Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium

Chapter I

比肩

Who are those hooded hordes swarming

Over endless plains, stumbling in cracked earth

Ringed by the flat horizon

What is the city over the mountains

Cracks and reforms and bursts in the violet air

Falling towers…

— from ‘V. What the Thunder Said’

T.S. Eliot, The Waste Land, 1922

In Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium we argue that in many respects the first Xi Jinping decade (2012-2022), particularly in its most revanchist mode, was underwritten by forces that have long been at work both inside the Chinese Communist Party and in China itself. So, too, was the ‘Xi decade’ integrated with and reflective of global phenomena.

In ‘Drop Your Pants!—The Party Wants to Patriotise You All Over Again’, a series that investigated the historical dimensions of the first five years of Xi Jinping’s rule published in late 2018, we made the case that the Xi era had been a century in the making. Of particular significance were three revolutions: 1911, when the Xinhai Revolution saw the establishment of the Republic of China; the October Revolution of 1917, which led to the creation of the Soviet Union in 1922; and, the 1949 revolution that saw the Chinese Communist Party conquer mainland China and invade the former Qing-dynasty territories of Tibet and Xinjiang which had nominally been part of Republican China. Of particular interest to us here is the October Revolution of 1917.

Although the centenary of that momentous upheaval enjoyed little fanfare in Russia itself, it was nonetheless duly celebrated in China. After all, as Mao Zedong famously proclaimed in 1949, ‘the salvoes of the October Revolution brought us Marxism-Leninism’ 十月革命一聲炮響,給我們送來了馬克思列寧主義. In the reverberations of those revolutionary cannons, the Soviet Union had contributed directly to the founding of China’s People’s Republic and, rather more circuitously, to its latter-day ‘socialism with Chinese characteristics’ and the New Era of Xi Jinping itself.

***

In late 2017, and on over dozens of occasions since, Xi Jinping has repeatedly stated that ‘we are witnessing major changes unfolding in our world, something unseen in a century’ 當今世界正經歷百年未有之大變局. The earlier turbulence to which he was obliquely referring to was, of course, the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, an event that helped inspire the founding of the Chinese Party and which thereafter profoundly influenced its evolution (see ‘History as Boredom’, China Heritage, 14 November 2021). By referring to ‘changes … unseen in a century’ and evoking the epochal moment of 1917, Xi Jinping has repeatedly signalled that the time has now come for China’s Communists to upend the world in their own revolutionary ways.

For over a century China and the Soviet Union/ Russia evolved in tandem; it is a relationship that has alternated between mutually beneficial synergism and the overtly antagonistic. In the first decade of the twentieth century, both countries were grappling with the legacies of empire. In China, the Manchu-Qing dynasty had given way to a troubled republic that found itself heir to vast swathes of late-conquered imperial territory; while, in Russia, the empire of the House of Romanov dissolved and, under the Bolsheviks, was reconstituted as a Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. In the twenty-first century, the Russian Revolution continues to resonate in both polities, just as the lure of lost empire still informs many of the ideas, emotions and historical narratives beloved of the leaders and peoples of the two countries.

The founding of the Soviet Union in the wake of WWI and the Russian civil war in 1922 offered the world an alternate vision of political order, ideology, economics, society, selfhood, culture, academia and communication. It also marked the beginning of a new kind of geopolitical struggle and systemic competition with both Europe and North America. From their inception, China’s Communists were part of the fray and, apart from sharing a purge-ridden party structure with their Soviet cousins they also nurtured a vengeful culture and a ‘mytho-poetic industrial complex’ that would meld the romance of violent struggle with a messianic view of infallibility and historical inevitability.

The Cold War era was a continuation of the clash of these particular civilisations, just as the Chinese Communist war with the Nationalist Party from 1927, and by association its ongoing tussle with latter-day Western imperial and quasi-imperial powers, has always been also a contest over ideas, history and power that straddles all areas of government, economics, trade, social organisation, the media, information and education.

When China today hails its ‘amitié éternelle’ 世代友好 shìdài yǒuhǎo, or everlasting friendship, with Russia — a country László Csaba has called ‘Kuwait with nuclear weapons’ — as it did in 2021, it is celebrating a trans-generational relationship that still binds the old Soviet Union and the Chinese Communist Party, as well as the Russia Federation and the People’s Republic of China.

Today, as both China and Russia in their disparate ways challenge and white-ant the post-WWII world order, their political lives, imaginaries and motivations continue to reflect in a myriad of ways a totalitarian temper with century-old roots. That totalising temper, and the countries in its thrall, have been a ‘constituent other’ that has squared off against Euramerican ideas about empire, capitalism, as well as the post-colonial and liberal world orders. Until the recent past, many people naively believed in global convergence and in what Timothy Snyder refers to as ‘the politics of inevitability’ (for more on this, see below). The year 2022 has, however, revealed a very different kind of inevitability.

The ‘recurrent totalitarianism’ of the present era is a virulent and reactive infection and it is the subject of this first chapter of Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium.

***

The title of this essay — ‘We Need to Talk About Totalitarianism, Again’ — is a reference to We Need to Talk About Kevin, a novel by Lionel Shriver published in 2003. About a fictional school massacre and the psychopathic shooter, Kevin Khatchadourian, Shriver’s novel investigates the innate characteristics (‘bred in the bone’) of the protagonist, the influence of his childhood environment and the consequences of wrong-headed optimism.

We bracket the chapter with two excerpts from T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land; a third punctuates the argument midway through. I first read Eliot’s poem in 1971; it was my last year of high school and one year shy of the fiftieth year since The Waste Land was first published. Now, another fifty years have passed and October 2022 will mark the poem’s centenary. October 2022 is also the centenary of the March on Rome, a coup d’état that brought Benito Mussolini and his National Fascist Party to power in Italy.

My thanks, as ever, to Reader #1 for their suggestions, corrections and encouragement.

— Geremie R. Barmé, Editor, China Heritage

Distinguished Fellow, The Asia Society

31 March 2022

***

Contents

Following a personal reminiscence about the abiding Soviet influence in 1970s China, we offer a sketch of the post-Soviet Sino-Russian relationship (1991-2022) against the backdrop of the 1917 Russian Revolution and the founding of the Chinese Communist Party in 1921. We then consider the place of totalitarianism in historical discussions of China and Russia before offering a comparison of Communism and Fascism during the interwar years as formulated by the historian Norman Davies. We then suggest that, in 2022, it is time to reconsider totalising politics in the context of Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium and China’s trumpeted ‘amitié éternelle’ with the Russian Federation. The material in this chapter is divided into the following sections (click on the title section to scroll down):

***

Related Reading:

- The Threnody of Tedium, in Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium, China Heritage, 18 February 2022

- 中國外交部,中華人民共和國和俄羅斯聯邦關於深化新時代全面戰略協作夥伴關係的聯合聲明, 2023年3月22日

- A Damning Critique of Putinism and Russian Foreign Policy by Feng Yujun and Wen Longjie, Sinification, 14 March 2023

- Feng Yujun on Russian History, Culture, and Contemporary Development, Pekingnology, 15 March 2023

- Dina Khapaeva, ‘Putin Is Just Following the Manual’, The Atlantic, 27 March 2022

- Bilahari Kausikan, ‘China’s Strategic Dilemmas’, Asia Sentinel, 22 March 2022

- Li Yuan, ‘China’s Information Dark Age Could Be Russia’s Future’, The New York Times, 18 March 2022

- Anne Applebaum, ‘Why We Should Read Hannah Arendt Now’, The Atlantic, 18 March 2022

- Geremie R. Barmé, ‘Wang Jixian: A Voice from The Other China, but in Odessa’, ChinaFile, 12 March 2022; and, ‘I’ve Forgotten How to Kneel in Front of You‘, ChinaFile, 21 March 2022

- ‘袁騰飛談「俄羅斯」和中國親俄漢奸’ [Yuan Tengfei on ‘Russia’ and Pro-Russian Chinese Traitors], YouTube, 8 March 2022

- 秦暉,「趨納粹」還是「去納粹」? 烏克蘭評論之三 [Qin Hui on Ukraine (3): ‘Nazification’ or ‘De-Nazification’?], 金融時報 [Financial Times], 2022年3月8日

- Qin Hui on Ukraine (1); Qin Hui on Ukraine (2); Qin Hui, Ukraine (3), Qin Hui, Ukraine (4); Qin Hui, Ukraine (5); Qin Hui, Ukraine (6); and, Qin Hui, Ukraine (7), Reading the China Dream, March-April 2022

- Ekaterina Mishina, ‘How to establish a state ideology incognito’, The Institute of Modern Russia, 6 February 2022

- Slavo Žižek, ‘What Does Defending Europe Mean?’, Project Syndicate, 2 March 2022

- Geremie R. Barmé, ‘The Fog of Words: Kabul 2021, Beijing 1949’, SupChina, 24 August 2021

- Prelude to a Restoration: Xi Jinping, Deng Xiaoping, Chen Yun & the Spectre of Mao Zedong, China Heritage, 20 September 2021

- Jianying Zha 查建英, ‘China’s Heart of Darkness — Prince Han Fei & Chairman Xi Jinping’, China Heritage, 14-22 July 2021

- Isaiah Berlin, et al, ‘Xi Jinping’s China & Stalin’s Artificial Dialectic’, China Heritage, 10 June 2021

- Spectres & Souls, China Heritage, 2021

- Olga Khvostunova, interview with Sergei Guriev: “We may already be seeing Russia’s return to the repressive dictatorship of the 20th century”, The Institute of Modern Russia, 5 August 2021

- Olga Khvostunova, interview with Ivan Kurilla: “Russia and the U.S. have defined themselves through opposing each other for almost a hundred years”, The Institute of Modern Russia, 8 June 2021

- Olga Khvostunova, interview with Lev Gudkov: “The unity of the empire in Russia is maintained by three institutions: the school, the army, and the police”, Institute of Modern Russia, 3 May 2021

