Introducing Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium

瞽

The title of this introductory essay — ‘You Should Look Back’ — is a reference to ‘Don’t Look Up’, a film directed by Adam McKay that was released in December 2021. Our recasting of ‘Don’t Look Up’, a metaphor for ignoring the obvious, as ‘You Should Look Back’ is a reference both to the fact that the scale and heft of China’s ideocracy has been in clear view from the earliest days of the post-Mao era (1978-) and how purblindness and obduracy allowed people to misconstrue the obvious well after Xi Jinping’s rise to power in late 2012.

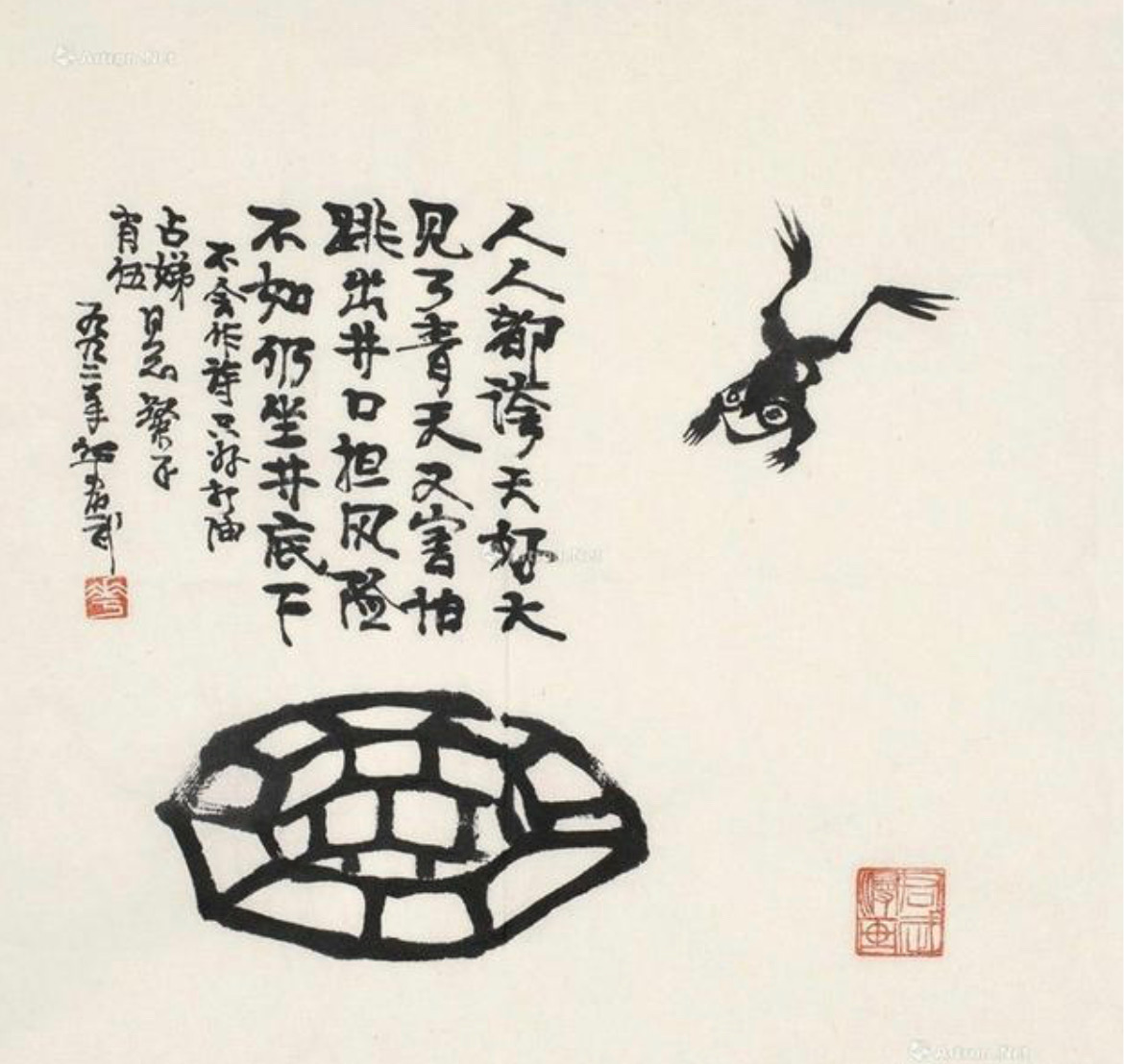

The Chinese rubric of this introduction is 瞽 gǔ, ‘cecity’ or ‘blindness’:

‘The blind can’t see intricate visible patterns, nor can the deaf hear music. But blindness and deafness are not only physical conditions.’

瞽者無以與乎文章之觀,聾者無以與乎鐘鼓之聲。豈唯形骸有聾盲哉。

— Zhuangzi, ‘Wandering Freely’

莊子, 《逍遥游》

The title Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium is explained in ‘Ξ — The Xi Variant’, below.

***

Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium builds on the five-part series Homo Xinesis and extends the argument made in The Fog of Words, The Right to Know & the Need to Lampoon, and Prelude to a Restoration. ‘You Should Look Back’ follows on from a prologue titled The True Face of Mount Lu and an illustrated proem, Winking Owl, a Volant Dragon & the Tiger’s Arse.

The chapters in this series are arranged in the style of what old-school propagandists condemned as ‘reactionary editorial layout’ 反動編排. That is, our running commentary on contemporary events is interwoven with historical analogy and work from the past; this is further punctuated by juxtaposed translations and quoted texts that in turn are highlighted by illustrative material. We build on an editorial method that was originally essayed in the books Seeds of Fire: Chinese voices of conscience (1986, 2nd ed. 1988), New Ghosts, Old Dreams: Chinese rebel voices (1992) and Shades of Mao: the posthumous cult of the Great Leader (1996). It was further developed in the virtual pages of the e-journal China Heritage Quarterly (2005-2012), as well as in the China Story Yearbook series (2012, 2013, 2014). It is the preferred editorial approach of China Heritage, one that emphasis what we have long called New Sinology, and it features in particular in Readings in New Sinology and Hong Kong Apostasy, two other sections in China Heritage.

This series and its predecessors offer an extended commentary on contemporary China; they are also a personal meditation cum memoir related to the wonder and perplexity elicited by a lifelong involvement with that country, its peoples and their cultures. In the process we reflect on how a grand and vastly populous nation-civilisation that enjoys both global reach and significance has, under Xi Jinping and his aging Red Guard generation, been reduced to a pusillanimous scale. Official China has been whittled down to the size of the ego of the Sole Leader, 一尊 yī zūn, and the circumscribed vision of the Chinese Communist Party. Vibrant Other Chinas, however, flourish regardless.

No matter how grandiloquent the claims or bombastic the pronouncements issuing out of Beijing, a dolorous reality is undeniable: as the country enjoys levels of wealth and achievement unique in the history of the People’s Republic, a cabal of Party leaders and their intellectual courtiers assert that it is their prerogative to determine and define what China is, what being Chinese means (and can mean), as well as what the legitimate aspirations, languages, thoughts and the state of being of all Chinese peoples should be.

