Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium

Appendix LI

好話說盡,壞事幹絕

On 1 October 2023 National Day, we return to the well-worn mendacity that underpins the Chinese party-state. We do so by recalling the ‘Golden Millet Dream’ 黃梁夢, an old story about the fleeting nature of success, the whims of autocratic fiat and frustrated aspiration. We note the recent ban on a comic opera about the ‘Golden Millet Dream’ that was staged in Handan 邯鄲, Hebei province, the place where the millet dream originated in the Tang dynasty.

[Note: See also The Fog of Words: Kabul 2021, Beijing 1949, 25 August 2021; and, The Right to Know & the Need to Lampoon, 18 October 2021.]

In keeping with the theme of ‘tedium’ in the present series, we revisit some old observations on China’s National day before spending a moment with the essayist and calligrapher Liu Chan, an artist whose work often features in The Other China section of this website. This is followed by an excerpt of the banned opera, a translation of its most popular aria and the Chinese text of the Tang-dynasty story on which the opera was based.

As we have previously noted, for us the ideological and policy landscape of what, from late 2012, would be known as the Xi Jinping era, was gradually becoming evident from as early as 2007. In many respects, the year 2023 marks the fifteenth year of China’s Empire of Tedium.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

1 October 2023

***

More from The Empire of Tedium:

- Chapter Twenty-one 醒 — Awakenings — a Voice from Young China on the Duty to Rebel, 14 November 2022

- Chapter Twenty-two 官逼民反 — Fear, Fury & Protest — three years of viral alarm, 27 November 2022 (see also Appendix XXIII 空白 — How to Read a Blank Sheet of Paper, 30 November 2022; Appendix XXIV 職責— It’s My Duty, 1 December 2022; and, Appendix XXV 贖 — ‘Ironic Points of Light’ — acts of redemption on the blank pages of history, 4 December 2022)

- Chapter Twenty-three — Chinese Time, Part I: 新鬼舊夢— More New Ghosts, Same Old Dreams, 1 January 2023; Part II: 忘卻的紀念 — the struggle of memory against forgetfulness, 2 January 2023

The Official 1 October National Day:

- CCTV,烈士紀念日向人民英雄敬獻花籃儀式,油管,2023年10月1日

- CCTV,《中國夢·家國情——2023國慶特別節目》,油管,2023年10月1日

- HKTB, 《攜手共融,同賀國慶|中華人民共和國成立七十四周年》,油管,2023年10月1日

An Unfficial take on 1 October National Day:

- 二爺故事,祖國沒有生日:常識的陷阱,油管,2023年10月2日

Fifteen Years and Counting

When Beijing celebrated the sixtieth anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic, I observed that:

The year 2009 was marked by a series of important anniversaries in the history of the People’s Republic of China. Some of these were commemorated with due pomp and circumstance in the official media and dissected at length during learned gatherings and discussions. Others, those events that I think of as ‘dark anniversaries’, passed by in an atmosphere of heightened alertness, surveillance and official anxiety. Dark anniversaries are the signposts of quelled protests, social unrest and state violence, events such as the 1959 rebellion in Lhasa, the shutting down of the Xidan Democracy Wall in Beijing in 1979, the tragedy of the 1989 protest movement and the religious repression of 1999. Such events offer alternative narratives to the official Party-state story of modern China; an understanding of them also contributes to our appreciation of the ways that the strong unitary state, and its anxieties, has evolved over the past decades. The ‘forgotten dates’ in the official Chinese calendar offer a penumbra of history; they stand in shaded contrast to vaunted moments the commemoration of which is carried out in the merciless glare of publicity and official largesse. Although formally ignored, or recalled only in verso, the dark anniversaries cast a gloomy shadow over the orchestrated son et lumière of state occasions. …

As China continues along the trajectory it is enjoying as a strong, and increasingly willful, modern power it therefore becomes necessary to speculate about the future enterprises of not only the Party-state that rules China, but of the Chinese people collectively. While the orchestrated mass celebrations of the People’s Republic were being held in Beijing, thoughtful writers and thinkers recalled the solemn undertakings that had originally brought the Chinese Communist Party to power shortly after the Second World War. In a country racked by years of invasion and internecine strife and economic collapse, at that time the Communists not only offered national unity and economic stability, they also won over the urban classes and intelligentsia by declaring that they would create a polity that instituted political democracy and secured human rights in ways unachieved by the Nationalist government of Chiang Kai-shek. During the late 1940s, in countless essays, editorials, speeches and documents, time and again China’s revolutionary leaders undertook to fulfill the promise of China’s original revolution of 1911 that had seen the end of dynastic autocracy. It was a promise to realize national prosperity and democratic politics.