- Bálint Magyar and Bálint Madlovics, The Anatomy of Post-Communist Regimes: A Conceptual Framework, Central European University Press, 2020

- Adam Tooze on China, essays and podcasts (2020-)

- Matt Klein and Adam Tooze, ‘On World Order, Then and Now’, ChinaTalk, 25 September 2020

- Jo Inge Bekkevold & Bobo Lo, eds, Sino-Russian Relations in the 21st Century, Palgrave Macmillan, 2019

- Translatio Imperii Sinici, China Heritage, 2019

- China-Russia Report, substack (November 2018-)

- Xu Zhangrun 許章潤 Archive, China Heritage (August 2018-)

- Timothy Snyder, ‘Ivan Ilyin, Putin’s Philosopher of Russian Fascism’, The New York Review of Books, 16 March 2018

- ‘Ruling The Rivers & Mountains’; ‘The Party Empire’; ‘Homo Xinensis‘; ‘Homo Xinensis Ascendant’; and, ‘Homo Xinesis Militant’, China Heritage (8 August-1 October 2018)

- Masha Gessen, The Future Is History: How Totalitarianism Reclaimed Russia, New York: Riverhead Books, 2017

- Aleksandr Dugin, ‘We have our special Russian truth’, BBC interview, on YouTube, 28 October 2016

- Nadya Tolokonnikova and Slavoj Žižek, Comradely Greetings: The Prison Letters of Nadya and Slavoj, London: Verso, 2014

- Tatiana Filimonova, ‘Chinese Russia: Imperial Consciousness in Vladimir Sorokin’s Writing’, Region, vol.3, no.2 (2014): 219-244

- Geremie R. Barmé, ‘1989, 1999, 2009: Totalitarian Nostalgia’, China Heritage Quarterly, no.18, June 2009

- Michael Geyer and Sheila Fitzpatrick, eds, Beyond Totalitarianism: Stalinism and Nazism Compared, Cambridge University Press, 2008

- Peter Shorett, ‘Dogmas of Inevitability: Tracking Symbolic Power in the Global Marketplace’, Kroeber Anthropological Society, vol.92-93 (2005): 335-357

Stalin’s Shade

As an exchange student at late-Maoist universities in the People’s Republic of China, the vestiges of the Soviet Union were in evidence everywhere. Although the Sino-Soviet relationship was tense — a fierce border war had been fought a few years earlier, a major factor in the failed coup against Mao in 1971 that supposedly involved China-Soviet-US tensions, and Soviet Revisionism was denounced with more gusto than American Imperialism — Joseph Stalin’s shadow was never far away.

Portraits of the disgraced Soviet leader featured in Chinese lecture halls and classrooms; the shelves of university libraries and reading rooms in factories and government offices throughout the country groaned under the weight of the multi-volume translation of Comrade Stalin’s complete works; and his name was always defiantly included in the political litany of 馬恩列斯毛 Mǎ-Ēn-Lìe-Sī-Máo, ‘Marx-Engels-Lenin-Stalin-Mao Zedong’. Quotations from Stalin might not have been as ubiquitous as those of Chairman Mao, but they were reverently printed in bold type in newspapers, periodicals and books nonetheless. Furthermore, Uncle Joe’s portrait was on permanent display alongside those of Marx, Engels and Lenin in Tiananmen Square. They all looked north in deference to the huge south-facing picture of Mao Zedong on Tiananmen Gate.

Books and pictures were by no means the only evidence of the abiding influence of the Soviet Union. In our politics class we studied Stalin’s ‘Short Course’, the full title of which was History of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks): Short Course. Chinese Communists had been studying what was known as ‘Stalinist bible’ since it first appeared in the late 1930s and it remained the model for China’s own political narratives, political line struggles as well as history writing. Of course, Lenin’s works were duly studied, and Trotsky repeatedly described, but it was Stalin, the Vožd’ Вождь, who loomed largest. In classes on literature we were taught about Soviet socialist realism and Chinese translations of works by Maxim Gorky and Georgi Plekhanov, among many others, and novels like The Gadfly by the British writer Ethel Voinich — which was wildly popular in the Soviet Union — and How The Steel Was Tempered were pressed on us by our classmates, who were all former Red Guards.

The dormitories we lived in were of Soviet design, as were the serried rows of squat apartment buildings in the cities in which I studied. The remains of unfinished engineering projects — titanic, ghoulish cement structures — littered the landscape and the language we heard, the words we read and many of the ideas to which we were exposed were of Soviet origin. And, everyone knew that unisex Mao suits, or the Zhongshan ensemble, were at one point also called ‘Lenin suits’ 列寧裝.

Some aspects of the Soviet legacy were more appealing, such as the Moscow Restaurant — 北京莫斯科餐廳 / Ресторан Москва. Tucked around the back of the Beijing Exhibition Hall (formerly the Soviet Exhibition Hall), a building designed in the socialist classical style favoured during the Stalin era, Lǎo Mò 老莫 (‘Old Moscow’) opened in 1954. In the 1970s, Moscow Restaurant was the only publicly accessible establishment in the capital that served what passed as Western-style cuisine. Miraculously, it still also had a plentiful supply of Russian vodka. As the city’s most luxurious and expensive restaurant Lao Mo tended to attract diplomats, high-level Party cadres and their children, as well as foreign students. When, from the late 1970s, more enticing venues opened, cashing in on the relaxed economic policies of the time, Lao Mo become something of a dive, a cheap hangout that attracted heavy drinking young gadabouts like the writer Wang Shuo, as well as a clutch of ‘Misty Poets’ and various artistic wannabes.

Even then, for many years physically Beijing was essentially a Soviet city: the mazes of tenement courtyards clustered around the hutong-alleyways of ‘Old Peking’ languished were crisscrossed by boulevards devised by Soviet urban planners in the 1950s and pockmarked by hulking structures, also of Soviet design (with the occasional ‘Chinese cap’, as the chinoiserie roofs of the Academy of Science and the PLA logistic department were called), built to house Party organs, government ministries and the nomenklatura. Stodgy architectural flourishes featured in some of the Ten Grand Edifices, Soviet-designed and built in celebration of the first decade of the People’s Republic, might have reflected banal ‘national forms’, but the only thing that was really Chinese about them was the fact that they were in the country’s capital.

Another unavoidable Soviet legacy was the centrally planned Chinese economy and the material immiseration of the population. Scarcity of food and everyday consumer items, snaking lines of anxious shoppers hoping to secure whatever produce might suddenly become available, the ubiquity of ration coupons and the alternative economy that was geared to those with Party privileges, the dedicated shops for the nomenklatura, the limited-access bookstores, secretive screenings of contraband films and entrenched corruption in its egalitarian camouflage were the telltale evidence of Stalin’s long shadow.

After Mao’s death, and from when I first worked in Hong Kong, I was exposed to the censored Soviet world of dissident writing and thinking. Soviet writers and thinkers as well as many of their fellows from the Eastern Bloc filled out my understanding of Chinese Communism and the Mao era. From the mid 1980s, Russian, Hungarian, Czech and Polish dissidents were crucial to my evolving engagement with post-Maoist Chinese culture, thought and society. My co-edited books like Seeds of Fire: voices of Chinese conscience (2nd ed., 1988), New Ghosts, Old Dreams: Chinese rebel voices (1992), as well as Shades of Mao: the posthumous cult of the great leader (1995) and In the Red: on contemporary Chinese culture (1999) were informed and enriched by the insights of writers from the ‘western pole’ of world socialism (see, for example, ‘Less Velvet, More Prison’, China Heritage, 26 June 2017).

In our 2018 series ‘Drop Your Pants!’ we referred to earlier work on ‘totalitarian nostalgia’ and its abiding effect on Chinese thought, language and politics. There, too, Russian writers were an inspiration, in particular Svetlana Boym and Mikhail Epstein. In the new millennium, I pursued ideas related to residual and revivalist totalitarian thinking in work like ‘Conflicting Caricatures’, (2000) and The Forbidden City (2008), as well as in my advocacy of New Sinology (2005 and thereafter), in studies like ‘Red Allure & The Crimson Blindfold’ (2010) and On New China Newspeak (2012). Following the publication of ‘Drop Your Pants’, I extended that decades-long consideration of the topic of what I now also call ‘recurrent totalitarianism’ (after the Russian sociologist Lev Gudkov) in Translatio Imperii Sinicii (2019) and, in the lead up to the present series, Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium, we released ‘Prelude to a Restoration’ (2021).

***

The Sino-Russian Century —

amitié éternelle

In January 2021, Wang Yi, China’s Foreign Minister, declared:

‘The strategic alliance between China and the Russian Federation admits of no boundaries and recognises no caveats. The sky is the limit.’

中俄戰略合作沒有止境,沒有禁區,沒有上限。

In celebrating the ‘amitié éternelle’ 世代友好 shìdài yǒuhǎo — that is a trans-generational or everlasting friendship — between the two countries, Wang observed that in 2021 Beijing and Moscow would be celebrating the second decade since the signing of the Sino-Russian Treaty of Friendship. What Wang did not say, however, was that 2021 also marked a hundred years since the Soviet Union, a revolutionary nation formed on the basis of the defunct Russian empire, became intimately involved in the founding and political direction of the Chinese Communist Party itself (see Tony Saich, ‘The Chinese Communist Party During the Era of the Comintern (1919-1943)’. Russia — as empire, as the Soviet Union and then as the Russian Federation — has played a predominant role of ‘foreign influence’ in China’s modern history, one that has arguably been more significant than even that of the United States of America.

