Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium

Chapter II

Part II

古今多少事,都付笑談中

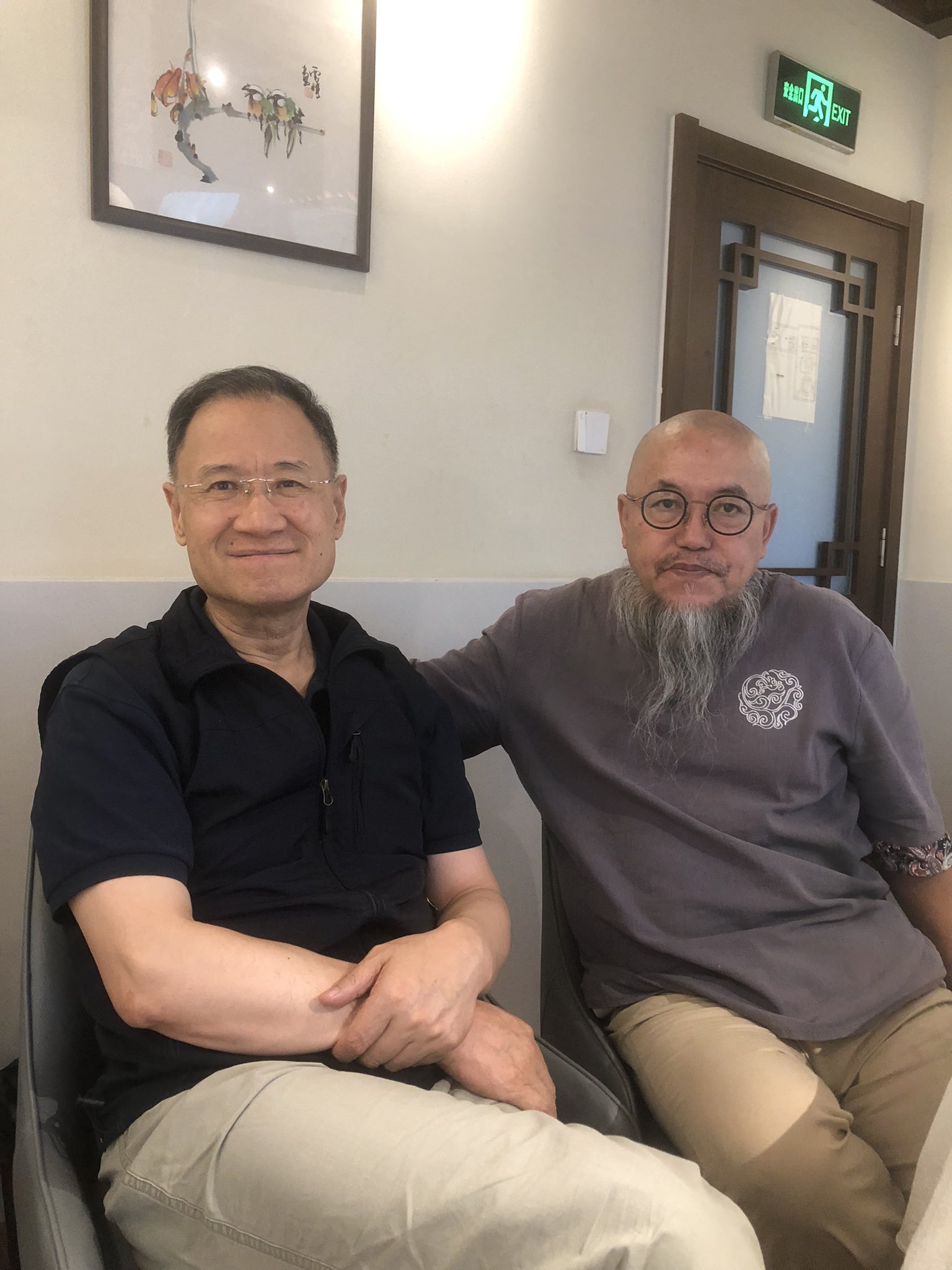

During Mid Autumn Festival 2024, Xu Zhangrun, legal scholar, Xi Jinping critic, purged academic and one of Beijing’s defiant Former People, was able to meet up with Jifeng 季風, a vagabond democracy activist. In an autobiographical note Jifeng describes himself as a:

Prisoner of the State, leader during the 1989-June Fourth Student Movement, a thinker in the depths of night, poet. A solitary wanderer who wavers while making a way along the highways and byways of contemplation, I have survived ‘elsewhere’ for over three decades, in the Other Places of this nation. I write with my left hand to make a living while continuing to fashion soulful expression with my right. Having resided in Shenzhen for ten years, I never became a Shenzhen person, nor am I a Beijinger, although I have lived in Beijing for over two decades. My internal exile has taken a path through much of China and I have moved my home over thirty times. To this day I fend where I can and live as I must.

當代國家囚徒,八九六四學運帶頭人,黑夜中的思想者,思考者,詩人,躑躅中孤獨的夜行人。三十多年來生活在別處,這個國家的別處,左手寫文案賺錢度日,右手寫文章陶治情操。深圳暫住十年非深圳人,北京暫住了二十多年仍不是北京人,被流放了大半個中國,搬了三十多次家,至今仍食無定處,居無定所。

