Intersecting with Eternity

出淤泥而不染

This chapter in Intersecting with Eternity is the result of a serendipitous connection between the artist Lisa Simone and the writer Linda Jaivin, one sparked by a cartoon published by Fiona Katauskas following the US presidential election on 5 November 2024.

After Linda sent Lisa a link to Feeling Trumped by the election result? You’re not alone, a cartoon by Fiona Katauskas published in The Guardian, Lisa googled the words ‘flowers growing from shit’ and came across Beautiful things grow out of shit, an essay published by Austin Kleon in June 2018. That, in turn, revealed the old Chinese expression about how lotus flowers ‘emerge resplendent from the mud yet remain untainted’. Linda immediately recognised the reference and thought I might be interested in the ricocheting messages and cultural reverberations.

Below, we reproduce Austin Kleon’s essay, as well as a piece on lotuses in China titled ‘Pine Breeze, Wisteria Moon’ from Mastheads of China Heritage, 2016-2024.

***

***

Floating is a feeling of rootlessness, of uncertainty about the future and even the present, of pedaling in thin air.

But exile on home territory is a normal state for the independent mind, the creative artist, and the individualist. These people can feel equally alienated, foreign, and strange whether at home in their birthplace or wandering the world. … [They feel] out of step with their times and live in a state of ‘internal exile.’

This is a passage from the editorial introduction to ‘Floating’ 浮, a section in New Ghosts, Old Dreams: Chinese Rebel Voices that Linda and I published in 1992. Three decades later, I included material from ‘Floating’ in Chapter Nineteen of the series Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium, the theme of which was 熬 aó, ‘to stew’, ‘simmer’ or ‘endure’.

As America enters a dark new phase of the Trump Era decent people will be sure to find creative ways to endure; some of China’s age-old strategies for survival, many of which have reappeared since the rise of Xi Jinping in 2012, might also come in handy.

***

‘Intersecting with eternity’ — the title of a China Heritage series — is inspired by a passage in Mary Norris’s excursions into the world of Ancient Greece:

… the real world of crabby landladies and deceptive road signs would crack open and mythology would spill out. You have to pay the rent in the real world, but it’s crazy not to embrace those moments when it intersects with eternity.

— Mary Norris, Greek to Me, 2019

Intersecting with Eternity 藴藉雋永 is a mini-anthology of literary and artistic works, both past and present, that are part of the unbroken stream of human awareness and poetic self-reflection. It is a companion to The Tower of Reading and an extension of The Other China section of China Heritage.

***

My thanks to Linda Jaivin for sharing the work of Fiona Katauskas and Lisa Simone with me and inspiring this chapter in Intersecting with Eternity.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

8 November 2024

***

Our mistake was to think we could row this boat across the acid lake before the acid dissolved it.

— Rebecca Solnit, 7 November 2024

***

Also in Intersecting with Eternity:

America’s Empire of Tedium — Contra Trump 2024

- MAGADU — Kubla Khan, Xanadu & the 2024 American presidential election

- Waiting for the Barbarians in a Garbage Time of History

- Unless we ourselves are The Barbarians …

- What seeds can I plant in this muck?

- If you elect a cretin once, you’ve made a mistake. If you elect him twice, you’re the cretin.

- The Great Red Wall — A Remarkable Coalition of the Disgruntled

- A Political Monster Straight Out of Grendel

- Trump is cholera. His hate, his lies – it’s an infection that’s in the drinking water now.

- Trump Redux — Who Goes Nazi Now?

***

Disinhibition

It was not wrong to see this election as pivotal, and what America has pivoted toward is a knowing and deliberate transfer of power to a nexus of interest groups whose interests are inimical to pluralist democracy. One of them is of course Trump and his family. He will have free rein for personal vengeance against his enemies and for untrammeled self-enrichment.