— from Geremie R. Barmé, China’s Promise, January 2010

At the time, we noted an important, indeed unique, collection of articles, speeches and editorials by Communist writers and leaders from the Chinese Civil War in which they repeated solemn declarations that the Party would institute democracy and human rights in a New China. See Xiao Shu 笑蜀, The Promises of History 歷史的先聲——半個世紀前的莊嚴承諾, Shantou: Shantou daxue, 1999 (for the full text of this important work, see here; and, for an official Chinese criticism of the book for including ‘Paean to Democracy’ 民主誦, the authorship of which was mistakenly attributed to Mao Zedong, see here). Xiao Shu’s collection was published to coincide with the fiftieth anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic in 1999. It was soon banned.

In 2010, I also remarked that:

As China continues on its path to become a major world influence, it is important that we remain heedful of the complex realities of China’s society and the varying demands of its citizens. As international criticisms of China’s failure to realize a social and political transformation concomitant with its economic achievement, the Chinese authorities have become increasingly anxious to present their monolith version of Chinese reality to the world as the only truly Chinese story worthy of our consideration. The Chinese Party-state, with the support of many citizens nurtured by a guided education and media industry, is now investing massively in presenting what it calls the ‘Chinese story’ (Zhongguode gushi 中国的故事) to the rest of the world. However, in doing this, it constantly limits and censors the variety of stories and narratives that make up the rich skein of human possibility in China itself. To many it would appear self-evident that no political force can or should claim to represent in its entirety or in perpetuity such human richness.

[Note: For more on the ‘Xi-era foreplay’, see Red Allure & The Crimson Blindfold.]

During the celebrations of China’s National Day day on 1 October 2023, online writers and nostalgics of various persuasions recalled the ‘Common Program for the Peaceful Construction of China’ 《和平建國綱領》, a 1946 policy agreed to by both the Nationalist government and the Communist insurgents in concert with other political parties. Abandoned as a result of the civil war that broke out later that year, the Common Program was reformulated following the Communist victory in 1949. Even the resuscitated version could not withstand the imperious aspirations of the Communists and before long it too was abandoned during the civil war that Mao and his comrades launched on the nation, one which has to a greater or lesser extent continued to this day.

[Note: For more on this topic, see 榮劍, 回到《共同綱領》(1946), 2013年6月10日; and Rong Jian 荣剑, Unthinking China 沒有思想的中國, The China Story, 2017.]

