, English-speaking “star.” Drew Hopkins, who says he worked hard to bring historical perspective to the film, describes the final product as “shameful and sloppy. And that’s too bad because it didn’t start out to be an ideological vehicle for Li Lu.”

Stroked by Charlie Rose and puffed in The New York Times, Li has become, as Gordon says, the “token dissident of New York café society.” The PR machine behind this man is formidable. Don’t miss the fawning “Talk of the Town” piece about his graduation from Columbia Law and Business School in last week’s New Yorker, in which the young dissident is compared to Nelson Mandela after taking a stretch limo to a party thrown in his honor by billionaire John Kluge. Neither the writer of the article, James Traub, nor his editors found anything odd, not to say, sickening, in equating a young man who basked a few weeks in the spotlight of Tiananmen and is now entertaining offers from Lazard Frères with a resister of conscience jailed for decades because of his unshakable beliefs.

Those who went to prison in China for democracy, like Wang Dan and Wei Jingsheng, continue to fight and make sacrifices that those who fled did not. “The Gate of Heavenly Peace” in no way condemns anyone for leaving. What American would dare? But in its own incoherent fashion, “Moving the Mountain” asks the question: Where is the best place to apply pressure on China? Wei Jingsheng cautions that those dissenters who have left are condemning themselves to alienation from the ongoing struggle. “It is like bidding farewell to oneself,” he says with a smile.

“We didn’t have anything against Li Lu,” explains Barmé. “But he’s nothing but a creation of the American media. He was such a minor figure that we didn’t think we needed to interview him. He just didn’t count.”

The literary critic Liu Xiaobo, whose ironic views on ’89 are a highlight of the documentary, once wrote a mordant essay entitled “That Holy Word, ‘Revolution’.” He skewers his country for its hopeless love affair with the concept throughout the 20th century: “In Communist China there is no word more sacred or richer in righteous indignation and moral force than ‘revolution’ … Again and again in the name of ‘revolution,’ individuals have been stripped of all the rights that they ought to enjoy…. Each and every one of us is both victim and carrier of that word ‘revolution.'”

He goes on to analyze the figure of the Communist Party (“If it continues to uphold one-party despotism, it will perish”), and toward the end discusses how and when to play the “June 4th card” so that “those who rose to power on [its] blood” can be removed and those who “fled overseas can safely return home.” But he closes by wondering “if we university students and intellectuals who played the role of revolutionary saints and democratic stars for two months can reasonable, calmly, justly, and realistically reevaluate what we did and thought in 1989.” Written in 1993, the essay predicts all too well the volleys of denunciations that have rained down on the first film to look critically at that watershed year.

“The Gate of Heavenly Peace” is far from definitive. Without the testimony of the Chinese government, which not surprisingly declined Hinton’s many requests for interviews, actions must be inferred. Their silence (and Chai Ling’s) also allows them to safely dismiss the work as propaganda by a “bunch of foreigners.”

But the film also funnels everything through Tiananmen, when the outrage in ’89 had spread across the country, into every major Chinese city. And impartiality can only take one so far in understanding an event of this magnitude. In the film’s cool recital of what happened when, one misses the fact that to stand up to power is often, by definition, to be a “criminal” and “irresponsible.”

Xiao Qiang, who joined Human Rights in China after watching the turmoil of ’89 from the U.S., can barely speak about Tiananmen without clenching up. “It is so personal, my reaction to this film,” which he praises as “very important, the only one of its kind that isn’t sensationalistic.” But he can’t help but feel dissatisfied to see it exhumed as dates and strategies.

“It wasn’t only a political event,” he says. “It was a moral event, even spiritual, to me. We lived and grew up in a repressive society. That moment of liberation, that feeling of freedom in the spring of ’89 was the first time people realized what was missing. And then to be brutally crushed.” He stops, his voice breaking. “It wasn’t just win or lose. June 4 created a new attitude to life. It wasn’t romantic, it was real.”

***

Source:

- Richard B. Woodward, ‘Anatomy of Massacre’, The Village Voice, 4 June 1996