Another is made up of fundamentalist Christians who will gain control of federal education and health care policies and of federal court appointments and use that control to further roll back the gains made over many decades for the rights of women, LGBTQ+ people, and people who just believe that they should be able to live their lives as they see fit. A third is the oligarchs who will be allowed to do as they see fit, whether in a free-for-all of oil and gas drilling or in already dangerous areas like social media disinformation, AI, and cryptocurrencies.

Trump’s second coming may not quite herald the end of the world, but it will hand the ship of state over to a motley crew of libertines and libertarians, control freaks and fanatics. It will stage its own spectacles of mass roundups and treason trials for the amusement of the many millions who are, it now seems abundantly clear, entertained by exhibitions of cruelty. It will be a nonstop show, its cacophonous soundtrack amplified by Elon Musk and the thriving denizens of the digital manosphere.

— Fintan O’Toole, Letting It All Hang Out, The New York Review of Books, 7 November 2024

***

After googling ‘flowers growing from shit’, Lisa Simone came across the following essay by Austin Kleon:

Beautiful things grow out of shit

Austin Kleon

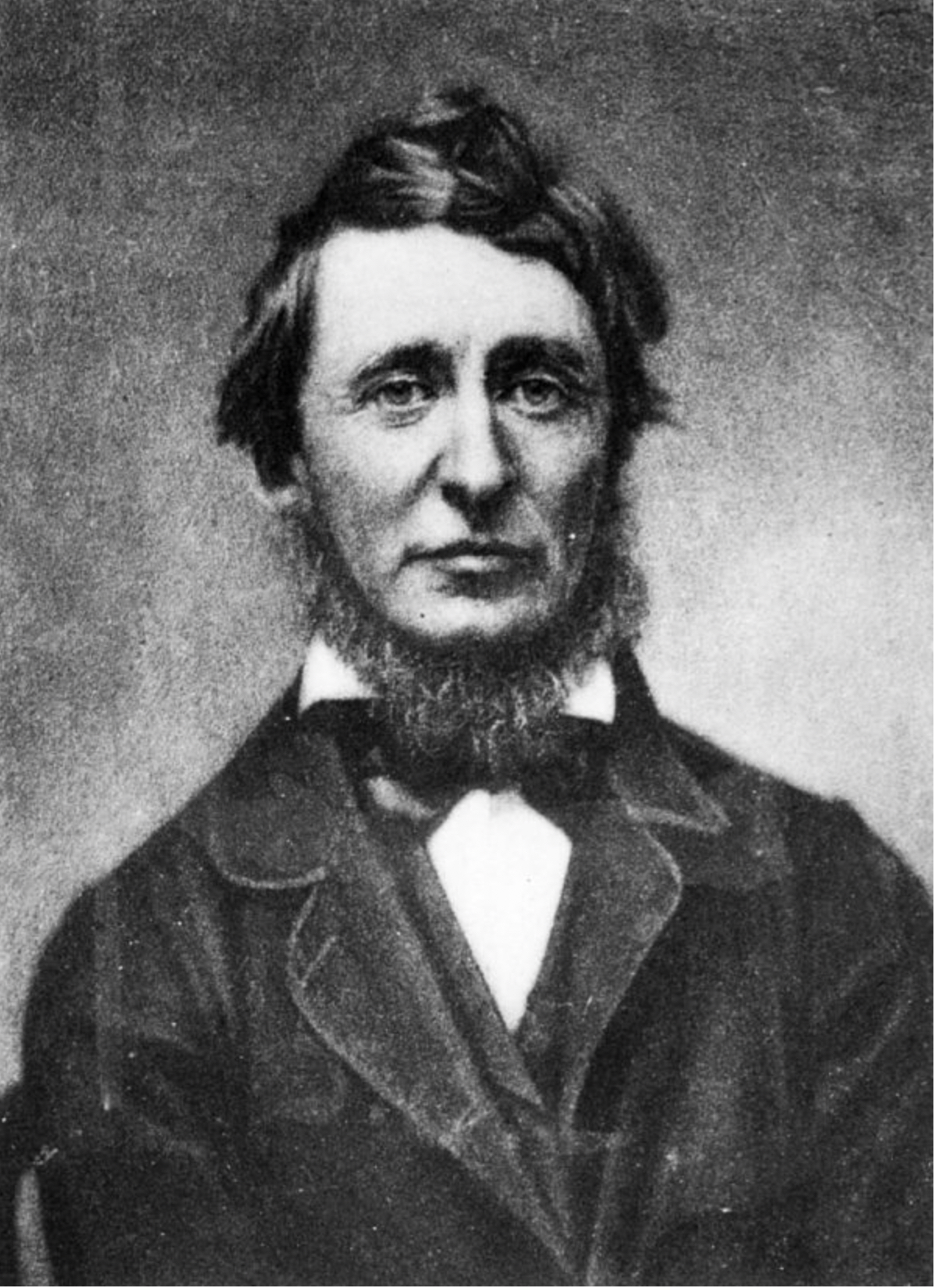

It’s Juneteenth, our government is willfully tearing children from parents, and I’m thinking of Henry David Thoreau, as I often have since reading Laura Walls’ splendid biography.

Since last October, I’ve taken up the habit of reading a page a day from his journals. It shocked me, at first, how much I enjoyed Thoreau’s company, as I had pegged him as a fussy nature-lover (I consider myself an easygoing indoorsman). He is, in many ways, just that, but so much more.

I find him completely relatable: He’s overeducated, underemployed, loves plants, is upset about politics, and lives with his parents. (Pretty sure I could write a whole sitcom reimagining him as a millennial in contemporary America.)

On my birthday, I turned to the June 16, 1854 entry, and found the raw material for what would become “Slavery in Massachussetts,” a speech he’d give a few weeks later on July 4, standing under a “black-draped, upside down American flag.” Towards the end of the speech, in an echo of his friend, Ralph Waldo Emerson (“We do not breath well. There is infamy in the air…[it] robs the landscape of beauty…”), he summarizes his despair:

Who can be serene in a country where both the rulers and the ruled are without principle? The remembrance of my country spoils my walk. My thoughts are murder to the State, and involuntarily go plotting against her.

But then, he turns back towards nature, to contemplate the water-lily. Here’s Laura Walls:

In an extraordinary final turn, he willed himself toward hope: “But it chanced the other day that I scented a white water-lily, and a season I had waited for had arrived. It is the emblem of purity.” Pure to the eye, sweet to the scent, yet rooted in “the slime and muck of earth,” the lily became his emblem for “the purity and courage” that may yet—that must yet—be born of “the sloth and vice of man, the decay of humanity” In offering his audience this American lotus flower, the sacred Buddhist emblem of enlightenment he had found lighting his path of Concord, Thoreau was offering them the core of his own being and belief, and the story of his own redemption.

It reminds me of something Brian Eno says: “Beautiful things grow out of shit.”

Beautiful things grow out of shit. Nobody ever believes that. Everyone thinks that Beethoven had his string quartets completely in his head—they somehow appeared there and formed in his head—and all he had to do was write them down and they would be manifest to the world. But what I think is so interesting, and would really be a lesson that everybody should learn, is that things come out of nothing. Things evolve out of nothing. You know, the tiniest seed in the right situation turns into the most beautiful forest. And then the most promising seed in the wrong situation turns into nothing. I think this would be important for people to understand, because it gives people confidence in their own lives to know that’s how things work.

If you walk around with the idea that there are some people who are so gifted—they have these wonderful things in their head but you’re not one of them, you’re just sort of a normal person, you could never do anything like that—then you live a different kind of life. You could have another kind of life where you could say, well, I know that things come from nothing very much, start from unpromising beginnings, and I’m an unpromising beginning, and I could start something.

