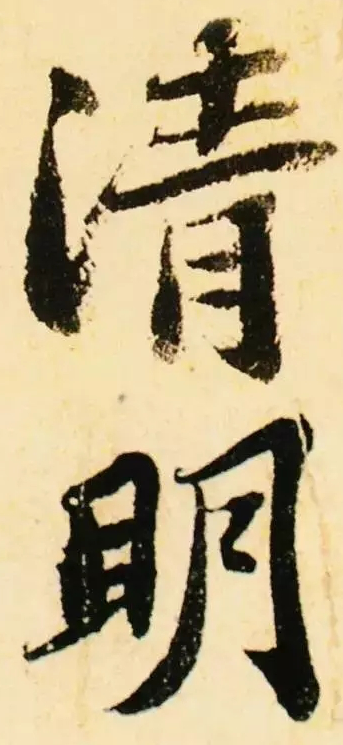

The Fifth of April 2018 marked the day for ‘sweeping the tombs’ 掃墓, a festival on which respects are paid to loved ones and forebears. Known since ancient times as Qingming 清明, ‘Clear and Bright’, it falls on the Eighth Day of the Third Month of the lunar calendar (depending on the year, according to the Gregoria Calendar, this can be the 4th, 5th or 6th day of April). Qingming comes less than a week after the Third Day of the Third Month 上已節, a time of ritual purification and seasonal celebration (see Spring Lustration). Visiting the tombs of family members and ancestral graves was an occasion both to give thanks and to take delight in the season, for that reason it is also known as the time of Spring Excursions 春遊踏青 (also 踏春).

In 2018 we mark Qingming with an essay by Lee Yee, the celebrated Hong Kong writer whose work has featured in China Heritage since 1 October 2017 (see The Best China). Here Lee commemorates his wife, Liang Liyi (梁麗儀, 1936-2008) and this essay is translated as a token of respect for a woman who was both insightful and unfailingly good-humoured. Lee Yee (Li Bingyao 李秉堯), then editor-in-chief of The Seventies Monthly 七十年代月刊, employed me as an English editor for two years from 1977 and Liang Liyi often visited the editorial department of the magazine. She would share political and personal insights honed by nearly two decades living and teaching on the Mainland. Funny, irrepressible and thoughtful, she generously contributed to our seemingly endless discussions of Chinese politics and world affairs. She also had a major influence on the political analyses that Lee Yee published under the pen-name Ch’i Hsin 齊辛. At the time Liang Liyi worked at Commercial Press 商務印書館, a Mainland-controlled enterprise with oversight covering publishing houses, magazines and printers that served both the overt ‘united front’ as well as more covert propaganda efforts of the Chinese Communist Party in the British colony. My boss, her husband, used Liang’s name — Liyi 麗儀 — as the inspiration for his main pen-name, Lee Yee 李怡. This extraordinary couple helped guide me through that bewildering period of ‘de-Maoification’ and, when I became a regular contributor to the magazine in the mid-1980s, they were a constant source of encouragement. Later, in 2005, as I formulated my ideas about New Sinology 後漢學 — that is, an understanding of modern China that is grounded in a familiarity both with the tradition and with the contending political and cultural ideas of the twentieth century — I was conscious of the formative influence of Lao Lee and Lao Liang.

***

Lee and Liang were from families with close ties to the Communist Party. They met at Heung To Middle School 香島中學, a pro-Mainland institution founded in 1946, and were married in 1960. Liang Liyi pursued tertiary studies on the Mainland while Lee Yee stayed in Hong Kong where he went into publishing. After graduating from university, Liang took a job teaching in Shenzhen. For many years the couple had what at the time was a common Mainland-style connubial arrangement living and working in different cities, only meeting on holidays or during major festivities. They maintained contact by letter, although their voluminous correspondence was destroyed in the Cultural Revolution. During those years zealots also denounced Liang for ‘treating students with a reactionary educational technique: motherly love’ 對學生進行反動母愛教育 and, before the fall of Lin Biao in 1971, she was put under investigation for having a ‘Hong Kong spy for a husband’ 香港特務老公. For a time she was placed in solitary confinement.

In 2008, Liang learned she had cancer and she passed away after only a short illness. For the first time since he began writing half century earlier, Lee Yee fell silent. He described his sense of loss in an essay titled ‘These Months’ (see 兩個多月來, 12 January 2009) and it was some time before he resumed his lifelong career as a commentator and essayist. In 2011, Lee published a collection of essays written after Liang Liyi’s, many of which touch on their relationship (see ‘In Remembrance of Letting Go’ 為了放下的記念, 17 July 2011).