As we have repeatedly pointed out in China Heritage, both the Communist Party and their rivals the Nationalist Party were deeply influenced by the October Revolution of 1917; both political groups emulated key organisational principles of the Soviet Communist Party. For a time in the 1920s, the Comintern, an organisation directed by the Soviet Union that advocated world revolution, even encouraged political co-operation between the two Chinese parties. And, the Nationalist-Communist split in 1927 was the beginning of a civil war that, in one form or another, has continuesd to the present day (for more on this see, Dai Qing 戴晴 et al, ‘Commemorating a Different Centenary — Dai Qing on the 1911 Revolution’, China Heritage, 12 October 2021).

Over the one hundred years of the CCP, Soviet/ Russia relationship, the Chinese Communists, either influenced by or reacting to the Soviets, have made choices that have shaped Mainland China in a multitude of ways. The Sino-Russian century has, more often than not, led to ill-conceived policies, internecine stife and civic devastation. Communist factional warfare, rife from the 1920s, has also been an abiding feature of Chinese political life, as well as its succession politics. The Yan’an Purge, in part inspired by Stalin’s Moscow Show Trials, outlawed what little remained of loyal dissent within the Party. In the early 1950s, Mao’s policy of ‘leaning to one side’ 一邊倒 in favour of a pact with the Soviet Union against the United States and post-War Europe, along with the Chinese Communists’ home-grown Stalinism, shaped the country’s heavy-industry-based transformation, yet it also led to the subordination of bureaucratic and civil competence, as well as the undermining of scientific, educational and cultural life that cast a pall over the country for three decades.

Deng Xiaoping and the survivors of the Mao era introduced Reform and Open Door policies in late 1978 that initially turned the clock back to the early 1950s, before the chocking ideas of doctrinaire Stalinism took hold. After popular uprisings favouring greater economic and political reforms broke out in dozens of Chinese cities in 1989, the Communists retreated and, for nearly three years allowed a counter-reform to stall the nation.

While, according to Vladimir Putin, the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991-1992 was, ‘the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the century’, in China the unravelling of the Soviet Bloc directly influenced the decision of Deng Xiaoping to bring an end to the Counter-Reform. Availing himself of an informal Inspection Tour of the South he launched a further tranche of liberalising economic policies. Shortly after he assumed power two decades later in late 2012, and during his own first Tour of the South, Xi Jinping was said to have been referring to the collapse of the Soviet Union when he quoted a line of classical poetry to the effect that there was ‘No real man among their number’ 更無一個是男兒 (to champion the Soviet cause and fight for the revolution; see The Real Man of the Year of the Dog). That same year Vladimir Putin had started his second decade in power; it turned out to be one during which he, like Xi Jinping, would seek to restore the flagging fortunes of his country (see Prelude to a Restoration).

During the 101 years of the Sino-Russian century, China’s Communists were:

- directly engaged with the Soviets from 1921 until a few years after Stalin’s death in 1953, and in the process benefitted immensely from Soviet leadership, support (even when it was only grudging) and an unprecedented process of technology transfer in all areas, in particular that of the military;

- inspired in their political hooliganism, which Mao extolled as early as 1927 in his famous ‘Report on the Hunan Peasant Movement’ and the successes of thuggery, something that paralleled Stalin’s (and later Putin’s) brutish psychology;

- obliged to cede large swathes of Chinese territory (latterly called its ‘sacred dominion’) to the Soviets following the devastating occupation of Manchuria during the civil war when the murderous actions of the Red Army went without comment then, or complaint now;

- inspired by the example and policies of the Soviet Union both to expand industry and infrastructure, while improving education and health care during the growth years of ‘New China’. This era also saw a kind of Chinese ‘revolutionary romanticism’ that combined militarism with high-sounding ideals flourish;

- in a state of ideological contestation-cum-warfare with the Soviet Union as they vied to claim the mantle of leadership of the socialist movement and global revolution from 1959 to 1969. During this time national self-belief grew exponentially; even as the dictatorship of the proletariat proved to be a vast system of repression, it also conditioned the population in crucial ways;

- in direct conflict with what they called the Soviet Revisionist Empire from 1969 up to 1978;

- in a complex, multi-faceted and at times rancorous relationship with Moscow from 1978 to 1989, a period during which the failures of the Soviet economy helped inform, inspire through counter example and guide Chinese reformers;

- able to recalibrate an engagement with the Soviets during the years of their final decline as well as through the first decade of the Russian Federation, from 1990 to 2001. Again, the Chinese apparat was constantly debating and learning from the failures of the Soviet Union and its satellites;

- to obsess anew during what we call the ‘Xi Jinping Restoration’ over the reason for the collapse of the Soviet Union;

- to find common cause in social conservatism, the glorification of war and a shared obsession with militarism; and,

- from 2001 to 2021 in a good position to pursue a mutually beneficial comity, one which, in February 2022, moved from being a finely balanced partnership into a complex territory involving vacuous hyperbole, hard-nosed politicking and painstaking strategic maneuvering.

For nearly fifty years of the Sino-Russian century, China and the Soviet Union/ Russia have been bound together by mutual self-interest and strategic need. The other five decades have demonstrated a mixture of contestation, envy, rancour and mistrust.

***

Honeymoon of the Autocrats

The years 2012-2022 have proved to be a something of a Sino-Russian shared moment, a decade during which a narrowing vision in the domestic sphere has been accompanied by increasing hauteur on the international scene, binding Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin in a new kind of overlapping autocratic partnership. Putin is often depicted as a ‘lonely strong man’ and Xi Jinping a 寡人 guǎrén, a traditional term meaning ‘The Lone One’ at the top.

In an evenhanded assessment of the latest Sino-Russian decade, Jo Inge Bekkevold, former diplomat and a specialist in geopolitics, notes that:

‘The personal affinity between Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping has further strengthened the bilateral relationship. When Putin returned as President in 2012, he prioritized close partnership with China, while Xi, like his predecessors, chose Russia as the destination for his very first presidential visit. In March 2018, Putin was re-elected as President for another six years, and the Chinese Communist Party’s removal of the two-term limit on the presidency opens for the possibility of Xi Jinping staying in power beyond 2022/23. The “special relationship” between Putin and Xi will, therefore, remain a critical element in the larger relationship. However, the enhanced political partnership goes well beyond mere personal affinity. It builds on close institutional ties that have grown over the years, characterized by the number of high-level bilateral meetings as well as multilateral cooperation mechanisms. The formal political dialogue has been extended to include regular meetings between Chinese and Russian authorities at nearly all levels of government, from central authorities in the respective capitals down to local officials.

‘In addition, the expansion of cooperation in sectors such as education, culture, sports, tourism, and youth means that a traditionally top-down driven relationship is now being complemented by more bottom-up initiatives. This latter development bodes well for cross-border integration between the Russian Far East and China’s North East. Sinophobia in Russia has given way to a more optimistic outlook and the realization that Chinese investments in this region are positive and even necessary.

‘The growing authoritarianism in Russia and China has reinforced political synergies.’

— from Bekkevold’s conclusion in Sino-Russian Relations in the 21st Century

Jo Inge Bekkevold & Bobo Lo, eds, Palgrave Macmillan, 2019, pp.301-302

***

In July 2021, the Sino-Russian Treaty of Friendship that Wang Yi had praised back in January 2021 was renewed. A little over six months later, on the eve of the Beijing Winter Olympic Games in February 2022, Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin issued a joint statement in which they outlined their shared vision not only of the bilateral relationship but of the world. Despite the updated palaver of IR speak and contemporary diplomacy, the statement, and the renewed treaty, resonated in part with the Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship, Alliance and Mutual Assistance which had been signed by Moscow and Beijing in 1950 (it expired in 1979). As so many historical resonances reverberated through life in the early twenty-first century, it was tempting to speculate as to whether the first decade of the second Sino-Russian century would be as unpredictable, and generally disastrous, as the first.

Among other things the joint statement reiterated the remarks that Foreign Minister Wang Yi had made in February 2021:

‘The sides call for the establishment of a new kind of relationship between world powers on the basis of mutual respect, peaceful coexistence and mutually beneficial cooperation. They reaffirm that the new inter-State relations between Russia and China are superior to political and military alliances of the Cold War era. Friendship between the two States has no limits, there are no ”forbidden“ areas of cooperation, strengthening of bilateral strategic cooperation is neither aimed against third countries nor affected by the changing international environment and circumstantial changes in third countries.’

However, in 2022, China and Russia were still a long way from forming an alliance or promising mutual assistance of the kind underwritten for a short time by Mao and Stalin in the early 1950s. For the moment, even though China seemingly had the upper hand in the relationship, as Bilahari Kausikan, a retired senior Singaporean diplomat, noted: ‘Beijing has no other partner anywhere in the world with Russia’s strategic weight who shares China’s distrust of the current global order.’

Roofless

Vice-Foreign Minister Le Yucheng 樂玉成 went even further than Foreign Minister Wang Yi in January 2021 when, in February 2022, mixing architectural and motoring metaphors, he declared that:

‘There is no limiting roof on the Sino-Russian relationship; there are only pitstops in the relationship and no end point.’

不封頂,中俄關係上不封頂,沒有終點站,只有加油站。

Rock-solid

A few days later, on 7 March 2022, preferring a more geologically-grounded trope, Foreign Minister Wang continued the verbal one-upmanship when he described the Sino-Russian relationship as being ‘rock-solid’ 堅如磐石 jiān rú pānshí. He also gestured towards the long-term historical dialectic that underpins it:

‘The China-Russia relationship is grounded in a clear logic of history and driven by strong internal dynamics, and the friendship between the Chinese and Russian peoples is rock-solid. There is a bright prospect for cooperation between the two sides. No matter how precarious and challenging the international situation may be, China and Russia will maintain strategic focus and steadily advance our comprehensive strategic partnership of coordination for a new era.’