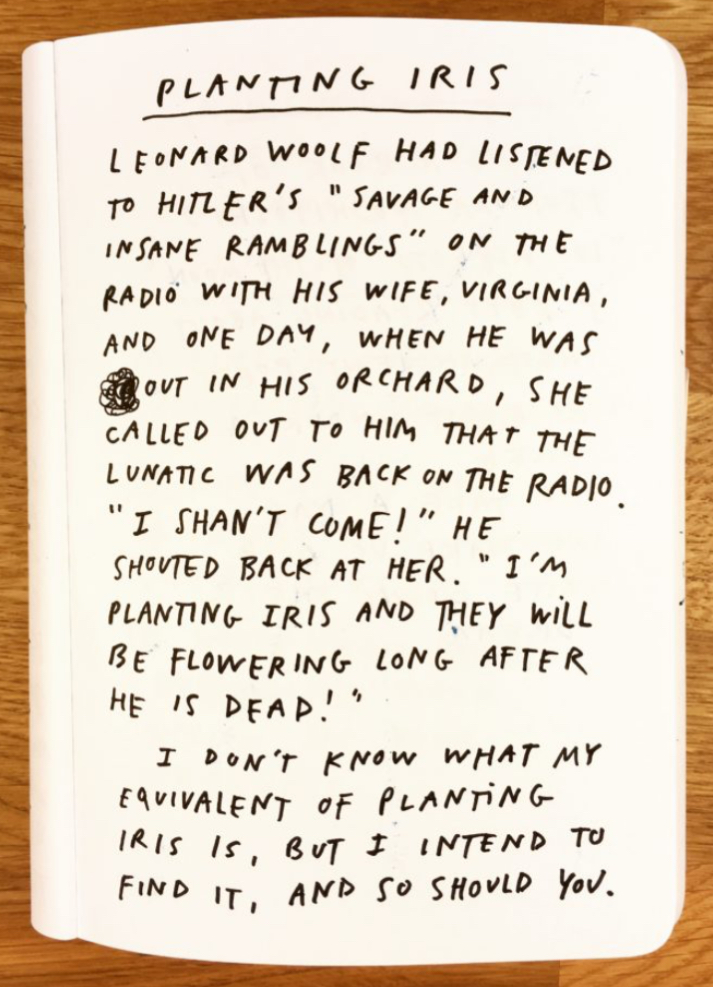

This is an unpromising beginning. What can I start? What seeds can I plant in this muck?

***

***

Source:

- Austin Kleon, Beautiful things grow out of shit, 19 June 2018

Pine Breeze, Wisteria Moon

The masthead of China Heritage in 2019 featured the following photograph, made by Lois Conner in the Garden of Perfect Brightness 圓明園, northwest Beijing:

The lakeside scene takes its name, ‘Pine Breeze, Wisteria Moon’ 松風蘿月 — ‘the wind scented by pine trees, the moon seen through a wisteria trellis’ — from a line in a poem by the Qianlong Emperor composed in 1762:

Folded hills, serene waters convey a heavenly truth

Wisteria moon, pine winds invite contemplation

屏山鏡水皆真縡,

蘿月松風合靜觀。

‘Pine Breeze, Wisteria Moon’, where a pavilion inscribed with Qianlong’s poem once stood, marks a unique location in the sprawling gardens. It is next to an intersection of the original Garden of Perfect Brightness 圓明園, to the west, the Garden of Extended Spring 長春園 to the north and the Garden of Brocade Spring 綺春園 to the south. Constructed and extended over a period of nearly 150 years, the three garden-palaces are collectively known as the ‘Garden of Perfect Brightness’. The masthead also reflects the theme of the 2019 China Heritage Annual, which was Translatio Imperii Sinici — the skein of empire in modern China.

***

***

Over the years, Lois Conner has repeatedly returned to the lotuses that still fill the lakes of Beijing in the summer months and augur the changing seasons of the capital. She thinks of them as her muse, as well as being deeply emblematic of the former imperial city and a more ephemeral, if recurring, aspect of its traditional aesthetic.