***

In the following, Lee Yee tells us that he pays his respects at his wife’s grave twice a year: at Qingming 清明 in the spring and again in the autumn during the Chongyang Festival 重陽節. We describe these traditional days of remembrance in New Sinology Jottings 後漢學劄記, see: In the Shade 庇蔭 and Ninth of the Ninth 重陽 Double Brightness.

As this essay contributes to various aspects of China Heritage, it is included in Projects under New Sinology Jottings, Wairarapa Readings, as well as The Best China.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

10 April 2018

***

- For details of Lee Yee’s editing and publishing career, see here.

Not long after Liyi passed away, Lee Yee composed a memorial couplet 輓聯:

結緣逾半世紀情人妻子,終身良朋忍令天凡永隔;

牽手近一甲子說事談心,朝夕侶伴只餘舊夢縈懷。

***

My Qingming

我與清明

Lee Yee 李怡

Translated by Geremie R. Barmé

Ten years have we been parted:

The living and the dead —

Hearing no news,

Not thinking

And yet forgetting nothing!

I cannot come to your grave a thousand miles away

To converse with you and whisper my longing …

十年生死兩茫茫。

不思量,

自難忘。

千里孤墳,

無處話淒涼。……

— Su Dongpo, Jiangchengzi

translated by Lin Yutang

I was a young man when I learned Jiangchengzi, the poem Su Dongpo wrote in memory of his wife; now I’m old enough to have lived it. My wife passed away in 2008, soon — in fact, in what seems merely like the blink of eye — it’s ‘ten years have we been parted’. When I buried her ashes in Calgary, Canada, in 2009 I made an oath to visit her every spring and autumn: once on Qingming and again for Chongyang, the Festival of the Double Ninth. 「十年生死兩茫茫。不思量,自難忘。千里孤墳,無處話淒涼。……」蘇東坡懷念亡妻的詞《江城子》,我年輕時已背誦,現在則是切身感受了。妻子2008年去世,轉瞬間也將近「十年生死兩茫茫」矣。09年將她的骨灰帶到加拿大卡加里的山景墓園安葬,並立願每年清明重陽的春秋二祭都會來墓前照看她。

This year I went to the cemetery two days before Qingming. If there’s no blizzard of course I’ll be going again today. Her grave really is ‘a thousand miles away’: Calgary is over ten-thousand li from Hong Kong. My ‘longing’? With the passage of time the solitary despair I felt has diminished, although our lives together are still the stuff of my dreams. ‘Not thinking/ And yet forgetting nothing!’ — how true a sentiment. 今天是清明節,我早兩天已來過墓園,今天若沒有大風雪,當然還會再去一次。香港飛卡加里超過一萬公里,是「萬里孤墳」了。淒涼嗎?隨着歲月清洗,淒涼感坦白說已淡去,不過舊夢仍然時會縈繞。「不思量,自難忘」是確實的。

Qinging has a special significance in my life. Our daughter was born on Qing Ming (it was on the 5th of April that year). My wife and I were living apart at the time: me in Hong Kong, she was on the Mainland. We were united by a shared patriotism and unshakable socialist ideals. 清明節,在我生命中有相當特殊的意義。我的大女兒在清明節(那年是四月五日)出生。那時我與妻子分隔港陸兩地,但二人的愛國和追求社會主義理想的情懷卻是那麼一致和堅定。

After the Cultural Revolution, however, in 1976, exactly forty years ago, the Tiananmen Incident broke out in Beijing. By then we were both living in Hong Kong. Starting from the 8th of January that year — the day Premier Zhou Enlai died — we became entirely caught up in the unfolding daily drama in the north, worried that things were moving in the wrong direction. The latest news was the main topic of conversation with colleagues who worked at our respective left-wing [that is Mainland] publishing organisations. The events of 5 April 1976 — Qingming — were an even greater shock. 然後經過文革,到整整四十年前的1976年清明節,北京發生了四五天安門事件,那時我們已在香港團聚。從一月八日周恩來去世,北京每一天的動靜都牽動我們的心,憂慮着大陸局勢向我們難以接受的方向發展。每天我們分別在各自的左派出版機構與同事們議論,而四五事件更對我們的思想帶來重大衝擊。