中俄關係發展有著清晰的歷史邏輯,具有強大的內生動力,兩國人民的友誼堅如磐石,雙方的合作前景十分廣闊。不管國際風雲如何險惡,中俄雙方都將保持戰略定力,將新時代全面戰略協作夥伴關係不斷推向前進。

On the Right Side of History

Less than two weeks later, on 20 March 2022, as the Russian invasion of Ukraine intensified, Wang extended the dialectical doublethink. Pointedly upending US Secretary of State Blinken and National Security Adviser’s remarks that China’s positioning on Ukraine placed it on the wrong side of history, Wang averred that:

‘China’s position is objective and fair, and is in line with the wishes of most countries. Time will prove that China’s claims are on the right side of history.’

王毅說,中方的立場客觀公允,同大多數國家的願望相一致,時間將證明,中方的主張是站在歷史正確的一邊。

Yet with a Bottom Line, for foreign consumption

On 25 March 2022, the SupChina newsletter landed on ‘no forbidden areas, but a bottom line’ (没有禁区但有底线 méiyǒu jìnqū dàn yǒu dǐxiàn) as its expression of the day:

‘China’s ambassador to the U.S., Qín Gāng 秦刚, used this phrase yesterday (in Chinese) to clarify the “no limits” interpretation of China-Russia ties stemming from the two countries’ February 4 joint statement.

‘That joint statement was released in full in Chinese by the Chinese foreign ministry, and in English by the Kremlin, but China has never released its own English-language version. The line where the countries state — just 20 days before Russia launched its invasion of Ukraine — that “Friendship between the two States has no limits, there are no ‘forbidden’ areas of cooperation,” has undoubtedly proved a headache for Beijing. Joseph Webster wrote on SupChina that Beijing “engaged in some damage control” throughout February, but Qin seems aware that the damage is sticking, particularly in Washington, where he is based.

‘It’s unclear if the PR effort will be effective, not least because Qin defines the bottom line as “the tenets and principles of the United Nations Charter, the recognized basic norms of international law and international relations” — especially when 141 countries voted at the UN to condemn Russia’s invasion the week after it began.’

—Lucas Niewenhuis, Newsletter Editor, SupChina

***

A Sino-Russian Echo Chamber

The contemporary parallel worldview of China and Russia has unfolded, in the case of China, since the crushing of the Protest Movement of April-June 1989 and, in post-Soviet Russia, since the events of 1991.

From the late 1990s, in Russia a totalist vision of the country’s geopolitical place in the world increasingly solidified in the Putin Kremlin with the help of ‘court fascists’ like Aleksandr Dugin and Vladislav Surkov. Their ideology is an admix of imperial tropes, vestiges of the failed Soviet Union, religiosity and idiosyncratic resentments. It finds ready echoes in China, itself a country with no dearth of aggrieved thinkers who have a penchant for theatricality and bombastic overreach (see, for instance, Mendacious, Hyperbolic & Fatuous — an ill wind from People’s Daily).

Resentment over the end of empire, resistance to perceived Western quasi-imperial hauteur, contempt from the secular West, grievance over material inequality; imagined and real enemies determined to subvert monolithic rule; constant insecurity about the legitimacy of their regimes due to the suppression of meaningful public participation, political openness and democracy; a shared culture of misinformation, fabrication and deception — these are among the factors at work in both China and Russia. Through an increasingly rigid and indoctrination-oriented education system, 24/7 state-sponsored media, the purposeful inculcation of extremist thought and emotions both countries make a great show of presenting their differences with their enemies in terms of a ‘clash of civilisations’, but it is a clash concocted from history, as well as being a cynical ploy by entrenched political interests. Even as the hue and cry about differences increased, the world order that both countries hoped to manipulate to their own needs allowed them to enjoy unprecedented economic benefits.

Thus, after a century, the two reconstituted empires share a bond in the 2020s that was forged in blood and revolution, through ideological contestation and in hegemonic aspiration. It is a bond of military exchange and celebrated martyrdom, of resentment and grievance. It is a bond with a numinous dimension, one that touts the unique values of a Spiritual East that is pitted against a decadent Materialist West that is depicted as being in social, economic and political decline. Today, traditional values and patriotic education are used in both China and Russia to counter corrupting Western ideas. In China’s case the repertoire is summed up in numerous official documents and exhortations; for Russia the latest iteration can be found in a draft document on state ideology released by Moscow for public discussion in January 2022. There Russians are warned to be on guard against the ‘cult of egoism, overindulgence, immorality, rejection of ideals such as patriotism, service to the Fatherland, propagation, contemplative labor, and Russia’s positive input into world history and culture.’

The Sino-Russian bond is one forged on the basis of a mutual admiration for strength and contempt for Euramerican culture, the charisma of which has appealed to and influenced much of the world for over seventy years. It is a bond advanced by individual leaders confident that their time has come and whose self-willed historical mission lies in reviving the fates of their respective nations. These autocrats are backed up by thinkers and ideologues who draw ideas pellmell from eclectic sources as they are egged on by a coterie of courtiers, economic titans and ambitious apparatchiki. Greater Russia, Russian world Русский мир or Holy Rus’ Русь is paired with the revivalist dream of Sacred China 神州大地; both occupy territories expanded by dint of conquest, subversion and subjugation. Both jealously model themselves on, as well as warn against, two centuries of American history. Both believe that they will play an instrumental role in casting American corporate capitalism and empire into the dustbin of history. Both believe that their time in the sun is long overdue, for it is an aspiration that was born in the ruins of the First World War; they are increasingly anxious to lay claim to a future that is fixated on the past. Both regard peripheral democracies — Ukraine and Taiwan — as an existential threat to their vision for a Great Unity. Yet, as a result of their rule, their gargantuan territories have been reduced to the status of socio-political pigmies; at every turn, their pusillanimous view of humanity further reduces the possibilities that should be open to their respective peoples. Their cynical manipulation of their citizens and smug guile in dealing with others reflect nothing so much as their own homuncular intellectual and emotional dimension. Not since the 1950s has there been such a concordance between Chinese and Russian ways of making sense of the world and their leaders are legitimate heirs to that old autocratic will to power.

***

‘The two countries have the tendency to learn the worst from each other,’ Li Yuan 袁莉 observed in The New York Times. In a report on how Russia is adopting Chinese methods of controlling the media and shaping public option, Yuan noted that:

‘Both the Russians and the Chinese were deeply scarred by disastrous eras under Communism, which produced tyrants like Stalin and Mao, gulags and labor camps, and man-made famines that starved millions to death.

‘Now, Russia is learning from China how to exert control over its people in the social media age.’

In the 2020s, the ‘civilisation states’ of China and Russia continue to tussle with the legacies of defunct empire and bankrupt high socialism; they tout the ‘spiritual superiority’ of their values and reject the materialistic West, even as they hunger for the material and cultural achievements of the West, as well as for recognition, respect and its favours. Ironically, both Putin’s Russia and Xi Jinping’s China nurture a media environment that is now eerily familiar elsewhere. Li Yuan again:

“When people ask me how info environment within the Great Firewall is like,” Yaqiu Wang, a researcher at Human Rights Watch in New York, wrote on Twitter about China’s censored internet, “I say, ‘imagine the whole country is one giant QAnon.’”

— Li Yuan, ‘China’s Information Dark Age Could Be Russia’s Future’

The New York Times, 18 March 2022

And, here we would note that ‘Q’ conspiracists support an autocrat of their own, Donald J. Trump, who they believe has a messianic mission to fight the America’s deep state.

- (For more on disinformation and public disinterest, see Geremie R. Barmé, ‘The Fog of Words: Kabul 2021, Beijing 1949’, SupChina, 24 August 2021; also, Anne Applebaum, ‘Why We Should Read Hannah Arendt Now’, The Atlantic, 18 March 2022. And, on the Sino-American ‘danse macabre’, see ‘The State of the Sino-American Pas de Deux in 2021’, China Heritage, 20 February 2021.)

***

What the Thunder Said

DA

Damyata: The boat responded

Gaily, to the hand expert with sail and oar

The sea was calm, your heart would have responded

Gaily, when invited, beating obedient

To controlling hands

— from ‘V. What the Thunder Said’