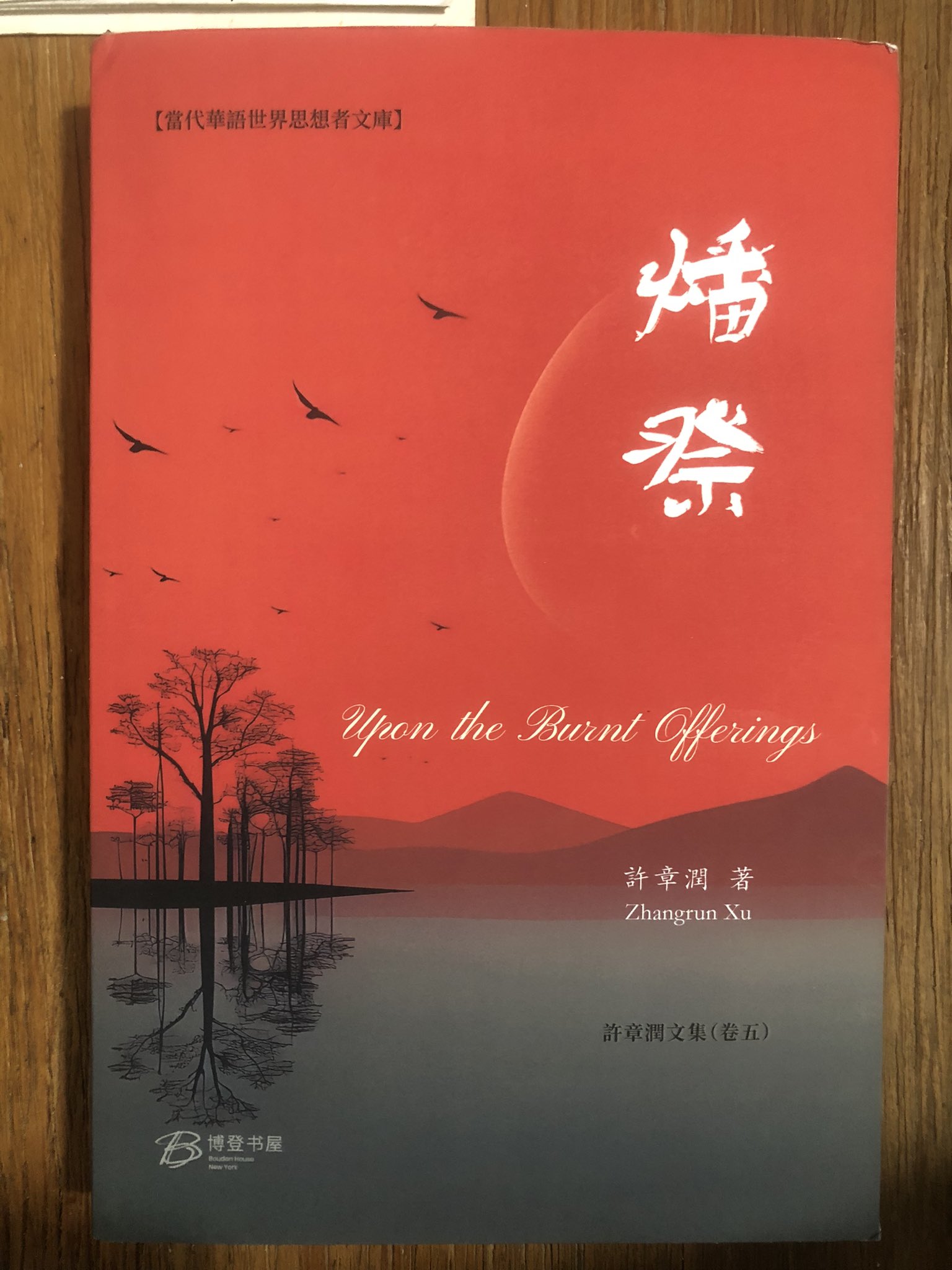

Jifeng’s meeting with Xu Zhangrun was hard won. Both men have been harried by the authorities and it was with difficulty that they found a spot to see each other. During the encounter, Xu Zhangrun gave Jifeng a copy of Burnt Ashes 燔祭, a collection of poetry published in late 2023. The manuscript for the book had been sent overseas illicitly and its appearance with Bouden House 博登書屋, an independent publisher specialising in non-official and emigré writing in Long Island, New York, had led to yet another round of harsh interrogations.

Burnt Ashes includes ‘July the Sixth’ 庚子,陽曆七月六日, a poem about the fateful day in 2020 on which Xu Zhangrun was detained by the Beijing authorities, a period of incarceration that marked his ‘rebirth’ as a Former Person, someone who, like Jifeng, exists in China’s Shadowland, a parallel realm of surveillance and social death hidden in plain sight. Neither of them is either fully incorporated in nor definitively eliminated from the domain of the party-state. As Xu Zhangrun observes of a condition in which he is caught in a Yin-Yang world 陰陽兩界, betwixt and between:

This, too, is life of a sort, one in which

I pay my respects to eternity’s imperfect future tense

依舊活在一種生活方式裡

向永恆未完成的時態禮讚

***

As we have previously noted, Former People, Бывшие люди (Byvshiye lyudi) is the title of a novella by Maxim Gorky published in 1897. Known in English translation as Creatures That Once Were Men, Gorky’s story would inspire Russia’s Bolsheviks to employ the term ‘Former People’ when referring to members of the defunct ancien regime who survived into the Soviet era. Their number included members of the aristocracy, the clergy, the Tsarist military and bureaucracy. As individuals whom the progress of history had cast aside, Former People were treated as ‘has-beens’ in every regard.

The Chinese Communist Party’s regime of political apartheid was engineered by Mao Zedong and his supporters from the late 1930s. Wang Ming, a former leader and head of the so-called Twenty-eight Bolsheviks Stalinist faction, became the leading Former Person during Mao’s ascendancy. After 1949, a pervasive system of class classification and Stalino-Maoist ideology imposted a form of nationwide political apartheid that was, for decades, also hereditary.

Shortly after Mao Zedong’s death in 1976, I was befriended by a number of China’s Former People. I learned about their past and followed their post-Mao careers as many of them gradually became members of ‘The People’. Some even flourished, although a few fell foul of the authorities once more. I also got to know others who were on the way to becoming China’s new Former People (see Memory Holes, old & new). When I met up with the journalist and investigative historian Dai Qing in August 1990, after she had been jailed for her involvement in the 1989 Protest Movement, she handed me a pile of nearly fifty name cards. They were of men and women who had variously been demoted, jailed, cashiered or forced into exile after June Fourth. They were her personal address book of Former People.

Nearly three decades after Dai Qing handed me that wad of name cards, Xu Zhangrun entered that Yin-Yang world, one that exists in spectral parallel with and stark contrast to China’s propaganda state. For residents in the People’s Republic, be they local or foreign, as well as for academic visitors, businesspeople, investors and so on, for the most part Former People exist in a no-go zone contact with which is to be avoided. By steering clear of these people with no-status buttresses one’s own status while reinforcing the will of the state.

***

Xi Jinping began manufacturing swathes of new Former People as soon as he ascended to power. They are predominantly Party stalwarts who have been made into Non-People by his tireless, and often spurious, anti-corruption campaign, as well as a result of his policing of ‘Red Genes’ (see Tigers Explain Tigers). There seems to be scant public sympathy for such individuals, in particular since Party members above all live with the calculated risk that they may be demoted, sidelined or purged either due to a real or perceived infraction of Byzantine regulations, or as a result of infighting, or simply for the sake of convenience.

Under Xi Jinping the ranks of Former People have swelled. Although indications point to the nation’s replacement population being in a slow decline, Former People enjoy a dolorous boom. Moreover, Former People is not merely a retrospective category. Due to the all-embracing nature of the Xi-system and the ongoing issues with gender equality, the policing of the LGBTQ+ community, ethnic sequestration and broad social reprogramming, policies aimed at potential Former People are also prospective: they extend to nascent and future generations by limiting, distorting and corrupting human potential in a vast range of areas. Party dominion claims not only the past and the present, but also the future. Its strictures stifle what was, what is and what could be.

China’s Former People and potential Former People are corralled by a system of exquisite malice.