For those who live in a global Chinese world long nurtured by the riches of Taiwan and Hong Kong, a Mainland revived during the decades of economic reform and the creativity of a plethora of Chinese diasporic communities, this imprisoning of the Chinese mind is a tragedy of immense proportions — it is a human disaster that a clutch of rigid, nay-saying bureaucrats thus holds sway, and that it arrogates to itself the power to legislate and police the borders of what by all rights should be a cacophonous multiverse of Chinese possibility. By imposing an educational regime that, to quote Xi Jinping, ‘grabs them in the cradle’, by creating a censorious media monolith that spews forth a carefully curated ‘China Story’ and by pursuing a ‘chilly war’ internationally with the encouragement of battalions of online vigilantes, the Chinese Communist Party continues to terraform China and attempt to create and maintain a monotone landscape. All of this is aided and abetted by a sharp-edged new phase in a century-long contestation with the United States and the Western world. Although Xi Jinping’s enterprise builds on the twisted legacy of the Mao era and the darkest aspirations of the Deng-Jiang-Hu reform decades, it is obvious that his Empire of Tedium is also the handiwork of willing multitudes who travail at the behest of one man and the party-state-army that he and his cohort dominates.

***

In February 2022 on the eve of the Beijing Winter Olympics we are reminded of China’s Olympic year in 2008.

The internationally celebrated artist Cai Guo-Qiang (蔡國強, 1957-) was the General Designer for Visual Effects of the Olympic Ceremonies and his ‘footsteps of history’ 歷史的足跡 heralded the opening of the Beijing Games on 8 August 2008 with a dramatic flourish. At the time, Cai observed that: ‘Our country has become more open, so we have to be more open ourselves. We are living under this system, if there is something wrong with the state then there is something wrong with all of us, you can’t only put the onus on the Other….’ He went on to sum up the dilemmas that both the nation’s creators and its political leaders faced at the time:

‘If artists do something good they get all the credit for their creativity. If they fail then people blame interference from the leadership and the system. I think that’s a dilemma that can’t continue as it is. The country needs you to change, but you also need to change it, and you have to transform the leadership.’

— from China’s Flat Earth: History and 8 August 2008,

The China Quarterly, 197, March 2009

Xi Jinping was deputised by the Party’s ruling Politburo to oversee the management of the Beijing games and it was the first time that he showed his hand on both the national and the international level. He did so first by turning what should have been a routine Olympic Torch Relay designed to extoll the global unity of athletes and olympic nations into a heavy-handed nationalistic statement and ideological contest (see ‘Torching the Relay’, China Beat, 4 May 2008, as well as ‘The Torchbearer’, Danwei, 7 April 2008). After that, the laudable organisation of the games, the prowess of the Chinese state and the popular enthusiasm of Chinese people were all too often diminished by shrill propaganda, brute policing and chest-thumping. The year nonetheless ended with a civic apogee independent of the party-state when a group of concerned citizens released Charter 08 on 10 December, the sixtieth anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The official response to what was a modest call for more open and responsive government was harsh: signatories were interrogated and issued warnings, and Liu Xiaobo, a leading rights activist, was detained and persecuted. He would die in confinement in July 2017.

China’s 2008 Olympic Year proved to be as unforgiving as its predecessors: 1989, when a nationwide protest movement was crushed; and, 1999, when the Falungong religious sect was outlawed and the country’s struggling civil sphere penalised (see China’s Promise, China Beat, 10 January 2010). By 2010, what I thought of as ‘the closing of the Chinese mind’, a process of renewed ideological control and surveillance was well underway. At a conference on the topic of China’s ‘red legacies’ held at Harvard University’s Fairbank Center that year, I spoke about the evident threat of red revivalism (see Red Allure & The Crimson Blindfold). In the conclusion of my presentation I said that:

The Maoist or red legacy is no cutesy epiphenomenon worthy simply of a cultural studies’ or po-mo “reading”, but rather it constitutes a body of linguistic and intellectual practices that are profoundly ingrained in institutional behaviour and the bricks and mortar of scholastic and cultural legitimization. It is a living legacy the spectre of which continues to hover over Chinese intellectual life, be it for weal or for bane.

Less than a year later, in March 2011, Wu Bangguo 吳邦國, Chairman of the National People’s Congress, reiterated that unwavering Communist Party rule had created the ‘China Model’, one that rejected Western-style politics wholesale. He summed up the difference between the West and China as ‘The Five Things We Won’t Do’ 五不搞. There would be no: privatization of the economy; multi-party electoral politics; parliamentary rule; the separation of powers between a legislature, an executive, and a independent judiciary; and, no to cultural and ideological pluralism. Behind the scenes, one could sense that a major course correction, what I would later dub a ‘restoration’ was on the way. Soon, under Xi Jinping, ‘The Five Things’ would metastasise into ‘The Seven Unspeakables’ 七不講.

***

For all of the successes of the Xi Jinping decade, its egregious failures and limitations, be they in the realms of economics, social management, politics, health, education, thought, culture, international relations, do nothing so much as elicit Schadenfreude. Every misstep of this rigid and arrogant leadership elicits applause, each policy failure is cheered, every embarrassment becomes a source of celebration. This is a grotesque state of affairs: even things that by all rights should be greeted with universal acclaim are at best grudgingly acknowledged and at worst dismissed as a sham or a PR ploy. For all of Xi Jinping’s blather about win-win policies, many members of the international community regard their dealings with the People’s Republic of China as a zero-sum game.

As we noted earlier, the past decade has seen the vast scale of China increasingly reduced to the pigmy-size dimensions of a man derided by many Chinese as ‘Emperor Do It My Way’ 指明帝 (see Xi the Exterminator & the Perfection of Covid Wisdom). Deng Xiaoping was hailed as the ‘Grand Engineer of Reform’ 改革開放和現代化建設總設計師, Xi Jinping, however, is mocked as the ‘Architect of Acceleration’ 總加速師, that is as a man whose policies have dramatically reversed the trajectory of the nation, a leader whose ambitions could well precipitate systemic failure, if not collapse. Meanwhile, his supporters, whose number is legion, hail Xi Jinping for accelerating China’s march towards regional power, global standing and unprecedented achievement.

In Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium we register our distaste, disagreement and protest.

— Geremie R. Barmé, Editor, China Heritage

Distinguished Fellow, The Asia Society

1 February 2022, First Day of the First Month

Renyin Year of the Tiger

壬寅虎年正月初一

- The draft of this essay was completed on 18 January 2022, the thirtieth anniversary of the first day of Deng Xiaoping’s 1992 Tour of the South. For the significance of Deng’s tour then as well as in 2012, see Prelude to a Restoration: Xi Jinping, Deng Xiaoping, Chen Yun & the Spectre of Mao Zedong (China Heritage, 20 September 2021). My thanks to Reader #1 for commenting on the draft and pointing out egregious errors

***

Dedication

In compiling this dyspeptic commemoration of the beginning of the end of Xi Jinping’s decade as head of China’s party-state-army our aim is to bear witness. Through essays, commentary, translation, art and reprints we keep vigil with the dead and celebrate the living. We commemorate the memory of departed friends and mentors; we celebrate those who would break free of the cycles of autocratic tedium; we express our admiration for those who resist the blandishments that reward compliance; and, we offer a malediction for those who would stifle minds and twist souls.

Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium is dedicated to Professor Xu Zhangrun 許章潤, formerly of Tsinghua University. In working with Professor Xu since August 2018 I have followed in real time the fate of a man of conscience and integrity who has been silenced and persecuted, his life’s work abnegated, his reputation sullied by indifference and his achievements expunged from the record. In the process, Xu Zhangrun’s supporters have been harassed, silenced, persecuted and jailed. The torment of Professor Xu mirrors a similar plight suffered by countless others, both in the past and today. His predicament — that of a man methodically ground down for having spoken out in good faith — confronts me every day with sombre memories of friends, colleagues and mentors whose intellectual pursuits, political aspirations, artistic expression and everyday activities were benighted by the deadening hand of autocracy. Their lives have shaped my own.

Readers of China Heritage will know that the twelve months from November 1978 to October 1979 had a deep impact on my understanding of post-Mao China. Living and working in Hong Kong at the time, and frequently visiting Beijing, my insights into unfolding events were guided in particular by Lee Yee 李怡 and Liang Liyi 梁麗儀, as well as by Simon Leys (Pierre Ryckmans). Three decades later, Chan Koon-chung’s 2009 depiction of the ‘harmonious China’ that was engineered after June Fourth 1989 chimed with my own sense of foreboding. Looking back, those three landmark years — 1979, 1989, 2009 — were but milestones on the journey into Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium.

Contents

Click on a title to scroll down:

***

If You’d Just Looked Back

We have previously observed that the autocratic style of Deng Xiaoping, Chen Yun and the other members of the Eight Elders 八老 — the sodality of Party stalwarts who emerged triumphant after Mao’s death — directly contributed not only to the rise of Xi Jinping, but also fed both Xi’s political vision and his grand ambitions. A measure of systemic political reform in the 1980s, or even later, might have meant that Deng and his colleagues really could lead the Chinese Communist Party to ‘break free of the cycle’ of history, including the eternal return of autocracy, about which Mao had spoken with such confidence in 1944 (for more on this, see here). Instead, the Party’s rulers have remained captive to a system that, while strikingly innovative in some regards, replicates key fatal flaws.

We would also remind readers that Deng-Chen-era policies predicted: the limits of economic and market reforms; how far China could free itself from cold war ideas and rhetoric; the eventual betrayal of Hong Kong; ongoing repression in Tibet; the promotion of a monolithic account of China’s ‘spiritual civilisation’; the intensification of patriotic education; the nation’s regional geopolitical ambitions; the deep-seated disdain for a global order predicated on Euramerican power; as well as the nurturing of anti-foreign zealots. In 2012, these were all part of the inheritance of Xi Jinping. Moreover, it was possible, even then, to anticipate what might well unfold under his tutelage, if only you’d just looked back.

By looking back, you would have:

- Learned about the Communist Party’s carefully tended historical narrative, in particular regarding the October Revolution of 1917, the Versailles Conference of 1919 and the May Fourth demonstrations of 1919. For over a century, these events have underpinned the Party’s view of the systemic clash between both imperialism versus national independence and the capitalist and socialist systems. This dual-faceted struggle is of titanic proportions has framed Party thinking since the 1930s, and it continue to do so today

- Been aware of the discussion about the ‘Spiritual East’ versus the ‘Materialist West’ articulated in Liang Qichao’s 1920 meditation on post-WWI Europe. The ‘clash of civilisations’ had been at the heart of the modernising debate since the 1860s and was summed up in the view that success would be assured if Western knowhow was melded with China’s peerless cultural essence that was defined by an autocratic elite

- Had a passing knowledge of the pre-1949 history and ideological background to the Chinese Communist Party, its ongoing contest with the Nationalist Party over the geopolitical territory of China, its history and its varied civilisation

- Been familiar with the Party leader Liu Shaoqi’s 1939 lecture, ‘How to be a Good Communist’, a landmark work that demonstrated how Stalinist ideology could be melded with State Confucian thought, which itself incorporated Legalism, as part of the Sinification of Marxism

- Appreciated that the Yan’an Rectification of the early 1940s directed by Mao, Liu and their ideologues Hu Qiaomu and Deng Liqun became the model for the political, intellectual and cultural restructuring of China after 1949

- Studied the first decade of Communist Party rule in China (1949-1959), since from 1978 Deng Xiaoping and his comrades affirmed the significance, unassailable achievements and exemplary nature of the practices of those years

- Known that in the late 1950s Mao reformulated that century-long East-West clash when he declared that ‘The East Wind Prevails Over the West Wind’ 東風壓倒西風 confident that the historically superior and progressive socialist system would be victorious over its capitalist enemies. In early 2021, in summing up China’s successes, in particular its management of the COVID-19 pandemic, was promoted as further evidence that ‘The East is Rising, The West is in Decline’ 東昇西降. (Even the sobering events of early 2022, in particular in regard to the Omicron crisis in Shanghai, failed to staunch the septic flood of words.)

- Read and taken seriously Mao Zedong’s analyses of China’s modern history and its post-1949 policies. The core aspects of Mao Zedong Thought were not negated by the Party’s post-1976 re-evaluation of him and it continued to underwrite Chinese political life

- Paid closer attention to the events of 1979 (see below) and treated the speeches of Party leaders and their ideologues seriously rather than dismissing them as convoluted and self-serving propaganda

- Understood that the ‘three-seven’ evaluation 三七開 of Mao Zedong by Deng and his colleagues — that is, that Mao was seventy percent in the right and only thirty percent in the wrong — echoed Mao’s own statements from the early 1960s when he too had called for Party cadres to ‘liberate their thinking’

- Not only noted the wave of rehabilitations of wronged individuals and groups from the 1970s into the mid 1980s, but also followed the renovation of the security bureaucracy and its civilian counterparts. The mechanisms of surveillance and control, variously known as the dictatorship of the proletariat, of the working class, or the dictatorship of the masses 群眾專政, was the bedrock of the party-state and with each popular outburst or major incident from the late 1970s they enjoyed ever-larger budget allocations. The techno-surveillance state of Xi Jinping, after all, is built on the Party’s ninety-year-old system of secret personnel files, workplace invigilation and neighbourhood policing

- Traced the course of ideological repression in 1981, 1983, 1987 and appreciated that these purges were motivated by a holistic and well-thought-out if malleable worldview that was debated, refined and re-calibrated over decades. The purges of 1981 and 1983 in particular eliminated liberal-minded Party thinkers at the time promoted a humanistic interpretation of Marxism that tentatively offered theoretical justifications for substantive political, media and legal reform of the Chinese system

- Followed Party thinkers like Hu Qiaomu and Deng Liqun (as well as Chen Boda, from the 1940s to 1971) who, having risen to prominence in the Yan’an era of the 1940s, ensured ideological continuity between the variants of Communist Party autocracy (discussed in ‘Ξ —The Xi Variant’ below)

- Treated seriously the discussions surrounding the Primary Stage of Socialism. First advanced by Mao in the 1950s, this capacious concept is just as important in the Xi Jinping era