T.S. Eliot, The Waste Land, 1922

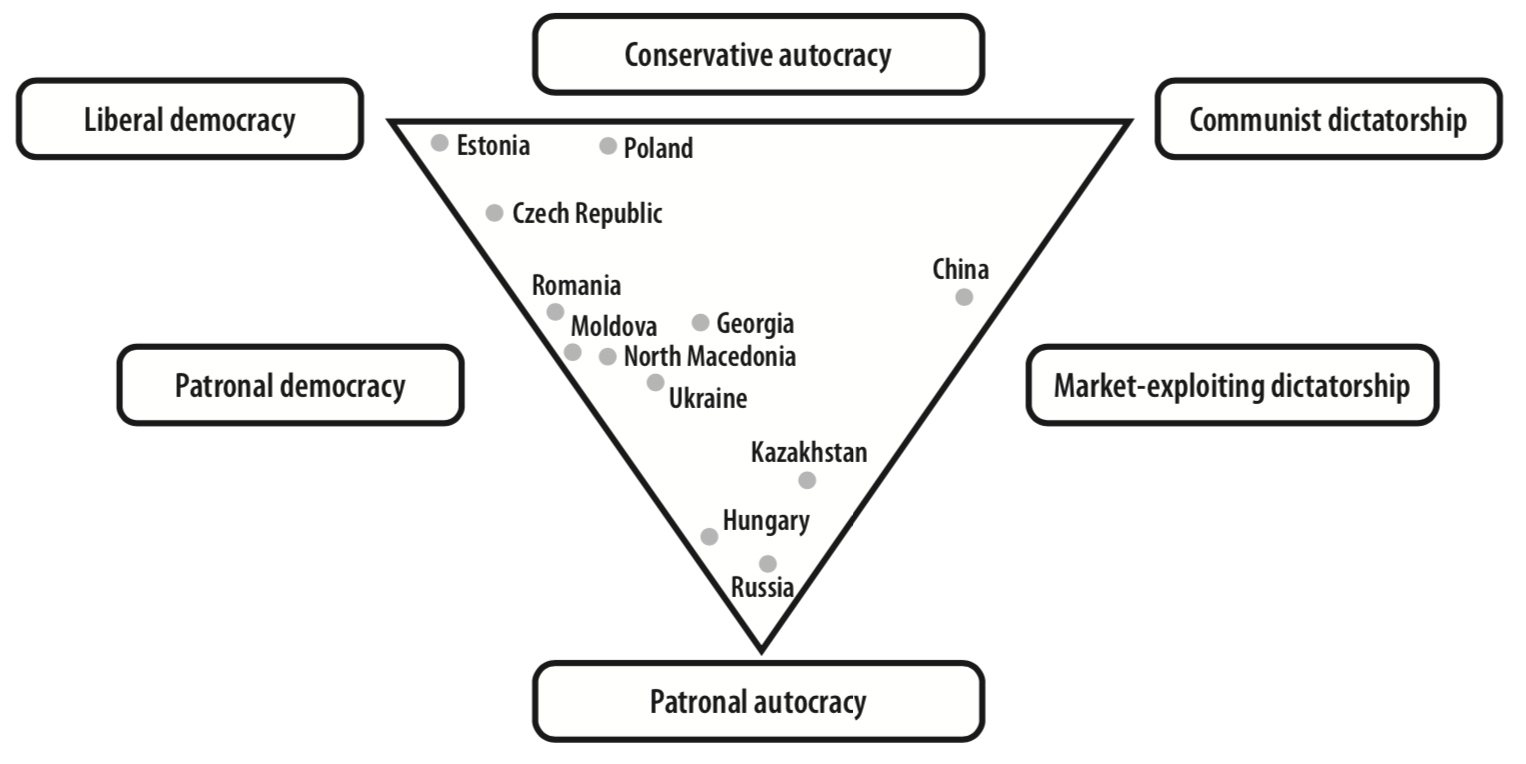

The Conceptual Space of Regimes

— six ideal types and twelve post-communist examples (as of 2019)

***

‘Proles to the East, Fascists to the West’

— Norman Davies on Communism & Fascism

Editor’s Note:

In the 1990s, Norman Davies was a visiting professor in my history department at The Australian National University. He was working on a history of Europe that aimed to give equitable consideration to all parts of the European Peninsula, from the Atlantic to the Urals. In Europe: A History, Davies gave East European affairs a prominence that they were not usually afforded. He proposed this re-orientation at a time when historians of the Middle East and Asia were focussing attention on other long-overlooked geographies and histories.

Upon its publication in 1996, Europe: A History attracted a measure of controversy and I have used and referred to that weighty and often rambling tome with pleasure ever since the revised and corrected edition appeared in 1997. Twenty five years later, and in light of our discussion of the parallel autocracies of China and Russia, it is an opportune time to reprint the author’s discussion of Communism and Fascism, which forms part of his account of the interwar period of 1919-1939.

We offer Davies’s comparison of the two totalitarian ideologies as a preface to the section ‘We Need to Talk About Totalitarianism, Again’, below. The title of this section — ‘Proles to the East, Fascists to the West’ — is taken from Lin Yutang 林語堂.

— Geremie R. Barmé

The concept of totalitarianism was rejected both by communists and by fascists, that is, by the totalitarians themselves. It was destined to become a political football in the era of the Cold War, and it has enjoyed only mixed fortunes among Western academics and political theorists. It has failed to attract those who demand tidy, watertight models, or who identify political phenomena with social forces. It is anathema, and abominable ‘relativism’, to anyone who holds either communism or fascism to be uniquely evil. On the other hand, it is strongly supported by those Europeans who have had practical experience of both communism and fascism at first hand. Communism and fascism were never identical: each of them evolved over time, and each spawned variegated offspring. But they had much more in common than their practitioners were prepared to admit…

Nationalist-Socialist ideology. Both communism and fascism were radical movements which developed ideologies professing a blend of nationalist and socialist elements. During the 1920s the Bolsheviks gradually watered down their internationalist principles, whilst adopting the characteristic postulates of extreme Russian nationalism. Under Stalin, the ideological mix was classified as ‘National Bolshevism’. The German Nazis modified the socialist elements of their ideology over the same period. In both cases the socialist-nationalist or nationalist-socialist blend was stabilized at the same moment, in 1934.

At the conscious level, communists and fascists were schooled to stress their differences. On the other hand, when pressed to summarize their convictions, they often gave strikingly similar answers. One said, ‘For us Soviet patriots, the homeland and communism became fused into one inseparable whole.’ Another put it thus: ‘Our movement took a grip on cowardly Marxism, and extracted the [real] meaning of socialism from it. It also took Nationalism from the cowardly bourgeois parties. Throwing both together into the cauldron of our way of life, the synthesis emerged as clear as crystal—German National Socialism.’ It is not for nothing that people treated to such oratory were apt to think of communists as ‘red fascists’ and of fascists as ‘brown communists’.

Pseudo-science. Both communists and fascists claimed to base their ideologies on fundamental scientific laws which supposedly determined the development of human society. Communists appealed to their version of ‘scientific Marxism’ or historical materialism, the Nazis to eugenics and racial science. In neither case did their scientific methods or findings find widespread independent endorsement.

Utopian goals. All totalitarians cherished the vision of a New Man who was to create a New Order cleansed of all present impurities. The nature of the vision varied. It could be the final, classless stage of pure communism as preached by the Marxist-Leninists: the racist, Jew-free Aryan paradise of the Nazis: or the restoration of a pseudo-historical Roman empire in Italy. The building of the New Order was a task which justified all the sacrifices and brutalities of the present.

The dualist party-state. Once in power, the totalitarian party created organs within its own apparatus to duplicate and to oversee all other existing institutions. State structures were reduced to the status of conveyor belts for executing the Party’s wishes. This dualist dictatorial system was much more pervasivę than that implied by the familiar but misleading term of the ‘one-party state’.

The Führerprinzip or ‘Leader Principle’. Totalitarian parties operated on strict hierarchical lines. They exacted slavish obedience from their minions, through the unquestioning cult of the Party Leader, the fount of all wisdom and beneficence—the Führer, the Vozhd’, the Duce, the Caudillo or the ‘Great Helmsman’. Lenin shunned such a cult: but it was a centrepiece both of Stalinism and of Hitlerism.

Gangsterism. Many observers have noted the strong similarity between the conduct of totalitarian élites and that of professional criminal confraternities. Gangsters gain a parasitical hold over a community by ‘protecting’ it from the violence which they themselves generate. They habitually terrorize both their members and their victims, and eliminate their rivals. They manipulate the law and, whilst maintaining an important façade of respectability, use blackmail and extortion to take control of all organizations in the locality.

Bureaucracy. All totalitarian regimes required a vast army of bureaucrats to staff the bloated and duplicated organs of the party-state. This new bureaucracy offered rapid advancement to droves of opportunist individuals of any social origin. Entirely dependent on the Party, it arguably formed the only social constituency whose interests the regime had to consider. At the same time, it included a number of competing ‘power centres’ whose hidden rivalries gave rise to the only form of genuine political life in existence.

Propaganda. Totalitarian propaganda owed much to the subliminal techniques of modern mass advertising. It employed emotive symbols, son et lumière, political art and impressive architecture, and the principle of the Big Lie. Its shameless demagoguery was directed at the vulnerable and vindictive elements of society uprooted by the tides of war and modernization.

The Aesthetics of Power. Totalitarian regimes enforced a virtual monopoly in the arts, propagating an aesthetic environment which glorified the ruling Party, embellished the bond between Party and people, revelled in heroic images of national myths, and indulged in megalomaniac fantasies. Italian Fascists, German Nazis, and Soviet Communists all shared a taste for portentous portraits of the Leader, for oversized sculptures of musclebound workers, and for ostentatious public buildings of ultra-grandiose proportions.

The dialectical enemy. No totalitarian regime could hope to legitimize its own evil designs without an opposite evil to contend with. The rise of fascism in Europe was a godsend for the communists, who otherwise could only have justified themselves by reference to the more distant evils of liberalism, imperialism, and colonialism. The fascists never ceased to justify themselves in terms of their crusade against Bolshevism, the communists through ‘the struggle against fascism’. The contradictions within totalitarianism provided the motor for the hatreds and conflicts which it promoted.

The psychology of hatred. Totalitarian regimes raised the emotional temperature by beating the drum of hatred against ‘enemies’ within and without. Honest adversaries or honourable opponents did not exist. In the fascist repertoire, Jews and communists headed the bill; in the communist repertoire, fascists, capitalist running dogs, ‘kulaks’, and alleged saboteurs were mercilessly pilloried.

Pre-emptive censorship. Totalitarian ideology could not operate without a watertight censorship controlling all sources of information. It was not sufficient to suppress unwanted opinions or facts; it was necessary to prefabricate all the data that was permitted to circulate.

Genocide and coercion. Totalitarian regimes pushed political violence beyond all previous limits. An elaborate network of political police and security agencies was kept busy first in destroying all opponents and undesirables and later in inventing opponents to keep the machinery in motion. Genocidal campaigns against (innocent) social or racial ‘enemies’ added credence to ideological claims and kept the population in a permanent state of fear. Mass arrests and shootings, concentration camps, and random murders were routine.

Collectivism. Totalitarian regimes laid stress on all the sorts of activity which strengthen collective bonds and weaken family and individual identity. State-run nurseries, ‘social art’, youth movements, party rituals, military parades, and group uniforms all served to cement high levels of social discipline and conformist behaviour. In Fascist Italy, a system of Party-run Corporations was established to replace all former trade union and employers’ organizations and in 1939 to take over the lower house of the national assembly.

Militarism. Totalitarian regimes habitually magnified the ‘external threat’, invented it, to rally citizens to the fatherland’s defence. Rearmament received economic priority. Under party control, the armed forces of the state enjoyed a monopoly of weapons and high social prestige. All offensive military plans were described as defensive.