***

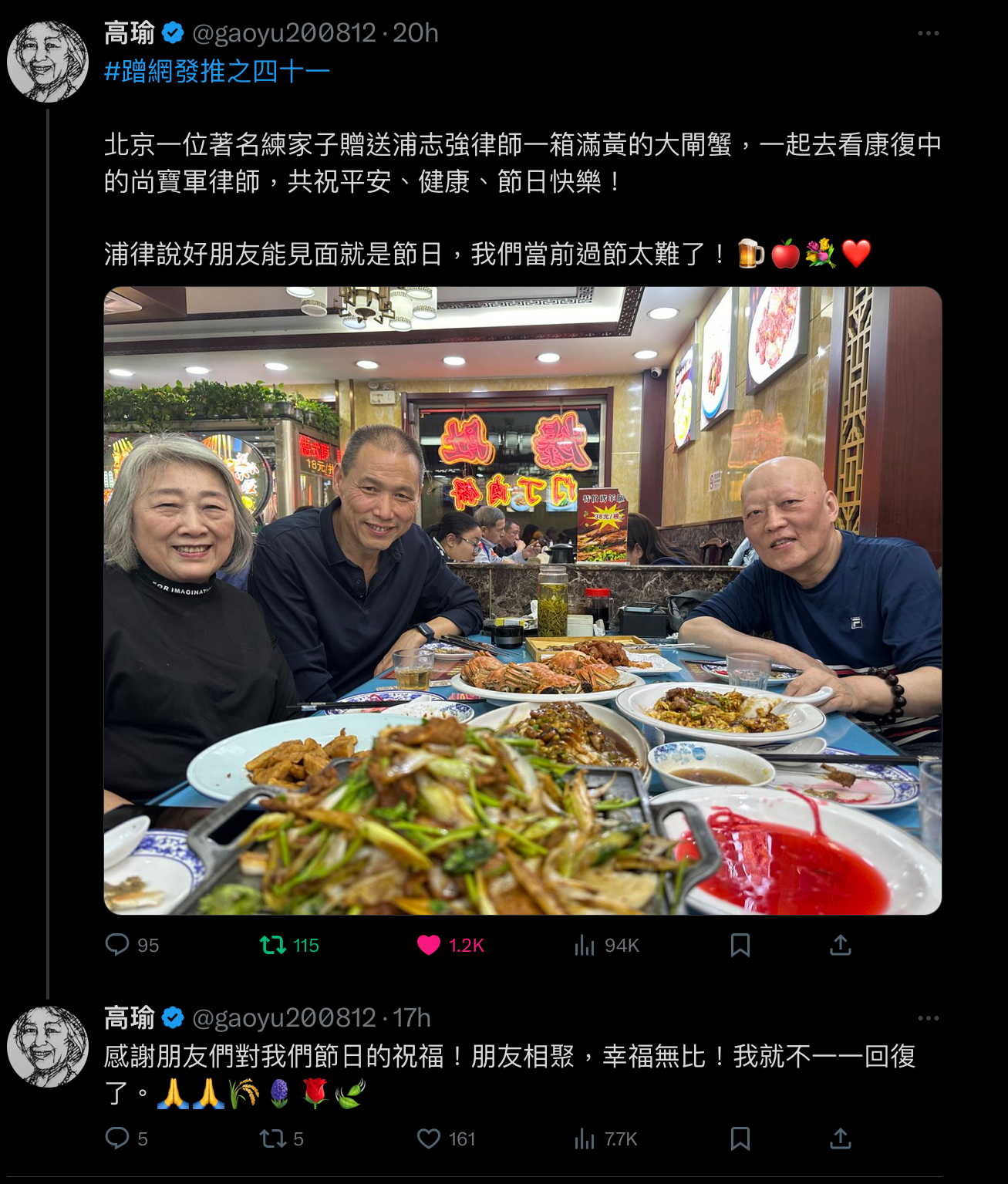

Xu Zhangrun and Jifeng were able to meet during the Mid Autumn Festival and their encounter was celebrated by Gao Yu 高瑜, an unyielding journalist and truth-teller who was long ago cast into China’s capacious memory hole. We mark that intersection of three of Beijing’s Former People on the Double Brightness Festival 重陽節 of 2024.

We introduce our topic by quoting a poem by Yang Shen of the Ming dynasty, a work that famously juxtaposes the fleeting aspirations and achievements of man with the landscape of eternity. In so doing, I compare Xu Zhangrun and Jifeng to the fisherman and woodsman in the poem whose conversation, lubricated by wine, ranges over the dramas of humanity — 古今多少事,都付笑談中. This is followed by Jifeng’s laconic account of his meeting with Professor Xu and a wistful reminiscence by Gao Yu. However, the core of the chapter is the bilingual version of Xu’s poem ‘July the Sixth’ which prompts further observations on Former People in Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium and a discussion of the significance of 被 bèi, the ‘adversative passive’ marker of contemporary Chinese life.