My Day

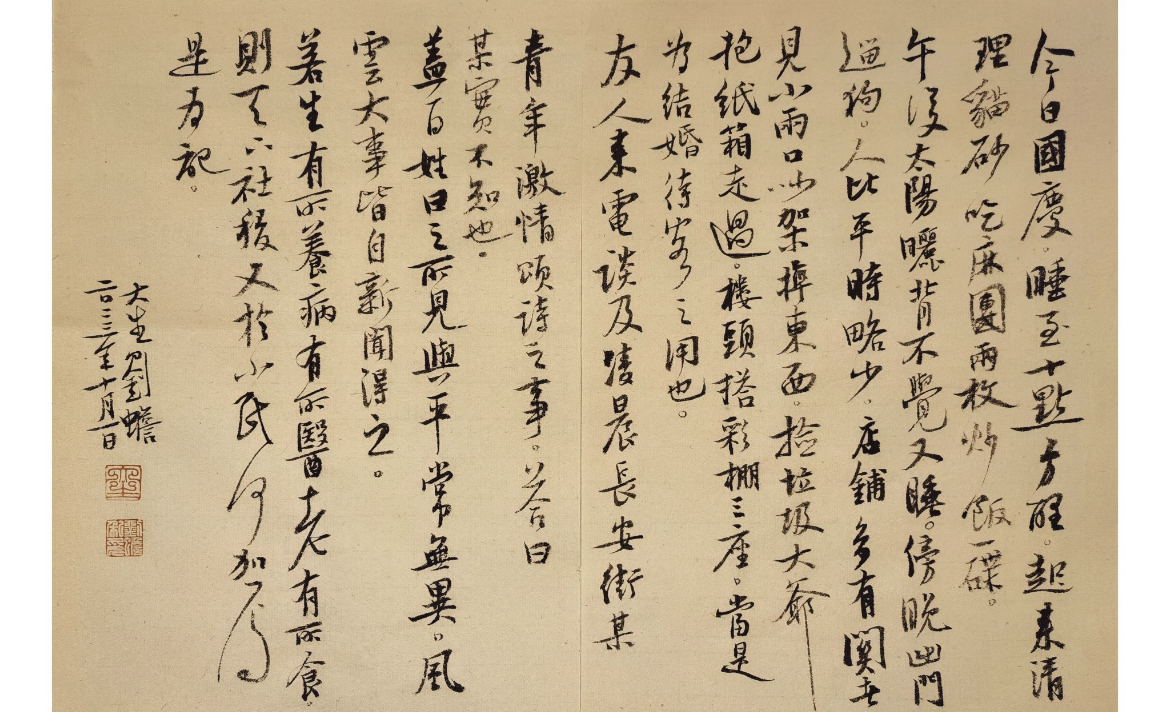

Liu Chan

‘The 1st of October National Day and I slept until 10:00am. After cleaning the cat’s litter tray I ate a couple of sesame balls and a plate of fried rice. Basking in the midday sun I nodded off to sleep again only waking in the early evening when I took the dog for a walk. There were fewer people out and about than usual and lots of businesses were closed. I saw a couple having a fight and throwing things. The old garbage collector walked by holding a carton. There were three festive marquee tents put up outside our building, probably for a wedding. A friend rang me up and told me about how they’d encountered a young person on Chang’an Avenue reciting some poem with gusto. I replied that they were completely clueless. Otherwise, everything was pretty much as usual and as usual the major events of the day were reported by the media. If people are just able to go about their lives as usual without the great affairs of state interfering with them, then I reckon that they’re doing passably well.

‘Herewith my record of this day.’

— Dasheng Liu Chan, 1 October 2023

The Well-Done Song

好了歌

Cao Xueqin

曹雪芹

translated by David Hawkes

Men all know that salvation should be won,

But with ambition won’t have done, have done.

Where are the famous ones of days gone by?

In grassy graves they lie now, every one.

Men all know that salvation should be won,

But with their riches won’t have done, have done.

Each day they grumble they’ve not made enough.

When they’ve enough, it’s goodnight everyone!

Men all know that salvation should be won,

But with their loving wives they won’t have done.

The darlings every day protest their love:

But once you’re dead, they’re off with another one.

Men all know that salvation should be won,

But with their children won’t have done, have done.

Yet though of parents fond there is no lack,

Of grateful children saw I ne’er a one.

世人都曉神仙好,

唯有功名忘不了,

古今將相在何方,

荒塚一堆草沒了。

世人都曉神仙好,

只有金銀忘不了,

終朝只恨聚無多,

及到多時眼閉了。

世人都曉神仙好,

只有嬌妻忘不了,

君生日日說恩情,

君死又隨人去了。

世人都曉神仙好,

只有兒孫忘不了,

癡心父母古來多,

孝順兒孫誰見了。

— from Cao Xueqin, The Story of the Stone, Volume 1: The Golden Days, translated by David Hawkes, Penguin, 1973, pp.63-64 and quoted in In Memoriam — Pierre Ryckmans (Simon Leys), 11 August 2021

***

***

Golden Millet Dreams in Xi Jinping’s China

《黄粱梦》

A full version of the comic opera Golden Millet Dream was first staged in 2009 and has enjoyed a run of over 600 performances in towns and cities throughout China. A new production was put on in 2022 and in 2023 the show suddenly enjoyed renewed success. Critics suggest that its popularity was due to the slapstick rendition of a classic tale that mocks a pompous ruler and the feckless bureaucrats with whom he surrounds himself. As in the original story, the modern opera ends with the deluded hero of the piece waking from his dreams of vainglorious achievement.