Universalism. Totalitarian regimes acted on the assumption that their system would somehow spread across the globe. Communist ideologues held that Marxism-Leninism was ‘scientific’ and therefore universally applicable. The Nazis marched to the refrain ‘Denn heute gehört uns Deutschland, / Und morgen die ganze Welt’ (For today it’s Germany that’s ours, and tomorrow the whole wide world).

Contempt for liberal democracy. All totalitarians despised liberal democracy for its humanitarianism, for its belief in compromise and co-existence, for its commercialism, and for its attachment to law and tradition.

Moral nihilism. All totalitarians shared the view that their goals justified their means. ‘Moral Nihilism’, wrote one British observer, ‘is not only the central feature of National Socialism, but also the central feature between it and Bolshevism.’

The concept of totalitarianism stands or falls on the substance of these points of comparison between its principal practitioners. Its validity is not affected by the various intellectual and political games for which it has subsequently been used.

However, communism and fascism obviously differed in the sources of their self-identity. Communists were wedded to the class struggle, the Nazis to their campaign for racial purity. Important differences also lay in the social and economic sphere. The fascists were careful to leave private property intact, and to recruit the big industrialists to their cause. The communists abolished most aspects of private property. They nationalized industry, collectivized agriculture, and instituted central command planning. On these grounds, communism must be judged the more totalitarian branch of totalitarianism.

Of course, one has to insist that the ‘total human control’ sometimes claimed on behalf of totalitarianism is a figment of someone’s imagination. Totalitarian utopias and totalitarian realities were two different things. Grand totalitarian schemes were often grandly inefficient. Totalitarianism refers not to the achievements of regimes but to their ambitions. What is more, the totalitarian disease generated its own antibodies. Gross oppression often inspired heroic resistance. Exposure to bogus philosophy could sometimes breed people of high moral principle. The most determined ‘anti-communists’ were ex-communists. The finest anti-Fascists’ were sincere German, Italian, or Spanish patriots.

From the historical point of view, one of the most interesting questions is how far communism and fascism fed off each other. Before 1914, the main ingredients of the two movements—socialism, Marxism, nationalism, racism, and autocracy—were washing around in various combinations all over Europe. But communism crystallized first. Its emergence in 1917 occurred well in advance of any coherent manifestations of fascism. The communists, therefore, must be rated the leaders, and the fascists the quick learners. The point is: can chronological precedence be equated with cause and effect? Was fascism simply a crusade for saving the world from Bolshevism, as many of its adherents maintained? What exactly did the fascists learn from the communists? It is hard to deny that Béla Kun gave Horthy’s regime its raison d’être. The Italian general strike of October 1922, dominated by communists, gave Mussolini the excuse for his ‘March on Rome’. It was the strength of the communists in the streets and voting booths of Germany which frightened the German conservatives into handing power to Hitler.

But that is hardly the whole story. The fascists, like the communists, were notorious fraudsters: one should not take their pronouncements too seriously. Benito Mussolini (1883-1945), sometime ex-editor of the socialist newspaper Avanti (Forward), author of a pseudo-Marxist work on the class struggle (1912), embezzler and street brawler, had little commitment to political principle. He had no qualms about using his squads of Fascisti first to help the nationalists’ brutal seizure of Fiume in 1920, to support Giolitti’s liberal bloc in the general election of 1921, and later to murder the Socialist leader, Matteotti. He declared himself in favour of constitutional monarchy, for example, shortly before overthrowing it. One need not search for ideological consistency in such tactics: he was simply seeking to exploit the mayhem which he had helped to unleash.

The same must be said of Mussolini’s extraordinary, and extraordinarily successful, behaviour in October 1922. Having first contributed to the chaos which produced the general strike, he then cabled the King with an ultimatum demanding to be made Prime Minister. The King should have ignored the cable; but he didn’t. Mussolini did not seize power; he merely threatened to do so, and under the threat of further chaos Italy’s democrats surrendered. The “March on Rome”, writes the leading historian of Italy, was a comfortable train ride, followed by a petty demonstration, and all in response to an express invitation from the monarch. Years later, when Mussolini’s regime was in dire trouble, Adolf Hitler insisted on saving him. ‘After all,’ the Führer was reported as saying, ‘it was the Duce who showed us that everything was possible.’ What Mussolini showed to be possible was the subversion of liberal democracy, and a second terrible round of Europe’s ‘total war’.

***

Source:

- Norman Davies, Europe: A History, London: Pimlico, 1997, pp.945-949

We Need to Talk About Totalitarianism, Again

In the Tarot, The Hierophant is a sacred intermediary and an agent of history. Here The Hierophant is seated on a throne between two pillars. Traditionally, the pillars symbolise law and liberty or obedience and disobedience. In China, The Hierophant would be framed by the pillars of the State and the Party, while in Russia it would be between the State and the Church. The keys to Heaven lie at The Hierophant’s feet.

***

Classical Totalitarianism

Totalitarianism focuses on the structure and application of power at the centre and stresses the destruction of alternative sources of power and influence (‘islands of separatism’) in society. In a totalitarian society all intermediate institutions between the party and the masses are eliminated. Among other things, law becomes subordinate to the power centre and in practice loses any semblance of independence from the state and party. […] This is usually described by the term atomization, the destruction of all social ties and groups not necessary for the maintenance of the totalitarian system. The regime obliterates the distinction between private and public spheres and individuals are marked by loneliness, anomie and alienation.

— Richard Sakwa, Soviet Politics in Perspective, London, New York: Routledge, 1998, p.17

***

‘There are Proles to the East and Fascists to the West. None of them hold any appeal for me. If you really want me to champion a particular ‘ism’, I can only say that I just want to be myself.’

東家是個普羅,西家是個法西,灑家則看不上這些玩意兒,一定要說什麼主義,咱只會說是想做人罷。

— from Lin Yutang, ‘Preface to “From the Studio of Refusal”, a Book Series’, 1934

林語堂, ‘有不為齋叢書序’

What counts as being totalitarian in contemporary China and Russia? In simple terms, it is the expansion of the political into ever more aspects of life, and its corollary: the determination of the wary to keep as far away from politics as possible. Both countries have been here before and, over the last century, both places have more often experienced such a state of affairs than not. The totalitarian impulse of the Communist Party under Xi Jinping preserves the core of the cloak-and-dagger Leninist state while its leaders tirelessly repeat Maoist dicta; these are amplified by socialist-style neo-liberal policies decked out in cosmetic institutional Confucian conservatism. In an ideal environment, Xi Jinping Thought would expand to fill all available space. In Russia the lust for the totalitarian abjures the Communist past in favour of a fascism in which the military glories of the Great Patriotic War are wedded to a revanchist Moscow Patriarchate.

Over the decades, we have repeatedly pointed out that, despite the economic-reformist turn of the Chinese Communist Party from the late 1970s, in many respects the Mao-Liu cadre-ocracy that held power from the 1950s has proven to be a resilient force. Be it in regards to political and social organisation, real and perceived threats to internal and external security and how they were managed, the ideological underpinnings of the system, the induction and testing of reliable political successors at all levels, the substance of media control and education, as well as the re-deployment of pre-reform personnel, the apparatchiki of the Mao-Liu and High Mao eras (1949-1978) may have tacked their sails to the prevailing winds, but their essential nature, their ‘systemic DNA’ if you will, has been inherited over time.

After Mao, and despite decades of reform, the Chinese Communist Party never really demobbed, or underwent fundamental ideological demilitarisation; apart from punishing select Cultural Revolution upstarts, no thorough-going lustration took place in China. Since the cadres who had enacted the murderous policies of the seventeen years of Mao-Liu (1949-1966) were, by and large, restored to power and their achievements were hailed by their resurgent bureaucratic leader Deng Xiaoping himself, quite the opposite occurred. Deng and the Party affirmed that ‘everything done under Mao Zedong’s leadership from 1949 to 1959 was correct’, and that the Mao-Liu-Deng policies of 1959 were, apart from particular ‘leftist’ aberrations, also beyond reproach. During the 1970s, and in particular around 1978 the Party enacted a policy that saw the wholesale restitution of purged cadres. The approach was known by the short-hand formula that enabled the Party to 撥亂反正 bō luàn fǎn zhèng、正本清源 zhèng běn qīng yuán, ‘restore order in the face of the chaotic political excesses [of the recent past] by returning to the correct path [of an even more distant past] and ‘to set things right again and allow the source to run pure’. The pre-Cultural Revolution ruling cadres were formally ‘placed back in charge’, called 官復原職 guān fù yuán zhí and, in the process, the Party’s underpinning world view, language and practices might have begun to evolve, but they did so substantially on the basis of the psychological loam that was laid down from the 1930s and was in keeping with Stalinist-Maoist traditions. This is not to say, however, that during the reformist heyday (1978 to 2008) there was a dearth of committed bureaucrats, technocrats and people in various spheres of activity who utilised periods of relative Party laxity or innovation to try and transform the party-state in ways that would allow it to become a modern polity. During the Xi Jinping decade, these prodigious, and in many cases heroic, efforts were systematically undermined. China’s ruling class is not lacking in well-trained and well-educated professionals, but the ‘policy settings’ that determine their behaviour bend towards the neo-totalitarian will of their leaders.