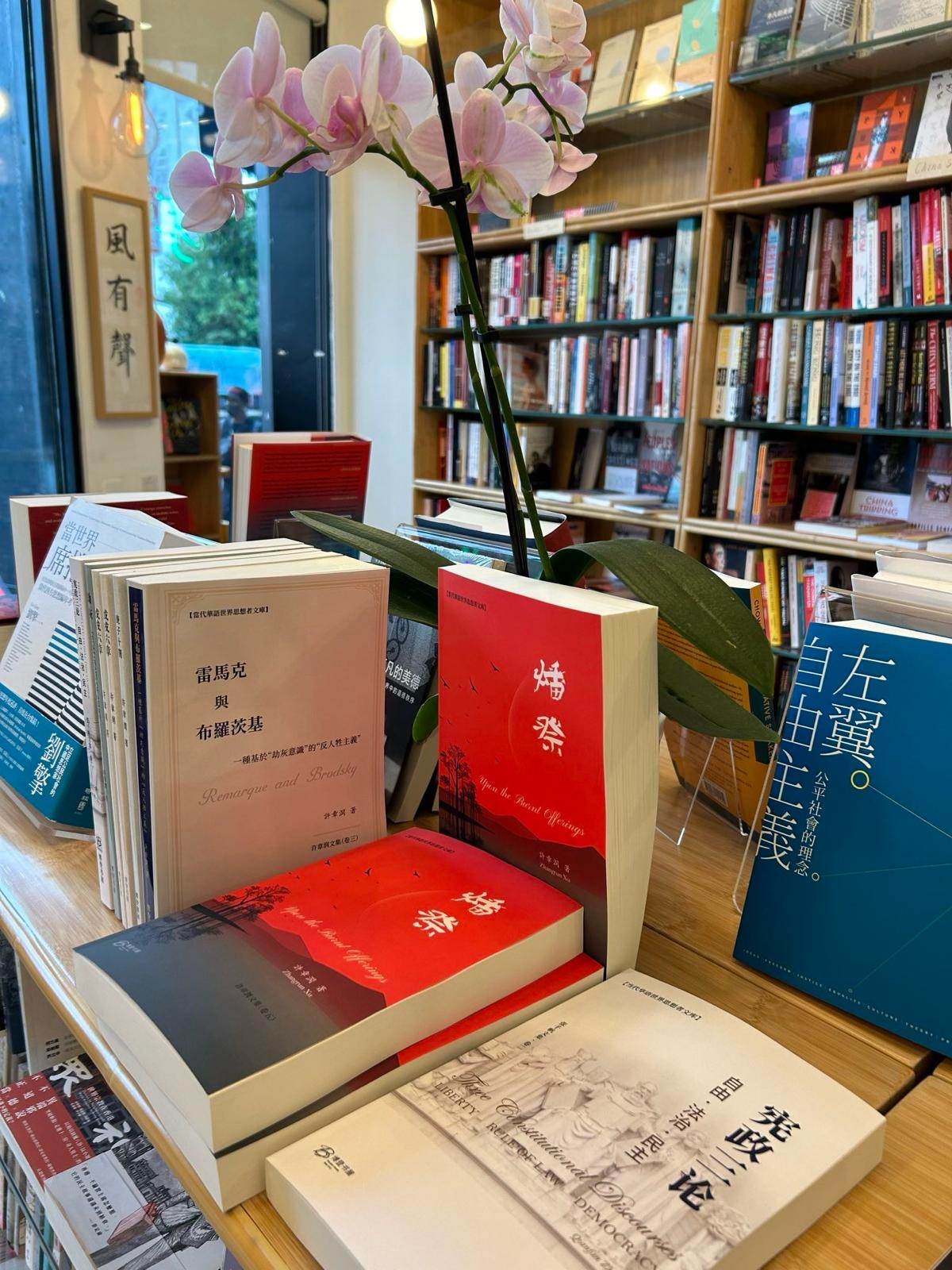

We conclude with a photograph of copies of Xu Zhangrun’s books Burnt Offerings and Remarque and Brodsky on display at JF Books 季風書園, the celebrated Shanghai bookseller that reopened at DuPont Circle in Washington, DC, in September 2024. The picture was taken by Yu Miao 于淼, the proprietor of JF Books, and supplied by David Rong 榮偉, founder of Bouden House, Professor Xu’s publisher. This is followed by a Coda in the form of a poem by Zhang Xiaoxiang of the Song dynasty.

***

Our series Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium is dedicated to Xu Zhangrun and here we recall 6 July 2020, the day on which he was effectively deemed to be ‘socially dead’ 社死 and formally assigned to the burgeoning ranks of China’s Former People. My thanks, yet again, to Reader #1 for finding the time to cast an eye over the draft of this material. The remaining infelicities and errors are mine.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

11 October 2024

甲辰年九月初九重陽節

Double Brightness Festival

Ninth Day of the Ninth Month

Jiachen Year of the Dragon

***

Further Reading:

- ∓ 加減: Xu Zhangrun on 6 July 2023, Part I of Chapter Two in Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium

- Ninth of the Ninth 重陽 Double Brightness

- Daniel Wu, A beloved bookstore, forced to close in China, is reborn in Washington, The Washington Post, 4 September 2024

- 江雪,季風再來 :一家獨立書店的沈浮 以及公民社會的中國命運,《歪腦 WHYNOT》,2024年10 月7日

A Life under Surveillance:

From the Xu Zhangrun Archive:

- Ten Letters from a Year of Plague 庚子十劄

- Xi’s China, the Handiwork of an Autocratic Roué, New York Review of Books, 9 August 2021

- The Refusal of One Decent Man, New York Review of Books, 21 August 2021

- Notre seul parapluie — ‘Life is a shitstorm, in which art is our only umbrella.’

- In My Words — a poem by Xu Zhangrun, 1 August 2022

- Xu Zhangrun at Sixty

Contents

(click on a section title to scroll down)

Immortal at the River

Yang Shen 楊慎

臨江仙·滾滾長江東逝水

滾滾長江東逝水,浪花淘盡英雄。

是非成敗轉頭空。

青山依舊在,幾度夕陽紅。

白髮漁樵江渚上,慣看秋月春風。

一壺濁酒喜相逢。

古今多少事,都付笑談中。

On and on the Great River rolls, bending east away.

Of proud and gallant heroes its white-tops leave no trace,

As right and wrong, pride and fall turn all at once unreal.

Yet ever the green hills stay

To blaze in the west-waning day.

Fishers and woodsmen comb the river isles.

White-crowned, they’ve seen enough of spring and autumn tide

To make good company over the wine jar,

Where many a famed event

Provides their merriment.

— translated by Moss Roberts, quoted in Tired of Winning Yet, China?

The Band Slap Has Some News for You, The Other China

***

Former People form a fragile community, one of broken connections that constantly strives to eke out its half-life amidst constants threats of detention, everyday harassment, pervasive surveillance and the looming possibility of harsher punishments and even oblivion. Theirs is a brittle community forged by cruelty. It seeks fleeting fellowship in the shifting interstices created by political fiat, state opportunism and the unpredictable temperament of their wardens. Occasionally, some Former People may enjoy a moment of communion. Here we celebrate one such instance. It is a record of resilience and a eulogy to resistance.

— GRB

***

Meeting Xu Zhangrun — Mid Autumn 2024

Jifeng 季風

It’s been over a year since I had a chance to meet up with Brother Xu. Last time, in May 2023, I was only days away from being hounded out of the capital by the authorities. On that occasion I was acting on a request from Bao Tong, my revered elder. The respected artist Yan Zhengxue and I were able to deliver the Truth-teller’s Award into Xu Zhangrun’s hands.

[Note: Bao Tong 鮑彤, a prominent reformer and aide to Zhao Ziyang, the Party General Secretary ousted by Deng Xiaoping and his colleagues in a ‘soft coup’ that accompanied the remorseless violence of the Beijing Massacre on June Fourth 1989, died in Beijing on the 9th of November 2022, four days after his ninetieth birthday; Yan Zhengxue (嚴正學, 1944-2024) was a leading figure in China’s unofficial art scene and a cultural activist who was repeatedly harassed, detained and jailed by the authorities.]

Now, I was finally back in Beijing again, but things have changed: how could I have known that would be the last time I saw Old Yan. He is with us no more. I can only heave a heavy sigh of regret.

Brother Xu presented me with Burnt Offerings, a volume of poems that he was able to publish overseas. I’ll be sure to share it with friends after I have spent some time delving into it.