- Followed the efforts of both official and unofficial historians and journalists to challenge the Party’s dominant narrative, in particular the work of semi-independent writers like Dai Qing in the 1980s and the efforts of the editors of Yanhuang Chunqiu from 2001 to 2016

- Taken note, really taken note, of the upshot of June Fourth 1989 and Deng Xiaoping’s dire warnings about ‘peaceful evolution’ and his use of cold war rhetoric. The rift over the events of 1989 evoked the history of China-US relations from 1948 to 1978 and it has played a significant role in China’s ideocracy ever since (see Back When the Sino-US Cold War Began)

- Understood how market reforms form the early 1980s facilitated the rise of commercial nationalism and the zealotry that is now such a major part of Chinese life both in, and outside, the People’s Republic

- Appreciated the geopolitical, ideological and historical threat posed by the transition towards democracy in Taiwan from the 1980s and understood that Taiwan constitutes an existential threat to China

- Studied the Counter Reform of 1989-1992 and not merely dismissed it as short-lived revanchism

- Been aware of how Chinese thinkers, in particular Party thinkers, analyse and critique the hypocrisy of the Western powers in relation to a raft of issues from democracy, free speech (think Julian Assange), indigenous issues, minority rights and economic inequality

- Appreciated that in his 1992 Tour of the South Deng Xiaoping imposed a ceasefire in the ideological battle between market reformers and statist conservatives. Deng declared that the ceasefire should last twenty years. It ended in 2012

- Been more heedful of the rising tide of anti-Western populism from the early 1990s and that ever since then China’s Young Turks have taken advantage of the Zeitgeist and the commercial opportunities that it represented

- Better appreciated the political and social significance of the posthumous mass cult of Mao Zedong from 1989 to 1993

- Followed more closely the Party’s obsession with the background to and the process of the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the unravelling of the Soviet empire

- Realised that policy swings between ‘relaxation’ 放 and ‘restraint’ 收 were never merely theatrical

- Seen how aspects of nascent civil society and rights activism were increasingly corralled from the late 1990s onwards, in particular following the purge of the Falungong sect, and how the Party’s methods of control evolved accordingly

- Been historically aware and understood that during the Jiang Zemin era of the 1990s the long-contested legacies of the Qing empire were being reconsidered and a near-century of post-imperial transformation was nearing completion, a process reflected in cultural and historical works as well as the dramatic imperial-style reorientation of the capital Beijing (for more on this, see Translatio Imperii Sinici)

- Remembered that the post-1989 China-West rift widened significantly following the NATO/ US bombing of the Chinese embassy in Belgrade in 1999, something that contributed significantly to the belief that ‘the West’, led by the United States, was determined to keep China from realising its full potential on the international stage (this despite the fact that the US and others welcomed China joining the WTO in 2001)

- Seen the farrago of Sino-US mass media hype for being what it was, a cartoon version of reality (see Conflicting Caricatures)

- Paid closer attention to the warnings about ‘the state sector advancing while the private sector retreated’ 國進民退 from around 2002

- Looked beyond the surface of successful cultural works like the films of Zhang Yimou (especially ‘Hero’), the art of Cai Guo-Qiang and popular literature to see that much of it also affirmed and often extolled autocracy, offering in the process a mytho-poetic validation of the party-state

- Been able to appreciate that rampant global corporate capitalism acted as both an inspiration and a warning to China’s power-holders

- Read the essays that Xi Jinping published from 2003 to 2007 when he was Party Secretary of Zhejiang province

- Had enough historical awareness to recognise the significance of the Qing History Project, the most munificent state-funded academic project of the People’s Republic (see China’s Prosperous Age)

- Been aware that the rising tensions among the technocrats who managed the economy, the hi-tech and the creative industries existed against a backdrop of Party ideology, the proponents of which were increasingly alarmed by ideological desuetude and the growth of alternative centres of social authority and power that threatened to undermine further Party control

- Paid attention to the stridency of the Anti-CNN group that appeared during the March 2008 uprising in Tibetan China and what it potentially meant for the future, building as it did on the rabid populist nationalism of the ‘China Can Say No’ Young Turks of the 1990s

- Taken better note of how Beijing dealt with protests during the Olympic Torch Relay (March-August 2008) and been aware that Xi Jinping had oversight of the Olympics. This was the first time that his management style, vision and rigidity were on display for all to see

- Appreciated the significance of the 2008 ‘Pacific Beijing Action’ 平安北京行動 which employed a citywide security network that melded militias, local police, village government and urban street committees, as well as vigilantes (precursors of the ‘Chaoyang Masses’ 朝陽群眾), that was akin to a full-suite revival of the ‘mass dictatorship’ surveillance system of the Mao era, in particular the 1963 Maple Bridge Model 楓橋經驗 that enamoured Xi Jinping from 2003

- Read the work of statist and pseudo-Marxist intellectuals who were increasingly vocal from the late 1990s and increasingly so from before the Beijing Olympics and after the Global Financial Crisis

- Been wary of the sunny claims of bureaucrats and liberal thinkers who believed that substantive reformist or even constitutional changes were underway prior to 2012 and seen Premier Wen Jiabao’s disingenuous liberal posturing for what it was: craven showmanship

- Understood the resonances in China of the ‘colour revolutions’ that developed in the backwash of the dissolution of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s. For the Party these populist uprisings intensified anxieties about a potential replay of the Hungarian uprising of 1956, the ‘peaceful evolution’ policies of the United States from the late 1950s (and the renewed obsession with them by Beijing from the 1980s), as well as the fears of Party leaders who had seen echos of the Red Guard rebellion in the mass protests of 1989

- Been far more cautious about thinking that consumerism and the rise of a middle class would necessarily turn comrade-subjects into anti-Party civilians

- Avoid the inviting traps of techno-utopia and the myths about the liberating potential of the digital revolution and the Internet while undervaluing the resilience of a tech-savvy security state

- Been self-aware and avoided addiction to ‘China Hopioids’, the prevalence of which fueled dubious international (and some Chinese) beliefs related to the presumed direction China would take economically, socially and politically

- Appreciated with due seriousness the debates surrounding liberalism and constitutionalism from the Aughts, but kept an eye on groups like the Children of Yan’an and their apocalyptic warnings about threats to the Party’s enterprise during Hu Jintao’s second term in office

- Understood mounting popular frustration with oligopoly — party factional oligarchs, as well as business and military elites — which ruled China under the collective leadership of the Party’s Politburo

- Understood the importance attached to reining in corrupt practices at key inflection points during the 1950s, the early Cultural Revolution years, in 1979-1981 and again in 1989

- Known that when people spoke of Hu Jintao’s China being like ‘the Late Qing era’ 晚清 they were alarmed that the country was dealing with a profound systemic crisis exacerbated by factionalism, corruption and free-wheeling entrepreneurs

- Taken seriously the speeches Xi Jinping made and the actions he took from late 2012 through 2013 which revealed his ambition to become China’s party-state-army Chairman of Everything

Readers of China Heritage will be familiar with my cautions about ‘looking back’, which date to the early 1980s. My thinking was guided in particular by my years in Hong Kong where I worked with Lee Yee 李怡, editor of the Seventies Monthly. Lao Lee was a member of the local ‘red gentry’ who became a leading independent writer and commentator. His split with the Party-controlled ‘leftist’ establishment in the British crown colony, something that began in the late 1970s and continued into the early 1980s, allowed me to appreciate the inner workings of the early reform era, along with the machinations of the Party’s united front work department. (This features in Chapter Two of Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium, the two sections of which are 迴 The Tyranny of Chinese History; and, 旋 The Lugubrious Merry-go-round of Chinese Politics.)