In the online Chinese world, the most popular aria in the opera, sung lustily by the chorus, goes:

Endless the displays of luxury, limitless the lust for power

Insatiable greed for fine foods, always more money to burn

Never tiring of the paeans and ever expecting new gifts

Riches can never satisfy, celebrations pile one on the other.

Yet it all amounts to a Yellow Millet Dream!

擺不完的闊氣,弄不完的權。

吃不完的珍饈,花不完的錢。

聽不完的頌歌,收不完的禮。

享不完的富貴,過不完的年。

不過是一場黃粱美夢!

— from the libretto of the Hebei regional opera Golden Millet Dream

***

Golden Millet Dream is a modern comic theatrical work in the style of a classical regional opera form in Hebei province called Pingdiao Luozi 平調落子. Developed over some years, it was originally staged in 2009, the opera was written in an eclectic style including comic interludes, satirical commentary, magic, rap and a variety of dance styles. In some regards, it recalled Pan Jinlian 潘金莲, an uproarious Sichuan opera created by Wei Minglun (魏明倫, 1941-) that created a cultural controversy in the mid 1980s (see my essay on that opera: 荒誕川劇《潘金蓮》的風波,《九十年代月刊》,1986年8月).

As Xi Jinping’s rule entered an increasingly paranoid phase, the rather run-of-the-mill satire in Golden Millet Dream panicked China’s propaganda apparat and the work was banned in late September. Its fate brings to mind the band Slap 耳光, whose work was outlawed in mid August 2023. See Tired of Winning Yet, China? — The Band Slap Has Some News for You, 14 June 2023

For a recording of the full opera, see:

***

In the late-Ming dynasty, as Lynn Struve notes, ‘shorthand terms—“Lu’s dream” 呂夢, “yellow millet dream” 黃梁夢, “south branch dream” 南柯夢, and “ants dream” 蟻夢—came to be used for self-deluding hopes of grand attainment beyond one’s present condition in life. … “Lu’s dream” 呂夢 and “yellow millet dream” 黃梁夢 alluding to the story “Within a Pillow” 枕中記, attributed to Shen Jiji (沈既濟, ca.750-ca.800).’

‘Both tales belittle the world of striving and suffering over false ideas of entitled success by condensing dreams of lifetimes of ups and downs into very short spans of objective time. … In “Within a Pillow” a somewhat threadbare young man, Student Lu, meets an old Daoist named Lü at an inn on Handan Road and vents his unhappiness over poor prospects of gaining renown and enriching his family by becoming a general or high minister of state. As the innkeeper begins boiling a pot of yellow millet to serve, the young man grows sleepy, so Old Man Lü lends him a ceramic pillow that “should lead him to glories suited to his aspirations.” As Student Lu falls asleep, he notices a brightness within the air hole at one end of the pillow and, at least in spirit, enters the pillow’s hollow interior. Therein he experiences marriage into an aristocratic family, the births of many children and grandchildren, passage of the highest civil service examination, successes in both civil and military positions, the perils of intra-bureaucratic jealousies and factional warfare, and ultimately a sumptuous life and the highest confidence of the emperor. Upon his dreamed death at age eighty, Student Lu awakes to find that the innkeeper’s pot of millet is not yet done—in other words, all he had hoped for and suffered was no more significant than the interval of a mere doze. He thanks Old Man Lü for his instruction, which has “stanched his desires,” and takes his leave.’

— from Lynn A. Struve, The Dreaming World and the End of the Ming, University of Hawai’i Press, 2019, pp.34-35

***

The following is the Tang-era story 傳奇 (‘tale of the marvelous’) on which Golden Millet Dream is based:

枕中記

沈既濟

開元七年,道士有呂翁者,得神仙術,行邯鄲道中,息邸舍,攝帽弛帶隱(憑倚)囊而坐,俄見旅中少年,乃盧生也。衣短褐,乘青駒,將適於田,亦止於邸中,與翁共席而坐,言笑殊暢。