一年多終於又與許章潤兄相聚了,上次見面還是去年五月我被驅逐出北京之前幾天,受鮑彤老先生遺托,與嚴正學老師一道去為他頒發——影響中國真話獎。現在回京相聚,嚴老哥已經離我們而去,我們與他卻成了永訣,一聲嘆息! 章潤兄送我一本境外出他的書,是他最近一年寫的詩,待我細讀哦後再與朋友們分享。

***

Gao Yu (高瑜, 1944-) came to prominence in the post-Mao years as a principled and courageous professional journalist and editor. She has been persecuted, jailed and cruelly toyed with by the Chinese system since 1989. Throughout she has pursued her rights tirelessly and taken every opportunity to support truth-seeking and government accountability. In mid 2024, the authorities cut off her phone and internet access.

Gao Yu’s resilience is nothing less than heroic. She published the following comment beyond China’s Great Firewall with the help of a friend.

— GRB

***

To Xu Zhangrun — at a remove

Gao Yu 高瑜

Mr Xu, in this photograph you look as though you’ve lost weight, although your eyes are as penetratingly spirited as ever. It also seems as though you might be on the verge of breaking out in your characteristic boisterous laughter and that reminds me of an abiding regret: five years ago, we’d all got together in the depths of autumn to celebrate Bao Tong’s 87th birthday.[1] Some of those around the banquet table argued that they could only support the passive resistance of the protesters in Hong Kong.[2] Then, quite unexpectedly, you broke out into a full-throated and soulful rendition of a Northeastern folk song.[3] Since I was sitting next to you, and was quite taken aback, I lacked the presence of mind to record the moment on my phone. You finished your lusty rendition all too soon.

[Note: 1. On Bao Tong, see 幽 — Bao Tong — Spirit & Soul, Appendix XXII of Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium.

2. The ‘passive resistance’ were demonstrators who were in favour of ‘peaceful, rational and non-violent’ protest against Beijing’s puppet government in Hong Kong during the mass protest movement of the summer of 2019 as opposed to the ‘daring militants’ 勇武者, who were in favour of direct action, confrontation and even violent resistance. See Lee Yee 李怡, Endgame Hong Kong, 5 July 2019.

3. Xin Tian You 信天游, literally ‘Roaming through the Heavens’, is a style of folk song unique to the mountainous province of Shaanxi. These songs are famed for being heartfelt, if rough-hewn.]

Now, if it had been Professor Zhang Weiying [who is from the northeast and who has a fine singing voice], I wouldn’t have been in the least bit surprised. But you, Professor Xu are from Anhui in the south. Why, you still even have traces of a southern accent. Who’d have thought that you’d belt out a Xin Tian You song with such surprising verve?! That’s when I realised that you’re musically gifted; one of those people who can express themselves effortlessly with both melody and passion.

[Note: See, for example, Zhang Weiying 張維迎, There’s Just No Shutting You Up! — a Shaanbei Serenade in the Xu Zhangrun Archive.]

Allow me to add my warmest congratulations on the publication of your new volume of poetry and I hope that when you take a break from composing poems you will still be able to sing your heart out and vent your spleen. I’m hopeful, too, that we will be able to get together again at some point. Although we can no longer enjoy the insights of Bao Tong’s lectures, your poems and singing voice will still ring out. Next time I’ll be sure to film you and make up for the regret I’ve felt for all of these years.

許先生略顯清瘦,炯炯目光依舊,感覺他就要發出一連串豪爽的笑聲,那是他獨有的。 我抱有一大遺憾,5年了。那年深秋,咱們一起給鮑老87慶生,有人在圓桌上站起來說只能支持香港“和理非”。你忽然大聲吼出一句陝北信天遊,因為和你是鄰座,來不及掏出手機,你就吼完了,沒有記錄下那精彩萬分的一景。如果我旁邊坐的是張維迎教授,我一點不驚訝。你一個安徽人,說話還帶着南音,吼起信天遊竟那麼地道! 從那次聚會,我就知道閣下還有音樂天賦,聲情並茂,底氣十足。看到新詩集,衷心祝賀!希望寫詩之餘,能經常吼一吼,即澆塊壘,又提底氣。 我想我們終究還能歡聚一堂,再也沒有鮑彤先生的演講了,但是有你的詩和歌可以補缺。那時,你吼,我拍,了卻我這麼多年的遺憾!

— 高瑜 @gaoyu200812, #蹭網發推之三十, 19/09/2024

***

***

July the Sixth—A Burnt Offering

The following poem was composed by Xu Zhangrun, formerly a professor of jurisprudence, on the eve of 6 July 2023. On that day three years earlier, a large contingent of police and security personnel had detained him at his apartment in the far western suburbs of Beijing. His captors told him that he was being investigated for having ‘solicited prostitutes’ while on a trip to southwest China with friends the previous November.

The resulting outcry, both in China and internationally, led to Xu’s release some ten days later without charges, but not before Tsinghua University, an institution where he had previously enjoyed a prestigious and celebrated career, had cashiered him, stripped him of his pension and eliminated his presence from the campus.

Professor Xu had been under investigation since July 2018, when he had released an unsparing and detailed critique of the Xi Jinping era. For over eighteen months China’s Stasi had subjected him to rounds of interrogation and escalating threats. Although banned from teaching, carrying out research or publishing, Xu had continued to write at a furious pace and he produced a series of essays in which he investigated the historical roots of China’s contemporary predicament. He also warned that, under Xi Jinping, China was turning into a Red Empire that would threaten the global order. Some of that work has appeared in translation in the Xu Zhangrun Archive on this site.

This poem is included in Burnt Offerings 燔祭, a collection of Xu Zhangrun’s poems published in New York in late December 2023.

— GRB

***

July the Sixth

庚子,陽曆七月六日

Xu Zhangrun

許章潤

with an inadequate, albeit well-intentioned,

annotated translation by Geremie R. Barmé

July the Sixth — meaning is a buoy buffeted by the waves

carrying me into old age, proffering for now life on the verge

One

一

Fate howled stricken outside my door this summer

As countless words of my own crowded my breast —

命運在盛夏的門外哀吼,

一萬句話奔湧心頭 ——

I have read deeply until exhaustion planning to write

Words of such tender refinement as to beguile the reader.

I’d speak of how the stench of blood suffuses the stillness of night,

My daughter, near yet so far, grieve not for me.

I have filled a backpack with misfortune as I travel forth,

In stealth I write as curses rain down on me.

Rather I will say that the blue vault of the sky

Has been washed clean time and again by tears

Streams of blood have soaked countless Jiabian Ditches.

The heretic Giordano Bruno was burnt to ashes

On Campo de’ Fiori.

Have any poets, born into a Prosperous Age,

not encountered an executioner?

Corpses and severed limbs,

fires of war and prisoners —

all things that define a battlefield —

are now our lot.