In ‘If You’d Just Looked Back’ I merely suggest that there was abundant evidence as well as various glaring warnings about the nature, direction and aspirations of China’s ruling elites from the earliest days of the reformist phase of Communist Party rule. To recognise and follow those cues, however, meant that you had to take the Communist Party and its decades-old enterprise seriously; to treat them not as a pale oriental version of the Soviet Union, but with autochthonous significance.

Of course, those who preferred to follow Deng Xiaoping’s late-1970s injunction simply to ‘look ahead’ 向前看 can formulate an alternative list to the above, one that would feature far more upbeat indicators about China’s future. To my mind, however, this would still be something of a ‘Hopioid List’, one that has been constantly revised and updated by the boosters and hopefuls who believed that their understanding of ‘Chinese pragmatism’ and economic reality were an authoritative and legitimate guide. Over the decades, optimistic delirium has buoyed many observers, protagonists and informants within the People’s Republic itself. Elsewhere, I have dubbed the Hopioid Addicts obliged to go cold turkey during the Xi Jinping decade as ‘The Disappointed’ (see also Broken Engagement — US-China Experts in Recovery).

***

‘What people believe is essentially what they wish to believe. They cultivate illusions out of idealism—and also out of cynicism. They follow their own visions because doing so satisfies their religious cravings, and also because it is expedient. They seek beliefs that can exalt their souls, and that can fill their bellies. They believe out of generosity, and also because it serves their interests. They believe because they are stupid, and also because they are clever. Simply, they believe in order to survive. And because they need to survive, sometimes they could gladly kill whoever has the insensitivity, cruelty, and inhumanity to deny them their life-supporting lies.’

— Simon Leys, ‘The Curse of the Man Who Could See

the Little Fish at the Bottom of the Ocean’, 20 July 1989

1979, the Year of Significance

***

On 15 July 1979, American president Jimmy Carter made a televised address to the nation from the White House in Washington. He told the nation that:

‘I want to talk to you right now about a fundamental threat to American democracy.

‘I do not mean our political and civil liberties. They will endure. And I do not refer to the outward strength of America, a nation that is at peace tonight everywhere in the world, with unmatched economic power and military might.

‘The threat is nearly invisible in ordinary ways.

‘It is a crisis of confidence.

‘It is a crisis that strikes at the very heart and soul and spirit of our national will. We can see this crisis in the growing doubt about the meaning of our own lives and in the loss of a unity of purpose for our nation.

‘The erosion of our confidence in the future is threatening to destroy the social and the political fabric of America. …

‘In a nation that was proud of hard work, strong families, close-knit communities, and our faith in God, too many of us now tend to worship self-indulgence and consumption. Human identity is no longer defined by what one does, but by what one owns. But we’ve discovered that owning things and consuming things does not satisfy our longing for meaning. We’ve learned that piling up material goods cannot fill the emptiness of lives which have no confidence or purpose.

‘The symptoms of this crisis of the American spirit are all around us. For the first time in the history of our country a majority of our people believe that the next five years will be worse than the past five years. Two-thirds of our people do not even vote. The productivity of American workers is actually dropping, and the willingness of Americans to save for the future has fallen below that of all other people in the Western world. …

‘We are at a turning point in our history. There are two paths to choose. One is a path I’ve warned about tonight, the path that leads to fragmentation and self-interest. Down that road lies a mistaken idea of freedom, the right to grasp for ourselves some advantage over others. That path would be one of constant conflict between narrow interests ending in chaos and immobility. It is a certain route to failure.

‘All the traditions of our past, all the lessons of our heritage, all the promises of our future point to another path — the path of common purpose and the restoration of American values. That path leads to true freedom for our nation and ourselves. We can take the first steps down that path as we begin to solve our energy problem. …’

— from Jimmy Carter, ‘Energy and the National Goals — a Crisis of Confidence’, July 1979

Six months before he made his ‘Malaise Speech’ — an exhortation with eerie resonances today — Jimmy Carter had met with Deng Xiaoping, the de facto leader of China who visited Washington in late January 1979. Deng was the first leading Chinese dignitary to visit Washington since Mme. Chiang Kai-shek had met with President Roosevelt in February 1943. In Beijing, Deng and his comrades had been tussling with a multifaceted, Communist Party-generated malaise that threatened their rule. Only recently they had rejected Mao-era policies that had been pursued for over two decades, often with their direct involvement and even complicity, to focus their efforts on building an economy that, among other things, would emphasise the kind of heedless consumption about which Jimmy Carter was warning America.

Although the Communists were reorienting the economy they were even more focussed on reasserting the virtues of one-party rule. Within weeks of that historic meeting in Washington, a group of rowdy young people who had been publishing hand-written posters on a wall in central Beijing that called for democracy and human rights were rounded up by the authorities. Their samizdat publications were outlawed and many of them were tried and jailed for counter-revolutionary crimes.

One of the most outspoken of the detained pamphleteers was a young man by the name of Wei Jingsheng (魏京生, 1950-). Openly critical of the new style of Chinese autocracy already evident under Deng Xiaoping he called for substantive political reforms that would match the economic reforms being mooted by the Party. ‘The leaders of our nation must be informed that we want to take our destiny into our own hands,’ Wei wrote. ‘We want no more gods and emperors. No more saviours of any kind. We want to be masters of our own country, not modernized tools for the expansionist ambitions of dictators.’

He also declared that:

‘Dissent may not always be pleasant to listen to, and it is inevitable that it will sometimes be misguided. But it is everyone’s sovereign right. Indeed, when government is seen as defective or unreasonable, criticising it is an unshakable duty. Only through the people’s criticism and supervision of the leadership can mistakes be minimised and government prevented from riding roughshod over the masses. Then, and only then, can everyone breathe freely.’

In late March, as the young activists of what had been hailed as the ‘Peking Spring’ were silenced, Deng Xiaoping summed up the nation’s political priorities in Four Cardinal Principles. Those principles remain the bedrock of the Communist Party today.

In July 1979 as Jimmy Carter enjoined his fellow countrymen and women to pursue ‘the path of common purpose and the restoration of American values’, speech writers in Beijing were already working on a major address to the nation that would mark the thirtieth anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic on the 1st of October. The speech was delivered by Marshal Ye Jianying (葉劍英, 1897-1986), the army leader who had led the Huairen Tang Coup 懷仁堂事變 against the ‘Gang of Four’ in early October 1976, and in it he appealed to a nation ravaged by decades of political folly, social anomie, economic incompetence and cultural depravity.

‘For over half a century countless martyrs have bravely sacrificed their lives to build a prosperous and mighty socialist China’, Ye declared.