久之,盧生顧其衣裝敝褻,乃長歎息曰:大丈夫生世不諧。困如是也翁曰:觀子形體,無苦無恙,談諧方適,而歎其困者,何也。生曰:吾此苟生耳,何適之謂。翁曰:此不謂適,而何謂適。答曰:士之生世,當建功樹名,出將入相,列鼎而食,選聲而聽,使族益昌而家益肥,然後可以言適乎。吾嘗志於學,富於遊藝,自惟當年青紫可拾。今已適壯,猶勤畎畝,非困而何。言訖,而目昏思寐。時主人方蒸黍。翁乃探囊中枕以授之,曰:子枕吾枕,當令子榮適如志。

其枕青甆,而竅其兩端,生俛首就之,見其竅漸大,明朗。乃舉身而入,遂至其家。數月,娶清河崔氏女,女容甚麗,生資愈厚。生大悅,由是衣裝服馭,日益鮮盛。明年,舉進士,登第釋褐,秘校,應制,轉渭南尉,俄遷監察御史,轉起居舍人知制誥,三載,出典同州,遷陝牧,生性好土功,自陝西鑿河八十里,以濟不通,邦人利之,刻石紀德,移節卞州,領河南道采訪使,征為京兆尹。是歲,神武皇帝方事戎狄,恢宏土宇,會吐蕃悉抹邏及燭龍莽布支攻陷瓜沙,而節度使王君㚟新被殺,河湟震動。帝思將帥之才,遂除生御史中丞、河西節度使。大破戎虜,斬首七千級,開地九百里,築三大城以遮要害,邊人立石於居延山以頌之。歸朝冊勳,恩禮極盛,轉吏部侍郎,遷戶部尚書兼御史大夫,時望清重,群情翕習。大為時宰所忌,以飛語中之,貶為端州刺史。三年,征為常侍,未幾,同中書門下平章事。與蕭中令嵩、裴侍中光 庭同執大政十餘年,嘉謨密令,一日三接,獻替啟沃,號為賢相。同列害之,複誣與邊將交結,所圖不軌。制下獄。府吏引從至其門而急收之。生惶駭不測,謂妻子曰:吾家山東,有良田五頃,足以禦寒餒,何苦求祿?而今及此,思短褐、乘青駒,行邯鄲道中,不可得也。引刃自刎。其妻救之, 獲免。其罹者皆死,獨生為中官保之,減罪死,投驩州。數年,帝知冤,複追為中書令,封燕國公,恩旨殊異。生子:曰儉、曰傳、曰位,曰倜、曰倚,皆有才器。 儉進士登第,為考功員,傳為侍御史,位為太常丞,倜為萬年尉,倚最賢,年二十八,為左襄,其姻媾皆天下望族。有孫十餘人。

兩竄荒徼,再登臺鉉,出入中外,徊翔臺閣,五十餘年,崇盛赫奕。性頗奢蕩,甚好佚樂,後庭聲色,皆第一綺麗,前後賜良田、甲第、佳人、名馬,不可勝數。

後年漸衰邁,屢乞骸骨,不許。病,中人候問,相踵於道,名醫上藥,無不至焉。將歿,上疏曰:臣本山東諸生,以田圃為娛。偶逢聖運,得列官敘。過蒙殊獎,特秩鴻私,出擁節旌,入升臺輔,周旋內外,錦歷歲時。有忝天恩,無裨聖化。負乘貽寇,履薄增憂,日懼一日,不知老至。今年逾八十,位極三事,鐘漏並歇,筋骸俱耄,彌留沈頓,待時益盡,顧無成效,上答休明,空負深恩,永辭聖代。無任感戀之至。謹奉表陳謝。詔曰:卿以俊德,作朕元輔,出擁藩翰,入贊雍熙。升平二紀,實卿所賴,比嬰疾疹,日謂痊平。豈斯沈痼,良用憫惻。今令驃騎大將軍高力士就第候省,其勉加針石,為予自愛,猶冀無妄,期於有瘳。是夕薨。

盧生欠伸而悟,見其身方偃於邸舍,呂翁坐其傍,主人蒸黍未熟,觸類如故。生蹶然而興,曰:豈其夢寐也。翁謂生曰:。人生之適,亦如是矣。生憮然良久,謝曰:夫寵辱之道,窮達之運,得喪之理,死生之情,盡知之矣。 此先生所以窒吾欲也。敢不受教。稽首再拜而去。