想說三絕韋編,硯田待耕,

錦繡文章妝扮了繞指的溫柔。

想說夜深人靜,大地血腥,

閨女,遠方的閨女,你毋為乃父悲憂。

災難背負著行囊晝夜潛行,

更夫筆錄口述,乃受詛咒。

更想說,人族的淚水沖刷過蒼穹千遍,

血水早已沁透了無數夾邊溝。

廣場的火焰燒死了布魯諾,

生逢盛世,哪有詩人不曾遭遇劊子手。

死屍和殘肢,戰火與戰俘,

戰場上該有的自然應有盡有。

[Note: Jiabian Ditch 夾邊溝 in the deserts of Gansu province in the far north-west of China was one of the numerous labor camps where ‘anti-party elements’ were sent following the purge of 1957. Most of the inmates of The Ditch starved to death during the Great Leap Forward. Forgotten by all but a few, accounts of the nightmarish landscape were salvaged by the reportage of Yang Xianhui 楊顯惠 in 2000 and in The Ditch, a 2010 film by Wang Bin 王兵. It also features in Sparks: China’s Underground Historians and their Battle for the Future, a book by Ian Johnson published in 2023. Giordano Bruno (1548-1600), a mystic and early cosmologist, was condemned by The Inquisition and burned at the stake at Campo de’ Fiori in Rome. Prosperous Age 盛世 is an ancient expression revived in the new millennium to celebrate China’s hard-won political stability and economic exuberance.]

— There’s only one thing left to say:

‘So, you’re here. Finally.

I’ve sat waiting so long!

Let’s go then, you and I.’

—— 結果,只說了一句話:

“哦,你們終於來了,

走吧,吾坐等已久!”

Two

二

I know I’ve been judged and sentenced,

Though I have no idea for how long.

On that night in May, my locked door gave way.

‘Wipe off the shouted spit covering your face’

I silently recited the poetry in my heart.

我知道已然被俘,但不知具體刑期。

惡月,那一夜,門鎖嘩啦。

“揩著啐到臉上的一聲聲喝斥”,

我默然溫習心中的詩。

There was a small opening near the ceiling, for air,

though the moon, stars and words could not get in.

A naked light on the ceiling, blinding, dumb yet incessant.

None of us could stretch out, packed in, backs crippled

By morning light, sleepy limbs scattered on the floor.

牆頂一扇通風的小窗,不見星月與字。

天花板的長明燈晃眼,乏味而茫然。

擺不成大字,於是傋僂,身體挨著身體,

一覺天明,地鋪安頓了疲乏的四肢。

They have a grammar and logic all their own.

Wordless, a silent culture, they are in on the game.

A sacrifice to understanding history’s unfeeling ways

My life added to the pile, an offering for tomorrow.

他們有自己的語法和邏輯。

無語,辭在文野,早明白其間的把戲。

今古之變的胎盤連通向天人之際,

我將自己的命搭上,為接生明天獻祭。

Three

三

The Sixth of July in the Year of the Dog —

I was reborn, from a sacrificial offering on an exquisite altar

Detention set me on a course to join a broader humanity

After my lustration, I would share the embrace of a different fellowship

七月六日,歲在庚子

我重生於一場優美的獻祭

因為囚禁,從此奔向了全人類

人類用泯於眾人將我緬懷

Time extends to infinity even as its limits crowd upon us

There is no miracle on the horizon; even the sun grows haggard

From 6 July 2020, every dawn ushers in worshipful commemoration, farewell

My sojourn has led to Voronezh, any day could be my last

時間因太過遼闊而逼窄

平原沒有奇蹟,太陽愈見老邁

生日後的每一天都是祭日

七月六日,我的沃羅涅日

[Note: ‘Voronezh’ 沃羅涅日 refers to Voronezh Notebooks composed by Osip Mandelstam (1891-1938) during the last years of his exile and shortly before his death. Anna Akhmatova visited the Mandelstams in Voronezh and wrote: ‘But in the room of the poet in disgrace/ Fear and the Muse keep watch by turns./ And the night comes on/ That knows no dawn.’]

There is no shame in being unarmed

Our lot has always been to cultivate mulberry and pick ferns

Even so, the Earth continues its course despite Their Rules

Arrogant prison bars cannot prevent the sun shining or rain falling

On July the Sixth, those ancient ashes are born to us on the wind

無需為手無寸鐵而羞愧

種桑採薇,地球從不服從圓規

傲慢的鐵柵也得承受雨淋日曬

七月六日,天空飄過遠古的灰

[Note: ‘Pick ferns’ 採薇 is a reference to the Han-dynasty Grand Historian Sima Qian’s biography of Boyi and Shuqi, China’s earliest ‘dissidents’, in which he records that the brothers ‘found refuge at Shouyang Mountain, fed off ferns rather than eat the unrighteous millet of the Kingdom of Zhou and starved to death’ 義不食周粟,隱於首陽山,採薇而食之,及餓且死。’Ancient ashes’ 遠古的灰 are the result of the conflagrations of history. See Words of Gratitude, Elegies of Anger, 23 January 2023.]

The echos in the empty valley resound, belonging to none

July the Sixth, humanity itself now the kin of flowing waters

My soul sighs to the Mountains and Rivers in a secret language:

I have lived and now death, too — the desolate reality for all beings

空谷觸痛的回聲沒有姓氏

七月六日,人類是流水的義子

心靈以啞語對山河秘語

我生過,我死過,眾生孤獨

Four

四

This, too, is life of a sort, one in which

I pay my respects to eternity’s imperfect future tense

The workings of the universe — in weal and bane — are mysterious

Each new sacrifice allows pause for further contemplation

依舊活在一種生活方式裡

向永恆未完成的時態禮讚

一轉頭,淨化之火家道中落

獻祭的絢爛退而屏息凝思

Worship this inebriation, drink to the lees

Calamity ever unfolds around such revelries

We accept this world amidst dark premonitions

In the age of the cynic, They turn a deaf ear to the distant thunder

崇拜微醺,也感恩深醉

形而上學在歡樂中出軌

接受世界只因預感災難將至

忿世嫉俗的時代聽不到驚雷

[Note: ‘Distant thunder’ 驚雷 is a reference to a poem by Lu Xun dated 30 May 1934, the last line of which reads 於無聲處聽驚雷, literally, ‘A startling clap of thunder is heard where silence reigns’.]

Regardless, Earth is our precious realm, not the Skies above

The End of Our History must lie in modest gestures of remembrance

An existence that has not found expression in poetry is not worthy of praise

Their grandiose claims are ultimately exercises in futility

畢竟大地比天空更加昂貴

歷史終結於死後記憶的式微

未曾化作詩句的存在不值得讚美

奮發圖強,所以無所作為

July the Sixth — meaning is a buoy buffeted by the waves

Carrying me into old age while proffering life on the verge

My speech is still my own, not their standard parole

Theirs is not my country; flames and floods encircle me

七月六日,坐標漂浮於蒼海

一步跨入老年,歲月索居邊陲

但方言的古意不理會腔圓字正

我沒有國家,烈火和洪水將我包圍

The Eighteenth Day of the Fifth Lunar Month

of the Guimao Year of the Rabbit

5 July 2023

癸卯惡月十八,二零二三年七月五日

[Note: The third and fourth sections of this poem were previously published in ‘The Sixth of July’, by Xu Zhangrun — China’s Former People, 13 July 2023, Part I of Chapter Two in Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium.]