‘It is an ideal that can only be brought about by our continued efforts and it is one that demands that the Party, the Army and All Chinese Peoples individually and collectively work for the sake of the Fatherland by melding our individual lives with the fate of the Fatherland itself.’

半個多世紀以來無數先烈英勇犧牲,鞠躬盡瘁,就是為了把我們的祖國建設成為一個繁榮富強的社會主義國家。這個理想必將經過我們的奮鬥變為現實。為了實現這個理想,我們希望全黨、全軍和全國各族人民,每個人都把個人的利益同祖國的利益聯繫在一起,把個人的前途同祖國的前途聯繫在一起。

— 葉劍英, ‘在慶祝中華人民共和國成立三十週年大會上的講話’, 1979年9月29日

Ye Jianying’s speech was of crucial importance for the Party as it went through a profound crisis of confidence in the wake of Mao’s death, the arrest of his Gang of Four and the ideological purge that is sweeping away decades of ‘leftist’ or High Maoist thinking. Ye’s speech was an affirmation of the mission, role and self-correcting ability of the Communist Party despite the devastation it had visited on the country.

The text of the speech had been finalised at the Fourth Plenum of the Party’s Eleventh Central Committee (the preceding Third Plenum, held in December 1978, had formally disavowed aspects of the Mao era and reoriented the Party’s efforts towards the economy). Among other things it contained a summary of the Party’s 1981 resolution regarding the history of the People’s Republic and underlined the aims, as well as the political limits, of the new economic program that was being launched. Ye reiterated the central importance of the Four Cardinal Principles and he declared that as China pursued economic development or Material Civilisation 物質文明, it proved the superiority of the socialist system over that of the capitalist West by further developing a new Spiritual Civilisation 精神文明. The concept of Spiritual Civilisation, which drew on European ideas adapted in Japan at the time of that country’s ‘civilising and open door’ 文明開化 era from the 1860s, would soon become a mainstay of Communist Party thinking and social policy (see Civilising China: China Story Yearbook 2013).

Economic development and spiritual civilisation were the dual answers to the crisis of confidence that both the Party and the nation were experiencing in the wake of Mao’s death, the arrest of his Gang of Four and the ideological purge that was sweeping away decades of ‘leftist’ or High Maoist thinking. Ye’s speech was above all an affirmation of the mission, role and self-correcting ability of the Communist Party. Material strength was crucial, but a cultural revival was just as important, and it had to be a revival that was not merely about education and the sciences, it was also about culture, athleticism, revolutionary morality and revolutionary heroes.

Shortly after Ye’s speech, a nationwide debate was sparked by the publication of a letter signed ‘Pan Xiao’ 潘曉 in the popular magazine China Youth 中國青年. Although it was subsequently revealed that, along with heavy editorial intervention, the letter, which was titled ‘Why is Life’s Path Increasingly Narrow’ 人生的路呵,怎麼越走越窄 was the work of two writers, Pan Wei 潘禕 and Huang Xiaoju 黃曉菊, its publication led to six months of national soul searching as China Youth received tens of thousands of responses from readers. The Pan Xiao letter gave voice to an identity crisis among China’s young during an era of ideological and social tumult following the collapse of canonical Maoism. ‘I turned twenty-three this year’, Pan wrote:

‘You could say that my life has only just begun, and yet all of life’s mysteries and attractions don’t appeal to me anymore. It seems like I’ve already reached the end. When I look back upon the path I’ve already taken, the road changes from red-violet into grey, from hope to disappointment. It is a path of despair. It is a river flowing from a source of selflessness and purity into a self-centered end… . Some people say that time is pushing forward, but I don’t feel a part of it. Some people say that life has meaning, but I don’t know where it is. I see few options for myself. I am so very tired.’

— adapted from Homo Xinensis

The debate surrounding the Pan Xiao letter added to the sense of urgency within the Party to balance the rapid transformation of the nation’s faltering economy with an emphasis on culture, history and thought. Throughout the 1980s, while Western ideas gain traction among students and the intelligentsia, the Communists would devote themselves to articulating and formalising policies related to spiritual civilisation. In tandem with the economic reforms of the 1980s a Party-led civilising project was focussed not only on improved civic behaviour but also on enhancing revolutionary culture, ideals and the martial spirit. Behind Ye Jianying’s talk about spiritual civilisation lay a nascent critique of ‘spiritual pollution’ and corrupting Western ideology.

In the mid 1980s, the Party leader Hu Yaobang announced a template for a spiritual civilisation that included everything from the correct, patriotic view of Chinese history to the codification of public manners and the comportment of cadres. A body of thought melded the Party’s priorities and concept of ethics with coopted aspects of Chinese culture and history and, by the 1990s, a national network of spiritual civilisation offices would help police morals while promoting what, under Xi Jinping, is known as the Confidence Doctrine, a vast and well-funded enterprise that builds on the ideas promoted by Deng Xiaoping, Ye Jianying and others from 1979.

And thus, over the twelve months from December 1978 to December 1979, the Communists made it perfectly clear that:

- The need for major economic change would always have to be balanced with Party dominance;

- The opening up to the world was in essence structural and the potential for the growth of social malaise was heeded;

- The draconian policies of the 1950s, including the mass murders of the early 1950s and the betrayal of Chinese industrialists, workers, democrats and academics, remained unassailable;

- The purge of pro-democratic and liberal thought in 1957 was reaffirmed;

- The pre-eminence of the Party and its leaders was further institutionalised;

- The need to attack bourgeois ideas related to democracy, universal suffrage and human rights was codified;

- The dangers of the West remained alarming and the historical mission of the Party as well the superiority of the socialist system were undeniable;

- The urgency of ideological and cultural policies in support of Party primacy and its historical vision dating back to the nineteenth century was recognised; and,

- The promotion of the cult of martyrs and martial heroes was revived.

Ξ — The Xi Variant

***

‘I am Alpha and Omega, the beginning and the end, the first and the last.’

— Revelation, 12:13

Xi Jinping Thought is Modern Chinese Marxism; it is Marxism for the Twenty-first Century; it is the Quintessence of Chinese Culture and the China Spirit; it is a Major New Advancement in the Sinification of Marxism… That Xi Jinping has been established as the Core Leader of Party Central and the fact that His Thought is the guiding light of our enterprise together reflect the heartfelt desire of all the peoples of China, they are also of decisive significance for the further development of our Party-State and crucial for the next historical phase of China’s national revitalisation. …

習近平新時代中國特色社會主義思想是當代中國馬克思主義、二十一世紀馬克思主義,是中華文化和中國精神的時代精華,實現了馬克思主義中國化新的飛躍。黨確立習近平同志黨中央的核心、全黨的核心地位,確立習近平新時代中國特色社會主義思想的指導地位,反映了全黨全軍全國各族人民共同心願,對新時代黨和國家事業發展、對推進中華民族偉大復興歷史進程具有決定性意義。

Although our Party-State has enjoyed major successes since the initiation of the Economic Reform and Open Door Policies [from the late 1970s], thereby building firm foundations and positive conditions for the onward development of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics in the present age [of Xi Jinping], the Party has long been aware that challenging external conditions have confronted us with new risks and demands at the same time as forcing us to deal with a series of seemingly intractable problems and contradictions thrown up decades of reform. Of particular significance was the fact that [prior to the advent of Xi Jinping] widespread corruption flourished due to systemic negligence and a failure to suitably police and manage the Party. Added to this was the fact that overall political control had deteriorated to such an extent that it was damaging the healthy relationship between the Party and the Masses as well as between Party Cadres and the Masses. All of these things were undermining the creativity, cohesiveness and fighting spirit of Our Party. As a result, we have had to face a major test in our ability to effectively manage our own affairs and efficiently rule the nation.