Chinese art has long treated the lotus as symbolic of transient worldly glory: resplendent one day and shorn of splendor the next. The flower has varied associations — with lithe sensuality, for example, as well as with others that no longer seem that sublime: ‘golden lotuses’ 金蓮 and ‘hooked lotuses’ 鉤蓮 are poetic terms for the disfigured stumps produced by the binding of girls’ feet in dynastic times.

Perhaps the dominant association of the aquatic nelumbo nucifera is with the Buddha. In India, where Buddhism originated, the lotus was an early symbol of sunlike power and vitality. The chakras, those whorling nodes of potential and awakening power that run along the spine of the human body, take the pictorial form of dormant or fully blossoming lotus flowers. In the heart of the blossom grows awareness, perfection. As a newborn child, Siddhartha Gautama, later the Buddha, was said to have taken seven steps on the earth from which lotuses sprang; in artistic representations, his footprint is often adorned with a lotus pattern. He, as well as myriad bodhisattvas, are most often represented seated upon or within the sacred flower in the folded-legged ‘lotus posture’. The eleventh-century writer Zhou Dunyi 周敦頤, famed for his ‘Essay on Loving Lotuses’ 愛蓮說, quotes a Buddhist line about the leaves and flowers of the aquatic plant: ‘They emerge from the mud yet remain untainted’ 出淤泥而不染. Tibetan Buddhists are constantly mindful of the significance of the lotus as they repeat the Sanskrit mantra-prayer Auṃ maṇi padme hūṃ ཨོཾ་མ་ཎི་པདྨེ་ཧཱུྃ, ‘Hail the jewel in the lotus!’ The botanist Peter Valder has written of the lotus in his magisterial work The Garden Plants of China:

The fact that seed pods, flowers, and buds are present at the same time denotes the three stages of existence — past, present, and future. The many seeds in each head suggest abundant progeny and, because its rhizomes are firmly rooted in the mud and its flowers and leaves are numerous, it is a symbol of steadfastness and prosperity in the family. And the pronunciation of the Chinese names for the plant, Lián 蓮 and Hé 荷, is the same as it is for other characters denoting continuity and peace, respectively.

In the early spring, the first leaves of the lotus pierce the surface of lakes and ponds, unfurling and floating as if not tethered. Through the summer the leaves lift above the water, growing to their full expanse and swaying, blowsy in wafts of warm air, quivering on thin stalks. By autumn the limpid sticks of the now-decayed stems, heavy with the umbrella of shriveled leaves, collapse, crumbling into calligraphic forms. Finally, the dried-out skeletons of the plants lie brittle and crushed on the water’s surface, metamorphosing into a bas-relief in mud or magnified and preserved under an icy crust during the winter months. The life cycle of the lotus provides Lois Conner with inspiration, appearing vibrant and luscious at the height of the summer season and in its autumnal, dying mien at the Garden of Perfect Brightness.

Originally, Lois Conner made her spare, calligraphic lotus studies in the southern lake city of Hangzhou, whose poetry and landscapes, both natural and built, inspired many of the imperial gardens and villas of Beijing and beyond. The seasonal contrast of the north provided the artist with another dimension of the lotus. At the Imperial Summer Lodge 避暑山莊 in Chengde, for example, she found the Kiosk for Appreciating Lotuses 觀蓮亭, a scene with a pavilion and lotus-filled lake inspired by Zhou Dunyi’s essay mentioned above. Here the lotus plant, literary tradition, and political power come together: it is said that while in residence here before the autumn hunt, the Kangxi emperor (r. 1662-1722) asked the brightest of his grandchildren, Hongli 弘曆, whether he could recite Zhou’s essay. The young boy did so with aplomb, greatly pleasing both the grandfather and his father, the future Yongzheng emperor (r. 1723-1735) and creator of the Garden of Perfect Brightness. The young boy, Hongli, would himself eventually inherit the throne and reign for nearly sixty years — as the Qianlong emperor.

— G.R. Barmé, from Beijing: Contemporary and Imperial

Princeton Architectural Press, 2014, pp.155-156

***