Absent a meaningful process of lustration in the early Reformist era of the late-1970s and early 1980s, therefore, the sediment built up over decades of political movements, mobilisations and purges remained relatively undisturbed, even as surface appearances seemed to indicate substantive change. A long-entrenched Party mind-set that was devoted to the control and manipulation of the public, the mechanisms whereby the ‘people’s democratic dictatorship’ exercised everyday power — from the street committees and the local police, through the pervasive network of Party cells, in government and security agencies as well as throughout the legal system — may have undergone reform, but they were not fundamentally refashioned. The more extreme militant aspects of the system may have been stood down, but they remained on stand by. The invasive paternalistic state continued to govern and, whenever favourable conditions allowed it to do so — including during the numerous mini purges and volunteerist movements of the reformist decades — old patterns of behaviour, speech and thought re-asserted themselves. This is why the revanchism of the early years of the Xi Jinping era took root so quickly and unfolded relatively unhindered. Its wellsprings lay deep in the hearts and minds of a society that, even as it donned contemporary fashion and found diversion in the latest electronic gadgets, was that of an earlier, unresolved era. This was how the Xi Jinping Restoration of 2012-2022 became possible; it looks like nothing so much as Norman Davies ‘Eighteen-point Desiderata for Totalitarians’ in action.

The concordance between Xi Jinping’s China and Vladimir Putin’s Russia is not merely a matter of mutual interest and strategic necessity. As we pointed out in the above, it is underwritten by a century of history, as well as shared values and practices that, in the case of China, continue the Mao-Liu tradition while, in the case of the Russian Federation, share a direct lineage with the Soviet era.

It should be remembered, after all, that from the 1990s, the old Soviet nomenklatura continued to man key state institutions; in those positions they continued many ‘legacy practices’. Over the years, in particular from the early 2000s, Russia’s nascent civil society — popular associations, independent media ventures, a more open academic world, education, etc — was gradually contained and undermined. A similar process unfolded in China from the late 1990s and during the early 2000s as grassroots/ minjian social change came under concerted attack from the party-state.

In March 2022, Andrei Kozyrev, Russia’s foreign minister under Boris Yeltsin, observed that for many of the old Soviet power players in the 1990s, and thereafter, ‘the cold war never stopped’. ‘That’s what most people in the US, in the west, don’t understand’, Kozyrev told Courtney Weaver of The Financial Times. ‘That’s why they’re surprised [at recent events] and I am not.’

As we have noted on numerous previous occasions, following the Beijing Massacre of June Fourth 1989, Deng Xiaoping reaffirmed a decades-long opposition to the American-led West which, for its part, continued to believe that ‘peaceful evolution’ would eventually lead to the political transformation of China. It was something that, to quote Kozyrev, ‘most people in the US, in the west, don’t understand.’

***

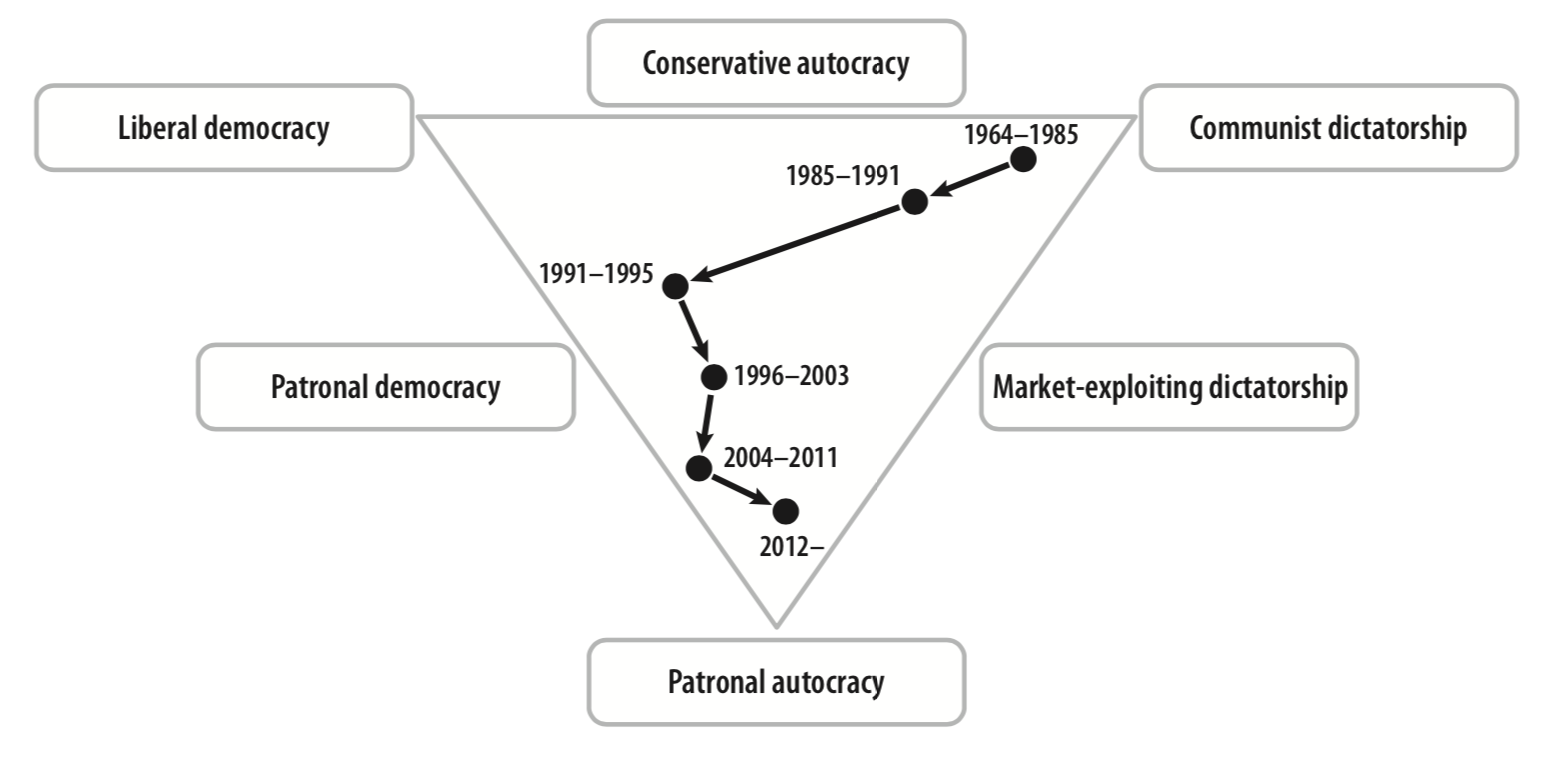

Modelled Trajectory of Russia (1964-2019)

***

The Great Turn: Russia

In the triangle, Yeltsin becoming a chief patron is represented by a clear step toward patronal autocracy and the dominance section of competitive authoritarianism, but not enough to cross the dominance boundaries of semi-formal institutions and relational-market coordination. Yeltsin lacked the monopoly of political power as well as a strong state, which is a prerequisite for a successful mafia state to function. Moreover, he still ruled in the shadow of oligarchs, particularly Vladimir Gusinsky and Boris Berezovsky who owned substantial media empires, and Mikhail Khodorkovsky, who was the country’s richest man and controlled much of Russia’s natural resources as CEO of oil company Yukos. Vladimir Putin, who was named by Yeltsin as his successor in 1999, reformed the state so it regained strength, and also consolidated his power in the sphere of political action with a landslide victory of his United Russia party. This 2003 victory enabled him to perform what Ben Judah describes as “the great turn.” As he writes, it “closed the era where he ruled like Yeltsin’s heir. It was the moment when Russia lurched decisively into an authoritarian regime.” Reportedly, Putin gathered a meeting with 21 oligarchs, informing them that they would be loyal to him and not interfere in politics on their own. He also demonstrated what disobedience would mean: Gusinsky and Berezovksy were forced into exile, giving up their media empires to Putin’s patronal network, whereas Khodorkovsky was jailed and his companies were taken over. From this year on, Russia has been a paradigmatic case of patronal autocracy, with Putin ruling a single-pyramid patronal network with a firm hand. This notably manifested in 2008, when he faced a two-term limit but managed to avoid lame-duck syndrome, making his political front man Dmitriy Medvedev president and returning to power in 2012. After an unsuccessful attempt at a color revolution in 2012, the regime became more oppressive in its state of autocratic consolidation, breaking civil society and neutralizing the autonomy of media, of entrepreneurs, of NGOs, and of the citizens.

— Bálint Magyar and Bálint Madlovics, The Anatomy of Post-Communist Regimes, pp.657-658

***

Over the past decade, a phenomenon that the veteran Russian sociologist Lev Gudkov calls ‘recurrent totalitarianism’ has been on brutal display both in Russia and in China. Above, we touched on some of the political and social factors behind this, that is, factors that facilitated the recurrence of totalitarian behaviour. As Gudkov observed of the situation in post-Soviet Russia:

‘First of all, because the nature of the Soviet system was not properly processed and realized; no basis for its condemnation emerged on the moral, legal, and state level. Russia’s political culture is extremely inertial; it retains elements of the Stalin era and even earlier times—imperialism, serfdom. If we compare Russia with other post-Soviet countries, we will see that democratic transition was successful only where several crucial factors were in place: the memory of national statehood, as in Poland or the Baltic States; surviving remnants of civil society and institutional structures, such as the Church, the Flying University [an educational activist group in Warsaw] or elements of folklore societies; and a long tradition or practice of resistance. Starting in 1956, Poland’s resistance movement grew to realize that coups d’état and ideas of revolution or radical change are illusory in the absence of societal forces interested in new institutions. Institutions need to be created, representation of diverse public interests, movements, and parties needs to be achieved. This means that you have to seek opportunities for a compromise with the authorities, accounting for the views and needs of a people that is alien to democracy and liberalism, with a limited understanding of the ongoing processes. This also means that you need to learn how to conduct a dialogue instead of aiming at destroying the enemy. Culture requires the preservation of pluralism in society and the political system, which is more important than reforms from above and declarations of democracy and law. Russia lacked such traditions, and we quickly became in thrall to illusions—first, offered by the authoritarian democrat Yeltsin and his reformers, who acted with authoritarian methods, and then by Putin with his ideas of “restoration” and “raising Russia from its knees”.’