改革開放以後,黨和國家事業取得重大成就,為新時代發展中國特色社會主義事業奠定了堅實基礎、創造了有利條件。同時,黨清醒認識到,外部環境變化帶來許多新的風險挑戰,國內改革發展穩定面臨不少長期沒有解決的深層次矛盾和問題以及新出現的一些矛盾和問題,管黨治黨一度寬鬆軟帶來黨內消極腐敗現象蔓延、政治生態出現嚴重問題,黨群乾群關係受到損害,黨的創造力、凝聚力、戰鬥力受到削弱,黨治國理政面臨重大考驗。

Under Comrade Xi Jinping, Party Central … has confronted and overcome all of the major risks and challenges that have faced China heretofore. Through his leadership the Party has been able to resolve numerous outstanding matters that have long bedeviled us and, with his guidance, we have been able to successfully undertake numerous significant but long-neglected projects. In the process, the Party has achieved significant historical outcomes and further advanced China’s historically transformative processes.

以習近平同志為核心的黨中央,以偉大的歷史主動精神、巨大的政治勇氣、強烈的責任擔當,統籌國內國際兩個大局,貫徹黨的基本理論、基本路線、基本方略,統攬偉大鬥爭、偉大工程、偉大事業、偉大夢想,堅持穩中求進工作總基調,出台一系列重大方針政策,推出一系列重大舉措,推進一系列重大工作,戰勝一系列重大風險挑戰,解決了許多長期想解決而沒有解決的難題,辦成了許多過去想辦而沒有辦成的大事,推動黨和國家事業取得歷史性成就、發生歷史性變革。

— from the Third Resolution on Party History, November 2021

‘中共中央關於黨的百年奮鬥重大成就和歷史經驗的決議’

2021年11月16日 (my translation)

***

‘To put an individual’s name ahead of a pile of dogmas reminds me of something that [the former Chinese Party General Secretary] Hu Yaobang said [at the end of the Cultural Revolution as the personality cult of Mao Zedong was being dismantled]:

As soon as you create a personality cult, there is no room for democracy, no place to seek truth from facts, no hope for the liberation of thinking; what is inevitable is the restoration of feudalism. There is nothing more pernicious than this.’

何謂「習近平」?不用說了,把一個名字加入黨章放在一個教條前面,使人想到前總書記胡耀邦的話:

「一搞個人崇拜,就根本談不上甚麼民主,談不上實事求是,談不上解放思想,就必然要搞封建復辟。其為害之烈,莫此為甚。」

— Lee Yee 李怡, What’s New About Such Thinking?, China Heritage, 5 November 2017

‘The Marxism I have opposed is in no way the Marxism of Marx and Engels. Marxism’s fate has been similar to that suffered by a number of religions. With the passage of time, the revolutionary substance is quietly abandoned, while the doctrines are selectively adapted by those in power as tools to deceive and enslave.’

— Wei Jingsheng 魏京生, 1979

***

***

Since 1949, the People’s Republic has experienced a series of overlapping governance styles. They have all been autocratic; they have all been underpinned, and justified, by a highly malleable body of ideological practices. The modern modes of Chinese autocracy include the Mao-Liu Variant (1949-1964); the High Mao Variant (1964-1978); and the Deng Variant (1978-2012). The fourth and latest iteration is the Xi Variant (2012-). It is a virulent mutation that contains genetic material from all of its predecessors. It is an admix of the malignant and the benign.

The Xi Variant of modern Chinese autocracy has re-imagineered aspects of past practice while advancing an all-embracing vision. In so far as it has pursued earlier efforts to synthesise aspects of dynastic history to serve the modern party-state, the Xi Variant is above all an imperial enterprise. As has been true in the case of other empires, the empire of Xi Jinping aims to extend its interests as far as possible and its vision claims dominion over time itself — be it the present, the past or the future. Its worldview is as thorough-going as it is stifling, for it aims to enmesh every aspect of lived, thought and felt experience (for more on this, see Homo Xinensis, a China Heritage series). Although the Xi Variant dominates the People’s Republic of China, other Chinas co-exist within and alongside it. The logic of the Xi Variant would be to infect and corrupt every aspect of Chinese being; it is highly doubtful that it can do so successfully, even as the ‘Spiritual Civilisation’ regime launched by Ye Jianying in 1979 continues its ascendant. Moreover, in the ‘new era’ of Xi Jinping it is making ever more onerous claims on the Chinese soul (see Jessica Batke, ‘A Vast Network of “New Era Civilization Practice Centers” Is Beijing’s Latest Bid to Reclaim Hearts and Minds’, ChinaFile, 31 January 2022).

Over the past decade, the Xi Variant has enriched the repertoire of Chinese autocratic practice and retooled key features of the Mao-Deng variants while incorporating within itself best international practice while accommodating forward-leaning technologies. The Party’s November 2021 resolution, quoted above, details at eye-watering length (and in thirteen dense sections) how Xi Jinping Thought has and will resolve all of the vexatious issues that have long dogged China’s reforms. However, given the fact that the Xi Variant has seen both the reintroduction and further entrenchment of some of the most intractable problems of Chinese governance, that document is not so forthcoming. During the early reform era (c.1978-1989), the Communist Party reluctantly confronted and, in some cases, even attempted to address some of these endemic problems. The effort included:

Addressing the dangers of one-man rule; dealing with the threat of the unlimited tenure in power of party-state leaders; the vexatious issue of how to accommodate disagreement, and even dissent, within the ranks of the Party beyond the rickety framework of ‘democratic centralism’; the need to overhaul the rigid nomenklatura system and promote a competent managerial and technocratic stratum that was not entirely dependent on the political whims of the rulers; the ever-present issue of endemic corruption, favour seeking and the architecture of special privileges; the need to institute something approaching a rule of law in both the civil and commercial realms, one that was not subordinated to the interests of the Party or its factions; the pressure to experiment with limited democratisation and popular participation in government; moves towards greater media diversity and openness, as well as a cautious validation of fact-based investigative reporting; a market-based model for the publishing and entertainment industries partly independent of the Party’s propaganda apparatus; the transformation of education in such a manner that encouraged individual growth and not merely collective compliance; the expansion of academic freedoms and the rise of publicly engaged semi-independent thinkers and intellectuals who, among other things, could influence and even participate in the formulation of public policy; a more diverse cultural ecosystem that was increasingly welcomed on the international stage; circumscribed yet meaningful spaces allowing for greater civil participation in a manner that kept pace with the social changes ushered in by the economic reforms; ways in which business interests and consumer demands could play a meaningful role in policy making; a recognition of failed ethnic policies and fitful attempts to permit a form of guided multiculturalism; an ongoing attempt to incorporate and yet not entirely stifle the semi-independent territory of Hong Kong; and so on.