***

Bèi 被 — Living with the Adversative Passive in Xi Jinping’s China

Xu Zhangrun is a non-entity in Xi Jinping’s China. Although a myriad of other Former People have been silenced, often as a result of harsh custodial sentences imposed on the most spurious of grounds, Xu continues to read, write and, thanks to wrinkles in the fabric of the system, his voice is also heard internationally.

However, at best Xu Zhangrun’s is a half-life, an existence spent in a shadowland of imposed passivity. The circumstances of many of China’s Former People like Xu Zhangrun can be encapsulated in a single word: 被 bèi.

As a grammatical particle or ‘preposition’ 介詞 jiècí the word 被 bèi indicates the passive mood, or the fact that something or someone is being acted upon. 被 bèi is used to express ‘the adversative passive voice’ — it denotes an individual’s lack of control, a state of unwilling subjugation or even foul play. 被 bèi indicates that a person is acted upon rather than acting.

The passive marker 被 bèi became a feature of China’s political lexicon during the Mao-Liu era (1942-1966), achieving near universality during what we think of as the decade of High Maoism (c.1964-1976). Swathes of the population, in particular the educated, having been subjected to a period of ‘brainwashing’ 被洗腦 (more formally known as ‘thinking that has been remoulded’ 思想被改造) in the early 1950s, were subsequently repeatedly ‘informed on’ 被檢舉, ‘denounced’ 被批判, ‘subjected to various forms of house arrest’ 被監禁, ‘exiled’ 被流放, ‘repressed’ 被鎮壓, ‘eliminated’ 被肅清 or simply ‘executed’ 被槍決. In the late-Mao era, select individuals were, however, ‘liberated’ 被解放 and even ‘served the state in some major capacity’ 被重用. After Mao’s death, hundreds of thousands of people who had been wronged over the decades were ‘rehabilitated’ 被平反, the bogus accusations levelled against them being overturned and their names cleared 冤案被昭雪.

Following a wave of nationwide coercion before and during the 2008 Olympic year, 被 bèi enjoyed renewed valence, so much so that in 2009 it was named the unofficial ‘character of the year’. As the Sinologist and linguist Victor Mair observed at the time:

… it has become fashionable to use the passive voice with verbs that don’t normally allow it and in situations that seem ludicrous. One of the most celebrated examples is bèi zìshā 被自殺 (“be suicided”), with the implication that someone was beaten to death, but the authorities made it look as though he had committed suicide. Once coined, bèi zìshā spread like wildfire, so that it wasn’t long before it merited its own entry in online dictionaries and encyclopedias.

— Suicided: the adversative passive as a form of active resistance, Language Log, 24 March 2010

Writing in The New Yorker in late 2018, Jianying Zha, an astute observer of Chinese repression and the foibles it entails, noted other common uses of 被 bèi:

… “to be touristed” [被旅遊 bèi lǚyóu] … is one of those sly inventions favored by Chinese netizens: whenever law enforcement frames people, or otherwise conscripts them into an activity, the prefix bei is used to indicate the passive tense. Hence: bei loushui (to be tax-evaded), bei zisha (to be suicided), bei piaochang (to be johned), and so on. In the past few years, the bei list has been growing longer, the acts more imaginative and colorful. “To be touristed” is no doubt the most appealing of these scenarios, and it is available only to a select number of troublemakers. In Beijing, perhaps dozens of people a year are whisked off on these exotic trips, typically diehard dissidents who have served time and are on the radar of Western human-rights organizations and media outlets. Outside the capital, the list includes not just activists but also petitioners (fangmin [訪民])—ordinary people from rural villages or small towns who travel to voice their grievances to high government officials about local malfeasances they have suffered from.

Later, in the same article, Zha comments that bei lüyou is also a symptom of China’s malaise:

The scheme would seem to be the brainchild of someone who, alert to how lavishly the state will spend on all security-related affairs, figured out a way to creep through the back entrance of the great government banquet hall to join the feeding frenzy in the kitchen. The aim of bei lüyou was plainly to pamper diehard dissidents enough to soften their defiant spirit, but it could also serve as a morale-booster among the rank and file of the security forces. For them, it’s essentially a free vacation that counts as work. In Mandarin, this is called a meichai, a beautiful duty. Jianguo was taken on four such trips between October of 2017 and September of 2018, providing almost a dozen meichai slots for the police. The officers varied as much as the itineraries, and I imagined them haggling over the rotation of these coveted slots. Perks must be shared. Once, Jianguo told me why an elderly policeman was assigned to his team for a trip south: the man was about to retire, and he’d never been to any tropical beaches.

— Jianying Zha, China’s Bizarre Program to Keep Activists in Check, The New Yorker, 17 December 2018

***

***

China’s Stasi first popularised the practice of ‘being touristed’ during the 1990s when Beijing was currying favour with the international community and foreign investors while still at pains to contain, and cosmetically disguise, political dissent. Throughout the Xi Jinping era, China’s lexicon of adversative passive terms has been considerably enriched. The following is a shortlist of commonplace terms used to describe some of injustices and indignities to which Former People are constantly subjected, from the mild to the menacing:

- 被喝茶: to be ‘invited to have a tea’. An informal kind of regularised intimidation as well as being a way of extracting information, be it from Former People or from individuals identified as potential sources or informants;

- 被禁言: to be silenced — unable to express one’s views, publicly or online. To be censored;

- 被竊聽: to be ‘eavesdropped on’, that is to be monitored at home, or when meeting friends etc, via electronic or other means;

- 被跟蹤: ‘to be followed’, is the routine use of minders or plains-clothes operatives to follow an individual as part of ongoing efforts to gather information on their activities and contacts. It is also a form of low-level intimidation. The agents involved act in a manner that can be covert, overt, or simply clownishly clumsy;

- 被囚禁: to be imprisoned;

- 被熬鷹: to be subject to sleep deprivation, as a form of torment/ torture;

- 被留用: ‘to be kept on’, a problematic person who is still of some use to the system remains employed, possibly at a lower rank, although on a short leash. It is similar to 被冷處理, ‘kept on ice’, and not nearly as serious as 被打入冷宮, ‘to be cast into a cold palace [like an unwanted concubine]’. However, the party-state is unwilling to discard ‘useful materials’ 可用之材料 or 人才. As Mao himself observed of Deng Xiaoping, a twice-recycled Party leader ‘人才難得’.