As the year’s cascade of events continued — Mao’s death, the Tangshan Earthquake, the arrest of the Gang of Four, the end of the Cultural Revolution — the dark drama of change seemed also to offer some glimmer of hope. For me, however, the events of 5 April, Qingming, had changed my understanding of the Communist system forever. Before then I’d found ways to excuse the negative aspects of Mainland life, from Qingming 1976, and with the unfolding of later events, I could no longer avoid the realisation that unless the political system underwent a basic transformation, there was no real hope for the future. To put it another way: without systemic change no matter what new leading group came into power, or no matter what new emperor took the stage, hope was impossible, change futile. My former idealism was gone. Qingming 1976 was a turning point in my thinking, it was the start of a new phase in my life, one of constant and freewheeling questioning, it resulted in the next four decades of independent thought and free speech. She was my fellow-traveller every step of the way. 這一年發生了許多大事,毛去世,唐山地震,四人幫被捕,文革結束,中國局勢大變,似乎在黑暗中看到了希望。不過,經過四五,我對中共體制的認知,已發生了根本變化。過去,對大陸的一些陰暗面,我還會找理由去辯解,清明節及其後的事態,讓我覺悟到中國若不從政治體制上徹底改變,是不會有任何希望的。也就是說,任何對新班子、對好皇帝的希望,若沒有政治改革就都是徒然,都是虛妄。過去的理想徹底破滅。這一年清明是我思想的轉捩點,給我帶來自由思想的不停探索,以及以後四十年獨立言論的人生。她,與我同行。

Our eldest daughter lives in Calgary, our youngest lives in the United States, so it’s not too far for her to travel. The cemetery is laid out generously, and it’s peaceful; in the distance you can see snow-covered mountains, and white clouds move languorously in the blue sky. Once there, I find it hard to leave. It would be impossible to find a place like that in Hong Kong. This year our grandson, Scott [McIsaac], is over from London, on holiday from the music academy where he’s studying. Two days ago too paid his respects to his grandmother. He asked the meaning of every Chinese character on her tombstone, and wanted to know what the strips of red paper covering over my name were about. He now understands that this will also be his grandfather’s final resting place. 卡加里是長女生活的地方,幼女在美國來這裏也較近。墓園空曠幽靜,遠遠的雪山,藍天,白雲,每次來此都流連不捨。在香港真是很難找到這樣的墓地。今年外孫啟新從倫敦音樂學院回來度假,前兩天他也一起來墓園拜祭婆婆,他詳細詢問墓碑上每一個中文字的含義,以及被紅紙遮蓋着的我的名字部份。他知道這裏最終也會是他公公歸宿之地。

How long from now? Who’s to say. When she’d just gone I thought the sooner the better. I no longer think that. Earlier this year I moved house and I manage to exercise every day; a measure of regularity is returning to my life and I’m coping. Perhaps it’s because Hong Kong itself is sinking fast that I increasing feel that it is hard to let go. Or, maybe, as Lu Xun put it: you go on just so you can make life a little more uncomfortable for the people who make everybody’s lives miserable. 多久?誰知道呢?她剛走的時候,我曾想這一天來得越早越好。但現在不這麼想了。今年初搬了新居,每天做點運動,作息也漸定時,是為了繼續好好掌握活着的每一天。或許因為香港越沉淪我越感覺不能離它而去,或許如魯迅所說,為了給那些讓人過得不舒服的人製造些不舒服。

At a concert by Tat Ming Pair they projected a line from David Bowie on the screen: ‘I don’t know where I’m going from here, but I promise it won’t be boring.’ Mulling it over I know that’s how I feel too. 那天在達明演唱會,看到大屏幕引用了一句英國搖滾音樂家大衞寶兒(David Bowie)的話:「我不清楚我會從這兒往哪裏去,我只可以承擔,那一定不會是沉悶的地方。」值得細味,也有同感。

— 李怡, 我與清明, 頻果日報, 2017年4月4日

http://www.facebook.com/mrleeyee

- The full text of Su Dongpo’s Jiangchengzi:

江城子

乙卯正月二十日夜記夢

十年生死兩茫茫

不思量 自難忘

千里孤墳 無處話淒涼

縱使相逢應不識

塵滿面 鬢如霜

夜來幽夢忽還鄉

小軒窗 正梳妝

相顧無言 惟有淚千行

料得年年腸斷處

明月夜 短松岡

- In Lin Yutang’s translation:

Ten years have we been parted:

The living and the dead —

Hearing no news,

Not thinking

And yet forgetting nothing!

I cannot come to your grave a thousand miles away

To converse with you and whisper my longing;

And even if we did meet

How would you greet

My weathered face, my hair a frosty white?

Last night

I dreamed I had suddenly returned to our old home

And saw you sitting there before the familiar dressing table,

We looked at each other in silence,

With misty eyes beneath the candle light.

May we year after year

In heartbreak meet,

On the pine-crest,

In the moonlight!

— Lin Yutang, The Gay Genius

The Life and Times of Su Tungpo

New York: The John Day Company, 1947, p.72