The November 2021 history resolution declared in no uncertain terms that Xi Jinping Thought was nothing less than the ‘Quintessence of Chinese Culture and the China Spirit’ 中華文化和中國精神的時代精華. Xi Jinping and Party Central, along with their 24/7 propaganda apparat, claim that Xi Jinping and His Thought can solve all of China’s problems, past, present and future. Xi Jinping has demonstrated his bureaucratic genius in extending and consolidating control over China’s party-state-army yet, for the most part, he has followed in the footsteps of his predecessors, albeit without the artful footwork or pirouetting skills either of Mao or Deng.

Regardless of the boastful claims of his predecessors that only they could free China from the cycles of history, we suggest that Xi Jinping and the Xi Variant are turning the wheel once more. In the second decade of the twenty-first century once more China is faced with some of the most intractable problems of the past, including:

A form of post-dynastic court politics involving factional power struggles and the ever-present problem of succession; endemic official corruption unrelieved by a system that claims that it can police itself; the cartels of local bureaucrats wedded to business interests and extractive policies; popular disaffection and rebelliousness; social policies that fail to address on-the-ground realities; and, a population that is infantalised by the ruling patriarchy.

While in 2022 Xi Jinping exercises control over party-state-army in the process of his ideological monotone and the monotony of his rule have turned China into an empire of tedium. Social efflorescence is stymied by a guarded and fearful bureaucracy; diversity is corralled by a sclerotic and narrow-bore approach to human potential; cultural invention is tethered to Party prerogatives and a penchant for design by committee; an invented form of Confucianism shorn of its redeeming virtues is wedded to Stalino-Maoism; old forms of surveillance and coercion have been technologically enhanced; censorship and self-censorship are commonplace; the old culture of informing flourishes; and, the media is an echo chamber resounding with the dolorous messaging and wooden language of the apparat. Repetition, dullness, safety in conformity, hollow patriotic outrage, the drone of official palaver, the predictability of routine, political performance, the elimination of difference and the flattening of the cultural and intellectual ecosystems, the humdrum slogans ticking over on constant repeat, aspirations and lives circumscribed by narrow goals and targets measured by the Party’s metrics — this is Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium.

***

In ‘Deathwatch for a Chairman’, an essay published in China Heritage shortly after it became evident that Xi Jinping might be able to enjoy ‘terminal tenure’, I observed that:

Autocrats and patriarchs share a fateful dilemma: once ensconced in power, and even as they exercise it and hold sway over their dominion, the countdown to their demise is on. In dynastic China, sycophants attempted to ward off the inevitable by hailing the emperor as ‘Lord of Ten Thousand Years’ 萬歲爺, and even in the Maoist era the agèd Chairman’s approaching death was spoken of in delicate terms such as ‘After One Hundred Years’ 百歲之後 or when ‘He Goes to Meet Marx’ 去見馬克思. The old materialist himself mocked the refrain constantly on the lips of his devotees — ‘Respectful Wishes that Chairman Mao Live for Ten-thousand Years Without End!’ 敬祝毛主席萬壽無疆. On 18 August 1966, he responded to one fervent well-wisher — Luo Xiaohai, one of the founders of the Red Guards — by scoffing: ‘Even ten-thousand long lives have a limit!’ 萬壽也有疆麼. (See footage of their encounter on Tiananmen in the documentary film Morning Sun.)

Since Xi Jinping’s rise to paramount power in 2012-2013, the Party has unabashedly declared that ‘Everything in China is under the direction of the Communist Party: party, state, army, civilian life and education, as are all points of the compass’ 黨政軍民學,東西南北中,黨是領導一切的. From 2013, we referred to Xi Jinping as China’s CoE or ‘Chairman of Everything’. With his further investiture as Leader for Life in October 2017, and given the Party’s monolithic self-vision we noted in late 2017 that, enjoying expanded investiture as head of the party-state-army, Xi Jinping was now nothing less than Chairman of Everything, Everywhere and Everyone.

Over the three decades from when he led the Communists to abandon their wartime guerrilla base in Yan’an in 1946 until his eventual demise at the age of eighty-three in 1976, Mao Zedong, China’s previous Chairman for Life, was the subject of tireless speculation: about his whereabouts, his health, his mental state and his competency. In the event, Mao’s autumnal years lasted for decades and during that time they were a constant source of rumours, gossip and flights of fancy.

The new leader’s (presently) unlimited tenure coupled with absolute titular authority means that students of China and observers of its political life will henceforth by necessity be on something of a deathwatch for Xi, as their predecessors were for Mao over four decades ago.

— from Deathwatch for a Chairman

China Heritage, 17 July 2018

It will be left to historians in China and elsewhere to wrangle over whether the rise to power of a new autocrat like Xi Jinping was inevitable. Since the early 1980s, I have argued that for all the talk of political reform, and despite various gestures in the direction of change, the Chinese party-state, one that inherited core genetic material from the dynastic past, that adapted the exogenous strains of Leninist-Stalin party culture of the Soviet Union, and was modulated by leaders like Mao Zedong, Liu Shaoqi and the Eight Elders who survived the Cultural Revolution, remained in rude good health. Over the decades, I have made the case that the failure to inoculate the nation against a baleful systemic patrimony meant that ever-new variants of autocratic behaviour would inevitably appear.

My education at Mao-era universities, where our fellow students were former Red Guards, young Party propagandists and apparatchiki, led me to appreciate the entrenched nature and relative universality of the autocratic personality type, even among those who later would dissent from the mainstream. Over the decades, I met, read, interviewed and engaged in debate with many thinkers, activists and bureaucrats who underneath the carapace of up-to-date economic or managerial palaver had a disposition that favoured a kind of all-encompassing domineering discourse along with the authoritarian and hierarchical mindset of the martinet. A culture steeped in Mao’s words, ideas, historical vision and political practices encouraged a particular kind of (mostly male) hubris. Regardless of the transformative reforms of the post-1978 decades, such hubris was enhanced by leaders who promoted all-encompassing and holistic politics. Economic success, populist nationalism, political repression and a powerful system of top-down control were thus long primed to be taken over by anyone with the guile and ambition to rule.

In Mao’s autumn years people would say that the very nature of class struggle predetermined that traitors like Lin Biao — the ‘close-comrade-in-arms’ appointed by Chairman as his successor in 1969 — would invariably appear and take advantage of the system. ‘If there hadn’t been a Lin Biao’, you were told sotto voce and ‘in confidence’ — as I was by Teacher Bi 畢老師, the cadre in charge of students from second-world countries like me, in late 1974 — ‘it was inevitable that history would have thrown up a similar schemer, a Zhang Biao, a Li Biao or even a Liu Biao.’

In 2022, fifty years since Lin Biao’s death, one was left pondering the question: if Xi Jinping hadn’t taken the stage in November 2012, was a Bo Jinping, a Zhang Jinping or even a Li Jinping really unavoidable? More to the point, when Xi Jinping himself finally ‘goes to meet Marx’, then what?

***