- 被控制使用: ‘to utilise a person’s talents while keeping them under close observation’. Long before the Xi era, the suite of policies developed by the Communists to infiltrate and eventually subjugate businesses and individuals was summed up as a Sixteen-character Strategy: 降级安排,控制使用,就地消化,逐步淘汰 (‘Sideline politically unreliable people while continuing to utilise [their talents] under strict supervision. Absorb them locally with the aim of gradual elimination’). This succinct guidance, one applied for decades in dealing with everything from the business community to academics and technocrats, remains relevant when approaching Xi Jinping’s China, and in particular Hong Kong, China’s ‘fallen city’

- 被監視居住: ‘residential surveillance’, or house arrest;

- 被監控: ‘to under surveillance’, that is to be listened in on, have guards stationed in or at one’s home, in the neighbourhood and to have one’s activities restricted;

- 被站崗: to have police, security or plainclothes officers posted outside one’s apartment on politically sensitive occasions. They can simply be keeping an eye on the ‘mark’, although their job can also be to report on, intimidate or harass visitors;

- 被切斷: ‘to be cut off’ from the outside world by cutting off phone lines, any connection to the internet and even mobile phone service;

- 被邊控: ‘to be border controlled’, that is prevented from leaving the country. In some cases Former People are not even allowed to leave the place of residence, suburb, town or city. For years, Xu Zhangrun was banned from leaving Beijing and he is still forbidden from travelling overseas. Others have been refused permission to travel to Hong Kong, which is Chinese territory. In many cases, travel to ‘hot spots’ like Tibet and Xinjiang is also restricted or forbidden;

- 被驅離: ‘to be expelled’ (from a place, residence or city) or ‘to be forcibly removed’ and sent to a place of exile in the same country;

- 被驅逐: ‘to be expelled’ or sent into exile from one’s homeland or a country. In the Xi era, as the leverage of foreign governments has waned, the expulsion of dissidents and troublemakers is less common, although there have been a number of high-profile cases involving Chinese people with foreign citizenship, as well as foreigners, who have been expelled;

- 被百般騷擾, or 被刁難: terms covering irksome, pettifogging harassment. This can take many forms, including restrictions on social media accounts, online shopping or access to all forms of e-commerce;

- 被污名化: to be defamed, stigmatised, or to have one’s reputation sullied. There are many ways in which this can be achieved: through malicious gossip and rumour; to be used as a ‘negative teaching example’, or to be made into an object lesson used by the authorities to warn others against error in word, thought or deed;

- 被除名: damnatio memoriæ, the obliteration of a person’s existence. In the case of Xu Zhangrun this has included a blanket ban on his name on the firewalled internet, the removal of his books and publications from libraries and a ban on the sale of his books either online or in bookstores. He was recently told that a strip of white paper has been placed on his face in the formal faculty photograph in the corridor of Tsinghua Law School, where he had worked for decades;

- 被下崗、被離職: ‘to be dis-employed’, that is, dismissed from a job;

- 被雙規: ‘to be subject to internal Party discipline’, which rarely ends well. In fact it may lead to:

- 被開除: ‘to be expelled’ from a state job or the Communist Party; or,

- 被雙開: ‘to be twice-fold expelled’, that is to be fired from a government job, losing thereby all perks and benefits, and ejected from the Communist Party itself.

- On and on the great river rolls …

Other verbs with both positive and negative connotations used with the passive marker 被 bèi are:

盜,落(là,因為跟不上而被丟在後邊),盤(轉讓),擠,罰,裁(裁員),拍(拍攝),禁,列入,發現,罰下,蒙騙,哄騙,把玩,巡視,利用,提及,執行,審查,取消,認定,暫停,拿來,移送,判處,稱為,處罰,信仰、遵守,刷屏,封殺,代表,禁止,約見,視察,抽調,視為,免職,責令,譽為,喚醒,灌輸,壓抑,認同,溺寵,賦予,忽悠,設立,查禁,放任,打破,轉發,洗劫,吐槽,尊稱,環繞,超越,評為,認為,找到,殖民,擠佔,鎖定,指控,肢解,追責,監管,平反,羈押,關牛棚,繩之以黨紀國法,強制醫療,記過、記大過或降級,約談和督辦,認同和踐行,移送審查起訴,誤讀、誤解、誤會。

— 刁晏斌,當代漢語 “遭” 字句的特點及其與 “被” 字句的差異, Global Chinese, Issue 4, 2016.]

On 1 October 2024, Gao Yu described being subjected to the state’s adversative passive approach in personal terms:

On the 75th anniversary of the People’s Republic, I am completely cut off: I cannot call anyone on my phone, send text messages, watch TV, shop online, hail a taxi, use any scanning device, or be validated by any scanner… And 18 months ago I was permanently banned from communicating with chat groups of friends and others on WeChat. I can’t even communicate with individuals.

75年,我第一次過了一個完全被屏蔽的“十一”。不能打電話、不能發短信、不能看電視、不能網購、不能打車。不能掃碼、不能接受驗證碼…。微信朋友圈、群聊被永遠禁止,私聊已經封了一年半。

Gao’s electronic sequestration also meant that the eighty-year old was also unable to make doctor’s appointments or visit a hospital to seek treatment for various health issues. (She posted the message above on Twitter/ X with the help of a friend, just as she marked her celebration of 10 October 2024 with Pu Zhiqiang and Shang Baojun by means of ‘online freeloading’ 蹭網發推。

***

Once an individual has fallen foul of the system, the party-state continues to police the words-thoughts-deeds of habitual troublemakers and although a goal of the Xi Jinping era is for existing and potential Former People to be silenced 被禁言 bèi jìn yán, the activities of of figures like Xu Zhangrun, Jifeng, Gao Yu and Pu Zhiqiang prove that the system not quite so draconian. Censorship 禁言 jìn yán is an endlessly flexible category, in particular since people may be silenced for shorter or longer periods, online and offline. Jianying Zha masterfully describes the rolling censorship to which her brother, Jianguo, is subjected while others are deprived silenced altogether.

Former People, an amorphous group subjected to 被 bèi, ‘being acted upon’, enjoys neither individuality or personal dignity. Apart from the Leader, Xi Jinping, anyone in China or anyone deemed to be ‘Chinese’, can be relegated to the status of Former Person.

At JF Books

DuPont Circle, Washington, D.C.

***

For the background of JF Books, see:

- Daniel Wu, A beloved bookstore, forced to close in China, is reborn in Washington, The Washington Post, 4 September 2024; and,

- 江雪,季風再來 :一家獨立書店的沈浮 以及公民社會的中國命運,《歪腦 WHYNOT》,2024年10月7日

***

Coda: 問看百姓知公否

鷓鴣天

張孝祥

晝得游嬉夜得眠。

農桑欲遍楚山川。

問看百姓知公否,

餘子紛紛定不然。

思主眷,酌民言。

與民稱壽拜公前。

只將心與天通處,

合住人間五百年。