— Lev Gudkov, ‘The unity of the empire in Russia is maintained by three institutions:

the school, the army, and the police’, Institute of Modern Russia, 3 May 2021

Despite stark differences, over the past decade the leaders of China and Russia have, among other things, launched wholesale attacks on independent legal practitioners, media activists and autonomous social groups. Along with the narrowing of social possibility, academic and cultural institutions have also bowed to the will of the power-holders. In the process, intellectual and cultural mechanisms essential for a society to analyse, dissect and debate its own social realities have been comprehensively sabotaged. The autocrats of Russia and China have radically diminished the ability of their own countries to understand themselves. In turn, such moves hamper the ability of both societies to reflect on and respond to complex new realities in ways that can meaningfully contribute to the long term benefit of their citizens. The refashioned tools of understanding — pro patria media and the academy continue to flourish — primarily serve the needs and ambitions of the ruling class, even at the risk of blinding it to things it would prefer not to know.

Anyone familiar with the benighted state of academia, intellectual life and public policy in Xi Jinping’s China will also be struck by Lev Gudkov’s further observations:

‘The elite—and I mean public intellectuals and the scientific elite, but not business or security officials—turned out to be incompetent, being both externally and internally dependent on the authorities and on the leadership of universities and academies. Even if it is engaged in research and not only in propaganda, this elite is internally subordinated to the needs of superiors who define its line of work. This elite lacks cognitive interests, so it adapts to what it believes is accepted in the world, or in the West, and follows the yesteryear intellectual fashion snooped in Europe or the United States. Our elite is fundamentally imitative. Its claims to intellectual authority are based on flashy knowledge of some Western scholarship, including research in transitology, which it then uses to maintain the illusion of the country’s moving towards a “bright future.” And the current regime is quite happy with this. But the foundation of such an intellectual authority lacks a sober analysis of the country’s state of affairs, of the regime’s nature, and the reasons for public complacency. The elite is eager to demonstrate its readiness to provide the authorities with advice and political prescriptions. Earlier, it would advise how to get from point A (“authoritarianism”) to point D (“democracy”); today, how to optimize the management of the economy, health care, patriotic education, etc. The elite does not study Russian society, nor does it search for group interests to rely on and ensure solidarity. This is a servile readiness to provide advice to the authorities, but, as the past 20 years have shown, the Kremlin did not even need it. Servility has become widespread across all Russian universities. A recent report by DOXA and the investigative media outlet Proekt that 92 percent of the heads of the top 100 universities are associated with the pro-Kremlin United Russia party. Their scientific potential is zero, but they hold means of control over education, socialization, and teaching. These examples capture the logic of restoration of totalitarian institutions perfectly.’

— Lev Gudkov, ‘The unity of the empire in Russia is maintained by three institutions’

- (For examples of the crimped repertoire of the subordinated intellectual elite of China — the so-called ‘establishment intellectuals’, or 御用文人 yùyòng wénrén in traditional parlance — see Reading the China Dream.)

***

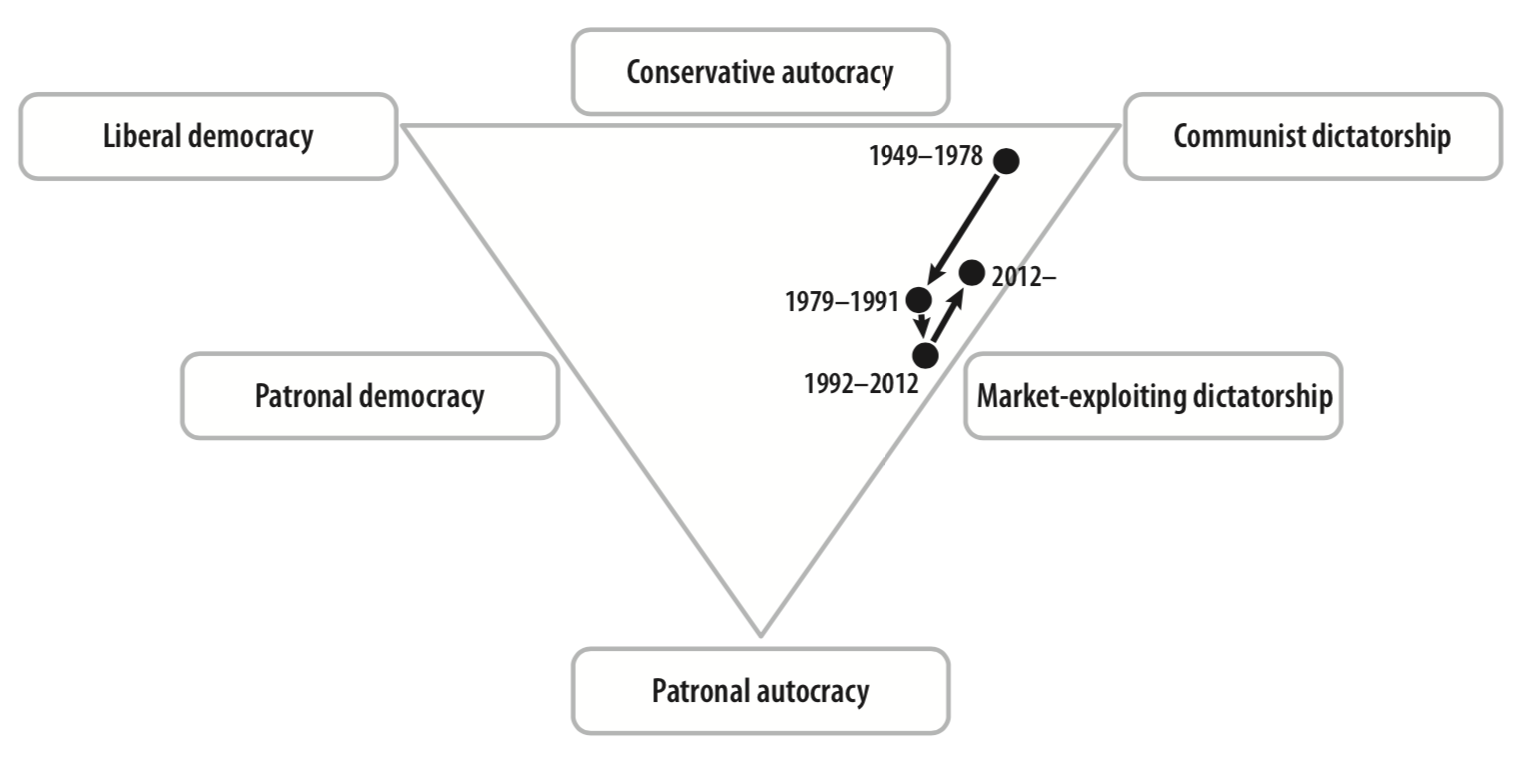

Modelled Trajectory of China (1949-2019)

***

The Great Turn: China

Stronger liberalization and decentralization followed after Deng’s Southern Tour of 1992, consolidating the country at an equilibrium of market-exploiting dictatorship. Yet the last point in the triangle shows backlash toward dictatorship, as it represents the strong centralization under Xi Jinping since 2012. [Sebastian] Heilmann interprets Xi’s reforms as a return to crisis mode, which is a temporary reintroduction of stronger dictatorial functioning to counter an extraordinary situation. As he writes, Xi “obviously sensed that the decision-making and loyalty crises in the Politburo under General Secretary Hu Jintao (2002–12) and the corruption and organization crises in the Communist Party had collectively reached a dangerous level […]. Therefore, the best way to achieve […] organizational stability […] was through a concentration of political power and centralized decision-making, organizational and ideological discipline, extensive anti-corruption measures, and the prevention of any attempts to form factions or cliques within the party, coupled with a campaign against Western values and concepts.” [See Sebastian Heilmann, ‘3.1. The Center of Power’, in China’s Political System, Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2016, p.161.] In the triangle, this means a movement to the dominance section of ideology-drivenness, as well as closer to bureaucratic-resource distribution and totalitarian rule. Yet this is still not a secondary trajectory, that is, not a (emerging) pattern change toward communist dictatorship. Xi’s reforms remain within the logic of market-exploiting dictatorship, and mainly decrease the share of relational market-redistribution, not market coordination, in the country’s markets. China has exploited markets for decades and understood its benefits: the reformed nomenklatura will not break down the reforms and return to a setting that only had a stronger grip but not a stronger economy or legitimation. The essence of Xi’s reforms is strengthening bureaucratic patronalism to avoid informal patronalism, not to return to communist dictatorship. Hence, China remains an example of market-exploiting dictatorship and its modelled trajectory, an example of dictatorship reform.

— Bálint Magyar and Bálint Madlovics, The Anatomy of Post-Communist Regimes, pp.646-647

emphasis in the original

***

In China, Xu Zhangrun 許章潤, a displaced professor of jurisprudence, coined the expression ‘Legalistic-Fascist-Stalinism’ 法日斯 Fǎ-Rì-Sī to describe the reinvigorated totalitarian aspirations of the Xi Jinping decade. In discussing what he called ‘New Era big data totalitarianism’ in February 2020, Xu observed that:

‘Although the Communist Party has formulated its ideology in various guises over the decades, it has not fundamentally changed. That is how the nationalism that underpins their enterprise is presently cast in terms of “the revitalization of the great Chinese nation,” while the broad-based aspiration for national wealth and power was formulated [in the 1970s] under the slogan of “[achieving] the Four Modernizations” [of agriculture, industry, defense, and science and technology]. Twists and turns have followed one upon another, including such ideological formulations as the Three Represents [of the Jiang Zemin era that stated that the Party “represents the means for advancing China’s productive forces; represents China’s culture; and represents the fundamental interests of the majority of the Chinese people”] and the The New Three People’s Principles [reformulated in the early 2000s on the basis of ideas first articulated in the Republican period, 1912-1949] right up to the “New Era” announced under Xi Jinping [and written into the Communist Party Constitution in late 2017].